Abstract

Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) in pediatric patients presents significant treatment challenges, particularly for those experiencing debilitating drop seizures. Corpus callosotomy (CC) remains an effective surgical intervention, with total corpus callosotomy (TCC) consistently demonstrating superior seizure control compared to anterior corpus callosotomy (ACC), especially for atonic seizures. Recent advances in minimally invasive techniques, such as laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) and Gamma Knife corpus callosotomy (GK-CC), have shown early promise in achieving seizure reduction with lower complication rates; however, evidence remains limited. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), deep brain stimulation (DBS), and responsive neurostimulation (RNS) devices provide alternative therapeutic options tailored to patient-specific risks and preferences. Surgical innovations aimed at minimizing postoperative complications have further improved patient outcomes. Future treatment options, including precision medicine approaches, hold promise for targeting the genetic underpinnings of epilepsy. This comprehensive review synthesizes current surgical and neuromodulatory treatments for pediatric DRE, emphasizing emerging therapies and strategies to optimize patient outcomes beyond merely targeting physical symptoms.

KeyWords: Epilepsy, Seizures, Corpus Callosotomy, Tonic-Clonic Seizures, Drug-Resistant Epilepsy

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures that result from abnormal electrical activity in the brain1. Seizures present in diverse forms and are broadly categorized as focal or generalized, depending on whether they originate in a specific brain region or affect both hemispheres simultaneously. Generalized seizures include tonic, atonic, myoclonic, absence, and tonic-clonic types, each presenting with distinct physical and neurological symptoms2.

For patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE), particularly those experiencing generalized seizures that do not respond to medications or cannot be treated through resective surgery, corpus callosotomy is considered a viable palliative treatment. This procedure involves severing part or all of the corpus callosum, a major white matter structure that facilitates communication between the two cerebral hemispheres. By disrupting this interhemispheric connection, CC aims to reduce the spread of epileptic activity, decreasing both the frequency and severity of seizures3. Originally developed in the 1940s, the technique has since evolved to include anterior, posterior, and complete callosotomy approaches4.

CC is particularly effective in treating drop attacks, which are sudden, often violent seizures that cause the individual to collapse, posing a significant risk of injury5. Abnormalities in the corpus callosum may contribute to epilepsy, although not all individuals with such anomalies develop seizures, highlighting the complexity of epileptogenesis4. Surgical data indicate that CC can significantly reduce tonic, atonic, and tonic-clonic seizures5. These outcomes underscore the importance of careful patient selection and seizure-type analysis before surgery.

Complete callosotomy tends to yield better seizure control than partial sectioning, although it is associated with a higher risk of complications, including disconnection syndromes and transient neurological deficits6. In contrast, partial callosotomy, often involving the anterior two-thirds of the corpus callosum, is safer but generally less effective. Studies comparing the two approaches have consistently found that complete callosotomy leads to greater seizure reduction and higher family satisfaction, especially in pediatric populations7.

While most patients achieve seizure control with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), approximately one-third develop DRE, defined by the International League Against Epilepsy as failure to achieve seizure freedom with adequate trials of two appropriate AEDs. DRE is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life.

In the pediatric population, drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) affects approximately 30% of children with epilepsy, making it a significant public health concern1. Population-based studies indicate that these children often experience developmental delays, behavioral issues, and cognitive deficits due to uncontrolled seizures and repeated medication exposure. The persistent nature of DRE also imposes substantial emotional and financial burdens on families and healthcare systems.

The development of drug resistance involves multiple mechanisms, including altered drug transport across the blood-brain barrier, changes in neuronal drug targets, and pathological reorganization of neural networks. For example, P-glycoprotein overexpression may reduce AED concentrations in the brain, while target and network alterations can diminish drug efficacy. Ongoing research is also exploring biomarkers that could predict which patients are at risk of developing DRE earlier, potentially guiding more personalized treatment strategies.

Consequently, there has been increasing focus on non-pharmacological interventions, including resective surgery, neuromodulation, and palliative procedures, to achieve seizure reduction and improve quality of life. Understanding the mechanisms underlying resistance and evaluating effective treatment strategies are critical for improving care. This review aims to integrate recent findings on surgical options and alternative treatments for pediatric DRE, emphasizing their efficacy, safety profiles, and appropriate clinical applications.

Methodology

This paper presents a comprehensive narrative review of peer-reviewed studies focusing on DRE in pediatric and, where relevant, adult populations. The review was conducted by identifying articles published between 2016 and 2024. Sources included randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, meta-analyses, and clinical case reports. Articles were systematically identified using academic databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar. The primary search terms included “drug-resistant epilepsy,” “epilepsy surgery,” “corpus callosotomy,” “vagus nerve stimulation,” “transcranial direct current stimulation,” “deep brain stimulation epilepsy,” “responsive neurostimulation epilepsy,” “laser interstitial thermal therapy epilepsy,” and “gamma knife corpus callosotomy.” Additional searches were performed using terms such as “pediatric DRE,” “seizure outcomes,” and “surgical complications.”

Studies were selected based on their relevance to the stated objectives of the review: to synthesize current surgical and neuromodulatory treatments, evaluate their efficacy and safety, and identify emerging therapeutic options. While formal statistical meta-analysis was not performed, data on seizure outcomes, complication rates, and notable findings were extracted and critically summarized to provide a qualitative synthesis of the evidence. Emphasis was placed on studies involving pediatric populations where possible.

Corpus Callosotomy Efficacy

Corpus callosotomy is primarily considered a palliative procedure for generalized epilepsies, especially effective against drop seizures. While it rarely achieves complete seizure freedom, it significantly reduces seizure burden and improves quality of life.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Wu et al. (2023) analyzed 1,644 patients across 49 studies who underwent CC. They reported a complete seizure freedom (SF) rate of 12.38% after at least one year of follow-up, reinforcing that CC is generally not curative. However, the rate of complete SF from drop seizures (DS) was significantly higher, at 61.86%, highlighting CC’s strong efficacy for this particularly debilitating seizure type8.

Comparing the effectiveness of total corpus callosotomy (TCC) versus anterior corpus callosotomy (ACC), Wu et al. (2023) consistently found TCC to be superior. The complete SF rate after TCC was 11.41%, compared to 6.75% after ACC. For drop seizures, TCC showed a substantially higher complete SF rate of 71.52% compared to ACC at 57.11%. Although the confidence intervals for overall SF rates somewhat overlap, the consistent trend strongly favors TCC, especially for the control of drop seizures, indicating its robust palliative effect8.

These findings are further supported by a multicenter study by Roth et al. (2023) on 127 children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) who underwent CC after failed vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). The study demonstrated that complete CC led to at least an 80% reduction in drop attacks for 56% of patients, and at least 50% reduction for 83% of patients. In contrast, anterior CC was less effective, with only 41% achieving >80% reduction in drop attacks and 26% experiencing 50% reduction. For non-drop seizures, complete CC was significantly more effective than anterior CC for a 50% reduction (65% vs. 38%, p=0.013), but overall efficacy for non-drop seizures remained modest, with only 27% achieving >80% reduction9.

Early surgical intervention in children with DRE, including procedures like CC, significantly improves seizure outcomes compared to continued medical therapy. A randomized controlled trial by Dwivedi et al. (2025) compared surgery to continued medical therapy in pediatric DRE patients. At 12 months, 44 of 57 children (77%) in the surgical group were seizure-free, versus only 4 of 59 children (7%) in the medical-therapy group10. This robust statistical significance highlights the strong benefit of timely surgical intervention for children not responding to medication.

Even in patients with underlying metabolic disorders, CC can be a viable surgical option. Na et al. (2025) assessed CC effectiveness in pediatric patients with intractable epilepsy and mitochondrial dysfunction, finding that outcomes were comparable to those in patients without mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting an expanded candidate pool for the procedure11

Surgical and Postoperative Complications

While corpus callosotomy offers substantial clinical benefits, it is an invasive procedure associated with measurable surgical and postoperative risks that must be carefully weighed.

A retrospective review by Motiwala et al. (2024) of 105 patients undergoing first-time open callosotomy from 2005 to 2022 reported an operative complication rate of 6.7%. These complications included three cases of transient pseudomeningocele, three wound infections, and one delayed intraparenchymal hemorrhage. No venous infarcts were observed on postoperative MRI. The mean operative time was 226.76 minutes, and the mean blood loss was 96.67 mL12. These figures indicate that open CC, while generally safe in experienced hands, involves significant operative time and a non-negligible risk of complications, emphasizing the need for careful patient selection.

In the Roth et al. (2023) study of 127 LGS children who underwent CC, permanent morbidity was 1.5%, and mortality was 0%. Among 137 total CC procedures, neurological complications occurred in six cases (4.4%): 4 were transient neurological symptoms (e.g., temporary mutism or hemiparesis), one involved a pericallosal artery infarct, and one was unspecified9. These data confirm that even in high-volume centers, CC carries a small but meaningful risk of permanent neurological deficits.

A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis by Wu et al. (2023) pooled complication rates across 1,644 CC patients, finding an overall general complication rate of 9.9%. Specific neurological and systemic complications included:

- Acute disconnection syndrome (transient neurological issues like mutism or speech impairment): 4.1%

- Hemorrhage or hematoma (risk of life-threatening bleeding): 1.8%

- Infection (e.g., wound, meningitis): 1.5%

- Hydrocephalus (fluid buildup requiring intervention): 0.8%

The overall complication rate of nearly 1 in 10 patients underscores the importance of thoroughly discussing these risks, especially in pediatric or medically fragile individuals8.

In the research article, “Rates and predictors of seizure outcome after corpus callosotomy for drug-resistant epilepsy: a meta-analysis,” Chan et al. identified 1,742 patients from 58 studies to investigate the rates of complete seizure freedom and drop attack freedom after CC. According to Bower et al. (2013), 8.0% experienced mild transient new or worsened hemiparesis, and 2.0% had bone flap infection. According to Fandion-Franky et al. (2000), 10.3% experienced transient lower-extremity weakness, and 2.1% had transient transitory mutism. According to Liang et al. (2007), 5.1% experienced transient urinary incontinence, 3.4% experienced transient apraxia, and 1.7% experienced transient aphasia. According to Rahimi et al. (2007), 5.4% experienced hydrocephalus requiring shunt replacement, 2.7% experienced superior mesenteric artery infarction. According to Tanriverdi et al. (2009), 2.1% experienced lower-extremity weakness, 2.1% experienced transient aphasia, 2.1% experienced aspiration pneumonia, 1.0% experienced epidural hematoma requiring reoperation, 1.0% had bone flap infection with intracranial abscess, 1.0% experienced subgaleal hematoma, 1.0% had skin suture detachment, and 1.0% experienced venous thrombosis13. These results show that, while CC offers substantial clinical benefits in reducing seizure burden, its adoption must be weighed against these known complication risks.

A key postoperative concern is disconnection syndrome. Baumgartner et al. (2023) studied 101 patients undergoing complete CC, finding that transient disconnection syndrome was the most common post-surgical complication, observed in 50% of patients. Importantly, the incidence and severity of disconnection syndrome increased with age: six children aged 0–5 years experienced it (one requiring inpatient rehab), compared to 17 patients aged 6–12 years (12 requiring rehab), 11 aged 13–18 years (seven requiring rehab), and 17 patients older than 18 years (15 requiring rehab)14. This suggests that increased age is associated with a higher risk of developing, and potentially requiring rehabilitation for, disconnection syndromes.

Further surgical complications observed by Baumgartner et al. included one wound infection (resulting in bone flap removal, intravenous antibiotics, and delayed cranioplasty), four cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks (two requiring shunt placement), two acute subdural hemorrhages, one aseptic meningitis, one prolonged intubation, three deep vein thromboses, three exacerbations of swallowing deficits, and one systemic inflammatory response syndrome14. These data reinforce that while CC is highly effective for seizure reduction, complications are a significant consideration, particularly for older patients.

Neuropsychological Outcomes and Long-term Considerations

Beyond immediate surgical complications, CC can lead to significant neuropsychological and behavioral changes, which are critical considerations for long-term patient quality of life.

Parekh and Bapat (2025), in their systematic review of functional outcomes of CC in adults, noted that transient cognitive deficits, including mutism, hemiparesis, and delayed language processing, can occur. Transient mutism was reported in up to 10% of patients following complete callosotomy, particularly when posterior sections are involved. Transient hemiparesis was observed in 3–6% of pediatric patients, typically resolving within days to weeks. While often temporary, these side effects can disrupt recovery and quality of life, especially in younger patients. Cognitive outcomes vary widely and are often poorly standardized in reporting, making long-term neuropsychological effects difficult to predict15. The brain’s adaptability post-surgery is unpredictable, and CC’s interference with interhemispheric communication may have lasting developmental or behavioral impacts in some patients.

A case study by Delawan and Qassim (2023) reported behavioral disinhibition, including impulsivity and social inappropriateness, in a 15-year-old girl following a limited anterior callosotomy for colloid cyst excision16. This illustrates that even partial disconnection can disrupt interhemispheric communication, leading to significant alterations in behavior, particularly in adolescents whose brains are still maturing.

The impact of CC on intelligence quotient (IQ) has also been investigated. Westerhausen and Karud (2018) conducted a meta-analysis on individual participant data, revealing that the effect of surgical CC on IQ depended on presurgery intelligence levels. Patients with above-median presurgery IQ showed a significant mean decrease of 5.44 IQ points, whereas patients with below-median IQ did not show a significant change in IQ scores17. This indicates that CC can negatively affect performance IQ scores, primarily in individuals with at least average pre-surgical IQ.

Beyond IQ, CC has been associated with behavioral disinhibition, executive dysfunction, and changes in attention and processing speed16‘18‘17. Such effects may impact school performance, social interactions, and overall quality of life, emphasizing the importance of age-appropriate neuropsychological monitoring. Standardized assessments before and after surgery can help identify cognitive and behavioral changes, guide interventions, and inform families about potential risks12‘8‘19. Younger patients, particularly those under 5 years, may be more vulnerable to transient post-surgical behavioral disinhibition, whereas adolescents show greater susceptibility to declines in performance IQ8‘17. Certain epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut or generalized epilepsies with multiple seizure types, are associated with higher rates of postoperative ataxia, hemiparesis, or disconnection syndromes8‘9‘20. Prior neurosurgical interventions, including resective procedures or prior partial callosotomy, can also increase the likelihood of complications due to altered anatomy or scar tissue21. Collectively, these findings underscore the need for careful patient selection and consideration of developmental stage when evaluating CC as a treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy in adolescents.

Furthermore, CC is often just one component of a multimodal epilepsy treatment strategy. Roth et al. (2023) reported that among patients who had already failed VNS, 20 children underwent additional surgeries after CC, including 10 cases of CC completion, 8 received deep brain stimulation (DBS), 1 had a frontal lobectomy, and another underwent responsive neurostimulation (RNS)9. This frequent need for further neurosurgical procedures highlights that CC, while effective, may not be a standalone solution for many patients, necessitating a sequential or combinatorial treatment approach. These neuropsychological risks are closely linked to the type of callosotomy performed. Total corpus callosotomy (TCC) generally produces greater seizure reduction, particularly for atonic or “drop” seizures8, but is associated with a higher risk of disconnection syndromes, including cognitive and behavioral changes. Anterior corpus callosotomy (ACC) may be preferable for patients with milder seizure phenotypes or higher susceptibility to neurocognitive complications. Thus, selecting TCC versus ACC requires careful consideration of seizure type, patient age, presurgical cognitive status, and prior treatments to optimize both seizure control and quality of life.

Outcomes following corpus callosotomy (CC) cannot be attributed solely to the type of procedure performed (total vs. anterior). Evidence suggests that the efficacy and risk profile of CC are heavily influenced by patient-specific factors such as underlying epilepsy syndrome, age at surgery, and prior treatments. For example, patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome tend to achieve greater seizure reduction following total CC compared with anterior CC, whereas those with less severe generalized seizures may benefit sufficiently from anterior approaches8. Younger patients may experience different neurocognitive effects compared with adolescents due to ongoing brain maturation17, and prior interventions such as vagus nerve stimulation or multiple antiseizure medications can modify surgical outcomes9‘22. Therefore, stratifying outcomes by syndrome, age, and treatment history provides a more accurate framework for predicting CC effectiveness and guiding clinical decision-making.

Additionally, reoperative neuroimaging may provide important predictors of seizure outcomes following corpus callosotomy. Techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) can assess interhemispheric connectivity and functional network integrity, which may help anticipate the degree of seizure reduction post-surgery. While these methods are still investigational, they have been proposed as adjuncts to standard presurgical evaluation to guide patient selection and surgical planning10. Integrating such imaging-based predictors with clinical factors, including age, epilepsy syndrome, and prior treatments, may improve individualized outcome prediction and reduce the risk of complications.

Alternative Treatments

For patients with DRE, various alternative neuromodulatory treatments exist, offering different risk-benefit profiles compared to corpus callosotomy. However, while these interventions may serve as adjuncts or alternatives to corpus callosotomy, the existing literature is limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous protocols, and lack of large-scale randomized, sham-controlled trials. Therefore, their efficacy relative to more established surgical approaches remains uncertain. In clinical practice, these therapies are often considered on a case-by-case basis, particularly when conventional surgery is contraindicated or has failed10.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

VNS is a minimally invasive, implantable neuromodulation therapy that involves delivering electrical pulses to the vagus nerve. Its antiseizure effect is believed to arise from activation of afferent fibers projecting to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the brainstem, which subsequently influences the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nuclei. This pathway increases cortical norepinephrine and serotonin levels, promoting desynchronization of hypersynchronous neural activity and reducing thalamo-cortical excitability. Over time, chronic VNS has also been shown to enhance neurotrophic signaling and exert anti-inflammatory effects, contributing to progressive seizure reduction. Clinically, stimulation parameters are titrated to balance efficacy and tolerability, typically beginning at 0.25-0.5 mA with 20-30 Hz frequency, 250-500 μs pulse width, and a duty cycle of 30 seconds on and 5 minutes off. Output current is gradually increased as tolerated, often reaching 1.5-2.5 mA, with magnet-activated bursts used for breakthrough seizures.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Mao et al. (2022) focused on VNS therapy for DRE across a broad age range. In the short term, 55.8% of patients experienced a reduction in seizure frequency within the first year. Long-term responses showed that 51.1% maintained a reduction after 1 year. Complete seizure freedom, however, was uncommon, achieved by only 8.2% of patients. Surgical complications, including infection, vocal cord paralysis, and device malfunction, occurred in 6.4% of patients, with lead or generator revision needed in approximately 5%-10% of cases during follow-up22.

Melese et al. (2024) further supported VNS efficacy in their systematic review across 11 studies in pediatric and adult DRE patients, reporting a mean response rate of 56.94%23. This consistent reduction in seizure frequency for more than half of patients suggests VNS provides meaningful seizure control as a sustained treatment modality. Compared to CC, VNS is generally safer with fewer invasive complications, although it is typically less effective at achieving high rates of complete seizure freedom or specific control over drop seizures. It is often considered before more invasive procedures, particularly for patients with generalized or multifocal epilepsy and those for whom surgical risk is a primary concern.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

tDCS is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that delivers low-level electrical current to the scalp. It modulates cortical excitability by shifting resting membrane potentials: anodal stimulation depolarizes neurons to increase excitability, whereas cathodal stimulation hyperpolarizes neurons, reducing cortical activity. This polarity-dependent effect can influence seizure susceptibility by stabilizing hyperexcitable cortical networks or reducing abnormal synchronization. Typical parameters include constant direct currents of 1-2 mA delivered for 20-30 minutes through sponge electrodes placed over the epileptogenic cortex and a contralateral reference site. While the induced electric field is weak, repeated sessions can produce lasting neuroplastic changes in cortical connectivity, potentially lowering seizure frequency.

A single-case study by San-Juan et al. (2018) reported a 28-year-old woman with drug-resistant focal epilepsy achieving complete seizure freedom for 3 months after five 20-minute tDCS sessions over two weeks. Improvements in EEG discharges, alertness, and emotional reactivity were also noted, with no reported complications24. This highlights tDCS as a non-invasive option with minimal risks (e.g., mild tingling, headaches) and promising preliminary results in highly selected cases.

However, a double-blind, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial by Ashrafzadeh et al. (2023) involving 18 pediatric DRE patients treated with daily 20-minute tDCS sessions for five days, showed no statistically significant reduction in EEG markers of epileptic activity. The mean change in discharges was +0.66 pm 38.43 in the tDCS group versus -1.22 pm 14.18 in the control group25. This indicates that, in this study, tDCS did not significantly reduce epileptic activity in children with refractory epilepsy. While tDCS is extremely safe and low-cost, its overall efficacy, particularly in pediatric refractory epilepsy, is not yet definitively proven by robust clinical trials and it is not a validated mainstream treatment. It may have a role as a low-risk adjunct for specific patient populations or in research settings where more invasive treatments are not feasible.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) & Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS)

DBS and RNS are invasive neuromodulation therapies involving the implantation of electrodes. DBS delivers continuous or intermittent electrical stimulation to specific brain targets, while RNS detects and responds to seizure activity by delivering targeted electrical pulses. These therapies are typically used after failure of less invasive treatments due to their invasive nature and associated risks.

Roth et al. (2023) noted that ten children who failed VNS in their cohort received additional neuromodulation, including eight receiving DBS to the centromedian (CM) nucleus of the thalamus and one receiving RNS targeting the CM nucleus, alongside CC completion9. In this cohort, stimulation parameters were individualized according to each patient’s clinical response, and DBS was primarily targeted to the CM thalamus, which is considered effective for generalized seizures. No direct comparison with other DBS targets, such as the anterior nucleus, was made in this study.

While specific outcome data for these interventions were not provided in the Roth et al. study, existing literature confirms that DBS and RNS are highly personalized and are primarily considered after failure of VNS or CC, especially in severe refractory cases such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. They are invasive procedures that carry inherent risks including infection, lead displacement, and hemorrhage. Despite these risks, DBS and RNS can provide significant seizure reduction and improved quality of life in carefully selected patients who have exhausted other options.

Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT)

LITT is a minimally invasive neurosurgical technique that uses laser energy to ablate target brain tissue under real-time MRI guidance. Aum et al. (2023) conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing open craniotomy and LITT approaches for CC in 103 pediatric DRE patients (87% open craniotomy, 13% LITT). LITT for CC offered comparable seizure outcomes to open craniotomy, with 19.8% achieving Modified Engel Class I (seizure-free), 19.8% Class II (rare seizures with major reduction), 40.2% Class III (regular but reduced seizures), and 19.8% Class IV (no significant help). The overall surgical complication rate for the combined cohort was 6% (6/103 patients). Importantly, LITT was associated with a significantly shorter median hospital stay (three days for LITT vs. five days for open craniotomy)26. This suggests LITT is a safe and effective less invasive alternative to open CC, particularly for pediatric patients, with the advantage of reduced hospital stay and potentially lower complication rates.

Further supporting LITT’s efficacy, Mallela et al. (2021) conducted a retrospective case series of ten pediatric patients undergoing MR-guided LITT for CC. They reported promising short-term outcomes: 71% achieved freedom from drop attacks, and 57% experienced improvements in other seizure types. No complications were reported in this series, and the median hospitalization was only two days27. The absence of complications and very short hospital stays highlight LITT’s potential advantages over traditional open surgery, especially for focal epilepsies or discrete lesions requiring ablation, and its growing application in CC for drop seizures.

Gamma Knife Corpus Callosotomy (GK-CC)

Gamma Knife corpus callosotomy (GK-CC) is a non-invasive radiosurgical technique that uses highly focused gamma rays to create a lesion in the corpus callosum. Hamdi et al. (2023) evaluated GK-CC in 19 patients, finding that 68% demonstrated improvement in seizure control. Out of those who improved, three patients (16%) became completely seizure-free, and two (11%) became free of drop seizures and generalized tonic-clonic seizures while still experiencing other seizure types. Mild complications or neurological consequences were observed in seven patients, with one patient experiencing exacerbation of pre-existing cognitive issues and walking difficulties (Lennox-Gastaut) following no improvement in seizures. The median time to improvement after GK-CC was three months, indicating a delayed effect compared to immediate surgical intervention28. GK-CC avoids craniotomy and shows comparable efficacy to open callosotomy in select cases, making it a viable option for fragile patients or those preferring a non-invasive approach, though its delayed effect and potential for cognitive changes require careful monitoring.

| Treatment | Study (Year) | Patient Demographics | Seizure Outcomes | Complication Rate | Notable Findings |

| Corpus Callosotomy (CC) | Roth et al., Epilepsia (2023) | 127 children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome | Permanent morbidity: 1.5%; transient disconnection syndromes (confusion, mutism, motor deficits) not reported separately | Permanent morbidity: 1.5%; transient disconnection syndromes (confusion, mutism, motor deficits) not reported separately | Complete CC is associated with better seizure control than anterior CC. Pediatric-specific evidence supports efficacy with low permanent morbidity |

| Open vs. Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT) CC | Aum et al., Epilepsia (2023) | Pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy | Similar seizure outcomes between open and LITT approaches | Not specified; LITT is associated with fewer intraoperative complications, lower blood loss, and shorter hospital stays | LITT offers a minimally invasive approach with a lower perioperative burden, comparable seizure control to open surgery |

| LITT CC | Mallela et al., Epilepsia Open (2021) | 10 pediatric patients with drop attacks | MR-guided LITT callosotomy is safe and effective | No major complications reported; transient headache, mild edema possible | Demonstrated feasibility and safety of LITT for pediatric drop attacks; limited cohort size |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Mao et al., Neuromodulation (2022) | Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy | ≥50% seizure reduction: 45–65% | Mild adverse events: transient voice changes, cough; no major permanent complications | VNS is a safe and effective therapy for pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy; efficacy varies with seizure type |

| Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) | San-Juan et al., Frontiers in Neurology (2018) | 28-year-old female with focal cortical dysplasia | Seizure frequency reduced from 10-15/day to 1/month at 1 year | Mild scalp irritation, transient headache | Single-patient report; promising but extremely limited evidence for tDCS efficacy |

| Gamma Knife Corpus Callosotomy (GK-CC) | Hamdi et al., Neurosurgery | 19 patients (mixed pediatric/adult) undergoing GK-CC between 2005 and 2017 | 68% showed seizure improvement; 16% became seizure-free | No permanent complications except 1 patient with worsening pre-existing cognitive/motor deficits | GK-CC shows potential as a non-invasive alternative; small, heterogeneous cohort; delayed effect typical of radiosurgery; careful selection and long-term follow-up needed |

Table 1 | Comparative overview of key studies examining corpus callosotomy (CC) and alternative interventions, including vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). The table summarizes treatment type, study details (year and citation), patient demographics, seizure outcomes, complication rates, and notable findings from each study.

Discussion

Based on the research articles and case studies analyzed in this comprehensive review, callosotomies remain an effective technique for palliative seizure control in drug-resistant epilepsy, particularly for debilitating drop seizures. The superior efficacy and reliability of TCC over ACC in improving patient outcomes have been consistently demonstrated8‘9. Furthermore, the evidence strongly supports that surgical interventions, including CC, are significantly more effective than medication alone for pediatric DRE, as highlighted by Dwivedi et al. (2018), who found 77% of surgical patients seizure-free at 12 months compared to only 7% on continued medical therapy10.

While CC offers substantial benefits, the procedure is associated with various potential drawbacks and complications, including disconnection syndromes, neurological deficits, ventricular herniation, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. However, surgical innovations and meticulous techniques can significantly mitigate these risks. Innovative microsurgical techniques, such as balloon-assisted approaches described by Paolini et al., have demonstrated precise fiber separation in small cranial windows during lesion surgeries. While promising, these methods have not yet been evaluated in epilepsy-specific corpus callosotomy cohorts, and their potential to reduce CC-specific disconnection syndromes remains hypothetical29. This technique resulted in no observed disconnection syndromes or new permanent deficits in their series, suggesting a less impactful approach.

Ventricular herniation can be minimized by limiting entry into the ventricular system, as suggested by Darwish et al. (2017) in their discussion of surgical nuances for palliative epilepsy surgery30. To avoid CSF leakage, the “curtain-fall” technique, described by Giordano et al. (2017), involves harvesting and stitching the periosteum to the dura opposite the drain tube before its removal31. This creates a natural patch that falls into place, sealing the hole and promoting wound healing, thereby preventing CSF leakage. While this approach has been effective in cranial procedures generally, its efficacy in corpus callosotomy-specific cases has not been directly evaluated.

Additionally, Uda et al. (2012) emphasized the vital importance of preserving the pericallosal veins and cingulate gyrus to limit venous infarction and vascular injuries32. Minimizing the retraction of cortical tissue, especially around the cingulate gyrus, and employing atraumatic operative techniques will reduce the risk of compressing or stretching veins, thus lowering the chance of venous outflow disruption.

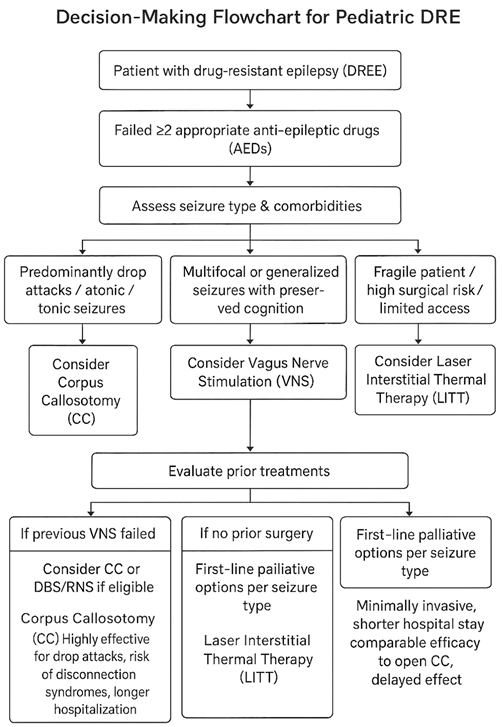

Despite the proven efficacy of callosotomies, it is crucial to acknowledge that in certain cases, alternative treatments may be more appropriate or complementary. A multidisciplinary approach and shared decision-making with families are paramount in selecting the optimal treatment pathway, considering seizure type, patient age, comorbidities, prior treatment failures, and risk tolerance.

Choosing the right alternative treatment for DRE in pediatric patients involves a careful, multidisciplinary approach, tailoring interventions to the specific type of epilepsy, patient characteristics, and family preferences. For patients without a resectable epileptogenic focus or those seeking a less invasive option, Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) is a viable starting point. This reversible neuromodulation therapy is generally well-tolerated and can offer long-term seizure reduction, even if complete seizure freedom is less common than with some surgical procedures. It’s often considered before more invasive interventions, particularly for generalized or multifocal epilepsy.

When a corpus callosotomy is deemed necessary but minimizing invasiveness is crucial, Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT) or Gamma Knife Corpus Callosotomy (GK-CC) may serve as alternative approaches to traditional open surgery. LITT, a minimally invasive option, has shown seizure outcomes that can be comparable to open CC, particularly for drop seizures, with potential benefits of shorter hospital stays and fewer complications. GK-CC, which avoids a craniotomy altogether, may be considered for fragile patients or those with access to specialized radiosurgical centers; however, its seizure control effects are typically delayed, and current evidence is limited to small, heterogeneous cohorts. While both LITT and GK-CC generally have mild complication rates, close monitoring for cognitive effects is essential, especially with GK-CC.

In cases where established interventions are not suitable or have been exhausted, other options exist. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) is an extremely safe and low-cost, non-invasive treatment. However, its effectiveness, particularly in pediatric DRE, is not yet consistently proven, as highlighted by studies like Ashrafzadeh et al. (2023)25. Therefore, tDCS is currently approached with caution and primarily considered within research settings or for highly selective cases where patients cannot undergo more established treatments. Finally, for patients with severe DRE, such as those with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, who have exhausted less invasive therapies, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) or Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) may be considered. These are highly personalized and invasive options, most appropriate when precise targeting of epileptogenic networks is feasible. It’s important to note that these procedures carry risks, including hemorrhage, infection, and lead migration, requiring a thorough risk-benefit assessment before implementation.

An important but underexplored factor in treatment selection for drug-resistant epilepsy is the patient’s underlying genetic mutation. Variants in genes such as SCN1A, SCN8A, and STXBP1 are known to influence both disease severity and response to therapy1. For instance, patients with SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome may respond poorly to sodium channel-blocking antiseizure medications, which can paradoxically worsen seizures, whereas other interventions such as VNS or CC may be comparatively more effective33. Despite the potential clinical relevance, the studies included in this review largely do not stratify outcomes based on underlying mutation, limiting the ability to personalize treatment recommendations. Future research should aim to integrate genetic information into treatment planning to optimize outcomes and minimize adverse effects.

Despite the significant progress in surgical techniques and neuromodulatory therapies for DRE, many patients, especially those with generalized or multifocal seizure patterns, remain without curative options. Ongoing research and emerging technologies hold promise for more targeted, safer, and potentially curative therapies in the future.

One highly targeted focus of future directions in DRE treatment is the application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a powerful tool that allows scientists to precisely alter specific DNA sequences. This precision offers the potential to treat genetic diseases by correcting the underlying genetic causes of disorders such as epilepsy, rather than merely targeting the physical symptoms. Unlike medications or other surgical techniques, CRISPR offers the promise of a one-time treatment with permanent effects. If successful, this could fundamentally prevent seizures from developing or progressing.

Recent advancements highlight the clinical feasibility of in vivo CRISPR delivery. A notable milestone was the first-ever in vivo personalized CRISPR therapy delivered for an infant diagnosed with CPS1 deficiency, a fatal urea cycle disorder. The infant received escalating doses delivered via lipid nanoparticles directly to the liver with no serious safety concerns, alongside early improvements including greater tolerance to normal protein intake, reduced medication dependency, and progress in developmental milestones34. This marks a major step forward in personalized CRISPR editing directly within the body, pushing gene-editing potential in treating ultra-rare disorders.

While CRISPR is not yet approved for treating epilepsy, many forms of DRE, especially those involving mutations in genes such as SCN1A, SCN8A, or STXBP1, are genetically mediated. As precision medicine advances, future research should focus on evaluating the safety, efficacy, and delivery of CRISPR-based strategies for these genetic epilepsies. Such efforts may eventually complement existing therapies by targeting disease mechanisms at the molecular level, moving the field closer to disease-modifying, not merely symptomatic, treatments. Beyond gene editing, future research also includes developing advanced imaging techniques for more precise epileptogenic zone localization, identifying novel biomarkers for predicting treatment response, and exploring new targeted drug therapies to address the underlying pathological mechanisms of DRE.

Discussion

Based on the research articles and case studies analyzed in this comprehensive review, callosotomies remain an effective technique for palliative seizure control in drug-resistant epilepsy, particularly for debilitating drop seizures. The superior efficacy and reliability of TCC over ACC in improving patient outcomes have been consistently demonstrated8‘9. Furthermore, the evidence strongly supports that surgical interventions, including CC, are significantly more effective than medication alone for pediatric DRE, as highlighted by Dwivedi et al. (2018), who found 77% of surgical patients seizure-free at 12 months compared to only 7% on continued medical therapy10.

While CC offers substantial benefits, the procedure is associated with various potential drawbacks and complications, including disconnection syndromes, neurological deficits, ventricular herniation, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. However, surgical innovations and meticulous techniques can significantly mitigate these risks. Innovative microsurgical techniques, such as balloon-assisted approaches described by Paolini et al., have demonstrated precise fiber separation in small cranial windows during lesion surgeries. While promising, these methods have not yet been evaluated in epilepsy-specific corpus callosotomy cohorts, and their potential to reduce CC-specific disconnection syndromes remains hypothetical29. This technique resulted in no observed disconnection syndromes or new permanent deficits in their series, suggesting a less impactful approach.

Ventricular herniation can be minimized by limiting entry into the ventricular system, as suggested by Darwish et al. (2017) in their discussion of surgical nuances for palliative epilepsy surgery30. To avoid CSF leakage, the “curtain-fall” technique, described by Giordano et al. (2017), involves harvesting and stitching the periosteum to the dura opposite the drain tube before its removal35. This creates a natural patch that falls into place, sealing the hole and promoting wound healing, thereby preventing CSF leakage. While this approach has been effective in cranial procedures generally, its efficacy in corpus callosotomy-specific cases has not been directly evaluated.

Additionally, Uda et al. (2012) emphasized the vital importance of preserving the pericallosal veins and cingulate gyrus to limit venous infarction and vascular injuries32. Minimizing the retraction of cortical tissue, especially around the cingulate gyrus, and employing atraumatic operative techniques will reduce the risk of compressing or stretching veins, thus lowering the chance of venous outflow disruption.

Despite the proven efficacy of callosotomies, it is crucial to acknowledge that in certain cases, alternative treatments may be more appropriate or complementary. A multidisciplinary approach and shared decision-making with families are paramount in selecting the optimal treatment pathway, considering seizure type, patient age, comorbidities, prior treatment failures, and risk tolerance.

Choosing the right alternative treatment for DRE in pediatric patients involves a careful, multidisciplinary approach, tailoring interventions to the specific type of epilepsy, patient characteristics, and family preferences. For patients without a resectable epileptogenic focus or those seeking a less invasive option, Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) is a viable starting point. This reversible neuromodulation therapy is generally well-tolerated and can offer long-term seizure reduction, even if complete seizure freedom is less common than with some surgical procedures. It’s often considered before more invasive interventions, particularly for generalized or multifocal epilepsy.

When a corpus callosotomy is deemed necessary but minimizing invasiveness is crucial, Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT) or Gamma Knife Corpus Callosotomy (GK-CC) may serve as alternative approaches to traditional open surgery. LITT, a minimally invasive option, has shown seizure outcomes that can be comparable to open CC, particularly for drop seizures, with potential benefits of shorter hospital stays and fewer complications. GK-CC, which avoids a craniotomy altogether, may be considered for fragile patients or those with access to specialized radiosurgical centers; however, its seizure control effects are typically delayed, and current evidence is limited to small, heterogeneous cohorts. While both LITT and GK-CC generally have mild complication rates, close monitoring for cognitive effects is essential, especially with GK-CC.

In cases where established interventions are not suitable or have been exhausted, other options exist. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) is an extremely safe and low-cost, non-invasive treatment. However, its effectiveness, particularly in pediatric DRE, is not yet consistently proven, as highlighted by studies like Ashrafzadeh et al. (2023)25. Therefore, tDCS is currently approached with caution and primarily considered within research settings or for highly selective cases where patients cannot undergo more established treatments. Finally, for patients with severe DRE, such as those with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, who have exhausted less invasive therapies, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) or Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) may be considered. These are highly personalized and invasive options, most appropriate when precise targeting of epileptogenic networks is feasible. It’s important to note that these procedures carry risks, including hemorrhage, infection, and lead migration, requiring a thorough risk-benefit assessment before implementation.

An important but underexplored factor in treatment selection for drug-resistant epilepsy is the patient’s underlying genetic mutation. Variants in genes such as SCN1A, SCN8A, and STXBP1 are known to influence both disease severity and response to therapy1. For instance, patients with SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome may respond poorly to sodium channel-blocking antiseizure medications, which can paradoxically worsen seizures, whereas other interventions such as VNS or CC may be comparatively more effective33. Despite the potential clinical relevance, the studies included in this review largely do not stratify outcomes based on underlying mutation, limiting the ability to personalize treatment recommendations. Future research should aim to integrate genetic information into treatment planning to optimize outcomes and minimize adverse effects.

Despite the significant progress in surgical techniques and neuromodulatory therapies for DRE, many patients, especially those with generalized or multifocal seizure patterns, remain without curative options. Ongoing research and emerging technologies hold promise for more targeted, safer, and potentially curative therapies in the future.

One highly targeted focus of future directions in DRE treatment is the application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a powerful tool that allows scientists to precisely alter specific DNA sequences. This precision offers the potential to treat genetic diseases by correcting the underlying genetic causes of disorders such as epilepsy, rather than merely targeting the physical symptoms. Unlike medications or other surgical techniques, CRISPR offers the promise of a one-time treatment with permanent effects. If successful, this could fundamentally prevent seizures from developing or progressing.

Recent advancements highlight the clinical feasibility of in vivo CRISPR delivery. A notable milestone was the first-ever in vivo personalized CRISPR therapy delivered for an infant diagnosed with CPS1 deficiency, a fatal urea cycle disorder. The infant received escalating doses delivered via lipid nanoparticles directly to the liver with no serious safety concerns, alongside early improvements including greater tolerance to normal protein intake, reduced medication dependency, and progress in developmental milestones34. This marks a major step forward in personalized CRISPR editing directly within the body, pushing gene-editing potential in treating ultra-rare disorders.

While CRISPR is not yet approved for treating epilepsy, many forms of DRE, especially those involving mutations in genes such as SCN1A, SCN8A, or STXBP1, are genetically mediated. As precision medicine advances, future research should focus on evaluating the safety, efficacy, and delivery of CRISPR-based strategies for these genetic epilepsies. Such efforts may eventually complement existing therapies by targeting disease mechanisms at the molecular level, moving the field closer to disease-modifying, not merely symptomatic, treatments. Beyond gene editing, future research also includes developing advanced imaging techniques for more precise epileptogenic zone localization, identifying novel biomarkers for predicting treatment response, and exploring new targeted drug therapies to address the underlying pathological mechanisms of DRE.

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely express my gratitude to my mentor, Christopher Lee, for his invaluable support and guidance throughout the development of this paper. His expertise in providing structural direction and assistance with formatting was critical to the clarity and coherence of the final manuscript. I am grateful for his time, thoughtful feedback, and continued encouragement.

References

- Epilepsy. (2017, January 19). Epilepsy. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17636-epilepsy [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Types of seizures: Epilepsy. (2024, August 21). Types of seizures: Epilepsy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/about/types-of-seizures.html. [↩]

- Unterberger, I., Mietsch, S., Brunner, C., Baumgartner, C., & Leutmezer, F. (2016). Corpus callosum and epilepsies. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy, 35(0), xxx–xxx. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2016.03.013. [↩]

- Spencer, S. S. (1988). Corpus callosum section and other disconnection procedures for medically intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia, 29(Suppl. 2), S85–S99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05802.x. [↩] [↩]

- Gates, J. R., Rosenfeld, W. E., Maxwell, R. E., & Lyons, R. E. (1987). Response of multiple seizure types to corpus callosum section. Epilepsia, 28(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03618.x. [↩] [↩]

- Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Sharan, A., Nei, M., & Sperling, M. R. (2008). Corpus callosotomy. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, 13(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.04.020. [↩]

- Wong, T.-T., Kwan, S.-Y., Chang, K.-P., Hsiu-Mei, W., Yang, T.-F., Chen, Y.-S., & Yi-Yen, L. (2006). Corpus callosotomy in children. Child’s Nervous System: ChNS, 22(8), 999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-006-0133-4. [↩]

- Wu, X., Ou, S., Zhang, H., Zhen, Y., Huang, Y., Wei, P., & Shan, Y. (2023). Long-term follow-up seizure outcomes after corpus callosotomy: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain and Behavior, 13(4), e2964. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2964. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Roth, J., et al. Added value of corpus callosotomy following vagus nerve stimulation in children with Lennox‑Gastaut syndrome: A multicenter, multinational study. Epilepsia, 64(9), 2274–2285, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17796 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Dwivedi, R., Ramanujam, B., Chandra, P. S., Sapra, S., Gulati, S., Kalaivani, M., Garg, A., Bal, C. S., Tripathi, M., Dwivedi, S. N., Sagar, R., Sarkar, C., & Tripathi, M. (2017). Surgery for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in Children. The New England journal of medicine, 377(17), 1639–1647. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1615335 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Na, J.-, et al. (2025). Effective application of corpus callosotomy in pediatric patients. Brain Disorders, 17, Article 100176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dscb.2024.100176. [↩]

- Motiwala, M., Tambi, S., Motiwala, A., Dacus, M., Troy, C., Osorno‑Cruz, C., & Einhaus, S. (2024). Corpus callosotomy for intractable epilepsy: A contemporary series of operative factors and the overall complication rate. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 34(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2024.8.peds2460 [↩] [↩]

- Chan, A. Y., Rolston, J. D., Lee, B., Vadera, S., & Englot, D. J. Rates and predictors of seizure outcome after corpus callosotomy for drug‑resistant epilepsy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1193–1202, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.12.jns172331 [↩]

- Baumgartner, J. E. Palliation for catastrophic nonlocalizing epilepsy: A retrospective case series of complete corpus callosotomy at a single institution. Pediatrics, 152(6), e2023001234, 2023 [↩] [↩]

- Parekh, S., & Bapat, D. A. Functional outcomes in adults following corpus callosotomy: A systematic review. Brain Disorders, 17, Article 100176, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dscb.2024.100176 [↩]

- Delawan, M., & Qassim, A. Behavioral disinhibition following corpus callosotomy done for colloid cyst excision in a 15‑year‑old girl: A case report and literature review. Surgical Neurology International, 14(48), 48, 2023, https://di.org/10.25259/sni_9_2023 [↩] [↩]

- Westerhausen, R., & Karud, C. M. R. Callosotomy affects performance IQ: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. Neuroscience Letters, 665, 43–47, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.040 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Baumgartner, J. E. (2023). Palliation for catastrophic nonlocalizing epilepsy: A retrospective case series of complete corpus callosotomy at a single institution. Pediatrics, 152(6), e2023001234. [↩]

- Na, J.‑, et al. (2025). Effective application of corpus callosotomy in pediatric patients. Brain Disorders, 17, Article 100176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dscb.2024.100176 [↩]

- Asadi‑Pooya, A. A., Sharan, A., Nei, M., & Sperling, M. R. (2008). Corpus callosotomy. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, 13(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.04.020 [↩]

- Wong, T.‑T., Kwan, S.‑Y., Chang, K.‑P., Hsiu‑Mei, W., Yang, T.‑F., Chen, Y.‑S., & Yi‑Yen, L. (2006). Corpus callosotomy in children. Child’s Nervous System: ChNS, 22(8), 999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381‑006‑0133‑4 [↩]

- Mao, H., Chen, Y., Ge, Q., Ye, L., & Cheng, H. (2022). Short‑ and long‑term response of vagus nerve stimulation therapy in drug‑resistant epilepsy: A systematic review and meta‑analysis. Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society, 25(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.13509 [↩] [↩]

- Melese, D. M., Aragaw, A., & Mekonen, W. (2024). The effect of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) on seizure control, cognitive function, and quality of life in individuals with drug‑resistant epilepsy: A systematic review article. Epilepsia Open, 9(6), 2101–2111. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.13066 [↩]

- San‑Juan, D., Sarmiento, C. I., González, K. M., & Orenday Barraza, J. M. (2018). Successful treatment of a drug‑resistant epilepsy by long‑term transcranial direct current stimulation: A case report. Frontiers in Neurology, 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00065 [↩]

- Ashrafzadeh, F., et al. (2023). Therapeutical impacts of transcranial direct current stimulation on drug‑resistant epilepsy in pediatric patients: A double‑blind parallel‑group randomized clinical trial. Epilepsy Research, 192, 106–117 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Aum, D. J., Reynolds, R. A., McEvoy, S., Tomko, S., Zempel, J., Roland, J. L., & Smyth, M. D. (2023). Surgical outcomes of open and laser interstitial thermal therapy approaches for corpus callosotomy in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia, 64(9), 2274–2285. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17679 [↩]

- Mallela, A. N., Hect, J. L., Abou‑Al‑Shaar, H., Akwayena, E., & Abel, T. J. (2022). Stereotactic laser interstitial thermal therapy corpus callosotomy for the treatment of pediatric drug‑resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia Open, 7(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12559 [↩]

- Hamdi, H., Boissonneau, S., Valton, L., McGonigal, A., Bartolomei, F., & Regis, J. (2023). Radiosurgical corpus callosotomy for intractable epilepsy: Retrospective long‑term safety and efficacy assessment in 19 patients and literature review. Neurosurgery, 93(1), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000002394 [↩]

- Paolini, S., Severino, R., Ciavarro, M., Missori, P., Cardarelli, G., & Mancarella, C. (2023). Balloon‑assisted corpus callosotomy: Reducing the impact of transcallosal approaches. Operative Neurosurgery, 24(3), e155–e159. https://doi.org/10.1227/ons.0000000000000514 [↩] [↩]

- Darwish, A., Radwan, H., Fayed, Z., Mounir, S. M., & Hamada, S. (2022). Surgical nuances in corpus callosotomy as a palliative epilepsy surgery. Surgical Neurology International, 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.25259/sni_7_2022 [↩] [↩]

- Giordano, M., Gallieni, M., Samii, M., & Samii, A. (2024). “Curtain‑fall” technique for cerebrospinal fluid leak prevention after removal of intradural drainage: Technical note—application in chronic subdural hematoma surgery. Neurosurgical Review, 47(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143‑024‑02412‑1 [↩]

- Uda, T., Kunihiro, N., Umaba, R., Koh, S., Kawashima, T., Ikeda, S., Ishimoto, K., & Goto, T. (2021). Surgical aspects of corpus callosotomy. Brain Sciences, 11(12), 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11121608 [↩] [↩]

- Unterberger, I., Mietsch, S., Brunner, C., Baumgartner, C., & Leutmezer, F. (2016). Corpus callosum and epilepsies. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy, 35(0), xxx–xxx. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2016.03.013 [↩] [↩]

- Musunuru, K., Grandinette, S. A., Wang, X., Hudson, T. R., Briseno, K., Berry, A. M., Hacker, J. L., Hsu, A., Silverstein, R. A., Hille, L. T., Ogul, A. N., Robinson‑Garvin, N. A., Small, J. C., McCague, S., Burke, S. M., Wright, C. M., Bick, S., Indurthi, V., Sharma, S., Jepperson, M., Vakulskas, C. A., Collingwood, M., Keogh, K., Jacobi, A., Sturgeon, M., Brommel, C., Schmaljohn, E., Kurgan, G., Osborne, T., Zhang, H., Kinney, K., Rettig, G., Barbosa, C. J., Semple, S. C., Tam, Y. K., Lutz, C., George, L. A., Kleinstiver, B. P., Liu, D. R., Ng, K., Kassim, S. H., Giannikopoulos, P., Alameh, M.‑G., Urnov, F. D., & Ahrens‑Nicklas, R. C. (2025). Patient‑specific in vivo gene editing to treat a rare genetic disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 392(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2504747 [↩] [↩]

- Giordano, M., Gallieni, M., Samii, M., & Samii, A. (2024). “Curtain‑fall” technique for cerebrospinal fluid leak prevention after removal of intradural drainage: Technical note—application in chronic subdural hematoma surgery. Neurosurgical Review, 47(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143‑024‑02412‑1 [↩]