Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of long‐term disability worldwide and is frequently associated with neuropsychiatric sequelae such as depression, apathy, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Increasing evidence suggests that the anatomical location of the stroke lesion plays a significant role in the development and severity of these mental health outcomes. In this report we provide a comprehensive review of the literature linking stroke lesion location with risk for depression, apathy, and PTSD. Multiple studies indicate that lesions in specific brain regions—particularly within the left hemisphere involving the frontal lobe, basal ganglia, and limbic‐related circuits—confer an increased risk for post‐stroke depression, with altered functional connectivity in prefrontal and limbic networks implicated in its pathogenesis. Conversely, apathy appears to be more closely associated with damage to frontal subcortical circuits and disruption of motivational networks, while emerging evidence suggests that lesion location in the right hemisphere and brainstem may predispose patients to develop PTSD following stroke. Although the overall picture is complex and affected by methodological heterogeneity, these findings underscore the importance of precise lesion mapping in predicting neuropsychiatric outcomes and informing rehabilitation strategies. The present report synthesizes data from several high‐quality clinical studies and reviews, discusses methodological limitations, and calls for further research using advanced neuroimaging techniques.

Keywords: Stroke, Lesion, PTSD, Apathy, Depression, neuroanatomy, neuroinflammation, functional connectivity, front-subcortical circuits

Introduction

Stroke is not only a major cause of physical disability but also a significant contributor to neuropsychiatric disorders that impair quality of life and functional recovery. It is estimated that up to one‐third of stroke survivors develop depression, while apathy and PTSD are also frequently encountered, each adversely affecting rehabilitation outcomes and caregiver burden1. Recent research has increasingly focused on whether the anatomical site of brain injury contributes to these post‐stroke psychiatric symptoms, with several studies suggesting that lesion location may be directly related to the incidence and severity of depression, apathy, and PTSD2. In the following sections, we review the evidence linking stroke lesion location to these mental health outcomes, examining the underlying neuroanatomical circuits and discussing potential mechanisms that mediate the observed clinical pm henomena3.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines to identify studies investigating the relationship between stroke lesion location and the development of depression, apathy, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The search encompassed four databases—PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO—covering the period from January 2010 through June 2025. The search strategy combined terms from three conceptual domains: stroke-related terms (“stroke,” “cerebrovascular accident,” “brain infarction”), anatomical location terms (“lesion location,” “infarct location,” “neuroanatomy”), and outcome-related terms (“depression,” “apathy,” “PTSD,” “post-traumatic stress disorder”). Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to link terms across domains. Filters were applied to restrict results to human studies published in English during the specified date range. In addition, gray literature and the reference lists of relevant reviews were manually searched to identify studies not captured through database queries.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they involved adult stroke survivors aged 18 or older with confirmed ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, utilized neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) to characterize lesion location, assessed at least one of the target neuropsychiatric outcomes using validated diagnostic criteria or rating scales, and reported statistical associations between lesion site and outcome. Only original research studies, including observational cohorts, case-control studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), were considered. Exclusion criteria included case reports with fewer than five participants, animal studies, non-English language publications, and any study that did not confirm lesion location using imaging.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were organized by population, study design, outcome measures, lesion assessment, and publication time frame. Studies were required to focus on adult stroke survivors, employ either observational or experimental study designs, use validated instruments for outcome assessment, confirm lesion location through imaging, and fall within the 2010–2025 publication window. Studies were excluded if they involved pediatric stroke or non-stroke populations, used case reports or reviews, lacked validated outcome measures, assessed lesion location clinically without imaging, or were published prior to 2010.

Data extraction was performed independently by one reviewer using a standardized form. Extracted information included study-level details such as authorship, publication year, country, study design, and sample size. Participant characteristics were recorded, including stroke type, time since stroke, age, and sex. Lesion information encompassed hemispheric lateralization, affected lobes or subcortical structures, imaging modality, and the analytical technique employed (e.g., voxel-based analysis, region-of-interest approach). Outcome data included the measurement tools used, time points of symptom assessment, outcome prevalence, and reported effect sizes. Key findings related to associations between lesion location and post-stroke neuropsychiatric symptoms were also captured.

Study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized controlled trials. Key domains assessed included participant selection and representativeness, stroke confirmation by imaging, adjustment for potential confounders such as age and stroke severity, the validity and blinding of outcome assessments, and clarity of statistical reporting, including confidence intervals and effect sizes. Studies exhibiting more than three critical methodological flaws were excluded from the final synthesis to maintain rigor and reliability.

Lesion Location and Post‐Stroke Depression

Stroke lesions affecting mood and motivation-related brain regions initiate a cascade of neurochemical and inflammatory responses. Microglia rapidly transition to a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1), releasing cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, which disrupt neurotransmitter systems—particularly dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate—leading to mood dysregulation. Reactive astrocytes amplify inflammation and impair glutamate reuptake, contributing to excitotoxicity. In PSD, reduced serotonergic signaling from the raphe nuclei to the prefrontal cortex diminishes emotional regulation, while in apathy, dopaminergic deficits in mesocorticolimbic pathways reduce motivation. PTSD mechanisms post-stroke may involve hyperactivity in noradrenergic systems and impaired extinction learning due to ventromedial prefrontal cortex–amygdala disconnection4.

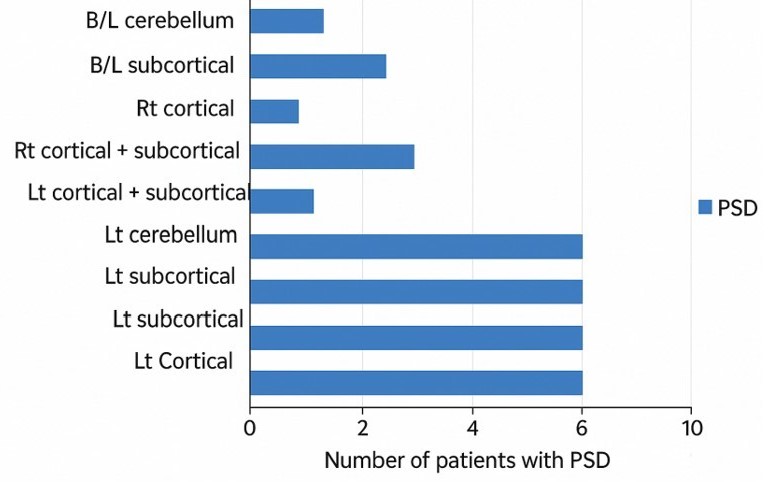

Poststroke depression (PSD) is widely recognized as one of the most common and disabling psychiatric complications following a stroke, with diverse studies linking its occurrence to disruption of specific neural circuits. Several clinical investigations have noted that lesions in the left frontal lobe, especially those affecting the prefrontal cortex and subcortical structures such as the basal ganglia, are associated with higher rates of PSD5. For example, research by Rajashekaran et al. demonstrated that left‐sided cortical and subcortical infarcts significantly increase the risk of developing depression, supporting the notion that hemispheric lateralization plays a critical role in mood regulation5. In a similar vein, studies employing voxel‐based lesion-symptom mapping have implicated the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and adjacent basal ganglia in the genesis of depressive symptoms6.

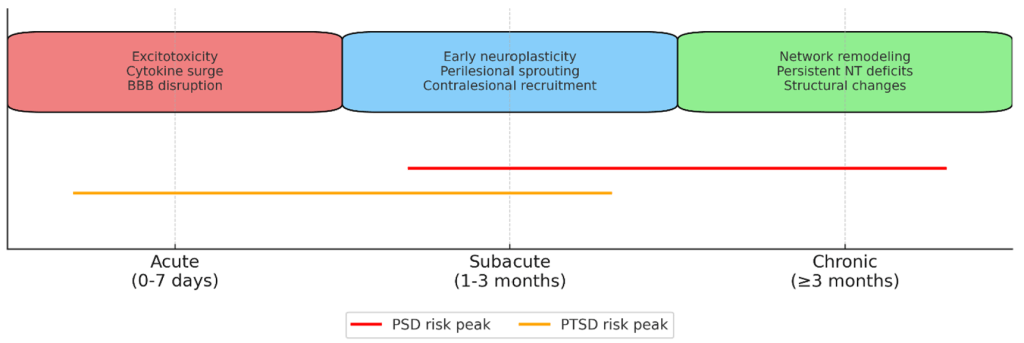

The left limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic (LCSPT) circuit has emerged as a key neural substrate underlying PSD. Terroni et al. reported that larger lesion volumes within the left LCSPT circuit, which encompasses the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, and associated subcortical regions, are robustly correlated with the incidence of major depressive episodes within months after stroke7. The timeline of PSD and PTSD development is further explored in Figure 2. This finding aligns with earlier studies that recognized the importance of disrupted prefrontal-limbic integration in mediating depressive symptoms8. Moreover, Wei et al.’s meta-analysis suggests that while both hemispheres can be involved, right hemisphere lesions may increase depressive symptomatology within the subacute phase of stroke, whereas left hemisphere damage is more consistently associated with chronic, disability-driven depression9.

Advanced neuroimaging studies have further elucidated the functional network alterations associated with PSD. For instance, functional MRI investigations have shown that stroke lesions in the frontal lobe lead to decreased degree centrality (DC) in limbic regions and dysregulation of the default mode network, both of which correlate with higher depression severity, as shown in Figure 2.

In addition, the disruption of structural connectivity within fronto-striatal circuits appears to potentiate emtional dysregulation, as demonstrated by studies utilizing diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)5. Collectively, these findings point to a convergence of evidence that focal lesions in the left frontal and subcortical regions, by impairing intricate neural networks involved in mood regulation and executive function, play a critical role in increasing the risk of post-stroke depression. The study by Metoki et al. examined the relationship between lesion locations of acute ischemic stroke and early depressive symptoms in Japanese patients. Results indicated that certain brain regions, particularly lesions in the frontal lobe and temporal lobe, were significantly associated with higher rates of probable post-stroke depression (PSD). Specifically, lesions on any side of the frontal and temporal lobes had higher odds of being linked to depressive symptoms: frontal lobe lesions had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.534 (p=0.016), and temporal lobe lesions had an adjusted odds ratio of 3.082 (p=0.003). Right-sided lesions in the frontal and temporal lobes also showed a significant association (frontal right side OR=2.709, p=0.038; temporal right side OR=3.093, p=0.018). The putamen lesion on the right side was also significantly associated with depression (OR=6.936, p=0.022). Other regions such as the parietal lobe, caudate, and anterior/posterior internal capsule did not show strong associations after adjustment. The study confirmed the prevalence of PSD at 17% using the JSS-D screening tool but noted limitations such as the absence of formal clinical diagnoses and lesion size measurements. It also pointed out that depressive symptoms were assessed at 10 days post-hospitalization, which may limit understanding of long-term psychiatric outcomes3.

Lesion Location and Post‐Stroke Apathy

Apathy, defined by a lack of motivation, diminished initiation of goal-directed behavior, and emotional indifference, is another common neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke that often overlaps with but is distinct from depression. The association between lesion location and apathy has been explored in several studies, with evidence suggesting that damage to frontal subcortical circuits is a key determinant of apathy after stroke10. Yang et al. reported that patients with frontal lobe lesions are significantly more likely to develop apathy in the acute post-stroke phase, a finding that underscores the importance of the frontal cortex in regulating motivated behavior10. Further supporting this view, Caeiro et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrating that lesions affecting regions such as the anterior thalamus, caudate nucleus, and other components of the prefrontal-subcortical circuits are associated with the development of post-stroke apathy11. These subcortical and frontal regions are integral to the neural networks that govern reward processing, decision making, and emotional regulation, and their disruption can lead to a profound reduction in motivational drive. Importantly, while depression and apathy can co-occur, apathy is characterized by a primary deficit in motivation that is not necessarily accompanied by dysphoria or feelings of sadness typical of depressive episodes.

Neuroimaging studies have provided additional insights by revealing that stroke-related damage in medial prefrontal regions, particularly those involved in the appraisal of reward and effort, is associated with deficits in motivational behavior12. Moreover, alterations in regional cerebral blood flow and metabolic activity within these networks have been linked to higher levels of apathetic symptomatology13. As such, the body of evidence converges to suggest that the integrity of frontal-subcortical and limbic circuits is critical for maintaining normal motivational states, and that lesions within these areas markedly increase the risk of post-stroke apathy10.

Lesion Location and Post‐Stroke Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder

Although research on post-stroke PTSD is not as extensive as the literature on depression and apathy, emerging findings indicate that the anatomical site of a stroke lesion may also influence the risk of developing PTSD. In the context of stroke, PTSD is characterized by persistent re-experiencing of the traumatic event, heightened anxiety, and avoidance behaviors that may further complicate recovery. Notably, Rutovic et al. reported that lesions localized in the right hemisphere and brainstem are associated with an increased prevalence of PTSD symptoms among stroke survivors, with higher levels of disability correlating with greater PTSD severity14. The mechanistic underpinnings of post-stroke PTSD may differ from those of depression and apathy. For example, some neuroimaging studies in trauma-exposed populations have found that lesions in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex or amygdala—regions that are integrally involved in the regulation of emotional responses and fear extinction—can modulate the intensity of PTSD symptoms. However, in stroke patients, the relationship is less straightforward. Some investigations have suggested that damage to these regions might actually reduce PTSD symptoms by attenuating the neural circuits necessary for the persistent re-experiencing of trauma. Yet, other studies point to a scenario in which the overall level of disability associated with right hemispheric, or brainstem strokes acts as a driving force for the development of PTSD, independent of the specific neural substrate of emotion regulation15.

The heterogeneity of findings in the PTSD literature likely reflects differences in study design, patient selection, and the operationalization of PTSD in post-stroke populations. Despite these challenges, the preliminary evidence supports the hypothesis that lesion location is a relevant modulator o1f post-stroke PTSD risk, with right sided and brainstem lesions emerging as potential risk factors14. In summary, while the evidence for lesion location–PTSD associations is still evolving, current studies indicate that damage to certain brain regions may predispose stroke survivors to develop PTSD, thereby compounding the overall burden of neuropsychiatric complications.

Discussion

| Brain Region | Physiological Role | Molecular/Cellular Changes Post-Stroke | Psychiatric Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) | Executive function, mood regulation via prefrontal-limbic control | ↓ Serotonin, ↓ Dopamine; disrupted fronto-limbic connectivity; ↑ IL-1β, TNF-α | PSD |

| Basal ganglia | Motivation, motor control, reward processing | ↓ Dopamine in mesocorticolimbic pathway; altered glutamate signaling | PSD, Apathy |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | Conflict monitoring, emotional regulation | Impaired serotonergic modulation; microglial activation | PSD |

| Medial prefrontal cortex | Reward valuation, goal-directed behavior | ↓ Dopamine; astrocytic glutamate dysregulation | Apathy |

| Amygdala | Fear processing, emotional memory | Hyperactive noradrenergic signaling; reduced prefrontal inhibition | PTSD |

| Hippocampus | Contextual memory, stress regulation | ↓ BDNF; impaired neurogenesis; ↑ glucocorticoid activity | PTSD, PSD |

Beyond isolated lesion sites, post-stroke psychiatric outcomes arise from network-level disruptions. Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling demonstrates that altered connectivity within the default mode network (DMN), salience network (SN), and limbic circuits predicts PTSD trajectories16. Lesion-network mapping reveals that lesions causing similar symptoms, even in different anatomical locations, are part of the same functional network17. This suggests that psychiatric sequelae may be better predicted by disrupted network nodes than by lesion coordinates alone.

Psychiatric outcomes post-stroke are influenced by lesion timing. Acute phases are dominated by excitotoxicity and inflammation; subacute phases involve initial neuroplastic changes; chronic phases reflect long-term network reorganization, which can be adaptive or maladaptive. Mechanisms such as perilesional reorganization, contralesional activation, and diaschisis play a pivotal role in recovery or symptom persistence18. Therapeutic Implications: Lesion-specific rehabilitation strategies, including rTMS targeting left DLPFC for PSD and PTSD can be optimized using lesion-network data19. Incorporating such insights into clinical decision-making could refine patient stratification and improve functional and psychiatric outcomes.

The accumulated evidence reviewed in the preceding sections provides a nuanced picture of how stroke lesion location can influence the risk and profile of subsequent mental health outcomes. For post-stroke depression, convergent data indicate that focal lesions in the left frontal lobe, particularly within the prefrontal cortex and associated subcortical structures, are consistently associated with an increased risk of developing depressive symptoms7. The LCSPT circuit, which encompasses key structures such as the anterior cingulate cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and subcortical relay nuclei, has emerged as a central substrate underlying the pathophysiology of PSD7’8. Disruptions within this network appear to compromise the regulation of mood and emotion, thereby predisposing patients to depressive episodes even in the absence of severe neurological deficits. At the neurochemical level, alterations in biogenic amine neurotransmission following focal lesions are thought to contribute to the onset of PSD, further supporting the lesion location hypothesis. The article by Metoki et al. cited literature that linked PSD and apathy with lesion locations mainly in frontal and temporal lobes, supporting the notion that specific stroke lesion sites increase risk for depressive symptoms. The study did not specifically address PTSD outcomes but noted the relevance of early detection and treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with lesions in these regions3. Overall, the findings implicate the frontal and temporal lobes, especially on the right side, and the right putamen as lesion locations that increase the risk of post-stroke depression and likely related conditions such as apathy.

In contrast, post-stroke apathy appears to be more specifically linked to disruptions in circuits that govern motivation and goal-directed behavior. Studies have shown that lesions in the frontal lobe—and particularly in regions subserving executive control and the evaluation of reward are associated with higher rates of apathy10. The dissociation between depression and apathy is highlighted by their differential response to lesion location: whereas depression may be driven by disruptions in mood-related circuits, apathy is more closely related to impairments in the neural networks responsible for initiating and sustaining motivated behavior10’11. This distinction is clinically important because, although the two conditions often co-occur, they require different therapeutic approaches. Whereas antidepressant medications may ameliorate depressive symptoms, apathy might be more responsive to interventions that target dopaminergic transmission and improve frontal-subcortical connectivity.

Post-stroke PTSD, while less extensively studied, presents an additional layer of complexity. Evidence suggests that lesions in the right hemisphere and brainstem contribute to a higher risk of PTSD symptoms, possibly due to their impact on the neural circuitry involved in fear processing and stress regulation14. The contradictory findings regarding lesions in limbic regions such as the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex for instance, observations that damage in these areas may paradoxically reduce PTSD symptoms underscore the need for a more refined understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of PTSD in stroke. One plausible explanation for these discrepancies is that the overall burden of neurological disability, rather than the lesion location per se, may drive psychological vulnerability to PTSD; patients with extensive right hemispheric or brainstem damage may experience more severe functional impairments that, in turn, predispose them to PTSD15.

Notably, methodological differences among studies also contribute to the variability in reported findings. Variations in imaging modalities (e.g., CT versus MRI), differences in the timing of neuropsychiatric assessments, and heterogeneity in patient populations (including differences in stroke severity, lesion size, and pre-stroke mental health status) all complicate direct comparisons across studies9’20. For instance, some studies have excluded patients with severe aphasia or cognitive impairment, potentially biasing the sample toward those with more circumscribed lesions, while others have employed voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping methods that allow for a more precise delineation of affected circuits, albeit in relatively small cohorts21. Moreover, the temporal evolution of neuropsychiatric symptoms, particularly the transient versus chronic nature of depressive symptoms, adds another layer of complexity to establishing clear-cut lesion-behavior correlations8.

Despite these methodological challenges, the overall trend remains that lesion location is a clinically relevant factor in determining mental health outcomes after stroke. The integration of structural imaging with functional modalities (e.g., functional MRI and DTI) is beginning to unveil the network-level disruptions that underlie post-stroke psychiatric conditions, moving beyond the simplistic notion of “lesion side” toward a more nuanced understanding of circuit-based dysfunction21. As clinical trials continue to explore the neural substrates of motivational disorders using innovative neuropsychological tools and lesion mapping12’22’23. It is likely that the predictive value of lesion location will be further clarified, ultimately leading to more targeted and individualized therapeutic interventions.

Conclusion

In summary, a growing body of evidence indicates that stroke lesion location is a key determinant of subsequent mental health outcomes, including depression, apathy, and PTSD. Focal lesions in the left frontal lobe and associated subcortical structures—particularly those involving the limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic circuit—are strongly linked to the development of post-stroke depression, likely through the disruption of networks critical for mood regulation and emotional processing7. Meanwhile, post-stroke apathy appears primarily related to damage in frontal circuits that underlie motivation and executive function, with evidence pointing to the role of both cortical and subcortical components in mediating this syndrome10’11. Although the literature on post-stroke PTSD is comparatively limited, preliminary data suggest that lesions in the right hemisphere and brainstem may increase PTSD risk, potentially through mechanisms linked to impaired fear regulation and heightened disability14.

Overall, while considerable progress has been made in correlating lesion location with post-stroke psychiatric outcomes, significant heterogeneity remains among studies due to methodological variations and differences in patient characteristics. Future research employing large-scale, multimodal neuroimaging studies and longitudinal designs is essential to further elucidate the complex interplay between lesion site, network disruption, and neuropsychiatric sequelae. Such studies will not only enhance our understanding of stroke pathophysiology but may also inform the development of targeted rehabilitation protocols aimed at mitigating the adverse mental health consequences of stroke.

In conclusion, the current evidence supports a model wherein specific stroke lesion locations contribute differentially to the risk of depression, apathy, and PTSD by disrupting distinct but overlapping neural circuits. This knowledge has important clinical implications for early identification, risk stratification, and the design of personalized interventions that address the multifaceted challenges of post-stroke recovery1’24. As future studies refine our understanding of these lesion-behavior relationships, clinicians will be better equipped to integrate neuroimaging findings with clinical assessments in order to optimize outcomes for stroke survivors.

References

- Duncan, K. Rose, and Sophia Sundararajan. “Neuropsychiatric symptoms after stroke: Accurate identification is vital to optimizing recovery and quality of life.” Current Psychiatry 21.9 (2022). [↩] [↩]

- Garton, A. L. A., Sisti, J. A., Gupta, V. P., Christophe, B. R., & Connolly, E. S. Jr. (2017). Poststroke post‑traumatic stress disorder: A review. Stroke, 48(2), 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015234 [↩]

- Metoki, N., Sugawara, N., Hagii, J. et al. Relationship between the lesion location of acute ischemic stroke and early depressive symptoms in Japanese patients. Ann Gen Psychiatry 15, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-016-0099-x [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Lu, Y., & Wen, Q., Neuroinflammation and Post-Stroke Depression: Focus on the Microglia and Astrocytes. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12–34 (2025). [↩] [↩]

- Rajashekaran, P., Pai, K., Thunga, R., & Unnikrishnan, B. (2013). Post-stroke depression and lesion location: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(4), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.120546 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Nickel, A., & Thomalla, G. (2017). Post-stroke depression: Impact of lesion location and methodological limitations—A topical review. Frontiers in Neurology, 8, 498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00498 [↩]

- Terroni, L., Amaro, E., Iosifescu, D. V., Tinone, G., Sato, J. R., Leite, C. C., … Fráguas, R. (2011). Stroke lesion in cortical neural circuits and post-stroke incidence of major depressive episode: A 4-month prospective study. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 12(7), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2011.562242 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Robinson, R. G., & Jorge, R. E. (2016). Post-stroke depression: A review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(3), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Wei, N., Yong, W., Li, X. et al. Post-stroke depression and lesion location: a systematic review. J Neurol 262, 81–90 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7534-1 [↩] [↩]

- Yang, Sr., Hua, P., Shang, Xy. et al. Predictors of early post ischemic stroke apathy and depression: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 13, 164 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-164 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Caeiro, L., Ferro, J. M., & Costa, J. (2013). Apathy secondary to stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 35(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346076 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale. (2025, February 20). Characterizing the neural bases of motivational disorders after stroke (MOTI-stroke) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03741140). ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03741140 [↩] [↩]

- Sachdev, P. S. (2018). Post-stroke cognitive impairment, depression and apathy: Untangling the relationship. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(3), 301–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.013 [↩]

- Rutovic, S., Kadojic, D., Dikanovic, M. et al. Prevalence and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder after ischaemic stroke. Acta Neurol Belg 121, 437–442 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-019-01200-9 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jiang, C., Li, Z., Du, C., Zhang, X., Chen, Z., Luo, G., Wu, X., Wang, J., Cai, Y., Zhao, G., & Bai, H. (2022). Supportive psychological therapy can effectively treat post-stroke post-traumatic stress disorder at the early stage. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, Article 1007571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1007571 [↩] [↩]

- Zion, N., et al., Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling of PTSD Development Among Recent Trauma Survivors. JAMA Network Open, 8, 1–14 (2025). [↩] [↩]

- Nabizadeh, S., & Aarabi, M., Functional and Structural Lesion Network Mapping in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 14, 112–130 (2023). [↩]

- Rüdiger, J., et al., The Role of Diaschisis in Stroke Recovery. Stroke, 30, 1844–1850 (1999). [↩]

- Berlim, M. T., et al., Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Over the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Treating Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Exploratory Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Double-Blind and Sham-Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75, 1019–1024 (2014). [↩]

- Ilut, S., Stan, A., Blesneag, A., Vacaras, V., Vesa, S., & Fodoreanu, L. (2017). Factors that influence the severity of post-stroke depresssion. Journal of medicine and life, 10(3), 167–171. [↩]

- Shi, Y., Zeng, Y., Wu, L. et al. A Study of the Brain Functional Network of Post-Stroke Depression in Three Different Lesion Locations. Sci Rep 7, 14795 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14675-4 [↩] [↩]

- Smania, N. (Principal Investigator). (2022, May). Post-stroke Recovery (PSR_e2020) (NCT04323501) ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04323501 [↩]

- Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel. (2024). DEliriuM in STroke: the Link Between Stroke, Delirium and Long-term Cognitive Impairment (DE-MIST) (NCT06650436) ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06650436 [↩]

- Jing Zhou , Yijia Fangma , Zhong Chen , Yanrong Zheng. Post-Stroke Neuropsychiatric Complications: Types, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Intervention. Aging and disease. 2023, 14(6): 2127-2152 https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2023.0310-2 Brodaty, H., Liu, Z., Withall, A., & Sachdev, P. S. (2013). The longitudinal course of post-stroke apathy over five years. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 25(4), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12040080 [↩]