Abstract

Financial exclusion restricts economic development worldwide by limiting access to savings accounts, credit, secure financial transactions, and safe investments. This study employs a survey to examine the research question of: How do financial perceptions and economic mobility differ between unbanked and banked populations in a developing and developed country? Two versions of the same survey, one in English and one in Gujarati, were answered by a total of 143 participants, where 95 were from Gujarat and 48 were from Los Angeles. Surveys were distributed using convenience sampling via digital and interpersonal networks. Data from the Likert Scale was analyzed using independent-sample Mann-Whitney U tests to measure perception differences. Results show that banked individuals in the United States interact more with formal financial institutions, perceive banking as beneficial, and visualize a direct correlation between effort and financial success (p <0.001). On the other hand, the results of surveys from India rely on informal financial systems and find it immensely difficult to save money (p <0.001). However, the survey’s convenience-based design and differences in age and education between groups limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should apply stratified random sampling, employ culturally validated survey instruments, and investigate similar populations with shared economic contexts. These findings highlight the urgent need for global policy interventions, such as financial literacy programs and financial technology expansion, to promote economic mobility.

Keywords: economic mobility, financial exclusion, banking in developing countries, India, U.S.A.

Introduction

Globally, nearly 1.4 billion adults remain unbanked, with the majority residing in developing countries, where financial exclusion perpetuates poverty cycles. Access to banking services is a fundamental idea of economic mobility which is defined as the ability to improve socioeconomic class over time. However, systemic barriers such as infrastructural shortcomings, identification constraints, and low financial literacy rates prevent millions from improving their financial situations. While digital financial services and mobile banking have emerged as potential solutions, their effectiveness is inconsistent due to digital literacy limitations. Existing research highlights the role of financial access in poverty alleviation (e.g., Banerjee and Duflo, 2007; Kranton, 1996; Schechter, 2015)1’2, but direct analysis between first-world and developing countries remains limited. This study analyzes survey data on banking access in Gujarat, India, and Los Angeles, California, to examine how financial exclusion impacts economic mobility. As an area in a developing economy, Gujarat contains high levels of informal labor and low financial access, while Los Angeles offers expansive financial infrastructure and a highly banked population. By contrasting these findings with each other, this research seeks to bridge the gap in understanding global financial inclusion and barriers to banking access.

Financial perception, defined as an individual’s preconceived notions about financial tools, infrastructure, and opportunities, plays a crucial role in how people interact with available services. Limited trust or understanding of financial services inhibits an individual’s ability to save, borrow, and invest. This restricts their ability to build wealth and plan for the future. This lack of engagement in formal financial systems ultimately reduces economic mobility. The research is guided by the overarching question: How do financial perceptions and economic mobility differ between unbanked and banked populations in a developing and developed country?

Next, this study hypothesizes that banked individuals will report greater trust in financial institutions, participants from Los Angeles will perceive certain financial tools, like loans, as easier to obtain, and the unbanked population in Gujarat will find it much harder to improve their financial state through hard work. Ultimately, this study adds to the broader conversation on financial inclusion, the principle that equitable access to fair financial services can reduce socioeconomic inequality and improve economic opportunity.

Lastly, the study incorporates two Google-Forms-based surveys, one completely in English and the other one in Gujarati. Survey questions focused on banking access, financial literacy, and the value of financial tools. In this paper, the following sections include a literature review that contextualizes the study within prior research, a methods section that outlines the data collection, a results section with important findings, a discussion of implications and limitations, and a conclusion with future possibilities.

Literature Review

Throughout the literature review, many terms will be used that require preliminary definitions. In this context, ‘banked’ means individuals who utilize a formal banking institution. On the contrary, ‘unbanked’ means individuals who do not rely on or use formal banking institutions. ‘Financial exclusion’ refers to the lack of access to financial services, such as banking, credit, and loans, which prevents individuals from complete involvement in their formal economy.

Financial exclusion inhibits economic development worldwide by restricting access to savings accounts, credit, secure financial transactions, and safe investments. Unbanked populations often suffer from financial instability disproportionately, with reduced economic mobility, and lower rates of saving and maintaining money3. The consequences of financial instability are substantial in developing countries, where a combination of uneducated populations, weak infrastructure, and distrust in financial institutions ultimately reduce financial benefits4. On the other hand, banked populations in first-world countries receive larger and more impactful financial benefits, such as secure money storage, access to credit and loans, and savings accounts5.

Scholars have explored the financial behaviors of poor populations in developing economies, exploring how the unbanked manage money through social networks, informal savings groups such as rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs), and cash-banked transactions1. Similar insights are provided while analyzing how unbanked families and individuals in the developing countries of South Africa and India interact with financial instability using similar informal means (Schechter, 2015).

On the other hand, in the economies of first-world countries, financial exclusion has less to do with infrastructural concerns and lack of banking access; it is more about systemic barriers3. One significant group of renowned economists explored how financial systems in developed countries perpetuate the idea of economic inequality2. This concept leads to failures in loan approvals, credit access, and accumulating wealth in general. Also, reports from the Center for American Progress highlight how predatory lending, high interest rates, and minimum balance requirements disproportionately affect poor and marginalized communities in first-world nations. As poor communities even in developed countries lack access to substantial bank loans, they must seek payday loans, which ultimately contribute to their debt. In most cases, individuals relying on payday loans must seek another short-term loan to cover the extremely high interest rates (American Progress, 2016).

In summary, extensive research has been done on developing or first-world countries. But, there is a large gap in analyzing the financial mindsets of unbanked and banked populations in developing and developed countries, which this research paper will fill.

Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Access to formal financial institutions is critical in defining how individuals save, borrow, and invest money. The differences between banked and unbanked populations are immense in how these groups typically go about managing their money. It is predicted that 27% of the world’s adults remain unbanked, with the highest concentrations in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The problem of being unbanked affects around 1 in every three adults globally, a testament to the grand scale of this issue6.

That said, there are fewer complications when acquiring a bank account in first-world countries than in developing countries. In developed countries, banks are highly abundant in urban and rural areas, making access to banks immensely higher for every subgroup of people within these countries3. This rivals developing countries, as rural communities may be far from the nearest bank branch, whereas in developed countries, there is a widespread network of physical bank branches and ATMs. Additionally, in developed countries, there exists the ability to access bank accounts digitally, leading to fewer visits to the bank. With digital banking options, individuals can open accounts, wire money, and deposit checks remotely, which has extreme benefits for the populations of people in developed countries who face geographical barriers to physical banks4. In first-world countries, free or low-cost checking and savings accounts further incentivize individuals to use bank accounts to manage their money. Also, legal protections prevent financial institutions from charging excessive fees, while in developing countries, hidden fees are a significant deterrent that inhibits an individual’s desire to utilize a bank3.

Furthermore, the frequency of individuals possessing formal identification like nationally registered IDs, social security numbers, and passports in first-world countries contributes to the difficulties of opening a bank account5. Compared to the millions of people who lack identification in developing countries, it becomes clear why using a bank may appear impractical and useless. However, the issue of the documentation barrier to opening a bank account is being resolved with initiatives similar to India’s Aadhaar biometric ID system. This unique system links Indian citizens’ fingerprints and irises to a unique 12-digit number to verify identity. It was initially designed to reduce fraud and expand financial inclusion by enabling access to banking, digital payments, and welfare without relying on formal documentation. This strategy has increased banking usage in India. However, concerns about privacy and data security still exist. On the other hand, the Aadhaar biometric ID system can still act as a barrier to financial exclusion if 12-digit numbers are handed out to many but not all citizens, worsening the repercussions of financial exclusion for the remaining unbanked7.

As there are fewer complications with obtaining a bank account in developed countries, members of developing countries still take the initiative to manage money intelligently. Individuals in developing countries generally rely on Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) and Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations (ASCAs) to save and borrow money safely. These methods benefit rural and poor communities by establishing a reliable lending system without the need for the intervention of formal banks1. Additionally, individuals in developing countries store their cash in physical assets like bricks, gold, livestock, and small plots of land. These strategies are safe for keeping cash without fearing robbery or immense depreciation. If individuals do not invest their money in assets, they store cash under their mattresses and other nontraditional locations in their property8.

Systemic and Behavioral Causes

After establishing the infrastructural and documentation-based barriers to financial inclusion, systemic mistrust prohibits individuals in developing countries from utilizing formal financial institutions. Due to historical bank failures, individuals perceive banks as untrustworthy, unstable, or exploitative. For example, the Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank Scam of 2019 led to severe financial losses for citizens after one of India’s largest cooperative banks lent out fraudulent loans and misreported financial losses. Beyond individual scandals, systemic mistrust of banks in India stems from a history of poor consumer protections, hidden fees, and unfair practices. According to a study by the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP), nearly 40% of rural Indian respondents declare mistrust towards banks as a key reason for avoiding formal financial institutions. This feeling is strengthened by the notion that banks prioritize the wealthy and well-connected individuals, leaving ordinary citizens isolated. (CSEP, 2022).

Along with the idea that individuals lack trust for banks, formal financial institutions do not give citizens a comprehensive idea of what having a bank account entails. In response to low financial inclusion ratings, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi created Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), an initiative dedicated to opening bank accounts for rural Indian populations. Although this enticing initiative has opened more than 355 million accounts in five years, 83% of recently created accounts remain inactive. About this issue, Harvard economics professor Rohini Pande said, “[The government has] incentivised people to open these accounts, but has done less to increase usage or provide them with enough information…poor training programmes and an initial focus on hitting account-opening targets meant that bank staff often fail to communicate all the benefits.” This is a crucial shortcoming for banking in India because having a bank account without an idea of the benefits that it might have is meaningless9. In summary, as individuals in developing countries distrust financial institutions due to corruption and past failures, they tend not to rely on typical financial institutions to manage their money3’5’4.

Strategies for Improving Inclusion

After outlining some problems to financial inclusion, it is crucial to locate a solution. However, the problem of financial exclusion in third-world countries necessitates a complex approach, without one distinct solution. This approach would address structural barriers, institutional shortcomings, and behavioral tendencies. When contrasting developing nations to first-world countries, there are clear differences between societies and how they interact with their finances5.

Firstly, one of the most significant dividers to financial inclusion in low-income and rural regions of developing countries is the lack of physical banking infrastructure. Without implementing bank branches, ATMs, and agent banking networks, it is extremely hard to increase previously low levels of financial participation. To resolve issues of lack of bank branches, the government of Brazil incentivizes established banks to open rural branches and digital banking kiosks. Additionally, other strategies have taken place to promote the usage of established banks. For example, countries like Kenya and Bangladesh have implemented agent banking models where local businesses serve as intermediaries for banking services. This initiative reduces the need for common citizens to visit banks but instead allows individuals to deposit, withdraw, and transfer funds through local shops4.

Luckily, in the present day, mobile banking is a large factor in how global citizens manage their finances. The rise of mobile banking and financial technology has opened new opportunities to reduce gaps of financial exclusion within developing countries. Generally, digital banking solutions reduce costs, increase accessibility, and improve rates of financial literacy. One of the approaches to integrating mobile banking to aid low rates of financial inclusion was the previously discussed PMJDY program, which created millions of bank accounts for rural populations by providing them with zero-balance bank accounts. Also, M-Pesa in Kenya has provided a model for financial inclusion, highlighting how mobile money services can successfully integrate unbanked individuals into the modern financial system. This specific application allows their users to store, send, and receive money through a mobile app. Applications like Airtel Money and MTN Mobile Money also offer savings accounts, bill payment financing, and small business loans. Throughout the world, the integration of unbanked populations into digital finance services has assisted in bridging the gap of financial inclusion5. With that said, there are still challenges regarding adopting mobile banking everywhere. For example, the lack of digital literacy in developing countries restricts a high population of potential users from accessing the benefits of online banking applications. Also, more mobile network infrastructure and internet access would be crucial in maximizing the unbanked population relying on digital banking solutions (Innovation & Entrepreneurship, 2021).

Next, microfinancing has been globally recognized as a successful tool for promoting financial inclusion in developing countries. Microfinance institutions such as the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and BRAC Microfinance have successfully provided small loans, financial training, and business development to support millions of individuals. Although microfinancing is beneficial, high interest rates and debt accumulation pose potential risks to borrowers. Strict oversight is necessary to limit exploitation in these low-income communities10.

Lastly, financial literacy is essential in ensuring that both banked and unbanked individuals make financial decisions informedly. Educational programs that are integrated into school curricula have the power to assist future generations in developing healthy financial habits. For example, in Australia and the United Kingdom, schools have implemented financial education within their school systems, improving financial literacy rates in the next generations. Although these countries are developed, the next step is to potentially implement financial literacy into the curriculum of schools in developing countries as well. This would raise low financial knowledge rates and resolve suspicion around traditional financial institutions in these low-income and rural communities. This act would strengthen trust in modern banking systems, encouraging users to open bank accounts everywhere. Additionally, increased financial literacy rates can help address the flaws associated with predatory lending, such as high interest rates and customer exploitation3.

Literature Review Summary

While Banerjee and Duflo emphasize the creative financial practices among unbanked populations in developing countries through informal methods such as ROSCAS, Schechter contrasts this by highlighting these methods’ systematic vulnerabilities. On the other hand, Kranton and the FCA show that financial exclusion in developed countries is often tied not to lack of infrastructure but to systemic discrimination. Together, all these authors reveal that while the nature of exclusion differs across situations, its impact is universally destructive.

The financial behaviors and perceptions of banked and unbanked populations differ immensely between developing countries and first-world economies. In developing countries, the unbanked traditionally utilize informal savings groups, asset-based wealth storage, and community-based lending networks. These strategies tend to be used instead of traditional banks because of limited banking infrastructure, documentation barriers, and mistrust in typical financial institutions. On the other hand, first-world nations experience lower proportions of being unbanked due to sufficient infrastructure, mobile banking, and trust in financial systems. These polar differences create different behaviors when interacting with finances and instill distinct perceptions in both populations. These differences in banking access directly impact economic stability and financial security. This research paper seeks to answer how different perceptions of banks affect financial behavior by contrasting the views of unbanked individuals in India with banked individuals in the United States. Comprehending these distinctions provides valuable insights into implementing strategies to combat financial inclusion in countries, tailored to specific needs.

Methods and Data

This study employs a survey-based methodology to assess how financial perceptions differ between banked and unbanked populations in a developed country (the United States of America) and a developing country (India). The specific locations of Los Angeles and Gujarat were targeted as they are two locations with extremely different financial environments. Additionally, they are both places where funding and resources permit surveys to be distributed by trusted enumerators. To conduct the survey, a list of questions was thoughtfully formed and sent to recipients. The Gujarati version of the survey was translated using translation-based artificial intelligence tools and then reviewed by native speakers with a background in education and finance to ensure conceptual and grammatical accuracy. Using Google Forms, the survey was then created in both English and Gujarati. To preface, no question was open-ended; all questions either utilized the Likert scale or were multiple choice. All survey questions are shown below.

- What is your gender?

- What is your age?

- What is your marital status?

- What is your job?

- How many people depend on your income financially?

- Are you unbanked (Do not have a bank account)?

- (If yes to the previous question) Do you believe having a bank account would improve your financial situation?

- Peer-to-peer lending is something I use.

- I’m familiar with cryptocurrency.

- I’m familiar with stock trading.

- If you needed a loan tomorrow, where would you go first?

- Where do you believe is the safest place to store extra cash?

- Have you ever lost a large amount of money?

- I carry cash when I go out.

- It’s hard for me to save money.

- If you received a large sum of money today, what would you do with it?

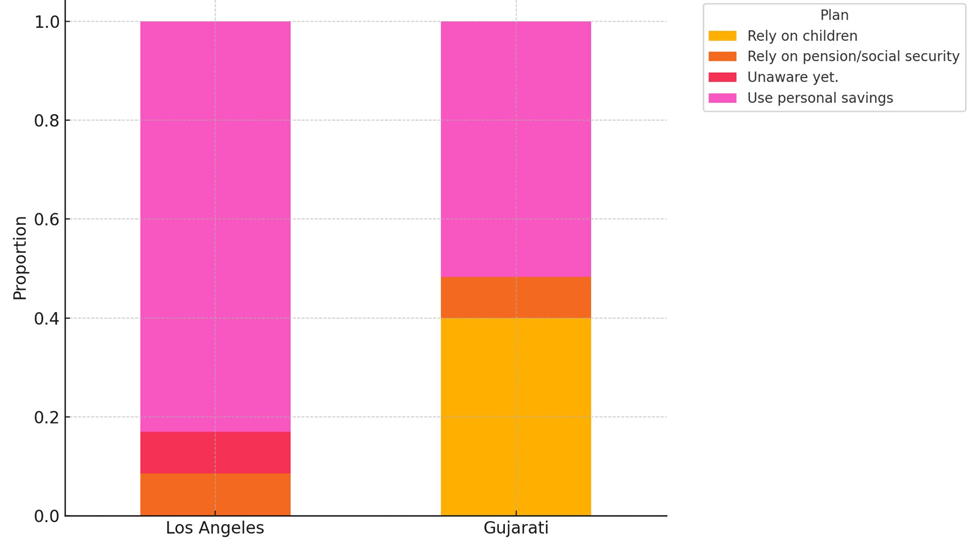

- What is your financial plan for old age?

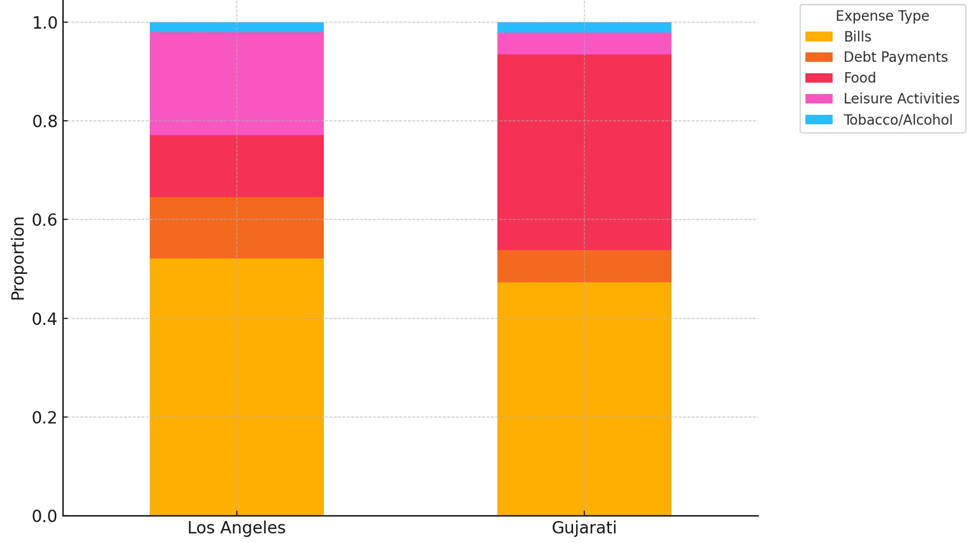

- What are your biggest expenses?

- I make most of my financial transactions in person.

- I find it easy to get a loan.

- How easy do you think it is to improve your financial state through hard work?

- How much of your financial state depends on your family’s wealth?

- At the age of 50, I am/will be more financially successful than my parents.

- I predict my children will be more financially successful than me at the age of 50.

- Money is a major stressor for me.

- Money is a major stressor for my family.

Next, the distribution varied depending on which survey was sent out. For example, the survey, which had to be translated into Gujarati, was emailed to a select number of Gujarati individuals who were tasked with distributing the survey amongst their family and friends. To find these individuals, my grandfather contacted many acquaintances who still live in India. Specifically, the Gujarati survey was sent out in the rural area of Surat, a large city in the state of Gujarat with a population of 6.937 million. Additionally, this survey accumulated ninety-five diverse responses. On the other hand, the English survey was distributed within Los Angeles, a large city in California with a population of 3.821 million. The distribution process entailed emailing this survey to many family members, friends, and mutual connections to achieve the maximum number of responses. With that said, the English survey accumulated forty-eight unique responses.

To address some holes in the data-gathering process, this survey encountered non-response and selection bias. As the survey was seen by many people who ultimately didn’t put in the time or effort to respond to it, there was a slight presence of non-response bias. This type of bias was also present when individuals in the Gujarati survey simply skipped over certain questions. This is due to many reasons, but most importantly, “Some of the surveyors didn’t understand what the questions were asking because they weren’t educated well enough. The people in Gujarat don’t know what stocks or cryptocurrencies are. They haven’t even thought about long-term retirement planning. They have never even heard of loans.” This quotation from an interview with Mahendra Patel, an enumerator of Gujarati surveys in India, reveals the lack of education that inhibits certain Gujarati surveyors from answering questions thoughtfully and completely. It is also crucial to acknowledge that because these surveys were distributed via personal contacts and family members, an enormous amount of selection bias was introduced. To reduce this selection bias, efforts were made to ensure representation from both banked and unbanked individuals across a wide range of ages. To address literacy challenges, enumerators would have administered the survey orally and then recorded their verbal responses in the Google Form. All surveys were conducted anonymously to encourage honest and unbiased responses.

Additionally, the difference in responses between the two surveys is important to acknowledge. Since the sample size of Gujarati individuals is forty-seven people greater than the Los Angeles survey, there is a greater amount of variance in the Los Angeles survey, potentially leading to misleading conclusions. On the contrary, both of the sample sizes are greater than thirty, a common rule of thumb for the minimum sample size at which asymptotic normality is likely to be satisfied.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Google Sheets. The primary quantitative method used was the independent sample Mann-Whitney U test, which was applied to compare mean responses between Gujarati and English responses. The Mann-Whitney U test is a non-parametric statistical test used to compare two independent groups when the data is not normally distributed. The two independent groups in this context are the Gujarati responses and the English responses. The Mann-Whitney U test values were calculated using a free online calculator. This test was selected in order to determine if observed differences in financial perception scores were statistically significant.

Results

After receiving sufficient responses to both surveys, very interesting results emerged. Assisted with Table 1 below, the demographics of the surveyors are extremely important to highlight. The mean age of Los Angeles surveyors is 42.44 while the mean age of Gujarati surveyors is 32.63, highlighting how, on average, the Gujarati surveyors were around ten years younger than the Los Angeles-based surveyors. Also, the mean number of people who depended on any given surveyor was 3.02 and 3.63 for Los Angeles and Gujarati surveyors respectively. As these values are relatively similar, both groups of this sample typically have a similar number of people who depend on their income financially. The proportion of males within the sample was larger in the Gujarati sample (0.8210) compared to the Los Angeles survey (0.685). This could be attributed to gender barriers in rural India, which include the stigma of male-dominated financial decision making, lack of female employment, or even possibly digital literacy gaps. On the contrary, the proportion of married surveyors stayed relatively consistent between groups, with 0.7291 for Los Angeles and 0.6736 for Gujarat.

The sample’s occupational data was one of the most interesting and relevant demographic statistics. The most popular occupation among Los Angeles-based surveyors was to be self-employed, which covered 10.42% of all Los Angeles responses. The idea of being self-employed assumes ownership of some sort of skill or business that requires extra attention to financial information. In the Gujarati survey, the most popular occupation was a business owner, which captured 29.67% of all Gujarati responses. It is essential to acknowledge that the predominant occupation among both groups was business owners, as people who possess ownership over a company, business, or skill interact with things like loans, investments, and revenue in a way associated with their business and their encounters.

Most importantly, it is crucial to acknowledge the difference in the proportion of unbanked individuals between the two areas. In Los Angeles, the proportion of unbanked surveyors was 0.1224, while the proportion of unbanked surveyors in Gujarat was an immense 0.5154. After conducting a two-proportion z test, the p value is <0.001, proving that this difference was statistically unlikely to occur by chance. This extreme gap aligns with the information in the literature review, which lists reasons why there is a higher proportion of unbanked individuals in developing countries than in first-world countries. This difference in the proportion of unbanked individuals will be crucial in analyzing results from further questions.

After observing the survey demographics, significant differences emerged between the Los Angeles and the Gujarati surveyors, visualized on Table 2 below. These differences resulted in age gaps, gender gaps, and individual gaps. When observing the survey questions’ results pertaining to financial perceptions, significant differences are highlighted once again. The questions were asked on the Likert scale, where 5 was the strongest answer. Firstly, a primary example of this divide is highlighted when individuals were asked whether having a bank account improves their financial situations. Using the Likert scale of 5 signifying strongly agree and one signifying strongly disagree, the mean response in Los Angeles was 4.36 (81% agree or strongly agree), and in Gujarat, it was 2.91 (45% agree or strongly agree). This suggests that Los Angeles surveyors overwhelmingly recognize the benefits of utilizing a bank account, while Gujarati surveyors are either skeptical or unfamiliar with the advantages of formal financial institutions. This once again aligns with the contents of the literature review, which provides reasons as to why Indian populations have a sense of mistrust for traditional banks. Also, the significant increase in unbanked populations between Gujarat and Los Angeles further contributes to the attitude that having a bank account does not improve financial situations. This can be explained by the idea that if roughly 90% of people in your area (Applicable to the Los Angeles demographic) use a bank account, it will be assumed that it benefits financial situations. Also, the people who do not utilize a bank account become a minority who lack access to benefits shared by the majority, increasing the urgency for unbanked populations to acquire a bank account.

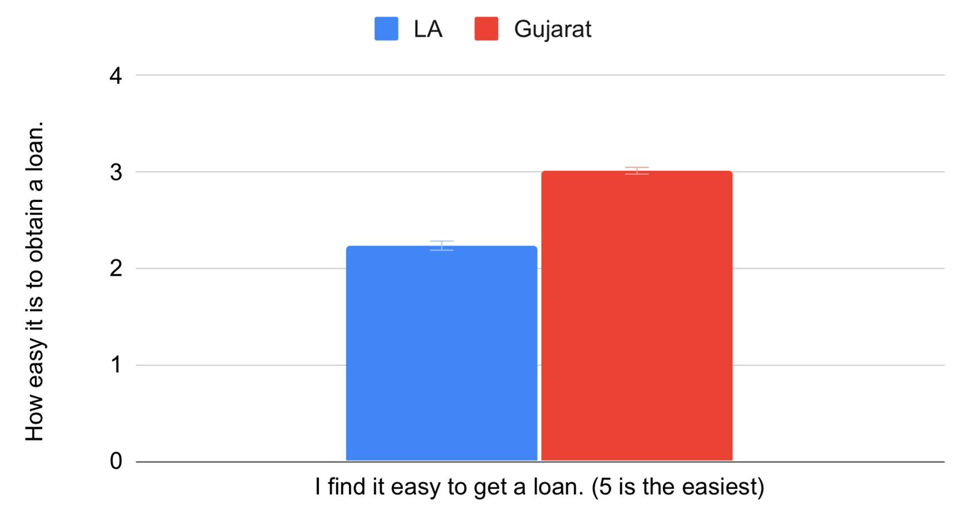

When asked about familiarity with stock trading, Los Angeles surveyors had a mean response of 3.70 (57% agree or strongly agree), while Gujarati respondents reported a mean of 2.20 (19% agree or strongly agree). The difference is even more divided when prompted about familiarity regarding cryptocurrency, where the mean among Los Angeles respondents was 3.70 (51% agree or strongly agree) compared to an almost negligible 1.32 (9% agree or strongly agree)in Gujarat. This extreme difference reinforces that investment opportunities, especially digital financial tools, are much less popular in developing countries, limiting future financial growth through cryptocurrency and stock markets. This division also attests to both the gap of digital literacy as well as financial literacy of populations in rural India compared to a grand city in the United States. This divide is also present when prompted about credit. When asked if surveyors find it easy to obtain a loan (Figure 1), Los Angeles respondents had a mean response of 3.52 (50% agree or strongly agree), compared to 2.40 in Gujarat (26% agree or strongly agree). Below, graph B.2 proves this gap, as a 95% confidence interval was constructed with error bars that are practically invisible due to such a low margin of error. The two different means were far apart mathematically as the p-value after conducting a Mann-Whitney U test was <0.001, much less than the alpha value of 0.05. As the p-value is less than 0.05, the difference is statistically significant, meaning that we have convincing evidence that the difference was not due by chance.

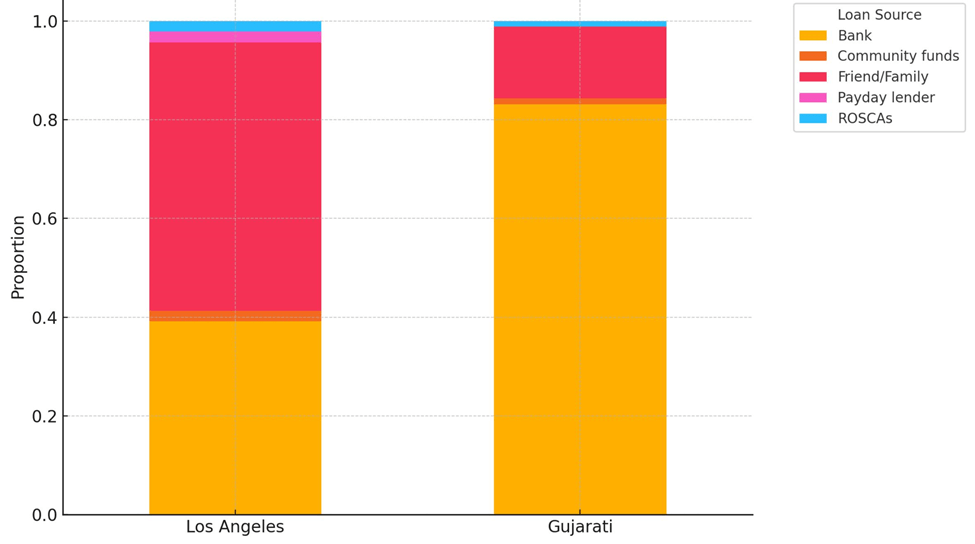

This difference in ease of obtaining a loan implies that accessing formal credit is much more challenging for Gujarati respondents. This could be due to various reasons, including fewer banking relationships, strict lending standards, or a more substantial reliance on informal financial networks. This aligns with the slight increase in peer-to-peer lending usage in Gujarat (2.43) compared to Los Angeles (2.04), suggesting that people will utilize alternative lending methods when formal banking access is limited.

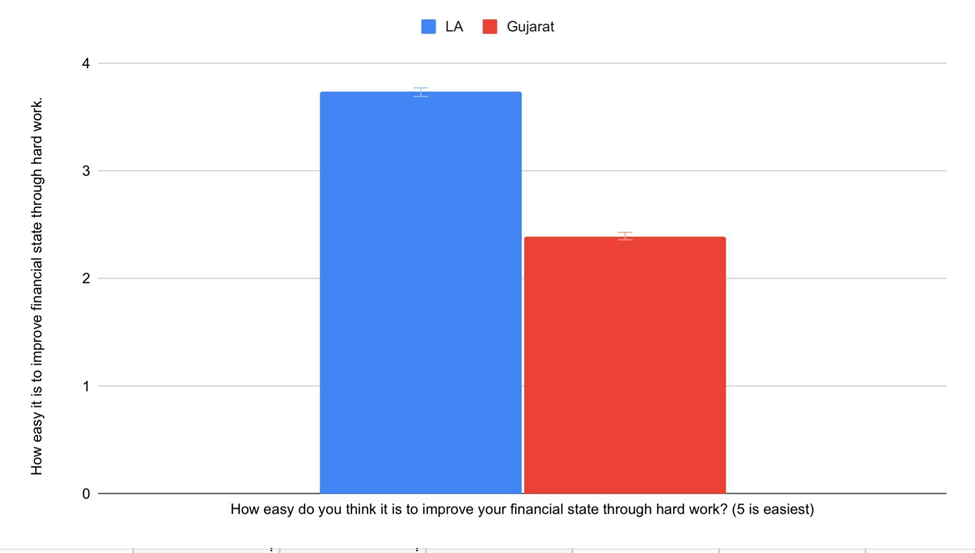

Interestingly, responses regarding financial mobility reflect a similar pattern. Assisted by Figure 2, when asked if it is easy to improve their financial situation through hard work, Los Angeles surveyors gave a mean response of 3.73 (58% agree or strongly agree). In comparison, Gujarati respondents reported 2.42 (28% agree or strongly agree). This gap suggests that the Los Angeles surveyors perceive a more direct relationship between effort and financial success. In contrast, the Gujarati surveyors generally believe that effort has no direct correlation to financial success. This could be because people in most developing countries feel constrained by structural, social, and economic barriers, preventing financial class mobility. Mathematically, a 95% confidence interval is present with error bars that practically seem invisible. This gap is statistically unlikely to occur by chance due to a significantly low p-value of <0.001 after conducting a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

This idea is further reinforced when observing generational financial comparisons. Figure 3 shows that Los Angeles surveyors were much more likely to say they are/will be more financially successful than their parents at age 50, with a mean of 4.15 compared to Gujarati respondents, 2.69. The American surveyors expressed extreme ideas of being on track to be wealthier than their parents by age 50. In contrast, Gujarati surveyors felt roughly indifferent about this concept, with their mean falling near the middle. The difference is visually significant and mathematically relevant on the graph, as the p-value is <0.001, meaning that the gap is statistically significant.

However, both groups express optimism for the future, with Los Angeles respondents assuming their children will be more financially successful than themselves at a mean of 4.00 (70% agree or strongly agree). In comparison, Gujarati participants reported a slightly lower mean of 3.44 (55% agree or strongly agree).

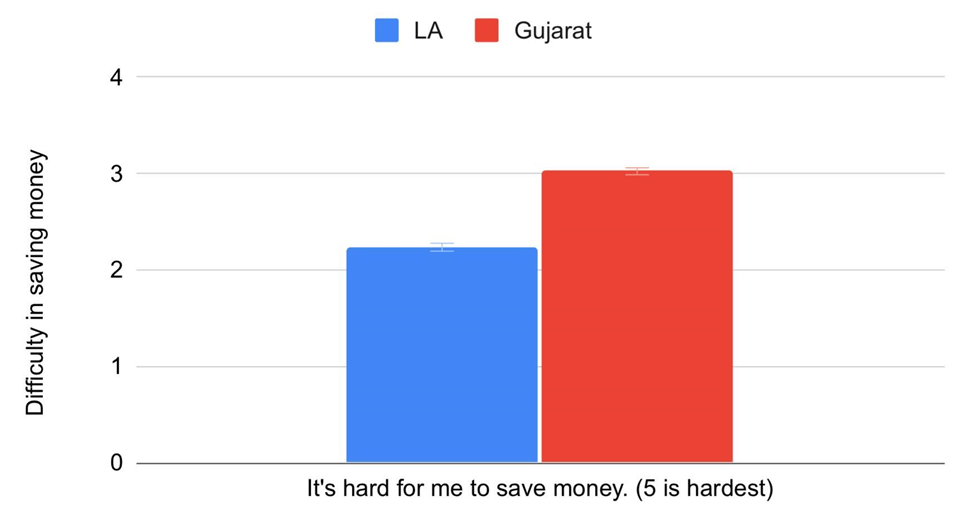

One of the most crucial factors in ensuring financial stability is savings behaviors, an area where Gujarati respondents report significant difficulty. When asked if it is difficult to save money, Los Angeles surveyors had a mean response of 2.23 (6% agree or strongly agree). In comparison, Gujarati surveyors had a notably higher mean of 3.01 (41% agree or strongly agree). This difference suggests that savings constraints are far more prevalent in Gujarat and can be associated with developing countries. This is likely due to lower disposable income, lack of access to banking, or inconsistent earnings. This question’s results are assisted by Figure 4. The graph has a practically invisible margin of error and a statistically significant p-value of <0.001 after conducting a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

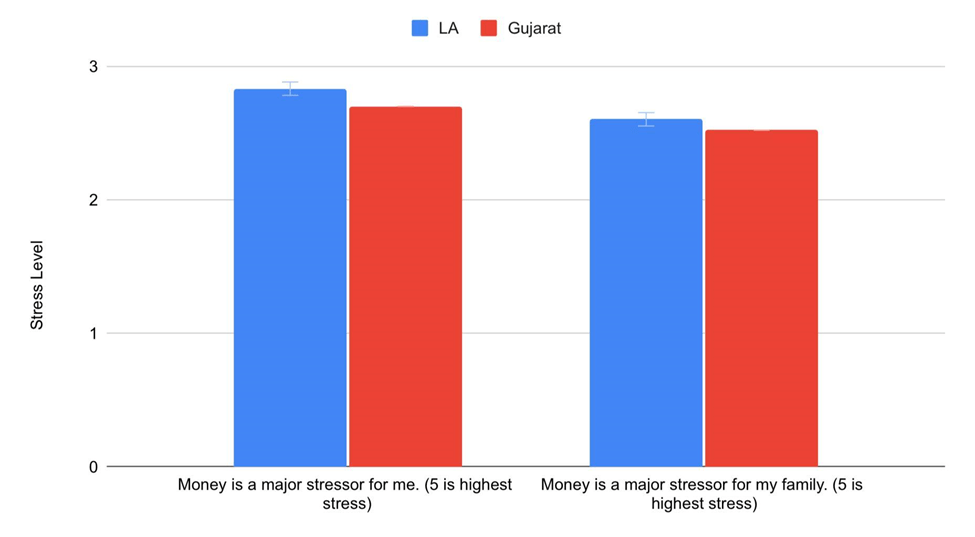

The responses regarding financial stress reveal key differences between surveyors in the developing area of Gujarat and the first-world city of Los Angeles, revealing how access to financial institutions affects individual well-being. Assisted with Figure 5, when asked if they were under financial stress individually, the mean response in Los Angeles was 2.83 (31% agree or strongly agree), while in Gujarat, it was 2.7 (34% agree or strongly agree). This extremely small difference suggests that personal financial stress levels are relatively comparable between the two areas, despite the larger disparities in banking access, financial literacy, and digital literacy. One possible explanation for this result is that while Gujarati surveyors face significant financial barriers, their financial stability expectations may differ completely from those in Los Angeles. Additionally, the perception of financial stress within families proves even more similar, with a mean response of 2.60 in Los Angeles (21% agree or strongly agree) and 2.52 in Gujarat (81% agree or strongly agree). This close alignment indicates that financial burdens at the household level may be widespread across both regions, despite very prevalent differences in banking access. These key statistics reveal how even through underdeveloped financial institutions, Gujarati respondents have marginally lower stress levels, prompting the question: do people in developing countries even feel the need to utilize formal banking systems?

Given that Gujarati surveyors report lower banking access, lower familiarity with investment strategies, and greater difficulty obtaining loans, it would be expected that their financial stress levels would be significantly higher. The fact that they aren’t highlights that other cultural or economic factors mitigate levels of stress, such as reliance on informal lending networks or different expectations of financial success.

The results of this survey highlight the immense impact that being banked or unbanked have on various financial behaviors or perceptions, particularly when comparing populations in the developed economy of Los Angeles or the rural and developing economy of Gujarat. The significant gap in banking access where only 12.24% of Los Angeles surveyors were unbanked and 51.54% in Gujarat surveyors are unbanked, potentially correlates to the extreme differences in investment familiarity, loan accessibility, and attitudes towards financial mobility. As the data suggests, banked individuals in Los Angeles are more engaged with formal financial institutions like banks, stocks, and cryptocurrency, and have a strong belief that banking improves financial well-being. On the other hand, the unbanked population in Gujarat have skepticism, possibly stemming from institutional mistrust and frequent usage of informal financial networks. This divide extends further than banking habits, it influences general perceptions of financial opportunity and success as seen in lower Gujarati responses regarding financial mobility and generational wealth expectations. Despite the disadvantages that prohibit Gujarati surveyors from utilizing formal banking services, financial stress levels remain relatively comparable, suggesting that unbanked populations in Gujarat may normalize financial instability as a fixed condition instead of a current issue.

Discussion

The findings of this study prove the significant role that access to banking plays in shaping economic mobility and financial perceptions, particularly in developing countries. This research reveals that individuals without access to formal banking institutions face financial constraints that limit their ability to save, invest, or manage credit. Compared to counterparts in first-world countries, the unbanked in developing economies show much lower levels of financial stability and a decreased correlation between financial success and effort. Additionally, while peer-to-peer lending and other alternative financial systems offer financial relief to unbanked populations, they do not fully replace the benefits of traditional banking infrastructure. The results of the survey imply that populations in India do not visualize a correlation between having a bank account and having financial success. This could be due to deep-rooted skepticism and mistrust in financial institutions, reliance on informal lending, or dependence on cash transactions.

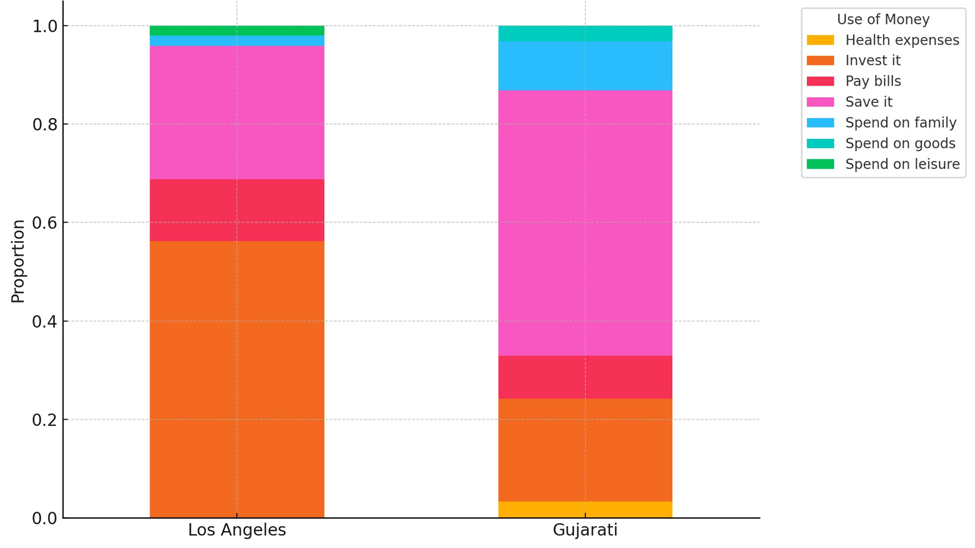

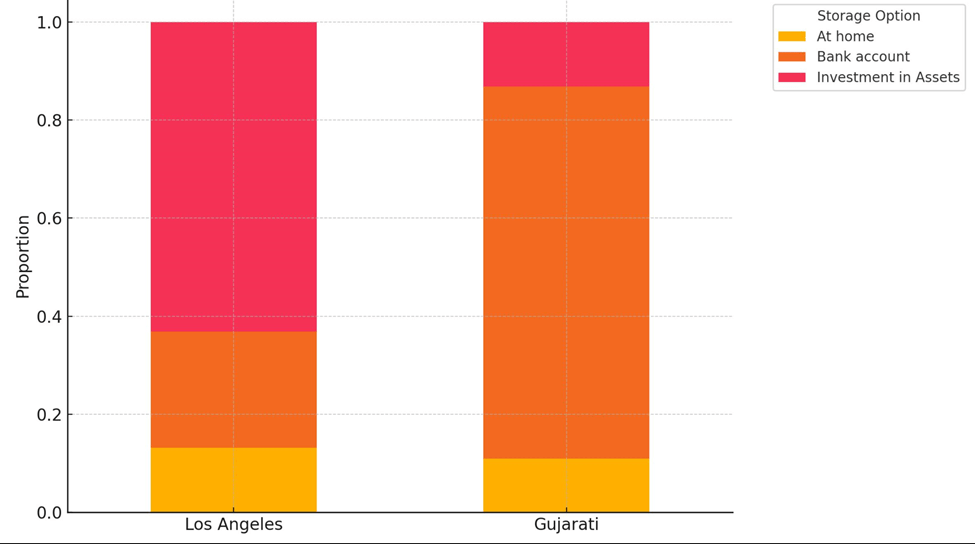

The survey findings deepen modern understandings of how institutional trust, cultural practices, and infrastructural limitations mold financial behavior in unbanked populations. In Gujarat, the preference for storing wealth in physical assets or relying on family networks confirms Banerjee and Duflo’s (2007)1 argument that financial exclusion does not necessarily translate to financial inactivity. Instead, individuals in these developing areas have informal methods of saving and borrowing. Gujarati respondents indicated that they would store money in investments or houses but the overwhelming majority claimed to store it in a bank account. When referring to Figure A.5, it is interesting to see that a larger proportion of individuals in Gujarat would safely store money in a bank account than Los Angeles respondents would. Around 75% of Gujarati respondents selected a bank account for the question, “Where do you believe is the safest place to store extra cash?” Considering that only 48% of Gujarati respondents have a bank account, this raises an interesting point. Essentially, people who do not even have a bank account believe that a bank account is the safest place to store their money, so why don’t they simply open one? This could be due to the many reasons discussed in the Literature Review, such as lack of financial literacy or infrastructural shortcomings. However, these findings show that the Gujarati people believe banks are a safe place to store money, which conflicts with Cicchiello’s (2021)8 observations that individuals in developing countries would store money in gold, property, or at home. This may be due to a large wave of institutional trust starting to develop in India in response to Modi’s PMJDY program.

With the study results, it is crucial to address the immense confounding in the procedure. Countless variables, such as age, personal experiences, and cultural differences, could affect an individual’s financial perceptions. Due to the confounding, it is impossible to claim a causal relationship between banking or development status and financial perceptions. However, the results do show a strong correlation between the variables. The confounding of the survey makes it impossible to generalize the results to all unbanked individuals or all people in developing countries. Future research with more funding and resources should observe the same research question under two possible procedures: 1) compare banked vs. unbanked populations within the same country/region, or 2) compare similar banking status groups across countries while controlling for development level and cultural factors.

The Gujarati survey received 95 responses with a mean age of 32.63, while the Los Angeles survey received 48 responses with a mean age of 42.44. This ten-year age gap, a major study weakness, introduces an important demographic distinction that may influence financial perceptions of behavior. As age is a confounding variable in this study, perception differences cannot be purely attributed to geography or banked status. Younger respondents in India may be more open to mobile banking but may also lack experience with formal institutions. Conversely, older participants in Los Angeles may have longer histories with banks and greater exposure to financial systems. Author Gary Drenik supports this in the Forbes article, “Younger Generations Demand Better Digital Banking In 2025”. He explains that traditional banking systems must adapt to younger generations who desire a digital banking experience. These differences are important to distinguish as they could partially account for gaps in financial trust and engagement perception. Future research should consider age-matched sampling to isolate the effects of age on financial perception.

The impact of financial exclusivity is immense. In low-income communities, intergenerational poverty cycles are created due to the inability to save securely or make informed investments to mobilize economically. Reliance on informal lending networks in developing countries further perpetuates economic instability, as systems practice unfair and corrupt strategies that perpetuate the poverty cycle. This research also explores how digital financial services are a viable solution to financial exclusion. However, digital and infrastructure barriers still restrict them from being completely accessible.

Policy interventions must be implemented to reduce financial exclusion, notably in developing countries. Governments should prioritize financial exclusion initiatives, such as building stronger microfinance programs, incentivizing banks to assist low-income populations, and adding financial literacy courses into the youth curriculum. Financial technology companies must also take responsibility for bridging the gap between the banked and unbanked populations. While increasing financial literacy education is one part of the solution, it is insufficient. The data suggests that distrust stems from a fundamental lack of knowledge, perceived institutional unreliability, and negative past experiences. To amend those issues, institutional reform must also exist.

Policymakers should prioritize community-based trust-building programs that involve local financial representatives, transparent service outlines, and constant regulation and oversight. In this way, community members, especially in rural areas, can all work towards building trust in formal financial institutions. Policymakers could promote using traditional banking systems in city events such as fairs, sports events, and farmers’ markets. When the average person has a hands-on understanding of a bank’s benefits and wholeheartedly believes there will be consistent regulation, their view will be absorbed by the entire community. Additionally, institutional reform could occur by expanding traditional infrastructure to low-income zip codes to erase a potential distance barrier for individuals.

Despite this study’s immense contributions, it still has several limitations. The reliance on survey data introduces potential biases, including self-reported inaccuracies to seem informed and intelligent. If this study had access to more time and funding, the next step would be to randomly sample a larger size of unbanked populations in more developing countries and mirror the same procedure but with banked individuals within a variety of first-world countries. Also, observing the long-term effects of being unbanked in developing countries would be extremely interesting. For example, exploring how being unbanked affects retirement quality would be interesting to observe how the inability to access formal banking institutions restricts future planning.

Conclusion

This study explored how perceptions of banking institutions shape financial behaviors when comparing Los Angeles and Gujarat. This study is fascinating as it reveals how trust, or lack thereof, in financial institutions influences how individuals save, spend, and plan for their future. The results found that individuals in Los Angeles are more likely to use formal financial services such as savings accounts and formal loans. In contrast, participants in Gujarat often invest in physical assets and depend on familial networks. Due to their reliance on banks, Los Angeles surveyors found it easier to save, obtain a loan, and improve their financial state through hard work than the Gujarati surveyors.

Despite this study’s immense contributions, it still has several limitations. Weaknesses of this study include its limited sample size, geographic constraints, and potential selection bias from convenience sampling. These limitations reduce the generalizability of the findings. If this study had access to more time and funding, the next step would be to randomly sample a larger size of unbanked populations in more developing countries and mirror the same procedure but with banked individuals within a variety of first-world countries. Further study is warranted to confirm these results among broader populations globally to determine a difference in financial perceptions between unbanked and banked individuals. Future research should examine the long-term effects of financial literacy education in rural areas and see how those people interact with formal financial institutions. Additionally, future research should examine to what extent digital banking initiatives build trust and close the gap in financial access across varying communities.

In conclusion, this study highlighted the relationship between financial perception and economic behavior. It suggests policy efforts that address not just banking, but also public education, consumer protection, and widespread seminars in order to restore trust between the citizen and the bank, especially in developing areas. This research contributes to the field as it directly compares and contrasts two different locations with very different economic environments and how they interact with financial tools.

Appendix

References

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2007). The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.1.141 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Kranton, R. E. (1996). Reciprocal exchange: A self-sustaining system. The American Economic Review, 86(4), 830–851. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118307 [↩] [↩]

- Financial Conduct Authority. (2024). Exploring financial exclusion. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/external-research/exploring-financial-exclusion.pdf [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Beck, J. (2021). The need for financial inclusion in developing countries. ACI Worldwide. https://www.aciworldwide.com/blog/the-need-for-financial-inclusion-in-developing-countries [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- World Bank. (n.d.). Financial inclusion overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- World Bank. (n.d.). Financial inclusion overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview [↩]

- Misra, P., & Bhandari, M. (n.d.). All eyes on India’s biometric ID experiment. Pathways for Prosperity Commission. https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/blog/all-eyes-indias-biometric-id-experiment/ [↩]

- Cicchiello, A. F., Kazemi Khasraghi, A., Monferrá, S., & Girón, A. (2021). Financial inclusion and development in the least developed countries in Asia and Africa. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(49). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00190-4 [↩] [↩]

- Sanghera, T. (2019, June 21). Banking in India: Why many people still don’t use their accounts. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2019/6/21/banking-in-india-why-many-people-still-dont-use-their-accounts [↩]

- Grameen Bank. (n.d.). Introduction. https://grameenbank.org.bd/about/introduction [↩]