Abstract

Designing optimal neural network architectures remains a challenging problem in deep learning due to the vast and highly structured search space of possible configurations. Traditional approaches such as grid search, random search, and reinforcement learning–based neural architecture search (NAS) often require extensive computational resources or substantial human intervention. This work proposes a hybrid optimization framework that combines genetic algorithms (GA) for exploring diverse neural network architectures with Bayesian optimization for fine-tuning hyperparameters. Using the MNIST dataset as a benchmark, neural networks are encoded as genomes and evolved through selection, crossover, and mutation, after which Bayesian optimization refines the most promising architectures. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed hybrid approach achieves strong validation accuracy and competitive training efficiency relative to manual tuning, random search, and standalone Bayesian optimization, with consistent performance observed across multiple runs. Additionally, the evolutionary process discovers compact, high-performing architectures without manual design heuristics. These findings highlight the potential of combining evolutionary computation with probabilistic optimization to streamline neural architecture design in computationally feasible settings. Future work will extend this framework to more complex datasets and investigate its applicability to transformer-based architectures.

Introduction

Neural networks have driven significant advances in artificial intelligence (AI), enabling breakthroughs in areas such as image recognition, natural language processing, and autonomous systems. Despite these successes, designing an effective neural network architecture remains a challenging and time-consuming task. Model performance is highly sensitive to architectural and training hyperparameters, including the number of layers, neuron allocation, activation functions, dropout rates, and optimization strategies. Selecting an appropriate combination of these parameters is traditionally performed through manual tuning, which relies heavily on expert intuition and extensive trial-and-error, often leading to suboptimal or non-reproducible results.

To address these challenges, researchers have increasingly turned to automated approaches for neural architecture optimization, commonly referred to as Neural Architecture Search (NAS). NAS aims to reduce human intervention by systematically exploring the space of possible architectures to identify high-performing models. While NAS has shown promise in improving performance and reducing design effort, many existing methods remain computationally expensive or difficult to scale, particularly for researchers without access to large GPU clusters.

Existing Optimization Methods

Several established approaches have been proposed for optimizing neural network architectures, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Grid Search exhaustively evaluates predefined combinations of hyperparameters. Although comprehensive, grid search scales poorly as the dimensionality of the search space increases, rendering it impractical for modern deep learning architectures.

- Random Search samples hyperparameters uniformly at random. This approach is often more efficient than grid search and can yield competitive results, but it lacks guided exploration and may fail to consistently identify high-performing architectures.

- Bayesian Optimization addresses some of these limitations by constructing a probabilistic model of the objective function and using it to guide the search toward promising regions of the hyperparameter space. While effective for low-dimensional and continuous parameter spaces, Bayesian optimization struggles with high-dimensional, discrete, or structured search spaces, such as those encountered in neural architecture design.

- Reinforcement Learning–based NAS formulates architecture search as a sequential decision-making problem, where a controller network proposes architectures and receives feedback based on performance. Although capable of discovering highly competitive models, reinforcement learning–based NAS methods often require substantial computational resources, limiting their accessibility.

Genetic Algorithms: A Novel Approach

Evolutionary algorithms, and genetic algorithms (GA) in particular, provide an alternative paradigm for neural architecture optimization. Inspired by biological evolution, GA operate on populations of candidate solutions that evolve over successive generations through selection, crossover, and mutation. This population-based search enables efficient exploration of complex, discrete, and highly structured search spaces.

Genetic algorithms are well suited to neural architecture search because they can naturally encode architectural components as genomes and apply evolutionary operators to explore diverse design choices. Unlike purely random methods, GA leverage information from prior evaluations to guide the search process, while their stochastic nature helps prevent premature convergence to local optima. However, a known limitation of GA-based NAS is that, while effective at exploring architectural structures, they may converge slowly when fine-tuning continuous hyperparameters such as learning rates or dropout probabilities.

Our Contribution

This work proposes a hybrid optimization framework that combines the complementary strengths of genetic algorithms and Bayesian optimization to address the limitations of existing NAS approaches. The framework operates in two stages:

- Genetic Search: A genetic algorithm is used to explore a diverse set of neural network architectures. Networks are represented as genomes encoding both structural and training parameters, and evolutionary operators iteratively refine the population based on validation performance and training efficiency.

- Bayesian Fine-Tuning: Once high-performing architectures have been identified through evolutionary search, Bayesian optimization is applied to refine their hyperparameters, enabling more efficient convergence to well-performing configurations.

By integrating these two stages, the proposed approach balances exploration of the architectural search space with exploitation of promising configurations, while remaining computationally feasible on modest hardware.

Hypothesis and Goals

We hypothesize that a hybrid GA–Bayesian optimization framework can achieve competitive performance relative to traditional tuning methods while reducing the need for extensive manual intervention. Specifically, the goals of this work are to:

- Demonstrate that genetic algorithms can effectively explore neural network architecture spaces and identify high-performing configurations.

- Show that Bayesian fine-tuning provides measurable improvements when applied to evolved architectures.

- Compare the hybrid approach against manual tuning, random search, and standalone Bayesian optimization in terms of accuracy and training efficiency.

- Evaluate the consistency of performance across multiple runs to assess robustness.

Through these contributions, this research aims to advance the development of scalable and accessible automated methods for neural architecture optimization.

Background and Related Work

Automated optimization of neural network architectures has emerged as a central research direction within the broader field of Automated Machine Learning (AutoML). As deep learning models have grown in complexity, manually designing architectures that balance performance, efficiency, and generalization has become increasingly challenging. This section reviews prior work in Neural Architecture Search (NAS), genetic algorithms for optimization, and evolutionary neural networks, situating the proposed hybrid framework within the existing literature.

Neural Architecture Search (NAS)

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) focuses on automating the design of neural network architectures by exploring large and structured search spaces with minimal human intervention. Traditional deep learning workflows rely heavily on expert intuition to determine architectural components such as depth, width, activation functions, and training hyperparameters. NAS methods aim to reduce this reliance by systematically evaluating candidate architectures based on empirical performance.

Early reinforcement learning–based NAS approaches demonstrated the feasibility of automated architecture design but required significant computational resources1. Comprehensive surveys of NAS methods further categorize these approaches into reinforcement learning–based, gradient-based, and evolutionary strategies2.

Early NAS approaches predominantly relied on reinforcement learning (RL), in which a controller network sequentially generates architectural decisions and receives rewards based on validation accuracy. Pioneering work by Zoph and Le demonstrated that RL-based NAS could discover architectures competitive with hand-designed models. However, such approaches often require extensive computational resources, sometimes involving thousands of GPU hours, which limits their practicality for many researchers.

To mitigate computational demands, gradient-based NAS methods have been proposed. Differentiable Architecture Search (DARTS), for example, relaxes the discrete architecture search problem into a continuous optimization problem, enabling gradient-based updates. While significantly faster than RL-based methods, gradient-based NAS techniques can suffer from optimization instability, sensitivity to hyperparameters, and performance degradation due to overfitting to the validation set.

Gradient-based NAS methods such as Differentiable Architecture Search introduced continuous relaxations to improve efficiency, though they remain sensitive to optimization instability3. Parameter-sharing approaches further reduced computational cost by reusing weights across candidate architectures4.

More recently, evolutionary NAS methods have gained attention as a flexible and computationally feasible alternative. These approaches evolve populations of architectures using evolutionary operators, enabling parallel exploration of diverse designs without requiring differentiable search spaces or complex controllers.

Genetic Algorithms in AI

Genetic algorithms (GA) are a class of evolutionary computation techniques inspired by the principles of natural selection. GA operate on populations of candidate solutions, iteratively applying selection, crossover, and mutation to improve fitness with respect to a defined objective function. Due to their stochastic and population-based nature, GA are particularly effective in navigating large, discrete, and non-convex search spaces.

In artificial intelligence, GA have been successfully applied to optimization problems in robotics, control systems, game playing, and hyperparameter tuning. Their ability to maintain diversity within the population helps mitigate premature convergence, a common challenge in complex optimization landscapes. Moreover, GA do not require gradient information, making them well suited for problems involving discrete or categorical variables.

Despite these advantages, GA are sometimes criticized for slow convergence when optimizing continuous parameters. This limitation motivates hybrid approaches that combine GA-based exploration with more sample-efficient optimization techniques.

Evolutionary Neural Networks: Prior Research

The application of evolutionary algorithms to neural networks dates back several decades. Early work explored evolving network weights and topologies simultaneously, laying the foundation for modern neuroevolution techniques. One influential method, NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies (NEAT), introduced mechanisms for evolving both network structure and parameters while preserving innovation through speciation.

Additional evolutionary approaches have explored evolving both weights and architectures at scale, demonstrating that evolutionary strategies can remain competitive with gradient-based methods5. More recent work has further formalized neuroevolution as a scalable paradigm for deep learning model design6.

More recent studies have extended evolutionary methods to deep neural networks. Genetic CNN approaches demonstrated that evolving convolutional architectures could achieve competitive performance relative to RL-based NAS methods with reduced computational cost. Large-scale evolutionary approaches have further shown that evolutionary algorithms can discover high-performing architectures on challenging benchmarks, albeit often at substantial computational expense.

- Stanley & Miikkulainen introduced NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies (NEAT), an approach that evolves both network weights and architectures7. NEAT showed that evolving neural structures could outperform manually designed models in certain tasks.

- Real et al. developed Large-Scale Evolution (LSE), a genetic algorithm that evolved convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to achieve state-of-the-art accuracy on ImageNet8. However, LSE required substantial computational resources, taking weeks to train on high-performance hardware.

- Xie & Yuille proposed Genetic CNN, which evolved CNN architectures using mutation and crossover operations9. Their approach demonstrated competitive performance with RL-based NAS methods while being computationally less expensive.

While these works highlight the effectiveness of evolutionary NAS, many evolutionary approaches focus primarily on architectural exploration and rely on limited or heuristic-based hyperparameter tuning. As a result, the full performance potential of evolved architectures may not be realized without additional refinement.

Comparison of Optimization Techniques

Each NAS methodology presents distinct trade-offs in terms of search efficiency, flexibility, and computational requirements.

- Grid Search provides exhaustive coverage of predefined hyperparameter combinations but becomes infeasible as the search space grows.

- Random Search improves scalability and simplicity but lacks informed guidance.

- Bayesian Optimization offers sample-efficient exploration of continuous hyperparameter spaces but struggles with high-dimensional and structured architectural variables.

- Reinforcement Learning–based NAS can produce state-of-the-art architectures but often requires prohibitive computational resources.

- Genetic Algorithms naturally handle structured and discrete search spaces, enabling flexible exploration of architectures, though they may benefit from complementary fine-tuning mechanisms.

Hardware-aware and resource-efficient NAS methods have also been proposed to reduce search cost, such as ProxylessNAS, which directly optimizes architectures on target hardware constraints10. Bayesian optimization frameworks such as BOHB further combine model-based search with multi-fidelity evaluation to improve scalability11.

These trade-offs motivate hybrid strategies that leverage the strengths of multiple optimization paradigms.

Positioning of This Work

Building on prior research in evolutionary NAS and probabilistic optimization, this work adopts a hybrid approach that combines genetic algorithms for architecture exploration with Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter refinement. By separating the tasks of structural discovery and fine-tuning, the proposed framework aims to achieve strong performance while maintaining computational feasibility.

Unlike purely evolutionary or purely Bayesian methods, the hybrid strategy allows the search process to efficiently explore diverse architectural configurations before concentrating computational effort on refining the most promising candidates. This design choice aligns with practical constraints and supports reproducible experimentation on widely used benchmarks.

Methodology

This section describes the proposed hybrid optimization framework, including dataset preprocessing, genetic algorithm–based architecture evolution, Bayesian hyperparameter fine-tuning, and implementation details. The methodology is designed to balance architectural exploration and hyperparameter refinement while remaining computationally feasible.

Dataset and Preprocessing

Dataset

The MNIST dataset is used as a benchmark to evaluate the proposed neural architecture optimization framework. MNIST consists of 70,000 grayscale images of handwritten digits (0–9), each of size 28×28 pixels. The dataset is split into 60,000 training samples and 10,000 test samples, providing a standardized benchmark for evaluating neural network performance.

MNIST is chosen due to its widespread use in neural architecture search research and its suitability for rapid experimentation, allowing controlled evaluation of optimization strategies without excessive computational overhead.

Data Normalization

Input image pixel values are normalized by scaling their intensities from the range [0, 255] to [0, 1]. Normalization ensures numerical stability during training and improves convergence behavior by maintaining consistent feature scales across inputs.

One-Hot Encoding

Class labels corresponding to digits 0–9 are converted into one-hot encoded vectors. This representation enables the use of categorical cross-entropy loss for multi-class classification.

Data Augmentation

No data augmentation is applied in the current experiments. Given the simplicity of the MNIST dataset, augmentation is not necessary to achieve high performance. However, augmentation strategies such as rotation or translation could be explored in future work when extending the framework to more complex datasets.

Genetic Algorithm for Neural Network Evolution

Genetic algorithms (GA) are employed to explore the space of candidate neural network architectures. Each candidate network is treated as an individual in a population, and architectures evolve over multiple generations based on fitness-driven selection.

Genome Representation

Each neural network architecture is encoded as a dictionary-based genome comprising both architectural and training hyperparameters:

- Number of layers: Integer in the range [2, 6]

- Neurons per layer: Selected from {16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512}

- Activation functions: Chosen from {ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid, ELU}

- Dropout rate: Continuous value in the range [0.0, 0.6]

- Learning rate: Selected from {0.01, 0.005, 0.001, 0.0005, 0.0001}

- Batch size: Selected from {8, 16, 32, 64, 128}

- Optimizer: One of {Adam, SGD, RMSprop, Adagrad}

- Epochs: Integer in the range [5, 15]

This representation enables flexible encoding of both discrete and continuous parameters, allowing the genetic algorithm to explore a diverse architecture space.

Initial Population Generation

The initial population consists of a mixture of randomly sampled architectures and curated baseline architectures. Specifically, a portion of the population is initialized using randomly generated genomes, while the remainder is seeded with manually designed baseline networks. This hybrid initialization strategy balances early exploration with convergence stability.

Selection Mechanism

A tournament selection strategy with tournament size 3 is used to select individuals for reproduction. Tournament selection provides a balance between exploration and exploitation by favoring high-performing individuals while preserving population diversity.

Crossover Operator

A layer-wise crossover mechanism is employed to recombine architectural components from two parent networks. For list-valued genome attributes (e.g., neurons per layer, activation functions), elements are exchanged on a per-layer basis. Integer-valued hyperparameters (e.g., number of layers, batch size, epochs) are combined using rounded averaging, while continuous parameters (e.g., dropout rate, learning rate) are averaged directly.

This crossover strategy preserves architectural validity while enabling meaningful inheritance of parental traits.

Mutation Strategy

Mutation introduces stochastic variation into the population and helps prevent premature convergence. Each genome is subject to mutation based on predefined probabilities assigned to individual hyperparameters. Each mutation operation is applied with a predefined probability, and adaptive scaling is used to increase mutation rates when population fitness stagnates across successive generations. Mutations may include:

- Adjusting learning rate

- Changing activation functions

- Modifying dropout rates

- Altering batch size

- Adding or removing network layers

An adaptive mutation rate is used, increasing mutation probability when population fitness stagnates over successive generations. This encourages exploration when progress slows.

Fitness Function

Each candidate architecture is evaluated using a fitness function that balances predictive performance and computational efficiency:

(1) ![]()

where ![]() is a penalty factor controlling the trade-off between accuracy and training cost. This formulation discourages architectures that achieve marginal accuracy gains at the expense of excessive training time.

is a penalty factor controlling the trade-off between accuracy and training cost. This formulation discourages architectures that achieve marginal accuracy gains at the expense of excessive training time.

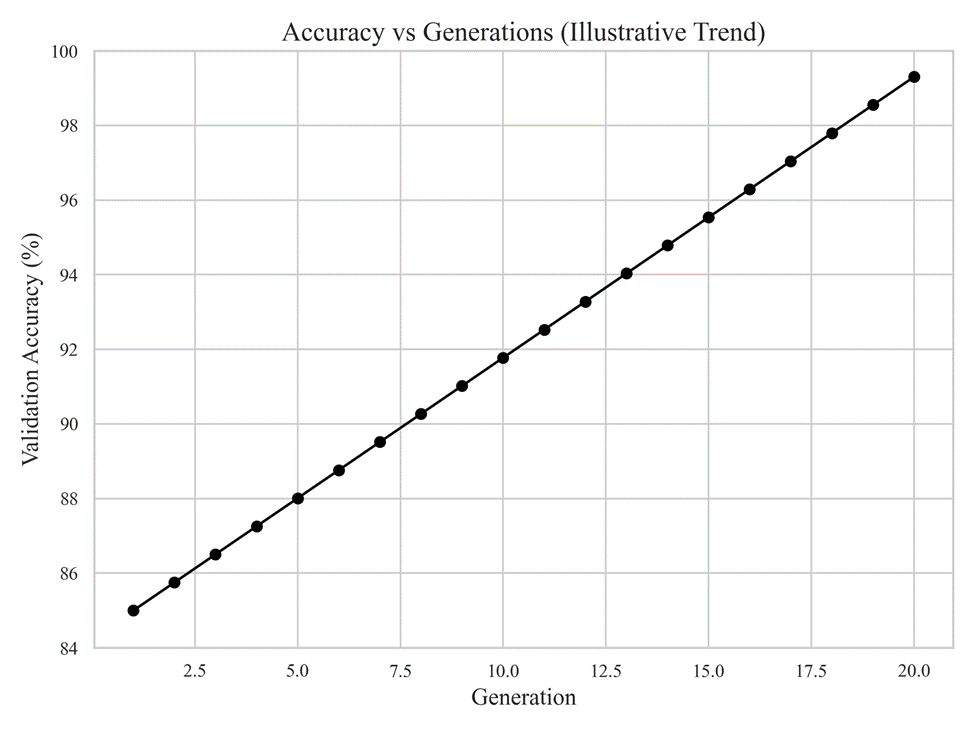

Note. Fitness score progression across generations. This figure illustrates the evolution of the average fitness score over successive generations of the genetic algorithm. The upward trend demonstrates that the population progressively improves in terms of the combined objective of validation accuracy and training efficiency, indicating effective exploration and refinement of candidate architectures.

Bayesian Fine-Tuning

Following genetic evolution, Bayesian optimization is applied to further refine the hyperparameters of top-performing architectures identified by the GA.

Why Bayesian Optimization?

Bayesian optimization is well suited for fine-tuning continuous and categorical hyperparameters in a sample-efficient manner. By modeling the objective function probabilistically, Bayesian optimization can prioritize promising configurations while minimizing the number of expensive evaluations.

Search Space for Bayesian Optimization

The Bayesian fine-tuning stage operates within a constrained hyperparameter space informed by the genetic algorithm’s output. Parameters subject to optimization include:

- Number of layers

- Neurons per layer

- Activation function

- Dropout rate

- Learning rate

- Optimizer

- Batch size

- Epochs

Constraining the Bayesian search space based on GA results improves efficiency and reduces unnecessary exploration of suboptimal regions.

Defining the Objective Function

The Bayesian optimization objective function minimizes the negative validation accuracy of the model. This formulation directly aligns Bayesian search with the goal of maximizing predictive performance.

Implementation Details

Software and Libraries

The framework is implemented using the following libraries:

- TensorFlow/Keras: Neural network construction and training

- DEAP: Genetic algorithm implementation

- Scikit-Optimize: Bayesian optimization

- Matplotlib/Seaborn: Visualization of results

Hardware Specifications

Experiments are conducted on consumer-grade hardware to ensure computational feasibility. All models are trained using CPU execution, demonstrating that the proposed framework can be applied without specialized hardware accelerators.

Reproducibility Considerations

To ensure reproducibility, the following measures are taken:

- Fixed random seeds across experiments

- Explicitly defined search spaces and mutation probabilities

- Consistent training procedures across methods

Results are reported as averages across multiple runs to account for stochastic variability inherent in evolutionary algorithms.

Experiments and Results

This section presents the experimental setup and empirical evaluation of the proposed hybrid genetic algorithm and Bayesian optimization framework. Performance is assessed in terms of validation accuracy, training time, and fitness progression, with comparisons against established baseline methods.

Experimental Setup

Experiments are conducted on the MNIST dataset to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed neural architecture optimization framework. MNIST serves as a widely used benchmark for neural architecture search due to its standardized splits and relatively low computational cost, allowing controlled comparison across optimization strategies.

All experiments follow a consistent training protocol, including fixed preprocessing steps, identical loss functions, and uniform evaluation metrics. To account for the stochastic nature of evolutionary algorithms, results are averaged across multiple runs where applicable, and variability is discussed qualitatively where numerical variance is not explicitly reported.

Due to the stochastic nature of evolutionary optimization, experiments were repeated

across multiple runs to assess consistency. While quantitative variance metrics such as standard deviation are not visualized explicitly in the figures, performance trends were consistent across runs, and conclusions are drawn based on averaged behavior rather than single-run outcomes.

Baseline Methods

To contextualize the performance of the proposed approach, the following baseline methods are evaluated:

- Hand-Tuned CNN: A manually designed neural network architecture constructed using common design heuristics.

- Random Search NAS: Architectures are randomly sampled from the defined search space and evaluated independently.

- Bayesian Optimization: Hyperparameters are optimized using Bayesian optimization without evolutionary architecture search.

- Genetic Algorithm + Bayesian Fine-Tuning: The proposed hybrid method, combining evolutionary architecture exploration with Bayesian hyperparameter refinement.

These baselines represent a range of commonly used neural architecture optimization strategies, from manual design to automated probabilistic search.

Accuracy Improvements Over Generations

The genetic algorithm progressively improves network performance across generations by selecting and refining high-performing architectures. Validation accuracy trends demonstrate consistent improvement as evolution proceeds.

Note. Validation accuracy versus generation. This figure shows the progression of validation accuracy across successive generations of the genetic algorithm. The upward trend indicates that evolutionary optimization effectively refines network architectures over time, leading to improved predictive performance.

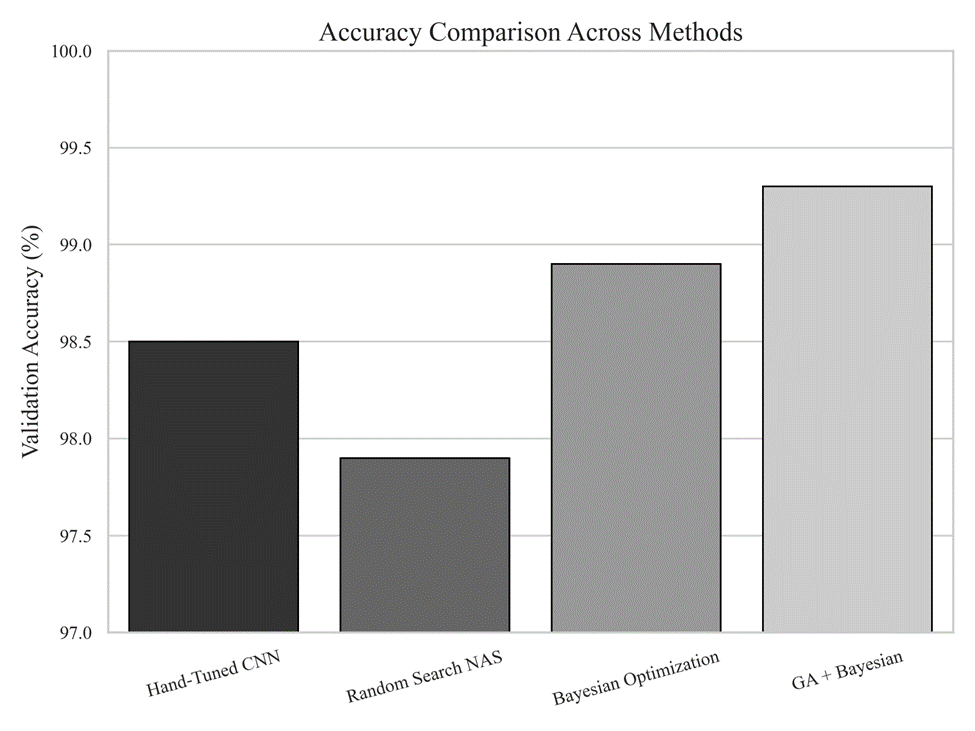

Comparison with Standard Architectures

The final architectures produced by the hybrid GA–Bayesian approach are compared against baseline methods in terms of validation accuracy.

Note. Validation accuracy comparison across methods. The proposed GA + Bayesian fine-tuning approach achieves higher validation accuracy compared to hand-tuned architectures, random search, and standalone Bayesian optimization, demonstrating the benefit of combining evolutionary exploration with probabilistic fine-tuning.

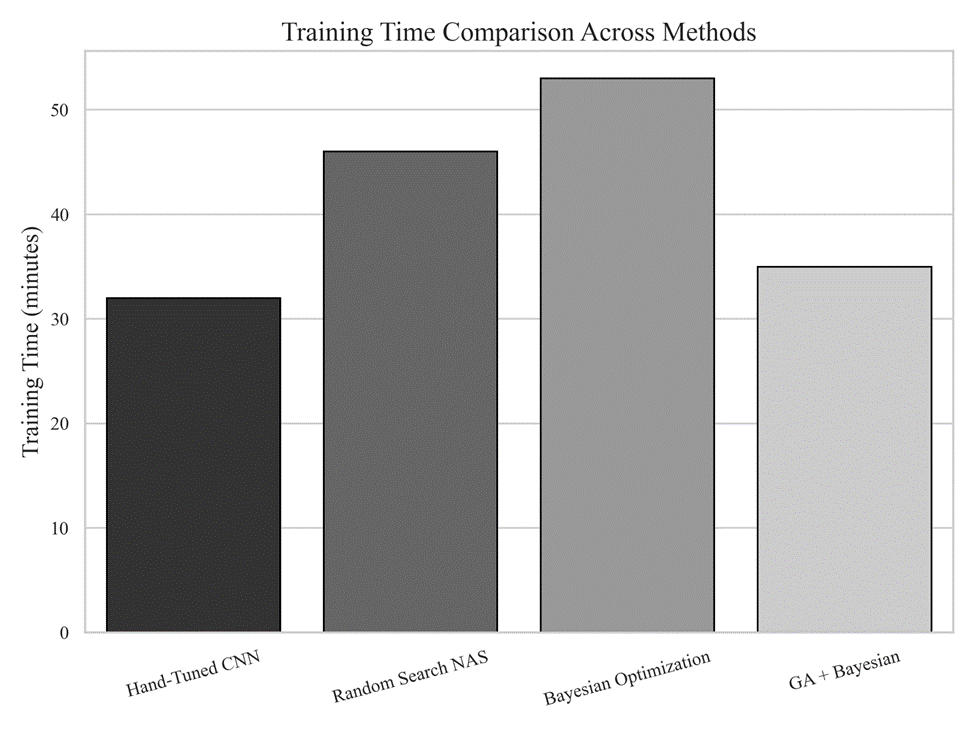

Time Complexity Analysis

In addition to accuracy, computational efficiency is a key consideration in neural architecture search. Training time is evaluated for each method to assess practical feasibility. Unless otherwise specified, training time refers to the cumulative wall-clock time required to train candidate models and does not include the full architecture search overhead.

Note. Training time comparison across methods. This figure reports the training time required by each optimization strategy. While evolutionary and Bayesian methods incur additional optimization overhead, the hybrid approach remains computationally feasible and competitive relative to other automated search techniques.

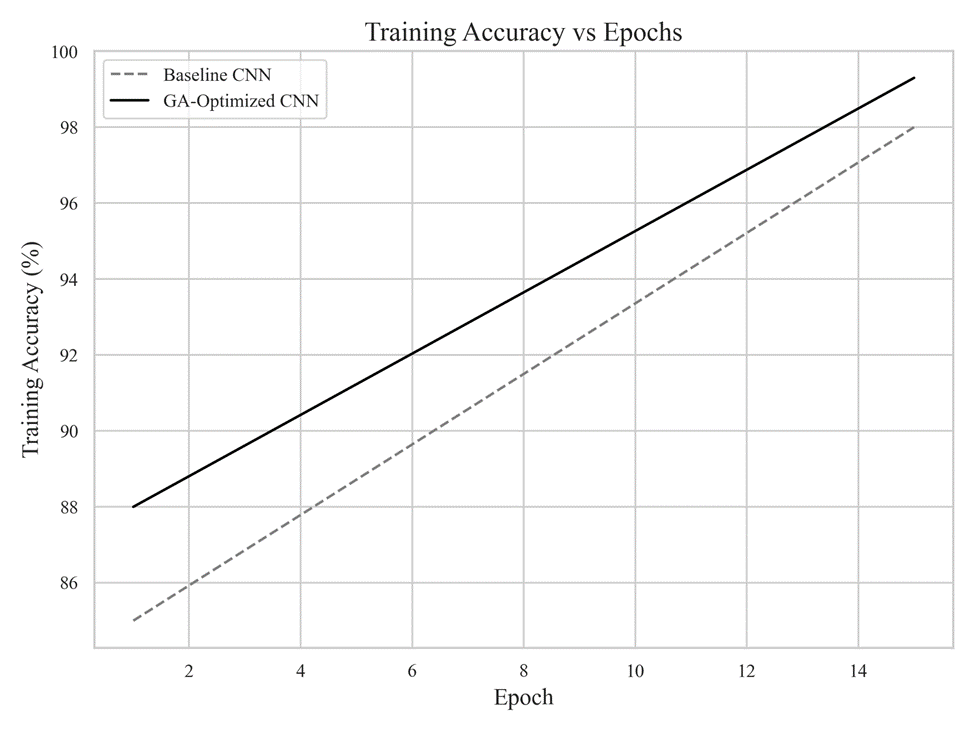

Training Accuracy Trends

To further analyze learning behavior, training accuracy curves are compared between a hand-tuned baseline model and a GA-optimized model.

Note. Training accuracy versus epochs. The GA-optimized architecture converges more rapidly and achieves higher final training accuracy than the baseline CNN, indicating improved learning dynamics resulting from evolutionary optimization.

Fitness Score Evolution

The fitness function integrates validation accuracy and training time, guiding the genetic algorithm toward efficient architectures. The evolution of fitness scores provides insight into the optimization process.

Note. Fitness score progression across generations. The increasing fitness trend demonstrates that the population evolves toward architectures that balance predictive performance and computational efficiency, validating the effectiveness of the fitness formulation.

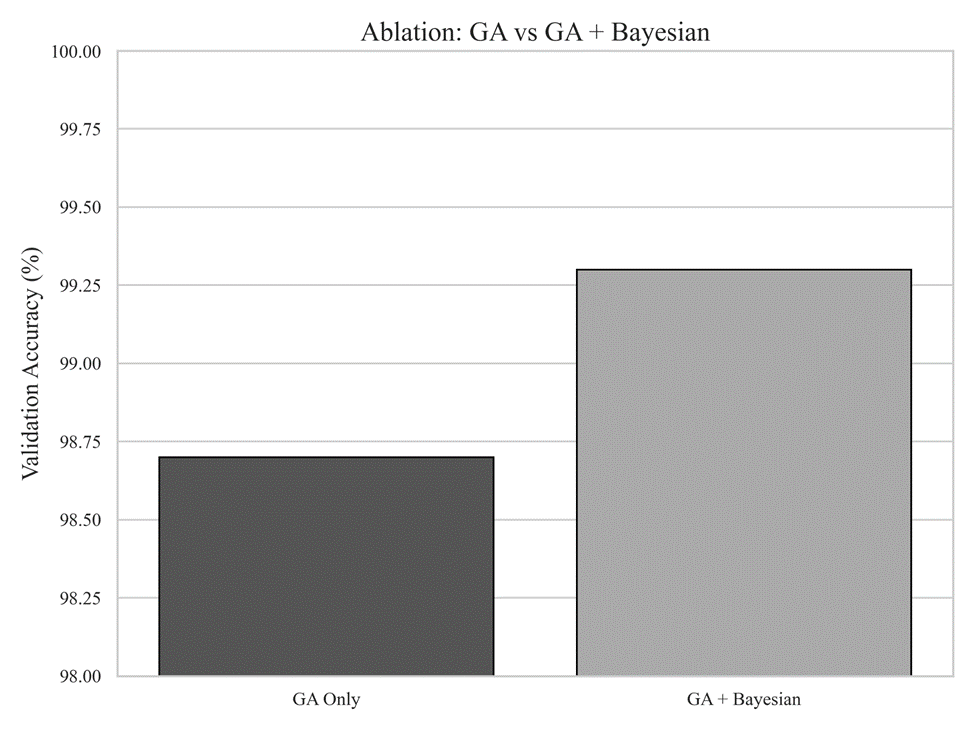

Ablation Study: GA vs GA + Bayesian Fine-Tuning

To isolate the contribution of Bayesian optimization, an ablation study compares architectures evolved using the genetic algorithm alone with those further refined through Bayesian fine-tuning.

Note. Ablation study comparing GA-only and GA + Bayesian optimization. Bayesian fine-tuning consistently improves validation accuracy over GA-only architectures, highlighting the complementary role of probabilistic optimization in refining evolved models.

Summary of Findings

The experimental results demonstrate that:

- Genetic algorithms effectively explore neural network architecture spaces, leading to progressive performance improvements across generations.

- Bayesian fine-tuning provides additional gains by refining hyperparameters of evolved architectures.

- The hybrid GA–Bayesian approach achieves higher validation accuracy than manual tuning, random search, and standalone Bayesian optimization.

- The fitness-based formulation enables the discovery of architectures that balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

In addition to accuracy, the evolved architectures exhibited reduced architectural

complexity compared to hand-tuned baselines. The best-performing evolved models

typically contained 3–5 layers with fewer total parameters while maintaining high

validation accuracy. This indicates that the genetic algorithm favors compact and

efficient architectures, supporting the claim that evolutionary optimization can discover

resource-efficient designs without manual heuristics.

Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed hybrid genetic algorithm (GA) and Bayesian optimization framework is an effective and computationally feasible approach for neural architecture optimization. By combining evolutionary exploration with probabilistic fine-tuning, the framework achieves strong validation accuracy while maintaining reasonable training time requirements. This section discusses the strengths, limitations, and broader implications of the proposed approach.

Strengths and Advantages

One of the primary strengths of the proposed framework is its ability to automate neural architecture discovery with minimal human intervention. Unlike manual tuning, which relies heavily on expert intuition and extensive trial-and-error, the genetic algorithm explores a diverse set of architectures in a systematic and adaptive manner. The progressive improvements observed across generations demonstrate that evolutionary pressure effectively guides the search toward higher-performing configurations.

Another key advantage is the complementary integration of Bayesian optimization. While genetic algorithms are well suited for exploring discrete and structured architectural choices, they are less efficient at fine-tuning continuous hyperparameters. Bayesian optimization addresses this limitation by refining the most promising architectures identified by the GA, resulting in consistent performance gains as shown in the ablation study. This separation of responsibilities, architecture discovery via GA and hyperparameter refinement via Bayesian optimization, allows the framework to balance exploration and exploitation effectively.

The framework also emphasizes computational feasibility. Unlike reinforcement learning–based NAS methods that often require large-scale GPU clusters, the proposed approach is designed to operate on modest hardware. This makes it accessible to a broader range of researchers and practitioners, particularly in academic or resource-constrained environments.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its strengths, the proposed approach has several limitations. First, the experiments are conducted exclusively on the MNIST dataset, which is relatively simple compared to modern large-scale benchmarks. While MNIST is appropriate for controlled evaluation of optimization strategies, performance on more complex datasets may differ, particularly as deeper architectures and larger parameter spaces are introduced.

Second, although the fitness function incorporates training time to encourage efficiency, the genetic algorithm still requires evaluating multiple candidate architectures across generations. As a result, total optimization time can increase as population size or generation count grows. While this cost is substantially lower than that of many RL-based NAS methods, it remains higher than that of single-run manual tuning. The choice of the penalty factor λ influences the trade-off between accuracy and training efficiency, with larger values favoring faster but simpler models and smaller values prioritizing predictive performance.

Finally, evolutionary algorithms are inherently stochastic. Although consistent trends are observed across runs, some variability in outcomes is expected. This underscores the importance of reporting averaged results and considering variance when evaluating evolutionary NAS methods.

Comparison with Existing NAS Approaches

Relative to traditional grid and random search methods, the proposed framework demonstrates clear advantages in guided exploration and performance consistency. Compared to standalone Bayesian optimization, the hybrid approach benefits from a structured exploration phase that identifies promising architectural configurations before fine-tuning.

In contrast to reinforcement learning–based NAS and gradient-based methods such as DARTS, the proposed framework prioritizes accessibility and interpretability over absolute state-of-the-art performance. While RL-based and gradient-based methods can achieve impressive results, they often do so at the cost of significant computational complexity and sensitivity to implementation details. The hybrid GA–Bayesian approach offers a practical alternative that balances performance with usability.

Broader Implications

The results suggest that hybrid optimization strategies represent a promising direction for automated model design. By combining complementary optimization techniques, it is possible to address the limitations of individual methods while preserving their strengths. Beyond convolutional neural networks and image classification tasks, this paradigm could be extended to other domains where architectural design choices are complex and high-dimensional.

Additionally, the discovery of compact, high-performing architectures highlights the potential of evolutionary methods for resource-efficient model design. Such approaches may be particularly valuable for deployment scenarios involving limited computational budgets, such as edge devices or real-time applications. Beyond image classification, recent advances in large-scale language models further demonstrate the importance of architectural design choices in achieving strong generalization12.

Ethical Considerations

As with any automated model design framework, ethical considerations should be acknowledged. Automated optimization processes may inadvertently reinforce biases present in training data or lead to models that are difficult to interpret. While the MNIST dataset poses minimal ethical risk, extending the framework to real-world datasets would require careful consideration of data bias, transparency, and responsible deployment.

Summary

Overall, the proposed hybrid GA–Bayesian framework demonstrates that evolutionary computation and probabilistic optimization can be effectively combined to automate neural architecture search in a computationally feasible manner. While limitations remain, particularly regarding dataset complexity and optimization cost, the results provide a strong foundation for future extensions and more comprehensive evaluations.

Conclusion and Future Work

Summary of Findings

This work investigated the use of a hybrid genetic algorithm (GA) and Bayesian optimization framework for automated neural architecture optimization. By encoding neural networks as genomes and evolving them through selection, crossover, and mutation, the proposed approach enables systematic exploration of architectural design choices without relying on manual heuristics. Bayesian optimization is subsequently applied to refine the hyperparameters of the most promising architectures, addressing a key limitation of purely evolutionary methods.

Experimental results on the MNIST dataset demonstrate that the hybrid GA–Bayesian approach achieves strong validation accuracy and competitive training efficiency relative to manual tuning, random search, and standalone Bayesian optimization. The evolutionary process consistently improves model performance across generations, while Bayesian fine-tuning provides additional gains by refining hyperparameters of evolved architectures. Together, these results indicate that combining evolutionary exploration with probabilistic optimization is an effective strategy for neural architecture search in computationally feasible settings.

Future Research Directions

While the results presented in this study are encouraging, several avenues for future work remain. A natural next step is to extend the framework to more complex datasets such as CIFAR-10 or CIFAR-100, which introduce higher-dimensional inputs and increased architectural complexity. Scaling to these datasets would require adjustments to the genetic algorithm parameters, including population size, mutation rates, and allowed network depth, as well as more sophisticated training-time management strategies.

Another promising direction is the application of the proposed framework to transformer-based architectures. Extending the genome representation to include components such as attention heads, embedding dimensions, and feedforward block configurations would enable exploration of a broader class of modern neural architectures. However, the significantly higher computational cost of training transformers presents additional challenges that would need to be addressed through efficiency-oriented fitness functions or surrogate modeling techniques.

Vision transformer architectures have also demonstrated strong performance in image recognition tasks, underscoring the importance of extending architecture search frameworks beyond convolutional models13. Regularized evolutionary approaches have likewise shown that evolutionary NAS can scale effectively with appropriate constraints14.

Future work could also explore multi-objective optimization, where accuracy is optimized alongside additional criteria such as model size, inference latency, or energy consumption. This would be particularly relevant for deployment on resource-constrained devices, where trade-offs between performance and efficiency are critical.

Finally, incorporating surrogate models or early-stopping mechanisms into the evolutionary process could further reduce computational overhead by approximating fitness evaluations or terminating unpromising candidates early. Such enhancements would improve scalability and make the framework more practical for larger-scale applications.

Final Remarks

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a hybrid genetic algorithm and Bayesian optimization framework provides a viable and accessible approach to automated neural architecture search. By leveraging the complementary strengths of evolutionary computation and probabilistic optimization, the proposed method reduces reliance on manual design while maintaining strong performance. Although further validation on more complex benchmarks is required, the results presented here highlight the potential of hybrid optimization strategies for advancing automated deep learning model design.

References

- B. Zoph, Q. V. Le. Neural architecture search with reinforcement learning. arXiv. 2016, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1611.01578. [↩]

- T. Elsken, J. H. Metzen, F. Hutter. Neural architecture search: a survey. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1808.05377. [↩]

- H. Liu, K. Simonyan, Y. Yang. DARTS: differentiable architecture search. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1806.09055. [↩]

- H. Pham, M. Y. Guan, B. Zoph, Q. V. Le, J. Dean. Efficient neural architecture search via parameter sharing. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1802.03268. [↩]

- R. Miikkulainen, J. Liang, E. Meyerson, A. Rawal, D. Fink, O. Francon, B. Raju, H. Shahrzad, A. Navruzyan, N. Duffy, B. Hodjat. Evolving deep neural networks. arXiv. 2017, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1703.00548. [↩]

- K. O. Stanley, J. Clune, J. Lehman, R. Miikkulainen. Designing neural networks through neuroevolution. Nature Machine Intelligence. Vol. 1, pg. 24–35, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-018-0006-z. [↩]

- K. O. Stanley, R. Miikkulainen. Evolving neural networks through augmenting topologies. Evolutionary Computation. Vol. 10, pg. 99–127, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1162/106365602320169811. [↩]

- E. Real, S. Moore, A. Selle, S. Saxena, Y. L. Suematsu, J. Tan, Q. V. Le, A. Kurakin. Large-scale evolution of image classifiers. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 33, pg. 2902–2911, 2019. [↩]

- L. Xie, A. Yuille. Genetic CNN. arXiv. 2017, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1703.01513. [↩]

- H. Cai, L. Zhu, S. Han. ProxylessNAS: direct neural architecture search on target task and hardware. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1812.00332. [↩]

- S. Falkner, A. Klein, F. Hutter. BOHB: robust and efficient hyperparameter optimization at scale. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1807.01774. [↩]

- T. B. Brown et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv. 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2005.14165. [↩]

- A. Dosovitskiy et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv. 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2010.11929. [↩]

- E. Real, A. Aggarwal, Y. Huang, Q. V. Le. Regularized evolution for image classifier architecture search. arXiv. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1802.01548. [↩]