Abstract

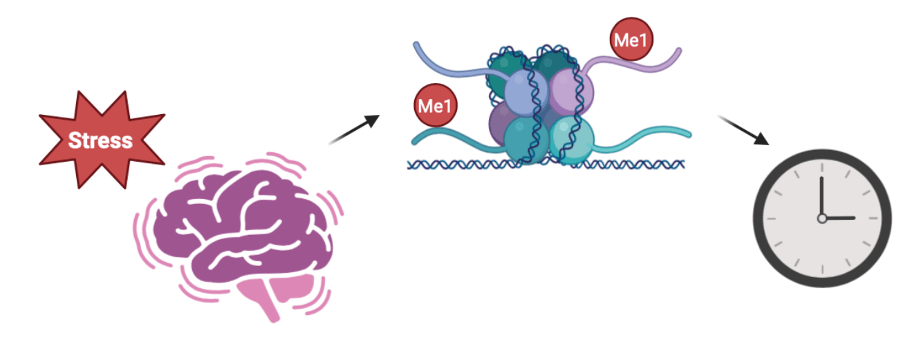

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a chronic psychiatric disorder characterized by long-lasting changes in brain function following traumatic stress exposure. Emerging evidence suggests that epigenetic regulation plays a central role in maintaining the transcriptional effects of stress, yet the specific mechanisms remain elusive. In this study, we established an in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD neuronal model by differentiating human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with retinoic acid and exposing them to chronic cortisol treatment. Integrated RNA-seq and enzymatic methylation sequencing (EM-seq) revealed that the transcription factor KLF9 was significantly downregulated in cortisol-treated cells, accompanied by promoter hypermethylation. Treatment with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza) restored KLF9 expression and reduced promoter methylation, indicating that KLF9 repression is epigenetically mediated. Notably, the downregulation of KLF9 was associated with suppressed expression of circadian clock genes PER1 and BMAL1, which also exhibited promoter hypermethylation. Overexpression of KLF9 rescued PER1 and BMAL1 expression, suggesting a functional link between KLF9 and circadian gene regulation. These findings support a mechanistic model in which chronic stress induces epigenetic silencing of KLF9, leading to disruption of circadian rhythms—key to cognitive and emotional regulation in PTSD. Targeting the KLF9–circadian pathway may represent a conceptual direction for future therapeutic research, although substantial in vivo validation will be required before any clinical relevance can be established.

Keywords: PTSD, SH-SY5Y, KLF9, DNA Methylation, Circadian clock

Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and complex mental illness that occurs after experiencing an event that threatens one’s life or causes significant psychological trauma1‘2. Globally, PTSD affects approximately 3-4% of the population and is closely associated with various traumatic events such as war, torture, abuse, disasters, and accidents3‘4. In particular, long-term follow-up studies of Jewish survivors who were imprisoned in concentration camps by the Nazi regime during World War II have provided important clinical evidence regarding the chronic nature and neurobiological basis of PTSD5‘6. These individuals continued to experience symptoms such as nightmares, insomnia, avoidance behaviors, and hyperarousal decades later, suggesting that PTSD involves persistent neurological restructuring beyond a simple acute response5‘7.

Recently, research has been actively conducted to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of PTSD, focusing on molecular changes occurring in the nervous system exposed to chronic stress. Among these, dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, reduced synaptic plasticity, and epigenetic regulation are proposed as key pathways in the development of PTSD8‘9. Cortisol, a stress hormone, not only regulates the expression of transcription factors and receptors in the brain but can also induce long-term reorganization of gene expression by altering DNA methylation patterns in promoter regions10.

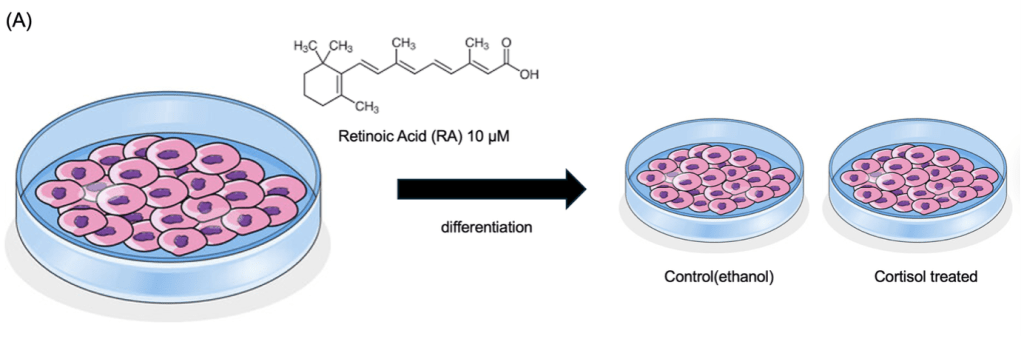

In this study, human-derived neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) were differentiated with retinoic acid and then treated with chronic cortisol for seven days to establish an in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD-associated pathways. Through integrated analysis of RNA sequencing and DNA methylation sequencing data, we identified the transcription factor KLF9 (Krüppel-like factor 9), whose expression decreased while promoter methylation increased in response to cortisol treatment.

KLF9 is known to be a downstream target of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and is involved in neural differentiation and cell survival11‘12; however, its direct connection to the pathophysiology of PTSD has been relatively poorly understood. In this study, based on the hypothesis that reduced KLF9 expression may be associated with altered expression of key circadian clock genes such as PER1 and BMAL1, thereby affecting the expression of circadian clock genes13‘14, subsequent analyses confirmed that treatment with the methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza) partially restored the suppression of these genes.

Thus, this study suggests that epigenetic suppression of KLF9 may contribute to disruptions in circadian gene expression within our in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD, providing a mechanistic hypothesis that could be relevant to stress-related transcriptional changes observed in human disorders. The stress–clock gene–neurological function axis mediated by KLF9 is expected to provide new directions for understanding and developing treatment strategies for various stress-based mental disorders, including PTSD, depression, insomnia, and mood disorders.

Materials & Methods

Cell Culture and Differentiation

Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator. For neuronal differentiation, cells were plated at 40–50% confluency and treated with 10 μM all-trans retinoic acid (RA; Sigma-Aldrich) for 7 days. Culture medium containing RA was replaced every 48 hours.

Chronic Cortisol Treatment

To induce a in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD stress condition, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 nM hydrocortisone (cortisol; Sigma-Aldrich) for 7 days. Cortisol (100 nM) was dissolved in ethanol, and the final vehicle concentration was 0.1% (v/v) in all cultures, including vehicle controls. Cortisol-containing medium was replaced daily to maintain hormone stability. This concentration elicits consistent transcriptional responses without cytotoxicity. Control groups received vehicle (ethanol) in the same volume.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System. Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH using the ΔΔCt method.

| Gene | Forward (5’ -> 3’) | Reverse (5’ -> 3’) |

| NR3C1 | GACTCCAAGCAGCGAAGACT | CTCTGGAACACTGGTCGACC |

| BDNF | GAGCCCTGTATCAACCCAGA | TCAAATACCATGCCCCACCT |

| Arc | CCCTCAGCTCCAGTGATTCA | GTTGTCACTCTCCTGGCTCT |

| KLF9 | TGGTCTCCTTCCTGTGTTCC | GTTGCCTGCATTCTCCACAA |

| PER1 | CACCCTGATGACCCACTCTT | CCTCCTCCTCCATAGCCAAG |

| BMAL1 | CCCTGGGCCATCTCGATTAT | TCATCCAGCCCCATCTTTGT |

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against KLF9(Abcam, ab227920) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 14C10), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signals were detected using ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RNA Sequencing and Analysis

Total RNA from n = 3 independent biological replicates per condition was used for library preparation (NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit). Raw reads were assessed using FastQC v0.11.9 and adapter-trimmed with TrimGalore v0.6.7. Reads were aligned to the human GRCh38 reference genome using STAR v2.7 with default parameters. Gene-level counts were obtained using featureCounts (Subread v2.0).

Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 v1.38.0, with median-ratio normalization and Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction. Genes were considered differentially expressed with adjusted p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1.

EM-seq and Methylation Analysis

Genomic DNA from n = 3 biological replicates per condition was processed using the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit. Reads were trimmed with TrimGalore and mapped using Bismark v0.24.0 with Bowtie2.

CpG methylation calls were extracted using the Bismark methylation extractor, and CpGs with <10× coverage were excluded. Promoters were defined as ±2 kb around the annotated transcription start site (TSS).

Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified using DMRfinder, requiring:

≥5 CpGs per region, ≥20% methylation difference, FDR < 0.05.

RNA-seq and EM-seq datasets were generated from three independent biological replicates per group. Sequencing produced an average of ~40 million reads per sample with >90% alignment rate (Supplementary Table S1). EM-seq libraries demonstrated high conversion efficiency and uniform CpG coverage (Supplementary Table S2).

QC/replicates/softwares

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, all experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates unless otherwise noted. RNA-seq reads were quality-checked using FastQC (v0.11.9), trimmed with TrimGalore (v0.6.7), and aligned to the human GRCh38 reference genome using STAR (v2.7). Gene counts were obtained with featureCounts, and differential expression was analyzed using DESeq2 (v1.38.0) with default normalization and an adjusted p-value < 0.05. For EM-seq, raw reads were processed using TrimGalore and mapped using Bismark (v0.24.0). Methylation calls were extracted with Bismark methylation extractor, and CpG methylation percentages were visualized using IGV. Statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 9, with normality assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test and significance determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Full pipelines and code are available upon request.

5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza) Treatment

To inhibit DNA methylation, cells were treated with 1 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 hours with daily media replacement. Control cells were treated with an equivalent volume of DMSO.

KLF9 Overexpression

Cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding human KLF9 (pCMV-KLF9) or an empty vector (scrambled control) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene expression was analyzed 48 hours post-transfection. The pCMV empty vector was generously provided by Dr. Kim (ChromoGen, Korea).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed using three independent biological replicates (n = 3) unless otherwise noted. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and parametric tests (two-tailed Student’s t-test) were used only when assumptions of normality were met. For RNA-seq, differential expression was determined using DESeq2 with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction. For qRT-PCR analyses involving multiple genes, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Results

RA-Induced Differentiation of SH-SY5Y Cells Establishes a Neuron-Like Model for PTSD Studies

(B) Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells before (top) and after (bottom) RA treatment. Differentiated cells show extended neurites and neuron-like morphology.

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of neuronal differentiation markers. Expression of NR3C1, BDNF, and Arc was significantly increased in differentiated cells compared to proliferative controls. Data represent mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To establish a neuronal phenotype, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were treated with 10 μM retinoic acid (RA) for 7 days (Figure 1A). Prior to differentiation, the cells exhibited a rounded, proliferative morphology with minimal neurite outgrowth and clustered growth patterns. Following RA treatment, cells displayed pronounced neurite extension and increased intercellular connectivity, consistent with a neuron-like phenotype (Figure 1B). These morphological changes were accompanied by molecular alterations, as confirmed by qRT-PCR. Expression levels of NR3C1, BDNF, and Arc—genes associated with stress response and synaptic plasticity—were significantly upregulated in differentiated cells compared to their proliferative counterparts (Figure 1C).

These findings confirm that RA-induced differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells yields a functionally and morphologically neuronal model suitable for downstream investigation of chronic cortisol exposure and PTSD-related pathophysiology.

KLF9 Is Downregulated via Promoter Hypermethylation under Chronic Cortisol Exposure

| Feature | RRBS | EM-seq |

| Principle | Sodium bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Enzymatic conversion using TET2 and APOBEC3A |

| DNA Integrity | High degradation and fragmentation due to harsh bisulfite treatment | Maintains high DNA integrity through mild enzymatic reactions |

| Conversion Accuracy | Moderate; susceptible to incomplete or over-conversion | High; enzymatic reactions provide high-fidelity methylation mapping |

| Coverage | CpG-rich regions only (e.g., CpG islands, promoters) | Genome-wide CpG coverage, including gene bodies and regulatory regions |

| GC Bias | Significant GC bias | Minimal GC bias |

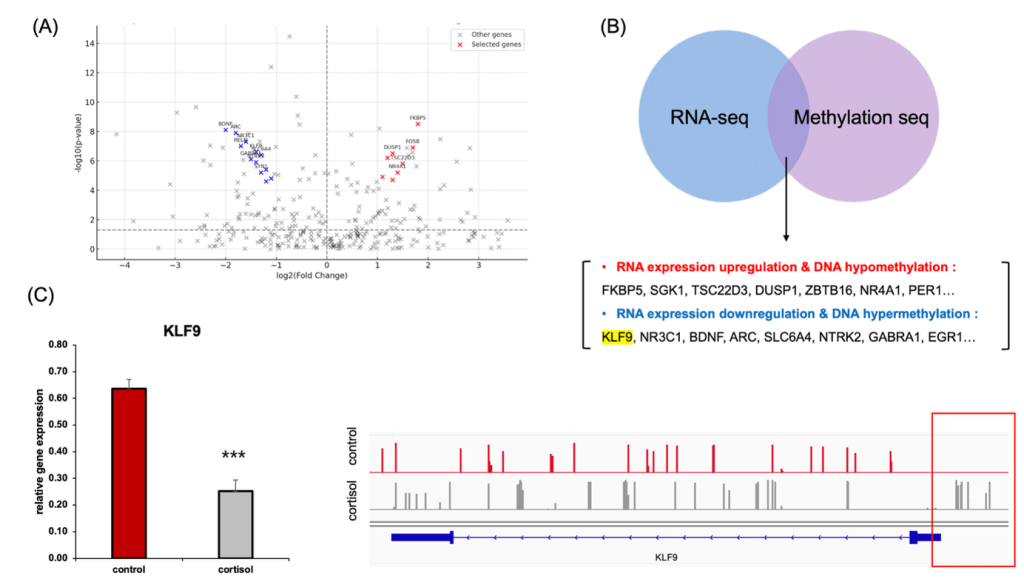

(B) Integration of RNA-seq and EM-seq data identified genes with coordinated transcriptional and epigenetic changes. KLF9 was among the downregulated genes showing promoter hypermethylation.

(C) qRT-PCR confirmed reduced expression of KLF9 in cortisol-treated cells (left). EM-seq gene track visualization shows increased DNA methylation in the KLF9 promoter region under cortisol stress at the 7-day cortisol endpoint (right).

To investigate the epigenetic landscape underlying transcriptional alterations in our in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD. neuronal model, we employed both RNA sequencing and enzymatic methylation sequencing (EM-seq). EM-seq was selected over conventional reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) due to its superior accuracy, DNA integrity preservation, and genome-wide CpG coverage. While RRBS relies on harsh bisulfite treatment and is limited to CpG-rich regions, EM-seq utilizes a mild enzymatic conversion (TET2 and APOBEC3A), allowing for high-fidelity methylation mapping across both promoter and gene body regions with minimal GC bias15‘16 (Figure 2A).

A volcano plot of differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-seq following chronic cortisol exposure using |log₂FC| > 1 and FDR < 0.05 (Figure 2B), and we updated the figure legend to reflect these thresholds (Figure 2B). Several glucocorticoid-responsive genes, such as FKBP5, SGK1, TSC22D3, and DUSP1, were significantly upregulated (red), while key neuroplasticity and circadian regulators—including NR3C1, BDNF, ARC, and KLF9—were markedly downregulated (blue). Notably, KLF9 has been proposed as an extreme candidate for epigenetic silencing under cortisol stress.

To further identify genes showing coordinated transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, we integrated RNA-seq and EM-seq datasets (Figure 2C). This analysis revealed two distinct groups: (1) genes with increased expression and concurrent promoter hypomethylation (e.g., FKBP5, SGK1, NR4A1, PER1), and (2) genes exhibiting decreased expression along with promoter hypermethylation, including KLF9, NR3C1, and BDNF. In particular, KLF9 expression was significantly reduced in the cortisol-treated group, as confirmed by RT-qPCR. Simultaneously, EM-seq-based genetrack analysis revealed marked DNA hypermethylation near the KLF9 promoter (Figure 2D).

These results are consistent with the interpretation that chronic cortisol exposure may contribute to epigenetic repression of KLF9 in this neuronal model.

Epigenetic Silencing of KLF9 are associated with altered expression of Core Circadian Clock Gene Expression

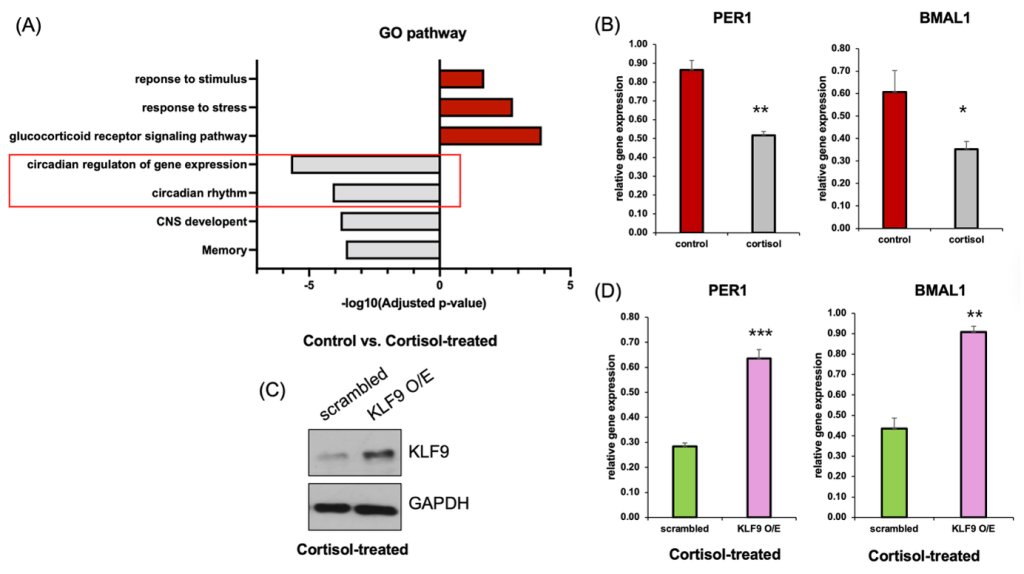

(B) qRT-PCR analysis showing reduced expression of core clock genes PER1 and BMAL1 following cortisol treatment compared to control (n=3).

(C) Western blot confirming overexpression of KLF9 in cortisol-treated cells.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis showing that overexpression of KLF9 significantly rescues PER1 and BMAL1 expression in cortisol-treated cells. (n=3). Data represent mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

To assess the functional consequences of transcriptional alterations under chronic cortisol exposure, we performed GO enrichment analysis using differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data (Figure 3A). Pathways related to stress signaling, such as “response to stress” and “glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway,” were upregulated, whereas circadian-related pathways—including “circadian rhythm” and “circadian regulation of gene expression”—were significantly downregulated.

qRT-PCR analysis was used to validate the repression of key circadian clock genes in cortisol-treated neurons. Specifically, expression of both PER1 and BMAL1 was significantly decreased in cortisol-treated cells compared to controls (Figure 3B). To determine whether this effect was causally mediated by KLF9, we overexpressed KLF9 in cortisol-treated cells. Western blot analysis confirmed robust upregulation of KLF9 in the overexpression group (Figure 3C), and importantly, qRT-PCR revealed that restoring KLF9 expression led to a significant increase in both PER1 and BMAL1 mRNA levels (Figure 3D).These results provide support the possibility that KLF9 appears to influence the expression of circadian genes in this model, as its overexpression partially increased PER1 and BMAL1 levels.

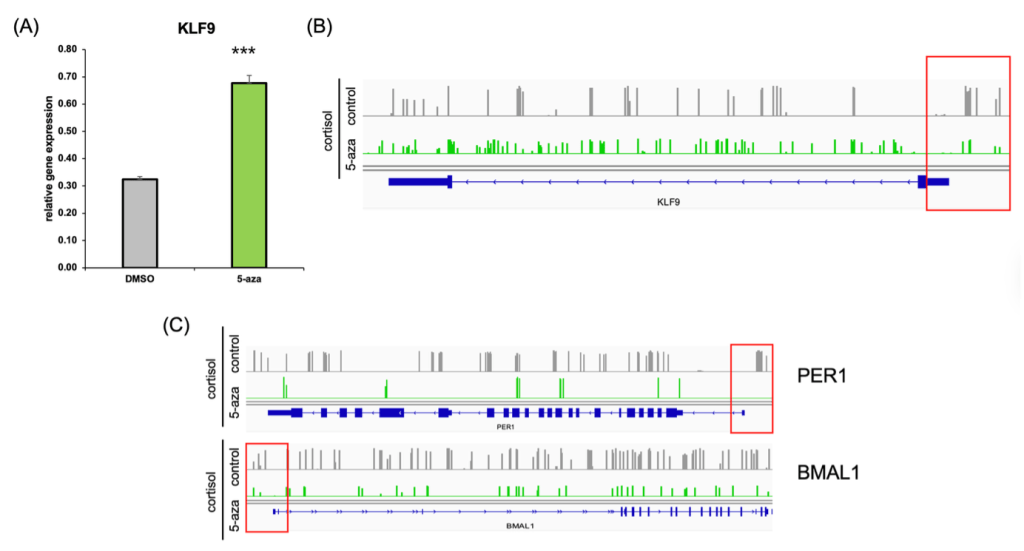

5-aza treatment partially increases KLF9 and circadian gene expression, consistent with reduced promoter-proximal methylation

(B) EM-seq gene track data showing reduced promoter methylation at the KLF9 locus following 5-aza treatment.

(C) EM-seq gene tracks illustrating decreased methylation in the promoter regions of circadian genes PER1 and BMAL1 after 5-aza treatment.

To test whether DNA methylation was responsible for KLF9 downregulation under chronic cortisol exposure, we treated cells with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza). 5-aza treatment partially increases KLF9 mRNA expression (Figure 4A), consistent with reduced promoter-proximal methylation, although its global demethylating effects cannot exclude indirect influences.

Genome browser tracks of EM-seq data further confirmed this finding (Figure 4B), revealing a marked decrease in methylation at the KLF9 promoter region in the 5-aza–treated group compared to cortisol-only cells.

Interestingly, we also observed a similar hypomethylation pattern in the promoter regions of the circadian clock genes PER1 and BMAL1 (Figure 4C), which had previously been downregulated under cortisol stress. These results suggest that 5-aza treatment is consistent with reduced promoter-proximal methylation at KLF9, PER1, and BMAL1 loci, accompanied by increased expression at the measured time point. It supports the hypothesis that epigenetic repression of the KLF9–circadian axis underlies the transcriptional disruption observed in in vitro cortisol-induced epigenetic model relevant to PTSD neuronal cells.

Discussion

Chronic psychological stress is one of the most prominent risk factors for the development of neuropsychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)17‘18. At the molecular level, stress exposure leads to sustained activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and prolonged secretion of glucocorticoids such as cortisol, which in turn alters transcriptional programs in stress-responsive brain regions.

In this study, we demonstrate that chronic cortisol exposure in a neuronal model leads to epigenetic repression of the transcription factor KLF9, a glucocorticoid-responsive gene implicated in circadian regulation and neuronal plasticity. We show that KLF9 expression is significantly decreased under cortisol treatment, accompanied by hypermethylation at its promoter region. Importantly, this repression could be reversed by treatment with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza, confirming that epigenetic silencing mediates KLF9 downregulation.

Moreover, our data indicate that reduced KLF9 expression co-occurs with decreased expression of core circadian clock genes, including PER1 and BMAL1, both of which showed promoter hypermethylation and reduced mRNA levels in cortisol-treated cells. Overexpression of KLF9 was sufficient to rescue PER1 and BMAL1 expression, supporting a regulatory role for KLF9 in maintaining circadian gene expression.

These findings support a hypothesis that chronic stress may contribute to epigenetic changes—including promoter-proximal hypermethylation—associated with reduced KLF9 expression, which may be related to altered circadian gene expression. This is associated with altered expression of circadian clock genes. However, because samples were collected at a single time point without entrainment, we cannot infer any effects on circadian rhythmicity or clock function. This model aligns with clinical observations linking circadian rhythm disruption with PTSD symptoms, including sleep disturbances, emotional dysregulation, and memory impairment19. However, circadian rhythm disturbances are frequently reported in individuals with PTSD, the observed changes in PER1 and BMAL1 in our model may parallel some aspects of stress-related transcriptional dysregulation, although further in vivo and clinical studies will be required to establish their translational relevance. Additionally, key limitation of this study is that all analyses were performed at a single time point without circadian entrainment. Therefore, although PER1 and BMAL1 expression levels were reduced in cortisol-treated neurons, our data cannot address circadian phase, amplitude, period, or rhythmicity. As such, we interpret these findings strictly as single-time-point changes in circadian gene expression, not as alterations of circadian clock function.

Collectively, our findings highlight an epigenetically regulated KLF9–circadian network that may serve as a conceptual starting point for future therapeutic exploration. However, these observations require extensive in vivo validation and should not be interpreted as clinically actionable at this stage. Future work will be needed to determine whether these findings extend in vivo and how they intersect with other epigenetic and neuroinflammatory pathways implicated in trauma-related neuropathology.

References

- Lancaster, C. L., Teeters, J. B., Gros, D. F., Back, S. E. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Overview of Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment. J Clin Med 5 (2016). [↩]

- Davis, L. L., Hamner, M. B. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the role of the amygdala and potential therapeutic interventions – a review. Frontiers in Psychiatry Volume 15 – 2024 (2024). [↩]

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., de Girolamo, G., Degenhardt, L., … Kessler, R. C. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med 47, 2260-2274 (2017). [↩]

- Gill, J. M., Page, G. G., Sharps, P., Campbell, J. C. Experiences of traumatic events and associations with PTSD and depression development in urban health care-seeking women. J Urban Health 85, 693-706 (2008). [↩]

- Kuch, K., Cox, B. J. Symptoms of PTSD in 124 survivors of the Holocaust. Am J Psychiatry 149, 337-340 (1992). [↩] [↩]

- Barak, Y., Szor, H. Lifelong posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from aging Holocaust survivors. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2, 57-62 (2000). [↩]

- Sherin, J. E., Nemeroff, C. B. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 13, 263-278 (2011). [↩]

- Krystal, J. H., Abdallah, C. G., Averill, L. A., Kelmendi, B., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Sanacora, G., Southwick, S. M., Duman, R. S. Synaptic Loss and the Pathophysiology of PTSD: Implications for Ketamine as a Prototype Novel Therapeutic. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19, 74 (2017). [↩]

- Addissouky, T. A., El Tantawy El Sayed, I., Wang, Y. Epigenetic factors in posttraumatic stress disorder resilience and susceptibility. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 26, 50 (2025). [↩]

- Zovkic, I., Meadows, J. P., Kaas, G. A., Sweatt, J. D. Interindividual Variability in Stress Susceptibility: A Role for Epigenetic Mechanisms in PTSD. Frontiers in Psychiatry Volume 4 – 2013 (2013). [↩]

- Gans, I. M., Grendler, J., Babich, R., Jayasundara, N., Coffman, J. A. Glucocorticoid-Responsive Transcription Factor Krüppel-Like Factor 9 Regulates fkbp5 and Metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 727037 (2021). [↩]

- Guo, N., McDermott, K. D., Shih, Y. T., Zanga, H., Ghosh, D., Herber, C., Meara, W. R., Coleman, J., Zagouras, A., Wong, L. P., Sadreyev, R., Gonçalves, J. T., Sahay, A. Transcriptional regulation of neural stem cell expansion in the adult hippocampus. eLife 11, e72195 (2022). [↩]

- Fagiani, F., Di Marino, D., Romagnoli, A., Travelli, C., Voltan, D., Di Cesare Mannelli, L., Racchi, M., Govoni, S., Lanni, C. Molecular regulations of circadian rhythm and implications for physiology and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7, 41 (2022). [↩]

- Akagi, R., Akatsu, Y., Fisch, K. M., Alvarez-Garcia, O., Teramura, T., Muramatsu, Y., Saito, M., Sasho, T., Su, A. I., Lotz, M. K. Dysregulated circadian rhythm pathway in human osteoarthritis: NR1D1 and BMAL1 suppression alters TGF-β signaling in chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 25, 943-951 (2017). [↩]

- Chen, Y., Pal, B., Visvader, J. E., Smyth, G. K. Differential methylation analysis of reduced representation bisulfite sequencing experiments using edgeR. F1000Res 6, 2055 (2017). [↩]

- Vaisvila, R., Ponnaluri, V. K. C., Sun, Z., Langhorst, B. W., Saleh, L., Guan, S., Dai, N., Campbell, M. A., Sexton, B. S., Marks, K., Samaranayake, M., Samuelson, J. C., Church, H. E., Tamanaha, E., Corrêa, I. R., Jr, Pradhan, S., Dimalanta, E. T., Evans, T. C., Jr, Williams, L., Davis, T. B. Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Genome Res 31, 1280-1289 (2021). [↩]

- Davis, M. T., Holmes, S. E., Pietrzak, R. H., Esterlis, I. Neurobiology of Chronic Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders: Evidence from Molecular Imaging Studies. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 1 (2017). [↩]

- Musazzi, L., Tornese, P., Sala, N., Popoli, M. What Acute Stress Protocols Can Tell Us About PTSD and Stress-Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology Volume 9 – 2018 (2018). [↩]

- Germain, A. Sleep Disturbances as the Hallmark of PTSD: Where Are We Now? American Journal of Psychiatry 170, 372-382, (2013). [↩]