Abstract

Finding solutions to decarbonize aviation is one of the most pressing issues scientists currently face. Ammonia (NH3) has the potential to be a powerful tool towards solving this, given its lack of CO2 emissions when used in place of conventional jet fuel. This paper evaluates the effectiveness of ammonia with an additional assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuels, hydrogen fuel, and all-electric battery systems based on emissions, ease of integration, and technological limitations.Evaluation of these three other power sources serves to provide a baseline of comparison, as these three are some of the most well-studied options and ammonia is less well-studied. Data was analyzed from both experimental and theoretical research across multiple disciplines to synthesize our findings. We find that pure ammonia is not ideal for direct combustion due to extremely low flame speed and high ignition delay time, and using ammonia as a hydrogen carrier either through cracking or two-stage combustion is undesirable due to high costs of implementation. Ultimately, we recommend further experimental study on the use of ammonia as an additive to fuel blends containing kerosene and hydrogen, as this is the most promising solution under the parameters previously established.

Keywords: Ammonia, Sustainable Aviation Fuel, Hydrogen, Sustainable Aviation, All-Electric Aviation, Ammonia Combustion, Sustainability

Introduction

Climate change has become one of the largest threats currently facing humanity. As such, much time and effort has been devoted to discovering novel ways to decarbonize our modern society, including aviation1. We increasingly rely on aviation to connect with the world, and thus finding a solution to make aviation more sustainable is necessary to meet global climate goals1. Fortunately, many strides have already been made in terms of decreasing the energy intensity per passenger-mile of air travel through various improvements in technology, leading to the energy intensity of air travel decreasing by 77% per passenger in two decades. This great improvement cannot fully account for the increasing demand for air travel that we have especially seen in the past decade, as overall emissions from air travel still increased by 30% from 2013 to 2019 alone1. This indicates a troubling trend in the commercial aviation industry. While commercial air travel only accounted for 2.5% of global emissions in 2022, this is expected to rise to 11% in the next two decades if significant advances in technology are not made to account for rising demand2. It is important to understand that “emissions” encompasses not only the classic CO2, but also other carbon emissions like CO, and nitrous oxides (NOx). NOx emissions can decrease crop yields, cause diseases in humans, and exacerbate the Greenhouse Gas effect by creating ozone, thus perpetuating climate change3‘4. Thus, to prevent the environmental and economic disadvantages of rising emissions, it is clear that we must invest more into the discovery and development of novel sustainable aviation technologies.

To support this goal, the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which is a trade association representing a large portion of air travel, has set a goal for aviation emissions to reach 50% of their 2005 level by 20505. To achieve this, large investments into every sector of aviation will be required, but one of the most crucial is the fuel being used. While many alternatives such as Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAFs) and hydrogen (H2) have been considered and extensively studied, some recent research has begun to focus on ammonia (NH3) as a possible fuel option due to its possible fuel option due to its potentially low carbon emissions6. While SAFs and hydrogen have received substantial attention, ammonia is increasingly discussed due to its potential for carbon-free combustion and simpler airplane storage needs than hydrogen due to its higher freezing temperature and narrower flammability range7‘8. Furthermore, recent increased interest in ammonia may be explained by its production on an industrial scale for over a century as a fertilizer and refrigerant, making it easily accessible7. It also is roughly 17.8% of hydrogen by mass, meaning that many of hydrogen’s benefits could be accessed by utilizing the more convenient-to-store and -produce ammonia instead7.

This paper is a systematic review synthesizing data from papers published from 2017 to 2025 to provide a comparative analysis of alternative aviation fuels and evaluate ammonia’s technical viability. The primary limitation of this paper is that no experimental research facilities were accessible, so all findings are based on the experimental work of other researchers. The focus of this article is to review some processes related to fuel combustion (if applicable) and emissions (both carbon dioxide and NOx) with a specific focus on the alternative aviation fuels described previously (SAFs, hydrogen, and all-electric battery). No other paper reviewed by the authors included both an analysis of ammonia as well as analyses of SAFs, hydrogen, and all-electric battery systems, making this paper unique in its method of evaluating the effectiveness of ammonia. The intent of this analysis is to inform policymakers and researchers as to what some of the most promising lines of inquiry are in the field of sustainable aviation. We do not attempt to comprehensively review the entire field of alternative aviation fuel, as this is a continuously evolving area of research. The first section of this paper serves as an overview of ammonia and sustainable aviation goals. The next section outlines the methodology used in the creation of this paper, followed by an extensive comparison of all four considered fuels (SAFs, hydrogen, all-electric battery, and ammonia) concluding with an evaluation of current research prospects in the fourth section. Finally, the fifth section presents the conclusions of the paper along with research recommendations.

Methodology

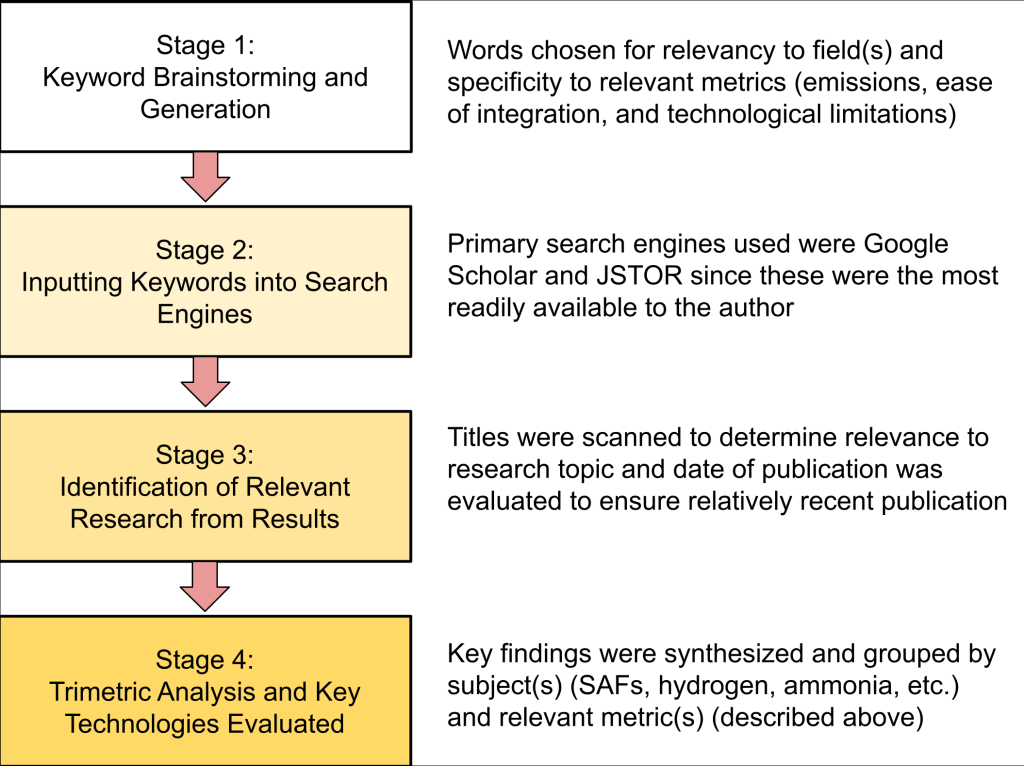

For this research paper, a systematic literature review was conducted to gain a holistic view of the most current work being done in the field of sustainable jet fuels, with the data collection period beginning in June 2025 and ending in September 2025. The general methodology followed is displayed in Figure 1. Search engines like Google Scholar and JSTOR were used to find papers, first using keywords like “sustainable aviation fuels”, “hydrogen as jet fuel”, and“alternative jet fuels” to build a comprehensive view of existing literature in the field. Google Scholar was generally preferred over JSTOR due to having more primary sources related to aviation than JSTOR when the same keywords were used. Then, keywords such as “ammonia as jet fuel” and “ammonia combustion properties” were used to gain a thorough understanding of the ammonia niche. Paper relevancy was assessed first by publishing date, as all papers older than 2023 were prioritized due to being the most up to date information, but some older sources were used when no more recent papers were available or when appropriate for the subject. Then, papers were thoroughly reviewed to ensure their findings were relevant to the topic of this paper by scanning the titles of papers, looking for connections to aviation. Source credibility was assessed by verifying publication integrity, with peer-reviewed academic journals, conference papers, and credible books being preferred above all else whenever possible. Finally, research design of the paper was considered, as experimental research was prioritized, but non-experimental papers were not always excluded. Numerical findings from research papers were extracted through thorough analysis of the papers and digital note-taking, making special note of papers that contained experimental findings about combustion properties.

Ultimately, 29 sources were determined to meet these requirements, most of which were research papers published in academic journals. All sources were evaluated to ensure no duplicates appeared. Any sources not coming from academic journals were instead from other reputable sources, such as government websites, and were largely not used for critical information. Main takeaways were synthesized and numerical findings were compared from differing sources to provide a basis for this paper’s discussion.

Results

Background

In order to fully understand ammonia as an alternative fuel, it is first important to understand other alternative fuel solutions that have been proposed. The aim of this section is to provide an overview of three of the main areas of research other than ammonia (Sustainable Aviation Fuels, hydrogen, and electric) and evaluate their advantages and disadvantages in relation to the metrics previously described (emissions, ease of integration, and technological limitations). Since this paper deals with the field of combustion, the following key properties are considered to compare combustion properties: 1) Flame speed, or the speed at which a flame propagates through a fluid. 2) Ignition Delay Time (IDT), or the time interval between the start of fuel injection and combustion. Both of these properties heavily influence engine design, particularly the fuel injection systems and combustor geometry. However, an important distinction between them is that while IDT decreases with temperature, flame speed increases8‘9. The typical parameter ranges within which aircraft engines operate is described in Table 1 below. While these conditions may not be the exact same as those later reported in the paper, later reported work still reflects the general trends for combustion of the discussed fuels (if relevant)10.

| Parameter | Typical Value(s) |

| Turbine Inlet Temperature | 1200 K – 2000 K |

| Turbine Inlet Pressure | 0.8 MPa – 4.5 MPa |

| Average Combustor Residence Time | 5 ms |

| Engine Exit Temperature | 200 K – 600 K |

Table 1 | Typical Aircraft Engine Parameter Ranges10

Sustainable Aviation Fuels

![]()

Sustainable Aviation Fuels encompass a wide range of fuels that are united by their production methods: they are typically made using waste products or other biological products such as leftover cooking oil or animal fats11‘12. This pivot away from using petroleum-based fuels leaves ample room for life-cycle carbon emission savings despite similar combustion to conventional jet fuel, with some finding an up to 90% reduction in overall emissions11. However, some other cradle to grave analyses, which includes all emissions involved in the transportation, production, and combustion of SAFs, have found emission reductions as low as 27%13. Nonetheless, some non-trivial emission reduction is essentially guaranteed for aircraft operating on SAFs. It is also crucial to note that SAFs are entirely drop-in compatible, since they are chemically engineered to have similar combustion properties (including flame speed and IDT) to conventional jet fuels11. Since SAFs have such similar combustion properties to conventional jet fuels, while their specific chemical compositions may vary, they will generally follow the general combustion equation of a hydrocarbon (shown above)11. However, this does again emphasize that this approach is not free from carbon emissions. This is a substantial advantage, as it means that essentially no engine redesigns are required to begin utilizing SAFs, minimizing downtime of aircraft and costs associated with creating new engines. Thus, SAFs work remarkably well within our current technological limitations.

However, the primary roadblock to widespread SAF adoption currently is high price, as SAFs can cost between 120-700% more than conventional jet fuels13.This would make a transition to utilizing SAFs incredibly taxing on commercial airlines financially, and the effect is only worsened by the lack of producer incentives currently in place13. Currently, SAF production is operating at only 3.5% of its total potential capacity, largely due to policies around the world not incentivizing growth within the market13. Thus, although SAFs offer substantial savings on emissions and work within our technological limitations, the financial cost of integrating them today is simply too high for airlines to cover, and substantial policy reform is needed to encourage growth to meet potentially rising demand.

Hydrogen

![]()

Hydrogen is widely renowned for having nearly zero carbon emissions in combustion, as its combustion equation only directly produces water (although some NOx emissions may result as an indirect byproduct of combustion)14. It is also roughly 3x as gravimetrically energy dense as conventional jet fuel, meaning that every 1 kg of hydrogen has 3x the energy as 1 kg of jet fuel15. Although direct life-cycle evaluations of hydrogen as a jet fuel are lacking, an analysis on the potential saving of hydrogen in automobiles found a potential 15-45% decrease in lifetime emissions16.This is not a direct parallel to emission savings that could be seen if implemented in aviation, as automobiles and aircraft operate under very different conditions, but it nonetheless indicates a relatively substantial decrease in emissions that would likely apply to aviation as well.

The fact that hydrogen does not guarantee a 100% decrease in emissions is in large part due to its production process. Although hydrogen can be produced sustainably through water electrolysis, a process in which electricity is used to split water into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2), only 0.1% of hydrogen is currently produced in this manner due to prohibitively high costs, and it relies on availability of green energy on the grid to be fully carbon neutral17. Carbon capture technology, which substantially reduces the emissions of production processes, are only being used in 0.6% of hydrogen production17. The other 99.3% of hydrogen being produced utilizes either oil or natural gases to fuel methane (CH4) reforming, which also releases methane as a waste product with up to 120x the heating power of CO24‘17. This has led to the production of hydrogen being responsible for roughly 2% of current annual CO2 emissions17.

Furthermore, hydrogen poses many challenges in terms of storage and usage on aircraft, since it is only 25% as volumetrically energy dense as conventional jet fuel and requires incredibly cold, high pressure storage tanks15. This means that space would have to be made on the aircraft for tanks that are much larger and require much more pressurization and cooling than the tanks currently in use, necessitating a fundamental redesign of the aircraft. Unfortunately, this redesign will also have to reach the engines, as hydrogen has nearly eight times the flame speed of and much lower IDT than conventional jet fuel, meaning that it is not drop-in compatible18‘19. Much research has been dedicated to solving for these differences, though, and there are some prototype designs that could theoretically utilize hydrogen15.

In sum, in terms of emissions, unsustainable hydrogen production makes hydrogen undesirable. In terms of ease of integration, more work is needed in terms of redesigning all aircraft fundamentally and getting hydrogen to every airport, making hydrogen undesirable. Finally, in terms of technological limitations, the challenges posed by hydrogen storage currently make widespread usage unlikely.

All-Electric

The field of electrically propelled aircraft encompasses not only aircraft relying entirely on electricity for propulsion (all-electric), but also hybrid aircraft that rely both on conventional jet fuel and batteries20. This section primarily focuses on all-electric aircraft, since these present the most exciting change in comparison to today’s aircraft. Such an aircraft would have very minimal if any emissions when implemented in the aircraft, with the only life-cycle emissions coming from battery production-related emissions. These emissions are still relatively low, though, as one analysis found that business carriers could see a 93% reduction in emissions if they were made all-electric20. This is the most dramatic emission reduction discussed thus far, but unfortunately, all-electric aircraft fall short in other ways.

All-electric aircraft would rely on batteries storing huge amounts of energy to maintain power during the flight, but current battery technology is simply not advanced enough to accommodate this. Even the most efficient batteries today would have to be prohibitively large and heavy in order to store enough energy for a single flight, with weight increasing with the length of the flight21. This would cause all-electric aircraft to have slower flight times and shorter ranges than today’s aircraft, hugely hampering their potential to be a full solution as not all routes could be served2‘20‘21. One analysis found that even in an optimistic case where it would be possible to produce all-electric aircraft capable of traveling up to 500 km per flight, this would only affect 5% of all commercial aircraft energy usage21. Thus, 95% of the energy used by commercial aviation would still be contributing to climate change, and the previously stated emission reductions are severely hampered in scale. Furthermore, the colossal size of batteries needed to support commercial aviation would also cause 92% of commercially used aircraft to be unable to take off due to excessive battery weight22. All-electric propulsion is also entirely not drop-in compatible, as it would require a fundamental redesign of the aircraft to accommodate the new batteries21. This means that no currently used aircraft could continue to be used without substantial modification, incurring extra downtime of aircraft and costs related to heavily modifying and redesigning aircraft.

In all, while having the potential for incredible emission reductions, all-electric propulsion fundamentally fails to make a significant impact due to its cumbersome implementation and need for technology that simply does not exist yet. Until serious advances in battery efficiency are achieved, further research in other fields or in hybrid-electric models is recommended.

Ammonia

![]()

The balanced equation for the combustion of ammonia and air (shown above) shares many features with that of hydrogen and air, including a lack of carbon outputs. However, it notably includes some N2 as an output, which sets it apart from hydrogen and introduces new considerations for combustion and emissions which will be further discussed in this section. While still requiring more complex storage than conventional fuel, one of the primary advantages of ammonia is that it has much less stringent storage requirements than hydrogen. Ammonia has a boiling temperature of -33 ℃ at 1 atm, compared to hydrogen’s -253 ℃, meaning that it would require less investment into cryogenic tanks7. This makes ammonia a seemingly ideal substitute, as it significantly mitigates one of the primary design challenges associated with use of hydrogen. It is still somewhat more complex to store than conventional jet fuels, though, which are liquid at room temperature and typically have freezing temperatures around -50 ℃, with some fluctuation depending on exact fuel composition23.Thus, much recent research in the field of sustainable aviation has focused on the utilization of ammonia as a jet fuel through several different methods. This section discusses and evaluates the use of ammonia as jet fuel (pure ammonia use), using ammonia as a hydrogen carrier (typically through cracking or complex combustion), and the use of ammonia as an additive to other fuel types.

Pure Ammonia Use

Using ammonia on its own may seem like the most simple solution, as it would ideally serve as a direct replacement for jet fuel while circumventing the challenges associated with hydrogen. Unfortunately, ammonia causes many new issues to arise that hydrogen does not suffer from. While hydrogen has a relatively high flame speed and low IDT, ammonia has the opposite problem of having a low flame speed and high IDT18‘19‘24‘25. Table 2 displays the flame speed of several mixtures, notably showing that by replacing just half of a hydrogen mixture with ammonia, the flame speed is decreased almost sevenfold19. The flame speed for an ammonia/air mixture, though, was not determined at these exact conditions by any work reviewed for this paper. However, at P = 5 bar, T = 500 K, and Φ = 1, the flame speed of ammonia-air has been experimentally determined to be roughly 0.11 m/s, far below any other flame speed presented despite being at a higher pressure26. Clees et al. attempted to validate some of the foremost models for predicting IDT through shock tube experiments and OH* and OH measurements, as the presence of these indicate ignition in the fuel, finding that most models are unable to accurately predict the IDT of ammonia at all temperatures27.

| Type of Fuel | Flame Speed (m/s) |

| 50% Ammonia, 50% Hydrogen | 1.4 |

| Hydrogen | 7.7 |

| Jet fuel (Jet-A2) | 0.99 |

Table 2 | Comparison of Flame Speeds at P = 2 bar, T = 600 K, and Φ = 119.

This essentially means that while hydrogen presents challenges due to being too readily combustible, ammonia is instead too difficult to combust. The primary consequence of this is that pure ammonia mixtures would be incompatible with current aviation engines, as the combustor geometry is simply not suited for efficiently combusting fuels with these properties due to combustion possibly occurring too late8. Furthermore, analyses have even found potential for ammonia in current engines not fully combusting before leaving the engine due to these differences in combustion properties, thereby releasing more unburnt ammonia, NOx, and other harmful emissions into the environment25. Therefore, due to the massive engine redesign that would be required and potential for harmful emissions, using pure ammonia on its own as a fuel is not recommended.

Alternative Ammonia Combustion

The potential of ammonia due to its previously discussed advantages over hydrogen has spurred further research into novel uses of ammonia. Specifically, some research groups have examined the possibility of using ammonia as a hydrogen carrier in order to avoid the downsides of ammonia while still enjoying its benefits. One such approach is called ammonia cracking, which involves the splitting of ammonia into nitrogen (N2) and hydrogen prior to reaching the combustor28‘29. This approach has the added benefit of utilizing waste heat from the engine to fuel the cracking process, thereby increasing overall system efficiency28. Furthermore, due to the increased presence of stable nitrogen and hydrogen, which are much less likely to form NOx emissions than ammonia on its own, NOx emissions have been predicted to decrease in planes using this approach29. Implementation of this design would require the addition of a cracking chamber to each engine, as well as redesigns to accommodate the combustion of hydrogen, but hypothetical models have been made that fit these requirements29. The largest barriers this approach faces are the inherent inconvenience of having to entirely redesign all existing engines, the added weight of cracking systems, and the novelty of this idea, as it has never been implemented on a commercial scale before. Thus, significant investment into experimental research is recommended before implementation of this approach.

A second approach being considered is the splitting of ammonia into hydrogen and nitrogen through two-stage combustion. This means that there will first be a fuel rich zone, with high concentration of ammonia to begin conversion to hydrogen, followed by a fuel lean zone, with a high concentration of air to complete conversion, as seen in Figure 228.

Again, a main advantage of this approach is a significant decrease in NOx emissions at aircraft engine conditions due to increased N2 presence28. However, most previous examples of two-stage ammonia emissions incorporate the use of a pilot or start-up fuel to compensate for ammonia’s unfavorable combustion properties, such as methane28‘30. This once again reintroduces carbon into the combustor, although generally additions of CH4 have been shown to reduce emissions on net because of increased combustion efficiency30. While this approach would not require the addition of a whole new cracking chamber, it would still require significant combustor redesign and fuel mixing techniques that have yet to be achieved on a practical level in the aviation industry. Furthermore, recently published studies have found that while novel combustion techniques like multi-stage combustion do generally lead to reductions in NOx emissions, the most effective approach to mitigating NOx emissions is to have the equivalence ratio be greater than 1, which has not yet been tested for either cracking or multistage combustion31. Thus, this approach is not yet feasible due to a lack of experimental research.

Ammonia as an Additive

While both of the previous techniques are limited by their reliance on unproven engine redesigns, the most promising line of ammonia research in terms of near-term feasibility currently ongoing relies on assuming none of these major changes. Specifically, Alabaş suggests using ammonia as an additive, either to hydrogen, kerosene, or both25. The central study pushing forward this alternative was conducted using over 1600 iterations in ANSYS Fluent using the SIMPLE algorithm25. Specific model parameters can be seen in Table 3 below. Authors modeled a GTM-120 mini gas turbine engine, which is a typical research tool for studying the behavior of airplane engines25. Thus, all results are assuming no or minimal changes to current engine designs.

| Category | Parameter | Value |

| Simulation Models | Combustion model | Non-premixed with compressible effect |

| NOx model | Thermal NOx, N2O intermediate, fuel NOx, prompt NOx | |

| Radiation model | Discrete ordinates | |

| Turbulence | Standard k-ε with scalable wall function | |

| Fuel injection | Discrete phase method with droplet | |

| Geometry | Type | Full body |

| Material | Inconel – 718 | |

| Length | 125 mm | |

| Diameter | 107 mm |

Table 3 | Model Parameters Used to Evaluate Ammonia as an Additive25

Several mixtures were tested with concentrations of ammonia ranging from 5% to 45%, kerosene limited to 50%, and hydrogen making up the difference25. It is important to note that while the addition of kerosene generally improved combustion efficiency, it had the significant tradeoff of introducing carbon to the mixture, thus producing carbon emissions25. In terms of ammonia, the study found that while NOx emissions peaked at 5% ammonia, they then decreased rather significantly after that point as the concentration of ammonia increased, likely due to decreased flame temperatures25. Ultimately, the ideal mixture the study recommends is 50% kerosene, 45% ammonia, and 5% hydrogen because of its lowered NOx emissions and overall burn efficiency25. This increase in burn efficiency is reflected in a decrease in CO emissions, which result as a byproduct of incomplete combustion, and the massive difference in this can be seen in Table 425.

| Mixture | NOx (ppm) | CO (ppm) |

| High Ammonia (45% NH3/50% kerosene /5%H2) | 14.26 | 0.0158 |

| Low Ammonia (5%NH3/50% kerosene /45%H2) | 344.5 | 0.74 |

Table 4 | Ammonia Mixture Emissions Comparison25.

While this is not an ideal solution due to the inclusion of kerosene, a hydrocarbon, this still provides greatly lowered emissions compared to conventional jet fuel while still preserving drop-in compatibility25. Thus, because of the significant technological and logistical barriers that come with implementing all other proposed solutions, using ammonia as an additive is likely the most technologically feasible solution at this time. While notable emissions reductions are still achieved, the largest barrier to decarbonizing aviation is circumvented: difficulties within implementation. However, this study did not take into consideration the storage of the fuel mixture, which is a substantial oversight since (as previously discussed) storing both ammonia and hydrogen comes with unique challenges that could potentially complicate implementation. There is no explanation of how the blend will be kept at a temperature and/or pressure suitable for all involved fuels, which is alarming due to the vastly different storage requirements they have (see section Ammonia). There is also a notable lack of experimental confirmation of the simulation’s findings. Thus, while this approach is by far the most promising discussed thus far, experimental research is strongly recommended to further validate the authors’ claims.

Discussion

As the commercial aviation industry continues to grow across the world, the need to create low-carbon propulsion becomes increasingly apparent. While solutions such as all-electric, hydrogen, pure SAFs, or even pure ammonia may not yet be feasible primarily due to technological limitations, ammonia can still serve as a valuable stepping stone. See Table 5 for an overview of the conclusions drawn regarding all considered power sources. The use of ammonia as an additive to other fuels is an incredibly exciting idea, and while it may not be an entirely carbon-free solution, it will still decrease emissions if implemented. It also benefits from requiring minimal if any engine redesigns, as previously described, making it more simple to implement. This can be used as a transition period from our current lack of adequate solutions for carbon-free fuels like hydrogen. Thus, more research is strongly recommended within this area to experimentally validate the findings of the study discussed and to continue pushing for more sustainable aviation.

| Power Source Type | GHG Emissions (NOx and CO2) | Ease of Integration | Technological Limitations |

| SAFs | Similar to Conventional | Very easy | Few |

| Hydrogen | Low/No CO2, Some NOx | Very complex | Many |

| All-Electric | Low/No Emissions | Very complex | Many |

| Pure Ammonia | Low/No CO2, Significant NOx | Very complex | Many |

| Ammonia as an Additive | Some CO2 and NOx, but Less than Conventional | Very Easy | Few |

Table 5 | Metric Evaluation by Power Source

Experimentalist researchers ought to use the models previously described to guide their experiments in order to validate the findings these previous researchers have presented, directly furthering the line of inquiry into the use of ammonia as an additive. One recommended approach is testing different combinations of kerosene, hydrogen, and ammonia at conditions similar to an airplane engine, as previously described. Both the aviation industry and policymakers are strongly recommended to support the exploration and development of this technology through financial investments and policy support. It is also important to consider that all conclusions drawn and recommendations made in this paper are based on a literature review which, while as thorough as possible, does not preclude the existence of contradicting studies or information. The findings discussed above should be interpreted as a preliminary step toward creating a more sustainable future for aviation, whether or not ammonia is involved.

References

- J. Overton. The growth in greenhouse gas emissions from commercial aviation. www.eesi.org/papers/view/fact-sheet-the-growth-in-greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-commercial-aviation (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- B.A. Adu-Gyamfi, C. Good. Electric aviation: a review of concepts and enabling technologies. Transportation Engineering. 9, 100134 (2022). [↩] [↩]

- Queensland Government. Nitrogen oxides | Air pollutants. www.qld.gov.au/environment/management/monitoring/air/air-pollution/pollutants/nitrogen-oxides (2013). [↩]

- K. Hunt. Assessing hydrogen emissions across the entire life cycle. www.catf.us/2022/10/hydrogen-lca-emissions-across-life-cycle/ (2022). [↩] [↩]

- IATA. Resolution on the industry’s commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. https://www.iata.org/contentassets/d13875e9ed784f75bac90f000760e998/iata-agm-resolution-on-net-zero-carbon-emissions.pdf (2021). [↩]

- A. Valera-Medina, H. Xiao, M. Owen-Jones, W.I.F David, P.J. Bowen. Ammonia for power. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 69, 63–102 (2018). [↩]

- H. Kobayashi, A. Hayakawa, K.D.K.A. Somarathne, E.C. Okafor. Science and technology of ammonia combustion. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 37, 109–133 (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- S. Clees, T. Rault, M. Figueroa-Labastida, S. Barnes, A. Ferris, R. Hanson. A shock tube and laser absorption study of NH3 oxidation. Proceedings of the 13th U.S. National Combustion Meeting (2023). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- R. Amirante, E. Distaso, P. Tamburrano, R.D. Reitz. Laminar Flame Speed Correlations for Methane, Ethane, Propane and Their Mixtures, and Natural Gas and Gasoline for Spark-Ignition Engine Simulations. International Journal of Engine Research. 18, 951–970 (2017). [↩]

- J. E. Penner, D. H. Lister, D. J. Griggs, D. J. Dokken, M. McFarland. Aviation and the global atmosphere (1999). [↩] [↩]

- M. Prussi, U. Lee, M. Wang, R. Malina, H. Valin, F. Taheripour, C. Velarde, M.D. Staples, L. Lonza, J.I. Hileman. CORSIA: The first internationally adopted approach to calculate life-cycle GHG emissions for aviation fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 150, 111398 (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Alternative fuels data center: Sustainable Aviation Fuel. afdc.energy.gov/fuels/sustainable-aviation-fuel. [↩]

- M. J. Watson, . P.G. Machado, A.V. da Silva , Y. Saltar, C.O. Ribeiro, C.A.O. Nascimento, A.W. Dowling. Sustainable aviation fuel technologies, costs, emissions, policies, and markets: a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 449, 141472 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- T. Yusaf, A.S. Faisal Mahamude, K. Kadirgama, D. Ramasamy, K. Farhana, H.A. Dhahad, A.R. Abu Talib. Sustainable hydrogen energy in aviation – a narrative review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 52, 1026-1045 (2023). [↩]

- T. Yusaf, A.S. Faisal Mahamude, K. Kadirgama, D. Ramasamy, K. Farhana, H.A. Dhahad, A.R. Abu Talib. Sustainable hydrogen energy in aviation – a narrative review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 52, 1026-1045 (2023). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- X. Liu, K. Reddi, A. Elgowainy, H. Lohse-Busch, M. Wang, N. Rustagi. Comparison of well-to-wheels energy use and emissions of a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle relative to a conventional gasoline-powered internal combustion engine vehicle. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 45, 972–983 (2020). [↩]

- G. Wakim. Hydrogen for decarbonization: a realistic assessment. www.catf.us/resource/hydrogen-decarbonization-realistic-assessment/ (2023). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- G.A. Richards, M.M. McMillian, R.S. Gemmen, W.A. Rogers, S.R. Cully. Issues for low-emission, fuel-flexible power systems. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 27, 141–169 (2001). [↩] [↩]

- A. Abbass. Comparative analysis of hydrogen-ammonia blends and jet fuel in gas turbine combustors using well-stirred reactor model. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 73, 106450 (2025). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- S. Baumeister, T.K. Simić, E. Ganić. Emissions reduction potentials in business aviation with electric aircraft. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 136, 104415 (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- I. Staack, A. Sobron, P. Krus. The potential of full-electric aircraft for civil transportation: from the Breguet range equation to operational aspects. CEAS Aeronautical Journal. 12, 803–819 (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A.H. Epstein, S.M. O’Flarity. Considerations for Reducing Aviation’s CO2 with Aircraft Electric Propulsion. Journal of Propulsion and Power. 35, 572-582 (2019). [↩]

- S. Zabarnick, N. Widmor. Studies of Jet Fuel Freezing by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Energy & Fuels. Vol. 15, pg. 1447-1453 (2001). [↩]

- S. Clees, T.M. Rault, L.T. Zaczek, R.K. Hanson. Simultaneous OH and OH∗ measurements during NH3 oxidation in a shock tube. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 40, 105286 (2024). [↩]

- A. Hüsamettin Alperen. CFD study of jet fuel with ammonia – hydrogen mixtures in a jet engine: emissions and combustion characteristics analysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 142, 140–150 (2025). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- J. Goodman, A. Dhankhar, A. Date, P. Lappas. Ammonia–air laminar flame speeds from ambient to IC engine conditions: A review. Fuel. Vol. 383, 133769 (2025). [↩]

- S. Clees, T.M. Rault, L.T. Zaczek, R.K. Hanson. Simultaneous OH and OH∗ measurements during NH3 oxidation in a shock tube. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 40, 105286 (2024). [↩]

- Ammonia Energy Association. Ammonia-fueled gas turbines: a technology and deployment update. ammoniaenergy.org/articles/ammonia-fueled-gas-turbines-a-technology-and-deployment-update/ (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- M Otto, L. Vesely, J. Kapat, M. Stoia, N.D. Applegate, G. Natsui. Ammonia as an aircraft fuel: a critical assessment from airport to wake. ASME Open Journal of Engineering. 2, 021033 (2023). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- E.C. Okafor, O. Kurata , H. Yamashita, T. Inoue, T. Tsujimura, N. Iki, A. Hayakawa, S. Ito, M. Uchida, H. Kobayashi. Liquid ammonia spray combustion in two-stage micro gas turbine combustors at 0.25 MPa; Relevance of combustion enhancement to flame stability and NOx control. Applications in Energy and Combustion Science. 7, 100038 (2021). [↩] [↩]

- H. A. Yousefi Rizi, D. Shin. Development of Ammonia Combustion Technology for NOx Reduction. Energies. Vol. 18, pg. 1248 (2025). [↩]