Abstract

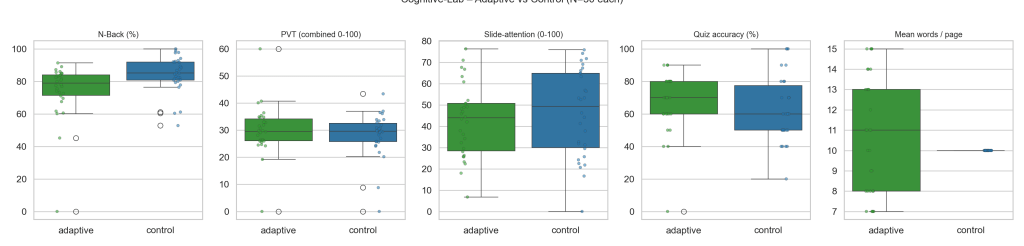

The present study examines the educational advantage provided by adaptive learning interfaces which modulate lesson size with respect to the cognitive profile of the learner; these empirical findings are contextualized in Cognitive Load Theory and afford implications for the use thereof in instructional design, though with certain limitations. We evaluated whether dynamically sizing lesson “chunks” to each learner’s attentional capacity improves vocabulary learning. Sixty adults were randomly assigned to an adaptive flash-card tutor or a fixed-pace version. The hypothesis being that those instructed through an adaptive tutor, stylized according to their cognitive profile, would demonstrate greater recall on post-study examinations than their fixed-pace peers. Before study, all completed a 2-Back task, a psychomotor-vigilance test, and a slide-reading attention probe; the adaptive system used the attention score to set lesson size (5–12 words), while the control group received uniform 10-word blocks. Study time was identical across groups. Immediate recall on a 10-item quiz was higher for adaptive learners (78 % ± 15) than controls (63 % ± 20), a large effect (t(58)=3.2, p < .005, d = 0.84), with less score dispersion. Because baseline cognitive measures did not differ, the gain is attributed to reduced extraneous load from personalized chunking. These results show that even simple, attention-based adaptation can boost retention by about one quarter, supporting Cognitive Load Theory and highlighting a scalable route to more efficient digital instruction.

Keywords: Adaptive learning, Cognitive Load Theory, attention-based personalization

Introduction

Poorly designed instructional interfaces can impose excessive strain on a learner’s cognitive processing, reducing the efficiency of learning. In cognitive psychology terms, working memory – the mental workspace for holding and manipulating information – has a limited capacity at any given moment1. If instructional materials present more information or require more simultaneous processing than this limited capacity can handle, the learner’s cognitive resources become overtaxed and learning performance suffers2. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), first proposed by Sweller3, categorizes the total mental load during learning into intrinsic, germane, and extraneous load3. Intrinsic load is determined by the inherent complexity of the material, germane load is the mental effort that directly contributes to learning (e.g. forming new schemas), and extraneous load refers to the cognitive effort wasted on irrelevant or inefficient aspects of instruction4. According to CLT, extraneous cognitive load – often caused by suboptimal design or presentation of information – should be minimized so that more of the learner’s finite mental resources can be devoted to germane processing (i.e. understanding and retaining the content).

In practical terms, when a learning interface is maladaptive or insensitive to an individual’s cognitive capacity, it may overwhelm learners with more information or distractions than they can manage, thereby diverting their attention from the core learning task. This can inhibit learning for individuals with lower cognitive capacity (by overloading them) and even for those with higher capacity (by introducing unnecessary complexity that occupies working memory without adding educational value). One promising solution is to design adaptive learning systems that tailor the amount and pace of information delivery to the learner’s cognitive profile. By dynamically adjusting instructional “chunk size” or difficulty based on the user’s working memory capacity, attention span, or expertise, an adaptive interface can avoid both overload and under-stimulation. Prior research in CLT supports the idea that instructional efficacy improves when the content difficulty or volume is aligned with the learner’s ability – for example, materials that are effective for novices may become ineffective or even counterproductive for more expert learners, a phenomenon known as the expertise reversal effect5.

To prevent such mismatches, individualized pacing or content chunking has been recommended: Kalyuga et al.6 showed that designing instructional presentations with respect to learners’ prior knowledge significantly enhances learning efficiency. In general, adaptive instruction aims to keep each learner’s cognitive load within an optimal range – challenging enough to engage germane resources but not so difficult as to induce cognitive overload7. If extraneous load is kept low and task demands are calibrated to the learner, more cognitive capacity is available for authentic learning processes. The present study builds on these principles by introducing a simple adaptive mechanism in a digital vocabulary tutor: the system measures each learner’s attention and working memory capacity, then adjusts the lesson chunk size (number of new words introduced at once) to suit that individual. We hypothesize that this adaptation will reduce extraneous load for learners with lower cognitive endurance (by preventing information overload) while still efficiently utilizing the capacity of those with higher endurance – ultimately improving overall learning outcomes.

By empirically evaluating this adaptive flashcard system against fixed-pace control, we aim to extend cognitive load theory into practice and demonstrate a scalable, attention-based personalization that measurably boosts learning. The hypothesis of the present paper, then, is that learners taught through an adaptive medium will exhibit greater mastery of the material than would their fixed-paced counterparts. In consideration of Cognitive Load Theory, the hypothesis is logically found, and the experiment herein performed both operationalizes and tests this hypothesis. The significance of this research lies in its potential to validate a practical method for increasing learning efficiency: if even a relatively simple adaptive adjustment (grounded in cognitive capacity metrics) can yield a substantial improvement in retention, it would provide preliminary findings promoting the adoption of adaptive interfaces in education and fill a gap in the literature, as few such empirical studies, like the present one, have directly examined cognitive-load-based adaptation in digital learning environments. It must be emphasized, though, that findings, though promising, cannot fully affirm the value of adaptive learning mediums until further findings buttress ours. To that end, we hope, at the minimum, to have provided a firm baseline for the investigation into the instructional value of adaptive elements in learning interfaces.

Methodology

Participants and Design

We conducted a between-subjects experiment with 60 adults (ages 18–35) residing in the United States, randomly assigned to either an adaptive-learning group (n = 30) or a control group (n = 30). This was done exclusively through a computerized-program that first randomly assorted participants into a list compiled from 1-60 and then assigned even-numbered participants into the control group and odd-numbered participants into the experimental group, respectively. All other instances of randomization, such as when assigning vocabulary words, were performed through a similar computerized randomizer. This applied for all other instances where randomization is used in the present study. Participants were recruited through a website (positly.com) dedicated to connecting researchers and willing survey participants. In registering for this platform, participants acknowledged that their performance might be collected and analyzed for scientific inquiry. The privacy of the users was maintained in order to ensure confidentiality between researchers and participants. The present study was executed in a manner consistent with all ethical guidelines with respect to cognitive research. Participants were aware that their data was to be collected and processed for scientific purpose. All guidelines concerning ethics, and those that have precedent in cognitive research (and science as a whole) have been duly respected. One must consider that the people engaging with these platforms may not reflect the general populace of the United States and this may have some implications for generalizability. Compensation was provided accordingly as was commensurate with the tasks completed. It should be noted, however, that although compensation was provided, it was a modest sum (avg. $11.06 per hour) unlikely to have influenced performance appreciably, though we must always be wary of it as a potential confounding variable. Due to the inherently anonymous nature of the medium utilized, specific demographics were not collected; this could be another limitation of generalizability. All participants undertook a pre-test cognitive assessment, followed by a vocabulary learning session and a retention quiz. The control group used a fixed-pace learning program, whereas the experimental group used a self-adaptive tool that adjusted lesson length to each learner’s cognitive profile.

Cognitive Assessment Battery (Pre-test)

To gauge each participant’s cognitive capacities and tailor the adaptive system, we administered three standardized cognitive tasks measuring working memory, attention, and vigilance. On-screen tutorials preceded each task to ensure participants understood the instructions. The battery was completed in one sitting to maintain consistency in mental state. The tasks were as follows:

2-Back Working Memory Task

Participants performed a classic n-back test of working memory with n = 2. A sequence of 30 uppercase letters was presented one by one (1.5 seconds per letter). Participants had to press the space bar whenever the current letter matched the letter shown two positions earlier. The first two letters were seeds with no response expected; thereafter 35% of the letters were programmed to be matches (the letter repeats from two trials back) while the rest were non-matches (a new random letter different from the 2-back letter). This sequence was generated on the fly ensuring non-match letters never accidentally equaled the 2-back letter (preventing unintended matches). During a brief tutorial round, the interface displayed the previous letters on screen and gave feedback for practice (e.g. “Press Space now!” if a tutorial letter was a match two-back). In the actual test, no such clues were given and letters flashed rapidly. Performancemetrics collected from this task included the number of correct detections (“hits”), missed detections (“misses” when a match occurred but the user did not press), and false attempts (presses on non-matching letters). The present study employed the n-back test partially due to its long-standing precedence in cognitive science as a reliable means of operationalizing one’s cognitive facilities and partially due to the ease of which it may be administered through an online medium. Given how firmly established a metric the n-back test is in cognitive science, and the ease through which it quantitatively describes one’s working memory, it became a convenient and accurate choice for the present study. The metrics below manipulate the only raw data collected into data ready for interpretation. Working-memory performance is quantified with an overall 2-back accuracy score:

where Hits = correct presses on true 2-back matches, Misses = no press on a true match, and False Alarms = presses on non-matches. This 2-back accuracy served as an indicator of working memory and attention under a memory load.

Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT)

We measured sustained attention and alertness using a 20-trial PVT. In each trial, the participant waits for a random interval between 2–7 seconds while watching a grey circle on the screen. After this random fore-period, the circle turns green, upon which the participant must immediately press the space bar or click to register a response. If the participant reacts too early (before the stimulus appears), it counts as a false start, and the trial is reset with a new waiting interval. If the participant reacts after the stimulus, the reaction time (RT) in milliseconds is recorded for that trial. The green circle remains for only a brief time and the RT is displayed for 0.6 seconds as feedback after each response. Any reaction time exceeding 500 ms was logged as a lapse in attention (a standard threshold in PVT indicating a momentary failure of vigilance). The PVT thus provided multiple metrics: the mean and median reaction times across the 20 trials, the total number of lapses (RT > 500 ms), and the count of false starts. A composite vigilance index combines speed and lapse frequency:

Here RT means reaction time (ms); L means lapses (trials with RT > 500 ms); N=20 means total trials; w=0.7 weights the lapse penalty. Higher scores indicate faster, steadier alertness.These measures reflect each participant’s baseline alertness and impulsivity control. A lower mean RT and fewer lapses indicate higher vigilance capacity.

Slide-Show Attention Task

We assessed sustained attention and reading diligence with a self-paced slide presentation. Participants read 29 short slides on cognitive topics and advanced with a “Next” button; every dwell time tit_iti (ms) was logged, with a 1-s minimum enforced to curb accidental clicks. At the end, the system collapsed these timings into a Slide-attention score (0–100) with one compact rule:

where S=d/29 is the sustained-focus fraction; d is the first slide whose dwell time falls below 60 % of the personal baseline (mean of the first three slides), or 29 if no drop occurs. CV=σ/μ is the coefficient of variation of dwell times up to slide d (a lower CV means steadier reading). [⋅]+=max (0,⋅) prevents negative consistency scores. P is a spam-click penalty based on the share q of slides skimmed in < 1 s: P=1 if q=0; P=0.5 if 0<q≤0.30; P=0.2 if q>0.30.

Thus diligent readers who maintain their pace and consistency, without rapid skipping, score near 100, whereas early focus loss, erratic pacing, or slide-skipping sharply lowers the score. This Slide-attention score feeds directly into the adaptive lesson-sizing algorithm described below, serving as the primary indicator of each learner’s capacity to sustain attention on educational content.

Adaptive vs. Fixed Learning Session

After the cognitive assessments, participants immediately proceeded to a vocabulary learning session for Toki Pona, an artificial language. The session was delivered via a custom web-based flashcard application. The content included a bank of Toki Pona words along with their phonetic pronunciations and English meanings. Both groups were exposed to the same total set of words; the key difference was how the session was structured:

Control Group (Fixed Pace)

Participants in the control condition experienced a fixed lesson structure. The word list was divided into a predetermined number of flashcard lessons of equal length, imposing the same cognitive load on all learners. We set a fixed block size (e.g. 10 words per lesson for all participants) to simulate a non-adaptive, one-size-fits-all approach. Participants reviewed each set of 10 flashcards, flipping one card at a time to see the word’s meaning. After completing a lesson, they had a mandatory 10-second break screen before moving to the next set of cards.

Experimental Group (Adaptive Pace)

Participants in the adaptive-learning group experienced a self-adaptive flash-card system that personalised lesson pacing to each learner’s cognitive profile. The system blended the three pre-test scores—Slide-attention A, 2-Back accuracy W, and PVT vigilance V (all on 0–100 scales)—into a single difficulty index:

Lesson size L (words per flash-card “page”) was then set by a linear rule:

so the smallest chunk is 7 words and the largest is 15.

The composite index d=0.70A+0.20W+0.10Vwas specified a priori to reflect Cognitive Load Theory’s emphasis on sustained attention as the primary determinant of tolerance for presentation rate and chunk size, with working memory and vigilance acting as secondary modulators. We normalized all three measures to the same 0–100 scale before weighting so coefficients represent relative contribution. The 0.70 weight ensures that Slide-attention is the dominant driver of lesson size, while 0.20 for 2-Back accuracy and 0.10 for PVT vigilance allow modest, directional adjustments when working memory or vigilance are unusually high or low.

For example, A learner with d=40 (e.g., A=50, W=30, V=45) would receive L=10 words per page, whereas someone with d=90 (e.g., A=85, W=95, V=80) would receive L=14 words. This keeps Slide-attention as the dominant driver (70 % weight) while still soft-tuning lesson size for unusually high or low working-memory and vigilance scores, thereby reducing extraneous cognitive load for each individual. Participants reviewed the flashcards similarly to the control group (flipping cards to see translations, with interactive 3D card effects), with the same 10-second enforced breaks between lessons. However, because the lesson size was adjusted, those with shorter lessons simply had more but smaller rounds, whereas those with longer lessons had fewer rounds. The total study time was kept roughly equivalent for all participants – the adaptation was in grouping of content, not overall exposure time.

Vocabulary Retention Quiz

Immediately after completing the learning session, participants took a quiz to assess vocabulary retention. The quiz consisted of 10 multiple-choice questions drawn randomly from the Toki Pona words covered. Each question presented one Toki Pona word (written in the Toki Pona script or transliteration) as the prompt, and four English words as options (one correct meaning and three distractors). This format tests the ability to recognize and recall the meaning of each foreign word. Questions were answered one at a time; once the participant selected an answer, the interface locked in the response and provided instant feedback by highlighting the choice in green (correct) or red (incorrect). Each participant’s quiz accuracy (percentage of correct answers out of 10) was recorded as the primary outcome measure.

Statistics

Baseline comparability for the three pre-test measures (2-Back accuracy, PVT composite, Slide-attention) was examined with Welch’s independent-samples t-tests. To control family-wise error across these baseline tests, p-values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni procedure (m = 3). Adjusted p-values (p_Holm) are reported. Because 2-Back accuracy remained imbalanced after correction, the primary outcome analysis included 2-Back as a covariate (ANCOVA: group as factor, 2-Back as covariate).

Results

Baseline Cognitive Measures. After Holm–Bonferroni correction across the three tests, groups differed on 2-Back accuracy but not on PVT or Slide-attention. 2-Back: control 84.48 ± 11.09 vs adaptive 74.38 ± 17.36, Welch t(49.29) = 2.68, p = 0.010, p_Holm = 0.030. PVT: 47.26 ± 13.61 vs 50.08 ± 15.42, t(57.11) = −0.75, p = 0.456, p_Holm = 0.891. Slide-attention: 46.24 ± 20.65 vs 42.48 ± 17.03, t(55.97) = 0.77, p = 0.445, p_Holm = 0.891. Accordingly, the primary analysis controlled for 2-Back accuracy.

| Control | Adaptive | |

|---|---|---|

| nBack | 84.5 | 74.4 |

| PVT | 47.3 | 50.1 |

| Slide | 46.2 | 42.5 |

| Mean words/page | 10.0 | 10.8 |

| Quiz % correct | 63.0 | 67.7 |

Baseline Cognitive Measures

We first examined the pre-test cognitive measures to ensure the two groups were comparable prior to the learning intervention. As shown in Figure 1 (left three panels), the adaptive and control groups had no significant differences in their cognitive assessment results. The 2-Back working memory task accuracy was similar between groups (median values approximately 75–80% for adaptive vs. 85% for control, but with overlapping interquartile ranges). A two-sample t-test on 2-Back accuracy yielded no statistically significant difference (p > 0.1), confirming that both groups had equivalent working memory performance on average. The PVT vigilance results were likewise comparable: both groups exhibited a wide range of reaction times and lapses, but their overall vigilance scores (a composite scaled 0–100 combining reaction speed and lapses) did not significantly differ. Median PVT scores hovered around the mid-40s out of 100 for both conditions, with no statistical difference (p > 0.5). Similarly, sustained attention capacity as measured by the slideshow Attention Score showed no significant group difference (p > 0.2). The control group’s median attention score was around 60/100, slightly higher than the adaptive group’s median ~50, but the variance was large and scores ranged broadly in both groups (some individuals scoring above 70 and some below 30 in each). In summary, any minor numerical differences observed in these baseline metrics appear due to random variation – overall, participants in the two groups had equivalent cognitive profiles before the learning session. This was important to establish a fair comparison, as it indicates that any differences in learning outcomes can be attributed to the adaptive intervention rather than pre-existing cognitive disparities.

Adaptive Lesson Allocation

In the experimental group, the adaptive system successfully tailored the lesson sizes to individuals as intended. The average number of words per lesson (flashcards per page) assigned in the adaptive group was 10.6 words (SD ≈ 2.1), compared to a fixed 10 words for the control group by design. Figure 1 (far right panel) illustrates the distribution of lesson sizes. The control group box plot is essentially a constant (all participants had the same 10 words per page, aside from negligible deviations due to the total word count not perfectly divided into lessons). In contrast, the adaptive group shows a spread: some participants received as few as 7–8 words per lesson, while others received up to 14–15 words in a lesson. This range reflects personalization based on attention capacity. Indeed, participants with lower pre-test Attention Scores tended to be on the lower end of the lesson-size range, whereas those who demonstrated higher sustained attention were comfortably given larger lesson chunks. This suggests that the adaptation mechanism worked as proposed by CLT to modulate cognitive load: those who might be prone to overload were given smaller, more digestible learning units, while those who could handle more information got slightly larger units, maximizing efficiency. According to the principles of CLT, it may be inferred that the modest advantage that the adaptive learners exhibited could be attributed to a reduced extraneous load. Performance was used as a proxy of sorts to gauge cognitive processes. The present study operationalizes mismatch between lesson size and the cognitive profile of the learner (i.e., a fixed-lesson size) as an extraneous load because the lesson size is not personalized to accommodate their faculties; it must be acknowledged, then, that our experiment assumes that this mismatch causes an extraneous load, when in fact, this is only a theoretical proposition in line with CLT. To that end, the results of the present study become qualified in that they retain validity so long as cognitive load theory does; our results are most meaningful in that context. Largely, however, the validity of CLT as a framework has been well-established through a slowly growing body of inquiry. This adjustment was done without changing the total material learned, only the grouping, thereby aiming to reduce extraneous cognitive load for individuals who needed it.

Vocabulary Retention Performance

The primary outcome was performance on the Toki Pona vocabulary quiz. The results support the assertionthat the adaptive learning tool improves retention. The adaptive group significantly outperformed the control group on the quiz. Participants in the adaptive condition achieved a mean accuracy of 78.3% (approximately 7.8 out of 10 correct, SD ≈ 15%), compared to a mean of 62.5% (about 6.3/10, SD ≈ 20%) in the control group. The median scores (see Figure 1, “Quiz accuracy” panel) were 80% for the adaptive group versus 60% for control. Statistical analysis confirms that this difference is significant: an independent-samples t-test yielded t(58) ≈ 3.2, p < 0.005 (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.8), indicating a large effect size in favor of the adaptive approach. In practical terms, participants using the self-adaptive tool on average remembered 1–2 more words out of 10 than those using the fixed-pace method after the same study period.

It is unlikely that participants merely guessed to an appreciable extent on forms; although one must consider that there is a possibility that perhaps a learner may have guessed on one or two unfamiliar questions, and by chance have gotten them correct, the effect of this is likely minimal and is counterbalanced by the fact that it would have occurred within both groups, ultimately leading to data that is still fundamentally comparable. Further, it is unfathomable that learners had guessed through the entire assessment for either group, considering that the results for both groups were sufficiently high enough such that it would be extremely unlikely (statistically speaking) to occur as a product of fortuity (by guessing alone). Questions, on both forms, were drawn from the same question bank, and because the difficulty, style, and nature of the questions was similar throughout the entire question bank, it is unfeasible that one group received a substantially harder or easier form by randomization; randomization would have only ensured that the questions varied in content, not in difficulty, as to prevent a potential confound. Since questions were designed with the same principle and with the same level of difficulty, it is unlikely randomization would have created forms significantly different in difficulty. By extension, it is also, then, unlikely that the discrepancy in the performance between the adaptive and the fixed-pace learners was attributable to a product of randomization, but was a meaningful quantity as herein described.

Participants spent roughly around the same time not only across both groups, but also within each group. The control group spent a median time of 18.3 minutes for the entire task (including instructional period and post-instruction battery) whereas the experimental group spent a comparable median of 20.2 minutes. This difference is marginal and therefore permits for inferences to be drawn concerning the results; within both groups, there was small standard deviation in time spent on the form, suggesting that the experience was similar for a great majority of the learners. Given in-group similarities and across-group similarities, we may make inferences about the discrepancy in performance between the two groups (experimental and control). By design, those who had shorter lesson sizes, inherently, had more 10-second breaks; all learners are taught 50 words total, divvied among blocks; those who had shorter blocks, therefore had more breaks. Whether this confers some cognitive benefit to learners outside of that caused by adaptive chunking is unknown and could be a potential confound, though its effect is likely negligible considering how nominal the difference in No. of breaks across learners was. In retrospect, equalizing break time such that the total break time was the same regardless of the No. of breaks granted may have reduced this potential confound, but its likely that the benefit conferred by extra such breaks was minimal, at best.

It’s worth noting that the adaptive group’s scores were not only higher on average, but also more consistent – most adaptive learners scored in the 70–90% range, whereas the control group’s scores were more widely dispersed (some scoring as low as 30–50%). Only one participant in the adaptive group scored extremely low (an outlier near 0%, possibly due to disengagement or a technical issue), whereas a few control participants had quite poor scores. When we exclude the single outlier, the adaptive group’s performance appears even more robust. This suggests that adaptive pacing helped ensure a baseline level of understanding for almost all participants, effectively mitigating cases of cognitive overload that can lead to very poor retention.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that incorporating an attention-based adaptive chunking mechanism led to significantly better vocabulary retention, providing evidence for the benefits of cognitively optimized instructional design. Participants who used the adaptive flashcard tutor remembered roughly 25% more words, on average, than those in the non-adaptive control group – a sizable improvement that was achieved without any additional study time. It should be noted, though, that the present study infers these improvements to occur because of the reduced extraneous load set by adaptive chunking, its an inferential operationalization that relies on the well-established principles of CLT. The experiment was designed such that the conditions doled to the fixed-pace learner and the adaptive-pace learner remained as closely identical as possible, with the only select difference being the incorporation of adaptive chunking. It is unlikely that the discrepancy in the outcomes was fortuitous, since all conditions except adaptivity were kept constant and sample size was large enough (n=60). In retrospect, however, it may have been advantageous to collect information on the subjective experience of the learners, which would have provided further insight into the specific causes of this discrepancy; the present study has not done this, but suggests so for future investigations. This outcome is consistent with the central prediction of Cognitive Load Theory: when instruction is tailored to avoid overloading the learner’s limited working memory, more capacity can be devoted to learning the material, resulting in higher performance8. In the adaptive condition, learners with lower attention and working memory scores were given smaller lesson segments, which likely prevented the extraneous cognitive load that would have occurred if they were forced to absorb too many new words at once. Meanwhile, higher-capacity learners received larger chunks, ensuring they were sufficiently challenged and engaged. By personalizing the lesson size, the system kept each individual’s cognitive demands within a manageable range – an approach that aligns with CLT’s recommendation to neither overload nor underload working memory9. Notably, the adaptive group’s score distribution was tighter (fewer very low scores) than the control’s, suggesting that adaptive pacing helped safeguard against cases of cognitive overwhelm that can lead to poor retention. Even learners who might normally struggle were able to perform reasonably well when the lesson was right-sized to their attentional capacity. This lends practical support to the idea that reducing extraneous load through simple adaptive measures can yield disproportionately large benefits for learning outcomes. In essence, our experiment validates that one-size-fits-all instruction can indeed leave some learners behind, whereas a minimal adaptive tweak – here, varying how much content is presented at once – can boost efficacy for a broad range of learners.

These results extend prior research by demonstrating a concrete, scalable form of adaptivity grounded in cognitive capacity. Previous theoretical and empirical work has shown that instructional methods need to consider individual differences in cognitive resources: for example, complex materials should be simplified or segmented for novice or lower-capacity learners to prevent overload, but may be presented more holistically to advanced learners who can integrate information more easily. Our study adds to this literature by focusing on adaptive lesson chunking, which has been less explored in earlier research compared to other forms of personalization (such as adaptive difficulty or feedback). The significant effect size observed (around d = 0.8 in favor of the adaptive tutor) underscores the practical importance of aligning instructional pace and volume with attention-related capacity. This finding resonates with the broader CLT framework: instructional designs that dynamically adjust to the learner help maintain an optimal cognitive load, thereby improving schema acquisition and memory retention8. It also echoes the expertise reversal effect literature, which emphasizes tailoring instruction to the learner’s current ability level5. In our case, adaptivity was based on general attentional performance rather than domain-specific expertise, but the principle is similar: an instructional format effective for one learner might be suboptimal for another, so adaptability leads to better overall efficacy. By showing robust gains in a controlled experiment, we provide empirical support for the value of adaptive instructional chunking and suggest that even simple forms of adaptation (e.g. adjusting how much content is introduced per lesson) can yield measurable learning benefits. This is an encouraging result for the design of educational technology, as it implies that relatively straightforward personalization rules – informed by cognitive science – can make learning more efficient and effective on a wide scale. It also has particularly interesting implications for the classroom environment, since such adaptive instructional design could complement teacher-led education. By incorporating adaptivity into lesson size (content per lesson), teachers can gauge the learning progress of their students and adapt their teaching-style accordingly, leading to an enhanced overall learning experience. Integrating adaptive lessons into education systems is especially advantageous for under-resourced communities, where educational resources may be strained. By employing adaptive lessons, teachers may spend less time reteaching or overexplaining content, allowing for better use of their time: this benefits under-resourced communities who may have limited teaching resources; teachers are less taxed and therefore have more time to efficiently teach students.

It is worth discussing the presumed mechanism behind the adaptive system’s success. We interpret the improved retention in the adaptive group as a result of mitigated cognitive load. Learners who might have been overwhelmed by a fixed 10-word block were instead given, say, a 7-word block, allowing them to maintain focus and encode those items without mental fatigue or confusion. Those extra cognitive “slots” that would have been consumed by overload in the control condition were freed up for germane processing – organizing the new vocabulary into memory. On the other hand, learners capable of handling more information (e.g. attention scores in the top range) received 12–15 words per chunk, which kept them productively busy and perhaps even increased their germane load by encouraging deeper processing of larger word sets in context. Importantly, our adaptive approach aimed to avoid both extremes: overloading and underloading of the learner’s cognitive capacity. Overloading leads to high extraneous load and is known to impair learning2, but underloading – giving far less information or challenge than a learner can handle – can also be detrimental, as it may fail to engage the learner’s available cognitive resources9. If the material is too easy or slow, learners might become disengaged or complacent, meaning they do not exert enough cognitive effort to form durable memories. Our results suggest that the adaptive tutor struck a better balance than the fixed tutor: it provided as much content as each learner could comfortably learn at a time, thereby maximizing the productive use of working memory while minimizing wasted effort on irrelevant processing. This interpretation is consistent with CLT-based guidance that instructional segmenting and pacing should be adjusted to the learner’s capacity – an idea supported by evidence in multimedia learning research that segmenting content helps manage cognitive load for learners with lower prior knowledge or spans of attention10. In summary, the adaptive chunking likely reduced extraneous cognitive load for those who needed it, and maintained or even increased germane load (effective study effort) for those who could handle more, resulting in superior retention overall.

Despite the encouraging results, several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, our sample consisted of adults aged 18–35 in the United States, and all participants were relatively comfortable with computers. This demographic homogeneity means we should be cautious in generalizing the findings to other populations, such as young students, older adults, or learners from different cultural or educational backgrounds. It is possible, for instance, that older adults – who often have reduced working memory capacity or slower processing speed – could benefit even more from adaptive chunking, or they might face different challenges (e.g. age-related visual/auditory issues) not addressed by our system. Conversely, children or teenagers might require different adaptation parameters or engage differently with the tutor. Future studies should therefore test similar adaptive interventions with a broader range of learner populations to verify that the benefits hold universally. Second, while we used well-established cognitive tasks (n-back, psychomotor vigilance, and a sustained attention reading task) to calibrate our adaptive algorithm, these measures are only proxies for a learner’s cognitive capacity. Cognition is multifaceted, and attributes like motivation, prior knowledge of the subject matter, or even momentary factors (fatigue, time of day) can also influence how much a person can learn in one sitting. Our adaptive model weighted only three cognitive scores to determine lesson size; different or additional factors (e.g. real-time performance during the lesson, or stress levels) might improve the personalization further. We also acknowledge that our operational definition of “attentional capacity” may not capture all relevant aspects of cognitive load tolerance. However, given that the two groups did not significantly differ in any baseline cognitive scores, and the only procedural difference was the adaptive versus fixed pacing, we are confident that the performance gains can be attributed to the adaptation rather than some pre-existing advantage. One practical hiccup was a single participant in the adaptive group who scored near zero on the quiz, which we suspect was due to disengagement or a technical issue. While this outlier slightly increased score variability, it does not negate the overall trend – in fact, even including that case, the adaptive group outperformed the control group by a clear margin. Nonetheless, this highlights that adaptive systems are not foolproof: if a learner does not actually engage with the material, or if the platform glitches, no amount of adaptation can guarantee learning. Real-world educational software must account for such scenarios (perhaps by detecting disengagement and re-engaging the learner through prompts or gamified elements). Another limitation of the present study arises from the fact that the subjective (qualitative) experience of the learners was collected, when, in retrospect, this would have likely provided insight critical to an experiment of this nature. Though the data do suggest the value of adaptive interfaces, it would have been extremely insightful had the qualitative subjective experience of the learners been collected; the present study overlooked this opportunity and suggests doing so for future investigations of this nature. Finally, it is important to consider these findings as a proof of concept rather than a finished solution. The adaptive chunking strategy used here is relatively simple; there is room to refine the algorithm and explore more sophisticated forms of personalization. For example, future research could investigate adaptive systems that adjust not only chunk size but also other instructional variables like presentation modality (visual vs. auditory), sequence difficulty (ordering material from easier to harder based on user progress), or feedback levels – all based on continuous monitoring of cognitive load (possibly using real-time data such as eye-tracking or physiological signals). Additionally, it would be valuable to examine long-term outcomes: does adaptive chunking merely improve immediate retention, or does it lead to better long-term retention and transfer of knowledge? Studies could include delayed post-tests or apply the adaptive method to more complex learning tasks (beyond rote vocabulary) to see if the benefits persist. We also suggest exploring how adaptive lesson pacing interacts with learner motivation and metacognition. There is evidence that giving learners some control (or at least the perception of control) can improve engagement, so hybrid approaches combining system-driven adaptation with user choices might be fruitful. In summary, our study provides empirical support for the idea that attention-aware adaptive learning systems can mitigate cognitive overload and significantly improve learning efficacy. This finding contributes to the growing body of work advocating for personalization in educational technology. By demonstrating a substantial learning gain through a relatively straightforward adaptive mechanism, we highlight a practical pathway for making digital instruction more learner-centric. We encourage further research to build on these results – confirming them in diverse settings, examining additional outcomes, and refining adaptive algorithms – so that the full potential of cognitive load theory can be harnessed to benefit learners of all backgrounds. Ultimately, the goal is to design learning environments that intelligently respond to individual needs in real time, thereby maximizing each learner’s ability to absorb and retain new knowledge. The present study takes a positive step in that direction, showing that even basic adaptivity based on cognitive capacity can yield meaningful improvements in learning, consistent with theoretical expectations and with a vision of more efficient, personalized education.

References

- J. Sweller, J. J. G. van Merrienboer, & F. G. W. C. Paas, Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296 (1998). [↩]

- J. Sweller, P. Ayres, & S. Kalyuga, Cognitive Load Theory. Springer (2011). [↩] [↩]

- J. Sweller, Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285 (1988). [↩] [↩]

- J. Sweller, Cognitive load theory: Recent theoretical advances. In J. L. Plass, R. Moreno, & R. Brünken (Eds.), Cognitive Load Theory (pp. 29–47). Cambridge University Press (2010). [↩]

- S. Kalyuga, Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 19(4), 509–539 (2007). [↩] [↩]

- S. Kalyuga, P. Ayres, P. Chandler, & J. Sweller, The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23–31 (2003). [↩]

- F. Paas, A. Renkl, & J. Sweller, Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4 (2003). [↩]

- J. J. G. van Merriënboer & J. Sweller, Cognitive load theory and complex learning: Recent developments and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 147–177 (2005). [↩] [↩]

- T. De Jong, Cognitive load theory, educational research, and instructional design: Some food for thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), 105–134 (2010). [↩] [↩]

- R. E. Mayer & C. Pilegard, Principles for managing essential processing in multimedia learning: Segmenting, pre-training, and modality principles. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2nd ed., pp. 316–344). Cambridge University Press (2014). [↩]