Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a subset of stem cells found in tumors that possess the ability to self-renew and proliferate. CSCs play a crucial role in maintaining tumor resistance and initiating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), making them a key therapeutic target. Numerous signaling pathways, particularly Notch, Wnt/β-Catenin, and Hedgehog, are involved in maintaining stemness and its undifferentiated state. Therefore, CSCs have become a promising target during cancer treatment using small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which are molecules that interact with targeted proteins and reduce their biological activity. However, due to rapid innovation in this field, many promising targeted therapies remain unexplored without further clinical studies, hindering the advancement of this field. This systematic review synthesizes recent clinical trials that target CSC signaling pathways and evaluates current therapeutic approaches to inhibit them. This was done by searching PubMed for clinical trials that targeted the three CSC pathways. Targeting CSC signaling pathways presents promising strategies for combating cancer recurrence and resistance to treatment by addressing the key molecular mechanisms that drive tumor growth, metastasis, and drug resistance. However, challenges such as the complexity of the pathway and the severe side effects of available drugs targeting these pathways limit the effectiveness of current medications, requiring further research to develop more precise and less toxic treatments. Nevertheless, WNT974, Niclosamide, and Demcizumab have been identified to show the most promise for future clinical studies.

Keywords: Cancer Stem Cells, Signaling pathways, Targeted Therapy, Notch, Wnt/β-Catenin, Hedgehog.

Introduction

Cancer stem cells were discovered in acute myeloid leukemia in 1994. A study identified a subset of cancer cells with self-renewal abilities and pluripotency, when a small fraction of leukemia cells was shown to initiate tumorigenesis when transplanted into severely combined immunodeficient mice1. CSCs are important when considering cancer therapy due to three properties: controlling the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), resisting immunotherapy, and differing phenotypes. First, recent studies attributed CSCs as the reason why typical cancer treatments fail because they contribute to metastasis and recurrence by supporting other cancer cell populations2. EMT is typically activated during embryogenesis by the Notch signaling pathway; however, it is also commonly activated during metastasis. The expression of CD44+, a common biomarker of CSCs, in breast cancer cells was an indicator of cells involved in metastasis, implying the role of CSCs during EMT and metastasis3. Second, CSCs are characterized by their resistance to immunotherapy that targets rapidly proliferating cells, such as traditional chemotherapy. CSCs are typically quiescent or dormant, allowing them to escape the effects of conventional cancer therapies such as chemotherapy, which result in cancer recurrence4. Third, CSCs are difficult to identify due to their differing phenotypes. For example, increased levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) act as a CSC marker in multiple cancers, including leukemia, breast cancer, colon cancer, and liver cancer5 But, high levels of ALDH do not identify all tumor types, as prostate cancer does not have increased ALDH levels6. In a similar vein, CD44+, CD133+, and CD34+ serve as common surface markers for multiple CSCs; however, there has not yet been a universal cell biomarker that can be used to identify all CSCs. Due to their role in cancer metastasis and resistance to treatment, identifying molecules that can target CSCs has become imperative to further cancer treatment; however, this suggests that CSC heterogeneity remains a major barrier to effective treatment. The limitations of traditional therapies against CSCs establish targeted therapy using SMIs and mAbs as a viable alternative.

During this review, the function of the three major signaling pathways is discussed, as well as the different methods and drugs currently discovered to target these signaling pathways. In recent years, there has been a large increase in the number of studies investigating novel therapies targeting CSC. A key factor in regulating CSCs has been inhibiting key signaling pathways such as Hedgehog, WNT/β-Catenin, and Notch pathways. This review will focus on the question of whether these three signaling pathways can be used as targets for cancer therapy by evaluating the efficacy, dosage, and toxicity, biomarkers for predictive success, and resistance mechanisms. This fills the gap in the current literature of a comprehensive review of these therapies, as most reviews either solely focus on one of these signaling pathways or do not focus on clinical trials. Additionally, by focusing on currently discovered targeted therapies and the state of clinical application and study, this review will recommend potential inhibitors of CSC signaling pathways to be further explored in future clinical studies. The targeted therapies discussed in this review will focus on those with a direct effect on the three selected signaling pathways to limit the scope of this review.

Methods

An initial scoping search identified two relevant systematic reviews, which informed the criteria for the search (Table 1)7. The pathways mTOR and NF-κB were excluded from this review due to how both act as broad regulators that affect numerous cellular processes, making it challenging to attribute effects specifically to cancer stem cell phenotypes. By searching “x AND Targeted Therapy” on PubMed, where x is the signaling pathways that were identified by the initial review, the most researched pathways could be discovered. As a result, Notch, Wnt/β-Catenin, and Hedgehog were chosen from the rest of the signaling pathways as they had a substantial body of research on targeted therapies. They were the most relevant, with the most research currently being conducted on them, as well as allowing for a more focused and in-depth analysis of this topic. From there, PubMed was searched for clinical trials using the search words Notch, Hedgehog, WNT/β-Catenin, with and/or Boolean operators (Table 2). There was no limitation on the publication date; however, when older studies were found, further searching was done to discover more recent findings. These supplemented articles are not limited to clinical trials. All searches were limited to the English language leading to potential bias to western findings. In addition, bibliographies of identified articles were manually searched for relevant studies. From the initial cohort of articles, the articles were excluded if the focus of the study was on molecules not targeting the specified pathway or if they included children as study participants, as children have different immune responses to cancer and targeted therapy, which may complicate the findings8. Key findings were compiled into a comprehensive review of current methods of inhibiting CSC signaling pathways through targeted therapies (Table 3). This review organized findings by grouping targeted therapies into the signaling pathway they targeted, then by the specific therapy that was trialed. By doing this, it is easier to comprehend the different categories of inhibitors to identify promising targeted therapies for further study.

| WNT | Hedgehog | Notch | JAK/STAT | SMAD | PPAR | Nanog | |

| Article Hits | 139 | 107 | 61 | 55 | 23 | 7 | 6 |

| Database Searched | Search terms | Hits |

| PubMed | Hedgehog AND Cancer | 123 |

| WNT OR Beta-Catenin AND Cancer | 185 | |

| NOTCH AND Cancer | 86 |

Hedgehog

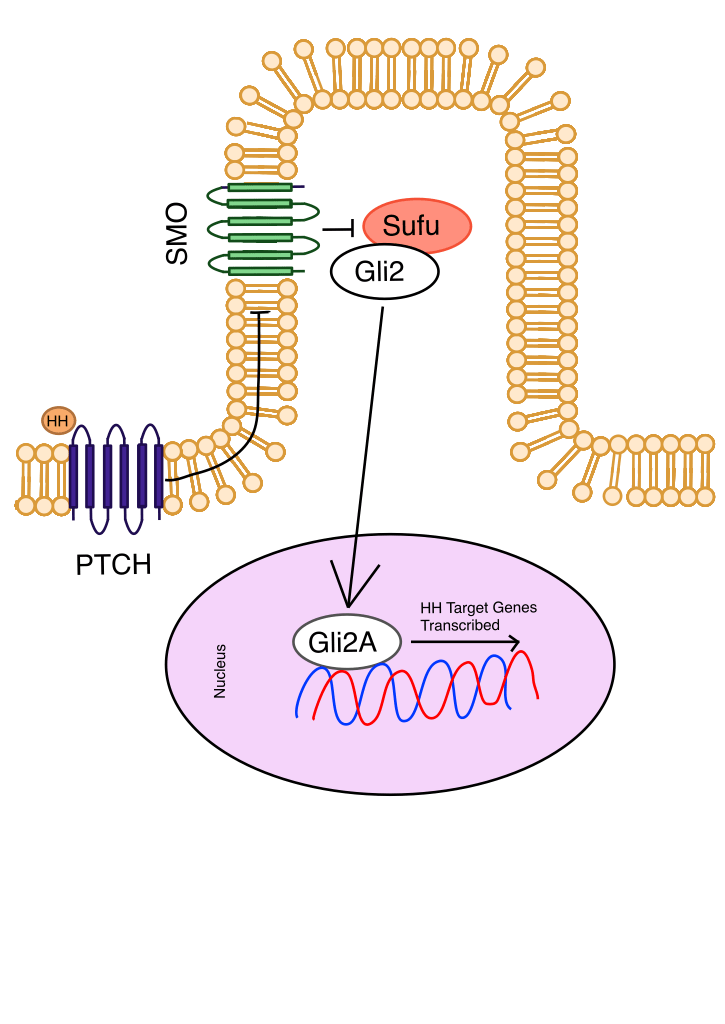

Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

Hedgehog (Hh) is a pathway typically expressed during an organism’s development by controlling adult tissue homeostasis (Figure 1). However, when Hh is misregulated due to mutations in molecules involved in the regulatory system of Hh, it can play a role in CSC differentiation, leading to enhanced cancer growth9. For example, a loss-of-function mutation in the Patched (PTCH) gene, which acts as a tumor suppressor, prevents the suppression of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. This mutation in PTCH is implicated in the growth of sporadic basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Hh is also vital for maintaining CSC levels in the cells, as a loss of SMO activation impairs chronic myelogenous leukemia stem cell renewal10. Non-canonical Hh pathways operate by bypassing SMO, either by utilizing non-SMO signaling molecules or interacting with other signaling pathways, reducing the efficacy of therapies that solely target SMO11. Of the 123 clinical trials originally indexed, 22 of them were deemed significant and relevant for inclusion in this review. Current therapies involving the Hh pathway target SMO to regulate the transcription of Hh-related genes, as it is the main transducer of the Hh pathway. Due to the initial scope for solely clinical trials, important preclinical studies on Cyclopamine were supplemented through separate research due to its importance in understanding the progression of SMO regulation.

Cyclopamin

Cyclopamine was the first SMO inhibitor discovered for use in cancer treatment. Prostate cancer cell lines were treated with cyclopamine and showed as high as an 80% decrease in cell proliferation as well as decreased Gli1 expression, directly linking cyclopamine to inhibition of cancer growth through inhibition of the Hh signaling pathway12. In one study, heterozygous PTCH1 knockout mice were either treated with cyclopamine in their drinking water for 20 weeks or left as a control group. The mice that were treated with cyclopamine showed a 90% reduction of microscopic BCCs compared to the control, while having the overall survival (OS) rate unaffected13. Treatment with cyclopamine in HCT-166 cells resulted in the down-regulation of CSC-associated biomarkers NANOG, POU5F1, and CD-44, suggesting possible biomarkers for monitoring efficacy in future studies14. Despite the significant effect of cyclopamine on colorectal cancer (CRC), BCC, and Prostate cell lines, in vivo trials on mice found that cyclopamine caused negative side effects. Gross facial defects were present in 3 out of 10 mouse embryos exposed to cyclopamine, such as being smaller than expected, having cleft lips and palates, open eyelid defects, and forelimb syndactyly, along with permanent defects in bone development and apoptosis15,16. Despite strong preclinical efficacy, these severe dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) have prevented clinical trials on humans. Its targeting mechanism of directly associating with SMO has informed the development of safer SMO inhibitors that are in clinical use.

Vismodegib

Vismodegib is an SMO inhibitor of the sonic hedgehog pathway. Seven clinical trials were chosen for this section: four in phase I, two in phase II, and one in phase IV. All but one clinical trial focused on BCCs, with the trial focused on Vismodegib for acute myeloid leukaemia discovering minimal clinical efficacy. In Phase 1 studies of BCC using Vismodegib, 18 out of 33 and 19 out of 33 patients had a response to Vismodegib, having an average efficacy rate of 56%17. A dose-discovery trial testing 150 mg, 270 mg, and 540 mg of Vismodegib, pharmacokinetics analysis found that all amounts had the same plasma concentration of Vismodegib, leading to 150 mg the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D). Treatment once a day (OD) was also found to be more effective than less frequent schedules, maintaining consistently high levels of steady-state plasma vismodegib concentration18. No Grade 5 effects were associated with vismodegib, and the most common Grade 4 effect was asymptomatic hyponatremia, along with other adverse events (AE), including fatigue, pyelonephritis, presyncope, paranoia, and hyperglycemia19,20. Biomarker analysis revealed down-modulation of GLI1 in treated patients, while a patient with medulloblastoma demonstrated resistance to vismodegib due to a mutation in SMO.

In Phase II trials, the efficacy of vismodegib was more variable, with one trial that used 150 mg of vismodegib for a total of 12 weeks only having a 43% response rate, while a clinical trial of 12 weeks of vismodegib was followed by 7 weeks of cotherapy with radiation therapy, and the 5-year progression-free survival (PFD)was 78%21. This difference may relate to the longer treatment duration (19 weeks vs. 12 weeks) despite identical dosing22. A common AE observed during these trials was muscle spasms, with no patient experiencing treatment-related grade 4 or 5 AEs. These muscle spasms were reversible after the end of the treatment, with 16 out of 19 patients achieving full resolution within 6 weeks, which was observable due to the longer observational period of one study. Overall, no new biomarkers or resistances were discovered in Phase 2 trials of Vismodegib. As a result of these successful Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, Vismodegib became the first FDA-approved selective Hh pathway inhibitor for BCC in 2012.

Sonidegib

Six BCC focused clinical trials were chosen for this section: three in phase I and four in phase II. The original efficacy of Sonidegib was 38.9%23. A dose-discovery trial testing 400 mg, 600 mg, and 800 mg of Vismodegib with 80 mg of paclitaxel, of which 800 mg daily had the largest effect. However, another trial found that 200 mg was equally effective while not causing DLTs, leading to both 200 mg and 800 mg considerations for the RP2D24. Common mild AEs at this stage of clinical trials were creatine phosphokinase elevation (20%), dysgeusia (50%), and vomiting, with a few grade 3/4 AEs25. However, almost 42% of participants had their dose lowered due to mild AEs, leading to further consideration about the combination of Sonidegib with other adjunct treatments. Effective treatment caused a reduction in the GLI1 biomarker in the tumor, relating to the mechanism of action of Sonidegib by the inhibition of SMO. Phase 2 trials of sonidegib demonstrated meaningful efficacy in advanced BCC, with the 200 mg daily dose achieving overall response rates (ORR) of 44% in locally advanced patients and 15% in metastatic disease, which are similar to the efficacy rates of the 800 mg daily dose (38% and 17% respectively)26. The 200 mg regimen is preferred, as increasing the dose did not improve efficacy but increased the frequency of grade 3/4 AEs (30). No new safety concerns emerged in these longer and larger clinical trials with muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, nausea, and creatine phosphokinase elevation being the most common AEs27. No concerns were raised about the long-term efficacy of Sonidegib, as after 42 months of treatment, it remained potent at inhibiting SMO. Soon after, in 2015, Sonidegib was also FDA-approved for use in cancer treatments in advanced and metastatic BCC.

Glasdegib

In an initial phase 2 trial, 46.4% of patients went into complete remission after receiving 100 mg of glasdegib orally in 28-day phases. Additionally, the median OS was 14.9 months with a 12-month survival rate of 66.6%. A dose-discovery trial started at 5 mg and increased by 100% until the patient experienced DLTs. Through this, the RP2D was 200 mg maximum, with lower doses being proportional to pharmacokinetics28. Later clinical trials would go on to use 100 mg of glasdegib daily. The most common treatment-related AEs neutropenia (63.8%), diarrhea (70.0%), and grade 4 thrombocytopenia (27.5%)29. After these promising results, Glasdegib was approved by the FDA in 2019 in combination with low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adult patients who are 75 years old or older or those who cannot use intensive induction chemotherapy30. No biomarker tests or resistance to treatment were mentioned in these clinical trials.

WNT/β-Catenin

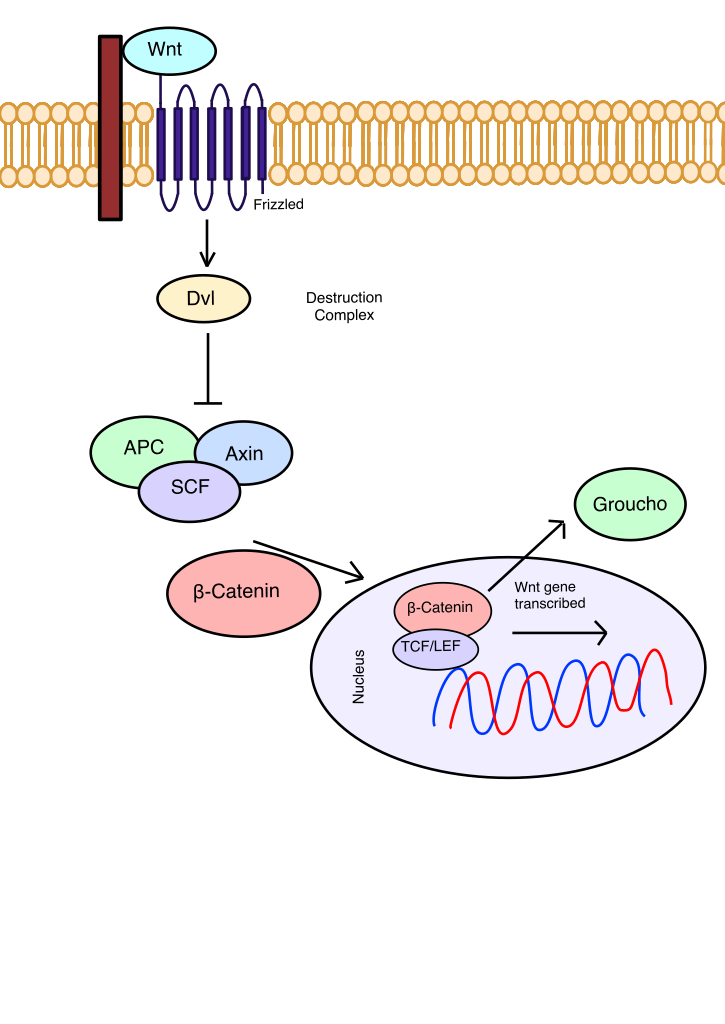

WNT/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

The WNT/β-Catenin pathway is a pathway that typically regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis when normally expressed (Figure 2). However, it is important to consider for cancer therapies because the expression of WNT target genes is inversely correlated with cancer prognosis31. This may be due to WNT’s role in facilitating metastasis by assisting CSCs in entering the bloodstream to spread to other sections. If a loss-of-function mutation occurs in APC, a component of the destruction complex, the destruction complex is deactivated, and WNT target genes are expressed32. Non-canonical WNT signaling, which does not involve β-Catenin and follows either the WNT/PCP or WNT/Ca2+ pathways, maintains the quiescent state of CSCs during metastasis and promotes EMT33. WNT/β-Catenin signaling also induces cancer-associated fibroblast activation during CRC growth and proliferation34. WNT plays a major role in tumor progression, rendering it a strong target for cancer treatment. However, with 19 glycoproteins and 10 Frizzled receptors, the complexity of the WNT signaling pathways makes inhibiting WNT challenging. 12 articles were used to establish the current therapies inhibiting the WNT/β-Catenin pathway, including Vantictumab, Ipafricept, WNT974, Niclosamide, and LY2090314.

Vantictumab

Vantictumab is a mAb that can inhibit the Frizzled receptors 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 during canonical WNT signaling, allowing it to overcome the main issue with targeting WNT: its complexity and redundancy of its components. In two Phase 1b clinical trials, one that combined Vantictumab with Paclitaxel and another that combined nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine with Vantictumab, resulted in an ORR of 31.3% and 41.9% and a clinical benefit rate (CBR) of 68.8% and 77.4% in HER2-negative breast and pancreatic cancer, respectively35. Despite the effective clinical application, higher doses of 14.0 mg/kg every 2 weeks and 8.0 mg/kg every 4 weeks resulted in higher rates of bone fractures in patients36. Another Phase 1b trial found that 5 mg/kg every 4 weeks was the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Additionally, dosing Vantictumab before any taxane chemotherapies, like nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine, led to enhanced antitumor effects in one study, suggesting the ability of combination therapies for increased positive outcomes37. Other than bone fractures, AEs related to Vantictumab included nausea, alopecia, and fatigue, without any DLTs. A 6-gene Wnt pathway biomarker was found to show significant association with higher PFS and OS in Vantictumab-treated patients. Despite high effectiveness, the unacceptable rate of bone fractures led to these trials being discontinued.

Ipafricept

Ipafricept is another mAb targeting Frizzled that has exhibited antitumor effects in multiple Phase 1b clinical trials. Ipafricept’s mechanism of action is to block WNT signaling by acting as another WNT molecule receptor, binding to WNT, preventing secreted WNT molecules from binding to Frizzled, and leading to the inactivation of WNT genes. One trial reported an 81% CBR, which includes complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD)38. Initially, Ipafricept has an MTD of 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks, but in light of fragility fractures, a new bone safety plan and a lowered dose to 6 mg/kg was found to be optimal39. Almost all patients throughout the 3 clinical trials reported AEs related to the studied treatment, with the most common being fatigue, decreased appetite, dysgeusia, and nausea, which were mostly grade 1 or 2 without any patient deaths associated with the trials. However, similar to Vanticumab, 2 patients experienced grade 2 fragility fractures at a 20 mg/kg dosage. A decrease in the expression of Wnt pathway target genes such as LGR6 and DKK1 was documented to demonstrate effective inhibition of WNT by Ipafricept, but no biomarkers were indicated to determine which patients Ipafricept would benefit the most40. Due to the frequency of fractures, despite how Ipafricept showed less severe AEs than Vantictumab or Paclitaxel without any fragility fractures or DLTs, Ipafricept trials were canceled.

WNT974

Porcupine is a popular target within the WNT/β-Catenin pathway by targeted therapies like WNT974 and Niclosamide (Nic). Porcupine is an extracellular membrane-bound O-acyltransferase (MBOAT) involved in the palmitoylation of WNT, which is the attachment of fatty acids to proteins. The palmitoylated WNT gains the ability to bind to WNTless (wls), a cargo receptor that transports bonded WNT to Frizzled41. A Phase 1 trial of single-agent WNT974 resulted in 4% of patients experiencing DLTs, including asthenia and epileptic seizures at 10 mg OD, dysgeusia at 5 mg every 2 days and 30 mg OD, and constipation at 22.5 mg OD, all related to the study treatment. The RP2D was set at 10 mg OD. More importantly, 6.4% of patients experienced bone-related disorders, including osteoporosis, pathological fracture, osteopenia, and Grade 3 spinal fractures. Nevertheless, the disease control rate (DCR) was 35.7%, making WNT974 an effective and promising targeted therapy for further trials. Patients with mutations in RNF43 and APC were more likely to show some reduction in tumor size, with the patients with the greatest reduction lacking mutations in KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, APC, and CTNNB142. Another clinical trial was attempted with WNT074 in combination with Encorafenib and Cetuximab, but a high percentage of DLTs (75%), mostly consisting of bone fractures, hypercalcemia, and pleural effusion, and a low ORR (10%) led to the study’s discontinuation43. This suggests that WNT974 may be more effective as a monotherapy, although further trials are needed to confirm this conclusion.

Niclosamide

Originally, Niclosamide was FDA-approved in 1982 for the treatment of tapeworm infections; however, a clinical trial has attempted to discover the effect of Nic for prostate and CRC44. Nic’s anticancer effects are due to its ability to damage cancer cell mitochondria, inhibit signaling pathways like WNT/β-Catenin, and impede CSC activity45. One Phase 1 dose-escalation study found that 500 mg three times a day (TID) was the MTD, as the cohorts in higher doses had prolonged grade 3 AEs. However, pharmacokinetic studies found that the plasma concentrations of MTD were not consistently above the expected therapeutic threshold, which led to the cessation of this study for niclosamide in CRC46. The lower-than-expected plasma concentration at 500 mg TID may be supplemented with the use of other targeted drugs and chemotherapy in conjunction with Niclosamide. As a result, several drugs are also prescribed with Nic to enhance its antitumor effects while limiting the side effects associated with Nic in preclinical trials. For instance, Paclitaxel targets triple-negative breast cancer and esophageal cancer by inhibiting the creation of tubulin47,48. In breast cancer, Doxorubicin increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induces apoptosis49. In glioblastoma, temozolomide causes DNA damage through alkylation, while in CRC, Oxaliplatin increases H2O2, leading to cell cycle arrest50,51.

Notch

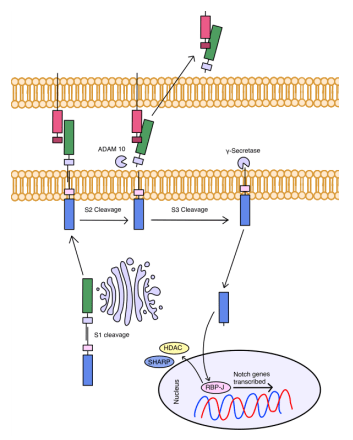

Notch Signaling Pathway

The Notch signaling pathway is highly conserved as it plays a role in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis during organism development (Figure 3). Targeting the Notch signaling pathway is difficult because different Notch ligands can have distinct and sometimes contrary effects on cancer cells. For example, over-expression of Notch was observed in breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer, whereas in prostate, skin, and liver cancer, Notch was down-regulated52. In CRC, high expression of Notch1 was associated with a poor prognosis. However, the high expression of Notch 2 indicates a positive prognosis53. Its critical role in these actions makes it vulnerable to dysregulation, which can lead to cancer. Previous studies have shown that understanding Notch signaling is essential because when it is dysregulated, it leads to angiogenesis and metastasis and plays a vital role in regulating immune cells and CSC differentiation54,55. Despite these complexities, Notch has been a novel target for immunotherapy with many targeted therapies, like DAPT, RO4928087, PF-03084014, Rovalpituzumab Tesirine, and Demcizumab.

DAPT

DAPT targets γ-Secretase which plays a role in cleaving multiple different types of type 1 transmembrane proteins, such as Notch, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and CD44. This results in γ-Secretase inhibitors (GSI) having greater side effects as they can target other molecules instead of solely Notch. DAPT is a well-established γ-secretase inhibitor as DAPT is used as a controlled element in studies on other Notch inhibitors. DAPT utilizes a similar mechanism of action as other GSIs by preventing the S3 cleavage of NICD through the inhibition of γ-Secretase. DAPT, as a GSI, can inhibit proliferation, induce cell-cycle arrest, and cause apoptosis in multiple cancers. It also has a role in overcoming drug resistance by depleting CSCs in osteosarcoma, leading to increased tumor sensitivity when paired with cisplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapy drug56. However, DAPT has dose-limiting side effects, preventing its clinical use as a monotherapy. This has been overcome by combining a lower dose of DAPT with other chemotherapeutic agents such as ATRA and SAHM1 in two different gastric cell lines, as well as in human limbal stem cells57,58.

RO4929097

RO4929097 (RG-4733) is a GSI that results in Notch signaling inhibition. It is difficult to understand the toxicity and anti-tumor effect of RG-4733 at the Phase 1 dose-escalation stage, as its mechanism of action typically results in inhibition of the cell cycle instead of inducing cell death59. However, one phase 1 study observed that 73 % of patients had stable disease, of which 40 % completed at least six cycles of treatment (4 months) without experiencing disease progression60. The RP2D was found to be 20 mg at a 3/4 schedule (3 days on, 4 days off) for 21 days. Pharmacokinetic analysis also discovered that RG-4733 is prone to autoinduction at higher concentrations, which is where a compound induces its own metabolism, leading to increased tolerance of the drug. This led to 20 mg being set as the recommended dose. Side effects that were related to the study drug were nausea, vomiting, hypophosphatemia, diarrhea, and fatigue, with most of them being grade 1 or 2 AEs61. Notch signaling biomarkers of Jadded1, N1-ICD, and Notch3 were evaluated; however, there was no significant difference in staining of tissue from patients of different treatment lengths. Higher levels of Notch3 protein expression were also observed to be associated with resistance to RG-4733; however, concrete conclusions could not be made from these phase 1 studies.

Due to the apparent tolerance towards RG-4733, further phase 2 trials were conducted. All three trials used the RP2D of 20 mg of RG-4733 with a 3/4 schedule. Despite efficacy in phase 1 studies, only 1.3% of patients had an objective response to the treatment, and a further 32% had stable disease during the patient period62,63. The treatment was highly tolerated with no observed grade 3 AEs associated with the treatment, and grade 1/2 nausea was the most common AE (CRC). Histological staining of archival pathology specimens was unable to find a correlation between Notch 1 activation and oncogenic expression. Due to the lack of clinical effect, RG-4733 was considered ineffective as a monotherapy, although potential use as a combination therapy remains open.

PF-03084014

PF-03084014 is another GSI that has shown promise as a targeted therapy for CSC and cancer cells in three main clinical trials. A phase 1 trial determined the RP2D to be 150 mg twice a day (BID) due to a better safety profile compared to higher diseases. The efficacy of subsequent trials varies, with one study finding that 10.8% of patients experienced a partial response while others found that up to 29% of patients had a partial response to the treatment64. PF-03084014 was found to be more effective against desmoid tumors compared to other cancers, with all of the patients with an ORR in a phase 1 trial that had a partial response being those with desmoid tumors, which led to further trials focusing solely on desmoid fibromatosis. Grade 1 and 2 AEs, especially diarrhea (76%) and skin disorders (71%), were experienced by all patients, but only one grade 3 reversible hypophosphatemia was observed in 47% of patients. It is a known effect of GSIs that were suspected to be related to GI loss65. Generally, PF-03084014 is well tolerated with only 9 patients experiencing DLTs that resulted in dose-reduction and not deaths related to the treatment66. As a result, PF-03084014 is a very promising targeted therapy to investigate in the future.

Rovalpituzumab Tesirine

Rovalpitzuzumab Tesirine (Rova-T) is a mAb that targets Delta-like Ligand 3 (DLL3) to inhibit the Notch signaling pathway. Rova-T is highly specific, as DLL3 is not present in normal adult tissues but is highly expressed in Small Cell Lung Cancer. In one phase 1 dose-escalation study, Rova-T has an objective response rate of 63% at 0.1 mg/kg Rova-T and 33% at 0.2 mg/kg Rova-T. The remaining 2 cohorts who received higher doses had a large percentage of participants discontinue the study, leaving the lower dose recommended. Patients who received 0.2 mg/kg plus CE had a lower frequency of AEs compared to other doses, with the most common drug-related AEs being fatigue, neutropenia, photosensitivity reaction, and thrombocytopenia67. A later Phase 3 study brings into question the effectiveness of Rova-T as it was terminated early due to similar levels of death in Rova-T patients and the placebo group68.

Demcizumab

Currently, 3 clinical trials have been done to investigate the effect that Demcizumab, a mAb that targets Delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4), has on inhibiting the maintenance of chemotherapy-resistant CSCs and angiogenesis. In phase 1 dose-discovery trials, Demcizumab was found to have a CBR of 88% with 1 patient having a CR, 19 patients having a PR, and 15 patients having SD69. Demcizumab as an adjunct treatment may be more effective, as Demcizumab alone only has an overall DCR of 40%. The RP2D is 5 mg/kg given every 2-3 weeks, depending on whether the patient is undergoing adjunct treatments. Demcizumab with Pemetetrex and Carboplatin has an RP2D of 5 mg/kg every 3 weeks, while Demcizumab as a monotherapy has an RP2D of 5 mg/kg every other week70. Demcizumab was generally well tolerated, with the most common AEs being diarrhea (68%), fatigue (58%), peripheral edema (53%), and nausea (53%)71. Hypertension was also another common AEs with 8% of patients developing Grade 3 pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure after multiple infusions of the treatment72. Biomarkers associated with Notch signaling were found to be significantly decreased in effective treatment with Demcizumab, making these genes a useful identifier of treatment success. As DLL4 is most connected to CSCs and their ability to escape chemotherapy, Demcizumab’s efficacy against cancer is highly promising.

| Therapy | Target | Development Stage | ORR | Dose | Grade 3> AEs | Common Side Effects |

| Vismodegib | SMO (Hh) | FDA Approved | 49.18% | 150 mg OD | 35.28% | Muscle spasms, Nausea, and Diarrhea |

| Sonidegib | SMO (Hh) | FDA Approved | 44.20% | 200 mg OD | 17.58% | Elevated Creatine Kinase, Dysgeusia, and Nausea |

| Glasdegib | SMO (Hh) | FDA Approved | 46.40% | 100 mg OD | 5.99% | Febrile Neutropenia, Diarrhea, and Thrombocytopenia |

| Vantictumab | Frizzled (Wnt) | Phase 1b | 14.00% | N/A | 27.00% | Nausea, Fatigue, Alopecia, and Peripheral Neuropathy |

| Ipafricept | Frizzled (Wnt) | Phase 1b | 36.70% | N/A | 7.78% | Neutropenia, Fatigue, Nausea, and Diarrhea |

| WNT974 | Porcupine (Wnt) | Phase 2 | 22.80% | 5 mg OD | 53.50% | Dysgeusia, Decreased Appetite, Hypercalcemia, and Bone-related Disorders |

| Niclosamide | WNT | Phase 1 | N/A | 500 mg TID | 40.00% | Nausea, Anorexia, and Weight Loss |

| RO4929097 | γ-secretase (Notch) | Phase 2 | 4.67% | 30 mg OD | 29.17% | Nausea, Fatigue, Anorexia, and Hypophosphatemia |

| PF-3084014 | γ-secretase (Notch) | Phase 1 | 56.94% | 150 mg BID | 37.84% | Diarrhea, Nausea, Fatigue, and Hypophosphatemia |

| Rova-T | DLL3 (Notch) | Phase 3 | 36.00% | 0.01 mg/kg | 58.97% | Nausea, Fatigue, Photosensitivity reaction, Pleural effusion, and Peripheral Edema |

| Demcizumab | DLL4 (Notch) | Phase 1 | 24.36% | 10 mg/kg every other week | 21.44% | Fatigue, Nausea, Hypertension, and Thrombocytopenia |

Discussion

Key Findings

The central objective of this review was to evaluate whether CSC signaling pathways can be effectively targeted by SMIs and mAbs. Recent advancements in targeted therapies have confirmed CSCs’ pivotal role in tumor development and revealed many small-molecule drugs with a clinically proven or promising ability to eradicate CSCs and cancerous cells.

The three signaling pathways covered in this review, Hedgehog, Wnt/β-Catenin, and Notch pathways, differ in their application for targeted therapy (Table 4). At present, Hedgehog is the most well-developed target, with multiple U.S. FDA-approved therapies that all target SMO. However, a high number of bone-related DLTs limit the applicability of this drug. Wnt/β-Catenin similarly affects the bones, with Vantictumab, Ipafricept, and WNT974 all causing fragility-related fractures. Wnt has the largest variety of targets, with drugs being trialed that target Frizzled, Porcupine, and GSK3. Therapies targeting γ-secretase were proven to be the least toxic pathway target, with all but one drug experiencing little to no DLTs in the mentioned clinical trials. In sum, Wnt offers the widest variety of potential drug targets while Notch presents the least toxicity, making both promising directions for future therapeutic study.

Of the 14 drugs examined during this review, only three (Vismodegib, Sonidegib, and Glasdegib) were FDA-approved for use in cancer therapy, with the clinical trials of the remaining 11 drugs discontinued or not finished. Of these drugs, WNT974, Niclosamide, and Demcizumab show therapeutic potential. WNT974 was discontinued as part of a combination therapy, but it shows promise as a monotherapy due to a phase 1 trial that demonstrated significantly fewer DLTs than when used as a combination therapy. Niclosamide was discontinued as a monotherapy for CRC due to low plasma concentration at the recommended dose, but preclinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of Niclosamide in combination with a variety of other chemotherapeutic drugs, including Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin, temozolomide, and Oxaliplatin. Further Phase 1 clinical trials should be held to understand the clinical application of Niclosamide as a co-therapy. Finally, Demcizumab is promising as it was well-tolerated with a high CBR, but especially due to its unique targeting of DLL4, which plays a vital role in CSC therapy resistance. As of now, only 3 clinical trials have examined Demcizumab, but more trials should be done to understand whether it is safe at a larger scale for FDA approval.

Implications and Significance

The findings of this review highlight both the potential and limitations of targeting CSCs through their signaling pathways. By systematically reviewing current targeted therapies across three relevant CSC-related signaling pathways, this review contributes to the broader understanding of how CSCs can be targeted pharmacologically for the ability of cancer cells to evade treatment and metastasize. There is a gap between experimental studies and clinical application in this field, with only three of the targeted therapies mentioned in this review being FDA-approved for cancer treatment, demonstrating the importance of further trials to validate their efficacy in humans and manage toxicity. This gap may have three explanations. One is a simple explanation that drug discovery is a process that is often filled with failed drugs that don’t have an effect or are too toxic for use. However, the near ubiquity of CSC pathway inhibitors being ineffective or toxic can be due to how these CSC pathways, when expressed normally, are necessary regulators for human functions, whether it be stem cell differentiation, apoptosis, or organismal growth. Therefore, when these targeted therapies inhibit the signaling of these pathways, it can lead to detrimental effects to the patient. Another explanation is due to the overabundance of drugs stuck at Phase 1 clinical trials, with drugs with potential not being trialed through Phase 3 or 4 to be FDA approved. This is the gap that this literature review aimed to fill with a comprehensive review of these multiple signaling pathways in CSCs, to provide an organized and synthesized review that aids in understanding which drugs show promise.

Limitations

Although this review has focused on the different approaches to targeting signaling pathways with targeted drug therapy, this approach has its limitations. Signaling pathways are complex with many possible targets, but the targeted therapies included in this review typically are selective in their targets, leading to complications with ineffective treatments. Inhibiting essential pathways also has severe side effects, which poses a significant risk of inhibiting these pathways. For instance, Cyclopamine led to severe craniofacial defects due to inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway in a way that prevented clinical application. Furthermore, genetic testing in patients can identify essential biomarkers that aid in determining the origin of cancer signaling pathway mutations, enabling better prescription of targeted therapies. Although biomarkers like Notch3, GLI1, and NANOG are used to identify whether a treatment was successful, a limited number of studies have focused on understanding what biomarkers may be an indication of the specific mutation in the signaling pathways, making it difficult to properly target the mutation section of the pathway. Additionally, the non-canonical signaling pathways of Notch, WNT/β-catenin, and Hedgehog present challenges to targeted therapies due to their abilities to bypass traditional regulatory mechanisms and deactivate target genes through alternate routes. This pathway redundancy and crosstalk often lead to ineffective and inefficient targeting.

Recommendation and Closing Thoughts

Targeted drug therapy is not a one-size-fits-all solution, and further study of potential targets in CSC signaling pathways, such as TGF-β and JAK/STAT3, will be beneficial to furthering this field. Another avenue of potential research would broaden the targeting ability of SMIs and mAbs to target multiple ligands or receptors of the same family, as such findings may greatly improve therapeutic outcomes and reduce resistance to targeted therapies. For example, future researchers may search chemical databases, like Instant JLab or other similar tools, for compounds with a similar structure to Vantictumab and run a cellline assay to discover new SMIs with similar multi-targeting ability but fewer DLTs. However, due to the current lack of clinical trials, it may prove more useful to conduct clinical trials on the molecules already identified, but especially Ipafricept, as it has not indicated any severe DLTs in previous Phase 1b trials. Although there are well-established mechanisms of inhibition, more unique targets remain to be discovered and exploited. As a result, during this review, multiple targeted therapies were examined and identified to show promise in guiding future clinical trials. Despite this, targeted therapies are just one aspect of a larger fight against cancer, requiring years of concerted work from researchers worldwide to identify, test, and implement novel cancer therapies.

Table 4: Study Summary Table

| Year | Therapy | Developmental Stage | Sample Size | Findings | |

| [18] | 2019 | Vismodegib | Phase 1 | 38 | A clinical trial on acute myeloid leukaemia was well-tolerated but minimally effective clinically |

| [19] | 2009 | Vismodegib | Phase 1 | 33 | Effective Response of 18/33 with 2 complete responses. Has 8 Grade 3 AEs |

| [20] | 2011 | Vismodegib | Phase 1 | 68 | Well tolerated with 8.8% experiencing Grade 4 AEs and 27.9% experiencing a Grade 3 AE, RP2D is 150 mg’d with 20 patients experiencing a response. |

| [21] | 2015 | Vismodegib | Phase 2 | 24 | 43% clinical efficiency, but well tolerated with no Grade 4 AEs or deaths associated with the treatment |

| [22] | 2024 | Vismodegib | Phase 2 | 24 | Up to an 83% response rate with a combination of vismodegib and RT. No Grade 4 or 5 AEs associated with the treatment |

| [23] | 2019 | Sonidegib | Phase 1 | 18 | Efficacy of 28.9% but found the RP2D of 800 mg |

| [24] | 2016 | Sonidegib | Phase 1 | 190 | Found that both 200 mg and 800mg are effective, with higher doses causing more AEs without affecting effectiveness |

| [25] | 2014 | Sonidegib | Phase 1 | 103 | MTD was 800 mg, with 18% of patients experiencing elevated serum creatine kinase levels, but they were reversible. Well-tolerated |

| [26] | 2015 | Sonidegib | Phase 2 | 55 | A 200 mg daily dose had a similar ORR of 44% and 15% with 800 mg, but with lower AEs |

| [27] | 2021 | Sonidegib | Phase 2 | 66 | ORR of 74.2% with predominantly Grade 1 or 2 AEs, with the most common Grade 3 AE being muscle spasms at 54.4% |

| [28] | 2018 | Glasdegib | Phase 2 | 71 | 46.4% complete remission with 100 mg of glasdegib, with a median survival of 14.9 months. Febrile neutropenia was the most common Grade 3 AE |

| [29] | 2015 | Gladesgib | Phase 1 | 47 | RP2D of 200 mg with 6.4% of patients experiencing Grade 3 AEs. |

| [35] | 2019 | Vantictumab | Phase 1 | 31 | Fragility fractures were attributed to this treatment at higher doses, making 5 mg/kg every 4 weeks the MTD. Had a CBR of 77.4% |

| [36] | 2020 | Vantictumab | Phase 1 | 48 | The most frequent AE was nausea, alopecia, and fatigue, as well as 6 patients experiencing fractures. The CBR is 68.8%. The 6-gene WNT pathway was a biomarker for PFS. |

| [38] | 2020 | Ipafricept | Phase 1 | 26 | No DLTs and fragility fractures, but fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia were the most common AEs. Had a CBR of 81% |

| [39] | 2019 | Ipafricept | Phase 1 | 37 | Well tolerated with no DLTs. ORR of 75.5% |

| [40] | 2017 | Ipafricept | Phase 1 | 26 | 10 mg/kg was effective, and fragility fractures occurred at 20 mg/kg, so the RP2D is 15 mg/kg Q3W. |

| [42] | 2021 | WNT974 | Phase 1 | 94 | RP2D of 10 mg OD. Dysgeusia was the most common AE at around 50% of patients. It was not the most effective, with no objective responses, but 6% of patients saw a lesion size reduction |

| [43] | 2023 | WNT974 | Phase 2 | 20 | 20% of patients experienced DLTs, and 45% had bone toxicities. Had a disease control rate of 85% |

| [46] | 2018 | Niclosamide | Phase 1 | 5 | No DLTs at the 500 mg TID, but all patients at the 100 mg TID experienced DLTS. |

| [58] | 2014 | RO4929097 | Phase 1 | 18 | RO & gemcitabine can be combined to have a partial response; however, autoinduction does occur at 45 and 90 mg. |

| [59] | 2013 | RO4929097 | Phase 1 | 17 | The most common toxicities related to the treatment were fatigue and mucositis; however, only 2 DLTs were observed in the same patient. 73% of patients had stable disease |

| [60] | 2015 | RO4929097 | Phase 1 | 30 | RP2D is 20 mg orally OD for days 1-3, 8-10, 15-17. Had a clinical benefit for cervical and colon cancer. |

| [61] | 2014 | RO4929097 | Phase 2 | 32 | Well tolerated with the majority of toxicities being Grade 1 or 2, most commonly nausea, fatigue, and anemia. The 1-year overall survival rate was 50%. |

| [62] | 2015 | RO4929097 | Phase 2 | 40 | Insufficient activity as a mono-treatment, as the highest response was stable disease (33%). However, it was highly tolerated. |

| [63] | 2015 | PF-03084014 | Phase 1 | 64 | MTD was 220 mg BID, and the RP2D was 150 mg BID due to similar levels of NOTCH-related target inhibition. 71.4% objective response rate |

| [64] | 2017 | PF-03084014 | Phase 1 | 17 | 65% of patients had stable disease, and 29% had a partial response. The most common AEs were diarrhea (76%) and skin disorders (71%), with the only Grade 3 toxicity being reversible hypophosphatemia (47%). |

| [65] | 2018 | PF-03084014 | Phase 1 | 7 | 71.4% of patients achieved a partial response, taking an average of 11.9 months. The most common side effects were diarrhea (55%) and nausea (38%). |

| [66] | 2021 | Rova-T | Phase 1 | 26 | Rova-T 0.2 mg/kg with platinum-based chemotherapy was tolerable, but there was no efficacy benefit with this combination therapy. |

| [67] | 2021 | Rova-T | Phase 3 | 748 | There is a lack of survival benefit of Rova-T treatment, leading to the termination of the study. |

| [68] | 2017 | Demcizumab | Phase 1 | 46 | A truncated regime of demcizumab was not associated with >Grade 3 toxicities. 50% of patients had objective tumor responses. |

| [69] | 2014 | Demcizumab | Phase 1 | 55 | 64% of patients at 10 mg/kg had evidence of stable disease or response. The RP2D was 5 mg/kg every other week, which was well tolerated, with fatigue and hypertension being the most common AE. |

| [70] | 2020 | Demcizumab | Phase 1 | 19 | No DLTs were observed with the most common treatment-related AEs being diarrhea (68%), fatigue (58%), peripheral edema (53%), and nausea (53%). |

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest appreciation to Dr. Naama Kanarek for her constant support through this research process, along with her knowledge and expertise, which have pushed me to constantly think deeply about the literature and my contributions to it.

References

- T. Lapidot, C. Sirard, J. Vormoor, B. Murdoch, T. Hoang, J. Caceres-Cortes, M. Minden, B. Paterson, M. A. Caligiuri, J. E. Dick. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into scid mice. Nature. 367, 645–648 (1994). [↩]

- Y. Shiozawa, B. Nie, K. J. Pienta, T. M. Morgan, R. S. Taichman. Cancer stem cells and their role in metastasis. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 138, 285–293 (2013). [↩]

- H. Liu, M. R. Patel, J. A. Prescher, A. Patsialou, D. Qian, J. Lin, S. Wen, Y.-F. Chang, M. H. Bachmann, Y. Shimono, P. Dalerba, M. Adorno, N. Lobo, J. Bueno, F. M. Dirbas, S. Goswami, G. Somlo, J. Condeelis, C. H. Contag, S. S. Gambhir, M. F. Clarke. Cancer stem cells from human breast tumors are involved in spontaneous metastases in orthotopic mouse models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107, 18115–18120 (2010). [↩]

- H. Liu, L. Lv, K. Yang. Chemotherapy targeting cancer stem cells. American Journal of Cancer Research. 5, 880–893 (2015). [↩]

- F. Islam, V. Gopalan, R. Wahab, R. A. Smith, A. K.-Y. Lam. Cancer stem cells in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: identification, prognostic and treatment perspectives. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 96, 9–19 (2015). [↩]

- C. Yu, Z. Yao, J. Dai, H. Zhang, J. Escara-Wilke, X. Zhang, E. T. Keller. ALDH activity indicates increased tumorigenic cells, but not cancer stem cells, in prostate cancer cell lines. In Vivo. 25, 69–76 (2011). [↩]

- Y. Liu, H. Wang. Biomarkers and targeted therapy for cancer stem cells. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 45, 56–66 (2024). [↩]

- P. Kattner, H. Strobel, N. Khoshnevis, M. Grunert, S. Bartholomae, M. Pruss, R. Fitzel, M.-E. Halatsch, K. Schilberg, M. D. Siegelin, A. Peraud, G. Karpel-Massler, M.-A. Westhoff, K.-M. Debatin. Compare and contrast: pediatric cancer versus adult malignancies. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 38, 673–682 (2019). [↩]

- D. Doheny, S. G. Manore, G. L. Wong, H.-W. Lo. Hedgehog signaling and truncated gli1 in cancer. Cells. 9 (2020). [↩]

- C. Zhao, A. Chen, C. H. Jamieson, M. Fereshteh, A. Abrahamsson, J. Blum, H. Y. Kwon, J. Kim, J. P. Chute, D. Rizzieri, M. Munchhof, T. VanArsdale, P. A. Beachy, T. Reya. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 458, 776–779 (2009). [↩]

- S. Pietrobono, S. Gagliardi, B. Stecca. Non-canonical hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: activation of gli transcription factors beyond smoothened. Frontiers in genetics. 10, 556 (2019). [↩]

- P. Sanchez, A. M. Hernández, B. Stecca, A. J. Kahler, A. M. DeGueme, A. Barrett, M. Beyna, M. W. Datta, S. Datta, A. Ruiz i Altaba. Inhibition of prostate cancer proliferation by interference with sonic hedgehog-gli1 signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101, 12561–12566 (2004). [↩]

- M. Athar, C. Li, X. Tang, S. Chi, X. Zhang, A. L. Kim, S. K. Tyring, L. Kopelovich, J. Hebert, E. H. Epstein Jr., D. R. Bickers, J. Xie. Inhibition of smoothened signaling prevents ultraviolet b-induced basal cell carcinomas through regulation of fas expression and apoptosis. Cancer Research. 64, 7545–7552 (2004). [↩]

- B.-E. Batsaikhan, K. Yoshikawa, N. Kurita, T. Iwata, C. Takasu, H. Kashihara, M. Shimada. Cyclopamine decreased the expression of sonic hedgehog and its downstream genes in colon cancer stem cells. (2014). [↩]

- H. Kimura, J. M. Y. Ng, T. Curran. Transient inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in young mice causes permanent defects in bone structure. Cancer Cell. 13, 249–260 (2008). [↩]

- R. J. Lipinski, P. R. Hutson, P. W. Hannam, R. J. Nydza, I. M. Washington, R. W. Moore, G. G. Girdaukas, R. E. Peterson, W. Bushman. Dose- and route-dependent teratogenicity, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic profiles of the hedgehog signaling antagonist cyclopamine in the mouse. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 104, 189–197 (2008). [↩]

- Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 17, 2502–2511 (2011). [↩]

- D. Bixby, R. Noppeney, T. L. Lin, J. Cortes, J. Krauter, K. Yee, B. C. Medeiros, A. Krämer, S. Assouline, W. Fiedler, N. Dimier, B. P. Simmons, T. Riehl, D. Colburn. Safety and efficacy of vismodegib in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukaemia: results of a phase ib trial. British journal of haematology. 185, 595–598 (2019). [↩]

- D. D. Von Hoff, P. M. LoRusso, C. M. Rudin, J. C. Reddy, R. L. Yauch, R. Tibes, G. J. Weiss, M. J. Borad, C. L. Hann, J. R. Brahmer, H. M. Mackey, B. L. Lum, W. C. Darbonne, J. C. J. Marsters, F. J. de Sauvage, J. A. Low. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 361, 1164–1172 (2009). [↩]

- P. M. LoRusso, C. M. Rudin, J. C. Reddy, R. Tibes, G. J. Weiss, M. J. Borad, C. L. Hann, J. R. Brahmer, I. Chang, W. C. Darbonne, R. A. Graham, K. L. Zerivitz, J. A. Low, D. D. Von Hoff. Phase i trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (gdc-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 17, 2502–2511 (2011). [↩]

- H. Sofen, K. G. Gross, L. H. Goldberg, H. Sharata, T. K. Hamilton, B. Egbert, B. Lyons, J. Hou, I. Caro. A phase ii, multicenter, open-label, 3-cohort trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of vismodegib in operable basal cell carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 73, 99-105.e1 (2015). [↩]

- C. A. Barker, S. Dufault, S. T. Arron, A. L. Ho, A. P. Algazi, L. A. Dunn, A. A. Humphries, C. Hultman, M. Lian, P. D. Knott, S. S. Yom. Phase ii, single-arm trial of induction and concurrent vismodegib with curative-intent radiation therapy for locally advanced, unresectable basal cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 42, 2327–2335 (2024). [↩]

- A. Stathis, D. Hess, R. von Moos, K. Homicsko, G. Griguolo, M. Joerger, M. Mark, C. J. Ackermann, S. Allegrini, C. V. Catapano, A. Xyrafas, M. Enoiu, S. Berardi, P. Gargiulo, C. Sessa. Phase i trial of the oral smoothened inhibitor sonidegib in combination with paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investigational new drugs. 35, 766–772 (2017). [↩]

- J. Zhou, M. Quinlan, E. Hurh, D. Sellami. Exposure-response analysis of sonidegib (lde225), an oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, for effectiveness and safety in patients with advanced solid tumors. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 56, 1406–1415 (2016). [↩]

- J. Rodon, H. A. Tawbi, A. L. Thomas, R. G. Stoller, C. P. Turtschi, J. Baselga, J. Sarantopoulos, D. Mahalingam, Y. Shou, M. A. Moles, L. Yang, C. Granvil, E. Hurh, K. L. Rose, D. D. Amakye, R. Dummer, A. C. Mita. A phase i, multicenter, open-label, first-in-human, dose-escalation study of the oral smoothened inhibitor sonidegib (lde225) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 20, 1900–1909 (2014). [↩]

- M. R. Migden, A. Guminski, R. Gutzmer, L. Dirix, K. D. Lewis, P. Combemale, R. M. Herd, R. Kudchadkar, U. Trefzer, S. Gogov, C. Pallaud, T. Yi, M. Mone, M. Kaatz, C. Loquai, A. J. Stratigos, H.-J. Schulze, R. Plummer, A. L. S. Chang, F. Cornélis, J. T. Lear, D. Sellami, R. Dummer. Treatment with two different doses of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma (bolt): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 16, 716–728 (2015). [↩]

- R. Gutzmer, C. Robert, C. Loquai, D. Schadendorf, N. Squittieri, R. Arntz, S. Martelli, R. Dummer. Assessment of various efficacy outcomes using erivance-like criteria in patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma receiving sonidegib: results from a preplanned sensitivity analysis. BMC cancer. 21, 1244 (2021). [↩]

- G. Martinelli, V. G. Oehler, C. Papayannidis, R. Courtney, M. N. Shaik, X. Zhang, A. O’Connell, K. R. McLachlan, X. Zheng, J. Radich, M. Baccarani, H. M. Kantarjian, W. J. Levin, J. E. Cortes, C. Jamieson. Treatment with pf-04449913, an oral smoothened antagonist, in patients with myeloid malignancies: a phase 1 safety and pharmacokinetics study. The Lancet. Haematology. 2, e339-346 (2015). [↩]

- J. E. Cortes, B. Douglas Smith, E. S. Wang, A. Merchant, V. G. Oehler, M. Arellano, D. J. DeAngelo, D. A. Pollyea, M. A. Sekeres, T. Robak, W. W. Ma, M. Zeremski, M. Naveed Shaik, A. Douglas Laird, A. O’Connell, G. Chan, M. A. Schroeder. Glasdegib in combination with cytarabine and daunorubicin in patients with aml or high-risk mds: phase 2 study results. American journal of hematology. 93, 1301–1310 (2018). [↩]

- K. J. Norsworthy, K. By, S. Subramaniam, L. Zhuang, P. L. Del Valle, D. Przepiorka, Y.-L. Shen, C. M. Sheth, C. Liu, R. Leong, K. B. Goldberg, A. T. Farrell, R. Pazdur. FDA approval summary: glasdegib for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Clinical Cancer Research. 25, 6021–6025 (2019). [↩]

- F. de Sousa E Melo, S. Colak, J. Buikhuisen, J. Koster, K. Cameron, J. H. de Jong, J. B. Tuynman, P. R. Prasetyanti, E. Fessler, S. P. van den Bergh, H. Rodermond, E. Dekker, C. M. van der Loos, S. T. Pals, M. J. van de Vijver, R. Versteeg, D. J. Richel, L. Vermeulen, J. P. Medema. Methylation of cancer-stem-cell-associated wnt target genes predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Cell Stem Cell. 9, 476–485 (2011). [↩]

- L. Zhang, J. W. Shay. Multiple roles of apc and its therapeutic implications in colorectal cancer. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 109, djw332 (2017). [↩]

- K. Qin, M. Yu, J. Fan, H. Wang, P. Zhao, G. Zhao, W. Zeng, C. Chen, Y. Wang, A. Wang, Z. Schwartz, J. Hong, L. Song, W. Wagstaff, R. C. Haydon, H. H. Luu, S. H. Ho, J. Strelzow, R. R. Reid, T.-C. He, L. L. Shi. Canonical and noncanonical wnt signaling: multilayered mediators, signaling mechanisms and major signaling crosstalk. Genes & Diseases. 11, 103–134 (2024). [↩]

- M. H. Mosa, B. E. Michels, C. Menche, A. M. Nicolas, T. Darvishi, F. R. Greten, H. F. Farin. A wnt-induced phenotypic switch in cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibits emt in colorectal cancer. Cancer Research. 80, 5569–5582 (2020). [↩]

- S. L. Davis, D. B. Cardin, S. Shahda, H.-J. Lenz, E. Dotan, B. H. O’Neil, A. M. Kapoun, R. J. Stagg, J. Berlin, W. A. Messersmith, S. J. Cohen. A phase 1b dose escalation study of wnt pathway inhibitor vantictumab in combination with nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in patients with previously untreated metastatic pancreatic cancer. Investigational new drugs. 38, 821–830 (2020). [↩]

- J. R. Diamond, C. Becerra, D. Richards, A. Mita, C. Osborne, J. O’Shaughnessy, C. Zhang, R. Henner, A. M. Kapoun, L. Xu, B. Stagg, S. Uttamsingh, R. K. Brachmann, A. Farooki, M. Mita. Phase ib clinical trial of the anti-frizzled antibody vantictumab (omp-18r5) plus paclitaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic her2-negative breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 184, 53–62 (2020). [↩]

- M. M. Fischer, B. Cancilla, V. P. Yeung, F. Cattaruzza, C. Chartier, C. L. Murriel, J. Cain, R. Tam, C.-Y. Cheng, J. W. Evans, G. O’Young, X. Song, J. Lewicki, A. M. Kapoun, A. Gurney, W.-C. Yen, T. Hoey. WNT antagonists exhibit unique combinatorial antitumor activity with taxanes by potentiating mitotic cell death. Science Advances. 3, e1700090 (2017). [↩]

- E. Dotan, D. B. Cardin, H.-J. Lenz, W. Messersmith, B. O’Neil, S. J. Cohen, C. S. Denlinger, S. Shahda, I. Astsaturov, A. M. Kapoun, R. K. Brachmann, S. Uttamsingh, R. J. Stagg, C. Weekes. Phase ib study of wnt inhibitor ipafricept with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in patients with previously untreated stage iv pancreatic cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 26, 5348–5357 (2020). [↩]

- K. N. Moore, C. C. Gunderson, P. Sabbatini, D. S. McMeekin, G. Mantia-Smaldone, R. A. Burger, M. A. Morgan, A. M. Kapoun, R. K. Brachmann, R. Stagg, A. Farooki, R. E. O’Cearbhaill. A phase 1b dose escalation study of ipafricept (omp54f28) in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 154, 294–301 (2019). [↩]

- A. Jimeno, M. Gordon, R. Chugh, W. Messersmith, D. Mendelson, J. Dupont, R. Stagg, A. M. Kapoun, L. Xu, S. Uttamsingh, R. K. Brachmann, D. C. Smith. A first-in-human phase i study of the anticancer stem cell agent ipafricept (omp-54f28), a decoy receptor for wnt ligands, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 23, 7490–7497 (2017). [↩]

- F. Yu, C. Yu, F. Li, Y. Zuo, Y. Wang, L. Yao, C. Wu, C. Wang, L. Ye. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted therapies. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 6, 307 (2021). [↩]

- J. Rodon, G. Argilés, R. M. Connolly, U. Vaishampayan, M. de Jonge, E. Garralda, M. Giannakis, D. C. Smith, J. R. Dobson, M. E. McLaughlin, A. Seroutou, Y. Ji, J. Morawiak, S. E. Moody, F. Janku. Phase 1 study of single-agent wnt974, a first-in-class porcupine inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumours. British journal of cancer. 125, 28–37 (2021). [↩]

- J. Tabernero, E. Van Cutsem, E. Garralda, D. Tai, F. De Braud, R. Geva, M. T. J. van Bussel, K. Fiorella Dotti, E. Elez, M. J. de Miguel, K. Litwiler, D. Murphy, M. Edwards, V. K. Morris. A phase ib/ii study of wnt974 + encorafenib + cetuximab in patients with braf v600e-mutant kras wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. The oncologist. 28, 230–238 (2023). [↩]

- J. Ren, B. Wang, Q. Wu, G. Wang. Combination of niclosamide and current therapies to overcome resistance for cancer: new frontiers for an old drug. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 155, 113789 (2022). [↩]

- S.-J. Park, J.-H. Shin, H. Kang, J.-J. Hwang, D.-H. Cho. Niclosamide induces mitochondria fragmentation and promotes both apoptotic and autophagic cell death. BMB Reports. 44, 517–522 (2011). [↩]

- M. T. Schweizer, K. Haugk, J. S. McKiernan, R. Gulati, H. H. Cheng, J. L. Maes, R. F. Dumpit, P. S. Nelson, B. Montgomery, J. S. McCune, S. R. Plymate, E. Y. Yu. A phase i study of niclosamide in combination with enzalutamide in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. PloS one. 13, e0198389 (2018). [↩]

- D. Zhao, C. Hu, Q. Fu, H. Lv. Combined chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer treatment by paclitaxel and niclosamide nanocrystals loaded thermosensitive hydrogel. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 167, 105992 (2021). [↩]

- W. Wei, H. Liu, J. Yuan, Y. Yao. Targeting wnt/β-catenin by anthelmintic drug niclosamide overcomes paclitaxel resistance in esophageal cancer. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 35, 165–173 (2021). [↩]

- G. Lohiya, D. S. Katti. A synergistic combination of niclosamide and doxorubicin as an efficacious therapy for all clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancers. 13, 3299 (2021). [↩]

- A. Wieland, D. Trageser, S. Gogolok, R. Reinartz, H. Höfer, M. Keller, A. Leinhaas, R. Schelle, S. Normann, L. Klaas, A. Waha, P. Koch, R. Fimmers, T. Pietsch, A. T. Yachnis, D. W. Pincus, D. A. Steindler, O. Brüstle, M. Simon, M. Glas, B. Scheffler. Anticancer effects of niclosamide in human glioblastoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 19, 4124–4136 (2013). [↩]

- O. Cerles, E. Benoit, C. Chéreau, S. Chouzenoux, F. Morin, M.-A. Guillaumot, R. Coriat, N. Kavian, T. Loussier, P. Santulli, L. Marcellin, N. E. B. Saidu, B. Weill, F. Batteux, C. Nicco. Niclosamide inhibits oxaliplatin neurotoxicity while improving colorectal cancer therapeutic response. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 16, 300–311 (2017). [↩]

- L. Yang, P. Shi, G. Zhao, J. Xu, W. Peng, J. Zhang, G. Zhang, X. Wang, Z. Dong, F. Chen, H. Cui. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 5, 8 (2020). [↩]

- X. Li, X. Yan, Y. Wang, B. Kaur, H. Han, J. Yu. The notch signaling pathway: a potential target for cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 16, 45 (2023). [↩]

- V. Venkatesh, R. Nataraj, G. S. Thangaraj, M. Karthikeyan, A. Gnanasekaran, S. B. Kaginelli, G. Kuppanna, C. G. Kallappa, K. M. Basalingappa. Targeting notch signalling pathway of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Investigation. 5, 5 (2018). [↩]

- D. Chu, Z. Zhang, Y. Zhou, W. Wang, Y. Li, H. Zhang, G. Dong, Q. Zhao, G. Ji. Notch1 and notch2 have opposite prognostic effects on patients with colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology. 22, 2440–2447 (2011). [↩]

- G. Dai, S. Deng, W. Guo, L. Yu, J. Yang, S. Zhou, T. Gao. Notch pathway inhibition using dapt, a γ-secretase inhibitor (gsi), enhances the antitumor effect of cisplatin in resistant osteosarcoma. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 58, 3–18 (2019). [↩]

- E. Patrad, A. Niapour, F. Farassati, M. Amani. Combination treatment of all-trans retinoic acid (atra) and γ-secretase inhibitor (dapt) cause growth inhibition and apoptosis induction in the human gastric cancer cell line. Cytotechnology. 70, 865–877 (2018). [↩]

- S. González, H. Uhm, S. X. Deng. Notch inhibition prevents differentiation of human limbal stem/progenitor cells in vitro. Scientific Reports. 9, 10373 (2019). [↩]

- S. Richter, P. L. Bedard, E. X. Chen, B. A. Clarke, B. Tran, S. J. Hotte, A. Stathis, H. W. Hirte, A. R. A. Razak, M. Reedijk, Z. Chen, B. Cohen, W.-J. Zhang, L. Wang, S. P. Ivy, M. J. Moore, A. M. Oza, L. L. Siu, E. McWhirter. A phase i study of the oral gamma secretase inhibitor r04929097 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced solid tumors (phl-078/ctep 8575). Investigational new drugs. 32, 243–249 (2014). [↩]

- I. Diaz-Padilla, H. Hirte, A. M. Oza, B. A. Clarke, B. Cohen, M. Reedjik, T. Zhang, S. Kamel-Reid, S. P. Ivy, S. J. Hotte, A. A. R. Razak, E. X. Chen, I. Brana, M. Wizemann, L. Wang, L. L. Siu, P. L. Bedard. A phase ib combination study of ro4929097, a gamma-secretase inhibitor, and temsirolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investigational new drugs. 31, 1182–1191 (2013). [↩]

- N. K. LoConte, A. R. A. Razak, P. Ivy, A. Tevaarwerk, R. Leverence, J. Kolesar, L. Siu, S. J. Lubner, D. L. Mulkerin, W. R. Schelman, D. A. Deming, K. D. Holen, L. Carmichael, J. Eickhoff, G. Liu. A multicenter phase 1 study of γ -secretase inhibitor ro4929097 in combination with capecitabine in refractory solid tumors. Investigational new drugs. 33, 169–176 (2015). [↩]

- S. M. Lee, J. Moon, B. G. Redman, T. Chidiac, L. E. Flaherty, Y. Zha, M. Othus, A. Ribas, V. K. Sondak, T. F. Gajewski, K. A. Margolin. Phase 2 study of ro4929097, a gamma-secretase inhibitor, in metastatic melanoma: swog 0933. Cancer. 121, 432–440 (2015). [↩]

- I. Diaz-Padilla, M. K. Wilson, B. A. Clarke, H. W. Hirte, S. A. Welch, H. J. Mackay, J. J. Biagi, M. Reedijk, J. I. Weberpals, G. F. Fleming, L. Wang, G. Liu, C. Zhou, C. Blattler, S. P. Ivy, A. M. Oza. A phase ii study of single-agent ro4929097, a gamma-secretase inhibitor of notch signaling, in patients with recurrent platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer: a study of the princess margaret, chicago and california phase ii consortia. Gynecologic oncology. 137, 216–222 (2015). [↩]

- V. M. Villalobos, F. Hall, A. Jimeno, L. Gore, K. Kern, R. Cesari, B. Huang, J. T. Schowinsky, P. J. Blatchford, B. Hoffner, A. Elias, W. Messersmith. Long-term follow-up of desmoid fibromatosis treated with pf-03084014, an oral gamma secretase inhibitor. Annals of surgical oncology. 25, 768–775 (2018). [↩]

- S. Kummar, G. O’Sullivan Coyne, K. T. Do, B. Turkbey, P. S. Meltzer, E. Polley, P. L. Choyke, R. Meehan, R. Vilimas, Y. Horneffer, L. Juwara, A. Lih, A. Choudhary, S. A. Mitchell, L. J. Helman, J. H. Doroshow, A. P. Chen. Clinical activity of the γ-secretase inhibitor pf-03084014 in adults with desmoid tumors (aggressive fibromatosis). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 35, 1561–1569 (2017). [↩]

- W. A. Messersmith, G. I. Shapiro, J. M. Cleary, A. Jimeno, A. Dasari, B. Huang, M. N. Shaik, R. Cesari, X. Zheng, J. M. Reynolds, P. A. English, K. R. McLachlan, K. A. Kern, P. M. LoRusso. A phase i, dose-finding study in patients with advanced solid malignancies of the oral γ-secretase inhibitor pf-03084014. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 21, 60–67 (2015). [↩]

- C. L. Hann, T. F. Burns, A. Dowlati, D. Morgensztern, P. J. Ward, M. M. Koch, C. Chen, C. Ludwig, M. Patel, H. Nimeiri, P. Komarnitsky, D. R. Camidge. A phase 1 study evaluating rovalpituzumab tesirine in frontline treatment of patients with extensive-stage sclc. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 16, 1582–1588 (2021). [↩]

- M. L. Johnson, Z. Zvirbule, K. Laktionov, A. Helland, B. C. Cho, V. Gutierrez, B. Colinet, H. Lena, M. Wolf, M. Gottfried, I. Okamoto, C. van der Leest, P. Rich, J.-Y. Hung, C. Appenzeller, Z. Sun, D. Maag, Y. Luo, C. Nickner, A. Vajikova, P. Komarnitsky, J. Bar. Rovalpituzumab tesirine as a maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage-sclc: results from the phase 3 meru study. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 16, 1570–1581 (2021). [↩]

- M. J. McKeage, D. Kotasek, B. Markman, M. Hidalgo, M. J. Millward, M. B. Jameson, D. L. Harris, R. J. Stagg, A. M. Kapoun, L. Xu, B. G. M. Hughes. Phase ib trial of the anti-cancer stem cell dll4-binding agent demcizumab with pemetrexed and carboplatin as first-line treatment of metastatic non-squamous nsclc. Targeted oncology. 13, 89–98 (2018). [↩]

- D. C. Smith, P. D. Eisenberg, G. Manikhas, R. Chugh, M. A. Gubens, R. J. Stagg, A. M. Kapoun, L. Xu, J. Dupont, B. Sikic. A phase i dose escalation and expansion study of the anticancer stem cell agent demcizumab (anti-dll4) in patients with previously treated solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 20, 6295–6303 (2014). [↩]

- R. L. Coleman, K. F. Handley, R. Burger, G. Z. D. Molin, R. Stagg, A. K. Sood, K. N. Moore. Demcizumab combined with paclitaxel for platinum-resistant ovarian, primary peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancer: the sierra open-label phase ib trial. Gynecologic oncology. 157, 386–391 (2020). [↩]

- D. C. Smith, P. D. Eisenberg, G. Manikhas, R. Chugh, M. A. Gubens, R. J. Stagg, A. M. Kapoun, L. Xu, J. Dupont, B. Sikic. A phase i dose escalation and expansion study of the anticancer stem cell agent demcizumab (anti-dll4) in patients with previously treated solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 20, 6295–6303 (2014). [↩]