Abstract

BRCA1, also known as Breast Cancer gene 1, is a crucial tumor suppressor gene that plays a critical role in repairing damaged DNA, maintaining genomic stability, and regulating the cell cycle. Cells with BRCA1 mutations can escape normal regulatory controls, leading to unchecked cellular proliferation and the formation of malignant tumors. Mutations in the BRCA1 gene are responsible for increasing the risk of developing cancers, especially in rapidly dividing breast tissue. Among the different types of BRCA1 mutations, frameshift mutations form a substantial and highly pathogenic subset (10-26%, up to 46.7% in breast/ovarian cancer families), resulting in non-functional BRCA1 proteins and the development of breast cancer. This review specifically focuses on the role of BRCA1 frameshift mutations in breast cancer: introducing the mechanisms of mutations, summarizing the downstream effects, discussing current targeted therapies against BRCA1 mutation-associated breast cancers, and exploring future directions for improving patient outcomes. This work covers BRCA1 mutations from their tumorigenicity to their therapeutic application, providing a thorough and extensive summary about BRCA1 as a target for breast cancer therapy.

Keywords: Breast cancer, BRCA1, DNA repair, BRCA1 mutations, frameshift mutations, targeted therapies

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer found among women1 and is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths2‘3. In fact, about 30% of all female cancers are breast cancer4. While many cases of breast cancer are sporadic (caused by random genetic changes), a significant proportion is hereditary due to germline mutations (inherited mutations present in every cell from birth) found in the BRCA1 gene5. Women with a BRCA1 mutation have a greater lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, with estimates ranging from 55% to 72%, compared to the general population with the risk estimated to be 12.5%6. Understanding these mutations and their impact on breast cancer is critical for risk assessment and treatment strategies. This review primarily addresses germline BRCA1 mutations, summarizes the mechanism of BRCA1 mutations (especially frameshift mutations) and their downstream effects, discusses the current targeted therapies against BRCA1 mutation-associated breast cancers, and explores future directions for improving patient outcomes.

Methods

Peer-reviewed publications were identified through structured searches of four sources: PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), World Health Organization (https://www.who.int), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov). Searches were conducted between January 1, 1990, to December 23, 2025. The following search term combinations were used: “BRCA1”, “BRCA1 mutation”, “BRCA1 mutations and breast cancer”, “BRCA1 mutations and targeted therapy”, “BRCA1 targeted therapy in breast cancer”. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed primary research articles, human data, and published in English. A simple PRISMA-style approach was applied. In the initial database search, 293 records were identified. The articles were then screened for relevance to BRCA1 mutations, breast cancer, and targeted or mechanism-based therapies. Of these, 225 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 68 full-text articles were assessed, leading to a final set of 39 publications. For each included study, data were extracted to capture study designs, methods, important results/findings, discussions about big challenges currently faced, and future directions to improve therapeutic outcomes.

BRCA1 and BRCA1 Function

BRCA1 (Breast Cancer gene 1) is located on chromosome 17q21 and contains 24 exons7. It encodes a complex, multi-functional protein (BRCA1 protein) and plays a crucial role in maintaining genomic stability by participating in DNA repair, cell cycle control, and other cellular processes8. During DNA damage repair (specifically double-strand breaks), BRCA1 helps in the resection of DNA ends, which is important for generating single-stranded DNA overhangs to initiate homologous recombination (HR). It also helps recruit and stabilize RAD51 (a recombinase protein), facilitating strand exchange during HR9. BRCA1 is also involved in regulating cell cycle checkpoints, particularly during the G1/S (the point where the cell commits to DNA replication) and G2/M transitions (the point where the cell prepares for cell division), which are crucial for ensuring that DNA replication and cell division occur accurately. BRCA1 cooperates with p53 to induce the expression of p21, inhibiting cyclin-CDK complexes at G1/S, and also participates in G2/M checkpoint signaling10. Loss of BRCA1 function compromises this signaling pathway, allowing cyclin-CDK to remain active and enabling cells to progress into S phase despite the presence of DNA damage. This checkpoint failure leads to genomic instability and accumulation of genetic alterations, which increases the risk of developing breast cancer10‘11.

Types of BRCA1 Mutations in Breast Cancer

BRCA1 mutations in breast cancer are highly diverse. More than 1,600 mutations have been identified and are categorized into the following main types: frameshift mutations, nonsense mutations, missense mutations, splice site mutations, large genomic rearrangements, and regulatory region mutations12. Frameshift mutations are caused by insertions/deletions of nucleotide(s), producing a completely different protein or non-functional protein13. Nonsense mutations introduce a premature stop codon, halt protein synthesis early, and create a shorter, nonfunctional protein14. Missense mutations refer to a single nucleotide change that results in a different amino acid being incorporated into a protein during translation, altering the protein’s structure, function, and interactions with other molecules15. Splice site mutations disrupt the process of DNA splicing (the process of removing introns and joining exons to form mature mRNA), leading to the inclusion of introns and the exclusion of exons in the final mRNA, eventually resulting in a non-functional or different protein. Large genomic rearrangements are structural variations in DNA that involve deletions, duplications, or inversions of DNA segments which may change the gene’s sequence and produce a different or non-functional protein9. Regulatory region mutations happen in the non-coding DNA sequences that regulate gene expression, silencing or over-activating transcription and translation of a gene, leading to different levels of protein production which may result in different cellular behavior12. Although these types of mutations can happen throughout the gene, they most frequently occur in key domains such as the RING and BRCT domains, which are essential for the protein’s DNA-repair function. Among all these diverse mutations identified in breast cancer cohorts, frameshift mutations usually cause almost complete BRCA1 loss and very high cancer risk16, making them a priority for targeted therapy (Table 1).

| Mutation Type | Typical Protein Product | Expected Functional Impact | Relative Cancer Risk | Approximate Frequency |

| Frameshift | Truncated or altered | Complete loss of function | Very high (breast ~60-80%) | 30–50% |

| Nonsense | Truncated | Complete loss of function | High | 20–30% |

| Missense | Altered | Spectrum: most benign/VUS; pathogenic subset shows partial-severe loss | Variable (high for pathogenic; low/uncertain for VUS) | 5–10% pathogenic; ~30–40% of all variants are VUS |

| Splice-site | Variable | Partial or complete loss of function | Variable | 10–20% |

| Large rearrangements | Absent or severely truncated | Complete loss of function | Very high | 5–15% (higher in some populations) |

| Regulatory Region | Reduced/absent | Partial to complete loss (dose-dependent) | High | <5% germline; common somatic |

BRCA1 Frameshift Mutation in breast cancer

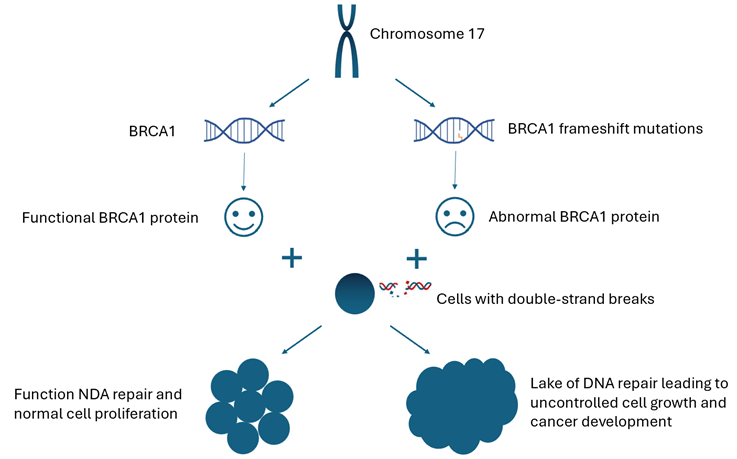

As mentioned earlier, a frameshift mutation occurs when a single nucleotide or a number of nucleotides are inserted or deleted, shifting the downstream triplet codon reading frame13. It affects all subsequent amino acids in a protein instead of just one, impacting the entire protein structure and function. This disruption may lead to 1) creating an abnormal amino acid sequence and generating a different protein or non-functional protein due to misfolding or misbinding, and 2) introducing a premature stop codon before the normal stop codon is reached and producing a truncated (shortened) protein13. When a frameshift mutation occurs in BRCA1, the resulting defective protein is unable to perform its DNA repair functions, leading to an accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage within cells, especially in rapidly dividing breast tissue, where the demand for accurate DNA repair is high. As mutations occur in critical genes regulating cell growth, division, and apoptosis, cells can escape normal regulatory controls which results in unchecked cellular proliferation and the formation of malignant tumors (Figure 1). Furthermore, the loss of BRCA1 functions affects not just DNA repair but also chromatin organization, gene expression, and the regulation of oncogenic microRNAs, amplifying its impact on cell fate17. In breast tissue, rapid estrogen-driven proliferation increases replication-associated DNA breaks, which require BRCA1-mediated repair. In addition, estrogen can also directly promote DNA damage through reactive oxygen species18. This hormonal environment (notably estrogen-driven proliferation) makes breast cells particularly vulnerable to the consequences of BRCA1 loss, resulting in a high risk of BRCA1 mutation-related breast cancers. Although ovarian cancer risk is also elevated in BRCA1 carriers, this elevated risk cannot be explained solely by hormonal factors and may involve additional non-hormonal mechanisms19.

Frameshift mutations are highly pathogenic and almost all BRCA1 frameshift mutations identified are associated with a markedly increased risk of breast cancer and worse overall survival rates20. Studies from various regions indicate a BRCA1 frameshift mutation frequency of roughly 10–26% among families with hereditary breast or breast/ovarian cancer histories, and as high as 46.7% in families with both breast and ovarian cancer21. Additionally, it has been reported that younger onset cases and families with multiple affected members show a higher frequency of BRCA1 frameshift mutations; for example, families with patients diagnosed before 40 years old may have mutation rates exceeding 40%22. Given the severity and frequency of the frameshift mutations (especially in hereditary breast cancer), frameshift mutations of BRCA1 have been the primary targets for targeted therapy.

Patient Identification and Biomarkers

Patients with BRCA1 mutations are typically identified through genetic counseling and testing guided by clinical criteria such as early-onset breast cancer (≤ 45 years and a strong family history of breast/ovarian/pancreatic/prostate cancers). Beyond germline BRCA1 mutations, some tumors exhibit homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) due to somatic mutations, epigenetic silencing, or other mechanisms, conferring a “BRCAness” phenotype that predicts PARP inhibitor sensitivity despite the presence of wild-type germline BRCA1. HRD is quantified via genomic instability scores, including loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH), telomeric allelic imbalance (TAI), and large-scale state transitions (LST), with composite HRD scores ≥ 42 often used as cutoffs in trials like OlympiAD/EMBRACA follow-ons and approvals for broader HRD-positive cohorts. Although this review focuses on pathogenic BRCA1 frameshift mutations, HRD-positive/BRCA-wild-type tumors can also benefit from PARP inhibitors23.

Targeted therapy for BRCA1 mutated breast cancer

Targeted drug therapy aims to inhibit a specific target protein/molecule that supports tumor cell growth, spread, and ability to proliferate24. Although a number of proteins, including cyclin-dependent kinases, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, and different growth factors, have emerged as potential therapeutic targets for specific breast cancer subtypes25, only BRCA1 targeted therapy is discussed in this review. Targeted therapies for BRCA1 frameshift mutations in breast cancer primarily involve PARP inhibitors, which exploit the underlying defect in homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair. These treatments take advantage of the “synthetic lethality” (a genetic interaction in which the simultaneous perturbation of two genes leads to cell or organism death, whereas viability is maintained when only one of the pair is altered) effect when BRCA1-mutated cells cannot repair DNA damage efficiently26.

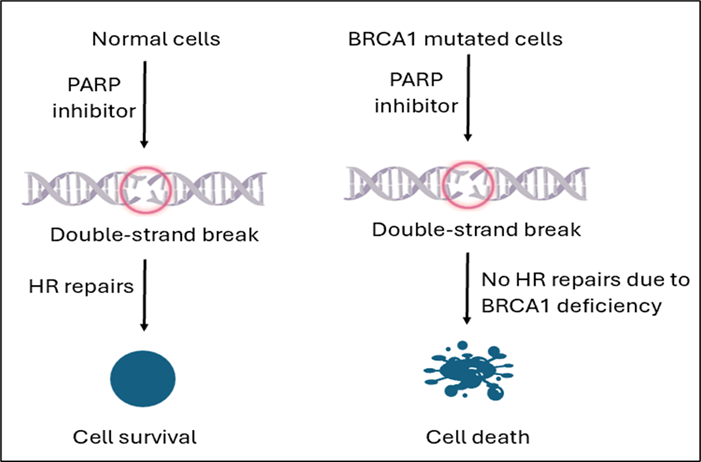

PARP inhibitors are a class of targeted therapies specifically effective for treating breast cancers with BRCA1 frameshift mutations by blocking PARP, an enzyme that plays a crucial role in repairing single-strand DNA breaks27. In BRCA1-normal cells, HR repairs replication-associated double-strand breaks when PARP is blocked; in BRCA1-deficient cells, HR is disabled, so PARP inhibition leads to unresolved DNA damage, replication fork collapse, and cell death (synthetic lethality) while sparing most normal cells28‘29 (Figure 2). Clinical research shows that PARP inhibitors significantly improve progression-free survival in BRCA1-mutated breast cancer patients compared to conventional chemotherapy and are especially effective in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which is commonly associated with BRCA1 mutations30.

TNBC accounts for 60-70% of BRCA1-associated breast cancers, likely due to the role of BRCA1 in regulating estrogen receptor-dependent differentiation, making it a key subgroup31. PARP inhibitors are particularly effective in BRCA1‑mutant TNBC with a higher response rate compared to non-TNBC breast cancers, although the precise mechanisms underlying this phenotype preference remain under investigation32.

Olaparib is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved PARP inhibitor. It inhibits PARP1 and PARP2 (key enzymes involved in the base excision repair (BER) pathway responsible for repairing single-strand DNA breaks), resulting in the accumulation of DNA damage during mitosis and leading to mitotic catastrophe and cell death25. In the phase III OlympiAD trial (NCT02000622), olaparib (300 mg, twice daily) monotherapy was found to be more effective than standard therapy in patients with BRCA1 mutations in terms of prolonging progression-free survival (7.0 months, Table 2) and reducing death (42%)33. Talazoparib is an oral PARP inhibitor approved by FDA and EMA (European Medicines Agency) as a monotherapy for the treatment of germline BRCA-mutated locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer34‘35. In an open-label phase 3 trial in patients with advanced gBRCAm breast cancer (NCT01945775), single-agent talazoparib (1mg. Once daily) demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (8.6 months, Table 2)34. Newer agents including Pamiparib, Veliparib, and Niraparib have shown increased progression-free survival and tumor response rates36.

| Trial (NCT) | Drug | Trial name | Patient population | Main reported adverse effects (PARPi arm) | Progression‑free survival (PFS) | Overall survival (OS) | Clinical significance |

| NCT02000622 | Olaparib | OlympiAD | gBRCAm, HER2‑negative breast cancer | Anemia, neutropenia, nausea, fatigue, myelosuppression, less alopecia and neuropathy | 7.0 vs 4.2 months; Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.58 [95% CI: 0.43–0.80] | 19.3 vs 17.1 months; HR= 0.90, [95% CI: 0.66–1.23] | Clinically meaningful PFS gain and numerically longer but not statistically significant effect on OS |

| NCT01945775 | Talazoparib | EMBRACA | gBRCAm, HER2‑negative breast cancer | Anemia, neutropenia, nausea, fatigue, thrombocytopenia, less alopecia | 8.6 vs. 5.6 months; Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.54 [95% CI: 0.41–0.71] | 19.3 vs 19.5 months; HR=0.85 [95% CI: 0.67–1.1] | Substantial PFS benefit but only a modest and not statistically significant effect on OS |

Although PARP inhibitors have exhibited promising outcomes in the treatment of breast cancer with BRCA1 mutation, tumors may develop resistance to PARP inhibitors via BRCA1 reversion mutations or homologous recombination repair restoration36‘37. Approximately 40–70% of patients are likely to develop resistance38 due to the following reasons: (1) BRCA1 reversion mutations that restore the reading frame and partially recover HR; (2) HR restoration via changes in other genes (exp: loss of 53BP1/SHLD1 or RAD51 upregulation); and (3) non-genetic mechanisms such as increased drug efflux39‘40‘30 (Table 3). The emerging strategy combines PARP inhibitors with IR (ionizing radiation) to increase unrepaired DNA damage in BRCA1-deficient cells, immunotherapy (such as Atezolizumab, NCT02849496) to enhance immunogenicity, or other DNA-damage response inhibitors (such as WEE1/ATR inhibitors AZD6738/ AZD1775,NCT03330847).These combinations aim to further increase efficacy against BRCA1-mutated tumors and overcome resistance38.Overall, PARP inhibitors represent a major advancement in personalized breast cancer treatment for patients with BRCA1 mutations.

| Mechanism | Brief description | Approximate frequency (qualitative) | Therapeutic implications |

| BRCA1 reversion mutations | Secondary mutations in BRCA1 that restore the open reading frame and partially rescue BRCA1 protein function and (HR). | Uncommon but detected in a minority of progressing tumors after prolonged PARPi treatment | Restored HR diminishes synthetic lethality, reducing PARPi efficacy; combinations targeting ATR/Chk1/Wee1 may be beneficial |

| HR restoration via other genes | Loss of 53BP1/SHLD1 or RAD51 upregulation to restore HR | Considered a major class of acquired resistance; accounts for a substantial subset of PARPi‑resistant BRCA1‑deficient tumors | Restored HR diminishes synthetic lethality, reducing PARPi efficacy; combinations targeting ATR/Chk1/Wee1 may be beneficial |

| Non‑genetic mechanisms: increased drug efflux | Upregulation of efflux transporters that lower intracellular PARPi concentrations without restoring HR. | Reported in preclinical models but no clinical trials currently involve efflux transporters and PAPR inhibitors | Suggests resistance can arise even without HR restoration and potential benefit from PARPi combined with efflux transporter inhibitors |

Limitations

This review is restricted to peer-reviewed publications in English, which may exclude valuable insights from other relevant sources. The dependence on reported clinical trials introduces inherent publication bias, as negative PARP inhibitor trial results may be overlooked. Furthermore, long-term outcome data beyond five years remain limited, especially for BRCA1 frameshift mutations in diverse patient groups. The narrow focus on BRCA1 frameshift mutations, not the full range of BRCA1/2 mutations or other DNA repair defects, may not apply to all types of hereditary breast cancer.

Conclusion

The BRCA1 gene is a well-known tumor suppressor gene, and germline BRCA1 mutations significantly increase the risk of developing breast cancer. PARP inhibitors were successfully developed in treating BRCA1 mutation breast cancer patients, however, tumor resistance to PARP inhibitors is emerging in clinics. For better outcomes of breast cancer patients with the germline BRCA1 mutation, it is necessary and critical to consider combination therapies (combining drugs with different therapeutic mechanisms) for treatment. With more efforts on new targeted therapy and combination therapy, more patients with BRCA1 mutations will benefit.

References

- S. Łukasiewicz, M. Czeczelewski, A. Forma, J. Baj, R. Sitarz, A. Stanisławek. Breast cancer—epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies—an updated review. Cancers. Vol. 13, pg.4287, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13174287. [↩]

- World Health Organization. Breast cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer, 2023. [↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast cancer statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cancer/statistics/index.html, 2023. [↩]

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html, 2025. [↩]

- I. Godet, D. M. Gilkes. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integrative Cancer Science and Therapeutics. Vol. 4, pg. 10, 2017, https://doi.org/10.15761/ICST.1000228. [↩]

- Z. Baretta, S. Mocellin, E. Goldin, O. I. Olopade, D. Huo. Effect of BRCA germline mutations on breast cancer prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). Vol. 95, pg. 4975, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000004975. [↩]

- H. Albertsen, R. Plaetke, L. Ballard, E. Fujimoto, J. Connolly, E. Lawrence, P. Rodriguez, M. Robertson, P. Bradley, B. Milner, D. Fuhrman, A. Marks, R. Sargent, P. Cartwright, N. Matsunami, R. White. Genetic mapping of the BRCA1 region on chromosome 17q21. American Journal of Human Genetics. Vol. 54, pg. 516–525,1994, https://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC1918118&blobtype=pdf. [↩]

- K. I. Savage, D. P. Harkin. BRCA1, a ‘complex’ protein involved in the maintenance of genomic stability. FEBS Journal. Vol.282, pg. 630-646, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.13150. [↩]

- I. Gorodetska, I. Kozeretska, A. Dubrovska. BRCA genes: The role in genome stability, cancer stemness and therapy resistance. Journal of Cancer. Vol. 10, pg. 2109–2127, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.30410. [↩] [↩]

- T. Ouchi, A.N.A. Monteiro, A. August, S.A. Aaronson, & H. Hanafusa, BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 95, pg. 2302-2306, 1998, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. [↩] [↩]

- R. I. Yarden, M. Z. Papa. BRCA1 at the crossroad of multiple cellular pathways: approaches for therapeutic interventions. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. Vol. 5, pg. 1396-1404, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0471. [↩]

- T. R. Rebbeck, N. Mitra, F. Wan, O. M. Sinilnikova, S. Healey, L. McGuffog, S. Mazoyer, G. Chenevix-Trench, D. F. Easton, A. C. Antoniou, K. L. Nathanson; the CIMBA Consortium. Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. JAMA. Vol. 313, pg. 1347–1361, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.5985. [↩] [↩]

- T.C. Nepomuceno, T. K. Foo, M. E. Richardson, J. M. O. Ranola, J. Weyandt, M. J. Varga, A. Alarcon, D. Gutierrez, A. von Wachenfeldt, D. Eriksson, R. Kim, S. Armel, E. Iversen, F. J. Couch, Å. Borg, B. Xia, M. A. Carvalho, A. N. A. Monteiro. BRCA1 frameshift variants leading to extended incorrect protein C termini. Human Genetics and Genomics Advances. Vol. 4, pg. 100240, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2024.100296. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- R.B.V. Abreu, T. T. Gomes, T. C. Nepomuceno, X. Li, M. Fuchshuber-Moraes, G. De Gregoriis, G. Suarez-Kurtz, A. N. A. Monteiro, M. A. Carvalho. Functional restoration of BRCA1 nonsense mutations by aminoglycoside-induced readthrough. Frontiers in Pharmacology. Vol. 13, pg. 1-13, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.935995. [↩]

- M. A. Fleming, J. D. Potter, C. J. Ramirez, G. K. Ostrander, E. A. Ostrander. Understanding missense mutations in the BRCA1 gene: An evolutionary approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Vol. 100, pg. 1151-1156, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0237285100. [↩]

- X. Fu, W. Tan, Q. Song, H. Pei, J. Li. BRCA1 and Breast Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. Vol. 10, pg. 1-11, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.813457. [↩]

- K. I. Savage, D. P. Harkin. BRCA1, a complex protein involved in the maintenance of genomic stability. FEBS Journal. Vol.282, pg. 630-646, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.13150. [↩]

- CE Caldon. Estrogen signaling and the DNA damage response in hormone dependent breast cancers. Frontiers in Oncology. Vol. 4, pg. 1-9, 2014, https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2014.00106. [↩]

- S. J. Ramus, S. A. Gayther. The Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to Ovarian Cancer. Molecular Oncology. Vol 3, pg. 1-13, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.001. [↩]

- A. Antoniou, P. D. P. Pharoah, S. Narod, H. A. Risch, J. E. Eyfjord, J. L. Hopper, N. Loman, H. Olsson, O. Johannsson, Å. Borg, B. Pasini, P. Radice, S. Manoukian, D. M. Eccles, N. Tang, E. Olah, H. Anton-Culver, E. Warner, J. Lubinski, J. Gronwald, … D. F. Easton. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. Vol. 72, pg. 1117–1130, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1086/375033. [↩]

- M. Jangjou, M. Alipour, R. Mofarrah, S. Alipour. Prevalence of BRCA1 gene mutations in female breast cancer patients in Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. Vol. 26, pg. 105, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-025-00743-2. [↩]

- N. Ikeda, Y. Miyoshi, K. Yoneda, M. Kinoshita, S. Noguchi. Frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Mutations Detected by Protein Truncation Test and Cumulative Risks of Breast and Ovarian Cancer among Mutation Carriers in Japanese Breast Cancer Families. International Journal of Cancer. Vol. 91, pg. 83-88, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0215(20010101)91:1<83::aid-ijc1013>3.0.co;2-5. [↩]

- A. Witz, J. Dardare, M. Betz, C. Michel, M. Husson, P. Gilson, J. Merlin, A. Harlé. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) testing landscape: clinical applications and technical validation for routine diagnostics. Biomarker Research. Vol. 13, pg. 1-21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-025-00740-y. [↩]

- T.A. Baudino. Targeted Cancer Therapy: The Next Generation of Cancer Treatment. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. Vol. 12, pg. 3-20, 2015, https://doi.org/10.2174/1570163812666150602144310. [↩]

- F. Ye, S. Dewanjee, Y. Li, N.K. Jha, Z. Chen, A. Kumar, B.T. Vishakha, S.K. Jha, H. Tang. Advancements in clinical aspects of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in breast cancer. Molecular Cancer. Vol. 22, pg. 105, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01805-y. [↩] [↩]

- S. Tang, B. Gökbağ, K.Fan, S, Shuai, Y. Huo, X. Wu, L. Cheng, L. Li. Synthetic lethal gene pairs: Experimental approaches and predictive models. Frontiers in genetics. Vol. 13, pg. 1-19, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.961611. [↩]

- S. Morganti, A. Marra, C. De Angelis, A. Toss, L. Licata, F. Giugliano, B. Taurelli Salimbeni, P. P. M. Berton Giachetti, A. Esposito, A. Giordano, J. E. Garber, G. Curigliano, F. Lynce, C. Criscitiello. PARP inhibitors for breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA Oncology. Vol. 10, pg. 658–670, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.7322. [↩]

- L. Cortesi, H.S. Rugo, C. Jackisch. An Overview of PARP Inhibitors for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Target Oncology. Vol. 16, pg. 255-282, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-021-00796-4. [↩]

- K. Pandya, A. Scher, C. Omene, S. Ganesan, S. Kumar, N. Ohri, L. Potdevin, B. Haffty, D. Toppmeyer, M. A. Geroge. Clinical efficacy of PARP inhibitors in breast. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. Vol. 200, pg 15-22, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-06940-0. [↩]

- G.R. Daly, M.M. AlRawashdeh, J. McGrath, G.P. Dowling, L. Cox, S. Naidoo, D. Vareslija, A.D.K. Hill, L. Young. PARP Inhibitors in Breast Cancer: a Short Communication. Current Oncology Reports. Vol. 26, pg. 103-113, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-023-01488-0. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- K. Won, C Spruck. Triple‑negative breast cancer therapy: Current and future perspectives (Review). International journal of oncology. Vol. 57, pg. 1245-1261, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2020.5135. [↩]

- A Jain, A. Barge, C. Parris. Combination strategies with PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated triple-negative breast cancer: overcoming resistance mechanisms. Oncogene. Vol 44, pg. 193-207, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-024-03227-6. [↩]

- M. Robson, S. A. Im, E. Senkus, B. Xu, S. M. Domchek, N. Masuda, S. Delaloge, W. Li, N. Tung, A. Armstrong, W. Wu, C. Goessl, S. Runswick, P. Conte. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. Vol. 377, pg. 523–533, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. [↩]

- J.K. Litton, H.S. Rugo, J. Ettl, S.A. Hurvitz, A. Gonçalves, K.H. Lee, L. Fehrenbacher, R. Yerushalmi, L.A. Mina, M. Martin, H. Roché, Y.H. Im, R.G.W. Quek, D. Markova, I.C. Tudor, A.L. Hannah, W. Eiermann, J.L. Blum. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. Vol. 379, pg. 753-763, 2018, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1802905#. [↩] [↩]

- G. Eskiler. Talazoparib to treat BRCA-positive breast cancer. Drugs Today. Vol. 55, pg. 459-467, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2019.55.7.3015642. [↩]

- L. Luo, K. Keyomarsi. PARP inhibitors as single agents and in combination therapy: the most promising treatment strategies in clinical trials for BRCA-mutant ovarian and triple-negative breast cancers. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. Vol. 31, pg. 607-631, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2022.2067527. [↩] [↩]

- H. Li, Z.Y. Liu, N. Wu, Y.C. Chen, Q. Cheng, J. Wang. PARP inhibitor resistance: the underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Molecular Cancer. Vol. 19, pg. 107, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01227-0. [↩]

- D. Kim, H. J. Nam. PARP inhibitors: Clinical limitations and recent attempts to overcome them. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 23, pg. 8412, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158412. [↩] [↩]

- L. M. Jackson, G. Moldovan. Mechanisms of PARP1 inhibitor resistance and their implications for cancer treatment. NAR Cancer. Vol. 4, pg. 1-18, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/narcan/zcac042. [↩] [↩]

- A. A. Turk, K. B. Wisinski. PARP inhibitors in breast cancer: Bringing synthetic lethality to the bedside. Cancer. Vol. 124, pg. 2498-2506, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31307. [↩] [↩]