Abstract

Background: Few articles have provided a comprehensive look at the total range of physical and mental ailments caused by Gulf War Illness among American veterans. A systematic review may help with this description.

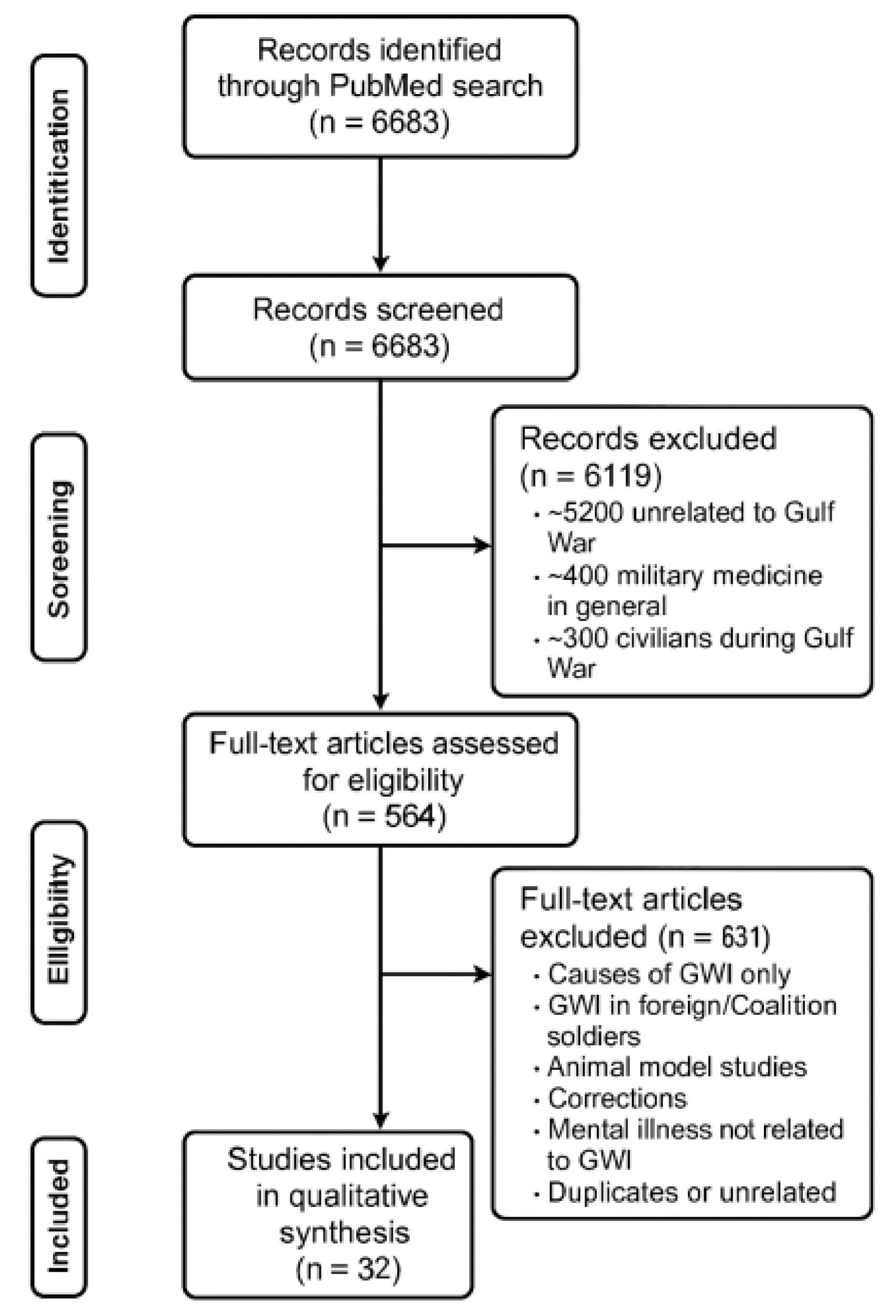

Methods: A PubMed search was conducted to compile studies on the relevant subject matter, using filters and keywords to identify studies on post-deployment effects. The automatic search results were then manually reviewed to remove irrelevant or duplicate articles. Studies deemed to be relevant to this search involved direct mental or physical effects on deployed Gulf War American veterans, which represented 32 studies found.

Results: All 32 studies within this analysis indicated the definite presence of a chronic multi-symptom illness that significantly impacted deployed Gulf War veterans, with 31% of Gulf War veterans meeting CDC criteria for Gulf War Illness. GWI, in particular, involves a broad range of primarily neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms, along with additional symptoms related to pain, fatigue, and various ailments affecting blood cells and other bodily systems. In total, all veterans who met criteria for GWI showed signs of significant neurological symptoms across 12 studies.

Conclusions: Gulf War Illness is a significant multi-symptom syndrome that has a broad range of observed effects across mental, neurological, somatic, cellular, and overall health. For many Gulf War veterans, this represents a significant decrease in health-related quality of life and health prospects. It is an extremely complex disorder that necessitates multiple specialists in treatment.

Keywords: Gulf War Illness, military medicine, effects of environmental exposure, nerve agent, PB pills, pesticides,

Introduction

Background and Context

In 1990, Iraq, under the leadership of Saddam Hussein, invaded its neighbor, Kuwait. In response, President Bush authorized the deployment of almost 697,000 American servicemembers to Operation Desert Shield/Storm. Although the land operation only took a hundred hours to complete, the deployment of troops to the region and their continued presence there led to the rise of so-called “Gulf War Illness” (GWI) among the campaign’s veterans. This comprises a multi-symptom disorder that impacts about 31-44% of the 700,000 Americans deployed to Iraq and seems to present the same set of conditions, including fatigue, headaches, cognitive dysfunction, musculoskeletal pain, and respiratory, gastrointestinal, and dermatologic complaints1‘2.

Gulf War Illness is diagnosed through the Centers for Disease Control’s CMI GWI criteria or the Kansas GWI criteria. The CDC criteria require that the veteran exhibits at least two of the following chronic symptoms (lasting more than six months): pain, fatigue, mood swings, and cognitive alterations. The Kansas GWI criteria, the stricter of the two, require that the veteran has at least one moderate or severe chronic symptom in three of the following domains: fatigue/sleep problems, pain, neurologic/cognitive/mood symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and skin symptoms. Psychiatric comorbidities like PTSD will not be included as symptoms of GWI, but chronic depression will be included in the symptom range.

The most probable causes of GWI are exposure to nerve agents such as sarin, pills containing pyridostigmine bromide, which were meant to be used as anti-nerve agent prophylaxis, and pesticides released in Iraq3‘4‘1.

American soldiers participating in the invasion of the Persian Gulf were exposed to low levels of nerve agents, including sarin, when Iraqi chemical weapon facilities were bombed by Coalition air support in the weeks leading up to the invasion, which may be strongly linked to many neurological symptoms of GWI3.

Additionally, exposure among Gulf War veterans (GWV) to pyridostigmine bromide pills (PB pills) maybe linked to some of the neurological and somatic symptoms of GWI4.

Lastly, pesticides excessively sprayed in theater were frequently exposed to American troops fighting in Iraq, and could be linked to neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms of GWI1.

These primary factors, along with additional interactions between stressors and environment, lead to a variety of significant long-term symptoms among Gulf War veterans, both in the mental and physical domains.

Problem Statement and Rationale

This study is attempting to provide a comprehensive look at the total range of symptoms and related disorders afflicting patients with Gulf War Illness. toshow the need for multi-specialty support for those patients.

Significance and Purpose

This collation is important because it can reveal all signs that a healthcare provider may look for when diagnosing Gulf War Illness, as well as, more urgently, providing the possible complications that may develop in a patient with GWI.

Objectives

This analysis aims to collate and compile studies on the physical and mental symptoms exhibited by Gulf War-era American veterans with Gulf War Illness to show the broad range of effects and how their treatment must reflect that.

Scope and Limitations

This literature review was limited to the research published on PubMed, a service of the National Library of Medicine. Additionally, the research utilized in this review may have a slight data bias due to the patient population used. This population reflects those veterans who elected to seek medical care to have a diagnosis of GWI and also elected to participate in the research.

Methodology Overview

A literature search on PubMed was used to find research articles on Gulf War Illness using keywords to find relevant articles, which were then manually reviewed to remove irrelevant or duplicate articles. These selected articles were then reviewed once more to find applicable articles that directly dealt with symptoms experienced by American veterans of the Gulf War.

Methods

Search Strategy

A bibliography search was conducted on PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) to compile studies regarding the appropriate subject material, with filters of English language studies and keywords to find studies regarding post-reconstruction effects. The keywords used were (Desert Storm OR Gulf War OR U.S. Veteran OR 1991 OR VA OR Veterans Affairs) AND (Gulf War Illness OR Gulf War Syndrome OR PTSD OR Chronic Fatigue Syndrome OR Cognitive Impairment). The search was conducted on May 24, 2025, with English language restrictions and no date restrictions on the PubMed Central database.

The final search string looked like this:5 OR 1991[All Fields] OR VA[All Fields] OR6 AND7 OR (“cognitive dysfunction”[MeSH Terms] OR (“cognitive”[All Fields] AND “dysfunction”[All Fields]) OR “cognitive dysfunction”[All Fields] OR (“cognitive”[All Fields] AND “impairment”[All Fields]) OR “cognitive impairment”[All Fields].

The automatic search results were then manually reviewed by eliminating non-American studies, studies that did not cover Gulf War Illness, or studies that did not research specific individual symptoms related to Gulf War Illness to remove irrelevant or duplicate articles. The relevant studies were identified by their title, abstract, or text.

For the purposes of inclusion/exclusion, Gulf War Illness is defined as a complex multi-symptom syndrome with neurological, somatic, cognitive, and gastrointestinal symptoms that affected American servicemembers deployed to Iraq or Kuwait during the Gulf War.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies deemed to be relevant to this search were studies that involved direct mental or physical effects on Gulf War-era American veterans who directly deployed to the Persian Gulf and were involved in operations in Kuwait and Iraq.

There were 6683 results that appeared initially, but the vast majority were revealed to be either studies that were completely unrelated or only tangentially related to the subject matter at hand. After manually reviewing the articles, 6119 articles were removed from consideration, with approximately 5200 articles being unrelated to the Gulf War, 400 articles about military medicine in general, 300 articles about civilians during the Gulf War, and 200 being about PTSD or other combat-involved mental illness unrelated to the Gulf War. These are approximate figures, but they help to show the spread of unrelated subject matter that was discarded for this systematic review.

The 564 articles remaining were then manually reviewed to find articles that specifically matched the inclusion criteria.

By the end of the results, 32 studies were identified as individually representing a symptom or group of symptoms directly relating to the Gulf War deployment of American veterans. The other studies were taken out for being related to causes of Gulf War Illness, symptoms of GWI in foreign or other Coalition soldiers, symptoms of GWI represented by rat or mouse models, corrections to other articles, duplicates, mental illness not directly related to GWI, or articles completely unrelated to GWI.

Data Extraction

Data was extracted from studies deemed to be relevant by manual review, which looked for studies that involved direct clinical research involving Gulf War veterans, with demographics of Gulf War-era veterans, and outcomes that resulted in individual symptoms for patients that followed patterns supported by numerical data within each study.

Synthesis Method

This study is a narrative review. The results from each study were organized by the particular body system or subsequent disorder that they covered and proved. Each study was grouped with others in terms of the field they approached to aid in organization and reference. The groups used in this thematic synthesis were: General descriptions of GWI (studies that show correlations with broad swathes of symptoms or Gulf War Illness in general), Cognitive Ability, General Neurological Symptoms, Cerebral Blood Flow, Somatic, Cellular Health, and Cholinergic System Symptoms.

Results

Overall, the studies selected covered thousands of American servicemembers who were deployed to the Persian Gulf from 1990-1991 during the war, in all areas of the theater and within all service branches.

All studies within this analysis indicated the definite presence of a chronic multi-symptom illness that significantly impacted deployed Gulf War veterans, completely separate from typical combat-related illnesses that befall servicemen. GWI in particular involves a broad range of primarily neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms, along with additional symptoms relating to pain, fatigue, and dispersed ailments in blood cells and other bodily systems.

Of the 32 studies involved in this systematic review, all of them supported the existence of a very significant and distinct multi-symptom illness that involved a broad variety of ailments, both physical and mental. The summaries of the thirty studies are below, primarily with the direct symptoms and effects of deployment-related exposures.

These studies have been broken down into the respective medical fields to which their symptoms relate.

General descriptions of GWI

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 14,103 Gulf War Veterans | 31% met CDC criteria for severe GWI2. | exposure to chemical/biological warfare agents, pyridostigmine bromide pills, and skin pesticides4 |

| 2 | 35,902 Gulf War-era veterans (13,107 deployed, 22,795 not deployed) | Deployed Gulf War veterans had higher percentages for every marker of both the Kansas definition for GWI and the CDC definition8. | No cause discussed |

| 3 | 703 Gulf War VeteransMatched non-GW Veterans | GWV that met the criteria for severe Chronic Multisymptom Illness (CMI) had the highest Veterans Affairs Fraility Index (0.13 ± 0.10, p < 0.001)GWV who met CMI criteria had much higher rates of dementia than control GMV9 | High VA-FI scores were directly related to self-reported environmental exposure attained during the Gulf War, including the use of flea collars7. |

| 4 | 15,000 deployed Gulf War veteransMatched set of non-deployed veterans | GWV were more likely to have functional impairment, health care utilization, symptoms, medical conditions, and a higher rate of low general health perceptions10. | No causes discussed |

| 5 | 3695 subjects (GWV and non-deployed veterans) | Compared to non-deployed veterans, Gulf War veterans had a significantly higher incidence rate of symptoms of:depression (17.0% vs 10.9%; P<.001)PTSD (1.9% vs 0.8%, P=.007)chronic fatigue (1.3% vs 0.3%, P<.001)cognitive dysfunction (18.7% vs 7.6%, P<.001)bronchitis (3.7% vs 2.7%, P<.001)asthma (7.2% vs 4.1%, P=.004)fibromyalgia (19.2% vs 9.6%, P<.001)alcohol abuse (17.4% vs 12.6%, P=.02)anxiety (4.0% vs 1.8%, P<.001)sexual discomfort (respondent, 1.5% vs 1.1%, P=.009; respondent’s female partner, 5.1% vs 2.4%, P<.001)11. | No causes discussed |

| 6 | 1,896 deployed Gulf War veterans1,799 non-deployed veterans | Compared to non-deployed veterans, GWV exhibited significantly greater prevalences of 123 of 137 (90%) symptoms, with none being lower.12. | No causes discussed |

| 7 | 76 veterans with GWI44 healthy veterans | Gulf War veterans who exhibit both GWI and PTSD were found to have significantly poorer health outcomes compared to healthy control groups and GWV without PTSD13. | No causes discussed |

| 8 | 1116 Gulf War Veterans | Veterans who met the Kansas GWI definition or the CDC GWI severe definition experienced lower health-related quality of life and higher rates of depression, PTSD, and severe pain14 | No causes discussed |

| 9 | 608 deployed Gulf War veterans | Veterans reporting hearing chemical alarms/donning Military-Ordered Protective Posture Level 4 (MOPP 4) protective gear, pesticide use, and using PB pills as prophylaxis against nerve agents exhibited a high level of moderate-to-severe chronic symptoms in neurocognitive/mood, fatigue/sleep, and pain domains15. | pesticide exposure (concentration and memory problems, unrefreshing sleep, problems sleeping, joint pain, pain symptom severity)PB pill use (depression, overall symptom severity)MOPP 4 use (light sensitivity and unrefreshing sleep) |

Cognitive Ability

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 2,189 Gulf War veterans (1,061 deployed, 1,128 non-deployed) | Deployed GWV performed significantly worse on motor speed and sustained attention tests than non-deployed veterans16. | exposure to chemical weapons (lower scores on motor speed)Self-reported exposure to toxicants (lower scores on sustained attention tests). |

| 2 | 952 Gulf War veterans | 17% met the criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and were more likely to have CMI and a history of depression17. | Those with prolonged exposures (≥31 days) to smoke from oil well fires and chemical nerve agents were more likely to have MCI |

| 3 | 411 GW veterans (312 GWI and 99 healthy veterans) | Those with GWI showed significantly poorer attention, executive functioning, learning, and short- and long-term verbal memory than those without GWI18. | significant exposure to pesticides and nerve agents (worse performance on executive function tasks)exposure to oil well fires (worse performance on verbal memory)pyridostigmine bromide pill exposures (worse performance on an attention task) |

| 4 | 40 deployed GW veterans exposed to sarin (GB) and cyclosarin (GF)40 matched controls | GW veterans with suspected GB/GF exposure had reduced total GM and hippocampal volumes compared to their unexposed peers (p< or =0.01).There were significant, positive correlations between total WM volume and measures of executive function and visuospatial abilities in veterans with suspected GB/GF exposure19. | Exposure to sarin (GB) and cyclosarin (GF) nerve agents |

General Neurological Symptoms

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 293 Gulf War veterans | GWI veterans had more PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms, more GW-related exposures, and smaller basal ganglia volumes compared to healthy GW veterans20. | No causes discussed |

| 2 | 20 GWI veterans 20 controls | GWI veterans had significantly higher resting motor threshold (77.2% vs 55.6%), indicating diminished corticomotor excitability. Because RMT and diminished motor cortical excitability are known to be associated with chronic pain, GWI can be related to the cause of chronic pain in GW veterans, perhaps due to maladaptive supraspinal pain modulation21. | No causes discussed |

| 3 | 9 GWI Veterans9 Healthy GW Veterans | Veterans with GWI had reduced EEG power across all frequency bands in both REM and non-REM sleep, localized over the frontal lobe22. | No causes discussed |

| 4 | 621,902 GW veterans vs 746,248 non-GW veterans | No overall increased mortality risk for ALS, MS, Parkinson’s, or brain cancer; but prolonged exposure to nerve agents or oil fire smoke increased brain cancer mortality risk23. | Prolonged nerve agent or oil fire smoke exposure. |

| 5 | 2.5 million eligible military personnel (107 ALS cases) | Elevated ALS risk in deployed personnel (RR 1.92) versus in nondeployed personnel (RR=0.43), particularly in active duty, Air Force, and Army subgroups24. | Deployment to the Persian Gulf is linked to increased ALS risk. |

| 6 | 100,483 GW Veterans exposed to chemical weapons at Khamisiyah224,974 GW veterans deployed without possible exposure | Similar brain cancer mortality overall, but higher risk in years after exposure for exposed veterans25. | Possible exposure to chemical agents at the Khamisiyah facility. |

| 7 | 111 veterans with Gulf War Illness59 healthy control participants | 10% subcortical brain atrophy, mainly brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus; resembles toxic encephalopathy patterns26. | Exposure to toxic substances during deployment (oil fire smoke, solvents, fuels, insecticides, nerve agents, pyridostigmine bromide, etc.). |

| 8 | 51 GW veterans | 83% diagnosed with GWI; 57% had small fiber neuropathy (SFN). 21% of GWI+SFN cases are unexplained27. | No causes discussed |

Cerebral Blood Flow

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 17 GW veterans in 3 GWI subgroups Syndrome 1 (4 veterans): impaired cognition; Syndrome 2 (10 veterans): confusion-ataxia; Syndrome 3 (3 veterans): central neuropathic pain16 controls | Physostigmine infusions caused decreased hippocampal rCBF in controls and Syndrome 1, but abnormal increases in Syndromes 2 and 3. An increase extended to the left hippocampus in Syndrome 2 and both hippocampi in Syndrome 3.This study, conducted nearly 20 years after the conclusion of the Gulf War, shows that GWI may cause chronic hippocampal perfusion dysfunction in GW veterans28 | No causes discussed |

| 2 | 23 GWI patients vs 9 controls | During orthostatic motion, GWI group had lower dynamic cerebral autoregulation and large decreases in cerebral blood velocity after and during standing29. | No causes discussed |

Somatic

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 5 total DPO veteran cases (2 were GW veterans) | Both GW veterans had airway-centric injury, inflammation, and retained particulate matter; they developed diffuse pulmonary ossification after service30. | Hazardous airborne particles and toxicant exposure during Persian Gulf deployment, including diesel exhaust, burn pits, sandstorms, desert dust, combat dust, and oil well fire smoke. |

| 2 | 108 Gulf War veterans | PB-exposed veterans had higher dry eye symptom scores, more intense ocular pain, and thicker OCT readings in the outer temporal macula31. | Pyridostigmine bromide pill exposure. |

| 3 | 89 GW veteran participants (63 GWI cases and 26 controls) | GWI veterans had an altered gut microbiome (significant Bray–Curtis beta diversity difference); higher fatigue scores were linked to altered diversity32. | No causes discussed |

| 4 | 71 Veterans(30 Kansas GWI and 41 controls) | GWI veterans had higher dry eye symptom scores (OSDI: 41.20 vs 27.99, p=0.01) and higher eye pain scores (2.63 vs 1.22, p=0.03)33. | No causes discussed |

| 5 | Ft. Devens Cohort (448 GW veterans) vs 2013–2014 NHANES cohort (2949 matched controls) | FDC males had higher risk for 7 chronic conditions (HBP, high cholesterol, heart attack, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, bronchitis). PB exposure increased heart attack & diabetes risk; chemical agent exposure increased HBP, diabetes, arthritis, bronchitis34. | Exposure to chemical agents and PB pills |

Cellular Health

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | Lab study (neuroblastoma cells) | Combined exposure to pesticide CPF (71 μM), DEET (78 μM), and PB (19 μM) caused significant mitochondrial dysfunction and decreased mitochondrial respiratory states.In vitro study; findings suggest neurotoxic mitochondrial impairment from Gulf War–related chemical combinations35. | Combined pesticide, insect repellant, and antitoxin exposure. |

| 2 | 114 GW veterans (80 with GWI, 34 without) | Non-GWI veterans had 42% higher basal and 47% higher ATP-linked oxygen consumption; GWI group showed no anaerobic compensation.GWI-related reduction in mitochondrial respiratory function and glycolytic activity36. | No causes discussed |

Cholinergic System Symptoms

| Study | Sample Size | Results | Cause |

| 1 | 33 GWI veterans14 Healthy Gulf War veterans | GWI patients had significant decreases in cerebral blood flow after physostigmine infusion compared to controls.GW veterans with GWI may suffer from variants of a chronic encephalopathic syndrome due to altered cerebral blood flow in deep brain structures37. | No causes discussed |

| 2 | 96 GWIPs 44 Matched Controls | GWI veterans showed decreased cholinergic system performance with increased working memory load; shifted to using the prefrontal cortex for retrieval instead of encoding38. | Exposure to cholinergic-disruptive chemicals during the Gulf War. |

The common health effects (which appeared in multiple studies across 30% or more of patients with GWI) noted among Gulf War veterans with GWI include:

- Depression

- Chronic fatigue

- significant cognitive dysfunction

- Bronchitis

- Asthma

- Fibromyalgia

- severe risk for chronic life-threatening illness (high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart attack, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, and chronic bronchitis),

- increased likelihood of severe neurological illnesses (ALS, MS, Parkinson’s, and brain cancer),

- eye issues

- joint pain

- brain atrophy

- chronic pain

- alterations to gut microbiome diversity

- damage to cholinergic system processes

- changes in cerebral blood flow

Here is a table listing the studies in the order in which they appear in this systemic review with details of their composition.

| Study Number | Design | Sample Size | Demographics | Exposure Definitions | Diagnostic Criteria for GWI | Outcomes | Effect Measures | Citation |

| Study 1 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 14,103 GW veterans | Deployed GWV | Chemical/biological warfare agents, pyridostigmine bromide pills, skin pesticides | CDC criteria (severe GWI) | 31% met CDC severe GWI | Prevalence (%) | Reference 4 |

| Study 2 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 35,902 GW-era veterans (13,107 deployed, 22,795 non-deployed) | Deployed & non-deployed | Not discussed | Kansas & CDC criteria | Higher prevalence of GWI in deployed group | Odds Ratios / Prevalence | Reference 6 |

| Study 3 | Observational (case-control) | 703 GW veterans matched with non-GWV | GWV with severe CMI | Environmental exposures (flea collars) | CMI criteria | Higher VA Frailty Index; higher dementia rates | VA-FI scores; p-values | Reference 7 |

| Study 4 | Observational (matched cohort) | 15,000 deployed GWV matched to non-deployed | Deployed & non-deployed | Not discussed | Not specified | More functional impairment, healthcare utilization, symptoms, medical conditions | Risk differences | Reference 10 |

| Study 5 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 3,695 veterans (GWV & non-deployed) | Deployed & non-deployed | Not discussed | Not specified | Higher rates of depression, PTSD, chronic fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, bronchitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, alcohol abuse, anxiety, sexual discomfort | Prevalence with p-values | Reference 11 |

| Study 6 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 1,896 deployed vs 1,799 non-deployed | Deployed & non-deployed | Not discussed | Not specified | Greater prevalence in 123/137 symptoms (90%) | Prevalence ratios | Reference 12 |

| Study 7 | Observational (case-control) | 76 GWV with GWI, 44 healthy veterans | GWV with/without PTSD | Not discussed | Not specified | GWI + PTSD = worse health outcomes | Group comparisons | Reference 13 |

| Study 8 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 1,116 GWV | Deployed GWV | Not discussed | Kansas & CDC severe | Lower quality of life, more depression, PTSD, pain | Mean scores; prevalence | Reference 19 |

| Study 9 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 608 deployed GWV | Deployed GWV | Chemical alarms, MOPP 4 gear, pesticide use, PB pills | Not specified | High moderate-to-severe symptoms in neurocognitive/mood, fatigue/sleep, pain | Symptom severity scores | Reference 22 |

| Study 10 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 2,189 GWV (1,061 deployed, 1,128 non-deployed) | Deployed & non-deployed | Chemical weapons, self-reported toxicants | Not specified | Lower motor speed & sustained attention in deployed group | Neuropsych test scores | Reference 5 |

| Study 11 | Observational (cross-sectional) | 952 GWV | Deployed GWV | Prolonged exposure (≥31 days) to oil well fire smoke & nerve agents | Not specified | 17% MCI; more likely with CMI & depression history | Prevalence; odds ratios | Reference 9 |

| Study 12 | Observational (case-control) | 411 GWV (312 GWI, 99 healthy) | Deployed GWV | Pesticides, nerve agents, oil well fires, PB pills | Not specified | Poorer attention, executive function, memory | Neurocognitive test performance | Reference 16 |

| Study 13 | Observational (case-control) | 40 deployed exposed to GB/GF vs 40 matched controls | Deployed GWV | GB/GF nerve agents | Not specified | Reduced GM & hippocampal volume; WM volume correlated with executive function & visuospatial abilities | MRI volumetric measures; correlations | Reference 17 |

| Study 14 | Cross-sectional / observational | 293 GW veterans | Not specified beyond being GW veterans | Multiple GW-related exposures (deployment exposures) | Not specified (in source) | PD-like motor & non-motor symptoms; basal ganglia volume | GWI group = more PD-like symptoms; lower total basal ganglia volume vs healthy GWV | Reference 15 |

| Study 15 | Case–control (GWI vs matched controls) | 20 GWI (all male) vs 20 controls (all male) | All male; ages not specified | Noted chronic headaches/body pain; (GWI-related exposures implied) | Not specified (in source) | Resting motor threshold (TMS); corticomotor excitability | RMT: 77.2% ±16.7% (GWI) vs 55.6% ±8.8% (controls) — significantly higher in GWI | Reference 18 |

| Study 16 | Cross-sectional (GW vets vs controls) | 9 GWI Veterans9 Healthy GW Veterans | GW veterans vs control group (demographics not specified) | Gulf War deployment (general) | Not specified (in source) | High-density EEG — REM & non-REM sleep power across frequencies | Broadband reduction in EEG power across all bands in NREM & REM localized over frontal lobe in GW vets | Reference 23 |

| Study 17 | Retrospective cohort (large registry comparison) | 621,902 GW veterans vs 746,248 non-GW veterans | Veterans across cohorts (demographics not specified) | Prolonged (≥2 days) nerve agent exposure at Khamisiyah; oil well fire smoke | Not applicable (mortality cohort) | Mortality due to ALS, MS, Parkinson’s, brain cancer | No overall mortality difference; but ↑ brain cancer mortality risk with prolonged nerve agent or oil-well smoke exposure. | Reference 24 |

| Study 18 | Cohort (population registry) | 2.5 million eligible personnel (107 confirmed ALS cases) | All active & mobilized reserve personnel who served during Gulf War (1990–2000 window) | Deployment to Persian Gulf (deployment vs non-deployed) | Not applicable (ALS incidence analysis) | ALS incidence/cases | 107 cases; RR all deployed = 1.92 (95% CL 1.29–2.84); deployed active duty RR 2.15 (95% CL 1.38–3.36); deployed Air Force RR 2.68 (95% CL 1.24–5.78); deployed Army RR 2.04 (95% CL 1.10–3.77) | Reference 25 |

| Study 19 | Retrospective cohort / mortality analysis | 100,483 GW Veterans exposed to chemical weapons at Khamisiyah224,974 GW veterans deployed without possible exposure | US Army veterans deployed during the Gulf War (demographics not specified) | Possible exposure to chemical agents at Khamisiyah facility | Not applicable | Brain cancer mortality | Overall similar rates, but higher brain cancer risk in years following exposure among possibly-exposed group | Reference 26 |

| Study 20 | Cross-sectional / imaging case-control | 111 GWI vs 59 healthy controls | GWI avg age 49±6 yrs (~88% male); controls 51±9 yrs (~78% male) | Variety of deployment exposures: oil-well smoke, solvents, fuels, insecticides, nerve agents, PB, dust, etc. | GWI diagnosis as per study (noted as GWI group) | MRI volumetric measures — subcortical volumes (brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus, basal ganglia, amygdala) | ~10% subcortical atrophy affecting brainstem/cerebellum/thalamus primarily; pattern consistent with toxic encephalopathy. | Reference 27 |

| Study 21 | Clinic case series / observational | 51 GW veterans evaluated; 83% GWI (≈42), 57% with SFN (≈29) | GW veterans evaluated at NJ War Related Illness & Injury Study Center; demographics not specified | Deployment-related environmental exposures implied | GWI diagnosis per clinic evaluation (not specified whether Kansas/CDC) | Small fiber neuropathy (SFN) clinical + diagnostic tests; autonomic symptoms | 83% diagnosed with GWI; 57% had SFN; of 24 with GWI+SFN, 21% had no explanation for SFN — suggests possible deployment-related causes. | Reference 8 |

| Study 22 | Experimental challenge (physostigmine infusion) within case groups — cross-sectional/physiologic | 17 GW veterans in 3 GWI subgroups Syndrome 1 (4 veterans): impaired cognition; Syndrome 2 (10 veterans): confusion-ataxia; Syndrome 3 (3 veterans): central neuropathic pain16 controls | GW veterans grouped by symptom cluster (S1 impaired cognition; S2 confusion-ataxia; S3 central neuropathic pain) | Cholinergic challenge (physostigmine infusion) | GWI subgrouping by symptom cluster (study defined) | Regional hippocampal cerebral blood flow (rCBF) responses to physostigmine | Controls & Syndrome 1: decreased hippocampal rCBF after infusion; Syndromes 2 & 3: abnormal increase (progressed to left hippocampus in S2, bilateral in S3). Interpreted as chronic hippocampal perfusion dysfunction in GWI. | Reference 32 |

| Study 23 | Cross-sectional / physiologic | 23 GWI patients vs 9 controls | GWI patients vs controls; demographics not specified | Not an exposure study per se — GWI status | GWI defined by study (not specified which criteria) | Dynamic cerebral autoregulation; cerebral blood velocity during standing | GWI group had significantly lower dynamic cerebral autoregulation and substantial decreases in cerebral blood velocity after standing and during steady state standing — consistent with cerebral hypoperfusion. | Reference 36 |

| Study 24 | Case series (5 cases total; 2 GW veterans among them) | 5 DPO cases (Cases 4 & 5 are GW veterans) | Case 4: Army veteran; Case 5: Marine veteran; ages not specified | Substantial airborne particulate exposure: diesel exhaust, burn pits, sandstorms, desert dust, oil well fire smoke, combat dust | Not applicable (case reports) | Pulmonary pathology: airway-centric injury, inflammation, retained particulate matter; DPO development | Both GW veterans developed DPO after service; exposures likely contributed to DPO development. | Reference 14 |

| Study 25 | Cross-sectional / observational (exposed vs non-exposed) | 108 Gulf War veterans | Veterans with/without PB exposure; demographics not specified | Pyridostigmine bromide (PB) pill exposure reported during deployment | GWI status not specified for all subjects (study on PB exposure effects) | Dry eye symptom scores, ocular pain, OCT retinal thickness (outer temporal macula) | PB-exposed had higher DE scores, more intense ocular pain, and thicker OCT outer temporal macular segment; differences remained significant in multivariable models. | Reference 20 |

| Study 26 | Cross-sectional (microbiome comparison) | 89 GW veteran participants (63 GWI cases and 26 controls) | GW veterans with GWI vs controls; demographics not specified | GWI status (association with microbiome) | GWI defined per study (not specified) | Gut microbiome composition; Bray–Curtis beta diversity; self-reported fatigue (MFI) | Significant difference in Bray–Curtis beta diversity between GWI and controls; higher fatigue scores correlated with altered gut bacterial diversity. | Reference 30 |

| Study 27 | Cross-sectional | 71 Veterans(30 Kansas GWI and 41 controls) | GWI vs control veterans; demographics not stated | GWI status | GWI definition per study (not specified) | Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) scores; eye pain (past week) | OSDI: mean 41.20±22.92 (GWI) vs 27.99±24.03 (controls), p=0.01. Eye pain: 2.63±2.72 (GWI) vs 1.22±1.50 (controls), p=0.03. | Reference 31 |

| Study 28 | Comparative cohort / cross-sectional (cohort vs national survey) | Ft. Devens Cohort (448 GW veterans) vs 2013–2014 NHANES cohort (2949 matched controls) | FDC males (GW veterans) compared to general US male population (NHANES) | Self-reported exposures: chemical agents; PB pills | Not applicable (chronic disease prevalence comparison) | Prevalence of chronic conditions (HBP, cholesterol, heart attack, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, chronic bronchitis) | FDC males had increased risk for 7 chronic conditions; chemical exposure associated with ↑ risk (HBP, diabetes, arthritis, chronic bronchitis); PB exposure associated with ↑ heart attack & diabetes risk. | Reference 28 |

| Study 29 | In vitro experimental (neuroblastoma cell line) | Not applicable (cell culture exposures) | Neuroblastoma cells (cell model) | Combined chemical exposure: chlorpyrifos (CPF) 71 μM, DEET 78 μM, pyridostigmine bromide (PB) 19 μM | Not applicable | Mitochondrial respiration / mitochondrial respiratory states | Combined exposures caused significant mitochondrial dysfunction with decreased mitochondrial respiratory states. | Reference 21 |

| Study 30 | Cross-sectional / lab measures on human PBMCs | 114 GW veterans (80 with GWI, 34 without GWI per Kansas definition) | GW veterans; Kansas definition applied; ages/sex not specified | GWI status (case vs non-case) — interpreted as result of deployment exposures | Kansas GWI definition (explicitly stated) | Basal & ATP-linked oxygen consumption (mitochondrial respiration) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells; glycolytic activity | Non-GWI veterans had 42% higher basal and 47% higher ATP-linked O₂ consumption; GWI group showed decreased mitochondrial respiration & glycolysis (no anaerobic compensation). | Reference 29 |

| Study 31 | Experimental cholinergic challenge within case/control design | 33 GWI veterans14 Healthy Gulf War veterans | GW veterans with GWI vs control veterans | Physostigmine (inhibitory cholinergic challenge) infusion | GWI defined per study (not specified) | Cerebral blood flow (CBF) responses in deep brain structures after physostigmine | GWI patients showed significant decreases in CBF compared to controls after physostigmine infusion — suggests chronic encephalopathic variants tied to altered deep-structure CBF. | Reference 34 |

| Study 32 | Cross-sectional with cognitive task + imaging | 96 GWIPs 44 Matched Controls | GW veterans with GWI vs matched controls; demographics not specified | Cholinergic system dysfunction hypothesized from wartime cholinergic-disruptive chemical exposure | GWI defined per study (not specified) | Working memory task performance; functional imaging (prefrontal cortex activation patterns) | GWI showed decreased cholinergic performance as working memory load increased; imaging: GWI subjects used PFC retrieval strategies rather than encoding — interpreted as impaired executive/working memory strategies likely due to cholinergic-disruptive chemical exposure. | Reference 35 |

Discussion

This study confirms existing research, in that Gulf War Illness is a significant multi-symptom syndrome that has a broad range of observed effects across mental, neurological, somatic, cellular, and overall health. For many Gulf War veterans, this represents a significant decrease in health-related quality of life and health prospects13‘14. However, this study also adds new insight in the form of a collation of symptoms that suggests the multi-system involvement of Gulf War Illness.

All 32 of the studies within this review reported associations between deployment to the Persian Gulf and the presence of GWI, and also all reported associations between GWI and a variety of multi-system symptoms. Under the CDC criteria, about 84.2% of deployed Gulf War veterans met the criteria for GWI, while about 31% met the criteria for severe GWI. Additionally, about 39.9% of deployed Gulf War veterans met the Kansas GWI criteria39‘40.

Factors like sarin, PB pills, pesticides, and oil-fire smoke were extremely common during the Gulf War, and affected large portions of the deployed population. Every study within this review mentioned that the patient population utilized was exposed to at least one, if not a combination, of these factors. Veterans deployed in certain areas, such as the oil fields of Kuwait or near the Khamisiyah munitions storage facility, were exposed to oil fire smoke or low-level environmental nerve agents for the entire duration of their deployment, while factors like PB pills and pesticides affected most of the deployed service members, regardless of location. Evidence suggests that certain factors correlate with certain symptoms.

Exposure to chemical weapons like sarin may lead to lower motor speed, MCI, lower GM and hippocampal volumes, brain cancer risk, high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis, bronchitis, and decreased cholinergic system performance5,16,17,26,28,35.41‘42‘43‘44‘34‘45.

Exposure to PB pills, which were mandated across US forces during the land invasion, may lead to poor attention abilities, dry eye symptoms, ocular pain, depression, brain atrophy, and a higher risk of heart attacks and diabetes46‘47‘48‘49‘50

Exposure to pesticides, common throughout Iraq and Kuwait, may lead to poor performance on executive function tasks, mitochondrial dysfunction, concentration issues, memory issues, sleep problems, and joint pain46‘5152.

Exposure to oil-fire smoke may be linked to MCI, airway injury, diffuse pulmonary ossification, poor verbal memory, increased brain cancer mortality rate, and brain atrophy53‘54‘55‘56‘57.

The potential mechanisms that cause GWI point to its multi-system involvement. Analysis of the gene-toxicant interaction of PB pills with PON1 and the G allele of rs662 points to a strong connection between exposure to PB and the presence of neurological symptoms like attention problems, which are caused by the way that pyridostigmine bromide temporarily binds to acetylcholinesterase. Additionally, after examining the connection between gene-environment interaction of the paraoxonase-1 (PON1) Q192R polymorphism and low-level nerve agent exposure, evidence suggests that this low-level exposure caused differing neurological symptoms than exposure to PB pills, including mild cognitive impairment and loss of gray matter, by interfering with the degradation of the acetylcholine, which causes the patient to lose control of muscles. Furthermore, exposure to toxicants and foreign airborne particles may cause symptoms in other fields, like airway damage, loss of attention, and brain atrophy. The variety of mechanisms that lead to GWI and the multiple sources of exposure that Gulf War veterans encountered could explain the multi-system involvement of this syndrome58‘59‘60‘61‘53‘57.

These symptoms hold true when compared to matched sets of non-deployed Gulf War era veterans. When compared to non-deployed veterans, deployed veterans have lower scores on motor speed and sustained attention tests, higher dementia rates, greater prevalence of 123 out of 137 symptoms (with none being lower), higher brain cancer mortality rate, and a higher risk of developing ALS. Additionally, Study 5 of the “General Descriptions of GWI” section reports that deployed Gulf War veterans had a higher incidence rate of depression, chronic fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, bronchitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, alcohol abuse, anxiety, and sexual discomfort when compared to non-deployed veterans of the same demographics41‘62‘63‘64‘65‘66.

Therefore, it can clearly be shown that Gulf War Illness is an extremely significant and broad disorder, encompassing multiple body systems in exceptionally severe ways. This proves that treatment of the condition requires a multi-directional approach involving various specialties and observances. Additionally, any patient exhibiting Gulf War Illness must be carefully watched for other symptoms and developments, as this study has shown that this singular disorder can lead to a host of severe and life-threatening conditions, even if it presents with only mild symptoms.

Implications

Clinical Implications

Patients presenting with Gulf War Illness or any symptoms conveyed in this literature review, with the relevant service history, must be carefully diagnosed by their primary healthcare provider to scan for any related conditions that could develop using integrated care models. For example, a veteran diagnosed with physical symptoms of GWI, like airway damage or eye issues, may also need to be referred to a neurologist or psychiatrist to look for any neurological or mental symptoms that come with GWI, such as cognitive dysfunction, memory problems, or severe neurological conditions like ALS. As all of these conditions are very severe, time is of the utmost importance for diagnosis, and this complex list of possibilities warrants exceptional care and attention for such patients67‘68‘69‘66.

Research Implications

To help classify GWI and to make comparisons between studies easier, a single set of diagnostic criteria should be adopted, using the set of conditions from either the CDC or the Kansas GWI criteria.

Additionally, further research could use longitudinal designs to track the progression of certain severe symptoms of GWI within veterans, such as brain atrophy or ALS. This research could also track how different sets of symptoms progress within each veteran, such as the progression of neurological symptoms versus somatic symptoms.

Limitations

This systematic review was limited by the literature available on PubMed Central, so it may not reflect the totality of current medical research on this subject. Additionally, the studies contained within this article may have a slight data bias due to the population they studied, which consisted of only Gulf War veterans who agreed to get treatment or participate in these studies.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges and thanks all authors of the studies contained within this review, as well as all veterans of Operation Desert Storm for their service and willingness to participate in these studies.

References

- R. F. White, L. Steele, J. P. O’Callaghan, K. Sullivan, J. H. Binns, B. A. Golomb, F. E. Bloom, J. A. Bunker, F. Crawford, J. C. Graves, A. Hardie, N. Klimas, M. Knox, W. J. Meggs, J. Melling, M. A. Philbert, R. Grashow. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 74, 449-75. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4724528/. (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- L. Steele, R. Quaden, S. T. Ahmed, K. M. Harrington, L. M. Duong, J. Ko, E. J. Gifford, R. Polimanti, J. M. Gaziano, M. Aslan, D. A. Helmer, E. R. Hauser; Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program #2006 and the VA Million Veteran Program. Association of deployment characteristics and exposures with persistent ill health among 1990-1991 Gulf War veterans in the VA Million Veteran Program. Environ Health. 23(1), 92. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11520114/. (2024). [↩] [↩]

- R. W. Haley, G. Kramer, J. Xiao, J. A. Dever, J. F. Teiber. Evaluation of a Gene-Environment Interaction of PON1 and Low-Level Nerve Agent Exposure with Gulf War Illness: A Prevalence Case-Control Study Drawn from the U.S. Military Health Survey’s National Population Sample. Environ Health Perspect. 130(5), 57001. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9093163/. (2022). [↩] [↩]

- J. Vahey, E. J. Gifford, K. J. Sims, B. Chesnut, S. H. Boyle, C. Stafford, J. Upchurch, A. Stone, S. Pyarajan, J. T. Efird, C. D. Williams, E. R. Hauser. Gene-Toxicant Interactions in Gulf War Illness: Differential Effects of the PON1 Genotype. Brain Sci. 11(12), 1558. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8699623/. (2021). [↩] [↩]

- Desert[All Fields] AND Storm[All Fields]) OR (“gulf war”[MeSH Terms] OR (“gulf”[All Fields] AND “war”[All Fields]) OR “gulf war”[All Fields]) OR (“united states”[MeSH Terms] OR (“united”[All Fields] AND “states”[All Fields]) OR “united states”[All Fields] OR “u s”[All Fields]) AND (“veterans”[MeSH Terms] OR “veterans”[All Fields] OR “veteran”[All Fields] [↩]

- “veterans”[MeSH Terms] OR “veterans”[All Fields]) AND Affairs[All Fields] [↩]

- (“gulf war”[MeSH Terms] OR (“gulf”[All Fields] AND “war”[All Fields]) OR “gulf war”[All Fields]) AND Illness[All Fields]) OR (“persian gulf syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“persian”[All Fields] AND “gulf”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “persian gulf syndrome”[All Fields] OR (“gulf”[All Fields] AND “war”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “gulf war syndrome”[All Fields]) OR (“6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency”[All Fields] OR “ptsd”[All Fields] OR “stress disorders, post-traumatic”[MeSH Terms] OR (“stress”[All Fields] AND “disorders”[All Fields] AND “post-traumatic”[All Fields]) OR “post-traumatic stress disorders”[All Fields]) OR (“fatigue syndrome, chronic”[MeSH Terms] OR (“fatigue”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields] AND “chronic”[All Fields]) OR “chronic fatigue syndrome”[All Fields] OR (“chronic”[All Fields] AND “fatigue”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields] [↩]

- L. M. Duong, A. B. S. Nono Djotsa, J. Vahey, L. Steele, R. Quaden, K. M. Harrington, S. T. Ahmed, R. Polimanti, E. Streja, J. M. Gaziano, J. Concato, H. Zhao, K. Radhakrishnan, E. R. Hauser, D. A. Helmer, M. Aslan, E. J. Gifford. Association of Gulf War Illness with Characteristics in Deployed vs. Non-Deployed Gulf War Era Veterans in the Cooperative Studies Program 2006/Million Veteran Program 029 Cohort: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20(1), 258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC9819371. (2022). [↩]

- L. L. Chao. Examining the current health of Gulf War veterans with the veterans affairs frailty index. Front Neurosci. 17, 1245811. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10512703. (2023). [↩]

- H. K. Kang, C. M. Mahan, K. Y. Lee, C. A. Magee, F. M. Murphy. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 42(5), 491-501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10824302. (2000). [↩]

- Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans. A population-based study. The Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group. JAMA. 277(3), 238-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ 9005274. (1997). [↩]

- B. N. Doebbeling, W. R. Clarke, D. Watson, J. C. Torner, R. F. Woolson, M. D. Voelker, D. H. Barrett, D. A. Schwartz. Is there a Persian Gulf War syndrome? Evidence from a large population-based survey of veterans and nondeployed controls. Am J Med. 108(9), 695-704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10924645. (2000). [↩]

- E. Sultana, N. Shastry, R. Kasarla, J. Hardy, F. Collado, K. Aenlle, M. Abreu, E. Sisson, K. Sullivan, N. Klimas, T. J. A. Craddock. Disentangling the effects of PTSD from Gulf War Illness in male veterans via a systems-wide analysis of immune cell, cytokine, and symptom measures. Mil Med Res. 11(1), 2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10759613. (2024). [↩] [↩]

- E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, J. Vahey, K. J. Sims, J. T. Efird, B. Chesnut, C. Stafford, J. Upchurch, C. D. Williams, D. A. Helmer, E. R. Hauser. Health-Related Quality of Life by Gulf War Illness Case Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(8), 4425. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC9026791. (2022). [↩] [↩]

- S. T. Ahmed, L. Steele, P. Richardson, S. Nadkarni, S. Bandi, M. Rowneki, K. J. Sims, J. Vahey, E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, T. H. Nguyen, A. Nono Djotsa, D. L. White, E. R. Hauser, H. Chandler, J. M. Yamal, D. A. Helmer. Association of Gulf War Illness-Related Symptoms with Military Exposures among 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans Evaluated at the War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). Brain Sci. 12(3), 321. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC8946608. (2022). [↩]

- R. Toomey, R. Alpern, J. J. Vasterling, D. G. Baker, D. J. Reda, M. J. Lyons, W. G. Henderson, H. K. Kang, S. A. Eisen, F. M. Murphy. Neuropsychological functioning of U.S. Gulf War veterans 10 years after the war. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 15(5), 717-729. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19640317/. (2009). [↩]

- L. L. Chao, K. Sullivan, M. H. Krengel, R. J. Killiany, L. Steele, N. G. Klimas, B. B. Koo. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in Gulf War veterans: a follow-up study. Front Neurosci. 17, 1301066. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10838998. (2023). [↩]

- D. Keating, M. Krengel, J. Dugas, R. Toomey, L. Chao, L. Steele, L. P. Janulewicz, T. Heeren, E. Quinn, N. Klimas, K. Sullivan. Cognitive decrements in 1991 Gulf War veterans: associations with Gulf War illness and neurotoxicant exposures in the Boston Biorepository, Recruitment, and Integrative Network (BBRAIN) cohorts. Environ Health. 22(1), 68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10548744. (2023). [↩]

- H. E. Burzynski, L. P. Reagan. Exposing the latent phenotype of Gulf War Illness: examination of the mechanistic mediators of cognitive dysfunction. Front Immunol. 15, 1403574. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11196646. (2024). [↩]

- L. Chao. Do Gulf War veterans with high levels of deployment-related exposures display symptoms suggestive of Parkinson’s disease? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 32(4), 503–526. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11892701. (2019). [↩]

- K. Lei, A. Kunnel, V. Metzger-Smith, S. Golshan, J. Javors, J. Wei, R. Lee, M. Vaninetti, T. Rutledge, A. Leung. Diminished corticomotor excitability in Gulf War Illness related chronic pain symptoms; evidence from TMS study. Sci Rep. 10(1), 18520. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC7595115. (2020). [↩]

- E. W. Moffet, S. G. Jones, T. Snyder, B. Riedner, R. M. Benca, T. Juergens. Gulf War veterans exhibit broadband sleep EEG power reductions in regions overlying the frontal lobe. Life Sci. 280, 119702. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC12019881. (2021). [↩]

- S. K. Barth, H. K. Kang, T. A. Bullman, M. T. Wallin. Neurological mortality among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War: 13-year follow-up. Am J Ind Med. 52(9), 663-670. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19585544. (2009). [↩]

- R. D. Horner, K. G. Kamins, J. R. Feussner, S. C. Grambow, J. Hoff-Lindquist, Y. Harati, H. Mitsumoto, R. Pascuzzi, P. S. Spencer, R. Tim, D. Howard, T. C. Smith, M. A. Ryan, C. J. Coffman, E. J. Kasarskis. Occurrence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among Gulf War veterans. Neurology. 61(9), 1320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14504315. (2003). [↩]

- S. K. Barth, E. K. Dursa, R. M. Bossarte, A. I. Schneiderman. Trends in brain cancer mortality among U.S. Gulf War veterans: 21 year follow-up. Cancer Epidemiol. 50(Pt A), 22-29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC5824993. (2017). [↩]

- P. Christova, L. M. James, B. E. Engdahl, S. M. Lewis, A. F. Carpenter, A. P. Georgopoulos. Subcortical brain atrophy in Gulf War Illness. Exp Brain Res. 235(9), 2777-2786. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28634886. (2017). [↩]

- E. C. Shadiack 3rd, O. Osinubi, A. Gruber-Fox, C. Bhate, L. Patrick-DeLuca, P. Cohen, D. A. Helmer. Small Fiber Neuropathy in Veterans With Gulf War Illness. Fed Pract. 41(5), 136-141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11468626. (2024). [↩]

- X. Li, J. S. Spence, D. M. Buhner, J. Hart Jr, C. M. Cullum, M. M. Biggs, A. L. Hester, T. N. Odegard, P. S. Carmack, R. W. Briggs, R. W. Haley. Hippocampal dysfunction in Gulf War veterans: investigation with ASL perfusion MR imaging and physostigmine challenge. Radiology. 261(1), 218-225. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC3176422. (2011). [↩]

- M. J. Falvo, J. B. Lindheimer, J. M. Serrador. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation is impaired in Veterans with Gulf War Illness: A case-control study. PLoS One. 13(10), e0205393. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC6188758. (2018). [↩]

- J. T. Hua, C. D. Cool, T. J. Bang, S. D. Krefft, R. C. Kraus, C. S. Rose. Dendriform pulmonary ossification in military combat veterans: A case series. Respir Med Case Rep. 53, 102156. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11773146. (2024). [↩]

- L. E. Truax, J. J. Huang, K. Jensen, E. V. T. Locatelli, K. Cabrera, H. O. Peterson, N. K. Cohen, S. Mangwani-Mordani, A. Jensen, R. Goldhardt, A. Galor. Pyridostigmine Bromide Pills and Pesticides Exposure as Risk Factors for Eye Disease in Gulf War Veterans. J Clin Med. 12(6), 2407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10059791. (2023). [↩]

- A. Trivedi, D. Bose, K. Moffat, E. Pearson, D. Walsh, D. Cohen, J. Skupsky, L. Chao, J. Golier, P. Janulewicz, K. Sullivan, M. Krengel, A. Tuteja, N. Klimas, S. Chatterjee. Gulf War Illness Is Associated with Host Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Is Linked to Altered Species Abundance in Veterans from the BBRAIN Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 21(8), 1102. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11354743. (2024). [↩]

- V. Sanchez, B. S. Baksh, K. Cabrera, A. Choudhury, K. Jensen, N. Klimas, A. Galor. Dry Eye Symptoms and Signs in US Veterans With Gulf War Illness. Am J Ophthalmol. 237, 32-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC9035031. (2021). [↩]

- C. G. Zundel, M. H. Krengel, T. Heeren, M. K. Yee, C. M. Grasso, P. A. Janulewicz Lloyd, S. S. Coughlin, K. Sullivan. Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16(6), 949. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC6466358. (2019) [↩] [↩]

- V. Delic, J. Karp, J. Klein, K. J. Stalnaker, K. E. Murray, W. A. Ratliff, C. E. Myers, K. D. Beck, B. A. Citron. Pyridostigmine bromide, chlorpyrifos, and DEET combined Gulf War exposure insult depresses mitochondrial function in neuroblastoma cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 35(12), e22913. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC8678325. (2021). [↩]

- J. N. Meyer, W. K. Pan, I. T. Ryde, T. Alexander, J. C. Klein-Adams, D. S. Ndirangu, M. J. Falvo. Bioenergetic function is decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of veterans with Gulf War Illness. PLoS One. 18(11), e0287412. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10619881. (2024). [↩]

- P. Liu, S. Aslan, X. Li, D. M. Buhner, J. S. Spence, R. W. Briggs, R. W. Haley, H. Lu. Perfusion deficit to cholinergic challenge in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicology. 32(2), 242-246. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC3049842. (2010). [↩]

- N. A. Hubbard, J. L. Hutchison, M. A. Motes, E. Shokri-Kojori, I. J. Bennett, R. M. Brigante, R. W. Haley, B. Rypma. Central Executive Dysfunction and Deferred Prefrontal Processing in Veterans with Gulf War Illness. Clin Psychol Sci. 2(3), 319-327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC4352953. (2014). [↩]

- L. Steele, R. Quaden, S. T. Ahmed, K. M. Harrington, L. M. Duong, J. Ko, E. J. Gifford, R. Polimanti, J. M. Gaziano, M. Aslan, D. A. Helmer, E. R. Hauser; Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program #2006 and the VA Million Veteran Program. Association of deployment characteristics and exposures with persistent ill health among 1990-1991 Gulf War veterans in the VA Million Veteran Program. Environ Health. 23(1), 92. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11520114/. (2024) [↩]

- E. J. Gifford, J. Vahey, E. R. Hauser, et al. Gulf War illness in the Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository: The Kansas and Centers for Disease Control definitions. Life Sci. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10148241/ (2021) [↩]

- R. Toomey, R. Alpern, J. J. Vasterling, D. G. Baker, D. J. Reda, M. J. Lyons, W. G. Henderson, H. K. Kang, S. A. Eisen, F. M. Murphy. Neuropsychological functioning of U.S. Gulf War veterans 10 years after the war. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 15(5), 717-729. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19640317/. (2009) [↩] [↩]

- D. Keating, M. Krengel, J. Dugas, R. Toomey, L. Chao, L. Steele, L. P. Janulewicz, T. Heeren, E. Quinn, N. Klimas, K. Sullivan. Cognitive decrements in 1991 Gulf War veterans: associations with Gulf War illness and neurotoxicant exposures in the Boston Biorepository, Recruitment, and Integrative Network (BBRAIN) cohorts. Environ Health. 22(1), 68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10548744. (2023) [↩]

- H. E. Burzynski, L. P. Reagan. Exposing the latent phenotype of Gulf War Illness: examination of the mechanistic mediators of cognitive dysfunction. Front Immunol. 15, 1403574. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11196646. (2024) [↩]

- S. K. Barth, E. K. Dursa, R. M. Bossarte, A. I. Schneiderman. Trends in brain cancer mortality among U.S. Gulf War veterans: 21 year follow-up. Cancer Epidemiol. 50(Pt A), 22-29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC5824993. (2017) [↩]

- N. A. Hubbard, J. L. Hutchison, M. A. Motes, E. Shokri-Kojori, I. J. Bennett, R. M. Brigante, R. W. Haley, B. Rypma. Central Executive Dysfunction and Deferred Prefrontal Processing in Veterans with Gulf War Illness. Clin Psychol Sci. 2(3), 319-327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC4352953. (2014) [↩]

- D. Keating, M. Krengel, J. Dugas, R. Toomey, L. Chao, L. Steele, L. P. Janulewicz, T. Heeren, E. Quinn, N. Klimas, K. Sullivan. Cognitive decrements in 1991 Gulf War veterans: associations with Gulf War illness and neurotoxicant exposures in the Boston Biorepository, Recruitment, and Integrative Network (BBRAIN) cohorts. Environ Health. 22(1), 68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10548744/. (2023) [↩] [↩]

- E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, J. Vahey, K. J. Sims, J. T. Efird, B. Chesnut, C. Stafford, J. Upchurch, C. D. Williams, D. A. Helmer, E. R. Hauser. Health-Related Quality of Life by Gulf War Illness Case Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(8), 4425. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC9026791. (2022) [↩]

- L. E. Truax, J. J. Huang, K. Jensen, E. V. T. Locatelli, K. Cabrera, H. O. Peterson, N. K. Cohen, S. Mangwani-Mordani, A. Jensen, R. Goldhardt, A. Galor. Pyridostigmine Bromide Pills and Pesticides Exposure as Risk Factors for Eye Disease in Gulf War Veterans. J Clin Med. 12(6), 2407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10059791. (2023) [↩]

- V. Delic, J. Karp, J. Klein, K. J. Stalnaker, K. E. Murray, W. A. Ratliff, C. E. Myers, K. D. Beck, B. A. Citron. Pyridostigmine bromide, chlorpyrifos, and DEET combined Gulf War exposure insult depresses mitochondrial function in neuroblastoma cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 35(12), e22913. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC8678325. (2021) [↩]

- S. T. Ahmed, L. Steele, P. Richardson, S. Nadkarni, S. Bandi, M. Rowneki, K. J. Sims, J. Vahey, E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, T. H. Nguyen, A. Nono Djotsa, D. L. White, E. R. Hauser, H. Chandler, J. M. Yamal, D. A. Helmer. Association of Gulf War Illness-Related Symptoms with Military Exposures among 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans Evaluated at the War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). Brain Sci. 12(3), 321. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC8946608. (2022) [↩]

- E. W. Moffet, S. G. Jones, T. Snyder, B. Riedner, R. M. Benca, T. Juergens. Gulf War veterans exhibit broadband sleep EEG power reductions in regions overlying the frontal lobe. Life Sci. 280, 119702. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC12019881/. (2021) [↩]

- L. E. Truax, J. J. Huang, K. Jensen, E. V. T. Locatelli, K. Cabrera, H. O. Peterson, N. K. Cohen, S. Mangwani-Mordani, A. Jensen, R. Goldhardt, A. Galor. Pyridostigmine Bromide Pills and Pesticides Exposure as Risk Factors for Eye Disease in Gulf War Veterans. J Clin Med. 12(6), 2407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10059791/. (2023) [↩]

- L. L. Chao, K. Sullivan, M. H. Krengel, R. J. Killiany, L. Steele, N. G. Klimas, B. B. Koo. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in Gulf War veterans: a follow-up study. Front Neurosci. 17, 1301066. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10838998/. (2023) [↩] [↩]

- L. Chao. Do Gulf War veterans with high levels of deployment-related exposures display symptoms suggestive of Parkinson’s disease? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 32(4), 503–526. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11892701/. (2019) [↩]

- D. Keating, M. Krengel, J. Dugas, R. Toomey, L. Chao, L. Steele, L. P. Janulewicz, T. Heeren, E. Quinn, N. Klimas, K. Sullivan. Cognitive decrements in 1991 Gulf War veterans: associations with Gulf War illness and neurotoxicant exposures in the Boston Biorepository, Recruitment, and Integrative Network (BBRAIN) cohorts. Environ Health. 22(1), 68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10548744/. (2023 [↩]

- E. Sultana, N. Shastry, R. Kasarla, J. Hardy, F. Collado, K. Aenlle, M. Abreu, E. Sisson, K. Sullivan, N. Klimas, T. J. A. Craddock. Disentangling the effects of PTSD from Gulf War Illness in male veterans via a systems-wide analysis of immune cell, cytokine, and symptom measures. Mil Med Res. 11(1), 2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10759613/. (2024) [↩]

- S. T. Ahmed, L. Steele, P. Richardson, S. Nadkarni, S. Bandi, M. Rowneki, K. J. Sims, J. Vahey, E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, T. H. Nguyen, A. Nono Djotsa, D. L. White, E. R. Hauser, H. Chandler, J. M. Yamal, D. A. Helmer. Association of Gulf War Illness-Related Symptoms with Military Exposures among 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans Evaluated at the War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). Brain Sci. 12(3), 321. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC8946608/. (2022) [↩] [↩]

- J. Vahey, E. J. Gifford, K. J. Sims, B. Chesnut, S. H. Boyle, C. Stafford, J. Upchurch, A. Stone, S. Pyarajan, J. T. Efird, C. D. Williams, E. R. Hauser. Gene-Toxicant Interactions in Gulf War Illness: Differential Effects of the PON1 Genotype. Brain Sci. 11(12), 1558. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8699623/. (2021) [↩]

- R. Toomey, R. Alpern, J. J. Vasterling, D. G. Baker, D. J. Reda, M. J. Lyons, W. G. Henderson, H. K. Kang, S. A. Eisen, F. M. Murphy. Neuropsychological functioning of U.S. Gulf War veterans 10 years after the war. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 15(5), 717-729. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19640317/. (2009 [↩]

- L. Chao. Do Gulf War veterans with high levels of deployment-related exposures display symptoms suggestive of Parkinson’s disease? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 32(4), 503–526. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11892701/. (2019 [↩]

- D. Keating, M. Krengel, J. Dugas, R. Toomey, L. Chao, L. Steele, L. P. Janulewicz, T. Heeren, E. Quinn, N. Klimas, K. Sullivan. Cognitive decrements in 1991 Gulf War veterans: associations with Gulf War illness and neurotoxicant exposures in the Boston Biorepository, Recruitment, and Integrative Network (BBRAIN) cohorts. Environ Health. 22(1), 68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10548744/. (2023) [↩]

- L. L. Chao. Examining the current health of Gulf War veterans with the veterans affairs frailty index. Front Neurosci. 17, 1245811. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10512703/. (2023) [↩]

- Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans. A population-based study. The Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group. JAMA. 277(3), 238-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9005274/. (1997) [↩]

- B. N. Doebbeling, W. R. Clarke, D. Watson, J. C. Torner, R. F. Woolson, M. D. Voelker, D. H. Barrett, D. A. Schwartz. Is there a Persian Gulf War syndrome? Evidence from a large population-based survey of veterans and nondeployed controls. Am J Med. 108(9), 695-704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10924645/. (2000) [↩]

- E. Sultana, N. Shastry, R. Kasarla, J. Hardy, F. Collado, K. Aenlle, M. Abreu, E. Sisson, K. Sullivan, N. Klimas, T. J. A. Craddock. Disentangling the effects of PTSD from Gulf War Illness in male veterans via a systems-wide analysis of immune cell, cytokine, and symptom measures. Mil Med Res. 11(1), 2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10759613/. (2024) [↩]

- J. N. Meyer, W. K. Pan, I. T. Ryde, T. Alexander, J. C. Klein-Adams, D. S. Ndirangu, M. J. Falvo. Bioenergetic function is decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of veterans with Gulf War Illness. PLoS One. 18(11), e0287412. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10619881/. (2024) [↩] [↩]

- L. L. Chao, K. Sullivan, M. H. Krengel, R. J. Killiany, L. Steele, N. G. Klimas, B. B. Koo. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in Gulf War veterans: a follow-up study. Front Neurosci. 17, 1301066. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC10838998/. (2023) [↩]

- L. Chao. Do Gulf War veterans with high levels of deployment-related exposures display symptoms suggestive of Parkinson’s disease? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 32(4), 503–526. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC11892701/. (2019) [↩]

- E. J. Gifford, S. H. Boyle, J. Vahey, K. J. Sims, J. T. Efird, B. Chesnut, C. Stafford, J. Upchurch, C. D. Williams, D. A. Helmer, E. R. Hauser. Health-Related Quality of Life by Gulf War Illness Case Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(8), 4425. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC9026791/. (2022) [↩]