Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of 3D printed teaching aids (teaching aids) on students’ Calculus learning outcomes in a controlled experiment. The fifty-seven (57) participants were high school sophomores and juniors taking the Advanced Placement Calculus AB (“Calculus AB”) course by the College Board. The experimental group had access to 3D printed teaching aids, while the control group did not. Both groups watched the same video and did the same survey to test the lessons effectiveness. The experiment found that exposure to 3D printed teaching aids did not significantly improve students’ normalized academic performance nor their opinions of the efficacy of the 3D printed teaching aids. The only relevant statistically significant result found was that students in the experimental group who generally rated the lesson as “not helpful” still correlated with rating the lesson as significantly more helpful than students in the control group who rated the lesson as “not helpful.” Going forward, more research with varied and larger groups should be done to discover any more significant correlations between the use of 3D printed teaching aids and student success. The accessibility of 3D printed teaching aids could facilitate these experiments.

Introduction

There is a gap in the literature linking 3D printing and mathematics learning, especially for Calculus AB. Discovering any correlation between the use of 3D printed teaching aids and mathematics learning could uncover a new tool for educators to improve student outcomes. Apart from learning benefits, the use of 3D printed teaching aids may be relatively more sustainable, affordable, inclusive, durable, and convenient compared to other teaching materials. Taken together, studying the effects of 3D printed teaching aids on mathematics education is a worthwhile endeavor.

Importance of Learning Calculus AB

Assisting students in learning Calculus AB comes with valuable STEM career, gender equality, and college application benefits. Calculus AB topics include Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections, which involve understanding 3D objects in relation to 2D sketches1; learning Calculus AB is a requirement for many post-secondary STEM degrees2. Facilitating STEM learning is essential to meet workforce demands3. For gender parity, women are 50% more likely to leave STEM studies after taking Calculus I, which is similar to Calculus AB, than men4‘5. One study conducted a “large-scale and in-depth national survey4, finding that not understanding course content enough explained some of this disparity: “Among STEM-intending students, 35% of women reported this as a reason while only 14% of men acknowledged it (p = 0.026). Among STEM-interested students, 32% of women reported this as a reason compared to only 20% of men (p = 0.051)”4. Assisting women in better understanding course content may ameliorate some of the disparity.

Learning Calculus AB may be useful for college applications, as 93% of high school counselors recommend taking Calculus AB in high school6. Of course, Calculus AB is not a silver bullet for college admissions; only 34% of admission officers say that not taking Calculus narrows admission options7.

Other Benefits of 3D Printing

3D printing is relatively more sustainable and affordable in its material and energy usage than alternatives such as petroleum-based plastics or metal. 3D printing uses polylactic acid (“PLA”), which comes from the fermentation of corn8. Producing PLA uses less energy than producing petroleum-based plastics9. For teachers and classroom supply procurers who are considerate of sustainability, PLA is promising. PLA is affordable, only costing 0.25 USD per pound to be produced10. On average, 3D printing costs 86% less than purchasing similar learning aids commercially11. Compared to CNC milling aluminum or steel, 3D printing is several times more affordable in making aerodynamic models; metal models may cost “tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars”12.

The use of 3D printed teaching aids can be inclusive of students, as discussed in the section; they are also durable enough to be used with schoolchildren without fearing of them breaking13.

3D printing is convenient. Extremely large 3D printed models may take a day or two to manufacture, which is weeks or months faster than machining metal12. A model acquired through 3D printing may take mere hours while acquired through online retailers may take days14.

Experiment Goal

While 3D printing has been used in a wide variety of fields to teach students15, there seems to be a lack of research in its ability to specifically assist students in learning Calculus AB. The current research seems to focus on basic geometry or advanced engineering topics instead.

This senior project explored the efficacy of teaching aids in Calculus AB, including creating teaching aids of Disks, Washers, and Volume CrossSections, allowing students to physically hold representations of the otherwise abstract concepts they seek to understand.

Literature Review

A growing and relatively new technology16, 3D printing is now used broadly in education for teaching about 3D printing, teaching design skills, teaching creativity skills, creating assistive technologies, and making teaching aids17. There is room for consideration of the role of teaching aids in serving students with disabilities and the role teachers fill when introducing 3D printing technology to the classroom. Literature indicates that a promising use for 3D printing is in mathematics education.

Systemic Review Methods: Literature was found by searching with key words such as “3D printing,” “teaching aids,” and “calculus.” Studies relating to 3D printing in education were included, while studies irrelevant to 3D printing in education were excluded. Notes were taken by hand, and studies were read by human eyes, without the use of large language models. The exclusion criteria for studies of poor quality included an absence of listed authors, few or no citations, and no connection to any educational or other reputable institution.

About 3D Printing

To 3D print, the user first designs a 3D model using an accessible ComputerAided Design (“CAD”) software program18. The user then sends the 3D model to a 3D printer19‘20. 3D printers are available in primary schools, secondary schools, universities, and libraries; libraries in particular have increased efforts to provide access to 3D printing to patrons who come from the general public21.

3D Printing: Design and Creativity Skills

When using 3D printing in the classroom, students build their 3D printing, design, and creativity skills more conveniently than with other methods.

East Asian Yamagata students 3D printed police whistles, gaining 3D printing and design experience while learning about frequencies; at the end, students could play music pieces on devices they created themselves and teach others to use 3D printers22. Here, 3D printing combines learning about design processes using 3D printing and learning about physics.

East Asian Yilan students used 3D printing to design and decorate cup holders inspired by Atayal influences; these were evaluated by five experts. Overall, these experts ranked the students’ creations well on “novelty” and “singularity.” Novelty referred to “the original style, creativity, and particularity of the work,” while singularity referred to “the painting pattern variability and the unique visual design”23. Here, 3D printing allows students to express creativity in practical design experience.

In Rochester, New York, Vertus Charter School created a program where over six weeks students learned about hands, 3D modeling and printing, and how to create a prosthetic e-NABLE hand using 3D printing24. Hands made by these students serve children with missing fingers as part of a larger e-NABLE community effort25. Here, 3D printing allows students to take up projects with real-world impacts, learning along the way.

At the University of Belgrade, Master’s coursework in Mechanical Engineering involved designing turbocompressor blades using 3D printing, considering certain values for air inlet pressure, inlet temperature, mass flow rate, total pressure ratio, and relative Mach inlet number26. Here, 3D printing is useful at a high level of education as these students design complicated parts.

At the TechnionIsrael Institute of Technology, fourth-year aerospace engineering coursework included rapid prototyping of aircraft models using 3D printing instead of CNC milling. Compared to 3D printing, CNC milling requires more expensive materials and a longer time to fabricate12. At Exeter (NH) High School, high school students use 3D printing for rapid prototyping; as technology teacher David Atwood noted, “all students respond better to project-based learning because it is easier to learn and gain context by doing than to learn simply by reading a textbook.”27. Here, 3D printing facilitated these students’ design projects to be done cheaper and faster.

Concrete-Representational Abstract (CRA)

Concrete-Representational-Abstract (CRA) is an approach to mathematics education where students first physically manipulate concrete objects, then engage with pictorial or other mathematical representations, and finally use abstract notations to solve abstract problems; research has suggested that CRA can be effective for teaching mathematics, especially for students with learning disabilities28‘29. Using CRA for mathematics instruction is linked to the theory of embodied cognition, where the act of understanding mathematical concepts involves engaging the sensory-motor system of our nervous systems along with mathematical imagination. It is possible that the use of tactile 3D printed teaching aids may better prepare the sensory-motor system to recognize the mathematical concepts in their concrete forms30. Historically, the CRA process has been referred to as graduated instructional sequence, used for special education31‘32. 3D printed teaching aids may provide the concrete objects teachers following CRA would require. There are concerns that CRA may be more effective for simple arithmetic than more complex, abstract subjects, such as Calculus33.

Assistive Technologies

If 3D printing technologies could assist students with disabilities in having superior learning outcomes, such technologies could play an important role in alleviating challenges people with disabilities face in STEM studies and employment.

STEM and Disabilities

There is a clear underrepresentation of students and employees with disabilities in STEM compared to the general American population. STEM employees with disabilities face employment and salary challenges.

About 26% of American adults have a disability; common types include mobility, cognitive or mental, independent living, hearing, and vision34. Compared to this population, there are relatively fewer undergraduate students with disabilities, the percentage being 19.4%35. Even fewer of such students pursue STEM deeply, such that only 8.8% of United States doctorate recipients reported to the National Survey of College Graduates’s of having a known disability36. The National Survey of College Graduates’s criteria for having a known disability were reporting a disability that creates “moderate,” “severe,” or “unable to do,” difficulty regarding sight, hearing, walking without assistance, lifting 10 pounds, or cognitive functions such as making decisions36. The most common student disabilities are learning disabilities that have psychological aspects, speech or language impairments, and other health impairments such as a heart condition37. The difficulties for students with disabilities in academics were exemplified by a finding that students with hearing impairments perform worse on standardized exams38. As for employment in STEM occupations, only 9.5% of employed scientists and engineers reported to the National Survey of College Graduates of having a disability; only 7.2% of employed scientists and engineers with a doctorate reported a disability39. Findings suggest that students with disabilities become discouraged from participating in STEM on a broad scale, perhaps because of difficulties understanding content40.

Certain STEM employees with disabilities are paid less than their counterparts without disabilities, as an analysis of 704,013 United States doctorate recipients found that “doctorate recipients with disabilities experienced early in life had annual salaries that were on average $10,580 lower than their non-disabled counterparts, and that this difference was larger in the subset of STEM workers in academia ($14,360 early disability vs no disability)”41. By “disability experienced early in life,” the study authors refer to those who experienced a disability before the age of 25 because many earn their doctorates between 26 and 30 years old41. This finding indicates that these people are valued less financially by their employers.

These data indicate that students with disabilities have difficulties learning STEM subjects: “STEM education frequently engages the senses, particularly vision and hearing […] sensory impairments must be properly accommodated in order for students to be engaged fully as learners”42. If 3D printed teaching aids If teaching aids can significantly assist the learning of students with disabilities, disparities in STEM could be alleviated.

Teaching Aids as Assistive Technology

Teaching aids could assist students with visual impairments, learning disabilities, and mobility impairments. However, there are limitations in uses for hearing and dexterity impairments.

Visual Impairments: 3D printed teaching aids may assist students with visual impairments who could otherwise struggle with visual diagrams, textbook readings, or videos. 3D printed teaching aids may have a price advantage over other teaching aids43. Exemplifying their utility, 3D printed models can represent the translation of mRNA to protein at a ribosome; it may be easier for students with visual impairments to understand the translation of mRNA to protein at a ribosome through touching the mRNA connect with its complimentary tRNA codons as tRNA adds the appropriate amino acid to the polypeptide chain through the model44. Additionally, programming teachers of blind students have used 3D printing for tactile data map visualization45. 3D printing can also be used to teach South Korean students with visual impairments how to read Braille, with students finding the durability of PLA to be conducive to learning, though some students were worried about sharp edges not smoothed out in the researchers’ prints46; other young children with visual impairments may also benefit from 3D printing in their books47. In STEM, 3D printing can be used to help students understand images of celestial objects through feeling a 3D printed elevation map48. Teaching aids can be easily made through public 3D models of cosmic objects49. For non-STEM subjects, 3D printing can be used to represent historical relics, especially ones that may be too large for a student to fully feel in person50. There is room for improvement in teaching aids, specifically in facilitating converting 2D graphs into 3D graphs for teaching visually impaired students about linear equations in a more concrete way51.

Learning Disabilities: Teaching aids could, in tandem with visual slides and auditory instruction, provide an engaging multisensory experience for students with learning disabilities to gain more understanding from lessons40. Students with learning disabilities could engage in self-advocacy by asking their instructors to provide them with teaching aids, though instructors with access to teaching aids should provide them anyway52.

Mobility Impairments: Teaching aids that fit in a student’s hands remove any need for ambulation, e.g. walking around a historical site or relic50.

Hearing Impairments: Students may benefit from the use of teaching aids if instruction is delivered non-audibly such as through a written document with pictures.

Dexterity Impairments: A teacher, teaching assistant, peer, or someone else could manipulate the teaching aid for the student with disability, possibly allowing the student to benefit31.

Teaching Aids

3D printing provides useful teaching aids for chemistry, anatomy, pharmacology, and math.

Chemistry: 3D printing is useful for teaching chemistry. Models of molecules can be made to help students better understand chemistry topics53. Models of molecules such as ferrocene are more cheaply 3D printed than manufactured in other ways54.

Anatomy: 3D printing is useful for teaching anatomy. In small group teaching sessions, there was an improvement in test scores when 3D anatomical models were used for teaching versus when 2D models were used. 96% of students receiving a 3D teaching component scored better than baseline knowledge control, while for 2D, it was 88%55. In addition, the raw materials for printing such models may only cost a few dollars, such as a 75% scale model of the right lung costing only 3.33 US dollars55. 3D printed models of bones were generally found by resident surgical trainees to be effective, accurate training instruments that should be used during resident education56.

Pharmacology: 3D printing is useful for teaching pharmacology to undergraduate students. Students were tasked to use 3D printing to create enzyme inhibitors to better understand a particular enzyme57. Students generally agreed that the activity helped them to better understand medicinal chemistry and that 3D printing has a role in pharmacy education57.

Mathematics

3D printing shows promise in teaching mathematics, which may apply to Calculus AB as explored in this Senior Project.

In one study, 99 students were sorted into two groups. The experimental group exclusively had access to project-based learning using 3D printing to engineer solutions to a series of problems within a transmedia intervention13. The experimental group’s students demonstrated significantly higher math scores than the control group by a p-value of <.00158.

In a separate study, students who were able to use 3D printing to learn about the volume of cubes, spheres, boxes, or cylinders outperformed students who were not able to use 3D printing to learn about these concepts59.

A Harvard student developed a 3D printed water toy to demonstrate Archimedes’s proof of the relation between the volumes of a cylinder, cone, and sphere60.

For more advanced math, 3D modeling can model complicated shapes such as hyperbolic paraboloids61. Famous mathematical shapes such as Apollonian cones may be modeled62. 3D printing may be used for exhibits of mathematical shapes63. 3D printing and modeling have the potential to bring abstract yet interesting geometrical concepts to life.

Role of Teachers

Fully using 3D printing technology in the classroom involves providing STEM and other teachers with 3D printing professional development and access to 3D printers.

Teachers may be unable to access or be unfamiliar with the use of 3D printing, indicating the need for accessibility measures. Teachers struggle to apply 3D printing to teaching: when teachers were surveyed after attending professional development on a variety of subjects, only 57% rated 3D printing as applicable to their teaching compared to 90% for Mobile Application Programming, 86% for internet, and 73% for robotics64. Libraries are increasingly investing in training library patrons in 3D printing and providing them access to 3D printers65. One model for helping school affiliates be more comfortable with 3D printing included providing a space for school affiliates to not only use equipment to make objects but also receive training in safely using equipment66. By having someone knowledgeable in 3D printing present, teachers can ask questions and therefore better incorporate 3D printing into their teaching67. Teachers may be assisted through libraries, professional development, access to 3D printers, and access to experts.

3D printing can be useful for teachers beyond STEM. English teachers can use 3D printing in assignments; for example, students may be tasked with creating symbolic and persuasive models as they seek to use rhetoric with various media68. Although history or social science teachers may be slow to use 3D printing due to perceptions that 3D printing mostly relates to STEM, 3D printing can still be used for humanities projects, such as having students make 3D models of Native American dwellings to learn about Native American culture69. While the humanities may seem unrelated to 3D printing, there are 3D printing use cases for non-STEM teaching.

Students with Disabilities

Teachers may be unprepared to meet the needs of their students with disabilities; access to and knowledge of how to use teaching aids may help them better teach these students.

Teachers can serve as a barrier to student success. Discrete Mathematics involves using various mathematical ideas to solve complicated problems found in reality. One study found that the most common reason K-12 teachers in schools and programs serving students with hearing impairments did not provide their students access to Discrete Mathematics lessons was that they believed “the mathematics level of discrete mathematics concepts was too high for their students”70. This was in contrast to how the National Council of Teacher Mathematics had emphasized teaching students parts of discrete mathematics, such as how to “Understand how mathematical ideas interconnect and build on one another to produce a coherent whole”71 and “Select, apply, and translate among mathematical representations to solve problems”72. Some STEM teachers even discourage students’ use of their approved accommodations52. Globally, teachers feel an area “of most critical need for professional development” is in “teaching students with special needs,” indicating more work is to be done73. Therefore, teachers’ perception of students with disabilities or teachers’ ability to work with students with disabilities can serve as barriers to students’ academic success.

If teaching aids would help students with disabilities in learning a topic, then it would be prudent to train teachers in not only better meeting the needs of their students with disabilities but also in using 3D printing to acquire teaching aids. Professional development for teachers could emphasize the intersection of students with disabilities and teaching aids.

Methods

Calculus AB teaching aids for Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections were created (Fig 1). Students were then presented with a video lesson. The experimental group had access to the teaching aids during the video lesson, while the control group did not. The learning outcomes between the two groups were compared.

3D Printing Disks, Washers, and Volume CrossSections

Learning these concepts is required for a well-rounded understanding of Calculus AB. These concepts involve thinking in 3D.

Disks and Washers involve rotating a graphed area around another line to generate a 3D shape. Volume Cross-Sections involve combining cross-sections of a 2D graph to create a 3D volume.

3D models of Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections were generated using FreeCAD, a 3D modeling software. These 3D models were 3D printed using PLA.

The Experiment

Calculus AB Students at the BASIS, Washington DC High School were divided into an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group was shown a video that included a 3D visualization using the 3D modeling software, explaining Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections. The control group was shown the same video, but only the experimental group could physically interact with the teaching aids. Then, the groups took a survey to gauge their understanding of the lesson. These questions were developed with review from the faculty advisor to be similar to AP Calculus AB questions.

The survey consisted of six questions written in LaTeX using a question set template74 with three questions for normalization, three questions to judge understanding from the lesson, and two questions for students to rate how engaging or helpful the lesson was.

Normalization Questions: Questions 1(a), 1(b), and 1(c) tested general calculus knowledge. They facilitated the comparison of students from similar backgrounds in Calculus AB across the experimental and control groups. They asked students to identify features of a graph, perform integration, perform differentiation, and understand how equations relate.

Content Questions: Question 2(a) evaluated whether students could evaluate the area between two functions, a necessary step for solving Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections problems. Question 2(b) directly evaluated students abilities to solve a Volume Cross-Sections problem. Question 2(c) evaluated students abilities to solve a Disks and Washers problem. Students’ parents were asked to list any medical or accommodations needs; assistance was available for any students with dexterity impairments, such as an assistant circling the answer choices the student selects on the student’s behalf40‘75.

Engagement and Helpfulness Rating: Question 3(a) asked students to compare the lesson with usual Calculus AB lessons in terms of how engaging it was from one to five; in the order from one to five, the ratings were “Much less engaging,” “Less engaging,” “Equally engaging,” “More engaging,” and “Much more engaging.” Similarly, Question 3(b) asked students to compare the lesson with usual Calculus AB lessons in terms of how helpful it was from one to five; in the order from one to five, the ratings were “Much less helpful,” “Less helpful,” “Equally helpful,” “More helpful,” and “Much more helpful.”

Assessment Flaw and Mitigation

Question 2(c) had two semi-correct answer choices, so a 2cbN variable was created.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The answer to answer 2(c) should have been , but onlyandwere provided as answer choices (C) and (D) respectively; (D) was supposed to be the correct answer, but the limits on the integration were erroneous. Both of these answer choices were somewhat similar to the correct answer, with (C) having simply a difference in signs with the correct answer. To compensate, the researcher created a 2cbN variable, marked 1 if the student selected either semi-correct answer choice, but 0 if the student selected either of the other two wrong answer choices. This data point may be useful if all students who chose one of the semi-correct answer choices did so because they understand that these choices were closest to the answer choice. However, the quality of the 2cbN variable as a measurement of academic performance is called into question if many students simply guessed those two answer choices, as having two answer choices marked as correct could significantly increase the chances of guessing leading to a false positive regarding student performance on the exam.

Accounting for Students with Disabilities

Though the researchers were prepared to account for students with disabilities, no participating students reported disabilities that could have impacted their involvement in the experiment.

Researchers played the uniform instructional video using a large screen and audio component, increasing accessibility for visually impaired students40. While the video was audible for all students without hearing impairments present, with minimal disruptive noise in the otherwise quiet classroom, the video still included captions to ensure any students who are hard of hearing or prefer captions were not left out, promoting accessibility76. Watching the video did not require movement, improving accessibility for students with mobility impairments77. Any students with mobility impairments would have been closely monitored to prevent them injury on any sharp angles or non-smoothed corners of the teaching aids31; due to the teaching aids being small enough to fit in one’s lap and hands, no specific lowering of tables or other such furniture accommodations were necessary in the classroom for them to participate fully31. Students were not expected to speak, so students with speech impairments would not have had issues; if students needed to use speech to self-advocate, they would have been patiently listened to and offered the option to communicate using writing instead.

The lesson was about mathematics, so any students with mathematicsrelated learning disabilities, though none identified themselves as possessing such, would have struggled. The CRA approach was used in the planning of the lesson as CRA may improve the accessibility of the lesson for students, as discussed in subsection 2.2. Students were provided with the 3D printed models as concrete representations of the concepts, shown visual representations by video, and then were shown how to solve problems using abstract notation.

Ethics

Students’ parents or guardians gave informed consent to have their students’ data, that is, students’ responses to the survey, be anonymously surveyed. Students were instructed to not write their real names or other personal identifying information on the surveys; students simply wrote an arbitrary and anonymous experiment identification number on the surveys. Students’ identifying information, their names, were only used to verify that the parents had permitted the students’ data collection and were not associated with scores in any way. The researchers were firmly committed to protecting students data privacy.

Students in the control group were offered the opportunity to use the teaching aids after the survey was concluded so they would not miss out on the benefits of using teaching aids. Students who did not choose to participate in the survey had access to the questions for practice after the experiment concluded. All students had access to the survey questions and answers after the survey concluded.

The researcher submitted an Institutional Review Board form proposal describing how the researcher would gather consent, protect student privacy, and responsibly destroy data when finished. The proposal was accepted.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this research such as sample size, recognition of the researcher, minimal haptic feedback in teaching aids, the novelty of the research, limited data on students with disabilities, the effect of the video on the students, the lack of comparison regarding teaching aids made of PLA against teaching aids made of other materials, the issue with question 2(c), the length of the lesson, the timing of the lesson, the subjectivity of questions 3(a) and 3(b), and limited number of teaching aids.

Fifty-seven students participated in the experiment which allowed for some results to be significant. However, having more students would improve the quality of the data and add confidence to conclusions drawn.

The identity of the researcher, Ryan Ting, was unavoidably known to the students who participated in this experiment as Ryan Ting attends the same school as the students and was present during the experiment to ensure its fidelity. Though not instructed to do so, students may have been inclined to vary their effort or engagement and efficacy ratings when taking the survey depending on their attitude towards the researcher.

Students could feel, rotate, and move around the teaching aids, but could not do much more than that, showing a limitation in tactile complexity. For example, one teaching aid not used in this experiment includes a water component that allows students to compare the volume of different shapes78. In comparison, the teaching aids used in this experiment lacked a water component, a vibration component, and additional components that may have added tactile complexity.

Because the students would have recognized that this lesson is exceptional in its being used for research, students may have become more or less engaged, skewing the results of the data.

Due to there being a limited sample size, there were students reporting impactful disabilities, so this study could not conclusively draw findings about how teaching aids assist students with disabilities.

Students may have felt more or less engaged than during a usual lesson due to watching a video. Therefore, the presence of a video may have skewed how engaged students were. Additionally, the presence of a video, a multiple-medium presentation, may have overstimulated certain students, such as students with dyslexia feeling overwhelmed when presented with video40.

There was only one type of teaching aid examined, that being teaching aids 3D printed using PLA as a material; therefore, findings may apply to tactile teaching aids in general, not just ones made of PLA; this is supported by teachers’ beliefs. Teachers generally support the use of physical teaching aids, “teachers indicated that the use of manipulatives is important for implementing the goals of the NCTM Standards with students who have LD [“learning disabilities”32] and ED [“emotional/behavioral disorders”32]”32. The NCTM standards’ goals are to “emphasize complex math tasks requiring problem solving and mathematical reasoning skills and deemphasize role computation and memorization tasks,”79 hopefully leading to a superior learning experience.

Because question 2(c) had no definitive answer, it was difficult to conclusively determine which was the right question. While there was an attempt to correct this during the analysis of data, the question may be inconclusive. Therefore, this experiment cannot make conclusive judgments regarding the teaching aids’ efficacy on teaching Disks and Washers, which question 2(c) represented.

The video length was less than fifteen minutes and while thirty five minutes were given to the students for completing the survey, though most students only took about ten minutes. A longer video lesson may have led to greater differences in student scores and outcomes. In addition, the lesson was prerecorded and not live with in-person questions and answers, possibly leading to an inferior learning experience. A longer survey may have allowed for more data to conclusively determine any significant difference caused by the teaching aids as more data would be available.

The lesson occurred in May, meaning students had already been exposed to the lesson content two months before, in March. In addition, these students had already taken their Calculus AB test so they may have studied this lesson on their own time. Because the Senior Project which produced this experiment began in March, preparing the lesson to be done in March was infeasible. In addition, the researcher did not want to use the valuable class time before the Calculus AB test. The result may have been that students performed better than they would if they were learning the content for the first time rather than exposed to a refresher. Additionally, in the context of the BASIS DC curriculum, while Juniors might not need to use the concepts of Disks and Washers and Volume Cross-Sections in the future, Sophomores would take Advanced Placement Calculus AB which also tests understanding of these concepts; this may have encouraged Sophomores to put more effort than Juniors into understanding the content and performing better.

The presence of a 3D visualization component in the video may have confounded the control group by providing them with enough 3D visualization experience that the addition of the 3D printed teaching aids added minimally to their learning experience.

Questions 3a and 3b asked students to compare the engagement and efficacy of the lesson to normal Calculus AB lessons. However, this scale is subjective, so students’ responses may not accurately reflect how engaging or effective the lesson was.

There were only three teaching aids available. If there were more, such as multiple teaching aids demonstrating different degree cross-sections of the Disks and Washers model, then the lesson may have been more effective.

The study did not correct for multiple subgroup analyses possibly increasing the risk of a Type I (false positive) error, a decision made based on the small sample size. Applying the strict Bonferroni method or other methods to account for multiple subgroup analyses could have overly diminished the studys statistical power, increasing the risk of a Type II error (false negative). In light of this, the subgroup findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Results

The experiment found one significant result with a p-value of 0.05 or lower, but has not conclusively determined any causal relationship between the use of 3D printed teaching aids and students learning outcomes in Calculus AB. Several other subgroup comparisons led to insignificant results.

Statistical Methods

The researcher normalized scores for the content questions, seeking to minimize the effect of certain students being more capable at Calculus AB than others. For each student, their average score between questions 1(a), 1(b), and 1(c) was determined, with every question being scored a “1” if they got it correct and a “0” if they got it wrong. Then, for each content question, this average was subtracted from the student’s raw score. For example, if the student scored a “1” on question 2(a), “0” on question 2(b), and “1” on question 2(c), while scoring a “1” on question 1(a), “0” on question 1(b), and “0” on question 1(c), then their average score for questions 1(a), 1(b), and 1(c) would be approximately 0.333, so their normalized scores for the content questions would be “0.667,” “-0.333,” and “0.667” respectively. The resulting normalized scores were referred to as “2aN,” “2bN,” and “2cN,” with “Average Score Normalized” being each student’s average score of 2aN and 2bN, not including 2cN due to its flaws.

The researcher used a two-sample t-test to find a one-tailed p-value. The researcher chose the two-sampled t-test because the data met the tests assumptions. Survey outcome variables followed continuous normal distributions, students were randomly assigned into subgroups independent of their outcome variables, and the variance in compared groups met the condition of homogeneity of variance.

The researcher used the benchmark of a p-value of 0.05 or less to claim a result was significant. Data are truncated unless otherwise specified.

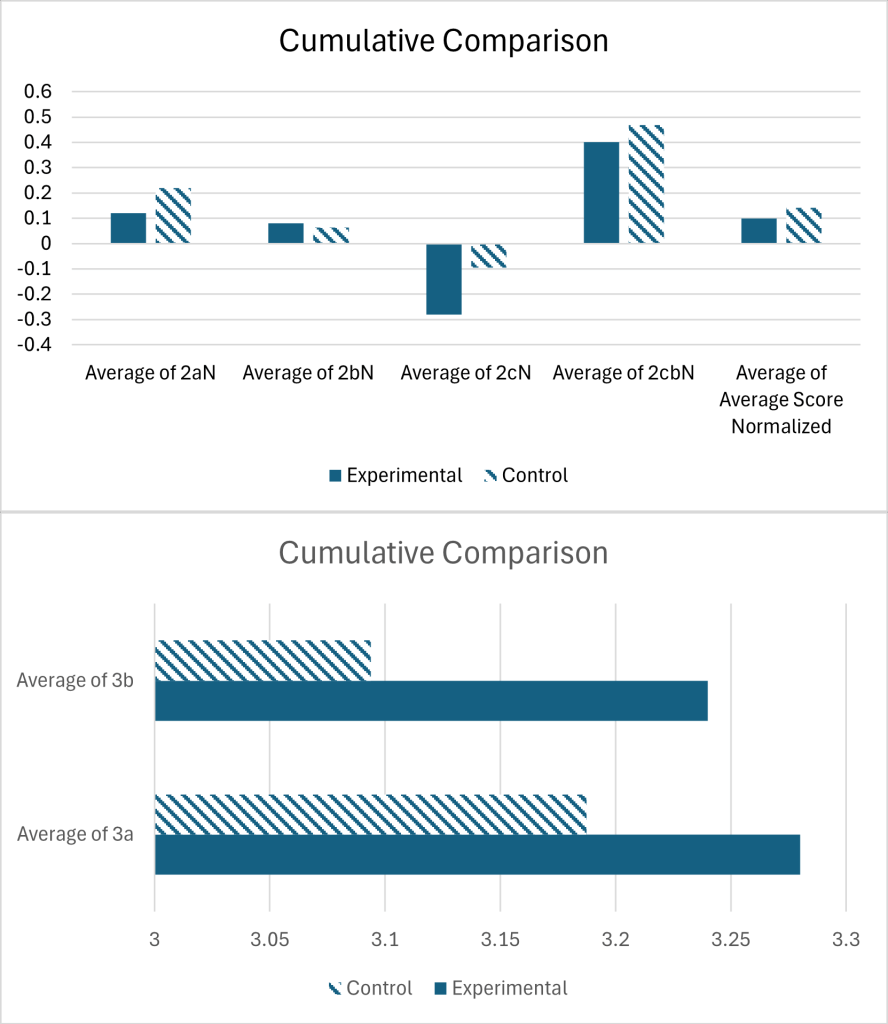

Overall Differences

Shown in Figure 2, No overall differences between the experimental and control groups for performance on the content or rating questions were significant with a p-value of 0.05 or less. Data shown in Table 1.

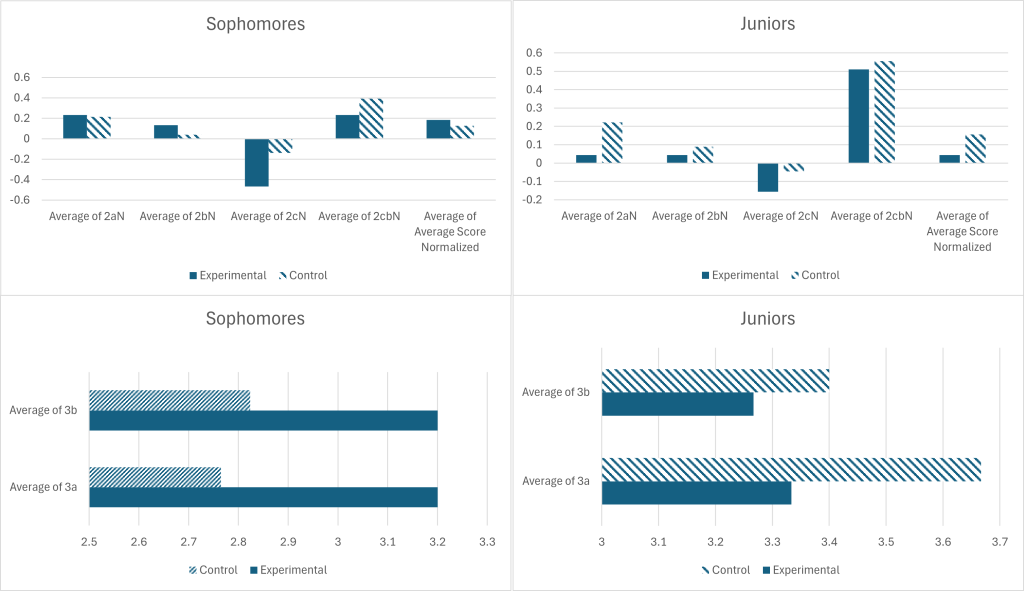

Grade-Level Subgroup Analyses

Shown in Figure 3, there was no evidence that grade levels impacted how students responded to the teaching aids. Data shown in Table 2.

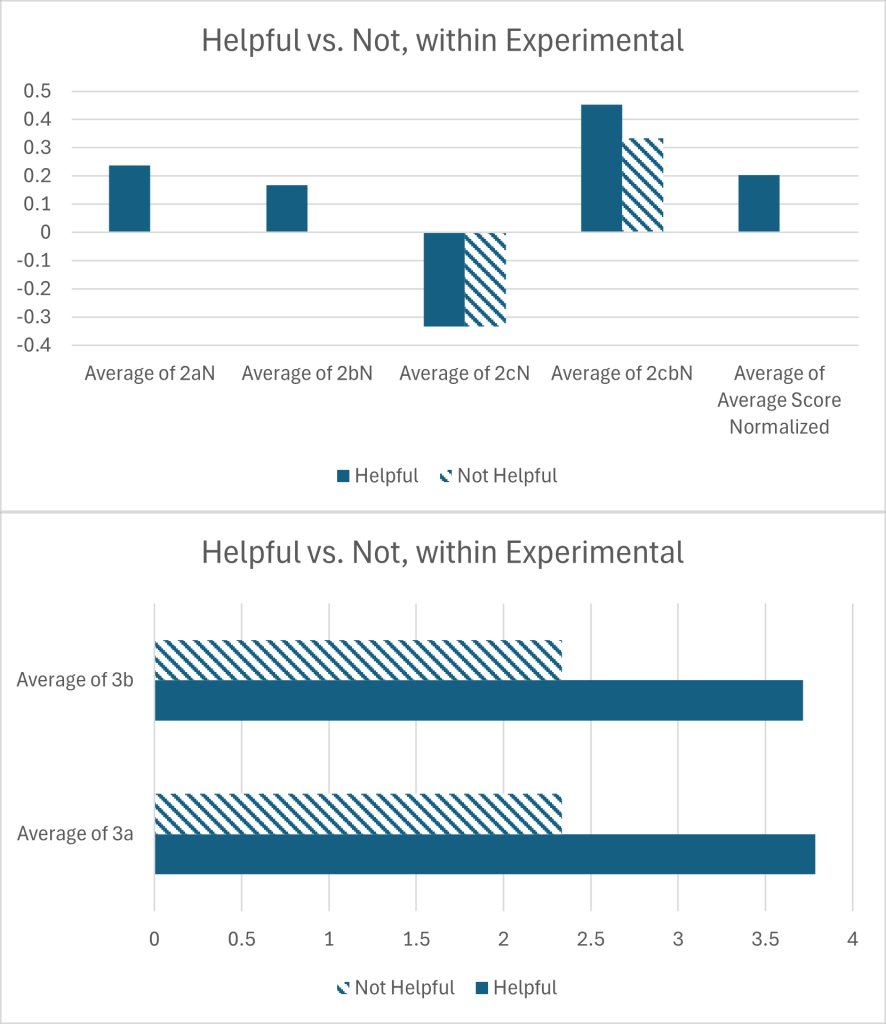

“Helpful” vs. “Not Helpful” Performance

To examine how different students responded to the intervention, the data were broken down with the “helpful” subgroups including students whose average rating of questions 3(a) and 3(b) was above 3, and “not helpful” including those whose average rating of questions 3(a) and 3(b) were below 3. There were significant differences found in relevant benefits.

Within Experimental Group

Shown in Figure 4, within the experimental group, students in the helpful group performed significantly better than those in the not helpful group on 2aN and Average Score Normalized. For 2aN, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.238,SD = 0.479,n = 14) than those in the not helpful group (M = 0.000,SD = 0.210,n = 6), with significance (t(15.073) = 3.721,p = 0.001). For Average Score Normalized, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.202,SD = 0.449,n = 14) than those in the not helpful group (M = 0.000,SD = 0.278,n = 6), with significance (t(17.964) = 3.235,p = 0.002). Data are shown in Table 3.

Broadly

Shown in Figure 5, it was found that across the control and experimental groups together, students in the helpful group performed better than those in the not helpful group on 2aN, 2bN, 2cbN, and Average Score Normalized. For 2aN, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.252, SD = 0.501, n = 29) than those in the not helpful group (M = 0, SD = 0.398, n = 15) with significance (t(40.112) = 4.072, p < 0.001). For 2bN, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.149, SD = 0.574, n = 29) than those in the not helpful group (M = -0.066, SD = 0.606, n = 15), with significance (t(25.821) = 1.910, p = 0.033). For 2cbN, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.459, SD = 0.313, n = 29) than students in the not helpful group (M = 0.333, SD = 0.398, n = 15), with significance (t(19.743) = 2.817, p = 0.005). For Average Score Normalized, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.201, SD = 0.498, n = 29) than students in the not helpful group (M = -0.033, SD = 0.418, n = 15), with significance (t(37.818) = 3.624, p < 0.001). Data are shown in Table 3.

Those in the not helpful group (M = −0.066,SD = 0.606,n = 15), with significance (t(25.821) = 1.910,p = 0.033). For 2cbN, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.459,SD = 0.313,n = 29) than students in the not helpful group (M = 0.333,SD = 0.398,n = 15), with significance (t(19.743) = 2.817,p = 0.005). For Average Score Normalized, students in the helpful group performed better (M = 0.201,SD = 0.498,n = 29) than students in the not helpful group (M = −0.033,SD = 0.418,n = 15), with significance (t(37.818) = 3.624,p < 0.001). Data are shown in Table 3.

Helpful vs. Not, Within Control

Shown in Figure 6, within the control group, students within the helpful group performed better than those in the not helpful group on 2aN, 2cbN, and Average Score Normalized. For 2aN, students within the helpful group performed better (M = 0.266,SD = 0.537,n = 15) than those in the not helpful group (M = 0.000,SD = 0.500,n = 9), with significance (t(18.989) = 2.384,p = 0.014). For 2cbN, students within the helpful group performed better (M = 0.466,SD = 0.328,n = 15) than those in the not helpful group (M = 0.333,SD = 0.408,n = 9), with significance (t(12.095) = 2.145,p = 0.026). For Average Score Normalized, students within the helpful group performed better (M = 0.200,SD = 0.557,n = 15) than those in the not helpful group (M = −0.055,SD = 0.506,n = 9) with significance (t(19.566) = 2.178,p = 0.021). Data are shown in Table 4.

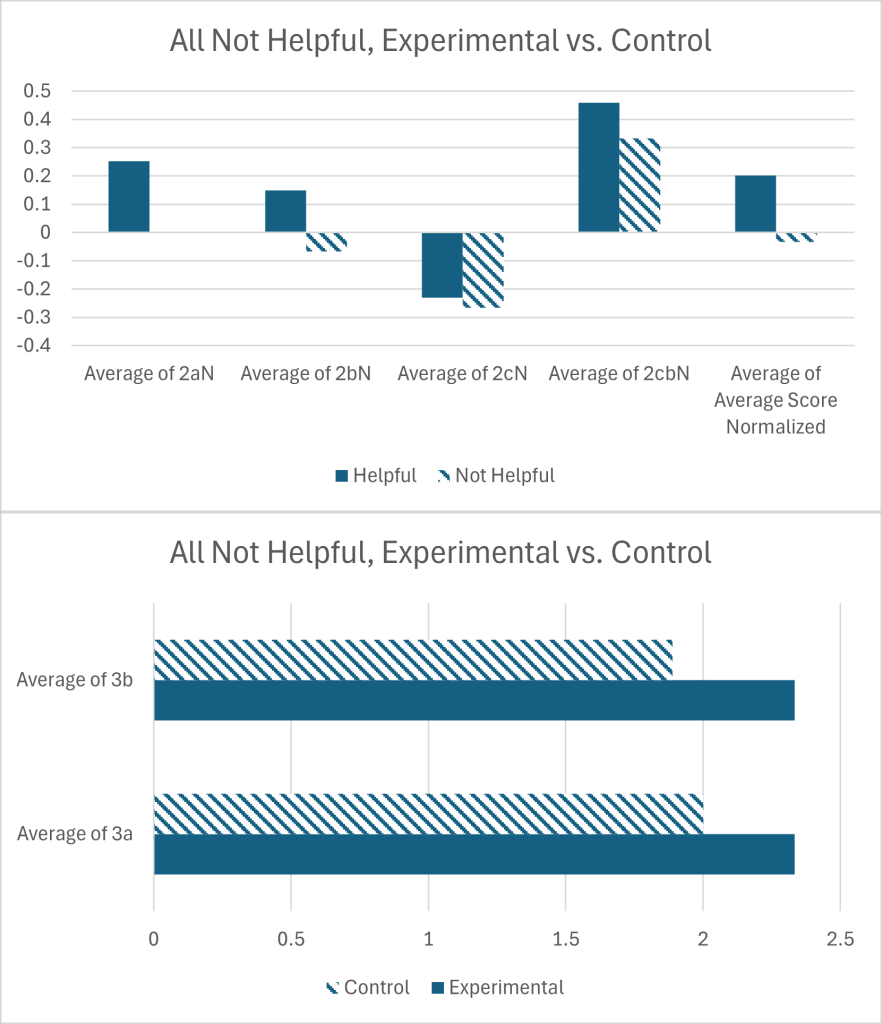

All Not Helpful, Experimental vs. Control

Shown in Figure 7, for students within the not helpful group, those also in the experimental group rated the helpfulness of the lesson higher (M = 2.333,SD = 0.516,n = 6) than those in the control group (M = 1.888,SD = 0.333,n = 9), with significance (t(6.172) = 3.864,p = 0.004). Data are shown in Table 5.

Discussion

Overall, teaching aids did not have significant effects on students survey responses. There were some significant comparisons across subgroups.

Shown in Table 3, broadly students who rated the lesson as more helpful tended to perform better. However, this cannot be interpreted as related to the intervention as within the control group, those who rated the lesson as more helpful performed better, seen in Figure 6. Perhaps the 3D visualization component of the video or other aspects of the lesson significantly helped these students better understand the course material; the presence of a video may have biased student engagement due to novelty or other reasons40.

The finding that students ratings of the lessons helpfulness actually translated to improved performance supports the idea that students are able to generally discern how helpful a lesson was or was not. This idea can be taken further: because the helpfulness ratings for the experimental and control groups were similar, the teaching aids were not helpful or unhelpful . However, research has suggested that students do not reliably predict how well a lesson has benefited them, so this conclusion cannot be confidently drawn80‘81. Because students in the sample were not impacted by disabilities, the study was unable to find any results relating the intervention and students with disabilities.

The grade level of the students had no significant effect on how well they performed when given access to the teaching aids. This may be because students who take Calculus AB at BASIS DC may be uniformly prepared no matter their grade level due to having taken the same mathematics classes in preparation for Calculus AB. It could also be because there is no significant difference in students learning abilities between these two grades.

Of students who rated the lesson as not helpful, those with the intervention still rated the lessons helpfulness more highly those without the intervention. This correlation is not necessarily causation: perhaps the inclusion of 3D printed teaching aids introduced a novelty effect causing students to feel the lesson was more helpful than it actually was. Additionally, students may have simply believed that 3D printed teaching inherently make a lesson more helpful by their presence, an idea that would correlate the perceived effort of a lesson the showmanship with the efficacy of the lesson. If 3D printed teaching aids generally make students believe a lesson is more helpful, then the implementation of 3D printed teaching aids could possibly improve students attitudes towards math class; they may better appreciate the classes as means for their education.

The overall lack of correlation between the teaching aid intervention and differences in survey responses may provide evidence for the concerns raised about CRA in general, that CRA is less effective when used to teach subjects of complexity and abstraction beyond simple arithmetic33. However, we have seen studies demonstrating its use in higher education, such as undergraduate pharmacology courses57. This study has not provided conclusive evidence linking the use of 3D printed teaching aids and improved learning outcomes for Calculus AB students.

Conclusion

It cannot conclusively be determined that touching teaching aids assists students in learning Disks, Washers, and Volume Cross-Sections. However, for students who generally did not find the lesson helpful, the intervention made the lesson seem more helpful.

Results Suggest that among students some learn better than others when presented with the 3D visualization or other aspects of the video lecture. The ability to touch the teaching aid had a comparatively insignificant effect on students’ performance.

This research also lacked any participants with significant disabilities so it cannot draw any conclusions regarding the efficacy of teaching aids for these students.

Further Research

Further research includes performing similar research with superior resources, the use of more tactilely complex teaching aids, examining other Calculus AB and mathematical topics, preparing teachers for using teaching aids with students with disabilities, other kinds of tactile teaching aids, and using teaching aids to assist students with hearing or dexterity impairments.

Those seeking to further study the efficacy of teaching aids may gain several lessons from this experiment. One lesson is to increase the number of survey questions, allowing for more topics to be examined and allowing for each student to have multiple opportunities to demonstrate understanding or lack of understanding in each topic. In this way, there may be more opportunities to find significant results regarding the efficacy of teaching aids. Another lesson is to increase the number and variety of students. Having a greater number of students allows for more certainty when determining the significance of results. Having a greater variety of students, especially including more students with disabilities, would allow for analysis of the effects of teaching aids on these subgroups. Experimenting with students who have not seen this lesson material before may also yield different results, as the students involved had already been exposed to the lesson material. Finally, efforts can be made to control for any effects of showing 3D visualizations through video and any effects of novelty and recognition of the researcher.

Examples of tactile complexity in teaching aids could be the use of multiple parts to create one teaching aid, similar to how many Lego bricks form one design. By allowing students to build the teaching aid, they may have a more interesting and engaging tactile experience with the teaching aids.

Advanced mathematical concepts such as Riemann Sums, Sinusoidal Functions, and Infinite Series with Finite Sums show promise in being taught using teaching aids. Riemann Sums could be shown through rectangles of increasing fixed height appended to the bottom of a function that is being modeled using the Riemann Sums. Sinusoidal Functions, although 2D, could be made with 3D models that allow students to see the functions along two axes in the real world. Infinite Series with Finite Sums could be shown using a series of blocks of decreasing area which, when combined, roughly add up to an area, just as the terms of the Infinite Series with Finite Sums eventually add up to one finite sum.

There is room for teachers to be trained in how to use teaching aids with students with disabilities. Teachers who have been trained in a coherent program, that is “consistency in messages to and expectations of candidates throughout their coursework, field placements, and assessments”, express better outcomes when teaching students with learning disabilities82. edTPA is an assessment for aspiring teachers used in “837 teacher preparation programs in 41 states and the District of Columbia”83; for edTPA, aspiring teachers submit a video of them teaching a lesson along with some essays explaining the thought process behind the lesson83. Not only is there a need for more thought into implementing training for teaching students with learning disabilities in coherent programming82, especially as more and more students with learning disabilities enter general education classrooms83, but there is also a need for research into best practices in professional development for teachers working with both teaching aids and students with disabilities, especially as “What seems to be missing at the moment is a curriculum that organizes the 3D printing activities in a manner that helps teachers and instructors design and facilitate structured learning events”84. This may be incorporated into assessments such as edTPA to spread these ideas among teachers.

While this research examined 3D printed teaching aids made of PLA, there are other options to explore. Teaching aids made of foam may be more accessible to students who do not feel comfortable around hard objects; teaching aids made of Lego Bricks may be more relatable and therefore more engaging to students. The best choices for teaching aids would balance affordability, effectiveness in the classroom, and sustainability or other considerations.

There may be research done to examine how students with hearing or dexterity impairments may be best served using teaching aids. There may be best practices for teachers to ensure inclusive instruction by providing different methods of interaction with the teaching aids and accompanying explanations of the symbolism of the teaching aids’ aspects.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written through the BASIS DC High School Senior Project program. Advisors included Mr. Reich from BASIS DC, Dr. Egenrieder from Virginia Tech, and Dr. Hausdorff from BASIS DC. The paper was reviewed by the National High School Journal of Science.

References

- AP Calculus AB. Learn all about the course and exam. Already enrolled? Join your class in My AP.. College Board. url: https://apstudents. collegeboard.org/courses/ap-calculus-ab (visited on 05/08/2025). [↩]

- JE Hagman, E Johnson, and BK Fosdick. Factors contributing to students and instructors experiencing a lack of time in college calculus. International Journal of STEM Education 4.1 (June 2017). [↩]

- E Kim, M Batul, S Bever, A Mohammed, A Nepomunceno, H Owusu, A Hartstone-Rose, and KL Mulvey. The World Smarts STEM Challenge: A promising approach to fostering STEM and global competence skills for adolescents in the US and Ghana. PLOS ONE 19.12 (Dec. 2024). Ed. by AB Mahmoud, e0311116 [↩]

- J Ellis, BK Fosdick, and C Rasmussen. Women 1.5 Times More Likely to Leave STEM Pipeline after Calculus Compared to Men: Lack of Mathematical Confidence a Potential Culprit. PLOS ONE 11.7 (July 2016). Ed. by E Manalo, e0157447 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- . AP Calculus AB. Learn all about the course and exam. Already enrolled? Join your class in My AP.. College Board. url: https://apstudents.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-calculus-ab (visited on 05/08/2025). [↩]

- P Burdman and V Anderson. Calculating the Odds: Counselor Views on Math Coursetaking and College Admissions. Research rep. Just Equations, Sept. 2022. url: https://justequations.org/resource/calculatingthe-odds-counselor-views-on-math-coursetaking-and-collegeadmissions [↩]

- P Burdman and V Anderson. Calculating the Odds: Counselor Views on Math Coursetaking and College Admissions. Research rep. Just Equations, Sept. 2022. url: https://justequations. org/resource/calculating-the-odds-counselor-views-on-mathcoursetaking-and-college-admissions [↩]

- L Ranakoti, B Gangil, SK Mishra, T Singh, S Sharma, R Ilyas, and S El-Khatib. Critical Review on Polylactic Acid: Properties, Structure, Processing, Biocomposites, and Nanocomposites. Materials 15.12 (June 2022), p. 4312. url: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/12/4312 [↩]

- L Ranakoti, B Gangil, SK Mishra, T Singh, S Sharma, R Ilyas, and S ElKhatib. Critical Review on Polylactic Acid: Properties, Structure, Processing, Biocomposites, and Nanocomposites. Materials 15.12 (June 2022), p. 4312. url: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/12/4312 [↩]

- L Ranakoti, B Gangil, SK Mishra, T Singh, S Sharma, R Ilyas, and S El-Khatib. Critical Review on Polylactic Acid: Properties, Structure, Processing, Biocomposites, and Nanocomposites. Materials 15.12 (June 2022), p. 4312. url: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/12/ 4312 [↩]

- N Gallup and JM Pearce. The Economics of Classroom 3-D Printing of Open-Source Digital Designs of Learning Aids. Designs 4.4 (Nov. 2020), p. 50. url: https://www.mdpi.com/24119660/4/4/50 [↩]

- E Kroll and D Artzi. Enhancing aerospace engineering students learning with 3D printing windtunnel models. Rapid Prototyping Journal 17.5 (Aug. 2011), pp. 393–402 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A Stansell and T Tyler-Wood. Digital Fabrication for STEM Projects: A Middle School Example. In: 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). IEEE, July 2016, pp. 483–485 [↩] [↩]

- N Gallup and JM Pearce. The Economics of Classroom 3-D Printing of Open-Source Digital Designs of Learning Aids. Designs 4.4 (Nov. 2020), p. 50. url: https://www.mdpi.com/2411-9660/4/4/50 [↩]

- S Ford and T Minshall. Where and how 3D printing is used in teaching and education. en. Additive Manufacturing (2019). url: https://www. repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/288041 [↩]

- T Rayna and L Striukova. Assessing the effect of 3D printing technologies on entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 164 (Mar. 2021), p. 120483 [↩]

- S Ford and T Minshall. Where and how 3D printing is used in teaching and education. en. Additive Manufacturing (2019). url: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/ handle/1810/288041 [↩]

- M Huleihil. 3D printing technology as innovative tool for math and geometry teaching applications. IOP

Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 164 (Jan. 2017), p. 012023 [↩]

- EA Slavkovsky. “Feasibility Study For Teaching Geometry and Other Topics Using Three-Dimensional Printers”. MA thesis. Harvard University, Oct. 2012. url: https:// people.math.harvard.edu/~knill/3dprinter/documents/slavkovsky_ thesis.pdf [↩]

- A Brown. 3D Printing in Instructional Settings: Identifying a Curricular Hierarchy of Activities. TechTrends 59.5 (Aug. 2015), pp. 16– 24 [↩]

- S Ford and T Minshall. Where and how 3D printing is used in teaching and education. en. Additive Manufacturing (2019). url: https://www.repository. cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/288041 [↩]

- M Makino, K Suzuki, K Takamatsu, A Shiratori, A Saito, K Sakai, and H Furukawa. 3D printing of police whistles for STEM education. Microsystem Technologies 24.1 (Mar. 2017), pp. 745–748 [↩]

- JY Chao, HY Po, YS Chang, and LY Yao. The study of 3D printing project course for indigenous senior high school students in Taiwan. eng. In: 2016 International Conference on Advanced Materials for Science and Engineering (ICAMSE). IEEE, Nov. 2016, pp. 68–70 [↩]

- S Jacobs, J Schull, P White, R Lehrer, A Vishwakarma, and A Bertucci. e-NABLING education: Curricula and models for teaching students to print hands. In: 2016 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). IEEE, Oct. 2016, pp. 1– 4 [↩]

- S Jacobs, J Schull, P White, R Lehrer, A Vishwakarma, and A Bertucci. e-NABLING education: Curricula and models for teaching students to print hands. In: 2016 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). IEEE, Oct. 2016, pp. 1–4 [↩]

- NZ Jankovi, MZ Slijepevi, S antrak, and II Gaanski. Application of 3D printing in M.Sc. studies Axial turbocompressors. In: 2016 International Conference Multidisciplinary Engineering Design Optimization (MEDO). IEEE, Sept. 2016, pp. 1–4 [↩]

- G Lacey. 3D Printing Brings Designs to Life. English. Tech Directions 70.2 (Sept. 2010). Copyright – Copyright Prakken Publications, Inc. Sep 2010; Document feature – Photographs; Last updated – 2024-11-29, pp. 17– 19. url: https://www.proquest.com/docview/747627873 [↩]

- TR Westbrook. “Evaluating the effectiveness of experiential learning with concrete-representational-abstract instructional technique in a college statistics and algebra course”. English. Copyright – Database copyright ProQuest LLC; ProQuest does not claim copyright in the individual underlying works; Last updated – 2025-01-22; SubjectsTermNotLitGenreText – Secondary Education; Course Descriptions; Experiential Learning; Learning Processes; Teaching Methods; Academic Achievement; Cognitive Style; Lesson Plans; High School Graduates; Educational Change; Student Interests; College Students; Nontraditional Students; Course Content; School Holding Power; Grade 1; College Mathematics; Thinking Skills; Graphing Calculators. PhD thesis. 2011, p. 324. url: https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/evaluatingeffectiveness-experiential-learning/docview/927588674/se-2 [↩]

- T Anstrom. Supporting Students in Mathematics Through The Use of Manipulatives. Center for Implementing Technology in Education. 2006. url: https://www.scribd.com/document/77857160/SupportingStudents-in-Mathematics-Through-the-Use-of-Manipulatives (visited on 11/27/2025). [↩]

- R Nemirovsky and F Ferrara. Mathematical imagination and embodied cognition. Educational Studies in Mathematics 70.2 (Sept. 2008), pp. 159–174 [↩]

- NW Moon, RL Todd, DL Morton, and E Ivey. “Findings from Research and Practice for MiddleGrades through University Education”. In: Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. STEM. Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012. url: https://hourofcode.com/ files/accommodating-students-with-disabilities.pdf [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- P Maccini and JC Gagnon. Best Practices for Teaching Mathematics to Secondary Students with Special Needs. Focus on Exceptional Children 32.5 (Jan. 2000). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- BS Witzel, CD Mercer, and MD Miller. Teaching Algebra to Students with Learning Difficulties: An Investigation of an Explicit Instruction Model. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice 18.2 (May 2003), pp. 121–131 [↩] [↩]

- V Varadaraj, JA Deal, J Campanile, NS Reed, and BK Swenor. National Prevalence of Disability and Disability Types Among Adults in the US, 2019. JAMA Network Open 4.10 (Oct. 2021), e2130358 [↩]

- NSF 19-304 TABLE 2-6 Disability status of undergraduate students, by age, institution type, financial aid, and enrollment status: 2016. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2016. url: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/data (visited on 05/09/2025). [↩]

- NSF 19-304 TABLE 7-6 Doctorate recipients, by field and disability status: 2017. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2017. url: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/data (visited on 05/09/2025). [↩] [↩]

- Students With Disabilities. Condition of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. May 2024. url:https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-withdisabilities (visited on 05/15/2025). [↩]

- CB Traxler. The Stanford Achievement Test, 9th Edition: National Norming and Performance Standards for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 5.4 (Sept. 2000), pp. 337–348 [↩]

- NSF 19-304 TABLE 9-8 Employed scientists and engineers, by occupation, highest degree level, and disability status: 2017. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2017. url: https://ncses. nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/data (visited on 05/09/2025). [↩]

- NW Moon, RL Todd, DL Morton, and E Ivey. “Findings from Research and Practice for MiddleGrades through University Education”. In: Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. STEM. Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012. url: https://hourofcode.com/files/accommodating-students-withdisabilities.pdf [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- F Castro, E Stuart, J Deal, V Varadaraj, and BK Swenor. STEM doctorate recipients with disabilities experienced early in life earn lower salaries and are underrepresented among higher academic positions. Nature Human Behaviour 8.1 (Nov. 2023), pp. 72–81 [↩] [↩]

- NW Moon, RL Todd, DL Morton, and E Ivey. “Findings from Research and Practice for MiddleGrades through University Education”. In: Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. STEM. Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012. url: https://hourofcode.com/files/accommodating-students-withdisabilities.pdf [↩]

- JH I, RA Harianto, E Chen, YS Lim, W Jo, HJ Lee, and MW Moon. 3D Literacy Aids Introduced in Classroom for Blind and Visually Impaired Students. Journal of Blindness Innovation and Research 6.2 (2016). [↩]

- A Agarwal, S Jeeawoody, and M Yamane. 3D-Printed Teaching Aids for Students with Visual Impairments. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine 5 (Mar. 17, 2014), p. 100042. url: http://diagramcenter.org/3d-printing.html [↩]

- SK Kane and JP Bigham. Tracking @stemxcomet: teaching programming to blind students via 3D printing, crisis management, and twitter. In: Proceedings of the 45th ACM technical symposium on Computer science education. SIGCSE 14. ACM, Mar. 2014 [↩]

- JH I, RA Harianto, E Chen, YS Lim, W Jo, HJ Lee, and MW Moon. 3D Literacy Aids Introduced in Classroom for Blind and Visually Impaired Students. Journal of Blindness Innovation and Research 6.2 (2016). [↩]

- A Stangl, J Kim, and T Yeh. 3D printed tactile picture books for children with visual impairments: a design probe. In: Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Interaction design and children. IDC14. ACM, June 2014 [↩]

- N Grice, C Christian, A Nota, and P Greenfield. 3D Printing Technology: A Unique Way of Making Hubble Space Telescope Images Accessible to Non-Visual Learners. Journal of Blindness Innovation and Research 5.1 (2015). [↩]

- SS Horowitz and PH Schultz. Printing Space: Using 3D Printing of Digital Terrain Models in Geosciences Education and Research. Journal of Geoscience Education 62.1 (Feb. 2014), pp. 138– 145 [↩]

- J Wonjin, HI Jang, RA Harianto, JH So, H Lee, HJ Lee, and MW Moon. Introduction of 3D Printing Technology in the Classroom for Visually Impaired Students. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 110.2 (Mar. 2016), pp. 115–121 [↩] [↩]

- N Al-Rajhi, A Al-Abdulkarim, HS Al-Khalifa, and HM Al-Otaibi. Making Linear Equations Accessible for Visually Impaired Students Using 3D Printing. In: 2015 IEEE 15th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies. IEEE, July 2015, pp. 432–433 [↩]

- MA Pfeifer, EM Reiter, JJ Cordero, and JD Stanton. Inside and Out: Factors That Support and Hinder the Self-Advocacy of Undergraduates with ADHD and/or Specific Learning Disabilities in STEM. CBELife Sciences Education 20.2 (June 2021). Ed. by SM Lo, ar17 [↩] [↩]

- HK Wu, JS Krajcik, and E Soloway. Promoting understanding of chemical representations: Students use of a visualization tool in the classroom. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 38.7 (Aug. 2001), pp. 821–842 [↩]

- VF Scalfani and TP Vaid. 3D Printed Molecules and Extended Solid Models for Teaching Symmetry and Point Groups. Journal of Chemical Education 91.8 (Apr. 2014), pp. 1174–1180. eprint: https://doi. org/10.1021/ed400887t. url: https://doi.org/10.1021/ed400887t [↩]

- CF Smith, N Tollemache, D Covill, and M Johnston. Take away body parts! An investigation into the use of 3Dprinted anatomical models in undergraduate anatomy education. Anatomical Sciences Education 11.1 (July 2017), pp. 44–53 [↩] [↩]

- JB Hochman, C Rhodes, D Wong, J Kraut, J Pisa, and B Unger. Comparison of cadaveric and isomorphic threedimensional printed models in temporal bone education. The Laryngoscope 125.10 (Aug. 2015), pp. 2353–2357 [↩]

- S Hall, G Grant, D Arora, A Karaksha, A McFarland, A Lohning, and S Anoopkumar-Dukie. A pilot study assessing the value of 3D printed molecular modelling tools for pharmacy student education. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 9.4 (July 2017), pp. 723–728 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A Stansell and T TylerWood. Digital Fabrication for STEM Projects: A Middle School Example. In: 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). IEEE, July 2016, pp. 483–485 [↩]

- M Huleihil. 3D printing technology as innovative tool for math and geometry teaching applications. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 164 (Jan. 2017), p. 012023 [↩]

- EA Slavkovsky. “Feasibility Study For Teaching Geometry and Other Topics Using Three-Dimensional Printers”. MA thesis. Harvard University, Oct. 2012. url: https://people.math.harvard.edu/~knill/3dprinter/documents/slavkovsky_thesis.pdf [↩]

- H Segerman. 3D Printing for Mathematical Visualisation. The Mathematical Intelligencer 34.4 (Sept. 2012), pp. 56–62 [↩]

- O Knill and E Slavkovsky. Illustrating Mathematics using 3D Printers. 2013. arXiv: 1306.5599 [math.HO]. url: https://arxiv.org/abs/1306. 5599 [↩]

- M Rainone, C Fonda, and E Canessa. IMAGINARY Math Exhibition using Low-cost 3D Printers. Sept. 19, 2014. arXiv: 1409.5595 [cs.CY]. url: https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.5595 [↩]

- N Al-Mouh, HS Al-Khalifa, SA Al-Ghamdi, N Al-Onaizy, N Al-Rajhi, W Al-Ateeq, and B Al-Habeeb. A professional development workshop on advanced computing technologies for high and middle school teachers. In: 2016 15th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET). IEEE, Sept. 2016, pp. 1–4 [↩]

- S Ford and T Minshall. Where and how 3D printing is used in teaching and education. en. Additive Manufacturing (2019). url: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/288041 [↩]

- C Kitts and A Mahacek. The Santa Clara University Maker Lab: Creating the Lab, Engaging the Community, and Promoting Entrepreneurial-minded Learning. English. Name – Santa Clara University; Copyright – ľ 2017. Notwithstanding the ProQuest Terms and Conditions, you may use this content in accordance with the associated terms available at https://peer.asee.org/about ; Last updated – 2024-08-28. June 2017. url: http://search.proquest.com.ezpprod1.hul.harvard.edu/conference-papers-proceedings/santaclara-university-maker-lab-creating/docview/2317828666/se-2 [↩]

- R Maloy and I Laroche. Student-Centered Teaching Methods in the History Classroom: Ideas, Issues, and Insights for New Teachers. Social Studies Research and Practice 5.3 (2017), pp. 46–61 [↩]

- A Van Epps, D Huston, J Sherrill, A Alvar, and A Bowen. How 3D Printers Support Teaching in Engineering, Technology and Beyond. Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology 42.1 (Oct. 2015), pp. 16–20 [↩]

- R Maloy and I Laroche. Student-Centered Teaching Methods in the History Classroom: Ideas, Issues, and Insights for New Teachers. Social Studies Research and Practice 5.3 (2017), pp. 46– 61 [↩]

- CM Pagliaro and KL Kritzer. Discrete Mathematics in Deaf Education: A Survey of Teachers Knowledge and Uses. American Annals of the Deaf 150.3 (June 2005), pp. 251–259 [↩]

- CW Midgett and SK Eddins. NCTMs Principles and Standards for School Mathematics: Implications for Administrators. NASSP Bulletin 85.623 (Mar. 2001), pp. 35–42 [↩]

- CW Midgett and SK Eddins. NCTMs Principles and Standards for School Mathematics: Implications for Administrators. NASSP Bulletin 85.623 (Mar. 2001), pp. 35– 42 [↩]

- TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. OECD, June 2014. url: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/ talis-2013-results_9789264196261-en.html [↩]

- P Adajar. paolo-pset. Website. July 11, 2022. url: https:// github.com/padajar/paolo-pset [↩]

- G Stefanich. Inclusive science strategies. [Greg Stefanich?], 2007, p. 142 [↩]

- NW Moon, RL Todd, DL Morton, and E Ivey. “Findings from Research and Practice for MiddleGrades through University Education”. In: Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. STEM. Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012. url: https://hourofcode.com/files/accommodatingstudents-with-disabilities.pdf [↩]

- NW Moon, RL Todd, DL Morton, and E Ivey. “Findings from

Research and Practice for MiddleGrades through University Education”. In: Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. STEM. Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012. url: https://hourofcode.com/files/accommodating-studentswith-disabilities.pdf [↩]

- EA Slavkovsky. “Feasibility Study For Teaching Geometry and Other Topics Using Three-Dimensional Printers”. MA thesis. Harvard University, Oct. 2012. url: https://people.math.harvard.edu/~knill/3dprinter/ documents/slavkovsky_thesis.pdf [↩]

- P Maccini and JC Gagnon. Best Practices for Teaching Mathematics to Secondary Students with Special Needs. Focus on Exceptional Children 32.5 (Jan. 2000). [↩]

- L Deslauriers, LS McCarty, K Miller, K Callaghan, and G Kestin. Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116.39 (Sept. 2019), pp. 19251–19257 [↩]

- SK Carpenter, L Mickes, S Rahman, and C Fernandez. The effect of instructor fluency on students perceptions of instructors, confidence in learning, and actual learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 22.2 (June 2016), pp. 161–172 [↩]

- MA Gottfried, EL Hutt, and JJ Kirksey. New Teachers Perceptions on Being Prepared to Teach Students With Learning Disabilities: Insights From California. Journal of Learning Disabilities 52.5 (Aug. 2019), pp. 383–398 [↩] [↩]

- MA Gottfried, EL Hutt, and JJ Kirksey. New Teachers Perceptions on Being Prepared to Teach Students With Learning Disabilities: Insights From California. Journal of Learning Disabilities 52.5 (Aug. 2019), pp. 383–398 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A Brown. 3D Printing in Instructional Settings: Identifying a Curricular Hierarchy of Activities. TechTrends 59.5 (Aug. 2015), pp. 16–24 [↩]