Abstract

This study examines the harm reduction procedures and effectiveness of Oregon’s Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act, or Measure 110, which was enacted in November 2020 and repealed in March 2024. In a comparative analysis, Portugal’s harm reduction policy Law 30/2000 from 2001 was also evaluated for its execution and results. Data on illicit drug use and overdose deaths from United States federal government agencies was collected to assess the results of Measure 110. Additionally, online surveys were collected from both drug users and non-drug users to assess the psychological impact of harm reduction policies. This paper presents multiple findings on the procedures and implementation of Measure 110. It was discovered that information sharing by law enforcement to drug users about rehabilitative options was not effective in practice due to lack of training. Furthermore, delays in funding hindered efforts to make health centers accessible, and there was a notable lack of emotional and physical support systems for drug users. On the other hand, Portugal’s harm reduction services were multifaceted, such as career training programs, therapy and counseling, and housing resources, which Oregon’s Measure 110 did not encompass due to a divided political landscape. These insights on harm reduction laws hold significant implications for future policymakers as they develop effective public health legislation.

Introduction

Since the 1960s, a restrictive approach to drug policy known as the War on Drugs, has incurred the United States approximately $1 trillion in government spending, yet illicit drug use remains a persistent issue1. Supporters claim that a punitive approach discourages civilians from drug use by imposing penalties. Critics denounce its harsh crackdowns and the mass incarceration of drug users who may need assistance. In contrast to typical U.S. policies, Portugal enacted Law 30/2000 in 2001 that decriminalized the use and possession of all illicit drugs, guided by a principle known as drug “harm reduction”, aimed at mitigating the social and legal consequences of drug use2. Over the past 20 years, fatal drug overdoses in Portugal have been reduced by 80%3. This policy attracted worldwide attention for its innovative new strategies, and other countries such as the United States have started to consider similar policies.

Recently, many U.S. citizens and politicians have begun to take notice of these alternative approaches to combat crippling rates of drug addiction. To date, the most ambitious harm reduction law in the United States has been Oregon’s Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act, or Measure 110, in 2020. It reclassified the possession of all illicit drugs from a Class A misdemeanor to a Class E violation that resulted in a $100 fine or completed health assessment. This made Oregon the first state in the United States to decriminalize drug possession. However, after monitoring the effects of Measure 110 for three years, the Oregon State Legislature passed House Bill 4002 in February 2024, recriminalizing the possession of illicit drugs as a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail.

Preliminary research on Measure 110 and its effects on public health have reported mixed results. For example, a cohort study research paper in 2023 analyzed cause of death data from the National Vital Statistics System and found no correlation between Oregon’s implementation of Measure 110 and an increase in drug overdoses4. On the other hand, another research paper in 2023 used the synthetic control method to determine that the enactment of Measure 110 caused more drug overdoses than if it had not been passed5. However, this research focused solely on the quantitative results and did not report the cause of ineffectiveness of Measure 110.

This study will use reputable data reported by the United States government to determine the effectiveness of Measure 110 by analyzing drug usage rates and drug overdose mortalities from Oregon, neighboring states, such as Utah and Nevada, and the whole country. Oregon and Portugal were chosen as sources of study for their similar use of harm reduction in response to a rapid increase in drug use. Although Oregon and Portugal differ in many aspects, with factors like healthcare system, culture, and religion, comparing the impact of their harm reduction policy still provides useful information on how harm reduction should be implemented. Neighboring states Nevada and Utah provide context to Oregon’s performance as they share similarities like geographic proximity, demographics, and exposure to similar national drug trends, yet they did not enact comparable harm reduction policies, making them useful comparison cases.

Additionally, this study collected online surveys that will add insight to the psychological rationale behind harm reduction policies. As Portuguese doctors conducted numerous research studies on drug use and used these findings to create Law 30/2000, human psychology can play an influential role in determining a policy’s success. Furthermore, the mechanisms of Measure 110 will be compared with Portugal’s aforementioned harm reduction policy. By examining the results and strategies for Oregon’s Measure 110, this research will provide insight into how harm reduction principles can be better applied to improve public health. This paper will investigate the question whether Measure 110 was beneficial in mitigating drug use, and to what extent if so.

Drug Policy in Portugal, the United States, and Selected States

This section outlines the definition of harm reduction, the specific procedures Portugal and Oregon utilized with their health policies, and how Nevada and Utah serve as sample cases.

Drug Use Background

When addressing sensitive topics of drug use and drug users, it is important to carefully consider the language surrounding these terms. There has been a recent increase in state legislation legalizing certain quantities of recreational marijuana6, complicating the definition of illegal drug use. In this study, “drug use” is defined as the consumption of addictive substances across all levels. It is acknowledged that certain drugs are more harmful than others, such as heroin compared to marijuana. However, because Measure 110 equalized the treatment of all drugs, this paper will not differentiate the severity of drugs.

Harm Reduction Policy

Harm reduction is a public health approach aimed at minimizing the negative consequences of drug use. Rather than exclusively targeting the complete elimination of harmful behaviors, harm reduction strategies prioritize interventions that reduce harm and improve individual well-being2. This approach encompasses a range of procedures, including supervised injection sites and needle exchange programs, with the ultimate goal of promoting safer practices and creating an environment for individuals to access care and recovery services without stigma.

At the core of harm reduction is a commitment to non-judgmental practices that respect the dignity and autonomy of individuals, regardless of their drug use. Harm reduction can be implemented through various means. Decriminalization, removing criminal sanctions due to drug use, is one aspect of harm reduction. Depenalization, reducing criminal penalties, could also be used in harm reduction law. For harm reduction policies to be most effective, multiple treatment strategies should be coordinated to address the factors that affect drug use, such as destigmatization to decrease societal judgment and encouraging more drug users to seek therapy. Other options include education and career training resources, access to mental health services, and sharing information to prevent overdoses.

Portugal’s 2001 Law

During the 1990s, Portugal experienced a widespread heroin epidemic, with 1 in every 100 citizens addicted to heroin7. To combat rising overdoses, the Portuguese government enacted Law 30/2000, which decriminalized the possession and use of small quantities of illicit drugs (no more than 10 days’ of use)8. While drug trafficking remained a crime and drug dealers continued to be charged criminally, personal drug use was reassigned from a crime to an administrative offense. An intricate system of integrated support at several levels was multilaterally established with various organizations to assist drug users. The law was initially created by a team of nine experts, ranging from judges, psychologists, and health professionals, recruited by the Portugal Prime Minister António Guterres in 1998 to devise a national strategy to resolve the crisis. The experts travelled to other European countries and researched extensively to create a well-rounded solution. After receiving support from government leaders, the team presented their plan to the public through various forums and discussions to gather support. The law successfully passed in 2001 and employed many nonprofit agencies under contract with the government9. This policy received unified support from citizens and government officials, who worked together collectively to address the national crisis of heroin.

Under the new law, which was relayed to law enforcement, individuals found by police in possession of illicit drugs were not arrested but rather referred to a “commission for the dissuasion from drug abuse” (CDT), which are civil bodies that operate under the Ministry of Health instead of the previous Ministry of Justice. These organizations provide information and advice to drug users, ultimately guiding them to rehabilitation with social, physical, and psychological support. CDTs and their centers were established in all 18 districts of Portugal under Law 30/2000, ensuring accessible resources for all citizens.

At the CDTs, a team of health professionals, psychologists, and sociologists evaluates the situation of each drug user and formulates a tailored recovery plan. This assessment involves detailed interviews following standardized procedures to collect all pertinent information. Then, the CDTs consider various factors, such as the severity of substance dependency, whether it was the individual’s first encounter, and their emotional state. Based on the evaluation, they provide referrals to various free support services, including health centers, educational institutions, social centers, homeless shelters, and employment centers. Because the CDTs assessed each individual’s unique scenario based on their personal background and family history, these health professionals used a preventative approach to treat any issues as early as possible. They gave specialized recommendations and a recovery plan for each individual.

Treatment options available to CDT clients include individual and group psychotherapy, social care and therapeutic services, medical and nursing consultations, and relapse prevention. Portugal also provides universal public healthcare to its citizens through the National Health Service, which gives all citizens access to free or low-cost primary care to general practitioners, specialist care, mental health services from psychiatrists and psychologists, and maternity care. To fund this service, Portugal dedicates money from taxes and social security contributions to the National Health Service.

In addition, Portugal established a system to coordinate efforts across various institutions. The Inter-ministerial council, chaired by the Prime Minister, was created to oversee drug policy at the national level. The council includes the National Drug Coordinator and Ministers responsible for Justice, Health, Education, Science and Higher Education, Labor, Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs, National Defense, Finance, Environment, Social Security, Agriculture, and Economy. Each minister selects a representative to a Technical Committee which is overseen by the National Drug Coordinator. This Committee collaborates to develop strategic plans aimed at improving public health and has significantly improved the integration of harm reduction services across the country. For example, street police officers received systematic training to direct drug users to counseling services and support meetings. The implementation of the new 2001 law also took time, with the government launching several pilot programs over several years to integrate harm reduction into additional avenues, such as through street teams and vans10.

Although drug users are not obligated to attend the CDTs or follow the recovery plan provided, CDT workers consistently follow up to ensure their health and wellbeing. In some instances, CDTs may require periodic attendance or community work from certain individuals to maintain their accountability. Ultimately, sanctions may be imposed as a last resort to encourage compliance to their recovery plan among problematic users or repeat users8.

In addition to the 80% reduction in drug-related deaths3, the Portuguese Ministry of Health reported in 2017 that about 25,000 Portuguese citizens use heroin, down from estimates of 100,000 in 200111. Additionally, a report published in 2021 by the Transform Drug Policy Foundation shared that Portugal’s drug death rates have remained low, with 6 deaths per million among people aged 15-64, compared to the E.U. average of 23.7 per million12. However, concern about the effectiveness of Portugal’s drug policy has recently emerged. A 2023 article released by The Washington Post noted that open drug use has been overflowing Portugal’s streets with a 24% increase in public drug-related debris in 2022. A 14% increase in crime and robberies was observed in the same year along with rising drug overdoses rates13.

History of the War on Drugs

Illicit drugs such as marijuana have been used in the United States for centuries14. Federal laws restricting drug use only emerged in 1909 with the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act, which banned the importation and use of opium for non-medicinal purpose15. Major shifts in drug usage were not observed for several decades16; however, in the 1960s, drug use rose dramatically as easier access to heroin, marijuana, and cocaine spread in major cities17.

In a 1971 White House press conference, President Richard Nixon declared drug abuse to be “public enemy number one” and increased federal funding for drug control agencies and treatment efforts. This was the start of the federal “War on Drugs,” in which Nixon launched a bipartisan government initiative to combat the distribution of illegal drugs by emphasizing the role of law enforcement and incarceration. The War on Drugs expanded under President Ronald Reagan’s administration with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which introduced mandatory minimum jail sentences for crimes associated with drugs. Incarceration rates for drug offenses sharply increased in the years after the Anti-Drug Abuse Act18. In the 21st century, the focus of the War on Drugs began to shift from incarceration. President Barack Obama posted that the United States “cannot incarcerate our way out of the drug problem”19 and enacted the Fair Sentencing Act in 2010, which reduced the penalties for crack cocaine offenses and raised statutory fines20.

The War on Drugs has been widely criticized by many citizens and politicians for its disciplinary approach and reliance on incarceration to deter drug use21. Oregon has traditionally followed penalty-based laws to deter drug users, but voters decided to pass Measure 110 to combat rising drug use in their cities, a trend that had continued for the past several years.

Oregon’s Measure 110

In 2020, Oregon voters approved Measure 110 with a 58% affirmative vote. The law reclassified the possession of all illicit drugs from a Class A misdemeanor to a Class E violation. Drug users with the violation had to pay a $100 fine or complete a health assessment. This change made Oregon the first state in the US to decriminalize drug possession. Individuals involved in the manufacturing or distribution of illegal drugs continued to face criminal penalties under this legislation. Oregon also established the Drug Treatment and Recovery Services Fund to finance the creation of addiction recovery centers, which offered 24/7 medical treatment, health assessments, medical interventions, and peer support programs22. Measure 110 outlined that law enforcement would issue the $100 fines along with cards listing the treatment hotline number as an alternative to paying the fine23.

Measure 110 also emerged during a time of national disarray and conflict due to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the surge of fentanyl in drug markets across many states. As the measure passed with 58% affirmative votes, a close majority, the implementation of its policies faced much scrutiny from political and ideological dissidents. Opponents who resisted the policy’s objectives publicly raised their concerns, which made it more difficult for officials to rally support and funding for Measure 110. As later expanded on in the Discussion section, Measure 110 heavily suffered in its execution, facing bureaucratic slowdowns in program funding, public backlash, and a national lack of healthcare supplies due to the pandemic23.

Reversal with House Bill 4002

Following its implementation, public support for Measure 110 decreased sharply within a few years, with only 2% of respondents from an August 2023 poll believing that the policy was successful. In comparison, 61% of voters believed that Measure 110 had been a failure due to increasing drug rates24. In response to public opinion, the Oregon State Legislature passed House Bill 4002 in 2024, recriminalizing the possession of illicit drugs as a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail. The bill also allowed police to seize illicit drugs from active drug users in public spaces and urged law enforcement agencies and prosecutors to refer drug users to treatment programs23.

Effectiveness of Oregon’s Measure 110

To assess the impact of Measure 110 on public health in Oregon, various publications examining the consequences of illicit drugs, correlation with external factors, and the increase of fentanyl in the country, were reviewed. Additionally, this paper reviewed two previous studies that reached differing conclusions on effectiveness of drug use decriminalization in Oregon.

Fentanyl in the United States

As mentioned in the “History of the War on Drugs” section, the United States has a complex background of drug use, but notably experienced a surge in illicit fentanyl use over the past decade25. Fentanyl is a highly potent synthetic opioid, approximately one hundred times stronger than morphine26. While it is used medicinally for pain management, fentanyl can be lethal when abused for recreational purposes. Just two milligrams of fentanyl can perilously slow breathing or completely stop breathing, leading to permanent brain damage or death27. Drug dealers have been increasingly mixed fentanyl into other illicit drugs to enhance the potency, which leads to many accidental overdoses and deaths. Illegal drug distributors are currently smuggling fentanyl from Mexico into the United States to distribute it on the drug market26.

The COVID-19 pandemic also intensified the drug crisis in the United States, coinciding with the implementation of Measure 110 in 2020. A 2021 study found a 16% increase in drug use amongst users since the onset of pandemic in the United States. Individuals in self-isolation reported a 26% higher consumption rate than usual to alleviate their mental condition28. Moreover, opioid use can compromise the immune system, making it more difficult for users to recover from infectious viruses like COVID-19, leading to a higher mortality rate29.

Drug Use in Oregon

Oregon has been experiencing increased levels of overdose deaths in the past decade, mirroring an increase in drug use and overdoses across the country30. Drug use is linked to health issues, including lung and heart disease, damage to the mouth, cardiovascular disease, strokes, and cancer. Furthermore, mental health disorders like anxiety, depression, or schizophrenia are related to drug use, which some individuals may employ as a coping mechanism. Unfortunately, drug use has been shown to worsen and exacerbate these mental health conditions instead of alleviating them and can lead to long-term addiction31.

Regarding the pandemic, Oregon implemented strict lockdown mandates, which shut down businesses and stores across the state32. As previously noted, poor mental health can lead to increased drug use, suggesting that the rise in drug use in Oregon may have occurred independently of Measure 110, complicating evaluation of the policy’s effectiveness.

Accidental overdoses in Oregon almost quadrupled from 2020 to 2022, rising from 233 to 843 overdose fatalities33. This rapid increase in overdoses in Oregon may be partially attributed to the national fentanyl crisis which is, as previously noted, much more lethal than other common drugs. Both factors with the new implementation of Measure 110 and increase in fentanyl occurred around 2020, complicating analysis of overdose results. However, as later observed in the other comparison states such as Utah in the Results section, while some states also had rising rates, other states experienced a lower increase in overdose data, illustrating that Oregon’s policy response to the fentanyl surge with Measure 110 did not perform better than other legislation.

Prior Studies on Effectiveness of Measure 110

Analysis of the effectiveness of Measure 110 have shown conflicting results. One study from 2023 used the synthetic control method to determine the predicted number of overdoses based on other states and trends in 2021. The synthetic control method is a statistical approach that uses a weighted combination of control units to create an artificial control unit, enabling researchers to evaluate the effect of a specific variable in comparative case studies, often in the realm of public health34. This study utilized data of unintentional drug overdose deaths from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) provisional Multiple Cause of Death database to build a synthetic model for Oregon. Based on the actual overdose deaths in 2021, the model shows that Oregon suffered approximately 182 additional overdoses in 2021 as a result of Measure 110, translating to 23% increase in accidental overdoses4.

In contrast, another study from 2023 used the synthetic control method to determine the impact of Measure 110 on fatal overdose rates, utilizing data from Oregon and Washington, the latter serving as a synthetic case due to its own harm reduction policy, which increased support programs but did not decriminalize drugs. This study used the forty-eight remaining states, which did not implement harm reduction policies, as a base scenario. The study used final multiple cause-of-death data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) from 2018-2021, along with provisional data from NVSS in 2022. The results indicated that the monthly overdose rate between Oregon and the synthetic model was not statistically significant, showing an average change of 0.268 change per 100,000 state population5.

These studies reflect the ambiguity surrounding the effectiveness of Measure 110, as many complex variables interacted over the duration of this policy. The differing conclusions of these two studies can be attributed to variations in data sources from different government institutions, distinct mathematical methodologies, and the potential of human or technical errors with the automated data processing of death certificates, which may have resulted in inaccurate representations. Additionally, the disparity in the time periods examined might also account for the contrasting results.

Drug Use in Comparison States Nevada and Utah

To accurately compare data on drug use and overdoses from Oregon to comparison states Nevada and Utah, additional information must be provided to better analyze each situation. To start, each state has different drug trafficking networks or systems in cities or metropolitan areas, where illicit drug access is more prevalent. Oregon has a higher population density with 44.1 people per square mile, while Nevada and Utah have 39.7 and 28.3 people per square mile respectively35. Cities with higher population density have more complex drug trafficking networks interwoven into their environment as compared to spaces with lower population density.

In addition, access to healthcare and medical services is determined by federal, state and local governments and can affect drug use when analyzing specific public health acts like Measure 110. For example, in 2020, Utah expanded Medicaid to fund treatment to more low-income and disadvantaged individuals needing assistance, which allowed more individuals to undergo health reform. Utah is currently ranked as 14th place for state healthcare by the U.S. News and World Report, while Oregon and Nevada are lower at 17th and 36th respectively36. Even when considering these external factors such as drug trafficking networks and healthcare systems, public policy still has a significant impact on drug-related arrests and overdoses. This study recognizes that such differences shape how events like the fentanyl surge or the COVID-19 pandemic affect each state, but maintains that the contrast between Oregon’s Measure 110 and the more traditional drug laws in Nevada and Utah remains a primary factor influencing health outcomes. By inspecting drug use data and overdose fatalities from previous years before the implementation of Measure 110 in 2020, past trends of each state were analyzed to observe any noticeable changes.

Comparison Between Oregon’s and Portugal’s Harm Reduction Policy

| Oregon | Portugal | |

| History of Drug Policy prior to Harm Reduction | Before 2020, Oregon followed similar policies to the traditional United States War on Drugs, which had an emphasis on incarceration. It has cost the United States around $1 trillion in spending for law enforcement and incarceration costs. | Before 2001, Portugal enforced strict criminalization of drug use and granted law enforcement flexible means to obtain evidence to use in court. However, a few years before 2001, Portugal started reducing sentences and sanctions37. |

| Healthcare System | Similar to many U.S. states, Oregon uses a privatized healthcare system where citizens purchase their own healthcare insurance with government assistance from programs like Medicare or Medicaid for the elderly and low-income. | Portugal provides a free, universal healthcare system for citizens through the National Health Service and include services like primary care and medication. To cover these costs, Portugal uses taxes and social security contributions. |

| Government Implementation | Due to the strongly partisan nature of U.S. politics, Measure 110 faced strong internal opposition with government officials of different political backgrounds. For example, the state government rejected to fund proposed police training. | Because of the national heroin crisis of the late 20th century, the Portuguese government unified together behind the harm reduction law and worked across multiple government agencies under the Interministerial council to support its implementation. |

| Public Opinion and Reactions | In its initial release, Measure 110 garnered mixed reactions from policy experts, public figures, and nonprofit organizations. For example, addiction advocacy group Oregon Recovers Today opposed Measure 110 and released multiple statements. | After years of the heroin epidemic, government leaders presented their proposal to the public and gathered enough support to pass the law in 2001. With health improvements, the perception of the law was positive and received well. |

| Legal Decriminalization | Reclassified illicit drug use from a Class A felony to a Class E misdemeanor that carried a $100 fine and no jail time. A drug user could complete a health assessment and receive a treatment plan to waive the $100 fine, however in actuality, the $100 fine was not enforced. | Decriminalized illicit drug use in small quantities by removing incarceration penalties for recreational drug users, but not for drug distributors. Law enforcement redirected convicted drug users to CDTs, where three professionals assessed the situation and provided guidance. |

| Addiction Recovery System | Funded various health centers that provided treatment and health assessment across the state with state grants. In addition, a hotline that provided support resources was shared by law enforcement via information cards. | Set up the dissuasion commission that gave drug users treatment plans and recommendations based on their individual situation. Also redirected state funding to free healthcare and therapy programs. |

| Law Enforcement Procedures | Law enforcement officers were supposed to give drug users a fee ticket and information card that they could call to waive the fee, although this practice was not effectively communicated to the police and was not conducted systematically across police stations in Oregon. | Trained law enforcement officers to relocate convicted drug users to recovery centers and receive support from the dissuasion commission. Meanwhile, ministers in the Home Affairs, National Defense, and Justice departments worked closely with the Inter-ministerial Council. |

Results

Drug Usage Rates

Three states’ National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data from the 2018-2022 surveys, Oregon, Nevada, and Utah, were analyzed to calculate the rates before and after the implementation of Measure 110.

The data shows that while all three states had relatively similar increases in drug usage, there were notable differences among them. From 2019-2020, Oregon exhibited the lowest year-to-year growth rate at 6.70% whereas Utah had the highest at 24.57%. However, during the years after the implementation of Measure 110, Oregon’s drug usage rose the most out of the three states, with a 13.51% year-to-year increase. In comparison, Nevada and Utah recorded an increase of 11.54% and 11.64% respectively during the period from 2020 to 2022. It should also be noted that all three states’ drug usage was rising in the past years, and the fentanyl outbreak around the 2021-2022 period may have contributed to this continued increase. A multitude of factors, including healthcare or trafficking networks, as previously discussed may have contributed to the 13.51% increase, not solely Measure 110. However, Measure 110’s intention was to serve as a better solution to easing drug usage, therefore by observing its performance compared to neighboring states valuable information can be garnered. Although it is challenging to perform a statistical analysis with limited data, this information from NSDUH does not show a decrease in drug usage following the implementation of Measure 110 in 2020, raising concerns about the policy’s effectiveness in achieving its goals.

| NSDUH Illicit Drug Use from 2019-2022 | ||||||

| % Reported Using Drugs | Year-to-Year Change (%) | |||||

| Year | Oregon | Nevada | Utah | Oregon | Nevada | Utah |

| 2018-19 | 19.84 | 17.59 | 8.14 | |||

| 2019-20 | 21.17 | 20.01 | 10.14 | 6.70 | 13.76 | 24.57 |

| 2021-22 | 24.03 | 22.32 | 11.32 | 13.51 | 11.54 | 11.64 |

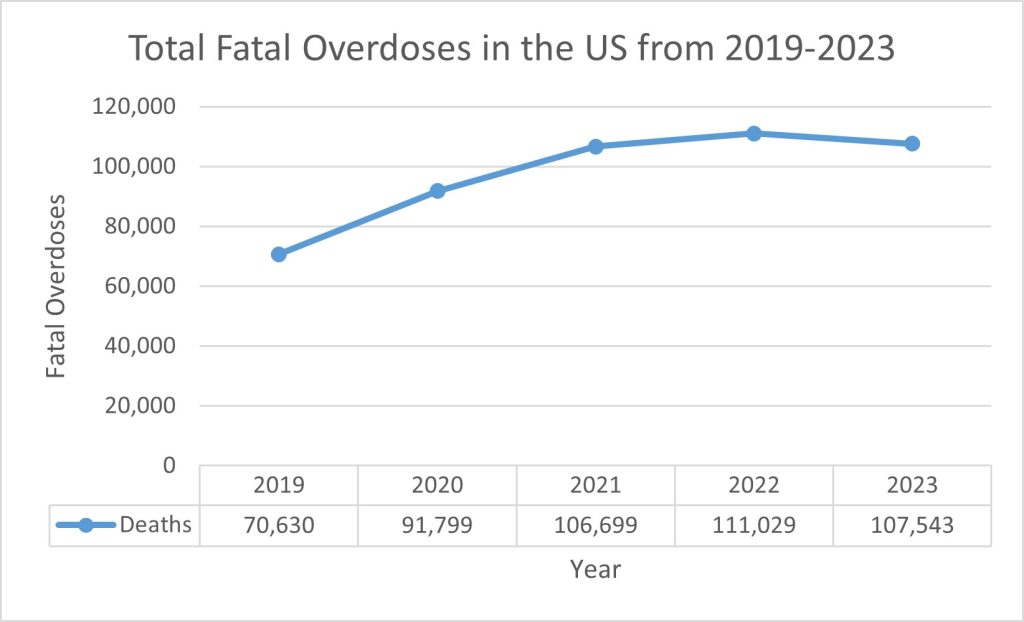

Drug Overdose Mortalities

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported data38 on drug overdoses for Oregon, Nevada, and Utah from 2019 to 2022. To ensure the accuracy of conclusions drawn from this data, the overdose figures were adjusted based on the population of each region and are reported per 100,000 people. Population statistics were sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau35.

An analysis of the overdose percentages reveals a consistent increase in Oregon, Nevada, and Utah from 2019-2022. From 2020 to 2021, when Measure 110 was first implemented, Oregon saw a spike from 19 to 28 per every 100,000 people. During the same period, Nevada’s rate changed from 27 to 30, while the national average changed from 27 to 32. In contrast, Utah’s overdose rates remained consistent, only changing from 19 to 20.

This consistency in Utah’s overdose rates may be attributed to the state’s strict drug laws as well as sociocultural factors, including religious influences. According to Weber Law, Utah enforces severe penalties for drug-related offenses in order to discourage substance use across the state39. Although there are many important factors outside of strict drug policy, such as healthcare systems, abundance of drug providers, and aforementioned religious or personal beliefs, criminal penalties such as those reversed in Measure 110 play a significant factor in influencing the drug use of civilians.

The national increase in fentanyl access also impacted every state, but as evidenced in the NCHS data, Oregon was affected strongly in the years following 2020. As Measure 110 outlined, fentanyl was included in the law’s decriminalization of all drugs and thus influenced the country’s response to the fentanyl crisis. Measure 110 accounted for fentanyl by using the same health-referral protocol as other drugs, which likely affected the rising overdose rates. By contrast, other states like Nevada did not use the same approach to fentanyl and enforced stricter penalties for those distributing and using the drug, which may have discouraged its use among the public. This overdose data from Oregon shows that Measure 110 did not perform better than its neighboring states in its goal to decrease drug use.

| Fatal Overdoses from 2019-2023 | ||||||||||||

| Annual Deaths | Population (in thousands) | Overdose Fatality (Per 100,000) | ||||||||||

| Year | Oregon | Nevada | Utah | Country | Oregon | Nevada | Utah | Country | Oregon | Nevada | Utah | Country |

| 2019 | 615 | 647 | 571 | 70,630 | 4,216 | 3,091 | 3,203 | 334,320 | 15 | 21 | 18 | 21 |

| 2020 | 803 | 832 | 622 | 91,799 | 4,245 | 3,116 | 3,284 | 335,942 | 19 | 27 | 19 | 27 |

| 2021 | 1171 | 949 | 662 | 106,699 | 4,256 | 3,147 | 3,339 | 336,998 | 28 | 30 | 20 | 32 |

| 2022 | 1363 | 1003 | 627 | 111,029 | 4,239 | 3,177 | 3,381 | 338,290 | 32 | 32 | 19 | 33 |

Online Survey

The online survey received twenty-three responses over a two-week period. Approximately 26% of participants had used recreational drugs at varying frequencies in their lifetime. Notably, 61% of participants did not know what harm reduction policy was prior to answering the survey. Overall, participants expressed ambivalent views towards harm reduction; they recognized the inefficiency of incarcerating drug users who need treatment, yet some felt that harm reduction policy could be too idealistic in assuming drug users are willing to change. Around 57% of participants conveyed mixed sentiments on the effectiveness of harm reduction. This was ascertained by analyzing each respondents’ answers and finding examples of both reservations and endorsements. Despite this ambivalence, about 74% of participants communicated general support for policies that implement some form of harm reduction, such as destigmatization, therapy resources, and mental health services. This percentage indicates that these respondents recognized value in harm reduction principles, rather than claiming that each individual necessarily endorsed the same or similar public policies. The survey gathered this information to determine whether people across generations or occupations valued the ideals of harm reduction in some form, which may aid policymakers as they outline laws that balance public health priorities with community opinions and provide more comprehensive support systems for people affected by drug use. This percentage was drawn from survey answers communicating support for harm reduction methods like destigmatization or mental health support. Most participants who supported harm reduction were from younger generations, specifically Millennials and Generation Z.

Discussion

The illicit drug use and fatal overdose data from Oregon indicate that Measure 110 was not effective in achieving its primary goal of lowering drug use. Many variables, such as increases in drug trafficking across the country, rise in fentanyl use, and worsening mental health due to the pandemic, can be noted as possible causes for the growth in drug use that Oregon experienced after the implementation of Measure 110. Alongside Nevada and Utah as well, this study found that Oregon did not perform better than these traditional drug policies, indicating that detailed assessment of Measure 110’s effectiveness is warranted. A key difference between Oregon and Portugal is that both governments employ different access to healthcare that may impact citizen’s resources for recovery. For instance, Oregon uses a privatized insurance system where civilians may purchase their plans from independent companies as necessary. Portugal funds the National Healthcare System through taxes and income deductions. This factor complicates discussion, as Oregon’s harm reduction policy was confounded by lesser access to health resources, while Portugal has provided free healthcare to its citizens. However, neighboring states such as Nevada and Utah, which maintained incarceration-focused drug policy, faced similar increases during the same time, suggesting that Measure 110 was not more effective than other legislative approaches in the U.S. Although these three states rank differently in healthcare quality, their healthcare systems have not had as much of a direct impact as Oregon’s Measure 110 did on illicit drug use.

On the surface, Oregon’s Measure 110 and Portugal’s harm reduction policy appear similar, as both remove incarceration as a penalty for drug users and emphasize treatment through Oregon’s referral system and Portugal’s CDTs. Both policies also directed law enforcement to guide drug users towards support systems provided by the government. However, data reveals that the harm reduction policy implemented in Oregon under Measure 110 was ineffective in reducing drug usage. The difference in effectiveness highlights the substantial disparities in actual implementation. Drawing on the “six stars” theoretical framework to analyze public policy, Measure 110 did not fulfill all criteria for efficacious legislation40. When analyzing the six aspects of this theory: attention, motivation to innovate, new solutions, political strategies, quality decision making, and guarantees for complete implementation, this paper finds that Oregon fell short on its intended proposals to create a structure of support for drug users. This was due to a polarized political landscape, which made it difficult for the state government to fully support this measure, therefore weakening the “motivation to innovate” and “political strategies” aspects. For example, law enforcement in Oregon was not systematically trained on how to handle drug users under Measure 110, resulting in infrequent use of the hotline intended for support. After 15 months of Measure 110’s implementation, only 119 individuals called the hotline. By December 2023, only 943 had called in nearly three years23.

Additionally, funding for Measure 110 encountered significant delays which hindered the establishment of health centers to provide resources for drug users. The community council, initially tasked with distributing nearly $300 million to recovery centers offering drug and alcohol treatment, faced challenges organizing and managing a system to allocate grants. With limited experience and insufficient assistance from the state, approximately $276 million was stalled from reaching the centers for several months. It took about six months for all the money to be awarded to these centers41. The issues in distributing funding hampered the centers’ ability to assist drug users in the initial months after Measure 110 passed. The health centers were crucial to Measure 110’s success, as they provided the services for drug users to complete the health assessment and receive treatment plans. This delay was due to the limited experience of the team, as this was the first time Oregon had organized harm reduction efforts, and thus, the process of building this system from scratch took longer than anticipated. This was also due to political discourse that made it harder for the government to allocate more resources to the council.

Qualitative data from the survey revealed notable concerns from participants. One survey respondent, who had used drugs frequently before, noted that “in some cases, [these policies] allow/enable drug use without corresponding realistic opportunities for alternatives like quality treatment.” The respondent observed that lessening criminal penalties may have the adverse effect of sanctioning drug use in a legal manner. In the survey, they expressed how, from personal experience, they had witnessed an increase in marijuana stores and drug use in public high school for the past few years and had reservations for decreasing deterrents like criminal penalties associated with drug use. One of their concerns was that “shallow harm reduction” without adequate services like “quality treatment” would not lead to positive outcomes. Measure 110 lacked a system comparable to Portugal’s effective and accessible CDTs, leading to enablement of drug use instead of assisted recovery. This is due to the lack of universal healthcare in the U.S. compared to Portugal, which provides basic assistance to every citizen through its National Health Service. Bureaucratic slowdowns also made it harder for Oregon state and local governments to implement the health center and procedures, which is caused by partisan divides and ideological conflict in the Oregon government. In contrast, Portugal’s system had unified support from officials due to the heroin crisis.

Another respondent, who had not used drugs before, pointed out that “while criminalizing and penalizing drug use has been used for decades, [harm reduction] policies seem like they could do more for this issue.” This particular respondent spoke from personal conviction instead of actual experience with harm reduction policy, as their state of residence does not employ harm reduction. They stated that “in addition to lowering the stigma surrounding drug use, policies such as needle exchange and therapy programs allow those suffering from addiction to seek potential treatment”. Portugal’s approach focused on providing the community with accessible resources and funding through the CDTs, an area that was touched on with Measure 110’s health centers but not sufficiently expanded to reach drug users seeking reform. As previously mentioned, Oregon’s partisan interests divided the state government, leading to an underequipped grant team that was unable to properly distribute state funds to qualified and certified health centers to provide treatment resources to drug users seeking help.

Along with investigating the principles of harm reduction, the context of this policy’s environment needs consideration. Portugal implemented its harm reduction policy with unified support from involved governmental agencies. This was due to the national heroin crisis in the late 20th century, which necessitated swift and full-fledged government action. Similarly, Measure 110 aimed to combat rising drug rates amidst a national fentanyl crisis in 2020. Bureaucratic slowdowns and implementation concerns made Measure 110’s health centers difficult to set up, as shown in the hesitation of Oregon officials to completely endorse and fund Measure 110.

In conclusion, this paper has found that the primary reason behind Measure 110’s ineffectiveness in lowering drug use was its failure in launching a coordinated campaign treating drug abuse as a public health issue rather than a criminal offense. By comparing Portugal’s law, it is evident that effective harm reduction requires a well-coordinated effort across a complex, multimodal national system involving various institutions working together with a unified goal. Harm reduction strategies must provide various points to inform, prevent, treat, and rehabilitate drug users systematically. Simple decriminalization, as demonstrated by Measure 110, is inadequate to achieve positive outcomes in public health.

Key Takeaways

Policymakers can gain valuable insights by comparing the successes of Portugal’s drug policy to the failures of Measure 110 in Oregon. Even though both policies seem similar at surface-level, it is crucial to tailor policies to the specific sociocultural context, healthcare systems, and backgrounds of the citizens affected with drug addiction. Moving forward, policymakers should take the following actions when contemplating harm-reduction strategies.

First, an organized plan for timely grants should be developed to prevent the funding delay experienced by recovery centers in Oregon. Ensuring that critical resources are readily available for drug users is essential before implementing harm reduction policies. Additionally, law enforcement must receive professional training in dealing with drug users under a decriminalized law. In Oregon, the lack of clear guidance on how to handle drug users under Measure 110 led to mismanagement of information cards and hotlines, rendering them ineffective. Policymakers should allocate more resources to prepare all relevant agencies to effective direct drug users to appropriate support services. Oregon’s Measure 110 faced bureaucratic opposition from the beginning of its tenure, which hindered the agencies and councils behind its harm reduction procedures. Future measures should unify government officials and citizens together to work towards a common goal instead of dividing the public. Part of Portugal’s success was that the public was united in ending the heroin crisis. This points to a larger trend of partisanship and political divides present in the United States that Measure 110 ultimately suffered from.

Most importantly, drug policies must ensure that drug users actively engage in recovery efforts; otherwise, decriminalization may enable continued substance abuse. Portugal’s system demonstrated that harm reduction is effective when integrated with additional institutional support. In contrast, Measure 110’s focus on decriminalization failed to encompass essential components such as prevention, dissuasion, and reintegration, which are critical to a successful harm reduction framework. It also did not have adequate support or trust from public officials to perform successfully in a divided environment. Furthermore, funding drug rehabilitation programs within incarceration facilities could be beneficial. Even if penalties remain, these processes would provide support for prisoners struggling with addiction and enhance their recovery journey.

As Oregon has reverted Measure 110 through House Bill 4002, future research is needed to assess whether a return to traditional drug policy will yield positive outcomes after the initial introduction of harm reduction. Nevertheless, the results of Measure 110 remain significant in shaping the future of drug policy in Oregon and other states, guiding efforts towards fostering a healthier society.

Limitations and Future Research

While efforts were made to gather relevant data from reliable sources, this study does have several limitations. External variables affecting drug use such as fluctuating supply of illicit drugs, citizen mental health, and economic conditions can vary from year to year. Although policy regarding criminal penalties for both drug consumption and distribution plays a critical role in influencing drug use, these dynamic factors can also impact outcomes in public health.

Moreover, future research is essential to analyze the effects of Measure 110 and to conduct a more comprehensive examination of drug-related data in Oregon. Future researchers might consider undertaking a synthetic cohort study to facilitate a more accurate comparison between Oregon and other states, utilizing advanced analytical techniques. Methods like the difference-in-differences or the interrupted time-series model may provide more accurate quantitative data for measurable indicators of higher drug use. However, due to the limited information available online without access to university or college databases, there was not enough to conduct a higher-level mathematical analysis. Time constraints and lack of sufficient data restricted this study’s ability to perform deeper statistical calculations. The study’s comparison of Oregon to Utah and Nevada may be hindered by this limitation, leaving the strength of its findings regarding the numerical impact of Measure 110 weak. Nevertheless, this research still provides vital insight into the complexities of harm reduction found in Oregon and Portugal.

Additionally, the survey conducted in this study did not reach enough drug users facing similar challenges as those in Oregon. Insights from drug users going through rehabilitation could be invaluable in identifying the specific needs of the population in need of support. Conducting interviews or surveys with drug users in Oregon may enhance the findings of this study and provide deeper understanding of effective addition treatment strategies. The respondents who chose to respond to the survey also may have had limitations regarding unrepresentative samples, small survey size of 21 surveyed individuals, and lack of depth. The definition of harm reduction provided may have also unintentionally influenced responses by associating this idea with humane treatment, which more people may agree with than a more accurate representation of harm reduction. The study acknowledges this limitation and focuses more on the qualitative data drawn from the survey, such as the participant’s quotes, than quantitative numbers.

Furthermore, this study did not investigate deeper effects of drug law, such as their impact on Black and marginalized communities, which are disproportionately impacted by higher police surveillance. This study chose to investigate the implications of Measure 110 with comparison to Portugal’s harm reduction law and determine next best steps for public health policy. Future research studies may delve deeper into which communities were impacted more and how officials can address drug use in an equitable way that helps every citizen fairly.

Conclusion

Oregon’s harm reduction policy, Measure 110, has been associated with an increase in both illicit drug use and overdose deaths, mirroring an increase of drug use in states that maintained traditional drug laws from 2020-2023. This suggests that this policy was not more effective than other traditional drug laws and may warrant further research into potential negative effects. The findings of this study do not claim that Measure 110 actively damaged public health in Oregon, but rather that it did not accomplish its goal of lowering drug use in the three years of its standing and to pose potential sites of inquiry to reach a better outcome.

The ineffectiveness of Measure 110 could be attributed to three key factors: inadequate information sharing led to the underutilization of rehabilitation resources, funding delays that hindered efforts to make health centers accessible, and a lack of systematic support for drug users from healthcare professionals due to the failure of Oregon’s referral system. Portugal’s multidimensional approach to harm reduction illustrates that effective strategies in harm reduction extend beyond simple decriminalization and reach drug users through multiple institutions.

Survey responses from both drug-users and non-drug users indicate general support for harm reduction policies, however participants emphasized that successful implementation requires diligent preparation and support systems. Policymakers must carefully consider the implications of their policies during the implementation process, especially in the context of harm reduction where political divides and polarization may prevent a fair interpretation by the public.

While harm reduction has the potential to provide compassionate treatment for drug users and facilitate their journey to improved quality of life, it is essential for policymakers to assess their circumstances thoughtfully and establish a model with realistic expectations. Drawing on previous public health policies such as Measure 110 could valuably inform these choices. As one survey participant noted, “even failed policies can provide important insights. Since criminalization has clearly not resolved the problem entirely, we should continue investigating new policies such as harm reduction principles.”

Although Measure 110 did not achieve its intended outcomes, future policymakers can draw lessons from its shortcomings to establish more effective processes. Public health policy must adapt to the specific challenges faced by drug users to effectively address their needs. A well-researched and culturally aware approach to harm reduction could significantly enhance outcomes for drug users and pave the way for more humane drug policies worldwide.

Methods

Drug Usage Rates

To assess the impact of Oregon’s Measure 110 on drug usage rates, data was extracted on illicit drug usage for Oregon, Nevada, and Utah from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)42. Nevada and Utah were selected as control states as they are geographically close and have similar populations. In addition, Nevada and Utah both have strict drug laws, which allow for a comparative analysis of traditional drug laws versus harm reduction approaches.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), conducts an annual nationally representative survey with a sample size of approximately 70,000 participants. The survey provides data on tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, as well as mental health issues, substance use disorders, and treatment. NSDUH randomly selects household addresses to curate a diverse array of participants aged 12 years or older, resulting in a comprehensive dataset on specific types of drug and substance usage in each state.

Drug Overdose Mortalities

This study extracted data on drug overdose mortalities for the same three states through the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a governmental agency from the CDC. The mission of NCHS is to collect, analyze, and report health data to inform policies and initiatives aimed at improving public health. NCHS systematically gathers data on drug overdose mortalities by analyzing cause-of-death information from death certificates submitted by local and state medical examiners and coroners. The data on drug overdose mortalities is highly reliable, as it comes from officially reported death certificates, but there may be extraneous overdoses that were reported incorrectly or with a different cause of death.

To compare the states’ data on drug overdose mortalities to a nationwide trend, this study also retrieved national overdose mortalities data from NCHS. The agency processes death records received via the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program (VSCP) from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, allowing it to calculate the total overdose deaths annually.

Surveys

In order to gather qualitative insights, this study conducted an online survey to assess the effectiveness of harm reduction policies and identify key factors contributing to its success. This will help to analyze whether the empathetic approach underpinning harm reduction policies is realistic and effectively tackles drug abuse issues.

Recognizing that not all participants knew what harm reduction was, the survey included a definition of harm reduction so everyone had a base understanding. The survey was sent to a variety of people of different ages, genders, occupations, and generations. It was shared through public Instagram accounts and messages to assorted group chats based in the study’s geographic community. Those who chose to respond were of different political and ideological backgrounds with no identifiable trend in either direction. This survey was not shared in online channels or chatrooms related to harm reduction or political topics, in order to ascertain a general view of harm reduction by both drug and non-drug users. Survey participants were asked whether they had used drugs for recreational purposes before, and if so, to what frequency. This is an important demographic for the survey, as drug users have experiential understanding of the addictiveness of drugs and how effective anti-drug tactics are.

Table 3| Survey Questions

Q1: Name

Q2: Email address

Q3: Please check the following box if you are willing to participate in this study.

Q4: What generation are you in? Please select one.

- Generation X

- Millennial

- Generation Z

- Generation Alpha

- Other

Q5: Have you ever used drugs for recreational purposes in your lifetime?

- Yes

- No

Q6: If you answered yes to the previous question, how often did you use recreational drugs?

- Frequent (several times a week)

- Moderate (once a month)

- Rare (once every few months)

- Prefer not to say

- Not applicable

Harm reduction refers to policies that minimize the negative health, social or legal impacts of drug use. This may include lessening criminal penalties for illicit drug use, supporting a needle exchange program to ensure the safety of drug users, or the decriminalization of drugs altogether. Harm reduction policies intend to decrease drug use amongst citizens by providing alternate resources in lieu of incarceration. For example, some harm reduction policies include increased funding for therapy or treatment programs.

Q7: Have you ever heard of harm reduction before?

- Yes

- No

Q8: What are your thoughts about harm reduction policies? Do you support them?

Q9: What are some reasons you do/do not support harm reduction policies?

Q10: Do you know anyone personally affected by harm reduction policies? If yes, please elaborate.

Q11: Do you believe that harm reduction policies are effective in lowering drug use rates among civilians?

Q12: What are some specific reasons you believe harm reduction policies do/do not work?

Q13: What do you think about the current state of drug use in the United States right now? What do you think can be done to fix it?

Q14: Do you believe future policies should continue implementing harm reduction principles?

Ethics

Given that this paper addresses potentially sensitive topics such as drug use and overdosing, precautions were taken to ensure the reliability of the data and anonymity of the survey respondents. This study only utilized data reported by state and the federal government to ensure that it was as accurate as possible. The participants of the survey were informed about the purpose of the research and assured that their responses would remain confidential and untraceable to any individual. Only generalized characteristics, such as generation demographics and history of drug use, were presented with the qualitative data.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my parents for their support that made this paper possible.

References

- Lee, J. (2021). America has spent over a trillion dollars fighting the war on drugs. 50 years later, drug use in the U.S. is climbing again. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/17/the-us-has-spent-over-a-trillion-dollars-fighting-war-on-drugs.html [↩]

- Harm Reduction International. (2023). What is harm reduction? https://hri.global/what-is-harm-reduction/ [↩] [↩]

- Mann, B. (2024). How Portugal eased its opioid epidemic, while U.S. drug deaths skyrocketed. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/24/1230188789/portugal-drug-overdose-opioid-treatment [↩] [↩]

- Spencer, N. (2023). Does drug decriminalization increase unintentional drug overdose deaths? Journal of Health Economics, 91, 102798. [↩] [↩]

- Joshi, S., Rivera, B. D., Cerdá, M., Smith, R. A., Voss, L. M., & Johnson, S. R. (2023). One-year association of drug possession law change with fatal drug overdose in Oregon and Washington. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(12), 1277. [↩] [↩]

- Baldwin, G. T., Vivolo-Kantor, A., Hoots, B., Roehler, D. R., & Ko, J. Y. (2024). Current cannabis use in the United States: Implications for public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 114(S8), S624–S627. [↩]

- Moura, A. (2024). Made in Portugal: A recipe to fight the opioid crisis. Nova SBE Role to Play. https://roletoplay.novasbe.pt/content/made-in-portugal-a-recipe-to-fight-the-opioid-crisis [↩]

- Silvestri, A. (2015). Gateways from crime to health: The Portuguese drug commissions. https://asilvest.weebly.com/uploads/2/9/3/7/29376069/as_from_crime_to_health_report.pdf [↩] [↩]

- Waters, R. (2021, October 23). Portugal’s path to breaking drug addiction. Craftsmanship Magazine. https://craftsmanship.net/portugals-path-to-breaking-drug-addiction/ [↩]

- Moury, C., & Escada, M. (2023). Understanding successful policy innovation: The case of Portuguese drug policy. Addiction, 118(5), 967–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16099 [↩]

- Kristof, N. (2017, September 22). How to win a war on drugs. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/opinion/sunday/portugal-drug-decriminalization.html [↩]

- Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2021, May 13). Drug decriminalisation in Portugal: Setting the record straight. https://transformdrugs.org/blog/drug-decriminalisation-in-portugal-setting-the-record-straight [↩]

- Martins, C. F., & Faiola, A. (2023). Once hailed for decriminalizing drugs, Portugal is now having doubts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/07/07/portugal-drugs-decriminalization-heroin-crack/ [↩]

- Pressbooks. (2016). Drug use in history. https://pressbooks.howardcc.edu/soci102/chapter/7-1-drug-use-in-history/ [↩]

- U.S. Department of Justice. (n.d.). Opium and narcotic laws. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/opium-and-narcotic-laws [↩]

- American Addiction Center. (2024). History of drug abuse and addiction rehabilitation programs. https://drugabuse.com/addiction/history-drug-abuse/ [↩]

- Caulkins, J. P., Reuter, P., Iguchi, M. Y., & Chiesa, J. (2003). Drug use and drug policy futures: Insights from a colloquium. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/issue_papers/IP246.html [↩]

- Britannica. (2024). War on drugs | history & mass incarceration. https://www.britannica.com/topic/war-on-drugs [↩]

- The White House. (n.d.). A drug policy for the 21st century. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ondcp/drugpolicyreform [↩]

- United States Sentencing Commission. (2017). Mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses in the federal system. https://www.ussc.gov/research/research-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties-drug-offenses-federal-system [↩]

- Mann, B. (2021). After 50 years of the war on drugs, “What good is it doing for us?” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/17/1006495476/after-50-years-of-the-war-on-drugs-what-good-is-it-doing-for-us [↩]

- Ballotpedia. Oregon Measure 110, drug decriminalization and addiction treatment initiative. https://ballotpedia.org/Oregon_Measure_110,_Drug_Decriminalization_and_Addiction_Treatment_Initiative_(2020) (2024). [↩]

- T. Schick, C. Wilson. Oregon leaders hampered drug decriminalization effort. https://www.propublica.org/article/oregon-leaders-hampered-drug-decriminalization-effort (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Kubeisy, C. (2024). The drug review: Oregon’s Measure 110 has been a failed policy experiment. Good Drug Policy Institute. https://gooddrugpolicy.org/2024/02/the-drug-review-oregons-measure-110-has-been-a-failed-policy-experiment/ [↩]

- C. Klobucista, M. Ferragamo. Fentanyl and the U.S. opioid epidemic. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic#chapter-title-0-3 (2023). [↩]

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Facts about fentanyl. https://www.dea.gov/resources/facts-about-fentanyl (n.d.). [↩] [↩]

- Jackson County Combat Prevention. If you can see it, it can kill you. https://www.jacksoncountycombat.com/818/Get-The-Fentanyl-Facts (2023). [↩]

- S. Taylor, M. M. Paluszek, R. Rachor, G. J. McIntyre, G. F. Asmundson. Substance use and abuse, COVID-19-related distress, and disregard for social distancing: A network analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106754 (2021). [↩]

- F. Ornell, H. F. Moura, J. Scherer, A. C. Pechansky, A. von Diemen. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113096 (2020). [↩]

- CDC. Drug poisoning mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm (n.d.). [↩]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Addiction and health. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/addiction-health (2022). [↩]

- Davidson, K. F.-V., Ross, E., Powell, M., Cook, M., & Karson, A. (2021). Oregon officially reopens after 15 months of pandemic restrictions. Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/article/2021/07/01/oregon-reopening-state-restrictions-lifts-covid-19-pandemic-governor-kate-brown/ [↩]

- Oregon Health Authority. (n.d.). Fentanyl. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/preventionwellness/substanceuse/opioids/pages/fentanylfacts.aspx [↩]

- Bouttell, J., Craig, P., Lewsey, J., Robinson, E., Popham, C., Sandeman, L., & McCartney, F. (2018). Synthetic control methodology as a tool for evaluating population-level health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 72(8), 673–678. [↩]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). Population density data table: 2020 decennial census. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/population-density-data-table.pdf [↩] [↩]

- U.S. News & World Report. (n.d.). Rankings: Health care – Best States. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved June 16, 2025, from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/health-care [↩]

- X. Rêgo, M. J. Oliveira, C. Lameira, D. Cunha, S. Mateus, A. Ferreira, M. Maia, M. Cardoso, T. Neves. 20 years of Portuguese drug policy – developments, challenges and the quest for human rights. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy, 16(1) (2021). [↩]

- Garnett, M. F., & Miniño, A. M. (2024). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2003–2023. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db522.htm [↩]

- Weber Law. (2024). Utah alcohol and drug laws. https://www.law.ninja/utah-alcohol-drugs-marijuana/ [↩]

- Clay, R. A. (2018, October). How Portugal is solving its opioid problem. Monitor on Psychology, 49(9), 20. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/10/portugal-opioid [↩]

- Green, E. (2022). Money for Measure 110 addiction services finally arrives; Oregon auditors spot problems. Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/article/2022/06/02/oregon-measure-110-funding-addiction-treatment-audit/ [↩]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). (2023). About NSDUH. https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/about_nsduh.html [↩]