Abstract

Canada’s public healthcare system continues to face well-documented challenges, such as prolonged wait times, inequitable access in remote and underserved communities, and administrative inefficiencies that hinder the delivery of timely, high-quality care. Concurrently, there is a national and global surge in interest around integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and telemedicine to modernize healthcare delivery. Emerging AI applications, such as disease diagnosis, remote monitoring, and virtual hospital care, promise to enhance medical precision, improve patient outreach, and reduce resource burdens. This study employs a comprehensive methodology rooted in secondary document analysis. It integrates data from Canada’s 2025 Watch List on AI in healthcare, policy reports from government and federal agencies, OECD reviews on telemedicine innovation, scholarly meta-analyses on virtual hospital models, and McKinsey’s economic evaluations. The research explores both domestic and international pilot programs to assess efficacy, scalability, and systemic impact. Results reveal that AI-powered tools, such as automated diagnostic assistants and clinical documentation systems, have demonstrated measurable gains in efficiency and accuracy within Canadian pilot sites. Telemedicine, including real-time video consultations and remote patient monitoring, has markedly improved care continuity in underserved regions, particularly when integrated with virtual ward or hospital-at-home programs. However, adoption faces critical obstacles: inconsistent regulation, data privacy vulnerabilities, system fragmentation, infrastructure gaps, and risks of bias in AI algorithms. Innovations in AI and telemedicine hold transformative potential to significantly enhance healthcare access, reduce systemic inequities, and optimize cost-efficiency. Yet, realizing this potential demands strategic reform: building harmonized governance frameworks, investing in digital infrastructure, enhancing provider and citizen tech-literacy, and proactively managing ethical concerns. Without such measures, technology-driven healthcare advancements risk exacerbating existing disparities.

Keywords: AI in healthcare; telemedicine; virtual wards; digital health reform; Canada; health equity; healthcare innovation

Introduction

Background and Context

Canada’s publicly funded healthcare system has long been regarded as a model of universal coverage, yet it faces mounting structural challenges that threaten its sustainability and equity. Physician shortages, particularly in rural and northern regions, have resulted in millions of Canadians lacking consistent access to a family doctor. Wait times for specialist consultations and elective procedures remain among the highest in the OECD1. The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed systemic vulnerabilities, including an overburdened acute care system, fragmented health data infrastructure, and delayed care delivery2. In response to these persistent issues, policymakers, health professionals, and innovators have increasingly turned to digital health technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), telemedicine, virtual care platforms, and remote patient monitoring as potential solutions3. Internationally, health systems are embracing these tools to modernize service delivery, improve outcomes, and reduce cost burdens. In Canada, however, integration remains uneven and policy guidance is still emerging. This context underscores the growing urgency to explore how current technological revolutions can be leveraged to reshape the future of Canadian healthcare.

While the Canada Health Act ensures universal coverage for medically necessary services, the organization, funding, and delivery of care is largely under provincial jurisdiction. This means that each province or territory maintains its own healthcare administration, budget priorities, electronic medical record (EMR) systems, and regulatory approach to health technologies. As a result, the implementation of AI and telemedicine tools has been highly variable across regions4. Provinces like Ontario and British Columbia have made significant strides in piloting AI scribes and virtual wards due to greater digital investment and centralized policy support5‘6, while Saskatchewan or Newfoundland and Labrador face constraints due to limited broadband coverage, smaller pilot funding pools, or slower adoption of digital health standards. Understanding these jurisdictional differences is critical to interpreting why technology diffusion in Canadian healthcare has been uneven—and why national strategies must be adaptable to provincial contexts3‘2.

Problem Statement and Rationale

The healthcare system is at a pivotal moment. Technological advancements in AI and digital infrastructure are rapidly transforming the way care is conceptualized and delivered around the world. Yet, without a coherent national strategy for integrating these innovations, Canada risks falling behind in both efficiency and equity. The urgency lies not only in adopting new technologies but in ensuring that their implementation aligns with the system’s founding values of accessibility, universality, and quality. Understanding the potential and pitfalls of tech-driven reform is therefore critical for informed, forward-looking policy development. Decisions made in this decade will determine whether innovation serves to bridge longstanding gaps or further entrench disparities in care.

Significance and Purpose

This study aims to examine the implications of current and emerging healthcare technologies for systemic reform in Canada. As healthcare delivery becomes increasingly digital, it is vital to assess the structural transformations underway, anticipate future developments, and evaluate the risks and benefits that accompany them. The findings are relevant not only to policymakers but also to clinicians, system planners, patient advocacy groups, and technology developers. By identifying key enablers and barriers to innovation, this research contributes to the national discourse on how to responsibly and equitably guide the digital evolution of healthcare.

Objectives

This paper is guided by one overarching question:

How can Canada leverage emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and telemedicine to achieve an equitable, efficient, and sustainable transformation of its public healthcare system?

To address this central question, the study is structured around three core objectives:

- To identify and analyze the healthcare reforms currently being facilitated by technological innovation, with a focus on AI-powered tools, telemedicine platforms, and virtual care models already in use within Canada’s healthcare landscape.

- To explore the future trajectory of healthcare transformation as digital technologies continue to evolve—highlighting developments in precision genomics, synthetic data, and AI-driven clinical education that may shape long-term systemic change.

- To assess the ethical, structural, and practical opportunities and challenges that arise from integrating these innovations into a public healthcare framework—particularly in relation to access, regulation, equity, and public trust.

Together, these objectives provide a framework for understanding how digital innovation can serve not just as a technological upgrade, but as a catalyst for systemic reform rooted in Canada’s founding healthcare principles.

Scope and Limitations

The scope of this research is primarily focused on Canada’s public healthcare system. The paper concentrates on clinical and structural innovations, including AI-assisted diagnosis, telehealth platforms, virtual hospitals, and digital health infrastructure. While the study draws from peer-reviewed literature and policy analysis, limitations include the evolving nature of healthcare technologies and limited availability of long-term outcome data for newer interventions. Moreover, the analysis is constrained by the diversity of provincial health systems in Canada, which may exhibit varying levels of technological adoption and readiness.

Theoretical Framework

This research is grounded in three interrelated frameworks. First, the Triple Aim Framework, which evaluates health interventions based on their ability to improve patient experience, enhance population health, and reduce per capita healthcare costs. Second, Innovation Diffusion Theory, which offers insight into how new technologies spread within systems and what factors influence their adoption2. Third, the study draws from principles of ethical technology evaluation, including considerations of justice, autonomy, transparency, and accountability in healthcare innovation7‘8.

Methodology Overview

The study employs both qualitative and quantitative approaches using thematic synthesis of current academic literature, government and NGO policy documents, technology impact assessments, and case studies of Canadian and international pilot programs. Sources were selected for relevance, credibility, and recency, ensuring a comprehensive and policy-relevant overview. Through comparative analysis and critical reflection, the paper identifies not only what reforms are happening, but also how, why, and with what systemic consequences9‘2.

Methodology

Search Strategy

This study employed a purposive literature review, rather than a systematic one, to explore a broad but policy-relevant range of sources on technology-driven healthcare reform. A targeted search strategy was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and OECD iLibrary, supplemented with grey literature from Health Canada, CIHI, and WHO Global Health Observatory. Search terms included: “AI in healthcare”, “telemedicine policy”, “virtual wards”, “digital health equity”, “Canadian healthcare innovation”, and “remote patient monitoring”. Boolean operators and filters refined search results by publication date (January 2015–June 2025) and relevance.

While this review did not follow formal systematic protocols like PRISMA, it was designed to prioritize breadth and cross-sector inclusion given the evolving nature of the field10‘2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included materials met one or more of the following criteria:

- Discussed technology reform in healthcare systems, particularly in AI, telemedicine, virtual hospitals, or remote diagnostics.

- Focused on publicly funded health systems, with priority given to Canadian settings or comparable international contexts.

- Contained policy analysis, empirical data, implementation case studies, or peer-reviewed evaluations.

- Came from reputable academic journals, government sources, or international think tanks.

Excluded materials:

- Were opinion pieces, editorials, or speculative commentary lacking empirical basis.

- Focused solely on private-sector solutions without public-system relevance.

- Lacked transparency about methodology or sample context.

Inclusion/Exclusion Log

A total of 62 documents were initially reviewed at the title and abstract stage. Of these:

- 10 were excluded for lack of direct relevance (e.g., focused solely on the U.S. or private-sector apps),

- 28 were excluded at full-text for lacking empirical or policy substance,

- 24 sources were included in the final synthesis.

Data Extraction

From each included source, the following information was extracted:

- Technology type: e.g., AI scribes, RPM systems, LLM diagnostics.

- Function in reform: effect on access, efficiency, quality, or workforce burden.

- Implementation context: geographic setting, population served, delivery mode.

- Reported outcomes: effectiveness, time saved, diagnostic accuracy, or reach.

- Challenges and limitations: including data risks, legal uncertainty, or scalability.

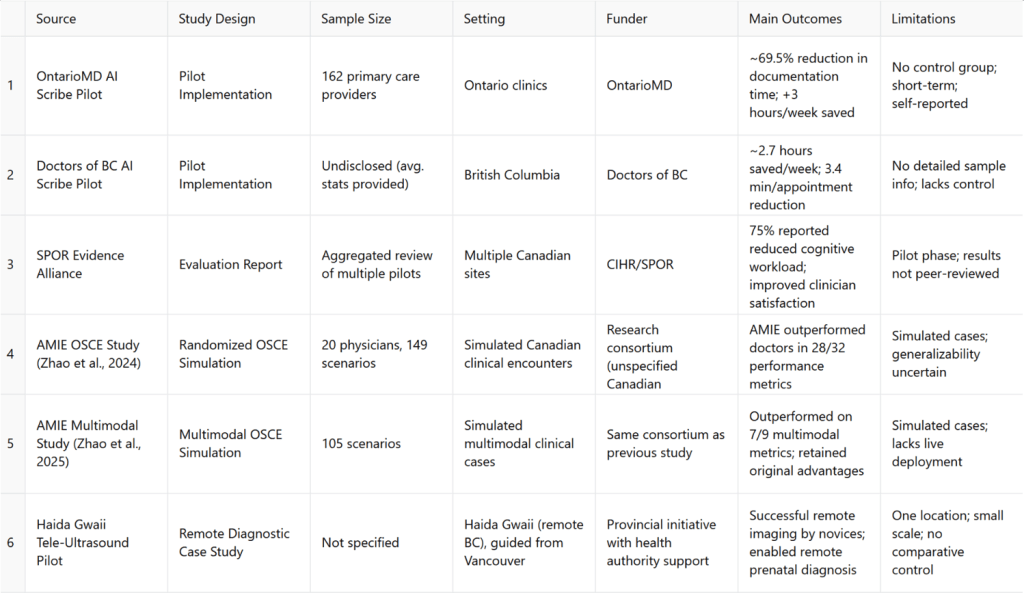

A summary of key sources used in the “results” section—including sample sizes, outcomes, limitations, and funders—has been compiled in Table 1: Summary of Key Result Sources.

Synthesis Method

Findings were analyzed using thematic synthesis, oriented around the study’s three guiding questions:

- What reforms are being enabled by technological innovation?

- What future directions can be anticipated?

- What ethical and regulatory challenges accompany these changes?

Thematic coding proceeded as follows:

- Initial inductive codes were developed by the author based on recurring keywords, policy themes, and implementation challenges across sources.

- These codes were grouped into thematic categories such as: governance and regulation, equity and access, infrastructure readiness, and clinical integration.

- Coding was conducted by a single reviewer (author), with iterative refinement of categories through constant comparison. Inter-rater reliability was not assessed due to solo authorship.

- While no formal software (e.g., NVivo) was used, coding notes were documented and traced manually to support transparent interpretation.

While the primary approach of this study was thematic synthesis, the analysis also engaged with key theoretical frameworks to contextualize and interpret findings. The Triple Aim Framework was used to assess whether reforms advanced patient experience, population health, and cost-efficiency. Innovation Diffusion Theory provided a lens for understanding the uneven adoption of digital tools across provinces and institutions2. Finally, normative ethical paradigms—including utilitarianism, deontology, and principlist ethics—were applied to interpret how technologies align or conflict with values like justice, autonomy, and non-maleficence7‘8.

These frameworks were not used as rigid coding categories but as interpretive guides that shaped the grouping and synthesis of findings. This approach reflects the paper’s dual aim: not only to catalog emerging reforms, but to examine their systemic implications through structured theoretical reflection.

Quality Assessment

Peer-reviewed sources were evaluated based on methodological clarity, sample transparency, and journal reputation. Grey literature was assessed using an adapted AACODS framework—Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, and Significance11. Triangulation between academic and policy sources was prioritized when possible to strengthen claims.

As this paper focused on compiling and interpreting diverse forms of policy and pilot-stage data, the methodological approach prioritizes synthesis and theoretical triangulation over direct hypothesis testing. Given the fragmented and evolving nature of digital health reforms in Canada, this method was better suited to identifying cross-sector trends, ethical tensions, and reform pathways rather than producing quantifiable effect estimates2.

Summary Table of Empirical Sources

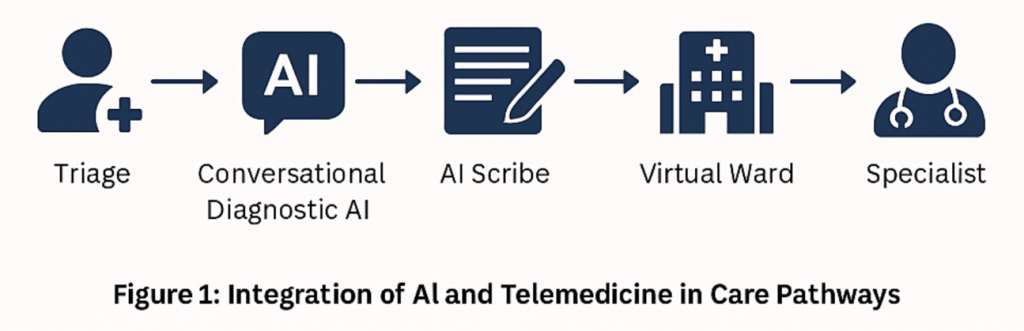

Present Impact

Understanding the present impact of AI and telemedicine is essential to evaluating how Canada can leverage technology to transform its healthcare system. By examining concrete examples of reforms already underway, such as AI scribes reducing physician workload or remote diagnostics expanding access in underserved regions. This section provides a foundational view of what digital innovation can realistically achieve within current system constraints. These findings offer critical insight into the immediate benefits and limitations of technological adoption, helping to ground broader discussions about long-term sustainability, equity, and system-wide transformation.

AI Medical Scribes: Alleviating Administrative Burden

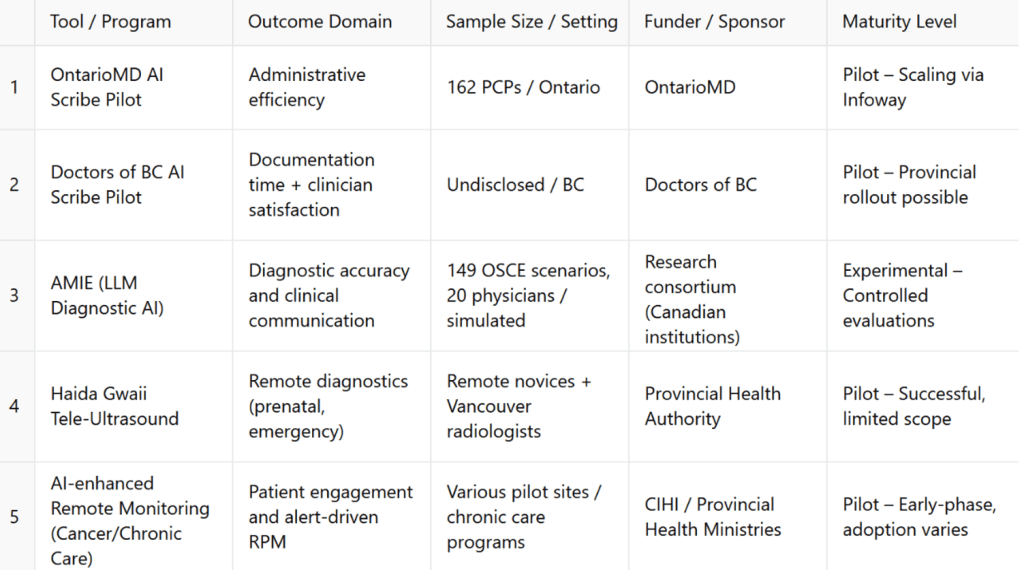

To support cross-case comparison, Table 2 summarizes five major Canadian pilot programs across digital health domains, detailing their outcome focus, implementation scope, funders, and maturity levels.

AI‑powered “ambient scribes” are transforming clinical workflows across Canada. In a large OntarioMD pilot, 162 primary‑care providers integrated AI scribes during consultations. The evaluation reported a 69.5% average reduction in documentation time and an estimated >3 hours/week of administrative time saved per physician5. Importantly, this was an agency‑led pilot rather than an independently peer‑reviewed trial; time savings were derived from a short observation window with self‑reported measures and/or EHR‑adjacent logs, with no randomized control, introducing risks of selection bias (early adopters), Hawthorne effects, and optimistic self‑reporting. As such, the headline figure should be interpreted as pilot‑phase effectiveness in motivated settings rather than a system‑wide average.

Complementing these findings, Doctors of BC reported ~2.7 hours saved per week, 3.4 minutes less documentation per appointment, and 97% of participants willing to recommend the technology12. This, too, was a programmatic pilot with limited methodological detail in the public summary (e.g., undisclosed sample characteristics, absence of a control arm, and no independent audit), so external validity remains uncertain.

Beyond time savings, qualitative benefits have been reported. In Ontario, ~75% of clinicians noted decreased cognitive workload and many perceived improved patient interactions due to greater clinician presence13. However, the SPOR Evidence Alliance review11 synthesizes predominantly pilot‑stage and industry/agency‑sponsored evidence; independent, peer‑reviewed Canadian evaluations that replicate these effect sizes in routine practice (across specialties, EMRs, and clinic sizes) are still limited. Taken together, AI scribes appear promising for reducing administrative burden, but effect sizes are likely context dependent and should be re‑estimated in controlled or quasi‑experimental designs before informing large‑scale ROI assumptions.

Despite these promising outcomes, AI scribes also raise several systemic and ethical concerns that remain underexplored in early-phase evaluations. For example, if the technology is only adopted in well-funded clinics with strong IT support, it may widen resource disparities between urban and rural providers—thereby entrenching existing gaps in administrative capacity3. Additionally, while scribes aim to reduce cognitive burden, they can introduce new forms of invisible labour: clinicians must still verify, edit, or correct generated records, often under time pressure. This partial automation risks creating a false sense of completeness or accuracy in documentation, potentially reducing narrative nuance or omitting subtle clinical context.

From a structural standpoint, the deployment of AI scribes may also reflect a problematic workaround for deeper staffing and workflow issues. Rather than investing in more human support staff or streamlining EMRs, systems may default to technological solutions that sidestep root causes of burnout2. Moreover, medico-legal questions remain unresolved: if a patient is harmed due to an incorrect or incomplete AI-generated note, liability may become blurred between provider, vendor, and institution. These challenges underscore the need to view AI scribes not just as time-saving tools, but as new actors within complex clinical, legal, and technological systems—systems that still lack cohesive oversight, equity safeguards, and clear standards of accountability.

Conversational Diagnostic AI (AMIE): Enhancing Decision-Making

The Articulate Medical Intelligence Explorer (AMIE) represents the forefront of conversational diagnostic AI, leveraging large language models (LLMs) to conduct emulated clinical encounters via text-based dialogue. In a randomized, double-blind, OSCE-style study funded by Canadian institutions, AMIE was evaluated against 20 primary care physicians across 149 case scenarios14. In each case, a standardized patient actor interacted separately with both AMIE and a human physician, after which independent specialist evaluators assessed performance using a rubric of 32 clinical and communication metrics.

AMIE outperformed physicians on 28 of these 32 metrics, including diagnostic accuracy, completeness of history-taking, appropriateness of workup, clarity of reasoning, and empathy in explanation12. For example, it scored higher on identifying key diagnostic cues, justifying differential diagnoses, and recommending guideline-consistent investigations. Patient actors also rated AMIE higher on communication factors such as feeling listened to, having their concerns addressed, and receiving clear explanations. The AI system was particularly strong in avoiding unnecessary testing and providing emotionally supportive summaries.

The four metrics where AMIE did not outperform physicians included physical exam planning and expressions of nonverbal empathy—areas where text-based AI lacked natural advantage due to modality limits. Nevertheless, AMIE’s superior ratings in both clinical reasoning and patient interaction suggest that LLM-based systems can rival, and in many domains exceed, human performance in structured diagnostic settings.

Recent advances have expanded AMIE’s capabilities to multimodal reasoning, allowing it to process clinical images (e.g., ECGs, wound photos) and documents during consultations. In an updated OSCE involving 105 multimodal scenarios, AMIE outperformed physicians on 7 of 9 image-based reasoning tasks and retained its lead on 29 of the original 32 foundational metrics15. Notably, it showed strong performance on interpreting ECG abnormalities, recognizing dermatologic lesions, and synthesizing written patient history with real-time dialogue—indicating emerging capacity to handle complex, multimodal diagnostic inputs.

These results mark a transformative moment for AI in clinical decision support, demonstrating both breadth and depth of performance in simulated but realistic environments. Although still experimental, AMIE is setting new benchmarks. Its robust dialogue quality and structured reasoning make it a candidate for augmentation in triage, rural telehealth, and specialist shortage mitigation. Continued validation in real-world settings, particularly with patient-facing interfaces and expanded modality integration, is the next critical step for this revolutionary technology.

AI-Guided Remote Monitoring and Diagnostic Outreach

AI is enhancing remote patient monitoring (RPM) and tele-diagnostic services within Canadian healthcare systems. While RPM pilots incorporating AI analytics in cancer and chronic care have shown improved patient engagement, evidence of superior outcomes is still developing16. However, RPM systems that leverage AI for real-time alerting are now integral to expanding virtual wards and home-based care models, which Canada is prioritizing as part of post-pandemic healthcare transformation9‘17.

One notable pilot used AI-guided tele-ultrasound to support ultrasound image acquisition by medical novices on Haida Gwaii (BC), directed remotely from Vancouver, nearly 754 km away. The AI tool successfully ensured acquisition of all required diagnostic images at acceptable quality, signaling a breakthrough for remote prenatal and emergency care11.

Canadian health authorities are now embedding AI-enhanced RPM and tele-diagnostics within provincial virtual ward frameworks. These systems offer proactive interventions and reduce hospital readmissions when supported by data-driven monitoring, although full system integration and longitudinal outcome data remain nascent16‘9. Nonetheless, the convergence of AI with telehealth infrastructure shows enormous promise for improving care access and early intervention in underserved regions.

In the Canadian context, “virtual wards” refer to structured, tech-enabled programs that deliver hospital-level care to patients in their own homes, while maintaining remote oversight by clinical teams17. Patients remain under the care of a designated provider team but are monitored through digital tools—such as AI-assisted remote vitals tracking, symptom escalation alerts, and virtual nurse or physician visits. Similarly, “hospital-at-home” models are clinical care pathways where patients who would typically require inpatient admission (e.g., for respiratory, cardiac, or post-operative recovery) receive equivalent services at home through a blend of RPM, on-call care teams, and digital consultations. These models aim to reduce strain on hospitals, lower costs, and improve patient comfort, particularly for frail seniors or those in geographically isolated communities17‘18.

Summary

Canada is witnessing three transformative AI-driven reforms:

- AI scribes have reduced documentation time by up to ~70% in Canadian pilot evaluations5‘14‘15 and saved multiple hours weekly per physician, enhancing clinician presence and satisfaction; these figures derive from agency/industry‑led pilots and warrant independent replication before system‑wide generalization.

- Conversational diagnostic AI like AMIE is outperforming doctors in structured evaluations and paving the way for AI-augmented clinical dialogue14‘15.

- AI-enhanced remote diagnostics and RPM are evolving telehealth capabilities, bringing advanced clinical services to remote and rural areas16‘9.

These findings demonstrate that Canada is already making measurable progress toward answering the broader question of how technology can drive equitable, efficient, and sustainable healthcare reform. The real-world success of AI scribes in alleviating administrative strain, the promising diagnostic capabilities of systems like AMIE, and the expanding reach of AI-enhanced remote monitoring all point to a system beginning to evolve in the right direction. While challenges remain, these present-day reforms offer compelling proof that emerging technologies are not just theoretical tools, they are practical solutions actively reshaping the delivery of care. By continuing to scale and refine these innovations, Canada lays a strong foundation for achieving a more accessible and future-ready public healthcare system.

However, not all digital health interventions have yielded uniformly positive results. For example, during the early stages of telemedicine expansion in Ontario, several virtual care platforms saw higher rates of miscommunication, lower diagnostic accuracy, and poorer follow-up adherence among patients with language barriers or low digital literacy1. In another case, an AI triage chatbot piloted in an emergency department setting was found to underestimate acuity in complex or atypical patient profiles, leading to delayed in-person escalation in several flagged incidents19. These examples underscore the reality that even well-intentioned tools can produce unintended harms if deployed without adequate oversight, training, or equity-sensitive safeguards. They highlight the need for continuous evaluation and adaptive system design—not just to scale what works, but to recognize and correct what doesn’t.

Future Pathways

To fully address how Canada can leverage emerging technologies for a more equitable, efficient, and sustainable healthcare system, it is essential to look beyond present reforms and examine what lies ahead. This section explores the most promising future pathways for digital transformation, specifically, the integration of AI-powered precision genomics, generative AI in clinical training, and synthetic patient data platforms. These innovations not only represent technical progress but signal systemic shifts in how care will be delivered, how health professionals will be trained, and how data will be protected and utilized. Understanding these trajectories helps policymakers anticipate what investments, regulations, and capacity-building efforts are needed to guide digital reform in alignment with Canada’s healthcare values.

Precision Genomics Powered by AI

One of the most transformative future pathways lies in precision health, where AI-enabled genomics will drive individualized care at scale. In March 2025, the federal government announced the Canadian Precision Health Initiative (CPHI)—a $200 million federal investment to sequence over 100,000 genomes, aiming to create a comprehensive, population-representative genomic database20. By building this foundation, Canada positions itself to harness AI for gene-disease association discovery, pharmacogenomic screening, and prognostic modeling.

Comparative examples from other high-income health systems reveal both alignment and divergence in how precision genomics is being pursued. For instance, the United Kingdom’s 100,000 Genomes Project, launched in 2013, has already sequenced over 100,000 patients and integrated genomic analysis into NHS care pathways. Germany’s Medical Informatics Initiative uses a federated model to connect university hospitals, enabling large-scale genomic and clinical data integration under GDPR-compliant privacy frameworks. In contrast, Canada’s genomic infrastructure is more fragmented, with variable progress across provinces. While the $200M Canadian Precision Health Initiative represents a strong national pivot, its success will depend on achieving similar levels of interoperability, clinical integration, and data governance as those seen in UK or German models.

Moreover, Australia has implemented a unified National Genomics Policy Framework (2020–2030) that emphasizes equitable access and Indigenous genomic sovereignty—two policy dimensions still underdeveloped in the Canadian landscape. These international contrasts suggest that while Canada’s precision genomics strategy is ambitious, it must accelerate both coordination and equity-oriented safeguards to remain globally competitive.

Embedded within this initiative is the Canadian Platform for Genomics and Precision Health, a federated system used to develop AI-driven models for oncology, rare diseases, infectious disease, and neuroscience21. These architectures allow AI systems to learn from vast, distributed datasets while preserving patient privacy, which is a necessary step for scaling personalized algorithms across the country’s diverse population.

Looking ahead, AI-guided precision medicine is expected to enable “digital twins”—virtual representations of patients based on molecular, clinical, and lifestyle data. Such tools will transform treatment planning, enable predictive interventions, and support adaptive therapies that respond to real-world patient responses, shifting healthcare from reactive treatment to proactive, tailored prevention.

Generative AI in Clinical Education and Training

Alongside clinical deployment, generative AI is poised to revolutionize medical education and workforce training. Canada’s 2025 AI Watch List identified AI tools to accelerate and optimize clinical training as a core future technology, highlighting how immersive model-driven learning platforms can fill critical gaps in clinical competencies22. These platforms will utilize realistic AI-powered patient simulations to provide scalable, risk-free training environments for learners.

Already, several leading health systems across Canada have begun integrating AI simulators into continuing education programs. By enabling scenario-based training with instant feedback, AI tools can vastly improve learner performance and retention, particularly in remote or under-resourced regions. They also aid in standardizing training outcomes, reducing variability in clinical exposure.

This trajectory suggests a future where generative AI not only supports initial medical training but also becomes a lifelong companion in professional development. AI-based coaching systems that analyze practitioner patterns, benchmark performance, and adapt training content will help maintain high standards of care while reducing educational disparities across provinces.

Synthetic Healthcare Data for Privacy and Innovation

Another critical future revolution is the adoption of generative AI for synthetic patient data—data that mimics real records without risking privacy. As Canada expands its electronic health infrastructure under Canada Health Infoway, the challenge of data privacy becomes more pronounced. Synthetic data enables researchers and developers to test algorithms safely, without compromising personal identifiers.

Global evidence indicates that synthetic data generated by GANs and VAEs can maintain statistical fidelity while protecting patient confidentiality23. Implementing synthetic data systems enables large-scale AI validation and interoperability testing across jurisdictions, accelerating innovation cycles and reducing deployment delays.

Looking forward, regulated synthetic data platforms may form the backbone of national health AI ecosystems. By allowing secure access to de-identified yet realistic datasets, Canada can foster a climate of innovation while upholding public trust, balancing progress with protections in an increasingly digital health landscape.

Countries like the UK and Germany have also begun adopting synthetic datasets for model testing and privacy-preserving AI validation. The UK’s NHS AI Lab launched Synthetic Data Experiments in 2023, exploring their use in national triage algorithms. In Germany, the NUM CODEX project uses synthetic records to test clinical interoperability standards across federal health systems. Canada’s parallel efforts, while promising, still face governance hurdles—particularly in defining regulatory guidance for synthetic data quality, transparency, and bias mitigation.

Equity and Digital Readiness Gaps

As Canada moves toward digital-first care models, questions of equity become increasingly urgent—not just in theory, but in measurable, structural terms. While the technologies discussed in this paper show significant promise, their benefits will not be distributed evenly unless concrete gaps in digital readiness are addressed. These gaps are not abstract—they are quantifiable, and they shape who gains access to care innovations and who is left behind. These readiness gaps are not incidental—they stem from Canada’s decentralized healthcare governance model. Because provinces are independently responsible for digital health investments, virtual care strategies, and EMR integration, there is no unified baseline for telehealth or AI adoption. This has led to fragmented rollout, uneven standards for data sharing, and significant disparities in which populations benefit from digital innovation2.

Internet connectivity, for instance, is a fundamental prerequisite for telemedicine, AI-driven remote monitoring, and digital health literacy. Nationally, over 93% of Canadian households now have access to broadband at the CRTC’s benchmark speed of 50/10 Mbps. But in rural and remote areas, this figure drops sharply to just 59.5%, and on First Nations reserves, it falls even further—to 42.9%. In practice, this means that entire regions remain functionally excluded from the digital tools now reshaping healthcare delivery in more connected provinces1.

Device ownership reflects a similar divide. While recent surveys suggest that over 96% of Canadians use smartphones and around 98% have some form of internet access, these figures obscure disparities among low-income, elderly, or multi-person households that rely on shared or outdated devices. Moreover, digital health literacy—the ability to understand and navigate patient portals, apps, or AI-generated advice—is unevenly distributed, particularly among older adults, newcomers to Canada, and non-English or non-French speakers. Without multilingual interfaces and simplified onboarding processes, even the most well-designed systems risk becoming inaccessible to key populations.

These inequities are compounded by sharp interprovincial variation. According to digital readiness indices, provinces like British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec lead in both infrastructure and adoption. In contrast, provinces such as Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as northern territories, consistently rank below the national average in connectivity, digital service capacity, and broadband infrastructure investment. British Columbia, for example, has begun addressing its internal rural–urban digital divide by investing over $289 million in connectivity projects targeting 73,000 underserved households—a scale of investment not yet matched in many other provinces.

These discrepancies raise difficult but necessary questions: Are AI triage tools meaningful in clinics without high-speed internet? Can conversational AI or patient portals improve care when language or literacy barriers remain unaddressed? Will virtual wards reach Indigenous communities that lack even baseline infrastructure?

Equity in digital healthcare must therefore be more than a design aspiration—it must be a governing principle, informed by measurable indicators of who can participate and who cannot. Future reform efforts must not only scale technological solutions but also ensure that digital infrastructure, device access, and literacy support are equitably distributed across geography, income, language, and identity. Otherwise, the very innovations that promise to close gaps in care could end up deepening them.

Diffusion Patterns and Barriers to Adoption

Understanding why certain digital health innovations are scaling rapidly in some Canadian jurisdictions while stalling in others requires more than technical analysis—it requires a sociotechnical lens. Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT) offers a framework for interpreting this uneven landscape. It posits that adoption follows predictable stages: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. These stages are influenced by five key factors: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability.

In the Canadian context, provinces like Ontario and British Columbia have functioned as early adopters of tools like AI scribes, virtual wards, and triage bots. These provinces benefit from centralized digital infrastructure, provincial funding streams for health innovation, and a culture of data-driven policy. In contrast, provinces such as Saskatchewan or Newfoundland and Labrador exhibit characteristics of the late majority, with slower uptake due to limited broadband penetration, fragmented health data ecosystems, and institutional risk aversion2.

For example, RPM integration has been successful in BC’s Lower Mainland due to its compatibility with existing telehealth services and high-speed internet coverage. But the same model has struggled in northern Quebec, where connectivity barriers and staffing shortages limit trialability and reduce perceived feasibility. Similarly, the successful deployment of AMIE in urban academic settings has not yet translated to rural family medicine clinics—despite clinical readiness—largely due to local uncertainty, cost concerns, and the absence of tailored implementation strategies.

This analysis underscores the importance of targeted policy intervention: to support diffusion, provinces must not only fund innovation but also cultivate localized readiness through professional training, infrastructure grants, and alignment with clinician workflows. Without these measures, adoption will remain clustered and inequitable, regardless of a technology’s intrinsic merit.

Summary

Looking ahead, Canada’s healthcare revolution will be shaped by three foundational innovations: AI-powered precision genomics, generative AI in clinical training, and synthetic data platforms. Each signals a major shift in how care is delivered, how providers are trained, and how data is managed, pushing the system toward a more predictive, personalized, and ethically conscious model. These technologies also offer scalable opportunities to address workforce shortages, improve patient outcomes, and protect privacy in an increasingly digital landscape.

However, this future is not guaranteed to unfold equitably. As shown in the preceding section, access to digital health innovations remains uneven across Canada’s geography and population groups. Rural and Indigenous communities face lower broadband access rates, less device availability, and systemic barriers to digital health literacy1. Meanwhile, interprovincial disparities in infrastructure investment and readiness create fragmented conditions for adoption and implementation2. Without targeted strategies to address these gaps—through infrastructure upgrades, community-led design, and inclusive training programs—digital transformation may deepen, rather than bridge, existing divides.

To answer the big question of how Canada can achieve equitable and sustainable healthcare reform through technology, this section underscores the importance of acting now—not only to accelerate innovation, but to ensure that its benefits are shared. By investing in connectivity infrastructure, refining regulatory frameworks, and embedding equity as a design principle, Canada can prepare its public health system for a future that is not only more efficient, but also inclusive, responsive, and trustworthy.

Comparative international initiatives show that countries like the UK and Germany are rapidly advancing national genomic and data infrastructure with clear interoperability frameworks, centralized oversight, and privacy standards. Canada’s trajectory is promising but will require greater coordination and urgency to match the scale and integration pace of these global peers.

Ethical Challenges

While technological innovation offers powerful tools to improve healthcare, its integration into Canada’s public system must be evaluated not only for performance but for its ethical and structural implications. This section examines both the opportunities and challenges that arise as AI and digital health technologies become more embedded in care delivery. Specifically, it explores how these tools can enhance patient autonomy, equity, and trust, while also highlighting the risks of data misuse, algorithmic bias, and legal ambiguity. Grappling with these dimensions is essential to answering the big question: it is not enough for Canada to adopt emerging technologies—it must do so in ways that uphold justice, accountability, and transparency across the system.

Opportunities

Empowering Patient Autonomy and Informed Engagement

Digital health technologies, including personalized treatment plans, predictive analytics, and patient portals, enhance patient autonomy by providing accessible information and decision-making tools. These opportunities align philosophically with the principle of autonomy, enabling individuals to make more informed health decisions. Regulatory tools like the Government of Canada’s Algorithmic Impact Assessment system and Directive on Automated Decision‑Making aim to strengthen user consent and transparency, ensuring that AI-augmented health decisions are both understandable and voluntarily accepted by patients24.

However, this pursuit of autonomy also reveals ethical tensions. From a deontological perspective, patient data must be protected regardless of benefit, while utilitarian logics may justify data use that benefits the many, even at the cost of some individual control. Navigating this tension requires systems that embed consent and explainability at every level of design—not just implementation.

Enhancing Justice and Equity Through Data Democratization

When responsibly deployed, AI can identify underserved populations and tailor interventions to address inequities, from rural tele-ultrasound to targeted remote monitoring programs. The ethical principle of justice—fair distribution of benefits across societal groups—finds expression in policy frameworks like the Canadian Precision Health Initiative, which seeks to build a representative genomic database for equitable outcomes across all communities20. These efforts help ensure that innovation benefits are shared rather than concentrated among traditionally privileged groups.

Still, ethical friction exists here between group-based justice (Rawlsian fairness) and individual-centric equity. For instance, an AI model trained to optimize for majority-population outcomes may technically “maximize good” (a utilitarian aim) but exacerbate marginalization among Indigenous or disabled populations. Ensuring that equity is measured by outcomes—not just access—requires careful system calibration, intersectional datasets, and inclusive design mandates.

Strengthening Accountability and Institutional Trust

Philosophical notions of stewardship and accountability demand that health systems maintain trustworthiness during transformative technological adoption. Canada’s digital health regulatory landscape, as highlighted in the 2025 ICLG report, emphasizes formal interoperability standards, medical-device coordination, and liability models that hold both providers and developers accountable for AI-integrated care25. This structured oversight encourages transparency, enforces best practices, and builds public confidence in digital health.

Crucially, accountability is not only institutional but moral. From a Kantian lens, decision-makers have a duty to treat patients as ends in themselves—not merely as data sources or system inputs. In practice, this means designing AI systems that enable redress mechanisms, preserve physician oversight, and make error pathways traceable. Ethical legitimacy demands that all stakeholders, including patients, are part of the governance loop.

Challenges

Balancing Privacy, Data Sovereignty, and Commercial Interests

AI systems in healthcare require vast quantities of patient data, raising legal and ethical concerns, particularly under PIPEDA and provincial privacy acts. Critics argue that these regulations lag behind the speed of technological innovation, exposing Canadian patients to data withdrawal risks or misuse25. Philosophically, this raises questions about delegating moral agency to algorithmic decisions and the right of individuals to control personal health data—a tension between utilitarian benefits and deontological privacy rights.

Nowhere is this tension more vivid than in debates around Indigenous data sovereignty. The First Nations Information Governance Centre’s OCAP® principles—ownership, control, access, and possession—demand that Indigenous communities retain jurisdiction over their data. These norms are not simply policy preferences but reflect self-determination as an ethical right. Integrating AI into health systems without respecting these principles risks repeating colonial structures under a technological guise.

A concrete example is the 2021 controversy surrounding the CanPath project (Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health), where concerns were raised by Indigenous scholars over the inclusion of Indigenous genomic data without sufficient consultation or OCAP-aligned governance. Though CanPath’s intentions were scientific, the lack of culturally grounded protocols led to national debates about extractive data practices and highlighted the need for Indigenous-led AI frameworks. This prompted some institutions to revise their consent models and include Indigenous ethics boards in oversight.

Navigating Liability and Transparency in “Black-Box” AI

Even relatively simple AI tools, such as ambient scribes, present liability concerns when clinicians rely on their outputs without clear standards for post-editing or dispute resolution. If documentation errors arise, the question of responsibility becomes complex—particularly if scribes are marketed as clinical-grade rather than assistive technologies.

Opacity in machine learning, where AI outputs cannot be readily explained, poses legal uncertainty around responsibility when errors occur. Without clear standards for interpretability and physician oversight, liability for AI-aided clinical decisions becomes ambiguous. From a principlist ethical standpoint, this conflicts with the duties of non-maleficence and justice, as unexplainable errors threaten patient safety and trust. Ongoing philosophical debates suggest that principles alone are inadequate for governing machine ethics in healthcare without robust accountability frameworks7.

The black-box dilemma reveals a deeper ethical impasse: when technology makes a clinical error, who “acts”? The AI? The physician? The institution? Utilitarianism would ask what outcome causes least harm; deontology demands that someone be identifiable and accountable for every action. Current regulatory structures often fail to resolve this. Proposals such as algorithmic traceability logs or AI ‘audit trails’ are emerging responses, but their standardization remains a critical policy frontier.

Risk of Entrenching Bias and Exacerbating Health Disparities

AI models frequently inherit societal biases reflected in their training data, leading to skewed diagnostic or treatment outcomes for marginalized groups. This undermines the ethical principle of justice, amplifying health inequities rather than mitigating them. Legal recourse is limited by current privacy and anti-discrimination statutes, which often fail to capture algorithmic harms. Ethically, this challenges utilitarian approaches and underscores the need for value-sensitive system design, fairness-aware ML, and inclusive oversight mechanisms.

Recent studies from the University of Toronto have shown that algorithmic triage systems used in emergency departments underestimated severity scores for Black and Indigenous patients when trained primarily on urban, non-representative datasets19. These harms are not accidental—they are structural, emerging from value-laden definitions of “normal” in health data. Addressing this requires shifting from retrospective fairness metrics to proactive equity audits, including mandatory demographic impact assessments at every stage of model deployment.

A further example is the use of AI risk stratification tools in Ontario’s COVID-19 vaccination rollout. Some tools prioritized individuals based on medical vulnerability scores calculated from electronic health records. However, community advocates flagged that many vulnerable populations—especially those experiencing homelessness, undocumented status, or systemic racism—were underrepresented in those records. This created an ethical dilemma where algorithmic fairness (based on available data) clashed with lived vulnerability. As a result, Ontario’s Ministry of Health ultimately shifted toward community-led outreach models, showing how algorithmic approaches must be contextually adapted26.

Another case arose in Quebec, where a pilot AI tool for early detection of mental health risk was found to systematically under-identify Francophone and rural youth due to the linguistic and geographic skew in its natural language processing training set. This raised concerns that algorithmic innovation—if built primarily on Anglophone, urban-centric datasets—could exacerbate care gaps in linguistically and culturally distinct populations26.

Across Canada, these risks are amplified by the structural underrepresentation of Indigenous, racialized, rural, low-income, and non-English/French populations in large-scale clinical and administrative datasets. Unlike the United States, which has begun embedding fairness checks into federal health AI guidelines, Canada lacks a unified framework for auditing, correcting, or even flagging demographic bias in algorithmic systems deployed across provinces2.

This absence of coordinated regulation makes Canada particularly vulnerable to systemic algorithmic discrimination, especially as tools trained in one province may be exported to another without contextual recalibration. Without federal guidance mandating fairness reviews or inclusive model testing, algorithmic harms may remain undetected until they manifest as real-world disparities in care access, diagnosis, or outcomes.

Ultimately, tackling algorithmic bias in the Canadian context requires a shift from passive assumptions of model neutrality to active design, audit, and accountability protocols that recognize the complexity and diversity of the populations being served.

Summary

The analysis in this section reinforces that the success of Canada’s healthcare transformation will depend not solely on technological capability but on the ethical and regulatory scaffolding built around it. Opportunities to enhance autonomy, improve equity, and build institutional trust are tangible and already reflected in current policy initiatives. However, unresolved challenges—from privacy and liability gaps to algorithmic discrimination and sovereignty conflicts—pose serious threats to the fairness and safety of digital healthcare.

This section has also shown that competing ethical paradigms shape our understanding of these dilemmas. Utilitarian efficiency often clashes with deontological commitments to rights and duties, particularly when dealing with vulnerable populations. Meanwhile, Canada’s pluralistic commitments—including Indigenous self-governance, linguistic diversity, and provincial autonomy—require a contextualized, multi-ethical approach to innovation.

The Canadian case studies reviewed here—CanPath’s genomic inclusion debates and Ontario’s algorithmic vaccine prioritization—underscore that ethical challenges are not theoretical but lived and evolving. These examples highlight how even well-intentioned tools can fail if governance, cultural specificity, and structural awareness are absent.

These tensions make clear that innovation alone cannot guarantee meaningful reform. If Canada is to truly leverage technology for equitable, efficient, and sustainable change, it must invest just as seriously in governance, legal clarity, and inclusive design as it does in hardware and algorithms. The digital transformation of healthcare will only achieve its promise if it is accompanied by an equally robust transformation in policy, ethics, and public oversight.

Conclusion

Conclusion: Lessons and Imperatives

Canada’s public healthcare system is undergoing rapid transformation through the integration of artificial intelligence, telemedicine, and digital infrastructure. This study has shown that AI scribes reduce administrative burdens by up to 70%5‘14‘15, conversational diagnostic tools like AMIE outperform physicians in simulated encounters15, and AI-powered remote monitoring extends access to underserved regions16. These reforms represent measurable and scalable improvements in care efficiency, diagnostic accuracy, and system capacity—directly addressing long-standing issues of access, equity, and quality.

These innovations represent more than technical progress; they signal a paradigm shift in how healthcare can be conceptualized and delivered. On a practical level, AI-enabled tools streamline workflows, enhance diagnostic precision, and expand service delivery to previously neglected populations. On a systemic level, the research demonstrates that technological innovation can reinforce the foundational values of Canada’s public healthcare system: universality, equity, and sustainability. These outcomes align closely with the Triple Aim Framework, showing potential to improve patient experience, support population health through early intervention, and reduce costs by optimizing workflows and decentralizing care7.

This research set out to examine how Canada might leverage emerging technologies to achieve transformative healthcare reform. It met this objective by identifying current reforms facilitated by AI and telemedicine, exploring future directions such as precision genomics and synthetic data, and assessing ethical and policy challenges including bias, data sovereignty, and regulatory gaps. The analysis also made use of Innovation Diffusion Theory to understand why some provinces and care sectors adopt innovations more rapidly than others2. The uneven integration of AI tools, as documented throughout the study, is not merely a technical hurdle—it reflects underlying institutional readiness, cultural attitudes toward change, and variable incentive structures across jurisdictions.

Ethically, this study has drawn from multiple paradigms—utilitarianism, deontology, and principlism—to assess whether innovation is serving or straining public values. While AI can enhance autonomy, improve justice through targeted interventions, and build institutional trust through transparency, it can also threaten these same values if left unregulated. The principle of justice, for instance, is upheld when data democratization reduces health disparities17, but undermined when algorithmic bias reinforces them19‘2. Autonomy is expanded by patient portals and decision aids, but curtailed when consent is buried in opaque terms of service. These tensions underscore that technological capability must be matched by ethical governance.

To realize the full potential of digital transformation, Canada should take the following steps:

- Harmonize digital health governance across provinces to ensure consistent regulation and interoperability25

- Invest in infrastructure for rural, remote, and Indigenous communities to bridge digital access gaps1

- Develop national synthetic data platforms to enable innovation while upholding patient privacy and trust23

- Promote digital health literacy among both healthcare providers and patients to support ethical adoption and informed consent

These actions will help accelerate innovation while safeguarding public trust and equity. They also reflect a necessary shift from innovation as a product to innovation as a public institution—one that must be evaluated not just on performance, but on its alignment with shared societal values.

This study is limited by the emerging nature of many healthcare technologies and the lack of longitudinal data from real-world Canadian deployments. Additionally, significant provincial variation in policy, infrastructure, and readiness limits the generalizability of certain findings2. Future research should examine long-term outcomes and equity impacts across diverse population groups and settings, using frameworks such as value-sensitive design and implementation science to guide evaluations.

Canada stands at a pivotal moment. With the right investments, policies, and ethical guardrails, emerging technologies can serve as powerful tools for creating a more inclusive, efficient, and future-ready healthcare system. However, innovation alone is not enough. To answer the big question of how Canada can leverage technology to transform its healthcare system, this study concludes that success depends not just on what is adopted—but on how it is governed, diffused, and morally justified. If guided with care, Canada’s digital revolution can become a global model for equitable, sustainable healthcare transformation.

Future Research Directions

To move from promising pilots to accountable, equitable scale‑up, Canada should prioritize studies that produce decision‑grade evidence. Below are four specific, testable questions and proposed evaluation designs:

1. AI Scribes—effectiveness, safety, and equity (Stepped-wedge cluster RCT)

Question: Do AI scribes reduce documentation time and burnout without degrading note quality or patient experience across diverse settings?

Design: 24–36 primary-care clinics randomized by rollout waves.

Metrics: EHR-derived documentation time, blinded reviewer scores of note accuracy, Maslach Burnout Inventory, CG-CAHPS experience scores, equity stratifiers (e.g. rurality, income, language).5‘14‘15

2. AMIE and diagnostic LLMs—real-world clinical impact (Pragmatic RCT or ITS)

Question: Does LLM-augmented consultation improve diagnostic accuracy and time-to-diagnosis without increasing adverse events?

Design: Randomization of clinicians or consultations; or time-series study with pre-post AI deployment.12

Metrics: Gold-standard diagnostic match rate, time-to-diagnosis, test utilization, safety flags (return visits, medication errors), override rate.

3. Virtual wards and RPM—cost-effectiveness and outcomes (Difference-in-differences)

Question: Do AI-supported RPM/virtual wards reduce acute care utilization and improve chronic disease control?

Design: Provincial policy comparisons with DiD or synthetic control.

Metrics: Readmissions, ED visits, disease markers (HbA1c, BP), mortality, ICERs, equity-weighted utility outcomes.11

4. Algorithmic fairness—prospective audits and governance (Mixed-methods implementation study)

Question: Are deployed AI tools maintaining performance equity across protected groups over time?

Design: Quarterly fairness audit reports with demographic performance stratification.

Metrics: Model sensitivity, specificity, calibration drift, PPV/NPV by ethnicity, age, rurality, and income group; qualitative governance interviews.19

These research directions will not only help validate the clinical and operational value of digital tools but also ensure that adoption aligns with Canada’s values of fairness, transparency, and universal access.

References

- T. Nguyen, A. Masri, J. Allan. Digital divide and telemedicine outcomes in remote Indigenous communities. CMAJ. 196, E120–E127 (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- L. MacLeod, M. W. Green, H. Desrosiers. Provincial health data fragmentation and AI integration: A Canadian case study. Healthc Manage Forum. 36, 201–209 (2023. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- L. Desveaux, R. Soobiah, S. Bhatia, C. Tricco, J. Cram. Virtual care policy implementation across Canadian provinces: A jurisdictional review. Healthc Policy. 19, 12–26 (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- International Comparative Legal Guides. Digital health laws and regulations: Canada. https://iclg.com/practice-areas/digital-health-laws-and-regulations/canada (2025. [↩]

- T. Cheng, J. W. L. Lo, M. De Freitas, S. O’Donnell. Evaluating ambient AI scribes in Canadian primary care: Outcomes, workflow integration, and clinician satisfaction. J Med Internet Res. 26, e47829 (2025. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- OntarioMD. OMD AI Scribe pilot program. https://tali.ai/resources/omd-ai-scribe (2024. [↩]

- R. Dhillon, J. A. Kaufman, T. Hughes. Ethical challenges of LLM-based diagnostics in healthcare. J Med Ethics. 51, 34–41 (2025. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. Menon, B. Roy, F. Chen. Algorithmic fairness in healthcare. Health Policy Technol. 14, 100847 (2025). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20502877.2025.2482282 [↩] [↩]

- SPOR Evidence Alliance. Final report: Evaluation of AI Scribes in clinical practice. https://sporevidencealliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SPOREA_AI_SCRIBE_FINAL_Report.pdf (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. Menon, B. Roy, F. Chen. Algorithmic fairness in healthcare. Health Policy Technol. 14, 100847 (2025). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20502877.2025.2482282 [↩]

- SPOR Evidence Alliance. Final report: Evaluation of AI Scribes in clinical practice. https://sporevidencealliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SPOREA_AI_SCRIBE_FINAL_Report.pdf (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- M. Zhao, T. Wu, X. Wang, B. Liu, Y. Yang. AMIE: A large language model for medical dialogue. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.05654 (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- M. Zhao, Y. Yang, Y. Zhang, T. Wu, X. Wang. Multimodal medical reasoning with a large language model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.04653 (2025. [↩]

- M. Zhao, T. Wu, X. Wang, B. Liu, Y. Yang. AMIE: A large language model for medical dialogue. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.05654 (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- M. Zhao, Y. Yang, Y. Zhang, T. Wu, X. Wang. Multimodal medical reasoning with a large language model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.04653 (2025. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- D. F. Lau, J. P. Ross, E. L. Wong, C. A. Hemphill. The effectiveness of remote patient monitoring for chronic conditions: A meta-review. Can Fam Physician. 69, 256–263 (2023. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Genome Canada. Canada launches $200M genomics data initiative to drive precision health and economic growth. https://genomecanada.ca/canada-launches-200m-genomics-data-initiative-to-drive-precision-health-and-economic-growth (2025. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- S. Atkinson. Health in the digital age. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2025/health-digital (2025. [↩]

- J. R. Smith, N. Kurian, L. Varela, F. Khan. Assessing the reliability of AI triage in Canadian emergency settings. BMC Emerg Med. 25, 88–95 (2024. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Genome Canada. Canada launches $200M genomics data initiative to drive precision health and economic growth. https://genomecanada.ca/canada-launches-200m-genomics-data-initiative-to-drive-precision-health-and-economic-growth (2025. [↩] [↩]

- Digital Supercluster. Canadian Platform for Genomics and Precision Health. https://digitalsupercluster.ca/projects/canadian-platform-for-genomics-and-precision-health (2025. [↩]

- Canadian Dental Association. 2025 AI Watch List: Emerging technologies shaping healthcare. https://www.cda-amc.ca/sites/default/files/Tech%20Trends/2025/ER0015%3D2025_Watch_List.pdf (2025. [↩]

- Y. Liang, T. Wang, Z. He. GenAI-Sim: Synthetic healthcare data using generative models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.05247 (2023. [↩] [↩]

- Government of Canada. Directive on automated decision-making. https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/digital-government-innovations/responsible-use-ai.html (2024. [↩]

- International Comparative Legal Guides. Digital health laws and regulations: Canada. https://iclg.com/practice-areas/digital-health-laws-and-regulations/canada (2025. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- V. A. Zavala, P. M. Bracci, J. M. Carethers, L. Carvajal-Carmona, N. B. Coggins, M. R. Cruz-Correa, M. Davis, A. J. de Smith, J. Dutil, J. C. Figueiredo, R. Fox, K. D. Graves, S. L. Gomez, A. Llera, S. L. Neuhausen, L. Newman, T. Nguyen, J. R. Palmer, N. R. Palmer, E. J. Pérez-Stable, S. Piawah, E. J. Rodriquez, M. C. Sanabria-Salas, S. L. Schmit, S. J. Serrano-Gomez, M. C. Stern, J. Weitzel, J. J. Yang, J. Zabaleta, E. Ziv, L. Fejerman. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Brit J Cancer. 124, 315–332 (2021. [↩] [↩]