Abstract

This literature review provides an overview and analysis of the impact of diet and air pollution on breast cancer in US women. The review examines the individual effects of each factor, and then explores how they interact with one another. The sources identify a range of dietary and air pollution factors that contribute to breast cancer risk. Dietary factors examined include: Meat Consumption, particularly smoked or grilled meat, Dairy Intake – milk and cheese were found to be associated with higher breast cancer risk, while other dairy products seemed to reduce risk, and Produce Consumption (fruits and vegetables). Air pollution factors analyzed include: Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS), Benzene, Trichloroethylene (TCE), Pesticides, Radiation, Nitrogen Dioxide (NO![]() ), and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH). The review finds an overlap between dietary and air pollution factors. For example, both the consumption of smoked or grilled meat and exposure to PAHs are identified as risk factors for breast cancer. The review also notes that pesticides in food and industrial pollutants like benzene and radionuclides can contribute to breast cancer risk. This review is limited by the lack of information on the interaction of air pollution and diet, and how they affect breast cancer. The way that this was addressed is by expanding the search method to include credible information from other methods of publication such as peer-reviewed articles and credible journalism. Additionally, one of the main findings is that more research needs to be done to analyze a link. This review highlights the importance of mitigating these risks through policy recommendations and public health campaigns. These include: Regulations to reduce air pollution, public health campaigns promoting healthy food consumption, reduced intake of processed foods, consumer protections and standards that give alerts to proximity to sources of pollution, and further research to develop effective guidelines for breast cancer prevention. This review concludes that a two-pronged strategy, focused on both dietary changes and air quality control, is essential to reduce breast cancer incidences and improve public health outcomes for women.

), and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH). The review finds an overlap between dietary and air pollution factors. For example, both the consumption of smoked or grilled meat and exposure to PAHs are identified as risk factors for breast cancer. The review also notes that pesticides in food and industrial pollutants like benzene and radionuclides can contribute to breast cancer risk. This review is limited by the lack of information on the interaction of air pollution and diet, and how they affect breast cancer. The way that this was addressed is by expanding the search method to include credible information from other methods of publication such as peer-reviewed articles and credible journalism. Additionally, one of the main findings is that more research needs to be done to analyze a link. This review highlights the importance of mitigating these risks through policy recommendations and public health campaigns. These include: Regulations to reduce air pollution, public health campaigns promoting healthy food consumption, reduced intake of processed foods, consumer protections and standards that give alerts to proximity to sources of pollution, and further research to develop effective guidelines for breast cancer prevention. This review concludes that a two-pronged strategy, focused on both dietary changes and air quality control, is essential to reduce breast cancer incidences and improve public health outcomes for women.

KeyWords: Breast Cancer; Diet; Air Pollutants; Pesticides in Food; Policy recommendations;

Introduction:

Breast Cancer is a type of cancer that affects the breast tissue, with two main types1. The first main type is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which is a pre-cancer that begins in the milk duct but still has not spread to the rest of the breast2. The second main type are invasive breast cancers, the two most prevalent invasive breast cancers are invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). IDC is the most common type of breast cancer with 80 percent of women having this form of cancer. It starts in the cells that line the milk duct, before breaking the duct walls and spreading to other parts of the body. The other most prevalent type of invasive breast cancer is ILC, which starts in the breast lobule before metastasizing to other parts of the body. It is also more likely to affect both breasts than one breast, compared to other forms of invasive breast cancer3. Recognizing the various types of breast cancer is essential for understanding their origins and progression.

There are many risk factors for breast cancer; however, in this paper, risk factors that are included under diet and air pollution will be analyzed. This is needed as both diet and air pollution are risk factors. The risk factors analyzed as a diet are: meat consumption, smoked meat consumption, and dietary fiber consumption. These affect breast cancer by changing the production of estrogen, creating DNA damage, creating carcinogenic chemicals, and changing insulin regulation. The risk factors understood as air pollution are: Nitrogen dioxide (NO2), pesticides, trichloroethylene (TCE), benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), radiation, and environmental tobacco smoke(ETS). These air pollutant risk factors generally affect breast cancer by being endocrine disruptors, hormone disruptors or by causing mutations in DNA, leading to breast cancer.

There are very few studies found via the PubMed search that combined both diet and air pollution into one paper. The aim of this literature review is to compile an in-depth synthesis that examines the effect of diet and air pollution on breast cancer. Implications of this research include having a better understanding of the role of both diet and air pollution on breast cancer, a subject that has very minimal papers combining these effects, this review is meant to help bridge the gap in current knowledge on the way these risk factors interact, which would be important in understanding how breast cancer forms among certain populations.

Methods

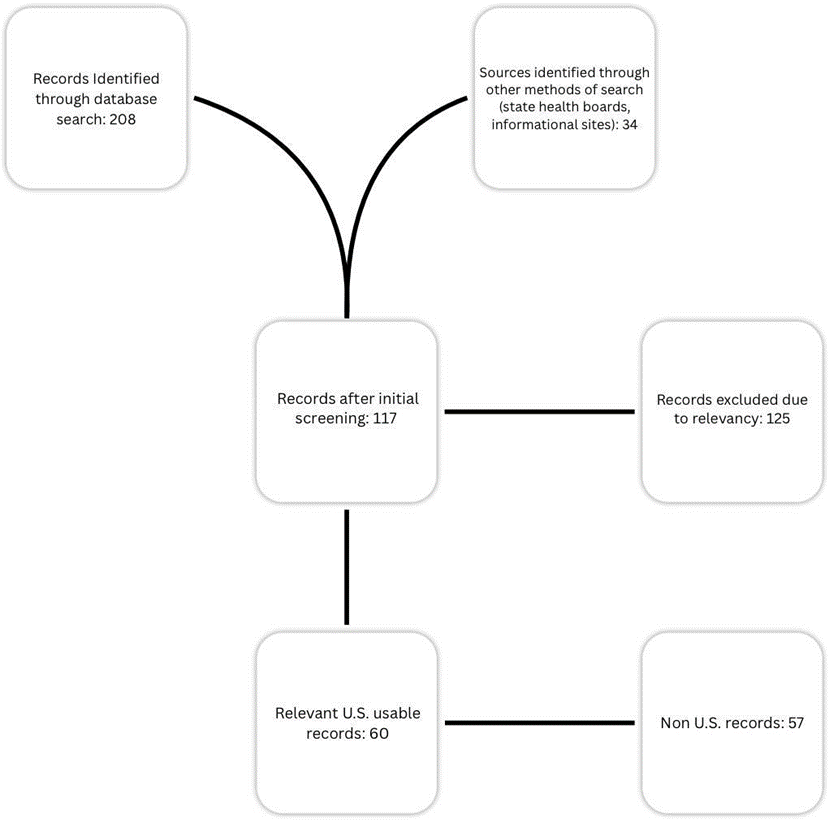

Some of the evidence for this review was collected from keyword searches on the PUBMED database with the prompt: air pollution diet and breast cancer, yielding 35 results of which were adjusted to find papers focusing on US women, leading to an analysis of 15 papers, additionally 173 extra papers were found by looking at related and relevant papers. This narrowing to only include US women was to have concise results that were not muddled by other countries’ air and food standards, such as the harsher regulations in European countries (where other studies on this topic were conducted) and higher air pollution in Iran and Southeast Asia (where other studies on air pollution were conducted). Additional academic information was sourced from identifying related papers and commonly cited papers, which was then used to give a better understanding of the individual effects of diet and air pollution on breast cancer. General information about risk factors were sourced from trusted websites, such as the CDC, state departments of health, the NIH, and other trusted sources. Data from the PUBMED sources was extracted by looking at the relevant sections regarding the intersection between diet, air pollution, and breast cancer.

Additional information regarding the conflux of diet and air pollution of breast cancer came from credible publications identified by researching the publication and the author. Most of the information is from the PUBMED databases, and other academic publications. This information was also regarding individual risk factors. The information in this review was organized into individual risk factors, before discussing the intersection of the risk factors.

Literature Review

Environmental Tobacco Smoke:

Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS), commonly known as secondhand smoke or passive smoke, is the byproduct of burning tobacco products and includes smoke exhaled by smokers and emitted from the burning end of tobacco products. While ETS is considered less harmful than direct smoking, it still poses serious health risks and is classified as a carcinogen, containing 43 known carcinogenic compounds4, particularly affecting occupationally exposed workers5. A possible reason as to why ETS is so carcinogenic is that it may play a role in reducing methylation at the CCND2 gene6, which plays a key role in regulating cell cycle progression 7. ETS is constantly a risk factor for breast cancer8, with some evidence showing a 68-120% OR statistically significant increase in the risk of developing breast cancer9 in young premenopausal women. Another estimate of the risk of ETS found that extremely high ETS exposure can lead to a statistically significant OR of 3.2 (95% CI 1.7-5.9) in the chance of developing breast cancer, which was a population based case-control study10. Yet ETS doesn’t proportionally affect all US women. Native American women are associated with higher levels of ETS exposure. Exposure was also significantly higher with women who had 8th grade level education or high school education, and with women who worked at jobs that allow smoking11. Additionally, premenopausal women (women < 50 years old) have a greater risk of breast cancer compared to postmenopausal women (women >= 50) when factoring in the association between breast cancer and ETS9, this study also found that people exposed to ETS had 68% higher odds of developing breast cancer than those not exposed this study is more reliable than the one that found a 3.2 multiplier10, as it analyzes more people controlled for exposure, and included people of all socio-economic status in California.

Benzene

Benzene is a colorless liquid at room temperature, its vapor is heavier than air leading it to sink into low lying areas12. It is a commonly used chemical, mostly used in industrial processes to make plastics, resins, synthetic fibers, lubricants, dyes, and more13. Benzene has long been known as a carcinogenic factor, yet it is still a widely used chemical14. Benzene has also been suspected as a risk factor for breast cancer15. High exposure to benzene is seen with an increase in the odds of developing breast cancer, suggesting that it can be a risk factor for breast cancer16. In another study, proximity to a Benzene emitting source was seen with an increase in breast cancer risk, with benzene emissions and breast cancer risk found to have a greater risk at 1km away from the source. With a statistically significant increase of 106% (95% CI: 1.34–3.17) in the odds of developing breast cancer17; however, like with ETS not everyone has the same exposure with lower income Americans having a far higher exposure to carcinogenic air pollutants18. With consistent findings showing that lower income residents had higher exposure to benzene18.

Trichloroethylene (TCE)

TCE is a chemical most commonly used in metal degreasers, but can also be found in many consumer products such as wood finishes, adhesives, paint removers, and stain removers19. TCE may be found in the environment near where it was produced as it takes a long time to break down20. Because of this, TCE is a very potent chemical when it comes to increasing the odds of cancer. TCE is associated with a higher level of DCIS within a 10km radius from the point of emissions, when compared to those not exposed17. Although there is no clear risk pattern across distances from source of pollution21, or any clear increased risk with the increased dosage8. Additional research must be done about the role TCE plays in the development of breast cancer. Yet there is still a general consensus among the literature that TCE does in fact affect breast cancer development risk in some way.

Pesticides

Pesticides are a wide field of various carcinogenic chemicals, including dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT), aldrin, dieldrin, and chlordane. These are all known or suspected carcinogenic compounds. There are many reasons why these chemicals could cause cancer, the main ones are disrupting hormones, damaging DNA, inflaming tissues and turning genes on or off22. Their specific effect on breast cancer can possibly be linked back to their impact as endocrine disruptors23. Which is why with all of the aforementioned pesticides there is some form of increased risk with breast cancer. With DDT, women who were exposed to the pesticide under the age of 14 had a significant increase in the odds of developing breast cancer, and those in the highest exposure bracket had a nearly 5 times increase in risk of developing breast cancer8. However, other research has come up finding no real correlation with organochlorine pesticides like DDT and breast cancer, although that research was too recent to analyze direct use of DDT before its ban24. Additionally the risk of developing breast cancer goes up when looking at aldrin, dieldrin, and chlordane, with a relative risk of 1.9, 2.0, and 1.7 respectively8. Additionally women under age 14 when first exposed to DDT had a statistically significant increased risk of breast cancer with increasing levels of serum p,p’-DDT. Women in the highest exposure category had a fivefold significant increase of risk of breast cancer8. The reference8 was prioritized because of its better ability to measure the effects of pesticides on breast cancer.

Radiation

Radiation has long been associated with multiple types of cancer, including breast cancer. Radiation, specifically stronger forms of radiation can damage DNA, leading to faulty cell production and therefore cancer25. There is a strong link between Ionizing radiation and breast cancer, with a weaker suspected link for non-ionizing radiation8, with consistent research finding that there is a link between ionizing radiation and breast cancer24. Unfortunately most studies of direct effects of ionizing radiation come from atomic bomb survivors which is outside the purview of this review26. Yet there is still an occupational risk of exposure, coming from radiology department workers and workers at nuclear plants; however, this is usually in small doses under the limit before it becomes detrimental27. Greater occupational risk also leads to higher rates of mortality, alongside a linear dose-response association28. With non-ionizing radiation, EMF fields are seen as a suspected contributory factor in the risk of developing breast cancer28; however, while there is an increase in the chance of developing breast cancer it is nonsignificant and drastically decreases the lower a woman’s EMF exposure is8. The association with EMF and the rate of breast cancer development is something that needs further research to determine the link between the two.

NO2

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) is a common air pollutant that is produced from the combustion of fossil fuels29. An increase of risk by 10% in estrogen receptor positive(ER+) and progesterone receptor positive(PR+) when increased NO2 is factored in30. With another 2017 study finding that there was an increase for women with 10 years or more of any type of exposure, the adjusted OR was 1.17 (95% CI: 0.93-1.46) in the odds of getting breast cancer in ER+ and PR+ type breast cancer31. Additionally a recent meta analysis of 13 papers concluded that there was an increased risk associated with NO232. There is seemingly a clear link between the rate of breast cancer development and NO2. Although what is not clear is why NO2 affects breast cancer development, with there being two convincing theories. The first being that NO2 may have cancer causing properties33, NO2 has been seen as having carcinogenic properties as Hamra et al finds there to be a strong relationship between NO2 and lung cancer34, suggesting that NO2 is carcinogenic, therefore could directly affect breast cancer. The second theory being that NO2 may increase breast density, which is a major risk factor for breast cancer35.

Evidence for this comes from multiple studies, one of which found an increase of 1 unit of NO2(ppb) lead to a 4% increase in the chance of having higher breast density36. With all this in mind, there is seemingly a clear connection between NO2 and breast cancer.

PAH

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons(PAH) are a chemical that is naturally found in crude oil, gasoline, and coal. They can also be produced as a byproduct of the burning of: coal, oil, gas, wood, garbage, and tobacco37. Long term exposure to PAH can be extremely detrimental to someone’s health, long term exposure can lead to cataracts, kidney and liver damage, and jaundice38. With all of these adverse effects on public health it’s no wonder how PAHs could also affect breast cancer. PAH exposure leads to constantly being linked with increased risk of breast cancer24. It’s speculated that exposure while young also leads to higher risk of developing breast cancer in postmenopausal women, with a nonsignificant increase of 142% chance in development, with women who were exposed to higher dosages being more likely to develop breast cancer, however this dose response trend was not identified in premenopausal women8. While it is established that PAHs have some impact on the development of breast cancer, the exact mechanism is still undetermined; however, a common theory is that the binding of the PAH metabolites to certain genes (like the CYP1A1 gene) and segments of DNA leads to the chemical becoming cariogenic39‘10. Another theory as to how PAHs affect breast cancer is through gene methylation, with findings that increased PAH intake could lead to hypo methylation in promoter genes for breast cancer, possibly attributing them as a risk factor.

Meat Consumption

With meat consumption up more than ever40 it is important to acknowledge the role that the consumption of meat may play in elevating the risk of breast cancer. Meat is a huge source of dietary fat41 and dietary fat has long been known as a factor of breast cancer42. How does meat affect the odds of developing breast cancer? The literature finds a roughly 13% increase in the rate of developing breast cancer with a diet high in meat43. Additionally, compared with low intake, high intake of grilled/barbecued and smoked meat prior to diagnosis was associated with a 23% increased hazard (HR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.46)44, which is a statistically significant. The mechanism that propels this is likely the formation of aromatic amines and PAHs which are both formed through the pyrolysis of fat10.

Nutrition

Dairy intake

Dairy products are products that contain some form of dairy, most commonly from a cow’s milk, but can be made out of any animal milk. Dairy intake is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer in women45. With another meta analysis finding that dairy products excluding milk and cheese lower a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer46. This is an interesting contrast between milk, cheese, and breast cancer, as other dairy products seemingly reduce the rate of developing breast cancer. A possible mechanism as to why milk and cheese are the sole dairy products that lead to an increase in breast cancer, is that both contain a relatively high fat content47, as fat consumption is a risk factor for breast cancer.

Produce consumption:

For the purposes of this review, produce is defined as fruits and vegetables. Both are seen as protective factors to the development of breast cancer. Diets that are high in produce led to a significant 9% decrease in the chance of developing breast cancer48. The possible mechanism as to why increased consumption of fruits and vegetables leads to lower risk of breast cancer could be because a produce heavy diet contains significant amounts of dietary fiber46. Dietary fiber has been known to reduce the chance of developing breast cancer. The mechanism in which dietary fiber is able to reduce the chance of developing breast cancer is likely its ability to repair DNA damage49.

Interaction of diet and air pollution

With all these factors, there is significant overlap between dietary factors and Air pollution. A key example of this is the relationship between PAH’s and cooked (grilled and smoked) meat consumption. The literature states that both are risk factors for breast cancer. Smoked meat produces PAHs as a byproduct, these are formed from the fat turning to smoke. The smoke then settles on the meat, creating a combination of risk factors10. Meaning that certain levels of PAHs are emitted and consumed with the consumption of smoked or grilled meat6. As the consumption of smoked or grilled meat rises, there is a heightened exposure to PAHs, which can be averted by limiting the intake of smoked meats. Additionally, smoked meat consumption has been linked with decreased DNA methylation possibly suggesting that PAHs forming on smoked or grilled meat could lead to their carcinogenic properties6‘10‘9.

There is also a significant influence of pesticide on food. While pesticide is commonly used to insure higher yields through preventing pests from lowering production, it is a highly carcinogenic compound, as stated early. While being highly carcinogenic, many pesticides are still widespread in their use. This can affect many different types of food with 75% of fresh produce containing trace amounts of potentially harmful pesticides, with 95% of the top 12 most heavily polluted produce containing trace amounts of carcinogenic pesticides50. While there are amounts of carcinogenic pesticides on commonly consumed produce, the vast majority of it is below the tolerance51. While the majority of foods are below the threshold for pesticides, reducing intake of foods grown with pesticides has been found to have a slight impact in decreasing the odds of developing breast cancer52. There is likely a small non-significant difference between the role of pesticides in commonly consumed products on breast cancer; however, further research should be conducted in order to truly understand the residual role of pesticides on diet and breast cancer. While pesticides in food can be a cause for concern, they are not the only form of pollution that can enter our food.

Industrial pollutants such as radionuclides or benzene can enter food through their industrial production and discharges53. Both are highly carcinogenic forms of air pollution. With Benzene, higher levels of exposure leads to higher rates of developing breast cancer, meaning there could be an increase in developing breast cancer with higher benzene contaminated foods. Benzene seemingly is more potent the closer in proximity to the source of production17.

Possibly opening up policy decisions that can both limit the contamination of foods and limit human exposure to benzene, thus decreasing breast cancer rates and the rate of other cancers benzene affects. With radionuclides (which are unstable elements that release ionizing radiation)54, There is a possible carcinogenic risk. This risk may come from the exposure of food to ionizing radiation. While that does sound scary, there is no scientific basis that food irradiation causes cancer or any long term health risk55.

One of the key ways that diet and air pollution cause breast cancer is the manipulation of estrogen production. For example, meat can affect estrogen in numerous ways it can affect if through the consumption of dietary fat, which leads to increased estrogen production56.

Additionally meat consumption also may influence estrogen levels because of sex steroid treated animals, thus directly putting estrogen in a body57. This worsens the body’s natural ability to produce estrogen, thus making it even more susceptible to other mechanisms that affect estrogen production, such as PAHs and Benzene58. Specific PAHs such as benzopyrene (BaP) and dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA) have been shown to alter estrogen metabolism, leading to increased formation of estrogen metabolites that have strong affinity for estrogen receptors and potentially promote cancer. This is especially worse when the body’s natural estrogen levels have been tainted over years by the overconsumption of meat/smoked meats with PAHs, leading to higher estrogen and a worse hormonal imbalance, leading to higher rates of ER+ breast cancer58. In addition to diet playing an increased role in terms of estrogen production, it can actually reduce estrogen, through dietary fiber59 which can play a preventive effect against the various estrogen increasing PAH’s and benzene alongside certain pesticides, as it is able to regulate the production of estrogen.

Additionally, many pesticides are xenobiotics that interact with metabolizing enzymes. Some can inhibit enzymes like aromatase, altering estrogen biosynthesis, while others are metabolized into active forms that act as endocrine disruptors or genotoxic agents. This also occurs with Benzene. Benzene is metabolized by CYP2E1 into reactive intermediates that cause genotoxicity and lead to malignancy60. In addition to this chemicals produced by smoked meat are metabolized by P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1) into highly reactive epoxides that can bind to DNA, forming adducts that lead to mutations. Some PAHs like BaP can also be bioactivated by human intestinal microbiota into estrogenic metabolites, which may increase health risks61.

This consumption of smoked meat alongside air pollution creates high levels of genotoxicity and inflammation leading to higher rates of breast cancer compared to each individual risk factor or compared to someone who has not been exposed to either type of risk factor.

Additionally to the effect of air pollution on diet, there is a protective factor to diet and avoiding the adverse effects of certain pollutants. For instance, the correlation between particular fruits and their impact on DNA repair, which has the potential to prevent DNA mutations triggered by air pollution. Food high in dietary fiber, helps mitigate damage done to DNA by air pollution49, while also reducing the chance of breast cancer. This involvement in DNA repair could potentially alleviate types of DNA damage resulting from various forms of air pollution, thereby demonstrating a protective factor in the role of diet in mitigating the effects of air pollution on breast cancer.

While there is some research on the effect of air pollution on diet and vice versa, there is still no concrete link between the cumulative effect that they both have on each other and how that influences breast cancer. Large amounts of research still need to be conducted on how these two risk factors interact with each other, as the various risk factors mentioned in both air pollution and diet have a large impact on the development of breast cancer. This review is limited by the current number of papers on the topic, and is attempting to fill a gap in knowledge.

| Risk Factor | Type (Diet/Air Pollution) | Effect on Breast Cancer Risk | Mechanism | Intersection with Other Factors |

| Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) | Air Pollution | ↑ Risk (68-120% increase) | Reduces methylation at CCND2 gene; DNA damage | Higher exposure in lower-income and Native American women; interacts with dietary carcinogens |

| Benzene | Air Pollution | ↑ Risk (106% increase near sources) | Endocrine disruption; DNA damage | Higher exposure in lower-income communities; can contaminate food |

| Trichloroethylen e (TCE) | Air Pollution | ↑ Risk (associated with DCIS) | Possible endocrine disruption | No clear dose-response; needs further research |

| Pesticides (DDT, Aldrin, etc.) | Air Pollution & Diet (food residues) | ↑ Risk (up to 5x with DDT) | Endocrine disruption; DNA damage | Higher exposure in conventional produce; interacts with dietary fat intake |

| Radiation (Ionizing/Non-io nizing) | Air Pollution | ↑ Risk (strong for ionizing) | DNA damage; mutations | Occupational exposure; food irradiation effects minimal |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) | Air Pollution | ↑ Risk (10-13% for ER+/PR+) | May increase breast density; carcinogenic | Linked to traffic emissions; interacts with dietary antioxidants |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Air Pollution & Diet (grilled/smoke d meat) | ↑ Risk (142% in postmenopau sal) | DNA adducts; estrogen disruption | Formed during meat cooking; overlaps with dietary PAH intake |

| Meat Consumption (High Intake) | Diet | ↑ Risk (13%) | Increased estrogen; dietary fat | Smoked/grilled meat produces PAHs |

| Dairy (Milk & Cheese) | Diet | ↑ Risk (high-fat products) | Hormonal influence (estrogen/prolacti n) | Contrasts with protective effects of low-fat dairy |

| Produce (Fruits & Vegetables) | Diet | ↓ Risk (9% reduction) | Antioxidants; dietary fiber repairs DNA | Mitigates pollution-induced DNA damage |

| Dietary Fiber | Diet | ↓ Risk | Reduces estrogen; enhances DNA repair | Counters effects of PAHs and pesticides |

Bradford Hill Criteria

1. Strength of association:

PAHs from Grilled Meat: Strong association (23% increased risk with high intake of smoked/grilled meat). Benzene Exposure: Significant (106% increased risk near emission sources). Pesticides: High-risk increase (up to 5x with DDT exposure in childhood). NO₂ & Breast Cancer: Moderate but consistent (10-13% increased risk for ER+/PR+ tumors). Dietary Fiber: Protective (9% reduction in breast cancer rates with high intake). Conclusion: Some factors show a strong association (PAH’s, Benzene, Pesticides), while others (NO2, Dairy) show a moderate but consistent linkage.

2. Consistency:

PAHs & Meat Consumption: Consistently linked in multiple studies (smoked meat to PAH exposure to breast cancer).NO₂ & Breast Cancer: Meta-analyses confirm increased risk (13 studies).Pesticides: Mixed but strong evidence for DDT, aldrin, dieldrin. Dietary Fiber & Protection: Repeatedly observed in cohort studies. Conclusion: High consistency for PAHs, NO2, Pesticides, and Dietary Fiber.

3. Specificity:

PAHs & Grilled Meat: Specific to cooking methods (pyrolysis of fat). Benzene & Industrial Proximity: Stronger near emission sources. Pesticides & Hormone-Positive Tumors: Some specificity for ER+ cancers. Limitation: Breast cancer is multifactorial, so no single factor is fully specific. Conclusion: Moderate specificity for PAHs, benzene, and pesticides.

4. Temporality:

Childhood Pesticide Exposure leads to Later Breast Cancer: Evidence supports long latency.Lifetime NO₂/PAH Exposure leads to Postmenopausal Breast Cancer: Some studies track exposure over decades. Dietary Changes (e.g., fiber intake) leads to Reduced Risk: Longitudinal studies support. Limitation: Many studies are cross-sectional (cannot confirm temporality). Conclusion: Supported for pesticides, PAHs, and dietary fiber but needs more prospective studies.

5. Biological Gradient (Dose-Response):

PAHs: Higher grilled meat intake leads to higher risk (dose-response observed).Benzene: Proximity to emission sites leads to higher risk.Pesticides (DDT): Higher exposure leads to 5x risk. Dietary Fiber: Higher intake leads to lower risk. Conclusion: Clear dose-response for PAHs, benzene, pesticides, and fiber.

6. Plausibility:

PAHs: DNA adducts, estrogen disruption (CYP1A1 activation).Benzene: Genotoxicity, oxidative stress.Pesticides: Endocrine disruption (estrogen mimicry). Dietary Fiber: Reduces circulating estrogen, enhances DNA repair. Conclusion: Strong biological plausibility for all major interactions.

7. Coherence:

PAHs & DNA Damage: Consistent with carcinogen mechanisms. Benzene & Leukemia: Known carcinogen; breast cancer link is plausible. Pesticides & Hormonal Cancers: Fits endocrine disruptor theory. Conclusion: Highly coherent with existing cancer biology.

8. Experiment (Interventional Evidence):

Dietary Interventions (Mediterranean effect): Lower breast cancer risk. Air Pollution Policies (Clean Air Act): Reduced PM2.5 leads to lower cancer rates. Limitation: Few randomized trials on diet-pollution interactions. Conclusion: Limited but supportive indirect evidence.

9. Analogy:

PAHs: Known lung carcinogens → plausible breast cancer link. Benzene: Causes leukemia → may also affect breast tissue. Conclusion: Strong analogy with other carcinogens.

Summary of Causality Assessment

| Bradford Hill Criterion | Support for Causality? |

| Strength of Association | Moderate-Strong |

| Consistency | High |

| Specificity | Moderate |

| Temporality | Partially Supported |

| Biological Gradient | Strong |

| Plausibility | Strong |

| Coherence | Strong |

| Experiment | Limited |

| Analogy | Strong |

Final Conclusion

Nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) – Associations are present but small: each 10-ppb increase in long-term NO₂ is linked to only a few-percent rise in breast-cancer risk. PAH-rich cooked meat – Evidence is mixed; the observed links are modest and do not consistently strengthen with higher intake, so results should be interpreted cautiously. DDT and benzene timing – The clearest signals come from exposures early in life (DDT) and from living or working very near active benzene sources; later or more distant exposures show weaker effects. Policy implications – Cleaner-air regulations remain vital public-health tools, yet any breast-cancer-specific benefit is inferred from broader evidence and has not been definitively proven.

Discussion

The interplay between dietary habits and air pollution is deemed a pivotal aspect in the acquisition of knowledge pertaining to the risk of breast cancer in women. The significance of both factors in the genesis of the disease is indubitable, necessitating a comprehensive approach encompassing prevention and health promotion.

Effects of Air Pollution on Breast Cancer

Several studies have already mentioned that air pollution is associated with the heightened incidence of breast cancer. For instance, an increased risk for breast cancer has also been associated with NO2 exposure, with evidence indicating that higher levels of NO2 increase the risk 10-13% for ER+ and PR+ breast cancer30.

Notably, various carcinogenic air pollutants, such as benzene, TCE, and PAHs, have been linked to increase the risk of breast cancer62. To be specific, the emissions of benzene have been significantly known to increase chances of breast cancer in people when they live near high-level emissions sources62. Moreover, PAHs produced mainly from burning fossil fuels and methods of cooking have also been linked with carcinogenic effects, especially on women during their formative years of life, hence leading to a greater risk of postmenopausal breast cancer10.

Nutritional Factors

Diet also plays an important role in the modulation of breast cancer risk. A diet rich in fruits and vegetables, along with healthy fats and fibers, has been associated with reduced risks of breast cancer. Nutritional components like carotenoids from colorful fruits and vegetables have been shown to protect against specific kinds of breast cancers, likely for their antioxidant properties.

Diet-Air Pollution Interactions

Amazingly, interactive effects exist between diet and air pollution with respect to risk for breast cancer. The fact that food may contain carcinogenic compounds, such as pesticides and chemical contaminants, raises the ill effects of air pollution. For instance, pesticide residues on produce, a common occurrence, along with pesticides emitted into the environment can work together to raise cancer risk50. The literature indicates that a reduction in pesticide exposure is related to a reduction in the odds of breast cancer, both in diet and the air. Reducing pesticide exposure through dietary choices may mitigate some of the risks associated with environmental pollutants63.

In addition to pesticides, the use of processed and grilled meats, which generate PAHs during cooking, is a strong intersection of diet and pollutant exposure. The overconsumption of grilled meats is a risk factor for breast cancer, this is because of the formation of PAHs after the pyrolysis of fat, creating two risk factors10. The first one being the consumption of meat itself, and the second being the pollution that cooking meat produces.

In addition, dietary patterns may modify the pathways through which air pollutants act on breast cancer risk, for example, by genetic methylation or disruption of hormonal mechanisms. Some nutrients may enhance DNA repair or reduce inflammation and, through these mechanisms, might reduce damage from air pollutants.

Policy Recommendations

The twin problems of diet and air pollution necessitate a multilayered policy approach. Protection of the public health through prioritized reduction of air pollutants in areas with highly concentrated traffic and industry is to be addressed by regulations. Stringent implementation of air quality standards (such as monitoring pollution from producers and penalties for producers who exceed the maximum, which should be low like 20 micrograms per meter3) for pollutants such as PM2.5 and NO₂ has been found to significantly reduce the risk of breast cancer linked to environmental exposures. These pollutants are known to cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage in breast tissue, all of which can contribute to cancer development. By reducing ambient concentrations through regulatory action, public health agencies can help minimize long-term exposure and lower the incidence of environmentally induced breast cancer.

Public health campaigns advocating healthy food consumption, especially organic produce and diminished processed foods intake, are also important. Easy access to nutritional education can help empower communities, particularly those suffering from both air pollution and the deprivation of healthy foods. In addition to these, significantly more research needs to be done on the role of air pollutants on diet, alongside analyzing how diet may play a protective role in preventing the harms of air pollution. In addition, to public health campaigns, restrictions, and research. Limiting the distance of a production facility of a carcinogenic chemical from residential areas and food production centers (such as farms, grocers, and sorting facilities), will also likely reduce the chance of development of breast cancer among certain populations, especially low income and marginalized communities.

Another policy recommendation is to put increased limitations on where certain industrial areas can be placed, especially certain industrial sites that produce any of the aforementioned air pollutants, this would put a distance between homes and production sites. Additionally better safeguards are needed for occupationally exposed workers, perhaps limiting their exposure to certain chemicals to a certain number per shift, along with better air standards at industrial sites themselves.

In addition to all of this, better consumer protections should be created to allow the consumer to know the risks of certain cooking styles and consumption. A key way to do this is by better labeling of pesticides themselves and how to properly use them, alongside having a regulator cap on sales of pesticides to individual consumers. Additionally, allowing consumers to know the pesticide use in food could also create a reduced risk of breast cancer, by allowing consumers to understand the amount of pesticides they are consuming. In addition to this, another consumer protection could be alerting homebuyers of their proximity to a polluting site. Allowing each consumer to make a decision that is right for them.

Conclusion

Finally, it is diet and air pollution interacting with each other regarding risk for breast cancer that calls for urgent research with concomitant interventions. While air quality improvements decrease the associated risk with environmental exposures, fostering healthier dietary practices may confer protective benefits and overall improved public health outcomes. Further research on breast cancer incidence and survival at other cancer sites is needed, as this will enable us to develop effective guidelines about specific interventions for breast cancer prevention. In general, a two-pronged strategy-one focusing on changes in dietary habits, and another on control of air quality-may hold the key to slashing the incidence of breast cancer and offering a healthier future to women from coast to coast.

References

- American Cancer Society, “What Is Breast Cancer?”, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/what-is-breast-cancer.html, (2021) [↩]

- American Cancer Society, “Invasive Breast Cancer”, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/types-of-breast-cancer/invasive- breast-cancer.html, (2021) [↩]

- National Cancer Institute, Secondhand Smoke “(Environmental Tobacco Smoke)”, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances/secondhand-smo ke#:~:text=Secondhand%20tobacco%20smoke%20is%20the,identified%20in%20second hand%20tobacco%20smoke. 2024 [↩]

- https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/91-108/default.html#:~:text=The%20National%20Institute%20for%20Occupational%20Safety%20and%20Health%20(NIOSH)%20has,carcinogenic%20to%20occupationally%20exposed%20worker, 1998 [↩]

- Brownson RC, Eriksen MP, Davis RM, Warner KE. Environmental tobacco smoke: health effects and policies to reduce exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:163-85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.163. PMID: 9143716. [↩]

- White AJ, Chen J, Teitelbaum SL, McCullough LE, Xu X, Hee Cho Y, Conway K, Beyea J, Stellman SD, Steck SE, Mordukhovich I, Eng SM, Beth Terry M, Engel LS, Hatch M, Neugut AI, Hibshoosh H, Santella RM, Gammon MD. Sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are associated with gene-specific promoter methylation in women with breast cancer. Environ Res. 2016 Feb;145:93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.11.033. Epub 2015 Dec 6. PMID: 26671626; PMCID: PMC4706465. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- https://medlineplus.gov/download/genetics/gene/ccnd2.pdf [↩]

- Clapp RW, Jacobs MM, Loechler EL. Environmental and occupational causes of cancer: new evidence 2005-2007. Rev Environ Health. 2008 Jan-Mar;23(1):1-37. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2008.23.1.1. PMID: 18557596; PMCID: PMC2791455. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Mark D. Miller, Melanie A. Marty, Rachel Broadwin, Kenneth C. Johnson, Andrew G. Salmon, Bruce Winder, Craig Steinmaus, The association between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and breast cancer: A review by the California Environmental Protection Agency, Preventive Medicine, Volume 44, Issue 2, 2007, Pages 93-106, ISSN 0091-7435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.015(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/artic le/pii/S0091743506003410) [↩] [↩] [↩]

- DeBruin LS, Josephy PD. Perspectives on the chemical etiology of breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2002 Feb;110 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):119-28. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s1119. PMID: 11834470; PMCID: PMC1241154. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Stamatakis KA, Brownson RC, Luke DA. Risk factors for exposure to environmental tobacco smoke among ethnically diverse women in the United States. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002 Jan-Feb;11(1):45-51. doi: 10.1089/152460902753473453. PMID: 11860724 [↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Benzene, https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/benzene/basics/facts.asp, 2024 [↩]

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Benzene, https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/chemical/benzene.htm#:~:text=Benzene%20is%20a%20c hemical%20that,lubricants%2C%20dyes%2C%20and%20more, 2024 [↩]

- https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=37&toxid=14#:~:text=Exposure%20to%20benzene%20has%20been,carcinogen%20(can%20cause%20cancer) [↩]

- Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, Bezene, https://www.bcpp.org/resource/benzene/, 2019 [↩]

- Fenga C. Occupational exposure and risk of breast cancer. Biomed Rep. 2016 Mar;4(3):282-292. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.575. Epub 2016 Jan 21. PMID: 26998264; PMCID: PMC4774377. [↩]

- Jessica M. Madrigal, Caroline N. Pruitt, Jared A. Fisher, Linda M. Liao, Barry I. Graubard, Gretchen L. Gierach, Debra T. Silverman, Mary H. Ward, Rena R. Jones, Carcinogenic industrial air pollution and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the National Institutes of Health AARP Diet and Health Study, Environment International, Volume 191, 2024, 108985, ISSN 0160-4120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108985. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412024005713) [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Larsen K, Rydz E, Peters CE. Inequalities in Environmental Cancer Risk and Carcinogen Exposures: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 May 4;20(9):5718. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20095718. PMID: 37174236; PMCID: PMC10178444. [↩] [↩]

- Minnesota Department of Health, Trichloroethylene (TCE) and Your Health, https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/hazardous/topics/tce.html, 2024 [↩]

- National Cancer Institute, Trichloroethylene(TCE), https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances/trichloroethylene, 2024 [↩]

- Jessica M. Madrigal, Caroline N. Pruitt, Jared A. Fisher, Linda M. Liao, Barry I. Graubard, Gretchen L. Gierach, Debra T. Silverman, Mary H. Ward, Rena R. Jones, Carcinogenic industrial air pollution and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the National Institutes of Health AARP Diet and Health Study, Environment International, Volume 191, 2024, 108985, ISSN 0160-4120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108985.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412024005713) [↩]

- Pesticide Action and Agroecological Network, Pesticides and Cancer, https://www.panna.org/resources/pesticides-and-cancer/#:~:text=Pesticides%20%26%20c ancer,to%20these%20chemicals%20is%20widespread [↩]

- Carolina Panis, Bernardo Lemos, Pesticide exposure and increased breast cancer risk in women population studies, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 933, 2024, 172988, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172988. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969724031358) [↩]

- Brody, J.G., Rudel, R.A., Michels, K.B., Moysich, K.B., Bernstein, L., Attfield, K.R. and Gray, S. (2007), Environmental pollutants, diet, physical activity, body size, and breast cancer. Cancer, 109: 2627-2634. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22656 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- National Cancer Institute, Radiation, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation#:~:text=High%2D energy%20radiation%2C%20such%20as,made%2C%20tested%2C%20or%20used. 2019 [↩]

- Ron E. Ionizing radiation and cancer risk: evidence from epidemiology. Radiat Res. 1998 Nov;150(5 Suppl):S30-41. PMID: 9806607. [↩]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Ionizing Radiation, https://www.osha.gov/ionizing-radiation/health-effects#:~:text=Some%20workers%2C% 20such%20as%20radiology,deterministic%20health%20effects%20to%20occur. 2013 [↩]

- Fenga C. Occupational exposure and risk of breast cancer. Biomed Rep. 2016 Mar;4(3):282-292. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.575. Epub 2016 Jan 21. PMID: 26998264; PMCID: PMC4774377. [↩] [↩]

- Ministry for the environment (NZ), Nitrogen Dioxide, https://environment.govt.nz/facts-and-science/air/air-pollutants/nitrogen-dioxide-effects-health/#:~:text=The%20main%20source%20of%20nitrogen,commercial%20manufacturin g%2C%20and%20food%20manufacturing. 2021. [↩]

- Reding KW, Young MT, Szpiro AA, Han CJ, DeRoo LA, Weinberg C, Kaufman JD, Sandler DP. Breast Cancer Risk in Relation to Ambient Air Pollution Exposure at Residences in the Sister Study Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015 Dec;24(12):1907-9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0787. Epub 2015 Oct 13. PMID: 26464427; PMCID: PMC4686338. [↩] [↩]

- Goldberg MS, Labrèche F, Weichenthal S, Lavigne E, Valois MF, Hatzopoulou M, Van Ryswyk K, Shekarrizfard M, Villeneuve PJ, Crouse D, Parent MÉ. The association between the incidence of postmenopausal breast cancer and concentrations at street-level of nitrogen dioxide and ultrafine particles. Environ Res. 2017 Oct;158:7-15. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.038. Epub 2017 Jun 5. PMID: 28595043. [↩]

- Praud D, Deygas F, Amadou A, Bouilly M, Turati F, Bravi F, Xu T, Grassot L, Coudon T, Fervers B. Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 1;15(3):927. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030927. PMID: 36765887; PMCID: PMC9913524. [↩]

- Amina Amadou, Delphine Praud, Thomas Coudon, Floriane Deygas, Lény Grassot, Mathieu Dubuis, Elodie Faure, Florian Couvidat, Julien Caudeville, Bertrand Bessagnet, Pietro Salizzoni, Karen Leffondré, John Gulliver, Gianluca Severi, Francesca Romana Mancini, Béatrice Fervers, Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide air pollution and breast cancer risk: A nested case-control within the French E3N cohort study,Environmental Pollution,Volume 317,2023,120719,ISSN 0269-7491,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120719.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S0269749122019339) [↩]

- Hamra GB, Laden F, Cohen AJ, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Brauer M, Loomis D. Lung Cancer and Exposure to Nitrogen Dioxide and Traffic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2015 Nov;123(11):1107-12. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408882. Epub 2015 Apr 14. PMID: 25870974; PMCID: PMC4629738. [↩]

- Amina Amadou, Delphine Praud, Thomas Coudon, Floriane Deygas, Lény Grassot, Mathieu Dubuis, Elodie Faure, Florian Couvidat, Julien Caudeville, Bertrand Bessagnet, Pietro Salizzoni, Karen Leffondré, John Gulliver, Gianluca Severi, Francesca Romana Mancini, Béatrice Fervers, Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide air pollution and breast cancer risk: A nested case-control within the French E3N cohort study,Environmental Pollution,Volume 317,2023,120719,ISSN 0269-7491,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120719. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S0269749122019339) [↩]

- Eslami B, Alipour S, Omranipour R, Naddafi K, Naghizadeh MM, Shamsipour M, Aryan A, Abedi M, Bayani L, Hassanvand MS. Air pollution exposure and mammographic breast density in Tehran, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2022;27:28. doi: 10.1265/ehpm.22-00027. PMID: 35786683; PMCID: PMC9283909. [↩]

- Environmental Protection Agency, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2014-03/documents/pahs_factsheet_cdc_2013.pdf, 2013. [↩]

- Illinois Department of Public Health, POLYCYCLIC AROMATIC HYDROCARBONS (PAHs), http://www.idph.state.il.us/cancer/factsheets/polycyclicaromatichydrocarbons.htm#:~:text=Long%2Dterm%20health%20effects%20of,breakdown%20of%20red%20blood%20cell

s. 2009. [↩]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/polycyclic-aromatic-hydrocarbons/pathogenic_changes.html#:~:text=The%20mechanism%20of%20PAH%2Dinduced,to%20deoxyribonucleic%20acid%20(DNA).&text=Some%20parent%20PAHs%20are%20weak,to%20become%20 more%20potent%20carcinogens, 2021. [↩]

- Daniel CR, Cross AJ, Koebnick C, Sinha R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2011 Apr;14(4):575-83. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002077. Epub 2010 Nov 12. PMID: 21070685; PMCID: PMC3045642. [↩]

- Victoria State Department of Health, Dietary Fat, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/fats-and-oils#:~:text=Animal%20products%20and%20some%20processed,to%20increased%20blood%20cholesterol%20 levels. 2024 [↩]

- Uhomoibhi TO, Okobi TJ, Okobi OE, Koko JO, Uhomoibhi O, Igbinosun OE, Ehibor UD, Boms MG, Abdulgaffar RA, Hammed BL, Ibeanu C, Segun EO, Adeosun AA, Evbayekha EO, Alex KB. High-Fat Diet as a Risk Factor for Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2022 Dec 8;14(12):e32309. doi: 10.7759/cureus.32309. PMID: 36628036; PMCID: PMC9824074. [↩]

- RT Journal Article, SR Electronic, T1 Eating more red meat is linked with raised risk of breast cancer, JF BMJ : British Medical Journal, JO BMJ, FD British Medical Journal Publishing Group, SP g3814, DO 10.1136/bmj.g3814, VO 348, A1 Wise, Jacqui, YR 2014, UL https://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g3814.abstract, AB [↩]

- Parada, Humberto et al. “Grilled, Barbecued, and Smoked Meat Intake and Survival Following Breast Cancer.” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 109 (2017): &NA; [↩]

- World Cancer Research Fund, Breast Cancer, https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/cancer-types/breast-cancer/, 2012 [↩]

- De Cicco P, Catani MV, Gasperi V, Sibilano M, Quaglietta M, Savini I. Nutrition and Breast Cancer: A Literature Review on Prevention, Treatment and Recurrence. Nutrients. 2019 Jul 3;11(7):1514. doi: 10.3390/nu11071514. PMID: 31277273; PMCID: PMC6682953. [↩] [↩]

- https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/facts-statistics/research-studies/topics/dairy-produc ts-and-breast-cancer-risk/#:~:text=Some%20researchers%20have%20suggested%20the,ri sk%20%5B1%2D2%5D. [↩]

- Farvid MS, Barnett JB, Spence ND. Fruit and vegetable consumption and incident breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jul;125(2):284-298. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01373-2. Epub 2021 May 18. PMID: 34006925; PMCID: PMC8292326. [↩]

- Croteau DL, de Souza-Pinto NC, Harboe C, Keijzers G, Zhang Y, Becker K, Sheng S, Bohr VA. DNA repair and the accumulation of oxidatively damaged DNA are affected by fruit intake in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010 Dec;65(12):1300-11. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq157. Epub 2010 Sep 16. PMID: 20847039; PMCID: PMC3004740. [↩] [↩]

- Environmental Working Group, EWG’s 2024 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce,(https://www.ewg.org/foodnews/summary.php#:~:text=This%20year%2C%20EWG%20d etermined%20that,percent%20of%20samples%20contain%20pesticides.) 2024. [↩] [↩]

- United States Department of Agriculture, USDA Office of Pest Management Policy Factsheet Pesticide Residues on Fruits and Vegetables (https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/OPMP-Pesticide-Tolerances-Factshe et.pdf, 2021 [↩]

- BreastCancer.org, Eating Unhealthy Foods, https://www.breastcancer.org/risk/risk-factors/eating-unhealthy-food, 2021 [↩]

- Food and Drug Administration, Environmental Contaminants in Food, (https://www.fda.gov/food/chemical-contaminants-pesticides/environmental-contaminant s-food), 2024; DeBruin LS, Josephy PD. Perspectives on the chemical etiology of breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2002 Feb;110 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):119-28. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s1119. PMID: 11834470; PMCID: PMC1241154. [↩]

- World Health Organization, Ionizing radiation and health effects, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ionizing-radiation-and-health-effects#: ~:text=The%20spontaneous%20disintegration%20of%20atoms,ionizing%20radiation%2 0are%20called%20radionuclides, 2023 [↩]

- International Atomic Energy Assocation, Food irradiation: Facts or Fiction, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/magazines/bulletin/bull32-2/3220578 4448.pdf, 2022 [↩]

- Yamamoto A, Harris HR, Vitonis AF, Chavarro JE, Missmer SA. A prospective cohort study of meat and fish consumption and endometriosis risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;219(2):178.e1-178.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.034. Epub 2018 Jun 2. PMID: 29870739; PMCID: PMC6066416. [↩]

- Andersson AM, Skakkebaek NE. Exposure to exogenous estrogens in food: possible impact on human development and health. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999 Jun;140(6):477-85. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1400477. PMID: 10366402. [↩]

- Petralia SA, Vena JE, Freudenheim JL, Dosemeci M, Michalek A, Goldberg MS, Brasure J, Graham S. Risk of premenopausal breast cancer in association with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and benzene. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999 Jun;25(3):215-21. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.426. PMID: 10450771. [↩] [↩]

- Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Wactawski-Wende J, Hovey KM, Whitcomb BW, Howards PP, Perkins NJ, Yeung E, Schisterman EF; BioCycle Study Group. Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Oct;90(4):1061-9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27990. Epub 2009 Aug 19. PMID: 19692496; PMCID: PMC2744625. [↩]

- The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in carcinogen activation and … (n.d.). https://academic.oup.com/carcin/article/39/7/851/4991961 [↩]

- Santella, R.M. 1 Mechanisms and Biological Markers of Carcinogenesis. [↩]

- Jessica M. Madrigal, Caroline N. Pruitt, Jared A. Fisher, Linda M. Liao, Barry I. Graubard, Gretchen L. Gierach, Debra T. Silverman, Mary H. Ward, Rena R. Jones, Carcinogenic industrial air pollution and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the National Institutes of Health AARP Diet and Health Study, Environment International, Volume 191, 2024, 108985, ISSN 0160-4120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108985. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412024005713 [↩] [↩]

- Environmental Working Group, EWG’s 2024 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce, (https://www.ewg.org/foodnews/summary.php#:~:text=This%20year%2C%20EWG%20d etermined%20that,percent%20of%20samples%20contain%20pesticides.) 2024. [↩]