Abstract

With the first image of the supermassive black hole in the middle of our galaxy being released three years ago, this paper presents an in-depth analysis of photon trajectories around black holes under the influence of general relativity. We use computer simulations to model the intricate patterns these trajectories form, including spirals, loops, and orbits, as photons traverse the curved spacetime near these dense objects. By deriving and solving the geodesic equations for photons in the Schwarzschild metric, we illustrate the dependence of photon paths on the black hole’s mass parameter. Numerical simulations are used to visualize various photon trajectory configurations, shedding light on phenomena such as the photon sphere and gravitational lensing. These findings contribute to our understanding of light behavior in extreme gravitational fields and have implications for observational astrophysics, particularly in interpreting images of black holes and their surroundings. These trajectories are utilized by many telescopes, for example, the Event Horizon Telescope to get a visual representation of what the black hole should look like.

Introduction

The study of photon trajectories around black holes is a fundamental aspect of general relativity and astrophysics. Black holes, predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, are regions of spacetime where the gravitational pull is so strong that even light cannot escape. The paths that photons follow near a black hole reveal much about the nature of gravity and spacetime curvature.

Black holes are characterized primarily by their mass, spin, and electric charge. The most studied solutions to Einstein’s field equations are the Schwarzschild metric, which describes a non-rotating, uncharged black hole. In this metric, the geodesic equations govern the motion of particles and photons, and solving these equations provides insights into the path’s photons take as they move through curved spacetime.

Black holes are characterized primarily by their mass, spin, and electric charge. The most studied solutions to Einstein’s field equations are the Schwarzschild metric, which describes a non-rotating, uncharged black hole. In this metric, the geodesic equations govern the motion of particles and photons, and solving these equations provides insights into the path’s photons take as they move through curved spacetime.

One of the intriguing features of black holes is the photon sphere, a spherical region where gravity is strong enough that photons can orbit the uncharged black hole. For a Schwarzschild black hole, this occurs at a radius of ![]() where

where ![]() is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant, ![]() is the mass of the black hole, and

is the mass of the black hole, and ![]() is the speed of light. This radius lies just outside the Schwarzschild radius

is the speed of light. This radius lies just outside the Schwarzschild radius ![]() which defines the event horizon—the boundary beyond which not even light can escape. The region between the photon sphere and the event horizon is particularly extreme, where spacetime curvature becomes so intense that it dramatically alters the paths of photons. Gravitational lensing, another consequence of curved spacetime, occurs when light from a distant source is bent around a massive object, such as a black hole. This phenomenon has been observed and used to infer the presence and properties of black holes and other massive objects in the universe.

which defines the event horizon—the boundary beyond which not even light can escape. The region between the photon sphere and the event horizon is particularly extreme, where spacetime curvature becomes so intense that it dramatically alters the paths of photons. Gravitational lensing, another consequence of curved spacetime, occurs when light from a distant source is bent around a massive object, such as a black hole. This phenomenon has been observed and used to infer the presence and properties of black holes and other massive objects in the universe.

The intense gravitational field of a black hole warps spacetime around it. As a result, understanding the image of a black hole requires an understanding of how photons move on relativistic trajectories. Several works have made progress in modeling these trajectories1. The culmination of this work resulted in the first ever image of a black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope2

Previous studies on photon trajectories in Schwarzschild and Kerr spacetimes have extensively covered the photon sphere and gravitational lensing. For instance, the work by Beckwith and Done in 2005, explores photon trajectories and gravitational lensing effects in the strong gravitational field of Kerr black holes . However, this study addresses a gap in the systematic parameterization of initial photon conditions leading to distinct trajectory types, such as unstable orbits and parabolic escapes, and extends the analysis to consider observational implications for modern telescopes.

In this paper, we derive the equations governing photon trajectories around black holes and explore various configurations of these paths through numerical simulations. The numerical simulations were performed using Python, leveraging libraries such as NumPy and Matplotlib for integration and visualization. The complete code has been appended in the supplementary materials section. Our work complements existing codes already in the literature3. By varying the parameters such as the black hole’s mass, we aim to visualize and understand the several types of photon trajectories that can occur, including circular orbits, plunging trajectories, and escape trajectories. These results not only deepen our understanding of black hole physics but also aid in interpreting observational data from telescopes and space missions.

Methodology

Schwarzschild Metric

The Schwarzschild metric is the solution to Einstein’s field equations that describes the spacetime surrounding a non-rotating, uncharged black hole. This study assumes a Schwarzschild black hole, as a simplification to focus on photon trajectories in a spherically symmetric spacetime. While rotating and charged black holes introduce additional complexities, they are beyond the scope of this analysis. We refer the reader to other work for a discussion of such black holes.4

In Schwarzschild coordinates (t,r,θ,ϕ), the metric is given by:

(1) ![]()

Where:![]() is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant,![]() is the mass of the black hole,

is the mass of the black hole,![]() is the speed of light,

is the speed of light,![]() is the radial coordinate,

is the radial coordinate,![]() and

and ![]() are the angular coordinates.

are the angular coordinates.

The Schwarzschild radius ![]() marks the event horizon of the black hole.

marks the event horizon of the black hole.

Geodesic Equations for Photons:

The motion of photons in the Schwarzschild metric is represented in null geodesics, which are the geodesics for a massless particle.5. Null geodesics are the paths followed by massless particles like photons. All motion of photons is governed by geodesic equations. In relativity, photons are described as massless; this is strongly supported by many experiments that constrain any photon mass to be extremely small. Null geodesics satisfy ![]() , in contrast to timelike geodesics of massive particles, which satisfy

, in contrast to timelike geodesics of massive particles, which satisfy ![]() .

.

For a photon moving in the equatorial plane, ![]() , the Schwarzschild metric reduces to:

, the Schwarzschild metric reduces to:

(2) ![]()

where ![]() are derivatives with respect to an affine parameter

are derivatives with respect to an affine parameter ![]() (the shortest path between two points in curved spacetime where the parameter itself is directly related to the curvature of spacetime). This metric describes the curvature of spacetime around a non-rotating black hole. The equation

(the shortest path between two points in curved spacetime where the parameter itself is directly related to the curvature of spacetime). This metric describes the curvature of spacetime around a non-rotating black hole. The equation ![]() is used because photons follow null geodesics.

is used because photons follow null geodesics.

Step 1: Lagrangian for the Photon

The motion of a photon is governed by the geodesic equation, which can be derived from the Lagrangian corresponding to the Schwarzschild metric. The Lagrangian method is well-established in general relativity for deriving equations of motion, including for general relativity6.

The Lagrangian ![]() is:

is:

(3) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} \Bigg[\left( 1 - \frac{2GM}{r c^2} \right) c^2 \, (t'^2)\left( 1 - \frac{2GM}{r c^2} \right)^{-1} (r'^2)+r^2 \, (\phi'^2)\Bigg]\end{equation*}](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-134b9188b57c494ffa54013280ae951d_l3.png)

Step 2: Setting the conditions

For null geodesics, the Lagrangian evaluates to zero along the trajectory (![]() ), reflecting

), reflecting ![]() ; we still derive the equations of motion via the Euler–Lagrange equations as usual. This null condition provides a systematic way to solve for the geodesic equations7.

; we still derive the equations of motion via the Euler–Lagrange equations as usual. This null condition provides a systematic way to solve for the geodesic equations7.

The Lagrangian consists of contributions from the time, radial, and angular coordinates. Since we are deriving the equation of motion for the radial coordinate, it is advantageous to exploit the symmetries of the spacetime by identifying conserved quantities. Specifically, the time and angular coordinates are cyclic, and their corresponding conjugate momenta are conserved by Noether’s Theorem. These conserved quantities simplify the radial equation. In this study, we adopt natural units where the speed of light c=1. This assumption simplifies the mathematical framework without affecting the generality of the results. All quantities can be converted back to physical units by reintroducing c where necessary to balance the units.

- t is cyclic:

(4) ![]()

is cyclic:

is cyclic:

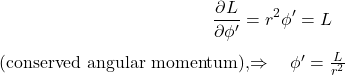

(5)

For null geodesics, only the ratio b = L/E, known as the impact parameter, has direct physical significance, for the photon trajectory.

Step 3: Substituting and Simplifying

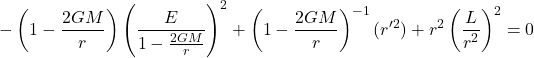

We begin by using the null condition:

(6) ![]()

Substituting in ![]() and

and ![]()

(7)

Multiply through by ![]()

(8) ![]()

After rearranging we get our final Radial Geodesic Equation:

(9) ![]()

Step 4: Angular Equation for

We already know the angular equation from earlier:

(10) ![]()

These equations describe the radial and angular motion of photons in the curved spacetime around a black hole. The angular part of the Euler-Lagrange equation encapsulates the conservation of angular momentum, a result of the spherical symmetry of the Schwarzschild spacetime. This conserved quantity simplifies the analysis of photon trajectories by reducing the number of independent variables, as the motion in the angular plane remains constant under this symmetry.

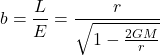

Photon sphere and Critical Impact Parameter

Photons with specific impact parameters can orbit the black hole at this radius indefinitely. The impact parameter b , the perpendicular distance between the path of a moving object (like a star or planet) and the center of another object (like a black hole) that it is passing by is given by:

(11)

Where

Numerical Simulations

Simulation setup

To simulate photon trajectories, the geodesic equations are numerically integrated using a second-order central finite-difference method. Parameters such as the black hole mass and the photons’ initial conditions are varied to explore different classes of trajectories.

Equations of Motion in different coordinates

To analyze photon trajectories around a Schwarzschild black hole, it is advantageous to express the geodesic equations in terms of the inverse radial coordinate:

(12) ![]()

This substitution simplifies the mathematical formulation of the problem and allows us to derive a second-order differential equation solely in terms of the angular variable

Starting from equation 9, the radial geodesic equation (derived earlier) We wish to eliminate the affine parameter ![]() and rewrite the equation in terms of

and rewrite the equation in terms of ![]() . Since angular momentum is conserved, we know:

. Since angular momentum is conserved, we know:

(13) ![]()

Using this equation, the radial geodesic equation transforms into:

(14) ![]()

Differentiation yields the orbital equation:

(15) ![]()

Where the

To calculate a photon trajectory, we need:

The mass ![]() initial polar coordinates

initial polar coordinates ![]() . Initial direction of photon motion determined by the angle

. Initial direction of photon motion determined by the angle ![]() . Here,

. Here, ![]() is defined as the angle between the radial vector and the initial photon velocity vector in the

is defined as the angle between the radial vector and the initial photon velocity vector in the ![]() plane. This determines the initial direction of motion with respect to the black hole’s center.

plane. This determines the initial direction of motion with respect to the black hole’s center.

The photon trajectory can be computed iteratively using:

Choose the mass ![]() , initial parameters

, initial parameters ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the step change

, and the step change ![]() .

.

Set ![]() =0

=0

Compute initial conditions:

(16) ![]()

(17) ![]()

Compute subsequent values iteratively:

(18) ![]()

Applying the previous u.

In the numerical simulation of photon trajectories, after applying a second-order central finite-difference discretization to the geodesic equation, the update rule can be expressed as:

(19) ![]()

Using the earlier derived equation for ![]() we substitute into the iterative equation:

we substitute into the iterative equation:

(20) ![]()

This iterative formula is used to compute the photon’s trajectory numerically, where at each step, the next value of u (and hence r) is calculated based on the previous values and the curvature effects encoded by the Schwarzschild metric. The explicit second-order finite-difference scheme is conditionally stable. Numerical convergence was verified by systematically reducing the step size

Initial Conditions

For the simulations, we consider the following parameters; however, note that these values can be altered to manipulate the outcome of the program:

![]()

Initial radial position: ![]()

Initial angular position: ![]()

Initial direction of motion: ![]()

Step change of ![]() :

: ![]() radians per iteration

radians per iteration

Black hole mass: ![]() corresponds to a typical stellar-mass black hole, commonly observed in X-ray binaries. This choice ensures that the results are relevant astrophysically. Since the Schwarzschild radius scales linearly with mass, the results can be generalized to other masses by appropriate scaling of the coordinates.

corresponds to a typical stellar-mass black hole, commonly observed in X-ray binaries. This choice ensures that the results are relevant astrophysically. Since the Schwarzschild radius scales linearly with mass, the results can be generalized to other masses by appropriate scaling of the coordinates.

Numerical Simulation of Photon Trajectories

All code is addressed at the following repository: https://zenodo.org/uploads/13623824

Numerical methods are employed to solve the geodesic equations for photon trajectories around black holes. The equations are integrated using a second-order finite-difference scheme. Initial conditions for the photon’s position and momentum are specified, and the photon’s trajectory is obtained by iterating the discretized equations through curved spacetime.

In simulations, various phenomena such as gravitational lensing, photon capture by the black holes, and deflection angles can be observed. These results offer valuable insights into the observational signatures of black holes, aiding in the interpretation of astrophysical data.

One important aspect to pay attention to is the effective potential, which combines gravitational and centrifugal force potential to see how far a photon will travel in respect to the photon sphere, which corresponds to the radius of an unstable circular photon orbit. It is not a true boundary or point of no return. Photons that pass inside the photon sphere may either escape to infinity or fall into the black hole depending on their impact parameter and direction of motion. Only the event horizon represents a true one-way boundary for light. There is no physical reflection; photons follow curved null geodesics. The effective potential for a photon is:

(21) ![]()

Here,

Results:

The effective potential immediately reveals the three qualitatively distinct classes of photon trajectories in Schwarzschild spacetime. In the effective potential picture for null geodesics in Schwarzschild spacetime, there are three possible types of photon trajectories: (i) escape orbits that are deflected and return to infinity, (ii) an unstable circular orbit at the photon sphere radius ![]() , and (iii) plunging orbits that cross the photon sphere from the outside and spiral into the black hole. Thus, for photons falling in from large radius, crossing the photon sphere from the outside is equivalent to eventual capture, while trajectories that escape never penetrate inside this radius. After applying the metrics, and the equations for a photon, each with slightly different initial conditions we see several different kinds of trajectories each differing depending on the photon’s location with respect to the photon sphere.

, and (iii) plunging orbits that cross the photon sphere from the outside and spiral into the black hole. Thus, for photons falling in from large radius, crossing the photon sphere from the outside is equivalent to eventual capture, while trajectories that escape never penetrate inside this radius. After applying the metrics, and the equations for a photon, each with slightly different initial conditions we see several different kinds of trajectories each differing depending on the photon’s location with respect to the photon sphere.

In this study we consider photons that start outside the black hole and fall inward under gravity. For such free-fall trajectories, any photon that crosses the photon sphere from the outside subsequently crosses the event horizon and is captured. In general, however, the photon sphere itself is not a true point of no return; only the event horizon represents an absolute causal boundary.

For example, if a photon approaches the photon sphere with the initial conditions:

Initial radial position: ![]()

Initial angular position: ![]()

Initial direction: ![]() , (measured from the radial direction, almost radially inward)

, (measured from the radial direction, almost radially inward)

its trajectory spirals:

In this particular trajectory, the photon passes inside the photon sphere and subsequently crosses the event horizon, after which infall is inevitable. It is essential to evaluate the photon’s energy and the role of the effective potential. The photon’s energy determines whether it can escape the gravitational well of the black hole or whether it will spiral inward towards the singularity. As the photon approaches the photon sphere, the effective potential becomes critical in defining the photon’s trajectory. A photon’s motion near the photon sphere is dictated by the balance in effective potential energy. Whether a photon is captured by the black hole or escapes to infinity is determined by its impact parameter ![]() , rather than its energy alone. If the impact parameter is smaller than the critical value corresponding to the photon sphere, the photon crosses the event horizon and falls into the black hole. The photon crosses the photon sphere and, in this specific case, continues inward until it crosses the event horizon, after which it inevitably falls into the black hole. The photon, unable to overcome the gravitational pull, follows the curvature dictated by the effective potential. The photon must cross the event horizon to reach the singularity. For free-fall trajectories starting outside the black hole, this necessarily occurs after crossing the photon sphere. Through this we see that the photon sphere corresponds to the maximum of the effective potential for null geodesics, which defines a critical impact parameter separating plunging and escaping trajectories. However, to calculate that, we first need to calculate where the photon sphere is located. According to the diagram, at the photon sphere, the photon should have an unstable circular orbit as it is not far enough to be deflected back nor is it close enough to collapse. This point is referred to as the photon sphere.

, rather than its energy alone. If the impact parameter is smaller than the critical value corresponding to the photon sphere, the photon crosses the event horizon and falls into the black hole. The photon crosses the photon sphere and, in this specific case, continues inward until it crosses the event horizon, after which it inevitably falls into the black hole. The photon, unable to overcome the gravitational pull, follows the curvature dictated by the effective potential. The photon must cross the event horizon to reach the singularity. For free-fall trajectories starting outside the black hole, this necessarily occurs after crossing the photon sphere. Through this we see that the photon sphere corresponds to the maximum of the effective potential for null geodesics, which defines a critical impact parameter separating plunging and escaping trajectories. However, to calculate that, we first need to calculate where the photon sphere is located. According to the diagram, at the photon sphere, the photon should have an unstable circular orbit as it is not far enough to be deflected back nor is it close enough to collapse. This point is referred to as the photon sphere.

To find the photon sphere we start from the effective potential for a photon in the Schwarzschild spacetime. The maximum of the potential can be found by taking the derivative of the potential (with respect to r) and setting it equal to zero:

![]()

By doing this, we get an equation through which we can solve for the radius r:

![]()

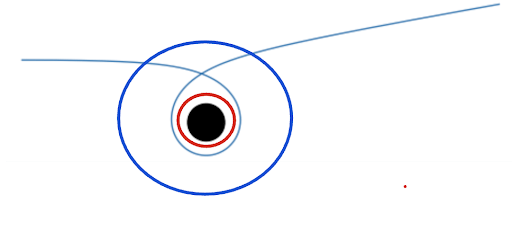

Therefore, if the photon has the critical impact parameter corresponding to the maximum of the effective potential, the trajectory becomes an unstable circular orbit at ![]() .8. Giving the photon a purely tangential motion with an initial angular position of 0 and placing it at

.8. Giving the photon a purely tangential motion with an initial angular position of 0 and placing it at ![]() :

:

As observed, if we take ![]() of

of ![]() we can make an unstable circular trajectory; The instability of the photon orbit is rooted in the nature of the photon sphere, which is situated at the peak of the effective potential for a photon orbiting a black hole9. Such maxima in the effective potential are indicative of unstable orbits, which means that every orbit at the photon sphere is inherently unstable, so with the smallest nudge or non-circularity, it can go into or away from the black hole. This photon sphere uniquely represents the only circular orbit available to light, implying that light can only sustain an unstable circular trajectory. In contrast, massive particles can have both stable and unstable circular orbits. Specifically, orbits located at a maximum in the effective potential are always unstable. This instability arises because any minor perturbation at such a maximum will drive the particle away from the equilibrium position, causing it to descend to a lower potential level. Thus, the orbit is deemed unstable, as the particle will not return to its initial orbit but rather drift to a different, lower-energy state.

we can make an unstable circular trajectory; The instability of the photon orbit is rooted in the nature of the photon sphere, which is situated at the peak of the effective potential for a photon orbiting a black hole9. Such maxima in the effective potential are indicative of unstable orbits, which means that every orbit at the photon sphere is inherently unstable, so with the smallest nudge or non-circularity, it can go into or away from the black hole. This photon sphere uniquely represents the only circular orbit available to light, implying that light can only sustain an unstable circular trajectory. In contrast, massive particles can have both stable and unstable circular orbits. Specifically, orbits located at a maximum in the effective potential are always unstable. This instability arises because any minor perturbation at such a maximum will drive the particle away from the equilibrium position, causing it to descend to a lower potential level. Thus, the orbit is deemed unstable, as the particle will not return to its initial orbit but rather drift to a different, lower-energy state.

Mathematically, the stability of orbits is assessed by examining the second derivative of the effective potential. Specifically, if the second derivative is negative, the orbit is unstable, whereas a positive second derivative indicates a stable orbit.

This analysis relies on the concept of concavity. A negative second derivative signifies that the graph of the function is concave downward. Therefore, at an extremum, such as a circular orbit in this context, a negative second derivative denotes that the point is a maximum, which corresponds to an unstable orbit. Conversely, a positive second derivative indicates that the point is a minimum because it signifies the concavity is upwards, suggesting a stable orbit.

So, the condition for an unstable orbit is therefore:

![]()

Now to find the necessary effective potential

![]()

The Schwarzschild radius, as a distinct radial distance, allows for its direct substitution into equations involving radial coordinates. For example, in the following expression:

![]()

![]()

![]()

So, the effective potential required for a photon to reach the photon sphere is given by ![]() .

.

However, not all photons possess enough energy or effective potential to reach this region.

Photons with impact parameters larger than the critical value do not reach the photon sphere and instead follow escape trajectories that appear approximately parabolic at large distances. such as:

In Figure 3 the photon gets increasingly close to the event horizon, but doesn’t pass it so as a result it forms an almost parabolic orbit where it comes from a certain point and gets deflected out due to the extreme gravitational force the black hole exerts, which curves spacetime so significantly that even light, traveling in a straight line in flat spacetime, is bent when passing close to the black hole’s event horizon, causing light to follow a curved path, otherwise known as Gravitational Lensing10.This is the phenomenon where light curves as it passes near a massive object—whether it be a black hole or another massive body—serves as an observational test for general relativity4 By determining the angle of this deflection and contrasting it with the theoretical prediction given by general relativity,![]() , where b is the photon’s impact parameter; one can validate the theory’s accuracy. In terms of Effective Potential and energy, the photon lacks the necessary amount, so it never reaches the photon sphere. The initial conditions for this were:

, where b is the photon’s impact parameter; one can validate the theory’s accuracy. In terms of Effective Potential and energy, the photon lacks the necessary amount, so it never reaches the photon sphere. The initial conditions for this were:

Initial radial position: ![]()

Initial angular position: ![]()

Initial direction: ![]() (toward the central relative to radial vector)

(toward the central relative to radial vector)

However, in a certain case, it is possible for the photon’s path to seem like an orbit, but still get deflected out:

Figure 4’s orbit is something that should not be possible by a Keplerian orbit since generally Keplerian orbits do not double cross the same point, but rather trace ellipses.

However, our loop orbit occurs because of how close the photon gets to the photon sphere. The photon in Figure 4 is not in a closed orbit but is remarkably close to the photon sphere. Its path is strongly curved as it approaches the black hole, and it loops around it due to the intense gravitational field and due to its proximity to the photon sphere, it almost makes a circular trajectory. After looping, the photon eventually escapes because its trajectory does not perfectly match the conditions needed for an unstable circular orbit. The photon in our image is not in a closed orbit but is close to the photon sphere. Its path is strongly curved as it approaches the black hole, and it loops around it due to the intense gravitational field. After looping, the photon eventually escapes because its trajectory does not perfectly match the conditions needed for a circular orbit, but behaves the same way for a few iterations because of the similarity. The intitial conditions for this trajectory are:

Initial radial position: ![]()

Initial angular position: ![]()

Initial direction: ![]() (near-tangential motion, but slightly inward)

(near-tangential motion, but slightly inward)

Figures 1 through 4 illustrate photon trajectories for varying initial conditions and effective potential configurations. Quantitative metrics, such as deflection angles and energy thresholds for escape trajectories, are provided to enhance the analysis. Although the governing equations are exact, the numerical solution introduces second-order truncation error due to finite step size ![]() . No error bars are shown, as the results are qualitatively robust for sufficiently small step sizes.

. No error bars are shown, as the results are qualitatively robust for sufficiently small step sizes.

Discussion:

This research paper has provided a comprehensive analysis of photon trajectories in the vicinity of black holes, elucidating several critical aspects of black hole physics. The study highlighted how photons, when subjected to the intense gravitational field of a black hole, exhibit unique trajectories that deviate significantly from straight-line paths, a consequence of the warping of spacetime predicted by General Relativity. This deviation leads to phenomena such as gravitational lensing, where light from distant sources is bent, creating observable effects like Einstein’s rings. One of the key findings was the existence of the photon sphere—a region where photons can orbit the black hole due to the extreme curvature of spacetime. This region, located at 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius, represents a delicate balance between gravitational pull and the photon’s velocity, illustrating the profound effects of gravity near a black hole. The photon sphere’s location and its properties are consistent with predictions from general relativity11‘12. Gravitational lensing phenomena observed in these simulations align with observational data12‘2. Moreover, the study delved into the mathematical modeling of photon trajectories, emphasizing the role of the Schwarzschild metric in describing the geometry of spacetime around a non-rotating black hole since by deriving it, all the equations of motion can be found. The analysis also discussed the conditions under which photons either escape to infinity, spiral into the event horizon, or are trapped in an unstable orbit, depending on their initial conditions and proximity to the black hole; in addition, we found the necessary effective potential for a photon to enter a circular orbit to be ![]() . Through this report, we can understand the basics of light in extreme gravitational fields which further allow us to understand how the Event Horizon Telescope functions. In conclusion, this paper reinforces the understanding of black holes as key testing grounds for General Relativity, offering deep insights into the behavior of light in extreme gravitational fields and providing a foundation for future research in astrophysical phenomena.

. Through this report, we can understand the basics of light in extreme gravitational fields which further allow us to understand how the Event Horizon Telescope functions. In conclusion, this paper reinforces the understanding of black holes as key testing grounds for General Relativity, offering deep insights into the behavior of light in extreme gravitational fields and providing a foundation for future research in astrophysical phenomena.

Acknowledgments:

I’d like to thank Professor Alexander Mushtukov for exposing me to the fascinating world of Astrophysics.

References

- Cruz, N., Olivares, M., & Villanueva, J. R. (2005). The geodesic structure of the Schwarzschild anti-de Sitter black hole. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 22(6), 1167–1190. https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/22/6/016 [↩]

- Gerald Bower. Astronomers Reveal First Image of the Black Hole at the Heart of Our Galaxy. Event Horizon Telescope, (2022). [↩] [↩]

- Dexter, J., & Agol, E. (2009). A fast new public code for computing photon orbits in a Kerr spacetime. The Astrophysical Journal, 696(2), 1616–1629. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/696/2/1616 [↩]

- Beckwith, K., & Done, C. (2005). Extreme gravitational lensing near rotating black holes. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 359(4), 1217–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08980.. Extreme gravitational lensing near rotating black holes. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, [↩] [↩]

- Null geodesics in the Kerr–Newman metric. Jiří Podolský & Martin Švarc, Physical Review D, vol. 92, no. 4, 2015, 044042. [↩]

- The Lagrangian method. David Morin, Scholars at Harvard, 2007. http://www.people.fas .harvard.edu/~djmorin /chap 6.pdf [↩]

- The Lagrangian method. David Morin, Scholars at Harvard, 2007. http://www.people.fas .harvard.edu/~djmorin /chap 6.pdf [↩]

- Can light orbit a black hole? The physics explained. Ville Hirvonen,496

Profound Physics.497 [↩] - Circular photon orbits in Reissner–Nordström spacetimes. Volker Perlick, Il Nuovo Cimento B, vol. 119, no. 5, 2004, pp. 489–500https://doi.org/10.1393/ncb/i2004-10136-5 [↩]

- Photon orbits in accelerated black hole spacetimes. J. B. Griffiths & J. Podolský, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 359, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1217–1228. [↩]

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). On the gravitational field of a mass point according to Einstein’s theory. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 189–196. [↩]

- The collected papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 6: The Berlin years (En-506glish translation supplement. Albert Einstein, Princeton University Press.507). [↩] [↩]