Abstract

Attachment theory suggests that childhood relational patterns can shape later life dynamics, including occupational choices. This study specifically investigates how these attachment styles influence motivations for entering sex work. Secure, insecure, and disorganised attachments may influence how individuals perceive relationships, cope with adversity, and make career decisions. This paper explores how attachment styles relate to motivations for entering sex work. Previous research has highlighted the role of childhood attachment in adult well-being, decision making, and vulnerability to exploitation. To investigate this further, 10 sex workers based in Mumbai, India, were interviewed. Participants were questioned about their attachment patterns, motivations for entering sex work, and views on their children following in the same path. Thematic analysis revealed that secure and insecure attachment styles were most common, with secure attachment being more prevalent. Whilst disorgranised attachment was rare, it still occurred within the sample group. The most frequent motivation for entering sex work was financial need, often tied to family support. Across secure and insecure groups, mothers expressed a strong protective instinct to prevent their children from entering the industry. Whilst attachment patterns play some role in motivations, broader socioeconomic factors remain central to career pathways. However, as the sample is drawn exclusively from Mumbai, these findings should be considered within the context of the city’s socioeconomic and cultural dynamics, which may not align with those in other regions. Exploring how these dynamics vary across different settings could yield a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between attachment styles and occupational decisions.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of attachment theory in influencing individuals towards a career in sex work. It specifically examines whether patterns of secure, insecure, or disorganised attachments from childhood are reflected in adult relationship dynamics and their occupational decisions. This study hypothesises that participants’ childhood attachment styles will be linked to their motivations for entering sex work, with secure attachments more likely associated with motivations framed as sacrifice or choice, and insecure or disorganised attachments more likely associated with instability, or lack of support that may limit available options or increase vulnerability to exploitation. For this study, “sacrifice or choice” refers to themes in which participants describe entering sex work as a voluntary or family-oriented decision such as; to support children or aid in household financial crisis. Contrarily, “instability or lack of support” refers to disrupted caregiving, coercion, neglect, or economic dependence that limited perceived autonomy in choosing this profession.

The Attachment theory, first developed by John Bowlby1, and later expanded by Mary Ainsworth2, describes how early bonds between a child and their primary caregiver shape patterns of trust, emotional regulation, and relationships throughout life. According to this framework, secure attachments arise when caregivers consistently meet a child’s emotional and physical needs, fostering a healthy and secure relationship. Insecure attachments, on the other hand, whether avoidant, anxious, or disorganised, often emerge when caregivers are inconsistent or harmful, potentially leading to difficulties in emotional regulation and trust. Over time, these attachment patterns may shape significant life decisions, including career choices.

In the context of sex work, examining attachment patterns offers a unique lens for understanding how childhood experiences may shape adult pathways into the profession. However, as this research involves a sensitive topic, participants may experience evaluation apprehension, which can lead to the Hawthorne Effect in responses, introducing a potential bias in the data. This topic is an important one to explore further through research because understanding the psychological and relational factors influencing career choices in sex work can improve support systems, encourage mental health interventions, with the potential to reduce stigma and improve social understanding and hopefully reduce stigma.

Literature Review

Socioeconomic and Psychological Basis of Sex Work

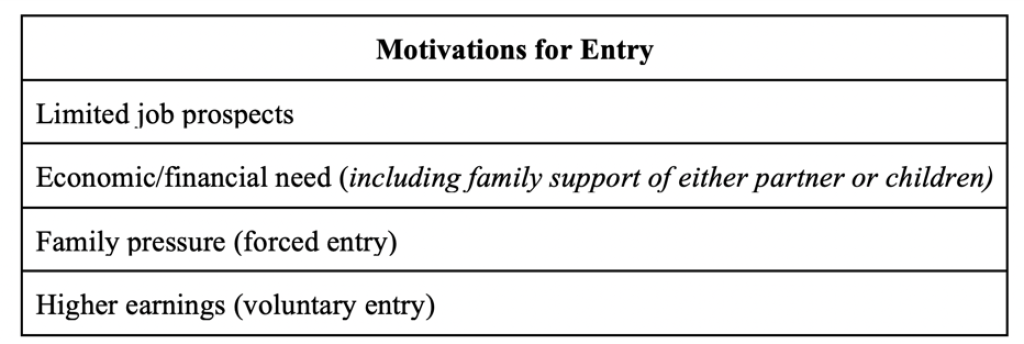

A primary factor identified as the motivation for entering the sex work industry is recognised as limited opportunities available in other industries3. A study further expands on this by discussing the economic hardships these workers endure prior to entering the field, emphasising that the lack of opportunities is a significant driver to pursue sex work4. It is also highlighted that additional factors, such as external pressure from partners and adherence to family traditions, as reasons for entering the industry5.

Further exploration into the psychological toll of working in this environment evidences that it has a significant impact on the individual3. For instance, it has been reported in a study reported that 19% of its interviewees had attempted suicide within the past three months6. Additionally, recurring violence towards workers has been identified as a key predictor of future depression and suicide attempts7. Investigation into the factors contributing to the negative impact on sex workers’ mental health found that rising levels of depression and alcohol abuse are influenced by violence8. Further research also links drug abuse, low education, and social stigma to the causes of suicide attempts8. This finding is corroborated by fellow researchers 9’6.

A decline in mental health among sex workers, with violence as a critical cause, is evident in these working environments and takes shape in multiple forms, such as violence from partners, customers, and entrapment8. However, positive motivations for entering the sex work field do exist, and those who enter due to these factors face fewer mental health challenges5. These positive factors include higher earnings compared to other domestic jobs, greater freedom over their bodies, and workplace flexibility that allows them to manage additional responsibilities. This supports previous research finding that sex workers with children are less likely to attempt suicide6.

Existing literature covers the socio-economic challenges and external pressures that contribute to the decision to enter sex work however, there is a noticeable gap remains in understanding the role of one’s upbringing and family dynamics in this choice. Many studies emphasise economic hardship and lack of opportunities as primary motivators10’4, there is limited exploration into how a person’s early life experiences, particularly their relationship with family caregivers, can impact this decision. This oversight is important, as upbringing could shape both the influences that lead individuals to sex work and their mechanisms in coping with the psychological and social challenges of the industry.

Whilst socioeconomic constraints largely factor into motivations for entering sex work, these explanations alone do not account for the variation of caregiving experiences or emotional regulation observed among individuals in a similar context. The Attachment theory offers a complementary psychological lens, suggesting that early relational experiences shape not only emotional stability but also patterns of coping and dependence, which can potentially affect life decisions, such as career choices, under stress.

Attachment Theory and its Application to Adult Life Implications

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory puts forward that children’s attachment behaviours are crucial for their survival, as these behaviours develop a closeness between them and their mothers in response to real or perceived threats11.

Several key concepts are identified that are incorporated into Attachment Theory, including developmental psychology, cybernetics, information processing, ethology, and psychoanalysis12. Additionally, evolutionary theory also serves as a foundation for Bowlby’s work11. The development of Attachment Theory has led to a deeper understanding of how a child’s bond with their mother can be disrupted by deprivation, separation, and grief12.

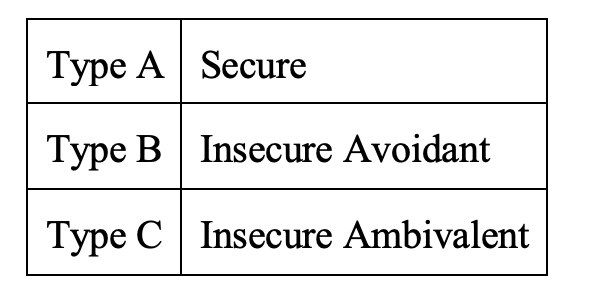

Mary Ainsworth significantly advanced this field in 199113, by developing attachment classifications11, which include:

Ainsworth’s contributions to Attachment Theory encompass the concept of a protective figure who provides a safe haven from which a child can explore the world12. Additionally, the theory highlights the significance of a mother’s sensitivity to her child’s signals in shaping the attachment patterns between them.

Building on these foundations, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), developed by George, Kaplan, and Main14, provided a structured method for assessing how early attachment experiences are represented in adulthood. This study does not employ the AAI; in-depth interviews and thematic coding analysis are utilised instead to allow participants to share personal narratives of childhood and career experiences in their own words. Casual, open-ended questions were used to promote comfort and give participants control over what to disclose, which is particularly important when exploring sensitive topics15.

Bowlby and Ainsworth’s Attachment Theory is essential for research into an individual’s early years surroundings and for understanding the impact of meaningful connections in modern professional practice16.

Methodology

Research design

A qualitative design using in-depth interviews was used to explore the relationship between childhood experiences and later career decisions. In-depth interviews are defined as a qualitative research method used to gain a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of participants’ personal experiences and the meaning the attribute to specific situations17. This approach was selected because it allows participants to reflect on childhood experiences and relate them to attachment theory, aligning closely with the study’s research question. The method was appropriate for addressing a sensitive topic such as the childhood experiences of sex workers, enabling participants’ voice to be heard through open-ended questions.

Participants and Ethical Considerations

Ten female sex workers based in Mumbai participated in this study. This population was selected as it represents a maginalised group often overlooked in academic research. Their experiences provide insight into how family dynamics and socioeconomic backgrounds potentially correspond with career decisions in stigmatised professions.

Participants were recruited through outreach organisations and informal networks in Mumbai’s Sex Work districts. Snowball sampling was employed, where participants referred others within their community. Due to ethical sensitivities and participant comfort, detailed demographic data (such as age or education) were not systematically collected.

Working with smaller groups allowed for more detailed accounts and supported ethical considerations related to confidentiality and participant safety. Each participant provided informed consent, reinforcing anonymity and voluntary participation. Interview recordings were stored in password-protected files. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, participants were reminded that they could withdraw at any time without penalty.

Data Collection (Interviews)

This study did not employ the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI)14. Instead, A semi structured interview schedule was designed, comprising 12 open-ended questions addressing participants’ family backgrounds, caregiving relationships, and motivations for entering sex work (see Appendix A). These questions allowed participants to reflect on both nurturing and adverse childhood experiences.

Data Analysis (Thematic Coding)

The data was analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six step framework for thematic analysis18. The process involved:

- Familirisation with transcripts through repeated reading

- Generating initial codes manually to capture recurring themes

- Reviewing and refining themes

- Defining and naming themes

- Defining and naming themes

All coding and theme development were carried out manually without the use of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software.

Attachment theory guided the thematic analysis by framing how early caregiving experiences might influence adult coping mechanisms and life choices in adulthood. Intial codes were assigned to each interview transcript to identify recurring patterns, which were then grouped into attachment categories (secure, insecure, disorganised). For example, nurturing and supportive caregiving was coded as “positive upbringing”, while neglect or abuse was coded as “abusive childhood environment”.

To further analyse each interviewee’s attachment type, those with children were asked an additional question about their feelings toward their child’s entry into sex work. These responses provided greater insight into the interviewees’ attachment style and parental relationship dynamics. Participants who opposed the idea, often mentioning emotional and social hardships of the job, were coded as demonstrating protective behaviour (secure attachment). Those who were open to the concept were categorised as exhibiting unprotective behaviour themes (insecure attachment).

Motivations for entry were then analysed using the same coding framework. Themes included financial/economic needs, family pressure, or voluntary entry for higher earnings.

Findings

Attachment codes were assigned based on recurring emotional and relation patterns identified in participants’ response and interpreted through the theoretical framework discussed. These categories were understood using attachment principles. For example, “protective behaviour toward a child” portrays characteristics of secure attachment, reflecting emotional availability and care. In contrast, “hidden profession” links to insecure attachment, suggesting anxiety about openness of fear of judgment. Disorganised indicators, such as “loss of parents” or “abusive environment”, aligning with disorganised attachment patterns, showing emotional disruption an instability in early caregiver relationships.

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment refers to a healthy emotional bond formed in relationships, typically between a child and their primary caregiver(s), that leads to individuals feeling safe and supported in their environment. In these interviews, a number of the participants demonstrated signs of secure attachment. These are: Interviewees 1, 4, 7 and 8. Each of these individuals described a positive, supportive relationship with a primary caregiver, most often a mother or father, during their childhood.

For example, interviewee 1 described a secure attachment to her father. She spoke about his role in comforting and looking after her, and highlighted their secure relationship by stating that even given her current job, “{the father} will still love me as before.”

Similarly, interviewee 4 described a close and supportive relationship with her family, in particular her mother, during her upbringing. She reflected positively on her childhood, mentioning that most family members lived together and emphasising the constant support and presence of her mother in her life.

Furthermore, interviewee 7 described a loving and nurturing upbringing with her mother as the primary caregiver for her and her siblings. She recalled that “{they}were so nice to each other and loved each other. {They} had a good family,” and described all her moments with her mother as “good.”

Lastly, interviewee 8 also described a secure attachment to her family. She recalled a nurturing childhood in which her parents consistently cared for her, working in the fields to provide for the family, and she described a close bond with her family, stating that “we all stay together in good and bad times.”

The motivation for entry for each interview that was categorised as a secure attachment with their caregivers was primarily related to providing for their family. Interviewee 1 described it as a way of survival for necessities, explaining that without earning money, “no one cares in this Mumbai city… even if you’re sick, hungry, alone and need some help.” She stressed that a daily income was essential just to afford meals and basic needs. Similarly, interviewee 4 emphasised that her decision to work was driven by the need to support her household after family difficulties, explaining that her father was absent/not involved, and this absence placed additional responsibility on her to contribute financially.

Meanwhile, interviewee 7 explained that her reasoning for entering this field of work was linked to providing for her children. She stated that she would “do this work until my kids get married,” adding that she was “okay with how [her] life is right now” if it meant she could support her kids through her earnings. Correspondingly, interviewee 8 explained that she chose to enter this work as a deliberate decision to support her family during a crucial stage in her children’s lives. She stated, “my children were growing up, so I came here on my own, got my two daughters married and came here to work.” Her reasoning was always tied to family responsibilities rather than personal preference, and with those now fulfilled, she expressed plans to leave the work and move on to other forms of employment, such as sewing.

Insecure Attachment

Insecure attachment refers to an unstable emotional bond formed in relationships, typically between a child and their primary caregiver(s), that results in individuals feeling unsafe, unsupported, or uncertain in their environment. In these interviews, the participants who demonstrated signs of insecure attachment were interviewees 5, 6 and 10.

Interviewee 5 described a limited emotional connection with her mother and family during her upbringing. She expressed little knowledge or memory of her mother and reflected on a childhood marked by poverty and separation, suggesting a lack of consistent support, a theme of insecure attachment.

Interviewee 6 reflected on an upbringing marked by an early separation from her parents, stating that her primary caregivers were her grandparents and that she got married at a young age. She shared little about an emotional connection with her caregivers, suggesting a lack of consistent support and closeness while growing up.

Interviewee 10 expressed that she was separated from her parents at a young age, spending her childhood in another village and working in other people’s houses. She recalled no positive memories of her parents, implying a lack of emotional connection and consistent caregiving.

Similar to the interviewees who demonstrates a secure attachment with their primary caregivers, the participants’ reason for entering this specific field of work was marked by financial issues/supporting their family. Interviewee 5 entered this work due to severe poverty and the need to support her children after separating from her husband. She sought work in the city to earn money for their upbringing and to secure land for the family’s future. Similarly, Interviewee 6 also declared that she entered this line of work of her own will, as a way to provide for five children. Interviewee 10 migrated from Nepal also due to poverty issues. She came independently in search of work opportunities to support herself.

Disorganised Attachment

Disorganised attachment refers to the lasting impact of early experiences of trauma, such as abuse and neglect, on an individual’s ability to form secure and healthy attachments. Such experiences can disrupt trust, emotional regulation, and relationships throughout life. A few participants expressed signs of a disorganised attachment; these are: interviewees 3, 9 and 10.

Interviewee 3 mentioned experiencing the early loss of both her parents and living without close family support, noting that her siblings remain distant unless financial support is provided. Interviewee 9 also mentioned the loss of both parents, stating that she grew up in extreme poverty, lacking adequate food and clothing. She further described that her childhood was marked by deprivation and limited stable caregiving. Furthermore, Interviewee 10 lost both parents in an earthquake and was later rejected by her stepbrother due to poverty. Raised by non-family members who have since passed away, she stated that she now lives without close emotional or familial support.

Interviewees 3 and 9 had similar motivations for entering the industry. Interviewee 3 reported being deceived into entering this job, brought by someone from her village who told her she would be doing housework. Likewise, interviewee 9 was brought by villagers who told her she would be cleaning utensils, suggesting a forced entry or being deceived.

In contrast, Interviewee 10 entered the job on her own after losing both parents and facing rejection from the remaining family, with no other viable work options due to a lack of education. She stated: “I had no other option to survive, so in the end I had to choose this work… I’m not educated, I cannot write or read, so no one gives me work.”

In summary, participants with secure attachments describe their experiences with a stronger sense of stability and control, often linking their work decisions to family responsibilities or financial pressure rather than coercion. Those with insecure attachments share similar motivations but express more uncertainty or emotional strain when discussing their backgrounds. In contrast, participants with disorganised attachment patterns spoke in ways that suggested greater emotional distance, loss, and limited control over their circumstances.

Motivations and Maternal Attachment

Approximately two-thirds of the interviewees report that their motivation to join this line of work stems from economic hardship, often driven by the need to support their family or children. These participants primarily demonstrated either secure or insecure attachment patterns, rather than disorganised attachment. In contrast, a smaller group of exactly two participants, who demonstrate a disorganised attachment, entered sex work due to coercion and deception.

The majority of the interviewees were mothers who express strong views against their children entering the same line of work. Regardless of their own entry into the profession, whether through financial need, insecurity, or coercion, most mothers are determined to shield their children from similar circumstances, often emphasising the importance of education or alternative livelihoods.

The mothers who described having a secure attachment with their own primary caregivers also demonstrated secure attachments with their children (interviewees 1, 4 and 7). This continuity suggests that early emotional security created a strong protective instinct, which was evident when they spoke about their children potentially joining the same field. Each of them firmly opposed the idea, emphasising their desire to safeguard their children from similar challenges.

Likewise, the mothers who described having an insecure attachment with their own primary caregivers reported forming secure attachments with their children. For example, interviewee 5 recalled limited connection and memories with her mother, yet she expressed deep care and a protective instinct toward her own children. She explained that she entered this line of work to support them, reflecting, “Yes, I did for kids… Now what, my life will end soon.” Her efforts helped her children marry and build stable lives, showcasing her long‑term commitment to providing the stability and opportunities she lacked growing up.

Among the three participants who demonstrated a disorganised attachment style, two were mothers. One reported having developed a secure and nurturing relationship with her children, while the other had stepchildren with whom she was no longer in contact.

These findings suggest that attachment experiences continue to shape how participants interpret their circumstances and relationships. Those displaying secure attachment patterns show greater emotional regulation and agency, often framing their work as a deliberate choice linked to caregiving responsibilities. Participants with insecure attachment patterns reveal more uncertainty, expressing instability in close relationships. In contrast, disorganised attachment patterns are characterised by emotional distance and unresolved loss. These patterns illustrate how early attachment experiences continue to shape participants’ coping strategies and sense of control within challenging social and economic contexts.

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that the most common attachment patterns among the participants were either secure or insecure attachment, with secure attachment being more prevalent. Disorganised attachment, while still present, was comparatively rare. The most common motivation for entering the sex work industry was related to financial/economic need, often linked to the need to support and sacrifice for their children or other family members. Across both secure and insecure attachment groups, mothers consistently expressed a strong protective instinct toward their children when asked about them entering the same work, emphasising a need to prevent them from following the same path.

These results suggest that family and upbringing play a role in shaping both motivations for entering sex work and the attachment patterns these women carry into adulthood, with their family members or children. Those with secure childhood attachments tended to replicate these patterns with their own children, mostly entering the profession as a sacrifice rather than deception/coercion. On the other hand, those with insecure or disorganised attachments frequently reported life instability, loss of caregivers, or lack of support, which likely shaped their vulnerability to exploitation or constrained their work options.

The findings from this analysis align closely with existing literature. Specifically, those who identify economic hardship and limited employment opportunities as primary motivators for entering this industry19. In both this study and additional literature, financial pressures, often tied to supporting children or other dependents, emerged as a central theme. Likewise, the role of external pressures and coercion resonates with the experiences of participants such as interviewees 3 and 9, who reported being deceived into the profession by a village/family member5.

While the literature frequently highlights severe psychological impacts, including depression, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse10’6 these specific outcomes were not directly reported by participants in this study. Instead, these signs of emotional distress and instability were observed particularly among those with disorganised attachment upbringings, as reflected in their accounts of early deprivation, loss, and lack of a support system. This does indicate that attachment styles in early childhood may be associated with an individual’s later life and career choices. It is worth noting that while insecure attachment was less common among participants in this study, previous research has linked behaviours associated with insecure attachment to increased emotional vulnerability among female sex workers20. This complements the current findings, which show that participants exhibiting insecure attachment patterns often experience life instability and lack of support, suggesting that both their motivations and experiences in sex work may be influenced by emotional relational challenges, which implies greater risk of exploitation.

From an attachment theory perspective, the prevalence of secure attachment amongst participants may reflect resilience and adaptive caregiving strategies. It is suggested that early stable relationships could have fostered emotional regulation, allowing them to frame sex work as a rational career option. This challenges studies that equate sex work predominantly with trauma or insecure attachments21. Recent research highlights that resilience in sex work is not simply about surviving adverse experiences, but also about recovery and coping in the face of social, legal, and structural barriers22. Secure attachment appears to play a key role in this process, as it can buffer the psychological effects of earlier trauma, reducing emotional and coping issues, even among those with histories of childhood abuse22. Moreover, some sex workers are shown to actively resist stigma and construct strategies that support their mental and social wellbeing, suggesting that resilience may be an ongoing process, rather than a fixed trait23. The latter supports the idea that secure attachment can contribute significantly to resilience among sex workers, even in the context of adversity.

There are previous studies that have extended the attachment theory’s application to adult functioning, including risk-taking behaviour, and coping strategies under socioeconomic stress. Studies provide evidence that early attachment experiences influence stress regulation and that attachment is associated with coping and emotional regulation in emerging adults24’25. These psychological processes may indirectly influence occupational pathways, particularly in contexts where emotional regulation or avoidance patterns affect decision-making under constrained options. Therefore, examining attachment in relation to sex work motivations provides a theoretical framework that potentially links early relational experiences with later life coping and survival strategies.

Limitations

A thematic analysis was used for this research because it allowed for an in-depth exploration of the participants’ experiences, while still highlighting the nuance and complexity of their narratives. Identifying codes and themes made it possible to capture recurring patterns (such as economic hardship, protective attitudes toward children, and the influence of early attachment experiences) that might otherwise have been overlooked in a more structured or quantitative approach. It is significant to identify the thematic analysis relies on the researcher’s judgement to group codes and derive themes, meaning that alternative interpretations of the same data are possible. Considering the latter, findings should be viewed as one possible understanding of participants’ experiences, rather than definitive conclusions.

However, as this research does not utilise methods such as an Adult Attachment Interview (AAI)14, the results of this research are not as exact as those that did use this method. Additional limitations of this research include the generalisability of this study. As it is focused on sex workers based in Mumbai, the findings may not be fully applicable to individuals in other regions or countries where socioeconomic and/or sociocultural factors differ significantly. This geographical focus inherently limits the generalisability of the research.

Although the number of interviews conducted is suitable for this qualitative study, a larger sample size would have allowed for a greater understanding of the different dynamics involved and would have provided a more diverse range of data. The study’s limited population inherently restricts the breadth of perspectives that could be analysed. Due to the environment in which these interviewees live and work, there is also potential that interview responses were falsified during the interview due to the Hawthorne Effect, where individuals modify their behaviour because they are aware of being observed.

In addition to the methodological considerations above, it is important to acknowledge the potential influence of researcher bias on data interpretation. As the interviews were conducted and analysed by the researcher, assumptions or expectations about attachment and motivations may have shaped the identification of themes and their interpretations. While efforts such as reflective journaling were employed to mitigate bias, these strategies cannot fully eliminate subjectivity.

Implications & Future Research

Future research could address these limitations by having a broader participant pool across different regions to capture more varied experiences, as well as combining narrative interviews with more standardised tools such as the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI)14, a structured clinical interview used to assess an individual’s state of mind regarding attachment, particularly their childhood relationships with caregivers, to produce more valid and detailed findings.

By applying attachment theory, this research offers a lens to better understand the influence of familial relationships, not only on emotional patterns (with children/family) in adulthood but also major life trajectories, including entry into stigmatised or high-risk professions. Future research could explore these patterns with larger and more varied groups and look at how early-life support, such as community resources, might widen the range of job or survival choices while fostering a more stable environment for these communities. Understanding how attachment experiences and economic pressures interact can help shape more compassionate and practical ways to support people facing limited options.

While attachment patterns offer insight into the emotional and relational dynamics that may impact involvement in sex work, these psychological frameworks should not be examined in isolation. Broader social and economic constraints, such as poverty, gender-based inequality, educational opportunities, and migration-related challenges, play pivotal roles in the choices available to women26. These conditions create a context of constrained agency, where personal decisions are frequently made under the pressures of marginalisation. Further research shows how women’s agency is shaped and often limited by structural factors. Many are forced into sex work through exploitation, under conditions of poverty, limited job opportunities, and a lack of family support. Even when entry is voluntary, it is often under coercive circumstances or as a means of survival, making what appears as individual choice deeply intertwined with structural pressures27.

Therefore, psychological patterns cannot fully explain engagement in sex work without acknowledging the structural constraints that frame these decisions. Social stigma and limited access to resources frequently leave women with few viable alternatives, shaping both their involvement in sex work and their ability to exercise agency within it. Integrating attachment theory with an understanding of these broader determinants allows for a more comprehensive perspective that recognises both individual emotional dynamics and the potential influence of sociocultural and economic forces on women’s lives. These findings may inform community-based interventions aimed at supporting sex workers in Mumbai through accessible counseling, parent education, and safe childcare programs. Policies enhancing education access for sex workers’ children and mental health outreach could reduce intergenerational vulnerability. Future research could examine how attachment-based counseling might strengthen resilience in similar contexts.

Conclusion

This study found that while financial need was a common thread in participants’ entry into sex work, the pathways leading to it varied significantly depending on early attachment experiences. These results broadly align with the hypothesis, showing a relationship between childhood attachment styles and motivations for entering sex work. Securely attached participants often described their entry as a deliberate or sacrificial choice to support family members. Those with insecure or disorganised attachments also frequently supported their families, but their more nuanced reasons often included caregiver loss, instability, or lack of support, which may have shaped their vulnerability to coercion or narrowed their work options. In both groups, financial need was a common factor, yet the pathways leading to it differed. By applying attachment theory to sex work, it highlights the complexity of agency and care under adversity. These insights underscore the importance of holistic approaches that combine psychological support with social reform to improve the outcomes for vulnerable women and their families.

Appendix

Appendix A

- What is your name?

- How long have you been in this field of work?

- Could you tell me about who is in your family?

- What did/does your mother do?

- What did/does your father do?

- What was your upbringing like?

- What is your favourite memory of your primary caregiver?

- What is your favourite memory of your secondary caregiver?

- What is your most painful memory of your primary caregiver?

- What is your most painful memory of your secondary caregiver?

- What is the motivation for choosing this profession?

- How would you feel about your children/family going into the same profession?

References

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books; 1969. [↩]

- Ainsworth MD, Bell SM. Attachment, exploration, and separation: illustrated by the behavior of one year olds in a strange situation. Child Dev. 41, 49 (1970). https://doi.org/10.2307/1127388 [↩]

- Suresh G, Furr LA, Srikrishnan AK. An assessment of the mental health of street based sex workers in Chennai, India. J Contemp Crim Justice. 25, 186–201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209333590. [↩] [↩]

- Sinha S. Reasons for women’s entry into sex work: a case study of Kolkata, India. Sexuality & Culture. 19, 216–235 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119 014 9256 z. [↩] [↩]

- Saggurti N, Jain AK, Sebastian MP, Singh R, Modugu HR, Halli SS, Verma RK. Motivations for entry into sex work and HIV risk among mobile female sex workers in India. J Biosoc Sci. 43, 535–554 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932011000277. [↩] [↩]

- Shahmanesh M, Wayal S, Cowan F, Mabey D, Copas A, Patel V, Andrew G. Suicidal behavior among female sex workers in Goa, India: the silent epidemic. Am J Public Health. 99, 1239–1246 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149930. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Suresh G, Furr LA, Srikrishnan AK. An assessment of the mental health of street‑based sex workers in Chennai, India. J Contemp Crim Justice. 25, 186–201 (2009).https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209333590 [↩]

- Patel SK, Saggurti N, Pachauri S, Prabhakar P. Correlates of mental depression among female sex workers in Southern India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 27, 809–819 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515601480. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Suresh G, Furr LA, Srikrishnan AK. An assessment of the mental health of street based sex workers in Chennai, India. J Contemp Crim Justice. 25, 186–201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209333590 [↩]

- Suresh G, Furr LA, Srikrishnan AK. An assessment of the mental health of street based sex workers in Chennai, India. J Contemp Crim Justice. 25, 186–201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209333590 [↩] [↩]

- Fletcher HK, Gallichan DJ. An overview of attachment theory. In: Fletcher HK, Gallichan DJ, eds. Attachment in Intellectual and Developmental Disability. Wiley Blackwell; 2016. pp. 8–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118938119.ch2. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Bretherton I. Emotional availability: an attachment perspective. Attach Hum Dev. 2, 233–241 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730050085581. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ainsworth MS, Bowlby J. An ethological approach to personality development. Am Psychol. 46, 333–341 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003 066X.46.4.333. [↩]

- George C, Main M, Kaplan N. Adult attachment interview [Data set]. PsycTESTS (1985). https://doi.org/10.1037/t02879 000. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Westland H, Vervoort S, Kars M, Jaarsma T. Interviewing people on sensitive topics: challenges and strategies. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 24, 488–493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae128. [↩]

- Page J. The legacy of John Bowlby’s attachment theory. In: David T, Goouch K, Powell S, eds. The Routledge International Handbook of Philosophies and Theories of Early Childhood Education and Care. Routledge; 2016. pp. 80–90. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315678979.ch9. [↩]

- Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, de Lacey S. Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them. Hum Reprod. 31, 498–501 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334. [↩]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [↩]

- Huda MN, Hossain S, Dune T, Amanullah A, Renzaho A. The involvement of Bangladeshi girls and women in sex work: sex trafficking, victimhood, and agency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19, 7458 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127458. [↩]

- Potter K, Martin J, Romans S. Early developmental experiences of female sex workers: a comparative study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 33, 935–940 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440 1614.1999.00655.x. [↩]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 86, 1607–1612 (1996). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [↩]

- Worth H, McMillan K, Gorman H, Tuari’i M, Turner L. Sex work and the problem of resilience. Sexes. 6, 7 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010007. [↩] [↩]

- Treloar C, Stardust Z, Cama E, Kim J. Rethinking the relationship between sex work, mental health and stigma: a qualitative study of sex workers in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 268, 113468 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113468. [↩]

- Gause NK, Sales JM, Brown JL, Pelham WE, Liu Y, West SG. The protective role of secure attachment in the relationship between experiences of childhood abuse, emotion dysregulation and coping, and behavioral and mental health problems among emerging adult Black women: a moderated mediation analysis. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 131, 716–726 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000772 [↩]

- Eckstein Madry T, Piskernik B, Ahnert L. Attachment and stress regulation in socioeconomically disadvantaged children: can public childcare compensate? Infant Ment Health J. 42, 839–850 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21878. [↩]

- Vanwesenbeeck I. Another decade of social scientific work on sex work: a review of research 1990–2000. J Psychol Human Sex. 13, 1–30 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2001.10559799. [↩]

- Di Ciaccio M, Adami E, Boulahdour N, Bourhaba O, Castro Avila J, Lorente N, Beldi Chouikha K, Nabli M, Torkhani S, Karkouri M, Rojas Castro D. An intersectional analysis of social constraints and agency among sex workers in Tunisia during the COVID 19 pandemic; the community based qualitative study EPIC MENA. Glob Public Health. 20, 2486436 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2025.2486436. [↩]