Abstract

Climate change–induced environmental stresses such as high temperature, drought, and salt accumulation threaten global crop productivity. To investigate plant adaptation mechanisms, we conducted a dose-dependent salt stress assay in Arabidopsis thaliana (0, 50, 100 mM NaCl). Salt-treated seedlings displayed growth inhibition and tissue bleaching, confirming effective stress induction. Transcriptomic analysis revealed upregulation of known salt-responsive genes (SOS1, NHX1) and identified SAGT1, a previously uncharacterized gene, as the most strongly induced. SAGT1 was predicted to encode a glycosyltransferase. CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of SAGT1 impaired salt tolerance despite normal expression of SOS1 and NHX1 transcripts, suggesting a post-transcriptional defect. Pull-down and Western blot assays confirmed that SAGT1 is required for SOS1 glycosylation, which is essential for its stability and function. This study identifies SAGT1 as a novel regulator of salt stress adaptation via glycosylation-mediated post-translational control. By highlighting protein quality control as a key component of stress resilience, our findings expand the current paradigm of plant abiotic stress responses. SAGT1 and its downstream pathway offer a promising target for engineering stress-resilient crops in the face of accelerating climate change.

Keywords: Salt tolerance, SAGT1, glycosylation, climate change, Tunicamycin

Introduction

Since the mid-20th century, global climate change—largely driven by the accumulation of greenhouse gases—has resulted in a steady increase in average global temperatures, alongside a rise in extreme weather events such as heatwaves, droughts, and intense rainfall1. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report, the frequency and duration of extreme heat events are expected to continue increasing, posing significant threats to both natural ecosystems and agricultural productivity2. In particular, high temperatures during the reproductive phase of plants have been shown to drastically reduce crop yields3,and repeated cycles of heat and humidity can lead to extensive damage in a wide range of plant species4.

These environmental challenges have become a major concern for food security, especially in tropical and temperate regions where key staple crops such as wheat, rice, and maize are grown. Elevated temperatures can exacerbate salt accumulation in the soil through increased evapotranspiration, further compounding abiotic stress on plants5. Salt stress is one of the most detrimental abiotic stresses affecting plant growth and productivity, particularly in regions where salinity in soil is prevalent6.

To better understand how plants respond to salt stress under climate change–related conditions, we conducted a dose-dependent analysis of salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Seedlings were grown on media supplemented with increasing concentrations of NaCl (0, 50, and 100 mM) to simulate mild to severe salt stress. Phenotypic observations revealed progressive growth inhibition, chlorosis, and bleaching with increasing salinity. Based on these morphological responses, we performed RNA sequencing to identify salt-responsive genes and dissect the underlying molecular mechanisms of salt adaptation.

Our transcriptomic analysis highlighted several canonical salt-tolerance genes such as SOS1 and NHX1, along with a previously uncharacterized gene, SAGT1, which showed the highest fold-change under high-salt conditions. Given that SAGT1 encodes a putative glycosyltransferase7, we hypothesize that SAGT1 a critical role in regulating the glycosylation and stability of the SOS1 transporter, thereby modulating salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Previous studies have established that the SOS pathway, particularly the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter SOS1, is central to plant salt tolerance8. However, despite extensive work on transcriptional regulation of SOS1, much less is known about post-translational mechanisms that govern its stability and activity. Glycosyltransferases have recently emerged as important modulators of membrane protein quality control and abiotic stress adaptation in plants9. This raises the possibility that a salt-inducible glycosyltransferase such as SAGT1 could directly influence SOS1 function through protein glycosylation.

To investigate this, we generated SAGT1 knockout lines using CRISPR-Cas9 and examined their responses to salt stress at phenotypic, transcript, and protein levels. Our findings suggest a novel regulatory role for SAGT1 in modulating SOS1 glycosylation and highlight the potential of glycosylation-targeted strategies for enhancing plant stress tolerance.

Specific Aims

- To investigate the expression patterns of SAGT1 under salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana.

- To assess the functional impact of SAGT1 knockout on SOS1 glycosylation and salt tolerance.

- To explore the mechanistic link between SAGT1-mediated glycosylation and SOS1 stability using biochemical assays and genetic complementation.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds (Col-0) were surface-sterilized and germinated on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium. The plants were grown under a 16-hour light/8-hour dark cycle at 22°C. After germination, seedlings were transferred to MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose, 0.8% agar, and adjusted to pH 5.7. To induce salt stress, seedlings were grown on MS media with increasing concentrations of NaCl (0, 50, and 100 mM) for a duration of 10 days.

Experimental Design, Replication, and Randomization

All salt-stress assays were conducted in three independent biological replicates, each consisting of at least 15 seedlings per treatment group. For each replicate, seedlings were germinated and grown on separate plates to ensure biological independence. The values presented in figures (n = 3) indicate biological replicates, not technical repeats. Seedlings were randomly assigned to NaCl treatment conditions (0, 50, or 100 mM) across plates to minimize positional or plate effects. Phenotypic measurements (e.g., primary root length, chlorosis scoring) were performed by two independent investigators in a blinded manner, such that the treatment identity of each sample was concealed until after measurements were completed.

RNA and Protein Extraction

Total RNA and proteins were extracted from seedlings grown under salt stress conditions. For RNA extraction, samples were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). For protein extraction, seedlings were homogenized in protein extraction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to measure the expression of SAGT1 under salt stress. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR was carried out using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad) with specific primers for each gene. UBQ10 was used as a reference gene for normalization.

| Gene name | Sequences (5’ -> 3’) |

| SAGT1_Forward | CTCGTGCCCAACTACAATCG |

| SAGT1_Reverse | CTCGTCCTTCATCGCCTTTG |

| SOS1_Forward | TGGTGTTACTTGCTGTCCCT |

| SOS1_Reverse | TGGAAAACAACAATCGCCGT |

| NHX1_Forward | CACAGATGTACGCGGGAATG |

| NHX1_Reverse | ACGTATACTGTCAGGCCGAG |

| UBQ10_Forward | TGGTGGTTTGTGTTTTGGGG |

| UBQ10_Reverse | GAGTCGAGTCACTTTGCAGG |

Gene Expression Analysis and RNA-seq

For quantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by DNase I treatment and cDNA synthesis with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Gene expression was quantified using SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Ubiquitin10 (UBQ10) were used as reference genes for normalization, and all reactions were performed in triplicate. Relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

For transcriptome analysis, RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit, and sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform, generating approximately 30 million paired-end reads (2 × 150 bp) per sample. Raw reads were quality-checked with FastQC and trimmed using Trimmomatic. Clean reads were aligned to the Arabidopsis thaliana TAIR10 genome using HISAT2 with default parameters. Gene expression counts were obtained with featureCounts, and differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 with thresholds of |log₂ fold change| ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis was conducted using the AgriGO v2.0 toolkit.

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Knockout of SAGT1

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of SAGT1 was performed by designing guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the first exon of the gene to induce frameshift mutations. Two independent gRNAs were selected based on minimal predicted off-target effects using CRISPOR. The gRNAs were cloned into the pCas9 binary vector, which was subsequently introduced into Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 plants via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated floral dip.

Transformed plants were selected on MS medium containing the appropriate antibiotic, and T1 seedlings were screened for successful integration. Sanger sequencing of the target locus was performed to confirm the presence of indels, and three independent knockout lines (sagt1-1, sagt1-2) were established.

For each line, three independent biological replicates were used for downstream phenotypic, RT-qPCR, and protein analyses, with each replicate consisting of ≥15 seedlings per treatment condition. To minimize positional effects, seedlings were randomly assigned to treatment plates, and all measurements were performed in a blinded manner. Potential off-target sites predicted in silico were PCR-amplified and sequenced, and no unintended edits were detected in the analyzed loci.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was used to assess protein levels of SOS1 in wild-type and SAGT1 knockout lines under salt stress. Seedlings were treated with 100 mM NaCl for 10 days to induce stress. Total protein was extracted from rosettes using a protein extraction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher).

Proteins (30 µg per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore) using a semi-dry transfer system at 15 V for 1 hour. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour at room temperature.

Membranes were probed with custom-produced antibodies against SOS1 (dilution 1:1000) and Actin (dilution 1:5000, used as a loading control). The SOS1 antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Kim. Its specificity had been confirmed by testing against wild-type and SOS1 knockout Arabidopsis thaliana lines (data not shown).

After overnight incubation at 4°C, membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000 dilution, Thermo Fisher) for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using chemiluminescent detection (Pierce ECL, Thermo Fisher) and quantified using a Bio-Rad Chemidocimaging system. Band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ software, and normalized to UBQ10 levels for comparison.

Pull-Down Assay

To investigate the glycosylation of SOS1, pull-down assays were performed with a glycosylation-specific lectin to capture glycosylated proteins from total protein extracts. The eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blot to determine SOS1 glycosylation levels.

Tunicamycin Treatment

To restore SOS1 glycosylation in SAGT1 knockout plants, seedlings were treated with tunicamycin. Plants were grown on media supplemented with tunicamycin, and protein levels of SOS1 and NHX1 were analyzed by Western blot.

Results

Dose-Dependent Salt Stress Response in Arabidopsis thaliana

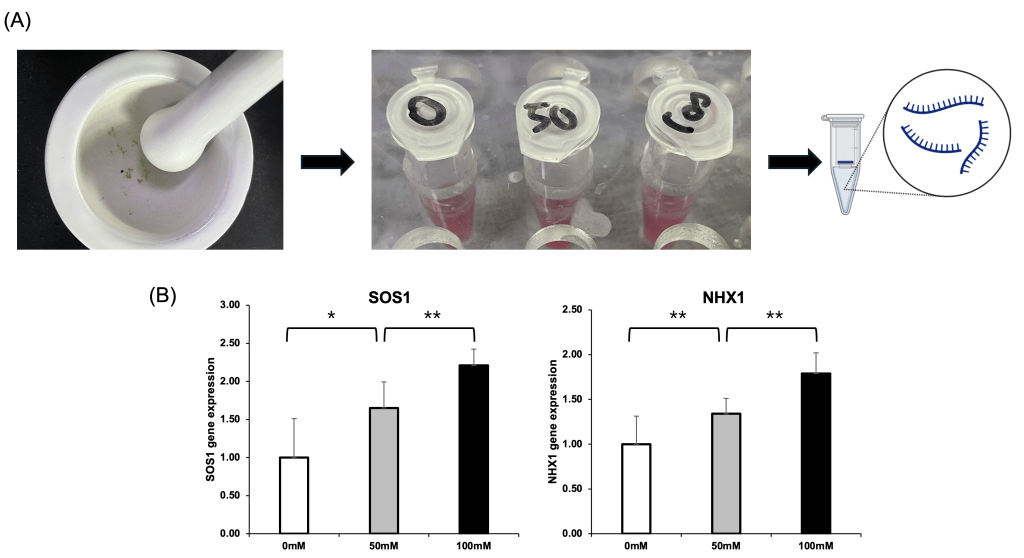

To assess the phenotypic effects of salt stress on Arabidopsis thaliana, seedlings were grown under three different NaCl concentrations (0, 50, and 100 mM). As salt concentration increased, clear signs of growth inhibition were observed, including reduced root elongation, chlorosis, and overall developmental delay (Fig. 1B and C). At 100 mM NaCl, plants exhibited severe bleaching and a decrease in primary root length (Fig. 1D). A two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of salt treatment (F(2,12) = 45.3, P < 0.0001, η² = 0.79). Post hoc Tukey’s tests indicated that root length at 100 mM NaCl was significantly shorter than both 0 mM (P = 0.0021) and 50 mM (P = 0.0045). Data represent mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each with ≥15 seedlings. These stress-induced morphological changes were used to validate the effectiveness of the salt treatment and to select samples for transcriptomic analysis (Fig. 1A).

(B) Illustrations of seedlings grown under 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl, showing reduced growth and leaf discoloration with increasing salt, concentrations. (C) Photographs of seedlings on NaCl-treated media, confirming growth inhibition and bleaching under high salt conditions (D) Primary root length of 0, 50, and 100mM NaCl was measured at day 10 after seeding (mean ± SEM, n = 3, P < 0.05, two‐way ANOVA).

Salt-Induced Upregulation of SOS1 and NHX1 at the Transcript Levels in Arabidopsis thaliana

To validate the transcriptomic findings and assess salt-responsive gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels, total RNA and protein were extracted from Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings treated with 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 2A). Consistently, qRT-PCR showed elevated levels of SOS1 and NHX1 proteins under higher salt concentrations, confirming transcriptional upregulation is accompanied by transcript-level enhancement (Fig. 2B). These results support the role of these ion transporters in salt tolerance and validate their upregulation in response to increasing salt stress.

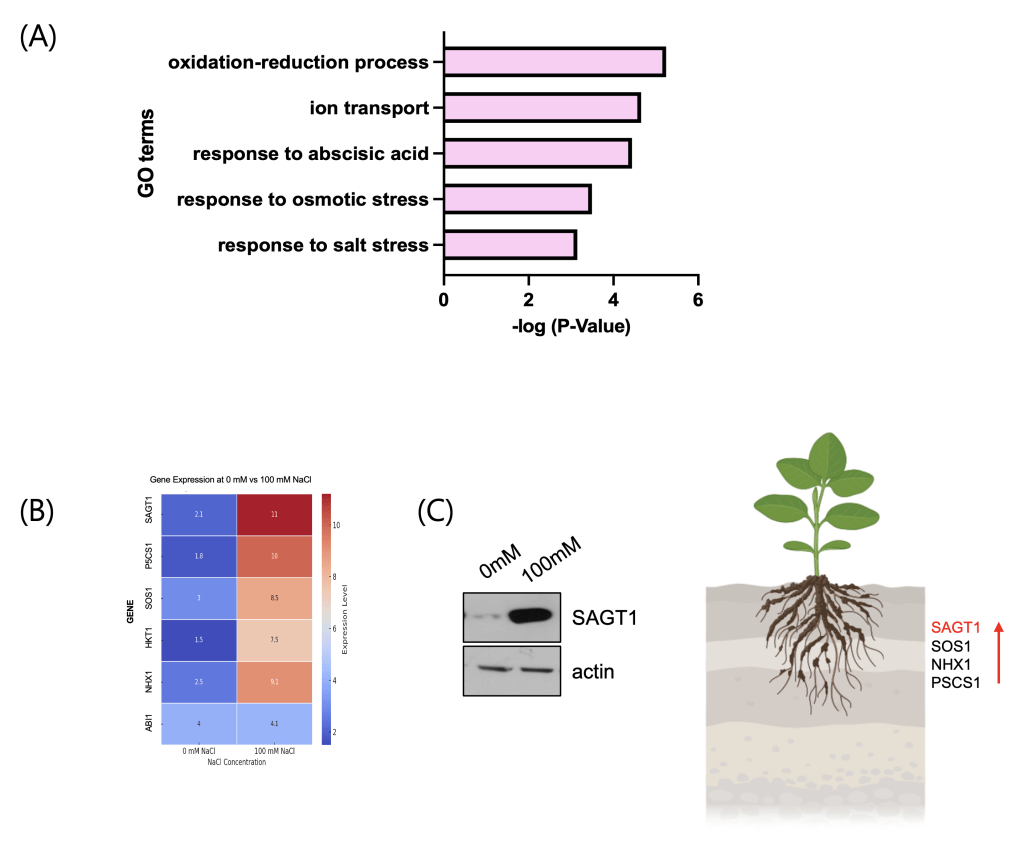

Transcriptomic identification of SAGT1 as a novel salt-inducible gene in Arabidopsis thaliana

RNA sequencing was performed to identify salt-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana under control (0 mM) and high-salt (100 mM NaCl) conditions. Pathway enrichment analysis revealed a significant upregulation of canonical salt stress–associated pathways, including ion transport, osmotic stress response, and abscisic acid signaling (Fig. 3A). Differential expression analysis further identified a set of known salt tolerance–related genes, including SOS1, NHX1, P5CS1, and HKT1, all of which were significantly upregulated. Notably, a previously uncharacterized gene, SAGT1, exhibited the most robust induction, with over 5-fold higher expression in 100 mM NaCl compared to the control (Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis confirmed that SAGT1‘s expression level surpassed those of canonical salt tolerance genes, suggesting its potential role as a novel regulator of salt stress adaptation (Fig. 3C).

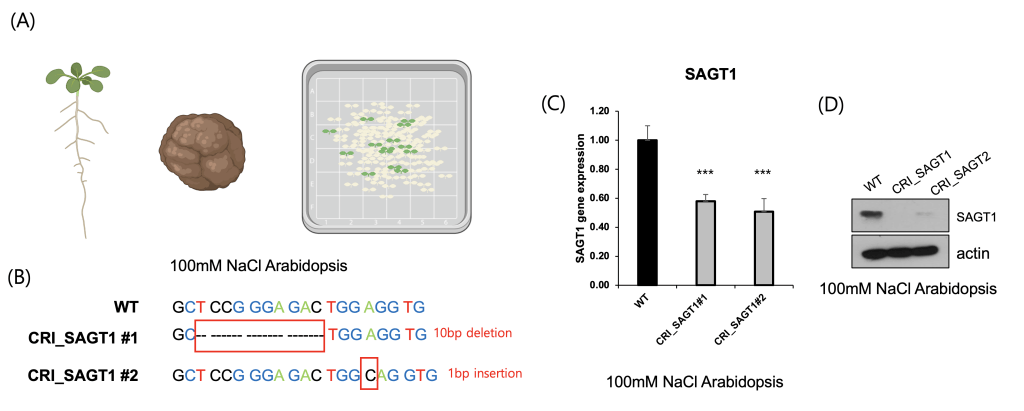

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout of SAGT1 Impairs Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana

To functionally validate the role of SAGT1 in salt stress tolerance, we generated CRISPR-Cas9–mediated SAGT1 knock-out lines in Arabidopsis thaliana. Transformed lines were selected on antibiotic-containing media, and mutations were confirmed by sequencing (Fig. 4A). Sanger sequencing confirmed a 10-bp deletion in the first exon of SAGT1, resulting in a frameshift mutation (Fig. 4B). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that SAGT1 was 60% downregulated upon knockout. Immunoblot analyses further confirmed loss of SAGT1 transcript and protein expression in the knockout lines (Figs. 4C and D). These results demonstrate that SAGT1 is essential for maintaining salt tolerance and plant viability under high-salt conditions.

Investigation of SAGT1‘s Role in SOS1 Glycosylation

SAGT1 is a protein belonging to the glycosyltransferase family10 and is hypothesized to play a role in regulating glycosylation. The SOS pathway, particularly the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter SOS1, is well established as a central regulator of salt stress tolerance in plants8. While previous studies focused mainly on transcriptional regulation of SOS111, glycosyltransferases have been reported to modulate membrane protein stability and activity in plants, suggesting a possible role in post-translational regulation12.

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether SAGT1 facilitates the glycosylation of ion transporters such as SOS1, thereby aiding their membrane trafficking, protein stability, and functional activation.

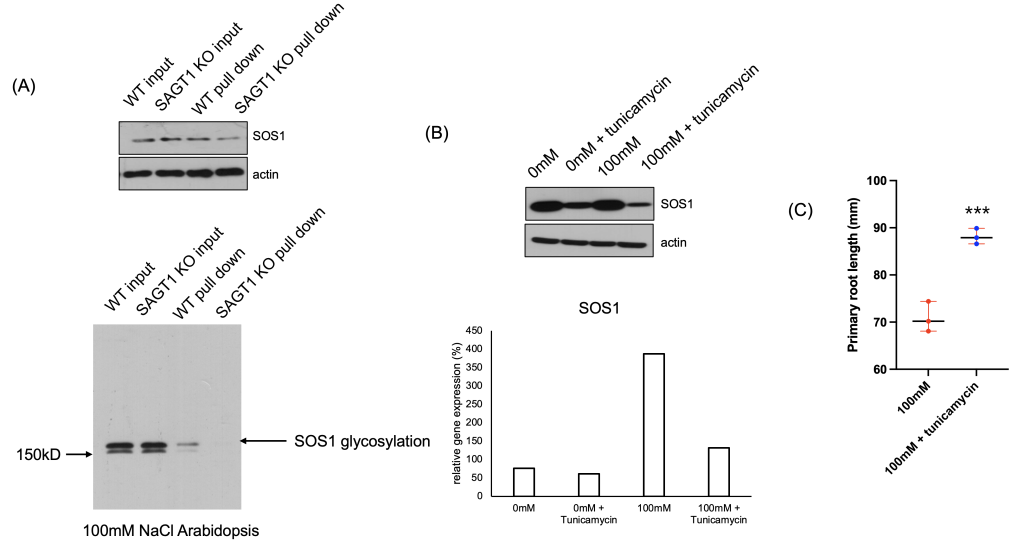

We hypothesized that if SAGT1 assists in the glycosylation of SOS1, the functionality of SOS1 would be fully activated. To test this, we performed a pull-down assay and found that in SAGT1 knock-out plants, SOS1 glycosylation was significantly impaired (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that SAGT1 plays a crucial role in SOS1 glycosylation, and its deficiency negatively impacts SOS1 functionality.

After confirming that SAGT1 is essential for SOS1 glycosylation, we aimed to inhibit this glycosylation defect by treating 100mM NaCl Arabidopsis with tunicamycin 1 μM. We hypothesized that restoring SOS1 glycosylation in SAGT1-KO would improve salt tolerance. Following treatment, we assessed the phenotypic recovery of the plants and performed Western blot analyses to confirm the restoration of functional activity of SOS1 and NHX1 (Fig. 5B and C).

Discussion

In recent years, due to the rapidly changing climate and diverse growing environments, complex stress situations in which biotic and environmental stresses act simultaneously are becoming increasingly common in real farms. In particular, environmental stresses such as high temperature, drought, and salt accumulation have a significant impact on crop growth and yield13‘14, requiring an understanding of the complex adaptive mechanisms of plants to cope with them15‘16.

In this study, we investigated the molecular and physiological responses of plants to salt stress using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model. Through progressive salt treatment experiments with 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl, we observed clear growth inhibition, chlorophyll loss, and tissue bleaching in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1). These phenotypes validated the salt stress model and enabled us to extract high-quality samples for transcriptomic analysis.

RNA sequencing revealed a consistent upregulation of canonical salt-responsive genes such as SOS1 and NHX1. Notably, SAGT1, a previously uncharacterized gene, showed the most robust induction under high-salt conditions. Previous studies found that SAGT1 belongs to the glycosyltransferase family7, implying a post-transcriptional regulatory defect.

Through pull-down and Western blot assays, we demonstrated that SAGT1 is involved in the glycosylation of SOS1, a process essential for its protein stability and functional activation (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, treatment with a tunicamycin partially inhibited the glycosylation in SAGT1-KO plants, leading to the restoration of SOS1 and NHX1 protein levels and improved phenotypic resilience under salt stress (Fig. 5B and C).

This study is the first to report that SAGT1 regulates salt stress adaptation via glycosylation-mediated post-translational control. While previous research has largely focused on transcriptional or hormonal signaling pathways in salt stress, our results reveal a novel mechanism at the protein quality-control level that is crucial for functional transporter stability and downstream stress mitigation. These findings introduce glycosylation as a key regulatory node that can be targeted to engineer stress-resilient plants.

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the precise glycan structures modified by SAGT1 remain unidentified, and further mass spectrometry–based glycoproteomic analysis will be required to fully elucidate the molecular mechanism. Second, although we observed glycosylation-dependent effects in Arabidopsis thaliana, it remains unclear whether SAGT1 orthologs exist and function similarly in major crop species such as rice or wheat. Third, while our CRISPR-Cas9 knockout approach strongly implicates SAGT1 in SOS1 glycosylation and salt stress responses, we cannot completely exclude off-target effects or secondary stress responses unrelated to glycosylation as contributors to the observed phenotypes. Finally, the tunicamycin treatment used to inhibit N-linked glycosylation is not optimized for field applications, and further work will be necessary to improve its stability, uptake, and cost-effectiveness for practical agricultural use.

Despite these limitations, our findings present a powerful conceptual advance: that targeted manipulation of glycosylation machinery can modulate membrane protein function to improve abiotic stress tolerance in plants. This opens the door to a new class of genetic and chemical strategies for crop improvement, particularly under extreme environmental conditions predicted to increase due to climate change.

Given the increasing global urgency for sustainable agriculture and food security, SAGT1 and its downstream pathway may represent a potentially interesting target for further investigation in developing climate-adaptive crops. However, as our study was conducted in Arabidopsis thaliana, further research is needed in crop species to determine whether similar mechanisms operate and can be harnessed effectively. This work broadens our understanding of plant stress biology and highlights the value of integrating molecular genetics with translational approaches, while acknowledging the current limitations and the preliminary nature of its applications to agriculture.

References

- Hansen, J., Sato, M., Ruedy, R. Perception of climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, E2415-E2423 (2012). [↩]

- Robert D. Field, Daehyun Kim, Allegra N. LeGrande, John Worden, Maxwell Kelley, Gavin A. Schmidt. Evaluating climate model performance in the tropics with retrievals of water isotopic composition from Aura TES. Geophysical Research Letters 41, 6030-6036 (2014). [↩]

- Verslues, P.E., Agarwal, M., Katiyar-Agarwal, S., Zhu, J., Zhu, J.K. Methods and concepts in quantifying resistance to drought, salt and freezing, abiotic stresses that affect plant water status. Plant J 45, 523-539 (2006). [↩]

- Kang, Y., Lee, K., Hoshikawa, K., Kang, M., Jang, S. Molecular Bases of Heat Stress Responses in Vegetable Crops With Focusing on Heat Shock Factors and Heat Shock Proteins. Frontiers in Plant Science Volume 13 – 2022(2022). [↩]

- Strasser, R. Plant protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 26, 926-939 (2016), Clarke, D., Williams, S., Jahiruddin, M., Parks, K., Salehin, M. Projections of on-farm salinity in coastal Bangladesh. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 17, 1127-1136 (2015), Nordio, G., Fagherazzi, S. Evapotranspiration and Rainfall Effects on Post-Storm Salinization of Coastal Forests: Soil Characteristics as Important Factor for Salt-Intolerant Tree Survival. Water Resources Research 60, e2024WR037907 (2024). [↩]

- Egamberdieva, D., Wirth, S., Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D., Mishra, J., Arora, N.K. Salt-Tolerant Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Enhancing Crop Productivity of Saline Soils. Frontiers in Microbiology Volume 10 – 2019(2019), Kumar, A., Singh, S., Gaurav, A.K., Srivastava, S., Verma, J.P. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria: Biological Tools for the Mitigation of Salinity Stress in Plants. Frontiers in Microbiology Volume 11 – 2020(2020). [↩]

- Dean, J.V., Delaney, S.P. Metabolism of salicylic acid in wild-type, ugt74f1 and ugt74f2 glucosyltransferase mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Plant 132, 417-425 (2008). [↩] [↩]

- Shi, H., Ishitani, M., Kim, C., Zhu, J.-K. The Arabidopsis thalianasalt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97, 6896-6901 (2000). [↩] [↩]

- Smith, L.G., Kirk, G.J.D., Jones, P.J., Williams, A.G. The greenhouse gas impacts of converting food production in England and Wales to organic methods. Nature Communications 10, 4641 (2019). [↩]

- Kumar, A., Singh, S., Gaurav, A.K., Srivastava, S., Verma, J.P. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria: Biological Tools for the Mitigation of Salinity Stress in Plants. Frontiers in Microbiology Volume 11 – 2020(2020). [↩]

- Zhu, J.-K. SALT AND DROUGHT STRESS SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION. Annual Review of Plant Biology 53, 247-273 (2002), Chinnusamy, V., Schumaker, K., Zhu, J.K. Molecular genetic perspectives on cross‐talk and specificity in abiotic stress signalling in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 55, 225-236 (2004). [↩]

- Strasser, R. Plant protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 26, 926-939 (2016). [↩]

- Hasanuzzaman, M., Bhuyan, M.H.M.B., Zulfiqar, F., Raza, A., Mohsin, S.M., Mahmud, J.A., Fujita, M., Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 9, 681 (2020). [↩]

- Tiwari, S., Prasad, V., Chauhan, P.S., Lata, C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Confers Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses and Modulates Plant Response to Phytohormones through Osmoprotection and Gene Expression Regulation in Rice. Frontiers in Plant Science Volume 8 – 2017(2017). [↩]

- Khan, N.A., Owens, L., Nuñez, M.A., Khan, A.L. Complexity of combined abiotic stresses to crop plants. Plant Stress 17, 100926 (2025). [↩]

- Yanqing Wu, Jiao Liu, Lu Zhao, Hao Wu, Yiming Zhu, Irshad Ahmad, Guisheng Zhou. Abiotic stress responses in crop plants: A multi-scale approach. Journal of Integrative Agriculture (2024). [↩]