Abstract

This study examines the effects of financial and trade globalisation on the Indian economy using time series data from 1975 to 2023. Drawing on secondary data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, the research explores how trade (% of GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) net inflows (% of GDP) influence six key development metrics: GDP per capita, unemployment rate, Gini coefficient, life expectancy, school enrollment, and real GDP growth (annual %). To quantify these relationships, the research paper employs scatterplots and apply ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regressions to assess the aggregate impact of rising trade and FDI on economic and social outcomes. By analyzing long-term trends, the study aims to determine whether globalisation has been a driver of growth, equity, and improved living standards in India. The dual focus on trade and financial openness provides a holistic view of globalisation’s influence on a developing economy undergoing significant structural transformation. The findings are intended to support informed policymaking on global economic integration and its role in national development strategies.

Keywords: Financial Globalisation, Trade Globalisation, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Trade Openness, Indian Economy, GDP per Capita, Gini Coefficient, Unemployment, Life Expectancy, School Enrollment, Real GDP Growth, Time Series Analysis, World Bank, Economic Development.

Section 1: Introduction

This research investigates what the effects of financial and trade globalisation on the Indian economy? Specifically, it examines how increased trade (as a percentage of GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) net inflows (as a percentage of GDP) relate to various economic and social development indicators in India. Trade globalisation refers to the increasing interconnectedness of national economies through the exchange of goods, services, and capital across borders. Financial globalisation refers to the increasing interconnectedness of national financial systems through cross border financial flows and investments. Both trade and financial globalisation are the core aspects of globalisation. This topic is highly relevant in the context of India’s gradual liberalisation since the 1991 economic reforms, which opened the country to global markets. Over the decades, India has seen a sharp increase in both trade and FDI inflows, raising important questions about how these globalisation trends have affected not only economic growth but also broader development metrics such as income distribution, education, and health outcomes.

Understanding the effects of globalisation is crucial because policymakers and economists often debate whether global market integration promotes inclusive and sustainable growth. Several studies have explored globalisation’s economic impact, but with varying conclusions. For example, Bhagwati (2004) argues that trade liberalisation fosters growth and poverty reduction, while Rodrik (2011) emphasizes the risks of unequal distribution and weakened domestic institutions1,2. In the Indian context, Panagariya (2008) presents a largely positive view of trade openness, but critics point out that social inequalities persist despite economic gains3. These conflicting perspectives underscore the need for further empirical analysis focused on India’s experience.

The results of this study show that there is no clear correlation between trade/FDI inflows and GDP growth or unemployment rate. However, there is a positive correlation between trade (% of GDP) and FDI net inflows (% of GDP) with GDP per capita, life expectancy, school enrollment, and the Gini index. The positive relationship with the Gini index indicates that as trade and financial globalisation increase, income inequality also tends to rise. This suggests that while globalisation may contribute to improvements in living standards and human development indicators over the long term, these gains are not necessarily distributed evenly across the population. In other words, globalisation appears to benefit certain groups more than others, potentially widening the gap between higher- and lower-income segments of society. Thus, while it may enhance development outcomes, it also raises concerns about equity and the need for inclusive policy interventions.

This research contributes to the existing literature by providing a focused, time-series-based analysis of the aggregate effects of globalisation on multiple dimensions of the Indian economy. While previous studies often emphasize either growth or inequality in isolation, this paper examines multiple indicators side-by-side. In doing so, it builds on prior work by authors such as Basu and Maertens (2007), who highlighted globalisation’s mixed effects in India, and adds value by quantifying correlations over nearly five decades4.

The methodology involves using World Bank World Development Indicators from 1975 to 2022. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression is applied to identify trends and associations between globalisation metrics and development indicators. Scatterplots and regression analysis are used to visualize and estimate these relationships. However, this study is preliminary and descriptive rather than inferential. It does not establish causality, and results are based solely on correlations. Additionally, limitations include the exclusion of contextual variables such as domestic policy changes or external shocks. As such, findings should be interpreted as exploratory insights rather than definitive conclusions.

Section 2: Literature Review

The effects of globalisation on emerging economies like India have been widely debated, particularly in the context of trade liberalisation and increased financial openness. Existing studies often emphasize economic performance, focusing heavily on GDP growth or export expansion. However, there remains limited empirical exploration of how globalisation influences a broader set of development indicators such as inequality, education, health, and employment especially when trade and financial integration are studied together. This literature review critically examines the key contributions in the field and highlights the methodological and thematic gaps that this research seeks to address.

Trade Globalisation and Development Outcomes

Joseph (2013) conducts a time-series regression analysis to investigate whether India’s trade liberalisation post-1991 contributed to inclusive growth5. While he observes a positive effect on exports and GDP, he finds little evidence of improved employment rates or income distribution. His work underscores the phenomenon of “jobless growth” in Indian manufacturing. However, the study lacks attention to non-economic indicators such as school enrollment or health, thus limiting its analysis to a narrow concept of development.

Bhasin and Manocha (2014) employ a panel gravity model to examine the effects of regional trade agreements on India’s export performance6. Their econometric model confirms that increased trade openness enhances export volumes, but the study is firmly rooted in trade economics and does not address whether such integration translates into improved well-being or social equity. The absence of indicators such as inequality, education, or life expectancy restricts the policy relevance of their conclusions to trade-specific outcomes.

Similarly, Abraham et al. (2016) assess the impact of trade reforms on manufacturing employment using national-level data and basic regression tools7. They find limited employment elasticity, pointing to structural rigidities in India’s labor market. While their work is significant in addressing labor-market consequences, it remains sector-specific and does not examine the broader development implications of trade liberalisation.

Niemi et al. (2025) take a novel turn by assessing the environmental consequences of trade liberalisation in India8. Through a regional comparative framework, they document increased water pollution post-1991 reforms. Their work introduces important externalities to the trade globalisation debate but, once again, does not connect trade trends to core social outcomes like education or life expectancy.

Financial Globalisation and Social-Economic Impacts

Patnaik and Shah (2011, 2013) provide a comprehensive descriptive and policy analysis of India’s capital account liberalisation9. Their narrative, supported by structural indicators and case studies (e.g., responses to the 2008 global financial crisis), traces how India shifted from portfolio-dominated inflows to more stable FDI. While rich in institutional detail, their studies are descriptive and stop short of empirically evaluating how FDI relates to development metrics such as inequality, schooling, or public health.

In a more empirically rigorous study, Chaliyan et al. (2021) use OLS time-series regressions on data from 1980 to 2014 to explore how financial development and globalisation impact income inequality in India10. They find that while financial globalisation may initially exacerbate inequality, educational improvements can mitigate these effects. Their model includes education and inflation as control variables, offering a more nuanced understanding of globalisation’s distributive effects. However, their focus is limited to inequality and does not extend to other development indicators.

Chaliyan and Thomas (2021) apply cointegration and Vector AutoRegression (VAR) models to explore the causal relationship between financial development and trade openness10. Their results show unidirectional causality from financial development to trade, suggesting financial sector maturity can enhance integration with global markets. While methodologically robust, their study is macro-structural in focus and does not evaluate downstream consequences such as impacts on human capital or well-being.

Gaps in the Existing Literature

Across these studies, several gaps are evident. First, most research focuses on either trade or financial globalisation in isolation. Integrated analyses that simultaneously consider both dimensions are rare. Second, the outcome variables tend to be narrow—centered around GDP growth, export performance, or income inequality—while broader human development indicators like life expectancy, school enrollment, or unemployment are often overlooked. Third, although some studies employ advanced econometric techniques such as VAR or gravity models, there is a lack of long-run, descriptive correlation studies that can reveal enduring trends over multiple decades.

Moreover, few studies take a truly multidimensional approach to development, despite globalisation being a multifaceted process with economic, social, and institutional consequences. There is a need for accessible, baseline studies that assess the aggregate, non-causal relationships between globalisation and various development outcomes. Such work can provide a foundation for deeper, causal analysis in the future.

Contribution of the Current Study

This research addresses these gaps by using time-series data from 1975 to 2023 sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators to analyze the relationship between trade (% of GDP), FDI net inflows (% of GDP), and six development indicators: GDP per capita, real GDP growth, unemployment rate, Gini coefficient, life expectancy, and school enrollment. The use of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression and scatter plot visualisations enables a clear and intuitive presentation of long-term correlations. While the study is descriptive and does not infer causality, its multi-indicator approach offers a more holistic perspective on globalisation’s relationship with development.

By jointly examining trade and financial globalisation across a broader range of outcomes and over a longer time frame than most prior research, this study contributes a new layer of insight to the existing literature. It provides a descriptive empirical baseline that future research can build upon using more complex statistical or comparative methods. In doing so, it helps fill a critical gap: understanding the long-term, aggregate relationships between globalisation and development in one of the world’s largest and most dynamic emerging economies.

Section 3: Methodology

This study uses a descriptive, correlation-based methodology to examine the relationship between trade and financial globalisation—measured by trade (% of GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) net inflows (% of GDP)—and six development indicators in India: GDP per capita, real GDP growth (annual %), unemployment rate, Gini index, life expectancy, and school enrollment. The analysis relies entirely on secondary data sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Time series data from 1975 to 2023 is used for all indicators except for the unemployment rate, available only from 1991 to 2023, and the Gini index, for which data is limited to the years 1977, 1983, 1987, 1993, 2004, 2009, 2011, and 2015 to 2021. To estimate the relationships between the globalisation variables and development outcomes, the study uses Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, alongside scatterplot visualisations. The general OLS model applied follows the form:

(1) ![]()

Where Yᵢ is the dependent variable (each development indicator), Xᵢ is the independent variable (either trade or FDI), β₀ is the intercept, β₁ is the slope coefficient, and εᵢ is the error term accounting for variation not explained by the model. This model assumes linearity and independence of residuals and minimizes the sum of squared errors to derive the best-fitting line. The regressions were implemented using Microsoft Excel’s Data Analysis Toolpak. Excel’s built-in regression tool calculates slope, intercept, standard errors, t-statistics, F-statistics, R-squared values, and p-values.

These statistical outputs are used to assess both the strength (via R²) and significance (via p-values) of the relationships, and to help identify potential collinearity. Due to the limited scope of the study, only aggregate national-level data is used, and no primary data collection is involved. Additionally, diverse datasets have not been incorporated, as all data is sourced solely from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. The analysis is descriptive rather than inferential and does not attempt to establish causality. Furthermore, core assumptions of OLS regression—such as linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals—are acknowledged but not formally tested. Despite these limitations, the approach offers a practical and informative overview of long-term patterns in India’s globalisation-development relationship.

Section 4: Data Analysis

GDP per Capita

Trade openness is positively and strongly associated with GDP per capita. The regression yields a slope of 30.52, an R² of 0.691, and a highly significant p-value below 0.01. A t-statistic of 10.26 and F-statistic of 105.23 demonstrate excellent model strength, with a standard error of 2.975 indicating high precision. FDI net inflows also show a significant positive effect, with a slope of 443.33, an R² of 0.519, and a p-value below 0.01. The t-statistic of 7.117 and F-statistic of 50.65 further validate the reliability of the regression, though with more dispersion (standard error = 62.30). These results support the findings of Alfaro et al. (2004), who conclude that both trade and FDI raise income levels in developing economies by improving productivity, facilitating technology transfer, and expanding access to global markets11. In India, rising exports and foreign investment have supported income growth particularly in technology, pharmaceuticals, and services.

GDP Growth (Annual %)

Trade and FDI show no statistically significant correlation with annual GDP growth in India. For trade, the slope is 0.0427, R² is 0.0433, and the p-value is above 0.05, with a t-statistic of 1.458 and F-statistic of 2.13. The standard error is 0.0293, indicating decent estimate precision despite weak significance. For FDI, the slope is 0.1252, R² is just 0.0013, and the p-value is above 0.05. The corresponding t-statistic is 0.250, F-statistic is 0.062, and the standard error is 0.5015. These low R² and t-values suggest that annual growth is not directly influenced by year-on-year changes in globalisation metrics. Alfaro and Chauvin (2021) explain that trade and FDI influence growth through structural transformation and productivity over time, not short-term fluctuations11. In India, annual GDP growth is also shaped by domestic policies, agricultural cycles, and global macroeconomic trends, which dilute the visible impact of trade and investment flows in any single year.

Gini Index

Regression results show that trade (% of GDP) is positively correlated with income inequality, with a slope of 0.0697, an R² of 0.582, and a p-value below 0.01. The t-statistic of 4.091 and F-statistic of 16.74 indicate moderate explanatory power, supported by a low standard error of 0.017. FDI net inflows (% of GDP) also show a positive association with the Gini index, with a slope of 1.0047, an R² of 0.536, and a p-value below 0.01. The t-statistic of 3.724 and F-statistic of 13.87 reinforce the model’s validity, while the standard error of 0.2698 suggests reasonable estimate precision. These findings reflect the inequality-deepening effects of globalisation noted in peer-reviewed studies. Herzer and Nunnenkamp (2013) found that FDI increases income disparities in developing countries due to skill-biased capital flows, while Ichihashi (2014) showed trade liberalisation can increase inequality where informal labor dominates12,13. In India, globalisation has mostly benefited capital-intensive, urban sectors, while informal and rural workers have seen fewer direct gains.

Life Expectancy

Trade is strongly and significantly linked to improvements in life expectancy. The slope of the regression is 0.3703, with an R² of 0.807 and a p-value below 0.01. The t-statistic of 14.01 and F-statistic of 196.41 indicate a highly reliable model, with a low standard error of 0.0264 confirming the consistency of the estimate. FDI also has a significant positive effect, with a slope of 5.5565, an R² of 0.646, and a p-value below 0.01. With a t-statistic of 9.265, an F-statistic of 85.84, and standard error of 0.5997, the model shows strong explanatory power. These results are supported by Zhang et al. (2022), who find that trade and investment improve health outcomes in Asia through better nutrition, healthcare access, and infrastructure14. In India, trade and FDI have enabled the import of medical technologies, improved health infrastructure, and raised income levels that support long-term health gains.

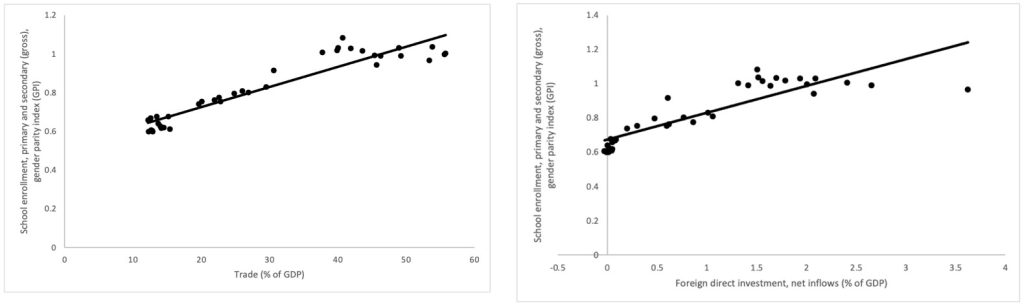

School Enrollment (Gender Parity Index)

Trade is very strongly correlated with improvements in gender parity in school enrollment, showing a slope of 0.01045, an R² of 0.887, and a p-value below 0.01. The t-statistic is 16.77, the F-statistic is 281.36, and the standard error is just 0.000623, suggesting a near-perfect fit and very stable estimates. FDI also shows a significant relationship, with a slope of 0.1568, an R² of 0.758, and a p-value below 0.01. The model’s strength is supported by a t-statistic of 10.63, F-statistic of 112.91, and standard error of 0.01475. These outcomes reflect Asongu and Odhiambo (2019), who found that globalisation enhances educational access and gender equity in lower-income countries by increasing both public and private investments in human capital15. In India, greater economic openness has encouraged educational reform, expanded infrastructure, and raised awareness of the value of schooling, particularly for girls.

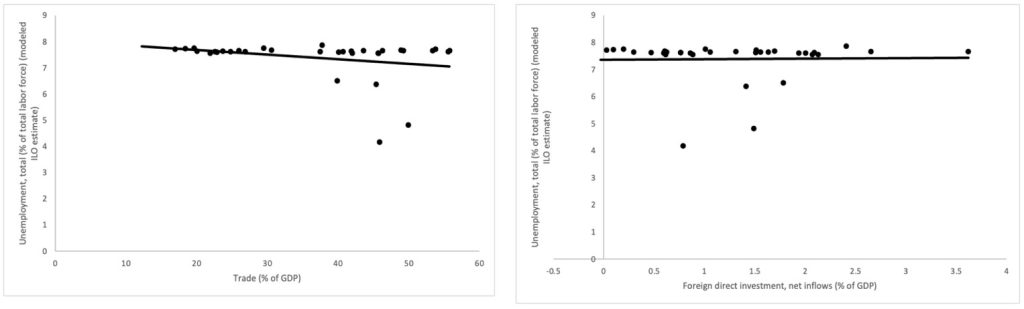

Unemployment Rate

The regression results reveal that trade (% of GDP) has a weak and statistically insignificant relationship with the unemployment rate. The slope is –0.0175, with an R² of 0.071 and a p value above 0.05. The t-statistic of –1.535 and F-statistic of 2.36 confirm that the model lacks explanatory strength, and the standard error of 0.0114 suggests variability in the estimate. FDI net inflows (% of GDP) show an even weaker and statistically negligible relationship, with a slope of 0.0176, an R² of just 0.0003, and a p value above 0.05. The corresponding t-statistic is 0.099 and the F-statistic is 0.01, indicating an almost non-existent fit. These results are consistent with findings by Abraham et al. (2016), who document “jobless growth” in India’s liberalisation period—highlighting that increases in trade and FDI have raised productivity without proportionally boosting employment7. This is partly due to the predominance of the informal sector and the capital-intensive nature of industries attracting FDI, which generate limited direct job opportunities.

| Indicator | Variable | Slope | R² | p-value | Std. Err | t‑Stat | F‑stat | Significance F |

| Gini Index | Trade | 0.0697 | 0.582 | p < 0.01 | 0.0170 | 4.091 | 16.74 | p < 0.01 |

| FDI | 1.0047 | 0.536 | p < 0.01 | 0.2698 | 3.724 | 13.87 | p < 0.01 | |

| Unemployment Rate | Trade | –0.0175 | 0.071 | p > 0.05 | 0.0114 | –1.535 | 2.36 | p > 0.05 |

| FDI | 0.0176 | 0.0003 | p > 0.05 | 0.1782 | 0.099 | 0.01 | p > 0.05 | |

| GDP per Capita | Trade | 30.52 | 0.691 | p < 0.01 | 2.975 | 10.26 | 105.23 | p < 0.01 |

| FDI | 443.33 | 0.519 | p < 0.01 | 62.30 | 7.117 | 50.65 | p < 0.01 | |

| Life Expectancy | Trade | 0.3703 | 0.807 | p < 0.01 | 0.0264 | 14.01 | 196.41 | p < 0.01 |

| FDI | 5.5565 | 0.646 | p < 0.01 | 0.5997 | 9.265 | 85.84 | p < 0.01 | |

| School Enrollment | Trade | 0.01045 | 0.887 | p < 0.01 | 0.00062 | 16.77 | 281.36 | p < 0.01 |

| FDI | 0.1568 | 0.758 | p < 0.01 | 0.01475 | 10.63 | 112.91 | p < 0.01 | |

| GDP Growth (Annual %) | Trade | 0.0427 | 0.0433 | p > 0.05 | 0.0293 | 1.458 | 2.13 | p > 0.05 |

| FDI | 0.1252 | 0.0013 | p > 0.05 | 0.5015 | 0.250 | 0.062 | p > 0.05 |

Section 5: Conclusion and Discussion

This study set out to investigate the effects of financial and trade globalisation on key development indicators in India using OLS regressions across time series data. The results present a nuanced picture: while trade and FDI have clear, statistically significant associations with improvements in GDP per capita, life expectancy, and school enrollment, they also correlate with increased income inequality. Importantly, neither trade nor FDI show a significant relationship with GDP growth (annual %) or unemployment, highlighting a decoupling between global integration and short-term macroeconomic performance.

These findings carry critical implications for policy. The positive associations between globalisation and indicators like GDP per capita and life expectancy suggest that economic openness has contributed to long-term improvements in living standards. This supports policy narratives that promote trade liberalisation and investment openness as tools for structural development. However, the concurrent rise in income inequality highlights a distributional problem: globalisation’s gains are not being shared equally. Trade and FDI disproportionately benefit skilled labor and capital-intensive sectors, often located in urban areas, leaving informal and rural populations behind.

From a policy perspective, this calls for a dual approach. On one hand, India should continue to deepen its trade and investment ties to sustain productivity and development. On the other, policymakers must actively redistribute these gains through targeted fiscal policies, investments in rural infrastructure, labor protections, and skills training. Strengthening social safety nets and ensuring inclusive access to health and education services are essential to prevent inequality from undermining the developmental gains globalisation helps enable.

The findings also add nuance to the academic literature on globalisation’s effects. While past studies such as those by Alfaro et al. (2004) and Zhang et al. (2022) have highlighted the benefits of openness on income and health, others—like Herzer and Nunnenkamp (2013) and Ichihashi (2014)—have cautioned against its regressive social impacts16,17,12,13. This study contributes by showing both dynamics playing out simultaneously in the Indian context: development gains coexisting with widening inequality and stagnant employment, particularly within the informal economy. It also reinforces recent empirical work (e.g., Abraham et al., 2016) that questions the assumed link between liberalisation and job creation7.

These results matter for policy not just in India, but across other developing countries navigating the challenges of globalisation. They underline the need to look beyond GDP growth as the sole indicator of success and instead focus on how growth is distributed, and who benefits from integration into global markets. Future research could build on this study by incorporating sectoral breakdowns or testing for causal mechanisms using panel data, to better understand how specific policies and industries mediate globalisation’s effects.

In conclusion, this research reaffirms that globalisation can act as a powerful engine for development—but only if its benefits are paired with inclusive, equitable domestic policy. Left unmanaged, rising inequality risks offsetting the very progress globalisation makes possible.

References

- Bhagwati, J. (2004). In Defense of Globalization. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Rodrik, D. (2011). The Globalisation Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. W.W. Norton & Company. [↩]

- Panagariya, A. (2008). India: The Emerging Giant. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Basu, K., & Maertens, A. (2007). The growth magazine: Globalisation and inequality in India. Journal of Development Studies, 43(7), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701384544 [↩]

- Joseph, E. (2013). Jobless growth in Indian manufacturing: A time-series analysis. Indian Economic Review, 48(2), 155–170. [↩]

- Bhasin, N., & Manocha, V. (2014). Regional trade agreements and India’s export performance: A gravity model approach. World Economy, 37(5), 714–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12157 [↩]

- Abraham, V., Basole, A., & Joseph, K. J. (2016). Jobless growth in India’s manufacturing. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(1), 23–31. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Niemi, J., Sharma, P., & Verma, R. (2025). Trade liberalisation and environmental externalities in India: A regional study. Environmental and Development Economics, 30(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X24000311 [↩]

- Patnaik, I., & Shah, A. (2013). Capital account liberalisation in India: Impact and policy perspectives. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 21(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-08-2012-0050 [↩]

- Chaliyan, V., & Thomas, M. (2021). Financial development and trade openness in India: Evidence from cointegration and VAR models. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(4), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-08-2020-0412 [↩] [↩]

- Alfaro, L., & Chauvin, J. (2021). Why doesn’t foreign direct investment always lead to growth? Review of Development Finance, 11(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2020.100284 [↩] [↩]

- Herzer, D., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2013). Inward and outward FDI and income inequality: Evidence from Europe. Review of World Economics, 149(2), 395–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-012-0122-y [↩] [↩]

- Ichihashi, M. (2014). Trade liberalisation and inequality in developing countries. World Development, 64, 750–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.003 [↩] [↩]

- Zhang, Y., Zhu, C., & Liu, R. (2022). Trade openness and health outcomes: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Asian Economics, 81, 101342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2022.101342 [↩]

- Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2019). Globalisation, education, and gender parity in sub‑Saharan Africa: Empirical evidence. Health Economics, 28(9), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4005 [↩]

- Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli‑Özcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2004). FDI and economic growth: The role of local financial markets. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00081-3 [↩]

- Zhang, Y., Zhu, C., & Liu, R. (2022). Trade openness and health outcomes: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Asian Economics, 81, 101342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2022.101342 [↩]