Abstract

The global childhood obesity epidemic has been a rising public health concern, especially over the past two decades. Obesity is associated with premature death, type 2 diabetes, and many other serious health conditions. However, developing healthy eating habits from an early age is a way to prevent diet-related diseases. Given the substantial increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity, health campaigns worldwide have depended on multiple methods to reduce this issue, including physical activity, diet-control programs, and surgery. Recent studies have found an additional promising way to promote healthy eating among children: cartoons. This study analyzes the effects of cartoons promoting healthy eating on children’s food choices. We hypothesized that students exposed to the cartoon images promoting nutritious foods over time would develop a more positive attitude towards these foods and be more willing to consume them in daily life. To test this hypothesis, we randomly distributed 84 students between the ages of 7 to 8 into two groups and exposed one group to the cartoon images and kept the other as the control. For four consecutive weeks, both groups were asked to rate a variety of common food items on a survey on how appetizing they think they are. Based on answers to the surveys, the participants exposed to the cartoons rated 8 of the 12 healthy food items promoted by the cartoons statistically significantly higher by the fourth week. Although using cartoon images is a promising way to reduce the prominence of childhood obesity, combining healthy eating cartoons with other traditional healthy eating techniques should be considered.

Keywords: Cartoons, childhood obesity, healthy eating habits, cognitive development, food choices.

1. Introduction

It is well known that children love sweet and salty foods but avoid other more nutritious options, like their fruits and vegetables. This stereotype can be seen throughout children’s entertainment media, such as children’s cartoon series or movies, influencing their eating habits and views on healthy foods. However, establishing healthy eating habits early in life can encourage individuals to maintain a more nutritious diet throughout the rest of their lives1. Therefore, introducing children to healthy foods is crucial for preventing many diet-related diseases prevalent in modern society.

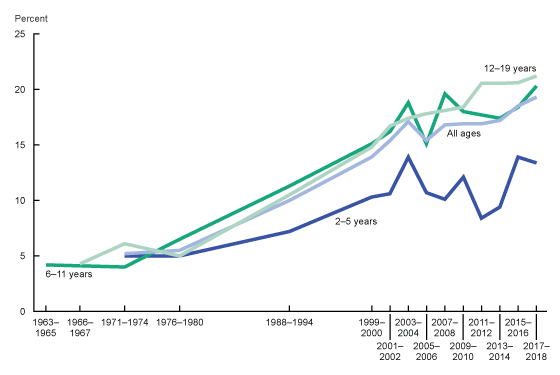

Childhood obesity is an escalating global public health crisis that has become a growing concern among parents and health professionals. It is a condition characterized by a child having a higher body mass index (BMI) relative to age, height, and sex2. The prevalence of obesity and other health issues in children has been rising at an alarming pace (Figure 1). For instance, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 160 million adolescents and children aged 5-19 worldwide were classified as obese in 2022, and almost 400 million children are overweight3. Overweight children face many physical, psychological, and social challenges. For example, obesity can affect their self-esteem and confidence. Many obese or overweight children may exhibit traits such as withdrawal, passivity, low self-image, and a fear of rejection. Furthermore, overweight children are more likely to become overweight adults, which carries an increased risk of illness and premature death4. For these reasons, in 2021, the WHO states that childhood obesity is one of the most threatening public health problems of the 21st century.

In addition, treating obesity can be extremely costly. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the United States spends approximately $173 billion every year on diet foods, medications, devices, and programs to treat obesity6. In addition to physical exercise and other methods in treating obesity, it is also crucial to minimize exposure to the marketing of unhealthy products and decrease the influence of these advertisements to prevent an unhealthy diet. According to medical professionals in health and nutrition, despite many health benefits, consuming “fruits and vegetables among children and adolescents in the United States remains below the recommended level”7. Instead, they consume excessive amounts of sugary and salty foods that can adversely impact their BMI and overall health. Thus, it is crucial to familiarize people from a young age with a wider variety of foods to prevent them from sticking to a familiar selection of unhealthy products and encourage the development of lifelong healthy eating behaviors.

Many popular food and beverage companies often collaborate with children’s media to market junk food and other less nutritious products by endorsing them with their favorite cartoon characters8. In contrast, healthy products are rarely marketed or promoted to children. According to Valérie Hémar-Nicolas, a professor of consumer behavior and a researcher of children’s food consumption, cartoon media can influence children’s diets by introducing them to new foods and encouraging them to purchase or consume them. Cartoons are one of the most consumed types of media in children. For example, children ages 2 to 11 watch an average of 30 hours of cartoons every week9. Although cartoons have primarily been used in the past to promote highly processed and sugary foods, they can also encourage the consumption of more nutritious options, such as fruits and vegetables. This paper analyzes how prolonged exposure to cartoon images and characters promoting healthy foods can encourage children to make healthier eating choices. It will first review past literature and the study’s methodology and then discuss the application and limitations of the findings.

2. Literature Review

This paper explores how repeated exposure to certain cartoon images can encourage children to select healthier products. Past studies have focused extensively on how children’s media have promoted unhealthy eating through advertisements and the impacts cartoons can have on children’s behaviors. This study aims to fill the gap in the current literature regarding the effectiveness of cartoons on children’s eating habits over an extended period.

2.1 Children’s Natural Food Preferences

Food neophobia is the fear or reluctance to try new or unfamiliar foods. Previous research has shown that food neophobia can be a significant factor in shaping someone’s eating habits10. Children with food neophobia generally consume fewer nutritious foods and often limit their diets to a small, familiar selection of foods high in salt, sugar, or fat. Alice Binder, a researcher focusing on health communication, the effects of food placement on children, and targeted advertising, investigated the influence of food neophobia by presenting children aged 6 to 10 years with either a cartoon absent of food influences or one depicting children eating and discussing fruits like blueberries11. The study revealed that children with high levels of food neophobia avoided selecting healthy snacks, even when they were aware that their peers preferred them. Consequently, it is crucial to expose children to a variety of nutritious foods to encourage them to eat them as food neophobia plays a huge role in a child’s decision-making process. Thus, familiarizing children with novel foods can help reduce their fear of trying them so they would be willing to consume them in a real-life scenario.

However, encouraging healthy eating in children through media highlighting healthy products is considerably more challenging than promoting unhealthy food choices. People tend to have a biological preference for sweet and salty foods, and this natural preference for less healthy foods is strengthened by cues in the media12. Children’s food neophobia and aversion to unaccustomed foods can be addressed by offering opportunities to try them or by repeatedly introducing them in a positive setting, which can enhance their preference for them. Hence, children’s food preference is linked to their familiarity with foods; the more familiar the food, the more it is liked and will be consumed. Additionally, cultural differences can also play an important role in shaping children’s food preferences by influencing the types of foods they are exposed to from an early age, as well as the values and traditions surrounding certain foods. Specific flavors and cooking styles in various cultures can create a sense of familiarity and comfort with certain foods. Previous studies have examined the effects of children’s media on improving food familiarity with children after a single instance of exposure, such as showing them a graphic image encouraging the consumption of a fruit. These experiments found short-term effects of improved fruit and vegetable consumption that faded shortly after the study. This study examines the extent to which exposure to cartoons can help familiarize children with healthy foods over several continuous weeks to determine if they will choose increased amounts of nutritious food items throughout the study.

2.2 Changing Children’s Dietary Habits

Cartoons can motivate children to choose more nutritious products by featuring healthy food items that are not biologically preferred. According to the social learning theory, people from a young age learn new behaviors by observing and imitating others13. Children often learn new behaviors by replicating what they see from role models, the people they love or admire, such as their parents or animated characters. Consequently, the promotion of specific foods or eating habits displayed by a child’s loved animated characters can influence their food choices. Research has shown that children exposed to a variety of fruits and vegetables at a young age developed healthier eating habits and tended to prefer those foods as they got older10. In a series of studies by Kotler et al., they found that popular children’s animated characters can effectively influence kids to choose certain foods over others. In one of their experiments, which looked at children’s self-reported preferences, children were more likely to favor one food over another when it was linked to a character they liked and recognized14. The findings from these studies indicate that cartoon characters can enhance the appeal of the promoted product to children, increasing the likelihood that they will want to buy or consume that food.

2.3 Promoting Healthy Eating in Children

Other current approaches have aimed to encourage healthier eating behaviors in elementary school students by offering various incentives, such as rewards for eating a serving of fruit or vegetables15. The rewards included special tokens redeemable at the school store, as well as small stickers and gifts for simply selecting nutritious food items during lunch. These studies found an improvement in daily fruit and vegetable consumption, but the results were temporary and rarely persisted after the incentives were removed15. A 2019 study conducted by Tzoutzou et al. found that many popular cartoon series on television frequently feature unhealthy foods, such as sodas, sweets, and salty snacks. These foods are often presented appealingly, either being eaten or positively talked about by cartoon characters, which makes them more attractive to children and adolescents even if they contain little or no nutritional value16. However, the same can be done to promote more nutritious foods, but to varying degrees. More research needs to be done to examine the extent to which children’s media can help establish a long-term healthy diet.

2.4 The Effects of Children’s Media on Their Eating Habits

Children’s entertainment media is filled with the influences of unhealthy food. The most frequently promoted foods and beverages through advertisements on TV are carbonated sodas, salty snacks, and sweets. Studies have found that highly processed food items are promoted four times more than healthy foods in TV commercials17. Cartoons are among the most widely consumed forms of media by children. Cartoon characters can range from simple images and brand mascots to popular figures created by large entertainment media enterprises. Previous research has shown that children receive many food messages through cartoons and television while consuming various media18. In an experiment conducted by Villegas-Navas and colleagues, 62 children aged 7 to 11 were exposed to 16 food placements in cartoons, while another group of 62 children of the same age in the control group were shown cartoon scenes without food placements. After watching the cartoon, participants were asked to complete a choice task to choose between four foods varying in nutrition. The results of the study indicated that “non-branded, low-nutritional-value foods placed in cartoons are an effective strategy for modifying children’s food choices,” as they selected considerably more nutritious options after viewing the cartoon18. This study demonstrates that messages within cartoons can have practical implications for altering children’s food choices. However, the study did not control for other variables that could have affected children’s food selections and exposed them to a short scene, resulting in short-term effects on improved pro-nutrition behaviors. Therefore, examining prolonged exposure to cartoons featuring food placements is important to determine if children can develop long-term healthy eating habits.

2.5 Gap Analysis

There is an abundance of research on the repeated exposure to processed and snack foods rich in sugars and fats through children’s media and its contribution to the rise of childhood obesity19. The majority of these studies examine the effects of television advertisements and commercials. This study aims to examine whether cartoons can be used in a similar way to promote healthy foods. Past studies have researched the immediate effects of cartoons after a single exposure to the food stimuli. However, these studies found that the participants’ improved healthy food choices often disappeared following the study. There is limited knowledge on how prolonged exposure to cartoons can encourage children to select healthier food options over time. This study contributes additional knowledge necessary to address this gap in the current literature by examining how children’s eating choices evolved as they were continuously exposed to cartoons promoting healthy eating behaviors. Given the detrimental risks of childhood obesity and its long-term effects on an individual’s life, reducing it is an important concern that can be alleviated by incorporating various alternative and creative methods to encourage children to eat healthier.

3. Methodology

3.1 Experimental Research

An experimental design was employed for this study because it provides reliable and unbiased data. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), experimental designs are essential in “helping readers to understand more clearly how the data were obtained and, therefore, assisting them in properly analyzing the results”20. Experimental designs determine a causal relationship between two variables, an independent variable and a dependent variable21. In the study, the independent variable is the exposure to healthy eating cartoons, and the variable being studied is the ratings of the food items in the surveys. To investigate the effect of the independent variable, participants were evenly and randomly distributed into two groups. A classic experimental design includes an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group was exposed to the cartoons displaying healthy eating messages every week, while the control group was not given any form of influence. The surveys given to the participants every week would provide quantitative evidence on whether or not the cartoon images affected how they viewed various healthy food items.

3.2 Ethical Considerations and Participant Security

Since the study involves human participants, the research process was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) regarding the ethical considerations of the study. According to another paper by Binder et al., children under five years of age begin developing their sensory processing abilities but may find it challenging to recall or articulate specific memories22. Between the ages of 6 and 9, children start to effectively process and retain information, as well as understand the content of messages. Thus, we decided to study second graders because, at around 7-8 years old, children are self-aware and vulnerable to external influences, yet still able to make their own decisions. Students older than 10 begin to think independently and reason abstractly, meaning their habits are less likely to be influenced by the study, and they may have a better understanding of its purpose, which could lead to greater error22. Participants were not informed of the purpose behind the study to ensure response validity, as knowing the true purpose of the study beforehand could alter participants’ behavior or responses. However, Informed Consent forms were sent to the students and their parents, discussing the general nature of the study, possible discomforts, benefits of the study, and how the participants would be protected. Furthermore, we made it clear that participation is voluntary and that participants are free to withdraw at any point in the study. To protect the data and confidentiality of the participants, the surveys were anonymous, and no personal data was collected. In the end, we obtained 88 participants’ consent forms signed by the students and their parents.

3.3 Data Collection

After attaining approval to begin the study, the 88 students were randomly separated into two groups of 44 students. Since cartoons are a source of media that is watched continuously over time, the study was planned to last for four continuous weeks to examine how prolonged exposure to cartoon images can affect their eating behaviors. We created a weekly survey (See Appendix A) that displayed images of common food items including 12 nutritious food items (e.g. carrots, broccoli, and peas) and 4 unhealthy food items (e.g. donuts, ice cream, and candy). Unhealthy foods were included in the surveys to serve as a comparison to mimic how eating behaviors function in real life. This would help show whether or not the students would choose to consume these healthy yet less appetizing foods despite the influences of other delicious but unhealthy foods. Below the pictures of the foods was a forced-choice scale from 1 to 4 to rate how appetizing they think the food is and how willing they are to consume it. An even-numbered scale is used for this study because by eliminating the neutral option, participants will be compelled to choose a side, potentially leading to a more decisive response. The surveys were printed out as not all the students may have access to computers. Additionally, participants were given 12 sets of cards that showed a cartoon vegetable character with text promoting the consumption of that vegetable (See Appendix B). The 12 cartoon vegetables on the cards are the same foods as the healthy items on the surveys. These cards were original creations drawn through a digital art program and printed onto durable cardstock

Each week, tthe same survey to both groups. Participants in the experimental groups were given the cards and exposed to healthy eating messages, while participants in the control group were not exposed to anything. To ensure students in the experimental group interacted with the cards, they were asked to participate in a fun and interactive game similar to a scavenger hunt. Throughout each week, they were encouraged to look for these foods at home or during school lunches, incentivizing them to try vegetables they may have been hesitant to try in the past. In addition, parents were asked through the Informed Consent form if they could purchase or encourage the students to try these foods. By attempting foods that they may not have tried before, participants can better familiarize themselves with them and potentially develop a more positive attitude towards foods they previously were unwilling to consume.

4. Findings

After data was collected from the surveys from all four weeks, the mean rating for each healthy food item was calculated every week by averaging all the scores in each group. To determine if there was a significant change in food ratings over the study between the two groups, statistical significance calculations were performed using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test is a non-parametric statistical test used to compare two related samples or repeated measurements of the same group23. It is often used to determine if there is a significant difference between two sets of data that are paired or related to each other. It is also used to examine the effect of a treatment introduced during a study to evaluate changes in participants’ behaviors. This study compares the ratings between the experimental group and the control group to examine whether or not the cards have a substantial effect on the ratings of the foods.

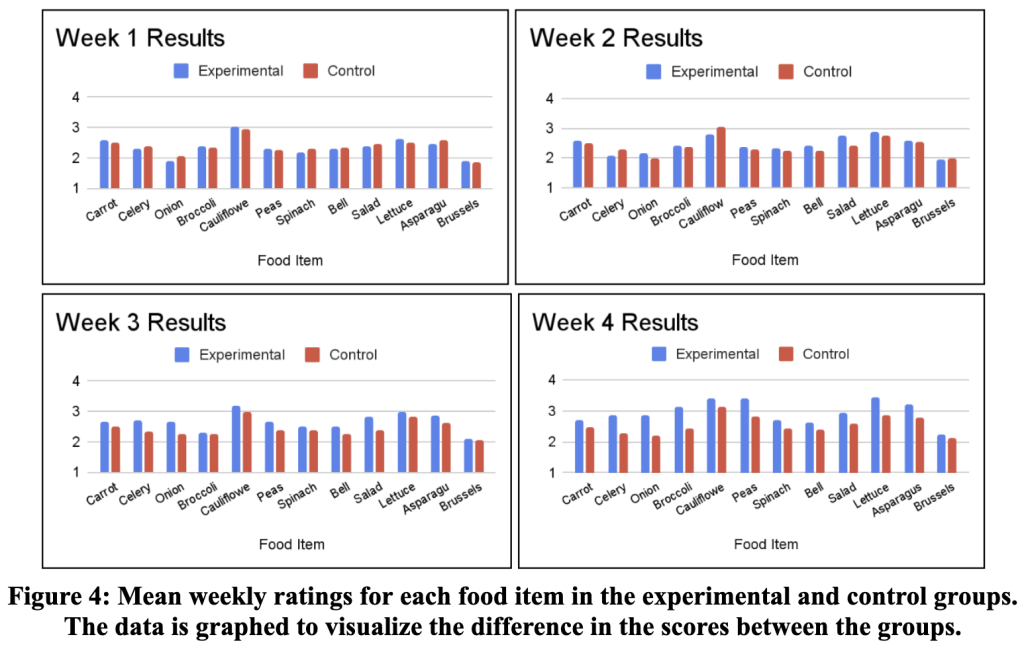

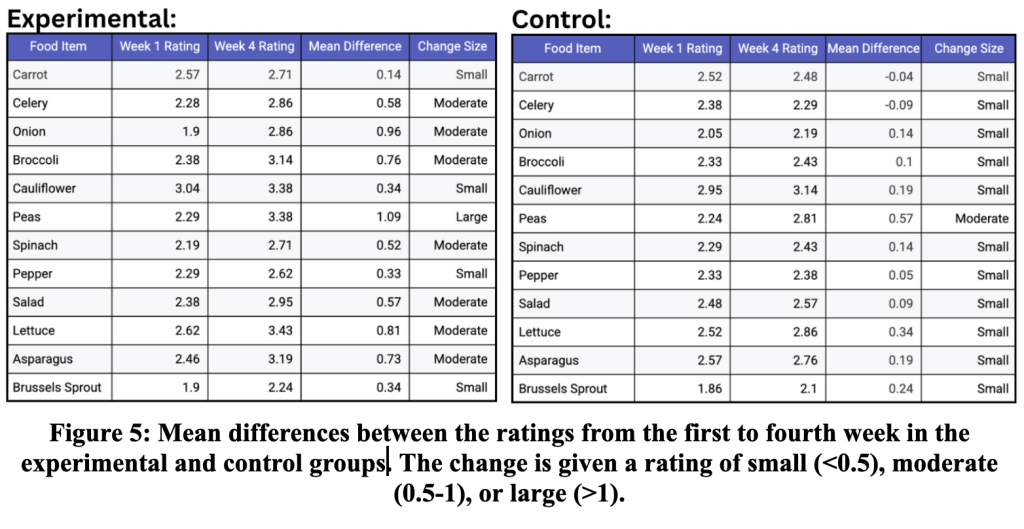

The data were then entered into tables for each week (Figure 2). The first column shows the food items, while the following two columns display the mean ratings of each food for each group. The p-values were determined through statistical significance calculations. Values below 0.05 are statistically significant (highlighted in blue), which means that the difference in ratings between the experimental and control groups is substantial, and a real effect or relationship is being observed rather than random chance. The opposite is true for p-values above 0.05. As seen in the tables, the first two weeks showed few statistically significant differences between the ratings. In contrast, the ratings became more significant by the third and fourth weeks (Figure 2). For example, by week four, eight food items showed significantly higher ratings in the experimental group than in the control group, with a p-value less than 0.05.

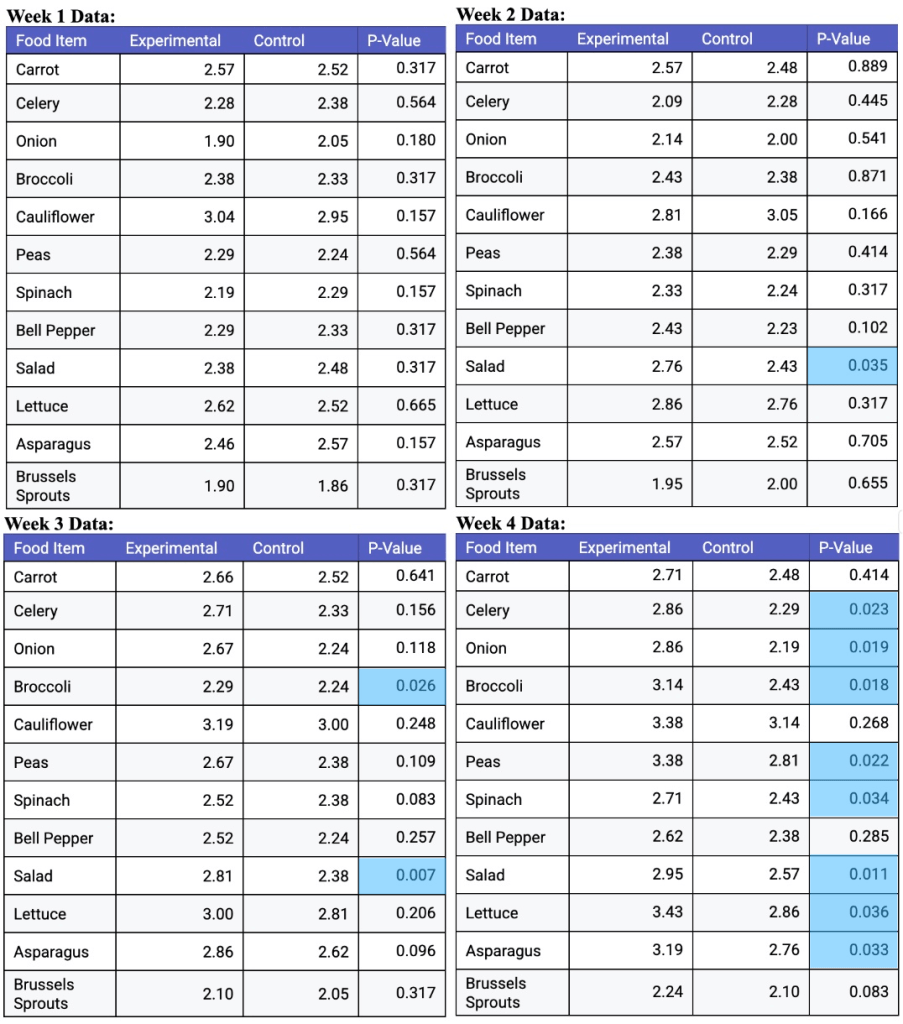

The data was then entered into an SPSS 29.0 program to calculate its significance. Above is an example calculation using the data for the broccoli food item (Figure 3). Lastly, the data was charted to visualize the differences between each group’s scores. In weeks one and two, the scores remained relatively similar, with some differences occurring due to chance, as they have an insignificant statistical difference (Figure 4). By the third and fourth weeks, there were more drastic differences between the ratings of the control and experimental groups, with the experimental ratings becoming much higher than the control ratings, showing that students exposed to the cartoons began developing significantly more positive attitudes towards the foods that were being promoted. For example, the mean Broccoli ratings increased from 2.38 to 3.14 in the experimental group, while the mean ratings in the control group only increased from 2.33 to 2.43. By comparing the mean ratings from the first week to the last, the ratings in the experimental group were larger than the control group, with most of the changes being moderate, while most of the changes in the control were small (Figure 5). Most foods showed an increased rating over the study, while some foods like Brussels sprouts, carrots, and cauliflower remained relatively high or low throughout all four weeks. It’s possible that participants were familiar with these foods and may have already developed an enduring attitude towards them that is hard to alter. In addition, parental eating habits and school lunch programs could also influence the results and how familiar the students were with the foods.

5. Discussion

This study aims to examine how cartoon images can influence children’s healthy eating habits over time and examine their effectiveness in promoting enduring dietary practices. Past research has shown that the use of cartoons in food commercials contributes to the development and maintenance of poor eating habits by promoting and advertising unhealthy products24. This study demonstrates that a similar approach can be used to encourage children to consume vegetables by introducing them to foods they may have previously been hesitant to try. The results of the study show that cartoon images can serve as an effective method to encourage children to try new or unfamiliar foods that are beneficial to their health.

5.1 Relations to Past Research

Past research has shown that cartoon characters are highly effective in influencing children’s preferences and behaviors. Studies by neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists suggest that the mind functions as an associative network of neurons, where ideas are triggered or primed by related stimuli. Thus, encountering an event or object can unconsciously activate or prime related concepts, ideas, and emotions in a person’s memory25. Neurons execute complex chemical and electrical processes that combine to produce memories, sensations, and perceptions. Neuronal synapses form behaviors and memories by strengthening or weakening the connections between neurons based on their frequency of use. When these synapses are reactivated, they create neural circuits that encode specific experiences, enabling memory retrieval and the development of new behaviors26. Therefore, motivating children to try new foods involves forming new neural connections through dietary promotions, while consuming familiar foods can be enhanced by reinforcing existing neural pathways27. This study supports this idea, as over time, students began rating healthy food items higher than when they were originally tested. This change occurred only in the experimental group, where participants were exposed to healthy eating messages through appealing cartoon images.

Additionally, studies conducted by Ambler et al. utilized various brain imaging techniques to examine areas of the brain affected by advertising stimuli and found heightened activity in the frontal and parietal lobes27. The frontal lobe is known to control voluntary movement, problem-solving, executive functions, and planning28. More importantly, it plays a vital role in decision-making. Stimulating this part of the brain with emotionally or cognitively engaging images or information can significantly impact a person’s choice to purchase or use a specific product. Food companies and marketers often leverage this fact to advertise their products and services to the public. As a result, exposing children to engaging cartoons can influence their decision-making, encouraging them to select healthier products. According to Hémar-Nicolas et al., cartoons evoke emotional and psychological responses in children through a persuasive process, enabling them to learn new ideas and behaviors that shape their actions and mindset. Cartoon media endorsing food products can implant the promoted product into children’s minds, allowing them to form associations with the food29. With repeated exposure to cartoon characters in children’s entertainment media, children may perceive them as friends and become more susceptible to their messages. Throughout the study, the vegetable characters on the cards could serve as role models or influencers on the students’ preferences for certain food items as they engaged with them consistently throughout the week. The findings support previous research suggesting that visual cues, such as cartoon characters, can significantly affect children’s food preferences. Further, this study indicates that consistent exposure to cartoons promoting healthy foods has an increasing impact on children’s food choices over time.

5.2 Analysis and Applications of the Study

This study contributes to the growing body of research on approaches to combat the prevailing threat of childhood obesity by demonstrating the potential of cartoons. Past research has shown the impact of cartoon characters, such as brand mascots, on children’s choices, particularly for unhealthy foods16. This study extends this work by focusing on healthy eating behaviors and exploring how using familiar or engaging characters can promote healthier food choices in children. The results show that by week 4, two-thirds of the healthy food items on the surveys had a statistically significant increase in rating of how appealing the participants viewed them. Other food items that did not show a significant difference between the experimental and control groups meant that the cartoon images were not effective in changing the participants’ view of the foods. This could be because they may already enjoy the food, such as cauliflower, which scored relatively high throughout the study, or students have already developed a strong emotional disconnection with a food before the study, such as Brussels sprouts, which were rated low throughout all four weeks. Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that integrating cartoon characters into healthy food marketing campaigns or school nutrition programs could be an effective technique to encourage healthy eating among children. For instance, parents or educators could implement the use of cartoons to familiarize students with healthy vegetables through online apps, posters in school cafetarias, or animated shorts on social media platforms.

5.3 Limitations

Due to the limitations of time and the drawbacks of an experimental design, the study could contain potential errors. First, if the study lasted for a longer period of time, there might be a more significant increase in ratings of the food items. A longer duration could allow for the collection of more data, reducing the effects of random variation and increasing the findings’ reliability. The original sample size was 88 students. However, due to absences during parts of the study, the complete set of data of some students could not be obtained, which lowered the group sizes to 42 students instead of 44. Although this is a minor difference, a smaller sample size decreases the accuracy of the results, making it harder to generalize the findings to the larger population. Additionally, the experimental and control groups may not have been completely exact, as differences between participants from each group make it difficult to isolate the effect of the variable being tested. The resulting data could be due to inherent differences between the groups and not from the effects of the cartoon images. However, replication of the study could reduce such experimental uncertainties. Participants in the experimental group also may not have interacted with the cards throughout the week; whether it was because they didn’t want to or because they lost them, they would not have been exposed to the effects of the cards. Although participants were asked to rank the foods from the survey in general, the images on the survey contained a mixture of both raw and cooked vegetables, which may have affected the appeal of the food. The images of each week’s survey were also different, which could’ve affected participants’ ratings. Furthermore, due to the Hawthorne effect, participants may have changed their behavior due to awareness of being observed by other students nearby or their teacher30. They might have purposefully rated certain items higher or lower to present a positive image of themselves. Due to these possible limitations, further trials and procedures reducing random errors by keeping conditions stable and consistent can help improve the study’s generalizability and reliability.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

The global childhood obesity epidemic can be effectively addressed by combining the promotion of healthy foods through children’s media with other methods, such as improving the quality of school meals, implementing clear nutrition labeling, and reducing unhealthy food advertisements in the media31. Future research should explore how children’s audiovisual entertainment media can most effectively present nutritious foods to improve children’s fruit and vegetable consumption (e.g., the impacts of colors, shapes, or the incorporation of text or audio). Additionally, since efforts to improve children’s diets face numerous challenges from highly profitable food industries and companies that actively promote their unhealthy products through children’s media, future studies could examine, for example, how the number of unhealthy products advertised to children could be restricted and if governmental regulations and policies could be set to regulate children’s media to restrict what is being promoted to them. Further research could include post-experimental surveys examining children’s food choices weeks or months after the study to determine if these improved ratings remained even after they were no longer exposed to the cartoons. This would show whether or not participants developed a long-term positive attitude towards the foods and if they may be more willing to consume the healthy foods in day-to-day life. Other research could study specific aspects of cartoons to better appeal to children, such as the use of color, typography, sound, or the animation style. The cartoon characters in the study may have appealed to some students but not others, as some may think they’re appealing while others may not like them. If participants don’t like the characters, they won’t be as likely to consume the respective vegetable they are promoting. Thus, it is important to investigate how cartoons can be designed to attract and influence the majority of the children watching them. In addition, future replications of this study could measure the results through real-life food consumption or food selection, as opposed to food ratings using pictures.

While food companies are often blamed for encouraging unhealthy diets in children through the use of cartoon characters in their advertisements and product packaging, these techniques can also be used to promote healthier foods like fruits and vegetables (Hémar-Nicolas et al., 2021). Since people’s habits and thought processes formed as children often last throughout their lives, this is the optimal time to establish healthier eating behaviors. Children’s health programs or campaigns should incorporate cartoons as an effective and creative approach to advocate for the importance of a balanced diet, promote healthy eating behaviors, and familiarize children with nutritious foods they might have been afraid to try in the past. While healthy eating cartoons are a promising way to reduce childhood obesity, they should not replace but rather be combined with physical exercise or other traditional healthy eating strategies that have been proven to work in the past. Furthermore, parents should encourage healthier eating habits in their children because they are often the primary influencers of a child’s diet by preparing meals or enforcing household eating rules. Parents can assist children in making healthier food choices, especially if they realize the importance of establishing a long-term healthy diet rather than fulfilling the short-term goal of meeting daily fruit and vegetable intake. By embracing creative methods for improving children’s food familiarity, there will be greater opportunities for the long-term development of healthy food preferences and an improvement in their overall health.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the participants for their contributions to my research and the editors of The National High School Journal of Science for their review and publication of this paper.

Appendix A: Surveys Given to the Participants Each Week

Appendix B: Example Cards Given to the Participants in the Experimental Group

References

- Binder, A., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. The effects of gain- and loss-framed nutritional messages on children’s healthy eating behaviour. Public Health Nutrition, 23(10), 1726–1734. (2020). [↩]

- Daley, S. F., & Balasundaram, P. Obesity in Pediatric Patients. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. (2025). [↩]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. (2024). [↩]

- Benito-Ostolaza, J. M., Echavarri, R., Garcia-Prado, A., & Oses-Eraso, N. Using visual stimuli to promote healthy snack choices among children. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113587. (2021). [↩]

- Cheryl, F. D., Carroll, M. D., & Afful, J. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity Among Children and Adolescents Aged 2–19 Years: United States, 1963–1965 Through 2017–2018. National Center for Health Statistics. (2021). [↩]

- CDC. About Obesity. Obesity. (2024). [↩]

- Bezbaruah, N., & Brunt, A. The Influence of Cartoon Character Advertising on Fruit and Vegetable Preferences of 9- to 11-Year-Old Children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44(5), 438–441. (2012). [↩]

- Hémar-Nicolas, V., Putri Hapsari, H., Angka, S., & Olsen, A. How cartoon characters and claims influence children’s attitude towards a snack vegetable – An explorative cross-cultural comparison between Indonesia and Denmark. Food Quality and Preference, 87, 104031. (2021). [↩]

- Habib, K., Soliman, T. Cartoons’ Effect in Changing Children Mental Response and Behavior. Scientific Research Publishing. Vol. 3, No.9. (2015). [↩]

- Binder, A., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. Experts, peers, or celebrities? The role of different social endorsers on children’s fruit choice. Appetite, 155, 104821. (2020). [↩] [↩]

- Binder, A., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. Experts, peers, or celebrities? The role of different social endorsers on children’s fruit choice. Appetite, 155, 104821. (2020). [↩]

- Binder, A., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. The effects of gain- and loss-framed nutritional messages on children’s healthy eating behaviour. Public Health Nutrition, 23(10), 1726–1734. (2020). [↩]

- Wiedeman, A. M., Black, J. A., Dolle, A. L., Finney, E. J., & Coker, K. L. Factors influencing the impact of aggressive and violent media on children and adolescents. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 191–198. (2015). [↩]

- Kotler, J. A., Schiffman, J. M., & Hanson, K. G. The influence of media characters on children’s food choices. Journal of Health Communication, 17(8), 886–898. (2012). [↩]

- Benito-Ostolaza, J. M., Echavarri, R., Garcia-Prado, A., & Oses-Eraso, N. Using visual stimuli to promote healthy snack choices among children. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113587. (2021). [↩] [↩]

- Tzoutzou, M., Bathrellou, E., & Matalas, A.-L. Food consumption and related messages in animated comic series addressed to children and adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 22(8), 1367–1375. (2019). [↩] [↩]

- Tsochantaridou, A., Sergentanis, T. N., Grammatikopoulou, M. G., Merakou, K., Vassilakou, T., & Kornarou, E. Food Advertisement and Dietary Choices in Adolescents: An Overview of Recent Studies. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 10(3), 442. (2023). [↩]

- Villegas-Navas, V., Montero-Simo, M.-J., & Araque-Padilla, R. A. Investigating the Effects of Non-Branded Foods Placed in Cartoons on Children’s Food Choices through Type of Food, Modality, and Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), Article 24. (2019). [↩] [↩]

- Halford, J. C. G., Gillespie, J., Brown, V., Pontin, E. E., & Dovey, T. M. Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite, 42(2), 221–225. (2004). [↩]

- Knight, K. L. Study/Experimental/Research Design: Much More Than Statistics. Journal of Athletic Training, 45(1), 98–100. (2010). [↩]

- Labaree, R. V. Research Guides: Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Last Word [Research Guide]. (2025). [↩]

- Bezbaruah, N., & Brunt, A. (2012). The Influence of Cartoon Character Advertising on Fruit and Vegetable Preferences of 9- to 11-Year-Old Children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44(5), 438–441. (2012). [↩] [↩]

- NeuroImage. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). [↩]

- Braun-LaTour, K. A., & LaTour, M. S. Assessing the Long-Term Impact of a Consistent Advertising Campaign on Consumer Memory. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 49–61. (2004). [↩]

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. Short-term and Long-term Effects of Violent Media on Aggression in Children and Adults. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(4), 348–352. (2006). [↩]

- Kennedy, M. B. Synaptic Signaling in Learning and Memory. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 8(2), a016824. [↩]

- Ambler, T., Ioannides, A., & Rose, S. Brands on the Brain: Neuro‐Images of Advertising. Business Strategy Review, 11(3), 17–30. (2000). [↩] [↩]

- Brain Map Frontal Lobes | Queensland Health. (2022). [↩]

- Hémar-Nicolas, V., Putri Hapsari, H., Angka, S., & Olsen, A. How cartoon characters and claims influence children’s attitude towards a snack vegetable – An explorative cross-cultural comparison between Indonesia and Denmark. Food Quality and Preference, 87, 104031. (2021). [↩]

- McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277. (2014). [↩]

- Corbett, C., & Walker, C. Catchy cartoons, wayward websites and mobile marketing—Food marketing to children in a global world. Education Review, 21(2), 84–92. (2009). [↩]