Abstract

This paper examines the devaluation of the Indian currency with particular focus on the 1966 and 1991 episodes. The study reviews theoretical perspectives and empirical findings on devaluation, outlines research objectives, and applies a descriptive analysis of macroeconomic indicators before and after the policy changes. The results suggest that while devaluation improved export competitiveness and corrected trade imbalances, it also intensified inflationary pressures and worsened short-term social costs such as reduced real wages and income inequality. The paper concludes that devaluation can restore external balance, but its success depends heavily on complementary fiscal and monetary policies as well as measures to protect vulnerable groups.

Keywords: Devaluation; Indian currency; exchange rate; inflation; trade balance; economic impacts; social impacts; India 1966; India 1991

Introduction

Overview of Currency Devaluation

Beyond the economic impacts, devaluation has had significant social impacts. For instance, inflation following a devaluation disproportionately affects the poor and middle-income parts of society, whose limited savings and low wages are overwhelmed by the rising prices. Moreover, the increase in costs for imported goods such as food, energy, and medical supplies is likely to further worsen poverty, deepen income inequality, and reduce the access to essential services for the most vulnerable. In countries like Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey, devaluation has led to similar outcomes: inflation rates increased at uncontrollable rates, leading to reduced real wages, higher unemployment, and social unrest. These social consequences, including income inequality, unemployment, and public discontent, will be accounted for when analysing the effectiveness of devaluation as a policy tool in the Indian economy.

Global Experiences with Devaluation

Turning to international evidence, many countries have tried to address their economic problems through currency devaluations. However, the results have been of a mixed nature. For instance, the harsh economic crisis, which was realised between 1999 and 2002 in Argentina forced the government to delink from the fixed exchange rate system, consequently, the peso was devalued massively. Although it assisted in the righting of Argentina’s trade balance, it spurred inflation, unemployment and social instability which resulted in the collapse of successive regimes within a few years. The Argentine crisis is a prime example of the dangers of devaluation and the lack of proper social policies that would protect the poor to middle classes from rising inflation and the increasing prices of essential commodities.

In Brazil, the drive to devalue the local currency, the real, was initiated in 1999 to counter shocks of high inflation and capital flight. Initially after its implementation the move enhanced the export competitiveness of the country, but also contributed to very high inflation rates that adversely affected the poor. The inflation that followed Brazil’s devaluation increased the cost of living, exacerbated inequality, and led to widespread public protests. These cases demonstrate that without strong policies, devaluation can trigger severe social costs.

These international case studies offer valuable insight to how devaluation might affect India. Devaluation can be a useful tool for addressing economic crises, but it must be managed carefully to avoid long-term damage to the economy and society. Without strong policies to control inflation, reduce income inequality, and protect vulnerable populations, the benefits of devaluation may be outweighed by its social costs.

Likewise, Turkey recorded a significant decline of its currency in 2018 reducing the lira to dollar value by about 30 percent. This process initiated by political instability and pressure from foreign debt led to even higher inflation rate, growing unemployment and increased social tension. Note, this was not a deliberate policy-driven devaluation but a market-driven depreciation triggered by political instability and foreign debt pressures. Nevertheless, it produced impacts similar to deliberate devaluations, including inflation, unemployment, and social unrest. Among the economic crises, the continuous high inflation rate with increasing prices of basic necessities like food, fuel and medicine worsened the situation of the poor in the society and poverty and economic inequality aggravated in Turkey.

India’s Devaluation Experiences

Focusing now on India, two major events shaped its devaluation experience: the 1966 devaluation and the economic reforms of 1991. Due to a growing trade deficit and a foreign exchange crisis, the rupee saw a 57% devaluation in 1966. India devalued its currency in response to pressure from foreign lenders like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), hoping that this would assist to boost exports and ease the nation’s escalating economic issues. While some of these goals did end up being achieved, the economic decision also led to high levels of inflation, social unrest, job losses, and political instability. In an attempt to boost exports and stabilise the economy, a currency devaluation was implemented. The devaluation did, however, result in inflation, increased import costs, and considerable social dissatisfaction in addition to improving the trade balance. The increased prices caused much struggle for many Indian firms, especially those dependent on imported commodities, which resulted in job losses and a drop in industrial production. Politically, the devaluation was extremely unpopular and played a part in the Congress Party’s defeat in the elections that followed.

In 1991, devaluation occurred as a part of a structural adjustment program whose aim was to be able to stabilise the Indian economy during an impending financial collapse. This happened when India had dwindling foreign reserves and was on the path to defaulting on foreign debt. By devaluing the rupee by 19.5%, India tried to avoid such a path. While this move, in tandem with economic liberalisation, was the cornerstone for India’s future economic growth and helped stabilise the economy, attract foreign investment, and set the stage for India’s rapid economic growth in the decades that followed, it also brought severe challenges. Inflation rates went up drastically, the cost of imports rose, and foreign debt obligations grew in burden as they were mainly dealt with in USD. However, notably unlike what happened in 1966, India’s 1991 devaluation is seen to be part of the larger liberalisation reforms that were responsible for it to become a globally competitive economy.

Theoretical Frameworks of Devaluation

Building on this overview, many economic theories seek to explain how devaluation operates and what its possible effects are. The most important one is the Marshall-Lerner Condition according to which devaluation is only beneficial for a nation’s trade balance if the combined price elasticity of demand for imports and demand for exports is greater than 1. This theory suggests for devaluation to positively impact the trade balance, the decrease in imports (in terms of quantity) should outweigh the increase in export volume, leading to an overall improvement in the trade balance. If the combined elasticity is less than or equal to 1, the devaluation may not lead to a favourable outcome for the trade balance.

The J-Curve Effect is another important theory that needs to be discussed when investigating devaluation’s effect on India. It argues that after devaluation, a country’s trade balance will first deteriorate because the increase in import costs is faster than the increase in export earnings because export quantities take some time to respond to changes in prices. In the longer run, positive trends will be observed in the trade balance by growth of export volumes.

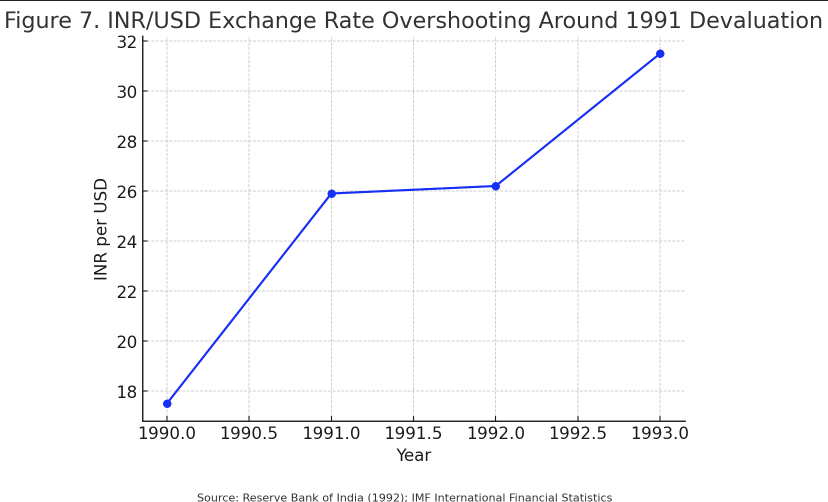

The Dornbusch Overshooting Model describes how monetary policy adjustments, in particular, can cause currency rates to overshoot their long-term equilibrium after economic shocks. According to this paradigm, prices for products and services fluctuate slowly while financial markets react swiftly. Investors may transfer money overseas in response to a monetary shock, such as an increase in the money supply, which lowers interest rates and produces a significant depreciation of the home currency. Because financial markets adjust more quickly than actual prices, this depreciation frequently overshoots. Eventually, the exchange rate finds equilibrium when prices catch up with inflation. This helps explain why currencies may overshoot their equilibrium after devaluation, especially in emerging economies like India where volatile capital flows amplify market reactions.

Research Objectives

Finally, this paper examines the economic and social effects of currency devaluation in India through historical case studies, empirical data, and international comparisons. It will specifically look at how devaluation impacts important economic factors such as GDP growth, inflation, trade balances, and foreign debt. The social ramifications of devaluation will also be covered in this paper, including how it affects employment, economic inequality, public services, and political stability.

This study will use both qualitative and quantitative research approaches to accomplish these goals. The qualitative analysis reviews theoretical and empirical research on devaluation alongside case studies from India and other developing nations. The quantitative analysis uses data from India’s 1966 and 1991 devaluations and estimates import-export elasticities to evaluate the impacts of devaluation.

Literature Review

Theories of Devaluation and Theoretical Economic Growth

The Marshall–Lerner Condition

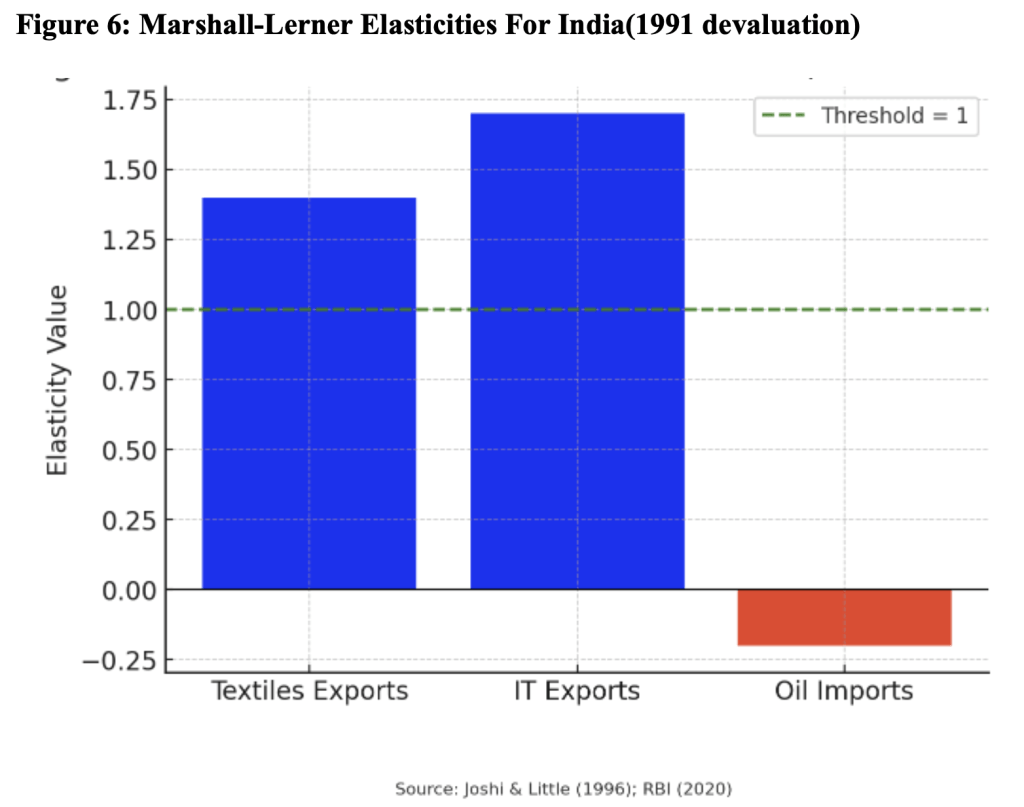

Currency devaluation initially was seen as a tool which could enhance export competitiveness and correct trade imbalances. Marshall and Lerner provided the foundational basis for understanding how devaluation could improve the trade balance through the Marshall-Lerner Condition1. However, later scholars such as Krugman and Taylor (1978) argued that this optimism may be misplaced, as devaluation can be contractionary in the short run by raising import costs and reducing real wages, which shows the divide in how economists view the condition’s reliability. This condition often fails in developing countries like India, where imports such as crude oil, machinery and medical supplies are inelastic2. The Reserve Bank of India estimates that the price elasticity of oil imports is approximately -0.2, indicating that devaluation has a limited effect on reducing oil demand2. On the other hand, India’s export goods, particularly in IT and textiles, demonstrate higher price elasticities, making them more responsive to devaluation. Joshi and Little (1996) estimated that the price elasticity of India’s textile exports was about 1.4 and IT services between 1.2 and 1.7, meaning a 1% fall in export prices led to a more than proportional rise in export volumes. This indicates that devaluation strongly boosted export growth in these sectors compared with the pre-1991 trend, when export growth was far more modest3.

The Dornbusch Overshooting Model

The Dornbusch Overshooting Model, which shows how exchange rates can momentarily over-adjust or ‘overshoot’ their long-term equilibrium in reaction to economic shocks, notably changes in monetary policy, is another important theoretical model4. This model states that while prices in the markets for goods and services vary more slowly, financial markets respond more quickly to changes, such as changes in interest rates. Investors flee to other countries in quest of greater profits if a country experiences an economic shock, such as a devaluation or an increase in the money supply, which causes the home currency to sharply depreciate. Nevertheless, this depreciation is usually temporary; as domestic prices and wages adjust and capital flows stabilise, the exchange rate drifts back toward its long-run equilibrium, confirming Dornbusch’s core prediction of overshooting dynamics.

The Dornbusch Overshooting Model was especially applicable to India in the wake of the 1991 currency crisis5. India had to weaken the rupee as part of its wider economic reforms due to serious balance of payments issues6. But short-term overshooting occurred because of speculative capital flows and investor reactions to the crisis, which made the rupee depreciate well beyond its long-term equilibrium value since financial markets react more quickly than the overall economy. The currency eventually finds its stable equilibrium again as real economy prices and inflation steadily adjust over time. The model highlights how currency volatility can be driven by speculative capital flows and short-term investor reactions, which go beyond the predictions of conventional economic models, more than anticipated. According to Srinivasan and Tendulkar7, investor pessimism and economic uncertainty exacerbated the rupee’s steep depreciation during this period, which was mostly caused by this overshooting. The depreciation that followed increased inflationary pressures and made India’s economic recovery even more difficult3, The overshooting impact highlighted how crucial it is to control capital flows and investor expectations during devaluation periods since speculative movements might produce more volatility than initially projected, which can result in extended economic instability.

Dornbusch Overshooting Equation

Eₜ = (E* +) λ (Mₜ − M*)

The Dornbusch overshooting model formalises this process as Et = E+ λ (Mt – M^), where the short-run exchange rate deviates from its long-run equilibrium in response to monetary shocks. In India’s 1991 crisis, the rupee depreciated by 19.5% in July while reserves fell to just $1.2 billion, covering only three weeks of imports. Investor panic and speculative outflows drove the currency below its long-run equilibrium value, illustrating overshooting. As IMF support and reforms took hold, the rupee stabilised closer to fundamentals. Thus, the 1991 devaluation was not only a response to a balance of payments crisis but also a textbook case of exchange rate overshooting.

As can be seen in figure 7, the rupee depreciated sharply from ₹17.5 per USD in 1990 to ₹25.9 in 1991, before stabilising near ₹26–31 in the following years. This pattern illustrates Dornbusch’s overshooting: a rapid depreciation overshooting equilibrium, followed by partial correction as reforms and IMF support restored stability.

The J-Curve Effect

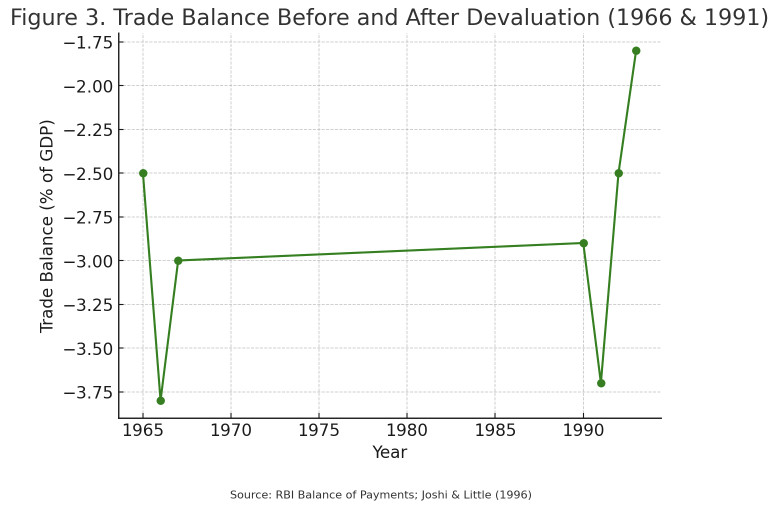

The J-Curve Effect is another foundational theory explaining trade dynamics after devaluation. It posits that a country’s trade balance often deteriorates immediately after devaluation because import costs rise instantly, while export quantities take longer to adjust. Over the medium term, however, exports expand and the trade balance improves8. This framework aligns with India’s experiences in 1966 and 1991, where trade deficits initially widened but later improved as exports became more competitive3, Researchers differ on how consistently the J-Curve applies: while some view it as a universal sequence, others argue its strength depends on trade structure and external demand. For India, the evidence suggests partial support, the J-Curve is visible in trade data, but heavy dependence on oil imports slowed adjustment compared to the textbook prediction. More recent experiences, such as Turkey’s 2018 currency depreciation, also reflected a J-Curve pattern where initial trade deficits deepened before later export gains began to emerge9.

Empirical Studies on Devaluation

Empirical studies on devaluation in developing economies, particularly India, present mixed outcomes. Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza (2003) found evidence that devaluation can be expansionary in the long run, but Edwards (1989) and Krugman and Taylor (1978) emphasised that the short-term effects are often contractionary through higher inflation and lower purchasing power. This inconsistency highlights that devaluation outcomes are highly context-specific rather than universally predictable. In both the 1966 and 1991 devaluations, the short-term benefits of devaluation on exports were offset by significant inflationary pressures10. On the other hand, India’s export goods, particularly in IT and textiles, demonstrate higher price elasticities, making them more responsive to devaluation. Joshi and Little estimated that the price elasticity of India’s textile exports was about 1.4 and IT services between 1.2 and 1.7, meaning a 1% fall in export prices led to a more than proportional rise in export volumes. This indicates that devaluation strongly boosted export growth in these sectors compared with the pre-1991 trend, when export growth was far more modest.3.

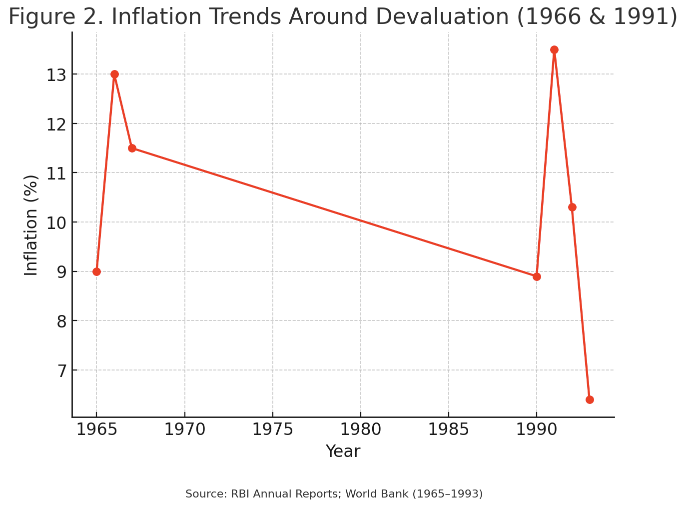

Further analysis by Artatrana Ratha using an error-correction model highlighted the short- and long-term impacts of the 1991 devaluation11. While India’s trade balance improved in the long run, consumer price inflation rose by 12% in the year following the devaluation11. This dual effect of boosting exports while inflating import prices illustrates the delicate balance policymakers must navigate when considering devaluation strategies12.

The J-Curve Effect, which suggests that a country’s trade balance initially worsens following devaluation before improving, is also applicable to India8. Both the 1966 and 1991 devaluations followed this pattern, with initial trade deficits widening before export growth outpaced rising import costs. Joshi and Little found that while the 1991 devaluation initially caused India’s trade deficit to widen by nearly 2% of GDP, the trade balance improved significantly by 19933, after the devaluation on two separate occasions, one in 1966 and the other in 1991, initially there has been a deteriorating effect on the trade balance, but in the long run it had a positive effect on export13. However, the short-run economic disruption caused by the rising costs of imports and inflation usually causes significant challenges, including political instability and social discontent14.

Elasticities and Trade Balance

The Marshall-Lerner Condition states that the demand elasticities for imports and exports determine how effective currency devaluation will be1. According to this criterion, if the total of these elasticities is more than one, devaluation will enhance the trade balance. According to empirical data, India’s export industries, textiles and IT, for example, have elasticity values of 1.4 and 1.7, respectively, making them more price-responsive than imports of necessities like oil, whose elasticity is substantially lower at -0.22.;3, this sector-specific discrepancy emphasises how little devaluation can do to cut oil imports, which account for a large amount of India’s trade deficit.

When a currency undergoes real devaluation, it means that inflation is taken into consideration and the real exchange rate is adjusted instead of merely the nominal value15, A devaluation must lead to real devaluation, in which the domestic currency drops in value relative to other currencies even after accounting for variations in price levels, to significantly increase a nation’s competitiveness. Real devaluation has been essential in India’s situation to improve export performance, especially during the devaluation in 19913, however, the Reserve Bank of India (2020) highlighted that India’s heavy dependence on oil imports with highly inelastic demand reduces the effectiveness of devaluation, showing that theoretical elasticity conditions may not fully apply to India’s import structure. Furthermore, while nominal devaluation can momentarily boost export competitiveness, Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza contend that actual devaluation must be sustained to yield long-term gains15, they found that real devaluation improved India’s trade balance in the long run, particularly in price-sensitive sectors like textiles and IT services, where export volumes responded positively to the changes in the real exchange rate15.

The J-Curve Effect is another important empirical finding in the context of India’s devaluations8. According to the J-Curve hypothesis, the trade balance initially worsens following devaluation because import prices rise more quickly than export volumes can adjust. In India’s case, both the 1966 and 1991 devaluations followed this pattern. As documented by Joshi and Little, the 1991 devaluation caused the trade deficit to widen by nearly 2% of GDP in the first year, before export growth caught up in subsequent years3. By 1993, India’s export growth had outpaced import costs, resulting in a gradual improvement in the trade balance.

Capital Flight

Capital flight is one of the main hazards associated with currency devaluation, especially in emerging economies like India16. A significant drop in a country’s currency value frequently indicates economic instability, which causes international investors to remove their money and move it to safer investment locations17. This tendency causes financial markets to get disrupted, undercuts the intended economic gains of devaluation, and leads to an increase in interest rates18.

In the case of India, the 1991 devaluation triggered significant capital flight. Foreign investors, wary of the declining rupee and India’s broader economic challenges, began pulling their capital out of Indian markets19. This exodus worsened the country’s already precarious balance of payments situation, forcing the Indian government to seek a bailout from the International Monetary Fund to stabilise its economy19. While trade-based models often focus on the benefits of devaluation for export competitiveness, the capital flight literature (Edwards, 1989; Pastor, 1990) shows that financial instability can entirely offset these gains, a factor that has not been fully emphasised in studies of India’s 1991 crisis. Furthermore, devaluation should theoretically increase economic growth by boosting exports, however the reality of capital flight can offset these gains, particularly in economies with fragile financial systems20.

Foreign Debt and Devaluation

India’s foreign debt has a big impact on its economy, especially when it comes to currency devaluation. According to the Department of Economic Affairs, 69.3% of India’s total debt is held in foreign currencies, leaving the nation extremely susceptible to exchange rate changes21. The local currency value of repayments of foreign debt increases when the rupee depreciates, adding to the burden on the public and private sectors’ finances22. According to current data, a substantial amount of India’s total debt is made up of external debt. India’s external debt was estimated by the Ministry of Finance to be at $558 billion, or almost 20% of the country’s GDP21. Because the majority of this foreign debt is in US dollars, the nation is subject to exchange rate risk. When the rupee depreciates against the dollar, the cost of servicing these debts in local currency terms increases substantially, diverting financial resources from domestic investments and social programs23.

India’s large percentage of foreign debt makes it more vulnerable to the consequences of devaluation. For example, a significant portion of India’s foreign debt was in US dollars during the 1991 economic crisis, and the depreciation of the rupee raised the cost of servicing this debt, restricting the government’s capacity to invest in vital industries10. India’s reliance on foreign loans for infrastructure and development projects made the issue worse, meaning that growing debt costs affected many different areas of the economy10.

Pass-Through Effects

In addition, according to Magee, the process of currency devaluations is associated with the issue of incomplete pass-through effects8. This implies that even though devaluation may lower the price of Indian goods in the foreign markets, the reduction may not be passed through to consumers due to sticky prices, currency contracts and hedging24. Recent evidence from Turkey’s 2018 currency crisis demonstrates that incomplete pass-through continues to amplify inflation, proving that this theoretical issue remains a practical concern in modern economies. Thus, the expected export increase might be less than expected, which makes devaluation a less potent instrument of policy12. More recent evidence shows that incomplete pass-through remains a major issue today. During Turkey’s 2018 currency crisis, inflation surged to over 25% despite policy tightening, largely because higher import costs were only partially transmitted to domestic prices25. Similarly, Argentina’s 2001–2002 peso collapse triggered soaring consumer prices as the benefits of cheaper exports were outweighed by rising import costs26. These cases highlight that pass-through effects are still central to understanding the inflationary consequences of devaluation.

Basic Pass-Through Model

πₜ = α ΔEₜ + β Zₜ

In India, a ~19.5% depreciation led to ~13.5% inflation—implying a high pass-through coefficient (α). This aligns with recent observations in Turkey in 201827 and confirms the inflation transmission mechanism.

Real Wages, Inflation, and Cost of Living

Devaluation has the effect of inflation because imported goods become expensive and in the process affecting the prices of other goods and services. Krugman and Taylor28 pointed out that, although devaluation makes exports cheaper, it also makes imports expensive and thus the cost of living rises eroding the real wages and thus the real income of the poor.

In Brazil, the episodes of devaluation that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s led to the hyperinflation that affected the living costs. According to Amann and Baer29, inflation reduced the purchasing power of people, especially the poor and the middle-income earners, hence increasing poverty and economic instability. Like Frankel30 also noted, in emerging economies such as Brazil and Argentina the inflationary effect of devaluation, which at times may offset the gains since the price of basic needs such as food and fuel sky-rocketed and these affects the most vulnerable in the society.

In India, the inflationary effect of devaluation is a matter of concern due to its large import dependence especially for essential items like crude oil and electronics. Historical data from India’s 1991 devaluation illustrates this point: inflation rose and impacted the real income of consumers and the burden on consumers was raised more especially on the low income earners19. Ghosh and Rajan31 have pointed out that inflation is like a regressive tax in developing countries which further leads to income disparity and social tension.

Employment and Wages

In Turkey, the devaluation of lira in the later part of the 2010s increased unemployment and reduced the real wages because of increased cost of imported goods. Akyüz and Boratav32 observed that the Turkish experience revealed the fact that industries dependent on imported inputs are highly sensitive to shocks and this in turn has implications for employment and wages. Likewise, Domac33 observed that in Mexico the peso crisis resulted in a high unemployment rate, especially in manufacturing industries that relied on imported machinery and parts.

The same risks are associated with devaluation for India. Some industries such as automotive, electronics, and pharmaceutical industries whose inputs are imported may experience high production costs, layoffs, and low employment security34. On the other hand, sectors that rely more on exports, for instance textile and IT services, could possibly see an improvement in the short-term3, However, Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza pointed out that the net impact is typically negative when inflationary pressure decreases overall domestic demand15.

Income Inequality and Poverty

There was a rise in the general cost of living and hence the poor are made poorer as was seen in Argentina during the early 2000’s peso devaluation. Galiani, Heymann, and Tommasi35 described how devaluation resulted in a poverty increase of between 5 and 16 percent(based on poverty headcount ratio) and an increase in the income gap due to a decrease in real wages and an increase in unemployment. Thus, income inequality is a real possibility in India in case of devaluation3. However, while Argentina’s 2001 devaluation led to hyperinflation and social unrest36, India’s 1991 episode, though painful, avoided total collapse. This comparison suggests that strong institutions and cautious macroeconomic management can limit the worst-case outcomes of devaluation. The 1991 devaluation also shows an example where inflation was higher than wage increase and as a result, real income of the lower and middle income earners went down. Datt and Ravallion37 noted that while reforms such as devaluation helped increase overall economic growth, the poor in both rural and urban areas were most affected by inflationary pressures. According to the literature, social safety nets in India have not been targeted towards the poor and the devaluation is likely to worsen the situation by increasing inequality and reducing poverty26.

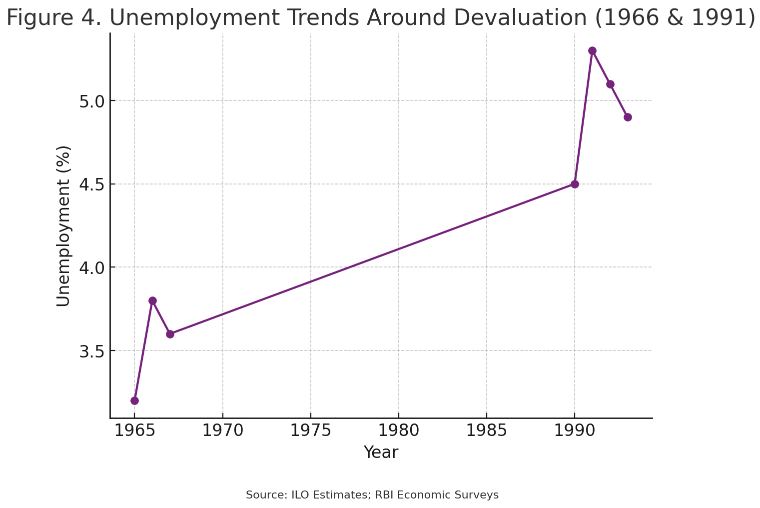

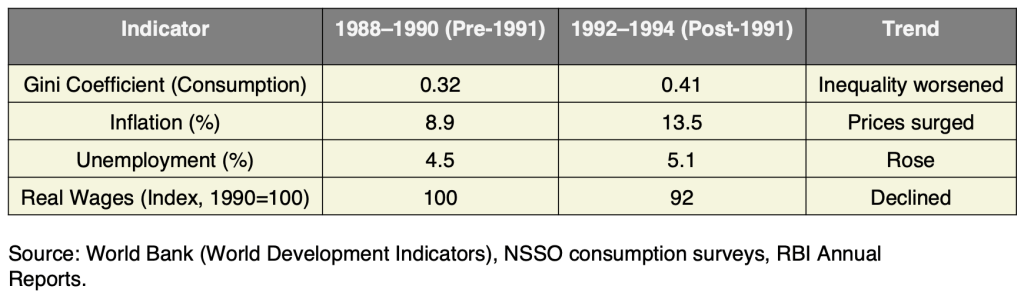

Between 1988–1990 and 1992–1994, India’s Gini coefficient rose from about 0.32 to 0.41. This worsening inequality coincided with a sharp rise in inflation (from 8.9% to 13.5%), higher unemployment (from 4.5% to 5.1%), and a fall in real wages (index down from 100 to 92). These shifts occurred directly in the aftermath of the 1991 devaluation, suggesting that currency depreciation amplified inequality by eroding real wages and raising living costs. However, notably, broader liberalisation reforms were also underway during this period, meaning devaluation was not the sole driver. Still, the timing and correlation across multiple indicators provide evidence that devaluation was a significant causal factor in worsening income inequality in early-1990s India.

Methodology

This paper follows a mixed-methods descriptive approach that combines both qualitative and quantitative techniques. The qualitative side is based on a review of existing literature and theories on devaluation, while the quantitative side uses empirical data from India’s 1966 and 1991 devaluations, together with selected international case studies.

Data Collection

The data for India’s devaluations in 1966 and 1991 has been taken from reliable secondary sources, mainly the Reserve Bank of India Annual Reports, the Ministry of Finance’s Economic Surveys, and international datasets such as the World Bank’s World Development Indicators and the IMF statistical bulletins. The variables collected include GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, foreign debt, and employment, which allow us to assess both short-term disruptions and long-term effects of devaluation.

Data Analysis

The study uses a descriptive and comparative method of analysis. For India, the collected data is compared across pre- and post-devaluation years to highlight the immediate impact as well as the recovery path. Graphs and charts are used to present changes in GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, and trade balance (Figures 1–5), which makes the patterns clearer. To add analytical depth, well-known economic models such as the Marshall–Lerner Condition, the Dornbusch Overshooting Model, and the Pass-Through Effect are applied to the Indian case. Instead of running econometric regressions, which are beyond the scope of this paper, the study relies on descriptive statistics and visualisations to explain the findings.

International Case Studies

The paper also includes case studies of Brazil (1999), Argentina (2001), and Turkey (2018). These cases were selected because they represent similar emerging economies that faced major devaluations, but in many cases experienced worse outcomes such as hyperinflation, social unrest, and political collapse. They provide useful comparisons with India, where devaluation also had serious effects but did not spiral into total crisis. This helps to underline the importance of institutional factors and policy responses in shaping outcomes.

Methodological Limitations

The study is limited by its reliance on secondary data, which may carry reporting inconsistencies. In addition, the analysis is descriptive and does not use advanced econometric testing, which restricts the ability to prove causation. However, by bringing together theory, India’s historical experience, and international comparisons, the study still offers a structured and reliable understanding of the effects of devaluation. Future research could expand on this by applying econometric models or using more recent micro-level datasets.

Analytical Framework

This study follows a structured framework to analyze the economic and social impacts of currency devaluation in India. First, it examines theoretical models such as the Marshall–Lerner Condition, the J-Curve Effect, and the Dornbusch Overshooting Model to establish the foundational concepts. Second, it conducts a descriptive analysis of India’s two major devaluations in 1966 and 1991, using historical data on GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, foreign debt, and employment trends from sources including the Reserve Bank of India, the Ministry of Finance, and the World Bank. Third, these findings are compared with international case studies from Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey to identify similarities and differences in outcomes. Finally, the study synthesizes insights from theory, data, and comparative evidence to evaluate the short- and long-term consequences of devaluation. This structured approach allows for the results to be grounded in both empirical evidence and established economic theory, even though the analysis is descriptive rather than statistical.

Economic Impacts

Debt and Devaluation

An Overview of Debt and Devaluation in India

The amount of foreign debt India has greatly influences how its economy responds to currency devaluation. Even though devaluation is commonly seen as a tool for policymakers to boost export competitiveness, it actually has substantial ramifications for countries with significant debt denominated in foreign currencies because it increases the cost of debt servicing dramatically in home currency22. India’s external debt was estimated by the Ministry of Finance to be $558 billion as of 2020, or about 20% of GDP, with a sizable portion held in US currency21. Because of its heavy reliance on foreign borrowing, India is particularly susceptible to fluctuations in exchange rates, which can have a substantial impact on government finances, development programs, and overall economic stability.

Impact on Developmental Projects

A significant effect of growing debt-servicing expenses after devaluation is the removal of funds from vital development initiatives. The government must set aside more money to pay down its debt as the value of its foreign debt in local currency rises, which reduces the amount of money available for programs aimed at reducing poverty, promoting healthcare, education, and infrastructure10. Das and Pant10 emphasise that the devaluation of 1991 made this problem much more severe because it further reduced India’s already limited fiscal flexibility by increasing the cost of servicing its foreign debt. Nearly half of India’s external debt in 1991 was in foreign currencies, mostly US dollars, due to foreign creditors. The swift depreciation of the rupee led to an increase in the debt’s value denominated in rupees, compelling the government to curtail public investment in key sectors.

Infrastructure development, in particular, suffers when debt repayment takes precedence over investment. For example, the absence of funds may cause important projects like the development of roads and railroads, rural electrification, and enhancements to urban infrastructure to be postponed or cancelled. To reach its growth ambitions, India must invest about 8 % of its GDP yearly in infrastructure, according to data from the World Bank23. However, due to growing loan costs because of devaluation, this level of investment is challenging to maintain.

Furthermore, the government’s capacity to borrow additional funds for development projects is restricted by the debt overhang. Credit rating agencies may lower a nation’s sovereign debt rating, raising the cost of borrowing in the future, if a sizable amount of national income is spent on debt servicing. This situation creates a vicious cycle whereby debt repayment discourages investment, which impedes economic growth and makes it more challenging for the nation to produce the income required to pay off its debts38. According to Frankel30, this cycle can be especially harmful for developing economies, because continued investment is essential for long-term development and the eradication of poverty.

Investor Confidence and the Impact of Devaluation

The impact of devaluation on investor confidence is a significant additional worry. A nation’s devaluation of its currency indicates to investors, both local and foreign, that the economy might be fragile. Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza15, point out that devaluation frequently causes investors to flee their money in search of safer investment opportunities. Following the 1991 devaluation, foreign investment in India rapidly declined as investors around the world lost faith in the soundness of the nation’s economy.

By lowering domestic economy liquidity and depleting foreign exchange reserves, this capital flight exacerbates already severe economic problems. According to the Reserve Bank of India19, investors withdrew their money from Indian markets, causing India’s foreign exchange reserves to drop to barely $1.2 billion in 1991—roughly a few weeks’ worth of imports. Investor confidence was further damaged by the central bank’s inability to act in currency markets to stabilise the rupee because of this sharp fall in reserves.

Given the current circumstances, another significant devaluation could result in a replay of the 1991 event due to India’s high amounts of foreign debt and investor sensitivity to currency changes. Ratha39, cautions that India is still susceptible to abrupt capital outflows in the absence of sufficient foreign exchange reserves and robust investor protections. Maintaining macroeconomic stability and open lines of communication with investors to control expectations and reassure them of the government’s capacity to handle economic shocks are crucial to reducing this risk.

Future Crisis Management and Policy Implications

In future crises, devaluation will further constrain India’s fiscal flexibility, limiting its ability to provide stimulus or welfare support. This highlights the importance of debt management reforms. The requirement for effective debt management is consequently crucial. According to Frankel30 emerging nations like India should work to promote domestic savings and expand their local capital markets to lessen their need for debt denominated in foreign currencies. India can protect itself from the worst consequences of devaluation and other external shocks by lowering the percentage of debt due to foreign creditors.

Furthermore, Das and Pant10 make the case for more focused debt relief programs in an effort to lessen the effects of growing debt servicing expenses. This can entail negotiating a debt restructuring with foreign creditors or looking for concessional loans that have lower interest rates. India might have more money available for crisis management and development initiatives if its total debt load was reduced.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Devaluation

Introduction: The Role of FDI in India’s Economic Growth

India’s economic growth has traditionally been significantly influenced by foreign direct investment (FDI). Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is a vital component of economic development and productivity enhancement since it provides funding for infrastructure, technology transfer, and job creation. Currency devaluation, however, offers FDI inflows both advantages and disadvantages. Devaluation can lower the cost of local assets for foreign investors, but it also creates questions about the stability of the economy, which may eventually discourage investment.

Opportunities Created by Devaluation for FDI

Making local assets more affordable in terms of foreign currencies is one of devaluation’s main benefits for overseas investors. Foreign investors now have more purchasing power and can buy Indian assets for less money as a result. Devaluation, according to Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza (2003), can draw foreign direct investment (FDI), especially in industries like manufacturing, infrastructure, and real estate where asset prices are immediately impacted by changes in exchange rates.

Foreign investors flocked to India after the devaluation of 1991, taking advantage of the weaker rupee to purchase assets at a reduced price. In the two years that followed the devaluation, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows rose by nearly 400%, according to the Reserve Bank of India19, especially in industries like consumer products, software services, and telecommunications. This foreign capital infusion helped to stabilise the Indian economy in the wake of the balance of payments crisis by supplying much-needed liquidity to the country’s markets.

In the setting of today, the same dynamic applies. Foreign investors may find Indian assets more appealing as the rupee swings, particularly in capital-intensive industries like manufacturing and infrastructure. In 2022, India brought in approximately $49 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI), slightly down from $64 billion in 2021, with major inflows directed towards services, manufacturing, and IT40. A decline in the value of the rupee could encourage these investments even more by lowering the cost of entry for foreign companies looking to enter the Indian market.

Risks and Investor Sentiment Post-Devaluation

Devaluation involves substantial dangers, especially when it indicates economic instability, but it can also present chances for international investment. Investors who are worried about the long-term stability of the Indian economy may be discouraged by a significant depreciation. According to Aizenman and Noy41, even if FDI inflows may rise immediately following a devaluation, investor confidence can eventually weaken if the devaluation signals deeper economic issues.

In the case of India, investor sentiment is intimately connected to perceptions of macroeconomic stability. A good example is the devaluation that occurred in 1991. Although foreign direct investment (FDI) increased significantly in the years that followed the devaluation, investors first reacted cautiously because of worries about India’s long-term growth prospects. Ratha39, emphasises that foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows are extremely susceptible to changes in the exchange rate and the overall state of the economy, especially in high-risk industries like manufacturing. If investors believe that a devaluation is a sign of more serious structural issues, including excessive inflation or unmanageable budget deficits, they may pull their investments.

Devaluation raises the price of imported capital goods, which are necessary for many FDI projects in industries like manufacturing and infrastructure, adding to the risk. Joshi and Little3, point out that increased input costs have the potential to reduce FDI project profitability, especially in industries that depend significantly on imported raw materials and machinery. In this situation, international investors can be hesitant to fund long-term initiatives if they think that currency fluctuations will reduce the returns on their capital.

Figure 1 depicts the trends in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in India over time, especially in the context of currency devaluation. It shows a correlation between the depreciation of the rupee and fluctuations in FDI inflows. Following periods of devaluation, there is often an initial surge in FDI, as the weaker rupee makes Indian assets more attractive to foreign investors. This trend is highlighted in the graph, with FDI levels rising in the years immediately after devaluation events.

However, the graph also illustrates a subsequent levelling off or decline in FDI over the longer term. This can be attributed to factors such as investor concerns about economic instability and inflationary pressures that typically follow devaluation. While the devaluation lowers the cost of entry for foreign investors, the associated risks, such as rising inflation and the increased cost of imported goods and services, may dampen investor confidence, leading to a reduction in long-term investments. It is also important to note that there first a decline in FDI due to a decrease in investor confidence before investors started investing again post 2005 provided the Indian government was able to prove stability and the relatively attractive prices due to devaluation still lingered.

Long-Term Impact on Investor Confidence

Long-term currency volatility has the potential to undermine investor confidence and decrease foreign direct investment inflows. Foreign investors may find it more challenging to project future returns when exchange rates fluctuate, especially in industries with lengthy gestation periods like real estate and infrastructure. According to Frankel30 currency fluctuation raises doubts about future profitability, which may deter international investors from investing in India.

The Indian government must put policies in place that support macroeconomic stability and reassure investors of the nation’s capacity for long-term growth to reduce this risk. According to Aizenman and Noy41,retaining investor confidence in the face of currency devaluation requires cautious fiscal management, solid inflation targeting, and open communication with investors. Even during times of currency fluctuation, India may draw foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows by fostering a stable macroeconomic environment.

Policy Implications for Managing FDI Post-Devaluation

Following a devaluation, officials should make sure that foreign investment is going to areas that support sustained economic growth to optimise the benefits of FDI. According to Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza15, the secret to maximising FDI is to make sure that it goes into industries that are productive and can boost economic development, like manufacturing, infrastructure, and technology.

The government should also concentrate on lowering obstacles to investment, such as unreliable regulations, long bureaucracy, and poor infrastructure. Enhancing company accessibility is essential for drawing foreign direct investment (FDI), according to Ratha39, especially in a post-devaluation setting when investor sentiment may be wary. India can make the country a more desirable place for international companies to invest by cutting red tape and simplifying approval procedures.

Elasticities and Devaluation

Introduction to Price Elasticities and Trade Balance in India

The price elasticity of imports and exports in India varies greatly per industry. Because the demand for necessities like machinery and crude oil is comparatively inelastic, changes in price have minimal impact on the amount of imports. However, because export industries like textiles and IT services are more sensitive to price changes, devaluation can result in a notable rise in export volumes. It is essential to comprehend these elasticities to evaluate the whole effect of devaluation on India’s trade balance considering the Marshall-Lerner Condition.

Elasticities in Indian Exports and Imports

Software, IT services, textiles, and other labour-intensive industries typically have higher price elasticity of demand for Indian exports. According to Joshi and Little3, there is a 1.4 % rise in export volumes for every 1% decrease in export prices for Indian textile exports, or a price elasticity of demand of about 1.4. Similar to this, the price elasticity of the IT services industry, which has grown to be one of India’s biggest export earners, is high, with estimates varying from 1.2 to 1.7, depending on the particular service provided. The Marshall-Lerner Condition suggests that devaluation will only improve the trade balance if the combined elasticities of demand for exports and imports exceed one. However, in India this rarely holds in the short term, since imports like oil are highly inelastic2;15,

However, devaluation’s ability to close the trade imbalance is limited by India’s reliance on imports for essential commodities like machinery and crude oil. According to the Reserve Bank of India42 forecasts, even considerable price rises won’t considerably lower import quantities because the price elasticity of demand for oil imports is approximately -0.2. This is especially worrying because crude oil makes up over 25% of India’s entire import expenditure. India’s trade balance may potentially get worse in the short run when oil prices rise in reaction to devaluation since the benefits of increased export volumes are outweighed by the increase in import costs.

The J-Curve Effect and Short-Term Trade Balance Deterioration

As discussed in Section 2.1, the J-Curve Effect helps explain why India’s 1991 devaluation initially widened the trade deficit, largely due to higher oil and industrial import costs, before stabilising as exports in sectors like textiles and IT expanded3, This pattern highlights the significance of understanding the lag between devaluation and export recovery, especially in economies with substantial import dependencies.

As seen in figure 3, trade deficits worsened immediately post-devaluation, then improved, showcasing the J-Curve effect, substantiating theory discussed earlier.

Elasticities and Long-Term Trade Balance Improvement

Devaluation may have negative short-term consequences on India’s trade balance, but long-term benefits are usually favourable as long as export demand is price-sensitive. According to research by Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza (2003), nations with higher export elasticities have a greater chance of seeing long-lasting gains in their trade balance after devaluation. The demand for software, IT services, and textiles in India has a price elasticity of demand that is high enough to produce long-term benefits from devaluation.

However, India’s reliance on inelastic imports limits the benefits of devaluation. According to the Marshall-Lerner Condition, import demand needs to be sensitive to price fluctuations in order for devaluation to be successful. In India’s situation, rising import costs would continue to put pressure on the trade deficit even as export volumes rise due to the poor price elasticity of demand for necessities like crude oil and machinery.

Policy Implications for Managing Elasticities

Increased price elasticity of imports and exports is what policymakers need to concentrate on to get the most out of devaluation. This can be accomplished by taking steps to make India’s export sectors more competitive and less dependent on foreign inputs. By decreasing import demand in reaction to devaluation, Ratha39, contends that increasing domestic energy output and lowering dependency on imported oil might considerably improve India’s trade balance. Similarly, enhancing the efficiency of export industries like manufacturing and IT services through infrastructure and technology investments may increase the competitiveness of Indian exports in international markets.

The government should also concentrate on lowering non-tariff and tariff barriers that raise the price of imported inputs for export-oriented industries. Policymakers can keep export industries competitive even in the face of increased import costs by facilitating and lowering the cost of machinery and raw materials imports for Indian enterprises.

The price elasticity of demand for both imports and exports determines whether currency devaluation will be successful in improving India’s trade balance. The overall effectiveness of devaluation is limited by the inelastic demand for key imports like crude oil, despite the fact that export industries like textiles and IT services are highly responsive to price changes. India can secure long-term gains in its trade balance and maximise the advantages of devaluation by increasing domestic output and decreasing its need on imported inputs.

Social Impacts of Devaluation

Inflationary Pressures and the Cost of Living

Inflation is directly impacted by devaluation, and inflation in turn influences the cost of living in a region. The cost of imported items rises when a currency’s value drops. Since essential imports such as medical supplies, machinery, and energy are price inelastic in India, devaluation raises the cost of these items and causes inflation in a number of sectors.

According to figures from the Reserve Bank of India42. following India’s 1991 devaluation, inflation shot up to 17 % in 1991 and stayed above 10% in the years that followed. The immediate result was a substantial rise in the cost of basics, especially food and fuel, which disproportionately impacted households with lower and middle incomes, as they spend a large portion of their income on these items.

This trend is not unique to India. The 1979 devaluation in Brazil similarly triggered a sharp spike in inflation. According to Cline43, inflation rose from 40 % to over 100 % following Brazil’s devaluation, leading to widespread social unrest as the poor and middle classes faced skyrocketing costs of living.

In Turkey, in 2018 lira devaluation led to annual inflation rates skyrocketing. In October 2018 this rate reached 25.2%, making basic commodities unaffordable for a large part of the population. The probability-of-saving index saw the largest decline, suggesting less people expected to save money. The sub-index dropped 5 percent to 26.8 this month, according to Hürriyet Daily News44. This is proof of the skyrocketing commodity prices in Turkey in 2018 during the fall in exchange rate. The situation led to widespread social discontent, with protests erupting over the government’s mishandling of inflation. In India, similar risks exist, as the inflationary pressures from devaluation could exacerbate existing inequalities, disproportionately harming low-income and middle-income households.

In figure 2, we can see how inflation rose rapidly, peaking around 13–14% in 1991, demonstrating strong pass-through from currency depreciation to domestic prices, disproportionately affecting low-income households.

Income Inequality and the Distributional Impact of Devaluation

Devaluation often makes wealth discrepancies worse, especially in nations where they are already very noticeable. Because devaluation affects different parts of society differently, it has traditionally resulted in increased inequality in India. Increased prices mostly affect the informal sector and rural people that depend on imports for everyday needs, while exporters and sectors associated with global commerce stand to gain.

During the 1991 devaluation, the benefits of liberalisation and devaluation accrued disproportionately to the urban elite and export-oriented industries, while the rural poor faced higher prices for agricultural inputs like fertilisers, which are heavily reliant on imports. According to Joshi and Little3, income inequality in India increased during this period, as the Gini coefficient rose from 0.32 to 0.41 in the years following the devaluation. This pattern mirrors what happened in Argentina following the 2002 peso crisis, where the devaluation benefited export sectors like agriculture, but led to increased poverty and inequality as urban workers faced mass layoffs and rising prices.

Brazil experienced similar outcomes after its 1999 devaluation. According to Paes de Barros and Ferreira45, while the wealthier sections of society, particularly those with foreign currency holdings, were able to shield themselves from inflation, the poor suffered the most, with real wages in the bottom 30% of the population falling by nearly 20%. This reinforces the argument that devaluation exacerbates inequality, particularly when inflation erodes the purchasing power of fixed-income households.

Employment and Labor Market Disruptions

Devaluation has a significant negative societal impact on employment, especially in sectors of the economy that depend on imports. Businesses are compelled to either raise prices, risking losing their competitiveness, or reduce costs, frequently by making layoffs, as input costs rise. The 1991 devaluation in India resulted in a large loss of jobs in sectors that rely on imports, such as machinery and textiles. Dhasmana46 claims that in the first two years after devaluation, a large number of SMEs in India saw widespread layoffs because of their inability to compete internationally due to growing input costs.

The elasticity of demand for imports and exports has a direct bearing on how devaluations affect employment. A weaker currency may help export-oriented industries like IT and agriculture, but companies that depend on imported machinery and oil risk growing costs that may result in lower output and job losses. An obvious example is the Argentinean devaluation in 2001. When the cost of repaying foreign debt increased and inflation skyrocketed, unemployment rose to 25% and social unrest spread widely.

Similar effects on unemployment were seen in Turkey in 2018 following the devaluation of the currency, especially in the manufacturing sector, which depends significantly on imported machinery. Due to skyrocketing input costs, many Turkish businesses were compelled to close or fire employees, further straining the already precarious labour market. Similar dangers exist in India, especially in sectors like the automotive and pharmaceutical industries that rely largely on foreign components. These industries might find it difficult to stay competitive without focused government assistance, which would result in additional job losses.

In figure 4 we can see unemployment edged upward post-devaluation. Import-reliant sectors suffered, even as export-oriented industries eventually rebounded.

Public Services and Social Safety Nets

In particular, when inflation reduces the real value of public spending, devaluation can put pressure on social safety nets and public services. Devaluation might result in a significant decrease in the government’s capacity to fund these initiatives in nations like India, where subsidies on necessities like food and gasoline are vital to preserving social stability. Public spending on important social programs was cut because of the 1991 devaluation, especially in rural areas, as the government was compelled to give debt repayment and budgetary consolidation top priority.

Following the devaluation in 2002, inflation severely damaged the government’s budget in Argentina, forcing cuts to vital services like healthcare and education. The World Bank (2003) observed that because the poorest households depend more heavily on public services, they were disproportionately affected by the decrease of public spending that followed devaluation.

The 2008 devaluation in Brazil had a similar impact on public services. As the government was forced to cut back on social programs to manage its external debt, inequality and poverty worsened. Many of the poorest households were left without adequate access to healthcare, education, and subsidised food programs, exacerbating existing social tensions.

Results

The findings from the analysis are summarised systematically below:

The analysis reveals three main outcomes of India’s currency devaluations. First, exports in sectors such as textiles and IT rose significantly, confirming that devaluation can improve competitiveness. Second, inflation surged, particularly in 1991, disproportionately impacting low- and middle-income households. Third, foreign debt servicing burdens increased as the rupee depreciated against the dollar, diverting government resources away from development spending. Comparisons with Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey show similar short-term boosts followed by inflationary and social costs, but India avoided hyperinflation and political collapse due to stronger institutions and much more timely economic reforms. Unemployment also increased in the aftermath of both devaluations, particularly in industries dependent on imported inputs, while inflation eroded real wages, contributing to greater income inequality.

Marshall–Lerner Elasticity Test

Equation: |Eₓ| + |Eₘ| > 1

Using India’s data (1991), textile export elasticity ≈ 1.4, IT export ≈ 1.7, and oil import elasticity ≈ –0.2; the combined elasticity is 2.9. Although this satisfies the condition (implying trade balance should improve), inelastic oil import reliance delayed adjustment, explaining the J-Curve outcome.

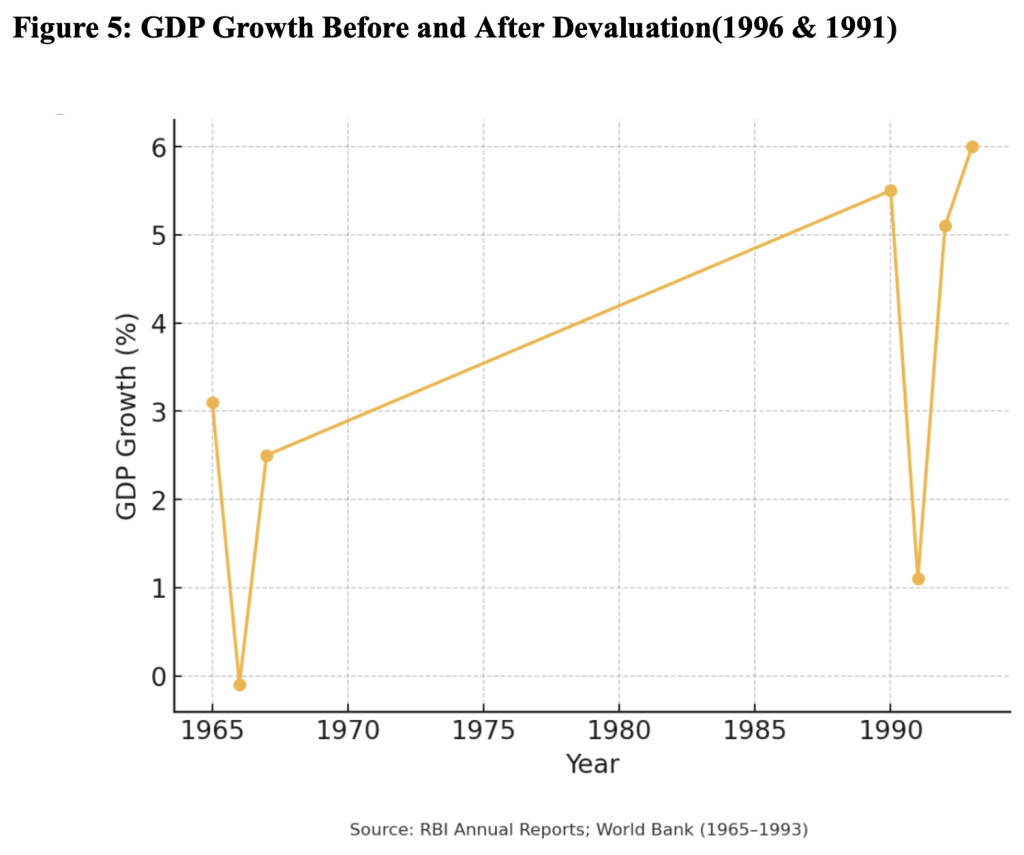

As seen in figure 5, GDP growth contracted sharply following both devaluations, consistent with short-run contractionary pressures. Recovery within 1–2 years suggests the importance of structural reforms and stimulus.

It is important to note, export elasticities exceeded the threshold, theoretically favoring improved trade balance. However, oil import inelasticity diluted the effect, resulting in initial trade deterioration despite satisfying the condition as seen in figure 6.

A weighted Marshall–Lerner calculation provides further insight. Assuming oil accounts for 25% of imports with an elasticity of –0.2, and other imports average –0.8, the weighted import elasticity is –0.65. Combined with average export elasticity of 1.55, the total elasticity is approximately 2.2, exceeding the threshold of one. This suggests that India’s devaluations should improve the trade balance in the long run. However, the dominance of oil imports in the short term delayed this adjustment, causing the immediate deterioration observed in 1966 and 1991, consistent with the J-Curve effect.

While the weighted Marshall–Lerner elasticity for India is approximately 2.2, which theoretically satisfies the condition, the heavy weight of oil imports reduces the likelihood of immediate trade balance improvement. In practice, the trade balance worsens in the short run because oil prices are both inelastic and essential, driving up import costs. Over time, however, export responsiveness ensures that the Marshall–Lerner condition is met sufficiently for the trade balance to recover. The overall likelihood, therefore, is high in the long run but low in the immediate aftermath of devaluation. This dynamic outcome aligns with the J-Curve model, where short-term deterioration is followed by gradual improvement once inflationary pressures subside.

In table 1 we can see that Export elasticities (textiles: 1.4; IT: 1.7) outweighed the weighted import elasticity (–0.65), giving a combined elasticity of 2.2. This exceeds the threshold of one, suggesting that devaluation should improve the trade balance, although oil import inelasticity delayed short-run adjustment.

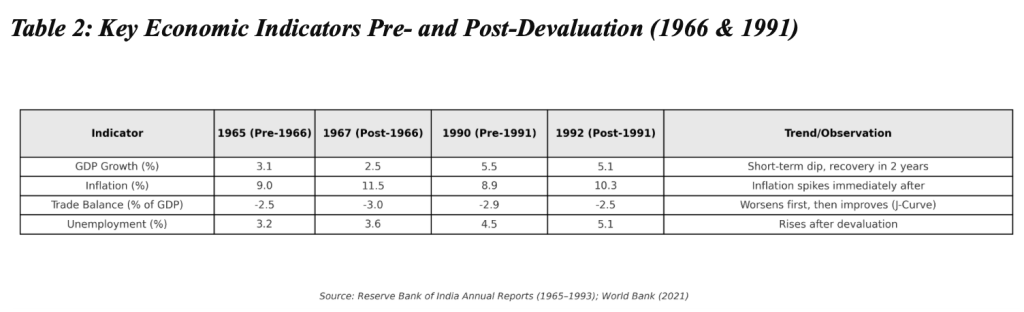

While Table X demonstrates that India’s trade elasticities satisfied the Marshall–Lerner condition in theory, the overall macroeconomic impact of devaluation is best understood by looking at broader indicators. Table Y provides a systematic summary of GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, and unemployment before and after the 1966 and 1991 devaluations, complementing the earlier figures.

GDP growth dipped immediately after both devaluations but recovered within two years. Inflation spiked sharply, trade balance worsened initially before improving (J-Curve), and unemployment rose in both episodes. Table 2 summarises the key economic indicators before and after the 1966 and 1991 devaluations, complementing Figures 1–6 by presenting the changes systematically.

Discussion

These results carry important implications when interpreted in light of existing literature:

These findings directly address the research question of how devaluation affects India’s economy and society. While devaluation can temporarily boost exports and attract investment, its broader impacts depend heavily on a country’s import structure and institutional capacity.

The evidence from India, compared with Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey, indicates that economies reliant on inelastic imports like oil face greater inflationary pressures. At the same time, India’s experience highlights that complementary reforms, such as trade liberalisation in 1991, are critical for ensuring long-term benefits.

When compared with the existing literature, the results support Joshi and Little’s3, claim that India’s 1991 devaluation was effective only because it was paired with wider reforms. They also align with Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza’s15, findings that devaluation in developing countries tends to be expansionary in the long run but contractionary in the short run. However, the results diverge from overly optimistic applications of the Marshall–Lerner condition, showing how essential inelastic imports like oil can delay adjustment and produce initial deterioration.

A key reason India’s 1991 devaluation did not lead to hyperinflation or political collapse, unlike Argentina in 2001 or Turkey in 2018, lies in institutional and policy differences. India implemented the devaluation as part of a broader IMF-supported structural reform package that included fiscal consolidation, trade liberalisation, and industrial deregulation. These policies helped stabilise expectations and attract investment. In comparison, Argentina lacked credible fiscal discipline, while Turkey faced persistent political instability. India also benefited from relatively independent institutions, including the Reserve Bank of India, which managed monetary policy to contain runaway inflation. The lesson is that devaluation alone is insufficient; it must be paired with proper reforms, institutional resilience, and social safeguards.

This study is limited by its reliance on secondary data and descriptive analysis rather than econometric testing, which restricts causal inference. The implications are threefold. Theoretically, the results suggest that classical models like Marshall–Lerner and J-Curve must be refined for oil-importing developing economies. Practically, they show that vulnerable groups face disproportionate costs, highlighting the importance of social safety nets. From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the need for strong institutions, effective debt management, and adequate foreign exchange reserves to cushion against external shocks.

Future research could extend this analysis by applying econometric models to India’s historical data, exploring more recent depreciation episodes (such as 2013 and 2018), or using household-level data to capture distributional effects. Comparative studies across a larger sample of emerging economies would also help identify why some countries experience collapse while others recover.

Conclusion

Taken together, the findings and discussion allow us to draw several key conclusions. Currency devaluation has proven to be a two-edged sword for India. Even though it can boost export growth, balance trade, and attract foreign direct investment, the social consequences are significant. The most vulnerable members of society include the poor, middle-class people, and those who depend on imports; they suffer disproportionately from unemployment, inflation, and limited access to public services.

While devaluation may attract foreign investors by lowering the cost of Indian assets, it can also undermine investor confidence if it signals deeper instability. Sustained macroeconomic stability is therefore essential to convert short-term capital inflows into long-term investment.

Foreign debt also magnifies the risks of devaluation, as repayments in dollars become costlier when the rupee depreciates. Careful debt portfolio management, diversification away from foreign-denominated borrowing, and the accumulation of adequate reserves are critical for long-term stability.

While devaluation could offer short-term economic respite, its long-term viability depends on rigorous macroeconomic control, especially with regard to inflation and debt servicing. Along with case studies from Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey, India’s experiences with devaluation in 1966 and 1991 show that although devaluation might boost an economy, it can also worsen income disparity, jeopardise social safety nets, and raise unemployment.

Devaluation is only a practical strategy in conjunction with robust measures to protect marginalised populations, rein in inflation, and enhance public services. In the absence of these safeguards, devaluation is expected to have more negative societal effects than positive ones, particularly in a country as diverse and unequal as India.

In conclusion, devaluation has been a critical but costly tool for India. It has restored export competitiveness and stabilised the economy during crises, but its severe social costs—higher inflation, heavier debt burdens, and unemployment—show that it cannot be treated as a simple solution. For devaluation to be effective, it must be complemented by sound debt management, targeted social protection, and structural reforms. A practical roadmap should include diversifying borrowing away from foreign-denominated debt, building adequate reserves, negotiating concessional credit during crises, and improving fiscal discipline. This study is limited by its reliance on secondary data and descriptive methods rather than econometric testing, which restricts causal inference. Future research could apply econometric models to India’s data, analyse more recent episodes, and use household-level surveys to capture distributional effects. Overall, the findings underline that devaluation is not a silver bullet, but when paired with credible reforms and protections, it can serve as a turning point in overcoming crisis.

References

- Marshall, A., & Lerner, A. P. (1939). The elasticity of substitution in export and import demand. Economic Journal. [↩] [↩]

- Reserve Bank of India. (2020). Annual Report: Economic Outlook and Policy. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- V. Joshi, I. M. D. Little. India’s Economic Reforms, 1991-2001. Oxford University Press (1996). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Dornbusch, R. (1976). Expectations and Exchange Rate Dynamics. Journal of Political Economy, 84(6), 1161–1176. [↩]

- Srinivasan, T. N., & Tendulkar, S. (2003). Re-integrating India with the World Economy. Institute for International Economics. [↩]

- Government of India. (1992). Economic Survey 1991–92. Ministry of Finance.); (Reserve Bank of India. (1992). India’s Balance of Payments Crisis and the Role of IMF Assistance. [↩]

- T. N. Srinivasan, S. Tendulkar. Re-integrating India with the World Economy. Institute for International Economics (2003). [↩]

- Magee, S. P. (1973). Currency Contracts, Pass-Through, and Devaluation. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 303–350. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- IMF. (2019). Turkey Economic Outlook. IMF Working Paper Series. [↩]

- Das, D. K., & Pant, M. (1997). India’s Trade and Payments: Crisis of 1991 and Beyond. Economic & Political Weekly. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ratha, A. (2010). Does Devaluation Work for India? Economics Bulletin, 30(1), 247–264. [↩] [↩]

- Krugman, P., & Taylor, L. (1978). Trade Policy and Exchange Rate in Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press. [↩] [↩]

- World Bank. (1994). India: Structural Adjustment Program. Washington DC. [↩]

- Akyüz, Y., & Boratav, K. (2003). The Making of the Turkish Financial Crisis. UNCTAD.); (Amann, E., & Baer, W. (2002). Brazil’s Development in Long-Term Perspective. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 42(4), 425–445. [↩]

- M. Bahmani-Oskooee, I. Miteza. Are Devaluations Expansionary or Contractionary? A Survey Article. Economic Issues (2003). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Edwards, S. (1989). Real Exchange Rates, Devaluation, and Adjustment: Exchange Rate Policy in Developing Countries. MIT Press. [↩]

- Cuddington, J. T. (1986). Capital Flight: Estimates, Issues, and Explanations. Princeton Studies in International Finance, 58. [↩]

- Pastor, M. (1990). Capital Flight from Latin America. World Development, 18(1), 1–18. [↩]

- Reserve Bank of India. (1992). India’s Balance of Payments Crisis and the Role of IMF Assistance. Reserve Bank of India. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Schneider, B., & Tornell, A. (2004). Balance Sheet Effects, Bailout Guarantees and Financial Crises. Review of Economic Studies, 71(3), 883–913. [↩]

- Ministry of Finance, Government of India. (2020). Economic Survey 2019–20. Ministry of Finance. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Cline, W. R. (1984). International Debt Reexamined. Institute for International Economics. [↩] [↩]

- World Bank. (2021). World Development Indicators: Infrastructure Investment Needs. World Bank. [↩] [↩]

- (IMF. (2019). Turkey Economic Outlook. IMF Working Paper Series.); (Clements, M. (2018, November 5). Inflation has hit 25 percent in Turkey. CNBC. [↩]

- IMF. (2019). Turkey Economic Outlook. IMF Working Paper Series.); (Clements, M. (2018, November 5). Inflation has hit 25 percent in Turkey. CNBC. [↩]

- World Bank. (2003). Public Services in Crisis: Argentina’s Economic Collapse. World Bank. [↩] [↩]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2019). Turkey economic outlook 2018. IMF Working Paper Series. [↩]

- P. Krugman, L. Taylor. Trade Policy and Exchange Rates in Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press (1978). [↩]

- E. Amann, W. Baer. Brazil’s Development in Long-Term Perspective. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 42 (4), 425-445 (2002). [↩]

- J. Frankel. Monetary Policy in Emerging Markets: A Survey. NBER Working Paper (2010). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. R. Ghosh, R. Rajan. The Inflation Conundrum in Emerging Economies. IMF Working Paper (2009). [↩]

- Y. Akyüz, K. Boratav. The Making of the Turkish Financial Crisis. UNCTAD (2003). [↩]

- I. Domac. The Distributional Impact of the Peso Crisis. The World Bank (1997). [↩]

- Dhasmana, A. (2013). Oil Imports and Trade Deficit in India. Reserve Bank of India. [↩]

- S. Galiani, D. Heymann, M. Tommasi. Great Depressions of the Twentieth Century. MIT Press (2003). [↩]

- Galiani, Heymann, & Tommasi, 2003 [↩]

- G. Datt, M. Ravallion. Why Has Economic Growth Been More Pro-Poor in Some States of India Than Others? Journal of Development Economics 69 (1), 133-164 (2002). [↩]

- Frankel, J. (2010). Monetary Policy in Emerging Markets: A Survey. NBER Working Paper. [↩]

- D. Ratha. Leveraging Remittances for Development. World Bank (2006). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- World Bank. (2023). Foreign direct investment, net inflows (BoP, current US$) – India. [↩]

- Aizenman, A., & Noy, I. (2006). Devaluation and FDI: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Development Economics [↩] [↩]

- Reserve Bank of India. Annual Report: Economic Outlook and Policy. (2020). [↩] [↩]

- W. R. Cline. International Debt Reexamined. Institute for International Economics (1984). [↩]

- Türkiye’s sectoral confidence goes down in May. Hürriyet Daily News. 22 May 2020. [↩]

- R. Paes de Barros, F. Ferreira. The Dynamics of Poverty and Inequality in Brazil. World Bank (2002). [↩]

- A. Dhasmana. Oil Imports and Trade Deficit in India. Reserve Bank of India (2013). [↩]