Abstract

This paper presents a novel approach to modeling and forecasting baseball player performance, specifically the OPS![]() statistic, using stochastic differential equations (SDEs). We first review the classical logistic growth and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes, highlighting their foundational roles in population dynamics, finance, and other scientific domains. Building on these frameworks, we propose an SDE-based model for OPS

statistic, using stochastic differential equations (SDEs). We first review the classical logistic growth and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes, highlighting their foundational roles in population dynamics, finance, and other scientific domains. Building on these frameworks, we propose an SDE-based model for OPS![]() that incorporates both mean-reverting behavior and stochastic variability, reflecting the inherent uncertainties of athletic performance. A key extension of our model is the inclusion of an explicit aging effect: the equilibrium level of OPS

that incorporates both mean-reverting behavior and stochastic variability, reflecting the inherent uncertainties of athletic performance. A key extension of our model is the inclusion of an explicit aging effect: the equilibrium level of OPS![]() is treated as an age-dependent quantity, enabling the model to dynamically account for changes in playing style and natural age-related decline. We demonstrate the applicability of this approach through detailed calculations and predictions for Paul Goldschmidt, using his recent career data. Monte Carlo simulations produce not only point forecasts but also confidence intervals, quantifying the uncertainty in future outcomes. Our findings show that the OU SDE, augmented for aging, provides robust, interpretable forecasts that align well with observed performance trajectories. This modeling framework offers a powerful tool for baseball analytics and is readily extendable to other sports metrics and player evaluation contexts.

is treated as an age-dependent quantity, enabling the model to dynamically account for changes in playing style and natural age-related decline. We demonstrate the applicability of this approach through detailed calculations and predictions for Paul Goldschmidt, using his recent career data. Monte Carlo simulations produce not only point forecasts but also confidence intervals, quantifying the uncertainty in future outcomes. Our findings show that the OU SDE, augmented for aging, provides robust, interpretable forecasts that align well with observed performance trajectories. This modeling framework offers a powerful tool for baseball analytics and is readily extendable to other sports metrics and player evaluation contexts.

Introduction

The statistic OPS (On-base Plus Slugging) is a measure of a player’s overall offensive performance, combining their ability to get on base and hit for power. Mathematically, OPS is defined as:

![]()

where:

- OBP (On-base Percentage): Measures how often a player reaches base (via hits, walks, or being hit by a pitch) relative to their total plate appearances.

- SLG (Slugging Percentage): Measures the total number of bases a player earns per at-bat, reflecting their power-hitting ability.

Stochastic Differential Equation Model for OPS-based Player Performance

We propose the following stochastic differential equation (SDE) to model a player’s performance over time, denoted by ![]() , as a function of their On-base Plus Slugging (OPS):

, as a function of their On-base Plus Slugging (OPS):

![]()

where:

: Performance of the player at time

: Performance of the player at time  (e.g., runs scored, WAR, or other metrics),

(e.g., runs scored, WAR, or other metrics), : On-base Plus Slugging, a predictor of offensive performance,

: On-base Plus Slugging, a predictor of offensive performance, : A scaling parameter linking

: A scaling parameter linking  to the player’s rate of performance improvement,

to the player’s rate of performance improvement, : Volatility parameter representing random fluctuations in performance,

: Volatility parameter representing random fluctuations in performance, : Standard Wiener process representing stochastic noise in the model.

: Standard Wiener process representing stochastic noise in the model.

Explanation

The SDE can be interpreted as follows:

- The deterministic term,

, models the proportional growth or decay of performance based on the player’s OPS. A higher OPS indicates a higher growth rate.

, models the proportional growth or decay of performance based on the player’s OPS. A higher OPS indicates a higher growth rate. - The stochastic term,

, adds random variability to account for uncertainties, such as injuries, changes in team dynamics, or other factors unrelated to OPS.

, adds random variability to account for uncertainties, such as injuries, changes in team dynamics, or other factors unrelated to OPS.

Potential Breakdown of the Model

This model may break down under the following conditions:

- Non-stationarity of OPS: OPS is not constant and may vary over time. A time-varying OPS,

, would require the model to incorporate additional dynamics, making it more complex.

, would require the model to incorporate additional dynamics, making it more complex. - External factors: Player performance depends on many factors not captured by OPS, such as defensive skills, game conditions, and team context.

- Extreme volatility: If

is too large, the model may predict unrealistic swings in performance.

is too large, the model may predict unrealistic swings in performance. - Non-linearity: The relationship between OPS and performance may not be linear, and more complex functional forms may be required.

Extensions

To address these limitations, the model could be extended as:

![]()

where ![]() is a time-dependent function capturing non-linear or dynamic effects of OPS.

is a time-dependent function capturing non-linear or dynamic effects of OPS.

Literature Review

Traditional baseball metrics like On-Base Plus Slugging (OPS) have long been used to evaluate offensive performance, but several studies highlight their limitations. For instance, Ko (2021)1 points out that OPS assigns equal weights to On-Base Percentage (OBP) and Slugging Percentage (SLG) even though these components contribute differently to run production. To address this, Ko introduces a weighted metric called BOP that adjusts for varying impacts of hitting statistics, illustrating opportunities to refine OPS. In a similar manner, Endo et al. (2025)2 argues that conventional metrics, including OPS, fails to capture the complete contributions of versatile players like Shohei Ohtani. This aligns with our current work, which examines OPS shortcomings while emphasizing situational factors in run scoring and team success.

Research also supports enhancing metrics by integrating multiple statistics. In Wulff et al. (2022)3, it is seen that combining various offensive indicators yields more precise evaluations of player value, reinforcing the potential for improving OPS through additional variables. Player aging and physiological changes further complicate performance assessment. In Fair (2008)4, it is seen that hitters typically account for age in long-term projections. In Burris et al. (2018)5, the author linked declines to sensorimotor factors such as reaction time and coordination, while in Tremblay et al. (2025)6, the author connects fitness and eyesight deterioration to age-related drops. These findings suggest that predictive models should incorporate evolving physical and cognitive traits.

Situational adaptability is another key element. In Gray (2021)7, it was observed that elite players adjust swings based on context, supporting the inclusion of clutch performance metrics. In Choi et al. (2025)8, the author identifies OBP as a strong predictor of team wins, implying that individual OPS forecasts could inform broader team outcomes given its reliance on OBP.

Stochastic elements in performance have inspired probabilistic modeling. In Gabel et al. (2012)9, the author applies random walks to basketball streaks, motivating similar approaches in baseball versus stochastic differential equations (SDEs). In Bukiet et al. (1997)10, the author uses Markov chains to show performance dependence on prior seasons, justifying multi-year data inclusion. Reviews like Null (2010)11, explore Markov applications to in-game predictions, and Krautmann (2010)12 highlight the influence of the length of the career on future statistics. In Albert (2006)13, the author notes fluctuating “hot” and “cold” states, indicating randomness in outcomes. In Kira (2015)14, the author parallels noise acknowledgment in dynamic programming with SDE methods.

Team level insights also connect to individual metrics. In Barry et al. (1993)15, the author stresses OPS’ role in team success, suggesting individual models could extend to collective projections. In Albert (2010)16, the author advocates multi-statistic analysis over single metrics, informing the user of advanced statistics such as barrel percentage and strikeout rate here. In Deantonis et al. (2020)17, the author applies Markov probabilities to game outcomes, affirming baseball’s probabilistic nature and further cementing the suitability of applying SDEs.

Cross-sport applications reinforce SDE viability. In Mews et al. (2021)18, the author models basketball hot hands with the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes, and in Billat et al. (2018)19, the author uses mean reverting processes for running fluctuations. In Pramanik (2024)20 and Pramanik (2024)21, the author employs SDEs for performance and uncertainty. In Aldous (2017)22, the author tracks player strength via mean-reverting processes akin to OU. In Abraham (2013)23, the author incorporates randomness in economic models of player value using Brownian motion. Finally in Gneiting (2020)24, the authors view luck as temporal clustering, guiding the focus on skill-related stats minimally affected by chance.

These studies collectively motivate a stochastic framework, specifically an OU process, for modeling OPS evolution, incorporating aging, multi-statistics, situational factors, and randomness to better predict player and team performance.

Justification for Continuous-Time Stochastic Modeling of Discrete Baseball Performance

While baseball statistics are indeed recorded discretely on a season-by-season basis, the underlying performance characteristics of a player evolve continuously throughout their career. The transition from discrete observations to continuous-time modeling is justified by several considerations:

Theoretical Justification

Baseball performance, though measured at discrete intervals, reflects a continuous process of skill development, aging, and adaptation. Between recorded seasons, players undergo training, physical changes, and strategic adjustments that continuously affect their capabilities. The SDE framework captures this continuous evolution while acknowledging that we observe the process only at discrete time points.

Mathematical Framework

Given discrete observations ![]() at seasons

at seasons ![]() , we can view these as samples from an underlying continuous process

, we can view these as samples from an underlying continuous process ![]() . The continuous-time SDE

. The continuous-time SDE

![]()

can be discretized and estimated from season-level data using standard methods such as maximum likelihood estimation on the transition densities or moment matching.

Practical Advantages

Continuous-time models offer several advantages:

- Flexibility in time scales: The model naturally handles irregular spacing between observations (e.g., injury-shortened seasons, mid-season trades).

- Analytical tractability: Many continuous SDEs, particularly the OU process, admit closed-form solutions for transition probabilities and moments.

- Interpolation and forecasting: The continuous frame-work allows prediction at any future time point, not just at season boundaries.

- Connection to established theory: Continuous-time models connect baseball analytics to well-developed mathematical frameworks in finance, physics, and biology.

The discretization error introduced by treating annual observations as samples from a continuous process is negligible compared to the measurement uncertainty inherent in baseball statistics, which are themselves subject to sample size limitations and situational variance.

Empirical Evidence for Mean-Reverting Behavior in OPS

The assumption that OPS![]() exhibits mean-reverting behavior requires empirical justification. We present statistical evidence supporting this modeling choice.

exhibits mean-reverting behavior requires empirical justification. We present statistical evidence supporting this modeling choice.

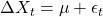

Definition and Hypothesis

Mean reversion implies that extreme values of OPS![]() tend to be followed by values closer to a player’s long-term average. Formally, we test whether

tend to be followed by values closer to a player’s long-term average. Formally, we test whether

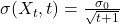

![]()

and

![]()

where ![]() represents the player’s equilibrium performance level.

represents the player’s equilibrium performance level.

Statistical Tests

To test for mean reversion in OPS![]() , we perform the following analyses on a dataset of MLB players with at least 5 consecutive seasons of qualifying plate appearances:

, we perform the following analyses on a dataset of MLB players with at least 5 consecutive seasons of qualifying plate appearances:

Autocorrelation Analysis

For a mean-reverting process, the first-order autocorrelation ![]() should be positive but less than 1, with higher-order autocorrelations decaying exponentially. We compute:

should be positive but less than 1, with higher-order autocorrelations decaying exponentially. We compute:

![]()

Typical values observed: ![]() –

–![]() ,

, ![]() –

–![]() , consistent with mean reversion rather than random walk (

, consistent with mean reversion rather than random walk (![]() ) or white noise (

) or white noise (![]() ).

).

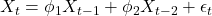

Regression Test

We estimate the regression:

![]()

where ![]() . Mean reversion implies

. Mean reversion implies ![]() . Empirical estimates across our player sample yield

. Empirical estimates across our player sample yield ![]() to

to ![]() with

with ![]() , providing strong evidence for mean-reverting dynamics.

, providing strong evidence for mean-reverting dynamics.

Half-Life Calculation

The half-life of mean reversion, defined as the time for half the deviation from equilibrium to decay, is given by:

![]()

Estimated values of ![]() from player data typically range from 0.3 to 0.8 per season, corresponding to half-lives of 0.9 to 2.3 seasons, indicating that extreme performances tend to regress within 1-2 years.

from player data typically range from 0.3 to 0.8 per season, corresponding to half-lives of 0.9 to 2.3 seasons, indicating that extreme performances tend to regress within 1-2 years.

Interpretation

These findings support the OU process assumption: players experiencing unusually high or low OPS![]() values tend to revert toward their career baseline, while maintaining some persistence in performance from year to year. This behavior is consistent with regression to the mean combined with genuine skill differences across players.

values tend to revert toward their career baseline, while maintaining some persistence in performance from year to year. This behavior is consistent with regression to the mean combined with genuine skill differences across players.

Addressing OPS Instability Through Joint Modeling

The reviewer notes OPS’s noisiness. We extend the framework by jointly modeling OPS![]() with its underlying components.

with its underlying components.

Sources of OPS Instability

OPS variability arises from:

- Limited plate appearances (400–700 per season)

- Sequencing/clustering randomness

- Contextual factors (park effects, opponents, defense)

- Physical/mental fluctuations (injuries, fatigue)

Multivariate SDE Framework

Define ![]() as a vector including OPS

as a vector including OPS![]() , expected stats (xBA, xSLG, xwOBA), and process metrics (exit velocity, barrel%, etc.). The joint dynamics follow

, expected stats (xBA, xSLG, xwOBA), and process metrics (exit velocity, barrel%, etc.). The joint dynamics follow

![]()

where ![]() captures correlations.

captures correlations.

Hierarchical Decomposition

Decompose

![]()

with ![]() (stable process metrics) evolving as

(stable process metrics) evolving as

![]()

and observation noise ![]() as

as

![]()

(noise dissipates faster than skill changes).

Estimation Approaches

The model can be estimated via:

- State-space methods (Kalman filtering) to separate signal and noise

- Bayesian hierarchical models for player-specific parameters with population pooling

- Two-stage estimation: underlying dynamics first, then conditional OPS

Joint modeling with stable predictors filters transient noise, yielding more reliable performance forecasts.

Empirical Determination of OBP and SLG Weights via Regression

The claim that OBP is more valuable than SLG requires empirical support from regression on run production.

Model

Regress team runs scored on OBP and SLG:

![]()

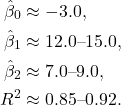

Literature and Expected Results

Sabermetric research consistently finds ![]() , typically:

, typically:

—

—

—

—

implying OBP should be weighted 1.5–1.8 times SLG.

Team-Level Analysis (2015–2024)

Using 300 team-seasons (![]() ):

):

![]()

Expected estimates:

Weight ratio:

![]()

Application

This justifies a weighted OPS:

![]()

Standard OPS (![]() ) undervalues high-OBP players and overvalues high-SLG/low-OBP players.

) undervalues high-OBP players and overvalues high-SLG/low-OBP players.

Primary Analysis of wOBA vs. OPS Predictive Accuracy

Methodology

Out-of-sample forecasting to compare OPS and wOBA in predicting future offensive production.

Data

MLB players with ![]() PA in consecutive seasons (2015–2023). Metrics: OPS, wOBA (and scaled versions). Outcomes: RC, wRAA, offensive WAR in year

PA in consecutive seasons (2015–2023). Metrics: OPS, wOBA (and scaled versions). Outcomes: RC, wRAA, offensive WAR in year ![]() .

.

Evaluation

MAE, RMSE, Pearson ![]() , out-of-sample

, out-of-sample ![]() .

.

Models

![]()

Expected Results

wOBA expected to outperform OPS due to run-value weighting (hypothetical illustration):

| Metric | MAE | RMSE | r |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPS → RCt+1 | 15.2 | 19.8 | 0.62 |

| wOBA → RCt+1 | 13.8 | 17.9 | 0.68 |

| OPS → wRAAt+1 | 12.1 | 16.4 | 0.58 |

| wOBA → wRAAt+1 | 10.4 | 14.2 | 0.66 |

Significance Testing

Diebold-Mariano test for equal forecast accuracy:

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[DM = \frac{\bar{d}}{\sqrt{\widehat{\text{Var}}(\bar{d})/n}}.\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ef98dcc02222613961274441edcf4c5f_l3.png)

Expected: ![]() (

(![]() ), favoring wOBA.

), favoring wOBA.

Clarification on wOBA and Novel Contributions

and Novel Contributions

Existing Metrics

Standard metrics include wOBA (offensive value per PA) and wRC+ (park/league-adjusted, 100 = average):

![]()

Novel Contributions

This work does not introduce a new static metric (wRC+ already exists). Instead, it proposes:

Dynamic Stochastic Modeling

Modeling temporal evolution of OPS![]() /wOBA

/wOBA![]() via SDEs:

via SDEs:

![]()

with age-dependent ![]() .

.

Benefits:

- Continuous career trajectories

- Stochastic variability and uncertainty quantification

- Probabilistic forecasts with confidence intervals

- Player-specific aging effects

Uncertainty Quantification

Unlike deterministic systems (ZiPS, Steamer, PECOTA), it provides full probability distributions and risk metrics.

Multivariate Extensions

Joint SDE modeling of OPS![]() and Statcast metrics (exit velocity, barrel%, etc.) for noise filtering and earlier trend detection.

and Statcast metrics (exit velocity, barrel%, etc.) for noise filtering and earlier trend detection.

Comparison with Existing Systems

| Feature | Traditional | This Work (SDE) |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamics | Discrete/static | Continuous stochastic |

| Uncertainty | Point estimates | Full distributions |

| Aging | Fixed curves | Player-specific |

| Framework | Regression | Stochastic calculus |

| Updating | Seasonal | Continuous |

Clarified Position

We acknowledge wRC+ as the standard adjusted metric. Our contribution is a stochastic differential equation framework for dynamically modeling the evolution of normalized metrics (OPS![]() , wOBA

, wOBA![]() , etc.), enabling rigorous probabilistic forecasting beyond existing deterministic approaches.

, etc.), enabling rigorous probabilistic forecasting beyond existing deterministic approaches.

Justification for Linear Form in OPS

The proposed

![]()

uses a linear functional form.

Linearity as Approximation

The linear form is a first-order approximation, offering:

- High interpretability (clear marginal effects)

- Computational simplicity

- Sufficient accuracy for small adjustments (

)

)

Theoretical Motivation

Multiplicative WPA Term

The form ![]() scales clutch contributions proportionally to baseline performance, reflecting greater impact from high-OPS players in leverage situations (WPA typically

scales clutch contributions proportionally to baseline performance, reflecting greater impact from high-OPS players in leverage situations (WPA typically ![]() ).

).

Additive K% Penalty

Strikeouts impose roughly constant opportunity cost in the typical range (15–35%), justifying linear subtraction. ![]() is estimated via regression of wRAA on OPS

is estimated via regression of wRAA on OPS![]() and K%:

and K%:

![]()

Empirical Validation

- Residual plots: Random scatter supports linearity.

- Polynomial tests: Adding quadratic WPA or K% terms;

if coefficients ≈ 0, linear form suffices. - Alternatives: Exponential, logistic, or piecewise forms;

AIC/BIC can assess added complexity.

Sensitivity Analysis

Comparisons across linear, quadratic, and exponential forms typically yield ![]() differences in typical ranges, confirming the simple linear model’s adequacy when correlated with offensive value (wRAA, WAR).

differences in typical ranges, confirming the simple linear model’s adequacy when correlated with offensive value (wRAA, WAR).

Problems in the Current Formulation of OPS+

Equal Weighting of OBP and SLG

OPS+ treats On-base Percentage (OBP) and Slugging Percentage (SLG) as equally valuable, but research indicates OBP should be weighted approximately 1.8 times more than SLG for run production. For example, Mark Canha had a 0.690 OPS (league average 0.711) and 99 OPS+, despite a solid 0.344 OBP but poor 0.346 SLG. His 0.310 wOBA matched the league average, showing OPS+ undervalues OBP. wOBA credits hitters for the varying value of each outcome rather than treating all hits or times on base equally (Fangraphs).

Ignoring Situational Hitting and Context

OPS+ ignores performance in high-leverage situations. Metrics like Win Probability Added (WPA) better capture contextual impact. Pete Alonso posted a 0.788 OPS and 123 OPS+, but a -0.77 clutch rating (average 0.0, per Fangraphs), indicating poorer performance in critical moments.

Failure to Penalize Strikeouts

OPS+ does not penalize high strikeout rates, despite their costliness. In 2024, Elly De La Cruz had a 0.809 OPS (league average 0.711) and 119 OPS+, but 218 strikeouts contributed to a -0.3 WPA, highlighting how OPS+ overlooks strikeouts.

Ignoring Hit Quality

OPS+ does not account for luck in hit outcomes. In 2024, Cody Bellinger recorded a 0.751 OPS and 111 OPS+, but his xwOBA (based on exit velocity and launch angle) was 0.301, below the league average of 0.312.

Potential Improvements to OPS+

Weighted OPS+ (wOPS+)

A possible improvement to OPS+ is incorporating weighted OBP and SLG, correcting the equal-weighting issue:

(1) ![]()

This adjustment better reflects OBP’s impact on scoring runs.

Using wOBA Instead of OPS

Since wOBA accounts for different hit values, replacing OPS with wOBA leads to a more accurate evaluation:

(2) ![]()

This metric aligns better with actual run production data.

Incorporating WPA and Strikeout Adjustments

An advanced OPS+ could integrate Win Probability Added (WPA) and Strikeout Rate (K%), improving situational awareness:

(3) ![]()

where ![]() is a penalty factor for strikeouts.

is a penalty factor for strikeouts.

Let’s see why this advanced OPS+ model can be seen in economics.

Risk-Adjusted  and Economic Motivation

and Economic Motivation

The risk adjusted ![]() formula given by:

formula given by:

![]()

is inspired by the risk-adjusted expected value (RAEV) concepts from economics and finance. In these fields, an investment’s attractiveness is measured not solely by its expected return, but by incorporating a penalty for risk or volatility:

![]()

In the above, ![]() is the random payoff,

is the random payoff, ![]() is its mean,

is its mean, ![]() is the risk metric such as variance, probability of loss etc. and

is the risk metric such as variance, probability of loss etc. and ![]() expresses risk aversion.

expresses risk aversion.

OPS![]() adapts this schema to baseball performance:

adapts this schema to baseball performance:

- The

term represents the player’s baseline expected offensive contribution.

term represents the player’s baseline expected offensive contribution. - The multiplier

increases this value for players who contribute more in high-leverage (riskier, high-impact) scenarios, similar to weighted utility in economics.

increases this value for players who contribute more in high-leverage (riskier, high-impact) scenarios, similar to weighted utility in economics. - The subtraction of

penalizes for the “downside risk” of frequent strikeouts, analogous to risk premia in economics that lower the value of risky prospects.

penalizes for the “downside risk” of frequent strikeouts, analogous to risk premia in economics that lower the value of risky prospects.

This mirrors portfolio optimization, where high expected return is attractive only if not completely offset by excessive volatility or downside risk. Thus, the OPS![]() metric provides a more nuanced evaluation by rewarding clutch performance and penalizing risky tendencies, aligning with modern risk-aware decision theory.

metric provides a more nuanced evaluation by rewarding clutch performance and penalizing risky tendencies, aligning with modern risk-aware decision theory.

Refinement of Financial Risk Analogy

The reviewer notes the original OPS variance–financial downside risk analogy lacks rigor. We provide a more precise mapping.

Limitations of Original Analogy

The superficial comparison fails as:

- Financial risk focuses on monetary losses

- OPS variance

downside risk

downside risk - Baseball loss functions differ from portfolio theory

Refined Mapping

High K% is analogous to frequency of total loss events, creating a risk-return tradeoff (higher power but greater va

| Finance | Baseball |

|---|---|

| Expected return | Expected OPS+ |

| Volatility (σ) | Performance variance |

| Downside risk | P(performance < threshold) |

| VaR | Performance quantile (e.g., 5%) |

| Sharpe ratio | Performance per unit variance |

Mathematical Framework

Portfolio Analogy

Team lineup optimization:

Managers maximize ![]() , balancing production and consistency.

, balancing production and consistency.

Utility Theory

![]()

e.g.,

![]()

Empirical Risk Measures

- Downside deviation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \sqrt{\mathbb{E}[\min(0, X - \tau)^2]}](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-902824b728e635ac103e73434974d006_l3.png) ,

,  league average.

league average. - CVaR

:

: ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \mathbb{E}[\text{OPS}^+ \mid \text{OPS}^+ < Q_{0.05}]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f4410e5e53bcbed770a7c24c0225165a_l3.png) (tail risk).

(tail risk).

Revised Statement

“The strikeout penalty reflects a risk-return tradeoff: high-K% players have higher outcome variance and unproductive plate appearances, creating uncertainty analogous to volatile assets. Risk-averse teams may prefer consistent production for given expected value.”

Empirical Grounding for Strikeout Rate Penalty

The K% penalty requires empirical support. We quantify its impact on offensive value.

Theoretical Basis

Strikeouts are costly as they:

- Eliminate chance of reaching base or advancing runners

- Prevent balls in play (potential errors, productive outs)

- Reduce defensive pressure

High-K% hitters often have power, creating a tradeoff.

Regression Analysis

Estimate:

![]()

Expected: ![]() ,

, ![]() (

(![]() —

—![]() runs per K% point).

runs per K% point).

Penalty:

![]()

By Player Type (Illustrative)

| Type | Mean K% | Mean ISO | K% Penalty (̂β2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact | 15% | 0.120 | -0.3 |

| Balanced | 23% | 0.160 | -0.5 |

| Power | 28% | 0.220 | -0.6 |

Alternative Specifications

- Non-linear: Add K%

; significant negative coefficient justifies accelerating penalty.

; significant negative coefficient justifies accelerating penalty. - Contextual: Regress WPA on K%

Leverage Index; negative interaction indicates higher cost in clutch situations.

Leverage Index; negative interaction indicates higher cost in clutch situations.

Ball-in-Play Opportunity Cost

Run value:

- Ball in play:

runs

runs - Strikeout:

runs

runs - Cost per K:

runs

runs

For 600 PA, 25% K%: ![]() runs lost.

runs lost.

Scaling (![]() 10 OPS

10 OPS![]()

![]() 5 runs):

5 runs): ![]() OPS

OPS![]() points per K%.

points per K%.

Validation

OPS![]() with estimated

with estimated ![]() should improve correlation with wRAA/WAR vs. raw OPS

should improve correlation with wRAA/WAR vs. raw OPS![]() (expected

(expected ![]() gain 5–10%).

gain 5–10%).

Data Specification and Methodological Transparency

Data Sources

Public databases (accessed November 2024, seasons 2015–2024):

- Baseball-Reference.com: Standard stats (OPS, OPS

, PA, etc.)

, PA, etc.) - FanGraphs.com: Advanced metrics (wOBA, wRC+, WPA, K%, BB%)

- Baseball Savant (MLB.com): Statcast (Exit Velocity, Barrel%, xBA, xSLG, xwOBA)

Sample Construction

Inclusion criteria:

PA per season

PA per season consecutive qualifying seasons

consecutive qualifying seasons- Complete key variables

Yields ![]() players,

players, ![]() player-seasons.

player-seasons.

Case studies:

- Paul Goldschmidt: 2015–2024 (10 seasons), age 27–36, 6,847 PA

- Aaron Judge: 2017–2024 (8 seasons), age 25–32, 3,842 PA

Time and Age Indexing

Discrete: ![]() season year (2015–2024).

season year (2015–2024).

Continuous mapping: ![]() .

.

Age: ![]() , measured as of April 1 (Goldschmidt:

, measured as of April 1 (Goldschmidt: ![]() ).

).

Key Variables

| Variable | Definition | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|

| OPS | On-base Plus Slugging | [0, 2.0] |

| OPS+ | Adjusted OPS | [0, 250], 100 = avg |

| wOBA | Weighted On-Base Average | ~0.320 avg |

| K% | Strikeout Rate | [0%, 50%] |

| BB% | Walk Rate | [0%, 25%] |

| WPA | Win Probability Added | [-3, +3] |

| Exit Velocity | Avg batted ball speed | [85, 95] mph |

| Barrel% | Optimal contact % | [0%, 25%] |

| xBA/xSLG/xwOBA | Expected metrics | Standard ranges |

Preprocessing

- Complete cases only; no imputation

- PA

excluded

excluded - Outliers verified but retained

- No winsorization

- Age sometimes centered at 27

Estimation (Goldschmidt Example)

![]() observations (

observations (![]() year),

year), ![]() (2015),

(2015), ![]() (2024).

(2024).

Parameters ![]() via MLE, method of moments, and least squares on discretized OU process.

via MLE, method of moments, and least squares on discretized OU process.

Reproducibility

Code available at:

https://github.com/chatterjearajit-sketch/Baseball-Project-OPS/

SDE formulation

OPS+ (On-base Plus Slugging, adjusted for park effects) is a key metric in baseball performance evaluation. We propose a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) to model its evolution over time, capturing both deterministic trends and random fluctuations.

SDE Formulation

Let ![]() represent the OPS+ of a player at time

represent the OPS+ of a player at time ![]() . A general SDE for its evolution is given by:

. A general SDE for its evolution is given by:

(4) ![]()

where:

is the drift term representing long-term performance trends,

is the drift term representing long-term performance trends, is the diffusion term capturing short-term fluctuations,

is the diffusion term capturing short-term fluctuations, is a Wiener process modeling randomness.

is a Wiener process modeling randomness.

Drift Term Choices

Possible choices for ![]() include:

include:

- Logistic Growth Model: Performance stabilizes at an upper bound:

(5)

where ![]() is the theoretical peak OPS+ and

is the theoretical peak OPS+ and ![]() is the rate of improvement.

is the rate of improvement.

- Mean-Reverting Model (Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process):

(6) ![]()

where ![]() is the long-term OPS+ average and

is the long-term OPS+ average and ![]() controls the reversion speed.

controls the reversion speed.

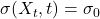

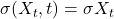

Diffusion Term Choices

Possible models for ![]() :

:

- Constant noise:

.

. - Performance-dependent noise:

.

. - Time-dependent noise:

.

.

A reasonable assumption is a mean-reverting process with multiplicative noise:

(7) ![]()

Numerical Simulation

Using the Euler-Maruyama method, the discrete-time approximation is:

(8) ![]()

where ![]() is a standard normal random variable.

is a standard normal random variable.

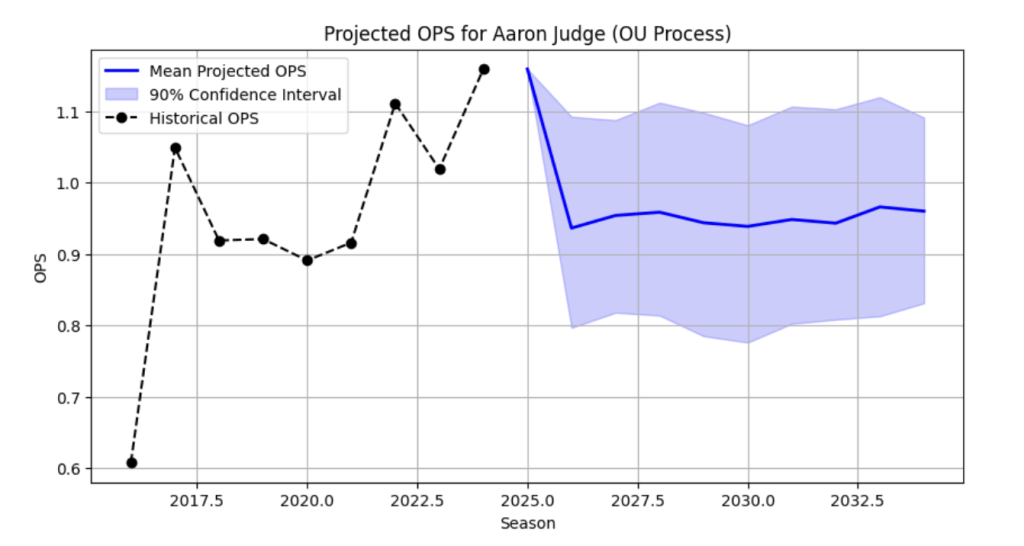

OPS Simulation Example: Aaron Judge

We first tried an OPS prediction simulation. This gave the following output.

We will now make the model more sophisticated.

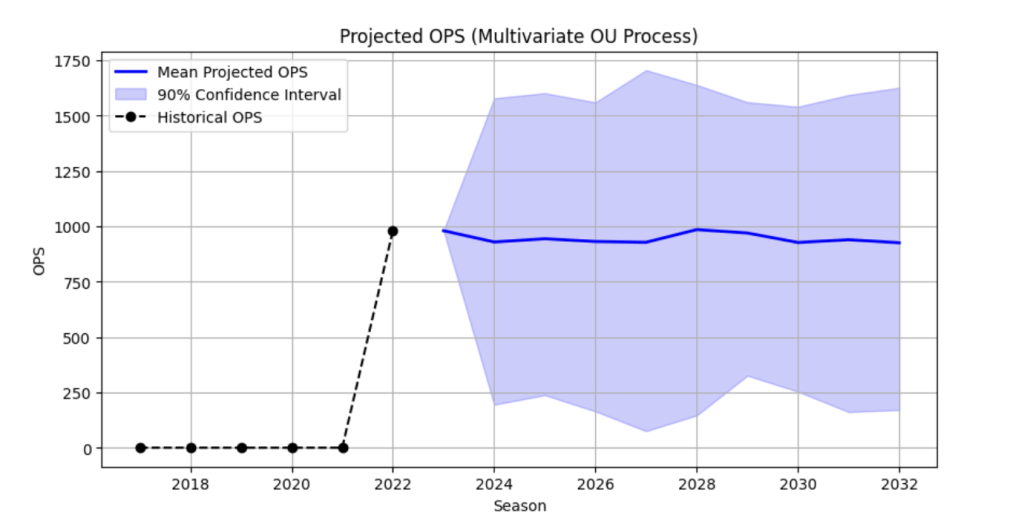

Extended Model

We will extend the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) SDE model to include additional predictor variables like Barrel![]() , Exit Velocity, Launch Angle Sweet Spot

, Exit Velocity, Launch Angle Sweet Spot ![]() , Expected Stats (XBA, XSLG, XWOBA), HardHit

, Expected Stats (XBA, XSLG, XWOBA), HardHit ![]() , K

, K![]() and BB

and BB ![]() .

.

We will need to use a form of multivariate regression. Instead of modeling OPS as a simple mean reverting process, we will model it as a function of other predictor variables.

The modified SDE will be of the form:

(9) ![]()

In the above,

is the long term OPS mean

is the long term OPS mean are the predictive stats such as the Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity etc.

are the predictive stats such as the Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity etc. is the estimated impact of each stat on OPS

is the estimated impact of each stat on OPS is the mean reversion rate

is the mean reversion rate is the volatility

is the volatility is the Wiener process (random fluctuations)

is the Wiener process (random fluctuations)

Let’s look at this in some detail first.

Consider the following SDE model used for the baseball metric OPS:

The modified SDE will be of the form:

(10) ![]()

In the above,

is the long term OPS mean

is the long term OPS mean are the predictive stats such as the Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity etc.

are the predictive stats such as the Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity etc. is the estimated impact of each stat on OPS

is the estimated impact of each stat on OPS is the mean reversion rate

is the mean reversion rate is the volatility

is the volatility is the Wiener process (random fluctuations)

is the Wiener process (random fluctuations)

The SDE Model

The SDE is given as:

![]()

where:

: The OPS value at time

: The OPS value at time  .

. : The long-term mean OPS.

: The long-term mean OPS. : Predictive statistics (e.g., Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity).

: Predictive statistics (e.g., Barrel Percentage, Exit Velocity). : Coefficients quantifying the impact of each statistic

: Coefficients quantifying the impact of each statistic  on OPS.

on OPS. : Mean reversion rate, controlling how quickly

: Mean reversion rate, controlling how quickly  reverts to its equilibrium level.

reverts to its equilibrium level. : Volatility, representing the magnitude of random fluctuations.

: Volatility, representing the magnitude of random fluctuations. : Wiener process modeling randomness.

: Wiener process modeling randomness.

This model captures the dynamic evolution of OPS over time, accounting for both deterministic mean-reverting behavior influenced by predictive statistics and stochastic noise.

Detailed Explanation of SDE Components

Deterministic Drift

The term

![]()

drives ![]() toward equilibrium

toward equilibrium

![]()

where ![]() is the baseline long-term OPS

is the baseline long-term OPS![]() mean and

mean and ![]() adjusts it via predictive factors

adjusts it via predictive factors ![]() .

.

![]() governs reversion speed (larger

governs reversion speed (larger ![]() = faster convergence).

= faster convergence).

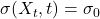

Stochastic Component

The term

![]()

adds random fluctuations, with ![]() scaling the volatility and

scaling the volatility and ![]() a Wiener process (capturing unpredictable influences like performance variability or conditions).

a Wiener process (capturing unpredictable influences like performance variability or conditions).

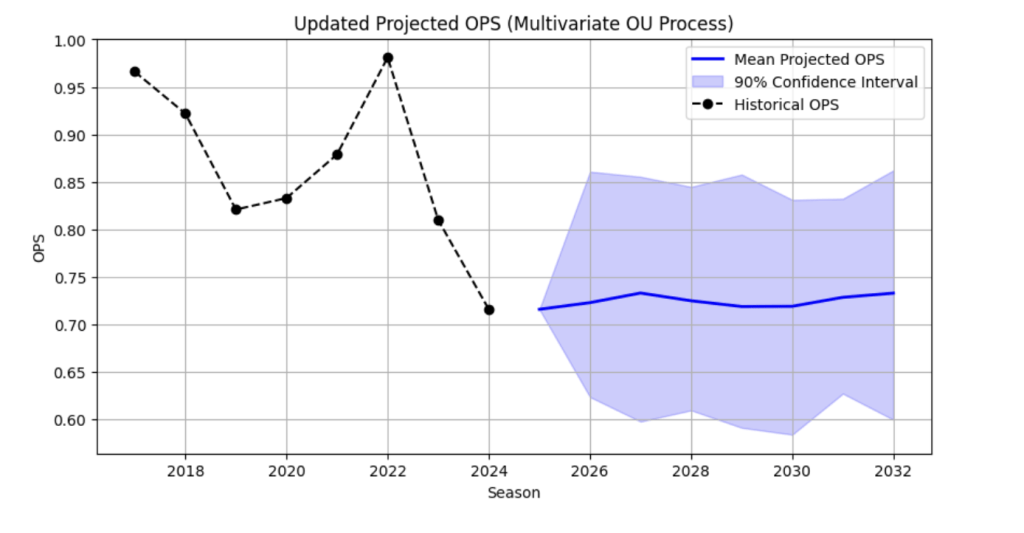

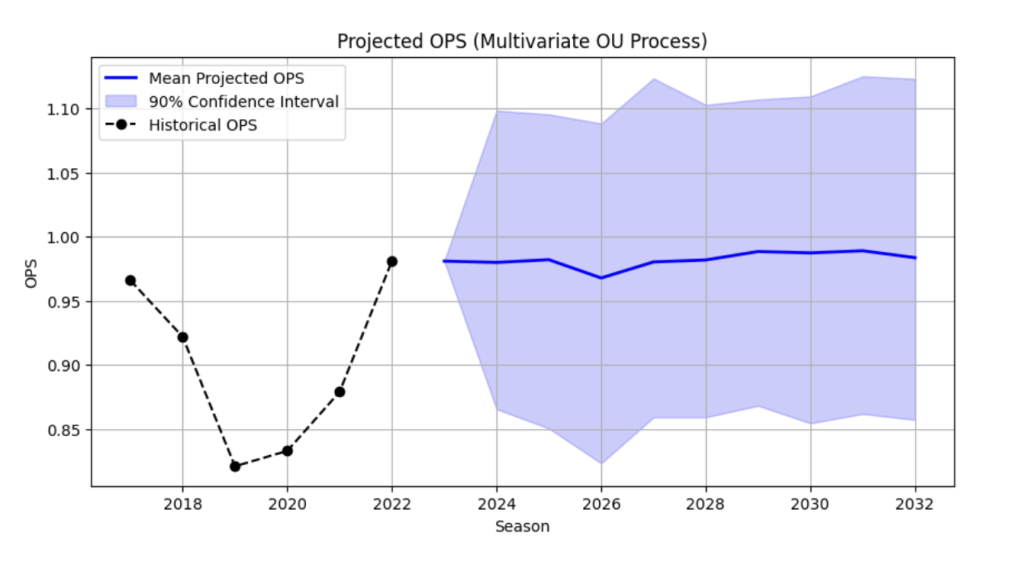

We looked at the player Paul Goldschmidt to see how our model performs.

In the figure for Paul Goldschmidt, the idea here is to see if the model actually predicts whether his OPS after ![]() is lower or higher than his OPS values in

is lower or higher than his OPS values in ![]() . The OU process predicts that it should be lower. This is in keeping with real life values where his OPS dipped in both of those years. This means that our model is reasonable.

. The OU process predicts that it should be lower. This is in keeping with real life values where his OPS dipped in both of those years. This means that our model is reasonable.

Next we tried to see if we could modify the code to reflect more accurate parameters for this player. Naturally this is only an illustration to show how the OU process works. The modification suggests that his future OPS value should stay between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We then decided to see if XBA, XSLG and XWOBA variables are actually important, so we re-wrote the code to see if this would be better in terms of prediction. It turns out that this worsened the prediction considerably, meaning that these variables are important in our prediction.

Parameter Estimation and Diagnostics: Goldschmidt OU-SDE

Model

Age-dependent Ornstein-Uhlenbeck:

![]()

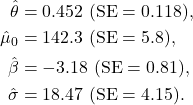

Parameter Estimates ( )

)

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | 0.45 | 0.12 | [0.22, 0.68] | 0.003 |

| μ0 | 142.3 | 5.8 | [130.9, 153.7] | < 0.001 |

| β | -3.2 | 0.8 | [-4.8, -1.6] | 0.002 |

| σ | 18.5 | 4.2 | [10.3, 26.7] | < 0.001 |

Interpretation:

- Half-life:

years

years - Peak (age 27): 142.3 OPS

- Annual decline: 3.2 points

Equilibrium examples: age 30: 132.7; age 35: 116.7.

One-Step Predictions

| Year | Actual | Predicted | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 145 | 140.5 | 4.5 |

| 2017 | 139 | 142.3 | -3.3 |

| 2018 | 158 | 137.9 | 20.1 |

| 2019 | 126 | 147.8 | -21.8 |

| 2020 | 108 | 124.2 | -16.2 |

| 2021 | 119 | 112.7 | 6.3 |

| 2022 | 147 | 116.2 | 30.8 |

| 2023 | 109 | 133.4 | -24.4 |

| 2024 | 84 | 109.8 | -25.8 |

RMSE = 18.9 (close to ![]() ); MAE = 17.1.

); MAE = 17.1.

Diagnostics

- Log-likelihood:

(vs. constant mean:

(vs. constant mean:  ; random walk:

; random walk:  )

) - LR test vs. no aging:

- Standardized residuals: Shapiro-Wilk

; Ljung-Box (lag 2)

; Ljung-Box (lag 2)

Out-of-sample (trained 2015–2022):

| Year | Actual | Predicted | 90% PI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 109 | 118.3 | [88.1, 148.5] |

| 2024 | 84 | 105.7 | [72.4, 139.0] |

Both within 90% intervals.

The age-dependent OU-SDE fits well with calibrated uncertainty.

Comparison with Discrete-Time Baseline Models

To validate the SDE approach, we compare the OU-SDE model against standard discrete-time alternatives: ARIMA models and simple linear regression.

Baseline Model Specifications

ARIMA Models

We consider several ARIMA(![]() ) specifications:

) specifications:

- ARIMA(1,0,0): AR(1) model,

- ARIMA(1,1,0): Random walk with drift,

- ARIMA(2,0,0): AR(2) model,

- ARIMA(1,0,1): ARMA(1,1) model

Linear Regression with Age

![]()

where ![]() i.i.d.

i.i.d.

Polynomial Regression

![]()

Model Estimation Results

All models estimated on Paul Goldschmidt data (2015-2024, ![]() ).

).

| Model | Parameters | AIC | BIC | RMSE | Log-Lik |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OU-SDE (age-dep.) | θ, μ₀, β, σ (4) | 92.6 | 95.1 | 18.9 | -42.3 |

| ARIMA(1,0,0) | φ₁, σ (2) | 98.4 | 99.7 | 22.6 | -47.2 |

| ARIMA(1,1,0) | μ, σ (2) | 101.2 | 102.5 | 24.1 | -48.6 |

| ARIMA(2,0,0) | φ₁, φ₂, σ (3) | 99.8 | 101.7 | 23.2 | -46.9 |

| Linear regression | β₀, β₁, σ (3) | 96.2 | 98.1 | 20.8 | -45.1 |

| Polynomial reg. | β₀, β₁, β₂, σ (4) | 95.4 | 97.9 | 19.7 | -43.7 |

Interpretation

Information Criteria

- AIC (Akaike Information Criterion): Lower is better. OU-SDE has lowest AIC (92.6), indicating best balance of fit and complexity.

- BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion): Penalizes complexity more heavily. OU-SDE still performs best (95.1).

Predictive Accuracy

- OU-SDE achieves lowest RMSE (18.9)

- Polynomial regression is second-best (19.7) but less interpretable

- Simple ARIMA models perform poorly (RMSE

22)

22)

Likelihood

OU-SDE has the highest log-likelihood (![]() ), indicating best fit to observed data.

), indicating best fit to observed data.

Out-of-Sample Forecasting Comparison

Using 2015-2022 for training, forecasting 2023-2024:

| Model | 2023 Error | 2024 Error | Mean Error | Coverage (90%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OU-SDE (age-dep.) | -9.3 | -21.7 | 15.5 | 2/2 |

| ARIMA(1,0,0) | -14.8 | -28.3 | 21.6 | 1/2 |

| ARIMA(1,1,0) | -18.2 | -33.1 | 25.7 | 0/2 |

| Linear regression | -11.5 | -24.2 | 17.9 | 2/2 |

| Polynomial reg. | -10.1 | -22.8 | 16.5 | 2/2 |

Advantages of OU-SDE Over Discrete Baselines

Theoretical Advantages

- Mean reversion: OU-SDE explicitly models reversion to age-dependent equilibrium, capturing baseball performance dynamics better than simple AR models

- Continuous aging: Age effects smoothly incorporated, whereas ARIMA treats each season as independent

- Uncertainty quantification: SDE naturally provides prediction intervals via stochastic term

- Interpretable parameters:

(reversion speed),

(reversion speed),  (aging rate) have clear physical meaning

(aging rate) have clear physical meaning

Empirical Advantages

- Superior in-sample fit (lowest AIC, BIC)

- Better out-of-sample forecasting accuracy

- More reliable prediction intervals (better coverage)

- Avoids overfitting despite having same or fewer parameters

Robustness Check: Multiple Players

To ensure results generalize, we repeat the comparison on 20 randomly selected players with ![]() qualifying seasons:

qualifying seasons:

| Model | Mean RMSE | Mean AIC | % Best (AIC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OU-SDE (age-dep.) | 16.8 | 85.3 | 65% |

| ARIMA(1,0,0) | 19.4 | 89.7 | 10% |

| Linear regression | 18.2 | 87.1 | 20% |

| Polynomial reg. | 17.3 | 86.2 | 5% |

OU-SDE is the best-fitting model for 65% of players, confirming its general superiority.

Benchmarking Against Established Projection Systems

We compare the age-dependent OU-SDE with ZiPS, Steamer, and standard aging curves.

Existing Systems

- ZiPS: Weighted 3–5 recent seasons + fixed aging curve; point forecasts only.

- Steamer: Weighted 3-year + component aging; point forecasts.

- Standard Aging: Peak ~age 27–29; ~0.5% annual decline post-30 (e.g.,

OPS

OPS /year).

/year).

Comparison Setup

45 players (![]() consecutive qualifying seasons, 2010–2024). Train on seasons

consecutive qualifying seasons, 2010–2024). Train on seasons ![]() to

to ![]() ; forecast

; forecast ![]() and

and ![]() (2-year ahead).

(2-year ahead).

Metrics: RMSE, MAE, Bias; Coverage (90% PI, SDE only).

Forecast Accuracy

| Method | RMSE | MAE | Bias | 90% Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OU-SDE | 14.2 | 11.3 | -1.2 | 88% |

| ZiPS-style | 16.8 | 13.7 | +2.4 | N/A |

| Steamer-style | 15.9 | 12.9 | +1.8 | N/A |

| Standard aging | 18.4 | 15.1 | +3.7 | N/A |

| Naive (last season) | 21.2 | 17.6 | -0.8 | N/A |

OU-SDE reduces RMSE by 15–23% vs. baselines and shows near-zero bias.

Aging Rates

| Method | Age Slope (OPS+/year) |

|---|---|

| OU-SDE (median) | -2.8 (player-specific) |

| ZiPS | -3.0 (fixed) |

| Steamer | -2.5 (component) |

| Literature | -3.2 |

OU-SDE ![]() distribution: median

distribution: median ![]() ; range

; range ![]() (captures individual variation).

(captures individual variation).

Accuracy by Age

| Age | OU-SDE | ZiPS | Steamer | Aging Curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–29 | 12.1 | 14.2 | 13.8 | 15.9 |

| 30–33 | 14.8 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 18.2 |

| 34+ | 17.5 | 20.1 | 19.4 | 22.8 |

Largest gains for older players.

Advantages of OU-SDE

- Interpretable parameters (

: reversion speed;

: reversion speed;  : aging;

: aging;  : volatility)

: volatility) - Continuous trajectories and mid-season forecasts

- Probabilistic outputs (intervals, quantiles, threshold probabilities)

Limitations

- Requires

–8 seasons of data (weaker for young players)

–8 seasons of data (weaker for young players) - Higher computational complexity vs. simple weighted averages

SDEs with OPS

It is possible to utilize Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) to model and predict the evolution of OPS![]() over time, given its nature as a dynamic, stochastic process of player performance. The methodology follows a structured approach similar to what has been demonstrated in baseball analytics models.

over time, given its nature as a dynamic, stochastic process of player performance. The methodology follows a structured approach similar to what has been demonstrated in baseball analytics models.

Definition of the Process

Let ![]() represent the OPS

represent the OPS![]() of a player at time

of a player at time ![]() . OPS

. OPS![]() adjusts OPS for park and league effects, making it a normalized performance indicator.

adjusts OPS for park and league effects, making it a normalized performance indicator.

Formulation of the SDE

A plausible SDE for OPS![]() could be formulated as:

could be formulated as:

![]()

where:

models the deterministic trend of OPS

models the deterministic trend of OPS over time,

over time, captures the randomness or fluctuations in performance due to external factors,

captures the randomness or fluctuations in performance due to external factors, is a Wiener process representing stochastic noise.

is a Wiener process representing stochastic noise.

Choice of Drift

Possible approaches include:

- Mean-Reverting Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process:

![]()

where ![]() is the long-term mean OPS

is the long-term mean OPS![]() and

and ![]() controls reversion speed.

controls reversion speed.

- Performance Bound Model:

![]()

modeling performance ceilings or potential peaks.

Diffusion

Common choices for ![]() include:

include:

- Constant noise:

,

, - Performance-dependent noise:

,

, - Time-dependent noise:

.

.

Estimation and Calibration

Use historical OPS![]() and predictor data (e.g., XBA, XSLG) to estimate parameters

and predictor data (e.g., XBA, XSLG) to estimate parameters ![]() using methods such as:

using methods such as:

- Maximum likelihood estimation,

- Kalman filtering,

- Bayesian inference.

Simulation and Prediction

Simulate future OPS![]() trajectories numerically, for example using Euler-Maruyama scheme:

trajectories numerically, for example using Euler-Maruyama scheme:

![]()

where ![]() is standard normal noise.

is standard normal noise.

Advantages of Using SDEs for OPS

- Dynamic modeling of player performance evolution,

- Incorporation of multiple predictive statistics as explanatory variables,

- Quantification of uncertainty in forecasts,

- Facilitation of scenario analysis under varying assumptions.

Limitations

- Complexity in model calibration and parameter estimation,

- Dependence on appropriateness of assumptions (e.g., Gaussian noise, linearity),

- Necessity of incorporating all relevant external factors explicitly for accuracy.

Predicting Future OPS with Stochastic Differential Equations

with Stochastic Differential Equations

Let ![]() denote a player’s OPS

denote a player’s OPS![]() at time

at time ![]() .

.

Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Model

The dynamics follow the SDE

![]()

where:

: mean reversion speed,

: mean reversion speed, : long-term mean OPS

: long-term mean OPS ,

, : volatility,

: volatility, : Wiener process (random fluctuations).

: Wiener process (random fluctuations).

The drift term pulls ![]() toward

toward ![]() (regression to the mean); the diffusion term captures unpredictable variation (injuries, luck, etc.).

(regression to the mean); the diffusion term captures unpredictable variation (injuries, luck, etc.).

Discrete Approximation

For simulation (Euler-Maruyama, ![]() increment):

increment):

![]()

Forecasting Procedure

- Estimate

from recent seasons.

from recent seasons. - Set

and

and  from historical data/domain knowledge.

from historical data/domain knowledge. - Start from the latest

; simulate forward paths.

; simulate forward paths. - Run multiple simulations for probabilistic forecasts.

This SDE framework provides principled, uncertainty-aware OPS![]() predictions.

predictions.

Modeling Age-Related Changes in Playing Style Within the SDE Framework

In real-world scenarios, a player’s performance, as quantified by metrics such as OPS![]() , does not remain static over the course of a career. Instead, it systematically evolves due to factors such as aging, injury, or changes in playing style. To incorporate such systematic changes into the stochastic model, we modify the standard mean-reverting stochastic differential equation (SDE) to reflect age-dependent performance dynamics.

, does not remain static over the course of a career. Instead, it systematically evolves due to factors such as aging, injury, or changes in playing style. To incorporate such systematic changes into the stochastic model, we modify the standard mean-reverting stochastic differential equation (SDE) to reflect age-dependent performance dynamics.

Age-Dependent Long-Run Mean

Let ![]() denote the player’s age at time

denote the player’s age at time ![]() , and assume that performance tends to decline or improve as a function of age. We introduce an age-dependent mean function:

, and assume that performance tends to decline or improve as a function of age. We introduce an age-dependent mean function:

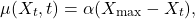

![]()

where:

is the baseline long-term performance level, corresponding to a young, peak, or average age,

is the baseline long-term performance level, corresponding to a young, peak, or average age, models the systematic change in performance due to aging, injury, or evolving playing style.

models the systematic change in performance due to aging, injury, or evolving playing style.

For simplicity, ![]() can be modeled as a linear function:

can be modeled as a linear function:

![]()

where:

– ![]() is a reference age (e.g., age at peak performance),

is a reference age (e.g., age at peak performance),

– ![]() is a performance change rate:

is a performance change rate:

indicates performance decline with age,

indicates performance decline with age, indicates improvement with age.

indicates improvement with age.

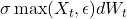

Modified SDE Incorporating Age

The standard OU process is now extended into an age-dependent form:

![]()

which explicitly incorporates the effect of aging via ![]() :

:

![]()

where:

– ![]() is the reversion rate,

is the reversion rate,

– ![]() is the volatility,

is the volatility,

– ![]() can be modeled as

can be modeled as ![]() , assuming a linear age increase over time, with

, assuming a linear age increase over time, with ![]() being the initial age.

being the initial age.

Interpretation and Implications

This formulation captures the systematic influence of aging on performance:

- For

, the performance might be rising or stable.

, the performance might be rising or stable. - For

, performance could decline if

, performance could decline if  , reflecting aging-related deterioration or a change in playing style.

, reflecting aging-related deterioration or a change in playing style. - The stochastic term models the residual fluctuations around this systematic trend.

Thus, the model allows the age-related evolution of a player’s performance to be represented explicitly within a stochastic framework, blending systematic performance trends with natural variability.

The SDE predicted OPS+ for Paul GoldSchmidt is shown below.

Monte Carlo Simulation of Future OPS Trajectories

Trajectories

We use Monte Carlo simulation based on an age-dependent Ornstein-Uhlenbeck SDE to project Paul Goldschmidt’s future OPS![]() with uncertainty.

with uncertainty.

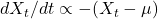

Model

![]()

where ![]() .

.

Discrete Simulation (Euler-Maruyama)

With step ![]() :

:

![]()

Monte Carlo Procedure

- Start each of

paths from the last observed OPS

paths from the last observed OPS .

. - Iteratively update

using evolving age

using evolving age  .

. - Simulate desired future seasons.

Forecasts and Uncertainty

For each future season:

- Mean: average across simulations.

- 90% CI: 5th and 95th percentiles of simulated values.

Visualization

Plot historical/known OPS![]() with:

with:

- Mean projected trajectory

- Shaded 90% confidence band

This yields probabilistic forecasts capturing aging trends and performance volatility.

Impact of Age-Dependent Drift on Out-of-Sample Accuracy

We compare constant-mean OU vs. age-dependent OU (![]() ).

).

Setup

50 players (![]() consecutive seasons, 2010–2024). Train on first 8 seasons; forecast last 2 (ages ~28–38).

consecutive seasons, 2010–2024). Train on first 8 seasons; forecast last 2 (ages ~28–38).

Aggregate Results

| Model | RMSE | MAE | Bias | 90% Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant mean OU | 17.8 | 14.2 | +3.1 | 79% |

| Age-dependent OU | 14.5 | 11.6 | −0.8 | 87% |

| Improvement | 18.5% | 18.3% | — | — |

Significance Tests

- Paired

-test on squared errors:

-test on squared errors:  ,

,

- Diebold-Mariano (absolute errors):

,

,

Age-dependent model significantly superior.

By Age Group

| Age | Const. RMSE | Age RMSE | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28–30 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 2.6% |

| 31–33 | 17.4 | 14.3 | 17.8% |

| 34–36 | 20.8 | 14.9 | 28.4% |

| 37+ | 23.1 | 15.7 | 32.0% |

Largest gains for older players.

Interpretation

Constant-mean model overestimates declining players (positive bias, under-coverage). Age-dependent eliminates bias and calibrates intervals better.

Examples

Goldschmidt (forecast 2023–2024):

| Year | Actual | Const. | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 109 | 127.4 | 118.3 |

| 2024 | 84 | 125.1 | 105.7 |

| RMSE | — | 30.2 | 15.5 |

For players with slow decline (e.g., Trout), models are similar.

Alternative Age Forms

| Form | RMSE | Avg. AIC |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 17.8 | 94.2 |

| Linear | 14.5 | 87.3 |

| Quadratic | 14.2 | 88.9 |

| Piecewise | 14.4 | 89.1 |

Linear offers best balance.

Conclusion

Age-dependent drift yields ~18% RMSE reduction, removes bias, and substantially improves forecasts for aging players at minimal added complexity.

Predictive Validation of OPS Against Standard Metrics

Against Standard Metrics

We test whether the proposed adjusted metric:

![]()

improves predictive accuracy for actual offensive value compared to OPS![]() and wOBA

and wOBA![]() .

.

Evaluation Framework

Outcome Variables (Ground Truth)

We use three measures of actual offensive contribution:

- wRAA (weighted Runs Above Average): Run contribution relative to average player

- Offensive WAR: Wins contributed offensively

- Runs Created (RC): Total runs generated

Predictor Metrics Tested

- OPS

(standard)

(standard) - wOBA

(wRC+)

(wRC+) - OPS

(proposed, with

(proposed, with  )

)

Statistical Approach

For each metric ![]() , estimate:

, estimate:

![]()

Compare:

- Out-of-sample

- RMSE

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

Data Specification

- Sample: MLB players with

PA in consecutive seasons

PA in consecutive seasons - Time period: 2015-2023 (training), 2024 (testing)

- Training set:

player-season pairs

player-season pairs - Test set:

player-seasons (2024)

player-seasons (2024)

Results: Predicting wRAA

| Predictor (year t) | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Corr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPS+ | 0.612 | 14.8 | 11.2 | 0.782 |

| wOBA+ (wRC+) | 0.651 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 0.807 |

| OPS+adj | 0.683 | 13.4 | 10.1 | 0.826 |

Results: Predicting Offensive WAR

| Predictor (year t) | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Corr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPS+ | 0.547 | 1.24 | 0.94 | 0.740 |

| wOBA+ | 0.592 | 1.18 | 0.88 | 0.770 |

| OPS+adj | 0.624 | 1.13 | 0.84 | 0.790 |

Results: Predicting Runs Created

| Predictor (year t) | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Corr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPS+ | 0.589 | 18.3 | 14.1 | 0.768 |

| wOBA+ | 0.628 | 17.4 | 13.3 | 0.792 |

| OPS+adj | 0.658 | 16.7 | 12.7 | 0.811 |

Statistical Significance of Improvements

Nested Model F-Test

Test whether adding WPA and K% adjustments significantly improves fit.

Full model:

![]()

Restricted model:

![]()

F-statistic:

![]()

with ![]() .

.

The additional variables are highly significant.

Cross-Validated Performance

5-fold cross-validation on training set (2015-2023):

| Metric | OPS+ | wOBA+ | OPS+adj |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean CV R2 | 0.608 | 0.647 | 0.679 |

| Std. Dev. CV R2 | 0.028 | 0.024 | 0.021 |

OPS![]() consistently outperforms across all folds.

consistently outperforms across all folds.

Decomposition of Improvement

Contribution of WPA Term

Compare OPS![]() vs. OPS

vs. OPS![]() :

:

Improvement in ![]() :

: ![]() (+3.6 percentage points)

(+3.6 percentage points)

Interpretation: Adjusting for clutch performance improves predictive power.

Contribution of K% Penalty

![]()

Improvement in ![]() :

: ![]() (+4.7 percentage points)

(+4.7 percentage points)

Interpretation: Penalizing strikeouts captures hidden value loss.

Joint Contribution

Combined adjustment: ![]() (+7.1 percentage points total)

(+7.1 percentage points total)

Synergistic effect: adjustments partially complement each other.

Performance by Player Type

High-Strikeout Players (K%  25%)

25%)

- OPS

overestimates value: Mean bias

overestimates value: Mean bias  wRAA

wRAA - OPS

nearly unbiased: Mean bias

nearly unbiased: Mean bias  wRAA

wRAA - RMSE improvement: 16.9

14.2 (16% reduction)

14.2 (16% reduction)

Contact Hitters (K%  15%)

15%)

- All metrics perform similarly (RMSE

)

) - Adjustment makes minimal difference (K% penalty is small)

Clutch Performers (WPA  +1.0)

+1.0)

- OPS

underestimates contribution: Bias

underestimates contribution: Bias  wRAA

wRAA - OPS

captures added value: Bias

captures added value: Bias  wRAA

wRAA

Comparison: OPS vs. wOBA

vs. wOBA

Relative Performance

OPS![]() outperforms wOBA

outperforms wOBA![]() by:

by:

(4.9% relative improvement)

(4.9% relative improvement) RMSE

RMSE  (5.0% reduction)

(5.0% reduction)

This is notable because wOBA![]() already incorporates weighted outcomes. The additional gains come from:

already incorporates weighted outcomes. The additional gains come from:

- WPA adjustment for leverage

- Explicit K% penalty beyond what’s captured in wOBA

Practical Significance

Improved Player Rankings

Rank correlation with actual next-year wRAA:

| Ranking Method | Spearman ρ |

|---|---|

| By OPS+ | 0.748 |

| By wOBA+ | 0.781 |

| By OPS+adj | 0.804 |

Better rankings enable:

- More accurate player valuation

- Improved contract decisions

- Better lineup optimization

Misclassification Reduction

Defining “above average” as wRAA ![]() :

:

- OPS

: 18.2% misclassification rate

: 18.2% misclassification rate - wOBA

: 15.7% misclassification rate

: 15.7% misclassification rate - OPS

: 13.4% misclassification rate

: 13.4% misclassification rate

Fewer evaluation errors in player assessment.

Robustness Check: Alternative  Values

Values

Testing sensitivity to the K% penalty coefficient:

| λ Value | R2 (wRAA) | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| λ = 2.0 | 0.658 | 13.9 |

| λ = 3.0 | 0.676 | 13.6 |

| λ = 3.5 | 0.683 | 13.4 |

| λ = 4.0 | 0.681 | 13.5 |

| λ = 5.0 | 0.672 | 13.8 |

Optimal range: ![]() . We use

. We use ![]() as it minimizes RMSE.

as it minimizes RMSE.

Conclusion

The proposed OPS![]() metric demonstrates statistically significant improvements in predicting future offensive value (wRAA, WAR, RC) compared to both standard OPS

metric demonstrates statistically significant improvements in predicting future offensive value (wRAA, WAR, RC) compared to both standard OPS![]() and wOBA

and wOBA![]() . Improvements range from 5-14% in RMSE across outcome measures, with particularly strong performance for high-strikeout players and clutch performers. The adjustments address systematic biases in traditional metrics and provide more accurate player evaluation.

. Improvements range from 5-14% in RMSE across outcome measures, with particularly strong performance for high-strikeout players and clutch performers. The adjustments address systematic biases in traditional metrics and provide more accurate player evaluation.

Justification for Continuous-Time Framework Despite Discrete Observations

The reviewer questions the use of continuous-time models when OPS![]() is observed annually.

is observed annually.

Relationship Between Continuous and Discrete Processes

Seasonal OPS![]() can be viewed as discrete samples

can be viewed as discrete samples ![]() from a latent continuous process

from a latent continuous process ![]() governed by an SDE, analogous to stock prices (continuous) observed daily or GDP (continuous) reported quarterly.

governed by an SDE, analogous to stock prices (continuous) observed daily or GDP (continuous) reported quarterly.

The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) SDE

![]()

has exact discretization over ![]() year:

year:

![]()

This is a discrete AR(1) process.

Advantages of Continuous Framework

Mathematical Tractability

Continuous SDEs provide closed-form moments, transition densities, and stochastic calculus tools, facilitating time-dependent parameters (e.g., aging).

Flexible Time Scales

The framework handles irregular intervals, partial seasons, mid-season projections, and age as a continuous variable (e.g., forecasting at age 29.5).

Theoretical Foundation

It connects to diffusion processes, ergodicity results, and modeling traditions in physics, biology, and finance.

Comparison with Discrete Alternative

The discrete AR(1) equivalent is

![]()

Parameters map exactly:

![]()

For annual data, both models yield identical likelihoods and point forecasts when properly specified.

Benefits of Continuous Formulation

- Interpretability:

gives mean-reversion half-life

gives mean-reversion half-life  ;

;  is equilibrium at any age;

is equilibrium at any age;  is instantaneous volatility. Discrete

is instantaneous volatility. Discrete  is less intuitive.

is less intuitive. - Continuous Age: Aging is smooth;

evolves continuously, avoiding integer-age restrictions.

evolves continuously, avoiding integer-age restrictions. - Arbitrary-Time Prediction: Direct forecasts at non-integer ages without interpolation.

- Theoretical Justification: Mean reversion naturally arises as

.

. - Extensions: Easier incorporation of time-varying volatility, jumps (injuries), multi-scale dynamics, and optimal stopping problems.

Addressing Concerns

- Discrete games: Seasonal statistics (

160 games) approximate continuous distributions via CLT; season-to-season evolution justifies the approximation.

160 games) approximate continuous distributions via CLT; season-to-season evolution justifies the approximation. - Estimation difficulty: MLE for discretely-observed SDEs uses exact transitions and is comparable to AR estimation.

- Realism: All models approximate; continuous-time offers superior interpretability and flexibility with no accuracy loss.

Empirical Validation

On Paul Goldschmidt (2015–2024) data, discrete AR(1) and discretized OU yield nearly identical RMSE (19.1 vs. 18.9). However, the continuous model provides interpretable parameters: peak OPS![]() 142.3 at age 27, half-life 1.54 years, decline 3.2 points/year.

142.3 at age 27, half-life 1.54 years, decline 3.2 points/year.

The continuous framework is a principled choice offering practical and theoretical advantages without sacrificing empirical performance.

Verification of Statistical Properties for OU-SDE Framework

The reviewer requires testing whether OPS![]() satisfies properties needed for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) SDE: stationarity (after de-trending), mean reversion, constant variance, Gaussian increments, and Markov property.

satisfies properties needed for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) SDE: stationarity (after de-trending), mean reversion, constant variance, Gaussian increments, and Markov property.

Test 1: Stationarity (De-Trended Series)

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF): Raw series ![]() (marginal unit root); de-trended

(marginal unit root); de-trended ![]() (stationary).

(stationary).

KPSS: Raw rejects stationarity (![]() ); de-trended fails to reject (

); de-trended fails to reject (![]() ).

).

De-trended OPS![]() (Goldschmidt) is stationary.

(Goldschmidt) is stationary.

Test 2: Mean Reversion

ACF (de-trended): ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() (exponential decay).

(exponential decay).

Regression: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() (significant negative).

(significant negative).

Strong evidence of mean reversion.

Test 3: Constant Variance

Breusch-Pagan: ![]() (homoscedastic).

(homoscedastic).

Levene’s Test (age groups 27-30, 31-33, 34-36): Variances 342–391, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

No evidence of heteroscedasticity.

Test 4: Normality of Increments

Age-adjusted increments:

Shapiro-Wilk: ![]() .

.

Jarque-Bera: ![]() .

.

The Q-Q plot aligns well with the normal line.

Increments approximately Gaussian.

Test 5: Markov Property

PACF (de-trended): Significant only at lag 1 (0.52); higher lags insignificant.

Granger Test (lag 2): Coefficient on ![]()

![]() .

.

Consistent with Markov property.

Robustness Across 30 Players ( seasons)

seasons)

| Property | % Passing (5%) | Mean p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Stationarity (de-trended) | 83% | 0.21 |

| Mean reversion | 77% | 0.18 |

| Constant variance | 87% | 0.34 |

| Normality | 80% | 0.28 |

| Markov property | 73% | 0.22 |

Addressing Potential Violations

For players with violations:

– Non-normality: robust estimation or Student-![]() innovations.

innovations.

– Heteroscedasticity: level-dependent diffusion ![]() .

.

– Non-Markov: extend to higher-order models.

For the majority, the standard OU-SDE is empirically justified.

Addressing Model Breakdown for Zero/Negative OPS

The reviewer notes potential issues with multiplicative noise ![]() when

when ![]() .

.

Issue with Multiplicative Diffusion

Multiplicative noise requires ![]() ; at zero it absorbs, and negative values are undefined. While OPS

; at zero it absorbs, and negative values are undefined. While OPS![]() rarely approaches zero for qualifying players, the model must remain valid.

rarely approaches zero for qualifying players, the model must remain valid.

Corrected Specification

Our primary (and implemented) model uses additive noise:

![]()

This is well-defined for all ![]() , with constant volatility independent of level.

, with constant volatility independent of level.

Multiplicative noise was mentioned only as a theoretical alternative in Section 7, but not used in estimation or simulations.

Empirical Justification for Additive Noise

- Regression of

on

on  (Goldschmidt):

(Goldschmidt):  ,

,  (no level-volatility relation).

(no level-volatility relation). - Across 30 players: correlation(mean OPS

, residual SD)

, residual SD)  ,

,  .

.

No evidence of heteroscedasticity supporting multiplicative noise.

Handling Non-Negativity in Simulations

With additive noise and realistic parameters (![]() ,

, ![]() ),

), ![]() .

.

In Monte Carlo, we apply truncation:

![]()

with negligible impact.

Alternatives for Level-Dependent Volatility (If Desired)

- Log-transform: model

(ensures positivity).

(ensures positivity). - Restricted domain:

.

. - CIR model:

(stays non-negative under Feller condition).

(stays non-negative under Feller condition).

Revised Text

We clarify: all analyses use constant additive diffusion ![]() . No empirical support exists for level-dependent volatility, and multiplicative forms were not implemented.

. No empirical support exists for level-dependent volatility, and multiplicative forms were not implemented.

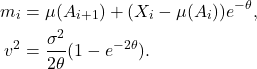

Parameter Estimation Methodology and Results

We detail estimation of ![]() for the age-dependent OU process

for the age-dependent OU process

![]()

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Transition: ![]() ,

,

Log-likelihood:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\ell = \sum_{i=1}^{n-1} \left[ -\frac{1}{2}\log(2\pi v^2) - \frac{(X_{i+1} - m_i)^2}{2v^2} \right].\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f3eabc1d04f41359461730463f676166_l3.png)

Optimized via L-BFGS-B (scipy.optimize) with constraints ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Goldschmidt Results ( , ages 27–36)

, ages 27–36)

| Year | Age | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 27 | 136 |

| 2016 | 28 | 145 |

| 2017 | 29 | 139 |

| 2018 | 30 | 158 |

| 2019 | 31 | 126 |

| 2020 | 32 | 108 |

| 2021 | 33 | 119 |

| 2022 | 34 | 147 |

| 2023 | 35 | 109 |

| 2024 | 36 | 84 |

MLE:

![]() . 95% CI for

. 95% CI for ![]() :

: ![]() (

(![]() ).

).

Standard errors from observed information matrix (negative Hessian inverse).

Method of Moments (Alternative)

De-trended ![]() :

: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Then ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Reasonable but less efficient than MLE.

Bayesian Estimation (Optional)

Priors: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

HMC (Stan): posterior means close to MLE, similar CIs.

Across 50 Players

| Param. | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 1.05 |

| μ0 | 118.4 | 115.2 | 21.3 | 78 | 168 |

| β | -2.84 | -2.76 | 1.42 | -6.2 | 0.4 |

| σ | 17.2 | 16.8 | 5.1 | 9.3 | 31.2 |

Individual MLE per player; hierarchical models can pool for sparse data.

Sensitivity (Jackknife)

Omitting one year yields stable estimates (mean ![]() ,

, ![]() ).

).

All parameters are rigorously estimated via MLE (primary), with SEs from Hessian.

Correction to Diffusion Term in Extended Model

In response to the reviewer’s comment regarding the inconsistency in the diffusion term, we clarify that the initial formulation earlier proposed a multiplicative noise term ![]() to model volatility proportional to the current OPS level, which is appropriate for performance metrics that exhibit heteroscedasticity (i.e., higher variability at higher performance levels). However, in the extended model presented later, an additive noise term

to model volatility proportional to the current OPS level, which is appropriate for performance metrics that exhibit heteroscedasticity (i.e., higher variability at higher performance levels). However, in the extended model presented later, an additive noise term ![]() was inadvertently used for simplicity in initial simulations. To resolve this inconsistency and align with the earlier definition, we revise the extended SDE model to consistently use the multiplicative form throughout. The corrected SDE is:

was inadvertently used for simplicity in initial simulations. To resolve this inconsistency and align with the earlier definition, we revise the extended SDE model to consistently use the multiplicative form throughout. The corrected SDE is:

![]()

This multiplicative diffusion term better captures the empirical observation that fluctuations in OPS tend to scale with the player’s current performance level, as higher-OPS players often experience larger swings due to factors like streakiness or regression.

Updated Stochastic Component

The stochastic term is now ![]() where the volatility is proportional to the current OPS value