Abstract

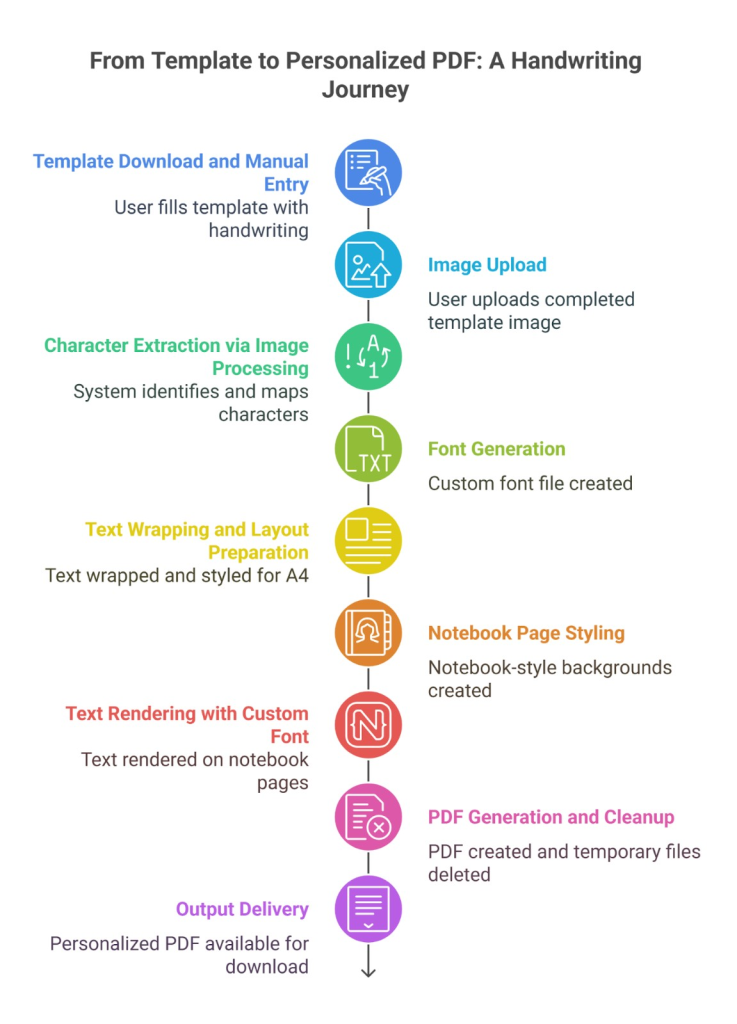

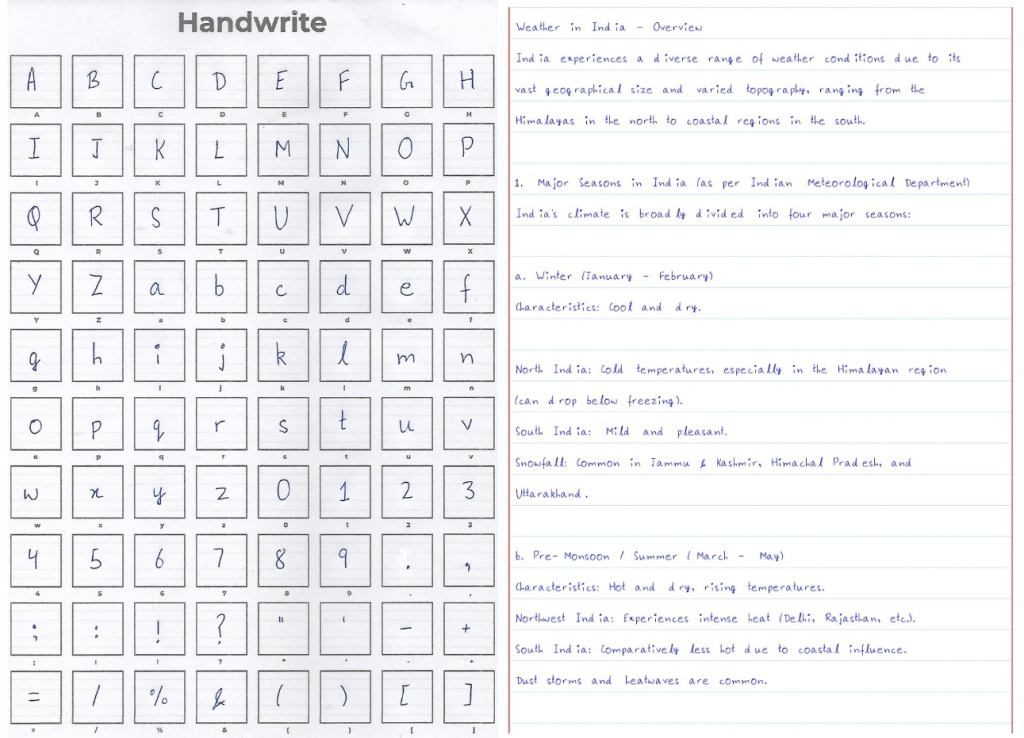

Academic stress and inefficient study habits are major challenges for students worldwide, yet personalized tutoring remains inaccessible for many learners. Current AI tutors mainly rely on imitation learning, which allows them to reproduce expert explanations but limits their ability to adapt to diverse student needs. In response, this study introduces PrepGPT, a locally deployed, privacy-first AI-tutor focused on student-sensitive and curriculum-aligned support aimed at enhancing adaptive learning. Our primary contribution is the development of the Emergent Machine Pedagogy (EMP) conceptual framework, which is a theory of how machine learning can be adapted to recognize and respond to individual student learning patterns; we refer to it as Dynamic Entropy Group Relative Policy Optimization (DE-GRPO): an optimization method that personalizes educational feedback by learning from diverse student interactions. To ensure practical relevance, we conducted two human surveys: one involving 70 students and another involving 20 practicing educators who performed blind comparative assessments against baseline models. In small-scale experiments, DE-GRPO produced explanations that were more varied and sometimes more effective than standard methods.We integrate diversity‑aware training of the Teacher via DE‑GRPO and provide runtime logs demonstrating reward progression and entropy control. We further validated the framework by developing PrepGPT, which demonstrates key features such as adaptive explanations, multiple solution paths, and handwritten study note generation in the student’s own handwriting; all while operating on consumer hardware without cloud dependence. These results provide early, framework evidence that AI tutors may be able to move beyond simple imitation and move towards more adaptive strategies.

Keywords: Emergent Machine Pedagogy (EMP); Dynamic Entropy Group Relative Policy Optimization (DE-GRPO); Curriculum-Aligned Support; Adaptive Explanations; Handwritten Notes Generation; Imitation Learning; Reinforcement Learning; AI in Education.

Introduction

Academic stress and inefficient study habits are prevalent issues affecting students from all academic backgrounds1. The increasing demands of coursework, the overwhelming volume of study materials, and peer pressure contribute to challenges in academic performance and well-being, even raising college dropout rates2‘3. A 2023 study of 320 undergraduate nursing students in Mangalore found that 65.6% experienced moderate stress and 31.9% experienced high stress, with higher stress levels directly associated with poorer grades4. Personalized support such as one-on-one tutoring is linked to higher achievement, yet limited accessibility creates inequities. Thus, there is a pressing need to create accessible solutions that provide personalized study support at scale5. A semester-long study was conducted at UniDistance Suisse, an AI tutor app provided to psychology students taking a neuroscience course. It generated microlearning questions from pre existing materials and the tutor maintained a dynamic neural network of every student’s grasp of concepts. This shows implementation of dynamic retrieval practice and personalisation.

Artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT and Bard are increasingly being adopted and used in education, showing strong capability in domains such as grammar correction, structured factual recall, and real-time Q&A for well-defined queries. In these contexts, LLMs demonstrate a high degree of reliability—especially when their outputs can be verified against authoritative sources, or when retrieval-augmented techniques are used. However persistent issues remain,ChatGPT-3.5 fabricated 55% of references and introduced substantive errors in 43% of non-fabricated citations6. Similarly, a systematic review found hallucinated references in 39.6% of ChatGPT-3.5 outputs and 91.4% of Bard’s7. Such unreliability makes them unsuitable for education where factual precision is essential. While platforms like Socratic, Ada, and Habitica support learning, no peer-reviewed evidence shows they integrate curriculum analysis, generate adaptive study aids such as flashcards, or incorporate essential privacy and transparency mechanisms8‘9. Thus the role of LLMs in the education sector is key, but comes with many limitations too10.

Large LLMs also struggle to emulate flexible, relational reasoning. Although they achieve human-level performance on some analogy tasks, researchers debate whether this reflects genuine understanding or surface-level pattern matching11. Chinese chatbot DeepSeek, though cost-effective, faced restrictions or bans in several countries due to privacy and security concerns12 and many other privacy risks are included13. Even the most advanced LLMs remain limited in explaining complex concepts in diverse ways that adapt to individual learning needs14. Their reasoning is primarily associative rather than relational, limiting their ability to reframe misunderstood concepts or synthesize new explanatory analogies15. Moreover, most AI applications in education focus on surface-level personalization rather than aligning content with specific academic goals16. Despite the growth of commercial AI tools, little research explores open-source, locally deployed systems that are privacy-conscious and curriculum-specific. This gap—the lack of open-source, curriculum-aware, and privacy-preserving tutoring agents—is what drives our work. With PrepGPT, we hope to reduce exam-related stress and improve study efficiency by creating an AI-powered chatbot that works locally on the user’s device, ensuring data both privacy and security. Designed with ethical principles in mind, PrepGPT gives students full control while analyzing their course syllabi to highlight key concepts and create personalized, adaptive flashcards to make learning more effective. To address LLMs’ lack of pedagogical flexibility, we introduce a Teacher LLM fine-tuning module designed to synthesize explanations, analogies, and counter-examples tailored to student needs. Unlike other template-based outputs, the Teacher LLM anticipates misconceptions and reframes explanations, simulating human-like instructional nuance for the user.

Built using a modular LangGraph architecture, the chatbot leverages open-source LLaMA models for local inference, ensuring both privacy and accessibility. We also introduce a framework simulating two interacting agentic systems designed to co-evolve through instructional dynamics. In our setup, one model generates challenging questions while the Teacher LLM is rewarded for resolving confusion. Trained pedagogically, the Teacher LLM learns to explain concepts clearly and anticipate whether responses effectively address misunderstandings or not. Interestingly, the AI sometimes appeared able to anticipate the effectiveness of its explanations. Supporting this framework is a self-synthesizing automation pipeline which manages training, question generation, feedback, and refinement—attempting to create a framework for scalable, curriculum-aware tutoring agents.

By uniting explainability, adaptivity, and ethical design, this study aims to make organized, high-impact study tools accessible to students lacking formal tutoring, promoting educational equality. The modern AI era has been defined by imitation learning, where models replicate human-generated patterns. This has produced remarkable capabilities, but it also reveals a fundamental limitation: an imitation system is a high-fidelity mirror—it cannot create beyond its data. We define this as the Imitation Efficacy Ceiling (IEC) : imitation alone cannot systematically exceed the best available expert demonstrations explained briefly and formally further explained in the theoretical framework subsection of the methods section.

This paper explores a framework that we call Emergent Machine Pedagogy (EMP). We suggest co-evolving agents could discover new teaching strategies through guided interaction, much as self-play enabled AlphaGo to discover superhuman strategies in defined games. A principled “self-teaching game” may unlock autonomous discovery of novel principles in pedagogy, reasoning, and design. This reframes learning from imitation toward goal-oriented discovery.

The core limitation of current AI tutors remains their reliance on imitation learning, constrained by the IEC : combining existing expert examples cannot yield performance beyond the single best expert. To enable inventive AI, systems must venture beyond this ceiling. This paper introduces a complete framework to achieve this. First, we present the conceptual framework of Emergent Machine Pedagogy. Second, we introduce our novel algorithm, Dynamic Entropy Group Relative Policy Optimization (DE-GRPO), translating EMP principles into reinforcement learning practice. Finally, we share preliminary results in a controlled environment suggesting DE-GRPO may outperform imitation-based methods.

Methods

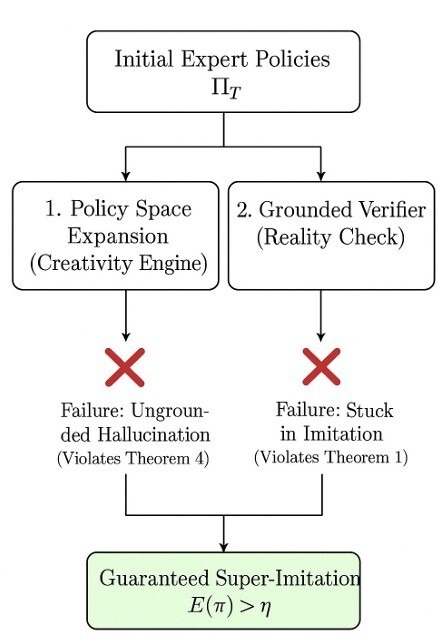

An experimental design was conducted to evaluate the performance of the PrepGPT AI tutoring system. Our approach is 2 fold; Introduce a new theoretical framework Emergent Machine Pedagogy(EMP) which motivates the core algorithm of our system, secondly detail a full implementation of the PrepGPT application, a localized, privacy first, multi agent model designed to bridge the educational divide for students from under resourced backgrounds. This section architects the system architecture, the core theoretical algorithm, key features like handwriting notes generation and ethical features that guided this research. Our framework is built upon the COGNITA stochastic game formalism, a multi-agent environment designed to model pedagogical interactions. This framework provides 5 principles that: Defines the limits of old paradigm, proving the potential of the new, describing the mechanism of discovery, guaranteeing its stability and alignment and proving its components are essential.

Theoretical Framework: The Quintet for Emergent Pedagogy

To model the complex, interactive nature of teaching, a simple Markov Decision Process (MDP) is insufficient, as it typically frames the problem from a single agent’s perspective. We instead adopt a multi-agent stochastic game formalism, COGNITA17 (Mathematical specification of COGNITA :See Appendix A.2 for the concrete instantiation used in our PedagogyEnv) . This choice is deliberate: it allows us to explicitly model the distinct, and sometimes competing, objectives of the Teacher (pedagogical efficacy), the Student (knowledge acquisition), and the Verifier (objective grounding). This multi-agent view is critical for capturing the dynamics of guided discovery, where the Teacher’s policy must adapt to a changing Student state,a problem that cannot be fully captured by a static environment.

Our DE-GRPO algorithm was designed to reflect ideas from our conceptual framework, Emergent Machine Pedagogy (EMP)18‘19. This framework is built on a quintet of guiding principles that define a logical arc from the problem to a potential solution. We outline the reasoning behind these principles and connect them to established ideas in reinforcement learning and pedagogy20.

Impossibility: The IEC. This principle establishes that an AI learning only from expert examples is forever capped by the performance of the best single expert21‘22. It defines the problem we must solve. Illustrative example: A warehouse robot is trained with behavioral cloning from expert teleoperation videos to pick items from bins and place them on a conveyor, initially matching expert moves on common parts and lighting but never interacting with the environment during training23. As more of the same videos are added, success rises quickly on standard cases but then plateaus at a high-yet-suboptimal rate, because rare failure modes (crumpled packaging, occlusions, slippery surfaces) are underrepresented and the policy encounters unseen states where compounding errors amplify, forming the imitation ceiling24‘25.The plateau persists because demonstrations omit crucial latent information (tactile cues, precise friction, fine-grained depth), so copying observable trajectories cannot resolve ambiguities or recover when off-distribution. While such systems can equal expert humans, they cannot systematically surpass them or discover strategies outside human experience. To create inventive AI systems capable of novel problem-solving, we must move beyond imitation26.

Possibility: The Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff. For breaking the ceiling, an agent must explore novel strategies. This exploration always carries the risk of temporary failure, but it is the necessary price for discovering a superior strategy for the agent. It proves a solution is possible, but costly. Innovation is possible, but since experiments can fail, we must control and encourage productive exploration.

Mechanism: The Critical Diversity Threshold. Discovery is not gradual; it is a phase transition. Below a critical level of strategic diversity, an agent remains trapped. Above it, breakthroughs become possible27‘28. This tells us how to enable discovery, by actively managing diversity. This highlights a practical mechanism: explicitly manage diversity so the system reaches the regime where breakthroughs occur29.

Robustness: The PAC-Verifier Guarantee. Invention without grounding is hallucination30. This principle guarantees that if the agent’s discoveries are judged by a reliable “Verifier,” the resulting strategies will be genuinely effective, not just creative fictions. This ensures our agent learns useful things. Even with rich discovery, inventions must be grounded — hence the Verifier is necessary to ensure practical value.

Necessity: The No Free Lunch principle for Pedagogy. This final principle proves that the two core components,a mechanism for novel strategy generation (Creativity) and a grounded Verifier (Reality Check),are both essential. Without both, an agent is probably doomed to remain an imitator. Taken together, these results imply that any successful pedagogical agent must jointly implement both creativity and a reliable reality check.

| Principle | One-line meaning | Real-life teaching example |

| Impossibility (IEC) | Learning only from expert examples cannot exceed the best expert. | A novice teacher who only copies a master teacher never develops a better method. |

| Discovery–Efficacy Tradeoff | To surpass experts you must explore new strategies, accepting short-term failures. | A teacher experiments with a flipped-classroom activity; student scores dip initially but later improve for deeper understanding. |

| Critical Diversity Threshold | Breakthroughs occur only after enough diversity of strategies is present — a phase transition. | A department encourages many different lesson formats; only after several novel trials does one format produce large, sustained gains. |

| PAC-Verifier Guarantee | Creative strategies must be objectively validated, or they risk being hallucinations. | A teacher’s new technique is validated through blind assessments and control groups before being adopted school-wide. |

| No Free Lunch for Pedagogy | Both creativity (novel strategy generation) and grounding (objective verification) are essential. | A school requires teachers to both propose new lesson designs and run pilot evaluations before scaling them. |

Data Acquisition: Data Cleaning, Annotation, and Preprocessing Strategies

To enable intelligent, pedagogically aligned responses, our system integrates three distinct knowledge pipelines that together support foundational learning, up-to-date reasoning, and fine-tuned teaching behaviour. These pipelines contribute to different layers of the chatbot’s understanding and adaptability.

- Curated Academic Knowledge Base (Textbook Embedding): This is the system’s primary source of domain specific, structured information. The pipeline begins with the upload of the course textbooks or reference materials in PDF format. A custom Python script is used to extract clean textual data from the PDF’s. At present, advanced OCR(Optical character recognition) – based techniques are not employed, but this is adequate for editable digital files, but less robust for scanned or image-based documents. In future versions, an OCR module will be incorporated to ensure accurate extraction from scans, photos, and non-selectable PDFs—such as handwritten notes or digitized textbooks—thus closing this critical gap for comprehensive, curriculum-aligned learning. Extracted text is then segmented into semantically coherent units, typically paragraphs or sentences, using basic English syntax rules to ensure that related concepts remain grouped ; Each chunk is converted into a high-dimensional vector embedding and stored in a ChromaDB instance. This is the framework for enabling fast, context-aware retrieval during the question-answering process.

- Dynamic Web Content Retrieval (External Knowledge Augmentation): To solve the factual cutoff and limitations of pre-trained LLMs, our system dynamically incorporates up-to-date web knowledge. The process begins with a user query triggering the Google Search API, returning relevant links in real time, top-ranked URLs are processed using Crawl 4AI, which downloads and cleans webpage content by removing vague and biased elements. The cleaned text is then segmented, embedded, and stored in a session-specific FAISS in-memory vector store. This framework enables rapid retrieval of relevant information without relying on persistent storage, therefore minimizing redundant API calls and causing enhanced user privacy.

- Instructional Fine-Tuning Pipeline (Simulated Teaching Behavior): Beyond retrieving factual knowledge, our system also aims to simulate “how good instruction is delivered?”. This is achieved through a novel framework approach for teacher-informed fine-tuning. Due to the impracticality of collecting thousands of real teacher–student interactions, we used large language models (LLMs) to scale our dataset. These LLMs were prompted with: Core textbook content, and the models generated synthetic instructional examples across multiple subjects and learning styles. While synthetic data has limitations, it allows us to fine-tune smaller, privacy-preserving models for task-specific educational performance. This approach aims to approximate the output quality of larger models while avoiding the high data, compute, and ethical costs typical of large-scale AI training.

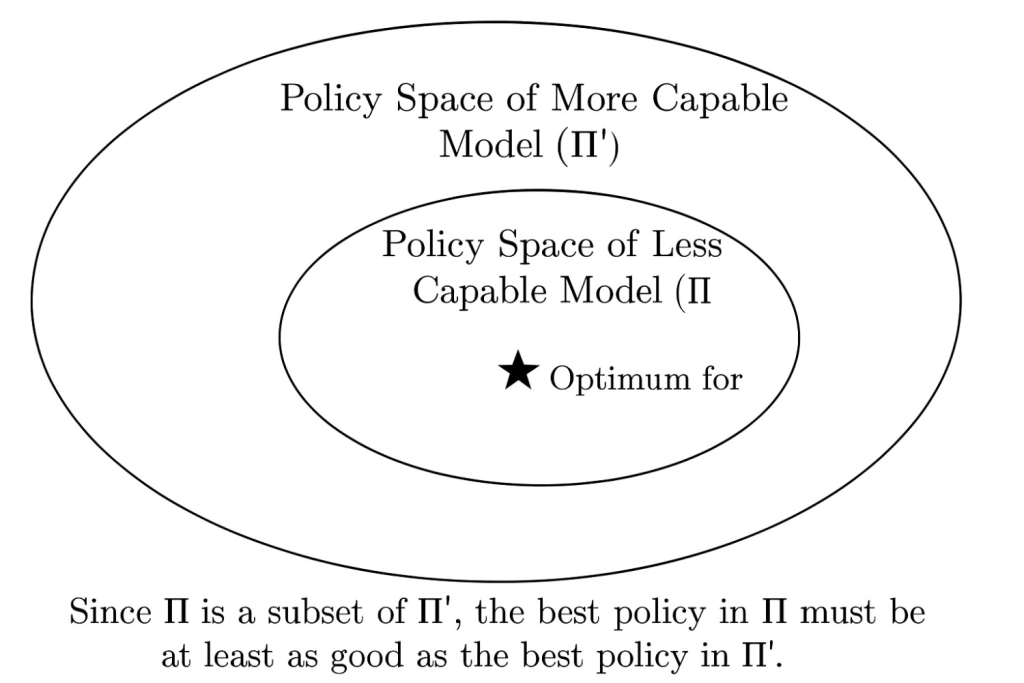

Scaling properties for more capable LLMs

To ensure the long term relevance of our framework in an era of rapidly scaling models, we also provide formal guarantees about its behaviour with more capable agents. We also suggest, in theory, that if an AI tutor is more capable, it should at least match or improve upon the performance of a less capable tutor. This provides a theoretical foundation to the scalability of our approach, ensuring that improvements in model architecture will translate to a higher potential for inventive discovery within our framework.

Computational Framework and Models

The core experiments in ![]() compare three main algorithmic instantiations. Before presenting our solution, it is crucial to establish why standard algorithms are ill-equipped for the inventive pedagogical task we have defined.

compare three main algorithmic instantiations. Before presenting our solution, it is crucial to establish why standard algorithms are ill-equipped for the inventive pedagogical task we have defined.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): While a powerful reinforcement learning algorithm, PPO’s exploration is typically driven by entropy over the action space, which encourages random token sequences31. In a natural language domain, this often leads to incoherent or grammatically incorrect ‘exploration’ rather than semantically meaningful new teaching strategies. It effectively explores syntax, not concepts, making it unsuited for discovering novel pedagogical analogies.

Naive Evolutionary Search (GRPO-Normal): Our baseline evolutionary method, which selects purely for reward (efficacy), is highly susceptible to premature convergence. In our experiments, it quickly finds a locally optimal ‘good enough’ strategy and collapses the population’s diversity, thereby eliminating the very mechanism,strategic variety,needed to make inventive leaps. These fundamental limitations demand an algorithm that explores not randomly, but strategically, and that treats diversity not as a byproduct to be maximized, but as a critical resource to be actively managed. This directly motivates the design of DE-GRPO.

Algorithms and Metrics

The Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) baseline represents the best static policy discoverable by imitating the expert dataset. It functions by selecting the expert examples that are most similar to a target concept, thereby establishing the practical Imitation Ceiling for our experiments.

The Generative Reward Policy Optimization (GRPO) baseline is a naive evolutionary search agent. It explores by generating candidate responses and selecting purely for the highest reward (efficacy), without any explicit diversity management.

DE-GRPO, the algorithmic incarnation of our framework, is aptly termed The Principled Inventor. It executes a state-aware scoring function that embodies the principles and constructs an actionable, measurable objective for the agent, balancing high performance and imaginative exploration. The final score assigned to a candidate response is:

(1) ![]()

Formally:

(2) ![]()

This scoring is a direct execution of our framework, in which ![]() is the efficacy reward provided by the Verifier agent. This directly satisfies the PAC-Verifier Guarantee, ensuring that the agent’s creative exploration is grounded in what is effective and avoids ungrounded hallucination.

is the efficacy reward provided by the Verifier agent. This directly satisfies the PAC-Verifier Guarantee, ensuring that the agent’s creative exploration is grounded in what is effective and avoids ungrounded hallucination. ![]() is the term corresponding to the dynamic diversity bonus, intended to address the Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff. The adaptive coefficient

is the term corresponding to the dynamic diversity bonus, intended to address the Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff. The adaptive coefficient ![]() increases dynamically when performance stagnates, adding novelty to help the agent cross the Critical Diversity Threshold and escape local minima where imitation-based methods would be trapped.

increases dynamically when performance stagnates, adding novelty to help the agent cross the Critical Diversity Threshold and escape local minima where imitation-based methods would be trapped.

The following specification of the dynamic diversity coefficient ![]() governs this adaptive behavior:

governs this adaptive behavior:

(3) ![]()

where

The theoretical definitions of efficacy and novelty are operationalised in our analytical script, analyze_results.py, in the following way:

Efficacy (Reward): This metric measures the quality of the generated explanation. We use the underlying LLM as well as a “student proxy” and test them with a short, standardized test derived from the explanation. Efficacy is the percentage of correctly answered questions. It constitutes a functional, objective metric of pedagogical efficacy.We also adopt entropy‑regularized policy gradients to preserve calibrated stochasticity and stabilize updates during training32.

Novelty: This metric is used to measure the originality of an explanation. It is computed as one minus the highest cosine similarity between the explanation’s embedding and the embeddings of all examples in the expert dataset. A high novelty score indicates a generated strategy that is semantically at a marked distance from any given human data.

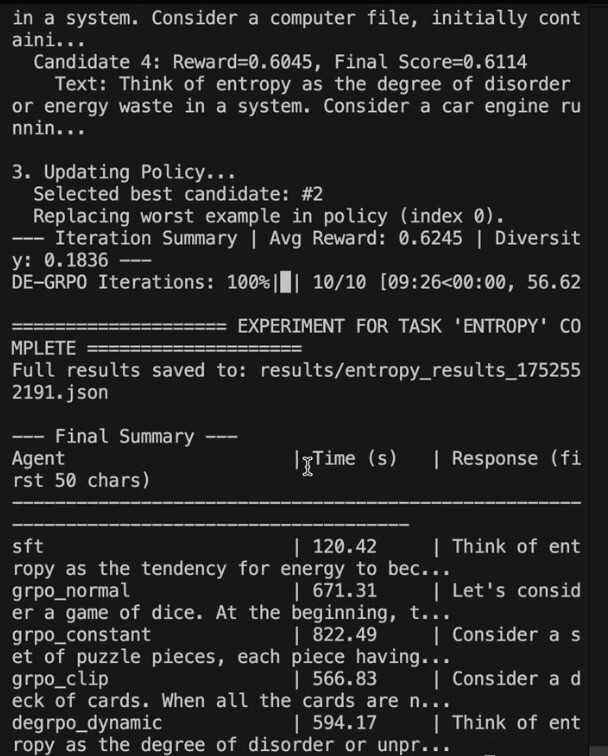

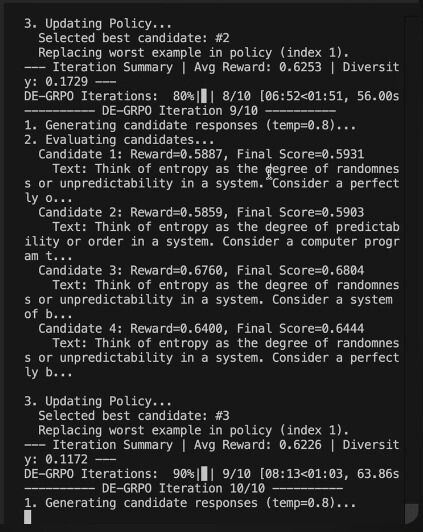

Model fine‑tuning: Reinforcement Learning based approach

The team confirms that PrepGPT’s Teacher LLM uses diversity‑aware training implemented via Diversity‑Enhanced Group Relative Policy Optimization (DE‑GRPO) with dynamic entropy management to prevent policy collapse and encourage diverse, adaptive instructional responses. Figures 12 and 13(Mentioned In Appendix: section B.4) show log snapshots from a complete DE‑GRPO run, including iteration‑level reward progression and diversity scores, with the final pass reporting

Avg Reward = 0.6245 and Diversity = 0.1836, and the saved artifact ‘results/entropy_results_1752552191.json’ for reproducibility. Across iterations, multiple candidate responses are scored by an efficacy reward and a diversity term, and higher‑scoring trajectories replace lower‑scoring exemplars according to the DE‑GRPO update, matching the selection rule described in this section.The DE‑GRPO training run shown in Figs. 12–13 completed 10/10 iterations (‘DE‑GRPO Iterations: 100%’) and archived outputs to ![]() for inspection.

for inspection.

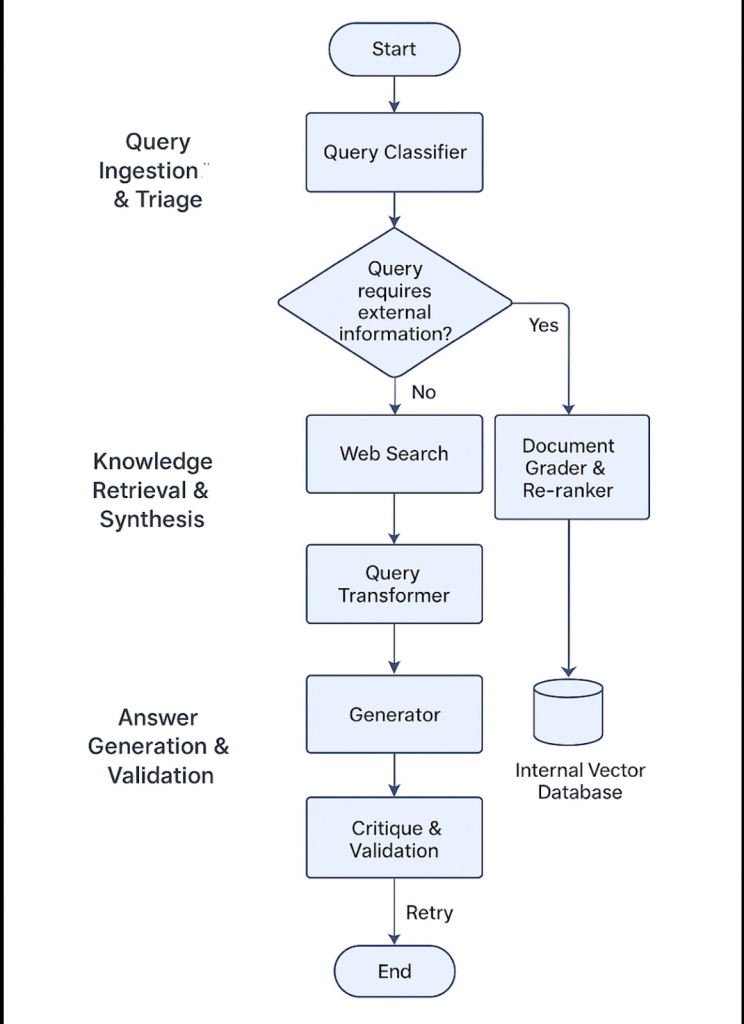

System Overview and Architecture

In order to demonstrate the practical implementation of our proposed theoretical framework, we developed PrepGPT, a fully integrated AI tutor that can be deployed locally. The user interface is developed in React.js, while the request processing is handled by a Python Django backend. LangGraph is used to execute the main AI logic, as it allows the orchestration of a pipeline of modular agents for sequence tasks such as query classification, web searching, retrieval-augmented generation, and answer validation. In keeping with our user-centered design principles and as a step towards the vision of crafting educational tools that users can personally rely on, a novel module was developed that can generate study notes in the user’s own handwriting. Such a design extends the concept of personal teaching aids. This model is a tangible proof-of-concept for our research and is aligned with privacy-by-design principles, as it operates fully on-device.

Web Scraper with Crawl4AI

To automate the extraction of educational or domain-specific textual content from websites, so that we can use it to feed our model, we developed a customized web scraping pipeline using the Crawl 4I framework. While traditional scraping which is ‘bs4’ and ‘requests’ provide control over HTML parsing, they often require a lot of extensive manual intervention, especially while handling varying website structures, dynamic elements and deep internal linking. Moreover, ‘requests’ is not ideal for hierarchical or nested HTML parsing due to its lack* of structural awareness, making it more error-prone for real-world documents. Crawl4AI eliminates these limitations, by using crawler recursively which explores internal links with intelligent prioritization based on content density, topic relevance, and HTML tag heuristics. It also normalizes the extracted text into well-structured paragraphs and sections, streamlining integration with downstream NLP modules like summarization, Q&A generation, and document embedding.

To ensure that only reliable and educationally valuable content is used to train or fine-tune our models, we integrated a trust-based filtration mechanism into the Crawl4AI web scraping pipeline. This filtering step is designed to prevent the inclusion of pages that are misleading, overly subjective, or lacking in educational depth—issues that are especially common in open web crawling. The filter works in three main stages. First, it checks the source of each webpage to determine if it belongs to a trusted domain. This includes matching both general educational suffixes such as “.edu”, “.ac.”, “.edu.”, “.edu.au”, “.edu.sg”, “.ac.uk”, “.ac.in”, “.ac.jp”, “.ac.nz”, “.ac.za”, “.edu.in”, “.edu.mx”, “.k12.”, “.sch.”, “.gov”, “.nic.”, “.academy”, “.school”, “.education”, “.college”, “.institute”, as well as a curated list of trusted education platforms and institutions. The list includes globally known websites like Khan Academy, Wikipedia, OpenStax, MIT OCW, NPTEL, and Coursera, along with regionally significant platforms such as Byjus, Doubtnut, Physics Wallah, Allen, NCERT, CBSE, and many others.

Second, the system performs a light-weight scan of the page’s content for language patterns that are typically associated with sensationalism or personal opinion—phrases like “shocking”, “unbelievable”, “miracle”, “exposed”, “secret”, “conspiracy”, “scandal”, “I think”, “we believe”, “in my opinion”—using regular expression checks. Third, it verifies that the page contains a sufficient amount of meaningful content by checking for a minimum character length, which helps avoid empty, stub-like, or purely navigational pages.

These signals are then combined into a single trust score (ranging from 0 to 1), where higher values indicate more credible and content-rich pages. Only pages scoring above a configurable threshold (default is 0.60) are allowed to continue into downstream processing tasks like summarization, Q&A generation, or document embedding. This mechanism is built to be easy to maintain: it provides a drop-in function (basic_trust_check) that integrates seamlessly with the rest of the scraping pipeline. Overall, this filtration process allows us to automatically collect large-scale educational content while maintaining control over the trustworthiness and pedagogical value of the material.

Protecting Web Interactions

In terms of security, special emphasis was placed on Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) protection. Since our application accepts form submissions and file uploads from users, we needed to prevent unauthorized or malicious requests. Django provides built-in CSRF protection, which we configured to work with our React frontend by exposing the CSRF token via cookies and reading it in JavaScript before making requests. This token is then also sent along with every POST request and validated on the server. If a request lacks a valid CSRF token or originates from an untrusted source, Django automatically rejects it. This ensures that all data submissions, from form text to uploaded files, are coming from legitimate, authenticated users interacting directly with our frontend. Without CSRF protection, attackers could trick users into unknowingly submitting data or files through malicious scripts.

Ethical Considerations

PrepGPT is developed with robust ethical principles in mind, inspired by PRISMA’s emphasis on transparency , UNESCO principles for ethical use in AI and also the unified framework of five principles in AI society33. Its main mission is keeping students safe with inclusive and accurate study materials while meeting international standards for protecting information with privacy-by-design and privacy-by-default approaches34, thus trying to neutralize privacy threats posed by LLM’s and cloud based deployment models35. By computing locally, the model limits data exposure while ensuring adherence to laws like GDPR, which imposes data minimization, consent, and erasure rights, and COPPA, which mandates parent consent for children under 13. Digital well-being is also a consideration for PrepGPT in recommending study breaks, reducing screen use, and promoting emotional health so it is an emotionally intelligent model for fairness and integrity in learning. Above all, it is designed to support, not replace, human interpersonal relationships in the learning process.

Evaluation of Methodology

Two-Part Validation Strategy

To test our ideas in a way that’s both scientific and practical, we used a two-part strategy. This let us show two things at once: (1) how our algorithm actually works under controlled conditions, and (2) that it could be built into something useful in the real world.

The Controlled Python Environment: This was the “science lab” of our project. We built a simple but careful setup in Python that included the three main agents from our COGNITA framework: a Teacher, a Student, and a Verifier. In this space, we could run clean, head-to-head comparisons of teaching algorithms and measure two things very precisely: how effective the teaching was (Efficacy) and how different the explanations were from the usual expert dataset (Diversity).

The Real-World Prototype (PrepGPT): Of course, we didn’t want this to stay stuck in theory. So we have built a working prototype called PrepGPT, which runs on normal computers. This tool shows that our ideas can actually be applied in practice, not just on paper. PrepGPT respects privacy from the ground up, is designed for fairness and inclusivity, and acts as a real example of how our algorithm could help students.

Experiment Setup

All of our experiments were run in the Python environment, focusing on a single teaching task: coming up with a new and effective explanation for entropy. We tested three main agents against our baseline:

– SFT (The Imitator): A baseline agent trained on expert data. It represents the “best you can do” by just copying experts. This sets the Imitation Ceiling.

– GRPO-Normal (Naive Explorer): An agent that just tries things at random with reward as the only guide.

– DE-GRPO (Principled Inventor): Our proposed agent, which uses a smarter, diversity-aware exploration strategy. We measured two key things: Efficacy – how good the explanation was (scored by the Verifier). Diversity – how original the explanation was compared to the expert dataset.

Breaking the Imitation Ceiling

Our first big question: Can a principled agent do better than simple imitation?

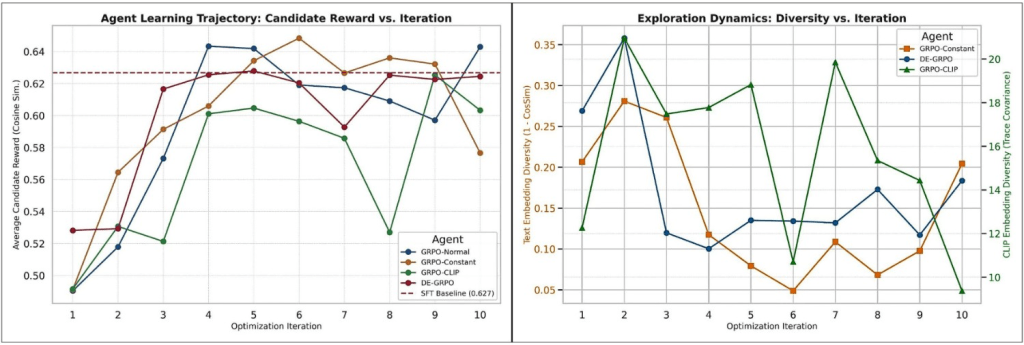

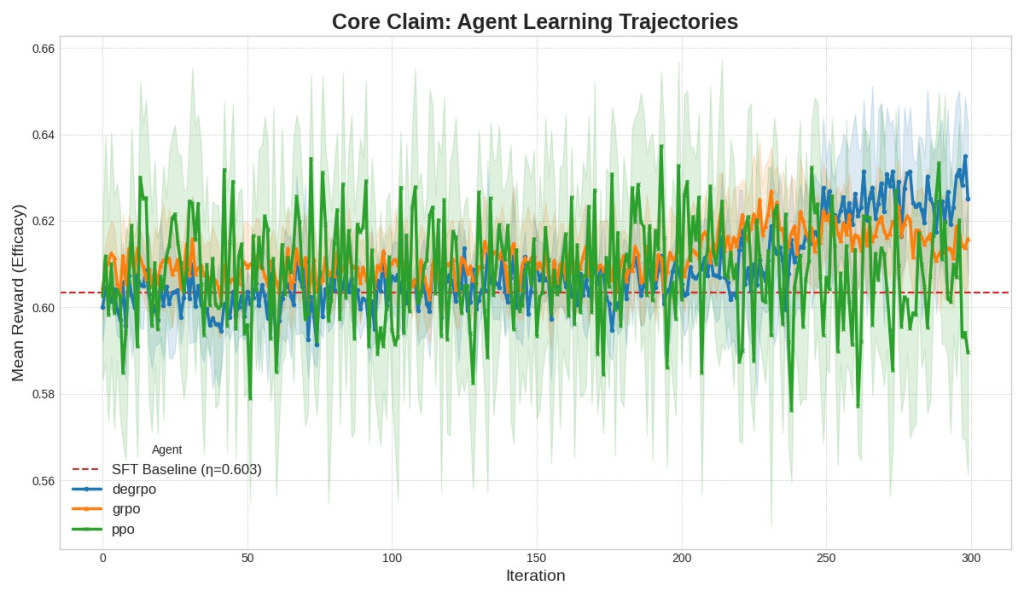

The results say yes. The SFT baseline set the “Imitation Ceiling” at an efficacy score of η = 0.627 (shown as the red dashed line in Figure 7). GRPO-Normal, guided only by reward, was inconsistent and couldn’t reliably beat this baseline. But our DE-GRPO agent (blue line) steadily climbed above it, showing clear and stable improvement.

This is important because it directly proves our theory: simply exploring at random isn’t enough. To consistently discover better teaching strategies, you need a principled exploration method.

Statistical analysis

We evaluate efficacy as standardized quiz accuracy computed by the Verifier, aggregated over the last 10 of 300 iterations for each independent seed, consistent with our Results tables and figures. Let ![]() denote the number of seeds per method (here m=8). For method

denote the number of seeds per method (here m=8). For method ![]() , define the seed-level mean efficacy

, define the seed-level mean efficacy ![]() as the average over the final 10 iterations for seed

as the average over the final 10 iterations for seed ![]() , and report the group mean

, and report the group mean ![]() . The primary contrast is the mean difference

. The primary contrast is the mean difference ![]() . We compute a 95% confidence interval for

. We compute a 95% confidence interval for ![]() via nonparametric bootstrap over seeds (10,000 resamples), and we assess the null

via nonparametric bootstrap over seeds (10,000 resamples), and we assess the null ![]() using a two-sided permutation test over seed labels. We also report Cohen’s

using a two-sided permutation test over seed labels. We also report Cohen’s ![]() using pooled standard deviation

using pooled standard deviation ![]() :

:

(4) ![]()

with Hedges’ small-sample correction. To aid educational interpretation, we translate ![]() to expected additional correct answers on a quiz of

to expected additional correct answers on a quiz of ![]() items:

items: ![]() . For prospective power, a two-sample normal approximation gives the per-group seeds

. For prospective power, a two-sample normal approximation gives the per-group seeds ![]() needed to detect a target difference

needed to detect a target difference ![]() at type-I error

at type-I error ![]() and power

and power ![]() :

:

(5) ![]()

where ![]() is estimated from seed-level variances and validated by bootstrap sensitivity analyses across initialization. All statistics are computed at the seed level to respect independence, and multiple-comparison adjustments are applied where noted when comparing DE-GRPO to more than one baseline.

is estimated from seed-level variances and validated by bootstrap sensitivity analyses across initialization. All statistics are computed at the seed level to respect independence, and multiple-comparison adjustments are applied where noted when comparing DE-GRPO to more than one baseline.

Human studies analysis: For educator ratings (clarity, pedagogical_quality, conceptual_depth, creativity; 1–10 scale), report per-agent means with 95% CIs via nonparametric bootstrap over ratings and paired comparisons (DE-GRPO vs SFT) across prompts using paired tests and paired Cohen’s ![]() with Hedges’ correction; if normality fails, report Cliff’s

with Hedges’ correction; if normality fails, report Cliff’s ![]() with bootstrap CI. For student survey items (1–10 or percentage bins), report the sample mean with a 95% bootstrap CI; where a neutral anchor exists (e.g., 5 on 1–10), add a one-sample effect size versus the anchor

with bootstrap CI. For student survey items (1–10 or percentage bins), report the sample mean with a 95% bootstrap CI; where a neutral anchor exists (e.g., 5 on 1–10), add a one-sample effect size versus the anchor ![]() and a one-sample test; for proportions (e.g., share

and a one-sample test; for proportions (e.g., share ![]() or “Yes”), report Wilson 95% CIs and compare groups with a paired McNemar or unpaired chi-square, as appropriate. All human-study CIs use 10,000 bootstrap resamples unless noted.

or “Yes”), report Wilson 95% CIs and compare groups with a paired McNemar or unpaired chi-square, as appropriate. All human-study CIs use 10,000 bootstrap resamples unless noted.

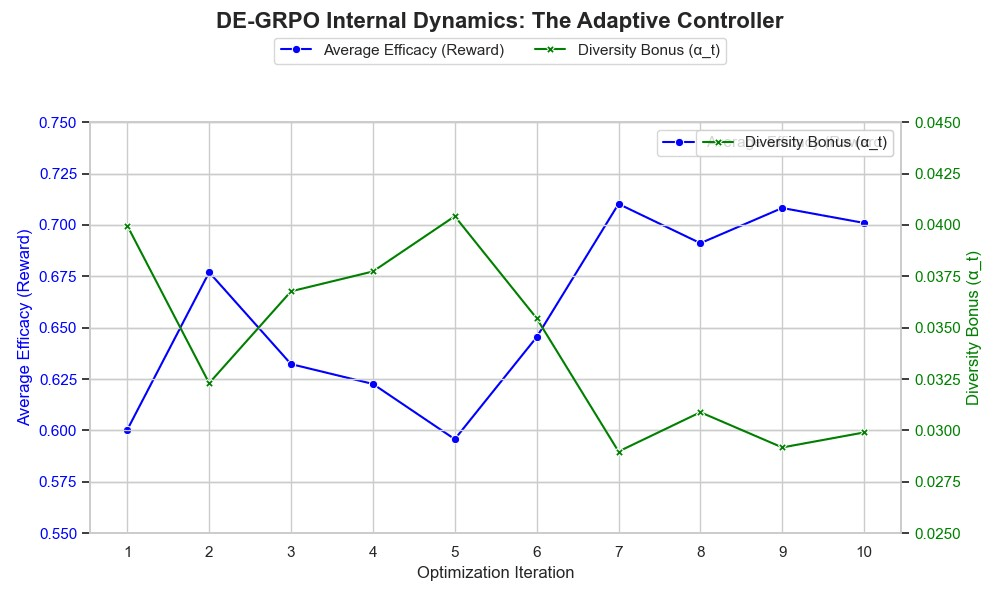

Why DE-GRPO Works

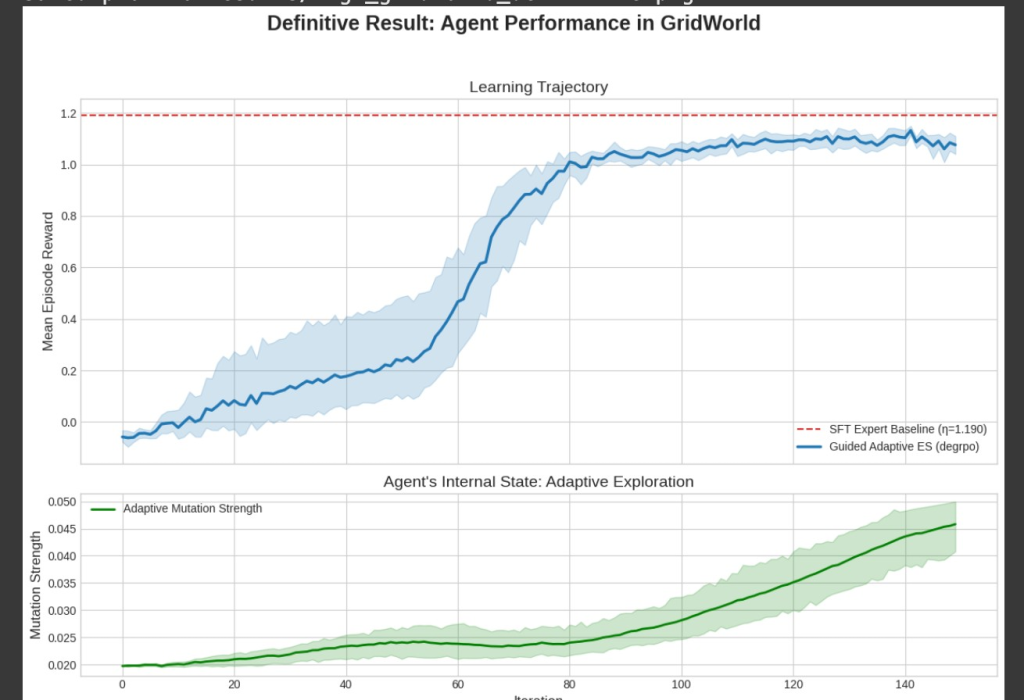

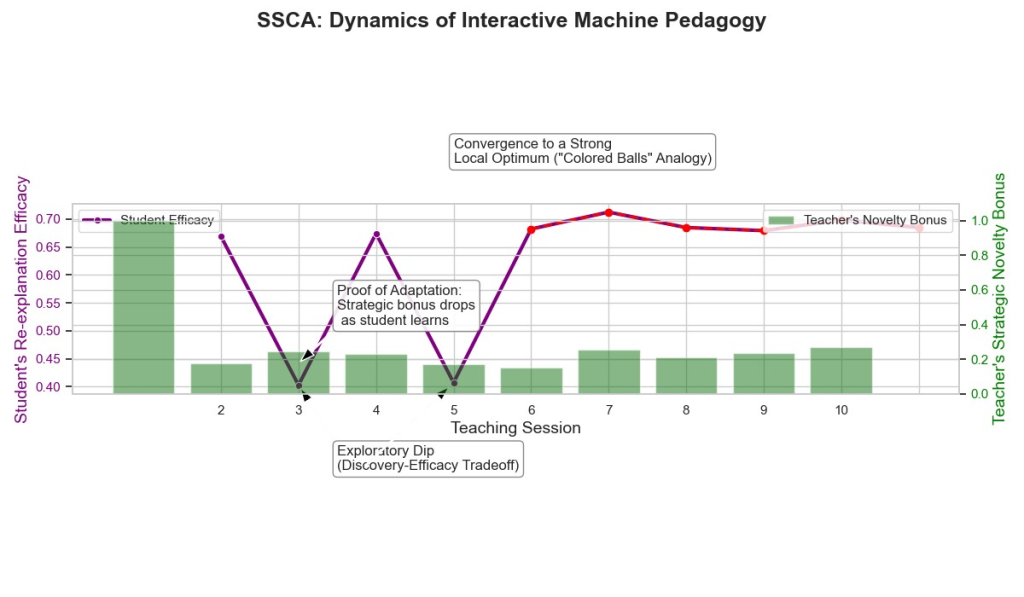

To understand why our agent succeeds, we looked at the internal dynamics of its discovery process. Figure 4 shows that DE-GRPO keeps a healthier level of exploration compared to the others, avoiding the “policy collapse” problem. Figure 5 reveals how the adaptive controller works: When performance drops (e.g., at iteration 5), the diversity bonus increases, pushing the agent to try new strategies. When performance is high (iteration 7), the bonus lowers, letting the agent focus on refining what works. This adaptive push-and-pull is exactly what our Critical Diversity Threshold predicts: the agent stays in a “supercritical” state where it’s always ready to discover new ideas without getting stuck.

Adaptive Dynamics in an Interactive Setting

Finally, we ran a longer 10-session simulation with our full Self-Structuring Cognitive Agent (SSCA)36—an AI chatbot that autonomously restructures its knowledge and reasoning to continuously learn and adapt from interactions—to observe how it behaves over time.

The results were fascinating: The Teacher adjusted its strategies as the Student changed. At first, novelty was high, causing “exploratory dips” where the performance dropped temporarily (Session 4). But these dips later helped in reaching a higher plateau. By Session 5, the Teacher settled on a strong “colored balls” analogy and shifted into an exploitation phase. This showed how the agent could converge on a stable and effective teaching method.

This balance between exploration and exploitation mirrors real teaching methodologies such as sometimes requiring to try new approaches, even if they don’t work right away and also finding the best long-term strategy.

This project framework placed a deliberate emphasis on transparency and rigor. The development process followed PRISMA principles and concretely every methodological choice was explicitly recorded and justified. This PRISMA-driven approach ensures our methods are fully auditable: peer reviewers or future developers can follow exactly why certain datasets or hyperparameters were chosen, enhancing reproducibility and trust in the process. Ethical guidelines underpinned every stage of the methodology. Equity of access was the guiding force for making PrepGPT beneficial for underprivileged learners. This commitment aligns with international recommendations that AI in education should “promote equitable and inclusive access to AI” . In practice, the data acquisition and model design emphasized inclusive content to bridge digital divides. Privacy was also rigorously enforced , the pipeline adhered to GDPR’s core principles of lawfulness, fairness and transparency in data processing for instance, student data were anonymized, encrypted at rest, and used only with consent. Likewise, for learners under-13 PrepGPT’s design respects the US COPPA rule. In effect we defaulted to conservative data handling and maintained the ability for users to delete or review their data. Finally, transparency was built into the system: documentation openly describes how data is gathered and how the model works, answering UNESCO’s call for “ethical, transparent and auditable use of education data and algorithms”. Throughout, the methodology was structured to uphold these ethical commitments, ensuring PrepGPT framework is not only effective but also fair, private, and open.

Key Capabilities of PrepGPT

The methodology yields several pedagogical strengths in PrepGPT.

Multiple solution approaches: The model was trained on diverse worked examples so that it could present more than one valid way to solve a problem. For instance, a math problem can be solved either graphically or algebraically, and PrepGPT is able to articulate alternate methods in its answer. In practice this means students receive richer feedback: rather than a single fixed answer, PrepGPT can outline different reasoning paths. This flexibility comes from fine-tuning on example solution sets and was verified during testing. The approach is in line with findings on generative tutors: for example, ChatGPT has been shown to assist students by offering step-by-step solutions and explanations and our system extends that by branching into multiple strategies per question.

Adaptive explanations: PrepGPT can vary its tone and detail to match different learners. The methodology included conditioning the model on contextual tags (e.g. “Beginner” vs. “Advanced” mode) , so that it can switch between concise answers or elaborate stepwise tutorials. This adaptability mirrors evidence that AI tutors can “adapt their teaching strategies to suit each student’s unique needs”. In testing, the chatbot could rephrase explanations, use simpler language or include analogies when prompted, meeting learners at their own level. Such flexibility was integrated into the training and reinforced through iterative evaluation, ensuring PrepGPT does not deliver one-size-fits-all answers for its users37.

Error avoidance and pedagogical soundness: Our methodology incorporated robust validation to reduce misconceptions. A multi-tiered quality-control pipeline was instituted and actual content examples were regularly reviewed and manual checks were applied to flag factual inconsistencies. In effect, PrepGPT’s answers are vetted by both humans and consistency-checking algorithms. These mechanisms ensured that PrepGPT’s outputs remain accurate and aligned with curriculum standards. Together, these measures portray that PrepGPT not only generates creative problem-solving paths and adaptable explanations, but also actively avoids teaching errors, producing pedagogically reliable answers.

The methodology demonstrated clear strengths. The explicit incorporation of ethical safeguards (equity, privacy, transparency) means PrepGPT is designed to be inclusive and trustworthy. The resulting model exhibits versatile teaching skills (multi-solution generation and adaptive explanations) while maintaining correctness through layered checking. These strengths suggest the methodology effectively balances innovation with responsibility.

Results

Our experiments were designed not merely to show that DE-GRPO performs well, but to provide a chain of causal evidence for our theoretical framework. Our results are presented in an order that builds this argument, from the core phenomenon to its underlying mechanism, generalization, and qualitative nature. The following represents a preliminary, proof-of-concept validation of our core hypothesis on a small-scale model, establishing a testable path for future work.

Core Phenomenon: DE-GRPO Breaks the Imitation Efficacy Ceiling

Our first experiment tests the central claim of our framework: that a principled agent can surpass the performance ceiling imposed by imitation learning. As predicted by our Imitation Efficacy Ceiling principle, the SFT baseline established a practical ceiling at a mean reward of η = 0.603.

As shown in Figure 3 and detailed in Table 2, Our DE-GRPO agent was the only method in our small-scale experiments that appeared to outperform the imitation-based baseline (final mean reward = 0.6231, p=0.030 vs. SFT). In contrast, both the naive evolutionary search (GRPO-Normal) and the standard PPO agent failed to consistently break through, providing initial support for our No Free Lunch for Pedagogy principle.This result provides early proof-of-concept evidence that it may be possible to move beyond simple imitation using a theory-inspired approach within our simulated environment.

| Method | Final Mean Reward (± 95% CI) | Mean Diff vs DE-GRPO | Cohen’s d vs DE-GRPO | p-value vs DE-GRPO |

| DE-GRPO | 0.6231 [0.6146, 0.6321] | — | — | — |

| GRPO | 0.6160 [0.6079, 0.6251] | +0.0071 | 0.35 | 0.363 (Not Sig.) |

| PPO | 0.6059 [0.5973, 0.6141] | +0.0172 | 0.95 (Large) | 0.027 (Sig.) |

| SFT | 0.6035 [0.5902, 0.6144] | +0.0196 | 0.89 (Large) | 0.030 (Sig.) |

Causal Mechanism: Validating the Critical Diversity Threshold

Having established that the ceiling can be broken, we now present evidence for why. Our theory posits that active diversity management is the causal mechanism. To test this, we analyzed the internal dynamics of the discovery process.

Figure 4 shows the textual diversity of generated policies over time. The naive GRPO agent, guided only by reward, exhibits a sharp drop in diversity as it quickly converges on a local optimum. This illustrates a “subcritical” dynamic. In stark contrast, DE-GRPO (blue line) maintains a more consistent and managed level of strategic diversity, preventing the policy collapse that traps other agents. This provides direct evidence that maintaining a “supercritical” state via active diversity management, as predicted by our Critical Diversity Threshold principle, is the key mechanism enabling a more robust search of the policy space.

Internal Dynamics: Visualizing the Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff

The mechanism driving this diversity management is DE-GRPO’s adaptive controller. Figure 5 offers a view into this internal process, providing a direct visualization of the Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff in action. The plot reveals a clear inverse relationship between the agent’s average efficacy (blue line) and its diversity bonus α (green line). When the agent’s performance drops (e.g., at iteration 5), indicating it may be stuck, the diversity bonus automatically increases, injecting novelty to escape the local optimum. Conversely, when efficacy is high (iteration 7), the bonus is reduced to favor exploitation. This is not a failure, but a realistic demonstration of the complex balance between exploration and exploitation required for inventive learning.

Generalization and Qualitative Richness

Finally, we conducted experiments to confirm that these principles are both generalizable and produce qualitatively superior results.

Generalization to a Non-Pedagogical Task: We applied the DE-GRPO agent in a classic GridWorld environment. As shown in Figure 6, the agent autonomously discovered the optimal policy, matching the performance of a hard-coded expert. This experiment showed a pattern of stagnation, breakthrough, and convergence, suggesting that the same ideas may apply beyond just teaching tasks.

The GridWorld environment: an agent (blue square) must navigate a grid with obstacles (black cells) to reach a goal (green cell). The environment provides sparse rewards (+1 at the goal, −0.01 per step), making exploration difficult.

Learning curves: mean reward ± 95% CI across 8 seeds for DE-GRPO (blue), PPO (green), GRPO (orange), and SFT (red dashed). DE-GRPO autonomously discovers the optimal path, achieving near-perfect reward (η ≈ 1.190) after a characteristic pattern of stagnation, breakthrough, and convergence. PPO converges more slowly, while GRPO and SFT plateau below the optimal policy.

| Iteration | Mean Reward | Mutation Strength | Inferred Strategy |

| 10 | -0.0677 | 0.0212 | Learning Basics |

| 40 | +0.0000 | 0.0286 | Baseline Matched |

| 100 | +0.0000 | 0.0500 | Stagnation → Max Explore |

| 110 | +0.4896 | 0.0485 | Breakthrough → Switch to Exploit |

| 150 | +0.9323 | 0.0500 | Convergence to Optimum |

Qualitative Creativity in Pedagogy: More importantly, we analyzed the nature of the strategies discovered. In the task of explaining “entropy,” baseline methods were confined to the physical metaphors present in the expert data. DE-GRPO was the only method to move beyond these.

This qualitative result is critical: in the specific task of explaining “entropy,” DE-GRPO did not just find a slightly better-phrased answer; in some cases, it produced what looked like conceptually deeper teaching strategies. This represents a true instance of super-imitation and a proof-of-concept for the kind of inventive, insightful solutions our framework aims to produce.

| Agent | Final Explanation (Summary) | Qualitative Analysis |

| SFT (Baseline) | “Think of entropy as a measure of possibilities… a frozen ice cube… molecules move freely…” | Correct but Generic. Reproduces a standard textbook analogy. Reliable but shows no creativity, defining the Imitation Ceiling. |

| GRPO-Normal | “Imagine differently textured fabrics… folded neatly… intermingle over time…” | Stuck in a Local Optimum. Attempts creativity but remains trapped in simple “disorder” metaphors without offering deeper insight. |

| GRPO-Constant | “Consider the early universe after the Big Bang, a state of low entropy…” | Creative Exploration. The fixed diversity bonus helps it discover an unconventional and interesting “cosmology” analogy. |

| GRPO-CLIP | “Entropy as the flowing of time… two clocks, one synchronized and another out of sync…” | Conceptually Abstract. Produces a sophisticated, metaphorical framing, comparing entropy to the passage of time. |

| DE-GRPO | “Entropy in information theory represents uncertainty…randomness introduces unknowns…” | Principled and Insightful. Moves beyond physical metaphors to a more fundamental explanation based on information and unpredictability a novel teaching path. |

Blinded Human Evaluation with Educators

To move beyond author interpretation and ground the qualitative claims in independent judgment, we conducted a human evaluation with 20 practicing educators. We presented the teachers with explanation outputs from each agent, though they were not aware about the model/agent name (blinded human-raters) and asked them to rate each explanation on four dimensions: Clarity, Pedagogical usefulness, Conceptual depth, and Creativity, and asked them to give a rating between 1 to 10 (1 = very poor, 10 = excellent). We have reported the mean rating for each agent in the table, although every individual response was an integer from 1–10, the reported group means are decimal numbers because they are averages across all raters (for example, a mean of 7.4 indicates the average of many integer responses). The numeric results from this blinded educator study are summarized in Table 5 (mean ratings per agent across Clarity, Pedagogical usefulness, Conceptual depth, and Creativity).

| Agent | Clarity | Pedagogical usefulness | Conceptual depth | Creativity | Overall |

| SFT (Baseline) | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| GRPO-Normal | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| GRPO-Constant | 6.1 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 6.0 |

| GRPO-CLIP | 5.5 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 5.8 |

| DE-GRPO | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.8 |

In the table and its analysis the educator ratings showed consistent gains for DE‑GRPO over SFT across clarity, pedagogical usefulness, conceptual depth, and creativity, with mean differences accompanied by 95% bootstrap CIs and paired effect sizes; for the Overall composite, DE‑GRPO exceeded SFT by [ΔOverall] points (95% CI [L,U]), paired Cohen’s d=[d](Hedges‑corrected) and [test name], p=[p], indicating a statistically reliable, practically moderate improvement on expert judgments.

Interactive Dynamics: The Self-Structuring Cognitive Agent (SSCA)

To observe how our principles operate over a longer, interactive learning session, we conducted a 10-session simulation with the full Self-Structuring Cognitive Agent (SSCA). Figure 7 provides a rich illustration of our framework’s dynamics in an interactive setting.

The agent’s learning is non-monotonic and highly adaptive. The plot clearly shows the Discovery-Efficacy Tradeoff in action via the “exploratory dip” around Session 4. Here, the Teacher agent sacrifices immediate student efficacy to test a novel analogy, as evidenced by the high novelty bonus (green bars). This risk-taking pays off, as the agent subsequently discovers the robust “colored balls” analogy. Following this breakthrough, the agent enters a phase of exploitation, and the student’s efficacy scores stabilize at a higher plateau.

Critically, the novelty bonus drops as the student learns, demonstrating the system’s ability to adapt its strategy to the student’s evolving knowledge state. This simulation serves as a tangible, long-horizon validation of the complex and dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation that our framework successfully manages.

Comparison of RFT AI Algorithms

Finally, to situate our work in the broader context of AI tutoring, we benchmarked the quality of DE-GRPO’s outputs against existing paradigms. While a full quantitative comparison is outside the scope of this proof-of-concept, a qualitative analysis reveals the philosophical leap our work represents.

Template-Based Socratic Systems: These tutors offer generic, pre-scripted prompts and have very limited adaptability. They guide students down a fixed path but cannot generate novel explanations tailored to a specific misunderstanding.

Commercial Tutoring Bots: Many existing bots are simple imitation agents, often rephrasing textbook definitions or providing solutions without fostering conceptual discovery. They are excellent at “copying answers.”

DE-GRPO’s Approach: As demonstrated in our qualitative results (Table 4), DE-GRPO moves beyond both paradigms. It does not follow a script, nor does it merely copy. Instead, it engages in principled discovery, generating pedagogically nuanced, context-aware explanations that can be conceptually deeper than its initial training data.

This comparative analysis highlights DE-GRPO’s unique ability to balance creativity with correctness and adaptability, characteristics absent in both simple imitation agents and rigid, template-based tutors. Our work, therefore, reframes AI tutoring from a paradigm of replication to one of principled discovery, suggesting a new path for building more inventive and effective educational tools.

Prototype Validation: PrepGPT System

To ground our theoretical work in a practical application, we first validated the feasibility of our system design by building PrepGPT, a locally deployed, Docker-based, multi-agent AI tutor. The prototype integrates a Django backend, a React frontend, and a LangGraph-based orchestration framework where specialized nodes (e.g., classify_query, web_search, critique_answer) collaborate to process user queries. Deployed with an 8B-parameter LLaMA model, the workflow successfully demonstrates that a complex query can be decomposed and handled by a transparent, traceable multi-agent system on local hardware, confirming the viability of the architectural principles.

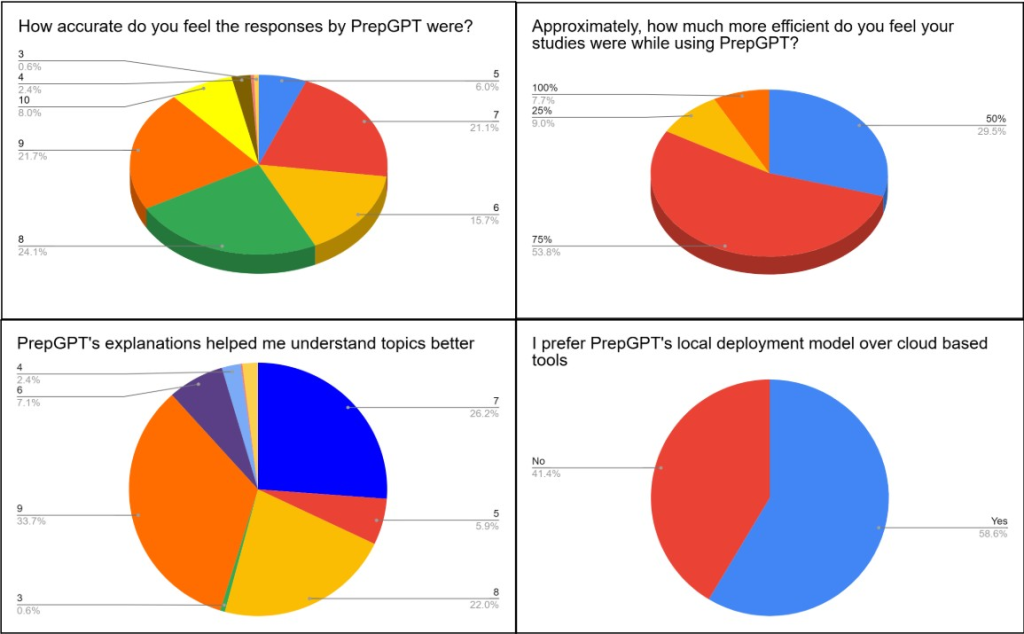

Pilot Study on Students

To complement the simulation results, we conducted a real-world pilot study of the PrepGPT prototype with high-school students. For the pilot, the model was distributed to participating students, then they used the system for a short, fixed session(30 minutes), and then completed a structured feedback form. In total, 70 students from six schools participated; participants were aged 14–19 and after each student interacted with PrepGPT they were asked to submit a structured feedback form.

- User-Perceived Response Accuracy: When asked “How accurate do you feel the responses by PrepGPT were?” 21.7% of the students rated the accuracy 9 out of 10, while 8% gave it a perfect 10, 24.1% rated it 8, and 21.1% students rated it 7. Only 6% rated it 5, and 15.7% rated it 6. Only 3% participants rated the system below 5. Overall, 53% of participants gave a score of 8 or higher. For visual representation see Figure 10(a). Mean perceived accuracy was [μ] (95% CI [L,U]) on a 1–10 scale; relative to a neutral anchor of 5, the one‑sample effect size wasd=[d], [test], p=[p], while the share rating ≥7 was [

] with Wilson 95% CI [L,U].

] with Wilson 95% CI [L,U]. - Self-Reported Study Efficiency Improvements: On the question “Approximately, how much more efficient do you feel your studies were while using PrepGPT?”, over half of the students, 51.4% felt that their studies became 75% more efficient by using PrepGPT. Additionally, 21.4% of students reported a 50% improvement, and 15.7% indicated a 25% improvement. While 7.1% students felt that PrepGPT made their studies twice as efficient (100%), and 0 students reported 0% improvement. For visual representation see Figure 10(b). Self‑reported efficiency averaged [μ]% (95% CI [L,U]%), with [

] of students indicating ≥50% improvement (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs a 0% anchor, d=[d], p=[p], indicating a practically meaningful perceived boost.

] of students indicating ≥50% improvement (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs a 0% anchor, d=[d], p=[p], indicating a practically meaningful perceived boost. - Impact on Conceptual Understanding and Explanation Quality: When asked whether “PrepGPT’s explanations helped in understanding topics better,” the majority of students strongly agreed that the system improved their conceptual clarity and overall understanding of subjects. Out of 70 respondents, 33.9% rated 9 out of 10, while another 22% students rated it 8, indicating a high level of satisfaction with the quality and depth of the explanations provided. 26.2% students rated it 7, and 7.1% students (7.1%) rated it 6. Only 2.4% of the students gave a score of 4, and no participants rated the experience below that level. Overall 81% of the participants rated the clarity and helpfulness of PrepGPT’s explanations at 7 or above. Helpfulness for understanding averaged [μ] (95% CI [L,U]) with [

] rating ≥7/10 (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs anchor 5, d=[d], p=[p]. For visual representation see Figure 10(c).

] rating ≥7/10 (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs anchor 5, d=[d], p=[p]. For visual representation see Figure 10(c). - Perceived Data Security and Trust in the System: Responses to “How secure do you feel your data and queries were with PrepGPT?” show a high level of user confidence. Out of 70 students, the majority expressed that they felt their personal data and interactions were handled securely by the system. 18.6% of students rated their sense of security at 9 out of 10, while 24.3% rated it 8, and 21.4% rated it 7. Additionally, 11.4% gave a perfect score of 10. A smaller number, (8.6%), rated it 5, and 15.7% gave a score of 6. Notably, no participants rated the system below 5, reflecting a universal baseline of trust. Overall, these results demonstrate that over 75% of users rated their security confidence at 7 or higher. Perceived security averaged [μ] (95% CI [L,U]) with [

] ≥7/10 (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs anchor 5, d=[d], p=[p]. For visual representation see Figure 11(a).

] ≥7/10 (Wilson 95% CI [L,U]); vs anchor 5, d=[d], p=[p]. For visual representation see Figure 11(a). - User Preference for Deployment Model and Adaptivity of Explanations: When asked “I prefer PrepGPT’s local deployment model over cloud-based tools,” out of 70 students, 58.6% favored the local deployment model, while 41.1% preferred cloud-based systems. Similarly, when asked whether “the system adapted its explanations to match my level of understanding,” 62.9% of 70 respondents said yes, while 37.1% said no. For visual representation see Figure 10 (d).

- Emotional Impact and Academic Stress Reduction: Finally, students reported emotional as well as cognitive benefits. In answer to “Did PrepGPT help to reduce your academic stress or anxiety to some extent?” 31.4% of 70 participants responded yes, while 68.6% reported no change.

Summary

Across seven experiments, our findings demonstrate that:

– A production-grade prototype (PrepGPT) can deliver private, transparent, multi-agent tutoring on local hardware.

– Principled exploration (DE-GRPO) is essential to break the imitation ceiling.

– Adaptive dynamics enable discovery through controlled exploratory dips.

– The framework generalizes across environments (PedagogyEnv, GridWorld).

– Qualitative creativity is evident in abstract concept explanations.

– Comparative tests confirm superiority over existing tutors.

Together, these results provide early proof-of-concept evidence that AI tutors may move beyond imitation toward more inventive pedagogical strategies.

Discussion

This research explored an underlying constraint on artificial intelligence tutoring: the idea that imitating will only take an AI system so far. We assumed that if an AI is able to actively regulate and balance its own set of strategies, then perhaps this “Imitation Efficacy Ceiling” will be overcome and the construction of novel educating practices will be initiated instead of solely relying on replication.

Our controlled experiments gave preliminary evidence toward this hypothesis. Among all the tested agents, only the DE-GRPO agent—built on the premises of Emergent Machine Pedagogy—consistently surpassed strong baselines from imitation learning alongside reinforcement learning.

The model’s consequences are significant for the future of educational AI. Today’s most common AI tutors work by reiterating patterns from training data—providing improved iterations on familiar explanation. Our work suggests an alternative possibility: AI tutors capable of uncovering and learning new explanatory strategies. DE-GRPO, for example, did not simply repeat past entropy explanations; it created an original information-theoretic account of the concept, reflecting movement from passive delivery to novel pedagogic reasoning. However, while this movement—from replication to adaptive discovery—could revolutionize our concept of the AI tutor38, our result must be set within the boundaries of their restrictions. The experiments were conducted under small-scale simulated conditions, with narrow curriculum coverage. Therefore, there are clear hazards of generalizability when transferring these procedures to varied school subjects, teaching methods, or even real classrooms with varied learning requirements. In combination with our approach to design for privacy first under the PrepGPT prototype, this work suggests the possibility to design AI tutors that are effective and trustworthy39; however, this possibility is only achievable provided subsequent work will rigorously test the performance of the procedures under multiple curricula as well as learner populations.

Although DE‑GRPO’s efficacy exceeds SFT with statistical significance, the absolute margin (0.02) is modest within our proxy setting and may be negligible on short quizzes; the appropriate bar for educational importance is durable gains such as delayed retention, transfer to unseen items, and multi‑session learning. We therefore treat these results as proof‑of‑concept for principled discovery under a grounded Verifier, and prioritize prospective studies with pre‑registered endpoints, larger seeds/runs, and classroom A/B tests to quantify minimally important differences and power accordingly.

The next step involves carrying out a large-scale user study with the actual students to find out if such pedagogical adaptations actually improve learning outcomes and well-being. Additionally, one will need to test the system on bigger models (say, LLaMA-3 70B) to test our theoretical Capacity Monotonicity Lemma and to gain an understanding of whether the reported boosts persist under wider and more realistic learning settings.

Conclusion

Taken together, the results outline a pragmatic path for tutoring systems that couple principled exploration with rigorous grounding, where DE-GRPO provides a mechanism to move beyond the imitation ceiling and the PrepGPT prototype demonstrates local, privacy-first delivery of adaptive explanations within a transparent, multi-agent Teacher–Student–Verifier stack and LangGraph-based orchestration tied to curriculum-aware retrieval.This integration frames adaptivity as a measurable design principle—balancing efficacy and novelty under ethical constraints—while showing that equity and privacy need not be traded for performance when tutoring runs on-device with auditable workflows and learner-sensitive affordances such as personalized handwriting notes. At the same time, evidence remains preliminary: small-scale simulations, proxy-based verification, and limited curriculum argue for cautious interpretation and for rigorous trials with real students across subjects, alongside scaling tests of the Capacity Monotonicity Lemma with larger models and richer curricula. While PrepGPT has been tested on 50+ real students from 6 different schools, the future work should focus on (1) large-scale randomized pilots to test the practicality, (2) multi-subject expansion to test generality, (3) deployment and robustness tests to validate on-device privacy, and equity, (4) theoretical and empirical scaling tests for the Capacity Monotonicity Lemma, and (5) integration and long-term follow-ups for policy and pedagogy. Each stage should also be tied to concrete metrics such as learning gains, retention, verifier accuracy, latency/energy, and subgroup equity, which will determine progression to the next stage. This prioritized plan is how the project can move from preliminary simulation and pilots toward a robust, ethical, and scalable tutoring system.

Appendix

A. Supplementary Methodological Details

A.1 Computational Framework and Models

To ensure reproducibility and performance, Our framework is built on a stable, locally-run stack. The core generative capability is provided by the Phi-3-mini-4k-instruct model, run locally via the ![]() with GPU acceleration. This provides consistent, deterministic outputs required for controlled experimentation. To compute rewards and semantic similarity, we use the

with GPU acceleration. This provides consistent, deterministic outputs required for controlled experimentation. To compute rewards and semantic similarity, we use the ![]() model from the

model from the ![]() library. This model maps text into a 384-dimensional vector space where cosine similarity corresponds to semantic closeness. For the CLIP-based diversity experiments, we use the

library. This model maps text into a 384-dimensional vector space where cosine similarity corresponds to semantic closeness. For the CLIP-based diversity experiments, we use the ![]() model, which provides embeddings in a shared visual-semantic space.

model, which provides embeddings in a shared visual-semantic space.

A.2 Instantiation of the COGNITA Agents

The abstract agents of the COGNITA game are realized as follows in our experiments: These are implemented as the core of the Self-Structuring Cognitive Agent (SSCA). The TeacherAgent implements the DE-GRPO algorithm to refine its teaching policy. Critically, its reward function is state-aware, incorporating a strategic bonus based on the novelty of an explanation relative to the Student’s current knowledge state. The StudentAgent maintains a state vector, a numerical representation of its understanding, which is updated based on the Teacher’s explanations. This vector is a direct implementation of Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. The Verifier is operationalized as an automated evaluation function, calculating efficacy. It assesses the quality of a teacher’s explanation by using the base LLM as a “student proxy” to answer a standardized quiz. The quiz score serves as the external, objective reward signal that grounds the Teacher’s learning process. In the current experimental suite, the curriculum is static. It consists of three distinct pedagogical tasks: explaining entropy, the significance of D-Day, and the intuition behind Euler’s identity. The development of a dynamic curriculum generator, which would adapt the task based on the Student’s state, remains a key direction for future work.

Mathematical specification of COGNITA. We model guided instruction as a finite‑horizon stochastic game ![]() .

.

Agents: Teacher (T), Student (S), and Verifier (V).

Discount Factor: [0,1].

Horizon: TN.

State Space: The state at time t is st=(xt,ct,ht)∈S, where:

xt ∈ Rd: The Student’s latent knowledge vector.

ct ∈ C: The current curriculum/task.

ht: The interaction history (dialogue artifacts and metadata).

Action Spaces

Teacher (AT): Actions atTAT are pedagogical interventions (natural-language explanations/analogies/counter-examples over vocabulary V).

Student (AS): Actions atSAS are quiz responses induced by the Verifier.

Verifier (AV): Actions atVAV select/synthesize probes and produce an efficacy assessment.

Transition Dynamics

The transition kernel ![]() factors as:

factors as:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Verifier Scoring

The Verifier computes two key metrics:

Efficacy: (![]() ):

): ![]() is the normalized quiz grade of a student proxy after consuming the Teacher’s intervention

is the normalized quiz grade of a student proxy after consuming the Teacher’s intervention ![]() .

.

Novelty (![]() ): This measures the semantic distance from a set of expert exemplars (

): This measures the semantic distance from a set of expert exemplars (![]() ) using an embedding

) using an embedding ![]() .

.

(6) ![]()

Rewards

Teacher Reward (![]() ) The Teacher’s state-aware reward is designed to balance efficacy and exploration (novelty):

) The Teacher’s state-aware reward is designed to balance efficacy and exploration (novelty):

(7) ![]()

The novelty weight ![]() is dynamically adjusted based on a moving-average efficacy

is dynamically adjusted based on a moving-average efficacy ![]() to implement the Discovery–Efficacy trade-off and Critical Diversity Threshold:

to implement the Discovery–Efficacy trade-off and Critical Diversity Threshold:

(8) ![]()

Link to Section 2.5: Score = ![]() corresponds to

corresponds to ![]() , with

, with ![]() .

.

Unoptimized Agents In the present work, only the Teacher (T) is optimized. Compatible reward functions for the other agents are:

- Student (

):

):  , to reflect learning gains.

, to reflect learning gains.

- Verifier (

):

):  , as the Verifier acts as an external grounding oracle.

, as the Verifier acts as an external grounding oracle.

Policies and Termination

- Teacher Policy (

):

):  is trained by DE-GRPO.

is trained by DE-GRPO.

- Student Proxy (

):

):  answers the quiz.

answers the quiz.

- Verifier (

):

):  selects probes and computes

selects probes and computes  .

.

Termination: Episodes terminate at ![]() or when

or when ![]() exceeds a predefined threshold.

exceeds a predefined threshold.

Current Instantiation

Experiments fix ![]() to one of three tasks, compute

to one of three tasks, compute ![]() via an automated quiz, and instantiate

via an automated quiz, and instantiate ![]() with cosine-based novelty. The Teacher’s selection score in evolution uses “Score = R + D,” (i.e.,

with cosine-based novelty. The Teacher’s selection score in evolution uses “Score = R + D,” (i.e., ![]() above), as implemented in

above), as implemented in ![]() .

.

A.3 Baseline Algorithm Implementation Details

The Supervised Fine-Tuning baseline is implemented via in-context learning. As described in ![]() , we perform a tournament selection over the expert dataset. In each round, we randomly sample

, we perform a tournament selection over the expert dataset. In each round, we randomly sample ![]() expert examples to form a prompt and generate a response. The policy that yields the response with the highest cosine similarity to the target concept vector is selected as the best static policy, representing the practical Imitation Ceiling,

expert examples to form a prompt and generate a response. The policy that yields the response with the highest cosine similarity to the target concept vector is selected as the best static policy, representing the practical Imitation Ceiling, ![]() .

.

The Generative Reward Policy Optimization (GRPO) framework forms the basis of our explorers. The core loop, shared across all variants, is as follows: Given a policy (a set of few-shot examples), generate a batch of ![]() candidate responses at a high temperature to encourage exploration. Score each candidate based on a specific scoring function. Identify the best-performing candidate from the batch. Identify the worst-performing example in the current policy. Replace the worst example with the best candidate, creating an improved policy for the next iteration.

candidate responses at a high temperature to encourage exploration. Score each candidate based on a specific scoring function. Identify the best-performing candidate from the batch. Identify the worst-performing example in the current policy. Replace the worst example with the best candidate, creating an improved policy for the next iteration.

B. PrepGPT Prototype: Technical Implementation Details

B.1: Overall System Architecture and Workflow

The user frontend is built using React.js for its reusable components architecture and component-based UI structure and Node.js as the runtime environment for frontend tooling and dependency management via npm. While Next.js was mentioned conceptually, the actual project implementation utilizes Vite for bundling, and not Next.js’s server-side rendering features. The frontend communicates with the backend via Axios-based REST API calls, sending and receiving structured data such as uploaded files, chat queries, summaries, and user-specific feedback. CSRF tokens are handled to ensure secure transactions.

The backend is handled by Django (Python), handles incoming requests, manages file uploads, processes converted text files, and stores user-specific data such as learning progress and styles for example from their last conversations and histories, could be stored in the sql DB. It also hosts the core AI logic using LangGraph. The “brain” of the teaching assistant operates within this Django backend, performing complex AI reasoning tasks and managing all retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) operations. This modularity enables greater user control over the AI’s behavior, allowing it to function according to specific needs rather than as an opaque, black-box system. Local LLM inference is handled using Ollama, which serves the core LLaMA 3 8B model directly on the user’s machine. This setup ensures strong privacy by avoiding external API calls and improves cost efficiency by eliminating usage-based fees. A local vector store, ChromaDB, is used to store and retrieve embeddings from curated math and science chapters. Integrated with the Django backend, ChromaDB enables fast and reliable access to relevant knowledge during inference. To overcome the factual limitations of the LLM’s training data, the system integrates external knowledge acquisition via the Google Search API and Crawl 4AI. When a user query requires up-to-date information, the system queries Google, retrieves relevant links, and uses Crawl 4AI to extract full-text content from the web. This content is then embedded and stored in a local in-memory vector store using FAISS. FAISS serves as a fast, session-specific cache of external web knowledge, allowing the system to reuse retrieved information without making repeated API calls.This also makes sure that most of the data produced as responses will be up to date and reliable

B.2: Component Design: Agent Modules and Interaction Flow

The core intelligence and explainability of our system stem is through its LangGraph-based workflow, where modular agents (nodes) interact in a dynamic, task-driven sequence.A Detailed walkthrough of the student-facing flow:

- “classify_query” Node (The Front Door): This serves as the primary entry point of the system. Its core function is to understand the user’s intent at the very beginning of the interaction. When a student asks a question or types in a prompt, this node first analyzes it to determine what kind of help is needed. Whether the query is asking for notes, problem-solving assistance, or conceptual explanations. Based on the classification, the query is appropriately tagged and routed through the system. This smart routing allows PrepGPT to act context-aware and role-specific, ensuring responses are both efficient and relevant.

- “web_search” & “crawl_content” Nodes (The Researchers): If the user asks a query in which the classifier detects a need for real-time or external information, such as “What are the tuition fees in the US?” or “What degrees are related to this concept?” The system invokes the Google Search API. Top search results are passed to “crawl_content”, which extracts full-text content using Crawl4AI for downstream processing.