Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are neurological disorders classified by the progressive loss of selectively vulnerable neuron populations and are the leading cause of physical and cognitive disability. Planaria is a genus of flatworms famous for biological immortality and their extraordinary regenerative capacities, and surprisingly developed nervous system. Yerba Mate is a herbal infusion beverage native to Southern South American countries. This study aims to provide a proof of concept for the potential of Yerba Mate in treating neurodegenerative diseases. 1.0% Ethanol was used to induce neurodegeneration. The planaria were separated into four groups of 10: Control (CO), Ethanol only (EO), Yerba Mate only (YM), and Ethanol and Yerba Mate (EY). Center of Mass (COM) tracking was used to analyze planarian motility as it has been linked to planarian CNS integrity. The means the COM results in pixels(p) were YM: 9357.58p, CO: 6526.76p, EY: 4223.57p, and EO: 1650.68p. To determine statistical significance, a One-Way ANOVA followed by a Tukey-HSD Test with an alpha value of 0.05 was used. The p-value for the difference between the Yerba Mate and Ethanol group and Ethanol only group was 0.002, indicating a significantly higher CNS integrity for the EY group. Further research should be conducted to determine whether Yerba Mate’s neuroprotective or regenerative properties were responsible for this result. Although these conclusions still do not have any clinical application they demonstrate the potential for Yerba Mate in treating neurodegenerative diseases and as such warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Neurodegenerative Disease, Planaria, Yerba Mate, Ethanol

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are the leading cause of physical and cognitive disability, with about 15% of the population currently affected by Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)1. Neurodegenerative diseases are neurological disorders classified by the progressive loss of selectively vulnerable neuron populations2. These diseases are severely debilitating and can cause memory loss, loss of motor function, and speech disability. As such, there is a large incentive to develop treatments and preemptive therapies, especially as reported cases of these diseases are expected to grow.

This paper does not aim to develop a treatment for these diseases, however, it does highlight a potential subject of study in advancing treatment research. This study serves as a proof of concept for the potential use of Yerba Mate (Ilex Paraguariensis) in the treatment or prevention of these neurological disorders. Yerba Mate is a drink common in South America, commonly hailed for its reported health benefits. Recent research has conjured evidence to support this notion, especially as daily mate consumption has been correlated with lowered rates of PD3.

To serve as a proof of concept, this study must be as simple as possible; as such, the biological subject for this study was Planaria. Planaria is a genus of flatworms commonly used in toxicology and stem cell research due to their developed Central Nervous System (CNS) and vast amount of pluripotent cells in adults. Due to the presence of these stem cells, this study also investigates the potential of stem cells to be used in treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. This is merely a consequential analysis, not the primary experiment. In order to induce the effects of neurodegenerative disease, the Planaria will be exposed to 1.0% EtOH. This study aims to identify the effects of these compounds by recording the average distance moved and average velocity of the Planaria through a process known as Center of Mass (COM) Tracking; then applying it to four groups, Control (CO), Ethanol Only (EO), Yerba Mate Only (YM), and Yerba Mate and Ethanol (EY). COM tracking has been used to study the effects of Various Compounds on Planarian behavior and locomotion effectively acting as a proxy for CNS integrity.

For this study, the Null Hypothesis (![]() ) states there would be no statistically significant difference between the Ethanol Only group and the Yerba Mate and Ethanol Group, that is to say

) states there would be no statistically significant difference between the Ethanol Only group and the Yerba Mate and Ethanol Group, that is to say ![]() . The alternative hypothesis

. The alternative hypothesis ![]() states that planaria in the EY group had a higher average distance than those in EO:

states that planaria in the EY group had a higher average distance than those in EO: ![]() . The same principle applies to the average velocity of the Planaria:

. The same principle applies to the average velocity of the Planaria: ![]() and

and ![]() . Although this paper is unable to draw a conclusion as to the exact mechanisms by which Yerba Mate may prove beneficial against Ethanol, it is likely Yerba Mate may increase the rate of neuroregeneration thereby decreasing the toxic effects of ethanol. Some chemical components of Yerba mate may also react synergistically with the Ethanol and neutralize the toxin rather than increase the regeneration of neural cells. Due to the fact that Yerba Mate is a known antioxidant the Yerba Mate likely reduced the oxidative stress generated by the Ethanol, thus decreasing its long term negative effects4. This study, however, is unable to determine what chemical or biochemical effect the Yerba Mate has on the ethanol or planaria and further research should be done to elucidate these effects.

. Although this paper is unable to draw a conclusion as to the exact mechanisms by which Yerba Mate may prove beneficial against Ethanol, it is likely Yerba Mate may increase the rate of neuroregeneration thereby decreasing the toxic effects of ethanol. Some chemical components of Yerba mate may also react synergistically with the Ethanol and neutralize the toxin rather than increase the regeneration of neural cells. Due to the fact that Yerba Mate is a known antioxidant the Yerba Mate likely reduced the oxidative stress generated by the Ethanol, thus decreasing its long term negative effects4. This study, however, is unable to determine what chemical or biochemical effect the Yerba Mate has on the ethanol or planaria and further research should be done to elucidate these effects.

Literature Review

Planaria is a genus of flatworms famous for biological immortality and their extraordinary regenerative capacities, even being able to regenerate entire bodies from minute remnants5. This regenerative capacity is due to the high concentration of neoblasts, pluripotent cells capable of differentiating into any cell type, in adults6. Planaria also contain a surprisingly developed nervous system, illustrated in Figure 1, consisting of two parallel nerve chords down the length of the worm, connected through parallel, branching nerves through the central line of the worm. The nerve chords originate from an equally complex Central Nervous System, a two-lobed brain that has been shown to retain memories even after complete regeneration7. This complex nervous system allows for the study of how toxins affect the nervous system of different animals and the extent to which those nervous systems are affected. When combined with its innate regenerative capacities, planaria become ideal models for pharmacological, neurotoxicological, and teratological studies, as they provide an in vivo model for neuroregeneration, something not present in most other animals8,9,10,11 This in vivo model for neuroregeneration allows us to observe how the effects of a toxin, in this case ethanol, are counteracted by a regenerating nervous system. It also allows us to observe the effect, if any, of Yerba Mate’s on the regenerative properties in in vivo neoblasts. While it is not a vertebrae, a planarian’s simple yet nervous system combined with its regenerative abilities are ideal for studying the combined effects of a known neurotoxin with a strong antioxidant.

Yerba Mate is a herbal infusion beverage native to Southern South American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay), becoming increasingly popular in the United States12. Traditionally, it is an infusion of dried Mate leaves, usually from Ilex Paraguariensis, and drunk out of a dried gourd using a metal filtering straw called a “bombilla”. An example of the leaves, gourd, and filtered straw are seen in Figure 2. Mate leaves can be prepared in several different ways, the most common method is toasting to minimize the amount of toxic smoke absorbed in the leaves13. The drink itself also varies depending on the country or region. In Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, Mate or Chimarrão is prepared by pouring the dried leaves into a gourd called a matero and then pouring hot water, 60-80°C, over the leaves. After the drink is consumed, the water can be repoured between six to seven times13. Another common method, mate cocido, is to place the mate leaves into a tea bag and prepare it as you would a tea. In Paraguay, mate is usually consumed as terere, prepared using cold water, and usually served with lemon or some other citrus. Due to its popularity in South American countries and increasing popularity in the U.S., research into the stimulant and health effects of mate has grown in recent years.

In South American countries, mate is frequently hailed for its numerous health benefits, however, recent studies have highlighted potential safety concerns12. Recent studies have highlighted the correlation between high consumption of Yerba Mate and increased risk of Oral, Esophageal, and Bladder Cancer, probably due to the consumption temperature12,14. Other studies have shown that Yerba Mate’s high concentrations of Saponins, antioxidants, and other Phenolithic compounds can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and even kill cancer cells by inhibiting Topoisomerase II or inducing apoptosis4,15,16.

Despite its high level of Caffeine, the literature indicated Mate is cardioprotective due to its hypocholesterolemic properties and other Methylxanthines; furthermore, the concentration of Caffeine does not significantly impact regeneration in planaria12,17. Mate has also been shown to have significant neuroprotective effects, especially in association with Dopaminergic Neurons and Parkinson’s Disease3,18. These neuroprotective properties are of research interest as Yerba Mate consumption has been correlated with lower rates of Parkinson’s Disease in South American countries, advancing research for a potential cure3.

These properties, along with their increased regeneration, are of special interest as they provide a logical basis for Yerba Mate’s capacity to reduce the neurodegenerative effects of Ethanol exposure in planaria. Due to the lack of research on the potential toxic effects of Yerba Mate the concentration of Yerba Mate in this study was chosen arbitrarily to be 1.0% of a “traditional brew”, the procedure for which is described in the methodology. The 1.0% concentration also allowed easy observation of the Planaria as the medium water was not cloudy. Due to the high concentration of Methylxanthines in Yerba Mate a low concentration was chosen to minimize the risk of Planaria death from Methylxanthine poisoning. Further research should be done with different concentrations of Yerba Mate to discover its toxicity and the potential variation in effects due to different concentrations.

Unlike Yerba Mate, the effects of Ethanol and other neurotoxins are present in the literature, as such Ethanol was used to induce neurodegenerative symptomatology in this study. Ethanol (EtOH) is the most common psychoactive and recreational drug commonly consumed by humans and has become part of our culture and laws19. Despite this, EtOH can severely affect the mature and developing Central Nervous System (CNS), classifying it as a teratogen. Exposure often causes retardation in Planaria head regeneration, function acquisition, and, in extreme cases, complete head regression, especially when exposure occurs during the first 36-120 hours after amputation10,20. These teratogenic effects have been recorded in high concentrations (>5.0%) for short periods, and low-concentration (<1.0%) for long-term exposure. Long-term exposure is defined as 20-30 days21. Short term incubation of Planaria in a 1% v/v EtOH solution impaired gliding locomotion and induced a muscle based gait in the planaria22. Further, incubating the planaria in 3.0% v/v EtOH solution induces Paralysis over the course of an hour. Exposure to ethanol also slows regeneration in Planaria23. A similar effect was observed in another study where Ethanol delayed the reacquisition of negative phototaxic behavior in regenerating Planaria24. In sufficient concentrations Planaria also exhibit various morphological and behavioral changes such as head regression, regression of photoreceptors, contraction, screw-like movement, gut-sliding, and assuming a C-shape25. These studies show Ethanol has a negative effect on a Planaria’s CNS. However, the literature lacks research on concentrations in that range, especially long-term exposure to 1.0% EtOH, a concentration comparable to “physiologically relevant” blood alcohol concentrations (BAC)20. While it is true that equating the BAC of humans to the medium concentration of Planaria is unsound it demonstrates that 1.0% EtOH concentration, while not acutely toxic, has pronounced physiological effects on Planaria making it a study-worthy concentration. This gap in the neurological effects of long-term exposure to 1.0% EtOH is so significant that Colsoul concludes with a call for research on those effects.

Since Ilex Paraguariensis may be neuroprotective and can increase the regeneration of damaged cells, its interaction with degenerative neurotoxins should be investigated. This synergism between the neuroprotective effects of Ilex Paraguariensis and the neurotoxic properties of EtOH is completely absent from the literature. The potential for Ilex Paraguariensis to counteract neurodegenerative compounds may be extrapolated into neurodegenerative diseases with further research. As such it is necessary to investigate this potential for the advancement of potential treatment research.

Methodology

Overview and Ethics

This study is a true experiment as it aimed to establish causality between ethanol, Yerba Mate, and neurodegeneration. This study complies with standard ethical practices and treatment of animals and was approved by my school’s IRB.

Culture and Maintenance

As mentioned before Planaria were chosen for this study as the literature indicates that Planaria are excellent model organisms for in vivo behavioral, neurotoxicology, and tetralogy studies due to their capacity to regenerate almost all cell types through neoblasts26,11. The Planaria’s Central Nervous System (CNS) also possesses many similarities to the human CNS, providing an excellent model for in vivo neuroregeneration studies22. The subspecies Dugesia Tigrina was chosen for this study due to its availability and vast presence in the literature10,25. The individuals were ordered from Carolina Biological Supply, Brown Planaria Living.

The planaria were cultured for approximately three months before the start of the experiment. They were maintained in darkness inside 8” culture plates bought from Carolina Biological Supply and in spring water bought from Poland Spring or Zephyrhills per Carolina Biological Supply’s Planaria Care Guide27. During the culturing period, they were fed once a week with boiled egg yolks and, sparingly, boiled egg whites28. The medium was also changed approximately twice a week unless there was visible debris, in which case it was changed immediately. The Planaria were starved for a week before beginning the experiment to reset their metabolic processes in order to reset their metabolisms and to conform with previous research practices25.

Materials

Ethanol was bought from Amazon, DA Ethyl alcohol 95%, and diluted to 1.0% in Zephyrhills spring water. Yerba Mate was bought from Publix under the brand name Cruz de Malta, as it is very popular and widely consumed and available. This brand of mate contains no additives and is roasted not smoked, decreasing the concentration of potentially toxic PAHs12. It is possible that Yerba Mate leaves prepared by different methods such as smoking will have different physiological effects on the planaria. While this study does not investigate those differences, future research should focus on the different concentrations of PAHs and other compounds found in different Yerba Mate preparations and their corresponding effects on Planaria.

Experimental Setup:

The planaria were separated into four groups, each containing 10 planaria: Control (CO), Ethanol only (EO), Yerba Mate only (YM), and Ethanol and Yerba Mate (EY). The groups were identical save the addition of compounds to the medium.

The medium for CO was 380ml of Zephyrhills Spring water. For EO, the medium was prepared by adding 4 ml of 95% Ethanol (EtOH) to 376 ml of spring water. This concentration was chosen as it is comparative to “physiologically relevant” concentrations of blood alcohol in humans and has not been studied in planaria for long-term exposure (1 week or more)20.

Due to the variety of Yerba Mate types and brewing methods, and the regional and individual variations within those methods there is no “ideal” method for the brewing of Yerba Mate. Therefore the brewing method used is based on the author’s familial experience with Mate but does not in any way represent the vast array of regional and individual differences in Yerba Mate brews. The YM medium was prepared by brewing 500ml mate cocido in the traditional method as follows. 500ml of water was placed in a beater and heated to 100 °C on a hot plate, the water was then removed from the hot plate and 20ml (11 grams) of Cruz de Malta brand Yerba Mate was placed in a stainless steel tea strainer of 3.81 cm diameter (1.5 inches), the tea strainer was shaken over a sink repeatedly until no fine powder was observed falling from the strainer. The strainer with Yerba Mate was placed in the hot water. The mate leaves were allowed to steep for up to 5. The water temperature was then allowed to drop to 22 °C as extreme water temperature would have caused severe damage and potentially killed the Planaria28. The brewing method, mate cocido, was chosen to minimize the amount of physical debris in the medium. While not the traditional method, mate cocido produces a drink similar to traditional brewing methods and is still widely consumed13. Once the mate cocido was prepared, 3.8ml of the drink was added to 376.2ml of Zephyrhills Spring water and added to a culture dish to serve as the medium. The medium for the EY group was prepared in the same way as above and 3.8 ml of YM was combined with 4.0 ml of EtOH before being added to 372.2 ml of spring water, resulting in 380 ml of medium with a 1.0% concentration of both Yerba Mate and EtOH. As mentioned, the Planaria were starved for a week before beginning the experiment25. After each medium was poured into a new and clean 8” glass petri dish ten Planaria were placed in each dish.

The planaria were fed once a week on the fourth day of every week, after data was recorded that day, with egg yolk and egg whites in a small petri dish containing 20 ml of their medium. During their feeding, their culture dishes were washed, and the medium was replaced.

COM Tracking

This study aims to establish a causal relationship between the presence of Yerba Mate and increased CNS integrity in Planaria exposed to 1.0% Ethanol. As such a method is needed to provide a measurement of CNS integrity. Behavioral assays such as those used by Hagstrom et al. were considered but ultimately discarded due to timing constraints and the lack of a strong connection to CNS integrity. Rather, the method chosen is a variation on Planarian Locomotor Velocity (pLMV) method. The pLMV method has long been used to determine toxicity and the impact of toxins on the Planarian CNS10. The COM tracking system is an improvement on this pLMV system which allows for more accurate analysis of planarian locomotion, velocity and behavior29. The pLMV system has been used to study the effects of stimulants like methylxanthines on planarian locomotion and behavior30. Planaria locomotion has been linked to the integrity of Planaria brain and CNS31. This link between COM tracking and locomotion and COM tracking and CNS integrity implies the use of COM tracking as a proxy for CNS integrity. COM tracking was then further developed by Liu and Ella 2024, whose Automated Video monitoring system accurately quantized the effects of neurotoxins on planaria acting as a proxy for CNS integrity32. This system provides a quantitative link between the movement and the neurotoxic effects of the medium, thus providing a proxy of CNS integrity in the planaria.

This study does not attempt to classify and analyze broader aspects of Planarian behavior, nor does it analyze alternative effects the toxin may have had on the planarian metabolism. As the planaria were recorded individually an analysis of possible group behaviors exhibited by planaria exposed to Yerba Mate and Ethanol is impossible. This could be addressed in future studies by the implementation of a COM system capable of handling multiple planaria (something not easily feasible with this implementation). Future studies can also combine this COM system with various behavioral assays, such as those by Hagstrom et al in order to create a complete picture of the effect of these toxins on Planarian behavior.

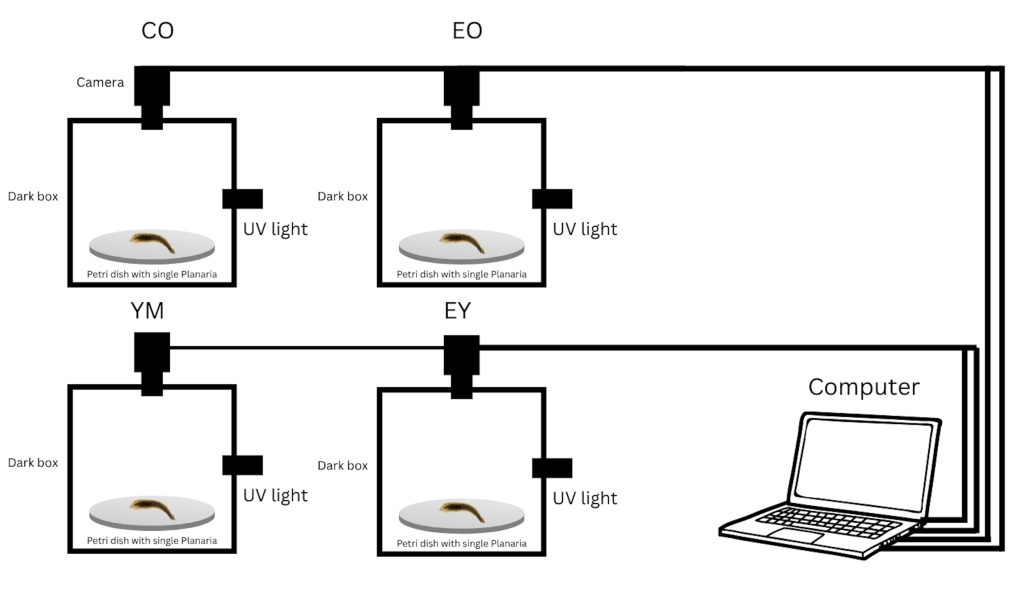

The experimental setup for the COM tracking system was similar to that of Liu and Ella and can be seen in Figure 3. A singular planaria was placed in a petri dish containing its own medium and then placed under a box in total darkness. The inside of the box was then illuminated with an Ultraviolet light and the planaria were recorded four at a time using four Trausi HD webcams connected via USB hub to a laptop running a custom python script found in Appendix B.2.

Data Collection

The neurotoxic effects of the experimental mediums on the Planaria were measured by assessing the motility of the planaria on a near-daily basis10,22,33. Due to the ease of data collection, data organization, statistical analysis, and the nature of the experiment, Center of Mass (COM) tracking was chosen to analyze planarian motility over qualitative methods, such as those described by Hagstrom et al. or Wu and Li. Furthermore, COM was used over other quantitative methods, such as pLMV, due to its rapid data collection and increased accuracy33.

Data collection began 24 hours after the planaria were introduced into their mediums to allow them to acclimate to their new environment and allow the experimental mediums to take effect. The implementation of COM tracking was very similar to those described by Talbot and Schotz, with the setup slightly adapted due to financial and time constraints. The Planaria’s motility was analyzed five days a week for four weeks, resulting in 21 days for each worm. Each Planaria was removed from its culture and placed into an individual glass petri dish containing its respective medium in a dark box illuminated with a UV light32. This setup is summarized in Figure 3. Glass was used as it is easy to clean and commonly used in the literature, once the planaria was placed in the dish it was given a 30 seconds to acclimate before beginning the trial as all planaria exhibited a spike in activity after exiting the transfer pipette. The trial consisted of recording the individual for five minutes at 5 frames per second and running the recording through a COM program written by Liu and Ella in Python and OpenCV, which traces Planaria’s path and returns the total distance and average velocity32.A custom Python script was written to cycle over every saved video file (total of 820), run the COM algorithm, and then export the values to a .csv file. Once data collection was finished, the script was executed, and the data was compiled into the aforementioned .csv file.

Results

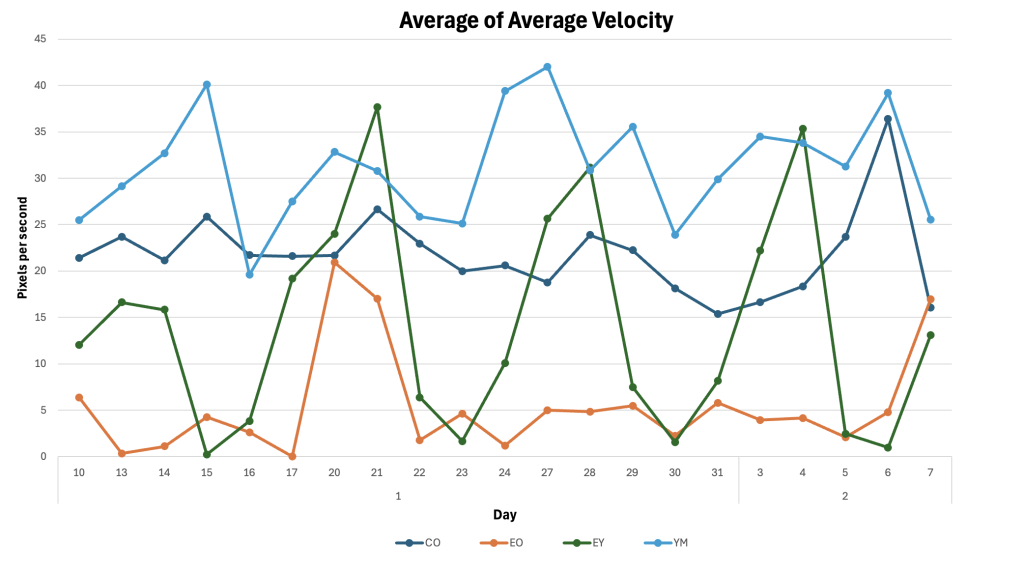

During the recording phase, the planaria were also monitored qualitatively. Although mortality was not recorded none was observed as 10 planaria were present in each group throughout the study even in groups with no reproduction. In groups that did exhibit budding (CO, YM, and EY) the buds were easy to identify and remove, ensuring the original 10 planaria remained throughout the entire experiment. This lack of mortality indicated that the concentration of YM used is safe for study with Planaria and the concentration of EtOH was not lethal over the observed time period of 21 days. Although they were never recorded, casual observation seemed to indicate the YM group produced the largest number of offspring, followed by CO and then by EY. No reproduction was observed in EO. After the planaria were recorded, they were processed with the programs shown in Appendix B. The process lasted about five hours, and the data, shown in Appendix C, was transferred from the CSV file to an Excel workbook for data analysis. Twenty-five outliers were detected and removed from the data set. Outliers were observed by graphing the data for each group individually, if a sudden large spike was detected which did not seem to fit the surrounding data the corresponding video was analyzed manually. If the data gathered by the video was inaccurate (due to a bug in the program), that data point was removed. This same analysis was done for every zero value, if the data was inaccurate then the data point was removed. All planaria were confirmed dead/alive both before and after the recording by the brief moment of activity observed after the planaria exited the pipette but before recording began. The total distances, in pixels, and average velocities, in pixels per second, for every day were averaged together and plotted on a line graph seen in Figure 4.

From these figures, it is evident that the worms exposed to Yerba Mate (YM group) moved the most, even more than the control. This is most likely due to the high level of Caffeine and other methylxanthines present in the Yerba Mate12. It is also apparent that the Planaria exposed only to Ethanol (EO group) moved the least, consistent with previous research in the literature. These two conclusions are supported by the means of the groups; YM had a mean of 9357.58 pixels(p) while EO had a mean of 1650.68p; CO was the second highest with a mean of 6526.76p, and EY was third with a mean of 4223.57p. This difference in means indicates that Yerba Mate was possibly neuroprotective, decreasing the negative impact of EtOH as a neurotoxin.

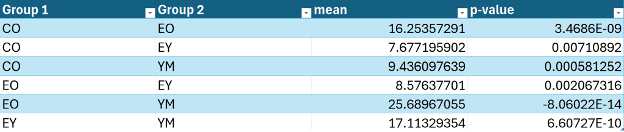

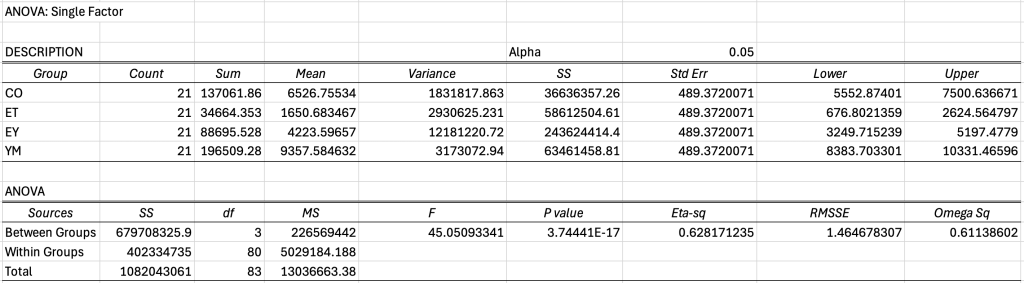

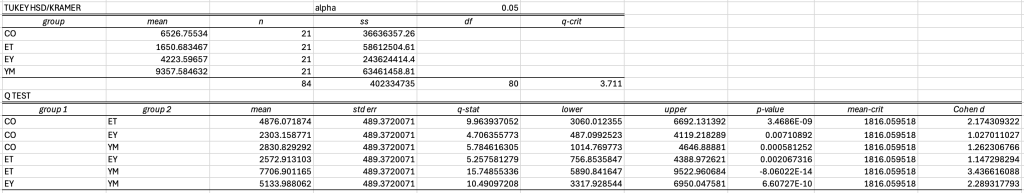

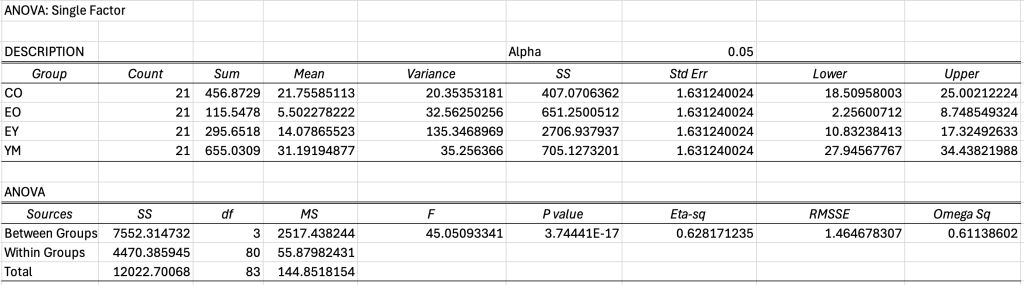

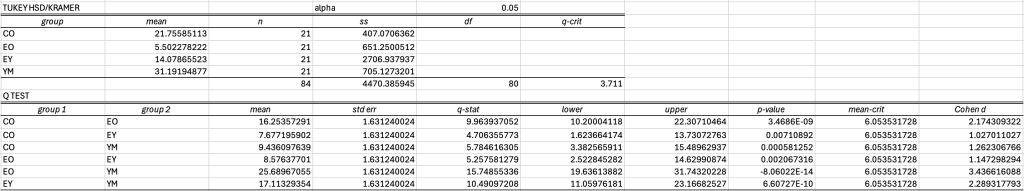

To determine statistical significance, the data was then analyzed using a One-Way ANOVA followed by a Tukey-HSD Test with an alpha value of 0.0519. The results are summarized in Figure 5, and the complete statistics, along with standard errors and ANOVA results can be found in Appendix A while the dataset can be found in Appendix C.

Qualitative observations showed no significant morphological changes to the planaria, the only changes observed qualitatively were lethargy in those groups exposed to EtOH, a lowered budding or reproduction rate in the planaria exposed to Ethanol. This budding rate was not recorded as the researcher did not expect reproduction to occur in any group other than the Control.

Analysis

Figure 5 shows the difference between the groups in columns 1 and 2, comparing every group to every other group. As seen in Figure 5.1 and 5.2, Yerba Mate causes a statistically significant increase in the Average Distance and Average Velocity of the Planaria as the average of YM is higher than CO with a p-value less than the alpha value (0.00058 < 0.05). This confirms Yerba Mate as a powerful stimulant for Planaria and is consistent with Yerba Mate’s high concentration of Caffeine and other Methylxanthines. The second statistic of note is the difference between CO and EO; here, the Average Distance and Velocity of CO are higher than EO with a p-value lower than the alpha value. This means long-term exposure to 1.0% Ethanol significantly reduced the movement in Planaria, consistent with previous research on similar concentrations and establishing the long-term effects of EtOH, something absent from the literature19. This confirms EtOH as a neurotoxic, neurodegenerative, and teratogenic agent in Planaria. Figure 5 also shows that the average for EY was higher than that of EO with a p-value lower than the alpha (0.002 < 0.05). This indicates a significantly higher CNS integrity for the EY group, as previous research has established COM as a method to measure relative CNS integrity33. This represents a rejection of the null hypothesis, and while previous research has indicated Yerba Mate’s neuroprotective and regenerative properties, it shows it is effective both in vivo and over long-term exposure.

Discussion

This finding demonstrates the effectiveness of Yerba Mate as a whole, rather than its chemical components as in past research, in protecting neural cells or stimulating their regeneration. Based on previous research demonstrating the effects of individual Yerba Mate components, it is most likely a combination of both of these effects3,34. This serves as a proof of concept for the potential clinical application of Yerba Mate and Ilex Paraguariensis in treating and preventing neurological disorders as it strongly suggests causality between Yerba Mate exposure and the reduced effect of neurotoxins.

As such, further research should be conducted to determine whether Yerba Mate’s neuroprotective or regenerative properties were responsible for this result. These results also show that the potential negative and toxic components of Yerba Mate do not have significant negative effects on regeneration. One concern was the potential for the Saponins in Yerba Mate to kill the rapidly differentiating and reproductive cells in the Planaria as they have been shown to induce apoptosis in tumor-like cells16. Another was the lethality of the Caffeine and methylxanthines in Yerba Mate; this study demonstrates that the methods used to prepare the Yerba Mate medium and the concentration are safe for research on planaria. There is, however, still a large gap in the literature; further research should, therefore, be conducted to determine the exact concentration of constituent components, the safe concentration range of the Yerba Mate brew described in the methods as well as other brews, and on variable concentrations of each brew to determine the optimal concentration for neuroprotection and regeneration. The correlative effects between feeding time and starvation and Yerba Mate and Ethanol should be investigated. The planaria were starved to conform with previous research practices but it is likely that feeding time is correlated with locomotion and metabolic activity. As such the relationship between feeding and metabolism should be investigated, as should the resulting effect of feeding time and Yerba Mate on planaria locomotion.

Based on correlations between Yerba Mate consumption and lowered rates of Parkinson’s disease, this experiment should be repeated with 6-hydroxydopamine, a toxin commonly used to induce Parkinsonian pathology in Planaria3,35. This would provide experimental evidence to support or refute the correlation and advance the potential clinical uses of Yerba Mate.

The study also provides a foundation for future research on the in vivo use of neoblasts and stem cells for treating neurodegenerative diseases. The results in the EtOH group show the ineffectiveness of neoblasts for neuroregeneration in this experiment, this result may not apply to neurodegenerative diseases as it is possible the EtOH inhibited the neoblasts’ ability to differentiate and migrate into new neural cells. This is merely speculation, however, and further research should be conducted on isolated neoblast cells to explore the impact of EtOH on their differentiation and migration. Then, follow-up research should be conducted to determine the effect of Yerba Mate, if any, on neoblast differentiation and migration into neural cells, especially in synergy with EtOH.

This study simply provides a viable proof of concept for the use of Yerba Mate in vivo for treating neurological disorders and in regenerative medicine. Its results, while encouraging, are not definitive, and more research is required to verify and understand the underlying mechanisms of Yerba Mate’s neuroprotective effects.

Limitations

As the result was conclusive, it is important to highlight the limitations of this experiment. Although significant effort was put into ensuring a controlled environment, there were many issues maintaining it. Due to the lack of resources in High School, the Lab was not temperature-controlled after 5 PM and before 6 AM. This did not severely impact the results as the temperature change was minimal and equally affected all groups. Another limitation is the lack of unfasted control. This was not foreseen during the experiment but it is possible that fasting the planaria before the study could impact the effect of Yerba Mate or ethanol on the planaria. As such the relationship between feeding time and behavior, with and without EtOH and Yerba Mate, should also be studied in future research. A third limitation was the fact that EtOH may have evaporated from the medium when it was not changed. This could have caused decreased EtOH exposure before the medium was changed every week.

One other major limitation was the arbitrarily chosen Yerba Mate concentration, a low concentration was picked to minimize the chance of death from Methylxanthine poisoning. Further research should be conducted with variable Yerba Mate concentrations and the concentrations of specific components found in Yerba Mate. Furthermore the brewing method for the mate cocido is based on the author’s personal and familial experience with Yerba Mate. This makes the exact brew rather arbitrary and unrepresentative of the tremendous variety found throughout South America. As such different brewing methods should be studied and formalized in order to determine which is most effective for neuroprotection. Furthermore, a positive control for a neuroprotective effect was not included in this study due to resource constraints. As such this study only serves to compare the effects of Yerba Mate and Ethanol against a negative control (EO), and a blank control (Water). The relative effect of Yerba Mate as a neuroprotective agent should be compared to known neuroprotective drugs such as Riluzole in order to better understand its potential as a neuroprotective agent.

Although the code used was modified from previous research, there were several bugs during testing. While most bugs were patched and avoided, a few dormant bugs could have caused inaccurate readings during data collection. These bugs, however, should not severely impact the result as the outliers caused by the errors were removed before the data analysis.

Currently, the results do not apply to clinical research. Planaria are not mammals; as such, the results of this study cannot be applied to humans. This study is also specific only to the neurotoxic effects caused by EtOH. While this is a good proof of concept, this study cannot be generalized to other organisms or even other toxins, it is possible that a compound in the Mate reacted with EtOH and neutralized it rather than protecting the Planarian CNS, because of these limitations, further research should be done to confirm these results.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of Yerba Mate (Ilex Paraguariensis), a drink traditional in South America, in increasing Central Nervous System (CNS) integrity and decreasing the neurodegenerative effects of long-term exposure to 1.0% Ethanol (EtOH). Using the Center Of Mass Tracking, this study showed Planaria exposed to a brew of 1.0% mate cocido and 1.0% EtOH had significantly higher CNS integrity than those exposed only to 1.0% EtOH. The results of this study are encouraging and spawn a new field of questions on the effects of Yerba Mate and the biochemical mechanisms of its apparent neuroprotective qualities. The effect of Mate on neoblasts in Planaria should also be investigated as Mate may have increased the regenerative capacity of the Planaria rather than simply reduced the negative effect of EtOH on the nervous system. This distinction is important as it is the difference between a clinically useful result, a result that simply advances our understanding of stem cell differentiation. If Yerba Mate is indeed neuroprotective, then research should be done to extrapolate these results to humans and develop Yerba Mate as a potential treatment for neurological diseases. If it simply increases the regenerative capacity of Planaria Mate may still be applicable to stem cell research, but it cannot be studied clinically for disease treatment, at least immediately, as adult human stem cells are rare36. To better understand these results, this experiment should be repeated with other compounds, such as 6-Hydroxidomanie, along with further studies on isolated neoblasts. Although more research is required, these results provide hope for and insight into the use of Stem Cells and the potential future treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Appendix

A.1: ANOVA test and Tukey ad-hoc for Distance

A.2: ANOVA test and Tukey ad-hoc for Average Velocity

B.1: createFileNames.py

This program that creates the filenames based on the camera number (group) and time in order to aid in sorting

B.2: record.py

This program is the recording software which records the videos from the cameras and automatically names them using the program in B.1

B.3: distanceTracker.py

This program calculates the total distance of the planaria from a video input

B.4: processFiles.py

This is the program that was run after everything was recorded, it automatically iterates over every video file, parses the name generated by B.1 runs the program in B.3 and saves the data to a CSV file.

References

- Van Schependom, Jeroen, and Miguel D’haeseleer. “Advances in Neurodegenerative Diseases.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, 1709. (2023). [↩]

- Dugger, Brittany N., and Dennis W. Dickson. “Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 9, a028035. (2017). [↩]

- Medeiros, Márcio Schneider, Artur Francisco Schumacher-Schuh, Vivian Altmann, and Carlos Roberto de Mello Rieder. “A Case–Control Study of the Effects of Chimarrão (Ilex Paraguariensis) and Coffee on Parkinson’s Disease.” Frontiers in Neurology 12, 619535. (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Bracesco, N., A.G. Sanchez, V. Contreras, T. Menini, and A. Gugliucci. “Recent Advances on Ilex Paraguariensis Research: Minireview.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 136, 378–84. (2011). [↩] [↩]

- Rink, Jochen C. “Stem Cell Systems and Regeneration in Planaria.” Development Genes and Evolution 223, 67–84. (2013). [↩]

- Reddien, Peter W. “The Cellular and Molecular Basis for Planarian Regeneration.” Cell 175, 327–45. (2018). [↩]

- Shomrat, Tal, and Michael Levin. “An Automated Training Paradigm Reveals Long-Term Memory in Planaria and Its Persistence through Head Regeneration.” Journal of Experimental Biology,, jeb.087809. (2013). [↩]

- Deochand, Neil, Mack S. Costello, and Michelle E. Deochand. “Behavioral Research with Planaria.” Perspectives on Behavior Science 41, 447–64. (2018). Pagán, Oné R. “Planaria: An Animal Model That Integrates Development, Regeneration and Pharmacology.” The International Journal of Developmental Biology 61, 519–29. (2017). [↩]

- Best, Jay Boyd, and Michio Morita. “Planarians as a Model System for in Vitro Teratogenesis Studies.” Teratogenesis, Carcinogenesis, and Mutagenesis 2, 277–91. (1982). [↩]

- Hagstrom, Danielle, Olivier Cochet‐Escartin, and Eva‐Maria S. Collins. “Planarian Brain Regeneration as a Model System for Developmental Neurotoxicology.” Regeneration 3, 65–77. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Wu, Jui-Pin, and Mei-Hui Li. “The Use of Freshwater Planarians in Environmental Toxicology Studies: Advantages and Potential.” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 161, 45–56. (2018). [↩] [↩]

- Heck, C.I., and E.G. De Mejia. “Yerba Mate Tea ( Ilex Paraguariensis ): A Comprehensive Review on Chemistry, Health Implications, and Technological Considerations.” Journal of Food Science 72, (2007). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Gawron-Gzella, Anna, Justyna Chanaj-Kaczmarek, and Judyta Cielecka-Piontek. “Yerba Mate—A Long but Current History.” Nutrients 13, 3706. (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Loria, Dora, Enrique Barrios, and Roberto Zanetti. “Cancer and Yerba Mate Consumption: A Review of Possible Associations.” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 25, 530–39. (2009). [↩]

- Ramirez-Mares, Marco Vinicio, Sonia Chandra, and Elvira Gonzalez de Mejia. “In Vitro Chemopreventive Activity of Camellia Sinensis, Ilex Paraguariensis and Ardisia Compressa Tea Extracts and Selected Polyphenols.” Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 554, 53–65. (2004). [↩]

- Alegre, Porto, and Junho de. “Effects of Green Tea, Yerba Mate and Rooibos Tea on C6 Astroglial Cells,”. (2016). [↩] [↩]

- Schinella, Guillermo, Juliana C. Fantinelli, and Susana M. Mosca. “Cardioprotective Effects of Ilex Paraguariensis Extract: Evidence for a Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanism.” Clinical Nutrition 24, 360–66. (2005). Collins, Erica Leighanne. “The Effect of Caffeine and Ethanol on Flatworm Regeneration.,”. (2007). [↩]

- Tribbia, Lilana, Gimena Gomez, Andrea Cura, Roy Rivero, Alejandra Bernardi, Juan Ferrario, Bertha Baldi-Coronel, Oscar Gershanik, Emilia Gatto, and Irene Taravini. “Study of Yerba Mate (Ilex Paraguariensis) as a Neuroprotective Agent of Dopaminergic Neurons in an Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease (P5.8-008).” Neurology 92, P5.8-008. (2019). [↩]

- Colsoul, Lore. “Neuroregeneration in ethanol- and 6-hydroxydopamine-exposed planarians,”. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Colsoul, Lore. “Neuroregeneration in ethanol- and 6-hydroxydopamine-exposed planarians,”. (2016). Cochet-Escartin, Olivier, Jason A Carter, Milena Chakraverti-Wuerthwein, Joydeb Sinha, and Eva-Maria S Collins. “Slo1 Regulates Ethanol-Induced Scrunching in Freshwater Planarians.” Physical Biology 13, 055001. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Best, Jay Boyd, Michio Morita, James Ragin, and Jay Best. “Acute Toxic Responses of the Freshwater Planarian,Dugesia Dorotocephala, to Methylmercury.” Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 27–27, 49–54. (1981). [↩]

- Cochet-Escartin, Olivier, Jason A Carter, Milena Chakraverti-Wuerthwein, Joydeb Sinha, and Eva-Maria S Collins. “Slo1 Regulates Ethanol-Induced Scrunching in Freshwater Planarians.” Physical Biology 13, 055001. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Hagstrom, Danielle, Olivier Cochet-Escartin, Siqi Zhang, Cindy Khuu, and Eva-Maria S. Collins. “Freshwater Planarians as an Alternative Animal Model for Neurotoxicology.” Toxicological Sciences 147, 270–85. (2015). [↩]

- Lowe, Jesse R., Tyler D. Mahool, and Mary M. Staehle. “Ethanol Exposure Induces a Delay in the Reacquisition of Function during Head Regeneration in Schmidtea Mediterranea.” Neurotoxicology and Teratology 48, 28–32. (2015). [↩]

- Voura, Evelyn B., Melissa J. Montalvo, Kevin T. Dela Roca, Julia M. Fisher, Virginie Defamie, Swami R. Narala, Rama Khokha, Margaret E. Mulligan, and Colleen A. Evans. “Planarians as Models of Cadmium-Induced Neoplasia Provide Measurable Benchmarks for Mechanistic Studies.” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 142, 544–54. (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Deochand, Neil, Mack S. Costello, and Michelle E. Deochand. “Behavioral Research with Planaria.” Perspectives on Behavior Science 41, 447–64. (2018). Best, Jay Boyd, and Michio Morita. “Planarians as a Model System for in Vitro Teratogenesis Studies.” Teratogenesis, Carcinogenesis, and Mutagenesis 2, 277–91. (1982). [↩]

- Voura, Evelyn B., Melissa J. Montalvo, Kevin T. Dela Roca, Julia M. Fisher, Virginie Defamie, Swami R. Narala, Rama Khokha, Margaret E. Mulligan, and Colleen A. Evans. “Planarians as Models of Cadmium-Induced Neoplasia Provide Measurable Benchmarks for Mechanistic Studies.” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 142, 544–54. (2017). Carolina Biological Supply. “Care Guide: Planaria.” https://www.carolina.com/teacher-resources/Interactive/care-guide-planaria/tr10534.tr. (n.d). [↩]

- Carolina Biological Supply. “Care Guide: Planaria.” https://www.carolina.com/teacher-resources/Interactive/care-guide-planaria/tr10534.tr. (n.d). [↩] [↩]

- Hagstrom, Danielle, Olivier Cochet‐Escartin, and Eva‐Maria S. Collins. “Planarian Brain Regeneration as a Model System for Developmental Neurotoxicology.” Regeneration 3, 65–77. (2016). Talbot, Jared, and Eva-Maria Schötz. “Quantitative Characterization of Planarian Wild-Type Behavior as a Platform for Screening Locomotion Phenotypes.” Journal of Experimental Biology 214, 1063–67. (2011). [↩]

- Moustakas, Dimitrios, Michael Mezzio, Branden R. Rodriguez, Mic Andre Constable, Margaret E. Mulligan, and Evelyn B. Voura. “Guarana Provides Additional Stimulation over Caffeine Alone in the Planarian Model.” Edited by Christian Holscher. PLOS ONE 10, e0123310. (2015). [↩]

- Hagstrom, Danielle, Olivier Cochet‐Escartin, and Eva‐Maria S. Collins. “Planarian Brain Regeneration as a Model System for Developmental Neurotoxicology.” Regeneration 3, 65–77. (2016). Raffa, Robert B, Lauren J Holland, and Robert J Schulingkamp. “Quantitative Assessment of Dopamine D2 Antagonist Activity Using Invertebrate (Planaria) Locomotion as a Functional Endpoint.” Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 45, 223–26. (2001). Pagán, Oné R., Debra Baker, Sean Deats, Erica Montgomery, Matthew Tenaglia, Clinita Randolph, Dharini Kotturu, et al. “Planarians in Pharmacology: Parthenolide Is a Specific Behavioral Antagonist of Cocaine in the Planarian Girardia Tigrina.” The International Journal of Developmental Biology 56, 193–96. (2012). [↩]

- Liu, Yilin, and L. Ella. “PlanariaScan: Development of a Video-Based Monitoring System on Planaria Learning and Memory under Various Stressors.” In 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI), 1–6. Mt Pleasant, MI, USA: IEEE, (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Talbot, Jared, and Eva-Maria Schötz. “Quantitative Characterization of Planarian Wild-Type Behavior as a Platform for Screening Locomotion Phenotypes.” Journal of Experimental Biology 214, 1063–67. (2011). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Aliabadi, Meysam, Bor Shin Chee, Mailson Matos, Yvonne J. Cortese, Michael J. D. Nugent, Tielidy A. M. de Lima, Washington L. E. Magalhães, and Gabriel Goetten de Lima. “Yerba Mate Extract in Microfibrillated Cellulose and Corn Starch Films as a Potential Wound Healing Bandage.” Polymers 12, 2807. (2020). [↩]

- Nishimura, Kaneyasu, Takeshi Inoue, Kanji Yoshimoto, Takashi Taniguchi, Yoshihisa Kitamura, and Kiyokazu Agata. “Regeneration of Dopaminergic Neurons after 6‐hydroxydopamine‐induced Lesion in Planarian Brain.” Journal of Neurochemistry 119, 1217–31. (2011). [↩]

- Cable, J., Fuchs, E., Weissman, I., Jasper, H., Glass, D., Rando, T. A., Blau, H., Debnath, S., Oliva, A., Park, S., Passegué, E., Kim, C., & Krasnow, M. A. Adult stem cells and regenerative medicine—A symposium report. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1462(1), 27–36. (2020). [↩]