Abstract

Anxiety-like behavior in rodents has been used as a translational model for human anxiety disorders. Unconditioned behavioral tests, which depend on the natural conflict between exploratory drive and aversive behavior to open spaces, are widely employed measurements to assess anxiety-like behavior in rodents. This review focuses on strengths and limitations of different anxiety-like behavioral tests: the open field test (OFT), light-dark box test (LDBT), elevated plus maze test (EPMT), and elevated zero maze test (EZMT). These behavioral assays measure avoidance behaviors of rodents in anxiogenic environments using a simple but ethologically relevant approach. However, they provide challenges in interpretation, given sensitivity to external variables and inconsistencies across pharmacological models. In addition to behavioral paradigms, physiological measures such as corticosterone levels, stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH), heart rate variability (HRV), and infrared thermography provide complementary insight into the biological stress response with increased objectivity. These measurements, however, have similar limitations, including variability in sampling and interpretation. Taken together, this review emphasizes the importance of combining behavioral and physiological assays to enhance construct validity and obtain a more comprehensive assessment of anxiety-like behavior in rodents. A multidimensional approach may improve reproducibility and support more accurate modeling of human anxiety in preclinical research.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common psychiatric diseases in the world characterized by excessive fear and concern, accompanied by behavioral disturbances, even without actual external threats defined by the DSM-V1. Since rodent models provide valuable insights into behavioral, cognitive, motor, and psychiatric areas, these models have been widely used in translational research to investigate the underlying mechanisms and potential treatments for these disorders. These models have contributed significantly to the development of anxiolytic treatments2‘3‘4.

In rodents, anxiety-like behavior has been conceptualized as a generalized psychological and physiological response to uncertain or threatening stimuli5. Experimental paradigms to study such responses are typically divided into two categories: conditioned and unconditioned tests6. Conditioned tests require learning of an association between a neutral stimulus and an aversive event, such as a fear conditioning test, thus depending on intact memory and sensory processing6. In contrast, unconditioned tests exploit spontaneous, evolutionarily conserved behaviors, such as the tendency to avoid open, illuminated areas6. These tests, including the open field test (OFT), elevated plus maze test (EPMT), and light-dark box test (LDBT), are favored for their simplicity and strong ethological relevance, although they are also criticized regarding interpretability and external validity6.

In addition to behavioral assays, physiological measures such as corticosterone levels, stress-induced hyperthermia, and autonomic readouts provide complementary perspectives7‘8. Given these markers reflect internal states associated with stress and arousal, they could provide additional evidence when behavioral data alone are inconclusive or ambiguous9. However, physiological measures also have their limitations, such as sampling challenges and variability due to environmental or individual factors9.

Given the multifaceted nature of anxiety, a growing body of evidence highlights the importance of integrated approaches that combine both behavioral and physiological assessments9. This review will examine widely used unconditioned behavioral tests in rodents, discuss their respective advantages and limitations in evaluating anxiety-like behavior, and provide an overview of complementary physiological measures.

Behavioral Assays for Anxiety in Rodents

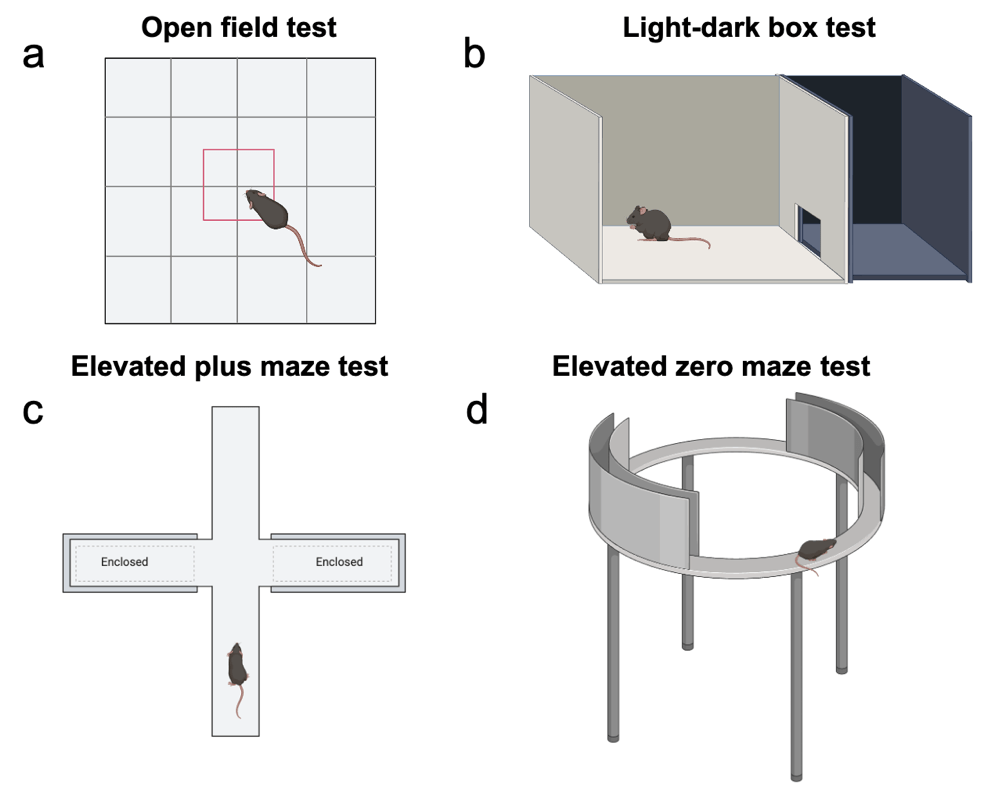

Open Field Test (OFT)

The open field test (OFT) is one of the most widely used behavioral paradigms for assessing different aspects in rodents, including innate behavior, locomotion, and anxiety-like behavior10. It is relatively simple to perform and requires only minimal equipment11. In this assay, individual experimental animals are placed in the center of an enclosed square-shaped box, typically with high walls to prevent rodents from escaping11. OFT is recorded range from 5 minutes to an hour, depending on the experimental design, often with automated tracking systems11. Rodents naturally exhibit thigmotactic behavior, a tendency to stay close to the walls of the arena while avoiding the more exposed center area11. During OFT, behavioral parameters recorded include total distance traveled, number and duration of rearing and grooming bouts, freezing behavior, fecal boli count, and particularly, time spent in the center area12. Among these, reduced time spent in the center area is most commonly interpreted as an indicator of heightened anxiety-like behavior11.

In the past, reduced locomotion in the OFT was also interpreted as heightened “emotionality” or anxiety10. However, subsequent pharmacological studies have demonstrated that overall locomotion is not a reliable index of anxiety since non-anxiolytic drugs can also influence movement patterns10. As a result, general ambulation is now considered a poor standalone marker of anxiety-like behavior10. In addition, distinguishing between anxiety-driven avoidance and reduced locomotion could be difficult due to other factors, such as sedation, fatigue, or motor deficits10. Furthermore, anxiolytic drugs do not always lead to increased center-area exploration, which makes the interpretation of pharmacological effects complicated10. Due to these issues, results obtained from the OFT are often considered preliminary, and it is recommended that researchers corroborate findings with more specific complementary tests such as the light-dark box test or elevated plus maze test to obtain a more comprehensive evaluation of anxiety-related behavior12.

Quantification of thigmotaxis, the tendency of rodents to remain close to the walls of the arena, can be performed using automated video tracking software or manual scoring based on time or distance spent within a defined peripheral zone. The definition of the central zone is not standardized and can substantially influence test outcomes: for instance, a larger center area tends to increase apparent anxiety-like behavior by reducing time spent in the center, whereas smaller central zones may mask subtle differences between treatment groups. Therefore, consistent zone definitions and transparent reporting of arena dimensions are critical for cross-study reproducibility10‘11.

Light-Dark Box Test (LDBT)

The light-dark box test (LDBT) is a modified version of OFT, which offers a more ethologically relevant environment to evaluate anxiety-like behaviors in rodents. The apparatus is typically divided into two equal compartments: a brightly illuminated chamber (~400 Lux) that is uncovered and a dark chamber that is enclosed with opaque walls and covered. However, some laboratories employ a modified configuration in which approximately two-thirds of the space is illuminated and one-third is enclosed, depending on experimental goals or apparatus design13‘14. Rodents typically stay in small and enclosed spaces as a natural tendency, thereby preferring the dark compartment13‘15. However, they are also driven to investigate the brightly lit area due to their innate curiosity and exploratory drive13‘15. During the test, the animal is placed in the illuminated compartment, and its behavior is monitored for 10 minutes13‘15. The time spent in each compartment and the number of transitions between the light and dark chambers are key measurements for this test13‘15. An enhancement in the time spent in the illuminated compartment is generally interpreted as an anxiolytic behavior13‘15. Additional parameters such as latency to enter the dark compartment, rearing behavior, and risk-assessment behaviors (e.g., peeking from the dark side before retreating) have also been used to assess anxiety-like behavior, although these are less frequently reported in standard protocols13‘15. The most reliable and consistent measurement is the time spent in the bright compartment for assessing anxiety-like behavior, particularly in response to anxiolytic compounds15. This parameter offers a relatively stable baseline and has demonstrated dose-dependent sensitivity to pharmacological interventions, making the LDBT a reliable tool for screening anxiety-modulating agents in preclinical models15.

Elevated Plus Maze Test (EPMT)

The elevated plus maze test (EPMT) is the most extensively used behavioral paradigm for assessing anxiety-like behavior in rodents and evaluating the effects of anxiolytic agents16. This test was originally developed for rats17 and later adapted for mice18. The EPM apparatus consists of a plus-shaped platform with two closed arms and two open arms, all elevated 50–100 cm above the ground19. Unlike the open field test (OFT) and light-dark box test (LDBT), where the anxiety-provoking factor is exposure to an open or brightly lit area, the primary anxiogenic stimulus in the EPMT is the lack of walls or protective cues in the open arms rather than height, which creates a conflict between exploratory drive and fear of open spaces19. During the test, the animal is placed in the center of the maze, facing the same direction as the apparatus, and its behavior is monitored for 5–10 minutes10‘20. The time spent in the open arms and the number of entries into open arms are the two primary analyses used to assess anxiety levels20. Rodents with higher anxiety-like states tend to spend more time in the closed arms and avoid the open arms, reflecting their preference for protected environments20. Conversely, increased time spent in the open arms or more frequent entries to open arms are interpreted as reductions in anxiety, particularly in response to anxiolytic drug administration20. While the EPMT is valued for high sensitivity to pharmacological manipulation and strong ethological relevance, interpretation of staying in the center area, where animals often hesitate, can be ambiguous. Also, variability in baseline anxiety across strains or test conditions should be carefully considered3.

Elevated Zero Maze Test (EZMT)

The elevated zero maze (EZM) is a modified version of the elevated plus maze (EPM), designed to reduce interpretational ambiguity while preserving the core principle of approach-avoidance conflict21. The EZM consists of a circular, annular platform divided into alternating “open” and “closed” quadrants, elevated above the floor21. A key advantage of this design is the elimination of the center found in the EPM, which often creates ambiguity in interpreting the meaning of staying in the center area21. The circular design also encourages mice to explore more continuously10. During a 5–10 minute session, the rodent is placed at the boundary between an open and a closed quadrant, typically facing inward toward the closed area10‘22. The time spent in the open areas, latency to enter an open area, and number of open quadrant entries are the primary measurements for evaluating anxiety-like behavior10. These variables have been shown to be sensitive to anxiolytic drugs such as benzodiazepines, zolpidem, and phenobarbitone, supporting the EZMT’s validity as a tool for assessing anxiety-like behavior and pharmacological effects in rodent models10.

OFT, LDBT, EPMT, and EZMT are widely used to evaluate anxiety-like behavior in rodents due to their simplicity, minimal equipment requirements, and ethological relevance23. These tests depend on natural characteristics of rodents, the conflicts between aversion to open or bright spaces and the drive to explore novel environments23. They have been used to assess anxiety-like behavior and pharmacological responses as non-invasive and cost-effective methods23. Despite these advantages, several drawbacks should be considered23. First, these tests primarily rely on the rodents’ natural instinct to avoid open/exposed areas, which may not fully capture the multifaceted aspect of anxiety-like behavior23. Due to inconsistent data from different anxiolytic drugs, external validity is often questioned23. Repeated exposures may also lead to habituation, reducing the sensitivity to detect anxiogenic or anxiolytic effects23. Additionally, other aspects, including strain, sex, age, and environmental variables (e.g., lighting, noise, temperature), can significantly affect outcomes, which may cause unexpected results23.

Despite these concerns, these assays remain valuable components of anxiety research. When combined with physiological markers, such as corticosterone levels, stress-induced hyperthermia, or heart rate variability, behavioral tests can contribute to a more robust and comprehensive understanding of anxiety-related phenomena in rodents7‘8‘24. To increase reproducibility and translational value, using multiple complementary tests and explaining clearly regarding experimental context should be carefully considered8. To ensure ethical standards, researchers need to minimize stress in animals and ensure they are properly habituated before testing.

Physiological Measures of Anxiety in Rodents

Physiological measures could provide a complementary approach for assessing anxiety-like states in rodents. These measures are particularly useful when behavioral outcomes are ambiguous or when researchers aim to investigate the biological mechanisms underlying anxiety7‘8‘24.

Corticosterone, the primary glucocorticoid hormone in rodents, is the most commonly used biochemical marker for stress and anxiety24. Corticosterone levels could be measured in plasma, serum, saliva, or fecal samples, typically via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or radioimmunoassay techniques24. Since corticosterone levels increase in response to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation, they are considered as a physiological indicator of emotional arousal24. However, there are several limitations: sample collection itself could be stressful, introducing confounding elevation of hormone levels; and temporal dynamics of hormone secretion may not always align with acute behavioral observations8. Furthermore, studies have shown that corticosterone levels do not always correlate with anxiety-like behavior results, highlighting the importance of context-dependent interpretation8‘25.

Stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH) is also a well-established indicator of emotional arousal7. This method monitors changes in core or peripheral temperature following mild handling or environmental challenge7. An increase of approximately 1.2–1.9 °C of body temperature is typically observed, which is sensitive to anxiolytic drugs and experimental manipulations7. Despite SIH being a rapid, non-invasive, and repeatable method, it can vary depending on strain, sex, and environmental conditions7.

Heart rate variability (HRV) reflects the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity, and reductions in HRV are often associated with heightened anxiety states26. While HRV provides insight into autonomic regulation, its measurement in rodents requires surgical implantation of telemetry devices or non-invasive ECG setups26, both of which are technically demanding.

Lastly, infrared thermography has emerged as a promising technique for assessing surface temperature changes, particularly in the tail, ears, or periorbital regions27. These shifts are correlated with stress-induced vasoconstriction or dilation and are used to infer emotional states27. This approach is entirely non-invasive and can be applied longitudinally. However, it remains vulnerable to environmental noise such as lighting, humidity, and cage temperature27.

Each of these physiological measures offers unique insights, but none are without limitations. Therefore, the current consensus in the field suggests that physiological markers should be interpreted in conjunction with behavioral data, rather than in isolation7‘8‘24. Combining multiple approaches enhances construct validity and provides a more comprehensive understanding of anxiety-related phenomena in preclinical models7‘8‘24.

Neural Circuits Underlying Anxiety-Like Behaviors

Anxiety-like behavior in rodents emerges from a complex interaction among neural circuits that process threat, uncertainty, and stress. Central among these are the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), regions collectively referred to as the extended amygdala network.

The central amygdala (CeA) and BNST play critical and partially complementary roles. The CeA is primarily involved in rapid, phasic fear responses to immediate threats, while the BNST mediates sustained anxiety during prolonged or ambiguous stressors. Hyperexcitability of CeA somatostatin-positive (SOM⁺) neurons has been shown to suppress inhibitory signaling toward the BNST, increasing its activity and promoting anxiety-like behavior28. This CeA–BNST pathway is a major driver of chronic anxiety and stress-related behavioral alterations.

The hippocampus and PFC further regulate anxiety expression through top-down control and contextual processing. The ventral hippocampus (vHPC) encodes environmental context and safety information, while projections from the medial PFC modulate amygdala and BNST activity to regulate adaptive versus maladaptive anxiety responses29. Dysfunction within this regulatory circuit may lead to excessive avoidance behavior and impaired fear extinction, as observed in generalized anxiety models.

In behavioral paradigms such as the elevated plus maze or open field test, manipulations that reduce BNST excitability consistently decrease avoidance of open or illuminated areas, indicating a causal link between circuit dynamics and measurable anxiety-like outcomes. Importantly, many of these neural signatures are conserved across species, supporting the translational relevance of circuit-level findings in rodents to human anxiety disorders30.

Together, these data emphasize that behavioral readouts of anxiety are not merely descriptive but can be mechanistically interpreted through well-characterized neural circuits. Incorporating circuit-level perspectives strengthens the construct validity of rodent anxiety models and enables alignment with human neuroimaging findings.

Discussion

Assessing anxiety-like behavior in rodents requires a multidimensional approach that accounts for both observable behavior and underlying physiological changes. While behavioral tests such as the open field test (OFT), light–dark box test (LDBT), elevated plus maze test (EPMT), and elevated zero maze test (EZMT) offer relatively straightforward and ethologically relevant results to examine anxiety-like responses, they have limitations that need to be considered. Many of these paradigms rely on approach–avoidance conflict and spontaneous exploratory drive, which can be influenced by various factors such as locomotor activity, novelty preference, strain differences, and even ambient noise or lighting. For example, historically, reduced locomotion in the OFT was considered an indicator of increased anxiety-like behavior. After thorough consideration of different studies with inconsistent results using various anxiolytic medications, this assumption is no longer generally applicable.

Physiological assays provide complementary methods to evaluate anxiety-like behavior because they offer more direct information about internal states that accompany anxiety. Corticosterone quantification, stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH), heart rate variability (HRV), and infrared thermography are commonly employed physiological assessments. Specifically, corticosterone is widely considered a biomarker of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activation in stress models24. However, this physiological marker is not an impeccable measurement24. It is also subject to fluctuation due to handling, sampling methods, and temporal dynamics of secretion24. Similarly, while SIH offers a reliable and rapid index of emotional arousal, it is also sensitive to strain, sex, and environmental variability7. HRV and thermal imaging are promising as non-invasive techniques, yet they are not always feasible in standard lab settings due to technical complexity or susceptibility to environmental noise26‘27.

Both behavioral and physiological measures provide complementary information to assess anxiety-like behavior, and neither should be interpreted in isolation. Behavioral outcomes provide information not only about anxiety state but also about general arousal, attention, or motor function. Meanwhile, physiological markers may or may not align with behavioral changes depending on timing, stressor type, or measurement method. Importantly, studies have shown that behavioral and physiological measures do not always correlate, underscoring the need for integrative, multidimensional approaches to assessing anxiety-like states in rodents7‘8‘24. Therefore, future studies should aim to develop standardized testing protocols that combine multiple behavioral and physiological endpoints to increase validity. Such integrative approaches may strengthen experimental reliability and enhance translational relevance when studying human anxiety disorders. Lastly, careful attention to strain selection, experimental conditions, and ethical considerations will be essential to improve reproducibility and refine our understanding of anxiety-related mechanisms.

Translational Validity of Rodent Anxiety Tests

The utility of rodent models in anxiety research largely depends on their translational validity—that is, how well behavioral outcomes predict or reflect clinical phenomena in humans. Three classical dimensions of validity are typically used to evaluate these models: face, construct, and predictive validity31‘32.

Face validity refers to the extent to which rodent behavior resembles human anxiety symptoms. For example, reduced exploration in the open field or open arms of the elevated plus maze superficially parallels avoidance behaviors in anxious patients. However, not all anxiety manifestations (e.g., cognitive worry or anticipatory tension) have direct behavioral analogs in rodents31‘32.

Construct validity concerns whether the underlying neurobiological mechanisms align with human anxiety pathology. Models incorporating dysregulation of the amygdala–BNST–PFC network, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis alterations, or serotonergic imbalance show stronger construct validity than those based solely on behavioral observation3.

Predictive validity evaluates whether pharmacological responses in rodents forecast clinical efficacy. Classical anxiolytics such as benzodiazepines consistently reduce avoidance behavior across tests, supporting strong predictive validity. In contrast, serotonergic agents like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) exhibit acute anxiogenic effects in rodents despite long-term anxiolysis in humans, highlighting translational limitations33.

Improving translational validity requires integrating behavioral, physiological, and neural measures within the same experimental framework. Incorporating automated video analysis, physiological biomarkers (e.g., corticosterone, heart rate variability), and circuit-based manipulations can bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical research.

In addition to classical unconditioned paradigms, several cognitive and conflict-based tasks have been developed to assess higher-order dimensions of anxiety. These include the novelty-suppressed feeding test, stress-induced potentiation of the startle response, and operant risk-assessment paradigms, which probe decision-making under uncertainty, attentional bias, and risk evaluation. Integrating such tasks alongside traditional assays broadens the behavioral repertoire captured in rodents and provides a more comprehensive representation of the cognitive and affective components of human anxiety3‘32.

Future studies should explicitly state which dimensions of validity each assay addresses and interpret findings accordingly, rather than assuming direct equivalence with human anxiety disorders34.

Pharmacological Paradoxes and Predictive Limitations

While rodent anxiety paradigms have been instrumental in identifying compounds with anxiolytic potential, several well-documented pharmacological paradoxes limit their predictive validity. Classical benzodiazepines such as diazepam and lorazepam reliably increase open-arm exploration in the elevated plus maze and light exposure in the light–dark box, confirming strong predictive validity for this drug class. However, newer or non-benzodiazepine agents often display inconsistent or even paradoxical outcomes.

One notable example involves selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Acute SSRI administration in rodents typically produces anxiogenic effects, manifested as decreased open-arm entries or increased thigmotaxis, despite their well-established anxiolytic efficacy after chronic treatment in humans35. This discrepancy reflects both pharmacodynamic differences across time scales and the complex role of serotonin in modulating defensive behaviors.

Similarly, buspirone, a partial 5-HT₁A receptor agonist with proven clinical anxiolytic action, often produces subtle or null behavioral changes in rodent tests16. The limited responsiveness of such non-benzodiazepine drugs suggests that many current paradigms preferentially capture behaviors linked to acute sedative or motor-relaxant effects rather than sustained anxiety reduction.

To contextualize these discrepancies, Table 1 summarizes the comparative predictive performance of representative anxiolytic classes in rodent assays, and Table 2 compiles major sources of false positives and negatives that contribute to translational failure.

| Drug class | Example compounds | Typical rodent response | Clinical correlation | Predictive validity |

| Benzodiazepines | Diazepam, Lorazepam | Robust increase in open-arm/light exploration | Strong | High |

| SSRIs (acute) | Fluoxetine, Sertraline | Decreased exploration (anxiogenic) | Opposite to chronic human outcome | Low |

| SSRIs (chronic) | Fluoxetine (≥14 days) | Normalization or mild increase in exploration | Moderate | Moderate |

| 5-HT₁A agonists | Buspirone, Tandospirone | Weak or inconsistent | Positive clinical effect | Low-moderate |

| GABA-B modulators | Baclofen | Sedation confounds interpretation | Limited data | Uncertain |

Source of bias | Description | Representative outcome |

| Sedative or locomotor effects | Reduced exploration misinterpreted as “anxiolytic” | False positive |

| Strain or sex variability | Divergent baseline anxiety profiles | False positive/negative |

| Habituation and retesting | Diminished avoidance after repeated exposure | False negative |

| Environmental factors (light, noise) | Altered thigmotaxis and locomotion | False positive/negative |

| Non-specific pharmacological effects | Motor impairment or altered arousal | False positive |

These paradoxes highlight that behavioral readouts alone are insufficient for evaluating anxiolytic efficacy. Integrating physiological and circuit-level biomarkers (e.g., heart-rate variability, corticosterone dynamics, and neural activity mapping) can help discriminate true anxiolytic effects from confounding sedative or motor influences. Establishing standardized multimodal endpoints across laboratories will be critical to enhance the predictive validity of preclinical anxiety assays.

Biological and Environmental Modulators of Anxiety-Like Behavior

Behavioral and physiological measures of anxiety in rodents are highly sensitive to biological and environmental variables. Ignoring these factors can lead to misinterpretation of test outcomes and contribute to the low reproducibility of preclinical findings. Sex differences represent one of the most consistent modulators. Female rodents often display higher baseline anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze and light–dark box, potentially linked to estrogen-dependent modulation of amygdala and HPA-axis reactivity36. Hormonal cycling further influences corticosterone secretion and exploratory drive, suggesting that estrous phase should be monitored or experimentally controlled.

Age also affects test sensitivity. Juvenile and aged animals frequently exhibit exaggerated or blunted avoidance responses relative to adults, respectively, reflecting developmental and neuroendocrine differences37. Incorporating age-matched cohorts is therefore essential for consistent interpretation.

Strain and genetic background substantially impact baseline anxiety and drug responsiveness. For example, C57BL/6 mice generally show lower anxiety scores compared to BALB/c mice, and strain-specific differences in locomotion can confound measures such as open-arm entries7.

Circadian variation further modulates both behavioral and endocrine endpoints. Corticosterone levels can fluctuate more than ten-fold across the light–dark cycle in rats, producing marked differences in anxiety test outcomes depending on the time of day38. Standardizing testing periods within the active phase of each species is thus recommended to improve reproducibility.

Environmental factors such as ambient noise, light intensity, and prior handling also exert measurable effects on anxiety-like behavior39. Consistent laboratory conditions and adherence to ARRIVE 2.0 Essential 10 guidelines will facilitate transparent reporting and enhance cross-study comparability40.

Integrative Framework: Combining Behavioral and Physiological Measures

An integrated assessment of anxiety-like behavior in rodents benefits from concurrent measurement of behavioral, physiological, and neurobiological indices within the same experimental framework41. This multimodal approach enhances construct validity and provides a more holistic interpretation of anxiety-related phenomena.

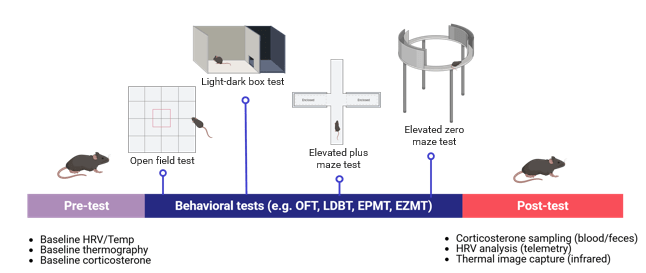

In a typical experimental timeline (illustrated schematically in Figure 2), baseline physiological parameters such as heart rate, core temperature, or corticosterone levels can be recorded before exposure to the behavioral assay. During the testing phase—for example, the elevated plus maze or open field—video-tracking software captures locomotor trajectories and postural dynamics, while telemetry or infrared thermography continuously monitors autonomic and thermal responses7‘27. Post-test sampling (e.g., plasma or fecal corticosterone assays) provides delayed physiological readouts of stress reactivity.

Integrating these temporal layers—pre-test baseline, in-test dynamics, and post-test recovery—allows for cross-validation between behavioral and biological responses. For instance, animals exhibiting high thigmotaxis or avoidance behavior typically display concurrent elevations in heart-rate variability or corticosterone output, supporting convergent validity. Conversely, dissociation between behavioral and physiological indices may indicate confounding variables such as sedation or motor impairment rather than true anxiolysis7‘26.

This schematic integration also facilitates correlation with neural circuit activity assessed via c-Fos mapping, fiber photometry, or in vivo calcium imaging, thereby linking observed behavior to underlying neural substrates. Collectively, multimodal designs as depicted in Figure 2 can substantially improve reproducibility, mechanistic interpretation, and translational relevance of rodent anxiety research41.

In recent years, the integration of machine-learning–based behavioral quantification tools has further advanced the precision and reproducibility of anxiety testing in rodents. Systems such as DeepLabCut, B-SOiD, and SimBA employ markerless pose estimation and unsupervised clustering to extract high-dimensional behavioral features from raw video data42‘43‘44. These approaches enable automated scoring of subtle actions such as head dips, rearing, or stretch-attend postures—behaviors that are often overlooked or subject to observer bias in manual analyses. When combined with physiological recordings (e.g., heart-rate telemetry, infrared thermography), such computational pipelines can yield multidimensional behavioral phenotypes that align more closely with underlying neural dynamics and improve cross-laboratory reproducibility7‘27.

Methods

A focused literature review was conducted to examine how anxiety-like behavior is assessed in rodent models using both behavioral and physiological methods. Searches were performed using PubMed and Google Scholar between January 2000 and June 2025, with the most recent search completed on June 15, 2025. The primary search terms included “anxiety-like behavior” AND “rodent” OR “mice” OR “rat” combined with “open field test,” “light-dark box,” “elevated plus maze,” or “elevated zero maze.” Additional terms such as “corticosterone,” “stress-induced hyperthermia,” “heart rate variability,” and “infrared thermography” were used to identify studies incorporating physiological endpoints. Secondary searches targeted neural circuits, machine-learning behavioral analysis, and translational validity. Peer-reviewed, English-language articles were included; however, earlier studies were considered if they described essential or foundational assay protocols. Studies were included if they (1) used rodent models (mice or rats), (2) clearly described the test apparatus and procedures, and (3) reported key outcome metrics such as time spent in anxiogenic zones, entries, and latency. For physiological measures, studies needed to describe methods for assessing corticosterone levels, core or surface temperature changes, or autonomic regulation via ECG or thermography. Data extracted from each study included the test used (e.g., OFT, LDBT, EPMT, EZMT), session duration, initial animal placement, behavioral outcomes (e.g., time in open arms, number of entries), and physiological parameters (e.g., method of corticosterone sampling, thermal camera settings, ECG setup). This information was synthesized to compare the strengths and limitations of each approach and highlight the benefits of integrated assessments. The search strategy and inclusion criteria were reported transparently to enhance methodological rigor and reproducibility.

References

- Association, A. P., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, (2013). [↩]

- Kristína Belovičová, K. Belovičová, Eszter Bögi, E. Bögi, Kristína Csatlósová, K. Csatlosova, Michal Dubovický, and M. Dubovicky, Animal tests for anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in rats, Interdisciplinary Toxicology, 10, 40–43, (2017). [↩]

- Sinem Gencturk and Gunes Unal, Rodent tests of depression and anxiety: construct validity and translational relevance, Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Güneş Ünal, Gunes Unal, Ahmed A. Moustafa, and Ahmed A. Moustafa, The neural substrates of different depression symptoms: animal and human studies, The Nature of Depression [↩]

- Thierry Steimer and T. Steimer, Animal models of anxiety disorders in rats and mice: some conceptual issues, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13, 495–506, (2011). [↩]

- Michel Bourin, M. Bourin, Benoît Petit-Demoulière, B. Petit-Demouliere, Brid Nic Dhonnchadha, B. Á. N. Dhonnchadha, Martine Hascoët, and M. Hascoët, Animal models of anxiety in mice, Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology, 21, 567–574, (2007). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- J. Adriaan Bouwknecht, J. A. Bouwknecht, Richard Paylor, and R. Paylor, Behavioral and physiological mouse assays for anxiety: a survey in nine mouse strains, Behavioural Brain Research, 136, 489–501, (2002). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Elizabeth S. Paul, E. S. Paul, Emma J. Harding, E. J. Harding, Michael Mendl, and M. T. Mendl, Measuring emotional processes in animals: the utility of a cognitive approach, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 29, 469–491, (2005). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jaap M. Koolhaas, J. M. Koolhaas, Alessandro Bartolomucci, A. Bartolomucci, Bauke Buwalda, B. Buwalda, Sietse F. de Boer, S. F. de Boer, Gabriele Flügge, G. Flügge, S. Mechiel Korte, S. M. Korte, Peter Meerlo, P. Meerlo, Robert Murison, R. Murison, Berend Olivier, B. Olivier, Paola Palanza, P. Palanza, Gal Richter-Levin, G. Richter-Levin, Andrea Sgoifo, A. Sgoifo, Thierry Steimer, T. Steimer, Oliver Stiedl, O. Stiedl, G. van Dijk, Gertjan van Dijk, G. van Dijk, Markus Wöhr, M. Wöhr, Eberhard Fuchs, Eberhard Fuchs, and E. Fuchs, Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 1291–1301, (2011). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Laura B. Tucker, L. B. Tucker, Joseph T. McCabe, and J. T. McCabe, Measuring anxiety-like behaviors in rodent models of traumatic brain injury, Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- M. Lamar Seibenhener, M. L. Seibenhener, Michael C. Wooten, and M. C. Wooten, Use of the open field maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice, Journal of Visualized Experiments, (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jacqueline N. Crawley and J. N. Crawley, What’s wrong with my mouse?, (2007). [↩] [↩]

- Michel Bourin, M. Bourin, Martine Hascoët, and M. Hascoët, The mouse light/dark box test, European Journal of Pharmacology, 463, 55–65, (2003). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jacqueline N. Crawley, J. N. Crawley, Frederick K. Goodwin, F. K. Goodwin, and F. K. Goodwin, Preliminary report of a simple animal behavior model for the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines, Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 13, 167–170, (1980). [↩]

- Martine Hascoët, M. Hascoët, and M. Bourin, A new approach to the light/dark test procedure in mice, Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 60, 645–653, (1998). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- József Haller, J. Haller, Manó Aliczki, M. Aliczki, Katalin Gyimesine Pelczer, and K. G. Pelczer, Classical and novel approaches to the preclinical testing of anxiolytics: a critical evaluation, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37, 2318–2330, (2013). [↩] [↩]

- Sharon Pellow, S. Pellow, Philippe Chopin, P. Chopin, Sandra E. File, S. E. File, Mike Briley, and M. Briley, Validation of open:closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat, Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 14, 149–167, (1985). [↩]

- Richard G. Lister and R. G. Lister, Ethologically-based animal models of anxiety disorders, Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 46, 321–340, (1990). [↩]

- Dallas Treit, D. Treit, Janet L. Menard, J. Menard, Cary Royan, and C. Royan, Anxiogenic stimuli in the elevated plus-maze, Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 44, 463–469, (1993). [↩] [↩]

- Munekazu Komada, M. Komada, Keizo Takao, K. Takao, Tsuyoshi Miyakawa, and T. Miyakawa, Elevated plus maze for mice, Journal of Visualized Experiments, 1088, (2008). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jonathan Paul Shepherd, J. K. Shepherd, Savraj Grewal, S. S. Grewal, Allan Fletcher, A. Fletcher, David J. Bill, D. J. Bill, C. T. Dourish, and C. T. Dourish, Behavioural and pharmacological characterisation of the elevated “zero-maze” as an animal model of anxiety, Psychopharmacology, 116, 56–64, (1994). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- KathrynAnn E. Odamah, Mauricio Toyoki Nishizawa Criales, and Hengye Man, NEXMIF overexpression is associated with autism-like behaviors and alterations in dendritic arborization and spine formation in mice, Frontiers in Neuroscience, (2025). [↩]

- Abdelkader Ennaceur and A. Ennaceur, Tests of unconditioned anxiety – pitfalls and disappointments, Physiology & Behavior, 135, 55–71, (2014). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Mandakh Bekhbat, M. Bekhbat, Erica R. Glasper, E. R. Glasper, Sydney A. Rowson, S. A. Rowson, Sean D. Kelly, S. D. Kelly, Gretchen N. Neigh, and G. N. Neigh, Measuring corticosterone concentrations over a physiological dynamic range in female rats, Physiology & Behavior, 194, 73–76, (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Viktoria Krakenberg, V. Krakenberg, Sophie Siestrup, S. Siestrup, Rupert Palme, R. Palme, Sylvia Kaiser, S. Kaiser, Norbert Sachser, N. Sachser, S. Helene Richter, and S. H. Richter, Effects of different social experiences on emotional state in mice, Scientific Reports, 10, 15255, (2020). [↩]

- Stefano Gaburro, S. Gaburro, Oliver Stiedl, O. Stiedl, Pietro Giusti, P. Giusti, Simone Sartori, S. B. Sartori, Rainer Landgraf, R. Landgraf, Nicolas Singewald, and N. Singewald, A mouse model of high trait anxiety shows reduced heart rate variability that can be reversed by anxiolytic drug treatment, The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 14, 1341–1355, (2011). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Karen Gjendal, K. Gjendal, Nuno Henrique Franco, N. H. Franco, Jan Lund Ottesen, J. L. Ottesen, Dorte Bratbo Sørensen, D. B. Sørensen, I. Anna S. Olsson, and I. A. S. Olsson, Eye, body or tail? Thermography as a measure of stress in mice, Physiology & Behavior, 196, 135–143, (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ahrens, S., M. V. Wu, A. Furlan, G.-R. Hwang, R. Paik, H. Li, M. A. Penzo, J. Tollkuhn, and B. Li, A central extended amygdala circuit that modulates anxiety, The Journal of Neuroscience, 38, 5567–5583, (2018). [↩]

- Glover, L. R., K. M. McFadden, M. Bjorni, S. R. Smith, N. G. Rovero, S. Oreizi-Esfahani, T. Yoshida, A. F. Postle, M. Nonaka, L. R. Halladay, and A. Holmes, A prefrontal–bed nucleus of the stria terminalis circuit limits fear to uncertain threat, eLife, 9, e60812, (2020). [↩]

- Poll, Y. van de, Y. Cras, and T. J. Ellender, The neurophysiological basis of stress and anxiety – comparing neuronal diversity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) across species, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 17, 1225758, (2023). [↩]

- Robinson, E. S. J., Improving the translational validity of methods used to study depression in animals, Psychopathology Review, a3, 41–63, (2016). [↩] [↩]

- Lezak, K. R., G. Missig, and W. A. Carlezon Jr., Behavioral methods to study anxiety in rodents, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19, 181–191, (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Bach, D. R., Cross-species anxiety tests in psychiatry: pitfalls and promises, Molecular Psychiatry, 27, 154–163, (2022). [↩]

- Belzung, C. and G. Griebel, Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: a review, Behavioural Brain Research, 125, 141–149, (2001). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Griebel, G. and A. Holmes, 50 years of hurdles and hope in anxiolytic drug discovery, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 12, 667–687, (2013). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Goel, N., J. L. Workman, T. T. Lee, L. Innala, and V. Viau, Sex differences in the HPA axis, Comprehensive Physiology, 4, 1121–1155, (2014). [↩]

- Shoji, H., K. Takao, S. Hattori, and T. Miyakawa, Age-related changes in behavior in C57BL/6J mice from young adulthood to middle age, Molecular Brain, 9, 11, (2016). [↩]

- Atkinson, H. C. and B. J. Waddell, Circadian variation in basal plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropin in the rat: sexual dimorphism and changes across the estrous cycle, Endocrinology, 138, 3842–3848, (1997). [↩]

- Saré, R. M., A. Lemons, and C. B. Smith, Behavior testing in rodents: highlighting potential confounds affecting variability and reproducibility, Brain Sciences, 11, 522, (2021). [↩]

- Percie du Sert, N., V. Hurst, A. Ahluwalia, S. Alam, M. T. Avey, M. Baker, W. J. Browne, A. Clark, I. C. Cuthill, U. Dirnagl, M. Emerson, P. Garner, S. T. Holgate, D. W. Howells, N. A. Karp, S. E. Lazic, K. Lidster, C. J. MacCallum, M. Macleod, E. J. Pearl, O. H. Petersen, F. Rawle, P. Reynolds, K. Rooney, E. S. Sena, S. D. Silberberg, T. Steckler, and H. Würbel, The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research, BMC Veterinary Research, 16, 242, (2020). [↩]

- Steimer, T., Animal models of anxiety disorders in rats and mice: some conceptual issues, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13, 495–506, (2011). [↩] [↩]

- Mathis, A., P. Mamidanna, K. M. Cury, T. Abe, V. N. Murthy, M. W. Mathis, and M. Bethge, DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning, Nature Neuroscience, 21, 1281–1289, (2018). [↩]

- Hsu, A. I. and E. A. Yttri, B-soid, an open-source unsupervised algorithm for identification and fast prediction of behaviors, Nature Communications, 12, 5188, (2021). [↩]

- Goodwin, N. L., J. J. Choong, S. Hwang, K. Pitts, L. Bloom, A. Islam, Y. Y. Zhang, E. R. Szelenyi, X. Tong, E. L. Newman, K. Miczek, H. R. Wright, R. J. McLaughlin, Z. C. Norville, N. Eshel, M. Heshmati, S. R. O. Nilsson, and S. A. Golden, Simple behavioral analysis (SiMBA) as a platform for explainable machine learning in behavioral neuroscience, Nature Neuroscience, 27, 1411–1424, (2024). [↩]