Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between aesthetic dissatisfaction and interest in cosmetic dentistry among Gen-Z individuals in the United States, focusing on how aesthetic dissatisfaction with dental appearance influences the probability of reporting unmet dental care needs and seeking cosmetic dentistry. This is important since Gen-Z face growing social-media-driven aesthetic pressure, but there were only a few studies that connected these concerns to dental outcomes. This study seeks to answer the research question whether aesthetic dissatisfaction among Gen-Z individuals correlates with the interest in cosmetic dentistry and also in dental care needs. This study hypothesized that Gen-Z individuals with perceived dissatisfaction with dental appearance would have higher chance to seek cosmetic dentistry or report a challenge in assessing unmet dental care. To test this hypothesis, external appearance ratings and self-reported oral health measures were combined from large-scale datasets. By standardizing and aligning the aforementioned two datasets, a latent aesthetic dissatisfaction variable was generated for logistic regression modeling to calculate the probability of cosmetic interest or unmet dental care as a function of the latent score. Results strongly support the hypothesis. Individuals with lower aesthetic ratings consistently indicated higher predicted probabilities of cosmetic dentistry interest and unmet dental needs. These findings indicate a significant connection between aesthetic dissatisfaction and an increased level of interest in cosmetic dentistry and also unmet dental care among Gen-Z individuals.

Keywords: Gen-Z, aesthetic dissatisfaction, cosmetic dentistry, unmet dental care needs, dental appearance

Introduction

There has been a rising interest in cosmetic dentistry over the past decades, particularly among young adults due to a newly emerging digital media and visual culture1. Among many other generations, Gen-Z tends to be uniquely influenced by social media platforms (such as Instagram) and has been growing an interest concerning their personal appearance, creating their own subculture of aesthetic features – including dental appearance2. This new subculture has made cosmetic dental procedures, such as teeth whitening, increasingly marketed to this specific age group of Gen-Z individuals3. Cosmetic dentistry focuses on the aesthetics of teeth. In scholarly literature, cosmetic dentistry encompasses procedures designed to improve appearance, such as alignment, color, and shape, beyond the necessity of restoration. It blends clinical methods with aesthetic judgment4.

Aesthetic dissatisfaction has long been perceived as an important personal health behavior for people of all ages. In this study, aesthetic dissatisfaction specifically refers either to external ratings of facial beauty (SCUT) or self-reported oral appearance (NHANES). Studies have shown that people dissatisfied with their dental appearance had a higher chance of seeking cosmetic interventions5‘6‘7. However, most of the previous studies focused on adults as a main clinical population to analyze the relationship between aesthetic dissatisfaction and cosmetic dentistry. For instance, previous studies showed that dissatisfaction with dental aesthetics strongly predicted the demand of cosmetic treatment among adults8‘7. There were similar findings that have been reported in orthodontic and prosthodontics research9‘10. However, not many previous studies focused on Gen-Z, with most limited to descriptive surveys or social media influences instead of quantitative modeling11‘12. This indicates a clear literature gap for younger populations13. This gap is particularly relevant as Gen-Z may differ from older cohorts in their immersion in digital culture. Online images created by constant exposure to digital world may amplify the dissatisfaction of their appearances, which in turn may increase the demand for cosmetic dental treatment compared to adults whose motivations are often more functional.

Moreover, existing studies conducted for cosmetic dentistry and aesthetic dissatisfaction were based on descriptive surveys or clinical assessments rather than quantitative modeling in analyzing their relationship. Mathematical modeling is a powerful means to explore how changes in one variable can influence the other variable. According to existing studies14‘15, simulated datasets for mathematical modeling is an efficient method for analyzing the relationship between two variables if existing datasets were incomplete or not publicly accessible, provided that parameters in the simulations are well-grounded in prior empirical findings. In this study, simulation was used only where outcomes of cosmetic dentistry were absent, applying thresholds aligned to the distribution of dataset to preserve validity.

To fill the literature gap about Gen-Z individuals and their relationship with aesthetic dissatisfaction and cosmetic dentistry, this study combined literature-derived parameters for the statistical modeling and generated a mathematical model to explain how changes in aesthetic dissatisfaction influences interest in cosmetic dentistry. This research seeks to answer the research question about how aesthetic dissatisfaction correlates with the increased level of interest in cosmetic dentistry among Gen-Z individuals. This study hypothesized that lower aesthetic dissatisfaction (greater dissatisfaction) may be positively associated with interest in cosmetic dentistry.

Method

Study Design

In this study, two datasets were used to investigate if aesthetic dissatisfaction is correlated with the interest in cosmetic dentistry among Gen-Z individuals. One of them was from publicly available SCUT-FBP5500 dataset that was used to model aesthetic dissatisfaction according to the scores of facial beauty, while simulating potential interest in cosmetic dentistry. The second dataset was oral health questionnaires from 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) combined with demographics data to model self-rated oral aesthetics and self-reported access to dental care as a proxy for the interest in cosmetic dentistry. However, these variables captured general needs for oral health rather than elective cosmetic treatment. Utilizing a combination of image-based modeling and survey-based modeling, this study conducted a simulation after the data cleaning process.

Data Sources

SCUT-FBP5500 dataset contains a total of 5,500 frontal face images, and each of them is recorded a beauty score in a range from 1 (least attractive) to 5 (most attractive). As a widely used dataset in the research of computer vision and human perception, the beauty score in this dataset was used as a proxy in assessing external aesthetic dissatisfaction. People with lower beauty scores were considered to have low aesthetic dissatisfaction from an external view point. Although SCUT ratings measured overall facial attractiveness over dental features directly, prior research has indicated how dental appearance contributed significantly to facial esthetics and judgments of attractiveness16. Since the SCUT-FBP5500 dataset did not contain variables related to dental treatment, a simulation step was applied to approximate cosmetic interest in the absence of direct measures. I labeled 1 (“interested in cosmetic dentistry”) in the image when the beauty score was lower than 2.75, and 0 (“not interested”) in the image if the score was at or above 2.75. With this simulation step, I was able to apply a standard binary regression model to identify the relationship between aesthetic dissatisfaction and the simulated cosmetic interest variable.

The 2017 and 2018 NHANES oral health questionnaire was also used as a nationally representative survey conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to include self-reported oral health assessment and also information of people for their access to dental care. I downloaded the oral health questionnaires (OHQ_J.XPT) and the corresponding demographic file (DEMO_J.XPT), merged these two files according to respondent ID, and filtered the age into 10 to 30 to focus on Gen-Z in the dataset. This age range was specifically chosen to approximate Gen-Z in 2017-2018 (the ones born 1997-2008) to ensure that both younger adolescents and emerging adults within this generational cohort were included. Variables extracted were self-rated oral health (OHQ845) as a 5-point scale with 1 as excellent and 5 as poor and dental care inaccessibility (OHQ770) as a binary variable (1 as yes and 2 as no) showing if the respondent could not get dental care even though he or she needed it. The first variable was used as an inverse measure of aesthetic dissatisfaction. Based on this setup, the higher the self-reported scores on oral health, the lower the aesthetic dissatisfaction was. Aesthetic dissatisfaction was treated as aesthetic dissatisfaction for the clarity in the simulation. I treated this as an indicator of dental care inaccessibility for the interest in cosmetic dentistry that has not been met.

I cleaned the SCUT-FBP5500 dataset by extracting the image annotation from the entire file first, normalizing the beauty score and checking the possible outlier (no outlier detected, z-score > 3), and added binary variable based on the threshold: y variable with 1 if beauty score was under 2.75 and 0 otherwise. The cutoff of 2.75 approximated the lower quartile of the sample distribution (mean 2.99, SD 0.51). Thresholds based on quartile are frequently used in perception and aesthetics research when there are no clinical cutoffs. For NHANES dataset, I merged oral health questionnaires data with demographic data to filter the ages for Gen-Z in the age from 10 to 30, recoded the dental care inaccessibility to 1 as yes and 0 as no, and removed missing values in the rows to generate a valid sample for regression. Analyses were performed in R v4.3.0 using glm. Scored were standardized in z-scores, while handling missing data by listwise deletion.

Mathematical Modeling

I modeled the simulated cosmetic interest as a function of beauty score as follows.

![]()

Where Y is the simulated interest, and X is the beauty score. In this model, Y was coded as 1 = ‘interested in cosmetic dentistry,’ and 0 = ‘not interested in cosmetic dentistry,’ while X indicated the continuous beauty score as 1 = least attractive and 5 = most attractive. Maximum likelihood was used to estimate coefficients. All regressions were conducted in R v4.3.0 using the glm function with a logit link. All the variables were standardized as z-scores, while removing the missing cases, where appropriate, by using listwise deletion.

In addition, I used NHANES regression model to estimate the probability of reporting inaccessibility in dental care as a function of self-rated oral aesthetics as follows.

![]()

Where Z is the indicator of dental care inaccessibility, and A is the aesthetic dissatisfaction score. Here, Z was coded as 1 = ‘reported unmet need for dental care,’ and 0 = ‘no unmet need for dental care.’ A was measured on a 5-point scale with 1 as excellent and 5 as poor. Higher scores indicated greater aesthetic dissatisfaction.

Then, I standardized both aesthetic scores to combine both datasets as follows.

X1* = z score of SCUT beauty score

X2* = z-score of self-rated aesthetic dissatisfaction from NHANES

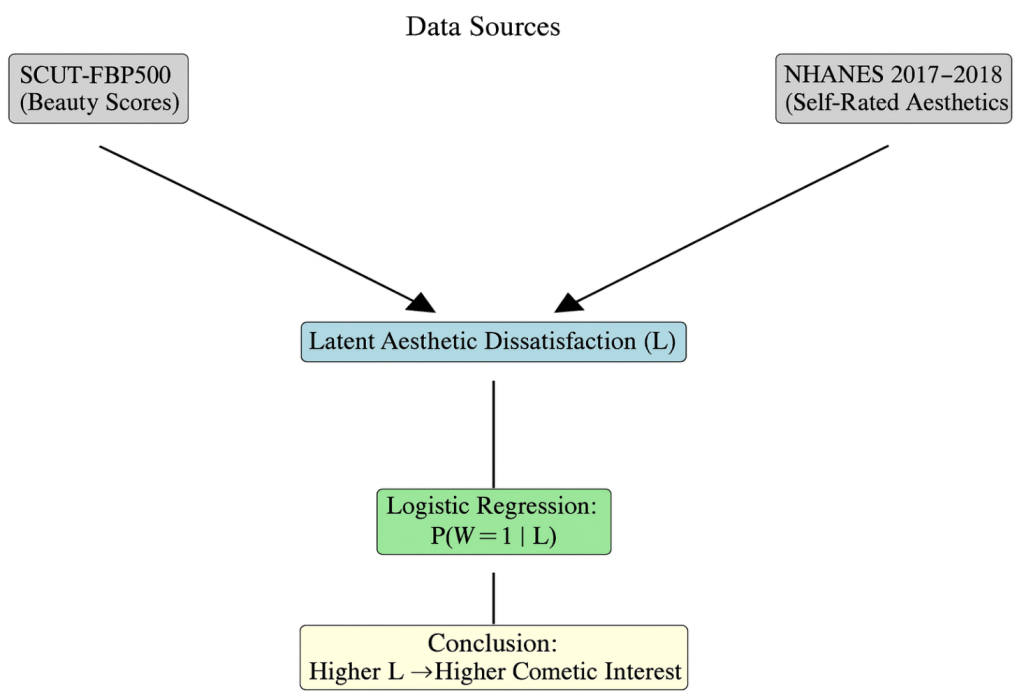

A latent dissatisfaction score (L) was calculated as an average of and Figure 1 illustrates the latent modeling approach I used to combine SCUT and NHANES datasets, emphasizing how aesthetic dissatisfaction was standardized and unified into a single predictive framework even though they were measured differently in the two dataset. By standardizing aesthetic dissatisfaction scores from two independent but complementary datasets, I overcame a common challenge in data incompatibility that was frequently shown in behavioral health modeling. This method was especially useful as there was no comprehensive dataset available. It is acknowledged that SCUT identified general facial attractiveness, while NHANES measured oral-specific perceptions. The latent framework was applied to connect them as a conceptual bridge.

Using them, I generated a predicted probability that a Gen-Z individual was interested in cosmetic dentistry (given his or her level of latent aesthetic dissatisfaction) as follows:

![]()

Where W=1 indicates how a Gen-Z individual was interested in cosmetic dentistry or showed dental needs as a proxy outcome, and L is the latent aesthetic dissatisfaction score calculated after integrating both datasets. This was a pseudo-latent index generated by averaging the standardized scores, not a formal latent model, such as SEM.

Latent framework was specifically used to conceptually integrate both datasets that measured related constructs and also broadened the evidence base, In addition, since both datasets were consistently mapped to the L (latent score), latent framework strengthened the validity in showing how the observed relationship in the simulation was not from data-specific noise.

Results

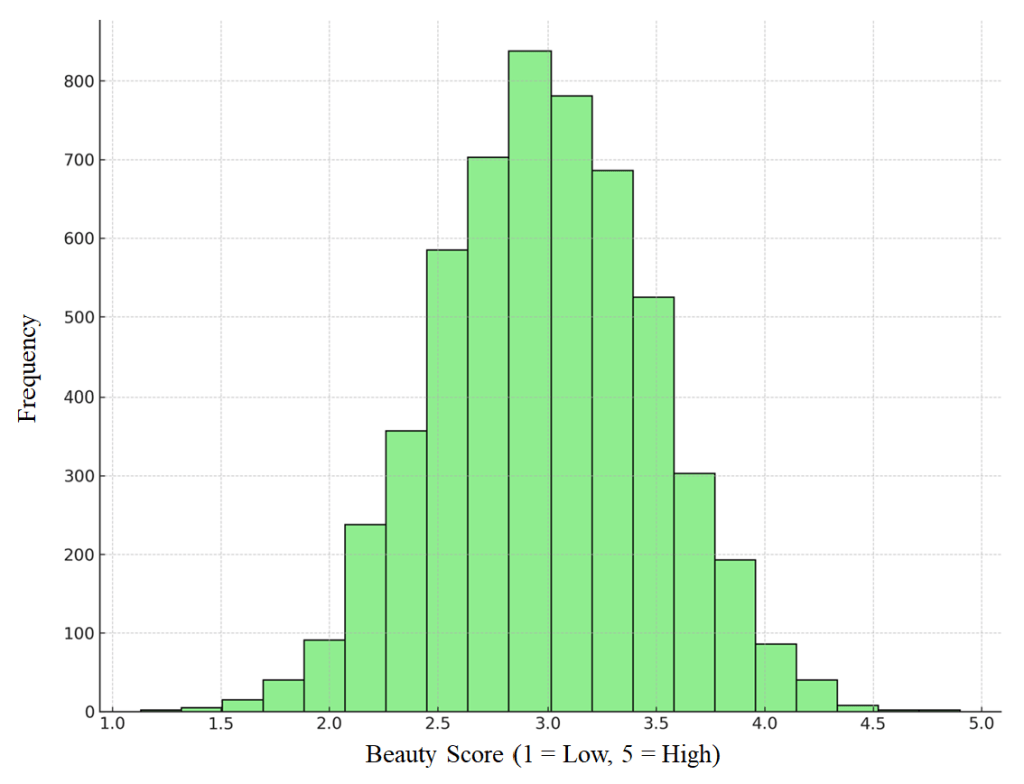

From SCUTFBP5500, I classified 2,460 images out of 5,500 to have a beauty score below 2.75, and labeled them as simulated interest in cosmetic dentistry. After applying the logistic regression, I labeled scores below 2.75 as “interested in cosmetic dentistry,” and scores above it as “not interested.” From a total of 5,500 images, the average beauty score was calculated to be 2.99 (standard deviation of 0.51). As shown in Figure 2, beaut scores in the SCUT-FBP5500 dataset turned out to have approximately normal distribution (skewness -0.12, kurtosis 2.9), supporting the threshold score of 2.75 to distinguish the lower quartile of aesthetic dissatisfaction.

The lower the score was, the more Gen-Z individuals in the simulation were dissatisfied with their beauty. Low beauty scores (below 2.75) indicated 100% simulated interest, while high beauty scores (greater than or equal to 2.75) indicated 0% simulated interest. After applying the threshold of a beauty score of 2.75 or below, there were a total of 2,460 images (44.7%) that showed simulated interest, while 3,040 images (55.3%) indicated no interest in cosmetic beauty. Simulation displayed a clear monotonic relationship between aesthetic dissatisfaction and cosmetic interest.

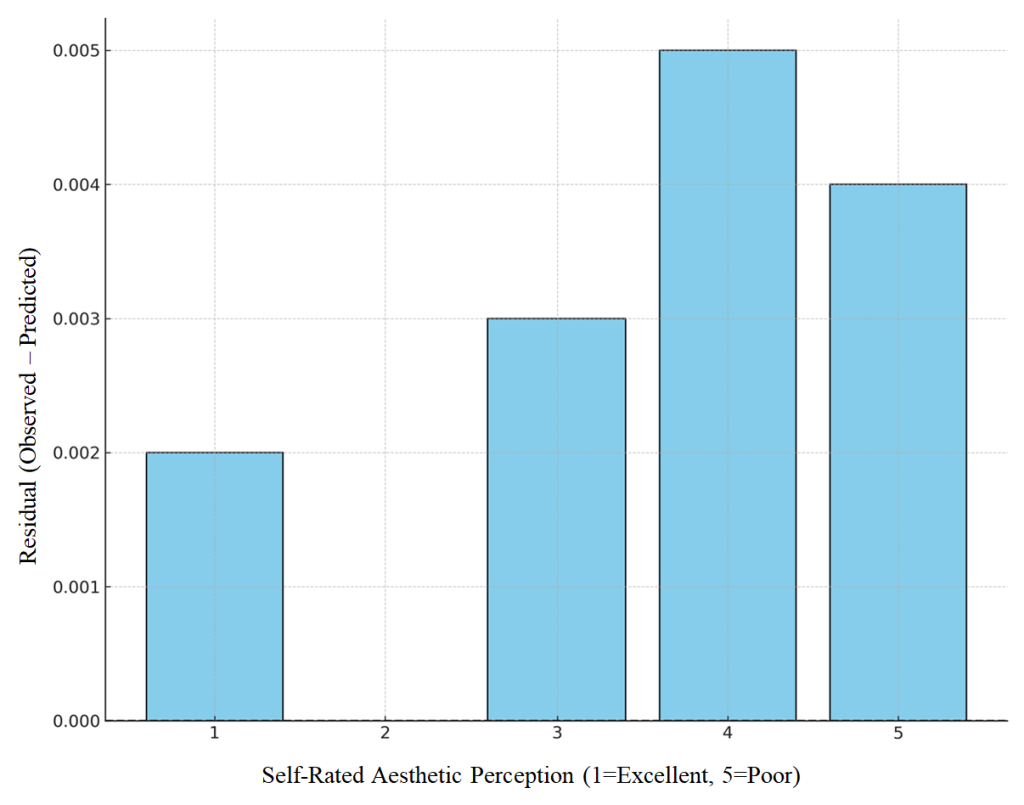

As for NHANES results, I included a total of 3,512 respondents in the age from 10 to 30 to represent Gen-Z individuals and used logistic regression analysis to find coefficients with as 1.08, p<0.001, and Pseudo as 0.146. The odd ratio was calculated to be around 2.94 that is interpreted as one unit increase in self-rated aesthetic dissatisfaction increased odds nearly threefold of reporting inaccessibility in dental care16. when comparing respondents reported their oral health as “poor” versus those who reported their oral health as “fair.” When compared with respondents reported as “excellent” for their oral health, it showed substantially higher for them to report unmet dental care needs. As for predicted probabilities of inaccessibility, 4.8% was shown at the score of 1 as excellent, 18.7% was shown at the score of 3 as good/fair, and 41.6% was calculated at the score of 5 as poor in Figure 3 below.

To evaluate the model fit, the residuals calculated between observed and predicted values across five-point aesthetic dissatisfaction scale were generated in Figure 4. As shown in Figure 4, the residuals remained small (standardized residual < 2), confirming the coherence of the regression model.

Even though SCUT and NHANES data were not directly merged, they complemented each other in the simulation. From SCUT simulation, it was found that poor beauty scores aligned well with higher cosmetic interest. From NHANES model, it was found that low self-perceived oral aesthetics was associated well with reported unmet dental care as a meaningful indicator of the interest in cosmetic dentistry. Therefore, the combination of SCUT modeled external appearance and NHANES modeled internal self-perception triangulated the link of the appearance dissatisfaction and the interest in cosmetic dentistry.

Discussion

From the findings in this study, several implications are made about whether aesthetic dissatisfaction is correlated with an increased level of cosmetic dentistry interest among Gen-Z individuals. With two publicly available datasets from SCUTFBP5500 for external aesthetic ratings and 2017-2018 NHANES for self-rated oral health and unmet dental care needs, a clear relationship was demonstrated; the lower the aesthetic dissatisfaction was, the more it was consistently related to reported interest in cosmetic dentistry. Through the simulation, both datasets were integrated in a way that SCUTFBP5500 provided facial beauty scores as an external view in a standardized scale from 1 (least attractive) to 5 (most attractive). Images with scores below 2.75 were relevant to the cases with potential cosmetic interest. With this threshold in the simulation, a perfect separation occurred in the classification, indicating how respondents with low aesthetic ratings were almost perfectly relevant to the “cosmetic interest” category. A strong directional relationship was shown in the simulation.

However, NHANES provided a real-world self-reported aesthetic dissatisfaction as a nationally representative sample. On a scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor) as an indicator of aesthetic dissatisfaction, self-rated oral health was specifically used, and self-reported dental care inaccessibility was used as an indicator for the interest in cosmetic dentistry. According to the logistic regression model with self-reported oral health, the odds of reporting dental needs that have not been met were almost tripled. Importantly, the latent model played a role in providing a conceptual connection between both datasets. Latent framework provided an important step in mapping SCUT and NHANES datasets that could not be individually merged onto a shared sense of dissatisfaction. Here, latent framework indicated a composite index of appearance dissatisfaction combining external (SCUT) and internal (NHANES) measures. Therefore, the probability model of cosmetic dentistry interest in this study suggests that a similar directional effect of aesthetic dissatisfaction was shown on cosmetic dentistry regardless of external or internal aesthetic dissatisfaction.

Even though SCUT did not directly measure Gen-Z, the external ratings indicated how lower beauty scores could be linked with cosmetic interest. This aligns well with the previous study by17, who found a significant connection between self-esteem among college students and self-perceived dental appearance and also by18, who reported how almost one-third of young adults showed an interest in aesthetic dental treatment from the social media influence. These findings also supported the previous study that found how poor dental aesthetics significantly influenced the quality of life in young adults19. In addition, they also supported the previous study that reported how adolescents with higher malocclusion severity had higher chance to experience negative physiological impact20‘21. Furthermore, they were consistent with the findings by the study that reviewed dental appearance and psychological well-being, reporting how there was a strong link between aesthetic concerns and self-esteem22‘23‘24‘25. Meanwhile, the findings from NHANES datasets suggest that aesthetic dissatisfaction is associated with reported care-seeking behaviors among young adults in the real world as people with poor self-reported oral health were statistically more likely to experience dental needs that have not been met before.

Overall, the findings in this study suggest important implications to dental practitioners. Understanding how aesthetical dissatisfaction drives an interest of people with cosmetic dentistry, dentists may use it as a guide to communicate with patients in terms of preventive care and realistic outcomes of it. Furthermore, the link between aesthetic dissatisfaction and unmet dental needs found in this study suggests that there exists a barrier for young adults to access cosmetic dental services. Supporting them with educational outreach or programs as a part of policy would help young adults meet dental needs in cases where their aesthetic dissatisfaction is poor.

Limitations

While the study provides an important insight on the relationship between poor aesthetic dissatisfaction and an increased level of interest in cosmetic dentistry, there are limitations. First, the findings in this study were based on simulated outcomes in SCUT, indicating that actual behavior was not considered, but an arbitrary threshold (beauty score below 2.75) was used for the classification of cosmetic interest. Moreover, the SCUT-FBP5500 dataset did not represent Gen-Z specifically since it included individuals across broader age groups and also with cultural backgrounds. In addition, aesthetic dissatisfaction may not be a sole reason for dental care inaccessibility, and cultural factors were disregarded as both beauty scores from SCUT and self-reported aesthetic dissatisfaction from NHANES may be influenced by cultural norms. Moreover, poor self-rated oral health may not indicate purely aesthetics but pain, function, or disease concerns. Similarly, unmet dental care needs may be from cost, access, or insurance barriers instead of cosmetic motivations. Additionally, NHANES relied on self-reported oral health assessments that were subject to bring bias and subjective interpretation instead of clinical verification26. Lastly, both datasets were not merged at individual level, even though the latent framework conceptually made it feasible to simulate the results in combination of them. Finally, the cutoff value of 2.75 was based on the distribution and not theory-driven. Therefore, it shall be cautiously interpreted as explanatory rather than a validated threshold. Furthermore, simpler descriptive statistics and correlation analyses may have addressed the research question even though logistic regression and latent modeling indicated a structured way to estimate associations. Future studies are recommended to consider these approaches with appropriate control variables with a more transparent baseline before applying complex modeling frameworks.

With these limitations, it is suggested for future studies to use direct cosmetic dentistry variables, such as surveys explicitly asking about cosmetic dentistry interest, to analyze more direct outcomes and reduce assumptions in interpretation. In addition, including additional indicators to the latent framework, such as data with social media engagement, history of orthodontic treatment, or more objective dental indices, will make the model more robust and predictive of real-world outcomes. In addition, including cultural and demographic aspects, including gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status as a part of aesthetic standards will help understand the relationship between aesthetic dissatisfaction and cosmetic dentistry more accurately in diverse Gen-Z populations. Unmeasured confounders, including sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and clinical oral health history may affect the observed associations between aesthetic dissatisfaction and the interest in cosmetic dentistry.

Conclusion

This study indicated lower aesthetic dissatisfaction was associated with higher predicted probabilities of having interest in cosmetic dentistry and unmet dental care among Gen-Z individuals in the United States. By introducing a composite latent aesthetic dissatisfaction framework, this study provided a conceptual bridge between the ratings of external appearance and self-reported oral health. However, limitations in this study included the use of simulated outcomes in SCUT, reliance on self-reported data in NHANES, and also an arbitrary threshold for classification. It is recommended that future studies focus on employing direct measures of the interest in cosmetic dentistry, while integrating datasets at the individual level and examining demographic and cultural factors of aesthetic dissatisfaction.

References

- M. Anderson, J. Jiang. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center (2018). [↩]

- E. A. Vogels. About one-in-five Americans use Twitter for news. Pew Research Center (2020). [↩]

- American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. The state of cosmetic dentistry 2021. AACD (2021). [↩]

- R. E. Goldstein. Esthetics in dentistry. BC Decker Inc. (2002). [↩]

- M. M. Pithon, J. M. M. Santos, C. S. D. Andrade. Impact of dental appearance on the self-esteem of adolescents. J. Orthod. Sci. 13, 5 (2024). [↩]

- M. M. Tin-Oo, N. Saddki, N. Hassan. Factors influencing patient satisfaction with dental appearance and treatments. BMC Oral Health 11, 6 (2011 [↩]

- J. Kenealy, H. Frude, A. Shaw. An evaluation of the psychosocial impact of malocclusion: a cross-sectional study of adolescents. Br. J. Orthod. 14, 137–143 (1987). [↩] [↩]

- M. M. Tin-Oo, N. Saddki, N. Hassan. Factors influencing patient satisfaction with dental appearance and treatments. BMC Oral Health 11, 6 (2011). [↩]

- S. Afroz, F. Rathi, A. Rajput, S. Rahman. Effect of dental esthetics on self-esteem in young adults. Eur. J. Dent. 7, 550–554 (2013). [↩]

- S. Alhammadi, M. Halboub, A. Al-Mashraqi. Perception of dental esthetics in adolescents and adults. Angle Orthod. 88, 667–673 (2018). [↩]

- A. Lenhart. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center (2015). [↩]

- L. Wang, Y. Li, Y. Zhao. Social media and aesthetic dental interest among youth. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 812394 (2024). [↩]

- G. Rosvall, P. Fields, W. Ziuchkovski. Attractiveness, acceptability, and value of orthodontic appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 135, 276.e1–276.e12 (2009). [↩]

- T. P. Morris, I. R. White, M. J. Crowther. Using simulation studies to evaluate statistical methods. Stat. Med. 38, 2074–2102 (2019). [↩]

- J. Brunner, M. A. McCarthy, S. A. Binning. Data simulation in ecological research and its benefits. Ecol. Evol. 8, 3066–3075 (2018). [↩]

- E. Sundareswaran, M. Pathak. Correlation between esthetic perception and demand for orthodontic treatment among young adults. J. Orthod. Sci. 10, 12 (2021). [↩] [↩]

- A. R. Zambrano, C. M. Huertas, L. M. Seoane. Self-perception and dental esthetics in university students. J. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 23, 112–119 (2024). [↩]

- H. Klages, M. Bruckner, A. Zentner. Dental esthetics, self-awareness, and oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Eur. J. Orthod. 26, 507–514 (2004). [↩]

- D. Marques, S. Ramos-Jorge, P. Paiva, F. Pordeus. Malocclusion: esthetic impact and quality of life among Brazilian adolescents. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 129, 424–429 (2006). [↩]

- C. Ferrando-Magraner, R. García-Sanz, C. Bellot-Arcis. The influence of dental esthetics on self-perceived oral health and satisfaction with life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3170 (2019). [↩]

- C. Newton, A. Prabhu, K. Robinson. The impact of dental appearance on self-esteem and psychological well-being: a systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 50, 101–110 (2022). [↩]

- A. Onyeaso, R. Sanu. Perceived impact of dental esthetics on self-esteem of Nigerian adolescents. Angle Orthod. 75, 101–106 (2005). [↩]

- S. Jung, Y. Ryu, J. Hwang. Influence of dental appearance on self-esteem among adolescents. Korean J. Orthod. 50, 123–132 (2020). [↩]

- C. Newton, A. Prabhu, K. Robinson. Dental appearance and psychosocial outcomes in adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 51, 201–212 (2023). [↩]

- F. Klages, K. Erbe, T. Sandberg. Perceived attractiveness, self-esteem, and oral health behavior in adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 9, 74 (2011). [↩]

- C. Locker, J. Jokovic, D. Clarke. Assessing the responsiveness of measures of oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 32, 10–18 (2004). [↩]