Abstract

Diseases represent significant barriers to human progress. Ineffective drug delivery processes exacerbate this issue, as the lack of methods to engineer and implement the drug-device complexes needed to efficiently deliver drugs leads to the failure of countless treatment endeavors. Among other alternatives, extracellular vesicles (EVs) possessing therapeutic content like proteins or small nucleic acids are considered novel therapeutic tools with medicinal benefits. Particularly, EVs derived from adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC-EVs) are useful because of their ability to facilitate intercellular communication and the transfer of biological information. Thus, encapsulation of MSC-EVs in injectable hydrogels for controlled and sustained EVs release could maximize the efficiency of a MSC-EVs treatment. Injectability of hydrogels creates an easy way for effective delivery where the injected material can be allocated at the target site, like a drug depot to enable controlled EVs release. In this study, EVs encapsulated injectable hydrogels (EVs-hydrogels) that can be either UV-crosslinked or temperature-induced enabled noninvasive injection, colocalization, and controlled EVs release at the injury site. The hydrogel structure was analyzed by the Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The EVs were isolated from MSCs and characterized. We gathered an understanding of the release profile of EVs (in EV number and protein content) by quantifying the released EVs. The biological activity of the released EVs were also qualitatively tested on PC12 cells to measure neurite outgrowth. Overall, this study provides us with scientific insights to potentially promote long-term therapeutic activity of MSC-EVs, aimed at effectively treating disorders/diseases in the future.

Keywords: drug delivery, hydrogel, extracellular vesicles, controlled release

Introduction

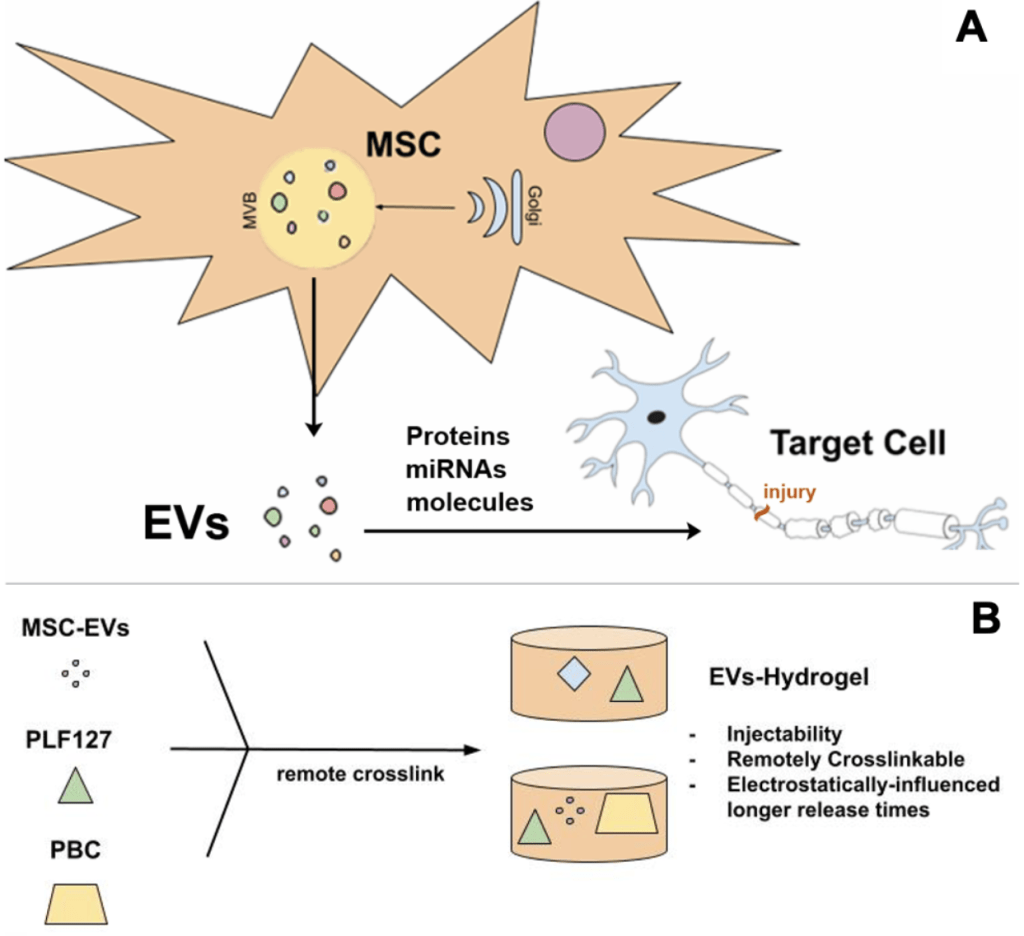

The field of hydrogel research has been intriguing for researchers and clinicians for its versatility in the development and implementation of a wide variety of scientific techniques. For a large part, interest in hydrogels can be attributed to its potential for rectifying ineffective drug delivery, which can have serious impacts. Ineffective drug delivery acts as a serious impediment to the effective implementation of many drugs, largely through the altering of diffusion rates. Furthermore, physiokinetic studies have proven distribution inhomogeneity, rapid efflux, and consequent treatment failures may often result from ineffective drug delivery1. Still, ineffective drug delivery can even lead to the incorrect grouping of effective and ineffective drugs together as ultimately unsuccessful remedies, creating potential for unjustified backlash from the drug manufacturing industry or elsewhere1. As a solution, hydrogel structures are renowned for their capability to promote the release of its contents, usually drugs, in a controlled manner, because of characteristics allowing for diffusion and controllable degradation2. Having such a controlled release capability is remarkable, because applying a more precise and concentrated dose of a drug can mean more effective, nuanced, and adaptable treatments. As a result, a hydrogel allows for the improvement of drug delivery processes in a wide range of treatment processes. Additionally, the polymeric nanostructures utilized in hydrogels are especially notable, because of their stimuli-responsive capabilities3. The variation in how these hydrogel structures are created via formulaic changes is very interesting, whether chemically, physically, or otherwise3. These options uncover a wider scope of treatment situations in which the hydrogel can be effectively utilized, creating opportunities for potential applications in the future. In addition, coupling a hydrogel system with a remote synthesis/gelation device (e.g., UV cross-linking upon injection) or stimuli responsiveness (e.g., temperature induced gelation) upon injection into the injury site also greatly increases adaptability4. This can allow for noninvasive treatments allowing co-localization of the drug loaded hydrogels and controlled release of drugs at the injury site for prolonged time periods (Figure 1A and B).

The type of the drugs encapsulated in the hydrogel are just as important. In this study, those drugs stem from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which have been proven to migrate toward the affected site in instances of injury, inflammation, or cancer to aid in the recovery process5‘6‘7. Upon reaching these critical areas, MSCs exert a positive influence on the surrounding cells through paracrine signaling, which enhances cell survival while reducing apoptosis. There, MSC-secreted factors and drugs that pose significant benefits, such as in improving paracrine functions, are released8. In this study, the drug in question is extracellular vesicles (EVs), which have attracted a lot of attention for their therapeutic content composed of different proteins, molecules, and miRNA, and the resulting benefits this cargo can hold9‘10‘11. Specifically, neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory proteins and miRNAs in EVs have been shown to promote neural repair and recovery after neurotrauma. Furthermore, EVs can be modified to transfer the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) into astrocytes, which lead to the reorganization of glial scars into a more suitable environment for axonal regrowth12. In this experiment, the EVs utilized are isolated from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC-EVs) and have been proven to be effective in the promotion of epithelial cell proliferation, a likely result from the previously discussed benefits provided by both MSCs and EVs. Notably, MSC-EVs also exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, attracting macrophages and providing therapeutic benefits through their protein cargo, such as tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 6 protein (TSG-6), which reduces inflammation13. In addition, the miRNAs within EVs facilitate recovery after SCI by promoting tissue regeneration and functional recovery14.

Encasing MSC-EVs in an injectable hydrogel (EVs-hydrogel) has been shown to enhance these effects by enabling controlled release2. Crucially, hydrogel structures allow for the administration of only a predetermined amount of drug. Not too much of the drug, that may potentially lead to toxicity, and not too little, that may lead to resource waste or ineffectiveness. This creates a treatment environment that can be easily manipulated for the desired result. Specifically, a polylysine-based hydrogel (PBHEVs@AGN) supports the sequential release of aminoguanidine to reduce oxidative stress, allowing for sustained EVs delivery for axonal regeneration and inflammation reduction15. In addition, the thermosensitive PLEL hydrogel has been found to ensure prolonged EVs retention at the injury site, facilitating M2 polarization of macrophages and inhibiting neural apoptosis through the Bcl-2 pathway13. Finally, the F127-polycitrate-polyethyleneimine hydrogel (FE@EVs) may provide ultralong EVs release over 56 days, effectively promoting remyelination, scar reduction, and motor recovery after SCI14. Despite the variety of hydrogel-formulating materials that could be used, in this experiment, PLF127 was utilized due to its exceptional versatility that stems from its unique gelation properties that allow it to be liquid in lower temperatures and gel in higher temperatures16. These thermoresponsive properties contribute to the facilitation of the controlled release of active hydrogel contents, such as EVs, ultimately contributing to improved content delivery and treatment effectiveness for the hydrogel system. It is also a material that has special sol-gel capabilities, which may be utilized inside the human body. These characteristics complement the biocompatibility, safety, and injectability of PLF127, preparing the results of this experiment to potentially be applicable in other situations17. Further application of these properties will be expanded on in later sections. Importantly, the EVs-hydrogel also protects the EVs from potentially dangerous environments. In a normal context, the EVs secreted from MSCs or even the MSCs themselves may be misdirected or degraded in the bloodstream. Removing these risks, the hydrogel acts as an exoskeleton-like structure, hedging against these potential dangers.

In this study, we focus on developing an MSC-EVs-incorporated, injectable, and UV-curable and/or temperature-induced hydrogel that can provide sustained release of EVs. The EVs-hydrogel we created is structurally sound, able to be crosslinked through a UV system or temperature response, and capable of delaying/prolonging the release of essential EVs in a concentrated manner (Figure 1A and B). Ultimately, our objective is to develop an EVs-hydrogel that can facilitate the effective, concentrated, and prolonged release of MSC-EVs that can assist in the amelioration of diseases and illnesses.

Methodology

MSCs culture:

MSCs were grown in the maintenance medium (MM) consisting of alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM, Life Technologies) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 4 mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies), and antibiotic-antimycotic, (100X) (Life Technologies). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator and sub-cultured every 2 – 3 days when cells reached 80% confluency18.

Isolation of MSC-EVs

Following the cultivation procedure, 30 mL of serum-free media (SFM) was collected from MSCs in T75 flasks into a centrifuge tube. SFM was later centrifuged in several steps (400 xg for 5 min, 1,500 xg for 10 min, 5,000 g or 10,000 g for 10 min, with using a swinging-bucket rotor 4,000 xg for 30 min at room temperature). In the first three steps, a small amount of SFM was left in the tube to remove remaining cell debris and larger proteins in the SFM. The last centrifugation was held with a centrifugal filter unit (Amicon Ultra-15 100 kDa Centrifugal Filter Unit UFC910024) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. After the filter centrifuge, retentate was collected (~2 mL) and further purified down to 8 mL in PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) 0.0067M (P04), Cytiva SH30256.01) with a size exclusion chromatography column (qEV2 Gen 2 70 nm IC2-70) as manufacturer’s instructions (15.2 mL adjusted buffer volume, 8 mL purified collection volume).

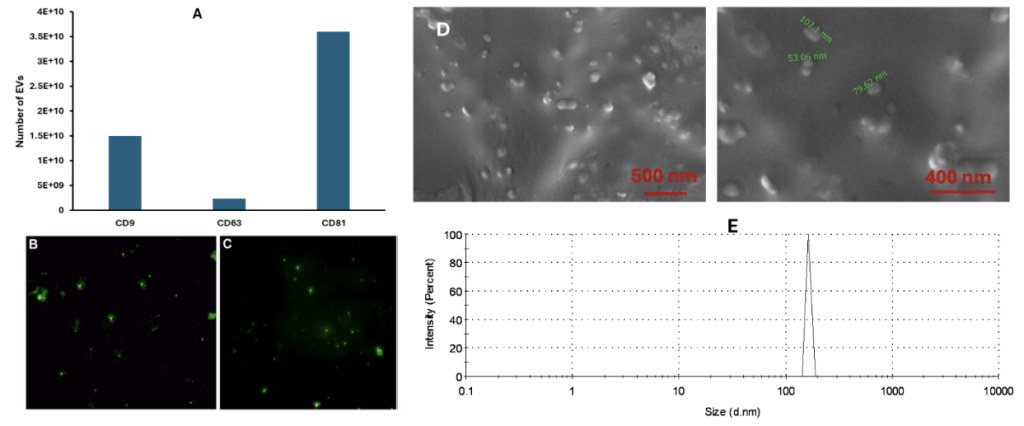

Characterization of EVs

The number and quality of EVs were determined using specific ELISA kits for EVs markers, including CD9, CD63, and CD81 (EXEL-ULTRA-CD9-1, EXEL-ULTRA-CD63-1, and EXEL-ULTRA-CD81-1; System Biosciences) by following the manufacturer’s protocol. These three specific markers are tetraspanin proteins found on the EV membrane. Specifically, as outlined in the MISEV2023 guidelines, EVs are often found to be enriched with these specific tetraspanin proteins along with other proteins such as ALIX (protein regulates cellular mechanisms), MHC1 (major histocompatibility complex 1), and HSP90 (heat shock protein 90), so the existence of CD9, CD63, and CD81 is especially crucial19. The EVs’ protein content and membrane integrity were detected using EV protein and membrane labeling kits (EXOGP300A-1, and EXOGM600A-1; System Biosciences) by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Additionally, EV yield was validated with System Bioscience EXOCET Exosome Quantitation Kit as 3×1010 number of EVs/mL in addition to ELISA measurements. In general nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) is used to detect the yield and size distribution of the EVs, however, we currently do not have access to NTA to perform this experiment. Because of this reason, we quantified the EVs with the mentioned kits and measured their size and distribution using dynamic light scattering and SEM images. The size of the EVs ranged between 50-150 nm as expected. The purity of the EVs was calculated by determining the free protein content in the final EV solution after the isolation. It is reported as the number of EVs per microgram protein. The purity of our EVs was reported as 2×109 EV particles/µg protein.

UV-Crosslinked Hydrogels Formation

The implementation of encapsulating structures must be made flexible, to increase use cases16. Increasing hydrogel remote cross-linking techniques is a solution. Extensive examples have proven the benefits potential cross linking strategies may provide20‘21‘22. Remote crosslinking via UV light, or as will be used by temperature-induction, allows for greater flexibility, bypassing the aforementioned limitations.

Combining 75 mg of pluronic F127 gel (PLF127; a polyoxyethylene-polyoxypropylene surface active block copolymer) with 75 mg of Polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA 4000), 100 uL of an Irgacure 2959 photoinitiator (diluted to 0.2 weight % with methanol solution), and 200 uL of deionized water to yield the gel solution after a day inside a 4°C refrigerator. This solution was slightly viscous and brown. This solution was stored inside a 24-Well Plate (Corning™ Costar™) until the end of the experiment. Following an overnight incubation, the hydrogel solution was exposed to a UV System (OmniCure Series 1500) for 120 seconds to catalyze the gelation process and create a solid and translucent hydrogel.

Pentablock Copolymer Hydrogels

In recent literature and findings, having complementary or inverse electrostatic charge relationships between the hydrogel structure and its molecular cargo have been found to be more exceptional in retaining the aforementioned cargo compared to when the electrostatic relationship is non complementary or direct23. Similarly, this study also decided to utilize a charged copolymer to leverage complementary electrostatic interactions to extend release times. Responsive cationic copolymers were synthesized using atom transfer radical polymerization by following previously published protocols24.

The actual hydrogel incorporated with the isolated EVs (5×1010 EVs per hydrogel formulation) (EVs-hydrogel) was formed using 75 mg of a stimuli responsive cationic copolymer composed of temperature-responsive PLF127 and pH responsive cationic poly(2-(diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate) (PDEAEM)24. This positively charged cationic polymer enables the condensation of negatively charged EVs in the hydrogel via electrostatic interactions. The integrity of this system relies on the proven positive relationship between negatively charged siRNA, or in this experiment, negatively charged EVs, and the positively charged pentablock copolymer24. The rest of the hydrogel formulation was kept the same as the initial trial, and the same UV conditions were applied for cross-linking. In addition, temperature induced gelation was also tested above critical gelation concentrations (above 25 wt%) and temperatures (37 ˚C). The microstructure of hydrogel was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The selected materials for the hydrogel formulation allow for the formed hydrogel to be easily handled along with a remote crosslink process to occur with a UV system, increasing the variety of situations the hydrogel can be implemented in any condition16.

EVs Release Evaluation from UV-crosslinked hydrogels

Following the formation of the hydrogel designated for the experiment, the formed hydrogel (EVs-hydrogel) was placed at the bottom of the well. This leaves enough space to add 2 mL of PBS in a supernatant position. The resulting system would then be placed on the shaker and the PBS was retrieved at designated time intervals. The shaker assists in helping the EVs release from the EVs-hydrogel into the PBS. After retrieval of 2 mL of PBS solution, the same volume of fresh PBS was added back onto the hydrogel. This process was repeated for the designated time intervals.

The released EVs were detected using specific ELISA tests by following the manufacturer’s protocols. In addition, the protein content of the released EVs were also determined using BCA assay.

Temperature-Induced EVs-Hydrogel Formation

A set of hydrogels was developed using the temperature-responsive gelation of the PLF127-containing pentablock copolymer. The cationic block of the pentablock copolymer was used to complement the negatively charged MSC-EVs, while the temperature-responsive block facilitated gelation. Additional PLF127 was incorporated to enhance the temperature-induced gelation and form MSC-EVs-loaded hydrogels (EVs-hydrogel). To prepare the EVs-hydrogels, EVs were complexed with the pentablock copolymer at concentrations of 35%, 40%, and 45% (w/v) in a solution containing EVs for 30 minutes and kept at 4°C to ensure uniform mixing and to form pentablock copolymer/EVs-complex. Simultaneously, PLF127 solutions were prepared at the same weight percentages (45% w/v) in the PBS buffer. 250 µL of the PLF127 solutions and 450 µL of pentablock copolymer/EVs-complex were transferred into 2 mL centrifuge tubes and mixed thoroughly. Then, the mixed hydrogels (700 µL total volume each) were incubated at 37°C for at least 30 minutes to ensure complete gelation. 45% w/v was selected based on our preliminary tests.

Release of EVs from Temperature-Induced EVs-hydrogel

After confirming gelation by observing the formation of a non-liquid, cohesive gel upon incubation, 200 µL of PBS pre-warmed to 37°C was added to the top of each EVs-hydrogel to initiate EVs release. The EVs-hydrogels were incubated at 37°C, and at designated time points, the PBS overlay was carefully collected and replaced with fresh pre-warmed PBS (37°C, 200 µL) to maintain constant release conditions. Collected PBS samples containing the released EVs were stored for subsequent EVs quantification.

Quantification of the released EVs

EVs released from the EVs-hydrogels were quantified by assessing their numbers using specific quantification kits and EV protein content using BCA assay. For the EV concentration, System Bioscience EXOCET Exosome Quantitation Kit was used to quantify the number of EVs released from the hydrogels. For the protein content of the released EVs, the collected samples were lysed using a 5×RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM PMSF. Aliquoted EVs diluted with or without DPBS (1:10) were lysed with an appropriate volume of cold 5× RIPA buffer and incubated on ice for 20 minutes. The lysates were vortexed for 1 minute, sonicated for 1 minute, and incubated on ice for an additional 10 minutes. The samples were then centrifuged at top speed (4°C, 15 minutes), and the supernatant was transferred to new tubes for protein concentration measurement.

The total protein content of the EVs lysates was measured using the micro-BCA protein assay kit (23235; Thermo Fisher Scientific,) with BSA as the standard. To ensure accurate measurements, both undiluted and diluted samples were analyzed, along with a calibration curve prepared according to the assay manual. Release profiles of EVs for all hydrogel formulations were constructed based on this data.

Bioactivity of the released EVs:

To assess the bioactivity, the released EVs were collected and incubated with PC12-TrkB cells. These cells are responsive to certain therapeutic materials (proteins, RNAs or growth factors) and show enhanced neurite outgrowth when in contact with these molecules. Therefore, we used PC12 cells to assess the biological activity of the released EVs. For this purpose PC12 cells were cultured as follows; PC12 cells, derived from a rat pheochromocytoma, are commonly cultured in DMEM or F12K medium supplemented with 7% heat-inactivated horse serum, 7% fetal bovine serum, and antibiotics (50 U/mL penicillin and 50 µg/mL streptomycin). For optimal attachment, cells are seeded on Falcon Primaria dishes or collagen-coated plates, and optionally on coverslip dishes pre-treated with ECL matrix diluted in cold F12K medium and incubated at 37°C for at least one hour. PC12 cells grow in small clusters and should be fed three times per week, replacing only two-thirds of the medium to preserve endogenous growth factors. When clusters become too large (typically >6–8 cells), they should be gently dispersed by pipetting—trypsin is avoided due to cell sensitivity. For passaging, cells are replated at a 1:3 or 1:4 dilution, ensuring they are not overly diluted to maintain viability. For long-term storage, cells are frozen in 90% culture medium with 10% DMSO using a slow-freezing protocol before transfer to liquid nitrogen. To induce neuronal differentiation, collected EVs (3×1010 EVs/mL) added to the medium, prompting neurite outgrowth and cessation of proliferation. Neurite extension was visualized using light microscopy.

Results

Hydrogel & EVs Release Characterization

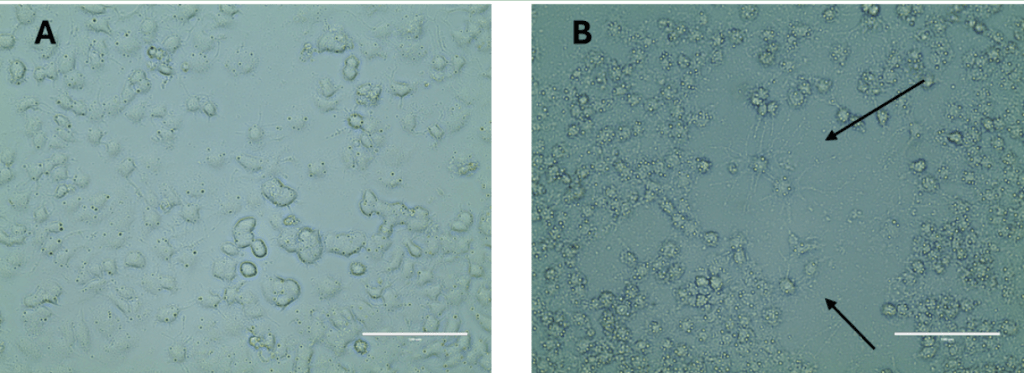

The microstructure of the formed hydrogel was detailly assessed using SEM imaging. It was observed that the hydrogels have porous structures, allowing PBS penetration and the release of the loaded EVs (Figure 2). The presence of EVs did not cause any structural changes due to their small size (50-150 nm). These characteristics demonstrate the added capability of EVs in a drug delivery involving said hydrogels.

In accordance with an established technique, to determine if the collected PBS samples did contain the released EVs from the EVs-hydrogel, ELISA kits were used to detect the EVs markers25. These ELISA tests characterize the release kinetics and characteristics of the EVs. As shown in Figure 3, the isolated EVs expressed all the major EVs markers, CD9, CD63 and CD81 (Figure 3A), indicating the collected EVs are bioactive. The integrity of the released EVs was examined by using EV protein and membrane labeling kits. The protein contents (Figure 3B) of the released EVs prove that the environment they were placed in is suitable for their operational capabilities. The labeling of the membrane (Figure 3C) of the released EVs demonstrates that they are compatible with the hydrogel. Not only are the EVs able to stay healthy, but the release of the desired, beneficial protein content exemplifies a capability to be functional in the hydrogel’s encapsulation environment. Both the EV membrane and protein contents were labeled and shown as green fluorescein to demonstrate that the structure of the released EVs is intact. Additionally, EV yield was validated with System Bioscience EXOCET Exosome Quantitation Kit as 3×1010 number of EVs/mL in addition to ELISA measurements. In general nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) is used to detect the yield and size distribution of the EVs, however, we currently do not have access to NTA to perform this experiment. Because of this reason, we quantified the EVs with the mentioned kits and measured their size and distribution using dynamic light scattering and SEM images. The size of the EVs ranged between 50-150 nm as expected. The purity of the EVs was calculated by determining the free protein content in the final EV solution after the isolation. It is reported as the number of EVs per microgram protein. The purity of our EVs was reported as 2×109 EV particles/µg protein. The released EVs have similar size and shape as of the originally isolated ones (Figure 3D and E) and their size changes between 50-150 nm as expected.

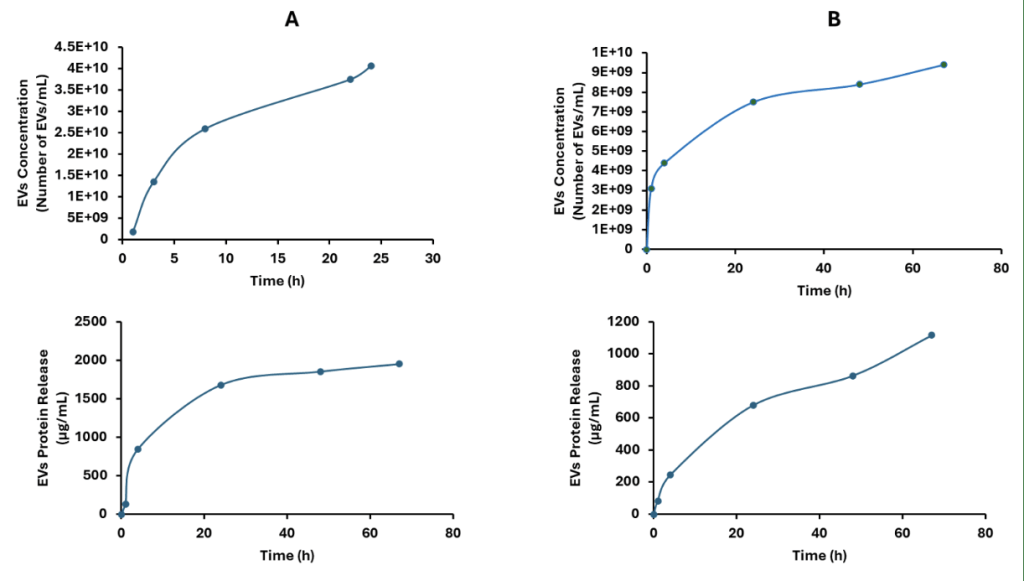

Establishing EVs Release Profile

The released EV concentration and corresponding protein content from the UV-cross-linked hydrogels were shown in Figure 4A. Although there is controlled release the initially loaded EVs amount (~3-3.5×1010 EVs/mL) were released within the first 24 hours. Although this cross-linking mechanism shows ease of application after injection to the injury site, the sustained release was not obtained. On the other hand, EVs loaded (same loading with UV-cross-linked hydrogels (~3-3.5×1010 EVs/mL) and temperature induced gelation of the hydrogels showed extended release compared to UV-cross-linking. This could be attributed to the presence of positively charged PBCs resulting in both gelation and electrostatic complexation with the EVs causing delayed release. With this approach the release time was extended to 67 hours and the hydrogel still contains ~66% of the initially loaded EVs. This indicated that the release of remaining EVs will continue over time. Although the release of the EVs were extended, possibly beyond ~300 hours, these hydrogels systems still need further optimization to obtain sustained release over months. Nevertheless, this initial study indicates the potential of these materials in terms of enabling EVs loading and release.

Therefore, this temperature-induced hydrogel could also be an alternative to UV-cured hydrogel. Moreover, it can also be applied to the injury site, where it gels at body temperature (37 ˚C), the temperature used to induce EVs release, without the need for any open surgery. These beneficial properties support the recent studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of EVs-hydrogel in processes such as wound healing26.

The biological activity of the released hydrogels were also tested on PC12 cells by qualitatively evaluating the neurite extension. The light microscope images in Figure 5 indicated that the PC12 cells treated with the released EVs were observed to demonstrate the neurite outgrowth as compared to the non EVs treated control group without any neurite extension. This evaluation indirectly shows the potential of the EVs as therapeutic tools for future applications related to any disease or injury condition.

In this study, the addition of pentablock copolymer to the hydrogel formulation did not result in irreversible alterations to EV membrane proteins. The cohesiveness of the EV membrane is proven by the fact that the tetraspanin proteins addressed in Figure 3 are abundant. The cohesiveness of the membrane is integral in ensuring the EV can still implement its therapeutic properties. To the extent to which is illustrated by the prevalence of the tetraspanin proteins in Figure 3, it is reasonable to assume the continued presence of the beneficial therapeutic properties of the EVs principal to the positive characteristics of the EV-hydrogel system central to this study.

Discussions and Future Perspectives

This experiment was conducted with the focus of initially assessing the dynamic release of MSC-EVs from EVs encapsulated hydrogel (EVs-hydrogels), which were particularly novel and critical. The EVs-hydrogel, shown in Figure 2, is a solid and fortified structure. It demonstrated that such a hydrogel system was compatible with EVs. This is illustrated in Figures 3 through 5, where hydrogel-content (EVs) release is sustained throughout a relatively extended period depending on the cross-linking type. The effective release of EVs can be seen in Figure 4, with a consistent confluence of EVs in the observation period, and with further gradually increased concentration of EVs when the PLF127-containing pentablock copolymer was added to the hydrogel formulation.

As more materials were included, such as the pentablock copolymer, which had unique electrostatic properties allowing for the EVs to be released slowly, but consistently, our initial release time goals were more closely accomplished. In other words, we not only find out the differential release characteristics of hydrogel when composed of different materials but first demonstrate that a hydrogel made from a responsive pentablock copolymer, instead of only PLF127, can prolong the release process of the EVs from EVs-hydrogel for more than 67 hours with gradually increased concentration (Figure 4). Therefore, the EVs-hydrogel, which used a pentablock copolymer instead of only PLF127, was effective in achieving the initial goals of the study. Critically, the results derived in this study are reflected in recent literature. Cationized hydrogels have been demonstrated to prolong EV release periods27. The absorption of the EVs into the hydrogel structure is more complete in the hydrogels with complementary electrostatic relationships, which relates controlled hydrogel-content release to the effective implementation of electrostatic interactions28. More specifically, more cationic polymer usage within a hydrogel formulation was demonstrated to net a 367% increase in the release period of EVs, from 3 days to 14 days. This is comparable to this study’s demonstration of the prowess of electrostatic relations, netting a minimum of a 1575% increase in the release period of EVs, from around 4 hours to at least 67 hours29.

Although our experimentation demonstrated the possibility of mixing and matching different materials and formulations, it is not always possible to create a concoction of substances that work well together. For example, sometimes it may be necessary to forfeit a certain type of crosslinking to ensure a longer release time. Seen through our first experiment with different PLF127 amounts, specific material compositions yielded improved control over release rates and structural integrity, of which the order of importance can be based on alignment with desired goals. In future experiments, it is important to experiment with these formulaic factors, potentially creating a hydrogel formulation that could be responsive to multiple types of crosslinking, greatly increasing the hydrogel’s use cases. For more resourceful groups, an even longer period could be utilized, to capture an experience as close to the EVs-hydrogel real-life application. Additionally, the usage of corroborative quantification processes may be beneficial in future experiments to validate release numbers such as the ones presented in this study. The preservation of the therapeutic properties of the EVs can be proven through cell-based functional assays. Future studies may also provide a comprehensive purity analysis to ensure that the result measurements are accurate in demonstrating the quantification of the EVs released. Furthermore, because of the potential usage of such EVs-hydrogel in a multitude of situations, especially for clinical application of drug delivery, further studies/considerations will be needed to (1) study how effective the UV crosslinking would be when faced up against different materials may yield interesting results; (2) develop a hydrogel with an even longer releasing period, especially for longer than 15 or even 30 days; (3) test the EVs released from EVs-hydrogel on in vitro cells, and in vivo animal models; (4) examine if the pre-synthesized and injected EVs-hydrogel can specifically reach their target sites, such as injury/insult sites, to exert the desired effects but no off-target effects, which we originally expect. Perfecting these processes can reduce distractions from the entire process by streamlining the initial EVs-hydrogel delivery. Attracting molecules in the EVs involved in injury recoveries like human primary keratinocytes and fibroblasts through the activation of the downstream signaling pathway could provide potential benefits when combined with hydrogel technology for future therapeutic development.

Ultimately, there are serious implications for the continuation of the current system of ineffective drug delivery in many facets of our society. This study provides insight into EVs-Hydrogels as a potential solution and is particularly relevant in advancing scientific knowledge on the effective, concentrated, and prolonged release of MSC-EVs.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted at Cleveland State University in the laboratory of Dr. Metin Uz, with his guidance and assistance for the technical aspects of the project. Metin Uz acknowl-edges support from the National Science Foundation, Division of Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental, and Transport Systems (Award number 2301908).

References

- M. J. Ali, Y. Navalitloha, M. W. Vavra, E. W. Y. Kang, A. C. Itskovich, P. Molnar, R. M. Levy, D. R. Groothuis. Isolation of drug delivery from drug effect: problems of optimizing drug delivery parameters. Neuro-Oncology. Vol. 8, pg. 109-118, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2005-007. [↩] [↩]

- Y. Zhang, L. Tao, S. Li, Y. Wei. Synthesis of multiresponsive and dynamic chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled release of bioactive molecules. Biomacromolecules. Vol. 12, pg. 2894–2901, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1021/bm200423f. [↩] [↩]

- T. Ho, C. Chang, H. Chan, T. Chung, C. Shu, K. Chuang, T. Duh, M. Yang, Y. Tyan. Hydrogels: Properties and applications in biomedicine. Molecules. Vol. 27, pg. 2902, 2022 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092902. [↩] [↩]

- S. Bashir, M. Hina, J. Iqbal, A. H. Rajpar, M. A. Mujtaba, N. A. Alghamdi, S. Wageh, K. Ramesh, S. Ramesh. Fundamental concepts of hydrogels: synthesis, properties, and their applications. Polymers. Vol. 12, pg. 2702, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12112702. [↩]

- B. Huang, J. Qian, J. Ma, Z. Huang, Y. Shen, X. Chen, A. Sun, J. Ge, H. Chen. Myocardial transfection of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells enhance cardiac repair in rats with experimental myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. Vol. 5, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1186/scrt410. [↩]

- E. Folestad, A. Kunath, D. Wågsäter. PDGF-C and PDGF-D signaling in vascular diseases and animal models. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. Vol. 62, pg. 1-11, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2018.01.005. [↩]

- S. J. Zhang, X. Y. Song, M. He, S. B. Yu. Effect of TGF-β1/SDF-1/CXCR4 signal on BM-MSCs homing in rat heart of ischemia/perfusion injury. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. Vol. 20, pg. 899-905, 2016. [↩]

- M. Gnecchi, P. Danieli, G. Malpasso, M. C. Ciuffreda. Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1416, pg. 123-146, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3584-0_7. [↩]

- X. Shi, B. Wang, X. Feng, Y. Xu, K. Lu, M. Sun. circRNAs and exosomes: A mysterious frontier for human cancer. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids. Vol. 19, pg. 384-392, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2019.11.023. [↩]

- E. R. Abels, X. O. Breakefield. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. Vol. 36, pg. 301-312, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-016-0366-z. [↩]

- A. Waldenström, N. Gennebäck, U. Hellman, G. Ronquist. Cardiomyocyte microvesicles contain DNA/RNA and convey biological messages to target cells. PLOS One. Vol. 7,pg. 34653, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034653. [↩]

- D. Dutta, N. Khan, J. Wu, S. M. Jay. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging frontier in spinal cord injury pathobiology and therapy. Trends in Neurosciences. Vol. 44, pg. 492–506, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2021.01.003. [↩]

- Z. Zhang, X. Zhang, C. Wang, W. Teng, H. Xing, F. Wang. E. Yinwang, H. Sun, Y. Wu, C. Yu, X. Chai, Z. Qian, X. Yu, Z. Ye, X. Wang. Enhancement of motor functional recovery using immunomodulatory extracellular vesicles-loaded injectable thermosensitive hydrogel post spinal cord injury. Chemical Engineering Journal. Vol. 433, pg. 134465, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.134465. [↩] [↩]

- C. Wang, M. Wang, K. Xia, J. Wang, F. Cheng, K. Shi, L. Ying, C. Yu, H. Xu, S. Xiao, C. Liang, F. Li, B. Lei, Q. Chen. A bioactive injectable self-healing anti-inflammatory hydrogel with ultralong extracellular vesicles release synergistically enhances motor functional recovery of spinal cord injury. Bioactive Materials. Vol. 6, pg. 2523–2534, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.01.029. [↩] [↩]

- S. Wang, R. Wang, J. Chen, B. Yang, J. Shu, F. Cheng, Y. Tao, K. Shi, C. Wang, J. Wang, K. Xia, Y. Zhang, Q. Chen, C. Liang, J. Tang, F. Li. Controlled extracellular vesicles release from aminoguanidine nanoparticle-loaded polylysine hydrogel for synergistic treatment of spinal cord injury. Journal of Controlled Release. Vol. 363, pg. 27–42, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.09.026. [↩]

- B. Zhang, F. Jia, M. Q. Fleming, S. K. Mallapragada. Injectable self-assembled block copolymers for sustained gene and drug co-delivery: an in vitro study. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. Vol. 427, pg. 88-96, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.018. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- P. S. Garcia, B. S. L. Antunes, D. Komatsu, M. de A. Hausen, C. Dicko, E. A. de R. Duek. Mechanical and rheological properties of Pluronic F127 based-hydrogels loaded with chitosan grafted with hyaluronic acid and propolis, focused to atopic dermatitis treatment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. Vol. 307, pg. 141942, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141942. [↩]

- A. D. Sharma, S. Zbarska, E. M. Petersen, M. E. Marti, S. K. Mallapragada, D. S. Sakaguchi. Oriented growth and transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells towards a schwann cell fate on micropatterned substrates. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. Vol. 121, pg. 325-335, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.07.006. [↩]

- J. Jankovičová, P. Sečová, K. Michalková, J. Antalíková. Tetraspanins, More than markers of extracellular vesicles in reproduction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 21, pg. 7568, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207568. [↩]

- C. N. Munyiri, E. S. Madivoli, J. Kisato, J. Gichuki, P. G. Kareru. Biopolymer based hydrogels: crosslinking strategies and their applications. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials. Vol. 74, pg. 625-640, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/00914037.2024.2356603. [↩]

- A. GhavamiNejad, N. Ashammakhi, X. Y. Wu, A. Khademhosseini. Crosslinking strategies for three-dimensional bioprinting of polymeric hydrogels. Small. Vol. 16, pg. 2002931, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202002931. [↩]

- W. E. Hennink, C. F. van Nostrum. Novel crosslinking methods to design hydrogels. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. Vol. 64, pg. 223-236, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00240-x. [↩]

- B. L. Abraham, E. S. Toriki, N. J. Tucker, B. L. Nilsson. Electrostatic interactions regulate the release of small molecules from supramolecular hydrogels. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. Vol. 8, pg. 6366-6377, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1039/d0tb01157f. [↩]

- M. Uz, S. K. Mallapragada, S. A. Altinkaya. Responsive pentablock copolymers for siRNA delivery. RSC Advances. Vol. 5, pg. 43515–43527, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA06252G. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- K. Man, I. A. Barroso, M. Y. Brunet, B. Peacock, A. S. Federici, D. A. Hoey, S. C. Cox. Controlled release of epigenetically-enhanced extracellular vesicles from a GelMA/nanoclay composite hydrogel to promote bone repair. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 23, pg. 832, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23020832. [↩]

- Y. Yang, H. Chen, Y. Li, J. Liang, F. Huang, L. Wang, H. Miao, H. S. Nanda, J. Wu, X. Peng, Y. Zhou. Hydrogel loaded with extracellular vesicles: an emerging strategy for wound healing. Pharmaceuticals. Vol. 17, pg. 7, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17070923. [↩]

- K. Yoshizaki, H. Nishida, Y. Tabata, J. Jo, I. Nakase, H. Akiyoshi. Controlled release of canine MSC-derived extracellular vesicles by cationized gelatin hydrogels. Regenerative Therapy. Vol. 22, pg. 1-6, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reth.2022.11.009. [↩]

- S. Chen, H. Kao, J. Wun, P. Chou, Z. Chen, S. Chen, S. Hsieh, H. Fang, F. Lin. Thermosensitive hydrogel carrying extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived stem cells promotes peripheral nerve regeneration after microsurgical repair. APL Bioengineering. Vol. 6, pg. 046103, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0118862. [↩]

- S. Chen, H. Kao, J. Wun, P. Chou, Z. Chen, S. Chen, S. Hsieh, H. Fang, F. Lin. Thermosensitive hydrogel carrying extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived stem cells promotes peripheral nerve regeneration after microsurgical repair. APL Bioengineering. Vol. 6, pg. 046103, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.011886. [↩]