Abstract

Cortisol, a stress hormone, has been implicated in triggering inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema, highlighting a link between stress and dermatological health. This study investigates the correlation between eczema incidence rate and mental distress level in the Chinese adult population. Mental stress was evaluated using a composite score derived from survey responses addressing sleep, mood, diet, and coping behaviours, while eczema was assessed based on frequency and body areas affected. A cross-sectional analysis surveyed 162 participants, with findings indicating that those suffering from eczema reported significantly higher mental stress scores compared to non-eczema individuals (1.81 ± 1.62 vs. 0.95 ± 1.16, p = 0.0008). The results demonstrated a positive association between the frequency of eczema symptoms and elevated mental stress (β = 0.64, p = 0.0004). Factors such as sleep quality and dietary habits were identified as significant moderating influences, with poor sleep and unhealthy eating correlating with higher stress levels. While the findings align with existing research highlighting the psychosocial dimensions of eczema, contrary views exist regarding the interaction between mental health and eczema severity. Limitations including sample size and reliance on self-reported data must be acknowledged. This research contributes to understanding the intricate relationship between psychological well-being and dermatological conditions, advocating for integrated treatment strategies that address both mental and physical health to improve the quality of life for individuals with eczema.

Keywords: Eczema, Mental Distress, Inflammation, Cross-Sectional Study, Skin Diseases, Hierarchical Linear Regression Model (HLR)

Introduction

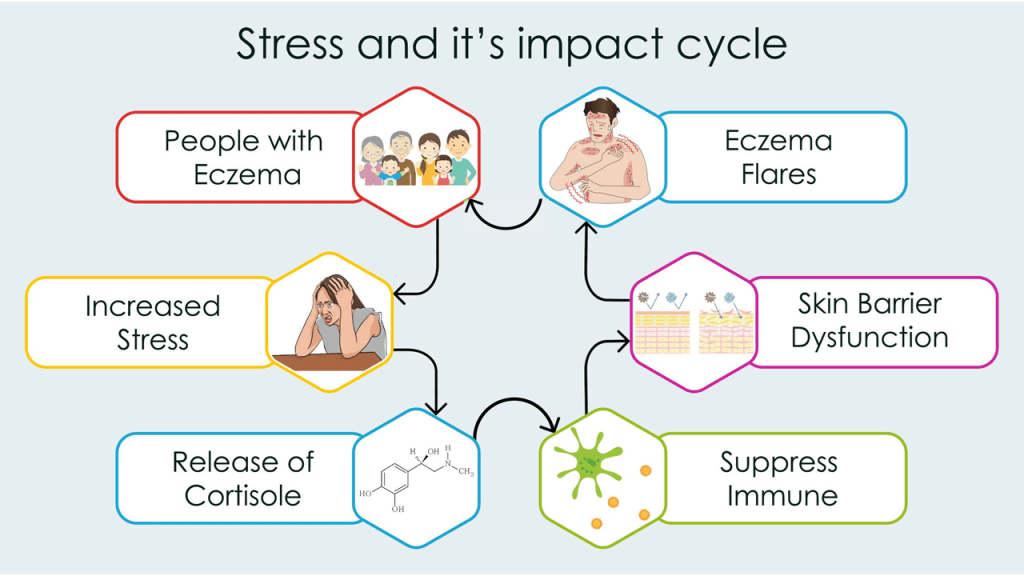

Eczema, or atopic dermatitis, affects approximately 15-20% of children and 1-3% of adults worldwide, leading to significant health care costs and economic burdens, including loss of productivity1. This chronic inflammatory skin condition can be triggered by various factors, including environmental allergens, chemicals, and mental stress. Previous studies have shown that mental stress has a scientific link to impacting the human immune system and causing inflammatory conditions2. The stress hormones, like cortisol, are released during all kinds of acute or chronic stress conditions. Cortisol is known to suppress the immune system and increase inflammation throughout the body, including the skin3. Eczema happens to be a skin inflammatory condition which may be triggered or exacerbated in the presence of different levels of mental distress, such as anxiety and depression4. The stress and eczema exacerbation cycle would spiral into a loophole, causing people with eczema to experience further stress, leading to more severe eczema flare-up. Multiple studies demonstrate stress-induced immune dysregulation can worsen skin conditions. However, research findings specifically addressing the correlation and triggering effect of mental stress on eczema are relatively scarce and controversial. The general conception of eczema being a non-severe or life-threatening condition has resulted in limited attention in its medical research. This highlights the importance of exploring how mental health may influence the prevalence and severity of eczema among adults.

Eczema is a term that encompasses various inflammatory skin conditions, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and allergic eczema. While most eczema cases, including typical forms like atopic dermatitis, are triggered by external factors such as allergens or chemicals and are not considered autoimmune diseases, certain eczema-like skin manifestations can be associated with autoimmune conditions. According to Baum et al.5, these autoimmune blistering diseases can lead to various skin manifestations, including eczema-like symptoms, due to immune dysregulation. The immune response against the body’s own tissues often results in skin-related diseases, highlighting the complex interplay between the immune system and skin health.The correlation between mental distress and immune response has acquired considerable attention. Segerstrom and Miller6 conducted a meta-analysis that demonstrated how psychological stress influences immune function, indicating that heightened stress levels can lead to immune dysregulation. This weakened immune response not only exacerbates existing conditions but may also predispose individuals to skin conditions like eczema. The psychosocial implications of skin diseases are profound, with Yew et al.7 emphasizing that patients with eczema experience increased mental distress, including anxiety and depression. These findings suggest a cyclical relationship where mental distress exacerbates skin conditions, which in turn may lead to heightened stress.

The relationship between mental health and skin diseases, notably eczema, remains an area of controversy and ongoing research. Rønnstad et al.8 provided a systematic review indicating a significant association between atopic dermatitis and emotional distress, supporting the notion that skin conditions can affect psychological well-being. However, there are studies that highlight the complexity of this relationship, suggesting that while some individuals experience clear correlations between their mental distress and eczema symptoms, others do not exhibit such patterns, indicating that further research is required to elucidate these differences9. However, these associations do not imply causation, and variability in response may be influenced by psychological, genetic, or environmental moderators. This suggests that although the correlation exists, individual experiences and responses to mental distress can vary significantly, emphasizing a need for deeper exploration into the factors that mediate these interactions.

Figure 1 illustrates the cyclical relationship between stress and eczema, emphasizing a negative feedback loop. Stress is presented as a key trigger that can induce or worsen eczema symptoms, such as itching, inflammation, and skin irritation. These physical manifestations of eczema, in turn, lead to heightened stress, anxiety, and emotional distress. This consequently perpetuates the cycle, as the increased stress further exacerbates the eczema, creating a challenging and recurring pattern for individuals experiencing these conditions.

This study aims to investigate whether there is a correlation between mental distress and eczema severity by analysing participants’ stress levels and the self-reported severity of their eczema symptoms. By doing so, this research seeks to confirm the link between psychological factors and eczema by using a composite score derived from survey responses on lifestyle and behavioral factors to quantify mental stress, contributing to a better understanding of this common condition and its trigger-factor management.

Results

Participant Characteristic

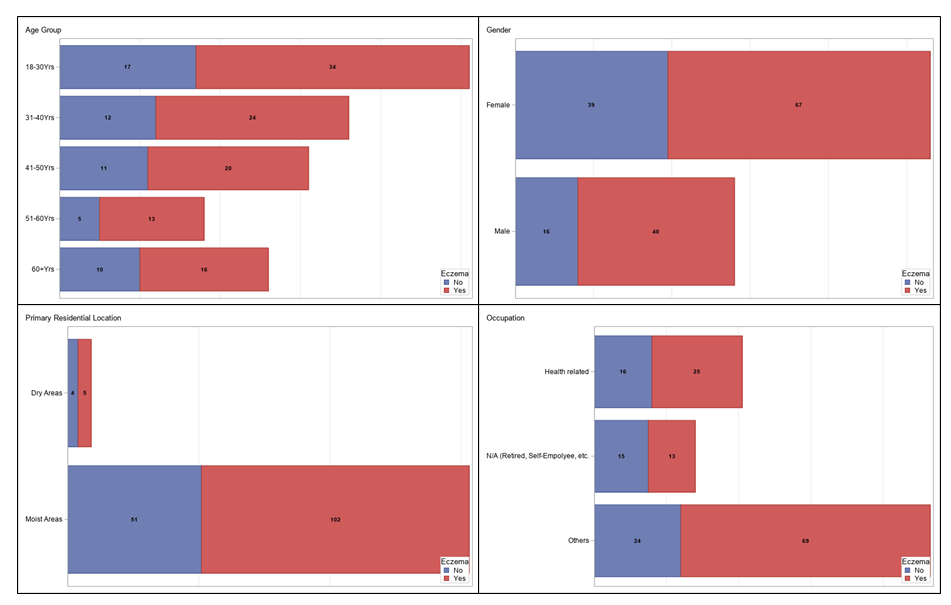

Baseline demographic and lifestyle factors stratified by eczema status are presented in Table 1. Among the 162 participants, 107 (66%) had eczema, and 55 (34%) reported no history of eczema. Gender composition showed a higher proportion of females in both groups (62.6% in the eczema group and 70.9% in the non-eczema group, p = 0.2933). The age distribution was similar, with the largest group aged 18-30 years (31.8% with eczema vs. 30.9% without eczema, p = 0.9643). However, statistically significant differences emerged in occupation, where participants without eczema were more likely to be retired or self-employed (27.3% vs. 12.2%, p = 0.0181).

Participants with eczema reported shorter sleep durations, with 50.9% of non-eczema participants sleeping more than 7 hours compared to 26.2% in the eczema group (p = 0.0155). Additionally, eczema participants were less likely to engage in regular exercise (15% reported no exercise vs. 1.8% of non-eczema participants, p = 0.0351).

| Overall | Eczema | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | n = 162 | Yes, n = 107 | No, n = 55 | |

| Age Group, N (%) | ||||

| 18 — 30 Yrs | 51 | 34 (31.8%) | 17 (30.9%) | 0.9643 |

| 31 — 40 Yrs | 36 | 24 (22.4%) | 12 (21.8%) | |

| 41 — 50 Yrs | 31 | 20 (18.7%) | 11 (20%) | |

| 51 — 60 Yrs | 18 | 13 (12.2%) | 5 (9.1%) | |

| 60+ Yrs | 26 | 16 (15%) | 10 (18.2%) | |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||

| Male | 56 | 40 (37.4%) | 16 (29.1%) | 0.2933 |

| Female | 106 | 67 (62.6%) | 39 (70.9%) | |

| Primary Residential Location, N (%) | ||||

| Dry areas | 9 | 5 (4.7%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0.4939 |

| Moist areas | 153 | 102 (95.3%) | 51 (92.7%) | |

| Occupation, N (%) | ||||

| N/A (Retired, Self-Employee, etc.) | 28 | 13 (12.2%) | 15 (27.3%) | 0.0181 |

| Others | 93 | 69 (64.5%) | 24 (43.6%) | |

| Health related | 41 | 25 (23.4%) | 16 (29.1%) | |

| Work Hours, N (%) | ||||

| 0 — 30 Hrs | 53 | 30 (28%) | 23 (41.8%) | 0.0946 |

| 31 — 50 Hrs | 74 | 53 (49.5%) | 21 (38.2%) | |

| 51 — 70 Hrs | 26 | 20 (18.7%) | 6 (10.9%) | |

| >70 Hrs | 9 | 4 (3.7%) | 5 (9.1%) | |

| Sleep Hours, N (%) | ||||

| 7+ Hrs | 56 | 28 (26.2%) | 28 (50.9%) | 0.0155 |

| 6 — 7 Hrs | 64 | 46 (43%) | 18 (32.7%) | |

| 5 — 6 Hrs | 34 | 27 (25.2%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| 4 — 5 Hrs | 8 | 6 (5.6%) | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Regular Sleep Patterns, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 29 | 20 (18.7%) | 9 (16.4%) | 0.7144 |

| No | 133 | 87 (81.3%) | 46 (83.6%) | |

| Sleep Feeling, N (%) | ||||

| Recharged and Energetic | 136 | 88 (82.2%) | 48 (87.3%) | 0.6526 |

| Tiring and Drained | 13 | 9 (8.4%) | 4 (7.3%) | |

| Chronic Fatigue | 13 | 10 (9.4%) | 3 (5.5%) | |

| Sport / Exercise Hours, N (%) | ||||

| 2+ Hrs | 82 | 51 (47.7%) | 31 (56.4%) | 0.0351 |

| 1–2 Hrs | 63 | 40 (37.4%) | 23 (41.8%) | |

| No Sport / Exercise | 17 | 16 (15%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Mental Stress Experience, N (%) | ||||

| Panic attack | 4 | 4 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.1465 |

| Nervousness and worrying | 31 | 22 (20.6%) | 9 (16.4%) | 0.5202 |

| Anxious, or feeling on edge | 27 | 24 (22.4%) | 3 (5.5%) | 0.0060 |

| Trouble relaxing | 24 | 20 (18.7%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0.0527 |

| Feeling annoyed or irritable | 15 | 10 (9.4%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.9577 |

| Lack of interests in things | 27 | 25 (23.4%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.0014 |

| Mood swing | 29 | 21 (19.6%) | 8 (14.6%) | 0.4244 |

| Insomnia or lengthened Sleep | 16 | 10 (9.4%) | 6 (10.9%) | 0.7521 |

| Stress eating or lack of appetite | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.4720 |

| Mental exhaustion/Burnout | 31 | 24 (22.4%) | 7 (12.7%) | 0.1371 |

| Lack of motivation and procrastination | 36 | 29 (27.1%) | 7 (12.7%) | 0.0372 |

| Cut-off of normal social connections | 5 | 4 (3.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.5034 |

| Mental Stress Composite Score, MEAN (STD) | 1.52 (1.53) | 1.81 (1.62) | 0.95 (1.16) | 0.0008 |

| Dietary Habit, N (%) | ||||

| Adaptive | 95 | 58 (54.2%) | 37 (67.3%) | 0.1098 |

| Poor appetite | 4 | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.7019 |

| Vegetarian | 7 | 5 (4.7%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.7586 |

| Flexitarian | 11 | 9 (8.4%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.2526 |

| Low sodium | 9 | 6 (5.6%) | 3 (5.5%) | 0.9679 |

| Salty foods | 19 | 14 (13.1%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.4545 |

| Sea foods | 15 | 10 (9.4%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.9577 |

| Meat-based dietary | 32 | 26 (24.3%) | 6 (10.9%) | 0.0427 |

| Spicy/chill foods | 17 | 12 (11.2%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.6762 |

| High-carbohydrates | 14 | 10 (9.4%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0.6565 |

| Fast foods | 12 | 7 (6.5%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.5575 |

| Other Life Activities, N (%) | ||||

| Tobacco consumption | 13 | 9 (8.4%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0.8006 |

| Alcohol consumption | 14 | 11 (10.3%) | 3 (5.5%) | 0.3006 |

| Caffeine consumption | 60 | 47 (43.9%) | 13 (23.6%) | 0.0113 |

| Irritating foods consumption | 30 | 26 (24.3%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0.0082 |

| Frequent use of cosmetics | 23 | 13 (12.2%) | 10 (18.2%) | 0.2976 |

| Frequent sugary beverage | 26 | 21 (19.6%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0.0836 |

| Stress-eating | 16 | 14 (13.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.0563 |

| Release Stress, N (%) | ||||

| Food intake | 45 | 34 (31.8%) | 11 (20%) | 0.1131 |

| Sports and exercise | 59 | 36 (33.6%) | 23 (41.8%) | 0.3060 |

| Shopping | 34 | 24 (22.4%) | 10 (18.2%) | 0.5295 |

| Music or arts | 37 | 23 (21.5%) | 14 (25.5%) | 0.5697 |

| Social activities | 43 | 27 (25.2%) | 16 (29.1%) | 0.5985 |

| Drinking alcohol | 6 | 5 (4.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.3623 |

| Use of tobacco | 6 | 5 (4.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.3623 |

| Watching TV or Movies | 46 | 31 (29%) | 15 (27.3%) | 0.8203 |

| Relaxing at home | 80 | 61 (57%) | 19 (34.6%) | 0.0068 |

| Others | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.4720 |

Note:

Yrs – Years; Hrs – Hours; STD – Standard Deviation.

Chi-Square / Fisher Exact tests were conducted to test the statistical significance of the difference between with and without Eczema for different parameters.

Bolded P value indicates statistically significant difference at 95% confidence interval.

Outcome Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 details the descriptive statistics for participants with eczema. Among those with eczema (n=107), 41.1% reported eczema rarely; 47.7% occasionally; 6.5% frequently; 2.8% very frequently; and 1.9% all the time. The most common body parts affected by eczema were fingers (26.2%), feet (21.5%), upper limbs (16.8%), and lower limbs (17.8%).

| Eczema, n = 107 | |

|---|---|

| Eczema Frequency, N (%) | |

| Rarely | 44 (41.1%) |

| Occasionally | 51 (47.7%) |

| Frequent | 7 (6.5%) |

| Very frequent | 3 (2.8%) |

| All the time | 2 (1.9%) |

| Body Part of Eczema, N (%) | |

| Fingers | 28 (26.2%) |

| Feet | 23 (21.5%) |

| Upper limbs | 18 (16.8%) |

| Lower limbs | 19 (17.8%) |

| Scalp | 4 (3.7%) |

| Face | 9 (8.4%) |

| Torso | 17 (15.9%) |

| Private parts | 5 (4.7%) |

| Under folded skin | 8 (7.5%) |

| Others | 5 (4.7%) |

Primary Hypothesis

Table 3 presents the results of a hierarchical logistic regression analysis that tests whether the mental stress composite score (the predictor) is associated with the likelihood of having eczema (the outcome).”. In Model I, mental stress significantly predicted eczema (OR=1.58, 95% CI: 1.22-2.11, p=0.0011). After adjusting for baseline variables in Model II, mental stress remained a significant predictor (OR=1.47, 95% CI: 1.09-2.06, p=0.0157). In the full model (Model III), which included mental stress, baseline variables, and other covariates, mental stress continued to significantly predict eczema (OR=1.85, 95% CI: 1.22-2.98, p=0.0064). Several other factors in Model III also showed significant associations with eczema, including occupation, sleep hours, sport/exercise hours, dietary habits, irritating food consumption, frequent use of cosmetics and high-carbohydrate intake.

| Parameter | MODEL I | MODEL II | MODEL III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Mental Stress | 1.58 (1.22-2.11) | 0.0011 | 1.47 (1.09-2.06) | 0.0157 | 1.85 (1.22-2.98) | 0.0064 |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18 – 30 Yrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| 31 – 40 Yrs | – | – | 0.95 (0.26-3.37) | 0.9397 | 1.26 (0.19-8.32) | 0.8081 |

| 41 – 50 Yrs | – | – | 0.48 (0.11-1.91) | 0.3030 | 0.32 (0.04-2.47) | 0.2830 |

| 51 – 60 Yrs | – | – | 0.91 (0.17-4.9) | 0.9087 | 2.25 (0.18-31.07) | 0.5297 |

| 60+ Yrs | – | – | 0.81 (0.18-3.49) | 0.7758 | 2.55 (0.33-21.94) | 0.3772 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||||

| Male | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Female | – | – | 0.72 (0.3-1.69) | 0.4527 | 0.92 (0.25-3.37) | 0.8968 |

| Primary Residential Location, N (%) | ||||||

| Dry areas | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Moist areas | – | – | 1.19 (0.21-6.47) | 0.8387 | 2.17 (0.22-19.78) | 0.4924 |

| Occupation, N (%) | ||||||

| N/A (Retired, Self-Employee, etc.) | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Others | – | – | 3.64 (1.2-11.8) | 0.0253 | 4.05 (0.96-19.29) | 0.0645 |

| Health related | – | – | 1.32 (0.35-5.08) | 0.6820 | 1.43 (0.24-8.86) | 0.6969 |

| Work Hours, N (%) | ||||||

| 0 – 30 Hrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| 31 – 50 Hrs | – | – | 1.5 (0.6-3.81) | 0.3856 | 3.49 (0.92-15.05) | 0.0751 |

| 51 – 70 Hrs | – | – | 1.84 (0.52-7.06) | 0.3547 | 6.98 (1.14-53.71) | 0.0456 |

| >70 Hrs | – | – | 0.36 (0.06-2) | 0.2515 | 0.22 (0.02-1.97) | 0.1963 |

| Sleep Hours, N (%) | ||||||

| 4 – 5 Hrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| 5 – 6 Hrs | – | – | 3.23 (1.37-7.95) | 0.0085 | 8.9 (2.53-37.03) | 0.0013 |

| 6 – 7 Hrs | – | – | 3.83 (1.23-13.31) | 0.0256 | 5.41 (1.16-29.51) | 0.0386 |

| 7+ Hrs | – | – | 7.2 (1.11-65.06) | 0.0495 | 15.75 (1.46-252.12) | 0.0318 |

| Regular Sleep Patterns, N (%) | ||||||

| No | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | – | – | 1.14 (0.4-3.46) | 0.8104 | 0.73 (0.14-3.67) | 0.7002 |

| Sport / Exercise Hours, N (%) | ||||||

| No Sport / Exercise | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| 1-2 Hrs | – | – | – | – | 0.99 (0.28-3.45) | 0.9817 |

| 2+ Hrs | – | – | – | – | 94.42 (6.74-3478.12) | 0.0030 |

| Dietary Habit | ||||||

| Adaptive | – | – | – | – | 1.01 (0.27-3.9) | 0.9914 |

| Poor appetite | – | – | – | – | 1.18 (0.03-60.27) | 0.9273 |

| Vegetarian | – | – | – | – | 1.22 (0.1-18.76) | 0.8786 |

| Flexitarian | – | – | – | – | 16.23 (1.25-292.4) | 0.0408 |

| Low sodium | – | – | – | – | 2.06 (0.23-20.37) | 0.5196 |

| Salty foods | – | – | – | – | 2.71 (0.45-19.73) | 0.2951 |

| Sea foods | – | – | – | – | 0.75 (0.11-5.57) | 0.7725 |

| Meat-based dietary | – | – | – | – | 6.73 (1.23-44.24) | 0.0340 |

| Spicy/chill foods | – | – | – | – | 1.27 (0.14-11.49) | 0.8271 |

| High-carbohydrates | – | – | – | – | 0.06 (0.01-0.55) | 0.0137 |

| Fast foods | – | – | – | – | 0.05 (0-0.48) | 0.0121 |

| Other Life Activities | ||||||

| Tobacco consumption | – | – | – | – | 0.59 (0.06-5.78) | 0.6510 |

| Alcohol consumption | – | – | – | – | 2.73 (0.38-23.8) | 0.3286 |

| Caffeine consumption | – | – | – | – | 3.42 (0.98-13.47) | 0.0627 |

| Irritating foods consumption | – | – | – | – | 8.07 (1.29-72.02) | 0.0389 |

| Frequent use of cosmetics | – | – | – | – | 0.05 (0.01-0.28) | 0.0014 |

| Frequent sugary beverage | – | – | – | – | 1.5 (0.3-8.18) | 0.6286 |

| Stress-eating | – | – | – | – | 4.21 (0.3-116.44) | 0.3415 |

Note:

Yrs – Years; Hrs – Hours; OR – Odds Ratio; CI – Confidence Interval.

HLRs (Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model) were conducted to check effects from the primary predictor of eczema and different covariates.

Bolded P value indicates statistically significant difference at 95% confidence interval.

Secondary Hypothesis

Table 4 shows the estimates of eczema level from a linear regression analysis, predicted by the mental stress composite score for participants with eczema. For the purpose of the linear regression analysis presented in Table 4, the categorical frequency of eczema symptoms was converted into a numerical Eczema Level on a 5-point ordinal scale: ‘Rarely’ was coded as 1, ‘Occasionally’ as 2, ‘Frequent’ as 3, ‘Very frequent’ as 4, and ‘All the time’ as 5. This quantitative variable served as the dependent variable in the regression models. In Model I, mental stress significantly predicted eczema level (Estimate=0.27, STD=0.05, p<0.0001). This effect remained significant after adjusting for baseline variables in Model II (Estimate=0.24, STD=0.06, p<0.0001) and other covariates in Model III (Estimate=0.23, STD=0.07, p=0.0007). However, when body part of eczema was added to the model (Model IV), mental stress was not a significant predictor of eczema level (Estimate = 0.06, STD = 0.06, p=0.3213). In Model IV, the body part affected by eczema was a significant predictor of eczema level. This suggests that the specific body part affected by eczema may be a stronger predictor of perceived eczema severity than the composite stress score, or that it may act as a mediating factor in the relationship between stress and symptom severity.

| Parameter | MODEL I | MODEL II | MODEL III | MODEL IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST ± STD | P Value | EST ± STD | P Value | EST ± STD | P Value | EST ± STD | P Value | |

| Mental Stress | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.0000 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.0000 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.0007 | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.3213 |

| Age Group | ||||||||

| 18 – 30 Yrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | . |

| 31 – 40 Yrs | – | – | -0.24 ± 0.25 | 0.3308 | -0.12 ± 0.28 | 0.6780 | -0.13 ± 0.24 | 0.5765 |

| 41 – 50 Yrs | – | – | -0.41 ± 0.28 | 0.1444 | -0.34 ± 0.29 | 0.2452 | -0.19 ± 0.25 | 0.4449 |

| 51 – 60 Yrs | – | – | -0.4 ± 0.32 | 0.2089 | -0.36 ± 0.36 | 0.3195 | -0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.1803 |

| 60+ Yrs | – | – | 0.02 ± 0.3 | 0.9416 | 0.27 ± 0.33 | 0.4085 | -0.07 ± 0.28 | 0.8114 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||||||

| Male | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | . |

| Female | – | – | -0.13 ± 0.18 | 0.4802 | -0.14 ± 0.22 | 0.5176 | -0.14 ± 0.19 | 0.4644 |

| Primary Residential Location, N (%) | ||||||||

| Dry areas | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | . |

| Moist areas | – | – | 0.42 ± 0.35 | 0.2345 | 0.48 ± 0.38 | 0.2094 | 0.5 ± 0.31 | 0.1065 |

| Occupation, N (%) | ||||||||

| N/A (Retired, Self-Employee, etc.) | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | . |

| Others | – | – | 0.59 ± 0.24 | 0.0129 | 0.62 ± 0.26 | 0.0180 | 0.34 ± 0.21 | 0.1066 |

| Health related | – | – | 0.05 ± 0.28 | 0.8696 | 0.12 ± 0.3 | 0.6778 | -0.15 ± 0.25 | 0.5391 |

| Work Hours, N (%) | ||||||||

| 0 – 30 Hrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | . |

| 31 – 50 Hrs | – | – | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.3170 | 0.16 ± 0.21 | 0.4443 | 0.04 ± 0.17 | 0.8119 |

| 51 – 70 Hrs | – | – | 0.14 ± 0.26 | 0.5945 | 0.1 ± 0.29 | 0.7195 | -0.11 ± 0.24 | 0.6524 |

| >70 Hrs | – | – | -0.3 ± 0.37 | 0.4192 | -0.45 ± 0.39 | 0.2574 | -0.76 ± 0.33 | 0.0216 |

| Sleep Hours, N (%) | ||||||||

| 4 – 5 Hrs | – | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | . |

| 5 – 6 Hrs | – | – | 0.3 ± 0.18 | 0.1056 | 0.37 ± 0.21 | 0.0746 | 0.09 ± 0.18 | 0.6088 |

| 6 – 7 Hrs | – | – | 0.38 ± 0.23 | 0.0958 | 0.33 ± 0.25 | 0.1805 | 0.26 ± 0.21 | 0.2221 |

| 7+ Hrs | – | – | 0.15 ± 0.39 | 0.6934 | 0.13 ± 0.42 | 0.7609 | -0.13 ± 0.34 | 0.6998 |

| Body Part of Eczema | ||||||||

| Fingers | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.15 ± 0.19 | <.0001 |

| Feet | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.75 ± 0.21 | 0.0005 |

| Upper limbs | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.19 ± 0.24 | 0.4134 |

| Lower limbs | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 ± 0.22 | <.0001 |

| Scalp | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.97 ± 0.48 | 0.0471 |

| Face | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.76 ± 0.33 | 0.0224 |

| Torso | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.64 ± 0.24 | 0.0099 |

| Private parts | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.4 ± 0.43 | 0.0016 |

| Under folded skin | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.78 ± 0.34 | 0.0256 |

| Others | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.53 ± 0.43 | 0.2195 |

Covariate effects

Sleep quality was a significant moderating factor. Participants who reported feeling recharged after sleep had lower stress scores (β = -1.43, p = 0.0008). Conversely, stress-eating behaviors were associated with significantly higher stress scores (β = 1.75, p = 0.0002). Dietary factors also played a role; frequent consumption of irritating foods was linked to elevated stress (β = 0.28, p = 0.0082).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses revealed gender differences in stress levels, with females reporting slightly higher scores than males, though this interaction was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Age appeared to moderate the relationship between eczema severity and stress, as younger individuals showed a stronger correlation. Excluding participants with comorbid mental health conditions did not alter the findings. Alternative model specifications, such as categorical stress outcomes, supported the robustness of the primary and secondary hypotheses.

Discussion

The findings of this research revealed notable trends that illustrate the complex interplay between eczema and mental distress in the adult population of China. The data indicated that individuals suffering from eczema reported significantly higher levels of mental stress compared to those without the condition. Furthermore, the severity of eczema symptoms was positively correlated with increased mental distress, particularly among younger participants aged 18-30. These findings reinforce the association between mental distress and inflammatory skin conditions, a relationship that has been evidenced in previous studies.

Previous research has shown similar trends. For example, Arndt et al.4 emphasized that stress is associated with worsened eczema symptoms, though causality cannot be confirmed from this study. Furthermore, Segerstrom and Miller6 conducted a meta-analysis affirming that psychological stress negatively impacts immune function, thus potentially intensifying eczema symptoms due to immune dysregulation. These studies further substantiate the current findings, affirming that the stress-eczema connection is worth further investigation.

Contrastingly, other research presents opposing perspectives. Talamonti et al.10 found no significant correlations between the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores and psychological parameters, highlighting that some patients do not experience a direct interaction between their mental health and eczema severity. Similarly, Schönmann et al.11 noted that while there is an association between atopic eczema and mental health disorders, the nature of this connection remains unclear, indicating that other mediating variables could influence the observed relationships. These discrepancies likely stem from diverse methodological approaches; for instance, studies using observational clinical measures like the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) may yield different results than those that, like the present study, rely on self-reported symptom frequency and a composite score for mental stress. Additionally, cultural factors can significantly influence how individuals perceive and report mental distress, which may contribute to variability in findings across different populations..

The positive correlation found in this study between mental stress and eczema severity is supported by the principles of psychoneuroimmunology. This field explains how psychological stress can alter immune responses and increase systemic inflammation, as noted in studies by Gouin and Kiecolt-Glaser12. This provides a plausible biological pathway for our findings, whereby the heightened mental distress reported by participants may lead to the exacerbated inflammatory symptoms of eczema via the release of stress hormones like cortisol.

Beyond individual clinical practice, these findings have implications for broader healthcare policy and systems. For instance, healthcare systems could work to integrate mental health screenings as a standard component of dermatological consultations for patients with chronic inflammatory conditions like eczema. From a policy perspective, insurance frameworks could be revised to better support and reimburse for integrated care models, ensuring that patients have access to both dermatological and psychological treatments. Finally, these insights could be incorporated into medical education curricula to ensure future clinicians are better equipped to manage the complex interplay between physical and mental health in dermatological practice

The results of this study should be interpreted with the context of notable limitations. The sample size of 162 participants may limit the generalizability of the results beyond the studied cohort. Moreover, the singularity of the sample’s racial composition (Asian) raises concerns regarding the applicability of the findings to diverse populations. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may compromise the authenticity of participants’ mental and medical conditions, as individuals often misinterpret or underreport their experiences. Furthermore, this study utilized a composite score for mental stress derived from various lifestyle and behavioral questions rather than a clinically validated and standardized instrument, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). This non-standardized method, while based on factors linked to stress, may not capture the full clinical spectrum of anxiety and depression and introduces a risk of measurement bias, as its validity and reliability have not been formally established Finally, a significant limitation is the definition of eczema status, which combined participants with active, current eczema and those with only a past history of the condition. Analyzing these clinically distinct groups as a single category may obscure the specific relationship between current mental distress and active eczema symptoms. Future research should analyze these populations separately to provide a more nuanced understanding of this correlation. Additionally, the analysis did not account for several potential confounding variables, most notably medication use (e.g., corticosteroids, antihistamines) and a formal history of atopy, which could independently influence both eczema severity and mental state. Future studies should collect data on these variables to conduct a more robust analysis.

To enhance the reliability of future research, some improvements could be implemented. Increasing the sample size and ensuring diversity in race and socioeconomic status can provide a more representative understanding of the eczema-mental distress relationship across populations. Moreover, employing validated instruments for measuring both eczema severity and mental health status may yield more reliable data. Investigating the potential mediating factors, such as coping strategies and social support systems, could deepen the understanding of the relationship between mental distress and eczema. For example, a future longitudinal study could assess whether patients who utilize adaptive coping strategies, such as exercise, show a weaker stress-eczema correlation than those who use maladaptive strategies, like stress-eating.

This study highlights a significant correlation between eczema severity and mental distress among the adult population in China, emphasizing the importance of considering psychological factors in the management of this skin condition. “This research contributes to the growing evidence of a complex, likely bidirectional relationship between mental and dermatological health; while this study focused on stress as a predictor, it is equally plausible that the burden of severe eczema leads to increased mental distress, underscoring the need for interconnected treatment. As the interplay between mental distress and immune function becomes more evident, future investigations should aim to uncover the underlying mechanisms and explore potential approaches that may decrease the psychological burden associated with eczema. By gaining a more comprehensive understanding of these interactions, healthcare providers can enhance care strategies, ultimately improving the quality of life for individuals affected by eczema and similar conditions.

Future research should also explore the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the observed relationship between mental distress and eczema, particularly focusing on the role of immune dysregulation and psychosocial factors. Expanding the inquiry into other skin conditions and their correlated mental health effects could yield further valuable insights into the broader context of dermatological health and psychological well-being.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study confirmed a significant positive association between mental distress and both the presence and severity of eczema in the adult Chinese population. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the psychodermatological link, highlighting that psychological well-being is intrinsically connected to dermatological health. Therefore, a key recommendation for clinicians is to adopt an integrated care model that goes beyond pharmacological treatments by educating patients on the impact of stress and proactively incorporating psychological support, such as stress-management techniques or counseling, directly into dermatological practice to improve overall patient quality of life

Methods

Study Design

The study was a cross-sectional analysis based on a structured survey designed to evaluate the correlation between eczema severity and mental distress among a sample of Chinese adults. The initial recruitment included 204 participants, with 42 excluded due to incomplete responses, resulting in a final study population of 162 individuals (all aged >18, 56 males, 106 females). Participants were recruited through an online platform and local outreach at Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital, using a convenience sampling method. 42 responses were excluded due to incomplete survey responses, often stemming from skipped demographic or mental health sections, which may introduce bias. Incomplete data were excluded listwise from analyses.” Data collection focused on demographic information, lifestyle habits, dietary patterns, eczema diagnosis and severity, and mental stress assessment, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Survey Parameters

Eczema status was defined as: Yes – currently experiencing eczema or previously experienced eczema, vs. No – never experienced eczema. Eczema severity among affected participants was determined using questions 4, 21, 22, and 23. Question 4 identified eczema and other inflammatory skin conditions, emphasizing the importance of historical and symptomatic diagnosis. Question 21 discerned participants currently experiencing or previously having experienced eczema, which aligns with criteria used in dermatological research such as the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI). Questions 22 and 23 assessed frequency and body areas affected, respectively, facilitating a severity index that highlighted body site and frequency as critical severity indicators13.

The severity of mental distress was measured through various dimensions, starting with work-related factors. Question 6 analyzed occupational categories, showing that individuals in health-related fields or those currently employed14, endure more substantial mental strain compared to unemployed or retired individuals. Question 7, addressing work hours, is supported by the meta-analysis by Virtanen et al.15, which links extended work hours to increased probability of experiencing depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Questions 8 and 9 gathered data on diagnosed or perceived mental health conditions. Prins et al.16 documented that self-reported mental health assessments can reveal under-recognized stress indicators, supporting the questions related to undiagnosed conditions. Questions 10, 11, and 12 covered sleep patterns. Research of Baglioni et al.17 indicates that reduced sleep duration, irregular sleep, and feeling exhausted after sleep correlate strongly with heightened mental distress.

Dietary habits (question 13) were classified into unhealthy and normal categories. Studies, such as those by Jacka et al.18, demonstrate associations between poor dietary choices (e.g., high in processed foods and sugars) and increased mental health symptoms. Questions 14 and 15 targeted lifestyle practices that often coincide with higher stress levels. Schmitz et al.19 discuss how activities like tobacco and alcohol consumption are frequently utilized maladaptive coping strategies under stress.

Question 16 focused on recreational engagement, where lower participation rates relate directly to increased stress, consistent with findings from Cuijpers et al.20, showing that social and recreational engagements are protective factors against depression. Question 18 highlighted loss of interest, a significant depressive symptom as delineated in the DSM-521 and similarly addressed in the PHQ-922.

Finally, questions 19 and 20 explored how mental distress manifests and measures adopted to relieve stress. As Cohen et al.23 suggest, the absence of stress-reducing activities or reliance on maladaptive strategies like overeating or substance use correlates with higher psychological distress.

The composite mental stress score was computed as a sum of binary indicators across twelve stress-related symptoms with weighted equally. Covariates were collected through self-reported questionnaires and verified against medical records where applicable. All quantitative and qualitative data were assigned with a range of scores (from 0 to 1) for statistical analysis.

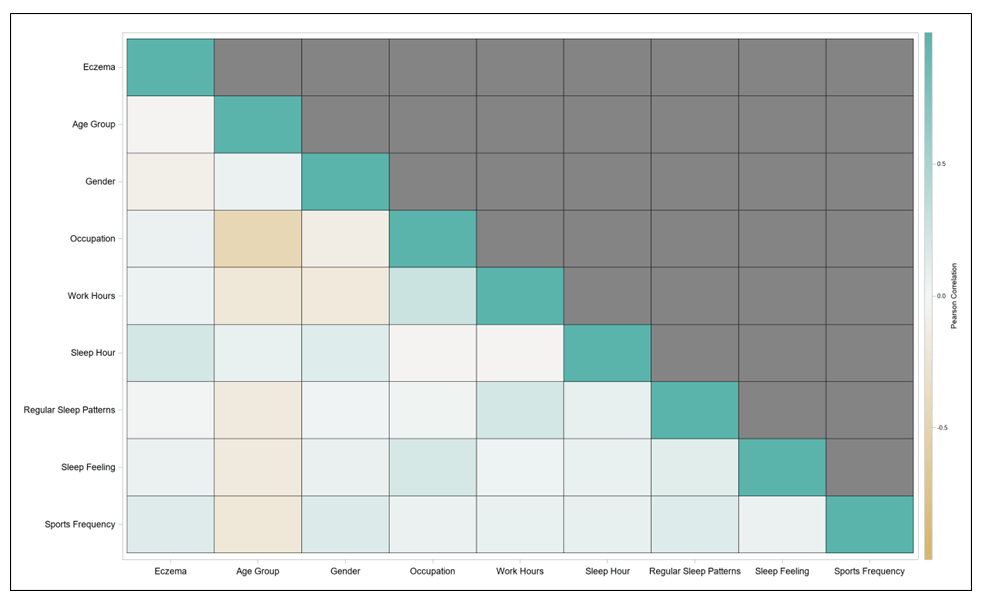

Correlation Analysis

A correlation analysis was conducted among parameters of eczema status and participant`s baseline information. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to access the analysis, and the results were presented as the heat map in Figure.4. high correlations (above 0.75) were not found between any variables, which was as expected for the statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, stratified by eczema status. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Chi-Square / Fisher Exact tests were conducted to test the statistical significance of the difference between participants with and without eczema for different parameters. P-values were calculated at a 95% confidence interval to indicate the statistical significance.

HLR (Hierarchical Linear Regression Models) were conducted to determine the independent variables (i.e., binary variables of Eczema status) can explain a statistically significant amount of variance in the dependent variables of the mental stress composite score after accounting for other variables and identified how much the effect varied by the level of significance. HLR is a framework for model comparison that involves building multiple regression models by adding variables to a previous model at each step. Three models were included for each outcome: level 1 control (Eczema status only), level 2 control (Eczema status + Baseline Information) and level 3 control (Eczema status + Baseline Information, and Other Covariates).

Given the participants with specific characteristics and conditions of Eczema, the study expected to see the predicted mental stress outcomes. Therefore, the HLR captured the average effect from the different factors on this prediction, i.e., whether the variable effect would reduce or increase the prediction of outcomes. In addition, the strength of the effect from each of the variables was evaluated through the statistical test significance, i.e., p-value, at a 95% confidence interval. All the statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4, with a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

For the purposes of the hierarchical regression models, variables were grouped into two categories for sequential adjustment. Baseline Information, controlled for in Model II, included demographic and primary lifestyle factors: Age Group, Gender, Primary Residential Location, Occupation, Work Hours, Sleep Hours, Regular Sleep Patterns, and Sleep Feeling. Other Covariates, added in Model III, included additional behavioral and consumption habits: Sport/Exercise Hours, Dietary Habit, and Other Life Activities (such as tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine consumption)”

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to the administration and staff of Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital for their invaluable support in facilitating the distribution and collection of survey responses. We especially thank the participants who voluntarily contributed their time and personal experiences to this research. Their openness and cooperation were essential to the success of this study. We also acknowledge the efforts of the hospital’s ethics oversight and administrative review teams for ensuring that the research met all necessary ethical standards. This study would not have been possible without the collaborative effort of everyone involved. We are truly grateful for the contributions that helped bring this research to fruition.

References

- S. M. Langan, A. D. Irvine, S. Weidinger, Atopic dermatitis. The Lancet, 396, 345–360 (2020). [↩]

- M. Ravi, A. H. Miller, V. Michopoulos, The immunology of stress and the impact of inflammation on the brain and behaviour. BJPsych Advances, 27, 158–165 (2021). [↩]

- L. Thau, J. Gandhi, S. Sharma, Physiology, cortisol. StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing (2023). [↩]

- J. Arndt, N. Smith, F. Tausk, Stress and atopic dermatitis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports,8, 312–317 (2008). [↩]

- S. Baum, N. Sakka, O. Artsi, H. Trau, A. Barzilai, Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmunity Reviews, 13, 482–489 (2014). [↩]

- S. C. Segerstrom, G. E. Miller, Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 601–630 (2004). [↩]

- Y. W. Yew, A. H. Y. Kuan, L. Ge, C. W. Yap, B. H. Heng, Psychosocial impact of skin diseases: A population-based study. PLOS One,15, e0244765 (2020). [↩]

- Rønnstad, Amalie Thorsti Møller, et al. “Association of atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 79, 3, 2018, 448–456. [↩]

- J. K. Kiecolt-Glaser, L. McGuire, T. F. Robles, R. Glaser, Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological influences on immune function and health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 537–547, 2002 [↩]

- M. Talamonti, M. Galluzzo, D. Silvaggio, P. Lombardo, C. Tartaglia, L. Bianchi, Quality of life and psychological impact in patients with atopic dermatitis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10, 1298–1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10061298, 2021 [↩]

- Y. Schönmann, K. E. Mansfield, J. F. Hayes, K. Abuabara, A. Roberts, L. Smeeth, S. M. Langan, Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: A population-based cohort study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Practice, 8, 248–257.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.030, 2020 [↩]

- J. P. Gouin, J. K. Kiecolt-Glaser, The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: Methods and mechanisms. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, 31, 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.010 (2011). [↩]

- J. Hanifin, G. Rajka, Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermato-Venereologica Supplementum, 59, 44–47 (1980). [↩]

- S. Stansfeld, B. Candy, Psychosocial work environment and mental health: A meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 32, 443–462 (2006). [↩]

- M. Virtanen, M. Kivimäki, M. Joensuu, J. Virtanen, A. Elovainio, J. Vahtera, Long working hours and coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176, 586–596 (2012). [↩]

- M. Prins, P. Verhaak, H. Bensing, H. van der Meer, Health beliefs and perceived need for mental health care of anxiety and depression: The patients’ perspective explored. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 103 (2008). [↩]

- C. Baglioni, S. Nanovska, W. Regen, K. Spiegelhalder, B. Feige, C. Nissen, C. F. Reynolds III, D. Riemann, Sleep and mental disorders: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 969–990 (2016). [↩]

- F. N. Jacka, A. O’Neil, S. E. Quirk, S. Housden, S. L. Brennan, L. J. Williams, J. A. Pasco, M. Berk, Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e31–e42 (2014). [↩]

- N. Schmitz, J. Kruse, J. Kugler, Disabilities, quality of life, and mental disorders associated with smoking and nicotine dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1670–1676 (2003). [↩]

- P. Cuijpers, A. Beekman, J. Reynolds III, C. Reynolds, Preventing depression: A global priority. JAMA, 298, 180–181 (2007). [↩]

- American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. American Psychiatric Publishing (2013). [↩]

- K. Kroenke, R. L. Spitzer, J. B. W. Williams, The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613 (2001). [↩]

- S. Cohen, D. Janicki-Deverts, G. E. Miller, Psychological stress and disease. JAMA, 298, 1685–1687 (2007). [↩]