Abstract

Since 2000, the prevalence of autism in the United States has risen from approximately 1 in 150 children to 1 in 36, highlighting a growing need for preventive interventions in fetal medicine. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent difficulties in social communication, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors, typically emerging before the age of three and sometimes occurring with intellectual impairment (American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5). In response to this increasing prevalence, researchers have turned greater attention to maternal behaviors during pregnancy that may impact fetal brain development and elevate the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD. This literature review examines the effects of adverse maternal behavior, specifically smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use, during pregnancy on gestational brain development. The review includes 21 peer-reviewed clinical studies published between 2005 and 2022 that met defined inclusion criteria: assessment of prenatal exposure to substances through self-reported surveys or through clinical interventions (e.g., imaging scans) that documented behavioral or neurological outcome data related to ASD or neurodevelopment. Results indicate that negative maternal behaviors during early pregnancy are associated with neurodevelopmental delays and increased ASD. The review emphasizes the importance of early clinical screening, counseling, and patient education to reduce substance use during pregnancy. Furthermore, it highlights the need for future research to address socioeconomic and environmental factors, as some studies have noted their influence on maternal health behaviors and outcomes among vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Maternal behaviors, pregnancy, fetal brain development, Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), Neurodevelopmental disorders, prenatal exposure, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol consumption, recreational drug use, prenatal risk factors, preventive strategies

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents significant challenges for affected children and their families, often leading to difficulties in social interaction, communication, and daily functioning1. ASD imposes an economic burden, with lifetime costs in the United States estimated to exceed $2 million per individual2. Caregivers frequently experience emotional and financial strain due to the intensive support many children require3. Understanding factors associated with ASD development is, therefore, critical. Emerging research suggests that prenatal exposures to maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use may impact fetal neurological development and increase susceptibility to neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD. Fetal brain development is highly susceptible to influence by both biological and environmental conditions. Maternal stress, poor nutrition, and exposure to toxins can interfere with normal neural growth4. In parallel, adverse social environments, such as domestic violence, isolation, or limited prenatal care, can indirectly compound these risks, increase chronic stress, and disrupt protective social supports4. In a deeper review of clinical research studies examining substance use during pregnancy, researchers have identified correlations between prenatal exposure and increased risk of delayed neurological development. For example, prenatal alcohol exposure has been linked to a 52% increase in risk of neurodevelopmental disorders5. In addition, maternal cannabis use has been associated with a twofold increase in the likelihood of autism diagnosis in offspring. However, most of these findings are correlational rather than causal, and underlying mechanisms remain under investigation. Studies have noted that the first trimester represents an acute period in fetal brain formation, and exposure during this period of development increasingly disrupts neuronal differentiation and connectivity6. Alcohol, nicotine, and recreational drugs may impair cognitive and behavioral outcomes by altering central nervous system development and oxygen supply to the fetus6. Exposure to drugs and addictive substances during embryonic development has the potential to significantly alter the cellular morphology of cortical neurons in the brain6. Prenatal alcohol exposure has been associated with deficits in cognitive and behavioral functioning and is frequently identified as a contributing factor in autism risk7. Smoking can double the mother’s risk of abnormal bleeding during pregnancy and delivery, and not only does it hurt the mother, but it also hurts the baby5. Smoking may reduce oxygen supply to the fetus5. potentially affecting brain development8. Disruptions can contribute to later neurological and behavioral challenges, with varying degrees of impact depending on exposure type, timing, and duration5.

Although attention on ASD continues to grow, there remains a lack of public understanding and heightened clinical awareness of the associated neurological risks when maternal substance use occurs during pregnancy. Research tends to focus on isolated exposures, overlooking the cumulative effects of alcohol, nicotine, and drugs within real-world contexts. By addressing this gap, it will provide more evidence-based awareness, inform public health strategies, and strengthen early intervention approaches that protect fetal neurological development and reduce the risk of ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

ASD is a neurological and developmental condition that affects how individuals interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave9. Individuals with autism often exhibit challenges in social communication and behavior, such as difficulty understanding social cues, limited expressions of empathy, repetitive actions, strict adherence to routines, and intense, focused interests9. In individuals with autism, neuroimaging studies have shown that the hippocampus is often enlarged, while the amygdala may be reduced in size, particularly in early childhood.

Early Brain Formation and the Consequences of Maternal Substance Use

Understanding the brain’s development throughout pregnancy is critical to explaining how negative social behaviors may contribute to neurological developmental delays. According to Chung et al. (2010), risky or harmful social behaviors during pregnancy, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use, can adversely affect both the mother and her child10. They note that substance use among women of childbearing age not only impacts the women directly11 but also has significant consequences for fetal development and postnatal outcomes12.

Exposure to alcohol or illicit drugs in utero is associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including congenital defects11, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, preterm birth, cognitive impairments, and behavioral problems12. The importance of avoiding such negative social behaviors is not limited to pregnancy alone; it extends into the preconception period, as crucial stages of brain development begin immediately following fertilization. Diav-Citrin et al. (2013) explain that the central nervous system (CNS) originates from a dorsal thickening of the ectoderm known as the neural plate, which emerges during the third week after fertilization4. This neural plate folds to form a neural groove, which then develops into the neural tube during the fourth week of development. The neural tube subsequently gives rise to the brain4, including the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain11. Figure 1 outlines the development of the fetal brain throughout the course of pregnancy, while Prayer et al. outlines the following for critical brain development milestones 13.

- Supratentorial cortical development – Primitive cerebral hemispheres can be detected as early as 3 weeks after conception14.

- Temporal lobe development – during the 9th week, the hippocampal primordial can be identified by its position on the medial aspect of the developing cerebral hemisphere. This structure consists of four primary zones: ventricular, intermediate, hippocampal, and marginal zone14.

- Amygdala – Neurons that form the amygdaloid complex are among the earliest to mature in the primate brain. These neurons originate primarily from the ganglionic eminence and migrate toward the amygdaloid nucleus. Around 12 weeks of gestation, they appear as radially oriented clusters in the lateral amygdaloid nucleus, a pattern that continues until 24 weeks. After this point, the basolateral nuclei begin to mature and reorganize, marking a transition in the amygdala’s structural development14.

- Cerebellum – The first stage of cerebellar development begins around the 5th week of gestation, marked by the formation of the cerebellar territory from the hindbrain. During this stage, the cerebellum forms the right and left hemispheres, laying the foundation for later structural development14.

As outlined above, a significant amount of brain development occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy. As noted by Aydin et al. (2024), one of the earliest structures to develop is the cerebellum15. It emerges from the roof of the rhombencephalon between 4 and 6 weeks of the young fetus’s life, which places it at increased vulnerability to a range of developmental effects during prenatal development15. Therefore, the social behaviors of females during this period will significantly impact neurological outcomes, and negative behaviors will likely increase the risk of developing neurological disorders. Understanding the brain’s development throughout pregnancy acknowledges how prenatal behaviors could lead to brain damage or injury.

There are various theories about the genetic transmission of neurological disorders compared to brain injuries resulting from prenatal care, which includes medical, social, or environmental influences. One of those disorders that is highly researched and deliberated is autism. Previc (2006) emphasizes the importance of examining genetic information related to fetal brain development and corresponding placental findings in conjunction with prenatal factors, such as environmental and negative social behaviors, when investigating the presence of neurological brain disorders in fetuses16. Previc (2006) indicated this was especially true in behaviors and disorders when the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) alterations occur, becoming a critical role in the development of disorders such as autism16. This risk increases when dopamine (DA) systems are ill-protected from negative prenatal influences16. Dopamine is involved in motor rather than sensory behaviors; a critically involved neurotransmitter such as DA appears in what is referred to as directorial intelligence, which includes similar components as working memory and cognitive shifting and is highly related to fluid/general understanding16. Therefore, impacts that increase dopamine will likely push more dopamine to the left hemisphere, which is a more defined function than the right hemisphere, increasing the risk of autism17. He continues this evidence by highlighting that relying more on serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) transmission is more in the right-hemispheric type activity, is relatively deficient in autism, thereby shifting the neurochemical balance even more toward the DA-rich left hemisphere16. McCarty et al. (2007) also note the importance of dopamine in brain development by noting the impact of dopamine’s role in cell proliferation and differentiation, associating the likelihood that transient imbalance in dopamine levels in the developing brain could translate into lasting impairments of the structure and function of the mature brain18. McCarthy et al. suggest that dopamine imbalance can occur when maternal intake of drugs such as cocaine can cross the placental barrier and interfere with dopaminergic signaling mechanisms in the fetal brain18. McCarthy et al. also correlate the relationship of neuro-functional disorders such as schizophrenia, ASD, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with an imbalance in dopamine18. Several factors can influence the level of dopamine developed during pregnancy. According to Previc (2006), dopaminergic systems in humans are highly susceptible to a myriad of prenatal influences; these are based on both direct and indirect manipulations of maternal DA levels during pregnancy16. These factors include prenatal stress, high temperatures, pharmacological interventions, negative social behaviors (smoking, alcohol, drugs), pollution, and other factors. This analysis will focus on the negative social behaviors of smoking, alcohol, and drugs, impacting the risk of having an autistic child.

Methodology

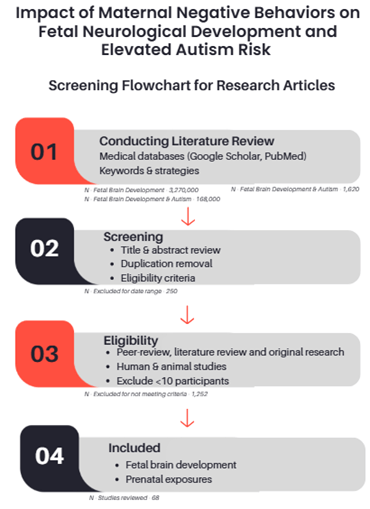

Conducting Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review was conducted, primarily utilizing medical article databases such as Google Scholar and PubMed. The keyword development followed a three-step approach: step one focused on fetal brain development; step two incorporated negative social behaviors during pregnancy; and step three combined both sets to identify studies linking prenatal exposures to neurological development outcomes. Using the Boolean operators, combinations included: step one – “fetal brain development”, step two – AND (“autism” OR “ASD”), step three AND (“smoking” OR “alcohol” OR “recreational drugs”). Additionally, epidemiological and prevalence studies on autism were reviewed to support the exposure-related findings. Documented each search for reproducibility and recorded all search combinations and strategies. Articles were limited to a date range of 2005 through 2025, as a mechanism to provide more appropriate and recent evidence-based reviews. Article research was conducted between August 2024 and March 2025.

Criteria

Prioritization of articles with higher citation counts and establishing a goal to analyze 15-20 articles per keyword topic. However, more recent publications received higher priority, providing evidence-based outcomes that aligned with the literature review. These publications, ranging from neurological and psychological journals to psychological medicine and socioeconomic publications, increased accuracy in the assessment. Collected information regarding prenatal health outcomes from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) and quantitative data from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additionally, examined socioeconomic data available on published websites such as the March of Dimes. The analysis did not review preprints due to a lack of access. The selected studies included peer-reviewed and original research. They covered fetal brain development and the effects of prenatal exposure to negative social behaviors. Research reviews included both human and animal studies and consisted of case reports that either surveyed participants or conducted clinical treatments to assess the neuroglial development of the fetus. Studies with fewer than 10 participants or non-peer-reviewed reports were excluded. The search included studies conducted in the United States and globally, provided that an English translation was available. Non-English articles were excluded. However, European studies had to include peer-review notations and be published in a notable medical journal.

Screening Process

Initial screening began with title confirmation regarding the article’s relevance to the subject, followed by an abstract preview. Plausible studies underwent a thorough review to assess their significance to fetal neurological development and prenatal exposures. The student removed duplicate records and consolidated overlapping studies for comparison and understanding of outcomes and data presentation. Excluded studies were documented with respective reasoning. To ensure the article met the appropriate criteria, the selection utilized the PRISMA guidelines and documented each article’s assessment. The PRISMA approach ensured the transparency and reproducibility of study selection. Figure 2 outlines the PRIMA flowchart utilized for this assessment. Since the articles included both clinical treatments documenting neurological development and survey data from participants interviewed about their prenatal behaviors, the use of JBI tools facilitated the evaluation of the study, reduced the risk of bias, and ensured the overall quality of both quantitative and qualitative outcomes. To ensure methodological rigor, the student assessed all studies for quality, evaluating the coherence, reliability, and overall validity of the research reported in the articles.

| Concept | Keywords/Terms |

| Brain Development | Fetal brain development, brain development during pregnancy, infant brain development |

| Autism | Autism, Autism developing during pregnancy, Autism during pregnancy due to smoking, and/or alcohol, and/or recreational drugs |

| Neurological Disorders | Neurological disorders development during pregnancy, Neurological disorders as a result of negative social behaviors, neurological disorders and Autism in fetal development |

| Negative Social Behaviors | Negative social behaviors during pregnancy, impacts of alcohol on fetal brain development, impacts of smoking on fetal brain development, impacts of recreational drugs, definition of negative social behaviors |

Results

Smoking

Epidemiology

Research continues to show increasing evidence of a link between maternal smoking and heightened risk of autism. Maternal smoking during pregnancy has been associated with alterations in fetal neurodevelopment, including potential increases in risk for neuropsychiatric outcomes such as ADHD, schizophrenia, OCD, and ASD19. Epidemiological evidence is mixed, with some studies reporting strong associations with prenatal smoking exposure and increased risks of neurological disorder development, and others observing weak or no consistent links. This variability may be due to differences in study design, population characteristics, and methods of exposure assessment19. Maternal smoking during pregnancy has been associated with increased risk of social communication deficits and repetitive behaviors in offspring20; however, confounding and familial factors limit conclusions about causality20. This is demonstrated in research by Quinn et al. (2017), which notes a modest association between maternal smoking and ASD, with pooled odds ratios around 1.02 (95% CI: 0.93–1.13), indicating a slight increase in risk21.

Mechanisms

Exposure to nicotine and other harmful chemicals in cigarette smoke can disrupt fetal brain development by inducing oxidative stress, altering neurotransmitter systems, and interfering with normal neuronal growth and connectivity19. According to Wells and Lotfipour (2023), cigarette smoke is composed of a complex array of chemical constituents, including products such as carboxylic acids, phenols, water, humectants, terpenoids, paraffin waxes, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs), and catechols. When nicotine is absorbed into the pulmonary venous circulation, it binds to neuronal nAChRs that mediate fast neurotransmission in the central and peripheral nervous system8. These alterations may contribute to atypical neurodevelopmental pathways associated with ASD. This binding then signals the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate8. Gestational nicotine exposure has been associated with decreased cells within the brain and reduced brain volume in the frontal lobe and cerebellum8. This reduction in radial thickness may also affect dopamine released22; in the frontal cortex23.

Alcohol

Epidemiology

With a significant amount of brain development occurring in the first few weeks of conception, most women do not realize they are pregnant and, therefore, are less likely to adjust their lifestyle, which could include drinking alcohol. According to Carpita et al. (2022), fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) are a category of conditions correlated with the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and characterized by several kinds of impairments: distinctive facial characteristics palpebral fissures [the horizontal openings between the eyelids], a smooth philtrum [the flat area between the nose and upper lip that usually has vertical grooves], a thin upper vermilion border [a thinner-than-normal upper lip line], and maxillary hypoplasia [underdevelopment of the upper jawbone]7; cardiac defects, and growth retardation20. Epidemiological studies indicate how alcohol easily crosses the placenta and distributes rapidly into the fetus, including the amniotic fluid [the protective liquid surrounding the baby within the womb that cushions and nourishes the developing fetus], which prolongs the fetus’s exposure to it. Prenatal alcohol exposure is linked to reductions in overall brain volume and alterations in gray and white matter in the cerebrum, as well as changes in cerebral cortex thickness, which has been associated with cognitive performance delays24. Chronic and heavy alcohol use during pregnancy25; has been associated with impairing folate transport26; to the fetus, potentially increasing the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs)27. Johns Hopkins highlights that adequate folic acid during pregnancy is crucial to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs)—birth defects affecting the brain, skull, and spinal cord (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020)27.

Mechanisms

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy has been linked to alterations in the regulation of gene expression, particularly in genes involved in neurodevelopment such as BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), SHH (Sonic Hedgehog), and FGF (fibroblast growth factors), which play critical roles in brain growth, cell differentiation, and neural connectivity7. These molecular disruptions have been associated with abnormal neuronal proliferation, migration, and synapse formation, which in turn are related to impairments in memory, attention, executive function, and social behaviors in the offspring28. Reduced folate availability, exacerbated by alcohol and other substances, has been associated with altered neurodevelopment and observed FASD25. This was confirmed by Carpita et al. (2022), who noted altered folate levels in clinical trials of infants with FASD and autism7. In addition, research has observed that the deregulation of dopamine systems because of alcohol intake during pregnancy is more frequently observed in children with autism7.

Recreational Drugs

Epidemiology

Recreational drugs can be defined in many ways. The definition that BMJ gives is that there are four categories of recreational drugs: analgesics, depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens29. The category of analgesics most associated with impacts on brain development includes narcotics such as heroin, morphine, fentanyl, and codeine30. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 3–7% of pregnant women in the USA use marijuana during pregnancy31. The criticality of recreational drug use during pregnancy is due to the large impact it has on three fundamental aspects of brain development: cellular and molecular mutation; size, structure, and connectivity within the CNS; and altered behavior and cognition that have been associated with drug exposure32.

Fetal cocaine and heroin exposure are also notable. Cocaine exposure during pregnancy has been associated with fetal growth retardation, seizures, respiratory distress, cerebral malformation, and, in some cases, sudden infant death syndrome33. Data suggest that approximately 0.2% to 4.3% of pregnancies in the U.S. involve cocaine use34; however, effect sizes for associated deficits are not consistently reported, which may relate to understated potential risks with prenatal cocaine exposure23. Heroin-dependent parents and their children have been observed with a high incidence of hyperactivity, inattention, and behavioral problems6. Estimates suggest that prenatal exposure to opioids, including heroin, ranges from less than 1% to 21%; however, like cocaine, effect size is not consistently reported23.

Mechanism

Sajdeya et al. indicate that the psychoactive constituent of cannabis is Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)31. This substance can cross the placenta and the fetal blood-brain barrier, which have been associated with disruptions in endogenous cannabinoid signaling during embryonic neurodevelopment31. The significance of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol crossing the barrier is due to observed gene-specific neural changes and alterations in neuronal wiring. In one study, these disruptions were linked to an increased likelihood of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) traits, with an estimated effect size of approximately 50% in the sample studied; however, confidence intervals and sample sizes varied, and further research is needed to confirm these findings across larger populations5. Reported effect sizes range from 30% to 50%35, with prevalence estimates of prenatal THC exposure varying between 3% and 7% in the United States. Including such quantitative estimates provides a clearer picture of the magnitude and scope of risk36. Cannabis use during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of fetal low birth weight, which is considered an indirect risk factor for ASD due to its relationship with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes31. This has also been related to abnormal cellular processing and neurocircuitry during development33.

Studies have indicated associations between fetal exposure to Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis, may relate to decreased gene expression of dopamine receptors in both the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the amygdala33. This reduction in gene expression suggests that the developing brain may produce fewer dopamine receptors or receptors with impaired functionality, which has been linked to changes in brain regions involved in emotion regulation, impulse control, and reward processing. These disruptions may relate to difficulties in emotional regulation, behavioral issues such as poor impulse control, and cognitive impairments32, including learning and memory deficits33. Notably, these neurodevelopmental challenges are commonly observed with the symptom profile of ASD.

Fetal cocaine exposure during pregnancy has been associated with altered brain monoamines, especially dopamine, during a critical stage of brain development37. Research suggests that cocaine interferes with brain development through the perturbation of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate37 Cocaine exposure during pregnancy has been linked to inducing structural alterations in key brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens37. Children with prenatal cocaine exposure frequently exhibit specific language and cognitive deficits9, behavioral problems, and altered social development37.

Heroin is a semisynthetic opioid derived from morphine and is classified as an illicit drug with no accepted medical use in most countries, including the United States6. It is primarily associated with recreational use and has a high potential for abuse and addiction6. The long-term consequences of prenatal heroin exposure in developing humans are still not fully understood6. Heroin and other opioids act through opioid receptors38, which are protein structures found in the brain and spinal cord6.This mediation has been associated with altered responses by neurotransmitters, impacting behavioral and cognitive function6. A research study that examined MRI scans of adolescents whose mothers used heroin during pregnancy showed an association with those teens having smaller brain formation in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, pallidum, and thalamus32. These altered brain formations have been linked to increase risk for autism and other developmental issues4.

Discussion

Effects of Maternal Substance Use

The purpose of the research assessment was to elucidate the correlation between the elevated risk of developing autism and fetal exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs during pregnancy. This review highlighted the critical period of brain development in the first trimester, specifically from weeks 1 to 10, during which many women may be unaware of their pregnancy39. Extensive studies have shown that exposure to harmful substances during this crucial developmental window can significantly disrupt the formation of typical brain structures, including key areas such as the cerebral cortex40. These disruptions can lead to atypical cell proliferation and impaired neuronal signaling, ultimately increasing the risk of behavioral and cognitive dysfunctions, including ASD.

Comparing Across Substances

Individual studies reported variable sizes, common patterns occurred: nicotine exposure has been associated with modest increases in ASD risk (pooled OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93–1.13)21 prenatal alcohol exposure correlates with structural and functional brain changes, and cannabis exposure has been linked to up to a 50% increase in likelihood of ASD in some studies (single-cohort study of 312 pregnancies; 95% CI: 1.10–2.25)31. Findings suggest similar outcomes that include changes in dopaminergic signaling, neurotransmitter imbalance, oxidative stress, and impaired synaptogenesis.

- Smoking primarily affects oxygen delivery and neurotransmitter signaling, leading to reduced frontal lobe and cerebellar volume8.

- Alcohol disrupts gene expression (BDNF, SHH, FGF), neuronal migration, and folate-dependent neurodevelopment, with FASD-like features observed in offspring7.

- Recreational drugs such as cannabis, cocaine, and heroin demonstrate varied effects on dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, structural brain maturation, and behavioral outcomes31.

Socioeconomic and Environmental Influences

Socioeconomic status (SES) significantly shapes maternal behaviors and access to prenatal care. Typically, lower SES is associated with increased rates of negative social behaviors and reduced healthcare access25. Environmental stressors, including domestic violence or limited social support, further deepen risks. Combining SES and environmental context is essential to accurately interpret substance-related neurodevelopmental risks. Babies born to mothers who have used drugs during pregnancy may be more likely to experience lifelong challenges, including learning and behavioral difficulties, and have been observed to show a higher prevalence of conditions such as autism. However, discontinuing drug use is not always an option. If a mother is taking heroin or opioids, they cannot just stop using them; this could harm the baby. Medications such as methadone or buprenorphine can help reduce the addiction to opioids without the same risks, according to March of Dimes/Healthy Moms Strong Babies.

The mothers’ socioeconomic status (SES) is another critical aspect of these investigations. A comprehensive understanding of how socioeconomic factors influence access to fetal medicine, health literacy, and preventive healthcare measures is vital. Identifying and addressing the barriers faced by women from lower SES backgrounds could significantly enhance prenatal care access and quality. Certain habits and behaviors could also be associated with the SES of the mother. For example, mothers from lower SES backgrounds are more likely to use tobacco, which could skew the actual relationship between developing autism and smoking9. One of the inherent challenges in these studies is accurately pinpointing the timing and frequency of substance use throughout the pregnancy. Some studies noted limitations in examining the fetus throughout the pregnancy, limiting complete outcome assessments. Additionally, understanding how socioeconomic factors influence fetal medicine, particularly in relation to preventive measures, health literacy, and access to prenatal care, is crucial for addressing disparities.

Paternal Substance Use, and Other Considerations

Although this review concentrates on maternal exposures, paternal substance use and genetic liability may also contribute to offspring neurodevelopment. Shared family genetics can influence vulnerability to ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Studies suggest that paternal smoking, alcohol, or drug use can indirectly influence fetal development5. Future analyses should consider both maternal and paternal factors.

Limitations Considerations:

Several articles reviewed in this assessment noted that the data were primarily derived from patient surveys, which raises concerns about recall bias and the accuracy of self-reported information. Such issues are compounded by potential selection bias and the societal stigma surrounding substance use during pregnancy. This may result in underreporting or inaccuracies in the data, as women may hesitate to disclose their smoking, alcohol consumption, or recreational drug use due to fear of judgment. Recreational drug use assessments, in particular, present significant challenges in obtaining accurate information, as socioeconomic factors and biases inherent in this population can influence research findings5. Disclosure of actual drug use and types could have been affected by concerns mothers had about revealing their behaviors during pregnancy9.

Conclusion

Understanding how adverse social conditions, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use, affect fetal brain development can offer valuable insights into the long-term implications for both individuals and society. Alcohol and smoking showed consistent associations with disorders in brain development that included alterations in neuronal growth and synapse formation. These alterations are related to difficulties in attention, memory, executive function, and social behavior, observed in traits of ASD. However, evidence for recreational drug exposure is more limited, likely due to the stigma and limited awareness of health interventions; those studies available observed impacts on fetal brain growth and early neurobehavioral outcomes.

However, the review acknowledges several limitations. Most studies were observational, which limits causal conclusions, and confounding factors such as parental mental health, genetics, socioeconomic status, and co-exposures could influence outcomes. Current evidence does not support a direct causal link between prenatal alcohol exposure and ASD, though overlapping outcomes with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) exist. Paternal substance use and broader environmental factors may also play a role, indicating a need for studies that examine both maternal and paternal contributions.

This review adds to the existing literature by synthesizing the effects of maternal prenatal behaviors on neurodevelopment while highlighting research gaps, including paternal exposures, gene-environment interactions, and underrepresented populations. Additional studies should focus on domestic and environmental factors and include diverse populations. However, findings support increased prenatal counseling, substance use screening, and early developmental monitoring. Public health efforts and policy interventions should target support for pregnant individuals facing social stressors to reduce neurodevelopmental risk. By highlighting the influence of these conditions, this study seeks to advocate for stronger societal support and policy initiatives aimed at reducing risk. Ultimately, the goal is to explore the complex relationships between social behaviors, maternal health, and child development to support healthier outcomes for future generations.

References

- Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G., & Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. The Lancet, 392(10146), 508–520 (2020). [↩]

- Buescher, A. V. S., Cidav, Z., Knapp, M., & Mandell, D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 721–728 (2014). [↩]

- Kogan, M. D., Blumberg, S. J., Schieve, L. A., et al. (2008). Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1395–1403 (2008). [↩]

- Diav-Citrin, O. (2013). Prenatal exposures associated with neurodevelopmental delay and disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 17(2), 71–84 (2013). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Costa, A. A., Almeida, M. T. C., Maia, F. A., Rezende, L. F., Saeger, V. S. A., Oliveira, S. L. N., Mangabeira, G. L., & Silveira, M. F. Maternal and paternal licit and illicit drug use, smoking and drinking and autism spectrum disorder. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 29(2) (2024). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Etemadi-Aleagha, A., & Akhgari, M. (2022). Psychotropic drug abuse in pregnancy and its impact on child neurodevelopment: A review. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 11(1), 1–13 (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Carpita, B., Migli, L., Chiarantini, I., Battaglini, S., Montalbano, C., Carmassi, C., Cremone, I. M., & Dell’Osso, L. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Literature Review. Brain Sciences, 12(6), 792 (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Wells, A. C., & Lotfipour, S. Prenatal nicotine exposure during pregnancy results in adverse neurodevelopmental alterations and neurobehavioral deficits. Advances in Drug and Alcohol Research, 3, 11628 (2023). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Saunders, A., Woodland, J., & Gander, S. A comparison of prenatal exposures in children with and without a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Cureus, 11(7), e5223 (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Chung, E. K., Nurmohamed, L., Mathew, L., Elo, I. T., Coyne, J. C., & Culhane, J. F. Risky health behaviors among mothers-to-be: The impact of adverse childhood experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 10(4), 245–251 (2010). [↩]

- De Asis-Cruz, J., Andescavage, N., & Limperopoulos, C. Adverse prenatal exposures and fetal brain development: Insights from advanced fetal magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(5), 480–490 (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Chung, E. K., Nurmohamed, L., Mathew, L., Elo, I. T., Coyne, J. C., & Culhane, J. F. Risky health behaviors among mothers-to-be: The impact of adverse childhood experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 10(4), 245–251 (2010). [↩] [↩]

- Prayer, D., Kasprian, G., Krampl, E., Ulm, B., Witzani, L., Prayer, L., & Brugger, P. C. MRI of normal fetal brain development. European Journal of Radiology, 57(2), 199–216 (2006). [↩]

- Prayer, D., Kasprian, G., Krampl, E., Ulm, B., Witzani, L., Prayer, L., & Brugger, P. C. MRI of normal fetal brain development. European Journal of Radiology, 57(2), 199–216 (2006). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Aydin, E., Tsompanidis, A., Chaplin, D., Hawkes, R., Allison, C., Hackett, G., Austin, T., Padaigaitė, E., Gabis, L. V., Sucking, J., Holt, R., & Baron-Cohen, S. Fetal brain growth and infant autistic traits. Molecular Autism, 15(1), 11 (2024). [↩] [↩]

- Previc, F. H. Prenatal influences on brain dopamine and their relevance to the rising incidence of autism. Medical Hypotheses, 68(1), 46–60 (2007). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Previc, F. H. Prenatal influences on brain dopamine and their relevance to the rising incidence of autism. Medical Hypotheses, 68(1), 46–60 (2007). [↩]

- McCarthy, D., Lueras, P., & Bhide, P. G. Elevated dopamine levels during gestation produce region-specific decreases in neurogenesis and subtle deficits in neuronal numbers. Brain Research, 1182, 11–25 (2007). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Semick, S. A., Collado-Torres, L., Markunas, C. A., Shin, J. H., Deep-Soboslay, A., Tao, R., Huestis, M. A., Bierut, L. J., Maher, B. S., Johnson, E. O., Hyde, T. M., Weinberger, D. R., Hancock, D. B., Kleinman, J. E., & Jaffe, A. E. Developmental effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the human frontal cortex transcriptome. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(12), 3267–3277 (2020). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Popova, S., Dozet, D., Shield, K., Rehm, J., & Burd, L. Alcohol’s impact on the fetus. Nutrients, 13(10), 3452 (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Quinn, P. D., Rickert, M. E., Weibull, C. E., V Johansson, A. L., Lichtenstein, P., Almqvist, C., Larsson, H., & Iliadou, A. N. Association Between Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Severe Mental Illness in Offspring. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(6), 589. (2017). [↩] [↩]

- Bublitz, M. H., & Stroud, L. R. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Offspring Brain Structure and Function: Review and Agenda for Future Research. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14(4), (2011). [↩]

- Martin, M. M., McCarthy, D. M., Schatschneider, C., Trupiano, M. X., Jones, S. K., Kalluri, A., & Bhide, P. G. Effects of Developmental Nicotine Exposure on Frontal Cortical GABA-to-Non-GABA Neuron Ratio and Novelty-Seeking Behavior. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY), 30(3), 1830 (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Svetlana, P., Lebel, C., & Andrew, G. Prenatal alcohol exposure and brain structure: A review of MRI studies. NeuroImage: Clinical, 30, 102620 (2021). [↩]

- Hutson, J. R., Stade, B., Lehotay, D. C., Collier, C. P., & Kapur, B. M. Folic acid transport to the human fetus is decreased in pregnancies with chronic alcohol exposure. PloS One, 7(5), e38057 (2012). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Miller, J. L., Rasmussen, S. A., & Honein, M. A. Substance use and nutrition during pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health, 109(9), 1226–1231 (2019). [↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Folic acid. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/index.html (2020). [↩] [↩]

- Mattson, S. N., Bernes, G. A., & Doyle, L. R. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(6), 1046 (2019). [↩]

- Mann, H. What are recreational drugs? The BMJ, 353, i2775 (2016). [↩]

- Volpe, J. J. Neurology of the newborn (6th ed.). Elsevier (2018). [↩]

- Sajdeya, R., Brown, J. D., & Goodin, A. J. Perinatal cannabis exposures and autism spectrum disorders. Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids, 4(1), 67–71 (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Boggess, T., & Risher, W. C. Clinical and basic research investigations into the long-term effects of prenatal opioid exposure on brain development. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 100(1), 396–409 (2022). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Bara, A., Ferland, J., Rompala, G., Szutorisz, H., & Hurd, Y. L. Cannabis and synaptic reprogramming of the developing brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(7), 423–438 (2021). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Chiandetti, A., Hernandez, G., Mercadal-Hally, M., Alvarez, A., Andreu-Fernandez, V., Navarro-Tapia, E., Bastons-Compta, A., & Garcia-Algar, O.Prevalence of prenatal exposure to substances of abuse: Questionnaire versus biomarkers. Reproductive Health, 14, 137 (2017). [↩]

- Tadesse, Abay Woday, et al. “Prenatal Cannabis Use and the Risk of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 171, pp. 142–151 (2024). [↩]

- Young-Wolff KC, Slama NE, Avalos LA, et al. Cannabis Use During Early Pregnancy Following Recreational Cannabis Legalization. JAMA Health Forum. 5(11):e243656. (2024). [↩]

- Davis, J. L., Kennedy, C., McMahon, C. L., Keegan, L., Clerkin, S., Treacy, N. J., Hoban, A. E., Kelly, Y., Brougham, D. F., Crean, J., & Murphy, K. J. Cocaine perturbs neurodevelopment and increases neuroinflammation in a prenatal cerebral organoid model. Translational Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–14 (2025). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Dhaliwal, A., & Gupta, M. Physiology, Opioid Receptor. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546642/ (2025). [↩]

- Etemadi-Aleagha, A., & Akhgari, M. (2022). Psychotropic drug abuse in pregnancy and its impact on child neurodevelopment: A review. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 11(1), 1–13 (2022). [↩]

- Etemadi-Aleagha, A., & Akhgari, M. (2022). Psychotropic drug abuse in pregnancy and its impact on child neurodevelopment: A review. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 11(1), 1–13 (2022). [↩]