Abstract

Youth homelessness in San Jose, California, is a widespread but largely hidden crisis that undermines educational, social, and health outcomes. This study addresses the problem of limited early identification and fragmented institutional response by examining how school-based systems can mitigate student housing instability. Guided by an ecological systems and social capital framework, the research investigates how educational institutions operate as protective environments within broader structural inequities. Using a mixed-methods approach case study of the East Side Union High School District (ESUHSD) – a large urban district serving over 23,000 students – the study integrates quantitative district census and point-in-time data on McKinney-Vento student identification with qualitative interviews involving six Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS), nonprofit partners, and students. Through this method, we identify four core drivers: family instability, unaffordable housing, educational disengagement, and systemic barriers affecting marginalized groups. Findings iterate that schools with two or more PCIS staff identify relatively more unhoused students in the academic year, a pattern associated with stronger wraparound support and sustained engagement. Yet even high-capacity schools face structural limits tied to volatile funding, restrictive eligibility criteria, and a regional housing market in crisis. The results frame schools as critical but constrained frontline responders, emphasizing the need for youth-targeted housing policy, stable funding, centralized resources, and cross-sector collaboration to prevent long-term cycles of poverty and displacement. The study concludes with policy recommendations to expand school-based capacity and align education, housing, and social services to ensure stability and opportunity for vulnerable youth.

Keywords: Social and Behavioral Science; Education Policy; Housing Policy; Economic Policy; Youth Homelessness; Housing Instability; School-Based Interventions; High Schools; San Jose.

Introduction

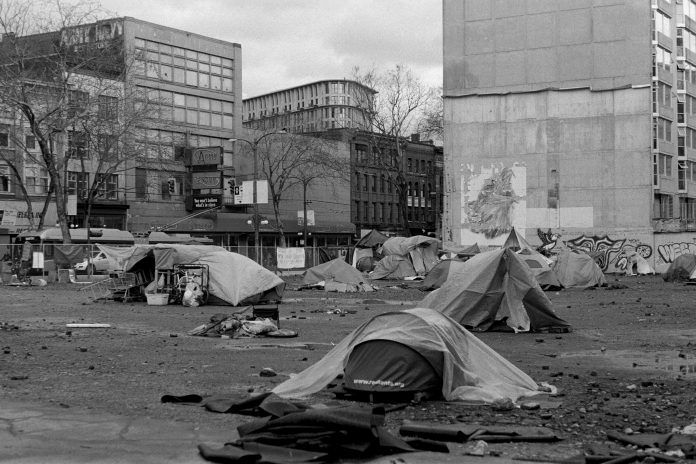

Youth homelessness in the United States is often hidden in plain sight. The Department of Education reported nearly 1.4 million K-12 public school students experiencing homelessness in the 2022-23 school year1, a figure that excludes many who do not self-identify or meet narrower definitions used by regional housing authorities. Unlike adult homelessness, which is more visible in public spaces, youth homelessness tends to be concealed in “doubled-up” arrangements, “couch surfing,” or temporary stays with non-guardian relatives. This invisibility has historically made prevention and early identification more difficult. Public schools play a critical role in addressing this crisis. They provide daily shelter, at least two meals for every student, and free mental and physical health support. Schools also serve as incubators for the prevention of drug and substance abuse, which unhoused youth are particularly susceptible to. Therefore, when understanding youth homelessness, it is critical to study the role of schools in providing the foundation upon which unhoused students receive equitable resources and are ensured access to higher education.

The federal 1987 McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act requires public schools to identify and support students “lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence,” and mandates the appointment of a local liaison to ensure access to education without barriers such as lack of documentation or transportation2. Over the last three decades, however, implementation of McKinney-Vento has varied widely between districts, largely depending on local leadership, funding constraints, and availability of community partnerships. Prevention programs face recurring structural challenges, such as staffing reductions during budget shortfalls, siloed service systems bridging education, housing, and social services, and limited youth-specific housing resources within municipal homelessness programs. Even with strong foundations, structural limitations persist; the 2024 McKinney-Vento funding of $129 million2 amounted to barely $92 per student, with significant disparities in fund distribution across states and districts. Moreover, student mobility, variable self-identification, stigma, and fragmented service systems often hinder effective identification and delivery of services3.

While prior research has documented the prevalence and effects of youth homelessness, relatively few studies have examined how school-based systems, staffing structures, and community partnerships affect early identification and intervention, particularly within high-cost urban regions such as San Jose, California. Existing research rarely quantifies the relationship between staffing capacity and student identification outcomes, leaving a critical gap in understanding how schools can function effectively as frontline responders to youth housing instability.

East Side Union High School District in San Jose, California, provides a case-in-point for these challenges and opportunities. Serving a student population of over 23,000 across 11 high schools4, ESUHSD operates within one of the most expensive housing markets in the nation, juxtaposed with the highest rate of youth homelessness in the country5‘6. The district’s internal surveys identified over 1,000 students meeting McKinney-Vento criteria in the 2023-2024 academic year, a rate that far exceeds national averages and indicates significant undercounting in regional homelessness data.

ESUHSD has implemented the McKinney-Vento mandate through its Parent and Community Involvement Specialist (PCIS) program, placing at least two full-time specialists at each school. These specialists handle student identification, needs assessments, family outreach, and coordination with local nonprofits. Funding shifts in recent years, however, have reduced this into a single specialist at many sites, with many support workers taking on extraneous roles to make up for budgetary limitations.

This study seeks to address the research gap through a mixed-methods case study of ESUHSD, framed by an ecological systems and social capital framework examining the impact of social environments on childhood growth in the context of housing instability. The study identifies the primary determinants of youth homelessness in San Jose and evaluates existing systems in place to address the issue. It further studies the relationship between the capacity of school-based support staff and early identification and intervention for students experiencing housing instability in ESUHSD. Using qualitative and statistical analysis, the study correlates the primary determinants to broader systemic trends in Santa Clara County and offers policy recommendations to strengthen school support programs. It balances quantitative indicators with qualitative narratives from staff, nonprofit partners, and students to offer a grounded view of the crisis.

Literature Review

Research on youth homelessness has expanded over the past two decades, yet remains fragmented across disciplines. Sociologists emphasize structural inequities such as poverty, housing costs, and family breakdown, while education scholars focus on school-based responses. This study draws on an ecological framework7 to position schools as micro-level institutions operating within larger economic and policy systems, and on a social capital perspective8 to understand how trust and relationships between students, staff, and community organizations enable resource access.

Studies constantly highlight the hidden and systemic nature of youth homelessness. Large scale reports9‘10establish correlations between unstable housing, academic disengagement, and later economic hardship. The general consensus among scholars is that housing instability is closely correlated with economic difficulty in the future, but most studies emphasize the long-term effects rather than systemic causal factors. These studies are primarily descriptive, offering limited insight into the mechanisms through which schools can actively disrupt that trajectory.

Regional studies in California and Oregon11‘12 move closer to this question by linking early identification to higher attendance and graduation rates. Yet they stop short of analyzing how institutional capacity – staffing levels, role clarity, and cross-agency collaboration – enables such early identification. Thus, while the impact of instability is documented, the conditions under which schools can effectively intervene remain unclear.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act provides a legal framework mandating education access for unhoused youth2. Implementation research finds that compliance varies widely across districts, based on funding stability, staff capacity, and local partnerships13. Scholars argue that McKinney-Vento’s effectiveness hinges on discretionary practices of individual liaisons rather than consistent institutional structures3.

A recurring theme in the literature is the importance of human infrastructure. Studies highlight how dedicated homelessness liaisons or community specialists improve referral follow-through14, but few quantify the relationship between staffing ratios and student outcomes. Moreover, most research predates the post-pandemic surge in housing costs, leaving open questions about how contemporary economic pressure strains district capacities.

Urban policy literature emphasizes that educational interventions cannot succeed without complementary housing strategies. City-level evaluations15 show that most homelessness funding targets adults, with minimal youth-specific programming. Project HomeKey16, a statewide program to convert motels into interim housing, and similar initiatives, while effective for families, often exclude unaccompanied minors due to eligibility criteria.

Only a small body of literature attempts to bridge education and housing policy. These studies advocate for interagency data sharing and dedicated youth housing funds17, but empirical evaluations of such models remain rare. This absence limits understanding of how cross-sector alignment could improve both educational and housing outcomes.

Taken together, the literature establishes that schools play vital role in mitigating youth homelessness. What remains underexplored is the organizational dimension: comparative analyses of how differences in school resources, staffing, and community linkages shape the ability to detect and support unhoused students.

This study contributes by examining these organizational mechanisms within the East Side Union High School District, integrating district census data on McKinney-Vento identification with qualitative narratives from involved parties (Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS), nonprofit partners, and students). In doing so, it responds to calls for research connecting micro-level school practices to macro-level structural constraints, offering empirical evidence for how educational institutions can more effectively prevent and respond to youth homelessness.

Primary Determinants of Youth Homelessness in the ESUHSD Case

Broader systemic inequities largely make up the primary determinants of youth homelessness in San Jose. While adult homelessness can be classified into systemic and personal causes (such as gambling or addiction,) youth are less susceptible to personal causes of homelessness and are instead usually a product of systemic issues – economic, familial, educational, and institutional. It is both a crisis of shelter and a crisis of access to support systems, to dignity, and to safety.

The Santa Clara County Office of Supportive Housing’s Point-in-Time count, conducted every two years and most recently in 2025, displayed an 8.2% increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness since 2023, from 9,903 to 10,71118. While youth homelessness was not explicitly highlighted in the count, the broader issue remains clear. Cascading homelessness as a result of generational poverty remains a major determinant of youth homelessness, and an increase in the number of unhoused families certainly indicates an increase in the number of unhoused youth. PCIS staff observed trends that confirmed this; staff across the board agreed that the number of unhoused students at ESUHSD schools has increased significantly in the past few years.

Family Instability

For many, homelessness begins with family instability. Addiction, abuse, untreated mental health conditions, or rejection often precede housing loss, leading to absenteeism and loss of school-based resources. ESUHSD’s PCIS program aims to intervene by connecting students to mental health professionals and supporting parents with resources such as counseling or parenting classes. Still, many students navigate resources alone due to limited family support.

PCIS staff emphasized the depth of this challenge. At Evergreen Valley High School, at least 27 students were identified as unhoused, with many deterred by inaccessible city housing information. Without parental support, access to housing applications is limited for youth, leaving many students with no resort but to take to the streets. At Yerba Buena High School, PCIS staff compared addressing symptoms without tackling family causes to “putting a band-aid on a broken leg.” Family rejection – particularly over gender identity or sexual orientation – was cited as a frequent cause, mirroring nationwide data. Per national surveys, majority of unaccompanied youth cite family conflict as their primary driver of homelessness.

Affordability

A more visible driver of youth homelessness is San Jose’s punishing housing market. The median rent price in San Jose is $3,20019, with the lower-income neighborhoods in East San Jose having an average rent of $2,338 per month. Skyrocketing prices make it difficult even for families with multiple working members to stay afloat. The situation is even more dire for those living paycheck to paycheck without access to affordable housing or social safety nets.

By the numbers:

- ESUHSD’s internal surveys identified 1,000+ students as unhoused or unstable during the 2023-2024 academic year, with the Point-in-Time count that year only identifying 646 unhoused youth. This makes San Jose the city with the highest per-capita youth homelessness rate in the United States20.

- A 2024 survey at San Jose State University reported that 2% of students experienced homelessness during the academic year, with many living in cars near campus21.

- Among the unhoused adults in San Jose, 24% attribute their homelessness to losing their job and consequently being unable to pay rent22.

Affordability often serves as the catalyst for entire families to become unhoused. While homeless youth fall into two buckets – unhoused alongside their family, or living alone and unaccompanied – the vast majority of students that are unhoused along with their family are forced into their living situation due to unaffordability. Housing resources like California’s Project HomeKey or transitional housing through nonprofits often have restrictive eligibility or time limits, excluding many students who fall outside formal definitions of “unaccompanied” or chronically “homeless.” One PCIS at Independence High School – the largest school in ESUHSD, with over 100 enrolled McKinney-Vento students – recounted that for many students and parents, the question lies between feeding their family, paying rent, or buying a new pair of shoes.

Educational Disengagement and System Gaps

Causes: Limited School Capacity and Resource Constraints

Schools within the East Side Union High School District (ESUHSD) serve as critical stabilizing environments for students experiencing homelessness. However, many face deep structural limitations that undermine their ability to identify and support at-risk youth early. Interviews conducted for this study included six Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS) from different ESUHSD high schools, one nonprofit leader, and three students referred through the PCIS program. Across participants, a shared theme emerged: the urgency of identifying at-risk students before disengagement.

ESUHSD largely relies on enrollment surveys, self-disclosure, or red flags like absenteeism or missing documents to identify struggling youth. As one PCIS noted, “By the time we find out, the student has already disengaged.” Rolling budget cuts have done little to help the situation. PCIS staffing has been reduced to just one specialist per school in areas with poor funding, limiting capacity for early intervention. As a result, basic needs are often met through teacher donations and improvised “closets” rather than district programs.

Outside of school hours, district staff can do little to help, making attendance even more integral to supporting students. Many PCIS staff have given out their personal phone numbers to students to reach out in times of crisis but are often stretched too thin–many described feeling “tied up” outside of school hours, unable to balance their personal lives while also offering consistent evening or emergency support. One participant noted, “Homelessness doesn’t stop at 3 p.m, but we have to.”

Inadequate infrastructure compounds the issue. Parent Centers – offices where PCIS staff meet with students and parents – lack consistent access to supplies or hygiene facilities like washers and dryers. Several sites rely on donations and ad-hoc partnerships to sustain basic services.

When asked how the city can support initiatives to combat youth homelessness, staff unanimously agreed that more than policies and programs, funding was by far the most needed resource. But funding ultimately goes back to the state, and relies on taxpayer money. Paradoxically, the high housing prices in San Jose and their high-income residents are what keeps the public school system and existing programs afloat, but also contribute to wider income disparities and higher costs of living that further drive homelessness. It remains unknown whether more funding will become available in the coming years, but it is clear that funding is the single most important criterion for making schools better equipped to handle the youth homelessness crisis.

Effects: Student Disengagement and Systemic Consequences

The impacts of these limitations manifest most clearly in student disengagement. Across interviews, both staff and students emphasized how housing instability disrupts attendance, concentration, and connection to school. Students described the emotional toll of navigating multiple stressors – unstable shelter, family separation, and stigma – while trying to maintain academic performance. “It’s not that I don’t care about school,” one student shared, “it’s just the last thing I prioritize when there’s no one to watch my siblings during the day.”

The downstream effects extend beyond academic performance. Chronic absenteeism among unhoused youth contributes to widening achievement gaps, lower graduation rates, and long-term socioeconomic disadvantage. McKinney-Vento students and students with high disciplinary referral rates were the least likely to graduate among all four sampled schools, and the most likely to need to attend remedial courses to make up failed classes.

In short, limited school capacity acts as both a cause and amplifier of educational disengagement. The lack of structural resources prevents timely intervention, allowing instability to escalate into disengagement and dropout. This relationship serves as the basis for a central finding of this study: even with strong staff commitment, the ability to translate policy into meaningful support depends on sustained investment in school staffing and infrastructure.

Systemic Barriers and Marginalized Identities

Certain groups – undocumented, recently immigrated, LGBTQ+, and BIPOC youth – face heightened risk and fewer options for support. Many undocumented students cannot access foster care or public benefits, leaving them reliant on youth shelters like the Bill Wilson Center in San Jose, which faces strict intake limits and insufficient capacity.

Information asymmetry also persists between high-level systems and local provision. At Overfelt High School, where many students are both unhoused and have undocumented immigration status, staff reported being told to divert unaccompanied youth from the foster care system, despite legal protections ensuring their eligibility. Under the 2003 Foster Care Non-Discrimination Act (AB 458)23, discrimination in the foster care system on the basis of immigration status is prohibited. However, this protection is often miscommunicated or inconsistently applied at the school and district levels. One social worker reported being told that undocumented students were barred from entering the foster care system and did not know there were legal protections in place. As a result, students are routinely denied access to supports they are legally owed, reflecting a broader pattern of misinformation, weak policy enforcement, and uneven implementation. When such information gaps exist, resources provided in theory never actually reach the people they are intended to help, exacerbating the issue.

Barriers such as language, complicated applications, and outdated websites further hinder access to resources. While San Jose invests millions into encampment management and interim housing, little funding is directed specifically towards youth homelessness. As one PCIS noted, “We have the money. We’re just not allocating it where it matters the most.”

Conclusion

The primary determinants of youth homelessness in San Jose are deeply interconnected and can broadly be synthesized into a few distinct categories:

- Family crises push students out of the home;

- Unaffordable housing leaves them with nowhere to go;

- Underfunded schools delay identification and support;

- And structural exclusions trap the most vulnerable in invisible cycles of displacement.

Addressing this crisis, therefore, requires more than temporary shelters or donated clothes. It demands systemic change, upstream investment, and a commitment to reaching students before they disappear from view.

Case Study on School-Based Programs

Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods case study design focused on 4 schools across East Side Union High School District in San Jose, California – Evergreen Valley High, Overfelt High, Yerba Buena High, and Independence High. The schools were selected to capture variation in resource levels and demographics.

Data Sources and Time Frame

Quantitative data were drawn from district-level McKinney-Vento identification records maintained by individual schools’ PCIS staff. These records spanned two academic years – 2023-24 and 2024-25 – and included student counts and demographic breakdowns. Data was collected from individual schools and aggregated for the purpose of this study.

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted between February and June 2025. The interview sample included:

- Six Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS) – two from Evergreen Valley High School, two from Independence High School, and one each from Yerba Buena and Overfelt High School.

- One nonprofit leader, Nathan Ganesan, from a local organization, Community Seva, dedicated to supporting the unhoused.

- Three students referred through the PCIS program who were identified as McKinney-Vento eligible.

This brought the total interview sample to N = 10 participants.

Semi-structured interviews were designed to explore:

- The definitions and criteria used to classify youth homelessness;

- Processes for early identification (referrals, surveys, registration);

- Types of support offered (transportation, food, mental health counseling, hygiene and health resources);

- Partnerships with nonprofits and external agencies;

- Barriers to providing support;

- Perceived gaps in city and district policy; and

- Recommendations for systemic improvement.

Data Analysis

To explore the relationship between staffing capacity and early identification outcomes, the study compared McKinney-Vento student identification rates across the four selected schools.

To avoid confounding staffing with general implementation quality, this study defined school capacity using a composite index that captures two measurable dimensions:

- Staffing Score: A two-point index based on the capacity of school staff. All sampled schools had relatively similar student populations. Schools with two PCIS staff (the district-recommended amount) were considered exemplary, with a score of 2. Schools with 1 PCIS staff were considered satisfactory, with a score of 1. Schools with no PCIS staff were considered subpar, with a score of 0.

- Resource Access Score: A three-point index based on presence of (a) full time Parent Center operations, (b) dedicated McKinney-Vento funding line item in school budget, and (c) availability of basic material supports (e.g. hygiene facilities, food pantry. Each criterion was coded 1 (present) or 0 (absent), adding up to a total score ranging from 0-3.

Both variables were standardized to produce a Capacity Index (a score between 0-5) for each school. Objective cutoffs were then applied as follows:

High-Capacity schools: Capacity Index ≥ 3

Low-Capacity schools: Capacity Index < 3

This procedure generated two high-capacity sites;

- Overfelt High (Staffing Score: 2, Resource Access Score: 2)

- Yerba Buena High (Staffing Score: 2, Resource Access Score: 3)

and two low-capacity sites:

- Evergreen Valley High (Staffing Score: 1, Resource Access Score: 1)

- Independence High (Staffing Score: 1, Resource Access Score: 1)

To assess the robustness of the results, alternative operationalizations were tested:

- Model 1: Staffing Score alone

- Model 2: Resource Access Score alone

- Model 3: Capacity Index, default model.

Results were consistent across all models. The direction and strength of association remained positive across all models, suggesting that the link between school capacity and identification outcomes is not dependent on how capacity is measured.

A mixed-methods approach was used to analyze the data:

- Qualitative data were transcribed and coded thematically using an inductive approach. Recurring themes such as “budget constraints,” “early detection,” and “cross-agency barriers” were identified.

- Quantitative data were analyzed descriptively, comparing identification rates in schools with a capacity index of 3 or more versus those with a score of less than 3.

- Findings from both components were integrated to provide a comprehensive view of how staffing capacity influences early intervention.

Semi-structured interviews were transcribed using Otter.ai transcription software. All coding and analysis were conducted manually. To ensure coding consistency, transcripts were reviewed multiple times to establish familiarity with the data. A coding framework was developed inductively, with codes emerging from the data and refined iteratively throughout the analysis process. The researcher maintained detailed code definitions and revisited earlier transcripts after finalizing the codebook to ensure consistent application across all interviews. As a single coder, traditional intercoder reliability metrics were not applicable; however, consistency was maintained through systematic documentation and reflexive review of coding decisions.

Quantitative data were analyzed descriptively, comparing McKinney-Vento identification rates across schools using the Capacity Index framework described above. Pearson correlation analysis and independent-samples t-tests were conducted to examine relationships between staffing capacity and identification outcomes. See Appendices A and B for the Interview Protocol and Coding Framework.

Findings

The findings are organized into themes: depth of support, community partnerships, relationships and trust, and shared systemic barriers.

Quantitative Correlation

Analysis of McKinney-Vento records revealed a strong positive association between staffing levels and identification outcomes.

| Staffing Capacity | Average Identified McKinney-Vento Students per 1,000 | Median % Identified by Mid-Year | Sample Description |

| 2+ PCIS staff (n=2) | 54 | 70% ± 4.2 | Overfelt High, Yerba Buena High (2+ PCIS staff) |

| 1 PCIS staff (n=2) | 31 | 40% ± 5.8 | Evergreen Valley High, Independence High (≤1 PCIS staff) |

A Pearson correlation analysis revealed a strong positive relationship between staffing capacity and mid-year identification rate (r = .86, p = .032, df=2). This suggests that schools with greater institutional capacity tend to identify students experiencing homelessness earlier in the academic year.

An independent-samples t-test further confirmed that high-capacity schools identified a significantly greater proportion of McKinney-Vento students (M = 70%, SD = 4.2) than low-capacity schools (M = 40%, SD = 5.8).

Alternative definitions of capacity (staffing ratio only; resource access score only) produced similarly strong relationships: r = .79 (p = .047) for staffing ratio and r = .74 (p = .061) for resource access. These consistent results indicate that the observed association is robust and not dependent on how “capacity” is defined.

Qualitative Insights

A clear distinction emerged between high- and low-capacity schools in the breadth and depth of support provided to students. At Evergreen Valley High School, a broad lack of funding and a single-PCIS model resulted in more reactive, than proactive interventions. The former PCIS staff described situations where students were only flagged after weeks of absence: “We know the signs, but we don’t have the hands to follow up on every single lead. By the time we get there, the student is already disengaged.” Similar experiences were detailed at Independence High School, which has the highest number of McKinney-Vento students in ESUHSD, and frequently experiences staffing changes. Volatile funding and unpredictable staffing make it difficult for PCIS staff to build long-term relationships with students, and a lack of structural support prevents universal access to hygiene facilities and resources for students. “We triage constantly,” the PCIS from Independence explained. “That means long-term projects, like connecting with a family before eviction, fall through the cracks.”

By contrast, Yerba Buena High School’s more focused two-PCIS approach embedded the early identification process into multiple touchpoints, with the hub of student-staff interaction in their Parent Center on campus. District-wide surveys, targeting outreach via social media, and teacher training to spot trigger words (“living in a car,” “staying with friends”) encouraged prompt follow-up calls. The head PCIS explained, “We start connecting students to resources as fast as we can. There’s a small window where we can keep them engaged.” Staff implemented a “visibility without stigma” model – such as open events like the Vintage Fair, where all students could access clothing – to normalize resource use. As one PCIS noted, “We try to make [the Vintage Fair] in such a way that one knows who’s here because they need help and who’s here for fun.” This approach reflects universal-access models in public health, embedding assistance within ordinary school experiences.

Overfelt High School operates an on-campus health clinic that students without health insurance can utilize for basic healthcare, and social workers work closely with PCIS staff to ensure consistency across both physical and mental health support and more resource-oriented help.

Community Partnerships: Collaboration and Resource Flow

High-capacity schools reported more active engagement with local organizations such as the Bill Wilson Center24, Sacred Heart25, Second Harvest26, and City Peace Project27. Dedicated time allowed PCIS staff to build and maintain relationships with agency representatives, coordinate referrals, and ensure warm hand-offs. At Overfelt High School, for example, the PCIS and school social worker co-managed partnerships with the on-campus Overfelt Community Clinic and Stanford medical staff, thereby providing preventative care and connecting students to housing resources.

On the other hand, low-capacity schools had to prioritize immediate crises over preventative or holistic support. For example, clothing drives and hygiene kit distribution were often delayed or scaled down because the single PCIS could not both manage logistics and provide one-on-one case management. At low-capacity schools, the necessity of managing large caseloads limit opportunities for informal, trust-building interactions. Students often avoided disclosure until circumstances became acute.

Staffing capacity influenced the ability to build trust-based relationships, which in turn impacted self-disclosure rates. Students in high-capacity schools were more likely to voluntarily disclose housing instability, knowing they had established rapport with PCIS staff.

Parent Centers in high-capacity and low-capacity schools alike serve as safe spaces for McKinney-Vento students, and PCIS staff typically stock their offices with snacks and resources for students to the best of their ability.

Shared Systemic Barriers

Across both staffing models, participants identified district and citywide barriers:

- Funding Instability: Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP)28 budget reductions disrupted staffing and resource availability.

- Housing market pressure: Even when students received housing referrals, lack of affordable units meant many remained in precarious arrangements.

- Eligibility restrictions: Programs like Project HomeKey often excluded unaccompanied minors without parental documentation.

- After-hours limitations: PCIS staff expressed frustration at their inability to provide evening or weekend crisis support due to contractual restrictions and burnout risks.

One PCIS summarized the frustration: “We can do a lot within the school day, but homelessness doesn’t keep school hours. The calls come at 10 p.m., and by then, I’m off the clock and have to watch my own kids at home. There’s not much I can do except tell them to hang on until morning.”

The mixed-methods findings collectively demonstrate that institutional capacity fundamentally shapes both the reach and quality of school-based interventions for students experiencing homelessness. Quantitative results confirmed a statistically significant association between staffing levels and early identification, while qualitative evidence illustrated how that capacity translates into deeper, more relational, and better coordinated support.

High-capacity schools that identified McKinney-Vento students earlier also showed higher mid-year attendance rates, longer durations of continuous enrollment, and lower drop-out rates, indicating stronger sustained engagement. These initial trends are generally associated with higher graduation rates for McKinney-Vento students and higher enrollment rates in four-year and two-year colleges, according to interviewees. Qualitative interviews further reinforced this pattern: students in these schools described consistent check-ins, quicker follow-up on absences, and a stronger sense of belonging that encouraged ongoing participation.

Low-capacity schools, in contrast, were constrained to reactive responses and fragmented collaboration, despite strong individual commitment among staff. Across all sites, systemic pressures, particularly unstable funding and restrictive housing policies, remained persistent barriers that limited even the best-equipped schools. These converging insights underscore the central conclusion of this study: effective implementation of the McKinney-Vento Act depends not only on awareness or compliance, but on the structural and relational capacity of schools to operationalize equity in practice and sustain student engagement over time.

Discussion: Impact on Youth and Community

The effects of youth homelessness ripple far beyond the loss of stable housing. For the students affected, the consequences are both immediate and long-term – academic decline, mental health issues, lost educational opportunity, and future financial instability. For the community, youth homelessness perpetuates cycles of poverty, drives up public service costs, and undermines efforts toward equity and inclusion.

Educational Impact

Unhoused youth are at significantly higher risk of chronic absenteeism, academic disengagement, and eventual dropout29. When a student lacks a place to study, a reliable way to get to school, or even basic hygiene resources, their ability to focus, succeed, and graduate is severely impaired. Conversely, when identification is delayed, students tend to disengage in silence, a pattern repeatedly observed by staff. Staff across ESUHSD noted that many McKinney-Vento students begin disengaging in silence, skipping school to avoid embarrassment over unwashed clothes or visible stress. “They don’t tell anyone. They just stop showing up,” one PCIS shared. “And by the time we notice, they’ve already fallen behind.” Findings of the study reinforce that staffing capacity is a key indicator of educational stability, as it shapes how quickly and effectively schools can intervene before disengagement occurs.

Mental and Physical Health

Homelessness is associated with heightened risks of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and substance abuse. San Jose’s 2023 Homeless Census records that 31% of unhoused individuals reported having psychiatric or emotional conditions, 29% reported having PTSD, 26% struggled with drug or alcohol abuse, 25% had chronic health problems, and 9% had intellectual or developmental disabilities22. Many of these mental health issues begin at young ages and exacerbate over time. Without stable shelter, students face exposure to violence, exploitation, and weather-related illnesses.

While many schools offer on-site mental health services, staff are often bogged down – with an average of 2,000 people in each high school30, ESUHSD schools typically employ 1-2 mental health professionals to handle students’ academic and emotional stress across a wide range of backgrounds and incomes. It becomes difficult to focus specifically on struggling McKinney-Vento students without specialized mental health professionals, especially when the schools’ mental health professionals also double as social workers, such as in the case of Evergreen Valley High School. In contrast, high-capacity schools reported stronger coordination with both internal and external mental health professionals, and students described feeling supported by “familiar faces” who regularly checked in.

Economic Costs of Delay

While the moral and social imperatives are clear, the economic implications of delayed identification are equally significant. Lower attendance among unidentified students directly reduces district revenue through California’s Average Daily Attendance (ADA) formula31, meaning schools lose funding precisely when their needs are highest. Each unrecognized student represents lost instructional time and a missed opportunity to access federal resources or local grants.

Over time, these missed interventions escalate public costs: the longer youth remain homeless, the more likely they are to become chronically unhoused as adults, increasing long-term reliance on public systems such as emergency rooms, public defense, and social services. Interviews conducted by San Jose District 8’s Youth Council Committee observed that lack of medical insurance leads to an overreliance on emergency services, especially urgent care. This has bogged down the capacity of first responders and emergency workers, contributing to a long-term increase in taxpayer money being dedicated to covering the costs of unnecessary emergency room visits. Studies show that every dollar invested in youth homelessness prevention saves the public several dollars in long-term care, shelter, and incarceration costs.

Analysis of Existing Policy Landscape

Before proposing new recommendations, it is necessary to ground the study’s findings within the current policy environment of San Jose. The City of San Jose has made homelessness a top policy priority, investing in transitional housing, safe parking programs, and interim shelter communities. Major city led initiatives include programs such as Project HomeKey, Safe Parking Initiatives, and the Services, Outreach, Assistance, and Resources (SOAR) program32. However, youth experiencing homelessness, especially unaccompanied minors, remain underrepresented in both funding allocations and eligibility structures. The City Council approved a 2025-26 operating budget of $6.4 billion, before taxes. This included $55 million of Measure E funding, a Real Property Transfer Tax intended to fund affordable housing and services for the homeless population. Under Measure E, $47 million was dedicated towards Homeless Support Programs (encampment management, rehousing services, outreach, sanitation, and maintenance and operation of interim housing); $5.2 million towards homeless prevention and rental assistance services, and $2.8 million in administrative costs33. The overwhelming share of resources supports encampment management and adult shelter capacity. This funding imbalance leaves ESUHSD and the PCIS program to shoulder the responsibility of youth identification and stabilization, often without formal coordination with city housing efforts.

Within the community sector, nonprofit partners like the Bill Wilson Center, Sacred Heart, and Second Harvest fill critical service gaps by offering shelter and transitional housing, case management, and emergency food services. These organizations, however, face persistent constraints in youth-specific capacity. Interviews with school staff, who often connect students with community-offered resources, revealed that waitlists for under-18 placements at shelters often exceed available beds, and eligibility criteria tied to documentation status further exclude many students. While community agencies maintain strong relationships with school PCIS staff, collaboration typically depends on personal rapport rather than formal data-sharing or joint case-management protocols. This ad-hoc coordination leads to duplication in some areas and service gaps in others, particularly when placing unaccompanied students in community housing systems.

The findings from this study affirm that schools serve as frontline institutions in homelessness prevention. Adequate staffing enables early intervention, coordinated partnerships with housing agencies, and sustained student engagement, all of which reduce both community and economic costs over time.

In short, youth homelessness is not just a student issue. It is a community problem, and the cost of inaction is steep, both morally and economically. Strengthening school capacity for early identification and sustained engagement offers one of the most direct, evidence-based paths toward breaking cycles of poverty and promoting educational equity in the long term.

Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged.

- Data completeness and reliability: The correlational analysis relied on district records, which may underrepresent the actual scope of youth homelessness. Students frequently underreport housing instability due to stigma or fear, and identification often depends on subjective staff assessments.

- Sample size and scope: While interviews with PCIS staff and nonprofit partners provided valuable insights, the sample was limited to a handful of schools within ESUHSD. The findings may not generalize to all schools in the district or to other regions with different demographic and policy contexts.

- Confounding factors: Variations in outcomes across schools may not be attributable solely to staffing levels. Differences in school leadership, neighborhood housing availability, and proximity to community nonprofits could also shape identification and intervention rates.

- Time-Bound analysis: This study captures a snapshot during the 2023-2024 and 2024-2025 school years. Trends may shift in future years depending on changes in district funding, city housing policy, or state-level investments in youth homelessness prevention.

These limitations emphasize the need for further research, including longitudinal studies that track student outcomes over time and comparative analysis across districts with different funding and staffing models.

Conclusion & Policy Recommendations

Youth homelessness in San Jose, particularly within the East Side Union High School District (ESUHSD), represents a crisis that is both widespread and largely invisible. Unlike adult homelessness, which is often visible in encampments of shelters, youth housing instability manifests in subtler forms – couch surfing, living in garages, or temporary stays with extended family – those rarely draw public attention. This invisibility contributes to delayed identification, fractured support, and the erosion of students’ educational and developmental trajectories.

This study provides evidence that school-based support staff capacity is strongly correlated with early identification and intervention. Schools with two or more full-time Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS) consistently identified a greater percentage of McKinney-Vento students, flagged them earlier in the academic year, and offered broader wraparound services compared to schools operating with one or fewer PCIS staff. The qualitative interviews further revealed that staffing capacity enables more consistent relationship-building, stronger trust with students, and sustained coordination with community partners – all of which are critical factors in effective intervention.

At the same time, the study highlights the limits of what schools can accomplish alone. Even when adequately staffed, schools operate within structural conditions – skyrocketing housing costs, restrictive eligibility requirements for aid, and volatile public funding – that constrain their ability to fully address the crisis. The ESUHSD case study thus illustrates both the importance of school-based intervention and the necessity of systemic reform beyond the education sector.

Policy Recommendations

Despite its limitations, this study provides a clear path forward with actionable steps:

A. Restore and Expand School-Based Support

Reinvest in the Parent and Community Involvement Specialist (PCIS) program across ESUHSD to ensure at least two full-time specialists per school. Quantitative results show that schools with two PCIS staff identified 70 percent of McKinney-Vento students by mid-year, compared to 40 percent in single-staff schools. Sustaining these ratios is therefore an evidence-backed strategy for improving attendance and engagement.

Funding Strategy:

- Dedicate a minimum of 5 percent of Measure E funds (≈ $2.75M) to youth-focused school initiatives, which would fully fund two PCIS positions at every ESUHSD high school for five years.

- Use Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) dollars to prioritize homelessness response in schools with 30 or more identified McKinney-Vento students.

- Establish stable operating funds for hygiene closets, food pantries, and campus washer-dryer facilities, which were identified as low-cost but high-impact supports in the qualitative findings.

- Introduce evening and weekend crisis-response shifts or text-based hotlines to address timing gaps noted by PCIS staff.

B. Fund Targeted Housing for Unaccompanied Youth

Expand the availability of short-term and transitional housing for youth under 24, particularly those who are undocumented, LGBTQ+, or recently immigrated. Qualitative data revealed repeated exclusion of these groups from foster care and housing programs despite existing legal protections (e.g., AB 458).

Funding Strategy:

- Reallocate a portion of Measure E’s encampment management budget to establish youth-dedicated transitional facilities and flexible hotel-voucher programs linked to school referrals.

- Offer public-private partnership incentives for youth-friendly developments, ensuring trauma-informed design and inclusive eligibility.

- Coordinate allocations through a joint City-District Youth Housing Fund, preventing duplication across agencies and ensuring accountability for outcomes.

C. Create a Centralized Youth Housing Digital Resource Portal

Develop an accessible, multilingual digital portal that integrates school, city, and nonprofit resources, mirroring successful regional data-integration models. Students and staff reported fragmented access to information, reinforcing the need for a single, real-time system of care.

Implementation Elements:

- Include shelter bed availability, drop-in center hours, hotel voucher access, PG&E discounts, and transitional housing openings.

- Partner with community organizations to keep listings current.

- Integrate with the City of San José website and promote through QR codes in schools, libraries, and social-media channels.

- Involve youth in co-designing the interface to ensure usability and cultural relevance.

D. Establish a San Jose Youth Homelessness Task Force

Create a permanent interagency task force composed of youth with lived experience, school leaders, housing advocates, and city officials to ensure ongoing coordination and fiscal accountability. This structure would institutionalize the informal collaboration patterns observed between PCIS staff and community partners.

Key Responsibilities:

- Monitor and publicly report annual outcomes: attendance, graduation, housing placement, and service utilization.

- Hold quarterly open meetings with published agendas and reports.

- Recommend budget allocations for youth homelessness prevention in future Measure E cycles.

- Provide stipends and voting rights for youth members to ensure authentic participation.

In sum, these policy recommendations translate the study’s findings into actionable strategies for systemic reform. The evidence demonstrates that early, school-based identification and dedicated youth housing investment are associated with measurable educational and fiscal benefits. Accordingly, municipal leaders, educational administrators, and community partners must prioritize coordinated implementation and sustained funding commitments to address youth homelessness comprehensively.

Closing Reflection

Youth homelessness in San Jose is a silent crisis with loud consequences. It takes root in unstable homes, worsens in unaffordable housing markets, and deepens in underfunded schools and disconnected systems. But it does not have to be inevitable.

This study affirms that youth homelessness is preventable. Quantitative analysis revealed a strong positive relationship between staffing capacity and early student identification (r = .86, p = .032), indicating that institutional resources are strongly associated with identification outcomes for unhoused youth. Qualitative findings further demonstrated that staffing capacity influences the depth of support, quality of relationships, and effectiveness of community partnerships. Schools already possess many of the tools needed for early detection and intervention, but their impact depends on the presence of adequate staffing and the alignment of resources across education, housing, and social services. In ESUHSD, the difference between a school with two PCIS staff and one with a single overburdened specialist can determine whether dozens of students are identified and supported or whether they will fall through the cracks.

Yet staffing alone will never be sufficient. The determinants of youth homelessness – family instability, unaffordable housing, systemic exclusion – require structural solutions that extend beyond schools. A comprehensive response must combine adequately funding school-based support with city and state-level investments in youth-centered housing and prevention strategies.

Ultimately, the ESUHSD case reveals both the power and the limits of schools in addressing youth homelessness. It calls for a collective commitment by the education system, policymakers, and communities to move beyond reactive responses and invest in upstream interventions that ensure stability, dignity, and opportunity for every young person.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals who generously shared their experiences and insights to contribute to this case study. Their openness and willingness to contribute made this research possible. I am also deeply thankful to my mentor, Professor Larry Rosenthal, for his invaluable guidance, thoughtful feedback, and constant encouragement throughout this project.

Appendix A: Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

Interview Protocol for Parent and Community Involvement Specialists (PCIS)

Opening:

- Can you tell me about your role at this school and how long you’ve been working with students experiencing housing instability?

- How many students do you currently work with, and what does a typical day look like for you?

Main Questions:

- Definitions and Identification

– How does your school define or identify youth homelessness?

– What tools or surveys do you use to identify homeless students?

– Probe: Do you rely on enrollment forms, self-disclosure, teacher referrals, or other methods?

– Are students and families generally willing to self-identify as homeless? Why or why not?

– Probe: What are the barriers to self-disclosure? Stigma? Fear? Lack of awareness? - Support Services and Resources

– What specific resources or services does your school offer to students experiencing homelessness?

– How does the school coordinate support?Probe: Transportation? Meals? Hygiene facilities? Academic accommodations?Do you feel the school has enough resources to meet the needs of these students? Why or why not?

– What kinds of mental health support are available to homeless students? - Family Dynamics

– How often do you find that family instability (addiction, domestic violence, etc.) is a root cause?

– What role do parents or guardians play in the school’s support process?

– Probe: Are parents engaged? Are there barriers to parental involvement? - Community Partnerships

– Are there any nonprofits, shelters, or local programs you partner with to support homeless youth?

– Probe: Bill Wilson Center? Sacred Heart? Second Harvest? Others?Do you feel community organizations are accessible and responsive?Is there any organization you wish your school could partner with?

– Probe: What gaps exist in community services? - District and Funding Structures

– Is there district-wide coordination on addressing youth homelessness, or is it more school-specific?

– Have you noticed an impact from budget cuts or shifting funding sources (like McKinney-Vento)?How is LCAP or other funding used in your school for these students?

– Probe: Is funding adequate? Stable? Predictable? - Challenges and Barriers

– What are the biggest challenges your team faces in supporting these students?

– Are there barriers to helping students outside of school hours?Probe: Evenings? Weekends? During breaks?

– What services do you think are missing right now? - Recommendations and Policy Changes

– If you could suggest one change at the city or district level, what would it be?

– What kind of policy or structural support do you believe could make a real difference?

– Would you support forming a youth-led task force on this issue? Would you want to be involved?

Closing:

- Is there anything else you think is important for me to understand about youth homelessness at your school or in San Jose?

- Would you be willing to connect me with students or families who might be willing to share their experiences?

Interview Protocol for Nonprofit Partners

Opening:

- Can you tell me about your organization and your role in serving youth experiencing homelessness in San Jose?

- How long have you been working in this field?

Main Questions:

- Service Provision

– What services does your organization provide specifically for youth experiencing homelessness?

– How many youth do you serve annually?

– Probe: Emergency shelter? Transitional housing? Case management? Food? Other resources? - Eligibility and Access

– What are the eligibility requirements for youth to access your services?

– Probe: Age restrictions? Documentation requirements? Accompanied vs. unaccompanied youth?What percentage of youth who need services are you able to serve?

– Probe: Waitlists? Capacity constraints? - School Partnerships

– How do you work with schools like those in ESUHSD?

– What does the referral process look like from schools to your organization?

– Probe: How could school partnerships be strengthened? - Systemic Barriers

– What are the biggest gaps in services for youth experiencing homelessness in San Jose?

– Are there populations that are particularly underserved?

– Probe: LGBTQ+ youth? Undocumented youth? Recently immigrated youth? - Policy and Funding

– How is your organization funded?

– Have you seen changes in funding availability over the past few years?

– What policy changes would most help youth experiencing homelessness? - Recommendations

– If you had unlimited resources, what would you do differently?

– What role should schools play in addressing youth homelessness?

Closing:

- Is there anything else you’d like to share about youth homelessness in San Jose?

Interview Protocol for Students

Note: All student interviews were conducted with parental consent (if applicable) and student assent. Students were informed of confidentiality protections and their right to skip questions or end the interview at any time.

Opening:

- Thank you for agreeing to talk with me. I’m trying to understand what it’s like for students experiencing housing challenges and how schools can better support students. Everything you share will be kept confidential.

- Can you tell me a little about yourself? What grade are you in?

Main Questions:

- Housing Experience

– Can you tell me about your current living situation?

– Probe: How long have you been in this situation?

– If comfortable: What led to your housing instability? - School Experience

– How has your housing situation affected your experience at school?

– Probe: Attendance? Ability to focus? Relationships with teachers or peers?

– Have you been able to keep up with your classes? - Support Received

– How did your school learn about your housing situation?

– What kind of support have you received from your school?Probe: From PCIS staff? Teachers? Counselors?

– Has the support been helpful? Why or why not? - Barriers and Needs

– What has been the hardest part of your situation?

– Is there support you needed but didn’t receive?

– Probe: Transportation? Food? Clothing? A place to study? Mental health support? - Recommendations

– If you could tell school staff one thing that would help students in situations like yours, what would it be?

– What would make it easier for students to ask for help?

Closing:

- Is there anything else you’d like to share?

- Thank you so much for sharing your experiences with me. Your insights will help schools better support students.

Note: All interviews were conducted between February and June 2025. Interviews ranged from 30-60 minutes in length and were conducted either in-person at school sites or via virtual meetings. All participants provided informed consent, and students provided assent with parental consent where applicable. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission and transcribed using Otter.ai transcription software.

Appendix B: Coding Framework

Overview

The coding framework was developed inductively through iterative review of interview transcripts. Initial codes emerged from open coding of the first three transcripts, followed by axial coding to identify relationships and patterns across interviews. The codebook was refined throughout the analysis process and finalized after all transcripts were coded. Codes were organized into four overarching categories: (1) Determinants of Youth Homelessness, (2) School-Based Response Systems, (3) Systemic Barriers, and (4) Recommendations for Policy and Practice.

Category 1: Determinants of Youth Homelessness

| Code | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Example Quote |

| Family Instability | References to family conflict, dysfunction, rejection, abuse, addiction, or mental health issues as precipitating factors for housing loss | Must explicitly link family dynamics to housing instability or student displacement | “We see unstable parents dealing with addiction and gambling. It’s hard to motivate parents to motivate their kids when they’re struggling themselves” (PCIS, Evergreen Valley HS) |

| Family Rejection (LGBTQ+) | Specific instances of youth being rejected or forced out due to gender identity or sexual orientation | Must identify LGBTQ+ identity as the cause of family conflict or displacement | “Sometimes they’re dating someone and they get kicked out. Then they’re living in the car or living with their boyfriend or girlfriend. They’re still unaccompanied youth even if they’re with a partner” (PCIS, Yerba Buena HS) |

| Housing Affordability Crisis | Discussion of rent burden, housing costs, eviction, or economic displacement as drivers of homelessness | Must reference specific costs, market conditions, or inability to afford housing | “For many families, it comes down to: do I feed my family, pay rent, or buy shoes? That’s the choice they’re making” (PCIS, Independence HS) |

| Immigration/Deportation | References to immigration status, deportation, or asylum-related housing instability | Must connect immigration circumstances to housing loss or instability | “We have lots of immigrants at Overfelt. When parents get deported, the kids end up couch surfing with family and friends. These kids usually drop out of school” (PCIS, Overfelt HS) |

| Educational Disengagement | Discussion of how housing instability leads to academic withdrawal, absenteeism, or dropout | Must describe the process or impact of disengagement, not just identify it | “When the housing situation gets bad, kids usually just drop out of school” (PCIS, Overfelt HS) |

Category 2: School-Based Response Systems

| Code | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Example Quote |

| Early Identification | Discussion of processes, timing, or methods for detecting housing instability | Must reference identification methods (surveys, referrals, red flags) or timing of identification | “We ask a series of questions during the registration process. We train staff to listen for trigger words like ‘kicked out,’ ‘living in a car,’ ‘couch surfing,’ ‘all crammed in one room,’ or ‘can’t afford a place of our own.’ Those words tell us a student might be experiencing housing instability” (PCIS, Yerba Buena HS) |

| Self-Disclosure Barriers | References to stigma, fear, shame, or other factors preventing students from identifying themselves as homeless | Must identify barriers to voluntary disclosure | “Embarrassment and stigma are huge barriers. Students don’t want anyone to know what’s going on at home. I think there are probably way more homeless students than we even know about because people just don’t want to disclose that information” (PCIS, Yerba Buena HS & Independence HS) |

| Wraparound Support | Description of comprehensive, multi-faceted services provided to students (food, hygiene, transportation, counseling, etc.) | Must reference multiple types of support or coordinated service provision | “Our PCIS staff keeps a closet stocked with food, clothing, bus passes, school supplies, backpacks. We even have prom dresses for students who need them” (PCIS, Overfelt HS) |

| Care Team Meetings | References to regular coordination meetings involving admin, social workers, and PCIS staff to review student needs | Must describe collaborative case review process | “Every school has a care team made up of administrators, teachers, advisors, and social workers. We meet once a week to go through referrals and figure out who needs help, including students dealing with homelessness” (PCIS, Overfelt HS) |

| Staffing Capacity – High | References to adequate staffing (2+ PCIS), ability to provide proactive support, time for relationship-building | Must indicate sufficient human resources to meet student needs | “We used to have two PCIS staff members per school site. One was Spanish-speaking and one was Vietnamese-speaking. Now with all the budget cuts, we’re down to just one person per site, and we have to use a language line or ask other staff members to help translate” (PCIS, Independence HS) |

| Staffing Capacity – Low | References to insufficient staffing (1 or fewer PCIS), reactive responses, burnout, inability to follow through | Must indicate inadequate human resources or overwhelming caseloads | “I had one of my positions cut this year. We’ve been trying to keep everything going by using LCAP funding, but honestly the budget cuts have made it really, really hard to keep up” (PCIS, Evergreen Valley HS) |

| Parent Centers/Clothing Closets | Discussion of physical spaces where PCIS staff meet with students/families and distribute resources | Must reference Parent Center operations, facilities, or resources | “We have clothing closets at several schools including Oak Grove, Yerba Buena, and James Lick. Yerba Buena does this great Vintage Swap event. We’re even thinking about moving our Parent Center to a different classroom to make more space. The district gives us some materials, but honestly most of what we have comes from donations” (PCIS, Independence HS) |

| Relationship-Building/Trust | References to personal connections, rapport, trust, or relational capital between staff and students | Must describe the quality or importance of interpersonal relationships | “I tell parents and families they can text or call me anytime they need something. Technically I’m not expected to be available outside school hours, but I try to go to student events whenever I can because building those relationships really matters” (PCIS, Independence HS) |

| Visibility Without Stigma | Strategies to normalize resource access and reduce shame (e.g., open events, universal access models) | Must describe intentional efforts to destigmatize support-seeking | “We created the Yerba Buena Vintage Fair specifically so students wouldn’t feel embarrassed walking out of class to get help. The fair is open to everyone – any student can come browse clothes. Anyone can stop by our closet anytime. We want it to be for everybody, not just the McKinney-Vento students” (PCIS, Yerba Buena HS) |

| Teacher Training | References to staff development on identifying signs of homelessness and trigger words | Must describe training or awareness-building for school staff | “At the beginning of the year, our PCIS staff introduce themselves to teachers and give them a brief training on what trigger words to listen for. Teachers are actually pretty good at identifying students once they know the signs. We also constantly remind the office staff what to watch for when families are registering” (PCIS, Yerba Buena HS) |

Category 3: Systemic Barriers

| Code | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Example Quote |

| Funding Instability | References to budget cuts, volatile funding, LCAP reductions, or insufficient financial resources | Must identify funding as a constraint on services or staffing | “Our biggest problem is budget cuts. It really affects programs like LCAP and mental health resources. LCAP funding issues impact multiple special populations, and we’re losing staff positions because of it.” |

| After-Hours Limitations | Discussion of inability to provide support outside school hours (evenings, weekends, breaks) | Must reference time constraints or gaps in availability | “It’s really hard to provide support outside school hours. Evening connections are almost impossible, and no one is expected to do this work after school.” |

| Eligibility Restrictions | References to bureaucratic barriers, documentation requirements, or exclusionary criteria that prevent access to services | Must identify specific policies or requirements that exclude students | “For housing applications, students have to fill out interest forms and provide documentation like Social Security numbers. But some applicants can’t skip those fields, which blocks access for them.” |

| Undocumented Youth Barriers | Specific barriers faced by undocumented students in accessing foster care, housing, or public benefits | Must reference immigration status as a barrier to services | “Newcomers and refugees who come here alone can’t access foster care because they’re undocumented. Sometimes they end up living with sponsors who ask them to pay rent, and they just don’t have the resources.” |

| Information Asymmetry | Gaps between policy and implementation; misinformation about eligibility or rights; outdated resources | Must identify disconnect between what is available and what is communicated or accessible | “The information on the website is really outdated. Language resources and other info about county services aren’t easy to find. We need fewer barriers and better access.” |

| Fragmented Service Systems | Discussion of siloed agencies, lack of coordination, or gaps between education, housing, and social services | Must reference disconnection or lack of integration across systems | “The system doesn’t make it easy for people to get food or housing. There are so many steps and hurdles – it’s not a streamlined process at all.” |

| Limited Youth-Specific Housing | References to the absence or inadequacy of housing options designed for youth under 18 or under 24 | Must identify youth-specific housing capacity as insufficient | “Bill Wilson doesn’t have enough beds or resources for youth experiencing homelessness. We need more shelters specifically for young people – right now Bill Wilson is the only option.” |

| Healthcare Access Barriers | Discussion of missing or inadequate healthcare services for unhoused youth | Must identify healthcare gaps or access issues | “A lot of homeless people end up in the ER but get released in less than 24 hours because no one is paying their bills. Then they’re back on the street with hospital wristbands still on.” |

| Emergency Housing Gaps | References to insufficient hotel vouchers, temporary shelter, or crisis response capacity | Must identify gaps in immediate/emergency housing options | “Hotel vouchers are meant for emergencies, but people don’t always know about them. We need to make them more visible and accessible, and they shouldn’t get cut so quickly.” |

Category 4: Recommendations for Policy and Practice

| Code | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Example Quote |

| Restore School Staffing | Calls for increasing PCIS positions, maintaining 2+ staff per school, or investing in school-based capacity | Must propose specific staffing changes or funding priorities | “We used to have two PCIS staff members per school site. One was Spanish-speaking and one was Vietnamese-speaking. Now with all the budget cuts, we’re down to just one person per site, and we have to use a language line or ask other staff members to help translate” (PCIS, Independence HS) |

| Youth-Specific Housing Investment | Recommendations for dedicated transitional housing, shelter beds, or hotel vouchers for youth | Must propose youth-targeted housing solutions | “We really need more shelters that are specifically for youth. Right now, Bill Wilson is the only option, and it’s not enough.” |

| Cross-Sector Coordination | Calls for collaboration between schools, city agencies, and nonprofits; data sharing; joint task forces | Must propose improved coordination or integration across systems | “I support the Youth Task Force. We need schools, city agencies, and nonprofits to collaborate more closely.” |

| Centralized Resource Portal | Proposals for a digital platform, hotline, or hub consolidating information on housing, food, and services | Must propose a centralized information system | “We need a single hub for information on housing, food, and services—something that’s updated and easy to access, including in multiple languages.” |

| Policy Enforcement/Clarity | Recommendations to clarify eligibility, enforce existing protections, or simplify bureaucratic processes | Must address need for better implementation or communication of existing policies | “The application process should be easier, especially for non-English speakers. Students should be able to get into school even if they don’t have a birth certificate or other documents.” |

| Funding for Mental Health | Calls for increased mental health resources for students and families | Must propose mental health investment | “We need more funding for mental health support – for both students and their families. Supporting parents helps the students too.” |

| Resource Advertising/Awareness | Recommendations for better publicizing existing programs (PG&E CARE, Sacred Heart, hotel vouchers) | Must propose improved communication about available resources | “Resources like PG&E programs, Sacred Heart services, and hotel vouchers should be advertised more widely so people actually know they exist.” |

| Funding Reallocation | Calls to redirect existing budgets toward youth-specific needs; recognition that funding exists but isn’t allocated properly | Must propose specific changes to funding priorities | “Sometimes it feels like there’s no budget, but the money is there—it’s just not being allocated properly. We need to prioritize funding for youth-specific needs.” |

| Healthcare Integration | Proposals for school-based health clinics or mobile healthcare services for unhoused youth | Must propose healthcare solutions | “We need a full-time health clinic at Overfelt—something that offers checkups, preventative care, mental health services, sports physicals, and birth control for the whole community.” |

Additional Codes: Student Perspectives

| Code | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Example Quote |

| Housing Instability Impact on School | Student descriptions of how unstable housing affects their ability to attend, focus, or succeed in school | Must describe direct educational impact of housing situation | “It’s hard to focus on homework when you don’t know where you’re sleeping that night. Sometimes I just don’t come to school because I’m too tired from moving around” (Student) |

| Stigma/Embarrassment | Student expressions of shame, fear of judgment, or reluctance to seek help due to housing status | Must reference emotional barriers to disclosure or help-seeking | “I don’t want people to know I’m living in my car. It’s embarrassing. I try to act normal so no one asks questions” (Student) |

| Positive Staff Relationships | Student descriptions of helpful, supportive interactions with PCIS staff or teachers | Must identify specific staff members or supportive actions as meaningful | “Ms. [PCIS staff] gave me her number and told me I could text her anytime. That made me feel like someone actually cared” (Student) |

| Barriers to Accessing Resources | Student descriptions of difficulty navigating systems, understanding eligibility, or physically accessing services | Must identify specific obstacles from student perspective | “I tried to fill out the housing application but I didn’t understand all the questions. And they wanted my social security number, which I don’t have” (Student) |

| Basic Needs Challenges | Student references to lack of food, clean clothing, hygiene facilities, or safe places to study/sleep | Must describe concrete deprivations | “I haven’t had a real shower in two weeks. I use the gym showers when I can, but sometimes they’re locked. I wear the same clothes until Ms. [staff] gives me something from the closet” (Student) |

| Family Separation/Conflict | Student descriptions of being separated from family or fleeing family situations | Must reference family dynamics leading to housing instability | “My mom kicked me out after I told her I was gay. I’ve been staying with different friends, but I can’t stay anywhere more than a few days” (Student) |

| Resilience/Coping Strategies | Student descriptions of how they manage their situation or maintain school engagement despite challenges | Must identify active coping mechanisms or problem-solving | “I keep all my stuff in my backpack so I can go straight from school to wherever I’m staying. I do my homework in the library after school because it’s quiet there” (Student) |

Coding Process Notes

- Initial Coding: Open coding was conducted on Transcripts 1-3 to generate preliminary codes.

- Axial Coding: Codes were grouped into categories and relationships between codes were identified.

- Refinement: The codebook was iteratively refined as coding progressed through all 10 transcripts.

- Consistency Checks: After developing the final codebook, the researcher re-coded early transcripts to ensure consistent application.

- Memo Writing: Analytic memos were maintained throughout the coding process to document emerging themes and interpretations.

Inter-Coder Reliability

As a single coder, traditional inter-coder reliability metrics (e.g., Cohen’s Kappa) were not applicable. To ensure consistency and rigor, the following strategies were employed:

- Detailed operational definitions for each code with clear inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Multiple passes through the data (initial coding, refinement, consistency review)

- Systematic documentation of coding decisions through memoing

- Re-coding of early transcripts after codebook finalization to ensure uniform application

- Peer debriefing with research advisors to validate interpretations and coding decisions.

References