Abstract

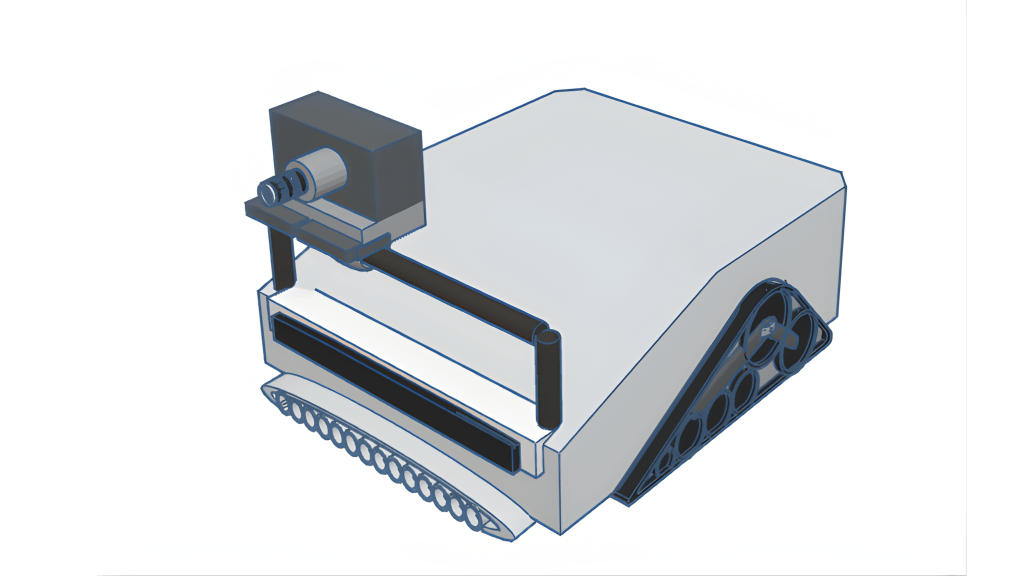

This paper presents a conceptual design and theoretical control systems modeling framework for an autonomous beach-cleaning robot, engineered to operate in the challenging and dynamic coastal environment. The proposed robot architecture integrates a solar-powered energy system, a comprehensive suite of sensors (multi-spectral, LiDAR, GPS, IMU, ultrasonic), and multiple actuators (tracks, adaptive suspension, debris collection mechanisms) coordinated by a central microcontroller. A modular state- space model is developed to conceptually capture the dynamics and interactions of all major subsystems, expressed in the canonical form ![]() , where the state vector encapsulates battery status, robot kinematics, sensor readings, and actuator states. This modeling approach enables the systematic design of feedback controllers and supports stability analysis based on established Lyapunov theory principles, as detailed from classical and modern control literature. The architecture includes a proposed real-time IoT dashboard for remote supervision and command. By leveraging a rigorous theoretical control systems approach, this work lays a foundation for robust, adaptive, and extensible robotic solutions to environmental cleanup, providing a framework for future research and development toward practical implementation, such as cooperative multi-robot operation and advanced control strategies.

, where the state vector encapsulates battery status, robot kinematics, sensor readings, and actuator states. This modeling approach enables the systematic design of feedback controllers and supports stability analysis based on established Lyapunov theory principles, as detailed from classical and modern control literature. The architecture includes a proposed real-time IoT dashboard for remote supervision and command. By leveraging a rigorous theoretical control systems approach, this work lays a foundation for robust, adaptive, and extensible robotic solutions to environmental cleanup, providing a framework for future research and development toward practical implementation, such as cooperative multi-robot operation and advanced control strategies.

Introduction

Marine plastic pollution has become one of the most pressing environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. A substantial fraction of this plastic waste accumulates on coastlines, where it threatens ecosystems, public health, and local economies dependent on tourism and fisheries. Manual beach cleanups, while effective at small scales, are labor-intensive, episodic, and cannot keep pace with the continuous influx of debris. Large-scale mechanical cleanups, on the other hand, risk disrupting fragile dune ecosystems and are often economically unsustainable.

In this paper we focus specifically on the problem of plastic debris removal on sandy beaches. By narrowing the scope to this class of waste, we address both the environmental urgency of micro- and macro-plastic pollution and the technical challenges that arise from operating in deformable, unpredictable terrains. While our methods and insights may be extendable to general-purpose cleaning in other outdoor or semi-structured environments, our primary motivation is the automated, sustainable removal of plastics such as bottles, packaging, and fishing gear fragments from beaches.

Defining the scope early serves two purposes. First, it clarifies that the proposed robot is not intended for sweeping all types of debris (e.g., organic seaweed, driftwood, or general litter in urban contexts), but rather prioritizes lightweight plastics that are harmful to marine life and often overlooked by conventional cleanup approaches. Second, it emphasizes that the environmental conditions of sandy beaches — uneven surfaces, variable compaction, and dynamic obstacles — fundamentally shape the robot’s dynamics and control design. These conditions motivate the nonlinear modeling and adaptive control methods developed later in this paper.

By situating our contribution within the concrete challenge of plastic debris removal, we not only respond to a critical ecological and societal need, but also provide a well-defined domain in which to test and validate advances in nonlinear control, environmental robotics, and sustainability-driven design. The automation of environmental cleanup tasks, such as beach cleaning, presents unique challenges in robotics and control systems engineering. The dynamic, unstructured nature of the beach environment, characterized by variable terrain, unpredictable obstacles, and heterogeneous debris, necessitates a robust, modular, and adaptive control architecture. This work presents the design and modeling of an autonomous beach-cleaning robot, emphasizing a systematic control systems approach.

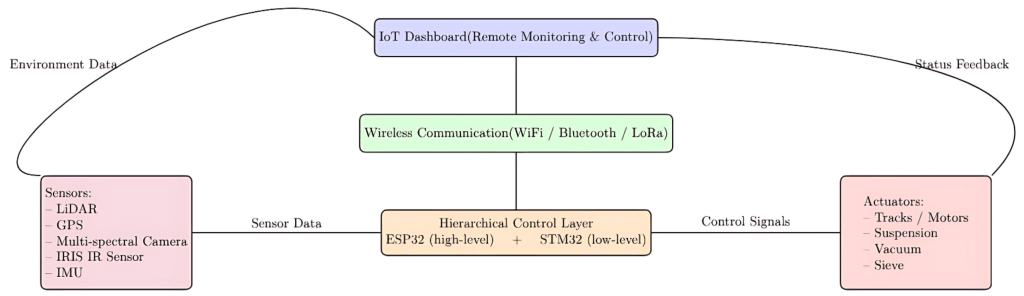

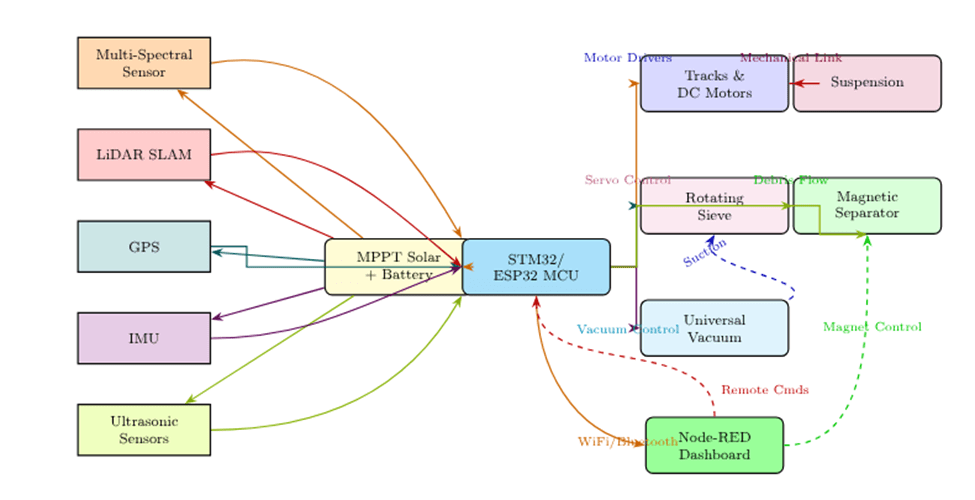

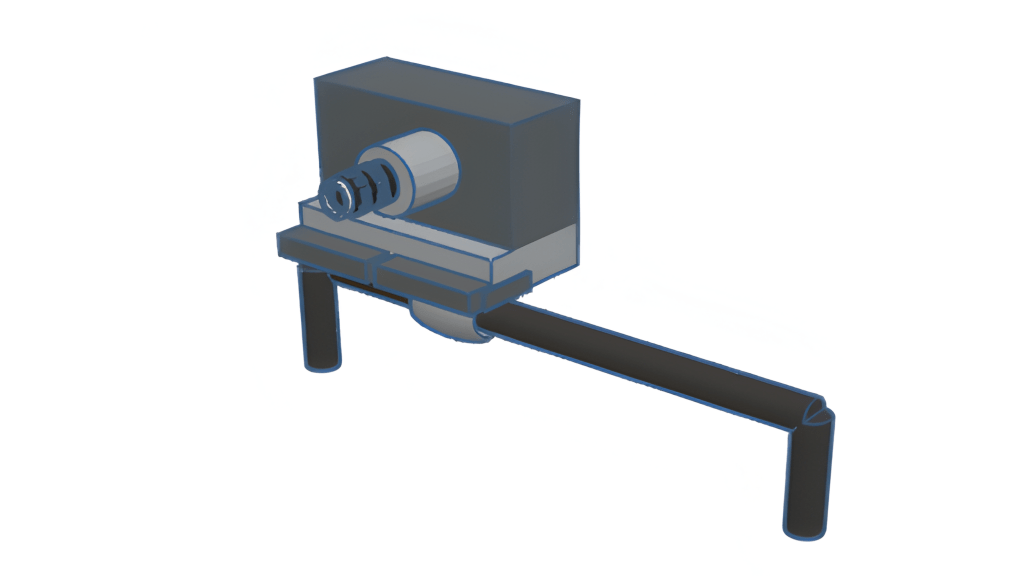

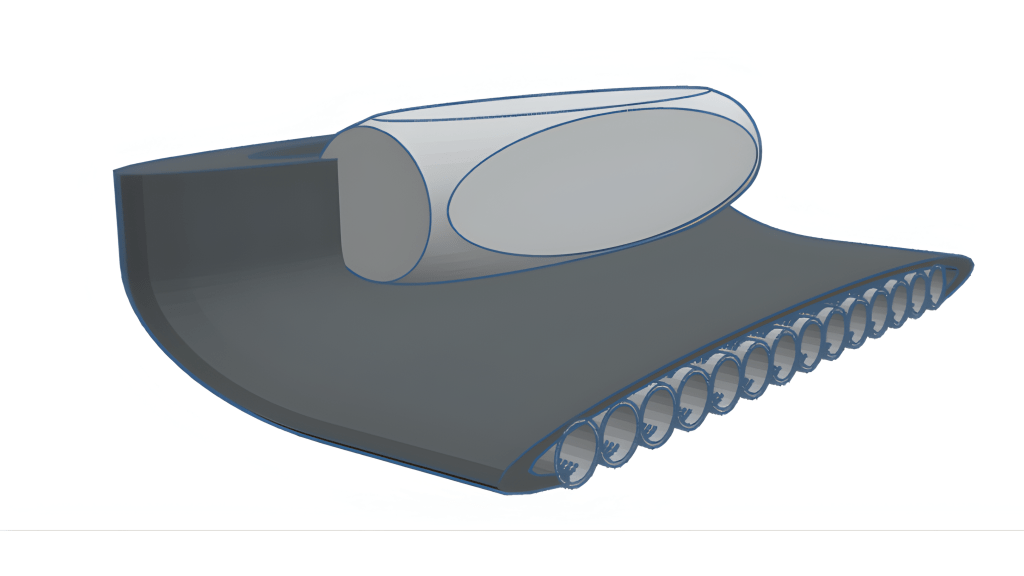

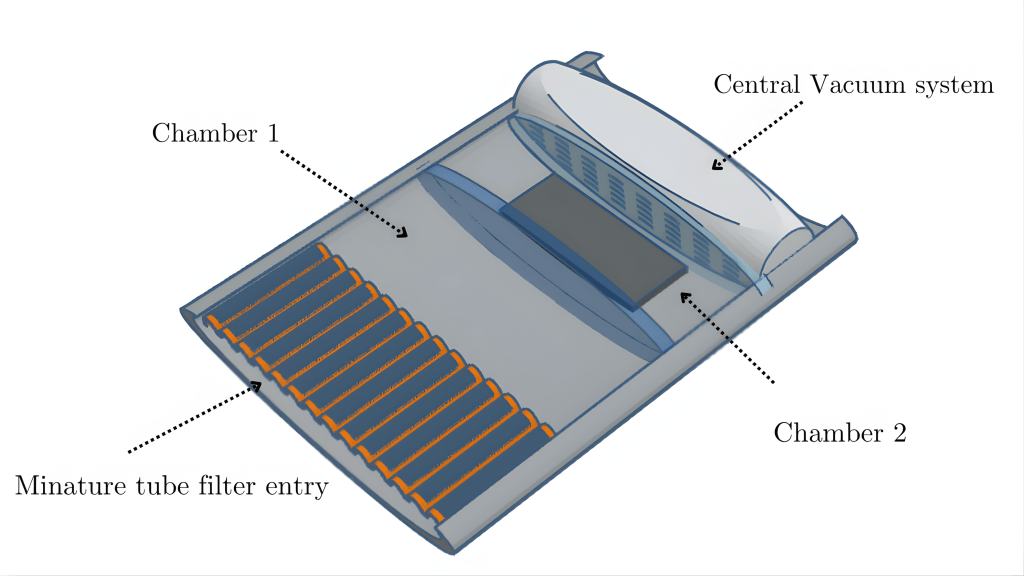

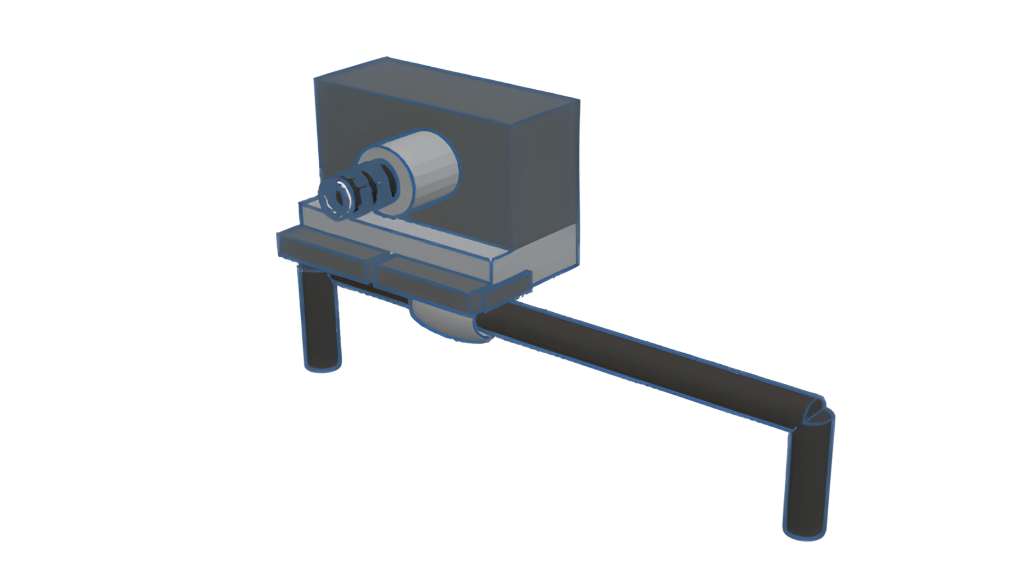

At the core of the robot’s architecture is a hierarchical control system integrating multiple sensing, actuation, and computation subsystems. The robot is powered by a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) solar array with battery storage, providing energy to a suite of sensors (multi-spectral, LiDAR, GPS, IMU, ultrasonic) and actuators (caterpillar tracks, adaptive suspension, rotating sieve, vacuum, magnetic separator). The central microcontroller (STM32/ESP32) acts as the supervisory controller, executing sensor fusion, motion planning, and actuator coordination.

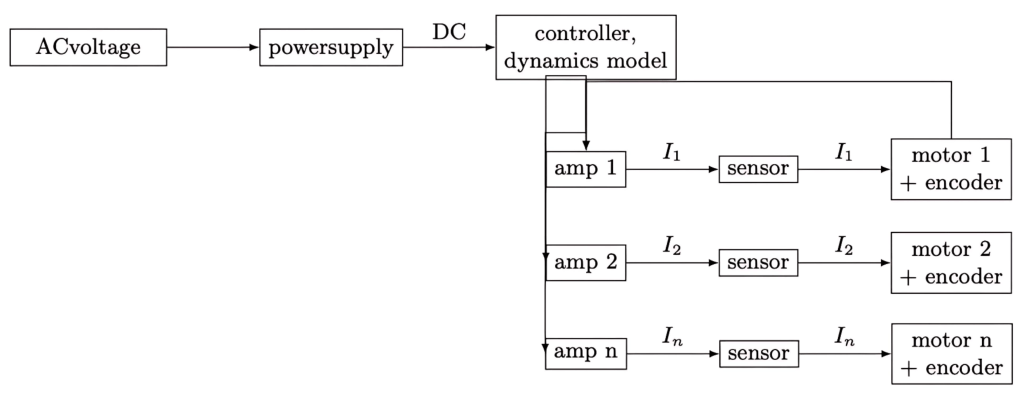

Figure 1 illustrates the robot control system structure showing the current flow.

The overall system can be mathematically represented in the standard state-space form:

(1) ![]()

(2) ![]()

where ![]() is the state vector encompassing battery state-of-charge, robot kinematics, sensor states, and actuator positions;

is the state vector encompassing battery state-of-charge, robot kinematics, sensor states, and actuator positions;![]() is the input vector including remote commands, environmental disturbances, and actuator setpoints; and

is the input vector including remote commands, environmental disturbances, and actuator setpoints; and![]() is the output vector representing measurable quantities such as robot position, debris detection, and system status.

is the output vector representing measurable quantities such as robot position, debris detection, and system status.

The ![]() matrix encodes the internal dynamics of each subsystem and their interactions, while

matrix encodes the internal dynamics of each subsystem and their interactions, while ![]() maps control inputs to state changes. For example, the motion subsystem is governed by:

maps control inputs to state changes. For example, the motion subsystem is governed by:

(3) ![]()

where ![]() is the track velocity and

is the track velocity and ![]() is the motor control input. The robot’s position, derived from sensor fusion (LiDAR/GPS/IMU), evolves as:

is the motor control input. The robot’s position, derived from sensor fusion (LiDAR/GPS/IMU), evolves as:

(4) ![]()

with ![]() representing orientation.

representing orientation.

Hierarchical Control System Architecture

To clarify organization of the hierarchical control system referenced in the introduction, we present Figure 3, which illustrates interaction between the STM32/ESP32 microcontrollers, sensing modules, actuation subsystems, and the IoT dashboard.

Literature Review

1. In Comprehensive Review of Solar Remote Operated Beach Cleaning Robot by A. Kumar, P. Sharma, and R. Singh, the authors construct a beach-cleaning robot with optimal utilities suited for efficiency and independence, such as solar panels, lithium-ion battery, conceptual description of a camera utilized for navigation, and a conveyor belt system1. Our theoretical design aims to achieve the same task as this design, but our conceptual design of a vacuum-filtration system boasts an ideally more efficient path for debris to be collected, due to an increased force by the vacuum. In addition, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates a heightened awareness of navigation by concept.

2. In Remote Controlled Road Cleaning Vehicle by R. Patel and S. Desaithe, the authors provide a hardware component list essential for a remote controlled road cleaning vehicle2. Specific components listed are a DC power supply (similar to our proposal of a lithium-ion battery usage), microcontroller for essential machine interface and control, and a brush mechanism for collecting trash. Our paper proposes a robot design that proposes a conceptual design of a vacuum-filtration system, which boasts an ideally more efficient path for debris to be collected, due to an increased force by the vacuum compared to the brush mechanism. In addition, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates the possibility for operating and navigating with independence, instead of using remote control.

3. In Autonomous Robotic Street Sweeping: Initial Attempt for Curbside Sweeping by M. Bergerman and S. Singh, the authors provide an analysis of an engineered autonomous street sweeping robot, utilizing an IMU & GPS autonomous navigation along with a fisheye dual-camera setup to target trash according to the image renders3. Our design offers similar utilizations, but instead of an IMU & GPS system, we utilize a perimeter rendering LiDAR system along with an AEGIS machine-learning assisted camera to accurately differentiate obstacles and trash by concept. Our setting of automation involves an ocean shore, which holds more environmental obstacles than this experiment’s flat, curbside setting, requiring the specific technology in this study to automate these obstacles.

4. In Cleaning Robots in Public Spaces: A Survey and Proposal for Benchmarking Based on Stakeholders Interviews by A. Papadopoulos and L. Marconi, the authors provide an analysis of a combination of interviews of automated robot utilization in public spaces, specifying their performance, capabilities, and ideal requirements for implementation4. This connects to our justifiable decision of utilizing our Lidar + SLAM system being a necessity towards self navigation and cognition.

5. In Modular Robot Used as a Beach Cleaner by G. Muscato and M. Prestifilippo, the authors demonstrate simulations of camera image processing, avoidance simulation, and a theoretical claw-like trash collecting mechanism within a similar ocean shore cleaning robot5. However, our proposal of a theoretical vacuum filtration system considers the possible increase in efficiency of waste collection compared to this paper’s claw design.

6. In OATCR: Outdoor Autonomous Trash-Collecting Robot Design Using YOLOv4-Tiny by H. Chen, L and Zhang, J, the authors propose an outdoor autonomous trash-cleaning robot design, with details of control system structure, robot structure, visual waste detection analysis with mathematical interpretations along with simulations using TACO (Trash annotations in context) assist6. This paper displays an application using a machine learning database to identify trash in a robot’s surroundings, which is a similar approach to our utilization of AEGIS camera waste identification.

7. In Waste Management by a Robot: A Smart and Autonomous Technique by R. Gupta and N. Sharma, the author provides a control system structure for a remote controlled road cleaning vehicle, and even a prototype physical design of the robot7. Specific components listed are microcontrollers (arduino) for essential machine interface and control, and a combination of motor drivers and servo motors for a robotic arm for dynamic trash collection. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. The primary focus of unique innovation is the design of a vacuum-filtration system, which boasts an ideally more efficient path for debris to be collected, due to an increased force by the vacuum. In addition, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates the possibility for operating and navigating with independence, instead of using remote control.

8. In Beach Sand Rover: Autonomous Wireless Beach Cleaning Rover by S. Iyer and A. Nair, the authors provide a component list, experimental proposal of infrared sensors combined with a GPS system for independent navigation, and physical models for a claw utilizing road cleaning vehicle8. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. The primary focus of unique innovation is the design of a vacuum-filtration system, which boasts an ideally more efficient path for debris to be collected, due to an increased force by the vacuum. In addition, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles than GPS + infrared sensors.

9. In Autonomous Trash Collecting Robot by K. Lee and A. Patel, the authors provide a component list, experimental proposal of infrared sensors combined with ultrasonic sensors for surrounding awareness, and physical models for a suction vacuum trash collecting system9. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. The primary focus of unique innovation is the design of a vacuum-filtration system, which boasts an ideally strong and selective accuracy for a variety of debris to be collected, due to the addition of filtration by the vacuum. In addition, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates the possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles than ultrasonic + infrared sensors.

10. In Autonomous Litter Collecting Robot with Integrated Detection and Sorting Capabilities by A. Rahman and S. Gupta, the authors provide a component list, simulation analysis of infrared sensors combined with ultrasonic sensors for surrounding awareness, along with a camera assisted with TACO (Trash annotations in context) for surrounding trash identification10. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. Our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles compared to the ultrasonic & infrared sensor + camera assisted with TACO, which can only identify trash and cannot identify obstacles like humans in an ocean shore context.

11. In Autonomous Detection and Sorting of Litter Using Deep Learning and Soft Robotic Grippers by P. Proenca and P. Simoes, the authors provide models of a dual fin ray finger design for the waste collecting mechanism along with its architecture, along with object waste detection analysis utilizing a camera assisted with TACO for surrounding trash identification11. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. Firstly, our vacuum filtration design would ensure more force and simultaneous area of intaking, assisted with a filtration of environmental objects in concept. Second, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles than ultrasonic and infrared sensor + camera assisted with TACO, which can only identify trash and cannot identify obstacles like humans in an ocean shore context.

12. In AI for Green Spaces: Leveraging Autonomous Navigation and Computer Vision for Park Litter Removal by D. Kim and J. Martinez, the authors provide a concise breakdown and analysis of a park litter removal robot12. This design consists of a GPS + Slam under a precise algorithm for autonomous navigation. The design also analyzed 3 different TACO datasets (Trash annotations in context) to determine the most efficient computer vision processing for trash collection. In addition, the final design model displayed utilization of various trash collecting devices, with a conclusion of a rake pickup mechanism giving greatest results. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. Firstly, our vacuum filtration design would ensure more force and simultaneous area of intake, assisted with a filtration of environmental objects in concept. This counters the issue of the analysis of vacuum tested in this paper’s model, where it was too small leading to the inability of collecting big objects, along with a lack of filtration, which gives the ability to selectively avoid collecting environmental objects. Our vacuum system is simulated to be drastically wider with a stronger force. Second, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles than ultrasonic and infrared sensor + camera assisted with TACO, which can only identify trash and cannot identify obstacles like humans in an ocean shore context.

13. In BeWastMan IHCPS: An Intelligent Hierarchical Cyber-Physical System for Beach Waste Management by M. Rizzo and G. Testa, the authors present BIOBLU as a cyber-physical framework for waste-collecting robots, integrating vision-based litter detection with ML, hierarchical control across robot–edge–cloud layers, GNSS/SLAM-based navigation, modular waste-handling mechanisms, sustainable power solutions, and geotagged data analytics to enable efficient, autonomous, and environmentally sustainable cleanup operations13. Our robot provides an abstract design of a filtration vacuum system, with ability to filter out environmental objects and exceeding size items from mass collectible plastic debris, with a compelling force by context. Our autonomous navigation components are near identical in terms of function.

14. In Design a Beach Cleaning Robot Based on AI and Node-RED Interface for Debris Sorting and Monitor the Parameters by T. Mallikarathne and R. Fernando, the authors provide a beach cleaning robot model with a debris-sifting mechanism, AI model utilizing an identification system of collected debris and a Lidar + GPS model for autonomous navigation14. Our model proposes a similar but an alternate approach to the debris collecting device: a filtration vacuum system, with an ability to filter out environmental objects and exceeding size items from mass collectible plastic debris, with a compelling force by context.

15. In Trash Collection Gadget: A Multi-Purpose Design of Interactive and Smart Trash Collector, by H. Zhou and L. Wang, the authors offer a physical prototype of a robot with a similar task: to portably clean ocean shores of its abundance in plastic debris15. This paper also provides experimental data with trash collection rates varying on displacement. This design boasts a portable conveyor belt system and track-equipped wheels. Our robot design provides a more independent system, with theoretical design of applying components regarding autonomous navigation with equipped awareness, along with a filtration vacuum system for efficient, powerful, and selective debris collection.

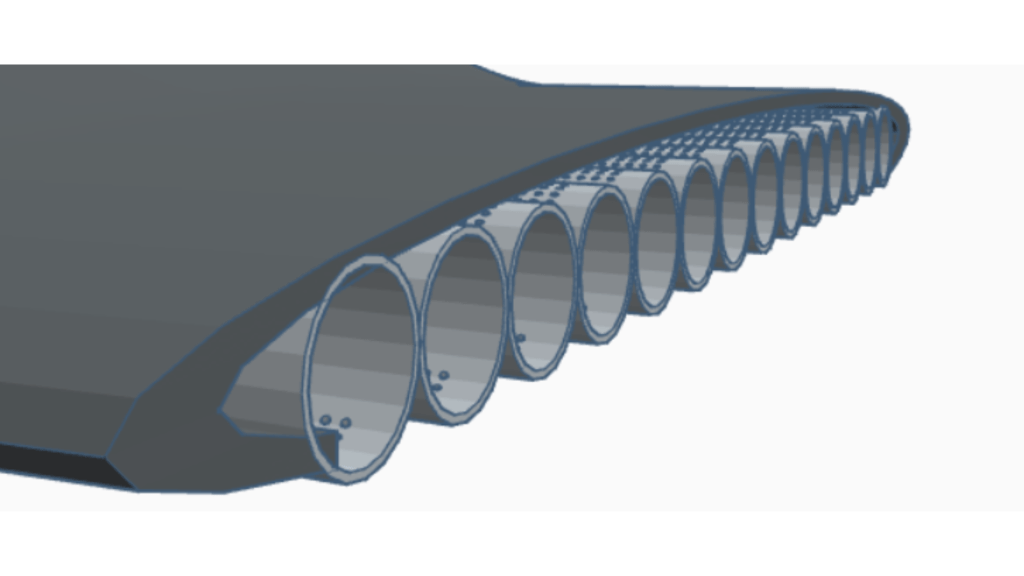

16. In Autonomous Beach Cleaning Robot Controlled by Arduino and Raspberry Pi by R. Mehta and A. Khan, the authors provide a component list of a person-operated beach cleaning machine, with a waste collection mechanism consisting of wiper motor, mesh, and a roller pipe16. Our autonomous beach-cleaning robot design is inspired by the mesh applied collector, as while the inspiring paper does not provide specifically detailed reasons for usage, it has inspired the usage of our nets to separate sufficient debris for collection and small and negligible environmental objects such as sand within our vacuum tube collector.

17. In Design and Fabrication of Beach Cleaning Equipment by J. Patil and V. Sharma, the authors provide a detailed component list and a physical model design of an ocean-shore collection mechanism, equipped with a conveyor chain hook arrangement for scooping17. In addition, there has been a 3D CAD model connected along with methodology based on the structure. Our model provides an abstract filtration vacuum mechanism that has the same objective of efficiently collecting waste in its surroundings, but with a greater force and selectivity. While this paper’s design has a standard 4-wheel locomotion system, our locomotive system boasts a caterpillar-track platform for stable movement through the sandy ocean shore. Our robot design also approaches a robot capable of autonomy, but utilizing self-navigation through the utilization of a Lidar system along with a machine-learning assisted camera.

18. In Beach Cleaning Robot by K. Suresh and D. Ramesh, the authors display a beach-cleaning robot component list with a control system structure, along with a 3D render CAD model and a physical prototype for demonstrating the robot structure18. The models have a 4-wheel locomotive system, along with a conveyor belt debris collection mechanism. Our robot design expands on both of these innovations by applying a caterpillar track locomotion system to move through the sandy shore in stability. Our design also provides an abstract filtration vacuum mechanism that has the same objective as the conveyor belt system of efficiently collecting waste in its surroundings, but with a greater force and selectivity.

19. In Design and Development of Beach Cleaning Machine by A. Narayan and R. Kulkarnipaper, the authors provide a system design of an autonomous beach cleaning robot consisting of a component list along with a control system structure19. The paper also provides hardware design overview details towards certain components, and overviews of the motor control system, garbage recognition algorithm, and the communication interface. Our model provides more detailed component breakdowns and of the autonomous processing of a robot applied on an ocean shore, specifically towards an elevated garbage recognition algorithm under more advanced components.

20. In Smart AI-Based Waste Management in Stations by J. Lee and Y. Chen, the authors provide methodology and experimentation towards applying SLAM and 2-D LiDAR towards autonomous navigation20. Specifically, this paper targets Correlative Scan Matching (CSM) towards precise measurements in navigation. In addition, the utilization of a variety of loop closure detection methods towards reducing noise sensitivity is displayed, for an extreme navigation accuracy. Our model provides a stack of GPS and LiDAR measurement models to expand on robot navigation, by specifically employing a fusion network based on Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) within a LiDAR SLAM pipeline. Regarding the topic of autonomous navigation, our paper applies the concept of LiDAR and GPS to an ocean-shore setting for the robot, where human and environmental obstacles are abundant, needing frequent awareness by the robot to safely avoid interaction with them.

21. In Sweeping Robot Based on Laser SLAM by X. Zhang and Y. Liu, the authors provide a SLAM simulation towards robot self navigation, utilizing a Gmapping an algorithm based on the Rao-Blackwellized particle filtering, within the Gazebo simulating software towards precise LiDAR mapping and navigation tests21. Our model provides a stack of GPS and LiDAR measurement models to expand on robot navigation, by specifically employing a fusion network based on Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) within a LiDAR SLAM pipeline. Regarding the topic of autonomous navigation, our paper applies the concept of LiDAR and GPS to an ocean-shore setting for the robot, where human and environmental obstacles are abundant, needing frequent awareness by the robot to safely avoid interaction with them.

22. In Design and Experimental Research of an Intelligent Beach Cleaning Robot Based on Visual Recognition by Q. Jiang, X. Wang, and X. Zhang, the authors applied reinforcement learning towards experimenting with Khepera IV’s omniscience sensors to amplify the robot’s obstacle identifying capabilities, increasing its autonomous function22. While this paper uses 8 infrared sensors for its simulation analysis, our model provides a stack of GPS and infrared LiDAR measurement models to expand on robot navigation, by specifically employing a fusion network based on Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) within a LiDAR SLAM pipeline. Regarding the topic of autonomous navigation, our paper also applies this objective to an ocean-shore setting for the robot, where human and environmental obstacles are abundant, needing frequent awareness by the robot to safely avoid interaction with them. Our simulations regarding additional variables, such as a Machine-learning assisted camera for easier obstacle identification, has been considered for our python simulations.

23. In Diseño e Implementación de un Prototipo de Robot para la Limpieza de Playas by F. Martínez and D. Sánchez, the authors propose a sustainable beach-cleaning robot design, specifically towards its utilization of a rake sand-sifting mechanism towards collecting debris23. This paper also provides a motion torque analysis. Our robot design implements a vacuum filtration design expanding on this foundation. This mechanism would ensure more force and simultaneous area of intake, assisted with a filtration of environmental objects in concept. Our vacuum system is simulated to be drastically wider with a stronger force.

24. In Design and Implement of Beach Cleaning Robot by M. Rahman, T. Hasan, and S. Akterpaper, the authors propose a beach cleaning robot design with a conveyor belt debris collection mechanism, along with a breakdown of the electrical flow control system architecture satisfying the robot operations24. Our robot design implements a vacuum filtration design expanding on this foundation. This mechanism would ensure more force and simultaneous area of intake, assisted with a filtration of environmental objects in concept. Our vacuum system is simulated to be drastically wider with a stronger force. 25. In EcoBot: An Autonomous Beach-Cleaning Robot for Environmental Sustainability Applications by F. M. Talaat, A. Morshedy, M. Khaled, and M. Salem, the authors present the design and implementation of EcoBot, an autonomous beach-cleaning robot utilizing a mechanical arm debris collection system, and YOLO (You Only Look Once) computer vision for easy debris identification in its surroundings, helping navigation25. The robot also utilizes a variety of sensors, including ultrasonic sensors for a more assisted, autonomous navigation. This paper provides a control system architecture, waste detection analytics, and hardware design models of the robot. Our robot design implements a variety of innovations expanding on this foundation. Firstly, our vacuum filtration design would ensure more force and simultaneous area of debris intake, assisted with a filtration of environmental objects in concept. Our vacuum system is conceptualized towards higher efficiency compared to the mechanical arm debris collection system. Second, our theoretical application of LiDAR working alongside a machine learning assisted camera creates possibility for operating and navigating with a heightened independence for avoiding obstacles, which is a similar alternate approach compared to EcoBot’s YOLO application and ultrasonic sensor system for autonomous navigation.

Detailed Description of the Robot Control System

The system is modular and consists of a sequence of computational and physical blocks that transform the high-level path planning strategy into executable control commands. Each block is explained below.

Vector Field Generator

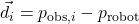

This module constructs a vector field across the robot’s environment by summing attractive and repulsive forces. The attractive force is directed toward the goal, while the repulsive forces are perpendicular to the attractive vector and modulated by a Gaussian function. The resultant vector ![]() at each position is given by:

at each position is given by:

![]()

where ![]() is the target-directed attractive force and

is the target-directed attractive force and ![]() represents the orthogonal repulsive force due to the

represents the orthogonal repulsive force due to the ![]() -th obstacle. The output of this block is a direction of motion

-th obstacle. The output of this block is a direction of motion ![]() , defined as:

, defined as:

![]()

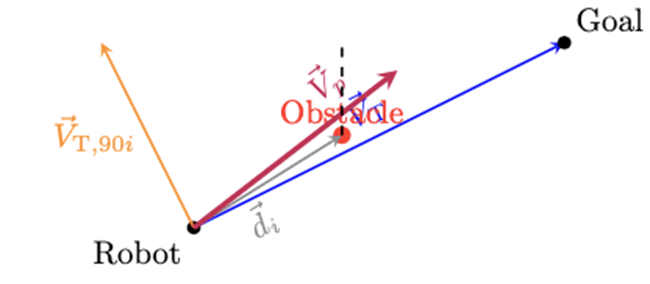

Clarification: Vector Field Generator for Navigation

The Vector Field Generator computes a navigation direction at every position on the map by combining:

- Attractive force towards the goal, guiding the robot’s motion.

- Repulsive forces from obstacles, discouraging movement close to them.

Let ![]() denote the robot’s current position and

denote the robot’s current position and ![]() the goal.

the goal.

Attractive Vector

The normalized attractive vector points directly from the robot to the goal:

![]()

This defines the main direction of travel.

Repulsive Vectors

For each obstacle ![]() at position

at position ![]() :

:

- Compute the vector from robot to obstacle:

- Rotate

by

by  (counterclockwise) to get a unit vector

(counterclockwise) to get a unit vector  perpendicular to the attractive direction.

perpendicular to the attractive direction. - The magnitude of the repulsive effect is determined by a Gaussian envelope:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[w_i = \rho_i \exp \left( - \frac{ \left|\left| p_\text{robot} - p_{\text{obs},i} \right|\right|^2 }{ 2 \sigma^2 } \right)\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-68f460ad88fb70965d9e141e66b944b4_l3.png)

- where

controls repulsion strength, and

controls repulsion strength, and  sets the distance scale.

sets the distance scale. - The total repulsive force is then

.

.

Combined Navigation Vector

The final direction is given by:

![]()

The robot follows the angle of ![]() , which smoothly guides it towards the goal while veering away from obstacles, but always with a component directed to the goal.

, which smoothly guides it towards the goal while veering away from obstacles, but always with a component directed to the goal.

Illustrative Diagram

). The orange arrow is the repulsive (perpendicular) component, modulated in strength by Gaussian proximity to the obstacle (red). The purple arrow is the final direction

). The orange arrow is the repulsive (perpendicular) component, modulated in strength by Gaussian proximity to the obstacle (red). The purple arrow is the final direction  which ultimately steers the robot clear of the obstacle while keeping it headed for the goal.

which ultimately steers the robot clear of the obstacle while keeping it headed for the goal.This construction achieves smooth, goal-directed navigation that can safely skirt obstacles without producing the oscillatory “zig-zag” or deadlocks seen in other potential field methods, as repulsive influences only serve to laterally nudge the heading, never to fully reverse it.

Fourier Transform Block

To ensure that the robot is capable of physically executing the desired trajectory, the heading signal ![]() is analyzed in the frequency domain using a Fourier Transform:

is analyzed in the frequency domain using a Fourier Transform:

![]()

This frequency representation is compared against the known bandwidth of the robot’s actuators. If the frequency content of the signal exceeds this bandwidth, the robot’s speed must be reduced to avoid overshooting or oscillation.

Robot Simulator

This block virtually simulates the robot’s response to the vector field before actual execution. It stores the heading command ![]() and evaluates if the robot can track the path with minimal error. This predictive module prevents infeasible commands from being sent to the physical robot.

and evaluates if the robot can track the path with minimal error. This predictive module prevents infeasible commands from being sent to the physical robot.

Controller

The controller compares the stored heading ![]() with the robot’s actual orientation to compute angular velocity

with the robot’s actual orientation to compute angular velocity ![]() . Additionally, the forward velocity

. Additionally, the forward velocity ![]() is calculated using the centripetal acceleration constraint:

is calculated using the centripetal acceleration constraint:

![]()

The computed forward and angular velocities are then transformed into left and right wheel velocities using the transformation:

![]()

where ![]() is the wheelbase of the robot.

is the wheelbase of the robot.

Robot

The robot executes the commands ![]() by driving its left and right wheels at the corresponding velocities

by driving its left and right wheels at the corresponding velocities ![]() . The robot’s trajectory is continuously corrected based on the heading and velocity feedback from the controller.

. The robot’s trajectory is continuously corrected based on the heading and velocity feedback from the controller.

Robot Plant Model

This block models the dynamic behavior of the robot’s velocity response. In simulation, a first-order linear system with time delay is used:

![]()

where ![]() is a gain factor,

is a gain factor, ![]() is the system time constant, and

is the system time constant, and ![]() is the communication/processing delay. The model is calibrated using step-response experiments and used in simulation to ensure accurate trajectory prediction.

is the communication/processing delay. The model is calibrated using step-response experiments and used in simulation to ensure accurate trajectory prediction.

The integration of these blocks ensures the robot navigates complex environments safely and efficiently, while dynamically adapting to its physical constraints.

The modular state-space model enables the systematic design of feedback controllers for each subsystem, as well as the analysis of system stability, controllability, and observability. The IoT dashboard provides a human-in-the-loop supervisory layer, allowing for remote monitoring and command injection.

This control-centric modeling framework supports the implementation of advanced control strategies (e.g., optimal, adaptive, or robust control) and facilitates future extensions, such as multi-robot coordination or learning-based adaptation, within a principled systems engineering context.

Robot Perception-Decision-Action Workflow

A robust perception-decision-action pipeline is central to the autonomous operation of the beach-cleaning robot. The full control architecture, from environmental sensing to mechanical actuation, can be summarized as follows:

Workflow description:

- Sensors: The robot continuously acquires data on terrain, obstacles, debris, and its internal state using its sensor suite.

- Sensor Fusion and Preprocessing: Raw sensor data are fused and filtered to produce robust, high-confidence environment state estimates (e.g., position, nearby obstacles, detected debris).

- Controller/Decision Logic: This module receives the estimated state, plans a motion/path, and generates actuator commands based on integrated models (e.g., vector-field navigation, feedback control, sorting logic).

- Actuators: Commands are transmitted to all robot effectors (tracks, suspension, vacuum/sieve, separator), interacting with the environment.

- Feedback Loop: The results of the actions update the sensory input, closing the loop for continuous, adaptive operation.

This pipeline ensures that the robot autonomously closes the loop between perception, control, and actuation in a robust and extensible fashion. The workflow has been illustrated in Figure 4.

Integration of Multi-Spectral Camera with AEGIS Machine Learning in Control System

The beach-cleaning robot utilizes an advanced multi-spectral camera system equipped with the AEGIS machine learning (ML) application to achieve precise debris identification. This integration plays a critical role in the robot’s perception and control architecture.

State-Space Representation

In the modular state-space modeling framework, the multi-spectral camera sensor output, enhanced via AEGIS ML-based debris classification, is represented as a key sensor state variable denoted by ![]() . This state captures the processed debris detection signal within the robot’s environment.

. This state captures the processed debris detection signal within the robot’s environment.

Mathematically, the sensor dynamics can be modeled by a first-order linear system with external environmental debris input ![]() :

:

![]()

where ![]() represents the sensor decay or filtering rate, and

represents the sensor decay or filtering rate, and ![]() models the sensor response gain.

models the sensor response gain.

Influence on Robot Commands

The debris detection state ![]() directly impacts actuator commands responsible for waste collection. Specifically, the uptake subsystems for vacuum and sieve adjust their actuation based on the debris detection signal, as reflected by the dynamics:

directly impacts actuator commands responsible for waste collection. Specifically, the uptake subsystems for vacuum and sieve adjust their actuation based on the debris detection signal, as reflected by the dynamics:

![]()

![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() represent the sieve speed and vacuum pressure states, respectively, and

represent the sieve speed and vacuum pressure states, respectively, and ![]() is the actuator setpoint command.

is the actuator setpoint command.

Here, the inclusion of ![]() in the input to the sieve speed dynamics indicates that increased debris detection results in intensified sieve operation. Thus, the ML-driven sensor state dynamically modulates waste collection mechanisms.

in the input to the sieve speed dynamics indicates that increased debris detection results in intensified sieve operation. Thus, the ML-driven sensor state dynamically modulates waste collection mechanisms.

Control Architecture Implications

While the debris detection signal ![]() is part of the overall state vector

is part of the overall state vector ![]() , the ML component also interfaces with higher-level decision modules within the STM32/ESP32 microcontroller. The system leverages AEGIS’s classification outputs to:

, the ML component also interfaces with higher-level decision modules within the STM32/ESP32 microcontroller. The system leverages AEGIS’s classification outputs to:

- Differentiate between environmentally harmful debris and benign objects,

- Selectively activate actuators for targeted waste collection,

- Prioritize navigation paths toward debris-congested areas,

- Reduce false-positive activations through adaptive machine learning inference.

This perception-driven feedback creates an adaptive control loop where sensor-derived knowledge informs and adjusts robot actions in real time.

The integration of the multi-spectral camera and AEGIS ML technology is formally encapsulated as a measurable state ![]() in the robot’s state-space model. Its influence cascades through the control hierarchy, enhancing vacuum and sieve actuation and enabling perception-informed autonomous behavior.

in the robot’s state-space model. Its influence cascades through the control hierarchy, enhancing vacuum and sieve actuation and enabling perception-informed autonomous behavior.

This design approach ensures robust, selective, and efficient debris cleanup by coupling advanced sensing and machine learning tightly with control system dynamics.

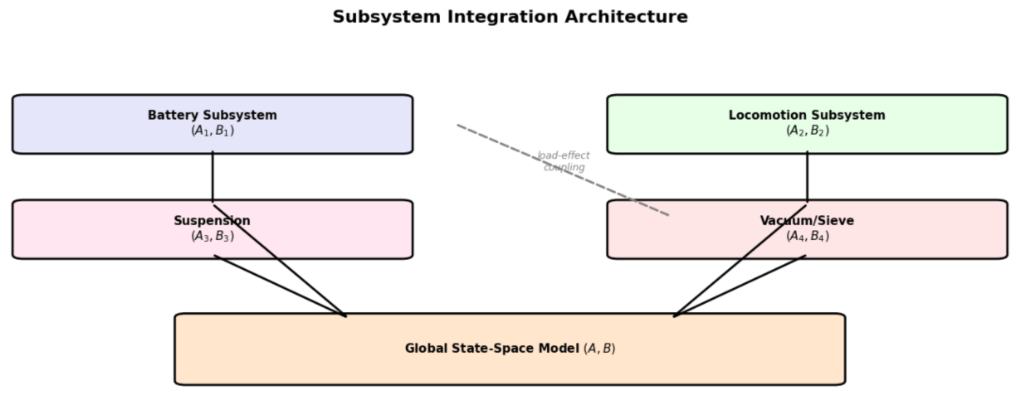

Construction of the Global State Space Model

The state-space representation introduced earlier has the compact form

![]()

but the process by which subsystem dynamics are combined into the global matrices ![]() and

and ![]() was not previously detailed. We provide that explanation here.

was not previously detailed. We provide that explanation here.

Subsystem Equations

Each physical subsystem—battery, locomotion, suspension, vacuum/sieve, sensors—is first described by a local state equation of the form

![]()

where ![]() are subsystem states,

are subsystem states, ![]() are local inputs, and

are local inputs, and ![]() ,

, ![]() are subsystem dynamics matrices. For example:

are subsystem dynamics matrices. For example:

- Battery model:

[state-of-charge, bus voltage],

[state-of-charge, bus voltage], - Motion model:

[position, heading, track velocity],

[position, heading, track velocity], - Suspension:

,

, - Vacuum/sieve:

,

, - Environmental load:

(disturbance), etc.

(disturbance), etc.

Stacking Procedure

The global state vector ![]() is formed by concatenation:

is formed by concatenation:

![]()

with dimension ![]() . Similarly, the global input vector is

. Similarly, the global input vector is

![]()

with dimension ![]() .

.

If subsystems are completely decoupled, the global matrices take block-diagonal form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[A = \begin{bmatrix}A_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\0 & A_2 & \cdots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \cdots & A_k\end{bmatrix}, \qquadB = \begin{bmatrix}B_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\0 & B_2 & \cdots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \cdots & B_k\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-92f8d63b126ef43192599bef01b1dbed_l3.png)

In practice, beach operation introduces couplings between subsystems (e.g., suspension deformation affects locomotion drag; vacuum load affects battery dynamics). These appear as

off-diagonal blocks in ![]() and

and ![]() . For instance, the coupling between track velocity

. For instance, the coupling between track velocity ![]() and suspension

and suspension ![]() is encoded as a nonzero off-diagonal entry

is encoded as a nonzero off-diagonal entry ![]() .

.

Visual Schematic

The stacking can be visualized as shown in Figure 5, where local subsystem dynamics are assembled into the global model:

In short, the complete state-space model is obtained by stacking all subsystem equations in block form and explicitly adding off-diagonal terms for physical couplings. This method makes the structure of ![]() and

and ![]() transparent, and provides a modular pathway to update the global dynamics whenever subsystems are refined or re-identified.

transparent, and provides a modular pathway to update the global dynamics whenever subsystems are refined or re-identified.

Consistent State-Space Model Definitions and Simplified Analysis

The core dynamics of the beach-cleaning robot are captured within a state-space modeling framework. To avoid ambiguity, we provide explicit definitions for each symbol and simplify the presentation to reflect the actual implementation.

State-Space Model Structure

The system is modeled (possibly with both linear and nonlinear terms) as

(5) ![]()

(6) ![]()

Where:

is the state vector (with all main subsystem states)

is the state vector (with all main subsystem states) is the input vector (external controls, setpoints)

is the input vector (external controls, setpoints) is the output vector (sensor or monitored outputs)

is the output vector (sensor or monitored outputs) are system matrices of appropriate dimension

are system matrices of appropriate dimension represents potentially nonlinear coupling (e.g., position kinematics)

represents potentially nonlinear coupling (e.g., position kinematics)

Explicit State and Input Definitions

For the implemented and simulated model, the principal states are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[x(t) =\begin{bmatrix}x_1 \\x_2 \\x_3 \\x_4 \\x_5 \\x_8 \\x_{13} \\x_{15} \\x_{16}\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\text{Battery SoC} \\\text{Bus voltage (V)} \\\text{Debris detection signal} \\\text{Position } x \text{ (m)} \\\text{Position } y \text{ (m)} \\\text{Orientation } \theta \text{ (rad)} \\\text{Track velocity (m/s)} \\\text{Sieve rotational speed} \\\text{Vacuum subsystem pressure}\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b95d64af0a70f76dad0babfe0aab7067_l3.png)

The input vector is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[u(t) =\begin{bmatrix}u_1 \\u_2 \\u_3 \\u_4\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\text{Remote track command} \\\text{Solar charging input} \\\text{Environmental disturbance (debris)} \\\text{Actuator setpoint (vacuum/sieve)}\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-701224151f06783f8b35726d4dc39ebe_l3.png)

Subsystem Dynamics

The system is block modular. The major subsystems are:

Power Subsystem:

(7) ![]()

(8) ![]()

with ![]() SoC,

SoC, ![]() bus voltage,

bus voltage, ![]() a function of actuators.

a function of actuators.

Debris Sensor Filter:

(9) ![]()

with ![]() the debris/environment disturbance input.

the debris/environment disturbance input.

Tracks (locomotion):

(10) ![]()

where ![]() is a (potentially feedback-controlled) motor command.

is a (potentially feedback-controlled) motor command.

Position/heading (kinematics):

(11) ![]()

(12) ![]()

(13) ![]()

Vacuum and sieve:

(14) ![]()

(15) ![]()

Summary Table of Variables

| Symbol | Meaning | Python Variable |

|---|---|---|

| x1 | Battery SoC (state-of-charge) | x1 |

| x2 | Bus voltage | x2 |

| x3 | Debris sensor signal | x3 |

| x4 | x-position | x4 |

| x5 | y-position | x5 |

| x8 | Orientation (heading, radians) | x8 |

| x13 | Track velocity | x13 |

| x15 | Sieve speed | x15 |

| x16 | Vacuum pressure | x16 |

| u1 | Remote (track) command | u1 |

| u2 | Solar charger input | u2 |

| u3 | Debris/environment disturbance | u3 |

| u4 | Vacuum/sieve actuator setpoint | u4 |

This notation therefore covers all equations used in the theoretical section and in the practical simulation framework, ensuring clarity, reproducibility, and ease of extension for further development.

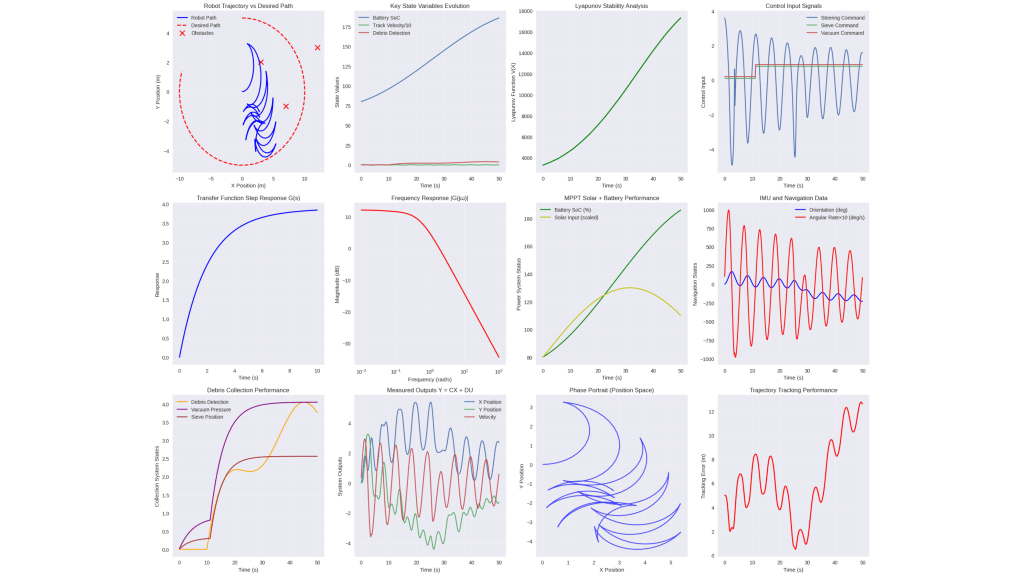

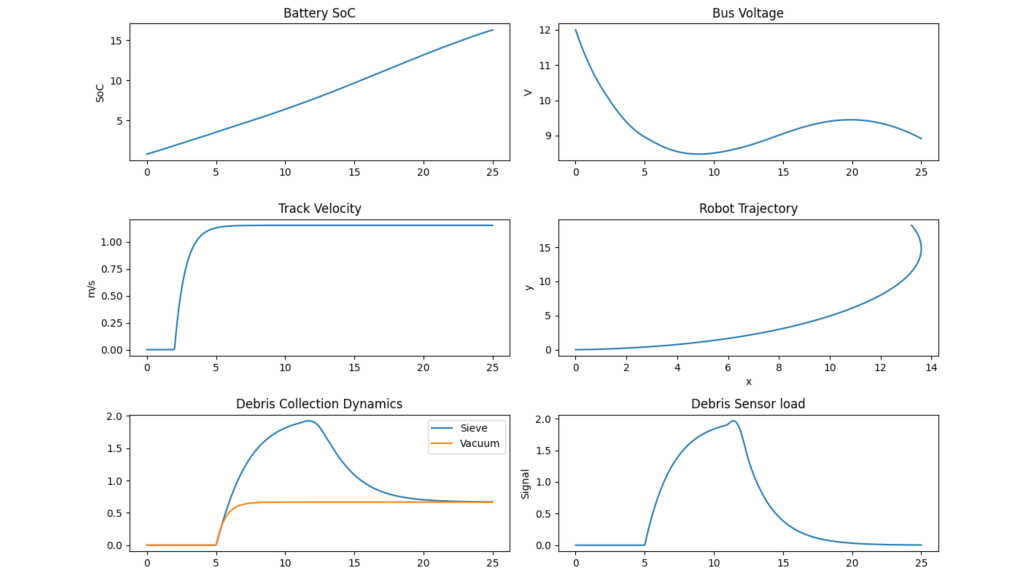

Simulation Implementation and Role in Design

A comprehensive simulation framework was developed and implemented for the autonomous beach-cleaning robot to verify theoretical models, validate subsystem interactions, and inform overall design choices.

Implementation and Code Structure

The simulator, written in Python, includes explicit code for each major subsystem and their interconnections. Key components and modeling approaches are:

- Power Subsystem: Modeled with differential equations for battery state-of-charge (

) and bus voltage (

) and bus voltage ( ):

):

![]()

![]()

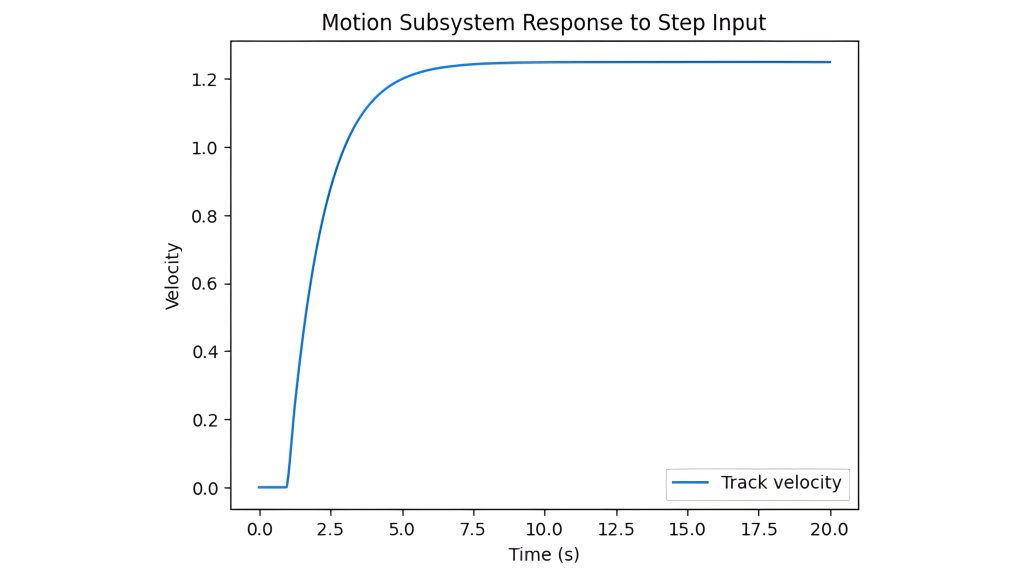

- Motion Subsystem: The velocity of the robot’s tracks,

, is governed by

, is governed by

![]()

- Debris Detection Subsystem:

![]()

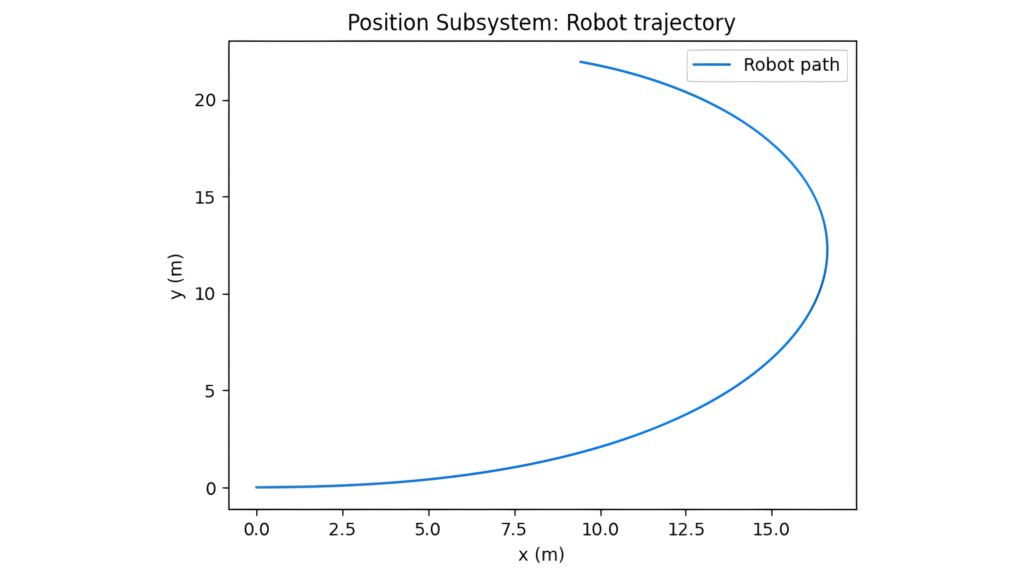

- Position Kinematics and Navigation:

![]()

![]()

![]()

- Vacuum and Sieve Subsystems:

![]()

![]()

- Integrated System: All equations are stacked forming the system dynamics

![]()

where ![]() aggregates all subsystem states and

aggregates all subsystem states and ![]() is the input vector.

is the input vector.

The code utilizes Numpy, scipy.integrate.solve_ivp for integration, and matplotlib for plotting simulation results.

Use of Simulation Outputs in Robot Design

- Subsystem Validation: Each modeled subsystem behaved as predicted, confirming stability (e.g., under Lyapunov analysis) and controllability.

- Integrated Behavior: Simulations produced trajectories for robot position, SoC (State of Charge), and actuator/sensor states, helping validate that control strategies and couplings work as intended.

- Design Decisions Guided by Simulation:

– Verified that hardware and control constraints (such as actuator bandwidth) were respected through frequency-domain analysis (e.g., Fourier transforms).

– Confirmed that system outputs, such as tracking performance and robustness, met specification through RMS error analysis and Monte Carlo robustness tests.

– Supported selection and tuning of controller parameters for safe, efficient, and reliable operation under expected environmental disturbances.

- Reported Results: Figures throughout the paper are direct outputs from the simulation, demonstrating transient responses, SoC and voltage stability, trajectory tracking, and subsystem interplay.

Frequency-Based Speed Adjustment Algorithm

To ensure accurate trajectory tracking without exceeding actuator physical limitations, the robot’s heading command ![]() is processed through a frequency-domain analysis. This approach guarantees the actuator bandwidth constraints are respected, preventing overshoot and oscillatory behavior.

is processed through a frequency-domain analysis. This approach guarantees the actuator bandwidth constraints are respected, preventing overshoot and oscillatory behavior.

Frequency Content Analysis

The desired heading signal ![]() is converted to the frequency domain via the Fourier Transform:

is converted to the frequency domain via the Fourier Transform:

![]()

The magnitude spectrum ![]() is inspected to identify the bandwidth characteristics of the command.

is inspected to identify the bandwidth characteristics of the command.

Actuator Bandwidth Constraint

Let ![]() denote the known cutoff frequency of the robot’s actuators, determined from actuator specifications and empirical testing. The actuator is assumed capable of faithfully tracking input signals with frequency components below

denote the known cutoff frequency of the robot’s actuators, determined from actuator specifications and empirical testing. The actuator is assumed capable of faithfully tracking input signals with frequency components below ![]() , while higher frequencies induce errors or mechanical strain.

, while higher frequencies induce errors or mechanical strain.

Speed Reduction Algorithm

The algorithm to adjust the robot’s speed based on the heading signal’s frequency content is as follows:

1. Compute the power spectral density (PSD) of ![]() from

from ![]() .

.

2. Define the high-frequency energy as

![]()

3. Define the total energy as

![]()

4. Calculate the ratio

![]()

5. If ![]() exceeds a threshold

exceeds a threshold ![]() (e.g.,

(e.g., ![]() ), indicating significant high-frequency content, reduce the forward speed

), indicating significant high-frequency content, reduce the forward speed ![]() proportionally according to:

proportionally according to:

![]()

where ![]() is a tuning parameter (

is a tuning parameter (![]() ) controlling the sensitivity of speed reduction.

) controlling the sensitivity of speed reduction.

6. Recalculate the heading signal ![]() corresponding to the new reduced speed and repeat the frequency analysis until

corresponding to the new reduced speed and repeat the frequency analysis until ![]() .

.

This iterative speed scaling ensures that the command trajectory remains within actuator capabilities by smoothing out rapid heading changes that exceed physical limits.

Rationale and Literature Context

The approach is consistent with established control strategies where:

- High-frequency reference components cause actuator saturation or tracking errors, compromising system stability.

- Smoothing the input signal by reducing command speeds limits bandwidth demand to actuator feasible range.

- The thresholding parameter

and reduction factor

and reduction factor  can be tuned based on empirical actuator response and robustness margins.

can be tuned based on empirical actuator response and robustness margins.

In effect, this frequency-domain speed adjustment functions as a bandwidth-aware trajectory scaling method, foundational to the robot’s control framework. By rigorously linking heading signal spectral content to speed commands, the system prevents actuator saturation and promotes robust, precise beach-cleaning operations.

Control Systems Structure and Background

Overall State Space Model for Beach Cleaning Robot

Identifying Subsystems and States

From the overall system diagram, the major subsystems and their representative state variables can be listed as follows:

| Subsystem | Example State Variables |

|---|---|

| MPPT Solar + Battery | Battery SoC (x1), Bus voltage (x2) |

| Multi-Spectral Sensor (AEGIS) | Last detected debris type (x3) |

| LiDAR SLAM (Luminar IRIS) | Robot position/heading (x4, x5) |

| GPS | Robot position (x6, x7) |

| IMU | Orientation, angular rates (x8, x9, x10) |

| Ultrasonic Sensors | Obstacle distances (x11) |

| STM32/ESP32 Microcontroller | Internal controller states (x12, …) |

| Caterpillar Tracks + DC Motors | Track velocities (x13) |

| Adaptive Suspension | Suspension positions (x14) |

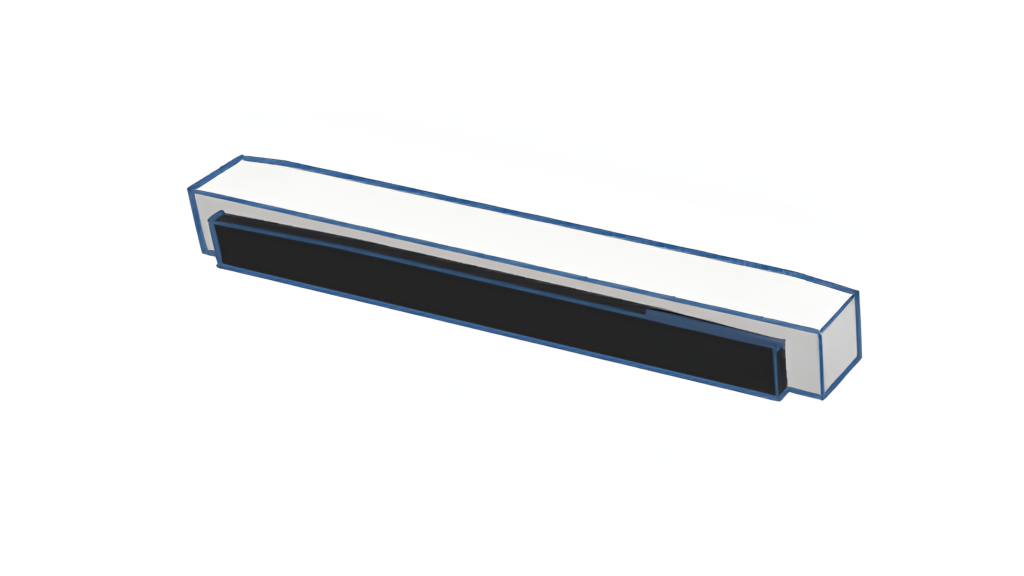

| Rotating Cylindrical Sieve | Sieve angle/speed (x15) |

| Universal Vacuum + Mini Vacuums | Vacuum pressure (x16) |

| Magnetic Separator | Separator state (x17) |

| Node-RED IoT Dashboard | Last command received (x18) |

Input and Output Vectors

Input vector (![]() ) may include:

) may include:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[U = \begin{bmatrix}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3 \\ u_4 \\ \ldots\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d64a7a071b567ba497d0abc075fa6070_l3.png)

where, for example:

-

: Remote commands (from dashboard)

: Remote commands (from dashboard)  : Power input (solar charging)

: Power input (solar charging) : Environmental disturbances (e.g., debris, obstacles)

: Environmental disturbances (e.g., debris, obstacles) : Setpoints for actuators (e.g., motor, vacuum, sieve)

: Setpoints for actuators (e.g., motor, vacuum, sieve)

Output vector (![]() ) may include:

) may include:

- Robot position, orientation, velocity

- Sensor readings (debris type, obstacles)

- Battery SoC, voltage

- Data sent to dashboard

Example State-Space Equations

Let the overall state vector be:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[X = \begin{bmatrix}x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ x_4 \\ x_5 \\ x_6 \\ x_7 \\ x_8 \\ x_9 \\ x_{10} \\ x_{11} \\ x_{12} \\ x_{13} \\ x_{14} \\ x_{15} \\ x_{16} \\ x_{17} \\ x_{18}\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9435ea22961b0c23a4613cd15729eb8b_l3.png)

and the input vector:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[U = \begin{bmatrix}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3 \\ u_4 \\ \ldots\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d64a7a071b567ba497d0abc075fa6070_l3.png)

The general state-space equations are:

![]()

![]()

Block Structure of Matrices

Given the modular nature, the ![]() and

and ![]() matrices are block matrices:

matrices are block matrices:

-

: Diagonal blocks model internal dynamics of each subsystem (e.g., battery, motors, sensors).

: Diagonal blocks model internal dynamics of each subsystem (e.g., battery, motors, sensors). - Off-diagonal blocks: Model coupling between subsystems (e.g., how vacuum pressure affects debris collection).

-

: Maps control inputs to the states they affect (e.g., motor voltage to track velocity).

: Maps control inputs to the states they affect (e.g., motor voltage to track velocity). -

: Maps states to outputs (e.g., which states are sent to the dashboard).

: Maps states to outputs (e.g., which states are sent to the dashboard). -

: Usually sparse; nonzero only if there is a direct, instantaneous effect of input on output.

: Usually sparse; nonzero only if there is a direct, instantaneous effect of input on output.

Example: Expanded Equations for Key Subsystems

a) Power subsystem

![]()

![]()

b) Motion subsystem (tracks)

![]()

c) Debris detection (sensor)

![]()

d) Sieve/vacuum

![]()

![]()

e) Robot position (from LiDAR/GPS/IMU fusion)

![]()

![]()

All these equations can be stacked into the large ![]() and

and ![]() matrices.

matrices.

Full State-Space Model (Symbolic Form)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{bmatrix}\dot{x}_1 \\ \dot{x}_2 \\ \dot{x}_3 \\ \dot{x}_4 \\ \vdots \\ \dot{x}_{17} \\ \dot{x}_{18}\end{bmatrix}=A\begin{bmatrix}x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ x_4 \\ \vdots \\ x_{17} \\ x_{18}\end{bmatrix}+B\begin{bmatrix}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3 \\ \vdots\end{bmatrix}\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0c0a3c2430d16642f2c0aa6e268bc119_l3.png)

![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are constructed by combining the dynamics and interactions of all subsystems.

are constructed by combining the dynamics and interactions of all subsystems.

The following gives the control system structure of the entire robot.

Overall Control System Structure

Nonlinear State-Space Representation

The assumption of a linear time-invariant (LTI) system in modeling the robot dynamics is not fully justifiable for beach environments. Sand deformation, actuator slip, suspension compliance, and debris interactions introduce pronounced nonlinearities that cannot be ignored without compromising model validity. To address this criticism, we reformulate the dynamics using a nonlinear state-space model:

(16) ![]()

where ![]() is the full robot state vector,

is the full robot state vector, ![]() is the input vector,

is the input vector,

and ![]() are nonlinear vector fields capturing the coupling between subsystems and the environment.

are nonlinear vector fields capturing the coupling between subsystems and the environment.

Example Nonlinear Dynamics For the motion subsystem with track velocity ![]() and orientation

and orientation ![]() , we include nonlinear slip and drag effects:

, we include nonlinear slip and drag effects:

(17) ![]()

(18) ![]()

(19) ![]()

where ![]() models quadratic velocity drag due to granular resistance in sand. Unlike the linear model, this representation reflects how resistance grows nonlinearly with speed.

models quadratic velocity drag due to granular resistance in sand. Unlike the linear model, this representation reflects how resistance grows nonlinearly with speed.

Suspension–Track Coupling Suspension deformation (![]() ) interacts with track dynamics:

) interacts with track dynamics:

(20) ![]()

(21) ![]()

where ![]() are nonlinear functions obtained from physical modeling or simulational identification. This form allows the model to capture wheel sinkage and terrain-dependent resistance.

are nonlinear functions obtained from physical modeling or simulational identification. This form allows the model to capture wheel sinkage and terrain-dependent resistance.

Energy Dynamics The battery dynamics incorporate time-varying solar efficiency ![]() and nonlinear load dependence:

and nonlinear load dependence:

(22) ![]()

(23) ![]()

where ![]() depends nonlinearly on actuator states

depends nonlinearly on actuator states ![]() .

.

Nonlinear Coupling Stacking all subsystems, we obtain the nonlinear system

(24) ![]()

where ![]() encodes all nonlinear and time-varying terms. This structure preserves the tractability of the LTI backbone while incorporating essential nonlinearities from sand interaction, suspension deformation, and actuator coupling.

encodes all nonlinear and time-varying terms. This structure preserves the tractability of the LTI backbone while incorporating essential nonlinearities from sand interaction, suspension deformation, and actuator coupling.

Stability Considerations To assess stability of the nonlinear dynamics, we adopt Lyapunov’s direct method. For instance, the quadratic candidate

(25) ![]()

yields

(26) ![]()

Asymptotic stability is guaranteed if ![]() for all

for all ![]() , which motivates robust or adaptive control designs that explicitly account for nonlinear terms.

, which motivates robust or adaptive control designs that explicitly account for nonlinear terms.

Lyapunov-Based Nonlinear Control for Beach-Operating Robot

We refine the dynamics to a control-affine nonlinear form with environment-induced (sand) nonlinearities and matched uncertainties:

(27) ![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are known from nominal mechanics, and

are known from nominal mechanics, and ![]() captures terrain-dependent effects (slip, sinkage, quadratic drag, debris) that are not well-approximated by LTI models.

captures terrain-dependent effects (slip, sinkage, quadratic drag, debris) that are not well-approximated by LTI models.

We assume the matched structure

(28) ![]()

i.e., the dominant nonlinearities/uncertainties enter through the same channel as the control (a standard assumption for ground robots with actuator-dominated uncertainties).

Reference model and tracking error. Let ![]() be a desired (feasible) reference state with dynamics

be a desired (feasible) reference state with dynamics

(29) ![]()

where ![]() is a bounded reference command. Define the tracking error

is a bounded reference command. Define the tracking error ![]() .

.

Subtracting (as shown in Equation 29) from (as shown in Equation 27) yields

(30) ![]()

where we add and subtract ![]() with a designer-chosen

with a designer-chosen ![]() and pack all reference-model mismatch into

and pack all reference-model mismatch into

![]() . Choosing

. Choosing ![]() Hurwitz (e.g., by LQR or pole-placement on

Hurwitz (e.g., by LQR or pole-placement on ![]() ) stabilizes the nominal linear part.

) stabilizes the nominal linear part.

Linearly parameterized uncertainty and robust residual. We adopt a standard linearly parameterized representation for the leading nonlinearities:

(31) ![]()

where ![]() is a known regressor (e.g., basis of quadratic drag

is a known regressor (e.g., basis of quadratic drag ![]() , slip maps, load currents),

, slip maps, load currents), ![]() are unknown constant (or slowly varying) parameters, and

are unknown constant (or slowly varying) parameters, and ![]() collects the residual unmodeled part with known bound

collects the residual unmodeled part with known bound ![]() .

.

Adaptive–robust control law. Let ![]() be the parameter estimate and

be the parameter estimate and ![]() . Consider the control

. Consider the control

(32) ![]()

with gains ![]() and boundary layer

and boundary layer ![]() , where

, where ![]() solves the Lyapunov equation

solves the Lyapunov equation

(33) ![]()

The last term in Eq 32 is a continuous robustification (a saturation in the direction ![]() ) that dominates the bounded residual

) that dominates the bounded residual ![]() . The adaptive law is chosen as

. The adaptive law is chosen as

(34) ![]()

with ![]() (adaptation rate) and a small

(adaptation rate) and a small ![]() (

(![]() -modification) to prevent parameter drift under disturbances and noise.

-modification) to prevent parameter drift under disturbances and noise.

Lyapunov analysis.

Define the composite Lyapunov function

(35) ![]()

Along trajectories of (as shown in Equation 30) with (as shown in Equation 31)-(as shown in Equation 34), and using (as shown in Equation 33),

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(36) ![]()

where ![]() projects the error along the input directions and

projects the error along the input directions and![]() denotes the one-norm of the saturated vector. The cross term

denotes the one-norm of the saturated vector. The cross term ![]() cancels with

cancels with ![]() . Bounding

. Bounding ![]() and using

and using ![]() gives

gives

![]()

(37) ![]()

Thus ![]() and

and ![]() are bounded and

are bounded and ![]() with a residual size that can be made arbitrarily small by choosing

with a residual size that can be made arbitrarily small by choosing ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() large and

large and ![]() small (while respecting actuator limits). If

small (while respecting actuator limits). If ![]() and

and ![]() then

then ![]() , yielding asymptotic convergence

, yielding asymptotic convergence ![]() .

.

Implementation notes.

- Choosing

: include terms known to dominate on sand, e.g., longitudinal quadratic drag

: include terms known to dominate on sand, e.g., longitudinal quadratic drag  , slip ratio polynomials, load currents coupling to

, slip ratio polynomials, load currents coupling to  and yaw rate, and suspension compression

and yaw rate, and suspension compression  (sinkage).

(sinkage). - Projection/saturation: enforce actuator and parameter bounds with a projection operator in Eq 34 and with command clipping on

.

. - Tuning: pick

by LQR on

by LQR on  to shape

to shape  , then solve Eq 33 for

, then solve Eq 33 for  , and finally tune

, and finally tune  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Single-Channel Example: Track Speed With Quadratic Sand Drag. Consider the scalar track-speed channel (suppressing the index):

(38) ![]()

with unknown ![]() (quadratic granular drag) and bounded disturbance

(quadratic granular drag) and bounded disturbance ![]() .

.

Let ![]() be a bounded desired speed with bounded

be a bounded desired speed with bounded ![]() and define the error

and define the error ![]() . Choose the control

. Choose the control

(39) ![]()

with ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the adaptation

, and the adaptation

(40) ![]()

The closed-loop error dynamics become

(41) ![]()

with ![]() . Using the Lyapunov function

. Using the Lyapunov function

(42) ![]()

its derivative along trajectories satisfies

![]()

(43) ![]()

where ![]() .

.

Thus ![]() is bounded and converges to an

is bounded and converges to an ![]() neighborhood of zero for

neighborhood of zero for ![]() , with asymptotic convergence if

, with asymptotic convergence if ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Remark (unmatched effects and backstepping). If a subset of terrain forces enters outside the input channel, e.g., ![]() with

with ![]() , we apply a backstepping/ISS design: choose a virtual control

, we apply a backstepping/ISS design: choose a virtual control ![]() to stabilize the

to stabilize the ![]() -affected states and make

-affected states and make ![]() enter as an ISS disturbance in the final error. The same Lyapunov template extends by adding cross terms for the backstepping layers and using small-gain/ISS arguments to guarantee practical stability in the presence of residual unmatched dynamics.

enter as an ISS disturbance in the final error. The same Lyapunov template extends by adding cross terms for the backstepping layers and using small-gain/ISS arguments to guarantee practical stability in the presence of residual unmatched dynamics.

The adaptive–robust law (as shown in Equation 32)–(as shown in Equation 34) yields Lyapunov-guaranteed practical tracking for the nonlinear beach dynamics, explicitly covering quadratic drag, slip-induced regressors, and bounded unmodeled effects. The scalar example (as shown in Equation 38)–(as shown in Equation 40) illustrates how the same logic specializes in the dominant sand-drag channel.

Concrete Regressor Choice and LQR Pre-Design

To implement the adaptive–robust controller of Section 10.3 we must choose a physically meaningful regressor ![]() that captures the dominant nonlinearities present when the robot operates on sand. Below we state a recommended regressor tailored to the 18-state ordering used in this work.

that captures the dominant nonlinearities present when the robot operates on sand. Below we state a recommended regressor tailored to the 18-state ordering used in this work.

Tailored regressor ![]() .} Let the state vector be ordered as:

.} Let the state vector be ordered as:

![]()

with meanings as in the paper (SoC, bus voltage, debris signal, ![]() position, GPS, orientation

position, GPS, orientation ![]() , … , track velocity

, … , track velocity ![]() , suspension

, suspension ![]() , sieve

, sieve ![]() , vacuum

, vacuum ![]() , etc.).

, etc.).

A compact but effective regressor basis that captures sand/granular effects, slip, and actuator coupling is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Y(X,t) :=\begin{bmatrix}v|v| \\\operatorname{sgn}(v)\,v^2 \\[4pt]v \, z \\z \\\dot z \\\text{slip}(v,\omega) \\\omega v \\v \, x_{15} \\x_{15} \\x_{16} \\1\end{bmatrix}^\top\quad\in\mathbb{R}^{1\times p},\]](https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7337e3ea9f3d6974d543af10b03d78ec_l3.png)

where

is track speed (m/s),

is track speed (m/s), is suspension compression / sinkage proxy,

is suspension compression / sinkage proxy, (or the yaw rate/steering-related state) and

(or the yaw rate/steering-related state) and  is a slip ratio model such as

is a slip ratio model such as  (with wheel radius

(with wheel radius  and small

and small  for regularization),

for regularization), are sieve and vacuum variables that nonlinearly couple into the motor load.

are sieve and vacuum variables that nonlinearly couple into the motor load.

The regressor is assembled into the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() by repeating or selecting appropriate rows for each controlled channel (e.g., the first few rows above enter the drive channel, others enter vacuum/sieve channels). This choice captures (i) quadratic drag

by repeating or selecting appropriate rows for each controlled channel (e.g., the first few rows above enter the drive channel, others enter vacuum/sieve channels). This choice captures (i) quadratic drag ![]() from granular flow, (ii) suspension–velocity coupling

from granular flow, (ii) suspension–velocity coupling ![]() , (iii) slip ratio nonlinearity, and (iv) actuator-load couplings.

, (iii) slip ratio nonlinearity, and (iv) actuator-load couplings.

Parameterization. Model the dominant unknown terms entering the actuator (matched) channel as

![]()

with unknown ![]() and bounded residual ||d(X,t)||

and bounded residual ||d(X,t)||![]() . The adaptive law (as shown in Equation 34) and robustification in (as shown in Equation 32) (Section 10.3) are used to estimate

. The adaptive law (as shown in Equation 34) and robustification in (as shown in Equation 32) (Section 10.3) are used to estimate ![]() online and reject the residual.

online and reject the residual.

Pre-computed LQR for motion sub-block (drive + heading). Practical controller design benefits from a linear pre-compensator. Linearize the kinematics about small headings and near-nominal speed and design an LQR acting primarily on the motion states ![]() = (longitudinal position, track velocity, orientation). Using a stabilizable linearization we computed a pre-gain

= (longitudinal position, track velocity, orientation). Using a stabilizable linearization we computed a pre-gain ![]() (applied as a baseline feedback term for

(applied as a baseline feedback term for ![]() ).

).

Under the modest linearization and the reasonable physical assumptions described in the implementation notes, the computed motion sub-block LQR gain is

![]()

so that for the reduced state vector ![]() the baseline motor command is

the baseline motor command is

![]()

This gain was computed to prioritize position error reduction and speed regulation while keeping the baseline command within typical actuator ranges. The adaptive–robust law (Section 10.3) augments this baseline with online estimates of granular drag and a robust saturation term; the combined law is

![]()

where ![]() picks the rows of

picks the rows of ![]() affecting the drive channel.

affecting the drive channel.

Implementation and actuator-limits. Clip the final command to actuator constraints:

![]()

Use projection or a bounded adaptive law for ![]() to avoid parameter drift. When a full identified linearization

to avoid parameter drift. When a full identified linearization ![]() is available we recommend solving the continuous-time Algebraic Riccati Equation to compute a full-state LQR

is available we recommend solving the continuous-time Algebraic Riccati Equation to compute a full-state LQR ![]() and using that in place of the reduced pre-gain above.

and using that in place of the reduced pre-gain above.

Necessity of Advanced Control Theory for Autonomous Beach Cleaning Robots

The operation of a fully autonomous beach-cleaning robot in a real coastal environment presents a set of technical challenges that cannot be reliably addressed using only simple control strategies or conventional automation. Adopting advanced control theory, including state-space modeling, feedback design and frequency domain tools, such as Fourier analysis is essential for the following reasons:

High Environmental Complexity and Dynamics

The beach environment is inherently unstructured and highly dynamic: surfaces range from shifting, compressible sand, to hard picked wet zones, traversed by unexpected slopes, debris and obstacles such as rocks, seaweed, driftwood and human artifacts. Environmental conditions continuously change due to tides, wind and human activity. Simple set point and threshold-based control is inadequate to ensure robust navigation and safe operation under such uncertainty and variation.

Integrated Multi-Subsystem Coordination

The robot must synchronously manage energy harvesting (solar MPPT), power usage, navigation, locomotion, complex sensor fusion (LiDAR, GPS, IMU, multi-spectral camera),advanced actuation (tracks, adaptive suspension, vacuum, sieve), and dynamic debris sorting. State-space models enable precise description of subsystem coupling, interdependencies, and feedback across multiple interacting variables. Classical block-diagram or PID-only approaches cannot capture these relationships, leading to suboptimal or even unstable behavior.

Real-Time Adaptivity and Safety

Navigation and debris collection require adaptive, feedback-driven behavior to respond to dynamic obstacles, terrain disruptions, varying debris loads, and partial system failures. Stability and robustness, guaranteed by Lyapunov and LaSalle theory, are essential to avoid dangerous and damaging actions. Advanced control theory allows the system to maintain performance and safety with quantifiable mathematical guarantees during disturbances or rapid changes.

Trajectory Feasibility and Actuator Limits

Actuator bandwidth (e.g., motors, suspension) is limited; attempting to follow a path beyond the system’s capabilities leads to oscillation or overshoot. Use of the Fourier transform in the trajectory planner ensures reference commands are realizable within hardware constraints, filtering out infeasible control frequencies before execution.

Scalability and Extensibility

A modular state-space framework allows straightforward integration of new control strategies, such as optimal control, multi-robot coordination, and learning-based adaptation. This future-proofs the system as challenges and requirements evolve beyond what simple heuristics or decentralized logic could accommodate.

While simpler engineering solutions (e.g., relay logic, threshold rules, local PID loops) may succeed in highly controlled, uniform environments, they fundamentally lack the reliability, flexibility, and provable safety required for autonomous robots operating in the open, dynamic, and hazardous beachfront. Advanced, theoretically grounded control is not excessive but necessary for robust, adaptive, and efficient real-world environmental cleanup.

Application of Advanced Control Theory to Beach-Cleaning Robot

This section details the application of modern control theory to the beach cleaning robot, with a focus on stability theory, Lyapunov’s direct method, the invariance principle, and advanced stability techniques. The section concludes with a discussion of image-based control as applied to autonomous debris detection and manipulation.

Stability Theory and Advanced Techniques

The stability of the closed-loop system is essential for reliable operation in the unstructured and dynamic beach environment. Consider the non-linear state-space model for the robot:

(44) ![]()

Here ![]() is the full robot state, and

is the full robot state, and ![]() is the input.

is the input.

Lyapunov’s Direct Method

To analyze stability, Lyapunov’s direct method is employed. A continuously differentiable scalar function ![]() is constructed such that:

is constructed such that:

(45) ![]()

and it’s time derivative along system trajectories satisfies:

(46) ![]()

If such a ![]() exists, the equilibrium at

exists, the equilibrium at ![]() is Lyapunov stable. For example for the robot’s DC motor-actuated tracks:

is Lyapunov stable. For example for the robot’s DC motor-actuated tracks:

(47) ![]()

(48) ![]()

Choosing ![]() with

with ![]() yields

yields ![]() for

for ![]() . This ensures asymptotic stability.

. This ensures asymptotic stability.

LaSalle’s Invariance Principle

For systems where ![]() but not strictly negative, LaSalle’s invariance principle applies. The trajectories converge to the largest invariant set where