Abstract

Background and objective: Chronic psychological stress activates the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system (SNS), resulting in prolonged stress hormone release. These stress hormones can affect immunity by changing the function of key immune cells. Although psychoneuroimmunology has produced extensive research on stress-related immune changes, findings are often fragmented across cell types, models, and stress paradigms. This narrative review will highlight the effects on T cells, B cells, cytokines, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and examine how chronic stress disrupts the immune balance.

Methods: A structured search of the literature on PubMed and Google Scholar was conducted using keywords related to stress hormones and immune function. Peer-reviewed studies that assessed cellular changes to the immune system were preferred.

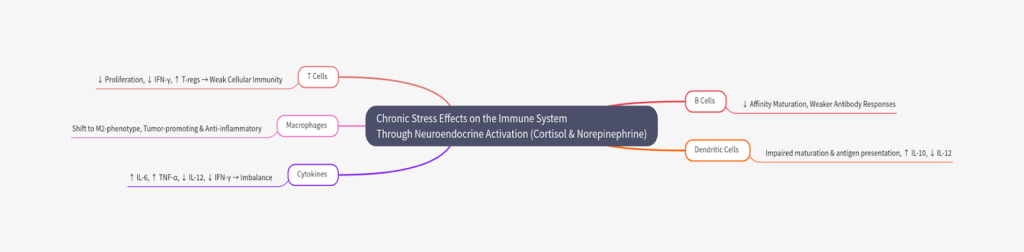

Results: Across studies, chronic stress–related β₂-adrenergic and glucocorticoid signaling in T cells is associated with reduced proliferation of effector T-cells and the expansion of T-regulatory cells. Chronic stress disrupts cytokine signalling through elevated anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines. B-cell studies have shown impaired germinal center reactions, resulting in reduced antibody production and diminished maturation. Findings across animal and human studies suggest that during chronic stress, macrophages polarise toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, while dendritic cells exhibit impaired maturation and antigen presentation.

Conclusions: By reviewing these cellular mechanisms together, this review creates a picture of how the activation of neuroendocrine hormones, during chronic stress, weakens host defence and increases autoimmune disease susceptibility. This can lead to various disease outcomes that are detrimental to the immune system.

Keywords: Chronic stress, Immunosuppression, T-cells, Cytokines, Neuroendocrine system, B-cells, Macrophages, Dendritic cells.

Introduction

Background and context

Chronic psychological stress is defined as the neurological response to experiencing environmental demands or events that surpass one’s ability to cope, which persists over an extended period of time. Psychological stress influences the immune system through the sustained activation of neuroendocrine pathways, most notably the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)1. Prolonged engagement of these systems leads to continuous secretion of stress-related hormones, such as glucocorticoids and catecholamines, which play a central role in shaping immune regulation2. A substantial body of human and animal research has demonstrated that chronic elevations in these hormones do not produce transient immune changes, but instead induce lasting alterations in immune cell behaviour, signaling, and functional capacity. Across experimental and clinical studies, chronic psychological stress has been consistently linked to impaired antiviral immune responses, diminished vaccine efficacy, and disruptions in immune surveillance mechanisms that are critical for maintaining homeostasis in the body2. At the same time, sustained stress exposure is associated with increased inflammatory signaling, shown by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, that may persist even in the presence of immunosuppressive hormonal signals3. This shows how prolonged exposure to stress hormones can cause immune dysregulation in the human body and can make one more susceptible to autoimmune diseases.

Problem statement and rationale

This review addresses the question “How does chronic psychological stress alter the function of key immune cells, specifically T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and cytokine networks, to drive immune dysregulation and reduced host defense?” While various studies have investigated stress-induced changes within immune cells, findings are often distributed across cell types, models, and stress paradigms. As a result, cellular-level insights remain fragmented, limiting the ability to compare convergent and divergent stress responses across the immune system.

Significance and purpose

This review specifically examines how stress hormones and sustained neuroendocrine activation influence the function of immune cells, such as T lymphocytes, cytokines, B lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. By synthesising recent findings, this review highlights the mechanisms through which sustained neuroendocrine activation may contribute to increased vulnerability to infections, immune dysregulation, and can even lead to autoimmunity.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to:

- Examine how chronic stress hormones alter the function of immune cells.

- Synthesise findings across studies to provide a mechanistic view of stress-induced immune suppression.

Scope and limitations

This narrative review is focused on studies that investigate the cellular and molecular mechanisms of immune dysregulation in the context of chronic psychological stress. It does not include acute stress responses, non-cellular pathways, systems that are not directly related to the immune system, and studies exclusively focused on behavioural or psychological interventions. While animal studies are considered when relevant, emphasis is placed on human data, which is limited.

Methodology overview

A structured search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar from the last two decades. Keywords included “chronic stress”, “immune suppression,” “T cells,” “cytokines,” “neuroendocrine system,” “B cells,” “Macrophages,” “Dendritic cells.” Both original research and review studies were considered, with an emphasis given to recent publications. Articles were selected for relevance to cellular mechanisms and were organised by immune cell type for analysis in the following sections.

Methods

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted on PubMed, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect between March to June 2025, covering literature published from 1999 to 2025. Search terms included “chronic stress,” “immune suppression,” “glucocorticoids,” “norepinephrine,” “T cell signalling,” “B cell function,” “macrophage cells,” “dendritic cell maturation,” and “cytokine imbalance.” Different combinations of the search terms were added during the search to get the most relevant papers. Examples of search strings are: (“chronic stress” and “immune cells”), (“glucocorticoids” and “immune cells”), and (“chronic stress” and “macrophages”). Articles were screened for relevance to cellular-level mechanisms of immune modulation by stress hormones and synthesised. Searches were limited to peer-reviewed articles published in English between the time period 1999 to 2025. Both human studies and relevant animal models were considered, but emphasis was put on human studies. Approximately 50-70 articles were initially identified across databases, of which around 20 studies were selected for inclusion based on relevance to the immune cell.

Inclusion criteria

The studies had to be between 1999 and 2025, with priority given to papers after 2020 to ensure inclusion of recent findings, although foundational older studies were also incorporated where relevant. Only peer-reviewed primary research and review articles published in English were considered. The search was focused on the cellular or molecular mechanisms of immune modulation under chronic psychological stress. It was ensured that the key findings were from research conducted in human subjects or animal models with relevance to human immunity and chronic stress. This means that the studies used in this review examined immune cell types and pathways that are conserved in humans and human-derived immune cell models/mammalian animal models relevant to chronic psychological stress.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they focused on acute stress rather than chronic psychological stress, did not involve cellular and molecular pathways of the immune system, or focused on behavioural and psychological outcomes. Articles were screened in a multi-stage process. Following the initial database searches, approximately 65 articles were identified across PubMed, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect. After removal of duplicates, around 58 articles remained for screening. Titles were first screened for relevance to chronic stress and the immune system. Abstract screening was performed for almost 38 articles, using the predefined exclusion criteria. Following abstract screening, approximately 34 articles were selected for full-text review. Full-text assessment led to the inclusion of approximately 20 studies that directly examined cellular-level immune modulation under chronic psychological stress. The final set of included studies was organized by immune cell type to facilitate comparative synthesis across sections.

Data extraction

For each study, the following variables were extracted and recorded for a structured comparison across all the findings:

- Study model (human observational, human experimental, or animal model)

- Species and tissue source (e.g., peripheral blood, lymphoid tissue, tumor microenvironment)

- Duration of stress exposure (acute vs chronic)

- Primary neuroendocrine mediators examined (e.g., cortisol, glucocorticoids, catecholamines, norepinephrine)

- Immune cell type(s) studied (e.g., T cells, B cells, macrophages, cytokines, dendritic cells)

- Cellular or molecular outcomes measured (e.g., proliferation, polarization, cytokine secretion, receptor expression, antigen presentation)

- Direction immune modulation (e.g., suppression, activation, or mixed effects)

Data was grouped based on immune cell type to structure this review.

Synthesis method

Given the diversity of study designs and findings, a narrative synthesis approach was used. Findings were grouped by immune cell types (T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, cytokines) and compared across studies to identify consistent patterns, contradictions, and emerging pathways. Wherever possible, links were made between cellular-level changes and broader health outcomes (e.g., infection and autoimmunity).

Discussion

T cells (T lymphocytes)

Chronic stress consistently impairs T-cell–mediated antiviral immunity through neuroendocrine signalling pathways. They alter cell proliferation, cytokine production, and metabolic capacity. Across animal models, in vitro studies, and human studies, adrenergic and glucocorticoid (GC) signalling emerge as key regulators of these effects. T cells participate in defence against virally infected cells. In response to a pathogen, T cells undergo a series of cell divisions to generate enough effector T cells; this is critical for a successful adaptive immune response. One of the central regulatory pathways between the neuroendocrine system and T cells is mediated by the expression of the β2-adrenergic receptor on T cells. Engagement of the β2-adrenergic receptor (a G protein-coupled receptor) triggers a signalling cascade that increases cAMP and activates protein kinase A4. When β2-adrenergic receptors on Th1 cells (also known as Type 1 helper T cells, a subset of CD4+ T cells that play a crucial role in cell-mediated immunity) are engaged, the IFN-γ production can be affected depending on the time of Th1 cell activation. IFNs are a family of cytokines (signalling proteins) produced by immune cells in response to pathogens, aiming to keep the balance between Th1 and Th2 cells, activate macrophages to fight pathogens, and promote antiviral immunity. In vitro studies show that IFN-γ production will be decreased in Th1 cells in which β2-adrenergic receptor engagement occurred before their cell activation. However, after cell activation, the receptor engagement leads to an increase in the level of IFN-γ production in comparison with the control cell that is activated alone. These findings suggest that adrenergic regulation of T-cell cytokine production is highly context-dependent, and the changes in production level may decrease the body’s immunity and impair immune cell functions.

It is important to discuss the role of norepinephrine as it is one of the main stress mediators released during chronic stress; it is a link between immune dysregulation and chronic stress. It comes from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and adrenal medulla. For determining the effect of NE (Norepinephrine) on the memory CD8+ T cells, the in vitro NE-treated CD8+ T cells were stimulated by antibodies specific for CD3 and CD28 (CD3 is essential for recognising antigens and CD28 acts as a co-stimulatory receptor, enhancing T cell activation). In addition, memory T cells from human cells of individuals with low and high levels of NE were analysed. It was determined that an elevated level of β2-adrenergic receptors was expressed in memory T cells in comparison with naïve T cells, and NE-dependent effects on these cells were mediated by β2-adrenergic receptors. They demonstrated that the expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as IL-6 and TNF) was increased while growth-related cytokine production was reduced5. Simply, chronic stress can make these T cells produce inflammation and less capable of expanding in large numbers to fight infections.

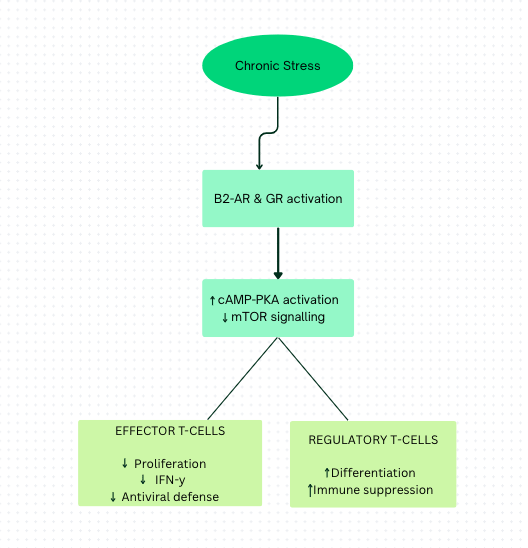

The second stress mediator, glucocorticoid (steroid hormones, such as cortisol), leads to most of the immunosuppressive effects of chronic stress. It can be hypothesised that immunopathology or immunoprotective effects of chronic stress may influence glucocorticoid signalling. GC, a potent immunomodulator and immunosuppressor, is produced by the adrenal cortex in response to pituitary ACTH and ultimately triggers negative feedback on the HPA axis, activated during stress. These effects influence T cell survival. Animal and cell culture studies demonstrate that stress-induced glucocorticoids cause apoptosis in immature T cells but also promote regulatory T cells (T-regs). GCs can inhibit glycolysis in T cells and reduce intercellular glucose levels. The function of activated T cells (Th1, Th2, and Th17) depends on ATP produced via glycolysis. Consequently, these cells are more susceptible to starvation induced by stress compared to naïve T cells and T-reg cells, where the TCA cycle and OXPHOS pathways can be used to provide cell essential ATPs6. These mechanisms are summarized in Figure 1, which presents a conceptual model of how chronic stress–induced activation of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and β₂-adrenergic receptors (β₂-AR) alters T-cell metabolism and differentiation. There is reduced effector T-cell (Th1, Th2, and Th17) responses, as they lack the energy needed to function, thereby weakening the body’s ability to combat viruses and other infections. Simultaneously, cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate), produced during stress to decrease glycolysis, inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling6. mTOR normally increases glycolysis and inhibits OXPHOS to limit energy supply to T-reg cells. cAMP consequently removes OXPHOS inhibition, allowing T-reg cells to obtain energy and leading to their increased number. This further suppresses overall immune activity. Collectively, these alterations represent a direct cellular mechanism through which chronic stress promotes immune suppression.

Furthermore, Long-term high cortisol exposure can induce immune system dysregulation and immunosuppression. Cortisol exposure over an extended period is shown to decrease T cell activation and proliferation, compromising the body’s ability to mount effective immune responses7. For example, the human study done by Zhang et al. (2020) found that high cortisol levels were linked to decreased T cell activation and proliferation in patients with chronic stress, emphasising how elevated glucocorticoids can impair adaptive immune responses, increasing vulnerability to infections and reducing vaccine efficacy8.

Moreover, Prolonged catecholamine exposure (a group of hormones and neurotransmitters that play a central role in the body’s stress response) has been shown to downregulate the expression of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell receptors, leading to decreased T cell activation and proliferation. This dysregulation may contribute to a weakened adaptive immune response with significant health implications7, as there are lower lymphocytes to fight the infections and create lower antiviral immunity.

Human observational studies show reduced effector T-cell proliferation, increased T-reg cell proliferation, and lower antiviral cytokine output in individuals exposed to chronic stress. This supports a clinically relevant association between stress and impaired adaptive immunity. Animal models and in vitro experiments demonstrate that stress mediators signal through glucocorticoid receptors and β₂-adrenergic receptors to increase intracellular cAMP, suppress glycolysis, and alter IFN-γ production in a timing and activation-dependent manner. Notably, β₂-adrenergic receptor engagement suppresses IFN-γ when signalling occurs before T-cell activation but may enhance cytokine output after activation, highlighting the context-specific nature of stress effects on T-cell responses. The findings suggest that chronic stress reprograms T-cell metabolism and differentiation, leading to reduced effective responses while favouring regulatory phenotypes. Therefore, it weakens adaptive immune defence under prolonged stress conditions. T cells are major producers and regulators of cytokines; stress-induced alterations in T-cell function have downstream effects on cytokine signalling networks across the immune system.

Cytokines

The connection between chronic stress and the production of cytokines is dynamic and complex. Studies examining chronic stress exerts a dual influence on cytokine levels by increasing both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. However, this is dependent on the stress paradigm and the species being studied.

Several studies suggest that stress can induce a state of immune activation, where immune cells such as macrophages and T cells become activated in a hyper-responsive way under the influence of neurotransmitters associated with stress (eg, norepinephrine), which can also promote secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines7. Furthermore, human studies suggest that chronic stress may also induce changes in the gene expression of cytokines involved in cell signalling that may lead to a chronic state of inflammation9. Various animal and human studies suggest that chronic stress often leads to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 (Interleukin-6), TNF-α (Tumour Necrosis Factor alpha), and IL-1 (Interleukin-1)3. The activation of the HPA axis under stress conditions results in the release of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. In animal studies with rats, cortisol reduces the inflammatory response in acute or initial stress exposure, but with prolonged stress, continued elevation of cortisol contributes to increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The persistent elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been linked to a plethora of health conditions; in particular, concerning cardiovascular health, metabolic syndrome, and mental health disorders.

A study revealed that individuals experiencing chronic stress exhibited significantly higher levels of IL-6, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease were elevated as well. This is important because chronic stress leads to increased arterial stiffness (the loss of the arteries’ ability to expand and contract normally) and endothelial dysfunction (the impaired endothelium’s ability to properly regulate blood vessel tone, inflammation, and other functions); both are critical contributors to the development of cardiovascular disease. In addition, the persistent inflammatory state associated with stress can amplify these physiological changes, as stress-induced inflammation may lead to systemic damage to blood vessels and promote atherosclerosis, a disease where plaque builds up inside your arteries, causing them to narrow and harden7. For example, studies involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis (a chronic autoimmune disease that primarily affects the joints) indicate that individuals with higher stress levels reported increased disease activity and more frequent flare-ups10. Stress management techniques, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, have been shown to reduce disease severity, further showing that psychological health interventions can have a significant effect on physical health.

In some human studies, chronic stress has also been associated with increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 (interleukin-10) and TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta). This, in turn, may represent an adaptation to counterbalance pro-inflammatory cytokines11. However, while elevated levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines may seem beneficial, chronic stress can disrupt the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. Evidence suggests that the chronic elevation of both types of cytokines may lead to immune dysregulation. Increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines may not compensate for the effects of sustained pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to either immune suppression or triggering autoimmune disorders11. Over prolonged stress exposure, certain immune cells may exhibit reduced responsiveness to cortisol, a process that is called glucocorticoid resistance1. This leads to a decrease in the expression of cortisol receptors. A decreased level of receptor expression leads to limited anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol, which further leads to chronic inflammation. There are fewer immunosuppressants in the system, thus more pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are leading to the chronic inflammation. This triggers immune dysregulation, contributing to the onset and flare-ups of various autoimmune conditions.

Overall, these findings highlight that cytokine responses to chronic stress are highly dependent on the scenario, varying by immune cell type, tissue compartment, stress duration, and study model. Multiple human studies report elevated circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, particularly in individuals experiencing prolonged stress. Experimental animal models further suggest that stress-related neurotransmitters can contribute to heightened inflammatory signaling under specific stress paradigms. In contrast, several human studies also show increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which may represent compensatory regulatory responses during certain phases of chronic stress. Evidence from animal models indicates that while glucocorticoids exert anti-inflammatory effects during acute or early stress exposure, prolonged stress may be associated with reduced glucocorticoid sensitivity in select immune cell populations, permitting sustained cytokine dysregulation. Disruption of cytokine signalling under chronic stress has direct consequences for B-cell activation, germinal centre formation, and antibody production.

B cells (B lymphocytes)

Chronic stress disrupts B-cell survival, maturation, and antibody production, therefore weakening adaptive immune protection. B-cell–mediated immunity is particularly sensitive to chronic stress due to its dependence on cytokines and T-cells. B-cell development mainly occurs in the bone marrow. Here, hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into pro-B and then pre-B cells, undergoing several key developmental stages of random recombination of the B cell receptor heavy and light chains to create lymphocytes capable of responding to an incredibly wide range of immunogens. The main phases of B-cell development and differentiation are outlined in Figure 2, which offers a structural framework for comprehending how hormonal changes brought on by stress alter these processes. Self-reactivity, determined by at least three checkpoints (immature, transitional, and activated naïve B cell stages), must be removed for them to move to secondary immune organs as naïve B cells. Naïve B1 B cells have limited B cell receptor diversity and are predominantly found in the peritoneal (abdominal organs) and pleural (lungs) cavities. B2 follicular naïve B cells comprise the majority of B cells in lymphoid organs, namely the spleen. Following encounters with their antigen, a subset of activated B cells migrates to germinal centres to undergo somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination to support affinity maturation. From there, maturing B cells become memory B cells or antibody-secreting cells. A separate subset of antigen-activated B cells will mature into short-lived plasma blasts outside of lymphoid structures, while others become long-lived plasma cells (PC). Once activated, the functions of various B cell subsets can be classified into several domains12:

- producers of antibodies that, once created and bound to an antigen, promote complement signalling as well as antigen neutralisation, antigen opsonisation (coating with antibodies), and ultimately destruction by other immune cells,

- antigen presenters

- cytokine and trophic factor secretors

- immune response regulators

- memory cells that enable a more rapid and specific threat response in future encounters with that specific antigen.

Findings from several in vitro studies indicate that chronic exposure to glucocorticoids makes B cells, and particularly immature B cells, more susceptible to apoptotic consequences. The consequences are neurodegenerative diseases and organ damage in excessive apoptosis and autoimmune diseases in insufficient apoptosis, with exposure to high levels of corticosteroids12. Further, in long-term cultured B lymphoblastoid (a type of cell line created by infecting B lymphocytes with the Epstein-Barr virus) collected from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) patients and healthy controls, basal GR expression was elevated in depressed patients but showed a larger reduction in expression when exposed to hydrocortisone stimulation13. This reflects a state of glucocorticoid resistance, in which receptors are overexpressed but functionally desensitised, contributing to impaired HPA axis feedback and immune dysregulation under chronic stress. Notably, B cell development in these mice is impaired, as is the B cell-driven antibody response to infection12. This indicates that B-cell deficiency may be partially involved in poorly adaptive stress responses and social interactions.

Stress effects on immunity are context-dependent, as evidenced by the inconsistent results of human studies looking at B-cell effector function. A key effector function of B cells is their capacity to produce antibodies, including IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM. Antibody production ability of B cells can have important functional consequences for the CNS. For instance, production of IgM may play a critical role in myelin development, a tightly regulated process dependent on local microenvironment signalling identified that B cells, specifically B1a B cells, are recruited to the choroid plexus and meningeal spaces via CXCL13 and support oligodendrocyte proliferation via IgM secretion. Relative to mentally healthy control subjects, noted that depressed populations showed reductions in serum IgA, but not IgM or IgG levels. However, increased IgA was reported in patients with MDD14. While chronically stressed humans showed an age-related increase in IgA or decrease in IgM, highlighting the stress-induced disruption of B cell effector functions12. This suggests that altered production of antibodies is dependent on various factors (age and stress paradigms). The study emphasised that chronic stress can reduce the production of antibodies that not only harm the immune system but also the CNS.

Chronic stress can also lead to decreased T and B lymphocyte proliferation, which leads to improper adaptive immune responses and increased susceptibility to infections12. For example, a study on individuals with chronic illness found that those experiencing chronic stress had significantly reduced T-cell counts and antibody responses12. It was also found that individuals with chronic stress were more prone to developing upper respiratory infections7. This increased susceptibility was linked to impaired immune responses, emphasising the clinical relevance of stress management.

Evidence from multiple study designs indicates that chronic psychological stress is associated with dysregulation of B-cells. There is altered B-cell survival, impaired maturation, and changes in antibody production. In vitro and animal studies provide strong evidence that prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids increases apoptotic susceptibility in immature B cells and induces glucocorticoid receptor desensitisation. This disrupts normal developmental checkpoints and regulatory feedback. Human observational studies report variable alterations in immunoglobulin profiles, including changes in IgA and IgM levels, suggesting that stress-related effects on B-cell effector function are influenced by age, stress duration, and immune status. Taken together, the literature supports the conclusion that chronic stress does not uniformly suppress B-cell function but instead induces heterogeneous, stress- and context-specific alterations that weaken effective antibody-mediated immune protection. While chronic stress disrupts adaptive immunity by impairing B-cell maturation and antibody production, its effects are not limited to lymphocytes; stress hormones also profoundly reshape innate immune responses, particularly macrophage activation and inflammatory regulation.

Macrophages

Chronic psychological stress alters macrophage function by shifting macrophage activation states and cytokine output, thereby contributing to dysregulated innate immune responses. Macrophages (MΦs) are key components of the innate immune system, responsible for pathogen recognition, phagocytosis, cytokine secretion, and the initiation of inflammatory and repair processes. Upon encountering pathogens, apoptotic cells, or cellular debris, macrophages become activated and coordinate early immune defence and tissue homeostasis. Macrophages are commonly described along a functional spectrum that includes classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) states15. M1 macrophages fight infection by engulfing pathogens and releasing inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) using inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). On the other hand, M2 macrophages are associated with tissue repair, immune regulation, and extracellular matrix remodelling through the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Although both activation states are physiologically necessary, an imbalance between these phenotypes can impair effective host defence.

Evidence from experimental animal and in vitro studies suggests that chronic exposure to stress mediators moves macrophage activation away from pathogen-clearing phenotypes and toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2)16. This shift is associated with reduced phagocytic capacity, impaired pathogen clearance, and altered cytokine secretion (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 signalling)17. Such changes suggest that chronic stress does not uniformly suppress macrophage activity but instead promotes an immune state where there is inefficient defence and prolonged inflammatory signalling.

Glucocorticoids further modulate macrophage function by disrupting phagocytic signalling pathways, including the balance between the ‘eat me’ signal receptor (LRP1) and the ‘do not eat me’ signal receptor (SIRPα)18. Thus, they block macrophages’ ability to kill cells by giving confusing signals. Evidence for these effects is strong in animal and cell culture models; however, human studies are largely observational, linking chronic stress to altered inflammatory profiles rather than establishing direct causality. Collectively, these findings indicate that stress-induced macrophage reprogramming contributes to innate immune dysregulation and increased susceptibility to infection. While macrophages shape the inflammatory environment during chronic stress, effective immune defence also depends on efficient antigen presentation, linking innate immune alterations to downstream effects on dendritic cell maturation and adaptive immune activation.

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are essential cells of the immune system, acting as antigen-presenting cells that initiate and regulate immune responses. DCs capture antigens from pathogens or damaged cells, process them, and present them to T-cells in lymphoid organs, thus serving as a critical link between the innate and adaptive immune systems. There are several types of dendritic cells, each defined by its specialised function. Conventional dendritic cells (CDCs) are highly effective at presenting antigens and activating T-cells. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs) are known for their ability to produce large amounts of type I interferons, especially during viral infections. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells are generated in response to inflammation and help in amplifying immune responses during infection or injury. Together, these subsets ensure a coordinated and effective immune defence. Chronic stress negatively impacts their function through prolonged elevation of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. Evidence from animal and human studies shows that stress hormones impair DC maturation, reduce their ability to present antigens, and suppress cytokine production, especially IL-12, which is vital for T-cell activation. Chronic stress also lowers the number of circulating DCs and disrupts their migration to lymphoid organs, weakening immune surveillance18.

Evidence in human studies shows that DCs differentiated in the presence of dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid. They remained at an immature stage, and Dex also partially blocked the terminal maturation of already differentiated DC. These Dex-DCs expressed low levels of CD1a (a cell surface marker used to classify monocyte-derived dendritic cells) and, unlike untreated cells, high levels of CD14 and CD16 (cell surface markers used to distinguish different monocyte subpopulations). Molecules involved in antigen presentation (CD40, CD86, CD54) were also impaired. In contrast, molecules involved in antigen uptake (mannose receptor, CD32) and cell adhesion (CD11/CD18, CD54) had increased expression in human studies. Dex-DC showed a higher endocytic activity (capturing many antigens), a lower APC function, thus they are poor at activating T cells, meaning weaker adaptive immunity and a lower capacity to secrete cytokines than untreated cells19. Together, these findings show that GC signalling keeps dendritic cells in an immature phenotype and impairs mature dendritic cells, thereby weakening their role in adaptive immunity and not allowing them to activate other immune system cells.

Chronic psychological stress is consistently associated with impaired dendritic cell (DC) function. Evidence from animal models and human studies indicates that stress-related hormones promote the maintenance of dendritic cells in an immature state, thereby reducing their capacity for antigen processing and presentation. This functional immaturity is associated with reduced production of IL-12, a cytokine essential for Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ production, and with increased secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10. Consequently, impaired DC signalling limits effective T-cell priming and skews immune responses toward immunosuppression. While animal studies provide mechanistic insight into glucocorticoid- and catecholamine-mediated suppression of DC maturation, human studies largely demonstrate associative reductions in IL-12–dependent immune activation under chronic stress. Together, these findings suggest that stress-induced dendritic cell dysfunction contributes to weakened adaptive immunity and increased susceptibility to infection.

After collective evaluation, the results presented in this paper lend support to an integrated model in which chronic stress modifies immune function by persistently activating neuroendocrine pathways. Long-term exposure can cause cell-type-specific changes that collectively skew the immune system towards altered immune regulation and decreased protective responses. At the level of adaptive immunity, chronic stress reduces effector T-cell proliferation, cytokine production, and antiviral capacity while promoting the expansion of regulatory T cells. In parallel, stress-related hormonal signaling impairs B-cell germinal center reactions, affinity maturation, and antibody production, thereby weakening humoral immune memory. Stress-induced alterations in dendritic cell maturation further compromise antigen presentation. Innate immune regulation is also modified under chronic stress, with macrophages frequently exhibiting a shift toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes. These cellular changes are reinforced by stress-driven cytokine imbalance, characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory mediators alongside compensatory increases in anti-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in immune dysregulation rather than simple immune suppression. These interconnected effects converge on a shared outcome: diminished immune surveillance, impaired pathogen clearance, and increased vulnerability to inflammatory and immune-mediated conditions. This integrative model is schematically summarized in Figure 3.

Key findings

Chronic psychological stress is associated with coordinated alterations across multiple immune cell populations. Reduced proliferation of effector T cells is accompanied by decreased interferon-γ (IFN-γ) cytokine production, alongside an expansion of regulatory T cells. Dendritic cell maturation is impaired, resulting in reduced IL-12 cytokine production and weakened T-cell priming. Chronic stress is associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, as well as increased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. B cells and dendritic cells remain in relatively immature states under chronic stress, leading to impaired antibody production. In addition, macrophages frequently shift toward an M2-polarized, anti-inflammatory phenotype associated with reduced pathogen clearance. These findings are depicted in Figure 3, indicating that chronic psychological stress may induce specific alterations in the immune system, which can have various negative outcomes, such as a greater vulnerability to diseases.

Implications and significance

These results suggest potential biological pathways that help in explaining how individuals under chronic psychological stress may be more susceptible to infections, have poor responses to vaccines, and are at risk for autoimmune flare-ups. The evidence highlights how sustained neuroendocrine activation can modulate immune cell function in ways that may increase the risk of diseases under certain conditions. This review suggests that immune health cannot be studied in isolation from stress biology and that interventions targeting stress pathways may have significant clinical benefit.

Limitations and future recommendations

Despite growing interest in psychoneuroimmunology, the existing literature on chronic stress and immune function has several limitations. Many studies rely heavily on animal models, which allow mechanistic insights but may not fully capture the complexity of human psychological stress and immune regulation. Additionally, definitions of chronic stress vary widely across studies, ranging from self-reported psychological stress and depressive symptoms to physical restraint or social defeat paradigms in animals. This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. As a narrative review and not a quantitative synthesis, the relative contribution of findings could not be assessed statistically. Although efforts were made to include both human and relevant animal studies, selection bias may be present, and not all immune cell types or stress contexts could be comprehensively covered. In addition, the review focuses primarily on well-studied immune populations, such as T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and cytokines, while other components of the immune system that may be affected by chronic stress are not discussed. Future studies should develop human studies that track both stress exposure and cellular immune changes over time, rather than relying heavily on cross-sectional data or animal studies to accurately understand the effects on the immune system. Study designs could include the comparison of the immune system’s characteristics pre- and post-intervention using CBT/exercise/medicinal drugs to test the reversibility of immune dysregulation. Another study could use a longitudinal human study, doing psychological assessments and immune profiling to determine how stress affects the immune system. They should also research how stress management interventions can reverse stress-based immune alterations at the cellular level. A few such interventions are cognitive behavioural therapy, which helps manage chronic stress by replacing unhelpful patterns and behaviours, and exercise, which diverts the mind from harmful thinking and promotes the release of endorphins. Lastly, pharmacological modulation, such as antidepressants and anti-inflammatory drugs will help reduce the effects of chronic stress and restore the balance. In the study done by Dahl et al. (2014), which measured peripheral blood cytokine levels before and after 12-week antidepressant therapy in 50 patients, a significant reduction in the level of cytokines IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, G-CSF, IFN-γ, and IL-1 receptor antagonist was reported20.

Conclusion

Chronic stress has a significant impact on the immune system, particularly affecting T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, cytokines, and macrophages, due to the sustained release of norepinephrine and glucocorticoids. This persistent exposure disturbs the crucial equilibrium required for optimal immune function, thereby transitioning the immune system from a protective state to one associated with increased susceptibility. This review supports a conceptual framework wherein stress modifies immune regulation by hindering effector responses, modifying antigen presentation, and fostering immune dysregulation. These immune alterations explicate the observed correlations between chronic stress and heightened vulnerability to infection, compromised tissue repair, and dysregulated inflammation, as shown through various research models. Further research is needed in this area, but this narrative review highlights stress biology as a key factor in immune regulation. Chronic stress acts as a system-wide influencer of the immune system’s functions, using the neuroendocrine and cellular mechanisms to affect immunoprotection and potentially lead to negative outcomes.

References

- K. Marwaha, R. Cain, K. Asmis, K. Czaplinski, N. Holland, D.C.G. Mayer, J. Chacon. Exploring the complex relationship between psychosocial stress and the gut microbiome: Implications for inflammation and immune modulation. Journal of Applied Physiology. (2025). [↩] [↩]

- S. G. Nunez, S. P. Rabelo, N. Subotic, J. W. Caruso, N. N. Knezevic. Chronic Stress and Autoimmunity: The role of HPA axis and cortisol dysregulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 26, 9994 (2025). [↩] [↩]

- E. Balakin, K. Yurku, M. Ivanov, A. Izotov, V. Nakhod, V. Pustovoyt. Regulation of stress-induced immunosuppression in the context of neuroendocrine, cytokine, and cellular Processes. Biology. 14, 76 (2025). [↩] [↩]

- X. Fan, Y. Wang. β2 Adrenergic receptor on T lymphocytes and its clinical implications. Progress in Natural Science. 19, 17-23 (2009). [↩]

- C. Slota, A. Shi, G. Chen, M. Bevans, N. Weng. Norepinephrine preferentially modulates memory CD8 T cell function inducing inflammatory cytokine production and reducing proliferation in response to activation. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 46 (2015). [↩]

- M. Khedri, A. Samei, M. Fasihi-Ramandi, R. A. Taheri. The immunopathobiology of T cells in stress condition: a review. Cell stress & chaperones. 25, 5 (2020). [↩] [↩]

- A. Alotiby. Immunology of stress: a review article. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13, 21 6394 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- X. Zhang, F. Zink, F. Hezel, J. Vogt, U. Wachter, M. Wepler, M. Loconte, C. Kranz, A. Hellmann, B. Mizaikoff, P. Radermacher, C. Hartmann, C. Metabolic substrate utilization in stress-induced immune cells. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 8 (2020). [↩]

- U. Kuebler, C. Zuccarella-Hackl, A. Arpagus, J. M. Wolf, F. Farahmand, R.V. Känel, U. Ehlert, P. H. Wirtz. Stress-induced modulation of NF-KB activation, inflammation-associated gene expression, and cytokine levels in blood of healthy men. Brain, Behavior and Immunity. 46, 87-95 (2015). [↩]

- S. K. Aghayan, A. H. Shabani, T. Badri, J. H. Nejad, H. E. Ghouvarchinghaleh. Relationship between stress and the immune system-related disorders. International Journal of Medical Reviews. 11, 775-785 (2024). [↩]

- V. Renner, J. Schellong, S. Bornstein, K. Petrowski. Stress-induced pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine concentrations in female PTSD and depressive patients. Transl Psychiatry. 12, 158 (2022). [↩] [↩]

- E. Engler-Chiurazzi. B cells and the stressed brain: emerging evidence of neuroimmune interactions in the context of psychosocial stress and major depression. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 18 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- U. Henning, K. Krieger, S. Loeffler, F. Rivas, G. Orozco, M. G. de Castro, M. Rietschel, M. M. Noethen, A. Klimke. Increased levels of glucocorticoid receptors and enhanced glucocorticoid receptor auto-regulation after hydrocortisone challenge in B-lymphoblastoids from patients with affective disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 30, 4 (2005). [↩]

- P. W. Gold, M. G. Pavlatou, P. J. Carlson, D. A. Luckenbaugh, R. Costello, O. Bonne, G. Csako, W. C. Drevets, A. T. Remaley, D. S. Charney, A. Neumeister, M. A. Kling. Unmedicated, remitted patients with major depression have decreased serum immunoglobulin A. Neuroscience letters, 520, 1–5 (2012). [↩]

- V. L. Vega, A. D. Maio. Heat Shock Proteins: Potent Mediators of Inflammation and Immunity. Heat Shock Proteins 1. Chapter 61-73. [↩]

- J. Yang, W. Wei, S. Zhang, W. Jiang. Chronic stress influences the macrophage M1-M2 polarization balance through β-adrenergic signaling in hepatoma mice. International Immunopharmacology. 138 (2024). [↩]

- S. Momčilović, M. Milošević, D. M. Kočović, D. Marković, D. Zdravković, S. V. Petrinović. Macrophages at the Crossroads of Chronic Stress and Cancer. International Journal of Science. 26, 6838 (2025). [↩]

- Y. Lei, F. Liao, Y. Tian, Y. Wang, F. Xia, J. Wang. Investigating the crosstalk between chronic stress and immune cells: implications for enhanced cancer therapy. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 17 (2023). [↩] [↩]

- L. Piemonti, P.Monti, P. Allavena, M. Sironi, L. Soldini, B. E. Leone, C. Socci, V. Di Carlo. Glucocorticoids affect human dendritic cell differentiation and maturation. Journal of immunology. 162,11 (1999). [↩]

- J. Dahl, H. Ormstad, H. C. Aass, U. F. Malt, L. T. Bendz, L. Sandvik, Brundin, L. Brundin, O. A. Andreassen. The plasma levels of various cytokines are increased during ongoing depression and are reduced to normal levels after recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 45, 77–86 (2014). [↩]