Abstract

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex psychiatric illnesses that remain underrepresented in qualitative research, particularly regarding the voices of those directly affected. This study aimed to explore how individuals with EDs describe their lived experiences across illness onset, stigma, and recovery. Sixty anonymized narratives were collected from participants aged 13-65 who self-identified as having a current or past ED. Recruitment occurred through online ED-related communities, and responses were gathered through an open ended survey. A grounded theory approach guided inductive coding and thematic analysis. Findings revealed three core themes. First, participants described early exposure to body criticism and gradual symptom onset during adolescence, often perceiving EDs as a means of control. Second, public misconceptions and stereotypes were viewed as barriers to empathy and support, while family and digital influences had mixed impacts. Third, recovery was characterized as non-linear, with therapy and peer support reported as especially beneficial. These narratives underscore the importance of trauma informed and person centered care models and call for more accurate public discourse to reduce stigma and support recovery.

Keywords: Eating Disorders (EDs), Lived Experience, Disordered Eating, Body Image, Trauma and EDs, Digital Influence on EDs

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs), including anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), and other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED), are multifactorial psychiatric conditions characterized by pathological eating behaviors and distorted body image1. They are associated with high morbidity and mortality and affect millions worldwide2. While epidemiological and biological studies have examined prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and neurobiological mechanisms3, the lived experience of individuals with EDs remains underrepresented in clinical literature4.

Previous qualitative work has begun to document these perspectives. For instance, Tierney explored how individuals with AN describe their illness as both identity-shaping and socially isolating5. Conti et al. highlighted how stigma and misconceptions perpetuate barriers to care6, while Patching and Lawler examined narratives of recovery as non-linear, marked by relapses and shifting definitions of “wellness”7. Despite these contributions, most studies are limited by small, region-specific samples or a focus on only one subtype of ED, leaving gaps in understanding the diversity of lived experiences across diagnoses and cultural contexts8.

Furthermore, existing literature disproportionately emphasizes AN, leaving BED, ARFID, and OSFED comparatively understudied9. Most qualitative work also focuses narrowly on young women, excluding men, nonbinary individuals, and older adults10. Finally, few studies employ cross-age analysis, which limits insight into how narratives and recovery trajectories shift over the lifespan11. These methodological gaps highlight the need for more inclusive, comparative research across ED subtypes, genders, and age groups.

Understanding these personal narratives is essential for developing patient-centered treatment models and more responsive public health strategies12. Current knowledge often relies on clinical observation and quantitative data, which, though valuable, cannot fully capture the subjective struggles, contributing factors, and perceptions of support systems described by those directly affected13. Without these perspectives, interventions risk becoming overly generalized and may fail to address harmful public misconceptions that contribute to stigma and hinder recovery14.

The specific objectives of this study are: (1) to identify common themes in individuals’ accounts regarding the onset and development of their eating disorders; (2) to explore participants’ perceptions of public misconceptions about EDs and their impact; (3) to assess the types of support systems perceived as helpful versus unhelpful in recovery; and (4) to analyze the non-linear nature of the recovery journey as described by participants.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a qualitative and descriptive research design, using a grounded theory approach to thematic analysis. This methodology was chosen to ensure that themes emerged inductively from participants’ lived experiences rather than being constrained by predefined categories.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited through publicly accessible online communities focused on eating disorders, including discussion forums and social media groups. Recruitment posts were shared only with permission from group moderators when required. Participation was entirely voluntary, and all individuals provided informed consent prior to completing the survey. No identifying information was collected, and anonymity was preserved. Eligibility criteria included being between 13 and 65 years old and willing to reflect on personal experiences in an open-response format. A total of 60 unique responses were collected. Demographic information such as gender, specific diagnosis, and self-reported recovery status was gathered to support subgroup analyses. The sample ranged in age from 13 to 62 (M = 27.4, SD = 9.1), with 82% identifying as female, 10% male, and 8% non-binary or gender diverse. In terms of diagnoses, 45% reported anorexia nervosa, 28% bulimia nervosa, 17% binge-eating disorder, and 10% other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED). Regarding recovery status, 38% described themselves as in recovery, 42% as currently struggling, and 20% as partially recovered.

Data Collection

Data were collected via a Google Form distributed online between May 1 and June 10, 2025. The form included open-ended questions that invited participants to describe the onset and progression of their eating disorders, perceived public misconceptions, experiences with support systems such as family, friends, therapy, and online communities, and factors influencing recovery. The open-response format provided participants with the freedom to share their stories in their own words and at their own pace.

Data Analysis

Thematic coding followed grounded theory principles, an approach in which themes and patterns are allowed to emerge directly from the data rather than being imposed beforehand. This inductive method was chosen to ensure that participants’ lived experiences guided the development of codes and categories. Responses were reviewed repeatedly to ensure immersion, and initial codes capturing recurring ideas, phrases, and concepts were generated. These codes were then organized into broader categories and refined into overarching themes through an iterative process, with NVivo software used to manage the coding framework and generate frequency reports. Thematic saturation was reached after approximately 50 responses, with the remaining 10 confirming and refining categories. As the sole coder, reliability was enhanced through multiple coding rounds, careful rereading, and maintaining a detailed audit trail of analytic decisions. Reflexivity was addressed through journaling, in which the researcher documented personal assumptions and perspectives related to eating disorders, helping to minimize potential bias and enhance transparency in the development of themes.

Ethical Considerations

All participants provided informed consent, and for those under 18, parental or guardian consent was obtained where applicable. Anonymity was maintained by excluding any personally identifiable information, and all data were securely stored. Participation was voluntary, and individuals retained the option to withdraw at any point without penalty.

Results

Demographics and Onset

A total of 60 participants were included in the study. The majority described the onset of their eating disorder as a gradual process, which often emerged in early adolescence or even late childhood. Their narratives reveal a covert transformation from seemingly benign habits, such as calorie counting, into obsessive patterns of thought and behavior.

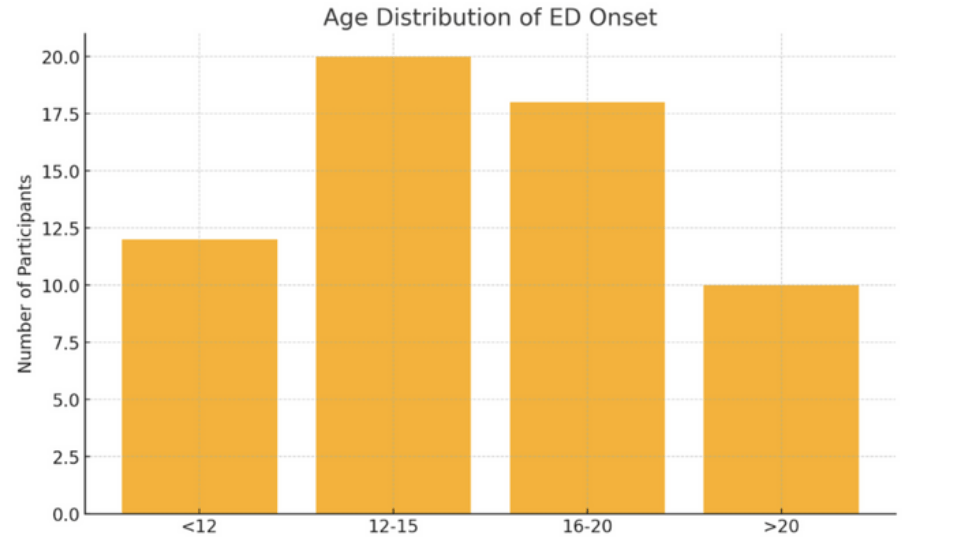

Figure 1 offers a clear visualization of the varying ages at which eating disorders manifest among participants. The adolescent years appear to be a critical period for ED development, with the 12-15 age group showing the highest incidence, involving approximately 20 participants. This is closely followed by the 16-20 age group, with around 18 participants. While less frequent, early onset before age 12 still accounts for a significant number, with approximately 12 participants. The data also indicates that onset in adulthood, specifically after 20 years old, is the least common among the surveyed groups.

One 16-year-old participant succinctly captured the initial confusion, stating, “I was diagnosed with anorexia at 9 or 10, after starting at 8, and hadn’t a clue it existed. I thought I’d invented it.”

Participant Narratives and Themes

Respondents consistently highlighted the centrality of control, often explaining that their disorder provided a false sense of stability amid emotional chaos. For example, one individual reported that it gave them “strength and confidence that nothing else did,” while another described disordered eating as “the only method that always worked,” reinforcing the instrumental role these behaviors play in managing distress.

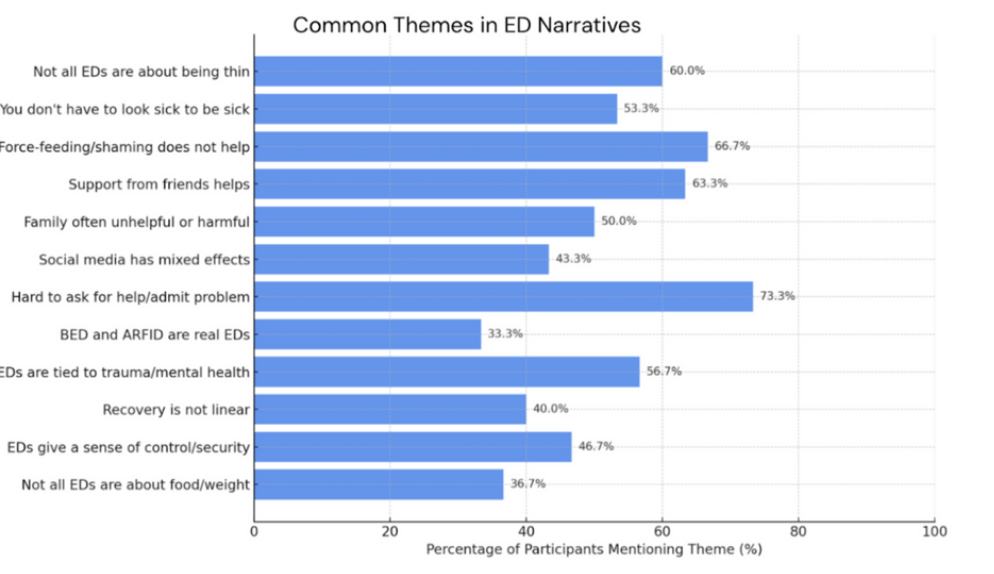

Figure 2 shows a compelling overview of the shared experiences and perspectives of individuals navigating eating disorders. A critical insight is the overwhelming difficulty in help-seeking, with the majority of participants identifying challenges in admitting their problem.

The narratives also strongly refute common misconceptions and unhelpful interventions. A large number of participants reported that force-feeding or shaming is ineffective, and many emphasized that eating disorders are not solely driven by a desire to be thin.

The importance of social support is evident, with many participants highlighting the positive impact of friends. In contrast, a significant portion found family involvement to be unhelpful or even detrimental. The narratives also reveal the complex psychological underpinnings of eating disorders, with many participants linking their experiences to trauma or other mental health issues and a notable number indicating that their disorder provided a sense of control or security. Many participants identified early life experiences, especially trauma and cultural pressures, as key contributors. Some recalled specific triggering events, such as being called “fat” by a grandparent at the age of four or enduring chronic illness. A 16-year-old vividly recalled, “When I was around 4-5 and my grandad used to call me fat as a joke and I started crying abt it one day and ever since then it’s just gotten worse and worse.”

Misconceptions and ED Types

Participants also reported profound frustration with common misconceptions about eating disorders. Many noted that they were dismissed for not being “thin enough” or that their experiences were invalidated because they did not fit the stereotypical image of anorexia nervosa.

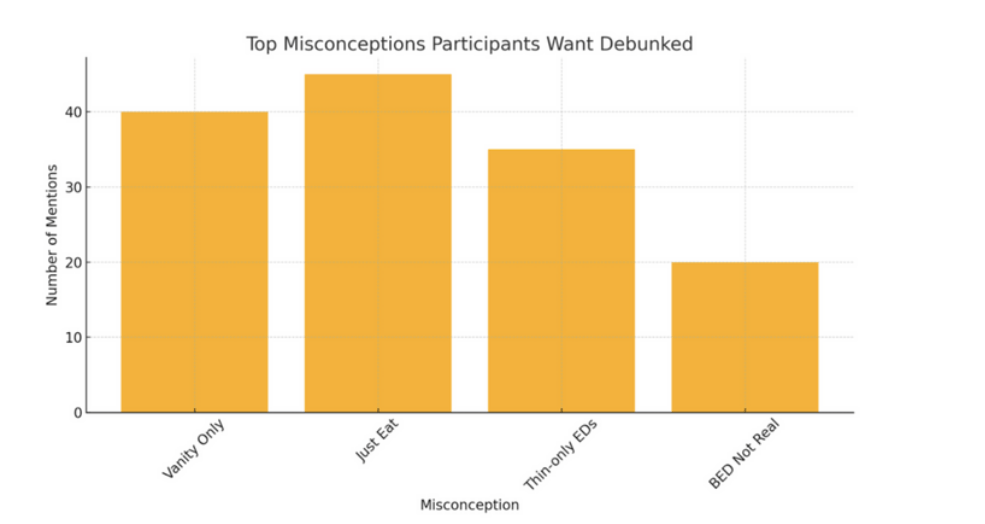

Figure 3 highlights prevalent misconceptions that individuals wish to see corrected. The misconception “Just Eat” garnered the highest number of mentions (over 40), suggesting a widespread societal belief that recovery from an eating disorder is simply a matter of willpower. Closely following, “Vanity Only” (40 mentions) underscores the persistent misconception that eating disorders are solely superficial concerns. The substantial number of mentions for “Thin-only EDs” (approximately 35) reveals the pervasive stereotype that eating disorders exclusively affect individuals who are visibly underweight. Lastly, the significant number of participants wanting “BED Not Real” debunked (around 20 mentions) points to a critical lack of awareness and validation for Binge Eating Disorder.

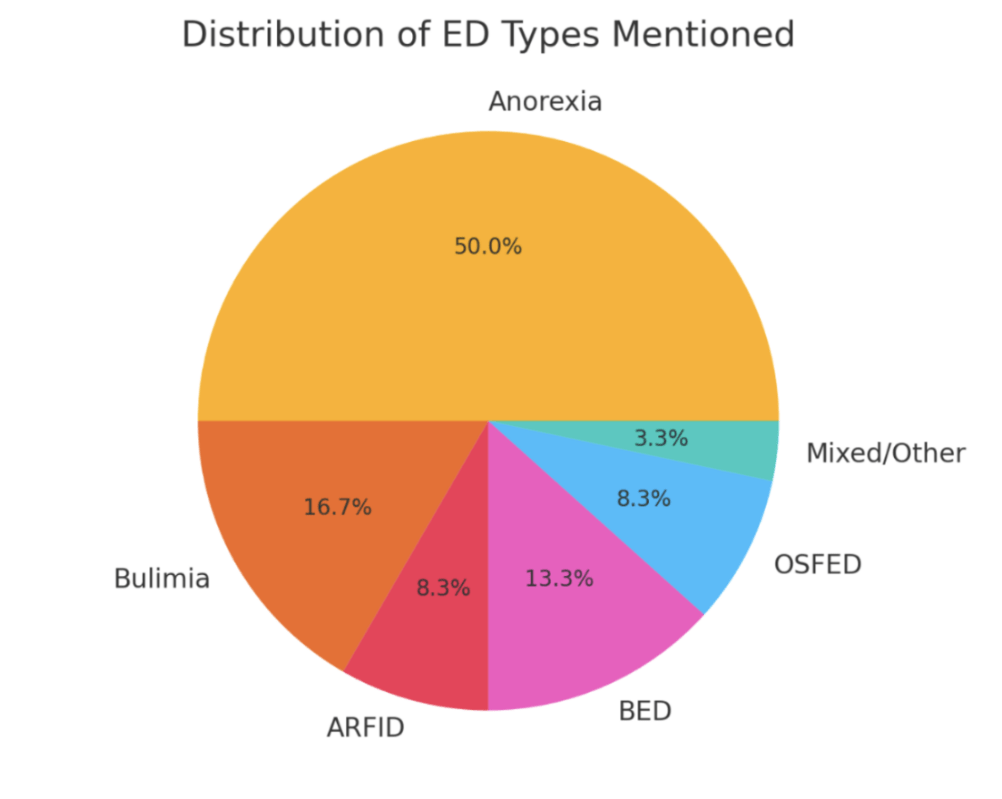

Figure 4 displays the distribution of different eating disorder (ED) types mentioned by participants. Unsurprisingly, Anorexia constituted the largest proportion of mentions. Bulimia was the second most common. BED and ARFID were also frequently mentioned, while OSFED and “Mixed/Other” comprised the smallest categories.

Disorders such as BED and ARFID were especially subject to mischaracterization, often trivialized or conflated with simple “picky eating.” A 16-year-old with BED expressed, “I wish people understood that BED is also an eating disorder. So many times I see people say it’s not an eating disorder bc you don’t starve yourself.” Similarly, a 17-year-old with ARFID lamented, “As someone with ARFID I wish people would be aware that no I cannot just eat it, I know it’s a pain it’s a pain for me a well.”

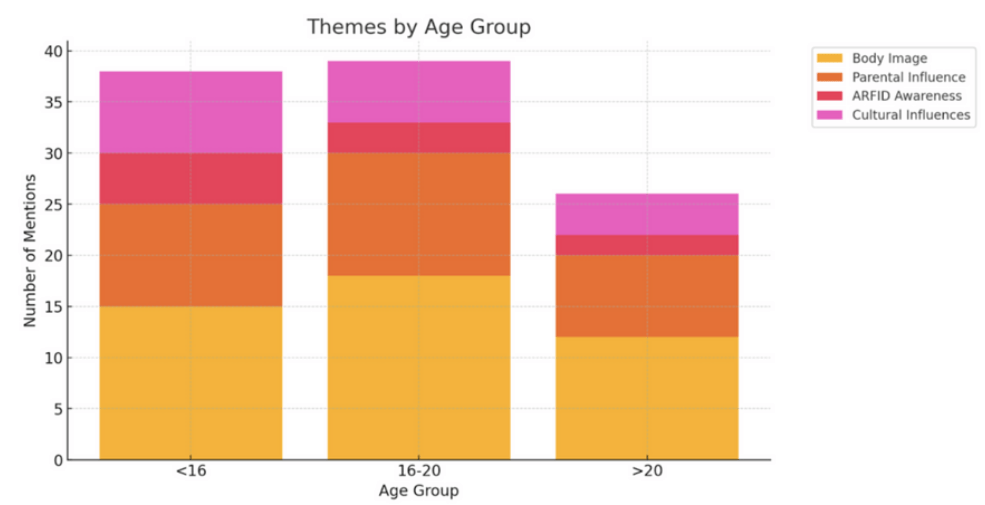

As seen in Figure 5, body image emerges as the most dominant theme, particularly pronounced in the 16-20 age group where it contributes significantly to the highest overall number of mentions. Although present across all groups, its prevalence notably decreases in the “>20” age category.

Peer and digital environments also emerged as double-edged influences. A 13 year old shared, “Oddly enough… I found comfort in kpop and watching the vlogs of my favorite idols… It was a nice distraction,” while a 17-year-old observed that “strangers on the internet could be both the most helpful and harmful.”

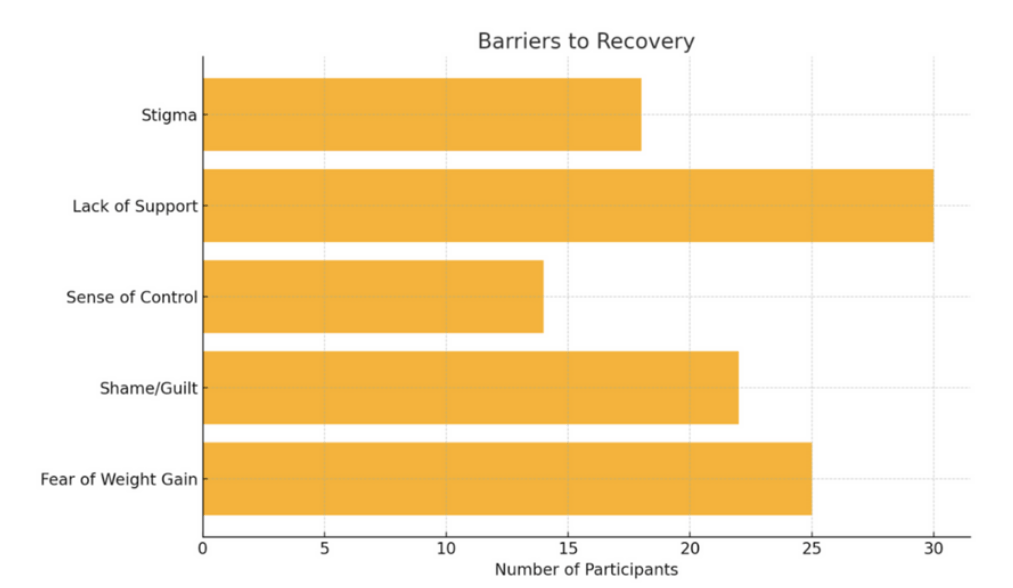

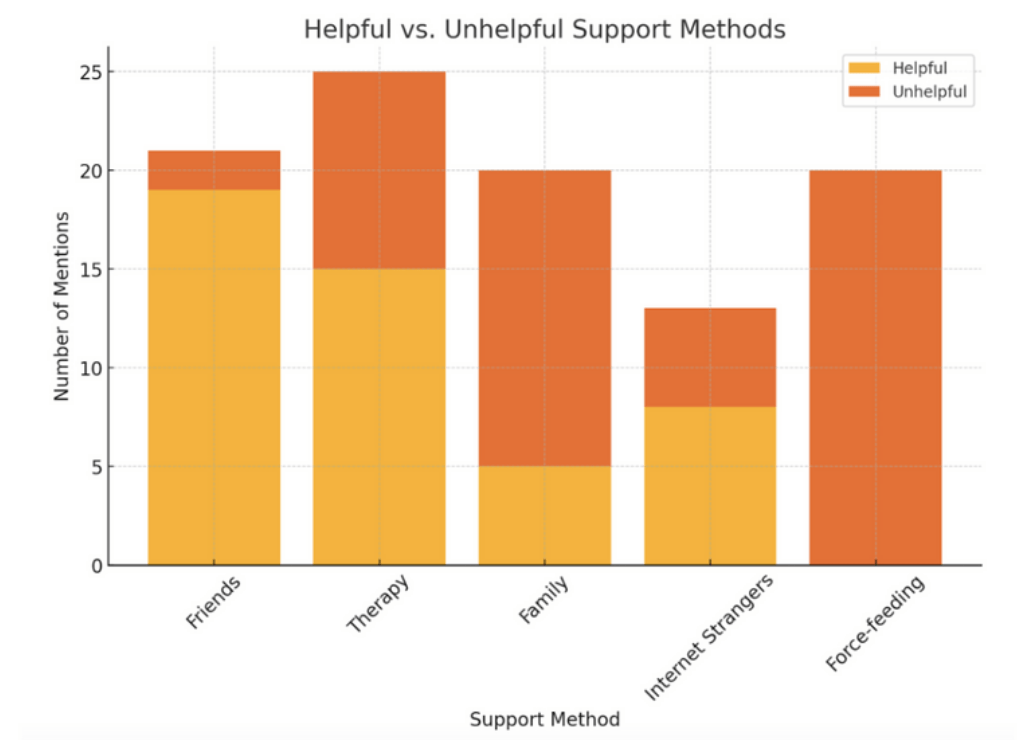

Regarding treatment and recovery, participants expressed mixed, often negative views of formal interventions. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, many recounted being force-fed, threatened with hospitalization, or shamed, which they viewed as coercive and emotionally damaging. A 16-year-old stated, “What wasn’t helpful was not allowing me to leave the room/table until I’d eaten a sufficient amount. That doesn’t help anyone. Being forced to eat with no mental health help.” In contrast, some cited more positive experiences with intuitive eating approaches or with trauma-informed therapists.

Finally, participants underscored that recovery is not linear. Several indicated that even after years of treatment, urges and thoughts persisted beneath the surface. One described the disorder as “never truly leaving” but instead “fading into the background.” A 28 year old reflected “relapses are guaranteed to happen but I am not back to square one, I have learned a lot along the way & can build upon that.”

inally participants underscored that recovery is not linear. Several indicated that even after years of treatment, urges and thoughts persisted beneath the surface. One described the disorder as “never truly leaving” but instead “fading into the background.” Another discussed the emotional complexity of weight restoration describing guilt and shame associated with physical changes. Across the dataset recovery was depicted not as the absence of symptoms but as a process of identity reconstruction a letting go of a false sense of control in favor of deeper often more painful emotional work. A 28-year-old reflected “relapses are guaranteed to happen but I am not back to square one, I have learned a lot along the way & can build upon that.”

This table presents selected participant narratives that illustrate key themes related to the lived experience of eating disorders. The narratives, drawn from individuals aged 13 to 39, reflect a range of ED presentations and recovery trajectories. The participants reported becoming aware of disordered eating behaviors at varying ages, with some recognizing symptoms as early as age 9 or 10, while others only identified their behaviors retrospectively or through indirect means, such as media or peer interactions. Sources of support in recovery varied widely and included peers, pets, online content, and in some cases, supportive friendships. Notably, family support was often described as inadequate or even detrimental. The experiences with support systems were often mixed; while peer support was frequently cited as helpful, approaches that focused solely on food intake without addressing underlying psychological distress were viewed as harmful. Some barriers to healing included fear of weight gain, social stigma, lack of mental health support, and emotional attachment to disordered behaviors as coping mechanisms. These narratives reflect the complexity and individuality of ED experiences and underscore the need for person-centered approaches to care.

Discussion

Common Themes in ED Onset

The present qualitative study, which examined 60 self reported narratives, successfully met its objectives by identifying key themes in eating disorder (ED) onset, exploring participants’ frustrations with public misconceptions, and categorizing effective and ineffective support methods.

The findings that EDs often begin with a gradual onset in early adolescence or late childhood is significant because it reinforces the understanding of these conditions as developmental processes rather than sudden occurrences. This supports prior research demonstrating that disordered eating typically emerges during transitional developmental periods15, but the data expands on this by showing that participants framed these early behaviors as adaptive coping mechanisms for overwhelming feelings or external pressures. The consistent emphasis on control provides a critical insight into the function of the disorder itself. Participants didn’t just report a need for control; they described their ED as providing a false sense of stability in chaotic lives. This aligns with existing research on identity fusion16, while also extending it by demonstrating how identity intertwines with disorder related behaviors from a very early stage. The recollection of specific triggering events, such as a grandparent’s comment, resonates with transgenerational trauma models17, yet the study contributes a novel perspective by showing how these moments crystallize into embodied distress. This deeper view moves us away from a simple cause and effect understanding toward a more holistic and systemic one.

Frustration with Public Misconceptions

The frustration participants expressed with public misconceptions is not simply a matter of hurt feelings; it is a critical barrier to care. The frequent mention of “Just Eat,” “Vanity Only,” and “Thin only EDs” as common public refrains demonstrates a widespread trivialization of serious mental illness. This finding confirms prior work showing that misconceptions hinder early intervention18, but expands on it by illustrating the sociological trauma of invalidation, particularly for participants with BED and ARFID. These narratives show that reductive stereotypes do not merely delay help seeking and they actively exacerbate isolation and shame. Therefore the findings underline the urgent need for public education campaigns that correct these harmful beliefs.

The Dual Role of Social Media

The study’s findings on social media illustrate a complex dynamic. While the exposure to “pro-ana” and “thinspo” content predictably intensified symptoms, which confirm prior concerns19, a more surprising result was the protective effect of unrelated digital spaces, such as K-pop fan communities. This adds to existing literature by highlighting that digital environments cannot be viewed monolithically: context and community matter more than platform alone. Similarly, the finding that peer support was often more effective than professional care does not contradict prior studies on clinical efficacy but complements them by underscoring the importance of emotional validation, empowerment, and lived experience in recovery.

Views on Formal Interventions

Participants’ mixed, often negative views of formal interventions underscore a critical gap in traditional care models. Reports of forced feeding and shaming are consistent with critiques of coercive practices20, but expand on them by showing the enduring psychological damage caused by these approaches. In contrast, positive experiences with intuitive eating and trauma informed therapy illustrate how approaches that prioritize autonomy and address underlying trauma align with recent calls for individualized, compassionate treatment models. The findings, therefore, support and extend this body of work, emphasizing that coercive and one-size-fits-all methods may undermine long term recovery.

Recovery as a Non-Linear Process

The study reinforces the concept of recovery as a non-linear process. Narratives describing the disorder as “never truly leaving” but “fading into the background” challenge the linear model of cure, aligning with recovery as journey frameworks21. However, the participants extend this literature by stressing that relapse is not failure but an expected part of recovery. This reframing provides an important clinical insight: recovery must be supported as an ongoing and identity based reconstruction rather than an endpoint22.

Implications and Recommendations

The findings highlight several key areas for clinical practice and public health. One important step is the implementation of early body image education at the elementary school level23. Such programs should emphasize media literacy, body diversity, and the importance of separating self worth from physical appearance. These lessons, introduced early, can help counteract harmful societal messages and build a foundation of resilience before disordered eating patterns emerge. Equally critical is the integration of trauma informed care across all eating disorder treatment settings24‘25. This involves training clinicians to recognize trauma triggers, adopting collaborative treatment planning that empowers patients in their recovery, and incorporating trauma-focused therapies such as Somatic Experiencing or EMDR alongside standard care26‘27‘28. By embedding these approaches into both prevention and treatment, clinical and public health systems can move beyond broad recommendations toward targeted, actionable strategies that are more likely to improve long-term outcomes for individuals with eating disorders.

Future Directions

To build on this work, future studies should employ diverse qualitative methodologies. Longitudinal interviews would capture how disordered eating develops and evolves over time. Ethnographic approaches could explore the culture and social dynamics of online ED communities in greater depth29. Narrative inquiry would allow for systematic analysis of recovery stories, capturing identity shifts and meaning-making processes. By employing these complementary methods, future research can expand on the nuances identified here.

Limitations

Although the study provides valuable insight, several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of a self-selected online sample may have introduced selection bias, as individuals in online ED communities may represent a more motivated, engaged, and potentially more severe subgroup than the general ED population. As a result, findings may not fully generalize to those who do not participate in these spaces. In addition, the survey’s open ended format did not permit follow-up or clarification, which limits interpretive depth compared to interviews. Reliance on self-report introduces further constraints: narratives may be influenced by recall bias or social desirability bias, and diagnoses were not clinically verified, raising the possibility of including individuals with sub-clinical or mischaracterized disordered eating. While these limitations temper the generalizability of the results, they also highlight the unique strength of this study which directly amplify lived experiences that are often overlooked in clinical research.

Methodological Note on Grounded Theory

This study employed a grounded theory approach to ensure that interpretations were deeply rooted in participants’ narratives. Analysis proceeded in three stages: open coding (initial labeling of raw responses), axial coding (connecting codes into broader categories), and selective coding (developing a central theoretical framework). This iterative process enabled me to construct a theory of ED onset, maintenance, and recovery directly from participants lived experiences.

Conclusion

This study adds to the qualitative literature on eating disorders by centering the lived experiences of adolescents and adults across a diverse age range, filling an important gap in research that too often overlooks personal narratives. The findings extend existing scholarship by illustrating six recurring themes: the covert onset of illness during vulnerable developmental stages; the role of eating behaviors as tools of emotional control and self definition; the impact of early trauma and intergenerational commentary; the persistence of societal misconceptions, particularly regarding non-anorexic eating disorders; the dual influence of digital and social spaces; and the identity-based, nonlinear nature of recovery. In doing so, this study challenges persistent stereotypes that trivialize eating disorders as conditions of vanity or restrict them to a narrow demographic. By highlighting the nuanced and deeply personal functions of disordered eating, the results underscore the need for trauma informed, person centered, and non-coercive models of care. Ultimately, these narratives reaffirm that recovery is possible, but it requires approaches that validate lived experience and provide long term and compassionate support.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the individuals who generously shared their personal experiences for this study. Their honesty and vulnerability made this research possible. I also acknowledge the online communities that helped disseminate the survey and fostered a space where participants felt safe to contribute. Finally, I am grateful to reviewers who provided guidance and feedback throughout the development of this project.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. What are eating disorders? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders (2024). [↩]

- R. Rankin, J. Conti, L. Ramjan, P. Hay. A systematic review of people’s lived experiences of inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: living in a “bubble”. J Eat Disord. 11, 95 (2023). [↩]

- E. Stice, C. F. Becker, J. M. Yokum. Eating disorder prevention: Current evidence-base and future directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46, 478-485 (2013). [↩]

- S. E. Wonderlich, J. J. Mitchell, R. D. Crosby, J. Myers, S. Kadlec. The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 346-355 (2004). [↩]

- H. Westmoreland, C. Krantz, C. A. Mehler. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. The American Journal of Medicine, 129, 30-37 (2016). [↩]

- J. Treasure, U. Schmidt. The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 1-10 (2013). [↩]

- National Eating Disorders Association. Statistics and research on eating disorders. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics-research-eating-disorders (2023). [↩]

- C. Peake, A. Lim, R. Gowers. The misuse of control in eating disorder treatment: A critique of coercive interventions. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 13, 204-210 (2005). [↩]

- A. M. Williams, R. L. Anderson. The role of control in eating disorders: A qualitative study of function and identity. Eat Disord. 26, 123-139 (2018). [↩]

- J. R. Fox, A. Chisholm, S. Tierney, J. R. E. Fox. Investigating service users’ perspectives of eating disorder services: a meta-synthesis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 29, 1276-1296 (2022). [↩]

- J. E. Murray. The lived experience of eating disorders: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 52, 1-15 (2022). [↩]

- D. M. Piran. Journeys of embodiment at the intersection of body and culture: The development of body esteem. Academic Press (2019). [↩]

- P. Tragantzopoulou, C. Mouratidis, K. Paitaridou, V. Giannouli. The battle within: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the experience of the eating disorder voice. Healthcare. 12, 2306 (2024). [↩]

- Vandereycken, W. (2011). The life of a patient with an eating disorder: Lived experience and recovery. European Eating Disorders Review, 19(5), 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1105. [↩]

- Slane, J. D., Klump, K. L., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2014). Developmental trajectories of disordered eating from early adolescence to young adulthood: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 793-801. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22329 [↩]

- Verschueren, M., Claes, L., Palmeroni, N., Leni Raemen, Moons, P., Liesbeth Bruckers, Geert Molenberghs, Dierckx, E., Katrien Schoevaerts, & Koen Luyckx. (2024). Identity Functioning in Patients with an Eating Disorder: Developmental Trajectories throughout Treatment. Nutrients, 16(5), 591-591. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050591 [↩]

- Barry, J., O’Connor, J., & Parsons, H. (2025). An (un)answered cry for help: a qualitative study exploring the subjective meaning of eating disorders in the context of transgenerational trauma. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01177-8 [↩]

- Puhl, R., & Suh, Y. (2015). Stigma and Eating and Weight Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0552-6 [↩]

- Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles, 71(11-12), 363-377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6 [↩]

- Blikshavn, T., Halvorsen, I., & Øyvind Rø. (2020). Physical restraint during inpatient treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa: frequency, clinical correlates, and associations with outcome at five-year follow-up. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00297-1 [↩]

- Kenny, T. E., Boyle, S. L., & Lewis, S. P. (2019). #recovery: Understanding recovery from the lens of recovery‐focused blogs posted by individuals with lived experience. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(8), 1234-1243. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23221 [↩]

- Moroshko, I., Raspovic, A., Liu, J., & Brennan, L. (2025). Trauma and eating disorders: an integrated umbrella and scoping review. Clinical Psychology Review, 119, 102592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2025.102592 [↩]

- Dane, A., & Bhatia, K. (2023). The social media diet: A scoping review to investigate the association between social media, body image and eating disorders amongst young people. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(3), e0001091. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001091 [↩]

- Brewerton, T. D., Alexander, J., & Schaefer, J. (2018). Trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders: personal and professional perspectives of lived experiences. Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia Bulimia and Obesity, 24(2), 329-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0628-5 [↩]

- Moberg, J. (2025). A call for a trauma-informed approach during compulsory care for enduring anorexia nervosa with combined PTSD – an autoethnographic perspective. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-025-01283-1 [↩]

- Eating Disorders and Trauma: The Missing Link. (2025). Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/missing-links/202502/eating-disorders-and-trauma-the-missing-link? [↩]

- Sylwia Jaruga-Sękowska, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, & Woźniak-Holecka, J. (2025). The Impact of Social Media on Eating Disorder Risk and Self-Esteem Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Psychosocial Analysis in Individuals Aged 16-25. Nutrients, 17(2), 219-219. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020219 [↩]

- Au, E. S., & Cosh, S. M. (2022). Social media and eating disorder recovery: An exploration of Instagram recovery community users and their reasons for engagement. Eating Behaviors, 46, 101651-101651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2022.101651 [↩]

- Xie, L., Ding, X., & Patterson, R. (2025). “My Eating Disorder Story” – An Interpretative Phenomenomenological Analysis of Social Media, Narrative Identity, and Patient Influencers in Eating Disorder Recovery. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-7080277/v1 [↩]