Abstract

Accumulating evidence has shown the importance of brain circuits in understanding cognitive and behavioral changes. For example, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) plays a crucial role in various cognitive functions, such as attention, decision-making, emotion regulation, and spatial and working memory. Dysfunction in mPFC circuits has been associated with psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and addiction. Recent rodent studies have demonstrated how different mPFC-related circuits contribute to these cognitive processes. This review highlights long-range circuits between the mPFC and other brain regions, such as the dorsomedial striatum (DMS), nucleus accumbens (NAc), thalamus, ventral hippocampus (vHPC), and basolateral amygdala (BLA). These pathways often function as reciprocal loops rather than simple one-way connections, allowing for more flexible control of behavior. For instance, the mPFC–DMS pathway is involved in attention and behavioral inhibition, while the mPFC–NAc and mPFC–BLA pathways relate more to motivation and emotion. This review summarizes the mPFC-related circuits and their cognitive functions, focusing on results from optogenetic, electrophysiological, and circuit-tracing approaches in rodent models. Given the increased focus on understanding the physiological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders, integrating different types of mPFC-related circuits may help inform new strategies to treat cognitive and emotional disorders. While these findings are primarily based on rodent studies and direct homology with humans is limited, they nonetheless provide valuable insights that may guide translational research and potential clinical interventions.

Introduction

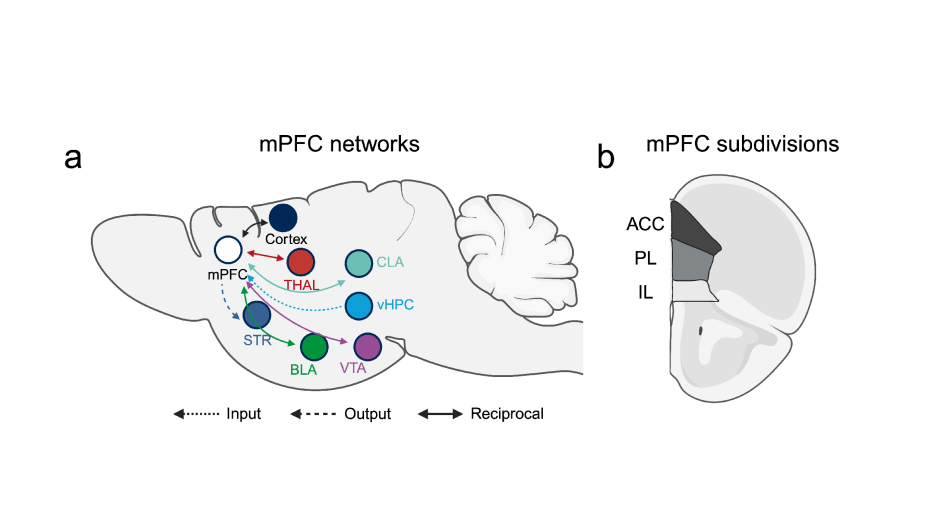

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a critical role in cognitive functions, including spatial and working memory, reward, decision-making, and emotion1,2. Growing evidence suggests that various neuropsychiatric disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), addiction, and anxiety disorders, have been associated with dysfunction of the PFC3,4. Understanding cortical circuits is important for uncovering the physiological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders5,6,7,8. Recent studies have examined the brain networks of the medial PFC (mPFC) by tracing its input and output neurons in rodent brains, which may give insight into understanding neural circuits5,6,7,8. Although comparing the PFC across species is a topic of debate9,10 the rodent mPFC shares many similarities with the human medial agranular cingulate cortex11.

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge species-specific differences. The organization of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) differs substantially between rodents and humans. Notably, Brodmann area 10 (frontopolar cortex), which supports abstract reasoning and long-term planning, is present in humans and primates but absent in rodents12. Thus, while rodent mPFC shares certain features with the human medial agranular cingulate cortex, direct homology is limited9. Clinically, hypoactivity of the mPFC and related prefrontal regions has been observed in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, highlighting its central role in mood regulation13. These translational differences emphasize the importance of cautious interpretation when extrapolating rodent findings to human psychiatric conditions.

It is crucial to consider how commonly studied rodent subregions relate to human prefrontal divisions. Current consensus emphasizes that these correspondences are functional rather than strict anatomical homologies9. For example, the rodent prelimbic cortex (PL) has been linked to executive control and decision-making functions similar to the human dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC)/dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC), whereas the infralimbic cortex (IL) is more often compared to the human ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) with emotion regulation and fear extinction9. Likewise, rodent ACC shares conflict monitoring and error-detection properties with human medial/dorsal ACC9. However, these parallels should be considered as functional analogies rather than one-to-one homologies9.

The rodent mPFC consists of several subdivisions, including the ACC, PL, and IL11 (Fig. 1b). These regions progressively shift their cognitive functions along the dorsoventral axis, transitioning from decision-making and attention to motivation and emotion11. Furthermore, each region has distinct inputs and outputs, indicating differences in connectivity that likely contribute to their specific roles in behavior11. Previous studies have revealed the presence of diverse projection neuronal populations within the mPFC, enabling communication with other brain regions such as the basolateral amygdala (BLA), thalamus, and striatum (Fig. 1a)11. These circuits are mostly a network of reciprocal loops, rather than solely relying on one-way connections14,15. This allows the mPFC to continually update neural activity and effectively coordinate diverse behaviors14,15.

mPFC-dorsomedial striatum (DMS)

The existence of a neural pathway connecting the prefrontal cortex (PFC) to the dorsomedial striatum (DMS) has been proposed as a mediator of cognitive control in behavior, encompassing proactive inhibitory control and attention16. Electrophysiological recordings of neuronal activity and local field potentials have provided further evidence for the functional coupling between the dorsal mPFC and DMS. These recordings have shown synchronized activity in both brain regions during delay periods when inhibitory control and attention are most crucial17,18. It has been proposed that mPFC projection neurons directly influence the activity of the DMS19. The glutamatergic input from mPFC terminals is believed to modulate the balance of activity between the direct and indirect pathways within the DMS20,21. This modulation may regulate the initiation and inhibition of actions, as well as the attentional state associated with upcoming behavior. A rodent study using selective chemogenetic and optogenetic approaches suggested corticostriatal neurons in inhibitory control. To be specific, when frontostriatal neurons were silenced, it led to deficits in inhibitory control, specifically manifested as an increase in premature responses. These frontostriatal neurons exhibited a predominance of persistent activation or silencing during inhibitory control, and altered timing of activity change in these neurons was associated with prematurely expressed responses in the task. Among the mPFC neuronal population, a higher proportion of frontostriatal projection neurons displayed task engagement with persistent changes in firing rate. Together, these results support the role of frontostriatal projection neurons in controlling behavioral inhibition22.

Studies have shown that corticostriatal inputs produce distinct synaptic responses in D1- versus D2- medium spiny neurons (MSNs)23 Moreover, whole-brain mapping indicates that D1- and D2-MSNs differentially receive input from cortical areas, including the mPFC24. D1-MSNs generally promote action initiation, while D2-MSNs support action suppression, and the balance between these pathways is crucial for cognitive flexibility25. Corticostriatal synapses display long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD), as well as metaplasticity and homeostatic plasticity, which are experience-dependent and can remodel decision-making strategies26. Dysregulation of these plasticity rules has been linked to vulnerability to addiction and other psychiatric conditions27.

mPFC-nucleus accumbens (NAc)

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a central role in executive control and supports goal-directed behaviors, such as planning and initiating actions to obtain reward-related outcomes, including drug use28. Different PFC subregions project to distinct parts of the nucleus accumbens (NAc); for instance, the infralimbic (IL) mPFC primarily targets the NAc shell, while the prelimbic (PL) mPFC projects to the NAc core29. Studies using pharmacological and optogenetic tools have revealed that these distinct projections show subregion-specific differences in synaptic plasticity and cocaine-related behavioral outcomes30,31.

Studies indicate that the glutamatergic pathway between the PFC and NAc undergoes plastic changes in rodent models of addiction and plays a key role in drug-seeking behavior after abstinence or extinction following prolonged cocaine exposure32,33,34. However, the effects within the mPFC vary depending on the subregion involved32,33,34. Activation of the PL-NAc projection is known to support reinstatement behavior after extinction, while inactivation of the IL-NAc circuit can also trigger reinstatement32,33,34. Comparable results have been reported in studies using forced withdrawal models under the cocaine incubation paradigm35. Although both the PL-NAc and IL-NAc circuits show similar neuroplasticity, optogenetic reversal of plasticity leads to opposite behavioral effects. Specifically, reversing IL–NAc plasticity increases the incubation of cocaine craving, whereas reversing PL–NAc plasticity reduces it23.

The involvement of glutamatergic regulation of the NAc in addiction is well-established, but the roles of specific inputs are complex and context-dependent. Results differ depending on the specific PFC region examined (PL, IL, or orbitofrontal), the paradigm and time point related to cocaine (reinstatement, resistance to punishment, seeking, or escalation), the stimulation parameters, and the species studied24,36.

Recent anatomical mapping further highlights a layer-specific distribution of mesolimbic projections from the mPFC. NAc-projecting neurons are enriched in upper layers (L2/3–5a) and display distinct molecular signatures, whereas deeper layers (L5b–6) preferentially contribute to projections toward other mesolimbic targets such as the VTA or BLA37,38. This laminar organization provides additional mechanistic insight into how cortico-striatal and cortico-amygdalar pathways selectively gate information flow.

mPFC-Thalamus

mPFC exerts control over actions driven by and directed toward desired outcomes through its connections with various thalamic nuclei39 and recurrent networks involving the basal ganglia and thalamus40. This circuitry has evolved in vertebrates and is associated with the neural systems underlying higher-level cognitive processes in humans41.

The afferent and efferent connections between the mPFC and multiple nuclei in the central thalamus are present throughout all regions of the mPFC42. These higher-order thalamic nuclei primarily receive input from the cortex and are structured to facilitate particular components of adaptive, goal-directed behavior42. The mediodorsal nucleus (MD) receives strong excitatory projections from layer 5 and modulatory projections from layer 6 of the mPFC43,44. Thalamic projections are focused on the middle layers of the mPFC, while sparser diffuse projections are observed in layer I43,44. These thalamocortical projections activate excitatory networks and feedforward inhibition in the mPFC43,44. Recent evidence suggests that the MD nucleus enhances cortical connectivity and regulates the signal-processing properties of mPFC neurons through specific subpopulations of thalamocortical neurons that compensate for uncertainty related to low signals or high levels of noise45,46.

Building on this, recent studies suggest that subpopulations of the mediodorsal (MD) thalamus may project selectively to different cortical layers of the mPFC. Inputs to superficial layers (L2/3) tend to engage recurrent excitatory networks, whereas inputs to deeper layers (L5) preferentially influence long-range output neurons, indicating layer-specific modes of thalamocortical communication11. This layer-specific targeting suggests that MD–mPFC communication does not simply amplify cortical signals, but dynamically shapes information processing depending on behavioral context11.

In summary, the mPFC is connected to several thalamic nuclei that contribute to different aspects of goal-directed behavior42. The MD provides focused input to the middle layers of the mPFC and is known to enhance and sustain activity in neurons involved in encoding action-outcome relationships43,44. This activity supports rapid learning, complex decision-making, and working memory43,44. In addition, the intralaminar nuclei send projections to both the basal ganglia and the cortex, helping regulate information flow in cortico-basal ganglia circuits45,46. Lesions in these regions have been shown to broadly affect functions that rely on the mPFC and striatum45,46.

ventral Hippocampus (vHPC)- mPFC

Hippocampal input to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) plays a role in providing contextual information, encoding memories, and regulating emotions47,48. Although the function in memory encoding and retrieval in HPC and mPFC has been well-established, it remains unclear which specific phases of memory functions (encoding, maintenance, and/or retrieval) require the interaction between the mPFC and the hippocampus47. Recent studies using projection-specific optogenetic silencing approach in rodents have supported the idea that the direct pathway from the hippocampus and subiculum to the mPFC is critically involved in regulating both cognitive and emotional aspects of memory47. Inhibiting the direct input from the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) to the mPFC impaired the encoding of location cues required for task performance, while maintenance and retrieval processes remained intact47. Moreover, the firing of goal-selective neurons in the mPFC was found to depend exclusively on the vHPC direct input during the encoding phase of each trial47. Additionally, the transmission of task-related information through the vHPC-mPFC projection may be supported by the synchronization of mPFC activity with gamma oscillations in the vHPC. Together, these findings suggest that direct input from the vHPC to the mPFC plays a critical role in encoding spatial cues during spatial working memory tasks47.

Consistent with these findings, recent work supports the idea that interactions between vHPC and mPFC circuits involve oscillatory synchronization. In rodents, hippocampal theta-mPFC coherence is correlated with successful spatial working memory performance49. Cross-frequency coupling, such as theta-gamma coupling between hippocampus and mPFC, further suggests a mechanism by which contextual information might be coordinated with executive control49. Dysregulation of such synchrony has been implicated in stress-related disorders, underscoring the dynamic rather than static nature of prefrontal circuits50.

The vHPC, mPFC, and basolateral amygdala (BLA) are also important regions in the regulation of anxiety-related behavior48. Among these, the projection from the vHPC to the mPFC has been implicated in processing aversive experiences48. To examine this further, one study combined multi-site neural recordings with optogenetic inhibition of vHPC terminals48. Inhibiting the input from the vHPC to the mPFC altered anxiety responses and disrupted the mPFC’s representation of aversive stimuli, along with reducing theta synchrony in a pathway-, frequency-, and task-specific manner48. Notably, bilateral inhibition of this projection induced physiological changes in the BLA associated with a state reminiscent of safety48. These results provide valuable insights into the distinct role of the vHPC-mPFC projection in anxiety-related behavior and the spatial representation of aversive information within the mPFC.

mPFC-Basolateral amygdala (BLA)

Fear extinction memory retrieval has been linked to increased neuronal activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)51. However, how these extinction-related changes in the mPFC influence the amygdala to reduce fear responses is not fully understood51. One study used ex vivo electrophysiology combined with optogenetics to explore this question51. The results showed that fear extinction reduced the strength of excitatory synaptic transmission from the mPFC to the basolateral amygdala (BLA), as measured by glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs), while inhibitory responses remained unchanged51. In contrast, the strength of mPFC input to intercalated neurons was unaffected by extinction51. The study also found that stimulating mPFC afferents caused heterosynaptic inhibition of auditory cortical inputs to the BLA51. Together, these findings suggest that fear extinction may weaken mPFC–BLA excitatory signaling, helping to reduce amygdala output, while maintaining the function of inhibitory intercalated neurons that regulate fear expression51.

The dysregulation of prefrontal control over the amygdala is implicated in the development of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. In a rodent anxiety model induced by chronic restraint stress (CRS), mPFC-BLA dysregulation has occurred. To be specific, the dysregulation primarily occurs in basolateral amygdala (BLA) projection neurons that receive one-way inputs from the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC→BLA PNs), rather than those with reciprocal connections to the dmPFC (dmPFC↔BLA PNs). Specifically, CRS leads to a shift in the excitatory-inhibitory balance driven by the dmPFC towards excitation in the dmPFC→BLA PNs, while the balance remains unaffected in the latter population. This specific dysregulation is associated with enhanced presynaptic glutamate release, which is primarily observed in the connections made by the dmPFC. Furthermore, this dysregulation is highly correlated with increased anxiety-like behavior in mice subjected to chronic stress52. Notably, low-frequency optogenetic stimulation of dmPFC inputs in the BLA effectively normalizes the enhanced glutamate release onto dmPFC→BLA PNs and leads to a lasting reduction in anxiety-like behavior induced by CRS. These findings highlight a target cell-specific dysregulation in the transmission from the mPFC to the amygdala in response to stress-induced anxiety52. A more recent study regarding the subcircuits established by the mPFC neurons in a rodent anxiety model induced by CRS showed that CRS has been found to have a significant impact on the synaptic transmission in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) layer V neurons that project to the BLA. Specifically, CRS results in a reduction of inhibitory synaptic transmission onto these BLA-projecting neurons, while excitatory synaptic transmission remains unaffected. This disruption in the balance between excitation and inhibition (E-I balance) leads to an overall increase in excitation. Additionally, CRS selectively increases the intrinsic excitability of the BLA-projecting neurons in dmPFC layer V53.

In addition to direct excitatory control, mPFC projections to the BLA can indirectly regulate fear expression by engaging intercalated cell (ITC) clusters, which mediate feedforward inhibition of BLA principal neurons51,54. Under chronic stress, this gating mechanism becomes disrupted, leading to excessive excitatory drive from mPFC to BLA and heightened anxiety-like behavior52. Together, these findings highlight the state-dependent modulation of amygdala output by mPFC–ITC interactions55.

Discussion

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) integrates a wide range of cognitive functions through complex and flexible neural circuits. The mPFC is primarily composed of excitatory pyramidal neurons ($\sim$80–90\%) and inhibitory GABAergic interneurons ($\sim$10–20\%), which together form the basis of its functional connectivity . These neurons create long-range projections to several brain regions, constructing dynamic circuits that allow the mPFC to update, coordinate, and modulate behavior based on both internal goals and external stimuli.

In addition to pyramidal neurons, the mPFC contains diverse subtypes of inhibitory interneurons, including parvalbumin-, somatostatin-, and vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing cells, which differentially shape local circuit dynamics and long-range communication56. Beyond classical glutamatergic and GABAergic mechanisms, modulatory systems further refine mPFC function. For instance, endocannabinoid signaling regulates prefrontal excitatory transmission and plasticity57. Likewise, cholinergic inputs tune prefrontal theta rhythms and attentional control, providing another layer of oscillatory modulation58. Together, these modulators highlight that mPFC circuits are not static entities but are dynamically regulated by diverse cellular and neurochemical influences.

Each mPFC-related circuit contributes differently to cognitive function. For instance, the mPFC–DMS circuit plays a role in attention and behavioral inhibition, the mPFC-NAc circuit is involved in reward-driven behavior and drug-seeking, and the vHPC-mPFC circuit enables spatial memory encoding and emotional regulation. Meanwhile, the mPFC-BLA and mPFC-thalamus circuits are essential for fear/anxiety modulation and working memory, respectively. Most of these circuits interact in reciprocal loops rather than functioning independently, allowing the mPFC to process cognitive functions with greater flexibility and context sensitivity.

Consistent with this, growing evidence has supported that the dysregulation of these circuits has been associated with psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorders, depression, and addiction. The mPFC is among the last cortical regions to mature, continuing into late adolescence. This protracted development renders it sensitive to neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD and schizophrenia59. With aging, mPFC-dependent working memory declines, partly due to reduced synaptic integrity60. However, the exact mechanisms remain inconclusive; excessive excitation, reduced inhibition, or altered synaptic plasticity could be the possible mechanisms for these diseases. Understanding these physiological pathways not only enhances our apprehension of normal cognitive processes but also reveals pathways for future therapeutic approaches.

In addition to neuronal mechanisms, non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes regulate glutamate uptake and release signaling molecules such as D-serine, thereby fine-tuning the excitatory/inhibitory balance within mPFC circuits61. Microglia contribute to synaptic pruning and plasticity, influencing circuit maturation and stress reactivity62.

To study these complex interactions, researchers increasingly rely on advanced circuit-mapping tools. While optogenetics provides millisecond precision in controlling defined cell types, it can artificially synchronize activity beyond physiological levels63. Chemogenetics offers cell-type selectivity but with slower temporal resolution64. Ex vivo electrophysiology provides mechanistic insight but cannot fully capture in vivo dynamics, whereas local field potentials (LFPs) reflect population synchrony without single-cell resolution65. Emerging techniques such as fast-scan cyclic voltammetry and fiber photometry enable sub-second measurement of neurotransmitter dynamics, although fiber photometry lacks single-cell resolution66,67. Complementary approaches like miniature microendoscopes (miniscopes) now enable longitudinal single-cell calcium imaging in freely moving animals, providing a more detailed view of circuit function68.

Further research should aim to map these circuits in more detail, especially using cell-type-specific tools and longitudinal studies in both healthy and disease models. Ultimately, connecting circuit-level findings to behavior provides a promising route for bridging neuroscience and mental health treatment. Such insights may also inform novel therapeutic strategies, including pharmacological interventions and non-invasive neuromodulation approaches (e.g., rTMS, tDCS) that target prefrontal circuits implicated in psychiatric disorders69.

Beyond rodent studies, emerging approaches such as postmortem human mPFC transcriptomic profiling70 (e.g., Allen Brain Atlas), primate and marmoset fMRI connectivity studies71, and intracranial electrophysiology72 provide critical complementary perspectives. Although this review mainly focuses on circuitry studies using rodents, acknowledging their contributions highlights the translational bridge between basic circuit findings and human psychiatric research. Nevertheless, it is important to note that rodent anxiety-like behaviors only partially model human depression and anxiety, and thus, translational interpretations should remain cautious.

Methods

A focused literature review was conducted to examine how the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) contributes to cognition and behavior in rodents. PubMed and Google Scholar were used to search for peer-reviewed, English-language articles published from 2000 onward. Search terms included “medial prefrontal cortex,” “mPFC and cognition,” “mPFC and decision-making,” “prefrontal cortex and emotion,” and “rodent prefrontal cortex circuits.” Studies were selected if they used rodent models, described mPFC connections to other brain regions, and investigated cognitive functions such as memory, attention, decision-making, or emotion. Experimental methods included optogenetics, chemogenetics, tract-tracing, and electrophysiology. For each study, information was collected on the species used, the mPFC subregion studied, the techniques applied, and the behavioral or physiological results. The review focused on circuits between the mPFC and the dorsomedial striatum (DMS), nucleus accumbens (NAc), thalamus, ventral hippocampus (vHPC), and basolateral amygdala (BLA). These circuits were grouped by functions to help summarize current understanding and identify areas for future research.

| Circuits | Species | Layers (if known) | Methods | Main behavioral effect | Representative references | Caveats/notes |

| mPFC → DMS | Mouse, Rat | L5 projection neurons | Optogenetics, Chemogenetics, Electrophysiology, Tracing | Attentional control, inhibitory control of premature responses | Christakou et al., 200173; Bissonette & Roesch, 201574; Terra et al., 202075. | Effects are task-dependent; PL vs IL subdivisions may differ |

| mPFC → NAc | Mouse, Rat | L2/3–5a (NAc-projecting neurons) | Optogenetics, Electrophysiology, Tracing | Drug-seeking reinstatement, incubation of cocaine craving, goal-directed behavior | Ma et al., 201476; Kalivas & McFarland, 200377; Babiczky & Matyas, 202278. | Subregion-specific effects (PL vs IL); circuit roles depend on drug paradigm |

| mPFC ↔ MD Thalamus | Mouse, Rat | Inputs to L2/3, outputs from L5–6 | Tracing, Electrophysiology | Working memory, action–outcome encoding, decision-making | Xiao et al., 200979; Collins et al., 201880; Anastasiades & Carter, 202181. | Subpopulations of MD neurons shape signals differently (uncertainty, noise) |

| vHPC → mPFC | Mouse, Rat | L2/3 recipient neurons | Optogenetics, Electrophysiology | Spatial working memory encoding, theta–gamma synchrony, anxiety regulation | Spellman et al., 201582; Padilla-Coreano et al., 201683; Tamura et al., 201784. | Theta/gamma synchrony is state- and task-dependent |

| mPFC → BLA | Mouse, Rat | L5 projection neurons | Optogenetics, Electrophysiology, Tracing | Fear extinction memory, stress-induced anxiety | Cho et al., 201385; Liu et al., 202086; Liu et al., 202387. | CRS alters E/I balance; subcircuit-specific plasticity |

| mPFC → Intercalated cells (ITC, amygdala) | Mouse | L5 projections via ITCs | Optogenetics | Fear gating, inhibitory control of BLA output | Strobel et al., 201588; Arruda-Carvalho & Clem, 201589. | Stress paradigms vary; ITC gating underexplored |

References

- Miller, E. K. and J. D. Cohen, , An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function., Annual Review of Neuroscience., 24, 167–202., (2001). [↩]

- Robbins, T. W. and A. F. T. Arnsten, , The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation., Annual Review of Neuroscience., 32, 267–287., (2009). [↩]

- Brendan D. Hare, B. D. Hare, Ronald S. Duman, and R. S. Duman, , Prefrontal cortex circuits in depression and anxiety: contribution of discrete neuronal populations and target regions., Molecular Psychiatry., 25, 2742–2758., (2020). [↩]

- Arnsten, A. F. T. and K. Rubia. Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51, 356–367. (2012). [↩]

- Ährlund-Richter, S., Y. Xuan, J. A. van Lunteren, H. Kim, C. Ortiz, I. Pollak Dorocic, K. Meletis, and M. Carlén, , A whole-brain atlas of monosynaptic input targeting four different cell types in the medial prefrontal cortex of the mouse., Nature Neuroscience., 22, 657–668., (2019). [↩] [↩]

- Sun, Q., X. Li, M. Ren, M. Zhao, Q. Zhong, Y. Ren, P. Luo, H. Ni, X. Zhang, C. Zhang, J. Yuan, A. Li, M. Luo, H. Gong, and Q. Luo, , A whole-brain map of long-range inputs to gabaergic interneurons in the mouse medial prefrontal cortex., Nature Neuroscience., 22, 1357–1370., (2019). [↩] [↩]

- Zhang, S., M. Xu, W.-C. Chang, C. Ma, J. P. Hoang Do, D. Jeong, T. Lei, J. L. Fan, and Y. Dan, , Organization of long-range inputs and outputs of frontal cortex for top-down control., Nature Neuroscience., 19, 1733–1742., (2016). [↩] [↩]

- Zingg, B., H. Hintiryan, L. Gou, M. Y. Song, M. Bay, M. S. Bienkowski, N. N. Foster, S. Yamashita, I. Bowman, A. W. Toga, and H.-W. Dong, , Neural networks of the mouse neocortex., Cell., 156, 1096–1111., (2014). [↩] [↩]

- Laubach, M., L. M. Amarante, K. Swanson, and S. R. White, , What, if anything, is rodent prefrontal cortex?, eNeuro., 5, ENEURO.0315-18.2018., (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Carlén, M., , What constitutes the prefrontal cortex?, Science (New York, N.Y.)., 358, 478–482., (2017). [↩]

- Anastasiades, P. G. and A. G. Carter, , Circuit organization of the rodent medial prefrontal cortex., Trends in Neurosciences., 44, 550–563., (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- José Fernando de Oliveira, Jose Francis-Oliveira, Owen Leitzel, Owen Leitzel, Minae Niwa, and Minae Niwa, , Are the anterior and mid-cingulate cortices distinct in rodents?, Frontiers in Neuroanatomy., 16, (2022). [↩]

- Hai-Yang Wang, Hui-Li You, Chun-Li Song, Lu Zhou, Shi-Yao Wang, Xue-Lin Li, Zhan-Hua Liang, and Bing-Wei Zhang, , Shared and distinct prefrontal cortex alterations of implicit emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: an fnirs investigation., Journal of Affective Disorders., (2024). [↩]

- Wang, X. J., , Synaptic reverberation underlying mnemonic persistent activity., Trends in Neurosciences., 24, 455–463., (2001). [↩] [↩]

- Fuster, J. M., , The prefrontal cortex–an update: time is of the essence., Neuron., 30, 319–333., (2001). [↩] [↩]

- Christakou, A., T. W. Robbins, and B. J. Everitt, , Functional disconnection of a prefrontal cortical-dorsal striatal system disrupts choice reaction time performance: implications for attentional function., Behavioral Neuroscience., 115, 812–825., (2001). [↩]

- Bissonette, G. B. and M. R. Roesch, , Neural correlates of rules and conflict in medial prefrontal cortex during decision and feedback epochs., Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience., 9, 266., (2015). [↩]

- Emmons, E. B., B. J. De Corte, Y. Kim, K. L. Parker, M. S. Matell, and N. S. Narayanan, , Rodent medial frontal control of temporal processing in the dorsomedial striatum., The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience., 37, 8718–8733., (2017). [↩]

- Alexander, W. H. and J. W. Brown, , Medial prefrontal cortex as an action-outcome predictor., Nature Neuroscience., 14, 1338–1344., (2011). [↩]

- Wei, W., J. E. Rubin, and X.-J. Wang, , Role of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia in perceptual decision making., The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience., 35, 4052–4064., (2015). [↩]

- Ardid, S., J. S. Sherfey, M. M. McCarthy, J. Hass, B. R. Pittman-Polletta, and Nancy Kopell, , Biased competition in the absence of input bias revealed through corticostriatal computation., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America., 116, 8564–8569., (2019). [↩]

- Terra, H., B. Bruinsma, S. F. de Kloet, M. van der Roest, T. Pattij, and H. D. Mansvelder, , Prefrontal cortical projection neurons targeting dorsomedial striatum control behavioral inhibition., Current biology: CB., 30, 4188-4200.e5., (2020). [↩]

- Edén Flores-Barrera, E. Flores-Barrera, Bianca J. Vizcarra-Chacón, B. J. Vizcarra-Chacón, Dagoberto Tapia, D. Tapia, José Bargas, J. Bargas, Elvira Galarraga, and E. Galarraga. Different corticostriatal integration in spiny projection neurons from direct and indirect pathways. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 4, 15–15. (2010). [↩] [↩]

- Jiayi Lu, J. Lu, Yidong Cheng, Y. Cheng, Xueyi Xie, X. Xie, Kayla Woodson, K. Woodson, Jordan Bonifacio, J. Bonifacio, Emily Disney, E. Disney, Britton R. Barbee, B. Barbee, Xuehua Wang, X. Wang, Mariam Zaidi, M. Zaidi, Jun Wang, and J. Wang, , Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to dopamine d1 and d2 receptor-expressing medium spiny neurons in the posterior dorsomedial striatum., eNeuro., 8, (2020). [↩] [↩]

- Jyotika Bahuguna, J. Bahuguna, Philipp Weidel, P. Weidel, Abigail Morrison, A. Morrison, and Abigail Morrison, , Exploring the role of striatal d1 and d2 medium spiny neurons in action selection using a virtual robotic framework., European Journal of Neuroscience., 49, 737–753., (2019). [↩]

- David M. Lovinger and D. M. Lovinger, , Neurotransmitter roles in synaptic modulation, plasticity and learning in the dorsal striatum., Neuropharmacology., 58, 951–961., (2010). [↩]

- Lawrence G Appelbaum, Lawrence G. Appelbaum, Mohammad Ali Shenasa, Mohammad Ali Shenasa, Louise Stolz, Louise A. Stolz, Zafiris Daskalakis, and Zafiris J. Daskalakis, , Synaptic plasticity and mental health: methods, challenges and opportunities., Neuropsychopharmacology., (2022). [↩]

- Kalivas, P. W., N. Volkow, and J. Seamans, , Unmanageable motivation in addiction: a pathology in prefrontal-accumbens glutamate transmission., Neuron., 45, 647–650., (2005). [↩]

- Sesack, S. R. and A. A. Grace, , Cortico-basal ganglia reward network: microcircuitry., Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology., 35, 27–47., (2010). [↩]

- Ma, Y.-Y., B. R. Lee, X. Wang, C. Guo, L. Liu, R. Cui, Y. Lan, J. J. Balcita-Pedicino, M. E. Wolf, S. R. Sesack, Y. Shaham, O. M. Schlüter, Y. H. Huang, and Y. Dong, , Bidirectional modulation of incubation of cocaine craving by silent synapse-based remodeling of prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections., Neuron., 83, 1453–1467., (2014). [↩]

- Scofield, M. D., J. A. Heinsbroek, C. D. Gipson, Y. M. Kupchik, S. Spencer, A. C. W. Smith, D. Roberts-Wolfe, and P. W. Kalivas, , The nucleus accumbens: mechanisms of addiction across drug classes reflect the importance of glutamate homeostasis., Pharmacological Reviews., 68, 816–871., (2016). [↩]

- Kalivas, P. W. and K. McFarland, , Brain circuitry and the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior., Psychopharmacology., 168, 44–56., (2003). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Kalivas, P. W., , The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction., Nature Reviews. Neuroscience., 10, 561–572., (2009). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- McGlinchey, E. M., M. H. James, S. V. Mahler, C. Pantazis, and G. Aston-Jones, , Prelimbic to accumbens core pathway is recruited in a dopamine-dependent manner to drive cued reinstatement of cocaine seeking., The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience., 36, 8700–8711., (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Wolf, M. E., , Synaptic mechanisms underlying persistent cocaine craving., Nature Reviews. Neuroscience., 17, 351–365., (2016). [↩]

- Moorman, D. E., M. H. James, E. M. McGlinchey, and G. Aston-Jones, , Differential roles of medial prefrontal subregions in the regulation of drug seeking., Brain Research., 1628, 130–146., (2015). [↩]

- Babiczky, Á. and F. Matyas, , Molecular characteristics and laminar distribution of prefrontal neurons projecting to the mesolimbic system., eLife., 11, e78813., (2022). [↩]

- Liu, W.-Z., C.-Y. Wang, Y. Wang, M.-T. Cai, W.-X. Zhong, T. Liu, Z.-H. Wang, H.-Q. Pan, W.-H. Zhang, and B.-X. Pan, , Circuit- and laminar-specific regulation of medial prefrontal neurons by chronic stress., Cell & Bioscience., 13, 90., (2023). [↩]

- Mair, R. G., M. J. Francoeur, and B. M. Gibson, , Central thalamic-medial prefrontal control of adaptive responding in the rat: many players in the chamber., Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience., 15, 642204., (2021). [↩]

- Foster, N. N., J. Barry, L. Korobkova, L. Garcia, L. Gao, M. Becerra, Y. Sherafat, B. Peng, X. Li, J.-H. Choi, L. Gou, B. Zingg, S. Azam, D. Lo, N. Khanjani, B. Zhang, J. Stanis, I. Bowman, K. Cotter, C. Cao, S. Yamashita, A. Tugangui, A. Li, T. Jiang, X. Jia, Z. Feng, S. Aquino, H.-S. Mun, M. Zhu, A. Santarelli, N. L. Benavidez, M. Song, G. Dan, M. Fayzullina, S. Ustrell, T. Boesen, D. L. Johnson, H. Xu, M. S. Bienkowski, X. W. Yang, H. Gong, M. S. Levine, I. Wickersham, Q. Luo, J. D. Hahn, B. K. Lim, L. I. Zhang, C. Cepeda, H. Hintiryan, and H.-W. Dong, , The mouse cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic network., Nature., 598, 188–194., (2021). [↩]

- Koechlin, E., , An esvolutionary computational theory of prefrontal executive function in decision-making., Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences., 369, 20130474., (2014). [↩]

- Sherman, S. M. Thalamus plays a central role in ongoing cortical functioning. Nature Neuroscience 19, 533–541. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Xiao, D., B. Zikopoulos, and H. Barbas. Laminar and modular organization of prefrontal projections to multiple thalamic nuclei. Neuroscience 161, 1067–1081. (2009). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Collins, D. P., P. G. Anastasiades, J. J. Marlin, and A. G. Carter. Reciprocal circuits linking the prefrontal cortex with dorsal and ventral thalamic nuclei. Neuron 98, 366–379.e4. (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Schmitt, L. I., R. D. Wimmer, M. Nakajima, M. Happ, S. Mofakham, and M. M. Halassa. Thalamic amplification of cortical connectivity sustains attentional control. Nature 545, 219–223. (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Mukherjee, A., N. H. Lam, R. D. Wimmer, and M. M. Halassa. Thalamic circuits for independent control of prefrontal signal and noise. Nature 600, 100–104. (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Spellman, T., M. Rigotti, S. E. Ahmari, S. Fusi, J. A. Gogos, and J. A. Gordon, , Hippocampal–prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory., Nature., 522, 309–314., (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Padilla-Coreano, N., S. S. Bolkan, G. M. Pierce, D. R. Blackman, W. D. Hardin, A. L. Garcia-Garcia, T. J. Spellman, and J. A. Gordon. Direct ventral hippocampal-prefrontal input is required for anxiety-related neural activity and behavior. Neuron 89, 857–866. (2016). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Makoto Tamura, M. Tamura, Timothy Spellman, T. Spellman, Andrew M. Rosen, A. M. Rosen, Andrew M. Rosen, Joseph A. Gogos, J. A. Gogos, Joshua A. Gordon, and J. A. Gordon, , Hippocampal-prefrontal theta-gamma coupling during performance of a spatial working memory task., Nature Communications., 8, 2182–2182., (2017). [↩] [↩]

- Nancy Padilla-Coreano, Nancy Padilla-Coreano, N. Padilla-Coreano, Sarah Canetta, S. Canetta, Rachel Mikofsky, R. Mikofsky, Emily Alway, Emily Alway, E. Alway, Emily Alway, Johannes Passecker, J. Passecker, Maxym Myroshnychenko, M. Myroshnychenko, Álvaro L. Garcia-Garcia, A. L. Garcia-Garcia, Alvaro L. Garcia-Garcia, Richard Warren, Richard Warren, R. A. Warren, Richard Warren, Eric Teboul, E. Teboul, Dakota R. Blackman, D. R. Blackman, Dakota R. Blackman, Mitchell P. Morton, Mitchell P. Morton, M. P. Morton, Mitchell P. Morton, Sofiya Hupalo, S. Hupalo, Kay M. Tye, K. M. Tye, Christoph Kellendonk, C. Kellendonk, David A. Kupferschmidt, D. A. Kupferschmidt, Joshua A. Gordon, and J. A. Gordon, , Hippocampal-prefrontal theta transmission regulates avoidance behavior., Neuron., 104, 601., (2019). [↩]

- Cho, J.-H., K. Deisseroth, and V. Y. Bolshakov, , Synaptic encoding of fear extinction in mpfc-amygdala circuits., Neuron., 80, 1491–1507., (2013). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Liu, W.-Z., W.-H. Zhang, Z.-H. Zheng, J.-X. Zou, X.-X. Liu, S.-H. Huang, W.-J. You, Y. He, J.-Y. Zhang, X.-D. Wang, and B.-X. Pan, , Identification of a prefrontal cortex-to-amygdala pathway for chronic stress-induced anxiety., Nature Communications., 11, 2221., (2020). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Liu, W.-Z., C.-Y. Wang, Y. Wang, M.-T. Cai, W.-X. Zhong, T. Liu, Z.-H. Wang, H.-Q. Pan, W.-H. Zhang, and B.-X. Pan, , Circuit- and laminar-specific regulation of medial prefrontal neurons by chronic stress., Cell \& Bioscience., 13, 90., (2023). [↩]

- Cornelia Strobel, C. Strobel, Roger Marek, R. Marek, Helen Gooch, H. Gooch, Rodney N. Sullivan, R. K. P. Sullivan, Pankaj Sah, and P. Sah, , Prefrontal and auditory input to intercalated neurons of the amygdala., Cell Reports., 10, 1435–1442., (2015). [↩]

- Maithé Arruda-Carvalho, M. Arruda-Carvalho, Roger L. Clem, and R. L. Clem, , Prefrontal-amygdala fear networks come into focus., Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience., 9, 145–145., (2015). [↩]

- Tremblay, R., S. Lee, and B. Rudy, , GABAergic interneurons in the neocortex: from cellular properties to circuits., Neuron., 91, 260–292., (2016). [↩]

- Lafourcade, M., I. Elezgarai, S. Mato, Y. Bakiri, P. Grandes, and O. J. Manzoni, , Molecular components and functions of the endocannabinoid system in mouse prefrontal cortex., PLOS ONE., 2, e709., (2007). [↩]

- Hasselmo, M. E. and M. Sarter, , Modes and models of forebrain cholinergic neuromodulation of cognition., Neuropsychopharmacology., 36, 52–73., (2011). [↩]

- B. J. Casey, B J Casey, Sarah J. Getz, Sarah Getz, Adriana Galván, and Adriana Galvan, , The adolescent brain., Developmental Review. [↩]

- John H. Morrison, J. H. Morrison, Mark G. Baxter, and M. G. Baxter, , The ageing cortical synapse: hallmarks and implications for cognitive decline., Nature Reviews Neuroscience., 13, 240–250., (2012). [↩]

- Thomas Papouin, T. Papouin, Jaclyn M. Dunphy, J. M. Dunphy, Jaclyn M. Dunphy, Michaela Tolman, M. Tolman, Kelly T. Dineley, K. T. Dineley, Philip G. Haydon, and P. G. Haydon, , Septal cholinergic neuromodulation tunes the astrocyte-dependent gating of hippocampal nmda receptors to wakefulness., Neuron., 94, 840–854., (2017). [↩]

- Hammond, T. R., D. Robinton, and B. Stevens, , Microglia and the brain: complementary partners in development and disease., Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology., 34, 523–544., (2018). [↩]

- Aleksey Malyshev, A. Malyshev, Roman Goz, R. Goz, Joseph J. LoTurco, J. J. LoTurco, Maxim Volgushev, and M. Volgushev, , Advantages and limitations of the use of optogenetic approach in studying fast-scale spike encoding., PLOS ONE., 10, 0122286., (2015). [↩]

- Mineki Oguchi, Mineki Oguchi, Masamichi Sakagami, and Masamichi Sakagami, , Dissecting the prefrontal network with pathway-selective manipulation in the macaque brain—a review., Frontiers in Neuroscience., 16, (2022). [↩]

- Óscar Herreras and O. Herreras, , Local field potentials: myths and misunderstandings., Frontiers in Neural Circuits., 10, 101–101., (2016). [↩]

- Suelen Lúcio Boschen, S. L. Boschen, James K. Trevathan, J. K. Trevathan, Seth A. Hara, S. A. Hara, Anders Asp, A. J. Asp, J. Luis Luján, and J. L. Lujan, , Defining a path toward the use of fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in human studies., Frontiers in Neuroscience., 15, (2021). [↩]

- Guohong Cui, G. Cui, Guohong Cui, Sang Beom Jun, S. B. Jun, Xin Jin, X. Jin, Michael Pham, M. D. Pham, Steven S. Vogel, S. S. Vogel, David M. Lovinger, D. M. Lovinger, Rui M. Costa, and R. M. Costa, , Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation., Nature., 494, 238–242., (2013). [↩]

- Kunal Ghosh, K. Ghosh, K. K. Ghosh, Laurie D. Burns, L. D. Burns, Eric D. Cocker, E. D. Cocker, Axel Nimmerjahn, A. Nimmerjahn, Yaniv Ziv, Y. Ziv, Abbas El Gamal, A. E. Gamal, Mark J. Schnitzer, and M. J. Schnitzer, , Miniaturized integration of a fluorescence microscope., Nature Methods., 8, 871–878., (2011). [↩]

- Bikson, M., A. R. Brunoni, L. E. Charvet, V. P. Clark, L. G. Cohen, Z.-D. Deng, J. Dmochowski, D. J. Edwards, F. Frohlich, E. S. Kappenman, K. O. Lim, C. Loo, A. Mantovani, D. P. McMullen, L. C. Parra, M. Pearson, J. D. Richardson, J. M. Rumsey, P. Sehatpour, D. Sommers, G. Unal, E. M. Wassermann, A. J. Woods, and S. H. Lisanby, , Rigor and reproducibility in research with transcranial electrical stimulation: an nimh-sponsored workshop., Brain stimulation., 11, 465–480., (2018). [↩]

- Hawrylycz, M. J., E. S. Lein, A. L. Guillozet-Bongaarts, E. H. Shen, L. Ng, J. A. Miller, L. N. van de Lagemaat, K. A. Smith, A. Ebbert, Z. L. Riley, C. Abajian, C. F. Beckmann, A. Bernard, D. Bertagnolli, A. F. Boe, P. M. Cartagena, M. M. Chakravarty, M. Chapin, J. Chong, R. A. Dalley, B. David Daly, C. Dang, S. Datta, N. Dee, T. A. Dolbeare, V. Faber, D. Feng, D. R. Fowler, J. Goldy, B. W. Gregor, Z. Haradon, D. R. Haynor, J. G. Hohmann, S. Horvath, R. E. Howard, A. Jeromin, J. M. Jochim, M. Kinnunen, C. Lau, E. T. Lazarz, C. Lee, T. A. Lemon, L. Li, Y. Li, J. A. Morris, C. C. Overly, P. D. Parker, S. E. Parry, M. Reding, J. J. Royall, J. Schulkin, P. A. Sequeira, C. R. Slaughterbeck, S. C. Smith, A. J. Sodt, S. M. Sunkin, B. E. Swanson, M. P. Vawter, D. Williams, P. Wohnoutka, H. R. Zielke, D. H. Geschwind, P. R. Hof, S. M. Smith, C. Koch, S. G. N. Grant, and A. R. Jones, , An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome., Nature., 489, 391–399., (2012). [↩]

- Hori, Y., D. J. Schaeffer, K. M. Gilbert, L. K. Hayrynen, J. C. Cléry, J. S. Gati, R. S. Menon, and S. Everling, , Comparison of resting-state functional connectivity in marmosets with tracer-based cellular connectivity., NeuroImage., 204, 116241., (2020). [↩]

- Mukamel, R. and I. Fried, , Human intracranial recordings and cognitive neuroscience., Annual Review of Psychology., 63, 511–537., (2012). [↩]

- Christakou, A., T. W. Robbins, and B. J. Everitt, , Functional disconnection of a prefrontal cortical-dorsal striatal system disrupts choice reaction time performance: implications for attentional function., Behavioral Neuroscience., 115, 812–825., (2001). [↩]

- Bissonette, G. B. and M. R. Roesch, , Neural correlates of rules and conflict in medial prefrontal cortex during decision and feedback epochs., Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience., 9, 266., (2015). [↩]

- Terra, H., B. Bruinsma, S. F. de Kloet, M. van der Roest, T. Pattij, and H. D. Mansvelder, , Prefrontal cortical projection neurons targeting dorsomedial striatum control behavioral inhibition., Current biology: CB., 30, 4188-4200.e5., (2020). [↩]

- Ma, Y.-Y., B. R. Lee, X. Wang, C. Guo, L. Liu, R. Cui, Y. Lan, J. J. Balcita-Pedicino, M. E. Wolf, S. R. Sesack, Y. Shaham, O. M. Schlüter, Y. H. Huang, and Y. Dong, , Bidirectional modulation of incubation of cocaine craving by silent synapse-based remodeling of prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections., Neuron., 83, 1453–1467., (2014). [↩]

- Kalivas, P. W. and K. McFarland, , Brain circuitry and the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior., Psychopharmacology., 168, 44–56., (2003). [↩]

- Babiczky, Á. and F. Matyas, , Molecular characteristics and laminar distribution of prefrontal neurons projecting to the mesolimbic system., eLife., 11, e78813., (2022). [↩]

- Xiao, D., B. Zikopoulos, and H. Barbas, , Laminar and modular organization of prefrontal projections to multiple thalamic nuclei., Neuroscience., 161, 1067–1081., (2009). [↩]

- Collins, D. P., P. G. Anastasiades, J. J. Marlin, and A. G. Carter, , Reciprocal circuits linking the prefrontal cortex with dorsal and ventral thalamic nuclei., Neuron., 98, 366-379.e4., (2018). [↩]

- Anastasiades, P. G. and A. G. Carter, , Circuit organization of the rodent medial prefrontal cortex., Trends in Neurosciences., 44, 550–563., (2021). [↩]

- Spellman, T., M. Rigotti, S. E. Ahmari, S. Fusi, J. A. Gogos, and J. A. Gordon, , Hippocampal–prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory., Nature., 522, 309–314., (2015). [↩]

- Padilla-Coreano, N., S. S. Bolkan, G. M. Pierce, D. R. Blackman, W. D. Hardin, A. L. Garcia-Garcia, T. J. Spellman, and J. A. Gordon, , Direct ventral hippocampal-prefrontal input is required for anxiety-related neural activity and behavior., Neuron., 89, 857–866., (2016). [↩]

- Makoto Tamura, M. Tamura, Timothy Spellman, T. Spellman, Andrew M. Rosen, A. M. Rosen, Andrew M. Rosen, Joseph A. Gogos, J. A. Gogos, Joshua A. Gordon, and J. A. Gordon, , Hippocampal-prefrontal theta-gamma coupling during performance of a spatial working memory task., Nature Communications., 8, 2182–2182., (2017). [↩]

- Cho, J.-H., K. Deisseroth, and V. Y. Bolshakov, , Synaptic encoding of fear extinction in mpfc-amygdala circuits., Neuron., 80, 1491–1507., (2013). [↩]

- Liu, W.-Z., W.-H. Zhang, Z.-H. Zheng, J.-X. Zou, X.-X. Liu, S.-H. Huang, W.-J. You, Y. He, J.-Y. Zhang, X.-D. Wang, and B.-X. Pan, , Identification of a prefrontal cortex-to-amygdala pathway for chronic stress-induced anxiety., Nature Communications., 11, 2221., (2020). [↩]

- Liu, W.-Z., C.-Y. Wang, Y. Wang, M.-T. Cai, W.-X. Zhong, T. Liu, Z.-H. Wang, H.-Q. Pan, W.-H. Zhang, and B.-X. Pan, , Circuit- and laminar-specific regulation of medial prefrontal neurons by chronic stress., Cell & Bioscience., 13, 90., (2023). [↩]

- Cornelia Strobel, C. Strobel, Roger Marek, R. Marek, Helen Gooch, H. Gooch, Rodney N. Sullivan, R. K. P. Sullivan, Pankaj Sah, and P. Sah, , Prefrontal and auditory input to intercalated neurons of the amygdala., Cell Reports., 10, 1435–1442., (2015). [↩]

- Maithé Arruda-Carvalho, M. Arruda-Carvalho, Roger L. Clem, and R. L. Clem, , Prefrontal-amygdala fear networks come into focus., Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience., 9, 145–145., (2015). [↩]