Abstract

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a common malignancy affecting the lips, tongue, salivary glands, gingiva, floor of the mouth, and oropharynx, accounting for approximately 3–5% of all human cancers. Despite ongoing therapeutic advances, the prognosis remains poor due to delayed diagnosis, highlighting the need for reliable, non-invasive biomarkers for early detection. In this study, we performed transcriptomic profiling of OSCC cells and normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK) to identify differentially expressed genes and discovered ADAMTSL4 as a significantly upregulated candidate in OSCC. Functional assays using CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene knockout revealed that ADAMTSL4 promotes OSCC cell proliferation, migration, and clonogenicity, suggesting a pro-tumorigenic role. Moreover, ADAMTSL4-specific DNA fragments were detected in the extracellular media of OSCC cells but not in HOK, indicating that tumor-derived cfDNA (cell-free DNA) containing ADAMTSL4 may serve as a liquid biopsy marker. Based on this finding, we developed a gold nanoparticle-based lateral flow assay (LFA) capable of detecting ADAMTSL4-positive cfDNA with a detection threshold of approximately 10 ng/mL. The lateral flow assay was successfully adapted into a cassette format suitable for clinical use, and saliva volume estimates suggested that 1–2 mL would be sufficient for detection, supporting its feasibility for point-of-care screening. Collectively, our findings identify ADAMTSL4 as a novel biomarker with functional and diagnostic relevance in OSCC and demonstrate the potential of a saliva-based cfDNA detection platform for non-invasive, rapid, and accessible cancer diagnostics.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, ADAMTSL4, cfDNA, lateral flow assay, saliva diagnostics, non-invasive biomarker, CRISPR-Cas9, early cancer detection

Introduction

Oral cancer refers to malignant tumors occurring in the lips, tongue, salivary glands, gingiva, floor of the mouth, oropharynx, and buccal mucosa. It accounts for approximately 3–5% of all human cancers, with an estimated 300,000 new cases diagnosed worldwide annually1. The development of oral cancer is a multistep process driven by the accumulation of genetic alterations that disrupt key cellular mechanisms, including signal transduction, DNA repair, and cell cycle regulation, ultimately leading to a loss of cellular homeostasis2‘3.

Recent studies have implicated disruptions in tumor suppressor pathways, such as TP53, CDKN2A, and RB1, in the field cancerization process associated with oral carcinogenesis4. However, the full spectrum of genetic and epigenetic changes involved remains incompletely understood. This underscores the urgent need to identify more definitive molecular markers for early diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting.

Biomarkers derived from various biofluids—including blood, serum, plasma, saliva, sputum, urine, and feces—offer promising tools for non-invasive or minimally invasive cancer detection5‘6. Among these, nucleic acids (DNA/RNA) extracted from blood, saliva, or exfoliated oral epithelial cells can be analyzed for mutations or expression changes linked to malignancy7. In recent years, salivary biomarkers have gained significant attention as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)8‘9. Previous studies have focused on both cfDNA and protein-based biomarkers, such as p53 and CD44, for OSCC detection9‘10‘11. These markers have shown promise in distinguishing cancerous tissues from healthy controls, but challenges remain regarding their sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility across diverse patient populations12‘13‘14. Recent advances have highlighted the potential of cfDNA as a biomarker in various cancers, including OSCC, offering a minimally invasive approach for early detection and monitoring15‘16‘17. However, comprehensive studies addressing the full spectrum of salivary cfDNA markers are still underdeveloped, emphasizing the need for novel biomarkers with higher sensitivity and specificity.

Importantly, biomarker-based screening may allow differentiation between healthy individuals and patients even in the absence of overt clinical or histological signs of cancer. Early detection of OSCC through minimally invasive sampling, such as saliva-based testing, represents a valuable strategy for reducing disease burden and improving clinical outcomes18‘19. Recent advances have demonstrated that tumor-derived DNA fragments can indeed be detected in saliva of head and neck cancer patients, supporting the feasibility of cfDNA as a salivary biomarker platform20. In particular, such studies highlight the potential of locus-specific detection strategies21, thereby motivating the investigation of novel targets like ADAMTSL4 for salivary cfDNA–based OSCC diagnostics.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cell lines were maintained in appropriate growth media under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). OSCC cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HOK cells were cultured in keratinocyte-specific media according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Sequencing and Transcriptomic Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from HOK and OSCC cells using a commercial RNA isolation kit. RNA integrity was confirmed using a Bioanalyzer. RNA-seq libraries were prepared and sequenced using an Illumina platform. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2, and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted to identify significantly altered pathways. Heatmaps were generated based on z-score–normalized expression values across replicates.

CRISPR-Cas9–Mediated Gene Knockout

CRISPR-Cas9 technology was used to generate ADAMTSL4 knockout OSCC cell lines. Single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting ADAMTSL4 were cloned into a lentiviral vector and transduced into OSCC cells. Knockout efficiency was validated at the mRNA level by quantitative RT-PCR and at the protein level by Western blotting. sgRNA #1 : TTCGATATAACCGTCCTCCC, sgRNA #2 : AGGACGGTTATATCGAAAGA

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix with gene-specific primers for ADAMTSL4 and housekeeping gene GAPDH. Relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Each reaction was conducted with three biological replicates, and each sample was measured in triplicate (technical replicates). ADAMTSL4_mRNA-For : 5’-GGAGACCCAGGAGATTCGAG-3’, ADAMTSL4_mRNA-Rev : 5’-GTAGGGGACGGAATAGCCTC-3’

Western Blotting

Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against ADAMTSL4 (Abcam; ab71838), Akt(Cell signaling technology; #9272) and β-actin (Santa Cruz; sc-130065), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Western blotting experiments were repeated three times with independent biological samples.

Transwell Migration Assay

Cell migration was assessed using 24-well Transwell chambers with 8 μm pore-size inserts. Equal numbers of control and ADAMTSL4 knockout OSCC cells were seeded into serum-free media in the upper chamber. The lower chamber contained media supplemented with 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. After 24 hours, migrated cells on the lower membrane surface were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and quantified under a microscope. Each assay was performed using three independent biological replicates, with duplicate wells for each condition.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was measured by manual cell counting over a 7-day time course. Control and ADAMTSL4-deficient OSCC cells were seeded at equal densities in triplicate wells and harvested at indicated time points for counting using a hemocytometer. Colony formation was assessed in three independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate.

Colony Formation Assay

Cells were plated at low density (20,000cells/well) in 6-well plates and cultured for 10–14 days. Colonies were fixed with paraformaldehyde, stained with crystal violet, and counted.

cfDNA Extraction from Culture Media

Culture supernatants from HOK and OSCC cells (1 × 10⁶ ) were collected after 48 hours. cfDNA was isolated using a cell-free DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quality and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. PCR was performed using primers specific for the ADAMTSL4 locus to detect tumor-derived cfDNA. cfDNA PCR detection was performed with three biological replicates, and each PCR reaction was repeated twice. ADAMTSL4_gDNA-For : 5’-CCAGGACCGATGGTTTTCCA-3’, ADAMTSL4_gDNA-Rev : 5’-TTGGCTGGGCTTATTCTGGG-3’

Lateral Flow Assay Development

Sample Denaturation/Preparation:

For LFA analysis, saliva samples were collected and immediately processed. Samples were denatured by incubating at 95°C for 10 minutes prior to loading onto the lateral flow device. Denaturation was performed to ensure the complete release of cfDNA from cellular components.

Run Time:

The typical run time for the lateral flow assay was 30 minutes. After sample addition, the test strip was incubated at room temperature, and the test results were visually assessed at the 30-minute mark.

Acceptance Criteria for Control Line:

The assay was considered valid if the control line was clearly visible. A test line was considered positive when its intensity was comparable to the control line. A faint or absent test line indicated an invalid or negative result. Results were interpreted based on the intensity of the test line in comparison to the control line, ensuring a clear and reproducible outcome.

DNA probes test:

An lateral flow assay was developed using gold nanoparticle–labeled DNA probes complementary to the ADAMTSL4 target sequence (5′-AAAAAA-CGGCGGCCACTGGGGCCCCT-SH-3′). The test strip consisted of a sample pad, conjugation pad, nitrocellulose membrane with test and control lines (test line : 5′-CGGCGGCCACTGGGGCCCCT-3′, control line : 5′-NH2-(CH2)6-TTTTTT-3′), and absorbent pad. cfDNA samples were applied to the strip, and hybridization signal was visually interpreted. Detection sensitivity was evaluated using serial dilutions of cfDNA (0.5–50 ng/mL) extracted from OSCC media.

Cassette Integration and Saliva Volume Estimation

The lateral flow assay was embedded into a plastic cassette housing for user-friendly operation. To assess clinical applicability, we estimated the minimum volume of saliva required for cfDNA-based detection, assuming a concentration range of 10–50 ng/mL. A volume of 1–2 mL was projected to be sufficient to reach the detection threshold of the lateral flow assay.

Results

A graphical overview of the experimental strategy for identifying and validating oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) biomarkers.

Normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells were subjected to transcriptomic comparison to identify differentially expressed biomarker candidates. Among these, specific targets were found to be released as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or cfDNA fragments, enabling detection in saliva. This led to the development of a saliva-based lateral flow assay (Fig. 1), highlighting the potential for non-invasive and rapid detection of OSCC using liquid biopsy-derived biomarkers.

Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals OSCC-Associated Pathways and Highlights ADAMTSL4 as a Potential Biomarker

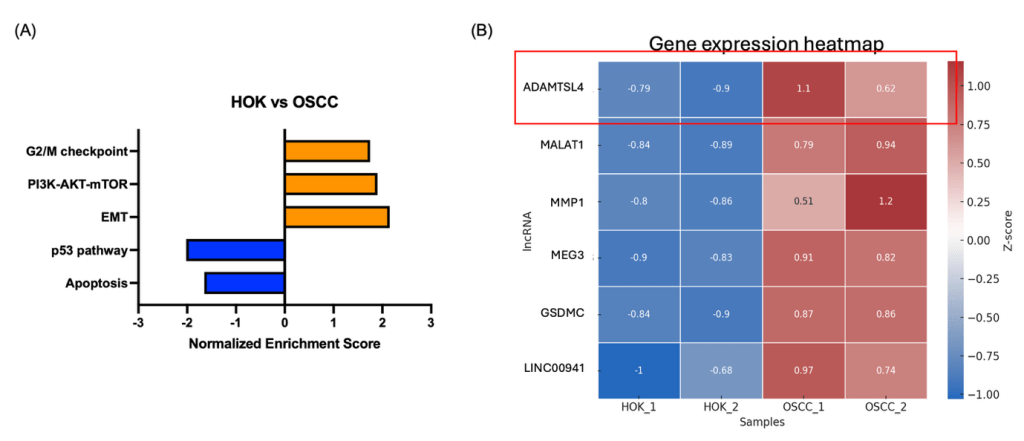

(A) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) comparing OSCC cell lines and normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK) reveals upregulation of cancer-related pathways (orange) and enrichment of tumor-suppressive pathways in HOK (blue).

(B) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between OSCC and HOK samples. ADAMTSL4 shows the most prominent upregulation in OSCC cells, suggesting its potential as a biomarker.

To identify transcriptomic alterations associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), we performed RNA sequencing of OSCC cell lines and normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed a strong upregulation of cancer-related pathways in OSCC, including epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and G2/M checkpoint regulation, while tumor-suppressive pathways such as p53 signaling and apoptosis were enriched in HOK samples (Fig. 2A).

To further pinpoint potential biomarker candidates, we generated a heatmap of differentially expressed genes with consistent changes across replicates. Among the top candidates, ADAMTSL4 exhibited the most prominent increase in OSCC cells compared to HOK, and was further prioritized based on its highest fold change, extracellular matrix–associated function, and potential secretion into saliva, making it a strong candidate biomarker for downstream validation. (Fig. 2B). This gene encodes a secreted ECM-associated glycoprotein 1, and although its role in oral cancer has not been previously described, its distinct overexpression pattern suggests it may contribute to tumor progression and serve as a potential diagnostic target.

ADAMTSL4 Promotes OSCC Cell Motility and Tumorigenic Potential

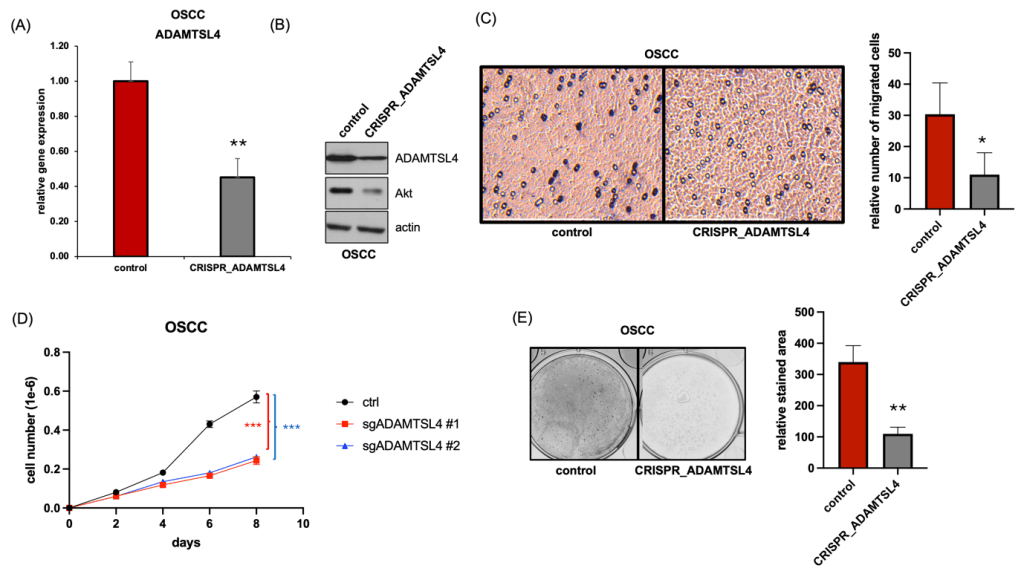

(A and B) CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout of ADAMTSL4 was validated by qRT-PCR (A) and Western blotting (B).

(C) Transwell migration assay showing reduced migratory ability of ADAMTSL4-deficient OSCC cells compared to control.

(D) Cell proliferation assay indicating decreased growth in two independent ADAMTSL4 knockout clones (sgADAMTSL4 #1 and #2) relative to control cells.

(E) Colony formation assay demonstrating impaired proliferative ability in ADAMTSL4 knockout OSCC cells.

To determine the functional role of ADAMTSL4 in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), we generated ADAMTSL4-knockout cells using CRISPR-Cas9. Knockout efficiency was confirmed at both the mRNA and protein levels, as shown by qRT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively (Fig. 3A and B).

Given that ADAMTSL4 is a secreted extracellular matrix-associated glycoprotein known to interact with microfibrillar components such as fibrillin-122, we hypothesized that it may influence cell motility by modulating the tumor microenvironment. To evaluate this possibility, we performed Transwell migration assays following CRISPR-mediated knockout of ADAMTSL4 in OSCC cells. Notably, ADAMTSL4-deficient cells exhibited about 67% reduced migratory capacity compared to controls, suggesting that ADAMTSL4 contributes to the enhanced motility and invasive potential characteristic of malignant OSCC cells (Fig. 3C).

Moreover, cell counting revealed a 75% decrease in cell proliferation in ADAMTSL4-deficient cells compared to controls (Fig. 3D). Colony formation assays further demonstrated a marked reduction in clonogenic potential following ADAMTSL4 deletion, suggesting its critical role in maintaining OSCC cell viability and self-renewal capacity (Fig. 3E).

Collectively, these findings support a pro-tumorigenic role of ADAMTSL4 in OSCC, implicating it as a novel functional driver of tumor progression and a potential therapeutic target.

OSCC Cells Release ADAMTSL4-Positive cfDNA into the Extracellular Environment, Supporting Its Potential as a Non-Invasive Biomarker

(A) Schematic illustration of cfDNA release from normal human oral keratinocytes (HOK) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells in vitro.

(B) PCR amplification of cfDNA extracted from culture media. ADAMTSL4-specific DNA fragments were detected only in the OSCC-derived medium, indicating tumor-specific release of this marker into the extracellular environment.

Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) refers to short DNA fragments released into the extracellular environment during cellular turnover, including apoptosis, necrosis, or active secretion23. In cancer, tumor-derived cfDNA (ctDNA) carries specific genetic and epigenetic signatures of malignant cells, and its presence in biofluids such as plasma or saliva offers a non-invasive window into the tumor genome24.

To investigate whether ADAMTSL4, which was overexpressed in OSCC cells, could be detected as part of tumor-derived cfDNA, we first modeled cfDNA release in vitro using cell culture systems (Fig. 4A). Culture media from both HOK and OSCC cells were collected and processed for cfDNA extraction, followed by PCR amplification targeting the ADAMTSL4 locus. Notably, ADAMTSL4-specific cfDNA fragments were detectable only in the OSCC-derived medium, but not in that from HOK cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting that tumor cells actively release this biomarker into the extracellular environment.

These findings indicate that ADAMTSL4 is not only overexpressed at the cellular level but also released into the surrounding fluid in a detectable form, supporting its potential utility as a saliva-based diagnostic marker for OSCC.

Lateral Flow Assay Enables Detection of ADAMTSL4-Positive cfDNA for OSCC Screening

(A) Schematic of the a lateral flow assay design targeting ADAMTSL4 cfDNA using gold nanoparticle-labeled probes and a dual-line readout (test and control lines).

(B) Strip-based a lateral flow assay results using cfDNA extracted from OSCC culture media at various concentrations (0.5–50 ng/mL), showing detectable test line signal at ≥10 ng/mL.

(C) Integration of the lateral flow assay strip into a cassette-type format for clinical applicability, maintaining clear visibility of test and control lines.

To evaluate the sensitivity and practical applicability of our ADAMTSL4-targeting lateral flow assay (Fig. 5A), we extracted cfDNA from OSCC culture media and tested a series of seven concentration points ranging from 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, 25 to 50 ng/mL (Fig. 5B). We observed that visible signal at the test line emerged consistently at concentrations ≥10 ng/mL, indicating a functional detection threshold around this level. This finding validates the quantitative responsiveness of our lateral flow assay system and supports its feasibility for cfDNA-based biomarker detection. To assess translational potential, we integrated the strip into a cassette-type format suitable for clinical use, which maintained clear visibility of both test and control lines. Furthermore, given the potential for saliva-based non-invasive diagnostics in OSCC, we estimated the volume of saliva required for practical application. Based on identified cfDNA levels in OSCC cell line (10–50 ng/mL), we calculated that 1–2 mL of saliva would be sufficient to yield ≥10 ng of cfDNA after extraction, allowing for detection by our system (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that our platform could be adapted for point-of-care OSCC screening using saliva samples, with minimal invasiveness and high user accessibility.

Discussion

In this study, we identified ADAMTSL4 as a novel biomarker candidate for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) through transcriptomic profiling. ADAMTSL4, a member of the ADAMTS/ADAMTSL family25‘26, plays a crucial role in extracellular matrix remodeling and has been implicated in various cancers, including OSCC27. However, its potential as a salivary biomarker for OSCC detection has not been extensively explored. Our findings highlight ADAMTSL4 as a promising candidate for non-invasive OSCC detection through saliva-based cfDNA analysis. This study expands upon the limited research surrounding ADAMTSL4 and provides a comprehensive understanding of its potential role in cancer diagnosis.

Functional studies confirmed its pro-tumorigenic role, including enhanced migratory and proliferative capacity in OSCC cells. Notably, ADAMTSL4 was not only overexpressed at the cellular level but also detected in the extracellular medium in the form of cfDNA fragments specifically released from OSCC cells, but not from normal oral keratinocytes (HOK). This selective release highlights its potential as a tumor-derived cfDNA marker.

To explore the translational applicability of this finding, we developed a lateral flow assay capable of detecting ADAMTSL4-containing cfDNA at physiologically relevant concentrations (≥10 ng/mL). This system was successfully adapted to a cassette-type format suitable for clinical use, and saliva volume estimates suggest that 1–2 mL saliva would be sufficient for detection. These results indicate that our platform could serve as the basis for a rapid, non-invasive, point-of-care test for OSCC using saliva—a readily accessible and patient-friendly biofluid. However, because cfDNA was extracted from equal numbers of untreated HOK and OSCC cells, potential bias from unequal cell death or treatment-induced DNA release is minimized; however, distinguishing gene-specific release from bulk DNA shedding remains a limitation of this study.

Despite the promising results, several limitations warrant consideration. First, our cfDNA detection was conducted exclusively in in vitro culture systems. Although the assay demonstrated high sensitivity under these controlled conditions, its performance in clinical saliva samples from OSCC patients remains untested and therefore cannot be assumed. In particular, factors such as cfDNA fragmentation patterns, degradation by salivary nucleases, microbial DNA interference, and interindividual variability in cfDNA concentration may significantly influence real-world performance. Accordingly, the present results should be interpreted as preliminary, and we clearly recognize that extensive validation in patient-derived saliva is an essential next step before any clinical translation.

Second, while we focused on a single gene target (ADAMTSL4) as a proof-of-concept, we acknowledge that OSCC is a genetically heterogeneous disease. Relying on a single biomarker may limit assay sensitivity across diverse patient populations. A multiplexed detection approach incorporating additional OSCC-associated genes would likely enhance diagnostic sensitivity and specificity and represents an important direction for future validation.

Third, the current lateral flow assay platform is semi-quantitative and was only evaluated qualitatively in this study; future integration with digital or smartphone-based signal quantification, along with rigorous validation of specificity, detection limits, reproducibility, and operator variability, could provide more precise readouts and improve its utility for disease monitoring and stratification.

In summary, our study identifies ADAMTSL4 as a functionally relevant and cfDNA-releasable biomarker for OSCC and establishes a foundation for non-invasive detection using a saliva-based lateral flow system. This study did not evaluate potential saliva matrix effects, such as nuclease activity, microbial DNA, or inhibitory compounds; we acknowledge this as a limitation and emphasize that future studies must validate assay performance in raw and spiked saliva samples to establish point-of-care feasibility. In future studies, we plan to experimentally analyze the impact of various variables on cfDNA stability in saliva when using actual saliva samples. Specifically, we will collect saliva under different conditions and evaluate cfDNA stability when stored at freezing temperatures. Additionally, we plan to test the impact of oral care products (e.g., mouthwash, toothpaste), food, and blood contamination on cfDNA detection. Through these experiments, we aim to enhance the reliability of cfDNA detection in point-of-care settings and establish the stability of saliva-based tests under various external factors. If validated, this approach could significantly enhance early detection and screening strategies for oral cancer, especially in low-resource settings where access to conventional diagnostic tools is limited.

References

- Parkin, D.M., Laara, E. & Muir, C.S. Estimates of the worldwide frequency of sixteen major cancers in 1980. Int J Cancer 41, 184-197 (1988). [↩]

- Williams, H.K. Molecular pathogenesis of oral squamous carcinoma. Mol Pathol 53, 165-172 (2000). [↩]

- Scully, C., Field, J.K. & Tanzawa, H. Genetic aberrations in oral or head and neck squamous cell carcinoma 2: chromosomal aberrations. Oral Oncol 36, 311-327 (2000). [↩]

- Pai, S.I. & Westra, W.H. Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol 4, 49-70 (2009). [↩]

- Cho, W.C. Circulating MicroRNAs as Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for Cancer Theragnosis and Prognosis. Frontiers in Genetics volume 2 – 2011(2011). [↩]

- Mansour, H. Cell-free nucleic acids as noninvasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer detection. Frontiers in Genetics Volume 5 – 2014(2014). [↩]

- Palanisamy, V., et al. Nanostructural and Transcriptomic Analyses of Human Saliva Derived Exosomes. PLOS ONE 5, e8577 (2010), Towle, R. & Garnis, C. Methylation-Mediated Molecular Dysregulation in Clinical Oral Malignancy. Journal of Oncology 2012, 170172 (2012). [↩]

- Ferrari, E., et al. Salivary Cytokines as Biomarkers for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, 6795 (2021). [↩]

- Sannam Khan, R., Khurshid, Z., Akhbar, S. & Faraz Moin, S. Advances of Salivary Proteomics in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) Detection: An Update. Proteomes 4, 41 (2016). [↩] [↩]

- Boxberg, M., et al. Immunohistochemical expression of CD44 in oral squamous cell carcinoma in relation to histomorphological parameters and clinicopathological factors. Histopathology 73, 559-572 (2018). [↩]

- Yen, C.-Y., et al. Evaluating the performance of fibronectin 1 (FN1), integrin α4β1 (ITGA4), syndecan-2 (SDC2), and glycoprotein CD44 as the potential biomarkers of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Biomarkers 18, 63-72 (2013). [↩]

- Das, S., Dey, M.K., Devireddy, R. & Gartia, M.R. Biomarkers in Cancer Detection, Diagnosis, and Prognosis. Sensors 24, 37 (2024). [↩]

- Franzmann, E.J., et al. Soluble CD44 Is a Potential Marker for the Early Detection of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 16, 1348-1355 (2007). [↩]

- Mordente, A., Meucci, E., Martorana, G.E. & Silvestrini, A. Cancer Biomarkers Discovery and Validation: State of the Art, Problems and Future Perspectives. in Advances in Cancer Biomarkers: From biochemistry to clinic for a critical revision (ed. Scatena, R.) 9-26 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2015). [↩]

- Mishra, M., et al. Recent Advancements in the Application of Circulating Tumor DNA as Biomarkers for Early Detection of Cancers. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 10, 4740-4756 (2024). [↩]

- Corcoran, R.B. Circulating Tumor DNA: Clinical Monitoring and Early Detection. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 3, 187-201 (2019). [↩]

- Chang, Y., et al. Review of the clinical applications and technological advances of circulating tumor DNA in cancer monitoring (2017). [↩]

- Santosh, A.B.R., Jones, T. & Harvey, J. A review on oral cancer biomarkers: Understanding the past and learning from the present. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics 12, 486-492 (2016). [↩]

- Ma, Y., Wang, X. & Jin, H. Methylated DNA and microRNA in body fluids as biomarkers for cancer detection. Int J Mol Sci 14, 10307-10331 (2013). [↩]

- Gaykalova, D.A., et al. Outlier Analysis Defines Zinc Finger Gene Family DNA Methylation in Tumors and Saliva of Head and Neck Cancer Patients. PLOS ONE 10, e0142148 (2015). [↩]

- Rapado-González, Ó., López-Cedrún, J.L., López-López, R., Rodríguez-Ces, A.M. & Suárez-Cunqueiro, M.M. Saliva Gene Promoter Hypermethylation as a Biomarker in Oral Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, 1931 (2021). [↩]

- Gabriel, L.A., et al. ADAMTSL4, a secreted glycoprotein widely distributed in the eye, binds fibrillin-1 microfibrils and accelerates microfibril biogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 461-469 (2012). [↩]

- Diehl, F., et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med 14, 985-990 (2008). [↩]

- Oxnard, G.R., et al. Simultaneous multi-cancer detection and tissue of origin (TOO) localization using targeted bisulfite sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Annals of Oncology 30, 912-912 (2019). [↩]

- Le Goff, C. & Cormier-Daire, V. The ADAMTS(L) family and human genetic disorders. Human Molecular Genetics 20, R163-R167 (2011). [↩]

- Zhang, X., et al. The potential prognostic values of the ADAMTS-like protein family: an integrative pan-cancer analysis. Annals of Translational Medicine 9, 1562 (2021). [↩]

- Zhang, X., et al. The potential prognostic values of the ADAMTS-like protein family: an integrative pan-cancer analysis. Ann Transl Med 9, 1562 (2021). [↩]