Abstract

Background: Schizophrenia is a highly heterogeneous psychiatric disorder, which often makes it difficult to find treatments targeted to each patient’s unique symptom profile. Standard lines of treatment, first-generation (FGA) and second-generation (SGA) antipsychotics have shown short-term efficacy, but their long-term use is frequently associated with significant metabolic side-effects and limited relief from cognitive and negative symptoms. Given these limitations, complementary approaches targeting holistic mind-body integration like yoga-based therapy are explored for their potential to enhance cognitive function and overall quality of life.

Objective: This review evaluates the long-term efficacy of yoga-based therapy compared with traditional pharmacology to alleviate the cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

Methods: This is a literature review utilizing two randomized control trials testing yoga on the PANSS Positive, PANSS negative, and PANSS total, and SOFS scales in alleviating cognitive symptoms. Another single-blind RCT comparing yoga and usual treatment tested neuroplasticity and oxytocin levels in schizophrenia patients. Historical observational studies are used to acknowledge why traditional pharmacological treatment was utilized in the past as well as nowadays as the primary treatment.

Findings: Compared to exercise, on all scales, yoga showed better results with a statistically significant P-value of 0.001 or lower in treating cognitive symptoms. Futhermore, yoga has shown to increase levels of oxytocin in the brain, which in turn increases neuroplasticity and provides relief from cognitive symptoms.

Conclusion/Significance: The review supports that yoga has shown promising results to be an add-on therapy to alleviate cognitive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. Nonetheless, more statistically significant results are needed to establish yoga as a highly effective treatment.

Key Words: FGAs, SGAs, endocannabinoid system (ECS), THC, striatum, schizophrenia AND extra-pyramidal symptoms (EPS), Pancha Kosha model AND yoga, meditation AND yoga, serotonin, glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine pathways, dopamine D2 receptors, Risperidone and clozapine effects, affective symptoms, gynecomastia, amenorrhea, prana, nadis

Introduction

Schizophrenia remains a significant challenge in psychiatric research and clinical treatment due to its complex etiology. In the late 19th century, Emil Kraeplin introduced the term “dementia praecox”, meaning “premature dementia”, and used it to describe a chronic mental disorder that began during adolescence and led to cognitive decline1. However, in the early 20th century, Eugen Bleuler discovered that schizophrenia, meaning “split-mind” in Greek, had variable courses, and some individuals could have stable or episodic symptoms, highlighting that there were complex underpinnings to the disorder.

Globally, schizophrenia affects around 24 million individuals2 and is one of the top ten causes of disease-related burden in the age group of 15-443. Schizophrenia significantly reduces life expectancy by 10 to 28 years primarily due to the side effects of antipsychotic medications2. This makes the disorder a pressing issue to address since it not only harms personal health and quality of life, but also imposes a significant global economic burden due to healthcare costs2.

Schizophrenia is a complex disorder caused by genetic and environmental factors. There is a strong contribution from drugs of abuse such as cannabis that can cause an early onset and even make the treatment’s outcome unfavorable4. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of cannabis, increases dopamine release in the striatum (see fig.1), which exacerbates psychotic symptoms5. Additionally, drugs of abuse can potentially introduce psychosis in patients who have genetic risk factors6.

Schizophrenia is often called a spectrum disorder because it presents differently in each individual: while core symptoms like hallucinations and delusions are common, the severity, type, and combinations of symptoms can vary. Pharmacological treatment primarily targets the dopaminergic system, but has shown mixed success in balancing symptom relief with tolerability. This usually further complicates treatment and leads to relapse and hospitalization. Given these shortcomings of traditional pharmacotherapy, add-on therapies are being explored for their non-invasively healing properties, and their ability to improve overall quality of life.

To alleviate the shortcomings of traditional psychotic treatments, a number of complementary treatments have gained popularity. Recently, music therapy has shown promise, helping with symptom management, emotional regulation, cognitive function, and social engagement7. Many forms of music therapy involve rhythm and coordinated movement, which help regulate neural activity and improve motor function. These parallels of rhythmic involvement between music and movement provides an opportunity to integrate yoga—an ancient Indian practice that combines breath control, meditation, and physical postures. Unlike pharmacology, yoga targets the body holistically: specifically, the physical aspect of yoga has shown to increase neuroplasticity and oxytocin in the brain, which naturally alleviates delusions and hallucinations. This paper reviews the potential of yoga-based treatment to improve residual symptoms (negative, cognitive, and subtle positive) in schizophrenia.

Methodology and Literature Review

The longitudinal effects of current pharmacological treatments(FGAs and SGAs) were obtained via various hallmark case studies, current and historical. The case studies highlight the evolution of the use of pharmacology and the longitudinal side-effects that resulted from each one. To evaluate the efficacy of yoga therapy in schizophrenia patients, relevant literature was obtained through the following manners: an English language search of PubMed/MEDLINE , Google Scholar, and Taylor and Francis Online using key words ‘Effects of yoga on schizophrenia’, ‘Schizophrenia and psychosis’, ‘Meditation and effects on schizophrenia symptoms’, and ‘Yoga and the Pancha Kosha’. Information on manuscripts accepted and under review for publication in journals as well as pre-existing literature reviews was solicited from where such research was ongoing, particularly in India. Current studies were at least within the last 13 years, while historical studies were within 2 years of the invention of each pharmacological drug. The review is structured as such: to explain the mechanisms by which FGAs and SGAs block receptors, highlight the longitudinal side-effects and drawbacks that result from FGAs and SGAs, and present yoga as a potential complementary therapy to alleviate these long term side-effects.

Longitudinal Effects of Pharmacological Approaches

FGAs: A Brief History and Their Properties

Finding a tailored line of treatment for schizophrenia can be difficult due to its complex etiology and variable outcomes in every patient. Antipsychotic medications are used to treat and manage schizophrenic symptoms and are classified into two categories: 1st generation and 2nd generation. FGAs, also known as “typical antipsychotics” or “neuroleptics” were developed in the 1950s and revolutionized the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders8. The development of FGAs began with research on antihistamines in the 1940s. Initially tested as an anesthetic, its antipsychotic properties were discovered by Henri Laborit, a French surgeon9. Likewise, its profound effects on calming patients also drew attention. Psychiatrists Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker at Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris conducted the first clinical trials in 19529, and found that chlorpromazine significantly reduced psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia patients10.

FGAs are classified by their ability to block dopamine D2 receptors11. However, they also exhibit varying degrees of affinity for other receptors, contributing to their diverse side-effect profiles. Due to these different affinities of receptors, antipsychotic treatment with FGAs varies significantly based on potency, dosing strategies, and patient response. Some patients require high-potency drugs at low doses, while others need low-potency drugs at higher doses12. This variability in dosing leads to inter-individual variability in both efficacy and side effects, like extrapyramidal symptoms, anticholinergic effects, cardiovascular risks, and sedation, which complicates management and often forces trade‑offs between dose and tolerability. For example, low-potency FGAs (such as Chlorpromazine and Mesoridazine) often need higher dosing to achieve therapeutic effects, but lead to increased sedation and a greater incidence of anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth and constipation13. Such side effects severely impair the patient’s ability to function independently, and lead to social, emotional, and physical distress. As a result, patients may withdraw from social settings and undergo depression and worsening mental health. Consequently, non-pharmacological interventions have become imperative due to their properties of targeting the holistic mind-body connection to improve quality of life.

Second Generation Pharmacological Approaches

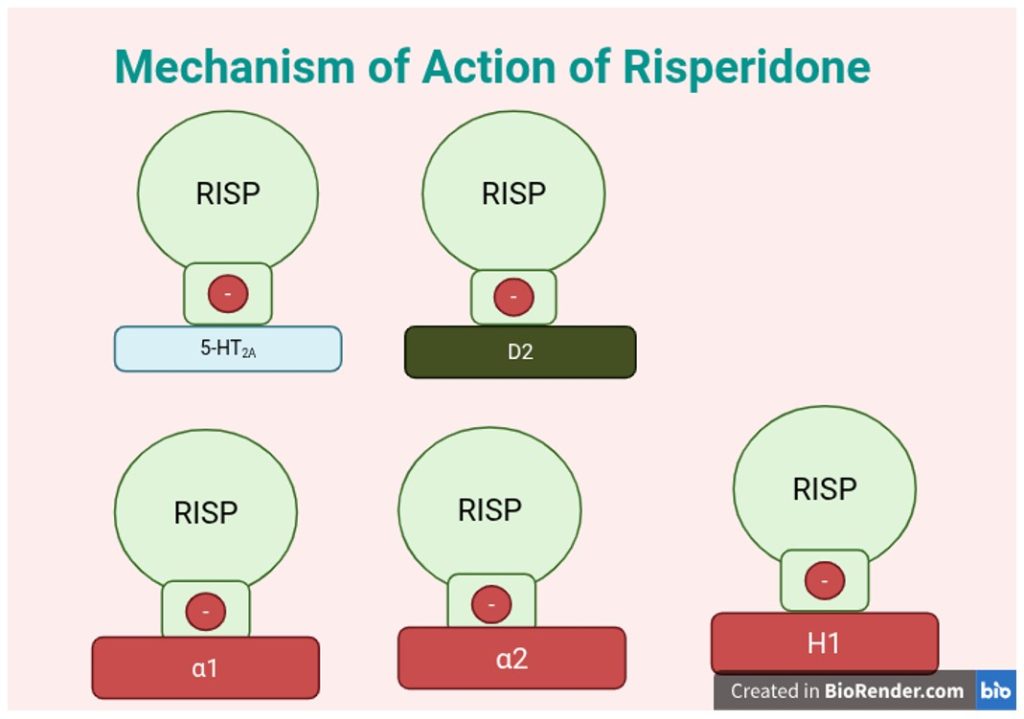

In lieu of the EPS and tardive dyskinesia (TD) seen in patients after doses of FGAs, SGAs were subsequently developed in the 1960s, seen as a better alternative. Clozapine, synthesized in 1958, underwent initial clinical evaluations in the early 1960s, and was found to block both dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5-HT2A) receptors, with limited EPS in treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients14. Many SGAs such as Risperidone (as shown in fig. 2), block both dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5-HT2A) receptors15; however, Clozapine is known to exhibit unique receptor-binding characteristics. D2 receptors are predominantly found in the mesolimbic pathway and also in the nigrostriatal (see fig. 1), mesocortical, and tuberoinfundibular pathways (see fig. 1), while 5-HT2A receptors are widely distributed in the cortex, limbic system, and basal ganglia. While most SGAs have high 5-HT2A:D2 binding ratios (relative affinity for serotonin 5-HT₂A receptors), clozapine has relatively weak D2 antagonism and stronger 5-HT2A blockade, which contributes to enhanced efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia and impact on affective symptoms.

However, despite being a quite effective antipsychotic, Clozapine and other SGAs have several limitations and risks that restrict their widespread use. Common long-term metabolic disorders for SGAs include gynecomastia in males, amenorrhea and infertility in females, an increase in LDL and triglycerides and lower levels of HDL16. Although Clozapine is effective for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, it requires regular monitoring for agranulocytosis, a condition characterized by a dangerous drop in neutrophils (a type of white blood cell), which may increase the risk of pneumonia and sepsis; Risperidone, although commonly used, can cause prolactin elevation which is known to cause erectile dysfunction and gynecomastia in males, amenorrhea and infertility in females17. These findings underscore the therapeutic plateau reached by pharmacological interventions alone and highlight the growing need for complementary strategies.

Yoga as a Holistic Treatment Approach

Compared with conventional pharmacological treatments, yoga–an ancient practice of India– presents a unique and potentially more longitudinally effective approach. Like music, yoga enhances cognitive flexibility, emotional regulation, and self-awareness. By incorporating movement into therapy, yoga can amplify the benefits of music therapy, offering a holistic approach that aligns the mind and body in managing schizophrenia symptoms more sustainably. The treatments in yoga are derived from the Pancha Kosha theory18. Derived from Sanskrit, Pancha Kosha roughly translates to “five sheaths”. The Pancha Kosha model (see fig.3), according to vedic texts, believes that all mental disorders arise from imbalances in the Manomaya Kosha(mental and emotional levels). These imbalances amplify themselves in mental illnesses called ‘Adhis’(mental/emotional disturbances in the astral sheath)18. Prompted by the perceptual growth of desires that lead to anger and jealousy, these mental diseases congeal within an individual as they begin to manifest themselves externally. The uncontrolled speed of mind, backed by these powerful emotions, can lead to agitations and violent fluctuations in the flow of Prana (life force) in the Nadis (channels of Prana as blood vessels carrying blood). Therefore, breathing exercises in yogasana are necessary to correct the flow of the Prana. Most lines of treatment include packages of Pancha Kosha with asanas and pranayama/breathing patterns to a set rhythm, but not meditation.

The empirical evidence of meditation on schizophrenia patients seems to be heterogeneous, since some forms of meditation have been associated with symptoms of psychosis post-practice in premorbidly functioning patients, while some, like mindfulness meditation, have shown to alleviate anxiety and depression19. This underscores the need for careful selection and monitoring of meditation techniques when integrating meditation into treatment plans for schizophrenia.

Evaluating the Efficacy of Yoga in Treating Symptoms

Despite the debates on the effects of meditation20, the physical components of yoga have shown to alleviate symptoms of depression, along with decreasing levels of stress and anxiety21, which makes it a promising treatment in patients with schizophrenia if performed methodically. Techniques such as pranayama have shown to reduce cortisol levels in stress-related disorders and serum insulin and lipid-profile in metabolic disorders22. Recent preliminary evidence also shows that yoga promotes neuroplasticity in neurological disorders such as depression and that it increases neurotransmitter levels like serotonin, Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), dopamine, endorphins in certain brain regions23.

Furthermore, preliminary research has proposed that meditative practices involved in yoga may increase cortical thickness24 and increase the volume in grey matter responsible for memory and cognition25. In a study conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences24, 120 schizophrenic patients on stable medication attending outpatient services were randomly assigned to three groups of approximately equal size; each of them were allocated as the following: yogasana (n=39), exercise(n=22), and waitlist(n=34). The yogasana arm received 100 of 45-minute duration sessions taught by a certified yoga instructor, and were taught breathing patterns and postures. The exercise group, lasting for the same duration and number of sessions, comprised standard physical activities, including stretching and aerobic exercises. The three groups continued to receive pharmacological therapy that was unchanged throughout the course of the trial. Before and after the assessments, a trained clinician, blind to the group allocations, rated the patients based on the following scales: (a.) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), (b.) Social and Occupational Functioning Scale (SOFS), and (c.) Extra Pyramidal Symptoms. Assessments conducted at baseline and after four months indicated that while both the yogasana and exercise groups showed improvements in negative symptoms and social functioning, the yogasana group experienced significantly greater benefits and showed statistically significant improvements with a p-value of 0.001 or <0.001. Yoga, as shown in Figure 3, has shown to be more effective than exercise, as supported by the fact that it has the lowest statistically significant p-value.

In another study by Bharat Holla26, a six-month parallel group RCT(with rater blinding) was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a yoga-based intervention. 110 patients with DSM-5 schizophrenia on stable medication were allocated either to a yoga-add-on therapy or to treatment as usual(TAU-just pharmacological treatment). Clinical assessments were conducted at baseline and at one, three, and six months. A longitudinal mixed model approach revealed a significant group-by-time interaction with the YT group showing medium effect improvements in negative symptoms (η2p = 0.06) and small effect improvements in positive symptoms (η2p = 0.012) when compared to TAU. The patients successfully learned and performed yoga practices without reporting any significant adverse effects. According to these results (as summarized in Figure 4), yoga intervention may be a viable adjuvant therapy for medication-stabilized patients with schizophrenia, especially in ameliorating negative symptoms and enhancing quality of life.

While yoga therapy could be a useful adjunct to traditional antipsychotics, the neurobiological mechanisms of the therapy have been poorly understood. Recent studies have demonstrated an increasing role of oxytocin in modulating social cognition abilities. One of the mechanisms by which yoga therapy can modulate oxytocin synthesis is through its action on the vagal nerve. Yoga is known to play a role in vagal nerve stimulation through diaphragmatic breathing (pranayama), mindful postures, and meditation, all of which trigger the dermal and subdermal pressure receptors27. In a study assessing the effect of yoga on plasma oxytocin levels, 43 schizophrenia patients were randomized to: a yoga group(n=15) and a waitlist group(n=28). Patients in the yoga group received training in a specific yoga therapy module for schizophrenia, while both groups were continued on stable antipsychotic medication. The two groups’ demographics were comparable, the sex ratio(M:F) being 12:3 and 7:5, respectively; the mean age being 28.33 in the yoga and 29.5 in the waitlist group. Similarly, the duration of illness was 68.4 and 77.2 months, respectively. The yoga therapy group showed a significant improvement in socio-occupational functioning: with plasma oxytocin levels showing a steep slope from pre-treatment to post-treatment. The waitlist group, on the other hand, showed a minimal increase in oxytocin levels(only from 3 pg/ml to 3.2 pg/ml). The results are shown summarized in Figure 5 in graph form. The increase in plasma oxytocin levels post-yoga therapy suggests a plausible biochemical pathway linking vagal stimulation with improved social cognition, which is critical in addressing schizophrenia’s social deficits. Together, these studies show that yoga emerges as a feasible adjunct. It addresses gaps left by pharmacotherapy, especially negative and cognitive symptoms, and offers biologically grounded mechanisms like oxytocin production and vagal stimulation.

Figure 6, Recreated on Excel, Randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist, Source: Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia:Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(3):227-232, Jul-Sep 2012.

Figure 6, recreated on Excel. Clinical effects of a yoga-based intervention for patients with schizophrenia – A six-month randomized controlled trial. Source: Varambally, S., Holla, B.. (2024). Schizophrenia research, 269, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2024.05.007

Figure 7. Mean Plasma Oxytocin(pg/ml) levels in yoga vs. waitlist groups, recreated on Excel. Source: Jayaram, et.al, 2013

Waitlist group, Pre-treatment represented by t=4, and post-treatment by t=10

Yoga group, Pre-treatment represented by t=4, and post-treatment by t=10

Methodology Critiques and Limitations

A combination of genetics and environmental influences are some root causes associated with schizophrenia, however, all causes responsible for the more complex underpinnings of the disorder are still yet to be discovered. Existing treatment includes mostly pharmacological treatments, which are found to exhibit off-target binding in the dopaminergic pathway, causing a wide range of cognitive side effects. To ameliorate this, yoga therapy has recently gained popularity. The present study reviewed the potential of yoga-based treatment as an add-on to pharmacology to alleviate cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Yoga therapy has shown to consistently yield positive results when compared to other forms of alternative therapy. However, it is important to point out some limitations. Although the Varambally study showed that yoga led to more statistically significant than exercise, the magnitude of the difference was small. The small but statistically significant effect (η2p= 0.012) in the second study is likely meaningful in a clinical setting when combined with other symptom improvements, but modest when viewed in isolation. Future studies must, therefore, validate yoga’s efficacy more thoroughly: perform studies that yield a larger difference between yoga and TAU. Additionally, since it is not possible to achieve blinding to treatment received in the patient group, a possible placebo effect due to an expectation of outcome from treatment can be expected.

Also, there were very few studies looking at yoga as a viable form of add-on to pharmacology in the treatment of schizophrenia. This may be due to a number of reasons.

Patient Engagement

Firstly, not all patients with schizophrenia will be able to engage in all aspects of yoga, especially the mental, which could significantly affect their outcome. In addition, if patients experience varying levels of movement-related side effects from pharmacological treatments, it might impact not only efficacy of yoga-based treatment but also affect their willingness to try yoga as an alternative therapy. Personal influences can also affect one’s willingness to try yoga. For example, western cultural influences may contribute to a lack of willingness to try such a holistic therapy that does not have a base in conventional allopathy.

Variability in Yoga Practices and Small Sample Sizes

Secondly, unlike antipsychotic medications and CBT(cognitive behavioral therapy), yoga practices vary in duration, intensity, and techniques from patient to patient, making it difficult to standardize and measure its efficacy. Furthermore the paucity of RCTs and small sample sizes of each study pose a significant limitation with a high risk of Type I i.e. an overestimation of the efficacy of yoga-based therapy.

Biological Mechanisms

Overall, biological mechanisms that might underlie the potential therapeutic effects of yoga in schizophrenia remain underexplored. Existing literature indicates that yoga may influence neuroplasticity, reduce cortisol levels, and modulate autonomic nervous system function—all of which are relevant to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Meditation Risks

Following the line of spiritual practices from yoga, there has also been emerging research on the effects of meditative practices on the brain. More current reviews post the COVID-1920 pandemic indicate that onset of psychosis is common with unguided meditative practices. Furthermore, individuals with risk factors include: those with a family history of psychosis, who practice of transcendental and concentrative meditation in social isolation or at odd times i.e. early morning or late night. Fortunately, meditation-induced psychosis often responds well to treatment and cessation of the implicated meditation practice. As effective as alternative therapies may be, it is important to tread with caution with unguided meditative practices when it comes to managing psychotic symptoms.

Future Directions and Implications

Advancing the treatment of schizophrenia requires a multi-dimensional approach that moves beyond sole reliance on pharmacological interventions. Future research should prioritize the development of personalized treatment strategies, integrating genetic, neurobiological, and psychosocial data to tailor therapies to individual patients. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of adjunctive therapies such as yoga, with a focus on standardized protocols and outcome measures. Further exploration of mind-body interventions may illuminate underlying neuroplastic mechanisms that support cognitive and functional recovery. Additionally, the design of next-generation antipsychotics should aim to minimize off-target receptor binding to reduce metabolic and motor side effects.

Conclusion

The review reveals that there is a dead end to using antipsychotics in the long run due to their off-target binding profiles, which gives rise to numerous cognitive and metabolic defects in the long run. This is especially true in SGAs, which have varying degrees of affinity that block more than the D2 receptor and cause a wide profile of movement-related and metabolic side-effects. In turn, many of them lead to discontinuation of treatment among patients. Yoga therapy, rooted in the Pancha Kosha model of ancient Indian philosophy, addresses mental illness at the Manomaya Kosha level (encompassing emotional and cognitive disturbances) providing a complementary pathway for therapeutic intervention. Yoga can be used to alleviate cognitive side-effects that are associated with schizophrenia, making treatment more successful for patients. Studies incorporating randomized controlled trials support yoga’s effectiveness over both standard exercise and treatment-as-usual in improving negative symptoms and social cognition. Moreover, yoga appears to mitigate some of the cognitive side-effects associated with antipsychotic use, making it a viable strategy for long-term management and relapse prevention in schizophrenia.

References

- Engstrom, E. J., Burgmair, W., & Weber, M. M. (2002). Emil Kraepelin’s “Self-Assessment”: clinical autography in historical context. History of Psychiatry, 13(49), 089-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957154×0201304905 [↩]

- Magas, I., Norman, C., & Vasan, A. (2025). Premature Mortality and Health Inequality among Adult New Yorkers with Serious Mental Illness. Journal of Urban Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-024-00953-w [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Rössler, W., Joachim Salize, H., van Os, J., & Riecher-Rössler, A. (2005). Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(4), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.009 [↩]

- Patel, S. J., Khan, S., M, S., & Hamid, P. (2020). The Association Between Cannabis Use and Schizophrenia: Causative or Curative? A Systematic Review. Cureus, 12(7). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9309 [↩]

- Renard, J., Szkudlarek, H. J., Kramar, C. P., Jobson, C. E. L., Moura, K., Rushlow, W. J., & Laviolette, S. R. (2017). Adolescent THC Exposure Causes Enduring Prefrontal Cortical Disruption of GABAergic Inhibition and Dysregulation of Sub-Cortical Dopamine Function. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11420. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11645-8 [↩]

- Wainberg, M., Jacobs, G. R., di Forti, M., & Tripathy, S. J. (2021). Cannabis, schizophrenia genetic risk, and psychotic experiences: a cross-sectional study of 109,308 participants from the UK Biobank. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01330-w [↩]

- Geretsegger, M., Mössler, K. A., Bieleninik, Ł., Chen, X.-J., Heldal, T. O., & Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004025.pub4 [↩]

- Ferrero, V. (1975). CHLORPROMAZINE IN PSYCHIATRY, A STUDY OF THERAPEUTIC INNOVATION. Psychiatric Annals, 5(12), 87–88. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19751201-15 [↩]

- Etain, B., & Roubaud, L. (2002). Jean Delay, M.D., 1907–1987. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1489–1489. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1489 [↩] [↩]

- Delay, J., Deniker, P., & Harl, J. M. (1952). Utilisation en thérapeutique psychiatrique d’une phénothiazine d’action centrale élective (4560 RP) [Therapeutic use in psychiatry of phenothiazine of central elective action (4560 RP)]. Annales medico-psychologiques, 110(2 1), 112–117. [↩]

- Abou-Setta, A. M., Mousavi, S. S., Spooner, C., Schouten, J. R., Pasichnyk, D., Armijo-Olivo, S., Beaith, A., Seida, J. C., Dursun, S., Newton, A. S., & Hartling, L. (2012, August 1). Table O-1, First-generation antipsychotics included in the CER. Www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK107247/table/appo.t1/ [↩]

- Chokhawala, K., Stevens, L., & Chokhawala, A. (2023). Antipsychotic medications. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519503/ [↩]

- Tardy, M., Le Berre, M., Camos-Ducamp, S., & Boyer, L. (2025). Mindfulness interventions in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 12173738. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12173738/ [↩]

- Anderman, B., & Griffith, R. W. (1977). Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: A situation report up to August 1976. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 11(3), 199–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00606410 [↩]

- Buoli, M., Kahn, R. S., Serati, M., Altamura, A. C., & Cahn, W. (2016). Haloperidol versus second-generation antipsychotics in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 31(4), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2542 [↩]

- Grant, A. (2024, September 26). FDA approves drug with new mechanism of action for treatment of Schizophrenia. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-drug-new-mechanism-action-treatment-schizophrenia [↩]

- Gautam, S., Jain, S., & Bhargava, M. (2006). Weight gain with olanzapine: Drug, gender or age? Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.31617 [↩]

- Raina, M. K. (2016). THE LEVELS OF HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS AND CREATIVE FUNCTIONING: INSIGHTS FROM THE THEORY OF PANCHA KOSHA (FIVE SHEATHS OF CONSCIOUSNESS [↩] [↩]

- Mohandas, E. (2008). Neurobiology of Spirituality. Mens Sana Monographs, 6(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.33001 [↩]

- Goud, S. S. (2022). Meditation: A Double-Edged Sword—A Case Report of Psychosis Associated with Excessive Unguided Meditation. Case Reports in Psychiatry, 2022, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2661824 [↩] [↩]

- Bridges, L., & Sharma, M. (2017). The Efficacy of Yoga as a Form of Treatment for Depression. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4), 1017–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217715927 [↩]

- Varambally, S., Venkatasubramanian, G., Govindaraj, R., Shivakumar, V., Mullapudi, T., Christopher, R., Debnath, M., Philip, M., Bharath, R. D., & Gangadhar, B. (2019). Yoga and schizophrenia—a comprehensive assessment of neuroplasticity: Protocol for a single blind randomized controlled study of yoga in schizophrenia. Medicine, 98(43), e17399. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017399 [↩]

- Sengupta, P. (2012). Health Impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(7), 444. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3415184/ [↩]

- Varambally, S., Thirthalli, J., Venkatasubramanian, G., Subbakrishna, D., Gangadhar, B., Jagannathan, A., Kumar, S., Muralidhar, D., & Nagendra, H. (2012). Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia: Randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(3), 227. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.102414 [↩] [↩]

- Kuo, S. S., & Pogue-Geile, M. F. (2019). Variation in fourteen brain structure volumes in schizophrenia: A comprehensive meta-analysis of 246 studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 98, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.030 [↩]

- Holla, B., Venkatasubramanian, G., Mullapudi, T., Raj, P., Shivakumar, V., Christopher, R., Debnath, M., Philip, M., Bharath, R. D., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2024). Clinical effects of a yoga-based intervention for patients with schizophrenia – A six-month randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia research, 269, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2024.05.007 [↩]

- Kuntsevich, V., Bushell, W. C., & Theise, N. D. (2010). Mechanisms of yogic practices in health, aging, and disease. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 77(5), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/msj.20205 [↩]