Abstract

Over the last 15 years, support for UK populist parties — UKIP and later Reform UK —has risen significantly. While voter surveys often point to immigration as the primary driver, this study employs a quantitative regional analysis to assess the relative importance of prosperity, austerity, and immigration in explaining populist voting. It uses constituency-level election results aggregated to the ten ITL1 regions of England and Wales to model changes in the populist vote share between the 2010 and 2024 general elections. Three objective proxies are employed: regional house prices (for prosperity), discretionary public spending per capita (for austerity), and the share of the foreign-born population (for immigration). Bivariate and multivariate OLS regression analyses show that only house price changes have a robust, statistically significant effect, with rising prosperity being linked to lower populist vote shares (negative correlation). The rationale for using house prices is based on their macroeconomic significance and centrality to household wealth. However, correlation does not imply causation, and the mechanisms linking prosperity and voting behavior are likely to be more complex, involving perceptions, political messaging, and cultural factors. The contribution of this study is to extend prior work on Brexit voting by providing a multivariate, longitudinal comparison of prosperity, austerity, and immigration across multiple UK elections. Its main limitation is the reliance on just ten regional data points. Future research should use more granular local authority-level data, incorporate survey-based perceptions of immigration (not only real immigration data), and explore causal relationships using more advanced statistical methods.

Keywords: populism, recession, prosperity, house prices, austerity, discretionary spending, immigration, UKIP, Reform UK, brexit

Introduction

The Rise of Populism in the UK

The share of the vote across Europe for populist parties, as defined by Rooduijn et al,has increased from a level of around 12% in the early 1990s to around 32% by 20221.

In the UK, by far the largest such populist party falling within this classification, has been the UK Independence Party or UKIP. This party was later effectively replaced by Reform UK, still under the leadership of Nigel Farage, who had previously led UKIP2.

Support for UKIP/Reform UK has risen from relatively low levels at general elections in the first decade of this century, to the party winning double-digit vote shares. As a result, the parties have exerted significant political influence on the more established, mainstream parties namely the Conservative Party and the Labour Party, which have led all the ruling governments over the last century. Moreover, as of the time of writing (July 2025), Reform UK commands a clear lead over both the Labour and Conservative Parties, in national opinion polling3.

Given that Reform UK is likely to play an important role in determining the next government, it is important to understand the structural drivers of the rise of populism that are behind its long-term growth in support.

The rise in national support for UKIP/Reform UK largely occurred between the general elections of 2010, when UKIP won 3.1% of the vote, and that of 2015, when the party gained 12.6% of the national vote (Figure 1)4. This was followed shortly after by the Brexit referendum, when UKIP successfully campaigned for the UK’s departure from the European Union.

It is important to note that exceptional, contextual factors significantly reduced the vote share for UKIP in the general elections of 2017 (held shortly after the Brexit referendum) and 2019 (when Farage’s new Brexit Party did not contest Conservative-held seats). These results were not comparable to the other general elections shown in Figure 1 and have been excluded.

By the general election of 2024, UKIP’s successor party Reform UK further increased the populist vote share to 14.3%5. Furthermore, Reform UK was the strongest-performing party in terms of vote share at the May 2025 local elections6 and as of the time of writing (July 2025), Reform UK commands is the leading party in national opinion polling6,3.

However, this rise in support for the UK’s main populist party has not been geographically homogeneous. This was also the case in the Brexit vote of 2016, as shown by Rudkin et al and Haußmann et al7),8.

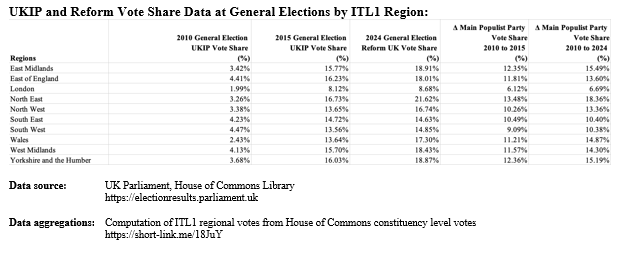

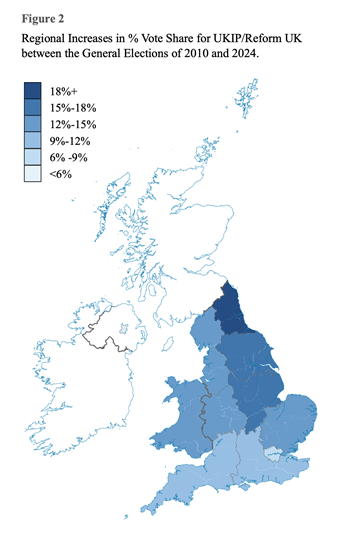

Between 2010 and 2024 elections, when the UKIP/Reform UK fielded a full slate of candidates in England and Wales, there were significant regional differences in support, when aggregated at the level of the 10 International Territorial Level (ITL1) regions used for statistical purposes.

London showed the lowest increase in UKIP/Reform UK voting share (+6.7%) between 2010 and 2024, while the Northeast of England showed the highest increase (+18.4%), almost three times higher.

These regional variations in the vote share of UKIP/Reform UK provide a fertile basis for understanding the structural drivers of populist support at a macro level over a longer period (2010-2024) than is typically covered in the existing literature, which has focused on the 2016 Brexit referendum or elections up to 2015.

Literature Review

The existing literature provides a foundational, if somewhat incomplete, understanding of the factors driving the rise of populism in the UK.

Three broad themes emerge. These are levels of economic well-being, the impact of cuts to public services (usually referred to as “Austerity” in the UK) and immigration. This represents a debate of economic grievances (prosperity, austerity) vs cultural backlash (with immigration at its core).

Regarding economic prosperity, it should be noted that the rise in populism in the UK has occurred since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (“2008 GFC”) and its aftermath.

The immediate consequence of the 2008 GFC was a global recession which saw the UK and much of the world experience negative economic growth. This was followed by years of consistently anaemic growth in the UK, attributed by Smith in part to fiscal consolidations (hereafter “austerity”) that followed9. Furthermore, UK economic forecasts (Riley & Chote, 2014) from this period overestimated the speed and scale of recovery10. The 2008 GFC had a deep, wide-ranging, and long-term macroeconomic impact on the population of England and Wales.

In terms of the impact of economic well-being on voting patterns, research by Adler & Ansell identified a strong inverse link between higher support for Brexit vote in 2016 and regional house prices11. This showed that higher house price inflation was a strong proxy for macroeconomic prosperity within a given region, resulting in a lower sense of economic grievance and appeal for populist political messages. The OECD notes that homes are typically the most important asset for households, and that regional variations in house prices can therefore serve as key indicators of economic inequality and public grievance12. Indeed, Sierminska et al have shown that wealth inequality in most European countries is far higher than income inequality13.

Secondly, the period 2010-2015 saw significant government cuts in discretionary government spending impacting public services in many countries. Research by Gabriel et al looking at selected European countries found that a reduction in regional public spending of 1% led to a corresponding 3% increase in the vote share of extreme parties14. This suggested that austerity has been a key driver of rising support for populist parties in continental Europe. In addition, Fetzer has shown that the outcome of EU referendum was significantly influenced by austerity15.

The third factor is immigration, which is a key aspect of the “cultural backlash thesis”. Gidron and Hall suggest that voters attracted to populist or radical right-wing parties for cultural reasons, particularly antipathy towards immigration16.

UK immigration has gone through several phases in recent decades. According to ONS data, immigration into the UK rose sharply from 1998 and again in 2004 with accession of former communist Eastern-Bloc states in the European Union17. Portes has documented how a slowdown then occurred after the Brexit referendum in 2016, followed by the introduction of the new post-Brexit immigration system by the UK government in 202018. This triggered a spike in immigration from non-EU countries. Given this rise in real immigration into the UK, the issue has often been put forward as the reason for growth of support for populist parties.

Kaufman has modelled support for UKIP at the 2014 European Parliament election using both real and survey-based immigration data19. In addition, surveys conducted of voters of UKIP by Lord Ashcroft in 2014 and Reform voters by M. Smith in 2024, consistently rank immigration as the most important issue for voters supporting these parties20,21.

Norris (2018) has shown how cultural backlash centred around immigration builds upon underlying economic grievances in explaining support for Brexit referendum. Likewise, Abreu (2020) used multivariate analysis to show that economic drivers account for more variation in the Brexit vote than cultural factors22,23.

Limitations of Existing Research

While extensive research on the rise of populism has been conducted, there are several limitations and hence gaps in this body of work.

Firstly, Adler & Ansell have modelled the Brexit voteusing house price data, as a proxy for prosperity,and Fetzer and Kaufmann have modelled the rise in the UKIP vote using austerity cuts to public expenditure andimmigration data, respectively11,24,25. However, these factors have been explored in isolation in these studies. They therefore lack the perspective a comparison of their relative importance coming from the same multivariate model. The closest seems to be the multivariate analysis conducted by Abreu (2020), but this was on the Brexit vote rather than the rise of UKIP/Reform UK26.

Secondly, this research has tended to end at the 2015 General Election or 2016 Brexit vote, and so misses the period up until and including the last UK General Election in 2024 when Reform UK grew the populist vote further, building upon the past success for UKIP. As such, this longer-term view has not been captured.

Finally, most of the work around the impact of immigration, though not by Kaufmann, has been survey based.This includes opinion polling by Lord Ashcroft (2014) and YouGov (2024).20,21.This research relies on voters reporting their own views and reasonings, with the risk of over-rationalisation. As such, those UKIP/Reform supporters already influenced by the messaging of populist parties regarding the issue of immigration may not be accurately reflecting the underlying structural forces in society driving their grievances.

Objectives of the Study

This study attempts to address some of the limitations outlined in the existing research by analysing the differences in the increase in voting shares for UKIP/Reform at UK general elections between 2010 and 2024, as observed across the 10 ITL1 regions of England and Wales, using a single common model.

Furthermore, rather than relying on survey-based measures, it seeks to use objective data as proxies for regional changes over time in prosperity, austerity, and immigration to avoid any issues of voters over-rationalising the reasons for voting for UKIP/Reform.

Finally, by using longitudinal analysis between the 2010 and 2024 general elections, it aims to capture the long-term drivers, while accounting for some unobserved fixed effects between regions (e.g. historically rooted cultural context), which are unlikely to have changed over time in relative terms.

By employing this methodological approach, the study seeks to address the following specific research questions:

- What is the relative importance of prosperity (house price change), austerity (cuts in public expenditure) and immigration (share of foreign-born population) in explaining the rise in populist voting between 2010 and 2024, using a comparable frame of reference?

It is hypothesised that prosperity, as measured by house prices, is the most important driver. This is because austerity is expected to have been a salient issue only during the more limited timeframe of the cuts (2010-2015), with less relevance beyond that. With respect to immigration, Kaufmann (2017) showed that real immigration was less important than attitudes towards immigration in driving UKIP vote share over time25.

- Do increasing house prices reduce the tendency to vote for UKIP/Reform UK?

It is hypothesised that the more prosperous ITL1 regions, with higher increases in house prices, will have seen lower growth in populist voting i.e. an inverse relationship between price growth and populist voting.

- Do the real immigration levels recorded in census data align with the high importance that UKIP/Reform voters attach to the issue in survey responses once prosperity and austerity are considered?

It is hypothesised that objective immigration levels will have weaker explanatory power than prosperity once economic factors are taken into account.

- Did austerity cuts in discretionary government spending during the period 2010-2015, which impacted the funding of public services, play an observable role in the rise of support for UKIP/Reform UK?

It is hypothesised that lower relative levels of prosperity have had a stronger long-term effect on populist voting than austerity-related cuts in public spending.

Methodology

Data Sources and Variables

This study uses data covering the 10 major socio-economic regions of England and Wales, namely the ITL1 regions defined by the Office for National Statistics. These were the East Midlands, the East of England, London, the North East, the North West, the South East, the South West, the West Midlands, Yorkshire and the Humber and Wales. Scotland and Northern Ireland were excluded from the analysis because of their different party-political landscapes, where local nationalist parties play a key role and hence UKIP/Reform UK have not fielded many, if any, candidates at UK general elections.

The outcome variable modelled was the increase in vote share for UKIP/Reform by region over the period 2010-2024.

This change in vote share was calculated from constituency-level data at the general elections of 2010, 2015, and 2024, and was sourced from the House of Commons Library. The raw data comprised of the votes cast for UKIP/Reform UK and total valid votes cast across all parties. These measures were then aggregated into constituency-level into data. Finally, the UKIP/Reform UK’s share of the total valid votes cast at the 10 ITL1 regional levels was computed as a percentage for each of the three general elections, along with the changes over time between each election.

Vote shares for UKIP (later replaced by Reform UK) serve as a viable proxy for the overall strength of support for populism in England and Wales. This is not only because of the high level of support achieved by the party, but also the fact that it fielded a full slate of candidates in the constituencies of the 10 ITL1 regions analysed. During the period analysed, other populist or extreme movements such as the Workers’ Party or British National Party have achieved only very small vote shares. Moreover, these parties ran candidates in a few constituencies, and so their inclusion would have skewed the analysis when comparing their support between regions.

Three independent variables, each a respective proxy for the three hypothesized driving factors, prosperity, austerity, and immigration, were analysed to explore their relationship with changes in populist voting behaviour.

Firstly, for changes in regional prosperity and economic health, average house prices in pounds sterling (£) by ITL1 region during the period of 2010–2024 sourced from the UK Government Land Registry were used as a proxy. This choice was strongly supported by the analysis link established by Adler and Ansell between regional house prices and the voting patterns in the Brexit referendum of 201611. House prices are tied to the macroeconomic performance of a given region and are also a measure that connects strongly to the lives of individual voters, as it is frequently their largest household asset. This study therefore sought to extend this finding by investigating a possible link between changes in house prices over the long-term and changes in vote shares for UKIP/Reform.

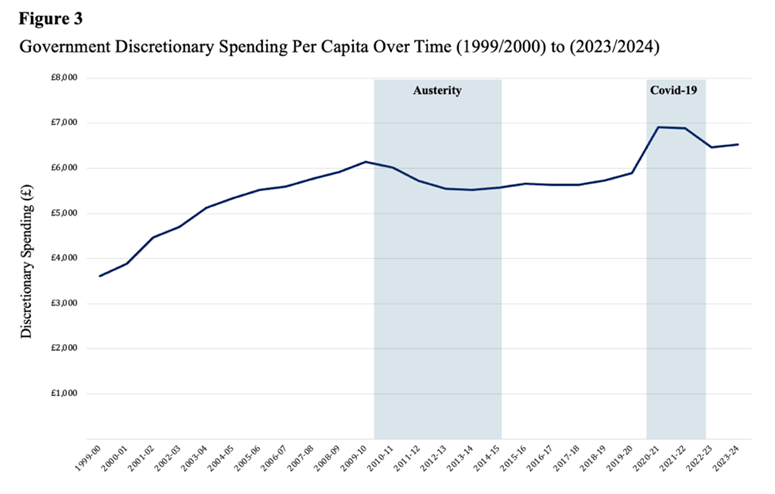

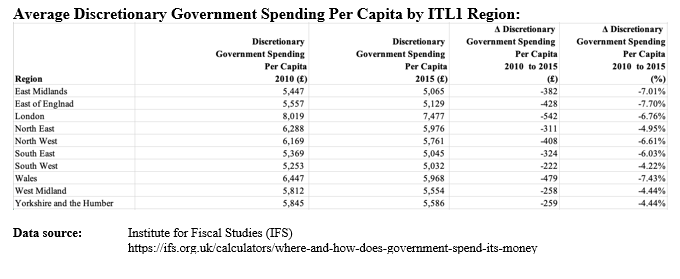

Secondly, changes in the government’s discretionary spending in pounds sterling (£) per head at the ITL1 regional level has been used as a proxy for austerity cuts. The period used was 2010-2015, as this corresponds to the period of reduction in spending, generally considered to be the austerity period in the UK (Figure 3). This was followed by a slight reversal of the cuts from 2016, and then by a sharp rise in discretionary spending during the Covid-19 period from 2020. This data was sourced from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a UK-based economics research institute, which in turn sourced it from the UK’s HM Treasury and Office for National Statistics (ONS).

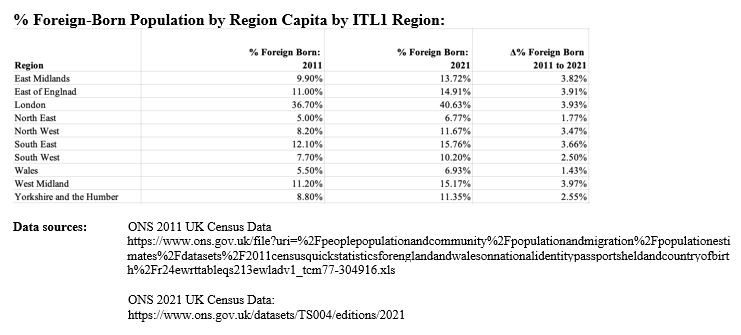

Finally, the percentage of the foreign-born population at the regional level, as self-reported in the UK census data has been used as a proxy for immigration during the period 2011 to 2021. The time period for computing the growth in immigration at the regional level was determined by the years in which the UK census was conducted i.e. 2011 and 2021.The data was available directly at the ITL1 regional level and sourced from the ONS.

Statistical Methods

At the initial stage of data analysis, standardised Z-scores were computed for the three independent variables to assess regional variations, and a correlation matrix produced to ensure that the predictors were not excessively collinear.

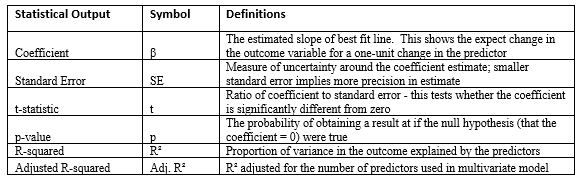

Bivariate OLS linear regression models were then used to investigate the relationships between each predictor, namely regional changes over time in house prices, government discretionary spending and the percentage foreign-born population, and the increase in support for UKIP/Reform at the regional level. For each bivariate regression, the following statistics were reported: coefficient, standard error, t-statistic, p-value, R-squared.

A multivariate OLS linear regression model was subsequently run to estimate the importance of all three predictors, when considered together. The same set of statistics reported for the bivariate regressions were generated, along with an overall model-fit measures (R-squared and adjusted R-squared).

Results

Data Exploration

Figure 4 shows “Z-scores” for the three independent variables which were measured on different scales. The values indicate how many standard deviations each regional measure was above or below the overall average for the variable. The plots show how the three independent variables had higher or lower values in different regions.

Also, the fact that none of the lines plotted was flat, shows how differentiation existed between the regions and further supported the choice to include these measures as independent variables to test via the regression analyses.

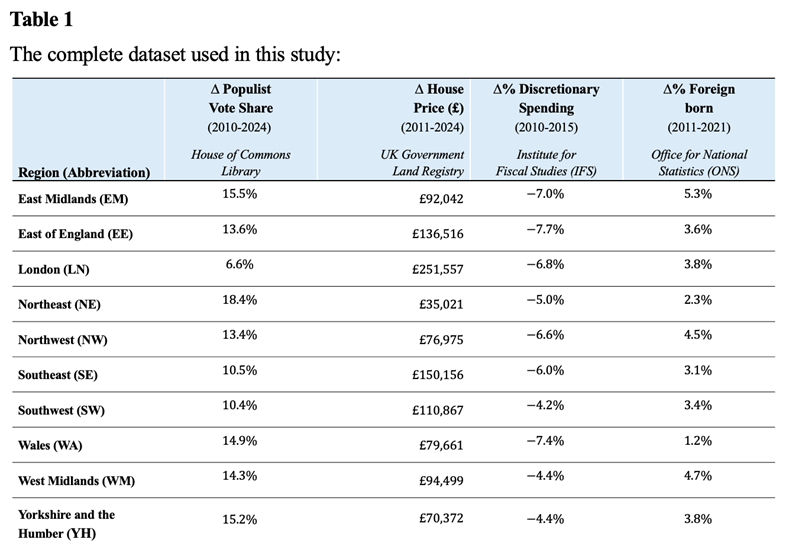

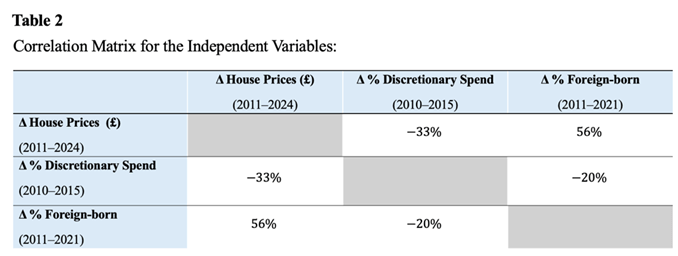

The correlations between the three independent variables analysed are shown in Table 2.

Overall, collinearity was low, again suggesting that the three measures were good candidates as independent variables, since they were not seen to be proxies for some common deeper factor. There was some moderate positive correlation between house prices and immigration, likely due to immigrants being drawn to more prosperous areas such as London and the South East, and less drawn towards less prosperous areas such as the North East and Wales.

Data Models

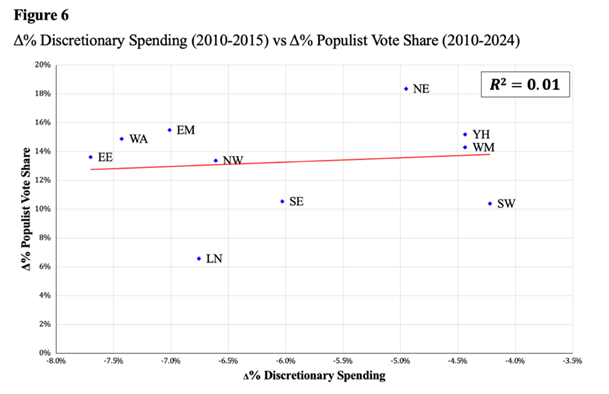

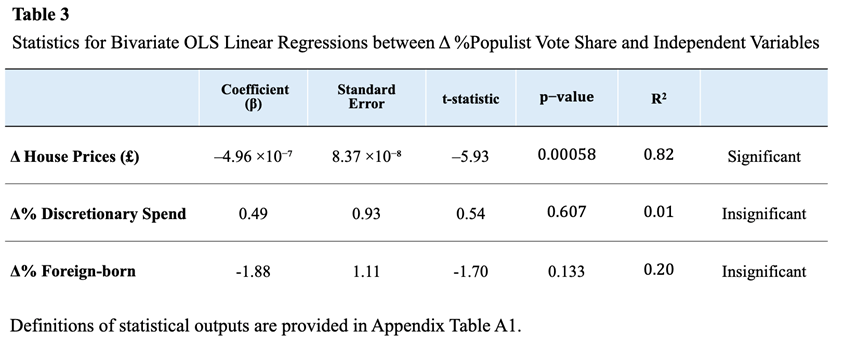

Bivariate linear regression analysis was run between the dependent variable, changes in populist voter share (2010–2024) and each of the three predictor variables in turn.

The abbreviations used for each region are provided in Table 1.

The bivariate regression statistics are summarised in Table 3.

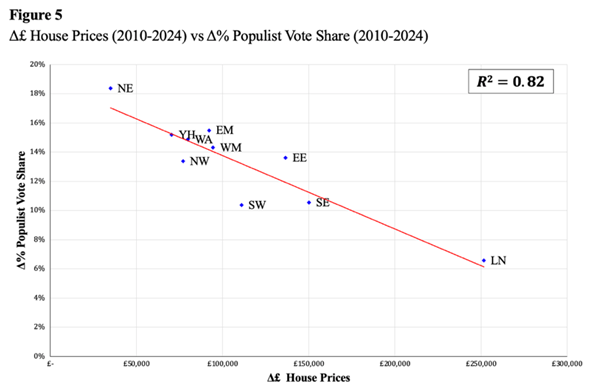

Changes in house prices (2010–2024) across the 10 regions were seen to be negatively correlated with increasing populist vote share i.e. as house prices increase in a region, the growth of populist voting over time in that region tended to be lower. The R2 of 0.82 and p-value of 0.00058 show this relationship to be statistically significant.

In contrast, the regression for discretionary spending showed an R2 of only 0.01, which was not significant. A second regression was conducted using the vote change over the period when austerity cuts occurred i.e. using the results from the 2010 and 2015 general elections, rather than the change between 2010 and 2024 elections. This increased the R2 slightly but only to a level of 0.03, which was also not statistically significant.

Finally, the regression for change in % foreign-born also yielded an R2 of only 0.20, which was not statistically significant.

Table 4 shows the results from the OLS multivariate regression analysis which was run using the three predictor variables to analyse their relative importance, when included in the same model.

In the multivariate model, only the change in house prices (β = –0.000072, p=0.0065) is statistically significant when the three predictors are modelled together. The other two predictors, change in % discretionary spending (β = –536, p=0.192) and change in % foreign-born (β = +0.551, p=0.294) were not statistically significant once changes in house prices were controlled for.

The unit changes for each predictor were interpreted as follows based on the multivariate model.

A one-standard-deviation increase in regional house prices (£59,700) predicted a 4.3% decrease in populist vote share, holding other factors constant, and this was statistically significant.

By contrast, a one-standard-deviation increase in discretionary spending (1.3%) predicted a 0.7% decrease in populist vote share, and a one-standard-deviation increase in the foreign-born share (2.2%) predicted a 1.2% increase in populist vote share. However, neither of these effects was statistically significant. Of the three predictors, only house prices had a statistically significant effect, with greater increases in house prices, meaning higher prosperity, being associated with lower growth in populist vote share over the 14-year period.

Discussion

The regression analysis used in this study showed a clear negative link between increases in house prices (the proxy for prosperity) and populist voting across the ITL1 regions, and this was statistically significant. This confirms the finding of Adler & Ansell when studying the Brexit vote11.

Other potential proxies for prosperity, such as median wealth, unemployment, and poverty rates, were also explored during the initial stages of this study, but consistent regional data across the 2010–2024 period were harder to obtain, and the available measures showed weaker explanatory power than house prices. For this reason, house prices were retained as the primary proxy for prosperity. House prices are macroeconomically significant, as they are deeply intertwined with the health of the economy as they both shape and reflect it. Moreover, as homes are the most valuable assets for most households, it was unsurprising that rising house values were seen to be so closely tied to voting behaviour12.

In comparison with prosperity, neither of the other two independent variables, discretionary spending changes (austerity) or growth in the percentage foreign-born (immigration), showed any significant correlation with changes in populist voting shares.

So, while Fetzer found austerity to have influenced the rising UKIP vote up to 2015, this study did not find a longer-term effect on populist voting extending to 2025, especially when prosperity was accounted for, as in this study design27.

Regarding regional immigration levels, Kaufmann similarly found that using real immigration data had limited explanatory power for UKIP support, whereas attitudes and perceptions of immigration were much more influential19. Opinion polls consistently show that populist voters see the issue as being important. This suggests that the experience of actual immigration was not the issue driving the observed rise in populism. Rather it is voters’ perceptions, as informed by populist parties like UKIP or Reform UK, which were able to amplify a sense of grievance around the topic.

However, this analysis shows that the more fundamental driver of grievance is the sense of economic exclusion in less prosperous regions. Clearly, voters in many regions, such as the North East of England and Wales, have felt left behind compared with those living in London and the South East, and this has generated resentment that populists have taken advantage of this discontent by attributing the blame to immigration. In the debate of economic grievances (prosperity, austerity) vs cultural backlash (immigration), this study suggests that economic grievances are the underlying structural driver of increased rates of populist voting. The results support the findings of Norris (2018) resentment of immigration builds upon underlying economic grievances, but also Abreu (2020) that economic drivers accounted for more variation in the Brexit vote than cultural factors22,28.

Cultural perceptions of immigration are important in the populist narrative, but in the UK case they appear to be rooted in, and amplified by, underlying economic inequalities. Political disaffection with mainstream parties, while not directly tested here, are also likely to have interacted with these factors, helping to channel grievances into support for UKIP and Reform UK.

Limitations of this study

In drawing conclusions from these findings, one important limitation is that although the adjusted R2 observed in the multivariate model was strong at 84%, this study covered only 10 ITL1 regions and consequently was based upon only 10 data points. Therefore, it is best to be cautious in drawing definitive or over-general conclusions.

Also, in considering the link between regional house prices to populist voting, correlation does not necessarily imply causation.

Moreover, the mechanism driving voting is likely to be more complex, involving cultural factors. For instance, exposure to political messaging, levels of education, and perceptions of immigration likely play a role and within the basic context of regional economic grievances highlighted by this study.

To a degree, it is reasonable to expect that confounding factors, may be accounted for as unobserved fixed effects in this longitudinal study design. However, it is possible that if there are differences in terms of the factors such as age distribution, education levels or exposure to social media between ITL1 regions, theoretically these could impact voting patterns.

Future Research

The results of this study point towards areas of future research that could build upon these findings and provide additional understanding.

Having established that regional levels of prosperity are a key driver of the growth of populism, while changes in real immigration are not, it would be insightful to introduce survey-based attitudinal data on immigration at the ITL1 regional level into the multivariate model. This data is available over time from the British Election Study. In addition, hierarchical modelling such as Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) could be used to determine the causality of different levels of prosperity driving concerns on immigration and populist voting. The challenge here would be having only 10 data points corresponding to the ITL1 regions, so these approaches would benefit from larger datasets.

One way in which the dataset could be greatly expanded would be by repeating the study at a more granular level, such as at the local authority (LA) level. The 10 ITL1 regions of England and Wales can be disaggregated into 339 local authorities. Voting, house prices (prosperity) and % foreign-born (immigration) data are readily available at the LA level, however, central government discretionary spending (austerity) data or survey-based attitudes towards immigration would not be. Nevertheless, a more robust dataset could solidify the core finding that house prices, used as a proxy for regional prosperity, are a strong predictor of the growth of populist voting, and that this is a more important driver than real immigration.

Conclusion

This study examined the drivers of populist voting across the ten ITL1 regions of England and Wales between 2010 and 2024. The analysis found a robust and statistically significant link between increases in house prices, as a proxy for regional prosperity, and lower levels of populist voting. By contrast, neither regional immigration levels nor cuts in discretionary public spending showed significant long-term effects once prosperity was accounted for.

These findings extend prior research on Brexit voting which used house prices (Adler & Ansell, 2019), austerity cuts (Fetzer, 2019) and immigration data (Kaufmann, 2017) by providing a longer-term, regionally comparative analysis between the general elections of 2010 and 202429),27,30). The contribution of this study is to place prosperity, austerity, and immigration side by side within a single multivariate framework. From the review of the literature undertaken, no study has examined these three variables together over multiple UK general elections, using objective, regional data.

The results show that geographical differences in prosperity are the strongest predictor of the rise of populism in the UK and are more significant than actual levels of immigration into the ITL1 regions. This suggests that the cultural importance of immigration, as consistently reflected in surveys of populist voters for parties such as UKIP and Reform UK, may be rooted in underlying economic grievances which the parties have successfully leveraged.

This research was limited by its use of only 10 regions. Future research could build upon these findings by using more granular datasets, such as at the local authority level, and incorporating survey-based data concerning immigration. This would both increase the robustness of the research and potentially allow for investigation of the interactions between regional levels of prosperity, attitudes towards immigration, and populist voting.

Appendix

1) Raw Data

2) Statistical Outputs and Definitions

Table A1

Statistical outputs and definitions.

References

- M. Rooduijn, A.L.P. Pirro, D. Halikiopoulou, C. Froio, S. Van Kessel, S.L. de Lange, C. Mudde, P. Taggart. The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC). The British Journal of Political Science 54 Issue 3, 969–978 (2024). [↩]

- E. Piper, A. Macaskill. New-look populist Reform party could reshape the UK political landscape. Reuters (2024). Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/new-look-populist-reform-party-could-reshape-uk-political-landscape-2025-04-293 [↩]

- Poll of Polls. United Kingdom – Parliament voting intention. Politico (2025). Retrieved from: https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/united-kingdom [↩] [↩]

- General Election 2015. Briefing Paper Number CBP7186 House of Commons Library (2015). Retrieved from: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7186/CBP-7186.pdf [↩]

- 2024 general election: Performance of Reform and the Greens. House of Commons Library (2024). Retrieved from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/2024-general-election-performance-of-reform-and-the-greens [↩]

- BBC Data Journalism team. Local elections 2025 in maps and charts. BBC News (2025). Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cd925jk27k0o [↩] [↩]

- C. Haußmann, T. Rüttenauer. Material deprivation and the Brexit referendum: a spatial multilevel analysis of the interplay between individual and regional deprivation. European Sociological Review Vol 40 Issue 3, 479–492 (2024 [↩]

- S. Rudkin, L. Barros, P. Dłotko, W. Qiu. An economic topology of the Brexit voteRegional Studies Vol 58, Issue 3 (2024). [↩]

- J. Smith. The Macroeconomic Policy Outlook. Resolution Foundation Macro Economic Unit. Quarterly Briefing Q2 (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/06/Macro-Outlook-Q2-2021.pdf [↩]

- J. Riley, R. Chote. Crisis and consolidation in the public finances. Office for Budget Responsibility (2014). Retrieved from https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/WorkingPaper7a.pdf [↩]

- D. Adler, B. Ansell. Housing and populism. West European Politics 43(2) 344-365 (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- OECD Housing Policy Toolkit https://housingpolicytoolkit.oecd.org/4.H_invest.html [↩] [↩]

- E. Sierminska, A. Brandolini, T.M. Smeeding. The Luxembourg Wealth Study – A cross-country comparable database for household wealth research. Journal of Economic Inequality 4(3) 375–383 (2006). [↩]

- R.D. Gabriel, M. Klein, A.S. Pessoa, The Political Costs of Austerity. Stockholm: Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series No. 418 (2022). [↩]

- Thiemo Fetzer. Did Austerity Cause Brexit? American Economic Review Vol. 109 #11, 3849–86 (2019), [↩]

- N. Gidron, P. A. Hall. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right. British Journal of Sociology 68 S1, 57–84 (2017). [↩]

- International migration: a recent history. Office for National Statistics (2015) Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/population andmigration/internationalmigration/articles/internationalmigrationarecenthistory/2015-01-15 [↩]

- J. Portes. Unintended Consequences? The Changing Composition of Immigration to the United Kingdom After Brexit. National Institute Economic Review 268 63–78. (2024). [↩]

- E. Kaufman. Levels or Changes?: Ethnic Context, Immigration, and the UK Independence Party Vote. Electoral Studies 48 57-69 (2023). [↩] [↩]

- Lord Ashcroft. Post-European Election Poll. Lord Ashcroft Polls (2014). Retrieved from: https://lordashcroftpolls.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Lord-Ashcroft-Polls-Post-Euro-Election-Poll-Summary-May-2014.pdf [↩] [↩]

- M. Smith. General election 2024: what are the most important issues for voters? YouGov (2024). Retrieved from: https://yougov.co.uk/politics/articles/49594-general-election-2024-what-are-the-most-important-issues-for-voters [↩] [↩]

- P. Norris. Understanding Brexit: Cultural Resentment Versus Economic Grievance Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series (2018). [↩] [↩]

- M Abreu, Ö. Öner. Disentangling the Brexit Vote: The Role of Economic, Social and Institutional Drivers. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. Vol 52 7, 1434-1456 (2020). [↩]

- Thiemo Fetzer. Did Austerity Cause Brexit? American Economic Review Vol. 109 #11,

3849–86 (2019). [↩]

- E. Kaufman. Levels or Changes?: Ethnic Context, Immigration, and the UK Independence Party Vote. Electoral Studies 48 57-69 (2023). [↩] [↩]

- M Abreu, Ö. Öner. Disentangling the Brexit Vote: The Role of Economic, Social and Institutional Drivers. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. Vol 52 7, 1434-1456 (2020). [↩]

- Thiemo Fetzer. Did Austerity Cause Brexit? American Economic Review Vol. 109 #11, 3849–86 (2019). [↩] [↩]

- M Abreu, Ö. Öner. Disentangling the Brexit Vote: The Role of Economic, Social and Institutional Drivers. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. Vol 52 7, 1434-1456 (2020). [↩]

- D. Adler, B. Ansell. Housing and populism. West European Politics 43(2) 344-365 (2019 [↩]

- E. Kaufman. Levels or Changes?: Ethnic Context, Immigration, and the UK Independence Party Vote. Electoral Studies 48 57-69 (2023 [↩]