Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease. In PD, the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra degenerate. There is no cure for PD, as the current treatments cannot stop the disease progression, and the treatments only focus on symptom management. GDNF and BDNF are neurotrophic factors that help in neuronal survival, and CRISPR-Cas9 is a precise gene-editing tool. It can treat degenerative disorders like PD. When used in conjunction with GDNF and BDNF, a treatment can be carried out; however, no clinical trials have been conducted in this context. This paper reviews current rvesearch and potential applications of BDNF and GDNF gene editing as a therapeutic approach for PD.PD affects more than six million people with symptoms like tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, postural complications, cognitive issues, mood swings, and sleep imbalance. They are caused by progressive dopamine depletion in the dopaminergic neurons. Current methods of treatment, like levodopa, don’t cure the disease. Instead, they suppress the symptoms and have long-term side effects.Neurotrophic factors like Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Brain-derived neurotrophic factor have shown possibilities for a cure to PD. GDNF promotes dopamine-producing neuron survival and function. BDNF also assists with the survival of neurons. But, implementing these is a problem due to short protein lifespan, immune responses, late identification of disease, and other issues.Modern gene therapy, such as genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9, has the potential to fix targeted areas. CRISPR-based techniques offer precision and long-term effects, but concerns remain regarding side effects, delivery efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness, which have hindered their clinical implementation. Thus, combining neurotrophic factor with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing as a disease-modifying strategy for Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: BDNF, PD, GDNF, dopaminergic neurons, neurotrophic factors, CRISPR, Parkinson’s, NTF, clinical trials

Introduction

More than 6 million people around the world are affected by PD. It is the second most common neurodegenerative disease. PD’s pathogenesis is still unclear, and most likely many factors contribute to the degeneration or death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, the brain region that produces dopamine necessary for motor control driven by the basal ganglia1. The primary pathology of PD is the formation of Lewy bodies, which are aggregates of alpha-synuclein proteins in the cytoplasm of neurons, disrupting their normal function. The disease has primary motor symptoms like tremors, myotonia, bradykinesia, and abnormal posture and gait. PD not only affects dopamine levels, but it also depletes neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine, which results in non-motor symptoms such as cognitive impairment, olfactory dysfunction, sleep disorder, pain, depression, anxiety, and autonomic nervous dysfunction. Blood and imaging tests can help diagnose a patient with PD, such as the Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Scan and blood tests for Alpha-Synuclein and other proteins.

Present treatments for PD focus on reducing symptoms by restoring dopamine depletion, also known as non-disease-modifying therapy. The pathophysiology of PD shows that it can be treated with dopamine (DA) replacement therapy with Levodopa (L-DOPA). Current pharmacological, surgical, and alternative PD treatments continue to use L-DOPA. L-DOPA treatment has been used for over 50 years. It reduces the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but does not slow disease progression (and does not cure the disease), and it can have adverse side effects such as dyskinesias or abnormal involuntary motor movements. As a result of these drawbacks, extensive research aims to identify disease-modifying therapies that could more directly target the etiologies, or subsequent pathophysiology, of PD1.

Neurotrophic factors (NTFs) are proteins that facilitate neurons’ development, maintenance, function, and survival. These functions make NTFs crucial for normal brain function and responding to neurodegenerative conditions. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are two types of NTFs that can influence the pathology of PD2. Gene modification techniques like CRISPR-Cas9 can improve the therapeutic potential of these neurotrophic factors, which can be used as a long-term treatment plan for PD.

Methods

This is a literature review that shows the role of BDNF and GDNF in PD. Databases include PubMed, NCBI PMC, Springer, Wiley Online Library, Nature, The Lancet, and JNS.

Inclusion criteria focused on in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies that examined BDNF and/or GDNF in PD pathophysiology or treatment. Excluded were articles not written in English or not directly related to PD. APA formatting was used for citation and referencing.

Studies from recent publications from the past 10 years were used. Both human and animal model studies were used. Neurotrophic factors and gene-editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, study design, sample size, and direct relevance to therapeutic applications were considered. Articles on recency, relevance to human vs animal models, or inclusion of gene-editing components were analyzed.

CRISPR

CRISPR is a genetic method that uses guide RNA to direct the Cas9 enzyme to a particular DNA sequence (Figure 2). Then, Cas9 makes an incision, opening the area to the addition, deletion, or alteration of genetic material1‘3.

L-dopa treatment is not the most effective; thus, gene and cell therapies might prove more effective1.

CRISPR/Cas9 is the most prominent and powerful tool due to its higher specificity and efficiency4.

Thus, CRISPR/Cas9-based gene therapy has reached the clinical trial stage for many monogenic diseases, such as sickle cell anemia, β-thalassemia, and hereditary tyrosinemia type I, and is being applied in advanced preclinical testing stages of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), hemoglobinopathies, and hereditary tyrosinemia type I1‘5.

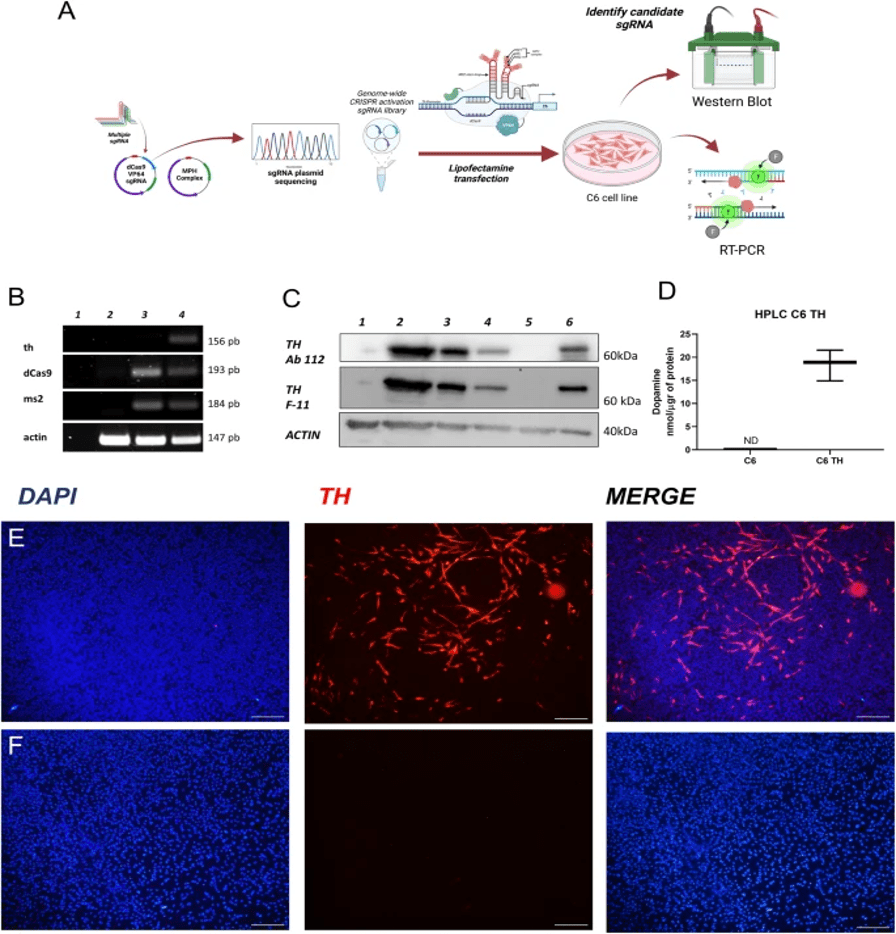

CRISPR is a cost-effective gene-editing technique. It helps treat neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease. CRISPR/Cas-based applications can edit and change gene expression. Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be treated using the SAM CRISPR gene activation system. It activates astrocytes’ endogenous tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene to produce dopamine (DA). In a rat with PD, the sgRNAs target the promoter and DA-giving astrocytes implanted into the rat’s striatum. It shows that motor function in treated rats improves. The results show that SAM-induced gene activation can produce DA and can treat PD symptoms without the side effects of traditional treatments like Levodopa.

CRISPR-Cas9 is used to cut or fix genes. It can be used to turn on helpful genes. It can turn on neurotrophic factors (NTFs) such as BDNF and GDNF (they protect brain cells). One method is the SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator) system. Instead of cutting DNA, SAM uses a dead version of Cas9 (dCas9). It can’t cut but can guide activators to a gene, boosting the activity of the gene. It produces more of the needed protein. An example is a 2024 study by Pérez et al. that showed CRISPR-SAM could increase GDNF levels in PD models. This shows better dopamine-producing neurons and less brain damage. SAM helps turn on NTF genes like BDNF and GDNF. Slowing or stopping brain cell loss in PD without changing the DNA sequence.5.

Astrocytes are glial cells that maintain homeostasis, metabolism, and response to injury and inflammation. Microglia are the brain’s immune cells. The Th protein is the required enzyme to produce DA in astrocytes. SAM (a 2nd-gen or better version of CRISPR that turns genes on) can effectively perform gene activation. SAM is needed to induce the synthesis of DA in astrocytes (by endogenous expression of th) in murine models of PD. Using SAM/CRISPR, researchers cloned single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences of the th gene in the lentiSAMv2 (LentiSAMv2 is a lentiviral vector that increases gene expression in dividing and non-dividing cells) and lentiMPH v2 plasmid vector and cell culture of CTX-TNA2 cells, a primary astrocyte non-tumorigenic line obtained from rat cerebral cortex (ATCC CRL-2006)5. Viral vector expression was successful in the astrocyte cell line (by injection/infection), referred to as AST-TH, as the stable AST-TH released DA to the culture medium.

Subsequently, the researchers explored whether this vector would show similar results in an animal model. After lesioning the substantia nigra (to create a model of PD), AST-TH cells and primary astrocytes (control group) were implanted into two different sites in the striatum. Behavioral motor tests were conducted to determine if AST-TH cell implantation was sufficient to recover PD motor symptoms. Their results indicated that AST-TH decreases the motor imbalance in the rat model of PD. Detectable DA and DA metabolism levels were increased (to a level comparable to the control group) in the striatum in the group of implanted AST-TH. Overall, SAM succeeded in inducing astrocytes to produce DA, subsequently improving motor imbalance symptoms in a rat model5.

ProSavin, a lentiviral vector-based gene therapy for continuous dopamine production for safety, has undergone clinical trial testing to evaluate its tolerability and efficacy. This was a 1/2-phase open-label trial at two locations. Fifteen PD patients were assigned to three different dose cohorts (low, mid, and high dose) and underwent bilateral injection into the striatum (see Palfi et al. 2014 for inclusion criteria and more detailed methods). Twelve months after the intervention, 54 drug-related adverse events (primarily mild and no serious adverse events) were reported. It is important to note that all patients were still taking oral dopamine medication during this study; the drug-related adverse events indicated the need for a reduction in oral medication dosing. After implementing this reduction, symptoms among patients improved. Overall, results showed a significant improvement in mean UPDRS part III motor symptoms at both, and 12 months compared to baseline.

CRISPR/Cas9 can permanently correct genetic defects in PD patients, as it can edit both embryonic and patient-derived stem cells in ex vivo1.

CRISPR/Cas9 can help in gene manipulation, such as knockouts, genome-wide screening, and disease modeling, making it superior to other gene-editing technologies. It has been successful in providing therapies for sickle cell anemia and β-thalassemia, and work is being done on treating HIV and Werner’s syndrome with CRISPR/Cas91.

In a study, researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UCB-MSCs). They can secrete soluble RAGE (sRAGE). These cells were transferred to the corpus striatum of rotenone-induced PD animal models. Behavioral, morphological analysis, and immunohistochemical tests were done to evaluate neuronal cell death and motor function recovery. It shows that treatment with sRAGE-secreting UCB-MSCs can lower neuronal cell death in the substantia nigra and corpus striatum, resulting in better motor function in PD mice. It shows that sRAGE-secreting UCB-MSCs can be used for PD1.

Another study shows reprogramming astrocytes into dopaminergic neurons (iDANs) and targeting the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Researchers use a retrovirus to show transcription factor ASCL1 (which plays a role in neurogenesis) in astrocytes. With the reprogramming medium, the astrocytes were transformed into iDANs3.

This study investigates the transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons (DANs) into non-human primates (NHPs) as a potential treatment for PD. DANs were successfully differentiated, expressing dopaminergic markers and releasing dopamine in vitro. These neurons were bilaterally transplanted into the putamen of Parkinsonian NHPs. Behavioral improvements were observed post-transplant, and MRI and PET scans were used to monitor axonal and cellular density and dopamine release. Ten months post-transplant, the grafted neurons survived without tumors, and dopamine levels increased after stimulation. These results suggest that human DANs can integrate and survive long-term in a PD model, showing promise for future therapies6.

Another study states that exosomes from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells can be used to treat PD. The intranasal administration of exosomes benefited both motor and non-motor functions in PD mice. Exosomes can cross the blood-brain barrier, lower dopaminergic neuron loss, improve the olfactory bulb neuron activity, and lower inflammation by attenuating microglia and astrocyte activation. Exomes can be a possible treatment7.

Another study states that extracellular vesicles (EVs) coming from human exfoliated deciduous teeth stem cells (SHEDs) can help with the treatment of PD. Using a rat model of PD with 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), the researchers observed EVs intranasally. Catwalk gait test results show better gait impairments with a better stand, stride length, step cycle, and duty cycle in EV-treated rats. The motor function improved with normalized tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the striatum and substantia nigra3.

Exosome-based delivery of neurotrophic factors is a non-invasive and efficient method. Special exosomes can pass the blood-brain barrier. Then, BDNF or GDNF will be delivered directly to the target. Intranasal delivery of exosomes infused with BDNF improved motor function and reduced neuronal loss in MPTP-induced PD mice7. Thus, there can be a repeatable delivery with minimal immune response.

Recent CRISPR research in PD has focused on genes associated with PD, such as SNCA and LRRK2. Mutations in SNCA (which makes alpha-synuclein) can cause the accumulation of harmful protein and lead to Lewy bodies. Researchers have used CRISPR interference to reduce the SNCA levels in lab-grown dopamine neurons. The buildup of alpha-synuclein was reduced, resulting in healthier cells8. Using CRISPR to remove or fix LRRK2 in cells and animal models helped improve mitochondrial function and lowered inflammation9.

Although CRISPR-Cas9 has the capability of treating genetic neurodegenerative diseases, its implications for PD are still being experimented with, and no human trial has been done. A challenge is where the Cas9 has unintentional changes in DNA sequences that are not targeted. These alterations could affect essential genes. Specifically, the central nervous system, as neurons are non-renewable2. To reduce this risk, other Cas9 variants like eSpCas9 and SpCas9-HF1 have been developed, which are more efficient but still are not 100% accurate.

For CRISPR’s use in PD, it must be used in dopaminergic neurons in affected regions like the substantia nigra. But the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and absence of cell-type-specific promoters make this complicated. Viral vectors like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are usually used to deliver. But some limitations include size restrictions and triggering immune responses3. It developed a tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) reporter iPSC line. It helped with live imaging and selective targeting of dopaminergic neurons. This shows that CRISPR delivery specificity can be achieved.

iPSC-derived dopaminergic neuron grafts can be used in PD therapy. In the study by Espuny6, human iPSCs were differentiated into midbrain-like DA neurons and grafted into PD mouse models. These neurons formed functional synapses. As a result, motor symptoms were improved. More recent studies examine the use of autologous iPSCs to reduce immune rejection. This shows stable and long-term survival and dopamine release in non-humans10.

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that mainly affects dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. It is the accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein, a protein that clumps up to form Lewy bodies. Usually, alpha-synuclein is broken down. After that, it is cleared by autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. But in PD, these paths are not working. As a result, alpha-synuclein accumulates. The toxic accumulation damages the cell membranes, interferes with synaptic function, and results in inflammation, resulting in neural death11.

Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to PD progression. Mitochondria in neurons with PD give less ATP and produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS). As a result, there is oxidative stress. High proportions of ROS negatively affect cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA. Pathways like cytochrome c release and caspase activation result in programmed cell death of dopaminergic neurons. PINK1 and Parkin genes keep mitochondria healthy with the help of mitophagy, which can be mutated in PD. As a result, there are mitochondrial problems11.

Microglia (immune cells of the brain) are working in PD. It releases pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Chronic activation increases toxicity, resulting in more neuron damage. Alpha-synuclein accumulations activate microglia, resulting in inflammation and neurodegeneration. Microglial overactivation can be reduced12‘9.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing can reduce neuroinflammation in PD. CRISPR-Cas9 can target inflammatory signaling genes. CRISPR could be used to treat genes that code for pro-inflammatory cytokines, microglial activation receptors, and mutations in LRRK2 or GBA (which deal with both neurodegeneration and inflammation). By editing these genes, CRISPR can slow down disease progression1‘4.

BDNF and GDNF might prevent alpha-synuclein from spreading. It stabilizes neuronal membranes and results in healthy synaptic function. They don’t break down alpha-synuclein. Instead, they improve neuronal health by reducing its toxic effects13‘14. Genetic mutations affect how neurons respond to NTFs. GBA mutations (which affect lysosomal function) usually have alpha-synuclein buildup and poor response to NTFs.

NTFs

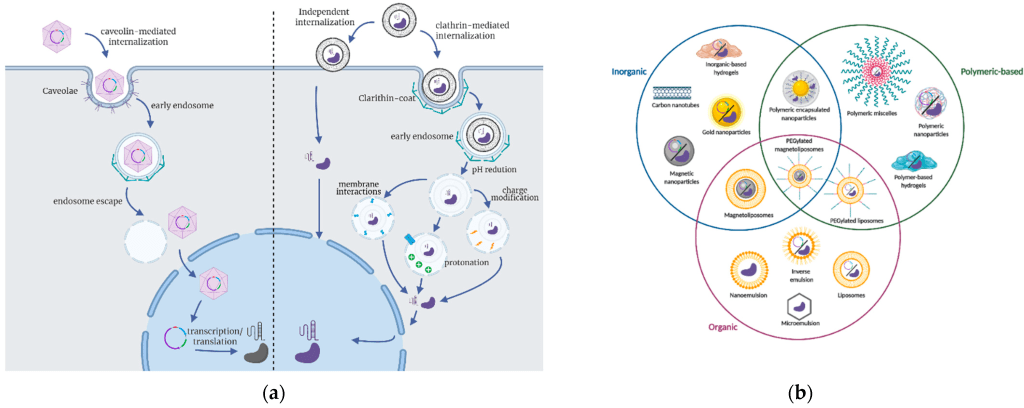

NTFs help the neurons to grow, survive, and differentiate. GDNF improves the maintenance and survival of dopaminergic neurons, especially in diseases like PD (Figure 1)15‘16‘17.

BDNF improves the neurons by strengthening them with synaptic plasticity. BDNF can increase the tolerance capacity of dopamine neurons against an acidic environment (Figure 1). An acidic environment has the potential to initiate cellular stress and apoptosis. BDNF increases the tolerance capability of dopamine neurons by increasing cell survival, mitochondrial function, and stress response systems. The amount of BDNF is downregulated in the ventral substantia nigra of PD patients13‘17.

One of the most frequently studied BDNF gene polymorphisms is G16A (Val66Met, rs6265), which involves a valine (Val) to methionine (Met) substitution. Case-control studies examining the association between the BDNF G196A (Val66Met) polymorphism and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) provide sufficient data for calculating pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). ORs represent the likelihood of an outcome occurring in one group compared to another13‘18.

One study found that the BDNF gene rs6265 polymorphism may influence cognitive impairment in PD, particularly among Caucasian populations. This suggests that variations in BDNF could play a role in cognitive decline associated with PD13‘18. However, cognition itself is not a primary motor biomarker of PD but rather serves as a staging and prognostic biomarker, aiding in subtyping and disease stratification. Although BDNF has been studied as a potential indicator of disease progression, it is not currently used as a clinical biomarker in routine practice17. More large-scale studies using standardized diagnostic criteria for cognitive impairment in PD are needed to validate the relationship between BDNF rs6265 and PD pathogenesis. These studies would help clarify at what stage of PD altered BDNF levels contribute to disease progression. Additionally, further research incorporating detailed data on the timing of genetic testing in PD patients could provide a clearer understanding of the timeline of pathophysiological changes13.

Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF)

A few studies have explored the role of GDNF in PD using in vitro cell-line models. In PD, GDNF and its receptor, GFRα1, are crucial for the survival of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons19.

Apart from BDNF and GDNF, other neurotrophic factors can also treat PD. NT-3 helps sensory and motor neurons to survive and grow. Neurturin (like GDNF) has been tested in gene therapy trials for PD. Results were not very promising. CNTF has also shown positive results in animal studies. These factors may help protect both dopamine and non-dopamine neurons. Thus, different aspects can be treated2‘20

PD is the loss of dopamine neurons in the brain, and the serotonin system is also affected. Damage to serotonin-producing neurons in the raphe nuclei causes non-motor symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and sleep problems. Thus, protection of other types of brain cells is also needed. Neurotrophic factors like CNTF or NT-3, which support both dopamine and serotonin neurons, may be required2‘20

Other studies have explored the role of GDNF and PD using in vitro cell-line models. In PD, GDNF and GFRa1 are responsible for the survival of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons21. In one study, midbrain-derived neural stem cells (mNSCs) isolated from rat embryonic mesencephalon (embryonic day 12) were treated with GDNF or in combination with GFRα1 small interfering RNA (with the GFRα1 siRNA acting as a control)21. Using reverse transcription-PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry techniques, researchers found that GDNF and the receptor GFRa1 influence the expression of nuclear receptor Nurr1 and the transcription factor Pitx3. Both are crucial for processes like differentiation, survival, and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in the brain, as well as newborn tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive cells. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is the rate-limiting enzyme in synthesizing catecholamines, a group of molecules that function similarly as both neurotransmitters and hormones. More specifically, TH catalyzes the conversion of the amino acid tyrosine to L-DOPA, the immediate precursor to dopamine (Figure 1). Therefore, TH is essential in the synthesis of dopamine and may play a role in the pathogenesis of PD.

Firstly, treatment of mNSCs with GDNF enhanced the mNSCs’ sphere diameter, reduced caspase 3 (which initiates apoptosis), and increased expression of Bcl-2 (which stops apoptosis and supports cell survival). GDNF-treated mNSCs enhanced Nurr1 and Pitx3 expression and the fraction of TH-, TH/Pitx3-, and TH/Nurr1-positive cells in culture, suggesting that an increase in TH might increase the amount of DA produced. In 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats, a model for PD-grafted GDNF-treated mNSCs into the striatum decreased apomorphine-induced rotation behavior. Apomorphine-induced rotation behavior causes an imbalance of dopamine levels in the brain, which leads to motor deficits like PD. Thirdly, GDNF-treated mNSCs resulted in increased numbers of TH/Pitx3- and TH/Nurr1-positive cells. The effect evoked by GDNF was restrained by small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of GFRα1, indicating that both GDNF and its receptor are necessary for the recovery effects seen with GDNF-treated mNSCs21. Overall, the results of this study further support the concept that GDNF signaling can induce dopamine synthesis processes, possibly through the regulation of Nurr1 and Pitx3 signaling pathways. Therefore, GDNF enhancement or delivery into the CNS may be a potential therapy for PD.

As previously mentioned, GDNF and BDNF affect PD pathology and symptoms by improving dopaminergic neuron survival and differentiation. Therefore, their therapeutic properties may be enhanced with efficient, long-lasting, and safe gene delivery methods, such as integration-deficient lentiviral vectors. Using one rat model for PD, achieved by lesioning rat striata via an injection of 6-OHDA, researchers tested the viability of lentiviral vector injection in the left striatum. The striatum contains dopamine receptors and is a brain region involved in the modulation of movement. Results showed that the disease model did not affect the overall integration frequency of lentiviral vectors. Additionally, lentiviral vector-mediated eGFP expression in the striatum of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats was observed primarily in astrocytes. Rotational behavioral tests, a proxy for motor function, were also conducted once per month for 90 minutes for 4 four months. Animals were sacrificed, and the striatum was isolated, frozen, and treated with a hGDNF ELISA kit. The levels of hGDNF in the striata of rats (receiving hGDNF vectors) were 60–250-fold higher compared to controls21. Similarly, hGDNF neuroprotection on dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, GDNF expression driven by astrocyte-specific promoters significantly increased hGDNF levels in the striata and provided substantial neuroprotection to dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc regardless of lentiviral vector integration proficiency. Furthermore, there was a behavioral recovery of hGDNF-treated rats in the amphetamine-induced rotational tests21.

Neuroprotection of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc was observed regardless of lentiviral vector integration proficiency. Furthermore, behavioral recovery was noted in hGDNF-treated rats during amphetamine-induced rotational tests21.

Another study utilized a self-complementing adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector expressing rat GDNF (AAV-GDNF) and found that long-term trophic support with GDNF delivered by AAV provided beneficial effects in rodent PD models. Specifically, researchers observed improvements in locomotion and dopamine homeostasis. However, despite these positive effects, the treatment did not prevent the continued loss of dopaminergic neurons, suggesting that while GDNF supports dopamine function, it may not be sufficient to halt neuronal degeneration14‘20‘22.

Genetically modified macrophages can be used as cellular carriers for GDNF. Macrophages are present at sites of inflammation and neurodegeneration and are good carriers23. Thus, they can transport GDNF to the substantia nigra in PD models, releasing proteins and thereby controlling the loss of dopaminergic neurons.

Overall, these studies indicate that GDNF exerts its effects through various receptors and transcription factors to support dopamine neurons and the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in both cell culture and animal models. As a result, GDNF delivery into the central nervous system (CNS) remains a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of PD. While GDNF treatment appears to improve dopamine levels and alleviate symptoms, its ability to directly address the root cause of dopaminergic neuron degeneration remains uncertain. Further research is needed to determine whether increasing GDNF levels before the onset of PD could help prevent disease progression24‘25‘26‘27.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

As previously mentioned, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is another major type of NTF widely present in the central nervous system. It plays a crucial role in promoting neuronal survival and protection. BDNF is expressed in various cerebral structures, including the striatum, and a disruption in the levels of BDNF is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including PD. More specifically, decreases in BDNF may lead to overexpression of alpha-synuclein, which leads to the formation of Lewy Bodies, and suppression of dopamine synthesis18.

This study demonstrates that BDNF enhances STAT3 phosphorylation and regulates autophagy in neurons. Autophagy is a significant cell degradation pathway that plays an essential role in maintaining the appropriate turnover of proteins and damaged organelles. STAT3 is a transcription factor that mediates extracellular signaling and may influence the PI3k/AKT/mTOR pathway, a key regulator of autophagy. This study sought to understand the role of BDNF in this STAT3-mediated pathway in a PD mouse model. BDNF increased p-TrkB, P-STAT3, PINK1, and DJ-1, promoting autophagy and inhibiting p-α-syn (Ser129), thereby enhancing cell proliferation. Results indicated a direct interaction between BDNF and STAT3, with STAT3 also interacting with PI3K. Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by Recilisib further promoted autophagy and reduced neuronal damage. BDNF protects against PD by regulating STAT3 phosphorylation and promoting autophagy in neurons28‘18.

BDNF’s short half-life and difficulty crossing the blood-brain barrier limit its effectiveness. BDNF-modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs)-derived dopaminergic (DAergic)neurons in PD treatment may address this issue. Results showed that transplanting these neurons improved motor function in PD rats, increased dopamine levels, and elevated the expression of proteins associated with neuroprotection and neuroinflammation regulation, including GFAP, Iba-1, TH, Nurr1, Pitx3, BDNF, TrkB, PI3K, and p-Akt. The treatment also reduced neural apoptosis. These effects suggest that BDNF-modified hUC-MSCs-derived DAergic-like neurons may provide neuroprotection and reduce neuroinflammation through the BDNF-TrkB-PI3K/Akt pathway, improving PD outcomes28‘18.

Overall, BDNF’s protective mechanism acts through other pathways to regulate autophagy and reduce apoptosis, thereby decreasing the degeneration of neurons in PD animal models.

Apart from concerns about delivery and specificity, reproducibility, insertional mutagenesis, and the long-term safety of CRISPR-based therapies, is still questionable. Studies have shown that patients may have pre-existing immunity to Cas9 proteins. This might lead to inflammatory responses post-injection. These challenges show that more animal model tests must be conducted before human trials1‘4.

BDNF attaches to a receptor called TrkB on neurons. This results in cell signaling that helps neurons survive, grow, and stay healthy. These signals include pathways named PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK, and PLC-γ. In PD the BDNF and TrkB levels are reduced. This can be seen specifically in the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and striatum. When TrkB is less, the survival signals are weaker. Thus, dopamine-producing neurons have a higher probability of dying, therefore worsening symptoms of PD28‘18.

GDNF first binds to a receptor called GFRα1, which then combines with RET. This activates intracellular signaling that promotes the survival of dopaminergic neurons. In PD, the reduced GDNF, GFRα1, and RET levels lower this protective signaling. GDNF can send signals through paths like the NCAM receptor. It promotes neuron growth. Another receptor, integrin β1, may change in PD. These paths can also be targets for future treatments29‘16‘30.

Clinical Trials Evaluating BDNF and GDNF

Overall, research shows that BDNF and GDNF could serve as possible treatment options for PD. However, the variation in the methods implemented may prove difficult to translate to clinical trials and use in humans. More specifically, the different methods of lentivirus delivery compared to the AAV delivery may explain some differences in results between the two studies16‘29.

One clinical trial has tested this theory. Ten patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD) underwent intraluminal catheter implantation. They were placed on a dose-escalation regimen of unilateral intraputaminal GDNF infusion for six months (3, 10, and 30 µg/day at successive 8-week intervals, followed by a 1-month wash-out period). Clinical assessments were made throughout, using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). UPDRS total and motor scores were improved by approximately 30-34% at 24 weeks compared to baseline, with sustained improvements through the wash-out period30‘31.

BDNF is an inhibitor of apoptosis and neurotoxin-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. Serum samples were compared between 47 PD patients and 23 controls, showing that PD patients have lower BDNF levels (p = 0.046). With longer disease duration and more advanced PD stages, BDNF levels were higher and correlated with greater symptom severity, including poor balance, slower gait, and reduced walking distance. Thus, low BDNF levels in early PD may lead to disease progression, and increasing BDNF levels in advanced stages may also cause problems32.

Another study found similar results; namely, serum BDNF was significantly lower in patients with PD than in patients with essential tremor (ET) and controls. ET is a movement disorder that results in action tremors, primarily in the upper limbs. It is said that ET may be neurodegenerative because of its progression over time. ET has symptomatic overlap with PD, resulting in a challenging differential diagnosis. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in serum BDNF levels between ET and control patients. Although BDNF has been studied as a potential indicator of disease progression, it is not currently used as a clinical biomarker in routine practice. More research is needed to understand the causes of high concentration with PD progression, as some think it may be due to treatment (with L-DOPA) and not related to the PD itself33.

(A) Experimental design of the SAM system.

(B) RT-PCR detection of ThmRNA in C6 and C6 TH4 cells.

(C) Western blot (TH protein expression.)

(D) HPLC measurement of dopamine release (p = 0.0007, n = 3).

(E–F) Immunofluorescence staining for TH. shows a strong signal in C6 TH4 cells

(E) and absent in C6 cells

(F). Nuclei stained with DAPI (scale bar = 20 µm).5.

GDNF and BDNF improve the survival rate and function of dopaminergic neurons. Cell lines expressing NTFs are limited because they are in vitro studies and cannot be replicated in humans. The use of animal models and CRISPR provides further insights into the potential of using this method as an effective therapy. However, more research and clinical trials need to be conducted to understand the potential therapeutic effects in humans. Overall, using BDNF and GDNF with more precise and accurate methods like CRISPR-Cas9 is a more effective treatment for PD. “Although they indicated the beginning of precise gene editing when applied therapeutically, they turned out to be expensive because of the complex design of the nuclease28‘18‘1‘4.

BDNF and GDNF improve dopaminergic neuron survival and function. BDNF deals with the survival of neurons, but GDNF deals with neuron differentiation and maintenance. GDNF can restore dopamine synthesis and reduce apoptosis. However, human clinical trials are challenging due to efficiency, safety, and uncertainty. BDNF has similar problems as it has issues crossing the blood-brain barrier16‘30‘31‘28‘18.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a major advancement in gene therapy. But the cost and other limitations have prevented clinical trials. Clinical trials for GDNF infusion have shown moderate success, while serum BDNF levels may serve as a potential biomarker for PD staging and progression34.

In the future, with further advancements, CRISPR-Cas9, BDNF, and GDNF can be used to treat PD.

A challenge for treating PD is that diagnosis usually happens after losing around 80% of their dopamine-producing neurons. It is a late stage, so treatments like BDNF, GDNF, or CRISPR gene editing may not work, as many neurons are dead. For this treatment to work, a diagnosis has to be made earlier, but finding the disease early is hard. Finding the right dose and timing is important to avoid side effects29.

CRISPR is precise, but the guide RNA that edits may bind to the wrong place in the DNA. This “off-target” editing results in unwanted changes. Sometimes these might be harmful. CRISPR has to be safer by improving guide RNA and using special versions of the Cas9 enzyme in order to reduce the number of mistakes. So, more testing needs to be done before using this method of treatment29‘34.

Many clinical trials testing neurotrophic factors for Parkinson’s disease were not successful, as these proteins are large and passing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is difficult for them. As a result, many drugs are prevented from reaching the brain. When doctors try to put them directly in the brain, the process becomes challenging. When most patients start treatment, the majority of the dopamine neurons die, so treatment becomes useless as only a few surviving cells are left.

When p75^NTR (p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75^NTR) is activated by neurotrophic factors, it causes neurons to die, unlike other receptors, which promote cell survival. Thus, treatments have less success12.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and older gene therapy methods like AAV-GDNF both have positives and negatives. CRISPR acts like a genetic scissors and is very precise while treating Parkinson’s disease. But it is still being tested so human trials are risky as doctors want to avoid unintended changes in the DNA. AAV-GDNF is already in use, but it adds extra copies of a gene without fixing the original. Thus, problems arise with controlling how much protein is made. Neurotrophic factor treatments have issues as they are hard to execute, there are late treatments due to late diagnosis, and neuron death through p75^NTR. CRISPR can solve these problems, but more research and clinical trials need to be done4‘35.

Thus, treating parkinsonism is hard. Late treatment, medicine amount, type of treatment, and side effects like activation of a receptor (p75^NTR) are some challenges. Thus, better ways to execute treatments, starting treatment earlier, and doing more research on CRISPR are some ways to solve these problems29‘34.

Several phase II clinical trials testing GDNF for Parkinson’s disease were not successful as drug distribution is limited. GDNF sometimes did not spread well throughout the affected area36. Another case is when the patients make neutralizing antibodies against GDNF. This blocked the drug’s action and lowered its benefits. Lastly, for many trials, patients with advanced PD were tested who had already lost most of their dopaminergic neurons. As a result, the treatment did not show the best results16‘30‘31

A big challenge for PD treatment is the blood-brain barrier (BBB). It works as a protection to the brain and stops many medicines from reaching the affected areas. GDNF and BDNF find it hard to cross the BBB. Thus, therapy needs to be directly given to the brain. An example is CRISPR, which can use viral vectors and be injected into target areas. Exosomes are tiny natural particles. It can cross the BBB and carry molecules to neurons. Stem cell grafts can also bypass the BBB and place new neurons directly into the brain. Immune cells called macrophages can be used to treat the damaged brain regions23‘37.

AAV viruses that are used don’t usually change the cell’s DNA and have less immune problems. But they can still cause immune reactions if their DNA stays in cells for a long time and causes damage16‘30.

Lentiviruses change the cell’s DNA. It keeps the gene working longer. Problems like cancer can happen by accidentally turning on harmful genes. Immune responses might also be triggered.

CRISPR gene editing is precise but might accidentally edit the wrong parts of DNA. The body’s immune system might react to CRISPR too. Research is still being done on CRISPR.

BDNF is responsible for neuron survival, synaptic plasticity, and increased tolerance to cellular stress, with the TrkB receptor. But it has a short half-life and has problems related to the blood-brain barrier. Thus, the effectiveness is reduced. BDNF might activate the p75^NTR receptor, which creates further problems34.

GDNF is responsible for the survival, differentiation, and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons by signaling through the GFRα1 and RET receptors. GDNF has shown positive results in preclinical models. It is improving dopamine synthesis and motor function. However, the delivery of GDNF to target brain areas is not very accurate, and mixed results in clinical trials have made it less successful. Thus, BDNF and GDNF both need to improve their delivery methods29‘16‘30

| Treatment Type | Delivery Method | Target Cells | Dose | Efficacy / Outcome | Adverse Events | Targeted Pathways |

| GDNF infusion | Intraputaminal catheter | Dopaminergic neurons | 3, 10, 30 µg/day | 30-34% UPDRS motor score improvement | Mild, mostly non-serious | Dopamine synthesis / neuron survival |

| CRISPR-SAM activation of TH gene | Lentiviral vectors | Astrocytes | Not specified | Improved motor symptoms in rat PD model | Not reported | Dopamine production via TH |

| GDNF expression via macrophages | Viral vector | Dopaminergic neurons | Not specified | Reduced dopamine loss, improved motor function | Not reported | Neuroprotection via GDNF |

| iPSC-derived dopaminergic neuron graft | Cell transplantation | Dopaminergic neurons | Cell number based | Behavioral improvement in non-human primates | No tumor formation observed | Neuronal integration & dopamine release |

| Exosome-mediated NTF delivery | Intranasal | Dopaminergic neurons | Not specified | Motor and non-motor symptom improvements | Not reported | NTF delivery and neuroprotection |

| Model Used | Method | Outcome Measured | Result | Limitations |

| Human (clinical) | GDNF infusion | UPDRS motor scores | Positive | Delivery invasiveness, dosing control |

| Rat (preclinical) | CRISPR-SAM activation of TH gene | Motor function, dopamine levels | Positive | Viral delivery, off-target effects possible |

| Rat (preclinical) | Macrophage-expressed GDNF | Dopaminergic neuron survival, motor function | Positive | Immune response, delivery efficiency |

| Non-human primate | iPSC-derived neuron graft | Behavioral improvement, dopamine release | Positive | Cell graft survival, tumor risk |

| Mouse (preclinical) | Exosome-mediated NTF delivery | Motor and non-motor symptoms | Positive | Delivery dosing, crossing BBB variability |

| Human | BDNF serum level analysis | BDNF levels, symptom correlation | Neutral/Complex | Biomarker variability, disease stage influence |

| Rat | Lentiviral GDNF vector | TH-positive neuron count, motor tests | Positive | Vector integration concerns, safety |

References

- D. Arango, A. Bittar, N. P. Esmeral, C. Ocasión, C. Muñoz-Camargo, J. C. Cruz, L. H. Reyes, N. I. Bloch. Understanding the potential of genome editing in Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 22(17), pg. 9241, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179241. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- R. A. Barker, M. Saarma, C. N. Svendsen, C. Morgan, A. Whone, M. S. Fiandaca, M. Luz, K. S. Bankiewicz, B. Fiske, L. Isaacs, A. Roach, T. Phipps, J. H. Kordower, E. L. Lane, H. J. Huttunen, A. Sullivan, G. O’Keeffe, V. Yartseva, H. Federoff. Neurotrophic factors for Parkinson’s disease: current status, progress, and remaining questions. Conclusions from a 2023 workshop. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. Vol. 14, pg. 1659-1676, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/1877718X241301041. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- C. Calatayud, G. Carola, I. Fernández-Carasa, M. Valtorta, S. Jiménez-Delgado, M. Díaz, J. Soriano-Fradera, G. Cappelletti, J. García-Sancho, Á. Raya, A. Consiglio. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated generation of a tyrosine hydroxylase reporter iPSC line for live imaging and isolation of dopaminergic neurons. Scientific Reports. Vol. 9, pg. 6811, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43080-2. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- C. Guo, X. Ma, F. Gao, Y. Guo. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. Vol. 11, pg. 1143157, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1143157. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- L. F. Narváez-Pérez, F. Paz-Bermúdez, J. A. Avalos-Fuentes et al. CRISPR/sgRNA-directed synergistic activation mediator (SAM) as a therapeutic tool for Parkinson’s disease. Gene Therapy. Vol. 31, pg. 31-44, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-023-00414-0 .4). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- I. Espuny-Camacho, K. A. Michelsen, D. Gall, D. Linaro, A. Hasche, J. Bonnefont, C. Bali, D. Orduz, A. Bilheu, A. Herpoel, N. Lambert, N. Gaspard, S. Péron, S. N. Schiffmann, M. Giugliano, A. Gaillard, P. Vanderhaeghen. Pyramidal neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells integrate efficiently into mouse brain circuits in vivo. Neuron. Vol. 77, pg. 440-456, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.011. [↩] [↩]

- M. J. Haney, N. L. Klyachko, Y. Zhao, R. Gupta, E. G. Plotnikova, Z. He, T. Patel, A. Piroyan, M. Sokolsky, A. V. Kabanov, E. V. Batrakova. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. Journal of Controlled Release. Vol. 207, pg. 18-30, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033 . [↩] [↩]

- B. Kantor, L. Tagliafierro, J. Gu, M. E. Zamora, E. Ilich, C. Grenier, Z. Y. Huang, S. Murphy, O. Chiba-Falek. Downregulation of SNCA expression by targeted editing of DNA methylation: a potential strategy for precision therapy in PD. Molecular Therapy. Vol. 26, pg. 2638-2649, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.019. [↩]

- E. H. Howlett, N. Jensen, F. Belmonte, F. Zafar, X. Hu, J. Kluss, B. Schüle, B. A. Kaufman, J. T. Greenamyre, L. H. Sanders. LRRK2 G2019S induced mitochondrial DNA damage is LRRK2 kinase dependent and inhibition restores mtDNA integrity in Parkinson’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics. Vol. 26, pg. 4340-4351, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx320. [↩] [↩]

- J. Takahashi. Preclinical evaluation of patient-derived cells shows promise for Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. Vol. 130(2), pg. 601–603, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI134031. [↩]

- J. H. Kordower, et al. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. Vol. 136(8), pg. 2419–2431, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt192. [↩] [↩]

- S. X. Bamji, M. Majdan, C. D. Pozniak, D. J. Belliveau, R. Aloyz, J. Kohn, C. G. Causing, F. D. Miller. The p75 neurotrophin receptor mediates neuronal apoptosis and is essential for naturally occurring sympathetic neuron death. Journal of Cell Biology. Vol. 140, pg. 911-923, 1998, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.140.4.911. [↩] [↩]

- M. E. Salem, et al. BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 21(3), pg. 1170, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031170. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. I. Geller, et al. Comparison of the capability of GDNF, BDNF, or both, to protect nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in rodent Parkinson’s disease models. Brain Research. Vol. 1050, pg. 118-123, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.044. [↩] [↩]

- N. K. Patel, M. Bunnage, P. Plaha, C. N. Svendsen, P. Heywood, S. S. Gill. Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease: A two-year outcome study. Annals of Neurology. Vol. 57(2), pg. 298–302, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20374. [↩]

- S. S. Gill, N. K. Patel, G. R. Hotton, K. O’Sullivan, R. McCarter, M. Bunnage, C. N. Svendsen. Direct brain infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson disease. Nature Medicine. Vol. 9(5), pg. 589–595, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm850. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- P. Scalzo, A. Kümmer, T. L. Bretas, F. Cardoso, A. L. Teixeira. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology. Vol. 257, pg. 540-545, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-5357-2. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- E. Palasz, A. Wysocka, A. Gasiorowska, M. Chalimoniuk, W. Niewiadomski, G. Niewiadomska. BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 21, pg. 1170, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031170. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- H. Kitagawa, C. Sasaki, W. R. Zhang, K. Sakai, Y. Shiro, H. Warita, Y. Mitsumoto, T. Mori, K. Abe. Induction of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor proteins in cerebral cortex and striatum after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Research. Vol. 834, pg. 190-195, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01563-2. [↩]

- L. F. H. Lin, D. H. Doherty, J. D. Lile, S. Bektesh, F. Collins. GDNF: A glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. Vol. 260(5111), pg. 1130–1132, 1993, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8493527. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ngoc B. Lu-Nguyen, Martin Broadstock, Maximilian G. Schliesser, Cynthia C. Bartholomae, Christof von Kalle, Manfred Schmidt, and Rafael J. Yáñez-Muñoz. Transgenic expression of human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor from integration-deficient lentiviral vectors is neuroprotective in a rodent model of parkinson’s disease. Human Gene Therapy. Vol25(7), pg. 631-641, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2014.00. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- N. Phielipp, C. Christine, A. Merola, J. Elder, P. Larson, W. San Sebastian, M. Fiandaca, C. Urrea, M. Wisniewski, A. van Laar, A. Kells, K. Bankiewicz. Preliminary Efficacy of Bilateral Intraputaminal Delivery of GDNF Gene Therapy (AAV2-GDNF; AB-1005) in Parkinson’s Disease: 18-Month Follow-Up From a Phase 1b Study [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2024; 39 (suppl 1). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/preliminary-efficacy-of-bilateral-intraputaminal-delivery-of-gdnf-gene-therapy-aav2-gdnf-ab-1005-in-parkinsons-disease-18-month-follow-up-from-a-phase-1b-study/. Accessed November 17, 2025. [↩]

- K. Biju, Q. Zhou, G. Li, S. Z. Imam, J. L. Roberts, W. W. Morgan, R. A. Clark, S. Li. Macrophage mediated GDNF delivery protects against dopaminergic neurodegeneration: a therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s disease. Molecular Therapy. Vol. 18, pg. 1536-1544, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2010.107. [↩] [↩]

- A. L. Whone, M. Luz, et al. Randomized trial of intermittent intraputamenal glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. Vol. 142(3), pg. 512–525, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz010. [↩]

- Parkinson’s UK. GDNF and other growth factors. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk, 2024. [↩]

- N. K. Patel, M. Bunnage, P. Plaha, C. N. Svendsen, P. Heywood, S. S. Gill. Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease: A two-year outcome study. Annals of Neurology. Vol. 57(2), pg. 298–302, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20374. [↩]

- S. S. Gill, N. K. Patel, G. R. Hotton, K. O’Sullivan, R. McCarter, M. Bunnage, C. N. Svendsen. Direct brain infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson disease. Nature Medicine. Vol. 9(5), pg. 589–595, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm850. [↩]

- M. E. Salem, et al. BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 21(3), pg. 1170, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031170. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- L. F. H. Lin, D. H. Doherty, J. D. Lile, S. Bektesh, F. Collins. GDNF: A glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. Vol. 260(5111), pg. 1130–1132, 1993, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8493527. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- N. K. Patel, M. Bunnage, P. Plaha, C. N. Svendsen, P. Heywood, S. S. Gill. Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease: A two-year outcome study. Annals of Neurology. Vol. 57(2), pg. 298–302, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20374. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. L. Whone, M. Luz, et al. Randomized trial of intermittent intraputamenal glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. Vol. 142(3), pg. 512–525, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz010. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- P. Scalzo, A. Kümmer, T. L. Bretas, F. Cardoso, A. L. Teixeira. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology. Vol. 257, pg. 540-545, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-5357-2. [↩]

- Y. Huang, W. Yun, M. Zhang, W. Luo, X. Zhou. Serum concentration and clinical significance of brain‑derived neurotrophic factor in patients with Parkinson’s disease or essential tremor. Journal of International Medical Research. Vol. 46(4), pg. 1477–1485, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060517748843. [↩]

- A. I. Geller, et al. Comparison of the capability of GDNF, BDNF, or both, to protect nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in rodent Parkinson’s disease models. Brain Research. Vol. 1050, pg. 118-123, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.044. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- B. P. Kleinstiver, V. Pattanayak, M. S. Prew, S. Q. Tsai, N. T. Nguyen, Z. Zheng, J. K. Joung. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. Vol. 529, pg. 490-495, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16526. [↩]

- AskBio Inc. First participants randomized in AskBio Phase II gene therapy trial for Parkinson’s disease. AskBio News., https://www.askbio.com/first-participants-randomized-in-askbio-phase-ii-gene-therapy-trial-for-parkinsons-disease/ , January 14, 2025 [↩]

- N. Phielipp, C. Christine, A. Merola, J. Elder, P. Larson, W. San Sebastian, M. Fiandaca, C. Urrea, M. Wisniewski, A. van Laar, A. Kells, K. Bankiewicz. Preliminary Efficacy of Bilateral Intraputaminal Delivery of GDNF Gene Therapy (AAV2-GDNF; AB-1005) in Parkinson’s Disease: 18-Month Follow-Up From a Phase 1b Study [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2024; 39 (suppl 1). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/preliminary-efficacy-of-bilateral-intraputaminal-delivery-of-gdnf-gene-therapy-aav2-gdnf-ab-1005-in-parkinsons-disease-18-month-follow-up-from-a-phase-1b-study/. Accessed November 17, 2025. [↩]