Abstract

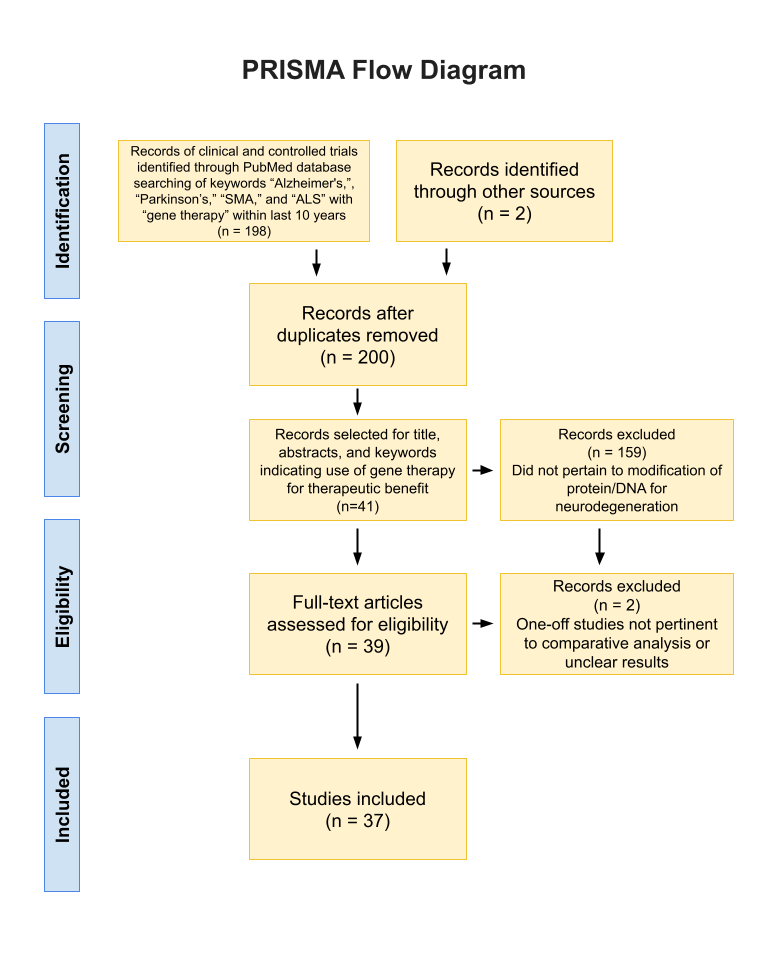

Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and spinal muscular atrophy are prevalent neurological conditions affecting millions worldwide. These disorders lead to the degeneration of neurons and muscles, which can result in a slow death without treatment. Recently, gene therapy has emerged as a potential solution. This review evaluates the efficacy of gene therapies in treating neurodegeneration and addresses the lack of awareness of gene therapeutic success. In this review, the PubMed and Google Scholar databases were used to find and analyze 36 peer-reviewed articles and one thesis. The manuscripts were analyzed to ensure each study was either a randomized or clinical trial. There is a wide variety of gene therapies existing for each disorder, with varying degrees of progress. Whereas Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s have few clinical trials, Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis have more. Many of these therapies were successful but had adverse immune effects. Furthermore, using an AAV vector was often safer than the delivery of a gene or editing components. Ultimately, science has made major strides in gene therapies for neurodegeneration. However, more work needs to be done to test these components on humans and then deliver them to the general public.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, gene therapy, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, spinal muscular atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Introduction

Background and Context

Neurodegenerative diseases result from progressive damage to the nervous system and related connections that operate mobility, coordination, strength, sensation, and coordination. None of these diseases have a cure. Due to their prevalence and irreversible harm, finding more effective treatment options is an imperative goal1.

This review aims to evaluate the efficacy of gene therapies in treating neurodegeneration and addresses the lack of awareness of gene therapeutic success in both the scientific community and the public, focusing on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). This paper also seeks to raise awareness of gene therapy as a therapeutic option.

Diseases and Current Treatments

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s Disease is the most common cause of dementia. By the late stages, individuals are not even able to carry a conversation or respond to their environment2. Traditionally, there are three stages of AD: preclinical AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia3.

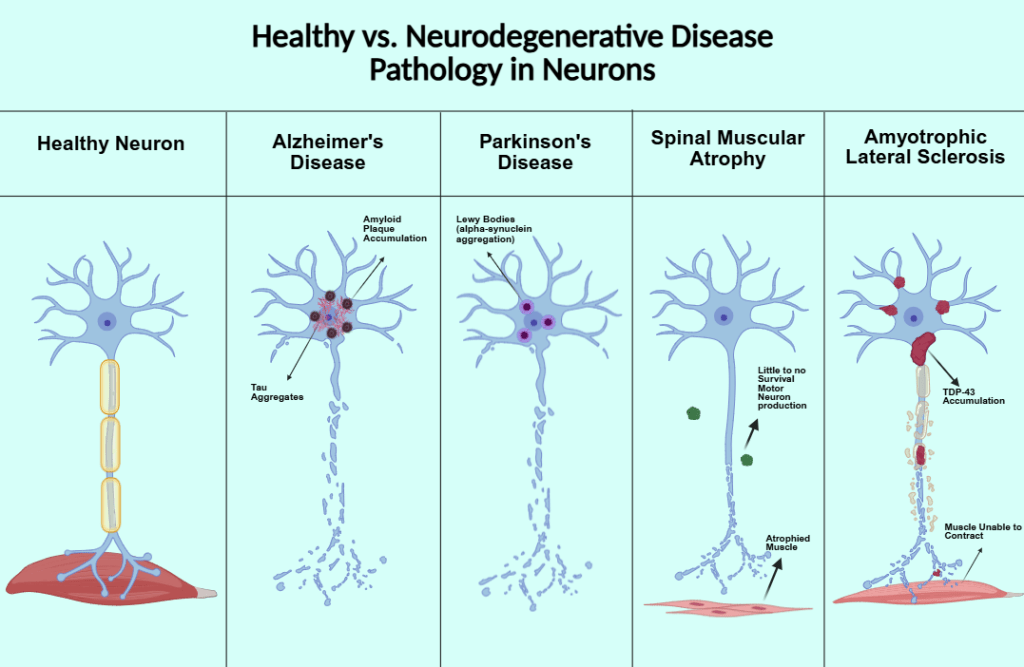

Two major hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles, also known as tau protein, and amyloid beta plaque. Tau protein is encoded by the MAPT gene. The protein is involved in the signaling cascade pathway, microtubule binding and assembly, cytoskeleton maintenance, cell signaling, and connecting actin and microtubules. During tauopathies, tau phosphorylation is increased, reducing its affinity for microtubules and destabilizing cytoskeletons in neurons. Phosphorylated tau forms tau aggregates that exert neurotoxic effects and contribute to neurodegeneration4. Amyloid-beta comes from Amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP). All vertebrates produce APP. The protein is involved in antimicrobial activity, tumor suppression, sealing leaks in the blood-brain barrier, promoting recovery from brain injury, and regulating synaptic function for memory consolidation. When soluble amyloid-beta binds to form oligomers, they take longer to clear from the brain or form toxic insoluble plaques, resulting in AD pathology5.

Two treatments, donanemab and lecanemab, have shown that by targeting and removing amyloid beta, disease pathology is reduced, including the prolonging of cognitive and functional decline2.

About 6.9 million Americans 65 and older live with AD. As of 2011, the incidence was 910,000 people, a number expected to only increase6. Age is the greatest risk factor. Women are at higher risk for AD than men- 67% of AD patients in America are women, most likely since females, on average, live longer. Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were more likely than White adults to have Alzheimer’s. Black older adults are twice as likely and Hispanic adults are 1.5 times as likely as White older adults to have Alzheimer’s or other dementias.6 This difference is most likely due to differences in life experiences, socioeconomics, and health. According to one study, dementia incidence was highest for African Americans, intermediate for Latino/Hispanic adults, American Indian/Native Alaskans, Pacific Islanders, and White adults, and lowest among Asian American adults6.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by uncontrollable movements, such as shaking, stiffness, and difficulty with balance and coordination7. This disease is caused by the death or impairment of neurons in the basal ganglia, causing decreased dopamine production. Without dopamine, motor skills are impaired. The cause of death of these neurons is unknown7.

One major pathological marker of PD is the aggregation of the protein alpha-synuclein (𝛼-syn), producing Lewy bodies8. It seems to be involved with synaptic plasticity and acts as a phospholipase inhibitor. Mutated, 𝛼-syn disrupts the association of 𝛼-syn and their presynaptic location. Synuclein may also act as a fatty-acid binding protein and in neurotransmitter release9. Overexpressed, it inhibits neurotransmitter expression, inhibits exocytosis, and causes abnormalities in olfaction, gastrointestinal motility, and motor activity9.

Another affecting factor of Parkinson’s Disease is Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a neurotransmitter produced by the GAD1 gene10. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, and its functions are maintained through the interaction of GABA and calcium-dependent neurotransmission. Decline in Ca2+/GABA leads to weakened protective barriers, including the blood-brain barrier. Patients with early PD have a decreased sense of smell, depression, and gastrointestinal problems, symptoms related to a deficit in GABA10.

One million people in the US have Parkinson’s Disease, and this number is expected to rise by 2030. 90,000 people are diagnosed with PD annually. Age is the main risk factor11. Men are 1.5 times more likely to have PD than women12. The mean prevalence of PD is highest among White men and lowest among Asian women. PD prevalence is about 50% in Black and Asian adults compared to White adults, with prevalence ratios of 0.58 for Blacks and 0.62 for Asians. PD incidence also similarly varied by race12.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a group of genetic diseases affecting the motor neurons of infants, causing skeletal muscle weakness13. Symptoms include respiratory infections, scoliosis, and joint contractures. The most common form of SMA is caused by a mutation in the survival motor neuron 1 gene (SMN1), which produces survival motor neuron protein (SMN). A similar gene to SMN1, SMN2, makes less of the protein, but higher levels of SMN2 are associated with less severe forms of the disease, making it an attractive option for gene therapeutic targets13.

SMN plays a role in ribonucleotide assembly, transport and local translation of RNA, regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics, endocytosis/autophagy, and mitochondrial/biochemical pathways. In SMA, the mutated version of SMN2 lacks exon 7, which disrupts the splicing process and results in a truncated, non-functional protein14.

There has been more extensive gene therapeutic research done on SMA, leading to three approved medications to treat SMA by genetically increasing SMN production- nusinersen (Spinraza™), onasemnogene abeparovec-xioi (Zolgensma™), and risdiplam (Evrysdi™)13.

95% of SMA cases are 5q SMA. Its incidence is approximately 10 in 100,000 births and its prevalence is 1-2 in 100,000 due to the exceptionally shortened life expectancy15. Statistics suggest that males have only a slightly increased risk16. There are significant differences in ethnic prevalence, with a one-copy of exon 7 carrier frequency of 2.7% in Caucasians, 2.2% in Ashkenazi Jews, 1.8% in Asians, 1.1% in African Americans, and 0.8% in Hispanics. African Americans face higher risk since they have a higher frequency of alleles with multiple copies of SMN1 (27% versus 3.3-8.1%)

ALS

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, formerly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, is a neuromuscular disease affecting motor neurons. As the motor neurons degenerate, the muscles no longer receive any messages and begin to atrophy. Eventually, the brain is unable to control any voluntary movements including breathing. ALS progresses quickly- patients die within three to five years of diagnosis compared to 10-20 years for AD and PD. Mutations in either TARDBP, which codes for the protein TDP43, or the SOD1 gene, which codes for an enzyme breaking down harmful oxygen molecules, have been implicated in ALS.

TDP43 is expressed in nearly all tissues. It may promote neuronal survival and neuroprotection. TDP43 also has an indirect role in mitochondrial function and the cell cycle. TDP-43 sustains mRNA levels of synaptic proteins, choline acetyltransferase, and other proteins involved in neurological diseases. Furthermore, its binding to target RNAs promotes neuronal function and integrity19.

SOD1 is a gene producing an antioxidant enzyme protecting the cell from oxygen toxicity20. It may also prevent protein aggregation, act as a transcription factor, regulate transcription, and regulate RNA stability20.

Annually, the incidence of ALS is 1-2.6 cases per 100,000, whereas the prevalence is 6 cases per 100,0001. ALS is 20% more common in men, but as age increases, the incidence becomes more equal22. For undiscovered reasons, military veterans are much more likely to be diagnosed with ALS. It is more common in Whites than in African Americans or other races. African Americans seem to live longer after an ALS diagnosis23.

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy is emerging as a new, promising method of treating numerous diseases. There are numerous methods of gene delivery24.

This article references numerous types of RNAs, and other technologies used in gene therapy, some of which will be defined below.

- Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) helps form ribosomes24.

- Messenger RNA (mRNA) provides the instructions to make proteins. mRNA therapy is geared toward producing functional protein that may be missing or malfunctioning24.

- microRNA (miRNA) is a small single-strand RNA that targets multiple mRNAs to regulate many genes24.

- Small interfering RNA (siRNA) are double-stranded RNA molecules targeting a specific mRNA to prevent the production of unwanted proteins24.

- Transfer RNAs (tRNA) carry amino acids to the ribosome for protein production. Suppressor tRNA therapies override harmful mRNA instructions by stopping protein production24.

- Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) are fake, single-stranded chains of molecules targeting a specific mRNA. These therapies alter protein production by silencing a gene and altering mRNA production24.

- Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a non-enveloped virus engineered to deliver DNA or gene therapeutic components to target cells. It is one of the safest strategies for gene therapies25.

- Clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 is a gene editing tool involving a guide RNA to match the target gene and Cas9 (CRISPR-associated protein 9)- an endonuclease causing a double-stranded DNA break allowing modifications to the genome. A synthetic single guide RNA (sgRNA) guides the Cas9 to the target and binds to the DNA26.

Problem Statement and Rationale

This review aimed to find which gene targets were being investigated and which had been shown as potential therapeutic targets for different neurodegenerative diseases in order to compile the different methods of combating these diseases.

Rationale for Disease Selection

Initially, this review was intended only to cover Alzheimer’s Disease, as AD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease. However, after initial article searches on PubMed, the need to cover more neurodegenerative diseases was apparent as gene therapies have been attempted on various neurodegenerative diseases.

Therefore, Parkinson’s Disease was selected as it is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease. SMA was chosen due to its genetic basis as a neurodegenerative disorder, with much genetic research already being done. Finally, ALS was chosen after a mentor’s recommendation to research TDP-43, the protein behind the disease.

Significance and Purpose

Because gene therapy is novel and advancing, investigating gene therapy in neurodegenerative diseases can offer a potential treatment that can improve the lives of those with these currently incurable diseases.

Objectives

The purpose of this paper is to explore various methods and targets of gene therapies combatting certain biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease. Such an exploration will shed light on our current success with different types of gene therapies and future steps we need to take. This paper also seeks to raise awareness and knowledge of gene therapy as a potential therapeutic option.

Scope and Limitations

This review includes peer-reviewed articles from the PubMed database published between 2010 to 2024. Any paper on pre-researched biomarkers of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, SMA, and ALS was considered. To ensure the accessibility of the research findings, this review only presents the statistically significant results.

Methodology Overview

To include a wide variety of data, numerous PubMed searches were conducted to find gene therapy trials targeting specific hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. For example, amyloid-beta targeting treatments for Alzheimer’s, 𝛼-synuclein for Parkinson’s, TDP-43 for ALS, and SMN protein for SMA were all used as potential keywords. Numerous keywords were used in these searches to achieve 37 articles. Once at least three articles per biomarker of disease were compiled, they were organized by the specific disease and then further by the type of biomarker being targeted. Each article was analyzed through a summary of keywords, methodology, and results.

Results

Alzheimer’s Disease

| Alzheimer’s Disease | |||||

| Target | Gene/ Protein | Function | Method | Results | Source |

| Amyloid Plaque | CD33 | Transmembrane Protein Receptor | Reduced with artificial miRNA | knockdown of CD33 in earlier-aged mice led to a more effective reduction of amyloid plaque | 27 |

| APP | Production of amyloid plaque | Deleted base pairs in the 3’UTR (untranslated region) and insertion into mice zygotes | the deletion efficiency of the UTRs correlated inversely with plaque accumulation | 28 | |

| CRISPR-induced insertion/deletions using guide RNA of SW1 allele | CRISPR-induced indels through an SW1 gRNA led to a 60% reduction in Aβ40 (CSF) levels and a 50% reduction in Aβ42 (Plaques) | 29 | |||

| Protective APP variant in Icelanders showing specific beneficial change to gene | 40% reduction in amyloidogenic peptides, protects against cognitive decline | 30 | |||

| Simvastatin- medication suppressing miRNA which targets noncoding RNAs in AD | lowered plaque levels and led to improvements in cognitive tests such as the Morris Water Maze Tests | 31 | |||

| APOE | Fat and cholesterol transport and mammalian fat metabolism | siRNAs slice and modify APOE, silencing the gene | editing was effective, silencing APOE, reducing the Amyloid burden | 32 | |

| Tau Protein/ Neurofibrillary Tangles | MAPT | Production of Tau | Adenine base editor to target P301S mutation | significant reduction in total and phospho-tau levels in mice | 33 |

| Tau-targeting ASO | dose-dependent reduction in CSF tau concentration- a greater than 50% mean reduction from the baseline | 34 | |||

| Administration of specific ASO BIIB080 | dose-dependent significant reduction in CSF tau and phospho-tau, PET scans showed a reduction from baseline across all assessed brain regions in tau biomarkers | 35 | |||

Parkinson’s Disease

| Parkinson’s Disease | |||||

| Target | Gene/ Protein | Function | Method | Results | Source |

| Alpha-synuclein (𝛼-syn) | GBA1 | Codes for GCase, degradative enzyme in the lysosome | Ambroxol, pharmacological chaperone of GCase increasing number of properly folded proteins | Brain GCase activity increased in all three types of mice in study 1; therapy was well tolerated, and a 35% increased level of CSF GCase in humans was observed (study 2) | 36,37 |

| AAV-GBA1 gene therapy to protect midbrain dopaminergic neurons in mice with A53T mutation | wild-type GCase activity was increased and 𝛼-syn aggregation decreased, prevented 𝛼-syn mediated degradation of neurons by 6 months | 38 | |||

| AAV-mediated gene therapy injecting the mutated 𝛼-syn (rAAV-SynA53T) followed by a vector coding for GBA1 (rAAV9-GBA1) | enhanced GCase activity, reduced 𝛼-syn levels, and led to improved survival of dopaminergic neurons | 39 | |||

| SNCA | Produces 𝛼-syn | Introduction of nonsense mutation in SNCA allele through CRISPR in hiPSCs | modified stem cells had no 𝛼-syn expression while retaining healthy cell morphology, differentiation ability, and reduced vulnerability to the dopaminergic neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium | 40 | |

| Usage of CRISPR-Cas9 to delete SNCA alleles in hESCs, showing resistance to 𝛼-syn aggregation | SNCA+/- and SNCA-/- cell lines showed significant resistance to 𝛼-syn aggregation | 41 | |||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | GABA | Inhibitory neurotransmitter associated with movement | AAV2-GAD delivery into the subthalamic nuclei; one year-post observation for retainment of initial improvement | significant positive difference in the change in mean UPDRS motor scores (scale from 0 to 108) | 42,43,44 |

| analyze improvements due to GAD insertion into the subthalamic nucleus; metabolic imaging data found treatment-related polysynaptic brain circuits | GADRP, which only appeared in those receiving the gene therapy, was the only pattern of neural networks associated with clinical improvement in PD | 45 | |||

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy | ||||||

| Target Protein/ Gene | Function | Medication | Function | Method | Results | Source |

| SMN Protein SMN2 | homeostasis, splicesome assembly, mRNA trafficking, influences mitochondria | Nusinersen | Antisense Oligonucleotide (ASO) altering the splicing of the SMN2 mRNA, ensuring accurate splicing of SMN2 transcripts (promoting inclusion of exon 7) | Intrathecal injection aiming to increase SMN protein | SMN protein levels more than doubled 9 to 14 months post-dose for 6 or 9 mg (study 1); Recipients of 12 mg dose had improved CHOP- INTEND motor function scores, increased muscle action potential, no permanent ventilation (study 2) | 46,47 |

| Evaluation of motor milestone responses and event-free survival | 51% of the 73 nusinersen-treated infants had a motor milestone response, likelihood of event-free survival was greater | 48 | ||||

| Risdiplam | oral, SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modifier | SUNFISH study- randomized, escalating doses with increasing SMN protein | SMN protein levels increased with higher dosage, increases were maintained over 24 months, with improvements and stability in motor function | 49 | ||

| 24-month check of risdiplam administration | 32% had a significantly greater change in 32-item Motor Function Measure, and 58% showed stabilization | 50 | ||||

| FIREFISH study- infants given risdiplam once a day at 0.2 mg/kg, increased to 0.25 mg/kg a day after 2 years | 18 infants (44%) were able to sit without support for at least 30 seconds | 51 | ||||

| RG7800 | oral SMN2 splicer designed to foster alternative splicing of SMN | two trials of RG7800 increased full-length SMN2 mRNA expression | full-length SMN2 mRNA expression in healthy patients and almost doubled SMN protein levels | 52 | ||

| RG7800 tested in a single ascending dose in healthy volunteers and in those with Type 2 and 3 SMA, RG7916 (risdiplam) tested in healthy volunteers | found effective in increasing full-length SMN2 mRNA at dose-dependent increases | 53 | ||||

| Onasemnogene abeparvovec (AVXS-101) | acts as a delivery mechanism of SMN gene | delivered to participants less than 6 months in age with biallelic mutations in SMN1 and SMN2 | 13 out of 22 were able to sit independently for 30 seconds or longer at the end of the 18-month study versus 0 of the 23 untreated patients from the control | 54 | ||

| Self- complementary AAV9 vector crossing the blood-brain barrier | group with the low motor score achieved unassisted sitting later than the late dosing group, with a CHOP-INTEND mean gain of 35.0 points from a mean baseline of 15.7 | 55 | ||||

| SPR1NT trial- single intravenous infusion with 24-hour safety monitoring | all achieved independent standing before 24 months, with 14 walking independently, none required permanent ventilation or additional support | 56 | ||||

| 5-year-later follow-up trial for infants with SMA treated with intravenous AVXS-101 | All patients in the therapeutic dose cohort remained alive without needing permanent ventilation, maintaining motor milestones | 57 | ||||

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | |||||

| Target | Gene/ Protein | Function | Method | Results | Source |

| TAR DNA binding protein 43 | TARDBP | Makes TDP-43 | allele-specific siRNA to diminish mutant G376D form of TDP-43 | siRNA shown to be specific to the mutant form while excluding the wild-type allele, silenced mutated TARDBP and led to reduced phenotypic expression of the mutation | 58 |

| m6A RNA methylation, a reversible epigenetic post-transcriptional RNA modification | m6A RNA methylation found association between m6A modification and TDP-43 | 60 | |||

| SQSTM1 | Makes protein P62, which plays an important role in bone remodeling | regulate SQSTM1 by mimicking a suppressor of miRNA-183-5p (antagomir) | antagomir (blocking miRNA) reversed SQSTM1 suppression and reduced TDP-43 levels | 59 | |

| SOD1 | SOD1 | gene producing an antioxidant enzyme protecting the cell from oxygen toxicity | Tofersen- ASO degrading SOD1 mRNA via intrathecal administration | difference in CSF SOD1 concentration between the tofersen groups and the placebo groups was 2%, -25%, -19%, and -33%, respectively for each cohort, showing the benefit of large doses of tofersen in reducing SOD1 expression | 61 |

| G93A-SOD1 mouse model of ALS, using CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the mutant SOD1, delivering components via an AAV vector | reduced mutant SOD1 protein by about 2.5 fold in the lumbar and thoracic spinal cord, which led to reduced muscle atrophy and improved motor function | 62 | |||

| delivered via rAArh10, a recombinant serotype of an AAV, delivering an artificial microRNA called miR-SOD1 as a silencing mechanism through intrathecal administration | silencing of SOD1 in mice delayed both disease onset and death and significantly preserved muscle strength and motor and respiratory functions, rAAVrh10-miR-SOD1 in NHPs significantly and safely silences SOD1 in lower motor neurons | 63 | |||

| AAV9 delivered SOD1 shRNA to slow disease progression through a single peripheral injection of AAV9-SOD1-shRNA | mice survival was increased by 39% when treatment initiated at birth, with significant reductions seen by delaying disease onset and slowing disease progression, immunoblotting lumbar spinal cord from monkeys revealed an 87% reduction in SOD1 protein levels | 64 | |||

Comparison

Analyzing existing techniques of gene therapy is a key method in determining next steps.

For every disease, a summary of the gene therapies is provided, followed by ordering them from least to most effective. The studies will be ordered first by the level of research progression (cell lines, then mouse models, then clinical trials), then by numerical results, any reported adverse effects acting as a tiebreaker.

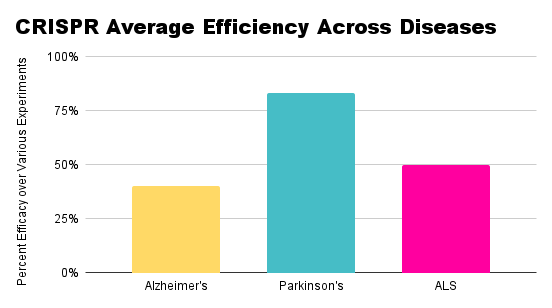

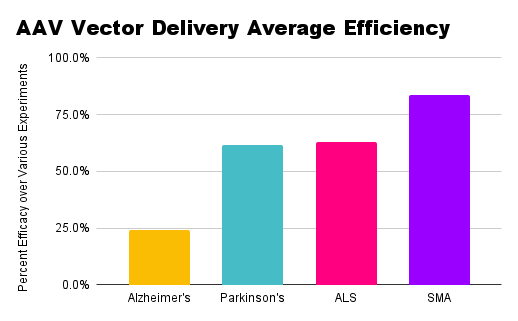

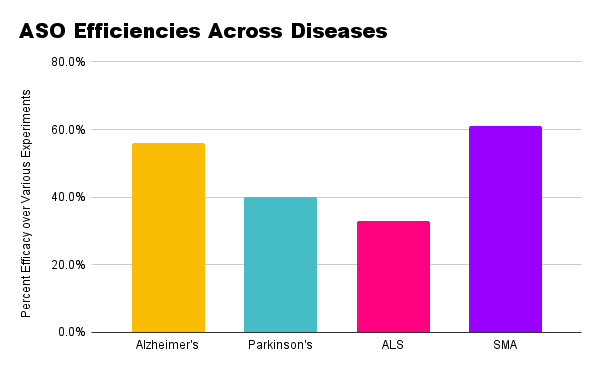

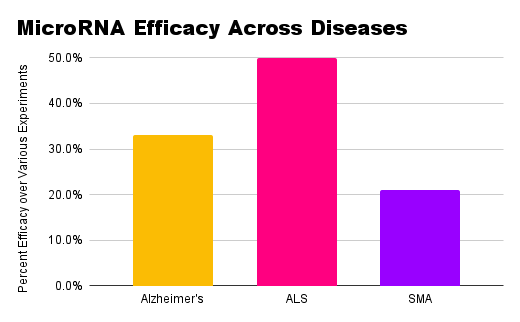

For AD, gene therapy is still not fully tested on humans. Delivering genetic components through an AAV vector has shown to be effective: whether targeting CD33 through miRNA or delivering an adenine base editor for MAPT, AAV vectors ensured efficient and safer delivery27,33. However, inserting edited genes into zygotes was inefficient as only 14 out of 49 injected mice from the zygotes contained the gene therapy28. The use of CRISPR itself was efficient both in the aforementioned mice zygote study and in the deletion of the Swedish APP allele, decreasing amyloid plaque. This also reflects that editing genes in isolated cells is easier than in mouse models despite using the same delivery method, underscoring the complexity of translating gene therapy. Further RNA suppression through medication, splicing siRNAs in APOE, and ASOs in the Tau gene was also relatively successful, with ASOs acting efficiently. However, these techniques have only worked so far in models and have not been clinically tested. More literature is available regarding amyloid plaque than Tau protein, suggesting that Tau protein gene therapy has further potential to be explored.

Ranked:

- CRISPR editing of the APPswe mutation in fibroblasts had an approximate 60% reduction in plaque levels29.

- CRISPR study of mice embryos involving the editing of the 3’UTR of APP, low deletion efficiency (10-30%)28.

- NG-ABE8e corrected the MAPT gene with an editing frequency of 16.6% ± 0.8% (Morris Water Maze zone crossing frequency of 50%)33.

- Early AAV delivery of miRNA- CD33 mRNA transcripts were significantly reduced by 30.1%, mirrored by a 25.1% and 30.8% decrease in Aβ40 and Aβ42 (slightly reduced levels of TREM2, which regulates inflammatory response)27.

- A673T mutation in APP reduced plaque buildup by 40%30.

- MiR disabling through Simvastatin on mouse models led to overlap between healthy and treated mice (~70% control (non-AD) group and the ~60% simvastatin group)31.

- Silencing APOE reduced APP6E10 positive plaque burden by 86% (female) and 70% (male)32.

- ASOs- dose-dependent reductions in tau of 30%, 40%, 49%, and 42% when patients were given 10 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg monthly, and 115 mg quarterly, respectively. (Mild to moderate adverse events were reported in 94% of MAPT-treated patients, compared to 75% of placebo-treated patients)34.

- Simvastatin- amyloid plaque expression in humans was reduced by about 36%, but nine people (11.25%) left the study due to side effects31. ‘

- Targeting MAPT through BIIB080 led to a 38-63% decrease in tau protein35.

In Parkinson’s Disease, the major targets of gene therapy were Glucocerebrosidase, SNCA, and GAD. One medication, Ambroxol, showed itself to be effective- both in models and preliminary clinical trials, 𝛼-syn levels decreased in the brain. The use of AAV vectors was shown to be efficient. AAV vectors were used both to deliver the defunct gene to the cells, which reduced aggregation of 𝛼-syn, and to introduce the A53T mutation and correct it with a code for GBA1 in mice and NHPs38,39. Similarly, another biomarker associated with PD was GABA, coded for by the GAD gene. In both AAV-mediated delivery of GAD and direct insertion into the subthalamic nuclei, clinical benefit and physiological changes were noted, though targeting 𝛼-syn was more clinically beneficial42,45. However, neither of these therapies was able to completely eradicate 𝛼-syn, a key biomarker of PD. The direct targeting of the SNCA gene was more effective than using the GBA1 gene as an association with 𝛼-syn. In the studies of SNCA disabling, CRISPR was used on human-derived stem cells to disable the SNCA gene, and the resulting cells showed significant resistance to 𝛼-syn40,41. Like in Alzheimer’s, the current Parkinson’s research shows the effectiveness of delivery methods such as CRISPR and an AAV in directly targeting the gene of a known biomarker for the disease.

Ranked:

- HiPSC lines with knocked-out SNCA led to 0% of the edited cells with 𝛼-syn and 82% of the cells resistant to neurotoxicity40.

- CRISPR deletion of SNCA in hESCs led to 83% reduction of Lewy-like structures41.

- α‐synuclein down in brainstem (19%) and striatum (17%) in ambroxol‐treated SNCA mice; GCase levels up by 19%36.

- AAV-GBA1 therapy reduced the molecular weight of 𝛼-syn by 40% and reduced the number of 𝛼-syn aggregates38.

- rAAV for SynA53T (mutated 𝛼-syn protein) led to a 57% reduction in cell loss in mice, whereas in NHPs, treatment led to a 61% reduction in cell loss. GCase levels increased by 77.4%, and 𝛼-syn burden was reduced by 62.98%39.

- Clinical trial of AAV2-GAD, UPDRS scores for recipient group decreased by 23.1% as opposed to the control’s 12.7%42.

- Administration of a clinical trial of Ambroxol increased GCase by 35%37.

- Clinical trial of AAV2-GAD delivery 12 months post-treatment, response rate to the medication (25% increase in UPDRS scores) was 62% in the AAV2-GAD group, compared to the sham group (23.8%)44.

- Clinical trial delivering GAD (AAV) led to 93.3% (14/15) of the subjects exhibiting an increase in GADRP expression45.

Genetically, SMA has already been explored thoroughly. This paper highlights three of the already approved gene therapies for SMA. Nusinersen is an ASO splicing SMN2 for accurate transcripts of the RNA, and in the necessary doses, it yielded significantly larger amounts of SMN protein mirrored by increases in motor function and ability46–48. Risdiplam is a splicing modifier of the SMN2 pre-mRNA, and it also increased motor function and SMN protein, though not as significantly as those receiving nusinersen, suggesting that risdiplam needs further testing49–51. Onasemnogene abeparvovec, delivering the SMN2 gene to patients, was delivered both through an AAV vector and direct intravenous injection, with increased motor function and SMN production. Though still less successful than nusinersen, this therapy is incredibly efficient when administered in the early stages of disease, prompting future research efforts toward early detection54–57. All the splicing modifiers promote the inclusion of exon 7 to foster proper protein folding and the full, non-mutated form of the SMN2 mRNA, so future gene therapeutic research should aim to do the same. All these therapies target SMN2, which makes less protein than the SMN1 gene. Future gene therapeutic research should also spend some time researching how to disable and correct SMN1.

Ranked:

- Nusinersen, 41% (interim) and 51% (final) of infants had motor milestone response48.

- FIREFISH study (risdiplam), 44% infants sat without support for at least 30s51.

- Risdiplam, 32% of patients improved scores, and 58% showed stabilization50.

- Nusinersen, 75% of participants alive, 63% reached developmental milestones47.

- Onasemnogene abeparvovec, 59% sat independently for 30+ seconds at 18 months, 91% free of permanent ventilation at 14 months54.

- AVXS-101, 92% sat unassisted for 5+ seconds at 24 months post-treatment, 75% sat unassisted for ≥30 seconds55.

- SUNFISH study of Risdiplam, dose-dependent increase in blood SMN protein49.

- SPR1NT trial, 100% of children stood independently, 93% of them within the normal WHO developmental window56.

- START trial (Onasemnogene abeparvovec), 100% of patients free of permanent ventilation57.

- SMN2 splicing modifier RG7800 increased SMN protein levels by up to 100%52.

- Nusinersen, SMN protein levels increased by 118% and HFMSE scores increased by 17.6% for 9 mg46.

- 3 mg risdiplam and 5 mg risdiplam had protein increases of 125% and 151%53.

For ALS, the two major targets were TAR DNA binding protein 43, coded for by the TARDBP gene, and the SOD1 gene. Using silencing methods for TARDBP, from designing a specific siRNA to finding an association between miRNA-183-5p and the SQSTM1 gene, researchers were able to significantly reduce aggregated TDP-43 levels58,59. Similarly, when targeting SOD1, ASOs were successful in treating ALS. Tofersen, an ASO medication degrading SOD1 mRNA, led to significant reductions in SOD1 levels in large doses. However, smaller doses yielded less significant results61. AAV vectors were also used to silence the SOD1 gene. One used CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the mutant SOD1 model of ALS, one used a recombinant AAV vector to deliver a silencing microRNA, and another used AAV9 to deliver SOD1-shRNA to mice models to suppress SOD162–64. In all cases, significant reductions of SOD1 and increased motor function were observed. These methods of AAV-mediated silencing of a gene proved more efficient than some of the other aforementioned modifications of SOD1 or TARDBP, displaying itself to be a significant avenue for future gene therapeutic research.

Ranked:

- siRNAs for TARDBP in HAP1 and HeLa cell lines led to 47% decrease in m6A methylation60.

- miR-183-5p antagomir decreased aggregated TDP-43 by 50%59.

- siRNA diminished mutant TDP43G376D, found that fibroblasts with TDP-43 had a 75% reduction58.

- CRISPR-SaCas9 to disrupt SOD1 expression in mice had 50% more motor neurons at end stage and displayed a 37% delay in disease onset and a 25% increase in survival, and genome editing led to a 2.5-fold reduction in mutant SOD1, as well as a 92% reduction in mouse neuroblastoma-spinal cord-34 cells62.

- rAAVrh10-miR-SOD1 led to SOD1 reduction of 3% (lumbar), 65% (thoracic), 92% (cervical cord) in marmosets; 21% extension of survival in mice63.

- shRNA to reduce SOD1 mutants led to an 80% reduction in SOD1 protein levels in mice and an 87% reduction in monkey SOD1 protein levels64.

- Clinical trial of Tofersen led to 33% decrease in CSF SOD1 (100 mg), 19% (60 mg), 25% (40 mg), and -2% (20 mg)61.

Comparing therapeutic approaches across diseases, CRISPR has emerged as a popular method of editing or silencing genes, as seen in the rankings above.

A very popular delivery method, regardless of the specific mRNA used for editing, is an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have been a significant factor in splicing and editing genes.

Though less prevalent in this review, microRNAs, whether directly or indirectly used or targeted, showed significant associations with disease pathology and protein aggregation.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were also utilized (though not as frequently) in genetic editing.

Discussion

Restatement of Key Findings

Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Spinal Muscular Atrophy, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis have all shown success to a certain degree in being treated through gene therapy. In Alzheimer’s, despite lack of clinical trials, existing gene therapeutic trials have yielded promising results. Similarly, PD has only recently begun treatment using gene therapy. Mutant 𝛼-synuclein has been reduced via ambroxol, through GCase/GBA1 RNA delivery, and disabling the SNCA gene. Spinal Muscular Atrophy has progressed much further in terms of exploring gene therapeutic treatments. Medications nusinersen, risdiplam, and onasemnogene abeparvovec all saw significant increases in functional SMN protein levels, especially with higher doses of the medication. In ALS, blocking both mutant TARDBP and SOD1 led to decreases in protein aggregates and other biomarkers of disease.

Implications and Significance

Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, and SMA have no cure. Furthermore, their devastating symptoms and progression make these diseases a major issue for millions around the world.

The major implication of this article is the importance of early detection of disease. As many trials have shown, those getting treatment when the disease has not yet progressed very far have made excellent strides in getting better, whereas those who got treatment later did not see as many improvements. The findings in these studies show how important it is that diseases be detected early.

These results also show that symptoms of these diseases have shown progress in being alleviated, in some cases even returning almost to normal. In diseases as prolific as these, such results are extremely significant, especially since it shows that society is scientifically approaching possible solutions to these diseases.

Connection to Objectives

The content and organization of this paper, which addresses numerous different genetic targets, and the basic techniques used to improve disease pathology for all four diseases, then evaluating which methods seem most effective, accomplishes its need to detail current progress within gene therapy while delivering the information relatively clearly enough to reach a wider audience. However, this paper concedes that it may not reach the scope of its goal due to the unfortunate reality that much of the general population does not seek out scientific publications such as this one.

Recommendations

Certain studies did not report results of medications given in smaller doses or did not use a large enough sample size. More representative trials of gene therapy can ensure more accurate and representative results. Another recommendation would be to generate a dose-response curve- rather than only testing two to four different dosages. This way, we do not have to ignore small doses. Finally, while cell lines and mouse models are valuable models, neither can accurately capture the workings of the human mind and how it interacts with other parts of the body. One step toward bridging this gap is the use of mini brain organoids, which are three-dimensional and better stimulate the brain.

To direct future research, gene therapy can be aimed at more common conditions. This would expand the market for gene therapy, making it more affordable65. Gene therapies should also focus on restorative therapy, such as replacing cells damaged or lost due to events such as cardiac arrest or cancer65. Finally, one major avenue for gene therapeutic study is the method of delivering therapy. Though viral vectors such as AAV are effective, they may lead to increased immune responses. Extracellular vehicles can be engineered to deliver therapeutic components by taking advantage of cells’ natural mRNA loading mechanisms, reducing immune impacts and cross biological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier66. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) use positively charged molecules to surround the negatively-charged genetic material while evading immune responses66. One more non-invasive and non-viral method is using focused ultrasound to open up the blood-brain barrier, generating a positive immune response and allowing administration of gene therapy- a technique that has already shown to lower amyloid and tau for AD65.

Limitations

Safety and Side Effects

One major limitation is the removal of functional genes and proteins. Since a lot of these gene therapies are inclined toward disabling and deleting the target gene, functional strains are also removed, resulting in serious adverse effects. Furthermore, terminally ill patients can underreport side effects due to hope bias. Some scientists may also overlook side effects for the sake of finding adequate evidence supporting their hypothesis.

Gene therapy still has numerous safety issues. The earliest gene therapy studies showed health risks such as toxicity, inflammation, and cancer67. In this paper, at least half of the studies explicitly mentioned adverse effects. Safer techniques have developed, but since these techniques are relatively new, risks are unpredictable, focusing research on ensuring safety. Many of these medications use a viral vector to deliver gene therapy, which the body’s immune system might see as an intruder, leading to harmful immune system reactions. Some of these gene therapies might also target the healthy cells or wrong DNA68. Vectors with a friendlier immune reaction are being explored, such as stem cells and liposomes, particles that carry the therapeutic genes to target cells and pass the genes into cell DNA68. Nanoparticles are also being explored as they are less likely to cause an immune reaction and easier to modify for specificity69.

Cost and Affordability

Gene therapy costs no less than 1 million dollars, making it currently inaccessible to the majority of the world. The costs of research funding, clinical translation, and the complexity of current manufacturing processes lead to a price tag of US$500,000 to $1,000,000 (compared to the $0.0002 to $0.013 per tablet for traditional medicines)70. Since gene therapies target much rarer diseases, the market demand is much smaller, making cost per patient higher. Finally, as gene therapies are only (supposedly) used once, the costs of a single dose rise70.

With time, as technology inevitably advances, costs will come down as production becomes more efficient and market competition increases70. However, in the short term, bioinformatic data collection and analysis can lower costs70. Governments and pharmaceutical companies can also collaborate to reach a more reasonable price tag71. Some suggestions are to focus on procedures that can be done in the body or to develop techniques already deemed to be safe71.

Practicality and Scalability

One major hindrance to scalability is the current lack of efficient production methods. Traditional methods for AAV production lead to low yields, making the process expensive and inefficient72. Furthermore, gene therapy manufacturing is predominantly manual and labor-intensive, making it susceptible to human error and contamination73. Another issue is that processes cannot be generalized due to the diversity of cell types, health of donor cells, and DNA73. To improve this, purification of cell material and taking a hybrid approach to automation can reduce contamination, decrease variability and bias, and increase accuracy and precision73.

Ethics

Somatic gene therapy, used in most of the aforementioned studies, seeks to target body cells. However, the use of germline gene therapy, which targets sperm and egg cells, can allow these modifications to pass on to future generations- as seen in the AD mice zygotes study74. Apart from those who have a moral and religious opposition to using embryos for genetic research, its effects on fetal and child development are unknown. As of now, germline genome editing has been discouraged or banned in 40 countries75. Many also have the concern that gene editing for therapeutic usages will eventually be misused for cosmetic and non-medical purposes75. Furthermore, only the wealthy can currently afford gene therapy. Some geneticists argue that embryonic gene therapy’s benefits will never outweigh the risks75. However, germline editing, when done right, can be more effective than current systems (such as preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PDG) and in-vitro fertilization (IVF))75. Most scientists believe that, when able to cure disease, there is a moral imperative to use gene therapy. Germline gene therapy is heavily regulated, and somatic gene therapy is quickly advancing for disease treatment75.

Closing Thought

Gene therapy is a rapidly evolving field. As technological and scientific capabilities increase, so does the possibility of finding a cure or alleviating symptoms of disease. Drawing the scientific community’s attention to the pertinent issue of neurological disease, of which millions are affected, can assist with this progress, one day providing ways for people to live with their neurological condition, or get rid of it entirely.

Methods

Search Strategy

Searches were conducted through a PubMed data search (36 articles) and Google Scholar (1 article) with the keywords “gene therapy” and the disease researched (using the advanced “AND” function). Following initial research, a specific protein/gene and the name of the disease would be used as keywords, such as “Amyloid beta” and “Alzheimer’s,” “Alpha-synuclein” and “Parkinson’s Disease,” “SMN” and “SMA,” and “TDP-43” and “ALS.” Searches also included a combination of gene therapy/specific protein with variants of a specific disease’s name, e.g. PD versus Parkinson’s Disease versus Parkinson’s Disease. This method led to the compilation of at least three articles per genetic target of gene therapy using the search method.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included, a manuscript had to address both gene therapy and its role in neurodegenerative disease. The research had to directly affect a specific DNA, RNA, or protein that ultimately targeted the reduction of pathological symptoms of the four aforementioned diseases. All papers had to be either randomized controlled trials or clinical trials, and all collected articles had to be written after 2010 to ensure more recent data collection. Articles were excluded if they were review papers of gene therapy, if they did not involve some sort of genetic or protein modification, or if they were addressing diseases not involved in this paper. After initial compilation, papers that were targeting a gene/protein that was not targeted by other compiled papers were also excluded due to lack of comparative ability.

Data Extraction

Data included in the review had to contain a p-value of 0.05 or less. Only the main results directly affecting the research question of selected studies were extracted. Only data collected post-2010 was considered.

Synthesis Method

All the papers were grouped based on the specific disease, followed by the protein or gene being modified. For each paper, the results were examined, and pertinent results were extracted. The collected results were organized first by disease and then by the targeted biomarker of disease, with certain papers further organized based on the delivery of the gene therapy.

Quality Assessment

The use of a platform as reputed as PubMed ensured that the articles were peer-reviewed, offering quality. Furthermore, each article chosen was scanned over to ensure neat organization of data, proper corresponding figures, and a clear and thorough abstract, allowing a selection of high-quality papers from a high-quality database.

References

- UT Southwestern Medical Center. Neurodegenerative Disorders. UT Southwestern Medical Center 1–3 Preprint at https://utswmed.org/conditions-treatments/neurodegenerative-disorders/#:~:text=Neurodegenerative disorders encompass a wide,affect millions of people worldwide (2024).

- Alzheimer’s Association. What is Alzheimer’s Disease. 1–3 Preprint at https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers (2024).

- Monfared, A. A. T., Byrnes, M. J., White, L. A. & Zhang, Q. Alzheimer’s Disease: Epidemiology and Clinical Progression. Neurol Ther. 11, 553 (2022).

- Guo, T., Noble, W. & Hanger, D. P. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 133, 665–704. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-017-1707-9 (2017).

- Brothers, H. M., Gosztyla, M. L. & Robinson, S. R. The Physiological Roles of Amyloid-β Peptide Hint at New Ways to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 10, 118 (2018).

- 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 20, 3708–3821. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13809 (2024).

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke. Parkinson’s Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Promise. 1–2 Preprint at https://www.ninds.nih.gov/current-research/focus-disorders/parkinsons-disease-research/parkinsons-disease-challenges-progress-and-promise (2015).

- NIH National Institute of Aging. Parkinson’s Disease: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments. 1–4 Preprint at https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/parkinsons-disease/parkinsons-disease-causes-symptoms-and-treatments (2022).

- Bendor, J. T., Logan, T. P. & Edwards, R. H. The Function of α-Synuclein. Neuron. 79, 1044–1066 (2013).

- Błaszczyk, J. W. Parkinson’s Disease and Neurodegeneration: GABA-Collapse Hypothesis. Front Neurosci. 10, 269 (2016).

- Parkinson’s Foundation. Understanding Parkinson’s: Statistics. 1–2 Preprint at https://www.parkinson.org/understanding-parkinsons/statistics (2024).

- Wright Willis, A., Evanhoff, B. A., Lian, M., Criswell, S. R. & Racette, B. A. Geographic and Ethnic Variation in Parkinson Disease: A Population-Based Study of US Medicare Beneficiaries. Neuroepidemiology. 34, 143-151 (2010).

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke. Spinal Muscular Atrophy. 1–2 Preprint at https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/spinal-muscular-atrophy (2015).

- Chaytow, H., Huang, Y. T., Gillingwater, T. H. & Faller, K. M. E. The role of survival motor neuron protein (SMN) in protein homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 75, 3877 (2018).

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Appendix 7 Clinical Features, Epidemiology, Natural History, and Management of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. 1-2 Preprint at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533981/ (2018).

- Sun, J., Harrington, M. A. & Porter, B. Sex Difference in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Patients – are Males More Vulnerable? J Neuromuscul Dis. 10, 847–867 (2023).

- Hendrickson, B. C. et al. Differences in SMN1 allele frequencies among ethnic groups within North America. J Med Genet. 46, 641–644 (2009).

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). 1–2 Preprint at https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis-als (2024).

- Cohen, T. J., Lee, V. M. Y. & Trojanowski, J. Q. TDP-43 functions and pathogenic mechanisms implicated in TDP-43 proteinopathies. Trends Mol Med. 17, 659 (2011).

- Bunton-Stasyshyn, R. K. A., Saccon, R. A., Fratta, P. & Fisher, E. M. C. SOD1 Function and Its Implications for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathology: New and Renascent Themes. Neuroscientist. 21, 519–529 (2015).

- E.O. Talbott, A.M. Malek & D. Lacomis. Chapter 13 – The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 138, 225-238 (2016).

- ALS Association. Who Gets ALS?. 1–2 Preprint at https://www.als.org/understanding-als/who-gets-als#:~:text=Every%2090%20minutes%2C%20someone%20is,been%20diagnosed%20with%20ALS%20include.

- Qadri, S., Langefeld, C. D., Milligan, C., Caress, J. B. & Cartwright, M. S. Racial differences in intervention rates in individuals with ALS. Neurology. 92, 1969–1974 (2019).

American Society of Gene + Cell Therapy. Gene Therapy Approaches. Preprint at https://patienteducation.asgct.org/gene-therapy-101/gene-therapy-approaches. - Naso, M. F., Tomkowicz, B., Perry, W. L. & Strohl, W. R. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. Biodrugs. 31, 317 (2017).

- Redman, M., King, A., Watson, C. & King, D. What is CRISPR/Cas9? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 101, 213 (2016).

- Griciuc, A. et al. Gene therapy for Alzheimer’s disease targeting CD33 reduces amyloid beta accumulation and neuroinflammation. Hum Mol Genet. 29, 2920 (2020).

- Nagata, K. et al. Generation of App knock-in mice reveals deletion mutations protective against Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology. Nat Commun. 9, (2018).

- György, B. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Disruption of the Swedish APP Allele as a Therapeutic Approach for Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 11, 429 (2018).

- Jonsson, T. et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 488, 96 (2012).

- Huang, W., Li, Z., Zhao, L. & Zhao, W. Simvastatin ameliorate memory deficits and inflammation in clinical and mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via modulating the expression of miR-106b. (2017) doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.060.

- Ferguson, C. M. et al. Silencing Apoe with divalent‐siRNAs improves amyloid burden and activates immune response pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 20, 2632 (2024).

- Gee, M. S. et al. CRISPR base editing-mediated correction of a tau mutation rescues cognitive decline in a mouse model of tauopathy. Transl Neurodegener. 13, (2024).

- Mummery, C. J. et al. Tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide MAPTRx in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a phase 1b, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nat Med. 29, 1437 (2023).

- Edwards, A. L. et al. Exploratory Tau Biomarker Results From a Multiple Ascending-Dose Study of BIIB080 in Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 80, 1344–1352 (2023).

- Migdalska-Richards, A., Daly, L., Bezard, E. & Schapira, A. H. V. Ambroxol effects in glucocerebrosidase and α‐synuclein transgenic mice. Ann Neurol. 80, 766 (2016).

- Mullin, S. et al. Ambroxol for the Treatment of Patients With Parkinson Disease With and Without Glucocerebrosidase Gene Mutations: A Nonrandomized, Noncontrolled Trial. JAMA Neurol. 77, 427 (2020).

- Rocha, E. M. et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene therapy prevents α-synucleinopathy of midbrain dopamine neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 82, 495–503 (2015).

- Sucunza, D. et al. Glucocerebrosidase Gene Therapy Induces Alpha-Synuclein Clearance and Neuroprotection of Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons in Mice and Macaques. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, Vol. 22, Page 4825. 22, 4825 (2021).

- Inoue, S., Nishimura, K., Gima, S., Nakano, M. & Takata, K. CRISPR-Cas9-Edited SNCA Knockout Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons and Their Vulnerability to Neurotoxicity. Biol Pharm Bull. 46, 517–522 (2023).

- Chen, Y. et al. Engineering synucleinopathy‐resistant human dopaminergic neurons by CRISPR‐mediated deletion of the SNCA gene. Eur J Neurosci. 49, 510 (2019).

- LeWitt, P. A. et al. AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 10, 309–319 (2011).

- Vassar, S. D. et al. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Motor Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Parkinsons Dis. 2012, (2012).

- Niethammer, M. et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized AAV2-GAD gene therapy trial for Parkinson’s disease. JCI Insight. 2, (2017).

- Niethammer, M. et al. Gene therapy reduces Parkinson’s disease symptoms by reorganizing functional brain connectivity. Sci Transl Med. 10, (2018).

- Chiriboga, C. A. et al. Results from a phase 1 study of nusinersen (ISIS-SMNRx) in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 86, 890 (2016).

- Finkel, R. S. et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet 388, 3017–3026 (2016).

- Finkel, R. S. et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 377, 1723–1732 (2017).

- Mercuri, E. et al. Risdiplam in types 2 and 3 spinal muscular atrophy: A randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial followed by 24 months of treatment. Eur J Neurol. 30, 1945–1956 (2023).

- Oskoui, M. et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of risdiplam in patients with type 2 or non-ambulant type 3 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). J Neurol. 270, 2531–2546 (2023).

- Masson, R. et al. Safety and efficacy of risdiplam in patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (FIREFISH part 2): secondary analyses from an open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 21, 1110–1119 (2022).

- Kletzl, H. et al. The oral splicing modifier RG7800 increases full length survival of motor neuron 2 mRNA and survival of motor neuron protein: Results from trials in healthy adults and patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 29, 21–29 (2019).

- Marquet, A. et al. Oral SMN2 splicing modifiers in spinal muscular atrophy: Proof-of-mechanism and ongoing clinical studies. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 21, e226 (2017).

- Day, J. W. et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in patients with two copies of SMN2 (STR1VE): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 20, 284–293 (2021).

- Lowes, L. P. et al. Impact of Age and Motor Function in a Phase 1/2A Study of Infants With SMA Type 1 Receiving Single-Dose Gene Replacement Therapy. Pediatr Neurol. 98, 39–45 (2019).

- Strauss, K. A. et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with three copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy: the Phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat Med. 28, 1390–1397 (2022).

- Mendell, J. R. et al. Five-Year Extension Results of the Phase 1 START Trial of Onasemnogene Abeparvovec in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. JAMA Neurol. 78, 834–841 (2021).

- Romano, R. et al. Allele-specific silencing as therapy for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by the p.G376D TARDBP mutation. Brain Commun. 4, (2022).

- Kim, H. C., Zhang, Y., King, P. H. & Lu, L. MicroRNA-183-5p regulates TAR DNA-binding protein 43 neurotoxicity via SQSTM1/p62 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 164, 643–657 (2023).

- Quoibion, A. m 6 A RNA Methylation and TARDBP, a Gene Implicated in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. McGill University (Canada) ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (2017).

- Miller, T. et al. Phase 1-2 Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med. 383, 109–119 (2020).

- Gaj, T. et al. In vivo genome editing improves motor function and extends survival in a mouse model of ALS. Sci Adv. 3, (2017).

- Borel, F. et al. Therapeutic rAAVrh10 Mediated SOD1 Silencing in Adult SOD1(G93A) Mice and Nonhuman Primates. Hum Gene Ther. 27, 19–31 (2016).

- Foust, K. D. et al. Therapeutic AAV9-mediated suppression of mutant SOD1 slows disease progression and extends survival in models of inherited ALS. Mol Ther. 21, 2148–2159 (2013).

- Evernorth Health Services. The Future of Gene Therapy. 1–3 Preprint at https://www.evernorth.com/articles/gene-therapy-changing-landscape#:~:text=Moreover%2C%20we%20may%20see%20genetic,of%20replacing%20the%20entire%20cell (2021).

- Taghdiri, M. & Mussolino, C. Viral and Non-Viral Systems to Deliver Gene Therapeutics to Clinical Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 25, 7333 (2024).

- MedlinePlus. Is Gene Therapy Safe?. 1–2 Preprint at https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/therapy/safety/ (2022).

- Mayo Clinic. Gene Therapy. 1–4 Preprint at https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/gene-therapy/about/pac-20384619#:~:text=Gene%20therapy%20has%20some%20potential,errors%20can%20lead%20to%20cancer (2024).

- MedlinePlus. How Does Gene Therapy Work?. 1–2 Preprint at https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/therapy/procedures/#:~:text=Gene%20therapy%20with%20viral%20vectors,is%20functional%20in%20the%20body (2022).

- McBride, B. Who Do Gene Therapies Cost So Much? 1–3 Preprint at https://www.fiosgenomics.com/why-do-gene-therapies-cost-so-much/ (2023).

- Springer Nature. The Gene Therapy Revolution Risks Stalling If We Don’t Talk About Drug Pricing. Nature. 616, 629-630 (2023).

- Su, W. Pioneering Scalable Solutions in AAV Manufacturing and Testing for Gene Therapy. 1–2 Preprint at https://advancedtherapies.com/pioneering-scalable-solutions-in-aav-manufacturing-and-testing-for-gene-therapy/#:~:text=The%20Scalability%20Challenge%20in%20AAV%20Manufacturing&text=These%20challenges%20stem%20from%20the,a%20WuXi%20Advanced%20Therapies%20company (2024).

- Atlantis Bioscience. Navigating the Path to Scalable Cell and Gene Therapy Production: Embracing Process Optimising & Automation. 1–8 Preprint at https://www.atlantisbioscience.com/blog/navigating-the-path-to-scalable-cell-and-gene-therapy-production-embracing-process-optimising-automation/#:~:text=A%20key%20challenge%20in%20developing,financial%20losses%20and%20product%20failure (2024).

- MedlinePlus. What Are The Ethical Issues Surrounding Gene Therapy? 1–2 Preprint at https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/therapy/ethics/ (2022).

- National Human Genome Research Institute. What are the Ethical Concerns of Genome Editing?. 1–3 Preprint at https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/policy-issues/Genome-Editing/ethical-concerns (2017).

- E.O. Talbott, A.M. Malek & D. Lacomis. Chapter 13 – The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 138, 225-238 (2016) [↩]