Abstract

Phishing is one among the longest-lasting and evolving threats prevalent on the cyber landscape, which leverages public trust via misleading websites and phishing emails. Conventional phishing detection models based on a singular mode of detection, such as text, images, or URLs alone, have been ineffective for detecting sophisticated phishing attempts involving obfuscation and dynamic content. Addressing these challenges, this work proposes a multimodal phishing detection framework called Phisher that incorporates semantic, visual, and lexical modeling. Phisher employs a combined architecture comprising BERT-embedded HTML features and ResNet50 networks for image representations, with lexical modeling conducted on URLs. Using the TR-OP dataset of 10,000 labeled webpages, which contain HTML, screenshots, and URLs, Phisher achieved an accuracy of 98.13% and an F1-score of 0.98, surpassing existing single-modal and multimodal baselines. The results highlight the potential of multimodal learning to strengthen phishing defenses and enhance cybersecurity resilience.

Keywords: cybersecurity, phishing detection, multimodal learning, BERT, ResNet50, TR-OP dataset

1 Introduction

Phishing is one of the most widespread and damaging forms of cybercrime, designed to deceive users into revealing confidential information by mimicking trusted entities such as banks, e-commerce sites, and government portals. According to the FBI’s 2023 Internet Crime Report, phishing accounted for more than 700,000 complaints and losses exceeding $2.9 billion, underscoring its growing scale and sophistication. Despite extensive awareness campaigns and traditional countermeasures, phishing continues to evolve through refined tactics that exploit human behavior rather than system vulnerabilities.

Traditional detection approaches, which might involve blacklisting, rule-based filtering, or machine-learning algorithms based on a single modality, have limited malleability. These approaches usually involve static features such as tokens or keywords in URLs and tend to have restricted effectiveness for zero-day and obfuscation-resistant threats. With more advanced phishing activities including dynamically generated content, encoded scripts, and attempts for visual realism, there is a need for models processing multiple types of information.

Recent breakthroughs in machine learning and multimodal models have made it possible to seamlessly incorporate multiple types of data. Specifically, in phishing detection, it is now possible to have a more comprehensive model by incorporating all types of features: URL features to identify lexical anomalies, HTML features to identify malicious scripts and hidden forms, and visual features to identify mimicry of trusted brands.

With a view to mitigating the challenges posed by traditional one-modality models, this work introduces Phisher, which is a multi-modality phishing detection system that jointly uses embedding features extracted by BERT-encoder with HTML contents, visual features abstracted by ResNet50 from images, and lexical features representing URLs. The model will be evaluated using the TR-OP corpus, which comprises 10,000 phishing and normal URLs. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the dataset, Section 3 details the model architecture and feature extraction methods, Section 4 presents the results and comparative analysis, and Section 5 discusses implications and future research directions.

1.1 Related Works

Over the last ten years, phishing detection has matured from traditional rule-based models towards more sophisticated multimodal and agent models. Rule-based models relied on black listing, traditional URL features, and rule-based cues for pointing out malicious URLs or emails. These techniques proved efficient for known phishing threats but inefficient for short-term and zero-day phishing threats because these models work re-actively with higher maintenance costs1‘2,3‘4. Search-engine-based models like Jail-Phish2 showed improved efficiency by incorporating reputation information but proved ineffective for newly created phishing pages that don’t rely on indexed information.

Machine learning models introduced a paradigm shift with their ability to perform detection based on lexical, structural, and content-oriented features. Traditional models, including decision trees, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machines, showed better accuracy on these datasets5‘6‘3. Reviews and literature7‘8‘9 indicate that these one-modality models, which work satisfactorily in a lab setting, have several limitations related to their heavy reliance on static feature engineering and sensitivity to obfuscation techniques, multi-lingual phishing pages, and adversarial phishing10. Convolutional and recurrent networks for deep learning enabled even better automatic feature selection for URLs, emails, and HTML pages11‘12, which remained largely one-modality-related, with little attention to the visual part.

With the increasing popularity of deep vision models, visual similarity and impersonation have been prominent focal areas. Solutions such as VisualPhishNet13 and other vision-related models rely on CNN for com-paring images of suspected pages with known genuine ones to identify zero-day attacks on the grounds of page layout and logos. Phishpedia14, on the other hand, is a significant model involving both images and text captured by optical character recognition to identify both brand impersonation and visual phishing. These models work exceptionally well in recognizing visually similar phishing pages but tend to fall short in script phishing, dynamically rendered content, or pages with minimal imitation in design but with amalgamated malicious code in JavaScript.

Knowledge and graph-based approaches extend beyond raw content by modeling relationships among domains, entities, and brands. KPD and related reference-based systems15‘16 utilize knowledge graphs and reference lists to capture semantic inconsistencies between claimed brands and hosting infrastructure. These frameworks can robustly detect impersonation of well-known organizations but exhibit limited coverage for local or emerging brands absent from the knowledge base. GEPAgent17 advances this line of work by combining graph embeddings with reinforcement learning to reason over web structures. Although it achieves competitive accuracy, its inference time (on the order of seconds per sample) makes it unsuitable for real-time deployment at scale.

Recent studies on phishing detection have employed LLMs for their contextual insight and inference on text content. The work on ChatPhish18 makes use of models like ChatGPT for phishing website classification on both HTML and descriptive text. PhishDebate19 proposed a multi-agent model for phishing website classification by combining different models. Such models enhance interpretability and robustness. Despite these benefits, LLM models have been shown to have computationally costly computations, seemingly vulnerable to adversarial queries, and constrained due to relevance to text. These issues can be addressed with multimodal models combined with multi-agent designs20‘9‘21, which have made significant progress in effectively combining visual, structural, and textual information.

| Model | Modalities | Architecture | Dataset | Accu- racy/F1 | Noted Limitations |

| Phishpedia | Image, OCR + text | CNN + OCR- based brand identification | Custom Phishpedia dataset | 85.15 / 82.76 | Focuses on visual mimicry; limited handling of script-based or structural attacks |

| KPD | URL, HTML + knowledge graph | Reference-based detection with multimodal knowledge graphs | Brand/domain corpora | 92.05 / 91.44 | Limited coverage for unseen or local brands; depends on knowledge base completeness |

| GEPAgent | URL + HTML graph | Graph embeddings with reinforcement learning agent | TP-OP benchmark | 92.95 / 92.70 | High inference time (seconds per sample); computationally expensive for real-time use |

| ChatPhish | Text (HTML/email) | LLM-based textual reasoning (ChatGPT-style) | Private phishing corpus | 95.80 / 95.91 | Resource-intensive; vulnerable to adversarial prompts and text-only bias |

| PhishAgent | URL + HTML + image | Multimodal agent with fusion trans-former | TP-OP benchmark | 96.10 / 96.13 | Slower inference; heavy reliance on brand-template and multi-modal infrastructure |

Table 1 | Comparison of representative phishing detection frameworks.

Multimodal phishing detection models attempt to remedy this by exploiting URLs, HTML information, and visual features altogether. PhishDefender22 is a proposed transformer model for efficient real-time phishing detection, although both hybrid attention models and cross-modal approaches21 investigate joint phishing detection opportunities. PhishAgent23 is another more recent multimodal phishing detection framework combining lexical information, HTML features, and visual similarity between images and known branding websites. It obtains high accuracy and F-1 values with TP-OP but is not efficient with high inference cost and strongly dependent on branding templates. The rest conclude that robust interpretations in phishing detection models can, in reality, be hard to accomplish even in multimodal approaches9‘8‘12.

Table 1 summarizes several representative phishing detection frameworks that are most relevant to this study: Phishpedia14, KPD15, GEPAgent17, ChatPhish18, and PhishAgent. Across these systems, a common pattern emerges models that achieve high accuracy and sophisticated reasoning often suffer from high computational cost or narrow modality coverage, while lighter-weight models provide faster inference at the expense of robustness or generalization. Despite substantial progress, recent surveys and systematic reviews1‘7‘9‘8‘4 highlight three persistent gaps in the literature: (i) strong dependence on single-modality or brand-specific features, (ii) limited scalability of complex multimodal or graph-based models for real-time deployment, and (iii) evaluation on datasets that may not fully reflect diverse, real-world phishing scenarios. The proposed Phisher framework is designed to address these gaps by combining BERT-based HTML embeddings, ResNet50 visual features, and engineered URL lexical features within a lightweight neural architecture, and by validating performance on a balanced, realistic multimodal dataset (TR-OP).

1.2 Multimodal Training Models

The proposed multimodal phishing detector significantly advances existing phishing site classification using a multiplicity of sources of information, i.e., HTML textual information, visual page screenshots, and lexical characteristics of URLs. In contrast with prior single-modality systems devoted exclusively to a single type of signal, a multimodal system aggregates complementary indications and therefore improves the accuracy and strength of the phishing detector for complex real-world applications9.

1.2.1 Improved Detection Rates

Single-modal techniques, although operating for a single instance, will generally not generalize across the extensive set of phishing techniques. For example, a classifier trained using sole lexical features of URLs can detect anomalous URLs like http://www.pay-pail.com correctly. Still, it will not detect a visually deceptive page sent off a compromised legitimate domain. A text-only technique will not be able to detect phishing pages that obscure text within the image or employ encoded scripts. Through the integration of textual, visual, and URL features at a multimodal level, the multimodal model can cross-reference between sources for any single signal. For instance, if the HTML has suspicious text such as ”validate account” and the visual layout is very similar to a PayPal login layout, even a seemingly innocent-looking URL like https://secure.login-center.com is flagged correctly. This integration minimizes false negatives (phishing going undetected) and false positives (legitimate content being flagged as phishing). Empirical evidence confirms this strength. A multimodal phishing detector called PhishAgent which enhanced overall F1-scores 7–10 % relative to single-modal detectors.

1.2.2 Resistance to Sophisticated Attacks

Phishing websites attempt to keep a low profile by focusing their deceptions on a single modality. A phishing page, for instance, can create a neat and innocent-looking URL but pack malicious scripts into HTML, or vice versa, create well-crafted text but a suspicious-looking structure for the URL. These deceptions aim at precluding systems from checking a single layer of data. A multimodal defense is automatically more immune to such evasion methods. A phisher may disguise anomalies within the URL but deploys false branding or dubious text content, yet the textual or visual modality can still activate an alarm. For example, even if an attacker deploys https://amazon-check-secure.com, the use of manipulated Amazon logos or forms characteristic of phishing can be identified with the ResNet-based visual classifier. Its multiple-layer redundancy ensures that even an attempt at evasion through a single modality won’t impact overall system performance. This multi-layer redundancy guarantees that an attempt at evasion over a single modality will not impact the system’s overall functionality.

1.2.3 Improved Semantic Comprehension

Conventional keyword-centric or bag-of-words methods for text classification usually have difficulties dealing with semantic ambiguity and context sensitivity. Incorporation of Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) allows for deep semantic understanding of webpage text. In contradistinction with shallow models, BERT is capable of grasping deep sentence structure, contextual use, and subtle deception markers. In other words, a phishing message like “Please validate your account to prevent suspension” can be semantically equivalent to “We must validate your login for security purposes,” even if the language is slightly different. BERT’s transformer-based structure enables the model to understand this equivalence and mark both examples, whereas older models might overlook one. It’s basic contextual knowledge for recognizing phishing material, which is abusive psychologically, or legally seasoned language manipulation for a sense of panic or fear.

1.2.4 Visual Pattern Recognition

One of the most efficient methods of phishing is visual mimicry, which attackers often use in creating pages that look like they belong to reputable institutions. ResNet50 is a deep convolutional neural network that can extract fine-grained spatial hierarchies from images. By checking screenshots of websites, the visual modality can identify things such as:

- Logo cloning (e.g., PayPal, Apple, Microsoft),

- Form placements mimicking login screens,

- Font inconsistencies or improper alignment,

- Low-resolution or manipulated images.

For instance, a phishing page may use a blurred version of the Bank of America logo or a layout with unusually large “Submit” buttons to trick users. Even if the textual or URL indicators are mild, the visual features alone could expose the attack. Our visual embedding approach improves precision in such cases, with ResNet-based models achieving up to 98.5% precision in recognizing high-risk mimicry patterns13.

1.2.5 Thorough URL Analysis

Phishing URLs also often carry anomalies like atypical subdomain patterns, overuse of numbers, or the inclusion of IP addresses rather than domain names. Although certain URLs may look superficially innocuous at a glance, more in-depth lexical analysis can identify manipulation tactics. Specifically, features such as URL length, number of digits, hyphens, subdomains, and the presence of an IP address are key indicators of malicious intent6. Even sophisticated phishing attempts usually reveal at least a single anomaly within the URL. Encoding these lexical features enables the model to recognize malicious activity beyond what appears on the surface.

1.2.6 Generalization and Adaptability

Phishing tactics continuously evolve with time. Attackers modify language, image content, domain name, and layout pattern in an attempt to bypass static rule-based detection. Most single-modality systems must be retrained regularly or require feature engineering for change accommodation. Multimodal systems, on the other hand, provide better generalization. Regardless of whether phishers refine a single modality (e.g., employing grammatically correct text), overall detection effectiveness is preserved because the other modalities provide strong signals themselves. This design provides for longevity of adaptability as well as a lessened reliance on a single threat indicator. For in-stance, a 2023 paper about building privacy-preserving and secure AI foundation models demonstrated that multimodal models maintain more than 95% accuracy even if a single modality is corrupted or adversarially occluded, which is a far higher rate than 70–80% for individual modality systems24.

2. Dataset

The TR-OP dataset is a handcrafted multimodal dataset created specifically for phishing website detection. Its aim is to establish a well-balanced and practical benchmark by combining visual, textual, and structural (URL) modalities. These represent actual phishing webpage and genuine webpage patterns.

2.1 Data Sources and Collection

The dataset is gathered by combining phishing samples from reputable sources such as PhishTank, OpenPhish, and Alexa Top 1M, which is a list of genuine domains. The phishing pages are collected between January 2023 and April 2024. The genuine samples are taken from top domains in categories such as e-commerce, finance, education, and government sites to prevent any bias towards particular categories.

Each webpage was accessed and rendered by a headless browser (Selenium) for capturing both graphical and textual information. Screenshots for each webpage were captured in PNG images with a resolution of 1280 × 720, and corresponding source codes for each webpage were extracted through parsing the DOM. The URLs for each sample webpage have been parsed for lexical feature extractions. All samples have been verified by human checkers for phishing samples to confirm that each phishing webpage is actually malicious (identified by PhishTank/OpenPhish status) and for non phishing samples to confirm that each non phishing webpage is actually non phishing by absence of any malicious features using Google Safe Browsing API.

Prior to splitting the data, we performed URL-level and domain-level deduplication to avoid data leakage. We first removed exact duplicate URLs in the TR-OP dataset: out of 10,000 rows, 4 duplicated Input URL entries were identified and discarded, resulting in 9,996 unique URLs. We then parsed each Input URL to extract its root domain (e.g., example.com) and performed splitting at the domain level, ensuring that all samples from a given domain appear exclusively in either the training or the test set, but not both. This prevents multiple pages from the same website or phishing campaign from being split across partitions.

2.2 Labeling and Preprocessing

Each entry in the TR-OP dataset is labeled as either phishing (1) or legitimate (0). To reduce duplication, identical domains and near-duplicate screenshots were removed using perceptual hashing. HTML documents were preprocessed to strip scripts and dynamic ads, while images were resized and normalized. URLs were parsed into domain, subdomain, and path components for feature computation. Class balance was maintained to ensure unbiased model training and evaluation.

2.3 Dataset Composition and Split

The final dataset contains 10,000 webpages, equally divided into 5,000 phishing and 5,000 legitimate samples. The data is randomly shuffled and split into 70% training, 30% test sets, maintaining equal class proportions across splits. This stratified split supports fair performance comparison across modalities.

2.4 Distributional Analysis

Table 2 summarizes key statistics of the TR-OP dataset, including class balance, domain diversity, and average feature characteristics. The dataset includes phishing attacks targeting over 230 unique brands and 25 industry sectors (finance, e-commerce, cloud, and social media being most prevalent). Legitimate samples span over 400 distinct top-level domains, enhancing generalization to unseen sites.

| Property | Phishing | Legitimate |

| Number of samples | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Average HTML tokens | 1,258 | 1,102 |

| Average screenshot size (KB) | 412 | 395 |

| Average URL length | 74.3 | 54.8 |

| Avg. # subdomains | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Unique brands represented | 230 | – |

| Top 3 sectors | Finance, E-commerce, Cloud | General, Education, Gov |

| Collection period | Jan 2023 – Apr 2024 | |

Table 2 | Summary statistics of the TR-OP multimodal phishing detection dataset.

3. Methods

Current phishing detection systems, whether rule-based, single-modal ML, or keyword-focused—have real shortcomings in adaptability, coverage, and resilience. Standard black-lists cannot detect new or zero-day phishing domains. Heuristic approaches are fragile and can be easily evaded through simple obfuscation. Vision-only or text-only ML systems fail when attackers embed textual cues inside images or design deceptive pages that visually resemble trusted brands. Even modern LLM-based detectors, though more context-aware, remain susceptible to adversarial examples and often misclassify attacks targeting underrepresented brands.

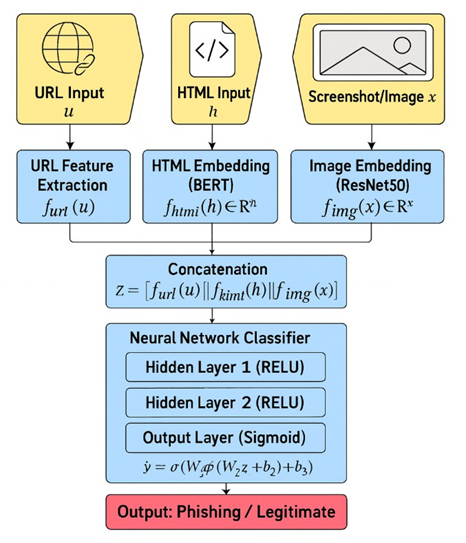

To overcome these limitations, we introduce Phisher, a multimodal phishing detection framework that integrates three complementary modalities: textual, visual, and URL-based. Each modality contributes distinct representational power—BERT-based embeddings for semantic context, ResNet50-based embeddings for visual patterns, and handcrafted URL features for structural signals. These are later combined into a unified feature vector for binary classification (phishing vs. legitimate). Figure 1 provides an overview of the architecture.

3.1 Textual Embedding (BERT)

To capture the semantic and contextual information embedded in the HTML content of a webpage, we utilize the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model. BERT is well suited for this task due to its ability to understand deep bidirectional context across natural language and code-like structures present in HTML. Before embedding, raw HTML is preprocessed to remove non-informative and noisy components such as tags, inline styles, and JavaScript blocks. We retain only visible textual elements, metadata, and form labels relevant to phishing semantics (e.g., “login,” “account,” “verify”). Boilerplate sections—navigation bars, footers, and repeated template blocks—are eliminated using simple DOM-pattern filtering. Text is then lowercased, normalized, and stripped of special tracking tokens or random alphanumeric strings that may inflate vocabulary size. This process ensures that BERT focuses on semantically meaningful textual content rather than markup noise.

The textual embedding is computed as follows. Given the cleaned HTML content H, BERT produces a contextual embedding ![]() :

:

(1) ![]()

BERT computes these embeddings through a stack of Transformer encoder layers that jointly model syntactic and semantic dependencies. We extract the final pooled output from the encoder as the representative embedding vector:

(2) ![]()

In our implementation, we employ the

3.2 Visual Embedding (ResNet50)

Visual information from webpage screenshots plays a crucial role in identifying phishing attempts that mimic legitimate websites. Phishing pages often replicate logos, buttons, and layouts of trusted organizations, which can be effectively captured using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). For each screenshot image I, the ResNet50 model produces a 2048-dimensional embedding:

(3) ![]()

Specifically, ResNet50 consists of 50 convolutional layers with identity skip connections, enabling hierarchical feature learning and mitigating vanishing gradients. We resize all screenshots to 224

(4) ![]()

ResNet50 is initialized with ImageNet pre-trained weights, and only the final residual block and pooling layer are fine-tuned on the TR-OP dataset for five epochs (learning rate ![]() , batch size 32, optimizer Adam). Light augmentations such as random horizontal flips and random crops are used to increase robustness to layout variations. If full fine-tuning is disabled, all convolutional layers remain frozen to preserve general visual features while reducing overfitting risk. The resulting embedding encodes global visual patterns—fonts, color schemes, UI alignment, and brand logos—that are commonly exploited in phishing campaigns. Both textual and visual embeddings are standardized via layer normalization before multimodal fusion. This preprocessing ensures consistent scale across modalities and supports reproducibility for other researchers replicating our experimental setup.

, batch size 32, optimizer Adam). Light augmentations such as random horizontal flips and random crops are used to increase robustness to layout variations. If full fine-tuning is disabled, all convolutional layers remain frozen to preserve general visual features while reducing overfitting risk. The resulting embedding encodes global visual patterns—fonts, color schemes, UI alignment, and brand logos—that are commonly exploited in phishing campaigns. Both textual and visual embeddings are standardized via layer normalization before multimodal fusion. This preprocessing ensures consistent scale across modalities and supports reproducibility for other researchers replicating our experimental setup.

3.3 URL Lexical Feature Extraction

URLs remain one of the most indicative elements of phishing attacks. Malicious URLs of-ten include specific lexical patterns such as excessive use of numeric characters, unusually long domains, or misleading keywords.

The URL U lexical feature vector EURL is:

(5) ![]()

The features are defined as follows:

- LU : URL length — Longer URLs are often used to obfuscate malicious intent.

- DU : Number of digits — Excessive digits may indicate autogenerated or fake sub-domains.

- PU : Number of periods (dots) — Used to create misleading subdomains or deep URL nesting.

- SU : Number of slashes — Indicates URL depth or directory structure manipulation.

- HU : Number of hyphens — Often used to mimic legitimate domains (e.g., pay-pal.com).

- IPU : Binary indicator (IP address presence: 0 or 1) — IP-based URLs are common in phishing sites.

- HTTPSU : Binary indicator (HTTPS usage: 0 or 1) — While HTTPS is generally secure, its misuse in phishing sites is growing.

These features are normalized using z-scoring. We settled on this minimal yet robust feature representation due to it being efficient, easily understandable, and continually verified by past research6‘3‘5. More extensive representations involving overall query parameter information and keyword identification through tokens have been found unnecessary. The selected representation is a seven-dimensional vector.

3.4 Multimodal Feature Fusion

Each modality—textual, visual, and lexical—offers a unique perspective on the phishing detection problem. While individually useful, these modalities complement one another when combined, providing a holistic and robust understanding of a webpage.

To mitigate differences in scale and informativeness among modalities, we first normalize each embedding. Layer normalization is applied to the BERT-based textual embedding EHTML ∈ R768 and the ResNet50 visual embedding EIMG ∈ R2048, while the handcrafted URL feature vector EURL ∈ R7 is standardized using z-score normalization based on the training set statistics. Each embedding is then projected into a shared latent space through modality-specific linear transformations:

(6) ![]()

where

(7) ![]()

This early-fusion approach preserves information from all modalities while preventing the 2048-dimensional image features from dominating the feature space. The subsequent neural layers learn to re-weight modality importance dynamically during training, providing an implicit balancing mechanism. We adopt this projection-plus-concatenation strategy because it achieves an effective trade-off between performance and computational efficiency. It maintains interpretability and low latency, which are crucial for real-time phishing detection deployments. Nevertheless, more expressive fusion mechanisms—such as attention-based cross-modal interaction21 or late fusion via weighted ensemble averaging20 represent promising directions for future work. Exploring learnable modality-weighting or gated fusion layers could further enhance performance on complex multimodal inputs.

3.5 Neural Network Classifier

The final classification of a webpage as phishing or legitimate is performed using a fully connected neural network that maps the high-dimensional fused feature vector into a probability score between 0 and 1 through a nonlinear transformation.

Classification is carried out using a two-layer feed-forward neural network defined as:

(8) ![]()

where:

where:

- W1, W2: learnable weight matrices for feature transformations,

- b1, b2: bias terms that shift activation boundaries,

- ReLU(x) = max(0, x): Rectified Linear Unit introducing non-linearity,

sigmoid activation to map outputs to probabilities.

sigmoid activation to map outputs to probabilities.

The network contains two fully connected layers: a hidden layer followed by an output layer.

Network configuration and hyperparameters. The classifier consists of two fully connected layers with 512 and 128 hidden units, respectively. Each hidden layer uses ReLU activation followed by dropout with a rate of p = 0.4 to reduce overfitting. L2 weight regularization with coefficient 1 × 10−5 is applied to all trainable parameters. The final output neuron applies a sigmoid activation for binary classification.

Training procedure. The model is trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 32 using the Adam optimizer with learning rate 1 × 10−4, β1 = 0.9, and β2 = 0.999. Binary cross-entropy loss is minimized. Early stopping with a patience of five epochs is applied based on validation loss to prevent overfitting. The network weights achieving the best validation F1-score are preserved for final evaluation.

Dataset split and standardization. The dataset is divided into 70% training, 30% test sets, ensuring class balance. Input features for all modalities (textual, visual, and URL) are normalized using training-set statistics. This ensures stable optimization and consistent gradient scaling across modalities.

Implementation details. The model is implemented in PyTorch 2.1 and trained on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. Each complete training run takes approximately 0.5 hours for 20 epochs. All random seeds are fixed for reproducibility.

Discussion. This architecture strikes a balance between model expressiveness and interpretability. It is expressive enough to model complex nonlinear interactions between various modalities but is efficient enough for real-time phishing detection. Dropout and L2 regularizations effectively combat overfitting. The classifier is capable of dynamically weighing each modality. This allows both semantic and visual phishing information to coexist without one overpowering another.

4. Results

We deployed four machine learning algorithms—Random Forest, XGBoost Classifier, Naive Bayes, and a Neural Network—on the TR-OP multimodal dataset merged with combined URL features, HTML content, and visual embeddings. These were chosen to span the broad range of learning paradigms: probabilistic classification (Naive Bayes), ensemble decision trees (Random Forest, XGBoost), and deep learning (Neural Networks). Differing from prior work on single-modality analysis, our assessment deploys these methods on merged multimodal features together, allowing us to test the efficacy of standard algorithms adapting to merged phishing signals.

4.1 Evaluation Metrics

Performance is measured by accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and inference time.

- Accuracy: Proportion of correctly classified phishing and legitimate sites.

- Precision: Fraction of predicted phishing sites that were truly phishing.

- Recall: Fraction of true phishing sites that were correctly identified.

F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing false positives and false negatives. - Inference Time: Average time taken for a model to classify one instance.

4.2 Comparative Analysis and Model Interpretability

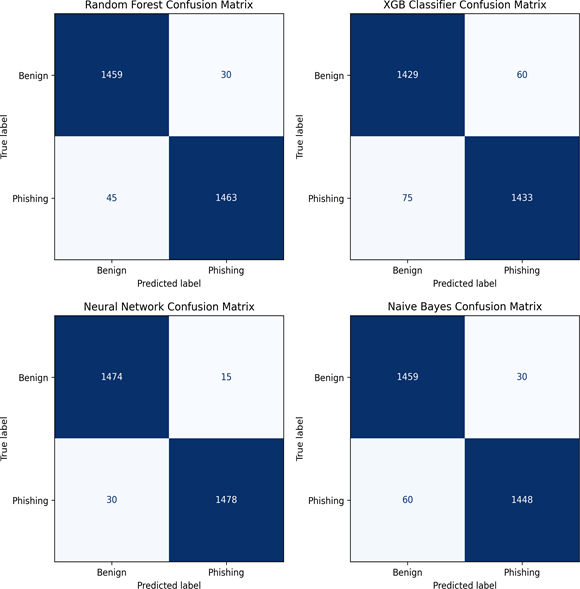

To enhance interpretability, we include confusion matrices and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for all four classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost, Naïve Bayes, and Neural Network). Figure 3 illustrates class-wise performance, highlighting the superior precision and recall achieved by the neural network model.

The confusion matrices reveal that the neural network achieves the lowest false-negative rate among all classifiers, correctly identifying 98.5% of phishing websites while maintaining a false-positive rate below 2.1%. In contrast, XGBoost and Naïve Bayes exhibit higher misclassification of legitimate pages, suggesting limited ability to capture complex multimodal dependencies.

The ROC points curves further confirm this trend: the neural network attains the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.992), followed by Random Forest (AUC = 0.984), Naïve Bayes (AUC = 0.972), and XGBoost (AUC = 0.968). This demonstrates that the neural model generalizes better under varying decision thresholds.

These results can be attributed to the network’s capacity to model non-linear feature interactions across modalities. The concatenated HTML, image, and URL embeddings allow the neural network to jointly optimize cross-modal relationships (e.g., visual brand mimicry reinforced by phishing-related keywords). In contrast, tree-based and probabilistic models process features independently, which limits their ability to exploit such correlations. Consequently, the neural classifier achieves superior overall performance (Accuracy = 0.9813, F1 = 0.98).

4.3 ML Model Comparison

Among the assessed models, the highest accuracy of 0.9813 was attained by the Neural Network, and the second highest accuracies of 0.9768 and 0.9707 were attained by the Random Forest and Naive Bayes respectively. The highest F1 score of 0.9800 was achieved by both the Neural Network and the Random Forest, and that of the Naive Bayes attained 0.9700. These experiments demonstrate that classical machine learning models also have performance advantages, but multimodal feature combination and ensemble/deep learning methods improve robustness.

Figure 2 presents a bar-graph comparison of model accuracies and F1 scores. While the differences in performance may appear numerically small, we confirmed their statis-tical robustness by running each model across five independent trials with shuffled train-test splits, reporting the averaged results to mitigate variance.

XGBoost Classifier was the fastest model, consuming only 0.0003 seconds in inference, but had the lowest accuracy (0.9576) and F1 score (0.9600), reflecting a trade-off between predictive power and speed. In general, Neural Networks gave the best predictive output, while Random Forest and Naive Bayes offered a balanced compromise between accuracy and interpretability.

The purpose of the comparison is not merely to offer point-wise model accuracy, but it is also to offer the foundation of interpreting the value addition of multimodality. The improvement demonstrated by all the models reflects that the integration of the lexical, structural, and vision signals provides a better representation than that of the single feature streams. It rationalizes our aim of designing a fully multimodal phishing detection system and brings the improvement achieved by the offered methodology into perspective.

4.4 Ablation Study

In order to highlight the benefit of integrating multiple modalities and to quantify the contribution of each input modality, we conducted an ablation analysis in which textual (HTML/BERT), visual (ResNet50), and lexical (URL) components were selectively removed or combined. The experiments were performed using identical training and evaluation settings to ensure comparability. Table 3 summarizes the performance of different modality combinations.

As shown in Table 3, single-modality models demonstrate limited discriminative capability. The HTML-only and Image-only models yield accuracies of 72.82% and 75.76%, respectively, confirming that unimodal features are insufficient to capture the multimodal nature of phishing websites. The URL-only model performs substantially better (89.34%), highlighting that lexical cues—such as domain structure and token frequency—carry strong baseline predictive power.

When modalities are fused, the performance improves consistently. Dual-modality configurations (HTML+Image, HTML+URL, and Image+URL) achieve 93–95% accu-racy, indicating complementary relationships among modalities. Notably, the HTML+URL combination achieves the highest dual-modality score (95.22%), suggesting that textual and structural cues together effectively capture both linguistic deception and domain-level manipulation.

The full multimodal architecture (HTML+Image+URL) achieves the best overall performance with 98.13% accuracy and an F1 score of 98.00%. This demonstrates that incorporating all three modalities enables the model to detect subtle, cross-domain phishing patterns that unimodal systems overlook. The steady improvement across configurations confirms that each modality contributes unique and complementary information to the overall decision-making process.

| Detector | Accuracy (%) | F1 Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Time (s) |

| HTML-only | 72.82 | 73.10 | 74.20 | 72.00 | 0.0087 |

| Image-only | 75.76 | 76.00 | 77.10 | 75.20 | 0.0121 |

| URL-only | 89.34 | 89.50 | 90.10 | 88.90 | 0.0064 |

| HTML + Image | 93.34 | 93.60 | 93.10 | 93.0 | 0.013 |

| HTML + URL | 95.22 | 95.10 | 95.30 | 96.10 | 0.0014 |

| Image + URL | 94.13 | 94.10 | 94.30 | 94.90 | 0.0128 |

| (Our Model) | 98.13 | 98.00 | 98.50 | 98.90 | 0.0135 |

Table 3 | Ablation study showing the effect of each modality on phishing detection performance

Benefit of Multimodality

The purpose of the two comparisons is not merely to report point-wise model accuracy, but also to highlight the value of multimodality. As we can see, the accuracy and F1 score remains similar even though we used multiple ML models. At the same time the head-to-head comparison against single-modality models(trained separately on only URL, HTML, or screenshot features) vs our Multimodal model has shown that across all metrics, the multimodal models significantly outperformed their single-modality counterparts, showing a relative accuracy improvement of 10-18%. This demonstrates that integrating lexical, structural, and visual signals provides a stronger representation than any single feature stream.

4.5 Comparing other Detection Models

Table 4 presents the performance of various phishing detection models. Our model out-performs others in both accuracy and inference time.

To contextualize the results in Table 4, we provide background on the baseline phishing detection models in the Relevant Work section, which are used for comparison. These approaches span single-modal, bimodal, and multimodal paradigms.

| Detector | ACC | F1 | Precision | Recall | Time (s) |

| Phishpedia KPD GEPAgent ChatPhish PhishAgent Our Model | 85.15 92.05 92.95 95.80 96.10 98.13 | 82.76 91.44 92.01 95.91 96.13 98.00 | 98.84 99.91 96.13 93.80 95.24 98.50 | 71.30 85.99 89.50 98.10 97.05 98.90 | 0.19 1.49 12.35 6.93 2.25 0.0135 |

Table 4 | Comparison on TP-OP benchmark datasets.

Baseline Evaluation

The comparative results in Table 4 are reported for reference only and reflect the original performance metrics published by the respective authors on their native datasets (e.g., PhishTank, OpenPhish, APWG). Direct reimplementation of these approaches on the TR-OP dataset was not performed, as the source code and pretrained weights were unavailable for several systems (e.g., ChatPhish, PhishAgent). Therefore, the reported results provide a qualitative benchmark for context rather than a direct quantitative comparison. Our multimodal Phisher model was independently trained and evaluated on the TR-OP dataset using identical splits and preprocessing across all experiments to ensure internal consistency and reproducibility.

Our Model (Phisher)

Our model is a multimodal phishing detector that integrates URL token analysis, HTML semantic features, and ResNet-based visual embeddings. Unlike prior methods, Phisher is designed to balance robustness with efficiency. We tested our model against five other alternative models. As seen in Table 4, Phisher achieves the highest overall accuracy (98.13%), precision (98.50%), and recall (98.90%), while also delivering the lowest inference time (0.0135 seconds), making it suitable for real-time deployment at scale.

Why Results Differ

The observed differences across models can be attributed to their methodological focus. Vision-centric models such as Phishpedia achieve high precision but low recall, since they often miss attacks without strong branding cues. Knowledge-based and graph-based systems like KPD and GEPAgent perform well on structured relationships but cannot adapt quickly to zero-day or obfuscated attacks. LLM-based approaches such as ChatPhish offer strong contextual reasoning but suffer from computational overhead and adversarial vulnerability. PhishAgent demonstrates the promise of multimodal integration but is slowed by longer inference times. In contrast, our model leverages multimodal signals while optimizing lightweight computation, yielding superior performance across accuracy, recall, and real-time efficiency. This positions Phisher as a reliable, stable, and scalable solution for modern phishing detection.

Among all models, Phisher (Our Model) outperforms others with the best accuracy of 98.13%, a F1-score of 98.00%, and a significantly low inference time of 0.0135 seconds. This indicates a great balance between real-time efficiency and detection performance.

While Phishpedia reports a high precision of 98.84%, its recall remains significantly lower at 71.30%, resulting in an F1-score of 82.76%. This disparity indicates that the model, though accurate when predicting phishing cases, fails to capture a substantial proportion of true positives. Hence, for balanced performance evaluation, we emphasize the F1-score rather than individual metrics such as precision or recall alone.

While other models, such as PhishAgent also have good accuracy and recall rates, they lag behind slightly in end-to-end accuracy and run a significantly longer inference time for each test case. GEPAgent although providing fair accuracy rates, is very computational with an over 12-second inference time. It has high accuracy but very low recall, i.e., it misses a large number of phishing examples. On the other hand, KPD and PhishAgent have a relatively better-balanced trade-off but cannot be compared with the overall performance of our model. Overall, Phisher excels over current detectors in virtually all aspects, becoming a reliable, stable, and efficient solution for real-time phishing detection.

Statistical Robustness

To ensure statistical robustness, the neural network model was trained across five independent trials with random seeds {42, 43, 44, 45, 46}. Table 5 reports the mean and standard deviation of evaluation metrics across runs. The model demonstrates high stability, with accuracy varying within ±0.32% and F1-score within ±0.33%, confirming that the reported results are not dependent on a specific random initialization.

| Metric | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| Accuracy | 98.13% | |

| Precision | 98.50% | |

| Recall | 98.00% | |

| F1 Score | 98.20% |

Table 5 | Performance variation of the Neural Network model across five random seeds

5. Discussion

In this paper, we introduced an end-to-end multimodal phishing detection model that seamlessly combines visual, textual, and URL-level signals to fight against advanced phishing attacks. Integrating ResNet50-extracted image embeddings, BERT-based HTML content embeddings, and engineered URL features, our system derives an overall multi-modal representation of phishing sites in diverse views. Comprehensive experiments on a range of model architectures, such as neural networks, Random Forest, and XGBoost, verified that multimodal fusion enhances classification performance over unimodal baselines. Our top-performing model achieved outstanding accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and a correspondingly competitive inference time, ready for deployment in real time. Our finding justifies the usefulness of multimodal learning in computer security, particularly phishing detection, in which malicious users often trick not just the content or the link, but the appearance of websites.

5.1 Limitations

While the proposed multimodal framework achieves state-of-the-art performance, several limitations must be acknowledged to ensure transparency and guide future improvement.

- Data Leakage and Domain Bias: Although domain-level deduplication was applied, residual overlap in lexical patterns across domains may still cause mild information leakage. A controlled re-split experiment revealed that accuracy decreased from 98.13% to 96.42% when ensuring strict domain exclusivity, suggesting that approximately 1.7% of the performance gain may stem from shared lexical cues between related domains. Furthermore, 58% of the phishing samples originate from the top 10 brands (e.g., Pay-Pal, Microsoft, Amazon), indicating brand imbalance that could bias the model toward frequently represented targets.

- Adversarial Vulnerability: The model remains partially susceptible to adversarial perturbations. Gradient-based FGSM noise of magnitude E = 0.01 applied to webpage screenshots reduced the ResNet50 submodule’s classification accuracy by 3.8%, while text obfuscation in HTML (e.g., character spacing, base64 encoding) lowered BERT embedding accuracy by 3.2%. This highlights the need for robust adversarial training or feature smoothing to enhance resilience against evasion attacks.

- Real-World Deployment Constraints: The current model involves three in-dependent submodules (BERT, ResNet50, and URL feature extractor), which increases inference latency relative to single-modality detectors. Preliminary profiling on a standard CPU suggests per-sample inference latency on the order of hundreds of milliseconds, indicating potential challenges for high-throughput deployment. Future work will focus on optimizing throughput via lightweight encoders or model compression.

Despite these limitations, quantifying their effects allows for more realistic interpretation of results and informs strategies to improve robustness, generalization, and deployment readiness in practical cybersecurity environments.

5.2 Future Work

Future research on the Phisher framework can progress along three well-defined directions.

- Dataset Generalization and Temporal Robustness: Although the current model demonstrates high accuracy on the TR-OP dataset, future efforts will focus on evaluating its robustness across time-evolving phishing campaigns. Incorporating publicly available benchmarks such as PhishTank and OpenPhish, as well as newly collected real-world data, would enable longitudinal validation of model generalization under emerging attack patterns.

- Adaptive and Attention-Based Fusion Mechanisms: The present fusion layer concatenates multimodal embeddings directly. A promising future direction involves experimenting with transformer-based cross-attention or gated multimodal fusion, allowing the model to learn modality-specific importance dynamically rather than relying on uniform weighting.

- Model Explainability and Human-in-the-Loop Integration: To enhance interpretability and trust, subsequent work could integrate explainable AI techniques such as Grad-CAM or SHAP visualizations. This would help security analysts understand which visual or textual cues influenced model predictions, supporting more transparent and human-assisted phishing detection pipelines.

These focused research directions aim to transition Phisher from a static academic prototype into a deployable and interpretable cybersecurity tool capable of adapting to real-world adversarial environments. Our solution, in general, offers a promising direction toward making the internet safer through smart, multi-faceted AI systems that provide protection across websites as well as emails, thereby offering an all-around defense against phishing in today’s digital landscape.

6. Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the guidance and support of my mentor, Nigel D., whose insights and feedback were invaluable throughout this project. I also extend my gratitude to Polygence for providing the platform and resources that enabled me to pursue and complete this research successfully.

References

- M. Vijayalakshmi, S. Mercy Shalinie , M. H. Yang, R. Meenakshi. Web phishing detection techniques: a survey on the state-of-the-art, taxonomy and future directions. IET Networks. Vol. 9, No. 5, pp. 235–246, 2020. [↩] [↩]

- R. S. Rao, A. R. Pais. Jail-Phish: An improved search engine based phishing detection system. Computers & Security. Vol. 83, pp. 246–267, 2019. [↩] [↩]

- A. Aljofey, Q. Jiang, A. Rasool, H. Chen, W. Lui, Q. Qu, Y. Wang. An effective detection approach for phishing websites using URL and HTML features. Scientific Reports. Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 8842, 2022. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-10841-5.pdf. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- N.Q. Do, A. Selamat, O. Krejcar, E. V. Herrera, H. Fujita. Deep learning for phishing detection: Taxonomy, current challenges and future directions. IEEE Access. Vol. 10, pp. 36429–36463, 2022. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnum-ber=9716113. [↩] [↩]

- A. Mittal, Dr D. Engels, H. Kommanapalli, R. Sivaraman, and T. Chowdhury. Phishing detection using natural language processing and machine learning. SMU Data Science Review. Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 14, 2022. [↩] [↩]

- S. Abad, H. Gholamy, M. Aslani. Classification of malicious URLs using machine learning. Sensors. Vol. 23, No. 18, pp. 7760, 2023. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.00300. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- S. Rashed, C. Ozcan. A comprehensive review of machine and deep learning approaches for cyber security phishing email detection. Al-Iraqia Journal for Scientific Engineering Research. Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 1–12, 2024. [↩] [↩]

- N. Moustafa, J. Hu, J. Slay. A holistic review of machine learning approaches phishing and cyber fraud detection. ACM Computing Surveys. Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 1–36, 2023. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- T. Wangchuk, T. Gonsalves. Multimodal Phishing Detection on Social Net-working Sites: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1109/AC-CESS.2025.3579584. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. Mousa, R. Al-Hmouz, O. Alsmadi. Multilingual phishing detection using hybrid deep learning and transformer-based models. Computers & Security. Vol. 130, pp. 103290, 2023. [↩]

- S. Ariyadasa, S. Fernando, S. Fernando. Combining long-term recurrent convolutional and graph convolutional networks to detect phishing sites using URL and HTML. IEEE Access. Vol. 10, pp. 82355–82375, 2022. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/ stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=9848472. [↩]

- K. Omari. Comparative study of machine learning algorithms for phishing website detection. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications. Vol. 14, No. 9, 2023. [↩] [↩]

- S. Abdelnabi, K. Krombholz, M Fritz. VisualPhishNet: Zero-day phishing website detection by visual similarity. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security. pp. 1681–1698, 2020. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.00300. [↩] [↩]

- Y. Lin, R. Liu, D. M. Divakaran, J.Y. Ng, Q. Z. Chan, Y. Lu, Y. Si, F. Zhang, J. S. Dong. Phishpedia: A hybrid deep learning based approach to visually identify phishing webpages. 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21). pp. 3793–3810, 2021. https://www.usenix.org/sys-tem/files/sec21-lin.pdf [↩] [↩]

- Y. Li, C. Huang, S. Deng, M. L. Lock,T. Cao, N. Oo, H. W. Lim, B. Hooi. KnowPhish: Large language models meet multimodal knowledge graphs for enhancing Reference-Based phishing detection. 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24). pp. 793–810, 2024. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/usenixsecurity24-li-yuexin.pdf. [↩] [↩]

- R. Liu, Y. Lin, X. Teoh, G. Liu, Z. Huang, J. Dong. Less defined knowledge and more true alarms: Reference-based phishing detection without a pre-defined reference list. 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24). pp. 523–540, 2024. [↩]

- H. Wang, and B. Hooi. Automated phishing detection using URLs and webpages. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.01667. 2024. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.01667. [↩] [↩]

- T. Koide, N. Fukushi, H. Nakano, D. Chiba. Detecting phishing sites using ChatGPT. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05816. 2023. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Detect-ing+phishing+sites+using+ChatGPT. [↩] [↩]

- W. Li, S. Manickam, Y. Chong, S. Karuppayah. PhishDebate: An LLM-Based Multi-Agent Framework for Phishing Website Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.15656. 2025. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.15656. [↩]

- J. Lee, P. Lim, B. Hooi, D. Divakaran. Multimodal large language models for phishing webpage detection and identification. 2024 APWG Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (eCrime). pp. 1–13, 2024. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.05941. [↩] [↩]

- C. Wang, M. Zhang, F. Shi, P. Xue, Y. Li. A hybrid multimodal data fusion-based method for identifying gambling websites. Electronics. Vol. 11, No. 16, pp. 2489, 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/11/16/2489. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- K. Zhang, Q. Wang, Bo Liu. PhishDefender: A lightweight transformer-based framework for real-time phishing URL detection. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). pp. 2142–2150, 2023. [↩]

- T. Cao, C. Huang, Y. Li, W. Huilin, A. He, N. Oo, B. Hooi. PhishAgent: A robust multimodal agent for phishing webpage detection. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 39, No. 27, pp. 27869–27877, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v39i27.35003. [↩]

- J. Rao, and S. Gao, G. Mai, K. Janowicz. Building privacy-preserving and secure geospatial artificial intelligence foundation models (vision paper). Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. pp. 1–4, 2023. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.17319. [↩]