Abstract

First-Person Shooter (FPS) games have grown more popular and gained more economic value, and so too has the various ways to cheat in those same games. While most game anti-cheat approaches were designed to detect software-based cheating, a rising trend of hardware-based cheating starting from 2024, particularly through Direct Memory Access (DMA) cards, poses a significant challenge to game security. This paper proposed a novel machine-learning based multi-tier cheat detection framework to tackle both software and hardware based cheating. The proposed solution consists of three sequential tiers. Tier 1 deploys a lightweight machine learning model on the game client to conduct high-level preliminary detection based on real-time game play data. Tier 2 runs a more powerful machine learning model on the game company’s remote server. Suspect cases detected by Tier 1 are sent to Tier 2 for more comprehensive and high-precision analysis based on player’s historical statistics and visual play data. Tier 3 employs manual expert validation for low-confidence cases. Experimental results on a dataset shared by other researchers demonstrated the viability of this approach, with models like XGBoost serving effectively in Tier 1. In Tier 2 analysis, the TabNet model demonstrated superior performance over MLP and Wide and Deep architectures, achieving the highest accuracy and AUC values. Although Tier 3 was not carried out in this research due to the limitation, the constructed layered security defense system can achieve its primary objective to combat the evolving techniques of cheating in FPS games.

Keywords: Game Security, Machine learning, multi-tier detection, FPS game

Introduction

As various FPS games have grown more popular and gained more economic value, so too has the various ways to cheat in those same games1. As a result, maintaining fairness and security in order to ensure the inherent competitive integrity of the games has become a critical challenge as not only do honest players flock towards the games, but also cheaters who exploit the game’s vulnerabilities for their own gain2. Popular competitive games have become prime targets for cheaters and malicious players to exploit system vulnerabilities for personal gain3.

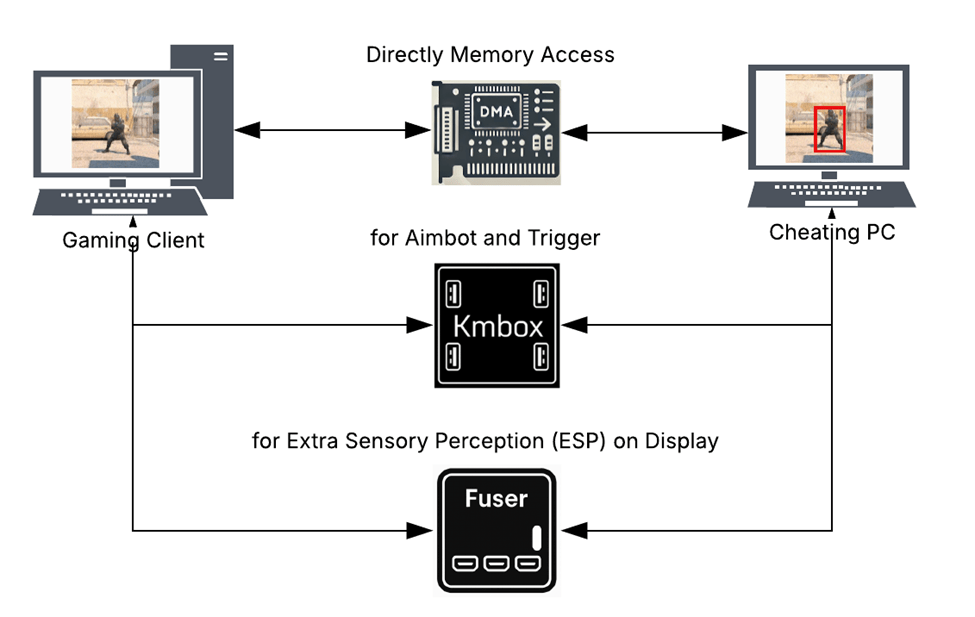

Usually, when players cheat, there is one of two ways that they’ll install the cheats on their gaming device in order for them to utilize cheats in game: either through a software installation that captures visual data, or by installing a Direct Memory Access (DMA) card into their hardware4.

The software cheating approach is more traditional and usually involves running a model on the client’s computer that utilizes advanced machine learning to detect objects and draw a visual component for the game as seen by the player that differs from what honest players will see on their screen5. Figure 1–as seen below–displays a simple explanation on how software cheats function. Already, many solutions to combat software cheating have been developed since it is relatively easier to detect and prevent. However, the hardware approach to cheating is a newer trend and much harder to detect6‘7‘8‘9‘10‘11.

The hardware approach to cheating is a rising trend and involves buying and directly installing a DMA card into the client’s hardware, enabling access to the game’s data on a second computer’s screen. The game data obtained by the DMA card is passed to other hardware devices to detect objects–usually being opposing players4‘12. This specific hardware approach can be as complicated as what is shown in Figure 2, making it much harder to detect than the software approach previously mentioned. If anti-cheat detection systems only analyze the visual data on the gaming pc, they won’t be able to detect cheats because of how subtle the signs can be. The cheats will be on a completely different device from the “gaming device” meaning there aren’t many traces to track using technology. There are various solutions that have been proposed by researchers in this field regarding how to combat this rising threat: such as mentioned by J. Zhang, et. al. in their paper13.

Each approach is more compatible with different well-known hacks: with the software approach being perfect for aimbot but not as compatible with wallhacks (without the hardware to directly access the game’s data, if a user cannot see an object the model that enables cheats won’t be able to either) explaining why some players deign to use one or the other depending on which cheats they aspire to employ.

In response, game developers have started implementing advanced cybersecurity measures and machine learning technologies designed to detect, prevent, and respond to the growing threat that cheats present14. Anti-cheat and cheating’s evolutions push each other to constantly improve. The review paper15 categorized five main approaches used to combat cheating in competitive games: game-bot detection based on avatar trajectory16, anomaly detection17, supervised machine learning approaches18, behavioral analysis19 and vision-based analysis20.

Early age anti-cheat methods usually relied on avatar trajectory: for example, a 2008 study21 on bot detection proposed an algorithm that analyzes the player’s trajectory in order to differentiate between whether they were human or indicated automated behavior–exploiting the subtle inconsistencies that using a system such as Aimbot would exhibit in comparison to real players. However, as cheating methods advanced in order to outpace the early age anti-cheat systems, so did those same systems as the use of machine learning in order to combat cheats and exploitations ingame grew more popular.

A big breakthrough in this area came from the invention and development of the DNN, or the Deep (learning) Neural Network. DNN was a high-level machine learning model that was able to process huge amounts and very complicated data. As traditional machine learning models couldn’t analyze this complicated amount of data, the development of the DNN made robust vision-based cheat detection viable22.

This article aims to both describe and review popular methods used to cheat in online FPS games, but also propose a new method to detect and prevent cheating.

Background

The integration of machine learning and behavioral analysis into game cybersecurity represents a major shift in how game developers detect and prevent cheating. AI and machine learning can address cheating by rapidly analyzing vast sets of gameplay data and historical data in order to detect anomalies and suspicious behaviors from popular cheats and hacks such as Aimbot or Wallhacks.

Several major game developers have already adopted anti-cheat systems that utilize the mechanics of machine learning to combat the rise of cheating in their respective competitive environments23‘24. For example, Valve’s VACnet, developers for the popular game Counter-Strike employs the use of deep learning models that are trained on thousands of gameplay replays that evaluate player behavior. By being trained on this data, they’re able to identify and flag anomalies that deviate from expected human behavior, letting VACnet significantly reduce cheating incidents in Counter-Strike.

With the constant development of cheating, research on how to prevent cheaters in FPS games has become an ongoing area of research.

Methods

My Proposal: Machine Learning Based Multi-Tier Cheat Detection

In order to combat the methodology usually employed by cheaters, I’ve come up with the idea of a multi-tiered cheat detection system–with each tier getting more and more precise in order to accurately pinpoint any real cheaters, hopefully without detaining any false alarms.

My proposed solution consists of the following three tiers:

- Tier 1: Lightweight machine learning model driven cheat detection based on players’ action, statistics data and sensory perception data in the current playing session.

- Tier 2: Heavy machine learning model driven cheat detection based on players’ historical data, playing data and visual game replaying data.

- Tier 3: Manual expert-involved validating.

Tier one: Light-weight Client-side Cheat Detection

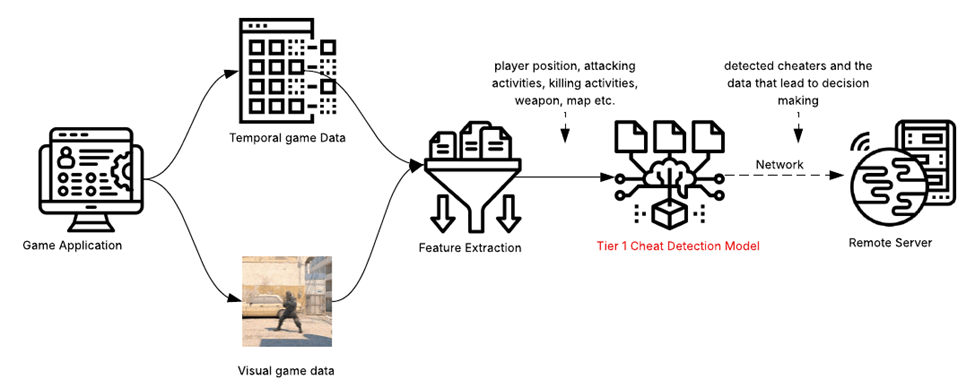

The first tier of this system, as depicted in Figure 3, is deployed on the player’s personal computer and operates simultaneously with the game client. Its primary function is to capture real time gameplay data for cheat detection. An important consideration for this component is to maintain a positive and smooth user experience. This makes a careful design and implementation of the machine learning model in this step necessary in order to avoid excessive resource consumption that could interfere with the player’s gaming experience.

As the first tier component in a multi-tier solution, I designed the first tier of the system to have the following characteristics:

- Runs on a random schedule to capture playing session data.

- Performs quick feature extraction.

- Uses a light-weight machine learning model to make quick decisions.

- Focus on recall-targeted cheat detection.

The machine learning models in this tier are traditional machine learning models trained on both cheater and honest player data, allowing for a horizontal comparison of behavior data across players.

Once the model identifies a player as a potential cheater, visual data using the timestamps from the suspicious gameplay and extracted behavior features are sent to a remote server for further assessment.

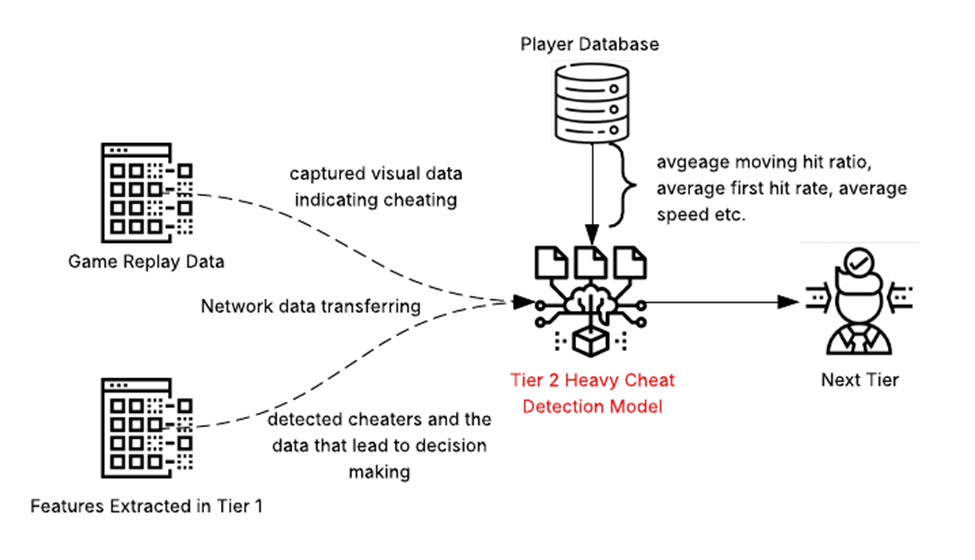

Tier 2: Server Side Model-Based Analysis

As seen in Figure 4, Tier 2 receives the game replay data and extracted features from Tier 1, but also obtains the player’s historical data (such as killing statistics and level-up times) from the player account database and takes them into account during decision making. The historical data allows the model in Tier 2 to identify and flag sudden anomalies like rabid skill increases or unusually fast progress through competitive ranks. The model in Tier 2 will also be able to perform complex vision data analysis on the replay data for further assessment.

Any data that is flagged as false alarms are eliminated by Tier 2’s model and can be used as regular player data in future machine-learning model retraining. After passing through Tier 2, the data should be properly organized, with honest players being removed from the cheater list.

To optimize the efficiency of our cheat detection process, Tier 2 would possess a confidence threshold to decide the data sent to Tier 3. This means that only cases identified by the Tier 2 model with a confidence level below this threshold will proceed to Tier 3 for final validation in order to not overwhelm it. This approach aims to enhance the accuracy of cheat detection while controlling the cost associated with Tier 3 operations.

Tier three: Expert-Involved Final Validation

Tier 3 is the final decision, scrapping the use of machine learning entirely and using the judgement of real life human ‘experts’ in the gaming field as manual verification. However, since this method is the most expensive and time consuming out of the three tiers, it is only employed in the cases with relatively low confidence assigned by Tier 2 models. If the final decision between experts decides a player is a cheater, a warning or ban notification is sent to the cheater’s account (depending on the game’s policy).

All cheaters’ data will go into the cheater database in order to improve both tier 1 and tier 2’s model training. Considering that nothing can be 100% accurate, the stored data can also be used to respond to players’ appeals if they are identified as cheaters.

Results

For FPS game cheater detection, it is hard to find a public online dataset that can be used to benchmark new approaches and algorithms. At the time of August 2025, the most comprehensive data that is online is the data shared by authors of the paper “Identify As A Human Does: A Pathfinder of Next-Generation Anti-Cheat Framework for First-Person Shooter Games”25. In their experiments, they collected temporal features captured in the playing time and also each player’s historical statistics data for further analysis. My experiment set up is shown below based on the available data.

Tier 1: Efficient Machine Learning Algorithms on Temporal Data

In the initial stage of training machine learning algorithms, I utilize all available temporal features. This step prioritizes efficiency and aims for relatively high recall values.

The temporal data exhibits the following characteristics:

- 7 numerical features

- 14296 training samples

- 7164 positive (cheater) samples

- 7132 negative (non-cheater) samples

- 9923 samples for model validation during training

- 997 positive samples

- 8926 negative samples

- 10591 test samples

- 1053 positive samples

- 9538 negative samples

For Tier 1, I selected four machine learning algorithms. After training, all of these models can be deployed to the player’s machine for prediction.

- Random Forest

- Logistic Regression

- XGBoost26

- Neural Network

The selection of the four machine learning models was not based on any performance criteria. The goal of this research is to investigate the feasibility of deploying a fast and lightweight machine learning model directly on the client’s machine, not the actual model itself. In reality, the model performance can change significantly depending on the specific game and the data.

Class balance handling and dataset splitting methodology used in training these models are listed in the following table:

| Category | Technique/Methodology |

| Class Balance Handling | Random Forest and Logistic Regression automatically adjusts weights to be inversely proportional to class frequencies, giving more importance to the minority class. XGBoost specifically handles imbalanced data by scaling the gradient for positive class examples. Neural Network does not use explicit weight balance strategy. |

| Recall-Optimization Scoring | “recall” is set as the evaluation metrics which prioritizes the model’s ability to identify the positive class (cheaters), minimizing false negatives. |

| Threshold Optimization | A weighted score function 0.7 × recall + 0.3 × f1 is used to evaluate the performance to ensure to find the optimal classification threshold that maximizes the primary goal (recall). |

| Random Seeds | random_state=42 is used for all models |

| Cross Validation (CV) | 3-fold cross-validation is used for hyperparameter tuning. |

| Validation Strategy | The system is designed to receive pre-split data (train/validation/test), with the actual splitting handled by external components. |

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | f1-Score | AUC |

| Random Forest | 0.9 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.68 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.9 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.6 |

| XGBoost | 0.9 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.71 |

| Neural Network | 0.8 | 0.23 | 0.4 | 0.29 | 0.66 |

From the data shown in the above table, obviously the XGBoost algorithm can provide more promising results. The only data we can get contains only seven features, the limitation of the experimental data is the main reason leading to low recall and precision.

To better address the limitation of features in experimental data, I found another set of FPS game data that are publicly available. The data is available in Huggingface’s dataset27‘28. I split the data into train/validation/test with ratio 70/15/15, the following is the information of this data:

- 44 numerical features

- 82250 training samples

- 51765 positive (cheater) samples

- 30485 negative (non-cheater) samples

- 17625 samples for model validation during training

- 10994 positive samples

- 6631 negative samples

- 17625 test samples

- 10933 positive samples

- 6692 negative samples

I retrained the same four machine learning models with the same starting parameters. The following table is the value captured for each model:

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | f1-Score | AUC |

| Random Forest | 0.9596 | 0.9448 | 0.9929 | 0.9682 | 0.9927 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.6449 | 0.6372 | 0.9926 | 0.7762 | 0.8253 |

| XGBoost | 0.6252 | 0.6234 | 0.9996 | 0.7679 | 0.8185 |

| Neural Network | 0.8955 | 0.8661 | 0.9836 | 0.9211 | 0.9506 |

From the data shown above, XGBoost is still the winner with the highest recall rate since the goal of Tier 1 is to keep high recall (don’t miss cheaters). However, although the Random Forest algorithm has a recall rate lower than XGBoost, the difference is not significant. Especially after evaluating the accuracy and AUC value, the Random Forest algorithm is obviously over-performed than other algorithms.

The comparison of the two tables in Tier 1 clearly explained that:

- The machine learning algorithm in Tier1 can successfully achieve the goal of providing high recall on cheat detection;

- The amount of features has significant impact on the performance of cheat detection in Tier 1;

- Which algorithm works the best depends on the amount of features and feature types. In reality, actual training data could help determine the best algorithm.

Tier 2: Further Analysis using Machine Learning Algorithms on Statistics Data

Data used in this step are each player’s historical playing statistic data. Since the player statistics data is not available for the second data set used in Tier 1, data used in this tier are still the data shared by authors from citation 8. A little bit from the machine learning algorithms applied in tier 1, algorithms in this tier are run on a remote service with much higher computing capability. As explained in the previous section, these algorithms can take longer time to run. The focus at this step is the accuracy of cheater detection.

The following is the characteristic of the statistics data:

- 28 numerical features

- 8226 training samples

- 826 positive (cheater) samples

- 7400 negative samples

- 10257 validation samples

- 1027 positive samples

- 9230 negative samples

- 10860 test samples

- 1099 positive samples

- 9761 negative samples

The machine learning algorithms I choose are:

- Multi Layer Perceptron

- TabNet (Google)29

- Wide and Deep

The following table shows the performance of these three algorithms:

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | f1-Score | ROC_AUC | PR_AUC |

| MLP | 0.9 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.31 |

| TabNet | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.84 | 0.45 |

| Wide and Deep | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 0.32 |

Compared with the data used in Tier 1, the player statistics data contains more feature dimensions; In return, the testing results in this tier show great improvement on both precision and AUC values. In summary, the TabNet algorithm performs better than the other two algorithms with highest accuracy, precision and AUC values. It is believed the main reason is because the data is tabular data while TabNet can handle tabular data much better than general MLP algorithms and the Wide and Deep neural network algorithms.

The following chart shows the ROC curves of the three algorithms. It demonstrates from another perspective that TabNet performs better than the other two algorithms. As to why both MLP and the Wide and Deep algorithms have the shown ROC curve, a brief online study explains that this could be caused by clustered prediction probabilities, an artifact feature in the data, or data leakage etc. Given the primary goal of the proposal in this paper is not to optimize the performance of a specific model, deep analysis of the feature data that caused this scenario falls out of the scope of this study.

All these algorithms and data are available on my github research repository: Multi-Tier Anti-Cheat.

Due to the limitations of this research, it is challenging to find a person with expert-level skills to find the player data with low confidence. Introducing human judgement (especially from experts) is a good idea since they can often use their valuable playing experience to make accurate judgement. This will be my future work.

Summary

This research examines the increasing problem of cheating in FPS games then proposes a novel multi-tiered cheat detection system. Tier 1 involves lightweight, client-side machine learning models for real-time detection based on player actions and sensory data. Tier 2 employs heavier, server-side machine learning models that analyze historical player statistics and visual replay data for more accurate detection. Finally, Tier 3 utilizes human experts for final validation of low-confidence cases identified by Tier 2, aiming to reduce false positives and improve overall accuracy in combating advanced cheating.

Due to the limitation of data availability and challenges to find the right human expert to carry out Tier 3 validation, experimental results showed the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

This is posited as the strategic direction for anti-cheat measures in FPS games. The proposal’s objective is to address the fundamental causes of cheating rather than merely reacting to their manifestations, which is essential for developing effective countermeasures against the rapidly evolving cheat threats within the gaming industry.

Comparison with VACnet

As the leading anti-cheat service provider, Valve has integrated VACnet, an AI-powered anti-cheat approach into the Valve Anti-Cheat (VAC) system. VACnet operates through a two-step process: data collection for server-based analysis, followed by a human overwatch step.

The proposed multi-tiered cheat detection system offers the following advantages over Valve’s VACnet, particularly in addressing modern cheating methods like DMA cards.

- Tiered Resource Optimization: Unlike VACnet’s server-side analysis, this system provides client-side cheat detection (Tier 1), followed by a server side reinforcement (Tier 2), ensuring efficiency and accuracy.

- Holistic Data Integration: Applies diverse data sources including real-time actions, sensory data, historical statistics, and visual replays.

- Human Expert Validation: Although it offers a similar step of human oversight for fairness and trust, cases passed to Tier 3 is expected to be much less than VACnet after the pruning of the previous two tiers.

This multi-tiered solution can significantly enhance VACnet’s capabilities by integrating it as a key component. VACnet’s deep learning models for gameplay replay analysis could function as an advanced part of Tier 2, processing data from players flagged by Tier 1. Tier 1 would serve as an efficient client-side pre-filter, reducing VACnet’s computational load by escalating only high-probability cheating cases for deeper analysis. The proposed system’s validated cheater database would also provide continuously updated data for retraining and fine-tuning VACnet’s models.

Scalability and Cost Analysis

The proposed cheat detection approach is designed to be cost-effective by minimizing the need for expensive expert evaluations and heavy machine learning models in early stages.

Tier 1 uses lightweight machine learning models deployed directly on client machines, distributing the computational cost across all players. These models are designed for speed and are not expected to impact the client’s gaming experience.

Following Tier 1, the number of players targeted by the Tier 2 model is significantly reduced, allowing for the use of more advanced models since the mode runs on a remote service and detection speed is not critical in this stage.

After the initial pruning by both tiers, Tier 3, the most expensive step, is applied to a much smaller group of players.

In essence, this approach offers a scalable solution with controllable costs. The primary investment lies in Tiers 2 and 3.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Thuraisingham for leading the Cybersecurity Workshop that piqued my interest and led me to research this topic.

Appendix

Tier 1 Features in the First Dataset

- Eco_Final_Pred

- Movement_Final_Pred

- Dmg_Final_Pred

- Flash_Final_Pred

- Grenade_Final_Pred

- Kill_Final_Pred

- Wf_Final_Pred

Tier 1 Features in the Second Dataset

Details can be found in URL: https://huggingface.co/datasets/CS2CD/Context_window_256/blob/main/README.md

- attacker_X

- attacker_Y

- attacker_Z

- attacker_vel

- attacker_pitch

- attacker_yaw

- attacker_pitch_delta

- attacker_yaw_delta

- attacker_pitch_head_delta

- attacker_yaw_head_delta

- attacker_flashed

- attacker_shot

- attacker_kill

- is_kill_headshot

- is_kill_through_smoke

- is_kill_wallbang

- attacker_midair

- attacker_weapon_knife

- attacker_weapon_auto_rifle

- attacker_weapon_semi_rifle

- attacker_weapon_pistol

- attacker_weapon_grenade

- attacker_weapon_smg

- attacker_weapon_shotgun

- victim_X

- victim_Y

- victim_Z

- victim_health

- victim_noise

- map_dust2

- map_mirage

- map_inferno

- map_train

- map_nuke

- map_ancient

- map_vertigo

- map_anubis

- map_office

- map_overpass

- map_basalt

- map_edin

- map_italy

- map_thera

- map_mills

Tier 1 Library and Model Details

The versions of major libraries used in this research:

- scikit-learn: 1.7.1

- XGBoost: 3.0.5

- PyTorch: 2.7.1

- NumPy: 2.2.6

- Pandas: 2.3.2

- Python: >=3.10

Model Training Details

1. Random Forest Classifier

- Algorithm: RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn

- Hyperparameter Search: RandomizedSearchCV with 20 iterations

- Cross-validation: 3-fold CV

- Optimization Metric: Recall (to minimize false negatives)

- Best Hyperparameters:

- n_estimators: 200

- max_depth: None (unlimited)

- min_samples_split: 2

- min_samples_leaf: 1

- class_weight: ‘balanced’

- random_state: 42

2. Logistic Regression

- Algorithm: LogisticRegression from scikit-learn

- Hyperparameter Search: GridSearchCV (full grid search)

- Cross-validation: 3-fold CV

- Optimization Metric: Recall

- Best Hyperparameters:

- C: 0.1 (regularization strength)

- penalty: ‘l1’ (Lasso regularization)

- solver: ‘saga’

- max_iter: 1000

- class_weight: ‘balanced’

- random_state: 42

3. XGBoost Classifier

- Algorithm: XGBClassifier from XGBoost 3.0.5

- Hyperparameter Search: RandomizedSearchCV with 20 iterations

- Cross-validation: 3-fold CV

- Optimization Metric: Recall

- Best Hyperparameters:

- n_estimators: 100

- max_depth: 3

- learning_rate: 0.01

- subsample: 0.8

- scale_pos_weight: 3 (handles class imbalance)

- eval_metric: ‘logloss’

- random_state: 42

4. Neural Network (MLPClassifier)

- Algorithm: MLPClassifier from scikit-learn

- Hyperparameter Search: RandomizedSearchCV with 20 iterations

- Cross-validation: 3-fold CV

- Optimization Metric: Recall

- Best Hyperparameters:

- hidden_layer_sizes: (100, 50) – two hidden layers

- activation: ‘tanh’

- alpha: 0.001 (L2 regularization parameter)

- learning_rate: ‘adaptive’

- max_iter: 1000

- random_state: 42

Tier 2 Dataset Features

- avgKill

- special_hit_ratio

- oneTapPercentage

- precision

- ratio of hit when moving

- flashEfficiency

- avg_TTK

- var_TTK

- occluderKill

- firstHitPrecision

- inertialShotPercentage

- Var_hit_group

- propsStats

- BlindKillPercentage

- CHPrecision

- firstKillRate

- avg_delta

- var_delta

- avg_gamma

- var_gamma

- avg_t0_t1_duration

- var_t0_t1_duration

- avg_t1_t2_duration

- var_t1_t2_duration

- avg_duration

- var_duration

- avg_speed

- var_speed

Tier 2 Model Details

1. Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

Architecture:

- Framework: PyTorch 2.7.1

- Model Type: Feed-forward neural network

- Hidden Layers: (128, 64) neurons – configurable via –hidden

- Activation: ReLU between layers

- Output: Single neuron with sigmoid activation for binary classification

Training Hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate: 1e-3 (0.001)

- Optimizer: Adam

- Batch Size: 256

- Number of Epochs: 50 (max)

- Dropout: 0.2 (20%)

- Loss Function: CrossEntropyLoss with class weights

Regularization:

- Dropout: 0.2 applied after each hidden layer

- Class Weighting: Automatic class weight calculation (neg_samples/pos_samples)

- Early Stopping: Patience of 5 epochs based on validation AUC

Training Configuration:

- Data Loader: PyTorch DataLoader with shuffle=True for training

- Device: Auto-detection (CUDA if available, else CPU)

- Gradient: Standard backpropagation with Adam optimizer

2. TabNet

Architecture:

- Framework: pytorch-tabnet 4.1.0 (built on PyTorch)

- Model Type: Attention-based tabular neural network

- Architecture Parameters:

- n_d: 16 (decision dimension)

- n_a: 16 (attention dimension)

- n_steps: 4 (number of decision steps)

- n_independent: 2 (number of independent GLU layers)

- n_shared: 2 (number of shared GLU layers)

Training Hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate: 2e-2 (0.02)

- Optimizer: Built-in TabNet optimizer (Adam-based)

- Batch Size: 1024

- Virtual Batch Size: min(128, batch_size) = 128

- Number of Epochs: 200 (max)

- Momentum: 0.02

Regularization:

- Sparsity Regularization: λ_sparse = 1e-4

- Gamma: 1.5 (relaxation parameter)

- Class Weighting: Sample-wise weights based on class imbalance

- Early Stopping: Patience of 20 epochs based on validation AUC

Training Configuration:

- Evaluation Metric: AUC during training

- Seed: 42 for reproducibility

- Device: Auto-detection or forced CPU

3. Wide & Deep

Architecture:

- Framework: PyTorch 2.7.1 (custom implementation)

- Model Type: Wide & Deep architecture

- Wide Component: Single linear layer on raw features

- Deep Component: MLP with (128, 64) hidden layers

- Output: Sum of wide and deep components

Training Hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate: 1e-3 (0.001)

- Optimizer: Adam

- Batch Size: 256

- Number of Epochs: 50 (max)

- Dropout: 0.2 (20%) in deep component only

- Loss Function: CrossEntropyLoss with class weights

Regularization:

- Dropout: 0.2 applied in deep tower only

- Class Weighting: Automatic class weight calculation

- Early Stopping: Patience of 5 epochs based on validation AUC

Training Configuration:

- Architecture: Wide (linear) + Deep (MLP) combined

- Device: Auto-detection (CUDA if available, else CPU)

- Gradient: Standard backpropagation

References

- S. Bawker. AI in Esports: how machine learning is transforming anti-cheat systems in esports? https://www.jumpstartmag.com/ai-in-esports-how-machine-learning-is-transforming-anti-cheat-systems-in-esports/ (2025). [↩]

- S. Fogel. Pro ‘CS:GO’ player ‘Forsaken’ receives 5-year ban for cheating. https://variety.com/2018/gaming/news/counter-strike-forsaken-cheating-ban-1202998388/ (2018). [↩]

- FortniteCompetitive. Realistically how is Epic supposed to stop this? https://www.reddit.com/r/FortniteCompetitive/comments/1bkklxe/realistically_how_is_epic_supposed_to_stop_this (2024). [↩]

- Anti-Cheat Expert. Emerging threats to game integrity: unpacking the DMA cheat conundrum. https://intl.anticheatexpert.com/resource-center/content-68.html (2025). [↩] [↩]

- A. Kanervisto, T. Kinnunen, V. Hautamäki. GAN-Aimbots: using machine learning for cheating in first person shooters. IEEE Transactions on Games. Vol. 15(4), pg. 566-579 (2023). [↩]

- C. Sun, K. Ye, L. Su, J. Zhang, C. Qian. Invisibility cloak: proactive defense against visual game cheating. 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24). pg. 3045-3061 (2024). [↩]

- H. Künstner, M. H. Olsen, S. Skejø-Andresen. From exploit to enforcement: dissecting the evolution of video game cheating and anti-cheat technologies. Thesis report – Cyber Security Master. Depart of Electronic Systems, Aalborg University, Copenhagen, Denmark (2024). [↩]

- T. Warren. Valorants winning the war against PC gaming cheaters. https://www.theverge.com/2024/11/4/24283482/valorant-is-winning-the-war-against-pc-gaming-cheaters (2024). [↩]

- R. Noah. How anti-cheats are vulnerable to basic direct memory access cards? https://medium.com/%40noah_44244/how-anti-cheats-are-vulnerable-to-basic-direct-memory-access-cards-94950f57f59e (2024). [↩]

- A. Shehzadi. DMA cards and cheaters: a deep dive into game exploitation. https://techbullion.com/dma-cards-and-cheats-a-deep-dive-into-game-exploitation (2025). [↩]

- D. El. A brief history of game cheating. https://www.cyberark.com/resources/endpoint-security/a-brief-history-of-game-cheating (2024). [↩]

- A. Hogan. 2024 – the year of the hardware cheat? https://www.intorqa.gg/post/2024-the-year-of-the-hardware-cheat (2024). [↩]

- J. Zhang, C. Sun, Y. Gu, Q. Zhang, J. Lin, X. Du, C. Qian. Identify as a human does: a pathfinder of next-generation anti-cheat framework for first-person shooter games. Computer Science.Cryptography and Security. Eprint 2409.14830 (2024). [↩]

- Metrinegaming. AI vs. hackers: can machine learning protect competitive games from exploits? https://medium.com/@metrinegaming/ai-vs-hackers-can-machine-learning-protect-competitive-games-from-exploits-c97bb7bc554a (2025). [↩]

- Z. Xu, R. Yu, Y. Liang, Z. Chen, Y. Wan. Advancements in cheating detection algorithms in FPS games. International Conference on Computer Application and Information Security (ICCAIS 2024). Vol. 13562(33) (2025). [↩]

- H. K. Pao, K.T. Chen, H. C. Chang. Game bot detection based on avatar trajectory. ICEC 2008, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5309, pg. 94-105 (2008). [↩]

- E. Kaiser, W. Feng, T. Schluessler. Fides: remote anomaly-based cheat detection using client emulation. Proceedings of the 16th ACM conference on Computer and communications security. pg. 269-278 (2009). [↩]

- L. Galli, D. Loiacono, L. Cardamone, P. L. Lanzi. A cheating detection framework for unreal tournament iii: a machine learning approach. IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG). pg. 266-273 (2011). [↩]

- D. Liu, X. Gao, M. Zhang, H. Wang, A. Stavrou. Detecting passive cheats in online games via performance-skillfulness inconsistency. 47th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks. pg. 615-626 (2017). [↩]

- A. Jonnalagadda, I. Frosio, S. Schneider, M. McGuire, J. Kim. Robust vision-based cheat detection in competitive gaming. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Eprint 2103.10031 (2021). [↩]

- H. K. Pao, K.T. Chen, H. C. Chang. Game bot detection based on avatar trajectory. ICEC 2008, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5309, pg. 94-105 (2008). [↩]

- H. Benaddi, K. Ibrahimi, A. Benslimane, M. Jouhari, J. Qadir. Robust enhancement of intrusion detection systems using deep reinforcement learning and stochastic game. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. Vol. 71(10), pg. 11089-11102 (2022). [↩]

- Brandon. Riot requires kernel level anti-cheat software. https://tuta.com/blog/riot-requires-kernel-level-anticheat (2024). [↩]

- S. W. Zhao, J. H. Qi, Z. P. Hu, H. Yan, R. Z. Wu, X. D. Shen, T. J. Lv, C. J. Fan. VESPA: a general system for vision-based extrasensory perception anti-cheating in online FPS games. IEEE Transactions on Games. Vol. 16(3), pg. 611-620 (2024). [↩]

- J. Zhang, C. Sun, Y. Gu, Q. Zhang, J. Lin, X. Du, C. Qian. Identify as a human does: a pathfinder of next-generation anti-cheat framework for first-person shooter games. Computer Science.Cryptography and Security. Eprint 2409.14830 (2024). [↩]

- T. Chen, C. Guestrin. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. pg. 785-794 (2016). [↩]

- M. M. Z. Loo, G. Lužkov. AntiCheatPT: a transformer-based approach to cheat detection in competitive computer games. Master Thesis. IT University of Copenhagen (2025). [↩]

- M. M. Z. Loo, G. Luẑkov. Context_window_256. https://huggingface.co/datasets/CS2CD/Context_window_256 (2025). [↩]

- S. O. Arik, T. Pfister. TabNet: attentive interpretable tabular learning. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 35(8), pg. 6679-6687 (2019). [↩]