Abstract

This research explores whether life that evolved under peak spectra unlike Earth’s could have impaired visual perception under Earth’s light. It examines the interactions between nuclear fusion, a star’s temperature, its color, atmosphere, and vision in life forms, as each type of star emits a unique spectrum of light based on its nuclear fusion and stellar temperature, which could be altered by the orbiting planet’s atmosphere and surface conditions. We combined a literature review with black-body spectral modeling to relate stellar temperature and planetary filtering to likely photoreceptor sensitivity ranges. The findings suggest the peak spectral radiation of red dwarfs (![]() 1 µm at 3000 K), sun-like stars (

1 µm at 3000 K), sun-like stars (![]() 0.48 µm at 6000 K), and blue giants (

0.48 µm at 6000 K), and blue giants (![]() 0.15 µm at 20000 K) do not overlap, which indicates that alien species likely evolve adapted to the dominant light available on their home planets. For example, red dwarf stars mostly emit infrared radiation, and life evolving on orbiting planets may have vision adapted to infrared. These alien life forms may struggle to see on Earth and understanding these adaptations has implications for astrobiology, extraterrestrial life detection, and inter-species communication. By identifying likely visual sensitivity ranges of extraterrestrial organisms, this research can inform which wavelengths to prioritize in detection systems, increasing the likelihood of recognizing alien life and interpreting its signals. The unique contribution of this paper is the integration of stellar radiation modeling with evolution to predict sensory adaptations of extraterrestrial life, providing a new perspective to foresee the visual constraints of alien life.

0.15 µm at 20000 K) do not overlap, which indicates that alien species likely evolve adapted to the dominant light available on their home planets. For example, red dwarf stars mostly emit infrared radiation, and life evolving on orbiting planets may have vision adapted to infrared. These alien life forms may struggle to see on Earth and understanding these adaptations has implications for astrobiology, extraterrestrial life detection, and inter-species communication. By identifying likely visual sensitivity ranges of extraterrestrial organisms, this research can inform which wavelengths to prioritize in detection systems, increasing the likelihood of recognizing alien life and interpreting its signals. The unique contribution of this paper is the integration of stellar radiation modeling with evolution to predict sensory adaptations of extraterrestrial life, providing a new perspective to foresee the visual constraints of alien life.

Keywords: astrobiology, stellar radiation, nuclear fusion, vision evolution, spectral sensitivity, extraterrestrial life, photoreceptor, red dwarfs, blue giants, atmospheric filtering

Introduction

The physics behind stellar radiation is governed by key laws of thermodynamics and electromagnetism. According to Wien’s Law, hotter objects emit light at shorter wavelengths, which make them appear blue. Meanwhile, cooler objects emit light at longer wavelengths, making them appear red. The Stefan Boltzmann Law further explains that a star’s luminosity, which is the total energy it radiates, depends on both its surface area and the fourth power of its temperature. These principles allow for the classification of stars into different types, such as red dwarfs and blue giants, each with distinct and unique fusion pathways, rates, and temperature ranges. The type of light a star emits has significant connections beyond astronomy, as it also influences the evolution of life on its orbiting planets. Earth’s life, for example, evolved under our Sun’s spectrum. As a result, human vision is tuned to detect the wavelengths that are most abundant in our environment. However, on planets orbiting different types of stars, such as red dwarfs, which emit mainly infrared light, or blue giants, which emit ultraviolet radiation, life may have evolved differently and may have different ways of perceiving light. This suggests that alien species could evolve vision which is suited to their star’s spectrum. This paper examines how extraterrestrial life might perceive their environment and planet by exploring the possibility that alien species have vision based on infrared or ultraviolet light, or the abundant light available to their planet. It also examines whether aliens from red dwarf systems might be visually impaired under our Sun’s visible light spectrum, because if their sensory adaptations are outside the range of human or Earth life perception, they might experience Earth differently than us. This research is theoretical and limited to analyzing spectral influence on vision. Since no currently known examples of alien life have been observed, it is impossible to directly study how extraterrestrial life might perceive light, so all hypotheses regarding alien vision are based on Earth life and inference. This study also assumes that alien life would evolve in ways similar to life on Earth, adapting vision to the dominant light in its environment. However, it’s important to recognize that extraterrestrial environments may produce entirely different evolutionary pathways, leading to sensory systems that function in uncommon ways to the organisms residing on Earth. Because our predictions rely on the biology and evolution of life as we know it, there’s a significant level of uncertainty in our predictions about how vision in an alien world might develop. This research deepens our understanding of astrobiology and our quests for extraterrestrial life. It also highlights the challenges in communication and perception that may occur during interaction between organisms from different environments and draws attention to the gaps in our knowledge of interstellar explorations by focusing on four key areas:

1. Stellar classification and nuclear fusion: The physics behind nuclear fusion and stellar radiation.

2. Atmospheric and surface effects: The influence of atmospheres and surfaces on a planet’s dominant light1.

3. Vision evolution and adaptations on Earth: How different animal visions have evolved to adapt to varying light conditions2,3.

4. Spectral non-overlap modeling (Results): Modeling shifts in spectral peaks and relative non-overlaps between different stars.

Methodology

We conducted a literature review and theoretical modeling, incorporating principles from stellar astrophysics, biological adaptation, and atmospheric science to explore how vision may evolve under different stellar radiation environments. Relevant literature was identified through systematic searches in databases such as arXiv, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science, using keywords including ’stellar radiation,’ ’opsin evolution,’ ’planetary atmospheres,’ ’exoplanet habitability,’ and ’nuclear fusion in stars’. The search used a mix of peer-reviewed articles and reputable educational sources. Studies were included if they were published in English and offered empirical or theoretical insights related to light environments or visual adaptations. Sources were excluded if they were non-scientific, outside the scope of the topic, or focused primarily on non-visual sensory systems. Data extracted from selected studies included authors, publication dates, methodologies (e.g. genetic analysis or spectral modeling), key findings (e.g. wavelength sensitivities), and implications for extraterrestrial scenarios. An Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Structure and Evolution4 textbook was also referred to understand the physics behind stellar radiation and evolution. This study gathers information by looking at patterns and themes in different areas instead of performing experiments. It compares ideas and builds on well-known science to draw conclusions. Quality assessment was not formally conducted, as this is a theoretical review, but sources were prioritized based on peer-reviewed status and citation impact. The research uses basic physics laws, such as Wien’s Law (relating temperature to peak emission wavelength) and the Stefan-Boltzmann Law (linking temperature to total radiated energy), to explain how nuclear fusion sustains a star’s equilibrium temperature, thereby influencing its color and radiation spectrum. To understand vision evolution in extraterrestrial environments, this research analyzes biological adaptations in Earth’s organisms and compares planetary atmospheric conditions across the solar system and exoplanets.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework begins with stellar radiation as the primary driver, establishing the initial light spectrum that reaches orbiting celestial bodies. As this light passes through a planet’s atmosphere and interacts with its surface, which filters the light, shaping the dominant wavelengths and colors that ultimately reach the planet’s surface. Vision in organisms evolves enabling them to see in the most useful parts of the spectrum for survival. The framework integrates established physics laws, such as Wien’s displacement and Stefan-Boltzmann, to link stellar properties with biological outcomes across diverse planetary conditions. It suggests that non-overlapping peak spectra from different star types could lead to divergent perceptual systems, highlighting the interconnected role of cosmic and terrestrial factors in shaping life.

Stellar Classification and Fusion Physics

At the core of every star, nuclear fusion acts as its main fuel source that governs its luminosity, temperature, and the characteristics of its light spectrum. Fusion occurs when atomic nuclei collide with each other, with enough energy to overcome the Coulomb barrier, which is the electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged protons in each nucleus. This process releases energy that fuels and sustains a star during its main sequence, also prevents gravitational collapse, and maintains an equilibrium known as hydrostatic equilibrium, which is the balance between gravity and the pressure in a star from fusion.

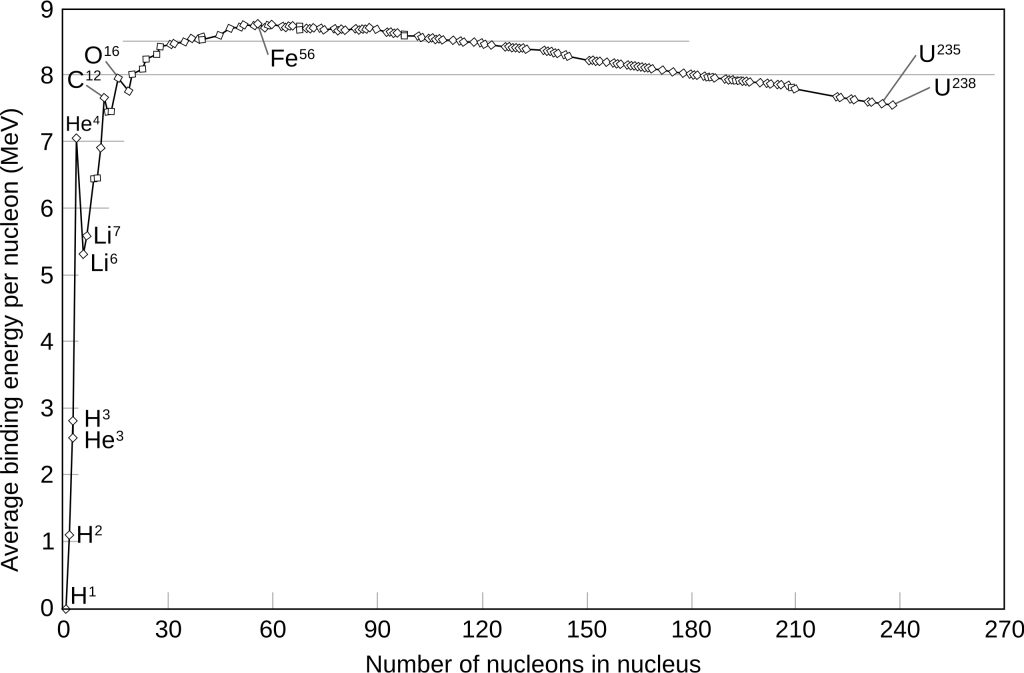

The Coulomb barrier represents the energy required for nuclear fusion to occur, which will vary based on the atomic number of the interacting nuclei. Without nuclear fusion, stars would succumb to their own gravity. The amount of energy released through fusion and the elements produced in a star’s core depend on its nuclear stability and the binding energy curve. Fusion releases energy by forming heavier nuclei up to iron (Fe-56), which has the highest nuclear binding energy, which makes it the most stable element. In the elements beyond iron, fusion requires much more energy than it will produce, which leads to the collapse of high mass stars and triggering supernovae. This limit determines a star’s life cycle and the types of elements that it releases into space.

Figure 3: Binding energy curve, as shown in6

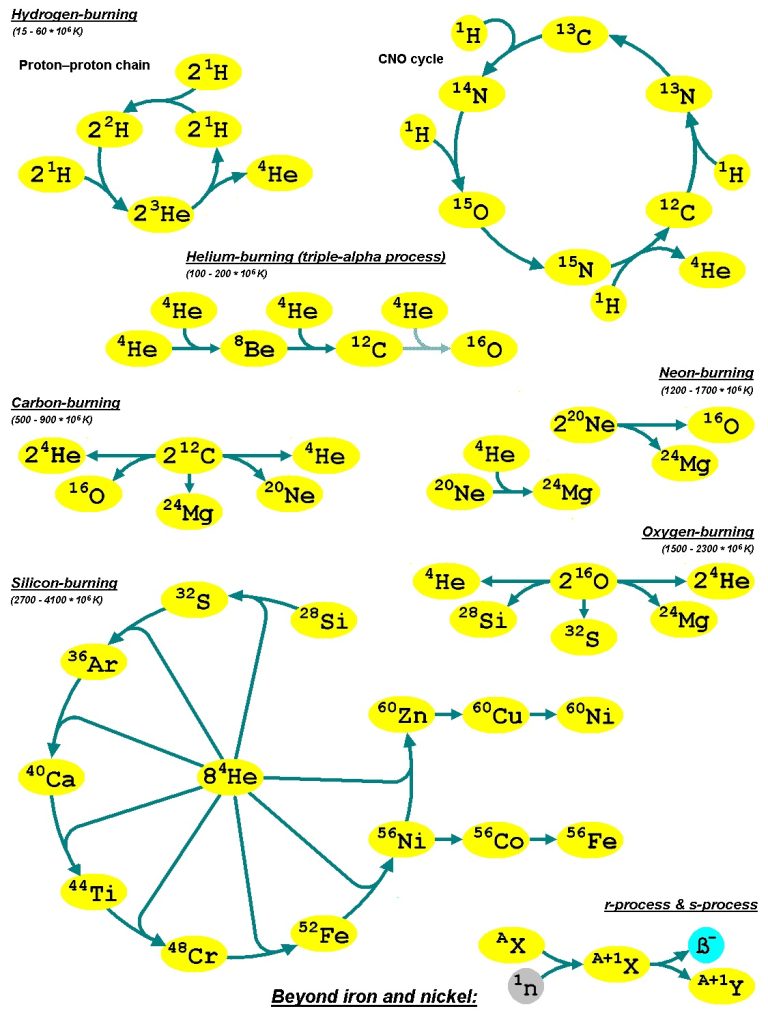

Throughout their lifetimes, stars slowly progress through the nuclear burning stages, where different elements fuse based on the core temperature. Low mass stars, such as red dwarfs ( 3000 K), fuse hydrogen into helium at a slow rate and can burn fuel for trillions of years. Medium mass stars, like our own Sun ( 6000 K), undergo hydrogen to helium fusion for most of their lives before transitioning to the helium burning stars, where helium nuclei fuse into carbon and oxygen, and eventually they become white dwarfs. Blue giants ( 15000-30000 K) experience multiple fusion stages, as they progress from hydrogen to helium to carbon to oxygen to neon to silicon and then finally to iron. Once iron forms, the fusion process stops, and the star undergoes a supernova explosion, which can result in either a neutron star or a black hole. The extremely short main-sequence life times of massive blue giants, ranging from 1–10 million years and 2.5–3 million years for very massive stars, constrain the time available for planetary formation and the evolution of biology in their habit able zones, unlike the 20–60 million year timescales typical for lower-mass stars.

Low temperature stars engage in proton-proton (p-p) chain, as the temperature increases, the fusion shifts to CNO (Carbon – Nitrogen – Oxygen) cycle, then the triple alpha process, followed by carbon and oxygen fusion, and eventually silicon burning.

Figure 5 shows the important fusion reactions. The graph highlights how hydrogen fusion occurs at lower temperatures and releases more energy, while reactions with heavier elements like silicon require higher temperatures and release less energy. This supports the idea that energy output declines as stars evolve, and eventually leads to collapse when iron forms. The temperature of a star is directly linked to its fusion process, which determines the color and spectrum of light it emits.

Figure 5: Nuclear burning, as shown in 8

A star’s metallicity, the fraction of elements heavier than helium, influences its emitted spectrum in addition to its mass and temperature. Stars with a high metallicity display more and stronger absorption lines that can alter the spectrum’s shape, and in some cases affect the star’s appearance in regards to color. Stars with a low metallicity show weaker absorption features, with spectra closer to an ideal blackbody.

Physics Laws

Wien’s Displacement Law

According to Wien’s displacement law, the wavelength at which a blackbody emits the most radiation becomes shorter as its temperature increases.

(1) ![]()

T is the absolute temperature

b is a constant of proportionality called Wien’s displacement constant, equal to

(2) ![]()

The Sun’s temperature is approximately 6000K, so the peak on earth is ![]() .

.

Human vision is adapted to our Sun’s spectrum with peak sensitivity near its peak wavelength, which is around 500 nm.

Stefan-Boltzmann Law & Luminosity

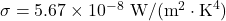

According to Stefan-Boltzmann Law, star’s luminosity, or total power output, depends on both its surface area and temperature, and can be calculated by combining the Stefan-Boltzmann law with the formula for the surface area of a sphere.

(3) ![]()

is the luminosity

is the luminosity is the radius of the star

is the radius of the star is the surface temperature of the star

is the surface temperature of the star is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant

According to Wien’s Law, hotter stars radiate energy at shorter wavelengths, appearing blue, while cooler stars radiate at longer wavelengths, appearing red. The Stefan-Boltzmann Law further states that a star’s luminosity (which is the total energy output) increases with the fourth power of its temperature, explaining why blue giants shine very intensely. This relationship allows for stellar classification based on temperature and dominant radiation type:

- Red Dwarfs (M-type,

3000 K): Emit mostly infrared radiation.

3000 K): Emit mostly infrared radiation. - Sun like Stars (G-type,

6000 K): Emit mostly visible light.

6000 K): Emit mostly visible light. - Blue Giants (O/B-type,

15000–30000 K): Emit mostly ultraviolet radiation.

15000–30000 K): Emit mostly ultraviolet radiation.

Atmospheric and Surface Effects

Beyond a star’s light emission, the planet’s distance from the star, its atmospheric conditions, and surface conditions also influence the dominant wavelengths of light on the planet. When light enters the atmosphere of a celestial body, it is absorbed and scattered. Absorption occurs when gases or particles in the atmosphere remove parts of the spectrum. Scattering occurs when the atmosphere redirects light in different directions. Absorption and scattering may vary depending on the type of atmosphere, such as thick, planetary atmospheres in hydrostatic equilibrium versus thin, expanding cometary comae. There are two main types of scattering: molecular scattering (also known as Rayleigh scattering) and aerosol scattering (also known as Mie scattering). Rayleigh scattering occurs when light hits small molecules in the air, and is more effective on shorter wavelengths. For particles much smaller than the wavelength, the Rayleigh scattering cross-section scales as ![]() , so shorter (bluer) wavelengths are scattered more strongly. Aerosol scattering occurs when light hits larger particles like dust or water droplets, tending to send light in a particular direction and causing noticeable bright patterns based on the viewing angle. Although every body in our solar system receives light from the Sun, the dominant light conditions on each one vary greatly due to these atmospheric effects. Here are some examples:

, so shorter (bluer) wavelengths are scattered more strongly. Aerosol scattering occurs when light hits larger particles like dust or water droplets, tending to send light in a particular direction and causing noticeable bright patterns based on the viewing angle. Although every body in our solar system receives light from the Sun, the dominant light conditions on each one vary greatly due to these atmospheric effects. Here are some examples:

• Earth: Rayleigh scattering causes the sky to appear blue, as nitrogen and oxygen scatter short wavelength light more. Additionally, Earth’s ozone layer (O) absorbs solar UV over a wave length range of about 200–300 nm.9

• Titan: The thick methane atmosphere absorbs shorter wavelengths and transmits in the infrared, making surface light appear dim and reddish.

• Venus: The dense CO2 and sulfur-rich atmosphere heavily absorbs both UV and visible light, with only narrow IR windows (600–1000 nm) offering consistent surface illumination.

• Hydrogen-rich exoplanets (e.g. sub-Neptunes or mini-Neptunes): These show strong transmission in the near-IR (700–1000+ nm), especially if cloud decks are sparse.

• TRAPPIST-1e: Although atmospheric measurements are still limited, so 3D climate models (Global Climate Models, GCMs) are used to explore the possible atmospheres in TRAPPIST-1e. Models propose that TRAPPIST-1e could have a thin, oxygen-rich or CO-dominated atmosphere. If it is Earth-like, Rayleigh scattering could dominate and play a major role in shaping the incoming light. If it is Venus-like, absorption of UV and visible light could shift the spectrum into infrared. This variability spotlights how planetary atmospheres outside our solar system may follow similar scattering and filtering principles.10

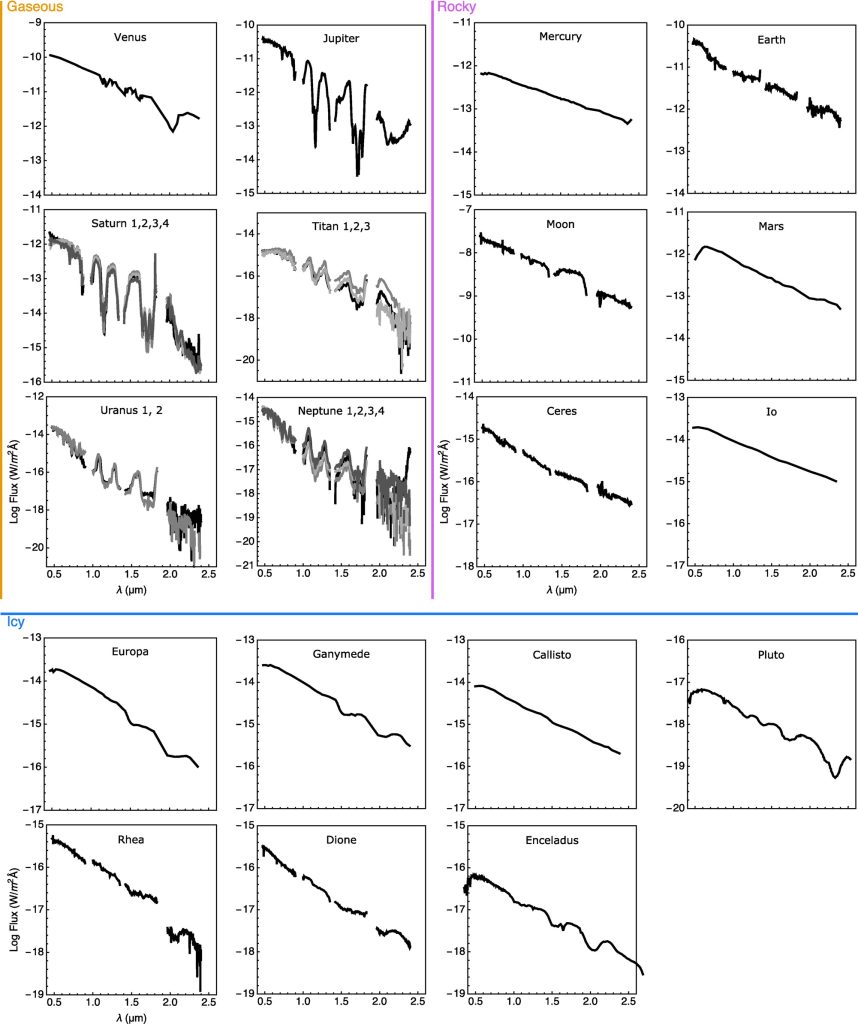

In addition to atmospheric absorption and scattering, the surface composition of planets reflects light in specific ways. For instance, rocks or ice may reflect certain colors, further influencing the dominant light on the planet. Figure 6 shows log monochromatic flux density (energy per unit area, time, and wavelength) versus wavelength for various celestial bodies. It illustrates differences in intensity levels and spectral shapes between gaseous, icy, and rocky objects, highlighting how composition filters and reflects light.1

Figure 6: Composition filtering and reflection, as shown in1 [astro-ph.EP]

Vision Evolution and Adaptations on Earth

In humans, the process of converting light into signals that the brain can interpret is called phototrans duction, which occurs in the retina of the eye, which is sensitive to light. The retina has photoreceptors which are specialized cells that detect light. There are two types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are highly sensitive to light and are responsible for vision in low-light or nighttime conditions, but they cannot detect color. Cones are less sensitive and function best in bright light, which allows humans to see color and fine details.

Both rods and cones contain a group of light sensitive proteins called opsins, which act as the molecular sensors that detect light by binding to a molecule called retinal forming visual pigments. Different types of opsins are tuned to specific wave lengths of light. For example, rhodopsin (the opsin in rods) is sensitive to a broad range of dim light, while cone opsins (short-wavelength S-opsin for blue, medium M-opsin for green, and long L-opsin for red) enable color vision in brighter conditions

Figure 7: Section through the human eye, as shown in11

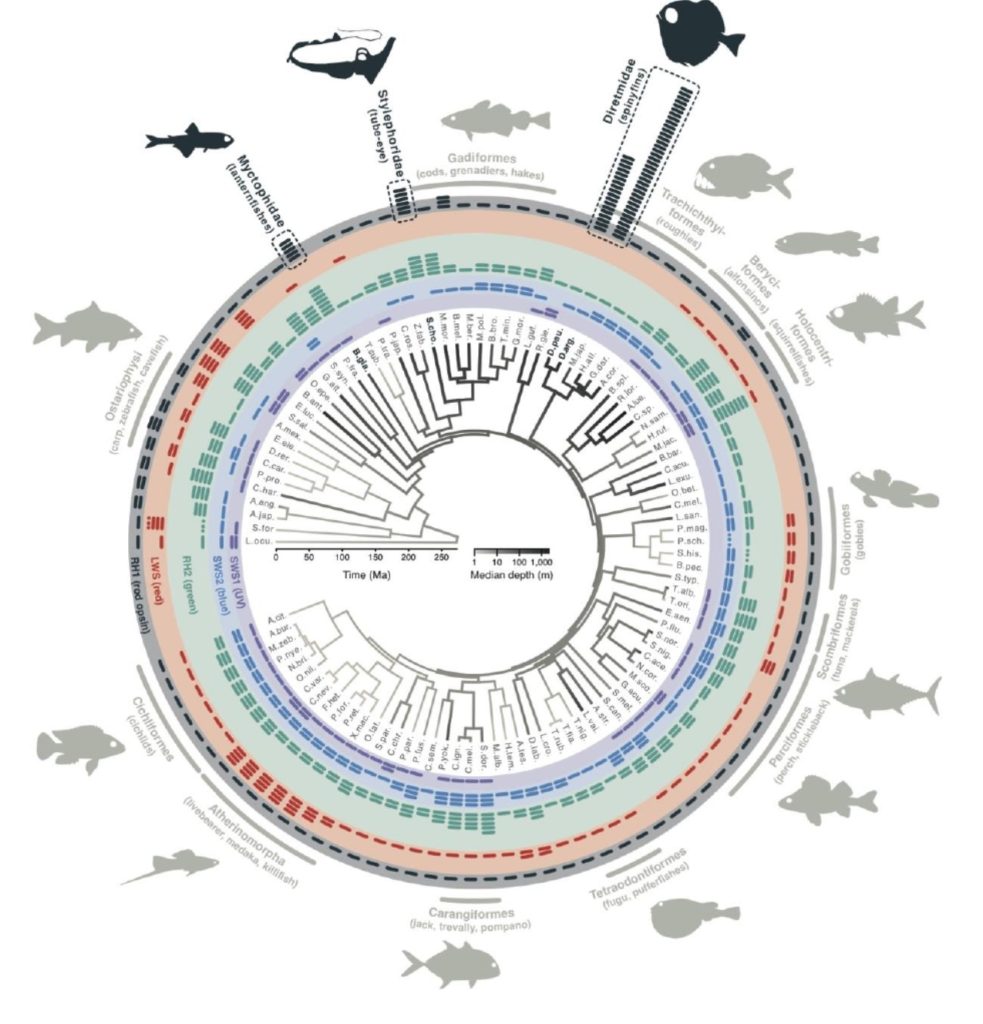

On Earth, biological vision evolved withphotoreceptors optimized to match the Sun’s peak spectrum in the visible light range (approximately 400–700 nm). This adaptation allows them to navigate and survive more effectively in their environments . However, certain Earth organisms, such as deep-sea creatures, are exposed to minimal or altered light. In these dim, blue-green-dominated conditions, many species have developed unique visual adaptations that differ from human vision. For instance, a study of deep-sea fishes revealed that teleosts, bony fishes, possess more visual opsin genes than other vertebrates, and are typically more sensitive to blue-green light prevalent in aquatic environments3. Researchers reconstructed opsin gene loci in 100 teleost species and one non-teleost outgroup, and their findings suggest Teleost fish have evolved different visual systems via opsin genes to match the specific colors of light available in their habitats, especially depending on how deep in the ocean they live. Teleost fishes living in shallow water are more sensitive to visible light including UV and red visible light, and Teleost fishes living in deeper waters are more sensitive to blue and green light.3

This pattern of opsin sensitivity is not exclusive to teleosts, but reflects a bigger trend in the animal kingdom.

Dataset in Table 1 shows how spectral tuning varies between species of fish and within lineages through gene duplications and functional divergence. It highlights the importance of environmental lighting conditions in shaping the evolution of vision. This diversity in opsin allows organisms to adapt their vision to different environments, whether by detecting ultraviolet, blue-green, or longer red-shifted wavelengths.

| Fish | Spectral sensitivity range of Rh2 opsins (nm)2 |

|---|---|

| Zebrafish | 467506 |

| Medaka | 452492 |

| Guppy | 476516 |

| Cichlid | 484529 |

Experimentally measured peak spectral sensitivities (λmax) of Rh2 opsins across zebrafish, medaka, guppy, and cichlid, as shown in13

Similarly, nocturnal animals like vipers have adapted on Earth differently for survival in darkness. These animals developed pit organs that use both thermal and visual imaging capable of detecting infrared radiation. These pit organs act like thermal cameras, as they detect objects hotter than the surrounding environment. The pit organs contain a thin membrane similar to an antenna, that can absorb IR causing it to heat up, and the heat produced is converted into electrical signals that the brain can process to create thermal images. This visual system gives snakes a major advantage in hunting their prey and avoiding predators, especially in conditions with minimal light.2

Spectral Non-Overlap Hypothesis

The hypothesis that there can be spectral non-overlap in the peak spectrum between stars suggests that an extraterrestrial species, whose vision evolved under a different stellar spectrum, could be visually impaired on Earth due to the differences in the type of light their home star emits. Specifically, aliens from environments rich in infrared, which include planets around red dwarfs, might not perceive visible light. Aliens from ultraviolet rich environments, which include planets around blue giants, might not see in the red or infrared range. Although red dwarfs emit most of their energy in infrared, they still produce some visible light during stellar flares, in which visible and ultraviolet output spikes. Blue giants peak in the ultraviolet range, but also emit visible light that may be detected by human vision. These phenomena create some spectral overlap between different stellar types. However, flares can create temporary spectral overlap, but this does not necessarily result in organisms to fully adapt to another star’s light range. The need to evolve depends on the consistency and intensity of available light, not just occasional events. For vision to shift significantly toward a given wavelength range, sustained and consistent exposure is needed and more influential to vision adaptation than brief and irregular bursts.

Model Setup: Spectral Radiance Using Planck’s Law

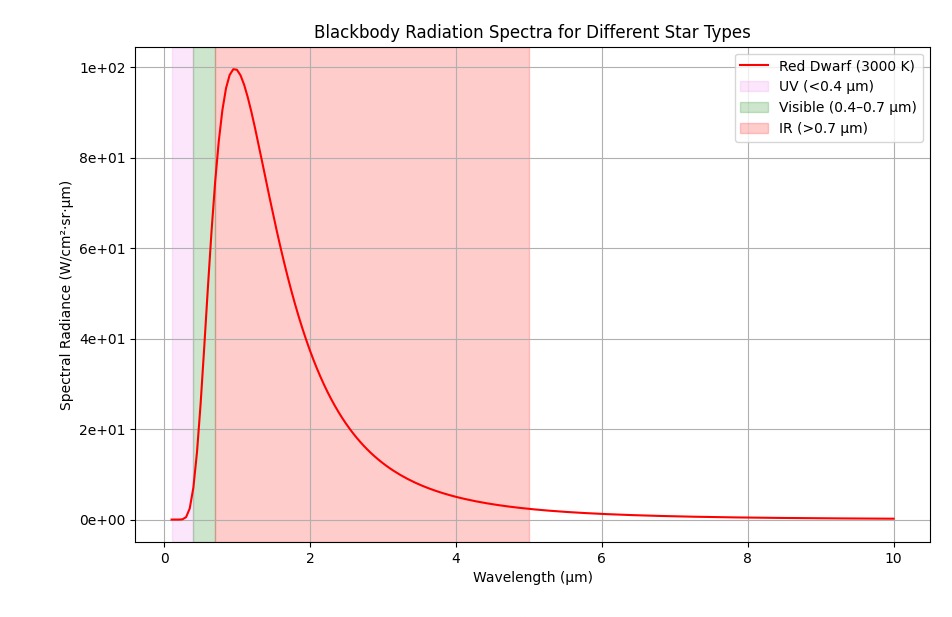

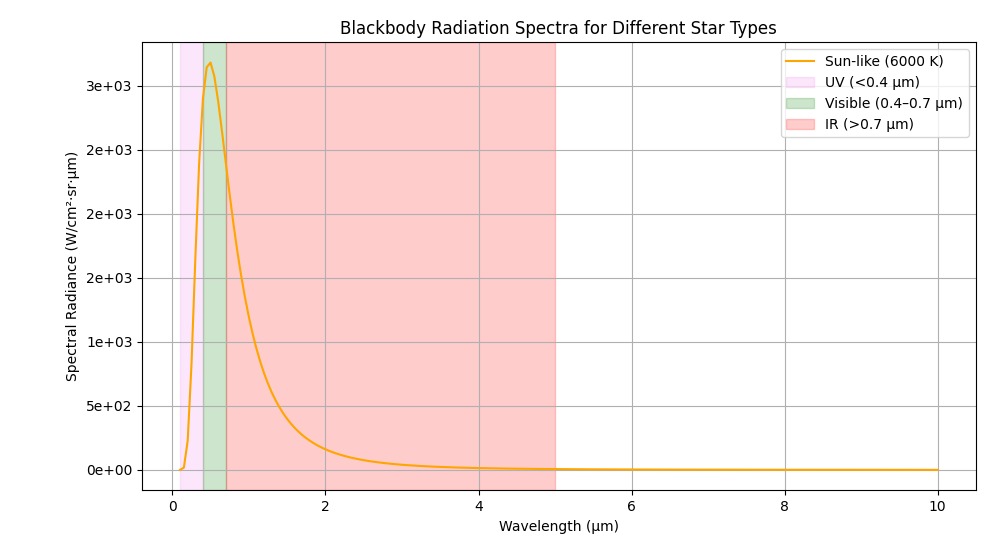

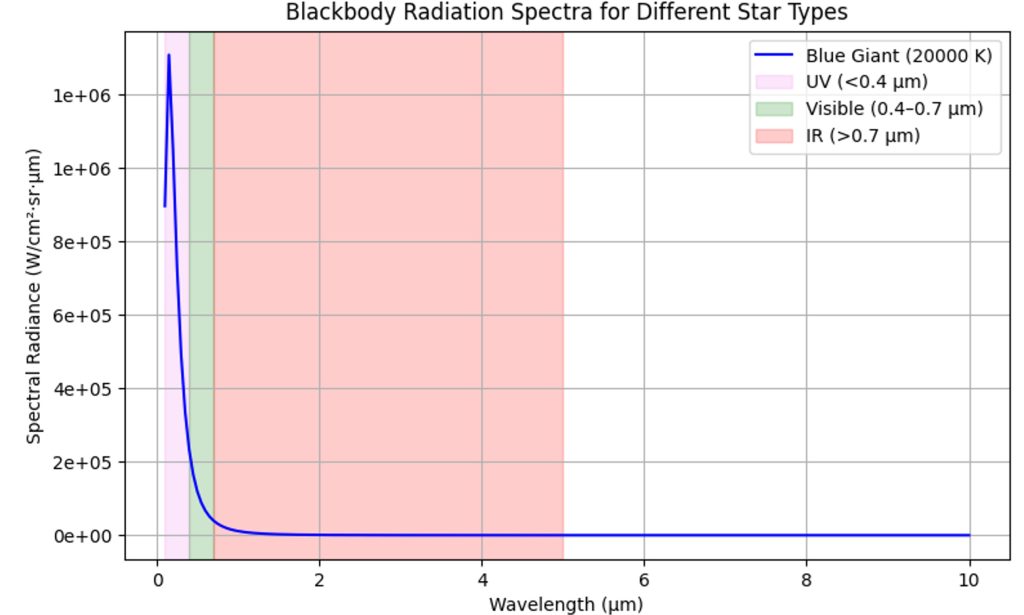

To test the hypothesis that alien visions may be incompatible with Earth’s visual light spectrum, we modeled the spectral radiance of three different stellar types using Planck’s Law using python. The Python code calculates and plots blackbody radiation curves for a red dwarf (3000 K), a sun-like star (6000 K), and a blue giant (20000 K).

Planck’s Law

Planck’s law describes the spectral intensity of radiation emitted by a blackbody as a function of wavelength and temperature. Stars emit light similar to a blackbody, so we can use Planck’s law to model the star’s spectrum, revealing its temperature and color.

- h: Planck’s constant

- c: Speed of light

- k: Boltzmann constant

Code Implementation

We numerically implemented Planck’s Law in Python to compute and visualize the spectral radiance of different stars over the wavelength range of 0.1 µm to 10 µm (UV to near-infrared). Each curve represents the intensity distribution of radiation emitted by a star at a specific temperature. All curve representations assume vacuum and no atmospheric filtering. The full source code and plotting scripts are available in stellar radiation.py.

Model Validation

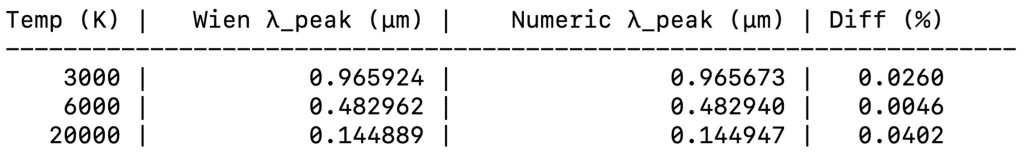

To validate our model, we developed another Python script which calculates and compares Planck’s Law peak spectral radiance with Wien’s Law peak spectral radiance for the different star temperatures to verify that they match. The full source code is available in plancks vs wiens.py. Results show a close match with minimal difference.

Key Findings

Red Dwarf (3000 K)

The peak of the spectral curve lies at around 1 µm, in the infrared region, so most of the emitted radiation is invisible to the human eye. If life evolved under a red dwarf, their vision would most likely be tuned to infrared, and they might have reduced sensitivity to the visible spectrum on Earth.

Sun-like Star (6000 K)

The spectral peak is around 0.48 µm, which aligns with Earth’s visible light, and human eyes are adapted to this peak, confirming that vision on Earth evolved to match our Sun’s radiation.

Blue Giant (20000 K)

This star peaks at around 0.15 µm, in the ultraviolet range, and life evolving under this radiation would have photoreceptors sensitive to UV, and might not detect longer visible or IR wavelengths.

Implications of Stellar Light Differences for Alien Visual Perception on Earth

The results support the spectral non-overlap hypothesis, which states that biological vision is tuned to the dominant radiation available in an organism’s environment. Therefore, extraterrestrial life forms adapted to other stars, such as red dwarfs or blue giants, could experience Earth’s visual light environment as too dim, too bright, or entirely out of range.

Discussion

This research assumes that extraterrestrial life resides in a system with a singular sun-like star. However, universe has many variations of systems that need to be further explored.

Binary Star Systems

In binary star systems, different light sources from the two stars could lead to more complex spectral environments, as the light intensity and spectrum can vary14. This adds a challenge for modeling alien vision, as

it must also accommodate the blend of spectral ranges of two different stars. Life could evolve with visual systems that are able to adapt between spectral ranges depending on which star dominates the sky. However, it is also possible that only one star’s radiation dominates due to atmospheric filtering.

Tidal Locking

Some planets are tidally locked to their star, where the same side is always facing their star. On these planets, the day side receives constant illumination from the same angle, while the night side receives no direct light from its star. A narrow terminator region experiences a constant dim “twilight”. These stable and extreme zones of light could cause the evolution of vision systems of organisms adapted to constant spectral conditions. Many potentially habitable exoplanets orbit red dwarfs, where close orbital distances make tidal locking likely. The day side would be permanently exposed to infrared light, the night side would receive no direct light, and the twilight zone would have constant, dim light. Each zone could result in different visual adaptations, with little overlap to human vision.

Lateral Inhibition

Lateral inhibition or neural computation occurs in the retina. Cells connected to photoreceptors are involved in this process that enhances contrast and helps find boundaries of visuals. It helps brain focus on the core light intensity of a visual, and may evolve very differently for organisms that are exposed to dim light.

Due to the limitations of this study there are several avenues for future work: exploring binary systems, systems with variable stars, tidal locking, and how alien photosynthetic organisms may evolve to non-visible light.

Conclusion

This study explores the connection between nuclear fusion, stellar radiation, and the evolution of biological vision, proposing that extraterrestrial organisms may present reduced visual effectiveness because their eyes are adapted to a different kind of light than what our Sun provides. The objectives to analyze stellar classification, atmospheric effects, vision evolution, and spectral non-overlap were achieved through literature review and modeling, confirming non overlapping spectral peaks (e.g. ![]() 1 µm for red dwarfs,

1 µm for red dwarfs, ![]() 0.48 µm for sun-like stars,

0.48 µm for sun-like stars, ![]() 0.15 µm for blue giants). Limited exoplanet atmosphere data constrained detailed modeling. This variation in spectral peaks indicates the potential diversity of sensory adaptations across the universe and raises new questions in astrobiology, such as how humans might detect and interact with life that perceives the universe in completely different ways. Understanding these limitations and differences is essential for the future of astrobiological exploration, communication with extraterrestrial life, and the search for habitable exoplanets. We encourage the community to develop interdisciplinary experiments to test these predictions.

0.15 µm for blue giants). Limited exoplanet atmosphere data constrained detailed modeling. This variation in spectral peaks indicates the potential diversity of sensory adaptations across the universe and raises new questions in astrobiology, such as how humans might detect and interact with life that perceives the universe in completely different ways. Understanding these limitations and differences is essential for the future of astrobiological exploration, communication with extraterrestrial life, and the search for habitable exoplanets. We encourage the community to develop interdisciplinary experiments to test these predictions.

References

- Madden, J. H., & Kaltenegger, L. (2018). A catalog of spectra, albedos, and colors of solar system bodies for exoplanet comparison. Astrobiology, 18(12), 1559–1573. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1763 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Darbaniyan, F., Mozaffari, K., Liu, L., & Sharma, P. (2021). Soft matter mechanics and the mechanisms underpinning the infrared vision of snakes. Matter, 4(1), 241–252. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2020.09.023 [↩] [↩]

- Musilova, Z., Cortesi, F., Matschiner, M., Davies, W. I. L., Patel, J. S., Stieb, S. M., de Busserolles, F., Malmstrøm, M., Tørresen, O. K., Brown, C. J., Mountford, J. K., Hanel, R., Stenkamp, D. L., Jakobsen, K. S., Carleton, K. L., Jentoft, S., Marshall, N. J., & Salzburger, W. (2019). Vision using multiple distinct rod opsins in deep-sea fishes. Science, 364(6440), 588–592. doi:10.1126/science.aav4632 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Prialnik, D. (2009). An introduction to the theory of stellar structure and evolution (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press [↩]

- Ongena, J. (2022). Fusion: A true challenge for an enormous reward. EPJ Web of Conferences, 268, 00011. doi:10.1051/epjconf/202226800011 [↩]

- Fastfission. (2007). Binding energy curve – common isotopes. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binding_energy_curve_-_common_isotopes.svg [↩]

- RJHall. (2008). Stellar nucleosynthesis energy generation diagram. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nuclear_energy_generation.svg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 [↩]

- Qniemiec. (2020). Creation of elements beyond carbon (carbon burning, neon burning, oxygen burning and silicon burning). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kernfusionen0_en.png. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 [↩]

- Gorshelev, V., Serdyuchenko, A., Weber, M., Chehade, W., & Burrows, J. P. (2014). High spectral resolution ozone absorption cross-sections – part 1: Measurements, data analysis and comparison with previous measurements around 293 K. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 7(2), 609–624. doi:10.5194/amt-7-609-2014 [↩]

- Fauchez, T. J., Turbet, M., Wolf, E. T., Boutle, I., Way, M. J., Del Genio, A. D., Mayne, N. J., Tsigaridis, K., Kopparapu, R. K., Yang, J., Forget, F., Mandell, A., & Domagal-Goldman, S. D. (2020). Trappist-1 habitable atmosphere intercomparison (THAI): Motivations and protocol version 1.0. Geoscientific Model Development, 13(2), 707–716. doi:10.5194/gmd-13-707-2020 [↩]

- University of Utah. Webvision: The organization of the retina and visual system. http://webvision.med.utah.edu/. Figure 1.1. Available at https://webvision.med.utah.edu/book/part-i-foundations/simple-anatomy-of-the-retina/. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Accessed 21 Mar. 2025 [↩]

- Blume, C., Garbazza, C., & Spitschan, M. (2019). Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie, 23, 147–156. doi:10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x [↩]

- Patel, J. S., Brown, C. J., Ytreberg, F. M., & Stenkamp, R. L. (2018). Predicting peak spectral sensitivities of vertebrate cone visual pigments using atomistic molecular simulations. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(1), e1005974. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005974 [↩]

- Eggl, S., Georgakarakos, N., & Pilat-Lohinger, E. (2020). Habitable zones in binary star systems: A zoology. Galaxies, 8(3). doi:10.3390/galaxies8030065 [↩]