Abstract

Machine learning models are susceptible to adversarial attacks — these involve adding an imperceptible perturbation to an input which causes the model to produce an incorrect output. To protect the integrity of machine learning algorithms, like neural networks, that are starting to become more popular in critical fields such as healthcare and autonomous driving, this problem needs to be solved. In this paper, we analyse why adversarial robustness is important and hence explore through experimentation whether the addition of synthetic data, i.e. data generated by diffusion models, to the training set of supervised learning models can improve adversarial robustness and generalization and if so, by how much. To accomplish this, this paper utilizes the MNIST and Stanford Cars datasets, EfficientNet-B0 and ResNet-50 pretrained models and their default weights on PyTorch and the StableDiffusionImg2Img from Hugging Face.

Keywords: Adversarial robustness, neural networks, adversarial attacks, synthetic data, diffusion models, machine learning

Introduction

With the increasing popularity of artificial intelligence algorithms in various industrial settings like healthcare, autonomous driving, financial fraud detection, etc, the integrity of these models is critical to ensure safety of users who stand to reap their benefits. Hence, it is important to ensure that these models perform generalize well to increase robustness and overcome data related hurdles. This paper focuses particularly on adversarial attacks, specifically FGSM (to be explained further), and a possible solution to overcome this problem.

Adversarial attacks are targeted attacks that aim to exploit vulnerabilities in machine learning models. These attacks make use of adversarial examples to purposefully make non-robust, or standard, models misclassify, i.e. produce an incorrect output for a certain input. Although the changes introduced by adversarial attacks are imperceptible to the human eye, they can adversely affect performance. This can become dangerous in some real-life scenarios.

For example, an autonomous vehicle could misinterpret a stop sign due to vandalism, failing to stop correctly and potentially endangering the user. Additionally, perturbed inputs in transaction amounts and timings may deter a financial fraud detection model into falsely classifying a legitimate transaction. Further, biometric security models could provide access to a malicious adversary with altered biometric data, like makeup or Deepfake inputs for facial recognition. More information on adversarial attacks on biometric authentication systems can be found in Park et al.’s paper1. Other vulnerable fields include cybersecurity, robotics, e-commerce, and forensics.

Some popular adversarial attacks include Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), to be discussed later. These aim to create adversarial examples, which involve applying perturbations to input images to produce an incorrect output. These perturbations are calculated by maximizing the network error and are typically bounded by some norm. An exception, however, is Unrestricted Adversarial Examples (UAEs)12 which involve unbounded perturbations. These are typically used for stress testing models before they are deployed in order to mimic adversaries they may come across in practice.

For this reason, the data used to train such machine learning models is critical in shaping its ability to overcome adversaries while maintaining accuracy. Data selected needs to be of high quality, diverse and representative of the task to be achieved. However, this best-case scenario is often difficult to accomplish in the real world due to scarcity of useful data due to privacy concerns, production/maintenance costs, involuntary addition of biases, etc.

Hence, Goodfellow et al. (2015)3 propose a solution to this problem known as adversarial training without the need for difficult to attain data. This method involves adding adversarial examples to the training set in order to improve model robustness and generalization. This solution works because it increases model exposure to adversaries during the training phase, while learning robust features and working to minimize the cost function on adversarial examples.

In this paper, we explore how and to what extent training on synthetically generated data affects adversarial robustness in neural network classifiers compared to training on real data. Specifically, it explores to what extent does adding data created from diffusion models to the training sets of image classifiers trained on the Stanford Cars and MNIST datasets help improve performance on adversarial examples.

The code is available on GitHub

(link: https://github.com/ElegantArmour5/AdversarialRobustness).

Literature Review

Synthetic Data: Gowal et al. (2021)4 find that the inclusion of synthetically generated low-quality data to the training dataset can be used to improve adversarial robustness. To improve adversarial training, these images need to be diverse while complementing the original dataset. Furthermore, Singh et al. (2024)5 conclude that the addition of synthetic data to the training set can improve overall adversarial robustness over most metrics. They also propose the need for synthetic supervised clones, which are models trained solely on synthetic data using supervised training methods. Although Gowal (2021) conveys that synthetic samples compliment scarce real data, Singh (2024) reports improvements even with abundant real data, signifying that benefits are not only for scarce data scenarios. However, Li et al. (2024)6 put forward that although adversarial training can improve model performance against adversarial examples, it is prone to overfitting. Further, Xing et al. (2022) cautions that the addition of low-quality synthetic data to training sets can have opposite effects, worsening robustness. This is because when low-quality samples are used, the model learns poor shortcuts making it easier to fool. But research suggests that filtering bad images, data augmentation and validating with robust metrics can be leveraged to overcome this.

Diffusion Models: diffusion models are generative models that synthesize data, including images, text, etc, by adding noise to training data and then learning how to reverse this process. An example of such a model includes Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM). In addition, Rombach et al. (2021)7 propose a Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) which significantly reduces computational requirements without compromising image quality for generated images. This study was able to improve on the status quo for methods implemented for conditional image generation without the need for task-specific architecture. Chen et al. (2023)8 introduced AdvDiffuser, a novel diffusion model that can generate natural Unrestricted Adversarial Examples (UAEs), these are images that look different from the original image and cause the classifier to predict incorrectly (i.e. perturbations are not lp bounded, to be discussed later), without the loss of high-level information, that typically results in unnatural and low-quality UAEs. Images generated by AdvDiffuser are perceptually close to the original image, which can be leveraged during adversarial training to improve robustness. Further, Wang et al. (2023)9 concluded that the use of a better, newer diffusion model rather than Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) further improves adversarial training, likely due to their ability to create richer images that follow the input prompt better.

Adversarial Attacks: Originally, Szegedy et al. (2013)10 bring forward the idea that it is possible to purposefully make a deep neural network misclassify by applying a stealthy perturbation to an image, found by maximizing the network prediction error. They also find that the same perturbation can be used to misclassify a different model trained on another subset of the total dataset. Currently, Gao et al. (2023)11 propose a novel adversarial attack architecture that mimics real-world errors like typos, glyphs and phonetics in order to maintain semantic consistency. In comparison to Szegedy (2014), Gao (2023) capitalizes on natural errors, reducing the detectability gap. So, defences tuned to lp underperform when confronted with real-world noise. Both show cross-model transfer capabilities in vision and text respectively, arguing for defences targeting invariances rather than model architecture.

Adversarial Training: Goodfellow et al. (2015)3 suggest the idea of adversarial training, which refers to specialized training to improve model generalization and robustness over varying architectures and input data. It involves adding an imperceptible perturbation to the training set to help the model generalize better by training on these modified images. Additionally, Madry et al. (2017)12 further justify the idea of adversarial training and postulate that adversarially robust deep learning models can be created and would likely be accomplished soon. Further, Ballarin et al. (2023)13 propose a method to strategically intertwine adversarial training and adversarial purification, which involves using a diffusion model to remove adversarial perturbations, to be leveraged to improve adversarial robustness as compared to adversarial training and adversarial purification alone. Overall, adversarial training learns invariances while purification projects to a prior from training. Hybrids between the two are beneficial if attacks are off-manifold, but risk causing a shift in distribution if priors are mis-specified.

Applications of Adversarial Robustness: Chung et al. (2024)14 propose using adversarial robustness of counterspeech classifiers for abuse mitigation. Additionally, Bukhari et al. (2024)15 introduce the use of adversarial robustness and generative models for improved cloud resource allocation and predictive scaling. In all, Chung (2024) prioritizes semantic consistency while Bukhari (2024) prioritizes cost-to-latency-robustness trade-offs.

Methods

Problem Definition

This paper explores whether the addition of synthetically generated data using a diffusion model during training improves overall adversarial robustness and generalization. In particular, there are two main types of adversarial attacks: “white-box” or “black-box” attacks. During white-box attacks, attackers have access to the model parameters. However, this is not the case in black-box attacks. Adversarial attacks use approximated information about model parameters to alter pixel inputs to maximize the probability of error. These applied changes are called perturbations.

Let us consider this problem setting formally. Consider a standard classifier ![]() with data distribution

with data distribution ![]() , pairs of examples

, pairs of examples ![]() and corresponding labels

and corresponding labels ![]() . Further, consider loss function

. Further, consider loss function ![]() where

where ![]() represents the set of model parameters and

represents the set of model parameters and ![]() . Hence, our objective is to find suitable model parameters

. Hence, our objective is to find suitable model parameters ![]() such that the adversarial risk

such that the adversarial risk ![]() is minimized.

is minimized.

Let us begin by formally defining an adversarial perturbation. Consider a model ![]() which can correctly classify an image

which can correctly classify an image ![]() with its true label

with its true label ![]() :

:

(1) ![]()

When we add an adversarial perturbation ![]() to the input

to the input ![]() , the model predicts an incorrect label of

, the model predicts an incorrect label of ![]() :

:

(2) ![]()

In order to quantify the size of the perturbations, we use the norm to measure the size of the change applied to the image. For some (perturbation) vector ![]() , the norm

, the norm ![]() provides a measure of length in vector space. Different norm functions provide different measurements. We often care about ensuring that the norm of our perturbation is bounded; that is that the perturbation applied to the image is not too large. We can represent this constraint by an upper bound

provides a measure of length in vector space. Different norm functions provide different measurements. We often care about ensuring that the norm of our perturbation is bounded; that is that the perturbation applied to the image is not too large. We can represent this constraint by an upper bound ![]() on the norm:

on the norm:

(3) ![]()

In this context, ![]() is the norm which measures the size of perturbation

is the norm which measures the size of perturbation ![]() . More specifically, adding a subscript

. More specifically, adding a subscript ![]() to the norm, i.e.

to the norm, i.e. ![]() , indicates the specific norm used. The types of norms are defined as follows:

, indicates the specific norm used. The types of norms are defined as follows:

L0 Norm: this is the number of nonzero elements in the perturbation vector. These are usually in the form of sparse, realistic edits like a small patch or flipping a few pixels.

L1 Norm: is the total sum of the magnitudes of all elements in the perturbation vector. This represents absolute change and provides a middle-ground budget with somewhat sparse, mild tweaks.

L2 Norm: the Euclidean distance of the perturbation vector ![]() , which is a sum of squares of the elements in vector

, which is a sum of squares of the elements in vector ![]() . These often include gaussian, noise-like perturbations with faint noise spread throughout the image.

. These often include gaussian, noise-like perturbations with faint noise spread throughout the image.

L∞ Norm: involves the largest element of the perturbation vector. This is implemented the most due to its robustness and convenience.

These norms are critical to define the attacker’s space. Different norms produce different looking attacks and require different defences. Robustness is only meaningful under the threat model declared.

As seen in figure 2, ![]() perturbations pose a threat to non-robust classifiers which hence need to be resolved. Let us now consider adversarial attacks, which are algorithms that produce perturbations which optimally disrupt the classification power of our classifier

perturbations pose a threat to non-robust classifiers which hence need to be resolved. Let us now consider adversarial attacks, which are algorithms that produce perturbations which optimally disrupt the classification power of our classifier ![]() . Such algorithms take an example

. Such algorithms take an example ![]() as input where

as input where ![]() belongs to class

belongs to class ![]() and returns examples

and returns examples ![]() that very closely resemble

that very closely resemble ![]() but the model misclassifies

but the model misclassifies ![]() as belonging to

as belonging to ![]() . Madry et al. propose a saddle point problem by allowing perturbations

. Madry et al. propose a saddle point problem by allowing perturbations ![]() that formalizes the adversary’s manipulative power. Incorporating an adversary into the classifier stated above, we have:

that formalizes the adversary’s manipulative power. Incorporating an adversary into the classifier stated above, we have:

(4) ![]()

Instead of directly passing the inputs to the model from distribution ![]() , the adversary perturbs the input first.

, the adversary perturbs the input first.

This problem describes a composition of an inner maximization problem and an outer minimization problem, where the maximization involves calculating the impact of the adversary and the minimization is the standard optimization problem. Furthermore, this problem represents a goal that a classifier should aim to achieve, upon which it can be deemed as perfectly robust to the specified attack model.

The goal to maximize the inner perturbation ![]() and to minimize the outer adversarial risk poses a saddle point problem. A saddle point, or minimax point, is a point where all partial derivatives are equal to 0. For example, consider a potato chip like a Pringle. The point where the convex open-top curvature meets the concave open-bottom curvature is called the saddle point. Similarly, it can also be found at the bottom of a horse saddle which also forms a hyperbolic paraboloid shape.

and to minimize the outer adversarial risk poses a saddle point problem. A saddle point, or minimax point, is a point where all partial derivatives are equal to 0. For example, consider a potato chip like a Pringle. The point where the convex open-top curvature meets the concave open-bottom curvature is called the saddle point. Similarly, it can also be found at the bottom of a horse saddle which also forms a hyperbolic paraboloid shape.

One of the most popular and successful attack methods is called the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) proposed by Goodfellow et al. (2015) which incorporates the addition of an imperceptibly small perturbation to the input. This perturbation vector is composed of elements that are equal to the sign of the elements of the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input, or mathematically:

(5) ![]()

Where ![]() represents the perturbation,

represents the perturbation, ![]() represents the perturbation budget which is the greatest possible per pixel change,

represents the perturbation budget which is the greatest possible per pixel change, ![]() represents the model parameters,

represents the model parameters, ![]() represents the model inputs,

represents the model inputs, ![]() represents the labels with respect to

represents the labels with respect to ![]() and

and ![]() represents the loss function used to train the network. Effectively, altering the input in the direction of the increasing loss function

represents the loss function used to train the network. Effectively, altering the input in the direction of the increasing loss function ![]() .

.

Another famous adversarial attack is the Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) method. Notably, PGD is an iterative process while FGSM is a one-step solution. This means that PGD is more computationally expensive and although slightly better performing, FGSM is a very good approximation which is faster and simpler. Overall, PGD is a multi-step ascent process on the loss function as shown:

(6) ![]()

where ![]() represents the input at iteration

represents the input at iteration ![]() ,

, ![]() represents the gradient of the loss function

represents the gradient of the loss function ![]() with parameters

with parameters ![]() , inputs

, inputs ![]() and corresponding labels

and corresponding labels ![]() , sign() function to indicate the direction of the step,

, sign() function to indicate the direction of the step, ![]() represents the step size or learning rate and

represents the step size or learning rate and ![]() represents the projection operator that ensures the perturbed input remains within the set

represents the projection operator that ensures the perturbed input remains within the set ![]() .

.

Figure 4 below shows how FGSM perturbations vary from PGD for the same original image and also the predictions from a pretrained car make and model classifier. the predictions from a pretrained car make and model classifier.

The Dataset

For this paper, we decided to utilize the Stanford Cars dataset presented by Krause et al.16, which contains images of cars of different makes and models, and MNIST presented by Deng et al.17 which contains images of hand drawn digits Although CIFAR-10 is the usual in adversarial training studies, MNIST combines robustness with low-resolution images with coarse categories. Stanford Cars offers a high-resolution, fine-grained benchmark, forcing models to rely on semantically significant cues like headlights, trims, etc. rather than texture-based shortcuts.

In total, the Stanford Cars dataset is composed of approximately 16,185 images and 196 classes, which results in roughly 83 images per class. These images are split into training and testing categories, each having 8,144 and 8,041 images respectively, modelling a rough 50-50 split. The classes include the make, model and year of 196 different cars, for example, 2012 BMW M3 coupe.

The MNIST dataset contains images of hand drawn digits from zero to nine. It contains approximately 70,000 images over 10 classes resulting in approximately 7,000 images per class. A sample of an MNIST image can be seen in figure 6 below.

Synthetic Data Generation

This paper uses the MNIST and Stanford Cars datasets as available from PyTorch’s Torchvision Datasets library. It contains approximately 70,000 images, but since the synthetic creation of 70,000 images from a diffusion model was not computationally feasible, we decided on 200 images per class. Since MNIST contains all digits from zero through nine, this means that the synthetically created dataset contained a total of 2000 images over 10 classes, sufficient for training the EfficientNet B0 model18 to a high degree of accuracy.

However, as this paper is being written, the Stanford Cars dataset is now deprecated and needs to be downloaded and imported manually. The Stanford Cars dataset contains approximately 83 images per class. The diffusion model was set to generate the same 83 images per class for a fair comparison.

The diffusion model implemented to create this dataset was the Hugging Face Stable Diffusion v2-1-base. This model was loaded via the StableDiffusionImg2Img Pipeline. This was done to eliminate the need for prompt-based data generation. Prompts would need to be redone for each image generated in order to maintain healthy dataset diversity, rather in this case, the synthetic dataset should be able to closely resemble the original dataset diversity.

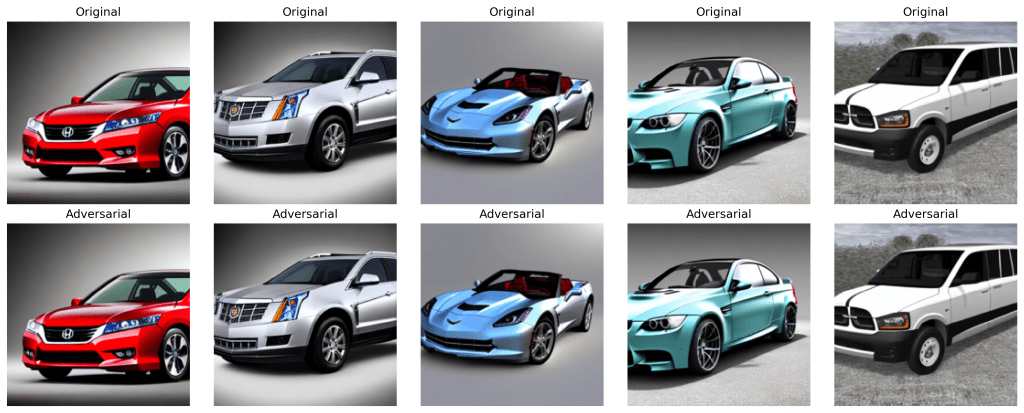

We evaluated the quality of the synthetic data using LPIPS and CLIP scores. We found that although their LPIPS scores represent moderate pixel-wise difference, their CLIP scores indicate high semantic content consistency. As seen in figure 7 below, to the eye the generated images look quite similar.

Experiment

Gowal et al. (2021)4 propose that the addition of synthetically generated low-quality data to the training set can improve adversarial robustness. This experiment aims to justify these findings. We propose an experiment involving two models of the same architecture; however, one is trained on real data (Stanford Cars and MNIST) while the other model was trained on the synthetically generated datasets (we term them SynMNIST and SynCars).

The chosen classifier is the EfficientNet B0 model for MNIST and ResNet-50 for Stanford Cars, both initialized with default weights. This choice was to accommodate for limited compute and provided an even balance between training time and performance. ResNet-50 was needed for Stanford Cars due to the large number of classes.

Two identical EfficientNet B0 and Resnet-50 models with default weights are created and then further tuned on the actual and synthetic data over 10 epochs for MNIST and 28 for Stanford Cars.

We then generated adversarial examples using the Adversarial Robustness Toolbox (ART)19 for each model, specifically 1 example from each class, and analysed the performance of both models on these examples to see which model performs better. All adversarial examples were generated using FGSM with ![]() .

.

To further generalize the claim, we experimented with adding a proportion of synthetic data to the real training set. Specifically, we experimented with adding 25%, 50% and 75% of synthetic data to train a classifier on the MNIST dataset and evaluate performance on adversarial examples.

Results

Training Phase

The results of fine tuning Efficient Net B0, initialized with default weights, on the original and synthetic MNIST datasets are as follows:

| Accuracy Type | Original Training Set | Synthetic Training Set |

| Base Accuracy | 98.65% | 97.45% |

| Accuracy on Adv. Examples | 17.85% | 12.65% |

Specifically, figure 8 below outlines the per class accuracy of the model trained on the synthetic training set tested on real images.

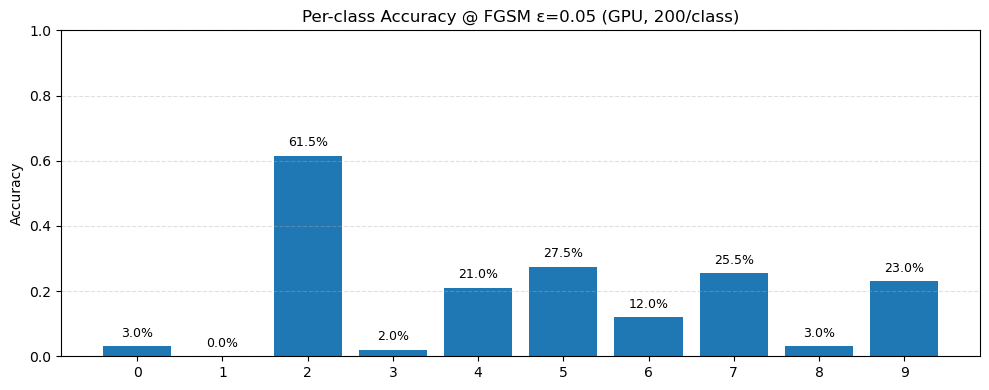

Figure 9 below shows its performance on adversarial examples.

Similarly, the model trained on real data scored 98.65% for baseline accuracy tested on real MNIST images. When tested on adversarial examples created using FGSM with ![]() , the model had an adversarial accuracy of 17.85%. The per-class accuracy can be seen in figure 10 below.

, the model had an adversarial accuracy of 17.85%. The per-class accuracy can be seen in figure 10 below.

We see that for similar starting baseline accuracy, training completely on the synthetic set for MNIST dataset seems to be worse since the average accuracy on adversarial examples is lower by approximately 5%.

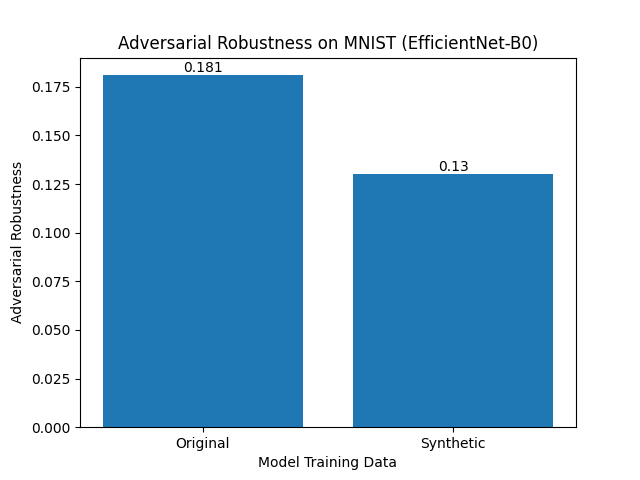

Figure 11 below outlines the adversarial robustness,![]() , for each model.

, for each model.

We find that the model trained on original data scores higher than that trained on synthetic data.

Similarly, for Stanford Cars, the results can be seen in table 2 below.

| Accuracy Type | Original Model | Synthetic Model |

| Base Accuracy | 76.57% | 96.88% |

| Accuracy on Adv. Examples | 3.54% | 22.90% |

We find that the baseline accuracy is significantly greater for the Synthetic Model (SynCars) by 20.31%. Both ResNet 50 models were initialized with default weights and trained for 28 epochs in the same way. Hence, this could indicate that it is more difficult to learn semantically significant cues due to the high-resolution images of Stanford Cars than the textures of lower resolution synthetically generated images.

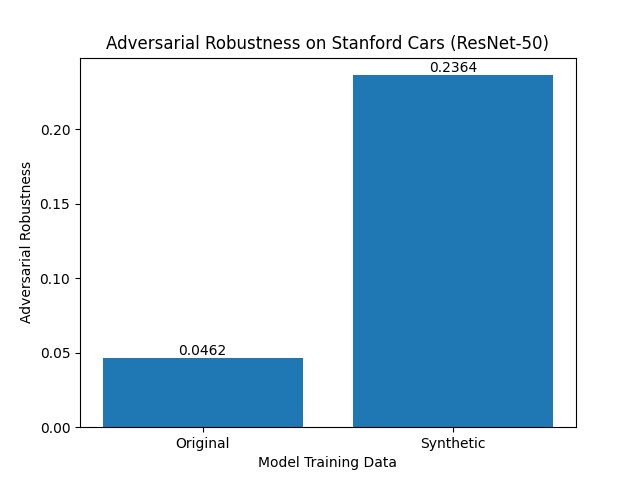

We note that the increased accuracy on adversarial examples for the SynCars model would likely partly be a result of the higher starting baseline accuracy. To examine this, we plot the adversarial robustness scores of each in figure 12 below.

The higher adversarial robustness of the synthetic model could be explained by the nature of the synthetic images used. The higher LPIPS and CLIP scores between real and synthetic images represents worse perceptual similarity but higher semantic similarity. This means that training on synthetic data could have allowed the model to learn semantic features better, whereas in the original data, the model may have been distracted by perceptual features like texture, noise, colour, contrast, etc.

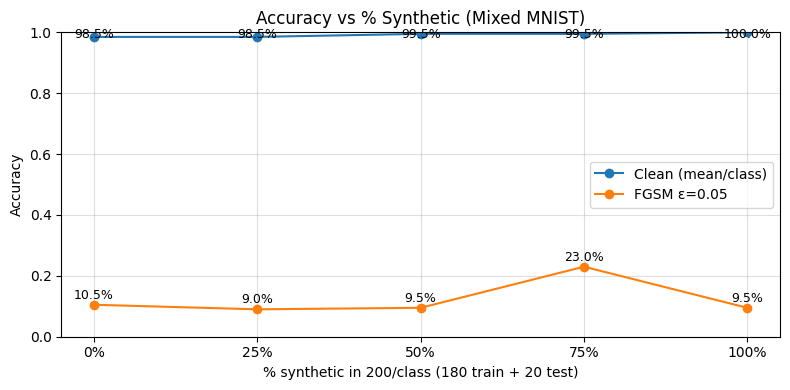

Further, we also find compelling results when testing on MNIST mixed data, as seen in figure 13 below.

We find that the addition of synthetic data to the training set seemingly has an arbitrary effect on adversarial accuracy when tested on FGSM ε=0.05. The adversarial accuracy remains approximately constant at ~9.5%, with an outlier when 75% synthetic data is used. This outlier could be explained by the randomness of real or synthetic data seen by the model in each run.

Seeing no resulting adversarial accuracy change from the addition of synthetic data could be representative of the quality of the synthetic data. The low LPIPS score of the synthetic MNIST data when compared to real data may be indicative of low perceptual similarity. Models may rely on this for the MNIST dataset due to the natural low-quality characteristic of the dataset, and semantic consistency alone may not be enough.

Naturally, the model would learn features of more abundant data better. Having a higher proportion of real or synthetic data may tip the model to either side. It could be a reasonable assumption to see a performance boost when there is an even 50-50 split between real and synthetic data, but again this would depend heavily on the quality of the synthetic data generated and the process by which it is generated.

Singh et al. (2024) convey that when generating synthetic data, it is paramount to use an apt prompt for generation.

Discussion

What do these results mean?

Our results indicate that the model trained on synthetic data seems to perform better than the model trained on real data on the adversarial examples set for Stanford Cars dataset while the opposite is true for the MNIST dataset. However, while testing for mixed data we observe that there seems to be no such correlation between proportion of synthetic data and adversarial accuracy. This suggest that our hypothesis that adding synthetic data to the training set improves overall robustness to adversarial attacks could likely be incorrect.

This change seems more significant for the MNIST dataset because the quality of synthetic data produced seems to be a better fit to the MNIST dataset than the synthetic cars data compared to Stanford Cars dataset.

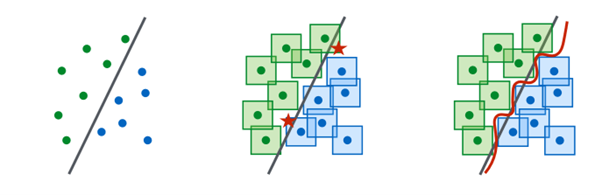

Specific improvements in adversarial robustness from the addition of synthetic data is task specific. This improvement could be explained by exposure to high-quality synthetically generated data during training that improves model performance on edge cases. Adversarial attacks usually take advantage of edge-case scenarios that standard models may not have seen during training. Hence, training on high-quality synthetic data allows models to learn to recognize and counteract these cases. Madry et al. represent this using a diagram as seen in figure 14 below.

The addition of low-quality synthetic data would have the opposite effect for most tasks. Since synthetic data is noisier, it could obscure the intended features the model should learn for a truly robust classifier. In our case, we find that training on synthetic data does not produce a significant change to the decision boundary on the EfficientNet B0 classifier, as seen by figure 15 below. The synthetic model’s ridge looks slightly higher peaked that suggests a slightly steeper local margin, but there is no overall rotation or shift in the decision boundary.

Overall, synthetic image generation helps to overcome the data shortage that affects many industries today. Data is scarce due to its sensitivity and hence synthetic data proves to be a more plausible, accessible alternative. This allows models to be trained on abundant synthetic data and resolves underlying issues that may arise from undertraining with insufficient data. However, the quality of data used is one of the most important features to consider when evaluating whether the addition of synthetic data can improve adversarial robustness.

Prior Work

Goodfellow et al. (2015)3 initially proposed the idea of adversarial training and conceptualized that adding adversarial examples into the training set would help improve performance against adversaries. However, some research suggests that the addition of synthetic data, or training solely on synthetic data, need not improve adversarial robustness and moreover depends on factors such as the quality of generated data. Xing et al. (2022)20 find that the addition of poor-quality generated data may not improve overall model performance and instead introduce noise which hinders it instead. Our findings corroborate this.

Further, Singh et al. (2024)5 propose that training on synthetic data alone leaves models vulnerable to adversarial and real-world noise rather than training on real data. This means that the addition of synthetic data may not contribute to an increase in robustness. The process of synthetic data generation should be carefully considered.

Limitations and Future Work

The method of data generation could be varied to better analyse the impact of data on adversarial robustness. A larger diffusion model with more parameters could be used as well as a smaller one to evaluate the differences. Additionally, different types of diffusion models could be used to evaluate their impact on adversarial robustness. More data quality metrics can be used to evaluate the relationship between data quality and adversarial robustness.

This paper explored specifically the MNIST and Stanford Cars dataset, whereas it could be beneficial to explore other types of datasets as well including text, medical images, etc. Since adversarial robustness varies across different tasks, testing on these can help fully generalize the claim.

It may also be worth exploring how addition of adversarial examples from different attacks and perturbation budgets into the training set can improve model generalization.

Conclusion

This study aimed to analyse how training on synthetic data affects adversarial robustness in image classifiers EfficientNet-B0 and ResNet-50. Although the integration of synthetic data into the training set improves model diversity and edge case exposure, its benefits to adversarial robustness depend upon the quality of the data. We found that training on synthetic data generated by the StableDiffusionImg2Img pipeline from Hugging Face does not help improve adversarial robustness in the context of FGSM attacks, MNIST and Stanford Cars. These results are limited by the data generation methods used and the type of attack deployed. It could be worth analysing the impact of synthetic data addition on other datasets, tasks, and model types. Much has been done in self-supervised learning, transfer learning and multi-modal models. In conclusion, although there lies great promise ahead for the use of synthetic data in adversarial robustness, its true impact heavily depends on the nature of this generated data for addressing real world adversarial scenarios.

References

- S. H. Park, S. -H. Lee, M. Y. Lim, P. M. Hong and Y. K. Lee, “A Comprehensive Risk Analysis Method for Adversarial Attacks on Biometric Authentication Systems,” in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 116693-116710, 2024, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3439741. [↩]

- T. B. Brown, D. Mané, A. Roy, M. Abadi, J. Gilmer. Unrestricted adversarial examples. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1809.08352 (2018). [↩]

- I. J. Goodfellow, J. Shlens, C. Szegedy. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. International Conference on Learning Representations, ai.google/research/pubs/pub43405 (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- S. Gowal, T. A. Mann, A. D. Buesing, J. Uesato, R. Bunel, K. Kawaguchi, P. Kohli. Improving robustness using generated data. Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, arxiv-export-lb.library.cornell.edu/abs/2110.09468 (2021). [↩] [↩]

- K. Singh, V. Nair, S. Vasudevan, M. Alfarra, A. Courville, A. Krishnan, Y. Bengio. Is synthetic data all we need? Benchmarking the robustness of models trained with synthetic images. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2405.20469 (2024). [↩] [↩]

- L. Li, J. Qiu, M. Spratling. AROID: Improving adversarial robustness through online instance-wise data augmentation. International Journal of Computer Vision, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-024-02206-4 (2024). [↩]

- R. Rombach, A. Blattmann, D. Lorenz, P. Esser, B. Ommer. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2112.10752 (2021). [↩]

- [4] X. Chen, Z. Wang, Y. Liu, C. Xu, B. Li. AdvDiffuser: Natural adversarial example synthesis with diffusion models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2023, 4539–4549 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv51070.2023.00421. [↩]

- Z. Wang, L. Wang, X. Zhang, C. Xu, B. Li. Better diffusion models further improve adversarial training. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2302.04638 (2023). [↩]

- C. Szegedy, W. Zaremba, I. Sutskever, J. Bruna, D. Erhan, I. Goodfellow, R. Fergus. Intriguing properties of neural networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1312.6199 (2013). [↩]

- H. Gao, Y. Yang, Z. Wu, L. Wang, Z. Zhou, M. Gong, J. Liu. Evaluating the robustness of text-to-image diffusion models against real-world attacks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2306.13103 (2023). [↩]

- A. Madry, A. Makelov, L. Schmidt, D. Tsipras, A. Vladu. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1706.06083 (2017). [↩]

- E. Ballarin, J. Zhou, D. Das, C. Zielinski, J. P. Pappas, N. Carlini, D. Tsipras. CARSO: Blending adversarial training and purification improves adversarial robustness. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2306.06081 (2023). [↩]

- Y. Chung, J. Bright. On the effectiveness of adversarial robustness for abuse mitigation with counterspeech. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, 6988–7002. [↩]

- W. Bukhari, W. Akram. Generative models and adversarial robustness in autonomous AI: Enhancing cloud resource allocation and predictive scaling through explainable AI. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21663.16803 (2024). [↩]

- J. Krause, M. Stark, J. Deng, L. Fei-Fei. 3D representation and recognition. Proceedings of the 4th IEEE Workshop on 3D Representation and Recognition (3dRR-13), ICCV, Sydney, Australia (2013). [↩]

- Deng, L. (2012). The mnist database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 29(6), 141–142. [↩]

- Tan, M., & Le, Q. V. (2019). EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.11946 [↩]

- M. I. Nicolae, M. Sinn, M. Mirman, M. Ernst, A. Rahmati, D. Li, S. G. Tzeng, B. Tran, A. Prakash. Adversarial robustness toolbox v1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1807.01069 (2018). [↩]

- Xing, Y., Song, Q., & Cheng, G. (2022). Unlabelled data help: Minimax analysis and adversarial robustness. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2202.06996 [↩]