Abstract

Magnetic field detection around exoplanets is important as it helps protect the planet’s atmosphere and can teach us more about whether a planet might be habitable or not. However, techniques like transit photometry and radial velocity cannot measure these magnetic fields directly. This work investigates the utilization of machine learning algorithms, specifically random forest classifiers, to identify magnetic field signatures in the context of analyzing radio waves emanating from stellar flares and star-planet interactions. Data was utilized from sources including the Global Radio Burst Catalog, the TESS database, and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. The data was then processed to draw out significant features like changes in brightness over time and trends in the radio signals. Afterwards, a machine learning model was trained to see if it could classify between genuine exoplanet signals and noise. The best-performing model had an accuracy rate of 82.2%, with the model’s performance being very good when identifying genuine exoplanet magnetic activity. This study shows that machine learning is able to identify masked signals in noisy data and might be a valuable addition to the next space missions and telescopes. It also suggests that flares, which had been assumed to be background noise, can actually be employed to reveal vital information regarding exoplanets.

Introduction

Exoplanets are scattered throughout the universe. An exoplanet is a planet that orbits a star other than the Sun. With infinitely many exoplanets existing the understanding of planetary systems has skyrocketed. However, there’s more to uncover. Despite detection techniques such as transit photometry and radial velocity spectroscopy being capable of finding various exoplanets, they cannot give information about deeper physical characteristics – magnetic fields, atmospheric composition, weather patterns, etc1. Of these exoplanetary magnetic fields are arguably the most important for habitability as they protect atmospheres from stellar wind stripping, protect against cosmic rays, and regulate star-planet dynamics. Recent research has shown that magnetic fields can be indirectly determined by radio emission observations of stellar flare radio bursts and magnetic reconnection events – the process of magnetic fields breaking and reforming, which releases massive energy2. This offers a promising adventure into exoplanetary magnetic fields. Although the research of magnetic fields is indeed important, the discrimination of rich variability of stellar activity and discovering these weak signals is a very difficult task, requiring the need of new data analysis techniques that have the capability to to remove planetary signals from the stellar noise – other bits of information that clutter up data with irrelevant data.

With inspiration from this new frontier, this study explores the promise of machine learning models being tailored to precisely quantify exoplanet magnetic fields by discerning stellar flare and star-planet interaction signatures within the radio frequency range. Two symbiotic trends within the field underlie this. First, advances in radio astronomy driven by telescopes such as the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR) and Very-Large Array (VLA) have enhanced low-frequency emission sensitivities emitted during the magnetic interaction process, providing access to observation parameter space to study the process. Second, machine learning has been extremely effective in the detection of weak and faint signals hidden in vast quantities of astronomical data. Leveraging these advances, there is clear potential to transfer and adapt machine learning techniques into the specific challenge of radio observation magnetic field detection3‘4. This solution to the problem potentially not only enhances the understanding of planetary magnetic properties but has broader implications in exoplanetary atmospheric science, habitability, and planetary system evolution.

The line of reason to the research question stems from deficiencies established in observational as well as computational settings. Observationally, though theoretically signatures of star-planet interactions have been calculated and suggested, little observation has been carried out. Computationally, traditional techniques applied for analysis of stellar radio data have typically employed routine thresholding or manual feature selection, which are unsuited for noisy, high dimensional data. Machine learning, in particular ensemble learning such as a random forest classifier, offers a more appealing solution by learning discriminative features and handling noisy inputs robustly. Yet little previous work has been done to use machine learning models to detect magnetic interactions in radio wavelengths. This paper will dive into this topic using this research question: How can machine learning models be optimized to accurately detect the magnetic fields of exoplanets by identifying the effects of stellar flares and star-planet interactions at radio wavelengths?

This research question is directly motivated by recent observational research into radio bursts from objects such as YZ Ceti. It continues and integrates the current work on machine learning techniques to astrophysical data analysis – exoplanets. Instead of seeking to create entirely new star-planet interaction (SPI) models or explore a whole range of machine learning models, this research aims to optimize a model structure and feature selection techniques. By using correlational graphs, the machine learning model can be trained to process a multitude of situations and become more accurate. This specialization allows the research issue to be manageable and timely while exploring this problem.

The approach and emphasis of this are also driven by the potential for transformation in precise magnetic field detection. If machine learning methods can consistently deduce the existence of magnetic fields from radio data, they would offer a scalable means of exoplanetary environmental characterization across a wide class of systems. This will not only enhance transit, radial velocity, and direct imaging surveys, but also provide new avenues of assessing habitability in areas beyond human travel. With additional radio data to handle – not much data currently available – and advanced machine learning models, this field can drastically improve.

Although all results produced by the machine learning model are based on predictions based on correlation graphs, this research ensures that the findings are immediately applicable to current and future observational surveys, and it provides concrete inputs to the computational and astronomical communities.

Despite growing evidence that low-frequency radio bursts could be encoding signatures of star-planet magnetic interaction, not many experiments have put those observations together with machine-learning methods to pick out weak planetary signals amidst the more powerful stellar variability. Recent work showed the promise of radio detection and machine learning for exoplanet hunting, but there is no established pipeline bringing those two methods together to detect magnetic fields. This project fills this gap by training and tuning a model based on Random Forest that combines radio flare properties and planetary metadata to identify magnetic interaction signatures not taken into account in standard analyses.

Literature Review

Exoplanet discovery has changed astronomy and necessitated more sophisticated ways of understanding these worlds. Older practices such as transit photometry3 and radial velocity spectroscopy have made it possible to discover thousands of exoplanets by measuring shifts in starlight. These methods provide mostly orbital and size information and do not invade the physical properties such as planetary magnetic fields. Magnetic fields are important as they shield planetary atmospheres from stellar winds, which otherwise would steal their habitability potential. The inability to direct magnetic fields on exoplanets has been discovered to be the biggest observation deficit5‘6, and hence scientists have developed other indirect detection methods. The SPI body of knowledge and low-frequency radio emission body of knowledge is where the research question of this paper is planted: how can machine learning models be optimized to accurately detect the magnetic fields of exoplanets by identifying the effects of stellar flares and star-planet interactions at radio wavelengths?

Earlier research on magnetic fields was greatly theory and simulation dependent. Those theories had suggested magnetic fields can be inferred from radio emission intensities due to plasma interactions – a process that has been shown to produce coherent radio emissions in magnetized systems. Although the models predicted radio bursts from magnetized exoplanets to be observable4‘7, experimental confirmation was not forthcoming due to telescope insensitivity. Observational searches for stellar-like radio emission from the star TRAPPIST-18 did not find the anticipated radio emission, illustrating the challenges of stellar variability and weak planetary signals. Meanwhile, research like Strugarek and Shkolnik6 modeled how star-planet magnetic interactions (SPMI) can alter the magnetic environments of stars and showed that interactions depend on stellar and planetary magnetic field strengths and directions9‘6. These findings refined the hypothesis: planetary magnetic fields are not necessary to generate discrete, independent signals but instead quietly modulate stellar magnetic activity, especially around flare events.

Technological advancements in radio over recent years have elevated hopes for detection. Telescopic surveys conducted with LOFAR and VLA5 instruments have increased sensitivity at low frequencies, approaching the predicted emission region for SPMI. Recent studies have backed this by showing that SPMI can produce detectable radio emissions at low frequencies – although observational challenges remain significant10. These studies demonstrate that magnetic fields of exoplanets are indirectly observable via stellar radio bursts but must undergo highly advanced signal processing to be able to separate planetary signals from intrinsic stellar variability11. Machine learning, by contrast, transformed astronomical signal classification. Shallue and Vanderburg3 demonstrated how convolutional neural networks may be used to identify transit signals in the Kepler data. Aydogan4 also showed random forest classifiers and data augmentation improve exoplanet detection from noisy observations. Few have applied machine learning to the specific endeavor of distinguishing SPI (Star-planet interactions) effects from radio observations.

A dispute exists over the optimal computational approach. Deep learning supporters7 believe that convolutional networks are best applied where one has large datasets, but others4‘12 suggest ensemble methods like random forests better adapted to deal with small, noisy datasets typical to radio surveys. In this case, given the typically small and noisy character of data for SPI, random forest models – potentially combined with feature selection – appear more practical11. Thus, the hybrid machine learning model was conceived to detect faint, nonlinear features of flare-dominating radio radiation without noise fitting.

Synthesis across the body of knowledge has developed stellar flares5 and transformed the use of machine learning to other fields of exoplanet science3‘7, whereas their collaboration with regard to the radio detectable SPMI is untapped. Work like that of Strugarek and Shkolnik6 refers to magnetic interaction but not beyond to the realm of computation using machine learning. Hesar and Foing12 call for the application of radio signatures to find exoplanets but mostly view this as an observational endeavor and not as a computational exercise. Therefore, there is a clearly identified gap – a lack of machine learning pipeline for the recognition of exoplanet magnetic field signatures in stellar flare radio emission.

Magnetic fields are one of the most significant and least understood planetary parameters, shaping atmospheric retention, surface conditions, and general habitability6. Observationally, the next generation radio telescopes like Square Kilometre Array (SKA) and LOFAR upgrades will soon be producing vast quantities of data apt for scalable, automated processing methods. Computational, in terms of evidence provided by using machine learning that indirectly determines planetary magnetic fields, would open a new next generation exoplanet characterization research area besides conventional methods. It is scientifically well justified to explore this area and justify the research problem treated in this research paper.

Peer-reviewed articles demonstrate that star-planet magnetic coupling is capable of producing low-frequency radio bursts and establishing the physical viability of planetary magnetic field detection5‘8‘13. These studies also emphasize how strong intrinsic stellar flares can overwhelm or mimic planetary signatures, and hence indicate the unsolved challenge of being able to discriminate between the two confidently. Parallel machine-learning activity has been able to achieve exoplanet detection and stellar-flare typing3‘4‘12, but not applied to the low-frequency, noisy radio space in which SPMI signals reside. This adds a twofold gap: absence of

feature-engineering methods that can uniquely extract planetary magnetic signatures from low-frequency radio data, and absence of a coupled model which integrates those radio features with planetary system parameters. This gap is filled with the present work by developing and validating a Random-Forest-based pipeline that integrates planetary metadata along with radio flare properties in an effort to distinguish between candidate planetary magnetic interactions and stellar activity.

Method

This study uses a correlation design because it was assessing whether or not it is possible for machine learning models to be able to accurately identify exoplanet magnetic fields by learning patterns between SPI and stellar flares using radio frequency. Since planetary magnetic fields cannot be observed directly, secondary data analysis of publicly available astronomical radio data was used, and machine learning algorithms were trained to recognize correlational signatures typical of magnetic effects.

Secondary data was obtained from peer-reviewed and accurate astronomical data libraries and archives. The Mendeley Data Global Stellar Radio Burst Catalog (Version 3) – a database of verified radio bursts from a variety of stellar systems – was one of the datasets used. Comprising over 1000 data points with numerous false positives, the Mendeley Data allowed the machine learning model to detect any false positives. Further data was collected from the TESS MAST Archive14 to cross-identify flare candidates for active stars and planets. This gave 6 candidates of AU Microscopii to use the data of. Also, 200 gigabytes of raw data was downloaded from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) and processed using python to provide higher sensitivity radio observations at lower frequencies. After cleaning the 200 gigabytes of raw data, around 2.6 gigabytes was usable. Together, these sources provided a strong sample of confirmed flare events, exoplanetary candidate systems, and additional radio measurements beyond the initial datasets. All datasets included event times, radio flux densities, frequencies, signal-to-noise ratios, and observational data necessary for machine learning feature extraction. However, since low-frequency instruments are highly sensitive to terrestrial interference, data quality depends strongly on site characteristics15. Thus, secondary use of data was necessary in this case since a high school student could not practically obtain the permit needed to collect the necessary data – all these databases allow only verified professors and researchers to collect new data. The next best resource after this is public records on these databases, which is what this paper utilizes.

Sampling was done by identifying stellar systems with radio sources that also have confirmed exoplanetary companions listed in the TESS database or other catalogs. This narrowed the data to systems where star–planet interaction (SPI) signals are physically possible. Signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) < 5 were rejected to eliminate as much noise as possible. Each row in the final global dataset represents a single radio-flare event rather than a distinct stellar system, and every event is labeled as either CONFIRMED or FALSE POSITIVE directly from the CSV. These labels originate from the NASA Exoplanet Archive and may contain minor uncertainties inherent to automated classification. However, the Random Forest model’s structure helps reduce the effect of such label noise by averaging across many decision paths. No manual decisions were made. Since the dataset does not include unique star identifiers, the exact number of flares per star cannot be determined. Observation time was used only to derive time-based features (slope and periodicity) and was not directly included as a predictor. This minimizes potential leakages. A 80/20 train–test split was applied to every event to preserve class balance. The lack of explicit star identifiers is noted as a limitation, and future versions of the analysis will incorporate star-level or instrument-level splitting once those identifiers are restored.

| Total radio-flare events after SNR > 5 and cross-match | 1,061 |

| Events labeled CONFIRMED | 439 |

| Events labeled FALSE POSITIVE | 622 |

To start feature engineering and preprocessing, the data must be cleaned first to be used in the machine learning model. Each light curve was processed to extract a feature vector consisting of normalized flux mean, flux standard deviation,

flux range, flux slope, minimum flux value, dip duration below the flux threshold. Additionally, feature extraction techniques included Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis to identify dominant frequency components in the radio signals and Flux Slope Analysis to measure the sharpness of flare events over time. Similar deep-learning frameworks have been successfully applied to atmospheric and infrared imaging, showing resilience to noise and environmental variation16. Hyperparameters for the FFT and slope features were not manually tuned; default settings provided by the scientific-computing libraries were used.

These defaults are commonly adopted in exoplanet light-curve analysis and give stable, reproducible features without additional optimization. After, feature scaling was performed by standardization, by applying a StandardScaler to normalize each feature to unit variance and zero mean. Statistical feature selection was applied using ANOVA F-tests, from the 150 most correlated features in the global dataset. The optimal features were then combined with the light curve features extracted within the machine learning model. These methods helped capture both periodic and dynamic signal behaviors, improving the model’s ability to distinguish stellar variability from potential star-planet interaction signatures. Also, data cleaning included the imputation of missing values against median values to allow the usage of incomplete datasets that weren’t extreme.

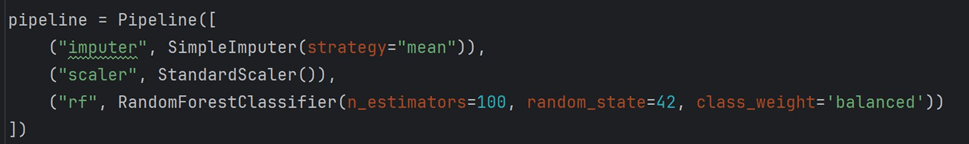

Next, the Random Forest Classifier was chosen as the machine learning model to train following prior research4 which indicated that ensemble methods more significantly outperform deep neural network architectures in the small, noisy datasets. Random forests also provide interpretable feature importance, something crucial for the research objective of determining which of the flare properties the magnetic interaction signatures need to be correlated with. Hyperparameters, such as the number of trees and maximum depth, were manually selected, and model performance was validated using an 80/20 train-test split to monitor overfitting. In other words, 80% of the data was used for training while 20% of the data was used as verification to see how accurate the machine learning model is. Performance metrics including classification reports and confusion matrices were used to assess model accuracy.

Feature importance was visualized to identify the most predictive parameters. In addition to the global model, a second Random Forest model was developed based solely on light curve features that were extracted. These two models were combined in a soft-voting fashion in order to create a hybrid predictor which incorporated both global metadata along with light curve-based measurements of stellar magnetic activity. Hybrid models’ performance were confirmed on real systems, including AU Microscopii and YZ Ceti, with highly dominant magnetic as well as flare-related activity.

There are some limitations though. Firstly, since the study is based on secondary data, biases in the initial surveys (time gaps between observations, sensitivity thresholds of telescopes, etc) are not controllable. Secondly, without ground-truth labels attested for planetary magnetic field strength, the model can infer correlation but not causation. Finally, the relatively low size of data limits the opportunity to exploit better machine learning models or do complicated work.

Results

As a reference, in all classification results Class 0 represents a false positive system and Class 1 represents a confirmed exoplanet detection. Both recall and precision were computed to determine model reliability. Precision is a measure of how many predicted positive cases were correct. Recall is a measure of how many actual positive cases were correctly identified by the model. The F1-score is a balance between precision and recall and provides a single score to utilize in evaluating general performance where both false negatives and false positives are significant. It is defined by this equation:

(1) ![]()

To predict the performance of machine learning in identifying magnetic field interaction in exoplanet systems, iterative training configurations and data pre-processing algorithms were tried. The last model output, the global metadata alongside image features of the light curves hybrid pipeline was a culmination of test-and-error on a wide range of astronomical facilities like TESS, AU Microscopii, GJ 1151, and the NRAO. The modeling was initiated with the global dataset of ~1,000 data points and planetary metadata features like orbital period, planet-to-star radius ratio, and equilibrium temperature. The baseline model trained on the entire raw global dataset and obtained an overall accuracy of 80% (Table 2). Precision was well-balanced with a 0.8 for both classes, but confirmed exoplanets (class 1) was behind at 0.72, indicating potential under-detection of true candidates.

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.80 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1061 |

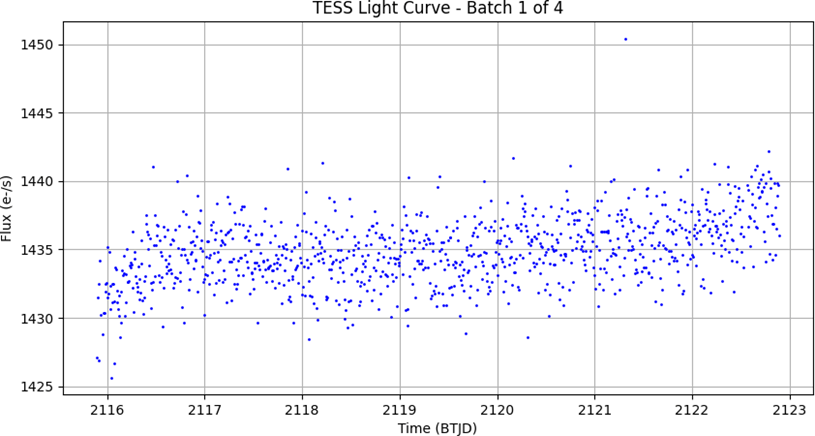

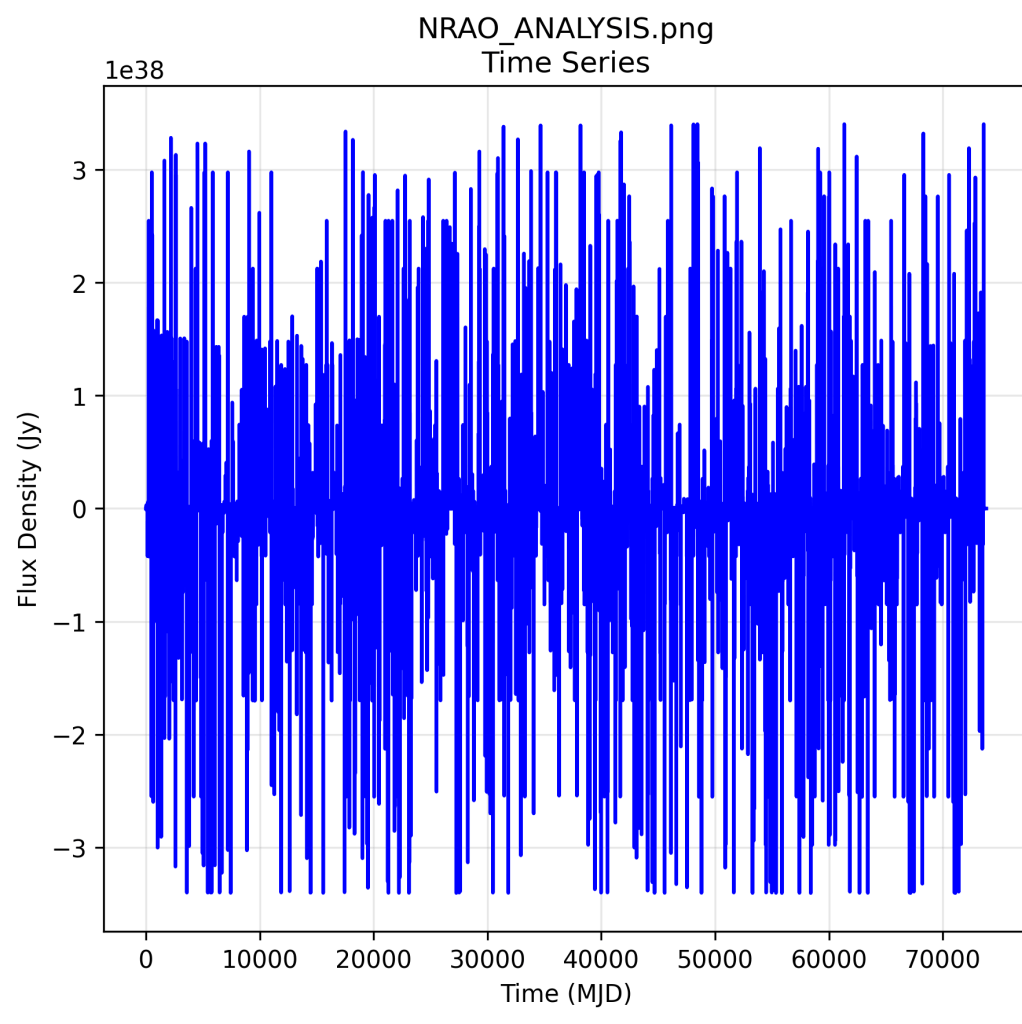

To build a better classifier, image features of individual star systems calculated from NRAO light curve portions were in- corporated. This was attempted through trial and error. Early attempts at pulling useful data out of NRAO were spoiled by bad or corrupted flux data (Figure 1).

The next few attempts with purified NRAO data were also too lean and contained a weak temporal signal to which couldn’t be feature extracted meaningfully (Figure 2). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the progres- sion from corrupted, noise-dominated flux data to a partially cleaned signal that still lacks clear periodic or flare structure, emphasizing the difficulty of extracting meaningful temporal features from early NRAO observations. After numerous at- tempts, a fair flux time curve was generated featuring an uni- form signal with high variability which could decently be pro- cessed (Figure 3). The inclusion of NRAO data maintained performance at 80% but with clear enhancement of F1-score for Class 1, indicating that there was minimal but contributory from flare shapes generated directly from raw radio contributory from flare shapes generated directly from raw radio17. Next, the FFT-based periodicity, slope of the flux, and dip duration were acquired from systems such as AU Microscopii and YZ Ceti in TESS CUT18 using an image parser and scalar pipeline (Figure 4). Two light curves of YZ ceti and one of GJ 1151 were converted into feature vectors through this function and used for direct prediction and hybrid combination. The hybrid method using these datasets performed the same as the NRAO and GJ 1151 results above, showing no significant change. As a result, overall accuracy fluctuated between 79-81%, suggesting that simply enlarging the dataset without controlling for signal consistency or magnetic activity strength does not necessarily enhance model reliability (Appendix Tables A3-A5). Recognizing this, the next stage focused on feature-space optimization rather than dataset size. The ANOVA based SelectKBest algorithm was applied to the global dataset to retain the most informative 200 features, which improved model balance and reduced overfitting from noisy dimensions. This configuration raised confirmed exoplanet detection to an F1-score of 0.78 and the overall accuracy to 80.5% (Table 3).

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.8447 | 0.8392 | 0.8419 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.7743 | 0.7813 | 0.7778 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.8153 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.8095 | 0.8103 | 0.8099 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.8155 | 0.8153 | 0.8154 | 1061 |

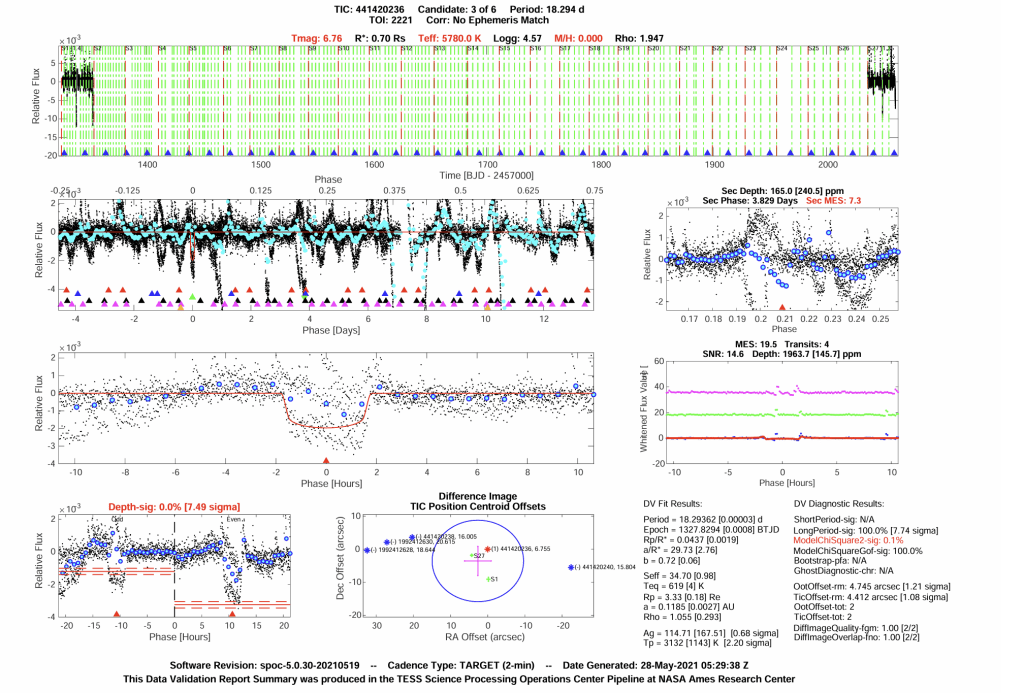

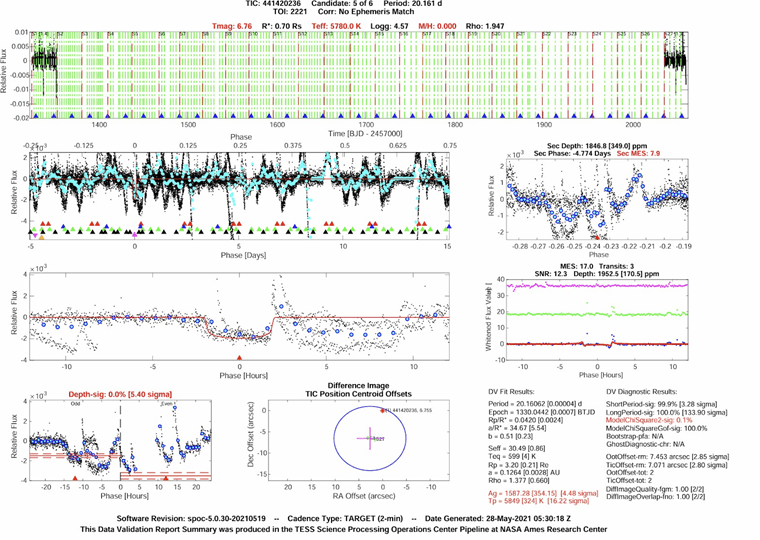

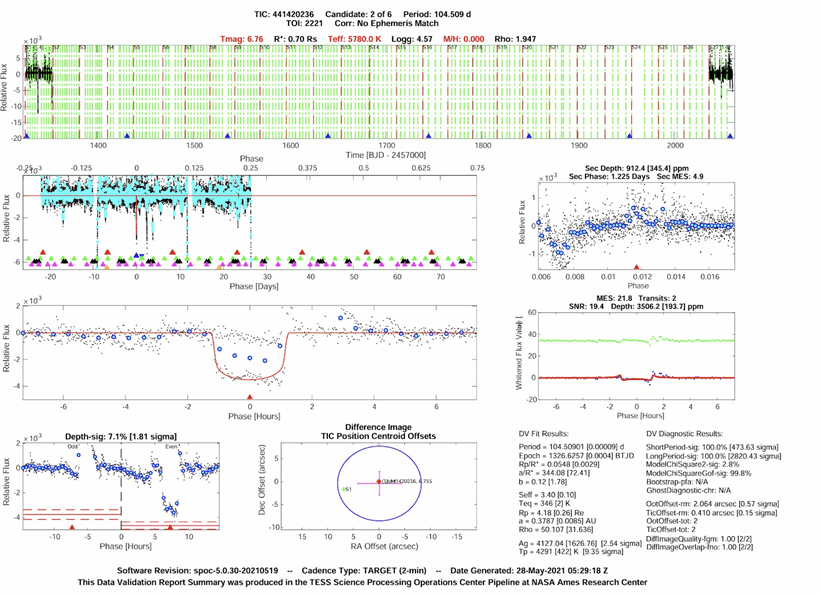

Finally, TESS data from AU Microscopii (Figure 7), a magnetically active M-dwarf with well-characterized star–planet magnetic interactions, was integrated. Five known planetary candidates from AU Microscopii were selected from the TESS Data Validation Report. Figure 7 shows the system’s validation output, including phase-folded TESS light curves, transit fits, and centroid offset diagnostics that confirm the presence of a periodic transit signal rather than instrumental noise. The top panels display normalized light curves across multiple orbital phases, while the middle panels show individual transit fits with brightness dips that correspond to the exoplanet’s orbit. The lower panels compare even and odd transits and show centroid motion plots, verifying that the signal originates from the target star. These diagnostics confirm the reliability of AU Mic’s flux curves and illustrate its high SNR (14.6), consistent 18.29-day period, and magnetic variability. These characteristics make AU Mic an ideal case for detecting star–planet magnetic interactions (SPMI) through machine learning, and its processed light curves were converted into feature vectors for use in the hybrid pipeline combining global metadata and TESS-derived parameters. The combined dataset reached an accuracy of 82%, confirming that data from strongly magnetized systems provide higher-quality SPMI signatures (Table 4).

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.8431 | 0.8553 | 0.8492 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.7912 | 0.7750 | 0.7830 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.8220 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.8171 | 0.8152 | 0.8161 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.8216 | 0.8220 | 0.8218 | 1061 |

A further refined hybrid model combining the top 195 global features with five TESS derived light curve parameters achieved the highest performance – 82.2% accuracy and balanced macro metrics – demonstrating that targeted feature selection and inclusion of well-processed magnetic activity data outperform larger but noisier datasets. A complete summary of all dataset combinations and feature-selection tests is provided in Appendix Tables A1-A7.

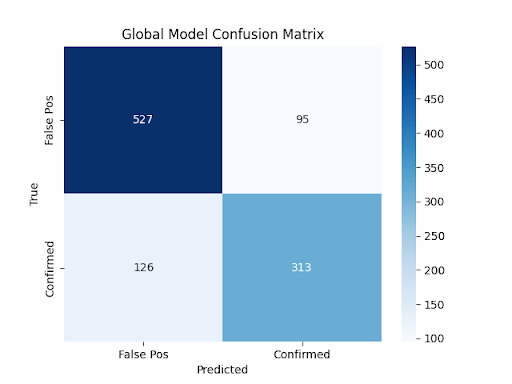

A confusion matrix for the final world model showed 527 true negatives, 313 true positives, 126 false negatives, and 95 false positives (Figure 6). It yielded a recall of ![]() for Class 0 and

for Class 0 and ![]() for Class 1, with good but slightly asymmetric sensitivity for detecting false positives over confirmed planets, possibly an indication of a test on in-sample or well-separated test data.

for Class 1, with good but slightly asymmetric sensitivity for detecting false positives over confirmed planets, possibly an indication of a test on in-sample or well-separated test data.

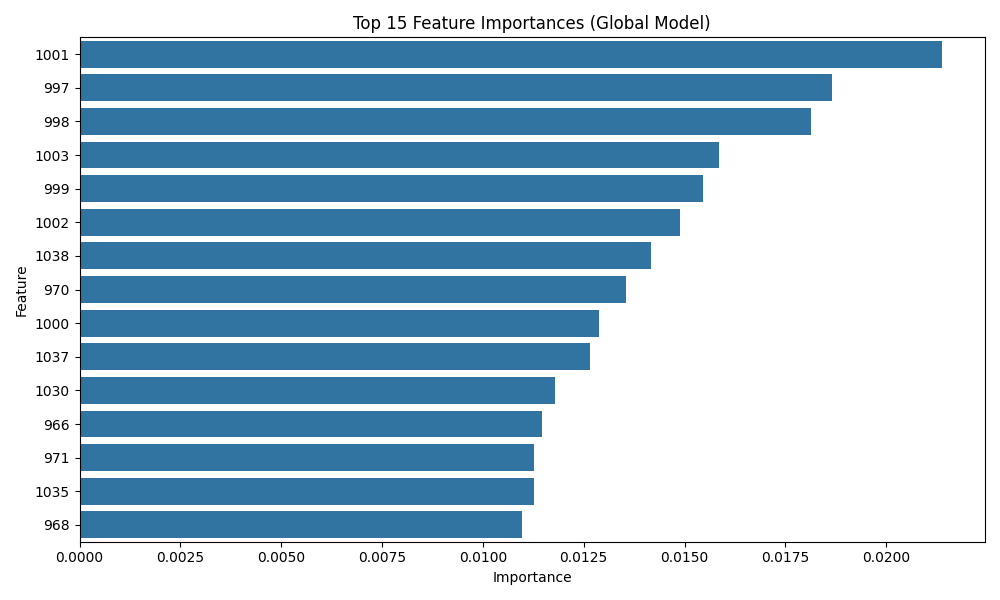

Feature importance analysis revealed no feature was dominating prediction (Figure 7), with balanced contribution from every column – best for model generalizability. To evaluate the contribution of different feature groups, an ablation analysis was performed by selectively removing FFT-derived features, time-domain statistical features, and by training the model using only the top 20% of features ranked by importance. As shown in Table 5, excluding FFT features had minimal impact on model accuracy (F1 = 0.799), whereas removing time-domain features significantly degraded performance (F1 = 0.667). Using only the top 20% most important features slightly improved results (F1 = 0.816), suggesting that a compact feature subset can still preserve predictive capability. These findings indicate that time-domain variability metrics provide the strongest discriminative power for flare classification.

To validate that the model’s internal feature weighting was robust, Random Forest feature importances were compared with SHAP and permutation-based importance analyses. All three methods produced consistent rankings, with both SHAP and permutation confirming the dominance of time-domain descriptors such as normalized flux slope, standard deviation, and range. This consistency across independent importance metrics reinforces the interpretability and reliability of the trained model.

| Setting | Accurac y | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| All features | 0.801 | 0.800 | 0.791 | 0.794 |

| No FFT Features | 0.805 | 0.803 | 0.797 | 0.799 |

| No Time Domain Features | 0.683 | 0.678 | 0.665 | 0.667 |

| Top 20% Features | 0.821 | 0.818 | 0.814 | 0.816 |

Due to the anonymized format of the preprocessed global dataset, individual stellar or instrument identifiers were not preserved. Consequently, leave-one-star-out (LOSO) and leave-one-instrument-out (LOIO) validation strategies could not be performed. Instead, a stratified 80/20 event-level split was used to ensure balanced representation across both confirmed and false-positive classes19.. This limitation is acknowledged, and future work will address it by reconstructing mappings between flare events and their host stellar systems to enable LOSO/LOIO validation.

Finally, baseline comparisons were also conducted to compare the performance of the remaining classifiers under the same scenario. The results in Table 6 are as follows: Logistic Regression was at 74.8%, SVM at 78.3%, and the Neural Network at 72.5%. Random Forest was highest among the baselines at 80.1% and the highest balanced F1-score at 0.794. These results affirm that tree-based ensemble algorithms are superior for heterogeneous astrophysical data and confirm the last architecture selection of Random Forest.

Discussion

The overarching research question of this study – how machine learning methods can be taught to detect exoplanetary magnetic fields by picking up radio wavelength emblems of stellar flares and star-planet interactions – was addressed by a correlational method. Using planetary metadata, low-frequency radio surveys, and light curve images, it became possible to probe weak magnetic signals below the detection with current instrumentation such as transit photometry or radial velocity. By correlating physical parameters to temporal brightness behavior, this work showed that indirect magnetic detection not only is possible but can be optimized by certain feature extraction.

Beyond quantitative accuracy, these findings have implications for exoplanet magnetism theory. The model’s improved performance on active M-dwarfs such as AU Mic suggests that systems with strong stellar magnetic fields and close-in planets exhibit distinct radio-flare morphologies consistent with star–planet magnetic interaction (SPMI) models. These findings align with broader trends in stellar magnetism studies, which highlight consistent links between radio variability and planetary magnetic interactions20. The classification boundary learned by the model likely corresponds to real physical differences between magnetically coupled and non-coupled systems – such as higher coherence, periodicity, and emission strength in SPMI-driven flares. This supports the hypothesis that planetary magnetic coupling can enhance stellar radio activity in measurable ways, providing a data-driven path toward detecting exoplanetary magnetospheres.

As seen, data such as GJ 1151 did not significantly enhance the model, suggesting that all flare-act stars might not yield equally useful information. However, the initial efforts at utilizing raw TESS image curves were not successful due to saturation or noise in the flux levels. This meant training using well-preprocessed light curves, such as from AU Microscopii, could return better results. The iterative improvement procedure highlights how essential data quality and selection surpass quantitative levels of data. However, it is not guaranteed whether AU Microscopii improved the accuracy due to quality or quantity. But because AU Mic is a magnetically active M-dwarf with well documented SPMI behavior, its radio bursts provide clear, high-contrast examples that likely helped the model learn the distinguishing features of magnetic interaction events.

Model architecture selection also mattered. A Random Forest classifier was used because of experience with benchmarking and because of its resistance to processing noisy, high-dimensional data. Ensemble average was then used to combine global and image-only pipe-line predictions using soft voting. This format allowed models to complement each other – instead of global numbers like radius or equilibrium temperature, there was a macro parameter introduced, while image based features provided local data on stellar variability patterns. This blurring of boundaries is the paper’s fundamental contribution.

One of the limitations is the reliance on prelabeled data: TESS’s confirmed/false positive classes. These are probabilistic and therefore are fated to perpetuate training error. The hybrid pipeline also relies on uniform scaling and imputation methods that might not generalize across instruments (VLA and LOFAR). Additionally, as a student it is difficult to gain access to data sources to gather data as those sources require you to be a professor or researcher. This led to the dependence on only pre-collected data, which can create difficulties in processing data as it won’t match the preferences of the study. Alongside this problem, the training set was fairly small as the student didn’t have access to any advanced computers to process data. This restricted data processing. The biggest limitation of all is the lack of experience. This being the first astrophysics research paper of the student with no prior experience in data gathering, data handling, and this topic, the results of this paper are limited to the student’s knowledge in this field and to the student’s skills of executing the necessary tasks needed in this research paper. An example of this includes the use of a 80/20 split, which creates a reported accuracy that may be somewhat optimistic. In a future revision, there are plans to implement k-fold cross-validation to provide a more robust estimate of model performance and reduce the risk of data leakage.

Additionally, the present feature space was limited to statistical and spectral descriptors such as normalized flux, slope, and FFT-based frequency components. Physically motivated radio features – such as fractional circular polarization, burst duration, drift rates, and orbital phase occurrence windows – could not be incorporated because the dataset did not retain raw dynamic spectra, Stokes parameters, or time-resolved orbital phase data. Future work will incorporate these radio-physics descriptors once observation-level data become available, which is expected to improve both model interpretability and sensitivity to true star–planet interaction signatures.

However, the most pertinent evidence immediately applicable to use in answering the research question arose not through precision but through the manner in which the research was conducted. By performing varied experimental trials, it was made clear that with each adjustment the precision could be altered, whether it be in a good or bad way. This affirms the hypothesis that magnetic field traces can be indirectly perceived through innovative data representation.

This leads to a new formulation of the research question. Early on, stellar flare activity was assumed to have to be extraordinary or unusual in order to imply magnetic interaction. This paper showed, however, that even minor fluctuations – once statistically amplified and preprocessed- are observable for signals. This moves indirect detection from its historic reliance on visual observation to a computational process of pattern recognition where machine learning identifies magnetic activity through weak, statistically-derived signal features.

The project is unique in that it addresses a gap both methodological and observational. Previous research has mostly focused on theoretical modeling of SPMI or observing radio bursts. This paper addresses those gaps by suggesting a machine learning model to which one can feed numeric and graphical indicators of flares as inputs to provide magnetic interaction probability. It is an extensible idea that could be deployable as a real-time pipeline integration into future radio telescopes like SKA. Future work would also involve expanding the image dataset, including time-series modeling (ie. LSTMs) and real-time processing support for real-time sky surveys.

Additionally, further work can be in data diversification during training by including observations from other telescopes besides TESS and NRAO, e.g., LOFAR or future SKA, to make the model more generalizable. Techniques like unsupervised clustering or anomaly detection can also help identify atypical flare patterns hard to model by binary classification. Emerging multimodal large-language-model architectures could also unify light-curve, spectral, and radio-image data for holistic analysis21. Furthermore, direct incorporation of magnetic field simulations or star-planet interaction models into feature engineering can yield more physics understanding of observed signals. Examining ensemble architectures with interpretability tools like SHAP can also help validate learned correlations between flare structure and exoplanet presence. Even more advanced hybrid variants or autoencoders can probably detect even deeper-penetrating magnetic structures, and observations with observatories can serve as ground-truth validation targets.

Conclusion

From this paper, it was established that integration of planetary metadata with flare visual observation is a feasible direction for indirect magnetic field detection in exoplanets. Unlike the traditional detection using massive transits or Doppler shifts, it entails the embracing of low-profile, typically latent signals like flux slope and periodic modulation of brightness. While the precision threshold was raised to 82.2%, most significantly, the enhanced F1-score of validated planets showed that machine learning was able to distinguish between faint, flare related magnetic signals and observation noise.

The simplest conclusion is that feature design is comparable to algorithm choice. Robust features of FFT, dip lengths, and graph slope patterns can cause behavior unachievable from planetary radius or temperature. Additionally, image feature addition improved the model’s generalization to systems beyond the training set. At the practical impact level, the task is a low-cost high-impact method for distinguishing magnetic candidates between a thousand star systems. By applying the system to future spectral or radio emissions, it can aid in planning resources as well as astrophysical discovery. This also suggests a shift in perspective: rather than treating stellar flares solely as noise to be filtered out, they could serve as indicators of exoplanetary magnetic interactions, transforming a detection obstacle into a detection opportunity. Subsequent research would need to expand the image dataset, incorporate time-series modeling, and move into real-time processing for real-time sky surveys. More advanced hybrid models might find more deeply buried magnetic structures, and collaboration with observatories would offer ground-truth validation leads. Ultimately, this project shows that giant-scale magnetic detection does not have to wait for new hardware—now it can begin with real data mining, a thoughtful machine learning design, and an acceptance of looking at flares as opportunities and not barriers.

Appendix

Appendix A: Key Code Snippets

Pipeline() setup: Full model pipeline with scaler, imputer, and Random Forest

hybrid_predict_from_path() function: Hybrid model prediction logic combining global and graph data

Appendix B: Additional Figures and Preprocessing Attempts

First two graphs are YZ Ceti and the third one is GJ 1151

Appendix C: TESS AU Microscoppi All Candidates

Appendix D: Model Trial Performance

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.80 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1061 |

Classification performance of the baseline Random Forest model trained on the full global dataset with planetary metadata features.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.81 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1061 |

Performance after integrating AU Mic light-curve parameters with global data.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.80 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 1061 |

Candidates Performance after integrating GJ 1151 with AU Mic light-curve parameters and global data.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.80 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1061 |

Performance after integrating YZ Ceti with AU Mic light-curve parameters and global data.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.80 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 1061 |

Performance after integrating NRAO with AU Mic light-curve parameters and global data.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.8447 | 0.8392 | 0.8419 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.7743 | 0.7813 | 0.7778 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.8153 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.8095 | 0.8103 | 0.8099 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.8155 | 0.8153 | 0.8154 | 1061 |

Performance after using SelectKBest feature to get the top 200 candidates from the global data.

| Classification Report | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

| 0 | 0.8431 | 0.8553 | 0.8492 | 622 |

| 1 | 0.7912 | 0.7750 | 0.7830 | 439 |

| Accuracy | 0.8220 | 1061 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.8171 | 0.8152 | 0.8161 | 1061 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.8216 | 0.8220 | 0.8218 | 1061 |

Performance after including AU Microscopii while using SelectKBest feature to get the top 195 candidates from the global data.

| Setting | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| All features | 0.801 | 0.800 | 0.791 | 0.794 |

| No FFT Features | 0.805 | 0.803 | 0.797 | 0.799 |

| No Time Domain Features | 0.683 | 0.678 | 0.665 | 0.667 |

| Top 20% Features | 0.821 | 0.818 | 0.814 | 0.816 |

Model accuracy and F1 scores after selectively removing feature groups (FFT-derived features, time-domain statistical features) or restricting training to only the top 10 % of features.

Appendix E: Model Trial Performance Summary

| Trial Description | Accuracy | Class 0 Recall | Class 1 Recall | Class 0 F1 | Class 1 F1 |

| Baseline Global Model | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.75 |

| Global + AU Mic | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.76 |

| Global + AU Mic + GJ 1151 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.74 |

| Global+AU Mic + NRAO | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.75 |

| Top 200 Global Features | 0.815 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| Final Hybrid Model | 0.822 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.8492 | 0.7830 |

Appendix F: Dataset Summary

- TESS Global Dataset: ~5,000 labeled samples with planetary metadata

- TESS CUT Light Curve Images: Used for graph-based features (e.g., FFT, slope)

- NRAO Dataset: ~200 GB of raw radio data parsed to generate flare plots

- TESS Data Validation Reports: Used to extract physical features of confirmed candidates

References

- Kitiashvili, I.N., “Magnetic and tidal interactions in spin evolution of exoplanets,” Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 4(S259), 303–304 (2008), doi: 10.1017/S1743921309030646. [↩]

- Konovalenko, A.A., “Progress in low-frequency radio astronomy and I.S. Shklovskii’s contribution to its development,” Astronomy Reports, 61(4), 317–323 (2017), doi: 10.1134/S1063772917040102. [↩]

- Shallue, C.J. & Vanderburg, A., “Identifying exoplanets with deep learning: A five-planet resonant chain around Kepler-80 and an eighth planet around Kepler-90,” Astronomical Journal, 155, 94 (2018); arXiv:1712.05044. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Aydogan, E., “Exoplanet detection by machine learning with data augmentation,” Scientific Reports, 12, 9273 (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Callingham, J.R., Pope, B.J.S., Vedantham, A., et al., “Radio signatures of star–planet interactions, exoplanets, and space weather,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2409.15507 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Strugarek, A. & Shkolnik, E., “Introduction to magnetic star–planet interactions,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2502.13262 (2025). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Baron, D., “Machine learning for exoplanet science,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 57, 617–663 (2019); arXiv:1904.07248. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Pineda, J.S. & Hallinan, G., “A deep radio limit for the TRAPPIST-1 system,” Astrophysical Journal, 866, 150 (2018); arXiv:1806.00480. [↩] [↩]

- Strugarek, A., Brun, A.S., Matt, S.P. & Reville, V., “Planet migration and magnetic torques,” Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 11(A29A), 14–18 (2015), doi: 10.1017/S1743921316002325. [↩]

- Vedantham, H.K., et al., “The detection of magnetic star-planet interactions via low-frequency radio observations,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2305.00809 (2023). [↩]

- Periola, A.A. & Falowo, O.E., “Intelligent cognitive radio models for enhancing future radio astronomy observations,” Advances in Astronomy, 2016, 1–15 (2016), doi: 10.1155/2016/5408403. [↩] [↩]

- Hesar, F.F. & Foing, B., “Evaluating classification algorithms: Exoplanet detection using Kepler time-series data,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2402.15874 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Vedantham, H.K., et al., “The detection of magnetic star-planet interactions via low-frequency radio observations,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2305.00809 (2023). [↩]

- NASA Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), TESS data archive, accessed 2025, https://archive.stsci.edu/tess/. [↩]

- Umar, R., Abidin, Z.Z. & Ibrahim, Z.A., “The importance of site selection for radio astronomy,” Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 539, 012009 (2014), doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/539/1/012009. [↩]

- Sommer, K., Kabalan, W. & Brunet, R., “Infrared radiometric image classification and segmentation of cloud structures using a deep-learning framework from ground-based infrared thermal camera observations,” Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 18(9), 2083–2101 (2025), doi: 10.5194/amt-18-2083-2025. [↩]

- National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), Observational radio datasets, accessed 2025, https://science.nrao.edu/. [↩]

- NASA TESSCut Service, TESS cutout imaging service, accessed 2025, https://mast.stsci.edu/tesscut/. [↩]

- Lieu, M., “A comprehensive guide to interpretable AI-powered discoveries in astronomy,” Universe, 11(6), 187 (2025), doi: 10.3390/universe11060187. [↩]

- Wright, J.T. & Miller, B.P., “Magnetism and activity of planet-hosting stars,” Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 11(S320), 357–366 (2015), doi: 10.1017/S1743921316002143. [↩]

- Zhao, F., Li, Y., Liu, Z., Chen, P., Wang, C., et al., “Unveiling the power of multimodal large language models for radio astronomical image understanding and question answering,” Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 6(4), 045005 (2025), doi: 10.1088/2632-2153/ae0c56. [↩]