Abstract

Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae is a major driver of hospital mortality and healthcare costs, with a growing association with antibiotic treatment failures. Recent studies indicate that certain synthetic antimicrobial peptides can combat K. pneumoniae and represent a promising avenue for new therapeutics. Together, these findings underscore the urgent need for new antimicrobial development. This study aimed to computationally design novel antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) through two strategies using AI: (1) shortening amino acid length and (2) substituting polar uncharged or non-polar neutral residues and the structurally flexible glycine with positively charged or hydrophobic amino acids, while maintaining balanced hydrophobicity to improve predicted antimicrobial activity and reduce predicted toxicity. We chose a low-performing candidate with weak predicted AMP probability (predicted AMP probability=0.531) and high predicted toxicity (predicted toxicity hybrid score=0.5) in the GRAMPA database, and used AI-driven tools (CAMPR3/4, AlphaFold, APD3, DBAASP, HeliQuest) to generate 243 variants via single-site substitutions and assess their properties. Top candidates were further optimized using ToxinPred3.0, generating 381 variants by introducing additional single amino acid substitutions in the highest-scoring sequence to reduce predicted toxicity while maintaining antimicrobial activity. The final peptide achieved a high predicted AMP probability score (predicted AMP probability=1) and zero predicted toxicity (predicted toxicity hybrid score=0) but its predicted reduced membrane-insertion potential indicates areas for future improvement. These findings demonstrate the potential and effectiveness of computational design in accelerating the development of peptide-based therapeutics. By enabling time- and cost-efficient AMP discovery, this approach may accelerate the development of viable antibiotic alternatives and help reduce the health burden posed by K. pneumoniae infections.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, Klebsiella pneumoniae, antimicrobial activity, toxicity, computational design.

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen that normally resides in the human gut but can cause severe infections when it spreads systemically. It poses a major threat in healthcare settings, particularly among vulnerable patients, and is one of the six highly drug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens—Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species—that are increasingly associated with antibiotic treatment failure1. K. pneumoniae is responsible for a range of infections—including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and liver abscesses—and was estimated to have caused 176,000 deaths globally from lower respiratory infections in 20212‘3. A meta-analysis of nearly 38,000 patients reported 30-day and 90-day mortality rates of 29% and 34%, respectively, with higher risks in ICU and hospital-acquired cases4. Another meta-analysis across 14 countries found that 29% of K. pneumoniae infections involve carbapenem-resistant strains (CRKP), with prevalence reaching 66% in low-income regions such as South Asia, compared to 14% in high-income areas like North America5. Misuse of antibiotics accelerates bacterial resistance, which spreads as bacteria evolve and share resistance genes via plasmids6.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) offer a promising alternative due to their broad efficacy, reduced resistance risk, and immune-enhancing properties7. AMPs disrupt bacterial membranes and/or interfere with intracellular processes, causing cell rupture or increased permeability that enhances antibiotic effectiveness and making resistance development less likely8.

Recent research shows that certain synthetic antimicrobial peptides have potential for treating K. pneumoniae by reducing the abundance of proteins involved in DNA and protein metabolism, cytoskeleton and cell wall organization, redox metabolism, regulatory factors, ribosomal proteins, and antibiotic resistance—suggesting that AMPs may act through multiple mechanisms, help mitigate resistance development, and offer a potent strategy for new drug development against K. pneumoniae infections9. For example, antimicrobial peptide A20L has shown potential against K. pneumoniae by demonstrating in vitro and in vivo antibacterial and antibiofilm activity, membrane-disruptive mechanisms, low toxicity, and good stability under certain conditions10. Another example, FK5P—an ultra-short palmitoylated 5-mer phenylalanine:lysine random peptide mixture—effectively killed carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, disrupted biofilms, reduced bacterial burden in mice, and exhibited strong safety and pharmacokinetic profiles, highlighting its promise as a therapeutic agent11.

This study computationally investigates the design of novel antimicrobial peptides targeting K. pneumoniae using AI tools to optimize peptide structure. We hypothesize that amino acid length shortening and substitutions can increase predicted AMP probability and reduce predicted toxicity. Specifically, through two strategies — (1) shortening amino acid length, and (2) substituting polar uncharged or non-polar neutral residues and the structurally flexible glycine with positively charged or hydrophobic amino acids while maintaining a balanced hydrophobic/hydrophilic profile — we aim to computationally enhance antimicrobial efficacy by reducing hemolytic activity, improving selectivity, maintaining hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance, and increasing stability. Importantly, the results are based on computational predictions, and changes in biological efficacy or toxicity should not be implied without experimental validation.

This paper is structured as follows: Section II outlines the methods used to apply AI tools for amino acid length shortening and substitution in peptide design computationally; Section III presents the results showing improved predicted AMP probability and reduced predicted toxicity; Section IV discusses the significant implications and broader applicability of the research; and Section V concludes. While the findings are based on computational simulations, they may help inform future efforts to develop safer and more effective AMPs against K. pneumoniae, and guide the design of experimental validation studies.

Literature Review

Rising drug discovery costs and the need for new antibiotics have increased interest in antimicrobial peptides, with computational methods complementing experimental screening and enabling exploration of novel chemical spaces12. Existing research shows that AI is accelerating antimicrobial peptide discovery by enabling novel designs and supporting preclinical validation13. Meanwhile, computer-aided drug design (CADD) is limited by model assumptions, incomplete data, high computational costs, and inability to fully predict pharmacokinetics or toxicity, requiring experimental validation14. Future efforts aimed at improving predictive model accuracy, mitigating biases in AI algorithms, and integrating diverse biological data could enhance CADD’s effectiveness and its contribution to antimicrobial peptide development15.

AI-designed antimicrobial peptides show potential as effective and safe alternatives to traditional antibiotics, with peptide modifications enhancing antimicrobial activity and yielding promising candidates for future therapeutic development. Large language model–based screening has been used to evaluate millions of peptides, identify promising candidates, and engineer more selective variants by increasing amphipathicity through targeted modifications, resulting in peptides with stronger antimicrobial activity but slightly reduced selectivity and demonstrating how AI can accelerate the discovery of new peptide antibiotics16. Similarly, AI-generated and optimized peptides have been shown to exhibit strong antimicrobial activity, with many displaying MICs below 10 μM and some demonstrating anticancer activity, indicating that peptide modifications can enhance biological effectiveness while remaining safe17.

Among the many strategies for optimizing antimicrobial peptides, two approaches are shortening amino acid length and substituting specific amino acids to modify their properties. These approaches can improve peptide activity and safety. Shorter antimicrobial peptides often exhibit lower hemolytic activity and toxicity, and truncated versions have been developed that retain antimicrobial effectiveness. Some of these peptides show broad-spectrum antibacterial effects, while others are more selective against Gram-positive bacteria, and they generally remain safer and more cost-efficient than the original parent peptide18. Balancing hydrophobicity and charge distribution in cationic antimicrobial peptides can enhance their membrane-disrupting activity, providing a framework for designing effective therapeutic agents19. Using a model α-helical antimicrobial peptide as a framework, single amino acid substitutions were introduced to examine their effects on charge, hydrophobicity, and helicity, revealing that changes in hydrophobicity influenced biological activity without altering secondary structure and demonstrating a rational design strategy for enhancing antimicrobial peptide activity20.

Computational approaches are increasingly being used to aid the discovery and design of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) against drug-resistant bacteria such as K. pneumoniae. Machine learning screening, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations were combined to identify potential antibiofilm AMPs, with several candidates showing stronger binding to the biofilm regulator MrkH than its native ligand, demonstrating the power of ML and simulation in discovering novel peptides21. Deep learning–based peptide language models were also used to design and test broad-spectrum AMPs, identifying peptides such as T2-9 that are highly effective against drug-resistant K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, with some also reducing resistance and treating infections in a mouse wound model22. Similarly, the Controlled Latent Attribute Space Sampling (CLaSS) computational framework was used to design non-toxic AMPs, leading to the identification of novel peptides with broad-spectrum potency, activity against drug-resistant K. pneumoniae, low toxicity, and resistance-mitigating properties23.

Methods

AMPs are small proteins composed of amino acid chains—the fundamental building blocks of all proteins—and are considered promising alternatives to antibiotics due to their ability to disrupt bacterial membranes in ways that reduce the likelihood of resistance. Their activity is shaped by the chemical properties of the 20 standard amino acids, which vary in charge, polarity, and hydrophobicity. Among them, arginine (R), lysine (K), and histidine (H) are positively charged; aspartic acid (D) and glutamic acid (E) are negatively charged. The polar but uncharged amino acids include serine (S), threonine (T), asparagine (N), glutamine (Q), tyrosine (Y), and cysteine (C). The remaining nonpolar, hydrophobic residues—important for membrane interaction—are glycine (G), alanine (A), valine (V), leucine (L), isoleucine (I), methionine (M), phenylalanine (F), proline (P), and tryptophan (W). The composition and distribution of these residues determine an AMP’s antimicrobial activity, selectivity, and toxicity. Key features such as net charge, hydrophobicity, and the ability to form amphipathic structures are crucial for enabling AMPs to target bacterial membranes while sparing host cells8.

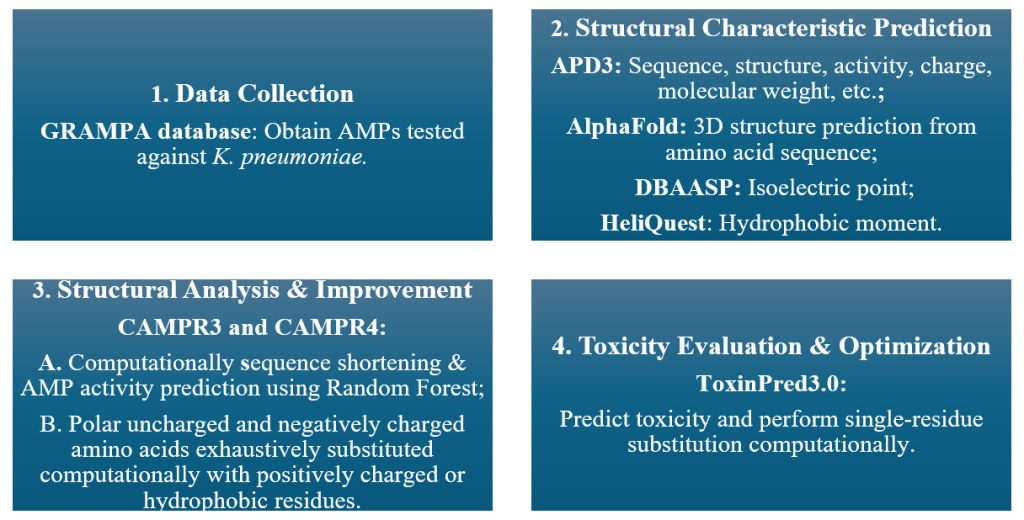

In this study, AMPs active against K. pneumoniae were retrieved from the Giant Repository of AMP Activities (GRAMPA) database and analyzed using various AI tools to evaluate their sequence, structure, activity, and toxicity, guiding the computational design of a new peptide with improved efficacy (Figure 1). GRAMPA is a database of antimicrobial peptides that provides their amino acid sequences and corresponding minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against various bacterial strains, including target species and strain-level details. From GRAMPA database, peptides tested against the bacterium K. pneumoniae were examined to identify patterns in activity and to guide the computational design of new and improved AMPs. The Antimicrobial Peptide Database (APD3), a searchable database of innate immune peptides, was used to gather detailed information—including sequence, structure, activity, source, and physicochemical properties like total net charge and molecular weight computationally. AlphaFold, an AI system developed by DeepMind, was used to predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of proteins based on input amino acid sequences. The Database of Antimicrobial Activity and Structure of Peptides (DBAASP), a manually curated resource developed to support the computational design of antimicrobial compounds with a high therapeutic index, was used to obtain the isoelectric point of peptides. HeliQuest, a bioinformatics tool for analyzing the amphipathic and structural properties of α-helical peptides, was used to calculate the predicted hydrophobic moment and generate helix wheels24. Collection of Anti-Microbial Peptides Release 3 (CAMPR3), a database of sequences, structures, and signatures of antimicrobial peptides, was used to computationally shorten the peptide sequence length applying the Random Forest algorithm; and CAMPR4, a subsequent release which expands and accelerates AMP based studies by providing curated information on natural and synthetic AMPs, was used to predict the novel peptide’s activity also applying the Random Forest algorithm. ToxinPred3.0, a web server that predicts peptide toxicity based on primary sequence using machine learning models, was used to obtain predicted toxicity scores and improve selectivity by replacing one amino acid through targeted substitution computationally. In ToxinPred3.0, toxicity scores range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater toxicity; this study used a 0.38 cutoff, and scores are probabilistic and require experimental validation. AlphaFold is a web service powered by AlphaFold 3 that generates highly accurate 3D structure predictions for proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, ions, and chemical modifications in a single platform (https://alphafoldserver.com/).

A dataset of peptide reported against the bacterium K. pneumoniae and meeting the CAMPR3 sequence length requirement was used for this study. A peptide active against K. pneumoniae but with a relatively weak predicted antimicrobial performances, characterized by a high predicted MIC and a relatively low predicted AMP score, was selected for improvement. Its existing activity against K. pneumoniae, combined with suboptimal predicted efficacy, made it a suitable candidate for optimization. Three steps were taken to increase its predicted antimicrobial potential and reduce predicted toxicity. First, the peptide sequence was shortened from 25 to 20 amino acids computationally. Second, polar uncharged and negatively charged amino acids were computationally substituted with positively charged or hydrophobic residues to enhance predicted antimicrobial activity and AMP scores. Third, predicted peptide toxicity was further minimized through targeted substitutions computationally.

A 20-residue peptide was chosen because many AMPs are around this length and shorter peptides are generally easier and cheaper to synthesize. Other lengths were not explored in this project which is a limitation and could be examine in future work. Amino acid substitutions were conducted because of three reasons: first, introducing positively charged residues (K, R, H) can enhance binding to negatively charged bacterial membranes; second, increasing hydrophobic residues can help the peptide insert into and disrupt membranes; and third, replacing very flexible residues like glycine with residues that favor helices can help stabilize an ![]() -helical structure.

-helical structure.

Results

From the GRAMPA database, 200 AMPs targeting K. pneumoniae were obtained. The AMP probability of each peptide was predicted computationally using CAMPR3 with the Random Forest classifier. Four peptides were excluded from the dataset due to sequence lengths shorter than four amino acids as indicated by CAMPR3, leaving 196 peptides for further analysis.

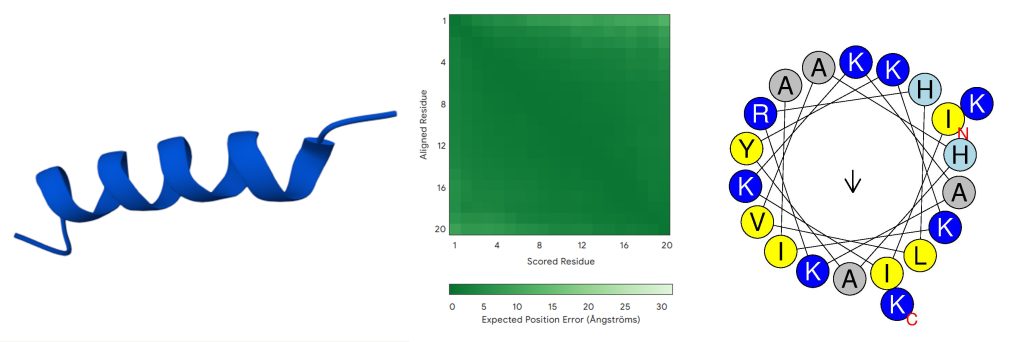

K. pneumoniae K6 (ATCC 700603, ‘‘GVFDIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEKV’) is a clinical isolate resistant to oxyimino-beta-lactams, used as a quality control strain for detecting extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) due to clavulanic acid–mediated MIC reduction25. The sequence exhibited one of the highest predicted MIC values (300 ![]() ) and one of the lowest predicted AMP probability scores (0.531), and was selected for mutational optimization. Table 1 summarizes its key characteristics, including a low predicted antimicrobial probability, high predicted MIC, low predicted net positive charge (+1), and high predicted toxicity (0.5). Figure 2 shows the predicted 3D structure and helix wheel of the initial peptide, as generated by AlphaFold and HeliQuest, respectively (default settings applied).

) and one of the lowest predicted AMP probability scores (0.531), and was selected for mutational optimization. Table 1 summarizes its key characteristics, including a low predicted antimicrobial probability, high predicted MIC, low predicted net positive charge (+1), and high predicted toxicity (0.5). Figure 2 shows the predicted 3D structure and helix wheel of the initial peptide, as generated by AlphaFold and HeliQuest, respectively (default settings applied).

| Strain | MIC (µg/mL) | Net Charge | Molecular Weight (Da) | Isoelectric point | Type of Structure | Hydrophobic moment | AMP Probability | Toxicity Hybrid Score |

| ATCC 700603 | 300 | 1 | 2667.166 | 9.81 | α-helical | 0.268 | 0.531 | 0.5 |

Note: For the 3D structure, dark blue stands for very high (pLDDT>90); light blue stands for confident (90>pLDDT>70); yellow stands for low (70>pLDDT>50); and orange stands for very low (pLDDT<50).

The initial peptide sequence (‘GVFDIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEKV’), consisting of 25 residues, was computationally shortened to 20 residues using CAMPR3 with the Random Forest algorithm. Table 2 shows the results from the ‘Predict Antimicrobial Region within Peptides’ tool. The shortened sequence ‘IIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEK’ (positions 5–24) showed the highest AMP probability and was selected for further mutation and optimization.

| Position | Sequence | Class | AMP Probability |

| 1-20 | GVFDIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGK | AMP | 0.676 |

| 2-21 | VFDIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKI | AMP | 0.689 |

| 3-22 | FDIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIA | AMP | 0.691 |

| 4-23 | DIIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAE | AMP | 0.547 |

| 5-24 | IIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEK | AMP | 0.859 |

| 6-25 | IKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEKV | AMP | 0.811 |

In the shortened sequence ‘‘IIKDAGRQLVAHAMGKIAEK’, amino acids with polar uncharged side chains (Q) and the negatively charged amino acids (D and E) and the structurally flexible glycine (G) were computationally substituted with amino acids bearing positively charged side chains (R; H; and K) to enhance the predicted AMP probability. An exhaustive set of 243 combinations 35, corresponding to substitutions at five positions 4-D, 6-G, 8-Q, 15-G, and 19-E) was generated. The sequence ‘IIKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK’, achieved the highest predicted AMP probability score (0.968) according to CAMPR3.

Although the newly created sequence ‘IIKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK’ was predicted to be non-toxic (toxicity score: 0.155) by ToxinPred3.0, the tool was further utilized to guide single amino acid substitutions aimed at reducing predicted toxicity and optimizing the peptide’s predicted antimicrobial profile—potent against the target pathogen while remaining safe for host cells. A total of 381 mutants were generated computationally, among which ten were predicted to have zero toxicity and AMP probability above 0.90. Here, a toxicity score of 0 indicates a non-toxic prediction by the ToxinPred3.0 model rather than experimentally confirmed absence of toxicity. The ten sequences with the lowest predicted toxicity scores (from ToxinPred3.0) and their corresponding predicted AMP probabilities (from CAMPR4) are presented in Table 3. The remaining 371 sequences were excluded due to high predicted toxicity or low AMP probability, and therefore not presented for brevity.

| Mutant ID | Sequence | Class | Predicted AMP Probability | Predicted MERCI (+ve) score | Predicted MERCI (-ve) score | Toxicity prediction |

| Mutant_K6D | IIKKADRHLVAHAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.91 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_I17E | IIKKAKRHLVAHAMKKEAKK | AMP | 0.91 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_H12D | IIKKAKRHLVADAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.92 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_I2D | IDKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.93 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_M14D | IIKKAKRHLVAHADKKIAKK | AMP | 0.97 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_I2Y | IYKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.99 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_K3Y | IIYKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.99 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_H12Y | IIKKAKRHLVAYAMKKIAKK | AMP | 0.99 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_K19Y | IIKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAYK | AMP | 0.99 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

| Mutant_M14Y | IIKKAKRHLVAHAYKKIAKK | AMP | 1 | 0 | -0.5 | 0 |

The sequence ‘IIKKAKRHLVAHAYKKIAKK’ (last sequence in Table 3) combines high predicted AMP probability and minimal predicted toxicity. MERCI (+ve) and (−ve) scores are motif-based predictors of antimicrobial potential, with (+ve) indicating AMP-like motifs (0 to +1) and (−ve) indicating non-AMP motifs (−1 to +1); the peptide showed a (−ve) score of −0.5 and a (+ve) score of 0, suggesting minimal non-AMP motifs and moderate AMP-associated motifs, consistent with its predicted antimicrobial activity. Compared with the peptide before single amino acid substitutions (‘IIKKAKRHLVAHAMKKIAKK’), Methionine (M) is replaced by Tyrosine (Y) at position 14. Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics of this optimized peptide, including its AMP probability score (1), predicted toxicity score (0), net positive charge (+8.5), and predicted ![]() -helical structure. Figure 3 presents the predicted 3D structure and Helix wheel of this final candidate.

-helical structure. Figure 3 presents the predicted 3D structure and Helix wheel of this final candidate.

| Net Charge | Molecular Weight (Da) | Type of Structure | Hydrophobic moment | AMP Probability | Toxicity Hybrid Score |

| + 8.5 | 2344.94 | α-helical | 0.201 | 1 | 0 |

Note: For the 3D structure, dark blue stands for very high (pLDDT>90); light blue stands for confident (90>pLDDT>70); yellow stands for low (70>pLDDT>50); and orange stands for very low (pLDDT<50).

For reference, the optimized peptide was compared with the widely studied human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37 (‘LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES’). Table 5 summarizes the key characteristics of this optimized peptide, including its AMP probability score (0.749), predicted toxicity score (0), net positive charge (+6.0), and predicted ![]() -helical structure. Figure 4 presents the predicted 3D structure and Helix wheel of this final candidate.

-helical structure. Figure 4 presents the predicted 3D structure and Helix wheel of this final candidate.

| Strain | Net Charge | Molecular Weight (Da) | Type of Structure | Hydrophobic moment | AMP Probability | Toxicity Hybrid Score |

| LL-37 | +6.0 | 4493.312 | α-helical | 0.521 | 0.749 | .0 |

Note: For the 3D structure, dark blue stands for very high (pLDDT>90); light blue stands for confident (90>pLDDT>70); yellow stands for low (70>pLDDT>50); and orange stands for very low (pLDDT<50).

Discussion

AMP probability describes how similar the sequence is to known AMPs according to the model, while potency / effectiveness refers to how strongly a peptide kills bacteria in experiments (exp. MIC values). The higher predicted AMP probability suggests a greater likelihood of antimicrobial activity, but the true potency remains unknown without experimental MIC measurements. Because short peptides can be flexible in aqueous solution, the AlphaFold structure should be viewed as a possible model of how the peptide might look when interacting with a membrane, rather than a confirmed conformation in solution.

Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) estimates how well a predicted structure agrees with an experimental structure based on backbone carbon coordinates26. It provides a per-atom confidence score from 0–100, where higher values indicate greater confidence: scores above 90 are highly reliable, while scores below 50 suggest likely inaccuracies (AlphaFold Server, 2025, https://alphafoldserver.com/guides#section-3:-interpreting-results-from-alphafold-server). Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) measures AlphaFold 3’s confidence in the relative positions of two items within the predicted structure27. Higher PAE values indicate lower confidence in the predicted spatial relationship between residues.

AlphaFold3 predicts the initial peptide (Figure 2) to adopt a stable ![]() -helical conformation with high pLDDT scores (>90; dark blue) and low predicted aligned error (mostly dark green), indicating a well-defined structure with modest terminal flexibility typical of

-helical conformation with high pLDDT scores (>90; dark blue) and low predicted aligned error (mostly dark green), indicating a well-defined structure with modest terminal flexibility typical of ![]() -helical antimicrobial peptides. The final optimized peptide (Figure 3) shows a similar

-helical antimicrobial peptides. The final optimized peptide (Figure 3) shows a similar ![]() -helical fold with high pLDDT (mostly dark blue) and predominantly dark green PAE, reflecting very high local confidence and modest terminal flexibility. Comparison with the AlphaFold3-predicted LL-37 structure (Figure 4) reveals high pLDDT across the

-helical fold with high pLDDT (mostly dark blue) and predominantly dark green PAE, reflecting very high local confidence and modest terminal flexibility. Comparison with the AlphaFold3-predicted LL-37 structure (Figure 4) reveals high pLDDT across the ![]() -helical core (dark blue) with slightly reduced confidence at both termini (light blue), and predominantly low PAE with modest terminal flexibility (mostly dark green, with lighter green regions in the lower and right parts).

-helical core (dark blue) with slightly reduced confidence at both termini (light blue), and predominantly low PAE with modest terminal flexibility (mostly dark green, with lighter green regions in the lower and right parts).

Our findings suggest that computational amino acid length shortening and substitutions can enhance predicted AMP scores and reduce predicted toxicity. Shorter AMPs often retain strong antibacterial activity while reducing hemolysis and improving selectivity, stability, and resistance profiles28. Mechanistically, their activity—driven by binding to negatively charged membranes and peptide aggregation—tends to plateau with increasing length, showing diminishing per-residue effectiveness in longer sequences29. Substituting polar uncharged residues and glycine—a structurally flexible, non-polar special case—with positively charged or hydrophobic amino acids increases the predicted likelihood that a peptide will disrupt bacterial membranes or cross into the cytoplasm to interfere with intracellular processes, while limiting toxicity to host cells30.

As an ESKAPE pathogen, K. pneumoniae poses a serious threat to hospitalized patients, especially those in intensive care units. Its multi-drug resistance contributes to high mortality and substantial healthcare costs. Developing safe and effective antimicrobial peptides represents a promising strategy to reduce deaths and protect vulnerable populations. A meta-analysis of 157 studies including 37,915 patients showed K. pneumoniae is associated with high, progressively increasing mortality: 17% at 7 days, 24% at 14 days, 29% at 30 days, and 34% at 90 days, with significantly higher rates in ICU patients4. As a leading cause of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections, K. pneumoniae contributes to major healthcare expenditures, with direct hospital costs per CRE case ranging from ![]() 66,000 and total annual U.S. hospital costs estimated between

66,000 and total annual U.S. hospital costs estimated between ![]() 1.4 billion, alongside significant societal costs and loss of quality-adjusted life years31. Given the rapid rise in drug resistance, there is an urgent need to invest in the development of novel antimicrobials and alternative therapeutic strategies to effectively manage and contain K. pneumoniae infections.

1.4 billion, alongside significant societal costs and loss of quality-adjusted life years31. Given the rapid rise in drug resistance, there is an urgent need to invest in the development of novel antimicrobials and alternative therapeutic strategies to effectively manage and contain K. pneumoniae infections.

This work contributes to the broader effort to combat the growing threat of antibiotic resistance by applying a systematic and exhaustive computational approach to optimizing antimicrobial peptides. We computationally shortened the sequence and exhaustively tested 243 substitutions replacing polar uncharged, negatively charged residues, and glycine with positively charged amino acids (arginine, histidine, lysine), followed by targeted single-residue hydrophobic substitutions to reduce predicted toxicity. We first discarded variants with high predicted toxicity. Among the remaining sequences, we prioritized those with high predicted AMP probability, zero predicted toxicity, and suitable net charge and hydrophobic moment, and from these we selected one peptide as the final design.

This strategy computationally identified a novel peptide with greatly enhanced antimicrobial potential and reduced toxicity, achieving a predicted AMP probability of 1.0 and predicted toxicity of 0—improving from the original peptide’s predicted 0.531 and 0.5 scores, respectively. The predicted hydrophobic moment —a measure of the dipole moment created by the separation of charged and uncharged residues—decreased from 0.268 to 0.201, indicating membrane-inserting potential remaining within a relatively low to moderate range and the reduction suggesting a trade-off in peptide efficacy.

To place the novel design in a broader AMP context, the designed peptide was compared with LL-37, the only human cathelicidin. LL-37 is a 37-residue antimicrobial peptide produced by immune and epithelial cells that exerts broad antimicrobial activity, modulates immune responses, promotes tissue repair, and shows therapeutic potential in infection models32. The final optimized peptide showed a higher predicted AMP probability (1.0 vs. 0.749), equally low predicted toxicity (0), but a lower hydrophobic moment (0.201 vs. 0.521). The optimized peptide also had a higher predicted net charge (+8.5 vs. +6.0), suggesting stronger electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes. Both peptides had an ![]() -helical structure.

-helical structure.

The reduced hydrophobic moment may help decrease disruptive interactions with mammalian membranes, potentially lowering toxicity, but it could also weaken membrane-disrupting activity against bacteria. Future work could explore different hydrophobic moments to better balance predicted toxicity and antimicrobial effectiveness. The computationally generated helix wheels of the initial and final peptides exhibit some predicted amphipathic character that may support membrane activity, but their relatively weak predicted hydrophobic moment compared with LL-37 may limit membrane selectivity and potency. In this context, selectivity means being more harmful to bacteria than to human cells. Experimentally, this is often quantified using a selectivity index, such as the ratio between a toxicity value (e.g., hemolysis or cell viability) and MIC. In this project, we did not measure this index, so selectivity is only predicted, not experimentally confirmed. Repositioning residues to enhance the hydrophobic–hydrophilic separation could improve amphipathicity promoting binding to the bilayer. These simulations were made possible by leveraging computational tools, enabling efficient and cost-effective design of novel antimicrobial peptides.

This study demonstrates that AI and computational approaches can effectively help design novel AMPs targeting K. pneumoniae by optimizing amino acid length and substitutions to enhance predicted antimicrobial activity while reducing predicted toxicity. Such computational sequence-optimization strategies are broadly applicable for developing potent AMPs against diverse bacterial pathogens beyond K. pneumoniae. AMP-based drug development is a long and costly process, typically taking 13–14 years and costing tens of millions of euros per candidate, with delays and attrition potentially adding €50–100 million to early-stage expenses33. AI and computational methods hold great promises to substantially reduce both time and costs during the early discovery and lead optimization stages, offering a promising, cost-effective, and time-efficient alternative to traditional antibiotic development pathways.

This study, however, has several limitations:

- First, while CAMPR3/4 and ToxinPred are powerful tools, they are machine-learning models that use patterns in existing data to provide probabilistic predictions, not guarantees. Scores such as “AMP probability=1.0” or “toxicity=0” should be interpreted as “very likely” or “very unlikely” according to the model. The true behavior of the peptide must ultimately be confirmed by experiments.

- Second, this study did not specifically predict red blood cell hemolysis, which is a key concern for AMPs intended for systemic use. Future work should include in vitro hemolysis assays to access whether the peptide damages human red blood cells.

- Third, highly cationic peptides often increase hemolysis, reduced hydrophobic moment may reduce activity, strain-to-strain MIC variability.

- Fourth, while this study shows that computationally targeted single-site substitutions can improve predicted antimicrobial activity and reduce predicted toxicity, it is limited by focusing solely on shortening the peptide from 25 to 20 residues with an arbitrary cutoff, without exploring other lengths or sequence arrangements. Potentially valuable strategies such as multi-site substitutions and structural modifications to improve physicochemical propertiesand enhance the hydrophobic–hydrophilic separation were also not examined.

As all results are based solely on computational predictions, future research should build upon these findings by investigating a wider range of sequence alterations and performing wet lab experimental validation to confirm and further optimize the peptide design.

Molecular dynamics simulations incorporating an atomistic bilayer and surrounding solvent offer detailed insight into peptide–bilayer interactions34. The energetics of AMP addition to a transmembrane pore, quantified through molecular dynamics simulations, are essential for evaluating pore formation and growth, providing critical insight into the pore-forming ability of peptides in cell membranes35. However, conducting membrane simulations and energetics studies is computationally intensive and represents an important direction for future research.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Dr. Christopher Lockhart, Dr. Elena Rivas, and Dr. Danielle Ross for their invaluable guidance throughout this research.

- H. G. Braun, S. R. Perera, Y. D. N. Tremblay, J.-L. Thomassin, Antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: an overview of common mechanisms and a current Canadian perspective. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 70, 507–528, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjm-2024-0032. [↩]

- M. K. Paczosa, J. Mecsas, Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 80, 629–661, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00078-15. [↩]

- GBD 2021 Lower Respiratory Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00176-2. [↩]

- D. Li, X. Huang, H. Rao, H. Yu, S. Long, Y. Li, J. Zhang, Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 13, 1157010, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1157010. [↩] [↩]

- X. C. Lin, C. L. Li, S. Y. Zhang, X. F. Yang, M. Jiang, The global and regional prevalence of hospital-acquired carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 11, ofad649, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad649. [↩]

- F. Svara, D. J. Rankin, The evolution of plasmid-carried antibiotic resistance. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11, 130, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-130. [↩]

- T. Islam, N. T. Tamanna, M. S. Sagor, R. M. Zaki, M. F. Rabbee, M. Lackner, Antimicrobial peptides: a promising solution to the rising threat of antibiotic resistance. Pharmaceutics. 16, 1542, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16121542. [↩]

- P. Gagat, M. Ostrówka, A. Duda-Madej, P. Mackiewicz, Enhancing antimicrobial peptide activity through modifications of charge, hydrophobicity, and structure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 25, 10821, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms251910821. [↩] [↩]

- L. A. C. Branco, P. F. N. Souza, N. A. S. Neto, T. K. B. Aguiar, A. F. B. Silva, R. F. Carneiro, C. S. Nagano, F. P. Mesquita, L. B. Lima, C. D. T. Freitas, New insights into the mechanism of antibacterial action of synthetic peptide Mo-CBP3-PepI against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antibiotics. 11, 1753, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11121753. [↩]

- H. Zhou, X. Du, Y. Wang, J. Kong, X. Zhang, W. Wang, Y. Sun, C. Zhou, T. Zhou, J. Ye, Antimicrobial peptide A20L: in vitro and in vivo antibacterial and antibiofilm activity against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiology Spectrum. 12, e03979-23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.03979-23. [↩]

- J. Z. Lau, S. H. Kuo, Y. Belo, E. Malach, B. Maron, H. E. Caraway, M. W. Oh, Y. Zhang, N. Ismail, G. W. Lau, Z. Hayouka, Antibacterial efficacy of an ultra-short palmitoylated random peptide mixture in mouse models of infection by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 67, e00574-23, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00574-23. [↩]

- M. Nedyalkova, A. S. Paluch, D. Potes Vecini, M. Lattuada, Progress and future of the computational design of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): Bio-inspired functional molecules. Digital Discovery. 3, 9–22, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1039/D3DD00186E. [↩]

- H. Meng, AI-Driven Discovery and Design of Antimicrobial Peptides: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, advance online publication, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-025-10856-0. [↩]

- S. Sur, H. Nimesh, Challenges and limitations of computer-aided drug design. Advances in Pharmacology (San Diego, Calif.). 103, 415–428, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apha.2025.02.002. [↩]

- D. P. Mihai, G. M. Nitulescu, Computer-Aided Drug Design and Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals. 18(3), 436, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030436. [↩]

- D. Bae, M. Kim, J. Seo, H. Nam, AI-guided discovery and optimization of antimicrobial peptides through species-aware language model. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 26(4), bbaf343, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaf343. [↩]

- A. Mesa, A. Orrego, J. W. Branch-Bedoya, et al., Antimicrobial Peptides Design Using Deep Learning and Rational Modifications: Activity in Bacteria, Candida albicans, and Cancer Cells. Curr Microbiol. 82, 379, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-025-04346-3. [↩]

- J. Y. Kwon, M. K. Kim, L. Mereuta, C. H. Seo, T. Luchian, Y. Park, Mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptide P5 truncations against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. AMB Express. 9(1), 122, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0843-0. [↩]

- L. M. Yin, M. A. Edwards, J. Li, C. M. Yip, C. M. Deber, Roles of hydrophobicity and charge distribution of cationic antimicrobial peptides in peptide-membrane interactions. J Biol Chem. 287(10), 7738–7745, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.303602. [↩]

- J. Tan, J. Huang, Y. Huang, Y. Chen, Effects of Single Amino Acid Substitution on the Biophysical Properties and Biological Activities of an Amphipathic α-Helical Antibacterial Peptide Against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules. 19(8), 10803-10817, 2014, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190810803. [↩]

- A. Al-Khdhairawi, D. Sanuri, R. Akbar, S. D. Lam, S. Sugumar, N. Ibrahim, S. Chieng, F. Sairi, Machine learning and molecular simulation ascertain antimicrobial peptide against Klebsiella pneumoniae from public database. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 102, 107800, 2023. [↩]

- T. Li, X. Ren, X. Luo, et al., A Foundation Model Identifies Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Peptides against Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infection. Nat Commun. 15, 7538, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51933-2. [↩]

- P. Das, T. Sercu, K. Wadhawan, I. Padhi, S. Gehrmann, F. Cipcigan, V. Chenthamarakshan, H. Strobelt, C. dos Santos, P.-Y. Chen, Y. Y. Yang, J. Tan, J. Hedrick, J. Crain, A. Mojsilovic, Accelerating antimicrobial discovery with controllable deep generative models and molecular dynamics. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00689-x. [↩]

- M. Schiffer, A. B. Edmundson, Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential. Biophysical Journal. 7, 121–135, 1967, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86579-2. [↩]

- J. K. Rasheed, G. J. Anderson, H. Yigit, A. M. Queenan, A. Doménech-Sánchez, J. M. Swenson, J. W. Biddle, M. J. Ferraro, G. A. Jacoby, F. C. Tenover, Characterization of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase reference strain, Klebsiella pneumoniae K6 (ATCC 700603), which produces the novel enzyme SHV-18. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 44, 2382–2388 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.44.9.2382-2388.2000. [↩]

- E. F. McDonald, T. Jones, L. Plate, J. Meiler, A. Gulsevin, Benchmarking AlphaFold2 on peptide structure prediction. Structure. 31, 111–119.e2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2022.11.012. [↩]

- P. G. Magana Gomez, O. Kovalevskiy, AlphaFold: a practical guide. Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom: EMBL-EBI, 2024, https://doi.org/10.6019/TOL.AlphaFold-w.2024.00001.1. [↩]

- A. Barreto-Santamaría, Z. J. Rivera, J. E. García, H. Curtidor, M. E. Patarroyo, M. A. Patarroyo, G. Arévalo-Pinzón, Shorter antibacterial peptide having high selectivity for E. coli membranes and low potential for inducing resistance. Microorganisms. 8, 867, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060867. [↩]

- S. Clark, T. A. Jowitt, L. K. Harris, C. G. Knight, C. B. Dobson, The lexicon of antimicrobial peptides: a complete set of arginine and tryptophan sequences. Communications Biology. 4, 605, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02137-7. [↩]

- R. M. Fleeman, L. A. Macias, J. S. Brodbelt, B. W. Davies, Defining principles that influence antimicrobial peptide activity against capsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117, 27620–27626, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007036117. [↩]

- (S. M. Bartsch, J. A. McKinnell, L. E. Mueller, L. G. Miller, S. K. Gohil, S. S. Huang, B. Y. Lee, Potential economic burden of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the United States. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 23, 48.e9–48.e16, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.09.003. [↩]

- O. E. Voronko, V. A. Khotina, D. A. Kashirskikh, A. A. Lee, V. A. Gasanov, Antimicrobial peptides of the cathelicidin family: Focus on LL-37 and its modifications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 26, 8103, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26168103 [↩]

- L. Cresti, G. Cappello, A. Pini, Antimicrobial peptides towards clinical application—a long history to be concluded. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 25, 4870, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25094870. [↩]

- P. La Rocca, P. C. Biggin, D. P. Tieleman, M. S. P. Sansom, Simulation studies of the interaction of antimicrobial peptides and lipid bilayers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1462, 185–200, 1999,https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00206-0. [↩]

- Y. Lyu, N. Xiang, X. Zhu, G. Narsimhan, Potential of mean force for insertion of antimicrobial peptide melittin into a pore in mixed DOPC/DOPG lipid bilayer by molecular dynamics simulation. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 146, 155101, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4979613 . [↩]