Abstract

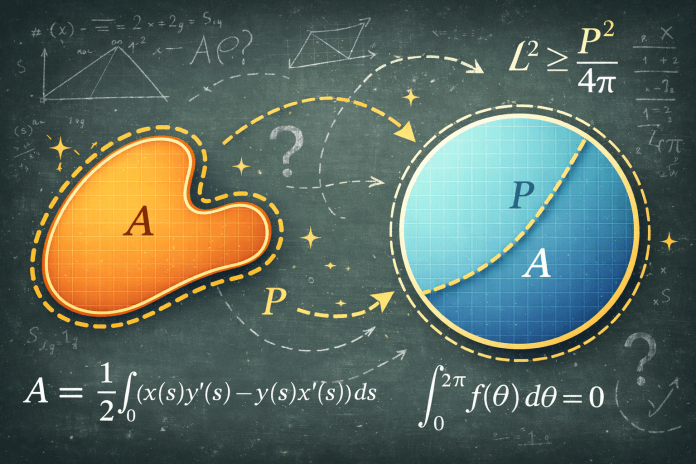

In this paper, we will prove the Isoperimetric inequality, which states that for any simple closed curve with perimeter ![]() and area

and area ![]() , the inequality

, the inequality ![]() must hold, with equality only when the curve is a circle. Our proof follows Adolf Hurwitz’s analytic route. We will use Fourier series and Parseval’s theorem to obtain Wirtinger’s inequality, which will be applied to a curve written in arc-length form. This path is interesting because it reaches a classic geometry result using mostly algebra and basic calculus instead of geometry. This paper gives a clear, complete walk-through of Hurwitz’s proof, written so students can follow every step without gaps.

must hold, with equality only when the curve is a circle. Our proof follows Adolf Hurwitz’s analytic route. We will use Fourier series and Parseval’s theorem to obtain Wirtinger’s inequality, which will be applied to a curve written in arc-length form. This path is interesting because it reaches a classic geometry result using mostly algebra and basic calculus instead of geometry. This paper gives a clear, complete walk-through of Hurwitz’s proof, written so students can follow every step without gaps.

Introduction

The Isoperimetric problem studies which shape encloses the greatest area for a fixed perimeter. An early illustration of the problem is the story of Queen Dido and the founding of Carthage. According to the legend, Dido was allowed as much land as she could surround with one oxhide, which she cut into thin strips and arranged along the coast to enclose as large a region as possible. This story captures the central idea that the circle is the most efficient shape for enclosing area with a given boundary length.1

The formal result is the Isoperimetric inequality, which states that for any simple closed curve with perimeter ![]() and enclosed area

and enclosed area ![]() , the relationship

, the relationship

![]()

holds, with equality only for a circle. Although the statement is simple and straightforward, the proof is not immediate. In this paper I will explain Adolf Hurwitz’s analytic proof2‘3, chosen for its algebraic precision and clear structure. The argument uses Fourier series and Parseval’s theorem to derive Wirtinger’s inequality and then applies it to a curve written in arc-length form to establish the result.

Hurwitz’s proof applies to smooth, closed curves that can be represented by piecewise ![]() (differentiable and has a continuous derivative),

(differentiable and has a continuous derivative), ![]() -periodic functions whose derivatives are square-integrable. These assumptions are made to ensure that the tools and theorems we use later are valid. The Isoperimetric inequality itself, however, holds much more generally, even for curves that are not smooth, as proven in later geometrical proofs.

-periodic functions whose derivatives are square-integrable. These assumptions are made to ensure that the tools and theorems we use later are valid. The Isoperimetric inequality itself, however, holds much more generally, even for curves that are not smooth, as proven in later geometrical proofs.

The purpose of this paper is to present a complete, step-by-step explanation of Hurwitz’s proof in a form that is understandable for advanced high-school students. The focus is the two-dimensional case and only the analytic method is developed. Other proofs and higher-dimensional versions are mentioned briefly for context but are not explored in detail. The paper begins with a short review of Fourier series, Parseval’s theorem, and Wirtinger’s inequality, followed by a simpler triangle case of the Isoperimetric inequality proved with the AM–GM inequality. It then presents the full Hurwitz proof and concludes with brief notes on generalizations and applications.

Methodology

Hurwitz’s proof of the Isoperimetric inequality utilizes ![]() important concepts: Fourier series, Parseval’s theorem, and Wirtinger’s inequality. The first two are applied to obtain Wirtinger’s inequality, which is used as a crucial step in the final proof.

important concepts: Fourier series, Parseval’s theorem, and Wirtinger’s inequality. The first two are applied to obtain Wirtinger’s inequality, which is used as a crucial step in the final proof.

Fourier Series

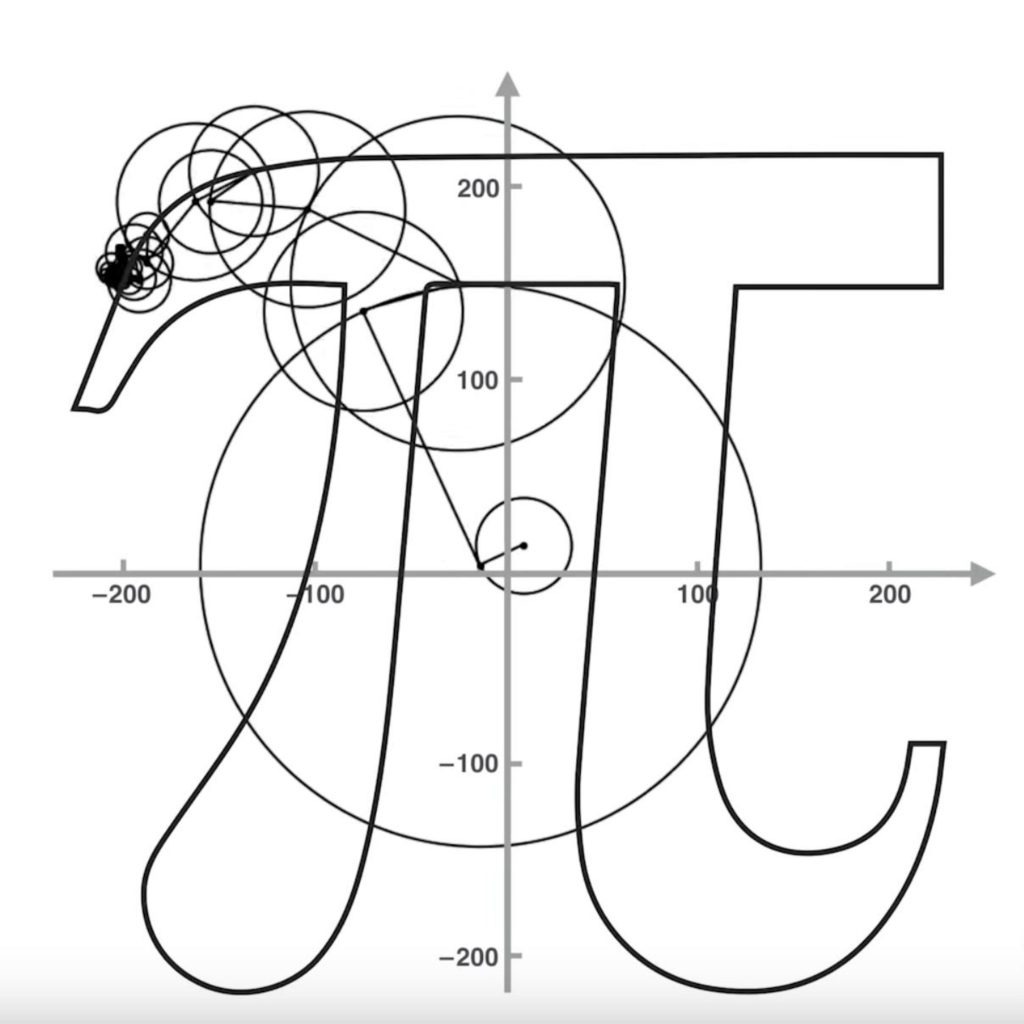

The Fourier series is a powerful tool to help approximate any function using only sine and cosine functions. The main idea is that it adds up a collection of waves made from a combination of sines and cosines to estimate the function. As the number of terms in the sum increases, the approximation gets finer and finer. When there are an infinite number of terms in the sequence, the sum is exactly equal to the function.4

The figure above shows how the sum of ![]() waves made of both sine and cosine functions can sum up to be the new wave. Remember that another way of representing sine and cosine waves are circles on complex planes with vectors rotating inside. Using the circles to lay out the Fourier Series we can see that it becomes a sequence of vectors connected tip to tail, each with a different radius and rotating at different frequencies. This chain of arrows can trace out anything in the

waves made of both sine and cosine functions can sum up to be the new wave. Remember that another way of representing sine and cosine waves are circles on complex planes with vectors rotating inside. Using the circles to lay out the Fourier Series we can see that it becomes a sequence of vectors connected tip to tail, each with a different radius and rotating at different frequencies. This chain of arrows can trace out anything in the ![]() dimensional complex plane with enough vectors.

dimensional complex plane with enough vectors.

While the Fourier series has many deeper properties, for the purpose of this paper we only need the general form of the series for most functions. For clarity, we assume throughout that ![]() is real-valued,

is real-valued, ![]() -periodic, piecewise

-periodic, piecewise ![]() on

on ![]() , with

, with ![]() . Under these hypotheses we can use mean-square convergence for Fourier series.

. Under these hypotheses we can use mean-square convergence for Fourier series.

![]()

Parseval’s Theorem

Parseval’s theorem5‘6 states that if a function has a Fourier series

![]()

then

![]()

Parseval’s theorem holds for every ![]() . In this paper Parseval is used in the mean-square sense, consistent with the mean-square convergence stated above.

. In this paper Parseval is used in the mean-square sense, consistent with the mean-square convergence stated above.

Now we will prove the theorem. Squaring the Fourier series of ![]() , we get

, we get

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Taking the integral on both sides we get

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We will calculate each term separately. For the first term, we get

![]()

For the second term, we notice that because sine and cosine are ![]() periodic functions

periodic functions

![]()

For the third term, we will use Orthogonality relations7. By Orthogonality relations, we can see that the following ![]() equations hold.

equations hold.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}\cos{(nx)}\cos{(mx)}dx = \begin{cases} \text{$0$} & \text{if $n \neq m$} \\ \text{$\pi$} & \text{if $n = m \neq 0$} \\ \text{$2\pi$} & \text{if $n = m = 0$} \end{cases}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-637382a1078997191713e16523133d70_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}\sin{(nx)}\sin{(mx)}dx = \begin{cases} \text{$0$} & \text{if $n \neq m$} \\ \text{$\pi$} & \text{if $n = m \neq 0$} \\ \text{$0$} & \text{if $n = m = 0$} \end{cases}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7b651cee91018f74af3d21a6f5542422_l3.png)

![]()

Plugging it into the third term, we get

![]()

![]()

Notice that when we plug the Orthogonality relations in, we don’t have to worry about cases where ![]() since

since ![]() and

and ![]() . Summing the

. Summing the ![]() terms together, we get

terms together, we get

![]()

So,

![]()

Note that Parseval’s theorem is the equality case of Bessel’s inequality8.

Wirtinger’s Inequality

Wirtinger’s inequality9 says that let ![]() be a periodic function of period

be a periodic function of period ![]() . The function is continuous and also has a continuous derivative throughout

. The function is continuous and also has a continuous derivative throughout ![]() . If

. If

![]()

then

![]()

The equality case only holds when ![]() for some

for some ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

To prove it, we first see that because ![]() is continuous, its derivative is continuous, and its period is

is continuous, its derivative is continuous, and its period is ![]() , Dirichlet’s conditions10 are met and we can write the Fourier series for

, Dirichlet’s conditions10 are met and we can write the Fourier series for ![]() to be

to be

![]()

Note that ![]() because

because

![]()

Therefore, Parseval’s theorem now becomes

(1) ![]()

Note that we changed the parameters of the integral from ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() and

and ![]() . This doesn’t change anything because

. This doesn’t change anything because ![]() is a

is a ![]() periodic function. We can first take the derivative of

periodic function. We can first take the derivative of ![]() to get

to get

![]()

Plugging this into Parseval’s theorem gives us

(2) ![]()

Note that the minus sign in the equation for ![]() is canceled out due to squaring on the right-hand side of Parseval’s theorem. Because

is canceled out due to squaring on the right-hand side of Parseval’s theorem. Because ![]() , (2)

, (2) ![]() (1), the Wirtinger’s inequality must be true.

(1), the Wirtinger’s inequality must be true.

Results

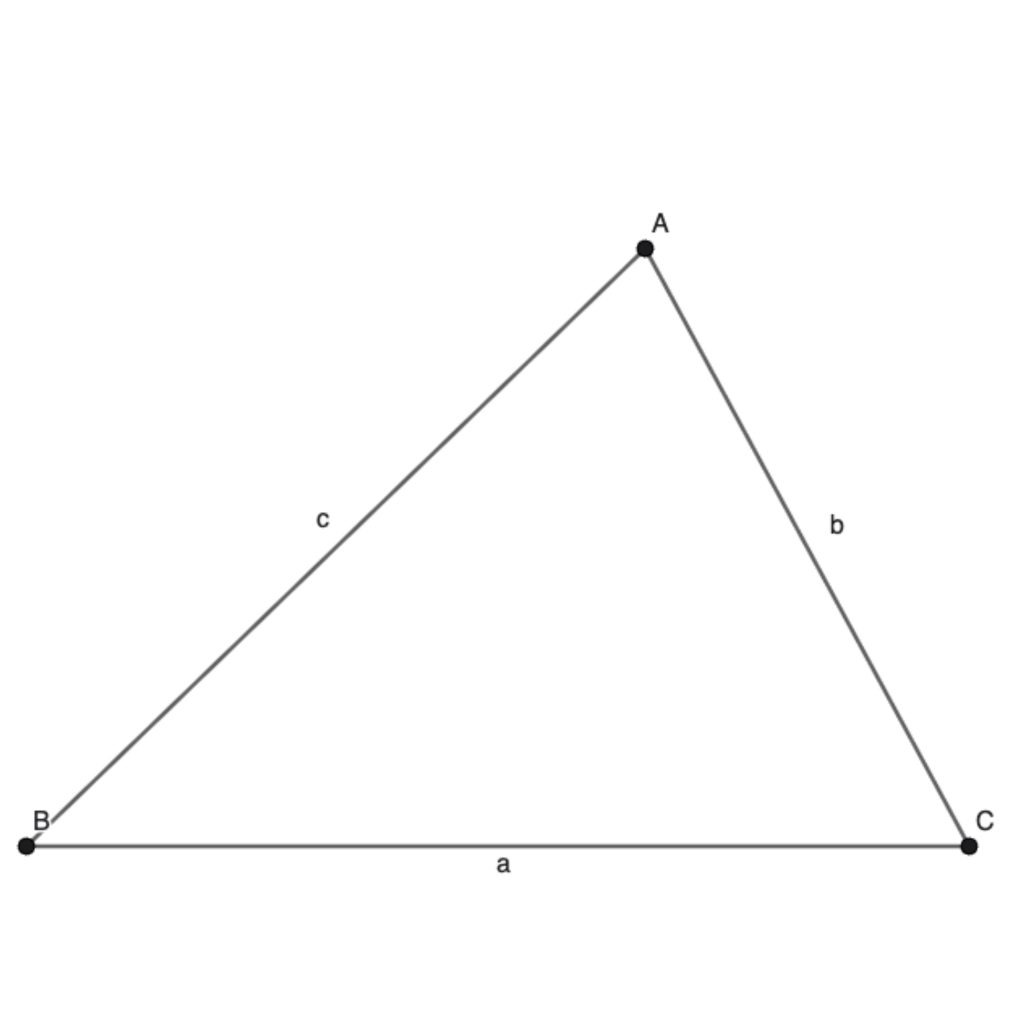

Isoperimetric Inequality on a Triangle

Let’s start things off with a simpler version of the problem. We will be proving the Isoperimetric inequality on a triangle.

The Isoperimetric inequality for triangles states that if L is the perimeter and A is the area

![]()

To prove this, we first need to prove AM-GM inequality.

AM-GM Inequality

The AM-GM inequality11 states for all nonnegative reals ![]()

![]()

The equality case holds when ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

We will prove this via Cauchy induction. Cauchy induction is a form of the regular induction. In Cauchy induction, we first prove the base case, which is with 2 elements. Then we prove all the cases with ![]() elements. Finally, we prove that given

elements. Finally, we prove that given ![]() elements work,

elements work, ![]() elements work.

elements work.

The base case is the AM-GM inequality with 2 elements.

![]()

The more obvious and boring way to prove this is by doing some simple algebra.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

But we are here to have fun, so here is a much more interesting proof.

We set the circle to have diameter ![]() , where

, where ![]() has length

has length ![]() and

and ![]() has length

has length ![]() .

. ![]() is perpendicular to

is perpendicular to ![]() and is the radius, so it has length

and is the radius, so it has length ![]() .

. ![]() is perpendicular to

is perpendicular to ![]() which makes

which makes ![]() .

.

By using Power of a point on the chords ![]() and

and ![]() , we can see that

, we can see that ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() . We can see that by changing

. We can see that by changing ![]() and

and ![]() , the position of the point

, the position of the point ![]() on the line

on the line ![]() changes. However, no matter where

changes. However, no matter where ![]() is,

is, ![]() will always be smaller than

will always be smaller than ![]() , which means

, which means ![]() .

.

Now that we are done with the base case, we want to take the first inductive step. Suppose AM-GM inequality works for ![]() elements. We want to prove that it works for

elements. We want to prove that it works for ![]() elements. Suppose that we have a list of

elements. Suppose that we have a list of ![]() elements

elements ![]() . We can split this into two sequences of

. We can split this into two sequences of ![]() elements

elements ![]() and

and ![]() . From this we can write two inequalities.

. From this we can write two inequalities.

![]()

![]()

Now we add them and divide by ![]() .

.

![]()

Notice that now we can apply AM-GM inequality on the ![]() elements

elements ![]() and

and ![]() to get

to get

![]()

Which means that

![]()

Since the base case is ![]() elements, this proves AM-GM inequality for all powers of 2.

elements, this proves AM-GM inequality for all powers of 2.

Now, we take the second inductive step. Assuming that AM-GM inequality works for ![]() elements, we must prove that it works for

elements, we must prove that it works for ![]() elements. First, we substitute

elements. First, we substitute ![]() with

with ![]() . Plugging it in, we get

. Plugging it in, we get

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{x_1 + ... + x_{n - 1} + \frac{x_1 + ... + x_{n - 1}}{n - 1}}{n} \geq \sqrt[n]{x_1...x_{n - 1}\left(\frac{x_1 + ... + x_{n - 1}}{n - 1}\right)}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e29c38df6b2d1ebd19c08491e26c680b_l3.png)

Note that because we assumed the inequality to be true with ![]() elements, equality must hold if and only if

elements, equality must hold if and only if ![]() . However, notice that if

. However, notice that if ![]() ,

, ![]() must be equal as well. So, the equality case holds if and only if

must be equal as well. So, the equality case holds if and only if ![]() .

.

We can now continue by multiplying ![]() to the numerator and the denominator of the left-hand side.

to the numerator and the denominator of the left-hand side.

![]()

Plugging it back in, we get

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{x_1 + ... + x_{n - 1}}{n - 1} \geq \sqrt[n]{x_1...x_{n - 1}\left(\frac{x_1 + ... + x_{n - 1}}{n - 1}\right)}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-532536cb6a2e7d546e1c034c90132626_l3.png)

![]()

![]()

![]()

Thus, by Cauchy induction, we have proved AM-GM inequality.

Proving the Triangle Case

First, we will define ![]() . Now, we will apply AM-GM inequality on the

. Now, we will apply AM-GM inequality on the ![]() terms

terms ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() to get

to get

![]()

![]()

![]()

Using Heron’s formula, we get

![]()

![]()

![]()

Adolf Hurwitz’s Proof of the Isoperimetric Inequality

The main idea for this proof is that it calculates the area of the shape, and compares it to another quantity using Wirtinger’s inequality. The other quantity is cleverly set up so that the result directly gives us the Isoperimetric inequality. We first parameterize the curve by arc length and then rescale to make it ![]() -periodic so that Fourier methods apply.

-periodic so that Fourier methods apply.

Lemma (Translation invariance and normalization)

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , be a simple closed

, be a simple closed ![]() curve parametrized by arc length. If we shift the entire curve by a fixed vector

curve parametrized by arc length. If we shift the entire curve by a fixed vector ![]() , the perimeter and enclosed area do not change. Indeed,

, the perimeter and enclosed area do not change. Indeed,

![]()

depends only on derivatives, so adding constants has no effect. For the area,

![]()

the shift adds ![]() , because the curve is closed. Therefore translation leaves

, because the curve is closed. Therefore translation leaves ![]() and

and ![]() unchanged. After we later rescale to periodic functions

unchanged. After we later rescale to periodic functions ![]() with

with ![]() , we may translate so that

, we may translate so that

![]()

Parameterizing by Arc Length

We start off by noticing that we can represent the closed curve using ![]() piecewise functions

piecewise functions ![]() and

and ![]() where

where ![]() that satisfy

that satisfy

(3) ![]()

We can make this assumption because this is what it means to parameterize by arc length. It essentially limits how much you go around the perimeter in each step to ![]() . We can think of this as a “speed” of

. We can think of this as a “speed” of ![]() .

.

Working with a curve defined by arc length allows us to fix the total perimeter while keeping the description smooth and continuous. To apply Fourier series conveniently, we now rescale this parameterization so that the functions repeat every ![]() .

.

Rescaling to  Periodicity

Periodicity

Because the functions ![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() periodic (the perimeter is a closed curve of length

periodic (the perimeter is a closed curve of length ![]() ), we can make new functions

), we can make new functions ![]() and

and ![]() to be functions of

to be functions of ![]() and

and ![]() so that they are

so that they are ![]() periodic, where

periodic, where ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

We will also define

![]()

Notice that we have the ability to shift the shape around the plane since it does not affect the inequality in any way. So, for later convenience, we will shift the graph so that ![]() . Now, we can take the derivative

. Now, we can take the derivative ![]() and plug it back into (3). Using the chain rule, we get

and plug it back into (3). Using the chain rule, we get

![]()

![]()

So,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[(f'(\theta))^2 + (g'(\theta))^2 = \left[\left(x'\left(\frac{L\theta}{2\pi}\right)\right)^2 + \left(y'\left(\frac{L\theta}{2\pi}\right)\right)^2\right] \cdot \left(\frac{L}{2\pi}\right)^2\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f51e00a172d7c5f8466c123f0f18800d_l3.png)

But because of (3), everything inside the square brackets equals to ![]() .

.

(4) ![]()

Now that ![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() -periodic, we can express the enclosed area in terms of these functions. Computing the area is the next step toward

-periodic, we can express the enclosed area in terms of these functions. Computing the area is the next step toward ![]() , since the inequality relates perimeter to area.

, since the inequality relates perimeter to area.

Writing the Area Integral in Terms of  and

and

Recall that the formula for the area enclosed by a curve is12‘13

(5) ![]()

This is similar to how the determinant of a matrix calculates the area of the shape it represents. In fact, the area of a triangle can be calculated by multiplying ![]() to the determinant of the matrix, similar to the equation above. Now we need to define and calculate a few conditions that we will use later. Because

to the determinant of the matrix, similar to the equation above. Now we need to define and calculate a few conditions that we will use later. Because

![]()

the following conditions hold.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Now we need to calculate what ![]() and

and ![]() are.

are.

![]()

By the chain rule,

![]()

![]()

Similarly,

![]()

Now, substituting everything back into (5) we get

![]()

(6) ![]()

We now use integration by parts. The formula for integration by parts comes from the product rule ![]() . Integrating on both sides gives us

. Integrating on both sides gives us ![]() where

where ![]() is the constant after integrating. Rearranging the equation results in

is the constant after integrating. Rearranging the equation results in ![]() . Since this equation works on a definite interval, the

. Since this equation works on a definite interval, the ![]() in

in ![]() will cancel out no matter what, so we can just remove it to get

will cancel out no matter what, so we can just remove it to get ![]() . Plugging in

. Plugging in ![]() and

and ![]() , we get

, we get

![]()

Since ![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() periodic functions,

periodic functions,

![]()

and

![]()

Then,

![]()

So,

![]()

Returning back to (6) we can rewrite it into this.

(7) ![]()

Our next goal is to rewrite the area integral into a form that can be directly compared with an integral involving the derivatives of ![]() and

and ![]() because the perimeter can be directly represented by them as mentioned in (4).

because the perimeter can be directly represented by them as mentioned in (4).

Reorganizing the Equation

We can complete the square so that (7) becomes

![]()

Because the last term is non-negative,

![]()

At this point, we can use Wirtinger’s inequality to relate the integral of ![]() to that of

to that of ![]() . This step is essential because it converts the geometric problem into an analytic inequality involving derivatives. By the lemma at the start of the proof, we may assume

. This step is essential because it converts the geometric problem into an analytic inequality involving derivatives. By the lemma at the start of the proof, we may assume ![]() , so we apply Wirtinger’s inequality to

, so we apply Wirtinger’s inequality to ![]() alone, which means that no condition on

alone, which means that no condition on ![]() is needed. Remember that Wirtinger’s inequality states that

is needed. Remember that Wirtinger’s inequality states that

![]()

It follows that

![]()

So,

![]()

We have now related the area to ![]() and

and ![]() , so we use (4), which links these derivatives to the fixed perimeter

, so we use (4), which links these derivatives to the fixed perimeter ![]() . Substituting (4) on the right hand side gives

. Substituting (4) on the right hand side gives

![]()

Rearranging the equation gives us the Isoperimetric inequality.

![]()

If equality holds in the Isoperimetric inequality, then every step above must also be an equality. The complete the square step forces ![]() when there is an equality. Since the integral of a non-negative quantity is equal to

when there is an equality. Since the integral of a non-negative quantity is equal to ![]() when that quantity is

when that quantity is ![]() , we get that

, we get that ![]() .

.

From Wirtinger’s inequality, equality happens only when the Fourier series of ![]() contains the first sine–cosine terms and no higher frequencies. This is called Fourier coefficient localization at

contains the first sine–cosine terms and no higher frequencies. This is called Fourier coefficient localization at ![]() . In this case,

. In this case, ![]() . Integrating on

. Integrating on ![]() tells us that

tells us that ![]() . Together, these functions

. Together, these functions ![]() trace a circle of radius

trace a circle of radius ![]() , meaning that equality holds for the Isoperimetric inequality when the curve is a circle.

, meaning that equality holds for the Isoperimetric inequality when the curve is a circle.

Generalization

The first step one should take after proving something is to attempt to generalize. We will not be able to prove these generalizations as they are outside the scope of this paper, but we will cover the ideas of how they work. The usual Isoperimetric inequality works on a ![]() dimensional plane. The natural move is to generalize to more dimensions. For example, in

dimensional plane. The natural move is to generalize to more dimensions. For example, in ![]() dimensional space, the inequality would relate the surface area to the volume of an object. It turns out that it is possible to generalize to any higher dimension14, but it is extremely complex.

dimensional space, the inequality would relate the surface area to the volume of an object. It turns out that it is possible to generalize to any higher dimension14, but it is extremely complex.

Another way of generalizing the inequality is to do it in different spaces.

For example, on a sphere, the Isoperimetric inequality becomes

![]()

where R is the radius of the sphere. Other generalizations include the Isoperimetric inequality in Hadamard Manifolds and in metric measure spaces.

Applications

This section presents several concrete uses of the isoperimetric principle. We first give two geometric examples that follow directly from ![]() , namely the maximal area with a straight shoreline and an area bound for curves of constant width using

, namely the maximal area with a straight shoreline and an area bound for curves of constant width using ![]() . We then include an advanced example, Cheeger’s inequality, which links a geometric isoperimetric ratio to the rate at which heat or vibrations even out in a region. Full background from partial differential equations is not required here. The key point is that the same boundary-area tradeoff that makes circles optimal in the Isoperimetric inequality also limits diffusion in analytic settings.

. We then include an advanced example, Cheeger’s inequality, which links a geometric isoperimetric ratio to the rate at which heat or vibrations even out in a region. Full background from partial differential equations is not required here. The key point is that the same boundary-area tradeoff that makes circles optimal in the Isoperimetric inequality also limits diffusion in analytic settings.

Dido’s Problem

Dido’s problem asks for the maximum area that can be enclosed by a line of a fixed length, given that a straight coastline forms the remainder of the boundary.

Let the boundary that isn’t the coastline be an arc of length ![]() . Reflect the region across the line. The reflected shape is a closed region with perimeter

. Reflect the region across the line. The reflected shape is a closed region with perimeter ![]() and area

and area ![]() . By the Isoperimetric inequality,

. By the Isoperimetric inequality,

![]()

![]()

Equality holds exactly when the doubled region is a circle, so the original region is a semicircle whose arc length is ![]() .

.

Curves of Constant Width

Let a convex plane curve have constant width ![]() . Barbier’s theorem15 gives the exact perimeter

. Barbier’s theorem15 gives the exact perimeter ![]() . Substituting into

. Substituting into ![]() gives us

gives us

![]()

with equality only for the circle of diameter ![]() . This quantifies how far any constant width shape is from the optimal area for its fixed width.16

. This quantifies how far any constant width shape is from the optimal area for its fixed width.16

Cheeger’s inequality

The Isoperimetric inequality has many extensions beyond geometry. One deep example appears in mathematical physics and analysis, known as Cheeger’s inequality. This result connects the shape of a region to how quickly heat or energy spreads inside it.

Without going into full technical detail, we can describe the main idea. For a region ![]() in the plane, the Cheeger constant

in the plane, the Cheeger constant ![]() measures how easily the region can be divided into two parts compared to its boundary length. A region with a narrow “neck” has a small

measures how easily the region can be divided into two parts compared to its boundary length. A region with a narrow “neck” has a small ![]() , while a compact, round region has a large one. Meanwhile, the first nonzero eigenvalue

, while a compact, round region has a large one. Meanwhile, the first nonzero eigenvalue ![]() of the Laplacian, a differential operator that models heat flow, measures how fast heat or vibrations even out in

of the Laplacian, a differential operator that models heat flow, measures how fast heat or vibrations even out in ![]() .

.

Cheeger’s inequality states that

![]()

This means that regions which are close to being isoperimetric (large ![]() , like circles) allow faster diffusion or vibration, while regions with thin bottlenecks (small

, like circles) allow faster diffusion or vibration, while regions with thin bottlenecks (small ![]() ) slow it down. Although this connection involves advanced ideas such as eigenvalues and differential operators, it shows that the same geometric principle behind the Isoperimetric inequality also governs how shapes behave in physics and analysis.17

) slow it down. Although this connection involves advanced ideas such as eigenvalues and differential operators, it shows that the same geometric principle behind the Isoperimetric inequality also governs how shapes behave in physics and analysis.17

Discussion

Hurwitz’s proof shows that algebra and analysis can be used to solve what first looks like a geometry problem. Instead of working with shapes directly, the proof rewrites the boundary as functions and then analyzes those functions using Fourier series. This makes the argument more general and shows how inequalities in analysis can describe geometric ideas. Compared with older geometric proofs, Hurwitz’s method is appealing because every step follows from clear algebraic or analytic reasoning.

The approach also connects the Isoperimetric inequality to many areas of modern mathematics, like Fourier analysis, calculus of variations, and spectral geometry. These connections show that the same ideas behind a simple shape problem can also describe how heat spreads, how waves move, or how space itself behaves in higher dimensions. Overall, Hurwitz’s proof gives an elegant and understandable way to see one of the oldest mathematical inequalities through the lens of modern analysis.

Conclusion

Throughout this paper, we studied the Isoperimetric inequality from both a historical and mathematical point of view. We began with the story of Queen Dido and the founding of Carthage, then reviewed the main tools used in the proof, such as Fourier series, Parseval’s theorem, Wirtinger’s inequality, and the AM–GM inequality. After proving a simpler version for triangles, we went through Hurwitz’s full analytic proof step by step and looked at a few generalizations and applications.

Hurwitz’s approach is interesting because it turns a geometric problem into one that can be solved with algebra and calculus. Instead of using geometric constructions, the proof represents the curve with periodic functions and studies them using Fourier analysis. Parseval’s theorem connects the geometry of the curve to these functions, and Wirtinger’s inequality provides the final comparison needed for the result.

This analytic method is clear, logical, and easier to follow than most other proofs once the main ideas are known. It also explains why the circle is the only shape that achieves equality in the inequality. Hurwitz’s proof shows that even an old geometric question can be understood in a new way by combining simple analytic ideas together.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Zarif Ahsan for his guidance throughout writing this paper. Thanks to Simon Rubinstein-Salzedo of the Euler Circle for providing the opportunity for independent research for the summer.

References

- R. Osserman. The isoperimetric inequality. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 84(6), 1182–1238 (1978). [↩]

- E. Hoisington. An exposition of Hurwitz’s isoperimetric method. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.06347 (2019). [↩]

- A. Treibergs. Mixed area and the isoperimetric inequality (2009). https://www.math.utah.edu/~treiberg/MixedAreaSlides.pdf [↩]

- R. Perumal, R. Gopal, and R. Selvakumar. “A study about Fourier series: Mathematical and graphical models and application in electric current and square oscillations.” ResearchGate (2021). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350973707 [↩]

- W. Kaplan. Advanced Calculus, 4th ed. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA (1991), p. 519. [↩]

- E. W. Weisstein. Parseval’s theorem. MathWorld (Wolfram). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/ParsevalsTheorem.html [↩]

- MIT OpenCourseWare. Orthogonality relations (2011). https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/18-03sc-differential-equations-fall-2011/ [↩]

- S. S. Dragomir. “Bessel’s inequality and its extensions in inner product spaces.” Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 329(2), 1311–1320 (2007). [↩]

- W. E. Milne. “Integral inequalities of the Wirtinger type.” Duke Mathematical Journal 25(3), 459–464 (1958). [↩]

- P. Singh, A. Singhal, B. Fatimah, A. Gupta, and S. D. Joshi. “Proper definitions and demonstration of Dirichlet conditions.” TechRxiv preprint (2021). https://www.techrxiv.org/doi/full/10.36227/techrxiv.14761539.v1 [↩]

- M. D. Hirschhorn. “The AM–GM inequality.” The Mathematical Intelligencer 29(4), 7 (2007). DOI:10.1007/BF02986168. [↩]

- R. F. Muirhead. “A proof of Green’s theorem and its application to area computation.” The Mathematical Gazette 66(437), 105–107 (1982). [↩]

- D. Q. Nykamp. Using Green’s theorem to find area. Math Insight. https://mathinsight.org/greens_theorem_find_area [↩]

- X. Cabré. “Isoperimetric, Sobolev, and eigenvalue inequalities via the Alexandroff–Bakelman–Pucci method: A survey.” Chinese Annals of Mathematics, Series B 38(1), 1–14 (2017). [↩]

- P. J. Davis. “Barbier’s Theorem and Curves of Constant Width.” In Ingenuity in Mathematics, pp. 157–164. The Mathematical Association of America, Washington, D.C. (1979). [↩]

- B. Kawohl, G. Sweers. On a formula for sets of constant width in 2D. Communications in Pure and Applied Analysis 18(6), 2825–2837 (2019). [↩]

- J. Cheeger. A lower bound for the smallest eigenvalue of the Laplacian. In Problems in Analysis, 195–199. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ (1970). [↩]