Abstract

This study investigates the emotional responses of Asian Americans before, during, and after the 2024 presidential election, addressing a critical gap in understanding how this rapidly growing demographic experiences major political events. Using a longitudinal design, 62 self-identified Asian American adults were recruited via purposive sampling to complete surveys at three time points: one week before, on, and one week after the 2024 presidential election. Emotional responses were measured using validated scales: the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Short Form (PANAS-SF) for positive and negative affect, and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) for psychological stress. Although the relatively small sample size limits generalizability to the broader Asian American population, this study offers important preliminary insights. Results showed a significant increase in positive affect on election day, while psychological stress remained stable across all three periods. Based on previous research indicating elevated election-related stress among minority voters, we expected to observe heightened stress and negative affect; however, no significant partisan differences in emotional response patterns were found. These findings suggest that emotional reactions to elections among Asian Americans may be less polarized than prior studies or public narratives imply. This study underscores the importance of culturally sensitive research in political psychology and has implications for voter engagement and mental health support within the Asian American community.

Tracking Asian Americans’ Emotional Responses Before, During, and After the 2024 Presidential Election

The 2024 presidential election represents a critical moment in American democracy, occurring against a backdrop of increasing political polarization and rising anxiety levels among the general population1. For Asian Americans, who constitute one of the fastest-growing racial groups in the United States2, this election holds particular significance. Despite their growing demographic presence and increasing political engagement3, there remains limited research examining how Asian Americans emotionally experience and respond to major political events, particularly presidential elections.

Understanding the emotional responses of Asian Americans to electoral processes is crucial for several reasons. First, it provides insights into how this diverse community engages with and is affected by significant political events4. Second, it helps identify potential barriers to political participation that may be unique to Asian American voters5. Third, it may contribute to the broader understanding of how racial identity, cultural background, and political affiliation intersect to shape emotional experiences during elections6.

Asian American cultural norms, which often emphasize emotional restraint and harmony due to collectivist values7, may influence how individuals experience and express emotions in political contexts. This emotional regulation may lead to unique patterns of political emotional responses compared to more individualistic cultural groups. Additionally, Asian Americans’ experiences with racialization and stereotypes (such as the model minority myth) can affect their social identity and emotional engagement with political events.

Key concepts in this study are operationalized as follows: positive affect and negative affect refer to the experience of pleasurable and distressing emotions, respectively, measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Short Form (PANAS-SF); psychological stress refers to perceived stress levels assessed by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); social identity reflects individuals’ self-categorization within racial, ethnic, and political groups that influence their emotions and political behavior; and emotional resources are affective states that can motivate political participation, as conceptualized by the Affect-Integration-Resource (AIR) model.

This study draws upon two complementary theoretical frameworks to understand how Asian Americans emotionally experience and respond to political events: the Affect-Integration-Resource (AIR) model and the Social Identity Theory of Political Behavior. The AIR model (Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. University of Chicago Press.) posits that emotions serve dual roles as both outcomes of political events and as resources that individuals can mobilize for political engagement. For example, anxiety may prompt information seeking, whereas enthusiasm may encourage political participation based on existing preferences8. Thus, emotions are dynamic resources influencing cognitive and behavioral political responses.

Complementing the AIR model, the Social Identity Theory of Political Behavior9 explains how individuals’ social identities—including racial, ethnic, and political identities—influence their political attitudes and emotional responses. Group membership shapes how political events are appraised emotionally, with individuals interpreting political stimuli through the lens of their identities. Research shows that ethnic identity can moderate the link between political events and emotional reactions, especially among minority groups10.

Integrating these frameworks provides a comprehensive lens to examine Asian Americans’ emotional experiences. The AIR model helps us understand how emotions function as resources for political engagement, while Social Identity Theory clarifies how these emotional processes are shaped by group identities and social contexts. Together, they suggest that Asian Americans’ emotional responses to elections are influenced by immediate affective reactions and by their sense of belonging to social groups. This integration further implies a bidirectional relationship: social identity affects which emotions are available and mobilized as resources, while emotional experiences can reinforce or reshape social identity in the political context.

The need for this research is particularly timely given recent findings showing increased psychological distress during election periods11 and the documented relationship between political events and mental health outcomes12. This study aims to address these knowledge gaps by examining Asian Americans’ emotional responses throughout the 2024 presidential election cycle. By tracking changes in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress before, during, and after the election, the study aims to understand how this significant political event impacts the psychological well-being of Asian American voters.

Political Events and Mental Health: A Growing Public Health Concern

The intersection of political events and mental health has emerged as a significant public health concern in recent years. The American Psychiatric Association (2023) reports a dramatic increase in anxiety levels among adults, rising from 32% in 2022 to 43% in 2024, coinciding with heightened political polarization. This trend is particularly noteworthy as it represents an isolated spike and a sustained increase in psychological distress tied to political events13. The relationship between political events and mental health outcomes extends beyond general anxiety to more specific manifestations of psychological distress. Recent research by Baum and colleagues11 reveals that depression can significantly alter political attitudes and behaviors, particularly when interacting with other psychological factors such as conspiracy beliefs or strong political engagement. Their findings suggest that these psychological states can create feedback loops where political events influence mental health, which in turn shapes political attitudes and behaviors.

This complex relationship between political events and psychological well-being is further complicated by exposure to political violence and instability, which correlates with increased psychological distress and various manifestations of anxiety and depression14. The American Psychological Association (2024) also emphasizes that political stress has become a persistent feature of contemporary life, with potential long-term implications for individual and collective mental health outcomes.

The Evolution of Asian American Political Engagement

The political landscape for Asian Americans has undergone significant transformation over the past several decades, marked by shifting party alignments and evolving patterns of civic engagement. Wong and colleagues15 document a notable transition from predominantly Republican support in the 1990s to increased Democratic alignment in recent years, exemplified by the shift from 55% support for George H. W. Bush in 1992 to 62% for Barack Obama in 200816. This political realignment reflects broader changes in Asian American communities’ relationship with American political institutions and processes.

However, this evolution in political preferences has not necessarily translated into proportional political participation. For example, there have been persistent disparities in civic engagement, with Asian Americans showing significantly lower rates of political volunteerism (16%) compared to other demographics17. This participation gap also persists across age groups, suggesting the influence of deeper structural and cultural barriers rather than generational differences. The challenges extend beyond voting to include broader forms of political participation, with language barriers, limited political representation, and unfamiliarity with electoral processes creating significant obstacles to full civic engagement4.

Cultural Dimensions of Political Response

The intersection of cultural factors and political engagement among Asian Americans presents a unique framework for understanding emotional responses to political events. Research documents how cultural norms fundamentally shape emotional expression and regulation, with collectivist cultures often emphasizing emotional restraint in contrast to the more expressive norms of individualistic cultures7. This cultural context is crucial for understanding how Asian Americans process and respond to political events, as it influences both individual emotional experiences and collective political behavior.

Recent research by Advancing Justice – AAJC18 reveals a complex picture of Asian American political engagement, where strong confidence in electoral processes coexists with significant barriers to participation, particularly among immigrant communities. These findings suggest that cultural factors interact with structural barriers to create unique challenges for Asian American political participation. The relationship between cultural background and political engagement is further complicated by the diversity within Asian American communities, with varying levels of acculturation and different cultural traditions influencing political behavior and emotional responses15.

The literature also reveals several critical gaps in the knowledge about Asian Americans’ emotional experiences during elections. While existing research has documented broad patterns of political participation and voting behavior, less attention has been paid to the psychological dimensions of political engagement, particularly during high-stakes events like presidential elections. The intersection of political stress, cultural factors, and civic engagement presents a complex framework for understanding how Asian Americans experience and respond to political events.

The Current Study

Building on these identified gaps in the literature, this study examines the dynamic relationship between political events and emotional responses among Asian American voters. The present study considers both individual differences and broader cultural contexts, tracking changes in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress throughout the election cycle. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how this significant demographic navigates the emotional landscape of American democracy.

Given Asian Americans’ unique position in the U.S. political landscape, a key focus is understanding how party affiliation may moderate emotional responses to the election. In addition, the study design specifically addresses this by including both Democratic and Republican Asian American voters, enabling the examination of potential differences in emotional experiences based on political alignment. Additionally, the study considers how demographic factors, including gender and sexual orientation, shape these responses.

The study addresses three primary research questions:

- How do positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress levels change across the election period among Asian American voters?

- How do Democratic and Republican Asian American voters differ in their emotional responses to the election?

- To what extent do demographic factors influence these emotional responses?

Based on previous research and theoretical framework, it was hypothesized:

- There will be significant changes in emotional responses (positive affect, negative affect) and psychological stress across the election period, with heightened emotional reactivity and stress during the election day compared to pre- and post-election periods.

- There will be significant differences in emotional responses between Democratic and Republican Asian American voters, with members of each party showing distinct patterns of affect and stress in response to the election.

- It is anticipated that demographic factors, particularly gender and age, significantly influence emotional responses to the election, with women potentially showing higher levels of negative affect and stress compared to men.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited through a combination of convenience and snowball sampling methods. Participants were also encouraged to share the study with other eligible Asian American adults in their networks. All participants provided informed consent and completed online surveys administered through Google Form.

Participants were 62 self-identified Asian or Asian American adults recruited from various states in the United States. Data were collected at three time points surrounding the 2024 presidential election: one week before the election (October 29, 2024), on election day (November 5, 2024), and one week after the election (November 12, 2024). The majority of participants resided in New Jersey (n = 38, 61.3%), followed by New York (n = 8, 12.9%), California (n = 4, 6.5%), and other states including Arizona, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Michigan (n = 12, 19.3%). The majority of participants were female (n = 48, 77.4%), with 11 male participants (17.7%) and 3 participants identifying as other gender identities (4.8%).Participants provided demographic information including their gender (coded as 0 = male, 1 = female), sexual orientation (coded as 0 = straight, 1 = queer), political affiliation (coded as 1 = Democrat, 2 = Republican, 3 = Other, 4 = Prefer not to say), and age. For analyses examining partisan differences, only participants identifying as Democrats (n = 31) or Republicans (n = 14) were included.

The sample size is relatively small for representing the diverse Asian American population. However, this sample size was determined based on statistical requirements for detecting meaningful changes over time, practical recruitment challenges within Asian American communities, and the exploratory nature of this research as one of the first studies examining real-time emotional responses during elections.

Measures

Positive and Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Short Form (PANAS-SF; Watson, 1988) was used to assess participants’ emotional states. The measure consists of 20 items, with 10 items measuring positive affect (α = .85) and 10 items measuring negative affect (α = .81). Participants rated each emotion on a scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Mean scores were calculated separately for positive and negative affect subscales.

Psychological Stress

Psychological stress was measured using a 6-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .76). Items were rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. Mean scores were calculated across all items.

Demographic Information

Participants provided demographic information including their gender (coded as 0 = male, 1 = female), sexual orientation (coded as 0 = straight, 1 = queer), political affiliation (coded as 0 = Democrat, 1 = Republican), and age.

Data Analysis

Linear regression analyses were conducted to examine changes in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress across the three time points. Linear regression was chosen as the primary analytical approach for several methodological reasons: (1) The outcome variables are continuous and approximately normally distributed, making linear regression appropriate; (2) Linear regression allows for straightforward interpretation of effect sizes and confidence intervals, which are crucial for understanding practical significance; (3) The method accommodates both categorical predictors (time periods, party affiliation) and continuous covariates (age) within the same model; (4) Linear regression provides robust estimates even with modest sample sizes compared to more complex methods like multilevel modeling; (5) The transparency and interpretability of linear regression align with our goal of providing clear, replicable findings for this understudied population.

The pre-election period served as the reference group, with dummy variables created for the election day and post-election periods. Initial analyses examined the main effects of the election period on each outcome variable. Supplementary analyses incorporated demographic variables (gender, sexual orientation, political affiliation, and age) as covariates to test the robustness of the findings. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0 (R Core Team, 2024). Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all analyses. Given the exploratory nature of some analyses and to balance Type I and Type II error risks, we report both p-values and effect sizes with confidence intervals to facilitate interpretation of practical significance alongside statistical significance.

Results

Primary Analyses: Changes Across Election Periods

The primary analyses examined changes in psychological responses across election periods using linear regression models, with supplementary analyses incorporating demographic covariates to test the robustness of the sample. For comprehensive interpretation, we report both unstandardized (b) and standardized (β) coefficients, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and multiple measures of effect size.

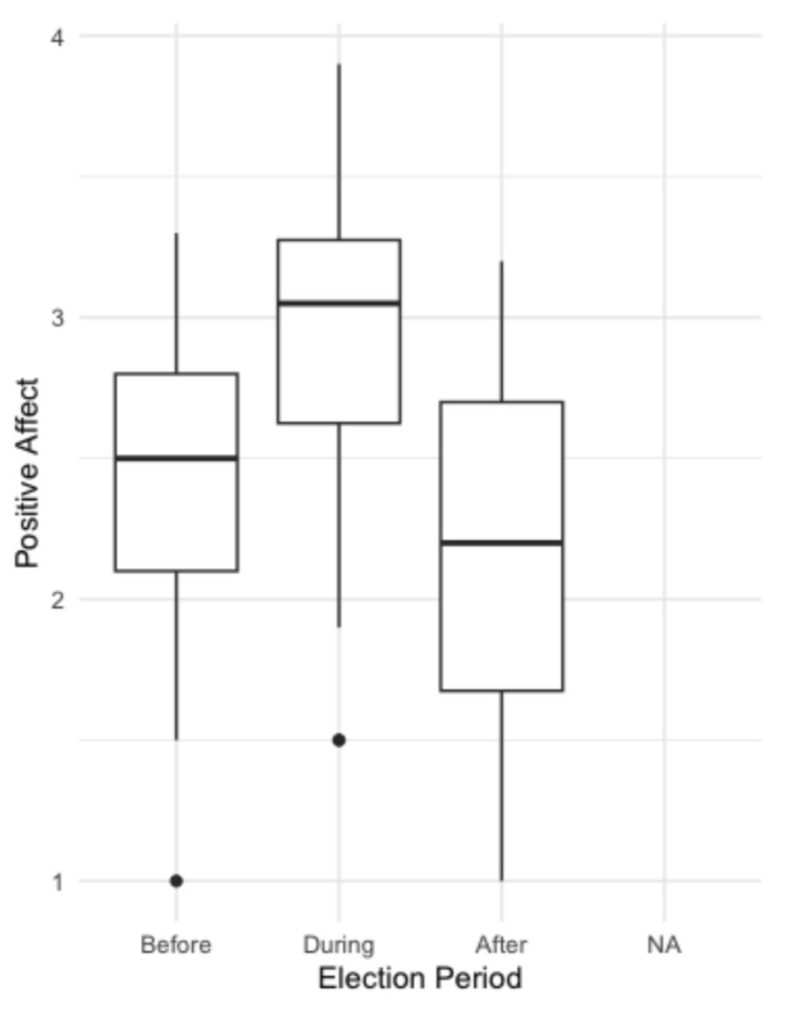

The initial regression model for positive affect yielded significant results (F(2, 58) = 4.76, p = .012), explaining 14.1% of the variance (R² = .141, adjusted R² = .111). During the election period, participants reported significantly higher levels of positive affect compared to the pre-election period (b = 0.41, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [0.05, 0.77], p = .026; β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.04, 0.54]), representing a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.60). As shown in Figure 1, although positive affect decreased in the post-election period compared to pre-election levels, this change was not statistically significant (b = -0.28, SE = 0.23, 95% CI [-0.74, 0.18], p = .236; β = -0.15, 95% CI [-0.40, 0.10]).

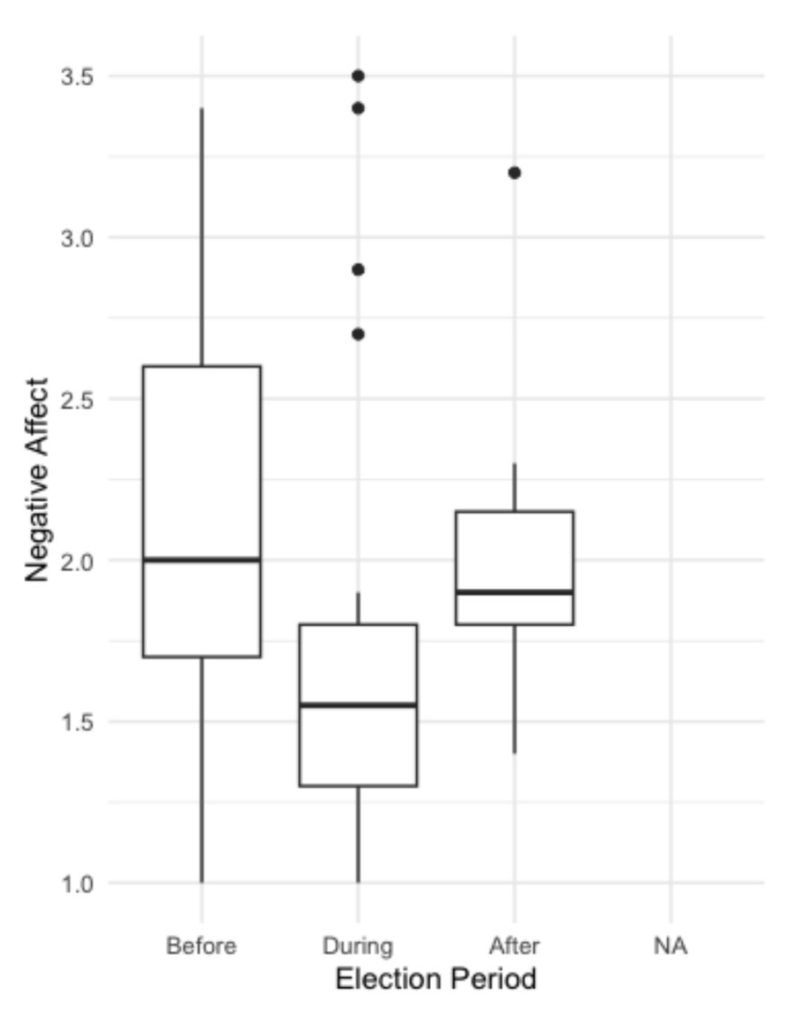

For negative affect (see Figure 2), while the overall model showed a small-to-medium effect size (R² = .075, Cohen’s f² = 0.081), it did not reach statistical significance (F(2, 58) = 2.35, p = .105). However, there was a significant decrease in negative affect during the election period compared to the pre-election period (b = -0.38, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [-0.74, -0.02], p = .035; β = -0.27, 95% CI [-0.52, -0.02]), demonstrating a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = -0.57). The post-election period showed only a small, non-significant reduction in negative affect (b = -0.14, SE = 0.23, 95% CI [-0.60, 0.32], p = .540; β = -0.08, 95% CI [-0.33, 0.17]).

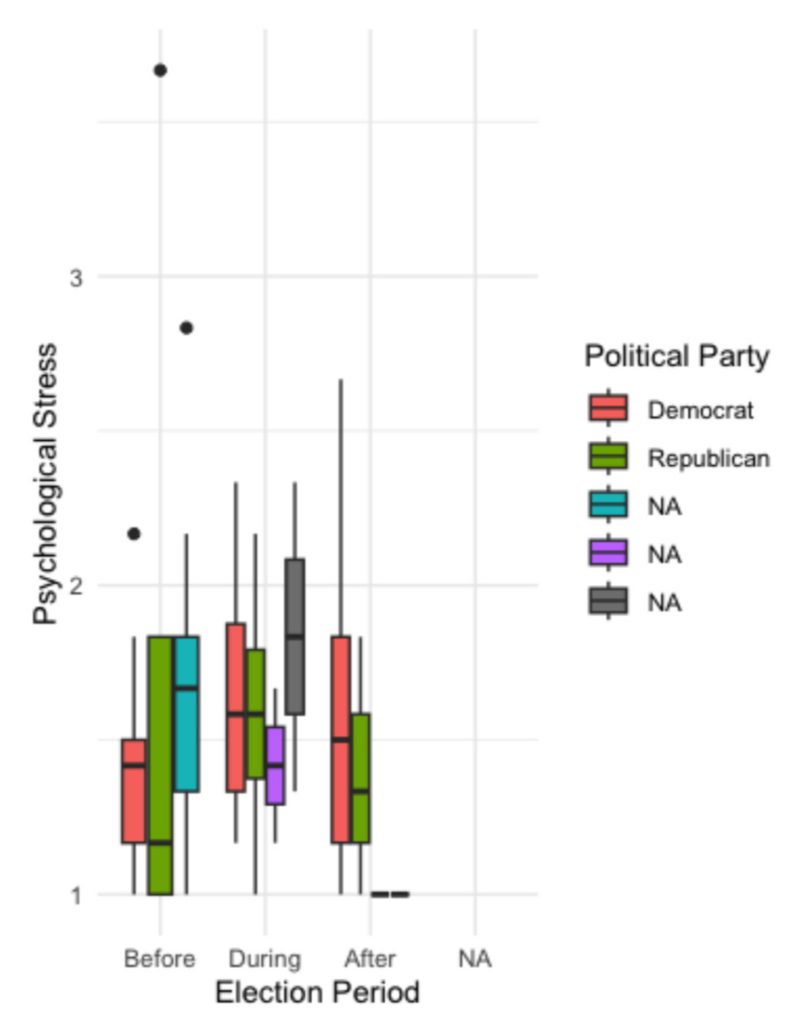

The model for psychological stress showed minimal effects and was not statistically significant (F(2, 58) = 0.37, p = .692, R² = .013). Neither the during-election period (b = 0.05, SE = 0.15, 95% CI [-0.25, 0.35], p = .716; β = 0.05) nor the post-election period (b = -0.12, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [-0.50, 0.26], p = .542; β = -0.08) showed detectable differences in stress levels compared to the pre-election period (see Figure 3).

A series of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to examine changes in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress across three time periods: before, during, and after the 2024 presidential election. Results revealed significant temporal changes in emotional responses, particularly for positive affect, while stress levels remained stable throughout the election period. For positive affect, the ANOVA revealed significant differences across periods (F(2, 58) = 4.76, p = .012). Follow-up Tukey HSD tests provided a more nuanced understanding of these changes. Positive effect showed a marginally significant increase from the pre-election period to election day (Mean difference = 0.41, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.84], p = .066). However, this elevation in positive affect was temporary, as evidenced by a significant decrease from election day to the post-election period (Mean difference = -0.69, 95% CI [-1.27, -0.11], p = .017). The comparison between pre-election and post-election periods showed no significant difference (Mean difference = -0.28, 95% CI [-0.84, 0.28], p = .459), suggesting that positive effects returned to baseline levels after the election.

Changes in negative affect followed a complementary pattern, though the effects were less pronounced. The overall ANOVA showed a marginally significant effect of time (F(2, 58) = 2.35, p = .105). Tukey HSD comparisons revealed a trend toward decreased negative affect during the election compared to the pre-election period (Mean difference = -0.38, 95% CI [-0.81, 0.04], p = .086). This reduction in negative affect did not persist into the post-election period, as indicated by non-significant differences between post-election and both pre-election (Mean difference = -0.14, 95% CI [-0.69, 0.41], p = .811) and election day (Mean difference = 0.24, 95% CI [-0.33, 0.81], p = .573) measurements.

In contrast to the emotional measures, psychological stress showed minimal variation across all periods. The ANOVA revealed no significant differences (F(2, 58) = 0.37, p = .692), and all pairwise comparisons were non-significant (all ps > .66). While stress levels showed little variation, power limitations prevent definitive conclusions about the absence of small effects

Supplementary Analyses: Models with Demographic Controls

Demographic covariates were included in the supplementary analyses, and the pattern of results remained similar, though the statistical significance of the election period effects was reduced. The full model for positive affect (F(6, 51) = 1.84, p = .110, R² = .178) showed that the election period effect was diminished (b = 0.26, 95% CI [-0.16, 0.68], p = .215; β = 0.19) after controlling for demographics. Gender emerged as a notable, though non-significant, predictor (b = -0.38, 95% CI [-0.86, 0.10], p = .119; β = -0.21).

Similarly, in the covariate model for negative affect (F(6, 51) = 1.16, p = .342, R² = .120), the previously significant election period effect was reduced (b = -0.19, 95% CI [-0.61, 0.23], p = .357; β = -0.14). Gender showed a marginally significant effect (b = 0.41, 95% CI [-0.07, 0.89], p = .092; β = 0.23), suggesting that women tended to report higher levels of negative affect compared to men. The psychological stress model with covariates remained non-significant (F(6, 51) = 0.53, p = .781, R² = .059), with no meaningful effects for either election periods or demographic variables.

These findings suggest that the election period had the strongest impact on emotional responses, particularly during the election itself, with moderate effect sizes for both positive and negative affect in the primary analyses. The attenuation of these effects in the covariate models, coupled with wider confidence intervals, suggests that the loss of statistical significance may be more attributable to reduced statistical power than to genuine confounding effects. Psychological stress remained remarkably stable across all periods, showing minimal response to the election cycle.

Political Party Comparisons

Independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine differences between Democrats (n = 31) and Republicans (n = 14) in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress. Surprisingly, results revealed no significant differences between the political parties on any of the outcome measures. For positive affect, Democrats (M = 2.53, SD = 0.46) and Republicans (M = 2.56, SD = 0.49) showed nearly identical levels, t(21.57) = -0.17, p = .865, 95% CI [-0.46, 0.39]. The narrow confidence interval and similar means suggest that both parties experienced comparable levels of positive emotions throughout the election period. Similarly, negative affect levels were not significantly different between Democrats (M = 2.02, SD = 0.41) and Republicans (M = 1.92, SD = 0.44), t(17.18) = 0.40, p = .691, 95% CI [-0.41, 0.60]. While Democrats showed slightly higher negative affect, this difference was minimal and not statistically significant. Psychological stress also showed remarkable similarity between Democrats (M = 1.53, SD = 0.38) and Republicans (M = 1.60, SD = 0.41), t(16.42) = -0.34, p = .735, 95% CI [-0.49, 0.36]. The nearly identical stress levels suggest that members of both parties experienced similar levels of psychological stress during the election period. These findings suggest that among Asian American voters, political party affiliation did not significantly influence emotional responses or stress levels during the 2024 presidential election. This pattern of results is particularly noteworthy given the often-observed partisan differences in emotional responses to political events in the general population.

Party × Time Interactions in Emotional Responses

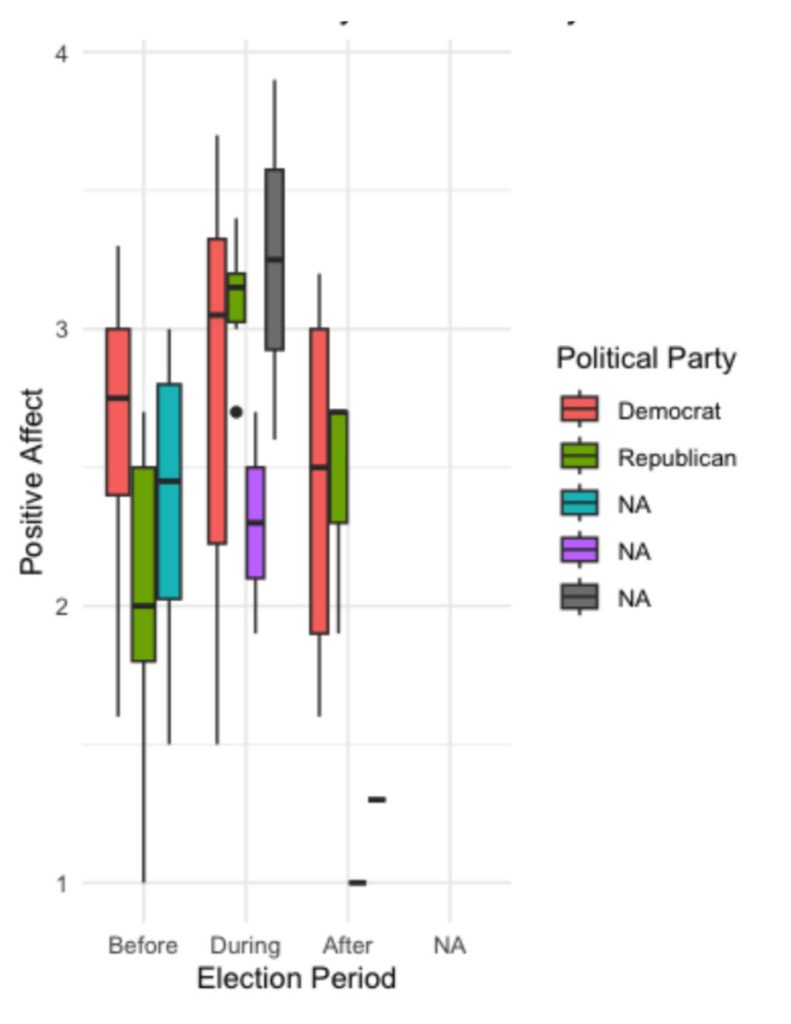

To examine how political party affiliation influenced emotional and stress responses across the election period, regression analyses were conducted to test both main effects and interactions between party affiliation and time period. These analyses revealed notable differences in how Democrats and Republicans emotionally experienced the election, particularly in their positive affect responses. The analysis of positive affect yielded significant results (F(5, 53) = 2.83, p = .024, R² = .211), explaining 13.6% of the adjusted variance. Most notably, significant interaction was found between party affiliation and the election period (b = 0.94, SE = 0.43, p = .032), indicating that Republicans showed a more pronounced increase in positive affect during the election compared to Democrats. This party difference showed a tendency to persist into the post-election period, as suggested by a marginally significant interaction (b = 0.92, SE = 0.52, p = .084). Additionally, there was a marginally significant main effect of party affiliation (b = -0.55, SE = 0.30, p = .072), with Democrats showing somewhat higher baseline levels of positive affect before the election (Figure 4).

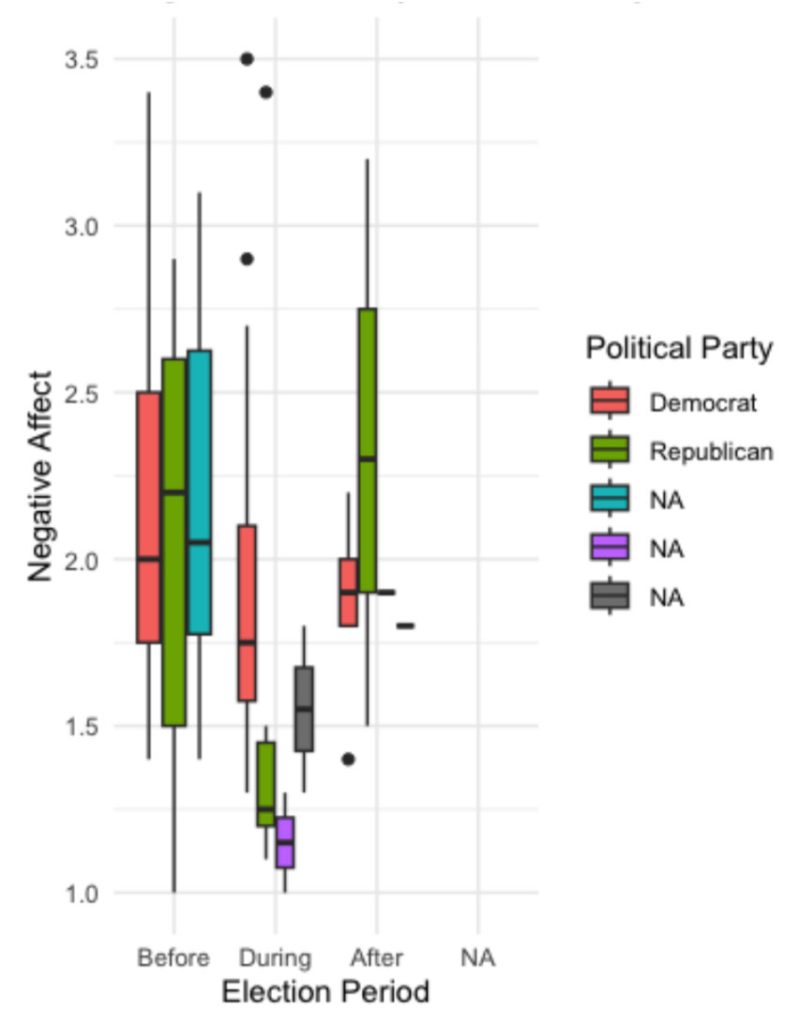

In contrast, the analysis of negative effects revealed no significant party-related patterns (F(5, 53) = 1.13, p = .355, R² = .097). Neither the interaction between party and the election period (b = -0.11, SE = 0.44, p = .803) nor between party and the post-election period (b = 0.60, SE = 0.54, p = .274) reached significance. The main effect of party affiliation was also non-significant (b = -0.12, SE = 0.31, p = .698), suggesting that changes in negative affect over the election period were relatively consistent across party lines (see Figure 5).

Psychological stress showed remarkable stability across both party affiliations and time periods (see Figure 6). The model revealed no significant effects (F(5, 53) = 0.25, p = .937, R² = .023), with all interaction terms and main effects failing to reach significance. Neither the interaction between party and the election period (b = -0.22, SE = 0.37, p = .557) nor between party and the post-election period (b = -0.28, SE = 0.45, p = .536) was significant. The main effect of party affiliation was also non-significant (b = 0.22, SE = 0.26, p = .409), indicating that stress levels remained stable regardless of political affiliation or timing relative to the election.

These findings suggest that while Democrats and Republicans experienced the election differently, these differences were primarily manifested in positive emotional responses rather than negative emotions or stress levels. Republicans showed a more pronounced increase in positive affect during the election period, while both parties showed similar patterns in negative affect and maintained stable stress levels throughout the election cycle. This pattern of results suggests that political party affiliation among Asian Americans primarily influenced the experience of positive emotions during the election, while negative emotional responses and stress management remained relatively consistent across party lines.

Discussion

The present study investigated emotional responses among Asian American voters during the 2024 presidential election, examining changes in positive affect, negative affect, and psychological stress across three time points. Guided by the AIR model and Social Identity Theory, three primary analyses examined temporal changes in emotional responses, partisan differences, and demographic influences. The findings reveal both expected and unexpected patterns in how Asian Americans emotionally experience major political events.

The first hypothesis predicted significant changes in emotional responses across the election period, with heightened affect and stress during the election. This hypothesis was partially supported. As expected, the positive effect showed significant temporal variation, with a marked increase during election day (b = 0.41, p = .026) followed by a return to baseline levels post-election. However, contrary to the sample, the negative effect showed only modest changes, with a significant decrease during the election period (b = -0.38, p = .035) but no significant post-election effects. Most notably, and contrary to the sample, psychological stress showed minimal variation throughout the election period, with no significant changes detected (F(2, 58) = 0.37, p = .692). While this pattern differs from assumptions about election-related stress, power limitations prevent definitive conclusions about stress stability. However, this finding may suggest that Asian American voters process political events differently than previously documented in general population studies19, warranting further investigation with larger samples.

The second hypothesis predicted significant differences in emotional responses between Democratic and Republican Asian American voters. Surprisingly, this hypothesis was largely unsupported. The data revealed no significant differences between parties in overall levels of positive affect (t(21.57) = -0.17, p = .865), negative affect (t(17.18) = 0.40, p = .691), or psychological stress (t(16.42) = -0.34, p = .735). The only notable partisan difference emerged in the temporal pattern of positive affect, where Republicans showed a more pronounced increase during the election period (b = 0.94, SE = 0.43, p = .032). This interaction effect suggests that while overall emotional responses were similar across party lines, the timing and magnitude of positive emotional responses may vary by political affiliation. This could indicate that Republicans showed a greater sense of relief during the election period, while Democrats’ positive emotions were more stable. These differences may be influenced by factors such as political expectations, media exposure, or levels of engagement in the election process.

The study’s third hypothesis predicted the role of demographic factors in shaping emotional responses. The results provided limited support for this hypothesis. Gender emerged as a marginally significant predictor of negative affect (b = 0.41, p = .092), with women reporting higher levels than men. However, other demographic variables, including age and sexual orientation, showed no significant relationships with emotional responses. This suggests that while gender may have a small impact on emotional experiences, other demographic factors might not be strong predictors of emotional responses in this case.

Methodological Considerations for Covariate Models

The decrease of statistical significance when demographic covariates were included in the models warrants careful interpretation. The reduction in significance likely reflects decreased statistical power rather than genuine confounding effects, as evidenced by several key indicators: (1) effect sizes remained similar between primary and covariate models, with wider confidence intervals in the latter consistent with power reduction; (2) none of the demographic variables showed strong associations with the outcomes, making systematic confounding less probable; and (3) the pattern of reduced significance was consistent across all outcome measures, suggesting a power issue rather than variable-specific effects. This interpretation reflects known challenges of conducting covariate analyses with modest sample sizes, where the addition of multiple predictors can substantially reduce statistical power20. While the demographic variables were selected based on theoretical considerations from existing literature on political emotions21, future studies with larger samples would be better to examine these potential moderating effects with adequate statistical power.

Practical Implications for Community and Clinical Practice

These findings have several important implications for practitioners working with Asian American communities. The marginally significant gender effects on negative affect (b = 0.41, p = .092), while not reaching conventional statistical significance, suggest meaningful patterns with practical relevance. Mental health practitioners should be aware that Asian American women may experience heightened negative emotions during political periods, even when stress levels remain stable. This pattern indicates the need for targeted emotional support that addresses affective well-being without assuming clinical levels of distress.

For political organizations and community groups, these findings suggest that engagement strategies should be sensitive to potential gender differences in emotional responses while avoiding assumptions about uniform reactions within the Asian American community. The stability in stress levels across the election period indicates that Asian Americans may not require the intensive crisis-oriented mental health interventions often recommended during high-stakes political events, but rather culturally informed support that recognizes their unique coping resources.

The limited partisan differences observed have implications for voter outreach efforts. Rather than assuming strong emotional polarization between Democratic and Republican Asian American voters, organizations should focus on shared cultural experiences and community concerns that transcend party lines. This approach may be more effective than partisan appeals that assume emotional divisions similar to those found in general population studies.

Understanding Stress Stability: Cultural and Community Resources

The stability of psychological stress across the election period (F(2, 58) = 0.37, p = .692) represents one of the most intriguing findings and warrants deeper analysis of the cultural and community factors that may contribute to this emotional resilience.

Asian American cultural traditions often emphasize emotional regulation and collective coping strategies that may serve as protective factors during political stress22. The concept of emotional restraint documented in collectivist cultures23 may not merely suppress emotional expression but may actually facilitate more effective stress management during uncertain political periods. This cultural resource could explain why participants maintained stable stress levels despite the high-stakes nature of the 2024 election.

The limited partisan differences may reflect the strength of ethnic community bonds that transcend political affiliations. Research on Asian American social networks suggests that shared cultural experiences and collective identity often supersede political divisions24. Community organizations, cultural centers, and informal social networks may provide buffering effects that reduce political polarization and its associated emotional costs. Many Asian American families have navigated significant political upheavals in their countries of origin, potentially developing intergenerational coping strategies that promote emotional resilience during political uncertainty24. This historical perspective may contribute to a more measured emotional response to domestic political events, viewing them within a broader context of political change and adaptation.

Theoretical Contributions and Connections to Existing Literature

This study’s findings present several challenges to established theories in political psychology. The AIR model25 predicts that political events should mobilize emotional resources, particularly anxiety, to prompt information-seeking and political engagement. However, the stability of stress levels among Asian Americans suggests this model may not fully account for cultural variations in emotional mobilization. The finding that positive affect increased without corresponding stress elevation indicates that emotional resources may be activated differently in collectivist cultural contexts. While Social Identity Theory predicts that group membership should intensify emotional responses to relevant political events, the limited partisan differences suggest that ethnic identity may be more salient than political identity for Asian Americans. This extends Huddy’s26 framework by highlighting how ethnic identity can moderate the relationship between political identity and emotional responses.

The finding that Democratic and Republican Asian Americans showed similar overall emotional responses challenges assumptions about partisan polarization and suggests that shared ethnic experiences may create common emotional frameworks for processing political events. The specific pattern of increased positive affect on election day, followed by return to baseline, provides new insights into the temporal dynamics of political emotions in minority communities.

Implications and Future Directions

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the sample’s geographic concentration in New Jersey and surrounding states (61.3%) represents a significant limitation to generalizability24. Our sample does not proportionally represent the national distribution of Asian Americans, who are more heavily concentrated in states like California, Hawaii, and Washington. With only 4 participants from California, despite it having the largest Asian American population, the findings may not capture the full range of Asian American political-emotional experiences across different regional contexts and political climates. This geographic limitation is particularly important given that different states have varying political environments, campaign intensities, and Asian American community characteristics that could influence emotional responses to elections27. Moreover, this study lacks measurement of cultural variables despite emphasizing cultural factors in the theoretical framework. The absence of measures assessing acculturation, ethnic identity, individualism/collectivism, and other cultural dimensions creates a significant gap between the theoretical framework and empirical analysis. This limitation is particularly critical given the substantial diversity within Asian American communities, where individuals may vary greatly in generational status, cultural values, language use, and connection to heritage cultures. Without these cultural measures, the study cannot examine how these factors influence political-emotional responses, limiting the ability to understand the mechanisms underlying the observed patterns. The findings should therefore be interpreted as preliminary data that may not capture the full range of Asian American experiences. Future research must include comprehensive cultural assessments to meaningfully examine how cultural factors shape political-emotional responses within this diverse population.

Second, the sample on a single presidential election, while providing detailed temporal data, may not capture broader patterns of political-emotional response. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that political attitudes and emotional responses can vary significantly across different types of elections and political contexts25. Third, while the measurement of emotional responses was comprehensive, the complexity of Asian American identity and political engagement suggests that additional variables might be relevant. Research highlights the importance of considering cultural factors in emotional expression and regulation, which may have influenced the findings in ways not fully captured by the measures28. Fourth, the use of multiple statistical tests without correction increases the risk of Type I error, and marginally significant findings should be interpreted as preliminary trends requiring replication rather than definitive effects. It may be important to consider the responses during a single presidential election cycle, which may limit generalizability to other types of political events (midterm elections, local elections) or different political contexts.

Moreover, the non-significant stress findings should be interpreted cautiously given power limitations. While the minimal effect sizes and consistent means suggest relative stability, the study cannot rule out the possibility of small but meaningful stress changes that were undetectable with this sample size. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported measures, while standard in this type of research, may be subject to cultural biases in emotional expression and reporting29. This limitation is particularly relevant given research showing cultural variations in how emotions are experienced and expressed28. Finally, the sample of 62 participants may seem small for such a diverse population, this size was appropriate for the study’s focus on tracking emotional changes over time within the same group of participants. The sample provides important preliminary data for this understudied area and meets statistical requirements for the present analyses. Furthermore, the sample was predominantly female (77.4%), which limits the study’s ability to detect meaningful gender differences and reduces the generalizability of our gender-related findings. The marginally significant effect of gender on negative affect should be interpreted with caution given the small male subsample (n = 11) and resulting reduced statistical power. Future studies should ensure more balanced gender representation to adequately examine gender differences in Asian Americans’ emotional responses to political events.

The findings from this study suggest several promising avenues for future research in understanding Asian Americans’ emotional responses to political events. Given the geographic concentration of the sample in New Jersey and surrounding states, future studies should examine regional variations in emotional responses to elections among Asian American voters. Such research could help determine whether the patterns we observed—particularly the stability in stress levels and limited partisan differences—are consistent across different geographic and political contexts within the United States. Longitudinal research spanning multiple election cycles would provide valuable insights into the temporal stability of these emotional patterns. While the study captured responses during a single presidential election, examining emotional responses across different types of elections (midterm, local) and multiple electoral cycles could reveal whether the emotional stability we observed is consistent across various political contexts and periods. Such research could also help identify how changing political landscapes and evolving campaign strategies might influence Asian Americans’ emotional experiences of elections. The unexpected stability in stress levels during the election period warrants further investigation into the mechanisms underlying this emotional resilience. Future research should explore potential protective factors, such as community support systems, cultural resources, or specific coping strategies that might contribute to stress management during political events. Understanding these mechanisms could have important implications for supporting political engagement while maintaining psychological well-being. Additionally, research examining how generational status and acculturation levels influence emotional responses to elections could provide crucial insights. Given the diversity within the Asian American community, studies comparing first-generation immigrants with second- and third-generation Asian Americans could reveal how the political-emotional experience evolves across generations. This line of research could help identify how different aspects of cultural identity and political socialization interact to shape emotional responses to political events. Finally, future studies should employ mixed-method approaches to provide a more nuanced understanding of Asian Americans’ political-emotional experiences. Qualitative research, including in-depth interviews and focus groups, could complement quantitative findings by illuminating the personal meanings and interpretations that Asian American voters attach to their emotional experiences during elections. Such research could also help identify previously unexplored factors that influence political-emotional responses in this population.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights into how Asian Americans emotionally experience presidential elections, offering evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about political-emotional responses. The results showed increased positive affect on election day, stable psychological stress levels, and minimal partisan differences in emotional patterns. These findings suggest that existing models of political behavior may require adjustment when applied to minority populations, particularly those whose cultural norms influence emotional expression and management in political contexts. These outcomes have practical implications for political outreach and mental health interventions: engagement strategies should be culturally sensitive and avoid generalized assumptions about emotional vulnerability or partisanship within the Asian American electorate. Mental health professionals should recognize that political stress may manifest distinctly within this community, necessitating culturally attuned support approaches. Future research should employ larger, more diverse samples and examine cultural factors such as acculturation and generational status to deepen understanding of political-emotional responses. Theoretical integration between the AIR model and Social Identity Theory should be further explored to better understand how emotional resources and group identities interact in shaping political behavior among culturally diverse populations.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Age | 46.77 | 7.65 | |||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.81 | 0.39 | -.16 | ||||||

| 3. SO | 0.05 | 0.29 | -.51** | .09 | |||||

| 4. Race | 0.09 | 0.66 | -.26* | .06 | .89** | ||||

| 5. PA | 0.76 | 0.93 | .14 | -.08 | -.15 | -.11 | |||

| 6. Pos | 2.56 | 0.67 | -.02 | -.32* | -.12 | -.03 | -.31* | ||

| 7. Neg | 1.98 | 0.64 | -.14 | .32* | .19 | .10 | -.09 | -.08 | |

| 8. Pss | 1.55 | 0.52 | .14 | -.17 | -.17 | -.14 | -.01 | .12 | .18 |

Note. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. SO refers to sexual orientation, PA refers to political affiliation, Pos refers to positive affect, Neg refers to negative affect, and Pss refers to psychological stress. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. The confidence interval is a plausible range of population correlations that could have caused the sample correlation (Cumming, 2014). * indicates p < .05. ** indicates p < .01.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, Americans express worry over personal safety in annual anxiety and mental health poll, 10, May, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/annual-anxiety-and-mental-health-poll-2023? [↩]

- Pew Research Center. (2023). Asian Americans: A diverse and growing population. Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/ [↩]

- Lien, P. T. (2004). Asian Americans and voting participation: Comparing racial and ethnic differences in recent US elections. International Migration Review, 38(2), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00203.x [↩]

- Tufts University CIRCLE. (2020). Young Asian Americans, informed and engaged, still face barriers to vote. Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. https://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/young-asian-americans-informed-and-engaged-still-face-barriers-vote [↩] [↩]

- Advancing Justice – AAJC. (2023). Asian Americans in the 2022 midterm elections: A post-election report on voter experiences. Asian Americans Advancing Justice [↩]

- Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., Junn, J., & Wong, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage [↩]

- Tsai, J. L. (2013). The cultural shaping of emotion (and other feelings). Noba textbook series. http://nobaproject.com/modules/culture-and-emotion [↩] [↩]

- Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., Groenendyk, E. W., Gregorowicz, K., & Hutchings, V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: The role of emotions in political participation. The Journal of Politics, 73(1), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000939 [↩]

- Huddy, L. (2001). From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Political Psychology, 22(1), 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00230 [↩]

- Lee, J. C., & Kye, S. (2016). Racialized assimilation of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology, 42, 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074424 [↩]

- Baum, M. A., Druckman, J. N., Simonson, M. D., Lin, J., & Perlis, R. H. (2024). The political consequences of depression: How conspiracy beliefs, participatory inclinations, and depression affect support for political violence. American Journal of Political Science, 68(2), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12725 [↩] [↩]

- Cheah, C. S., Wang, C., Ren, H., Zong, X., Cho, H. S., & Xue, X. (2020). COVID-19 racism and mental health in Chinese American families. Pediatrics, 146(5), e2020021816. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-021816 [↩]

- Canady, V. A. (2024). APA poll: US adults anxious over election, current events. Mental Health Weekly, 34(19), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhw.33677 [↩]

- Shih, S. M., Wang, Y., Hallett, D., Johnson, S., Canetti, D., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2013). Political violence, psychological distress, and perceived health: A longitudinal investigation in the Palestinian Authority. Social Science & Medicine, 77, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.025 [↩]

- Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., Junn, J., & Wong, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage Foundation. [↩] [↩]

- Lien, P. T. (2004). Asian Americans and voting participation: Comparing racial and ethnic differences in recent US elections. International Migration Review, 38(2), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00203.x [↩]

- 24%; Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., Junn, J., & Wong, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage Foundation. [↩]

- Advancing Justice – AAJC. (2023). Asian Americans in the 2022 midterm elections: A post-election report on voter experiences. Asian Americans Advancing Justice. [↩]

- American Psychiatric Association, Americans express worry over personal safety in annual anxiety and mental health poll, 10, May, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/annual-anxiety-and-mental-health-poll-2023? [↩]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [↩]

- Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., Groenendyk, E. W., Gregorowicz, K., & Hutchings, V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: The role of emotions in political participation. The Journal of Politics, 73(1), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000939 [↩]

- Sue, D. W., Sue, D., Neville, H. A., & Smith, L. (2019). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [↩]

- Tsai, J. L. (2013). The cultural shaping of emotion (and other feelings). Noba textbook series. http://nobaproject.com/modules/culture-and-emotion [↩]

- Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., Junn, J., & Wong, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage Foundation. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. University of Chicago Press. [↩] [↩]

- Huddy, L. (2001). From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Political Psychology, 22(1), 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00230 [↩]

- Lien, P. T. (2004). Asian Americans and voting participation: Comparing racial and ethnic differences in recent US elections. International Migration Review, 38(2), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00203.x [↩]

- Tsai, J. L. (2013). The cultural shaping of emotion (and other feelings). Noba textbook series. http://nobaproject.com/modules/culture-and-emotion [↩] [↩]

- Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., Junn, J., & Wong, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage Foundation [↩]