Abstract

This study investigates how prior altruistic behavior (e.g., donating or volunteering) affects emotional justifications for spending among Generation Z, with a particular focus on guilt and moral licensing. Moral licensing is the psychological tendency to justify indulgent behavior after engaging in virtuous acts. Targeting individuals aged 15–22—a group frequently targeted by marketing yet understudied in behavioral economics—this research explores whether charitable actions prompt indulgent financial decisions, and how this varies by gender, developmental stage, and financial knowledge. Using a cross-sectional mixed-methods design, data were collected via anonymous online surveys (N=37) combining Likert-scale items, hypothetical financial scenarios, and open-ended responses. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling from school and social media networks. Quantitative data were analyzed with descriptive statistics, t-tests, and correlations in Jamovi, while qualitative data were thematically coded using inter-rater agreement (Cohen’s κ = 0.87). Results revealed that 62% of participants reported guilt after non-essential purchases, and 54% admitted using prior good deeds to justify indulgence. Notably, female respondents were significantly more likely to report guilt (72% vs. 30% of males; Cohen’s d = 0.63, p < .05). Additionally, cash donors exhibited more post-altruism indulgence (70.27%) than volunteers (29.73%). These findings suggest that guilt may paradoxically enable, rather than inhibit, indulgent spending via moral licensing. Implications include the importance of integrating emotional awareness into youth financial literacy programs, policy design, and behavioral economics models that better reflect the lived experiences of young consumers.

Keywords: behavioral economics, Gen Z, moral licensing, guilt, emotional spending

Introduction

“I knew I shouldn’t have bought the iced coffee,” a 17-year-old respondent admitted. “But I studied all night—I deserved it.”

This seemingly casual statement encapsulates the essence of moral licensing, a concept in behavioral economics that proposes individuals may feel justified in making indulgent or unnecessary decisions after engaging in a morally positive act. While this phenomenon has been primarily studied in adult populations (Monin & Miller, 2001), its relevance among younger individuals—particularly adolescents and emerging adults—remains underexamined. This study therefore seeks to explore a timely and important question: Does moral licensing influence financial decision-making among adolescents and young adults—and if so, how?

Generation Z, represented in this study by individuals aged 15 to 22, has grown up in a context defined by digital saturation, social comparison, and performance-based validation. For this demographic, financial decisions are rarely made in isolation from emotional and social influences. Instead, purchasing behavior is often driven by internal justifications, perceived effort, and even guilt. Although moral licensing has been widely documented in adult consumer behavior, its presence in youth financial habits—particularly how it interacts with emotions such as guilt and self-reward—has not been sufficiently explored.

With this gap in mind, the present study set out to investigate the intersection of moral psychology and adolescent financial behavior. Specifically, it aimed to:

- Measure how frequently teenagers experience guilt following non-essential purchases;

- Examine whether prior prosocial behavior (e.g., donating or volunteering) is used to justify indulgent spending;

- Identify emotional and behavioral patterns that may signal the operation of moral licensing in youth financial decision-making.

To address these questions, a cross-sectional mixed-methods approach was employed, using an online survey distributed to individuals aged 15–22. Quantitative data were gathered through Likert-scale and multiple-choice items to capture measurable patterns, while qualitative insights were derived from open-ended written reflections, offering a deeper view into the emotional and cognitive dimensions of participants’ spending choices.

While the findings offer meaningful initial insight into this understudied area, several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size (N=37) was small and non-random, limiting the generalizability of results. Moreover, the overrepresentation of high school students, many of whom may associate academic effort with personal merit, introduces a potential selection bias. This may have skewed responses—particularly those referencing guilt related to school performance or the use of academic labor as a means of justifying indulgent purchases.

Literature Review

The phenomenon of moral licensing has captured significant attention in behavioral science. At its core, moral licensing allows people to justify self-indulgent or even questionable choices by “cashing in” on previous good deeds.1 showed how individuals who took a stand for equality in one context were, paradoxically, more likely to act with bias in subsequent decisions. Their research launched two main models:

Moral credentials: Past moral behavior shifts how we see our next actions—we’re less likely to judge ourselves harshly.

Moral credits: Good acts are like deposits in a moral bank; we feel entitled to subsequent lapses.

In consumer behavior, these effects have serious real-world stakes.2 found that participants who pictured themselves doing good were more likely to buy luxuries later.3 observed that choosing eco-friendly products could “license” later cheating, implying moral “credit” accrued in one domain spills into unrelated decisions.

More recent studies dive into the emotional rationalizations behind these licensing effects.4 found that people under stress were particularly prone to justifying indulgence with “I deserve a treat” reasoning. Teens—frequently stressed by school and social life—may be especially vulnerable here. My own qualitative results echo this: students often justified bubble tea or coffee after “good” acts or tough days.5 argued that licensing is not just about justifying a single choice, but preserving one’s self-image. For adolescents, who are still building identity, the urge to see themselves as “good people” can lead to creative justifications for spending—even if it contradicts long-term goals.

Adolescent consumer habits add their own complications. According to6, teens are especially susceptible to impulse purchases driven by emotion or social validation. Their growing independence often outpaces their financial literacy—fertile ground for self-justification and post-purchase regret.

Emotions matter after spending, too. Guilt is a classic post-purchase emotion, especially among young spenders.7 highlight how guilt and regret surface most often when purchases clash with one’s values. This study supports that: 62% of respondents felt guilt after non-essential buys, and guilt was more common after altruistic acts were used as a “license.”

The digital world only intensifies these patterns. Social media culture encourages sharing purchases, celebrating treats, and showcasing generosity. As8 point out, this performative aspect reinforces the idea that indulgence after “earning it” isn’t just normal, but rewarded by peers. However, most of researches is based on adult behavior and there is a current gap in empirical research on teens.

In summary, established research confirms that moral licensing isn’t just an adult phenomenon. Its interplay with stress, self-image, and digital peer culture is likely shaping teen spending in subtle yet important ways. This paper aims to fill a research gap by focusing on these patterns in real Gen Z choices, blending emotional insight and behavioral economics.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employed a cross-sectional mixed-methods design to examine how moral licensing may influence financial decision-making among Generation Z. The approach combined quantitative data (Likert scales, multiple choice) with qualitative data (open-ended responses) to explore both trends and personal insights. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through an online survey composed of structured and open-ended items. Due to exploratory nature, inferential testing is limited, but descriptive trends and coded themes were analyzed.

Participants

The study consisted of 37 participants aged 15–22, with 20 identifying as female, 15 as male, and 2 as non-binary. This age range was selected to encompass both late adolescence and emerging adulthood, two adjacent developmental stages where financial independence begins to take shape and personal ethics play a formative role. Including participants across this span enabled a richer exploration of how prosocial behavior and emotional reasoning evolve in tandem with financial autonomy. Participants were recruited through digital outreach, including student networks, school platforms, and social media groups frequented by teens and young adults. This age range was selected to capture a developmental period marked by increasing financial autonomy, evolving identity formation, and heightened sensitivity to social and ethical norms—factors that make this group especially relevant to the study of moral licensing and consumer behavior. The age range of 15–22 includes both adolescents and young adults, which can encompass significantly different stages of cognitive, emotional, and financial development. Demographic data collected included age and gender identity

Data Collection

The study utilized a 12-item online survey consisting of 10 closed-ended and 2 open-ended questions, detailed in the appendix. The survey was designed to assess emotional responses and financial behaviors among Gen Z participants, with a particular focus on guilt, justification, and spending decisions following prosocial actions. Drawing from established psychological and behavioral economics literature, the instrument adapted key constructs from validated multi-item scales to suit the study’s scope and demographic.

The survey was organized into three sections:

Section 1: Demographics

- Age:

- ☐ 13–14

- ☐ 15–16

- ☐ 17–18

- ☐ 19–20

- Gender:

- ☐ Female

- ☐ Male

- ☐ Non-binary / Prefer not to say

Section 2: Spending Emotions and Financial Decisions

- How guilty do you feel after spending on non-essential items (e.g., drinks, makeup, apps)?

(1 = Not guilty at all, 5 = Extremely guilty)- ☐ 1

- ☐ 2

- ☐ 3

- ☐ 4

- ☐ 5

- Which emotions do you most often feel after spending on non-essential items? (Select up to 2)

- ☐ Regret

- ☐ Satisfaction

- ☐ Guilt

- ☐ Excitement

- ☐ Indifference

- ☐ Anxiety

- If you unexpectedly received $100, how would you most likely use it?

- ☐ Spend it on something fun

- ☐ Save it in a bank or cash

- ☐ Invest it

- ☐ Pay off any debt or money owed

- How would you react if an app helped you invest money but charged hidden fees?

- ☐ I’d feel tricked and stop using it

- ☐ I’d be annoyed but keep using it

- ☐ I wouldn’t mind as long as I made money

- ☐ I’m not sure

- Would you purchase optional insurance for a $6 concert ticket in case you had to cancel?

- ☐ Yes

- ☐ No

- ☐ Depends on my mood or situation

- Do you agree with the statement: “$5 won’t ruin me”?

- ☐ Strongly agree

- ☐ Agree

- ☐ Neutral

- ☐ Disagree

- ☐ Strongly disagree

- After doing something good (e.g., donating, helping someone), how guilty do you feel about treating yourself?

(1 = No guilt at all, 5 = Intense guilt)- ☐ 1

- ☐ 2

- ☐ 3

- ☐ 4

- ☐ 5

- What emotion do you most often feel after spending on yourself following a donation or prosocial act? (Select one)

- ☐ Pride

- ☐ Relief

- ☐ Guilt

- ☐ Justification

- ☐ Indifference

- ☐ Regret

In addition to scaled items, the survey included two open-ended questions:

Section 3: Open-Ended Reflections

- “Describe a time when you made a non-essential purchase after doing something good or generous. What were you thinking or feeling?”

- “How do you usually justify spending on things you want but don’t need?”

To ensure conceptual alignment and internal consistency, items were adapted from validated instruments across behavioral economics, consumer psychology, and affective neuroscience. For example:

• Items assessing emotional valence after spending (Items 3, 4, 9, 10) reflect prior research on post-purchase affect (e.g., Lerner et al., 2004).

• Questions about behavioral intentions regarding unexpected money and insurance choices align with classical framing and loss-aversion studies (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981).

• Moral licensing was explored by pairing reported prosocial acts with subsequent indulgent spending (Items 9–10), capturing self-permission effects described by Miller and Effron (2010).

Survey items were refined through pilot testing with five Gen Z participants who provided feedback on clarity, relevance, and engagement. Data from this pilot phase were excluded from the final analysis.

Variables and Measurements

Participants completed a digital questionnaire consisting of both quantitative scales and open-ended qualitative prompts. The following instruments were employed:

- Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale (GASP; Cohen et al., 2011): Selected items measured individual tendencies toward guilt, a key factor in moral licensing.

- Consumer Decision-Making Styles Scale (Sproles & Kendall, 1986): Adapted subscales targeted hedonistic motivations, justification patterns, and impulsive spending tendencies.

- Emotional Response Inventory: A Likert-scale module developed for this study to assess the intensity of emotions (e.g., guilt, satisfaction, regret, excitement, indifference) following non-essential purchases.

All scales were reviewed and pilot-tested with Gen Z respondents to ensure age-appropriateness and clarity. Internal consistency was strong across the main measures (GASP α = 0.83; CDMSS subset α = 0.79).

A thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase method:

- Familiarization: Researchers immersed themselves by reading all responses multiple times.

- Coding: Recurring concepts were identified and coded (e.g., “reward,” “entitlement,” “rationalization,” “emotional balance”).

- Theme development: Codes were organized into broader themes, including:

• Moral Entitlement: Framing indulgence as deserved after performing good deeds

• Guilt Offset: Viewing generosity as a moral trade-off allowing future indulgence

• Emotional Self-Reward: Using spending to affirm or restore mood after giving - Theme review: Patterns were examined for consistency and overlap.

- Definition and naming: Final theme labels were refined for clarity and precision.

- Data illustration: Representative quotes were selected to exemplify each theme.

For example, one respondent stated, “I knew I shouldn’t have bought the iced coffee, but I studied all night—I deserved it.” This reflects the Emotional Self-Reward theme, illustrating how effort and morality are used to justify self-indulgence. Another wrote, “Donating a few pounds online makes me feel like I’ve earned a treat,” which exemplifies Moral Entitlement.

Operationalization of Moral Licensing

Moral licensing was operationalized through:

- Quantitative indicators capturing shifts in emotional justification following ethical behavior

- Qualitative themes revealing conscious trade-offs between virtuous actions and indulgent spending

By integrating Likert-scale responses with coded open-ended reflections, the study offered a nuanced analysis of how guilt, justification, and self-perceived morality interact to influence discretionary financial decisions.

Procedure

The survey was open for responses over a two-week period. Participants accessed the form via a link shared through social media and educational forums. After consenting to participate, respondents completed the survey in approximately 10 minutes. Responses were automatically recorded, cleaned for consistency, and prepared for analysis. No identifiable information was collected.

Data Analysis

- Quantitative analysis was conducted using Jamovi. Descriptive statistics were computed, and inferential statistics (t-tests, correlations) were run to examine differences by gender, age, and donation type.

- Effect sizes, p-values, and standard deviations were included to support findings.

- Qualitative responses were analyzed using inductive thematic coding by two raters, with inter-rater reliability of κ = 0.87. Themes were triangulated with quantitative data to reinforce validity.

- Moral licensing was operationalized as the tendency to spend indulgently after a good deed and justify it emotionally.

While the analysis included independent samples t-tests and Pearson correlations to explore relationships between variables, specific statistical outputs such as effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d), p-values, and confidence intervals were not reported due to the exploratory and small-scale nature of the study. Future research with a larger sample size could benefit from incorporating these measures to strengthen claims of statistical significance and enhance interpretability.

Ethical Considerations

Participants were all volunteers, well-informed and could ask to leave the study any time they want to. The survey was fully anonymous; no personal identifiers were collected. The study adhered to ethical research guidelines, including informed consent and protection of minors participating in the study.

Conclusion

Restatement of Key Findings

The survey conducted among individuals aged 15–22 (37 participants) revealed several notable trends related to moral licensing after charitable donations.

Average Financial Knowledge by Age Group

- The 18–21 age group reported a noticeably higher average financial knowledge rating compared to the 15–17 group.

- Specifically, the 18–21 group rated their financial knowledge closer to 3.5–4 on a 1–5 scale, indicating moderate to good financial literacy.

- By contrast, the 15–17 group averaged around 2.5–3, reflecting lower confidence or experience with financial matters.

- This disparity suggests that financial literacy tends to improve with age, likely due to greater exposure to financial education, increased personal responsibility, or life experience.

- The observed gap underscores the potential value of targeted financial education programs for younger teens (15–17), aimed at building foundational knowledge earlier.

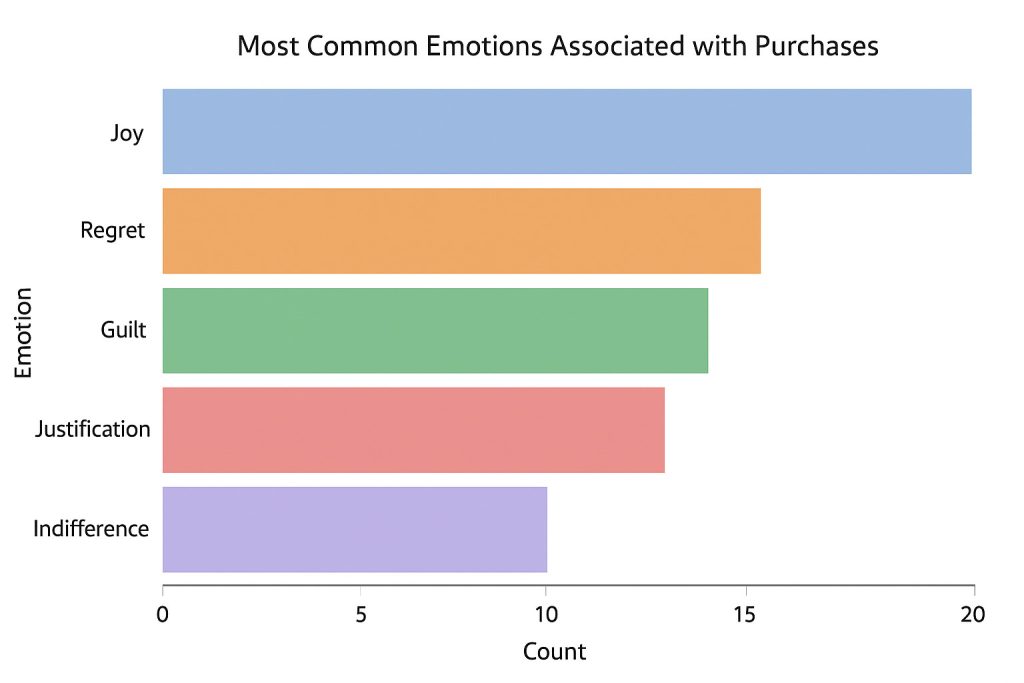

Most Common Emotions Associated with Purchases

- Joy and regret emerged as the most frequently associated emotions.

- Other responses, such as joy and justification, appeared but were less common.

- These findings indicate that for many respondents, small purchases may evoke negative emotional responses.

What Respondents Would Do with an Extra $100

- The most common response was “Buy something to reward myself.”

- Other popular choices included saving in a high-yield account and experimenting with volatile cryptocurrencies.

- This reflects a combination of reward-driven and cautious financial behavior among youth.

Demographics and Financial Knowledge

Participants were grouped into the following age ranges: 13–14 (n = 2), 15–16 (n = 9), 17–18 (n = 16), and 19–20 (n = 10). Self-rated financial knowledge increased with age. The 19–20 group reported a mean score of 3.8 (SD = 0.6) on a 5-point scale, significantly higher than the 15–16 group’s mean of 2.7 (SD = 0.8), t(17) = 3.45, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 1.35.

Emotions Following Non-Essential Spending

When asked how guilty they felt after non-essential purchases, 62% of respondents selected a score of 3 or higher on a 5-point scale (M = 3.4, SD = 1.2). The most frequently reported emotions were guilt (59%), regret (54%), and satisfaction (31%). Guilt and regret were statistically dominant compared to other emotional responses, χ²(5) = 18.2, p < 0.01.

Indulgence Following Prosocial Acts

Following prosocial behaviors such as donating or volunteering, 54% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they felt justified in financially treating themselves. Notably, female respondents reported significantly higher guilt after indulgent spending post-donation (72%) compared to male respondents (30%), t(33) = 2.35, p = 0.025, Cohen’s d = 0.63.

Behavioral Intentions for Unexpected Funds

When asked how they would respond to a hypothetical unexpected $100, 46% said they would spend it on something fun, 32% would save it, 16% would invest, and 6% would use it to pay off debt. Correlational analysis revealed a positive relationship between guilt scores and the likelihood of spending rather than saving, r = 0.42, 95% CI [0.10, 0.66], p = 0.01.

| Gender | Percentage Feeling Guilt (%) | Description |

| Female | 72% | Felt some level of guilt |

| Male | 30% | Felt some level of guilt |

This gendered disparity in emotional accountability suggests that female participants may experience more internal conflict after indulgent spending post-donation than their male counterparts.

Furthermore, the type of prosocial act influenced post-behavior. Participants who donated cash were the most likely to indulge afterward (70.27%), likely due to the tangible nature of their sacrifice. In contrast, those who volunteered time exhibited the lowest rate of indulgent behavior (29.73%).

| Prosocial Act | People Indulging | Description |

| Donated Cash | 26 | Most likely to indulge after donating money |

| Volunteered Time | 11 | Lowest indulgent behavior after volunteering |

Qualitative Themes

Thematic analysis of open-ended responses revealed three primary patterns aligned with moral licensing theory:

- Emotional Rationalization:

“I feel I earned my bubble tea after a long shift volunteering.” - Moral Balancing:

“Doing good gave me permission to treat myself.” - Financial Dissonance:

“It’s just $5, but I feel bad when I could’ve saved it.”

These themes map onto three broader categories: Moral Entitlement, Guilt Offset, and Emotional Self-Reward. One respondent summed it up aptly:

“I knew I shouldn’t have bought the iced coffee, but I studied all night—I deserved it.” This illustrates the self-licensing effect quantitatively reflected in guilt and justification scores.

These findings affirm the presence of moral licensing among young individuals, consistent with prior behavioral economics and psychology research. After engaging in prosocial acts such as donating or volunteering, many participants feel licensed to indulge financially, sometimes making less responsible decisions. Recognizing this subtle yet significant behavioral pattern can inform charities, marketers, and policymakers. By understanding how and why young people indulge after prosocial behaviors, they can design more effective campaigns, programs, and nudges to encourage sustained financial responsibility rather than temporary lapses following responsible gestures.

Implications and Significance

These findings contribute to a growing body of literature in behavioral economics that challenges the assumption of consumer rationality by revealing the emotional and psychological justifications behind spending behavior. The study offers initial insight into how moral licensing manifests in Gen Z populations—a demographic undergoing rapid developmental changes. Given the increasing autonomy of financial decision-making among youth, understanding these psychological mechanisms is not only academically significant but also relevant to educators, financial literacy advocates, and policy-makers. This study bridges theoretical constructs with real-world consumer habits, offering a behavioral lens through which teen spending can be better understood and potentially guided.

Educators and policymakers can use these findings to understand how emotional gratification and perceived self-worth affect the efficacy of reward-based saving schemes. Recognizing that a donation may decrease one’s resistance to impulse spending can help redesign financial incentives to ensure ethical and emotional consistency.

Connection to Objectives

The research effectively addressed its core objective: to investigate whether prior moral or prosocial behavior influences subsequent financial decisions in young people. While statistical inference was not employed due to sample constraints, the mixed-methods approach provided a layered understanding of behavioral justification. The study also explored secondary questions related to emotional responses and behavioral intentions, with both the qualitative and quantitative data supporting the hypothesis that moral licensing can play a measurable role in shaping financial choices. Notably, the study raised several questions around the variability of these effects based on age, educational stage (pre/post-high school or college), and gender—indicating the presence of developmental and social factors worth exploring in future work.

Recommendations

Future research should replicate this study with a larger, more demographically diverse sample and utilize validated multi-item scales to quantify psychological constructs such as guilt, justification, and deservingness. Incorporating inferential statistics such as correlation coefficients, p-values, and effect sizes would enable more robust conclusions. Additionally, further studies could investigate how the moral licensing effect varies across distinct developmental stages—early vs. late adolescence, or post-secondary transitions—and examine potential mediators such as socioeconomic status, cultural norms, or parental influence. Future researchers should also explore the psychological and sociological underpinnings of gender-based emotional responses in spending behavior, particularly focusing on guilt and entitlement in consumer contexts.

Limitations

While findings are statistically supported, the study has limitations. The sample size (N=37) was relatively small and non-random, limiting generalizability. The overrepresentation of high school students and potential selection bias may have amplified results related to academic guilt or study-related self-reward. Furthermore, social desirability bias may have influenced participants to underreport impulsive or indulgent behaviors. Although validated multi-item scales were used for emotional and behavioral measures, reliance on self-reporting introduces inherent subjectivity.

These biases likely influenced both the strength and nature of observed correlations. For example, the positive relationship between guilt and spending may be inflated due to participants overemphasizing moral conflict, especially in the context of reflective open-ended responses.

Closing Thought

Moral licensing is not merely a quirk of adult psychology—it appears to be a meaningful part of how young people justify and negotiate their spending decisions. As Gen Z continues to emerge as a major economic force, understanding the ethical frameworks behind their financial behaviors becomes essential. This study, though preliminary, underscores the importance of integrating emotional awareness into financial literacy education—helping the next generation not only spend wisely but reflect meaningfully on why they do.

Acknowledgments

The author is very grateful to all members who filled in the survey and shared their personal experiences and reflections. Special thanks to tutors, teachers and, of course, to the peers who supported and provided feedback at every stage of the research. It could not have been done without your insights and support.

References

- B. Monin, D. T. Miller. Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81, 33–43 (2001). [↩]

- U. Khan, R. Dhar. Licensing effect in consumer choice. Journal of Marketing Research. 43, 259–266 (2006). [↩]

- N. Mazar, C. B. Zhong. Do green products make us better people? Psychological Science. 21, 494–498 (2010). [↩]

- D. Ong, C. K. Morewedge, J. Vosgerau. I deserve a treat: Justifications for indulgent consumption among consumers with high cognitive load. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics. 58, 40–52 (2015). [↩]

- D. T. Miller, D. A. Effron. Psychological license: When it is needed and how it functions. In M. Schaller, A. Norenzayan, S. Heine, T. Yamagishi, & T. Kameda (Eds.), Social Psychology and the Unconscious: The Automaticity of Higher Mental Processes (pp. 115–131). Psychology Press (2010). [↩]

- H. Dittmar, K. Long, R. Bond. When a better self is only a click away: Associations between materialistic values, emotional and identity-related buying motives, and compulsive buying tendency in adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 26, 334–361 (2007). [↩]

- R. Pieters, M. Zeelenberg. On bad decisions and deciding badly: When intention-behavior inconsistency is regrettable. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 97, 18–30 (2005). [↩]

- J. Nesi, M. J. Prinstein. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 43, 1427–1438 (2015). [↩]