Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have emerged as effective therapeutic agents that treat both type 2 diabetes and obesity. The glycemic control drugs semaglutide and liraglutide proved effective for weight reduction in clinical research, where semaglutide reduced body weight by 15% in certain patient groups. The therapeutic benefits of GLP-1 drugs are limited by their high cost and inconsistent insurance coverage methods. It also assesses the real-world compliance with discontinuation rates still high in regards to expense, gastrointestinal tolerability, and injection burden. This study analyzes GLP-1 receptor agonist functioning mechanisms, plus effectiveness data and socioeconomic obstacles within weight loss treatment. There are global disparities that are discussed, namely that low- and middle-income countries can have limited access to them, and that there is a great variation in the extent of public reimbursement between the high-income countries. The current study uses therapeutic trial results in combination with pricing evaluations and healthcare records to demonstrate unequal patient access to these medications. The monthly prescription price of Wegovy reached more than $1300 on average in the United States during 2023 thus limiting patient access for those without insurance or low incomes. The high prevalence of obesity at 40% in the U.S. population becomes even more serious because of limited access to treatment. This study endorses three main solutions, which involve governmental policy rule changes and clear medication pricing rules alongside support for cost-effective generic alternatives. The future drugs, such as dual and triple agonists, such as tirzepatide and retatrutide, may be the next trend of obesity pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: Semaglutide; Obesity; GLP-1; Glycemic control; Diabetes

Introduction

The development of obesity results from multiple disease factors that include genetics, together with environmental elements and behavioral influences, and metabolic changes. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) identifies obesity as a worldwide epidemic affecting more than 650 million adult individualsWHO, Obesity and overweight.1. Obesity creates substantial risk for patients to develop type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as cancers and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and obstructive sleep apnea. Many individuals who adopt traditional weight management methods, such as diet and exercise with behavioral therapy, achieve only limited and temporary results with their weight loss efforts. The worldwide increase in morbidity and mortality related to obesity has led to a reassessment of the classical models of its treatment, which creates the necessity of the creation of a balance of biological and socioeconomic aspects of the treatment of obesity.

Recent data are pointing toward obesity as being a chronic neuroendocrine condition and not solely a behavioral problem that requires chronic, indefinite medical care. Innovations in the research of the gut-brain axis and appetite mechanisms have resulted in the invention of GLP-1 receptor agonists, such agents which are able to affect not only glycemic control, but also have central influences on satiety and energy intake. These medications have demonstrated impressive performance of clinically significant weight loss through activating many regulatory pathways2‘3. Nevertheless, the popularity of GLP-1 treatments has been hindered by extreme prices, variable insurance coverage, and the healthcare disparity system. Although they are included in current treatment recommendations, not all patients, especially those of low income or underprivileged groups, can afford to take them3.

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists?

The gut produces GLP-1 through L-cells residing mainly in the ileum and colon regions of the small intestine. Through its action as a key homeostasis controller GLP-1 enhances pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion based on blood glucose levels. This hormone blocks glucagon release to reduce hepatic glucose production and reduces stomach emptying, thus causing delayed food absorption and extended feelings of fullness4. The hormone GLP-1 breaks down quickly after injection because dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) degrades it within two minutes. Pharmaceutical companies have developed resistant GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, and exenatide, which now survive enzymatic breaking down for extended periods spanning from hours to days.5 These drugs target the pancreatic islet and gastrointestinal tract through G protein–coupled receptors known as GLP-1R while additional expression of these receptors exists throughout the heart, kidney, and brain.

The development of tirzepatide represents a new class of incretin inhibitors that enhance receptor agonist therapy by simultaneously activating GLP-1/GIP pathways, thus delivering improved metabolic outcomes6.

Central and peripheral mechanisms of action

GLP-1 receptor agonists work through two distinct pathways, which include central and peripheral actions. The activation of GLP-1R receptors in pancreatic β-cells functions to boost cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, which enhances insulin exocytosis when blood glucose levels become elevated. The activation of GLP-1R in α-cells works simultaneously to decrease glucagon secretion. These medications in the gastrointestinal tract postpone gastric emptying, resulting in slower glucose absorption and controlling high glucose spikes after eating. These receptors improve lipid metabolism along with lowering inflammatory responses, which commonly occur during obesity7.

Within the central nervous system, GLP-1R displays high-density distribution throughout the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) as well as paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and brainstem nuclei consisting of area postrema and nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS)8. These neural pathways increase feelings of satiety and decrease appetite by stimulating pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) brain cells and simultaneously blocking neuropeptide Y (NPY)/AgRP neurons.

Present-day studies show that the GLP-1 analogs activate the mesolimbic reward system which alters food-related reward signals and decreases hedonic eating habits.

Methodology

The review targeted the synthesis of randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence, real-life effectiveness, cost, coverage, and policy analyses applicable to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and newer incretin-based weight management compounds. This study did targeted searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ClinicalTrials.gov, regulatory authority web pages (FDA, EMA), health-technology assessment agencies (NICE, CADTH), and large pharmacy price databases (GoodRx, manufacturer public pages). Articles about GLP-1, semaglutide, tirzepatide, retatrutide, weight loss, obesity, STEP trial, SURMOUNT, SCALE, real-world adherence, cost, and coverage were searched using combinations of terms: GLP-1, semaglutide, tirzepatide, retatrutride, weight loss, obesity, STEP trial, SURMOUNT, SCALE, real-world adherence, cost, and coverage. Relevance screening: Titles and abstracts were filtered; full texts were accessed in RCTs, systematic reviews, real-world cohort studies, and policy/cost-effectiveness reports. Our focus was on primary trial reports, regulatory labels, and high-quality meta-analyses and government/payer reports. It is not a systematic review, and thus no formal PRISMA flow chart was created. We present here the selection methodology and inclusion criteria to allow the readers to evaluate comprehensiveness and possible selection bias.

PRISMA-style selection paragraph (narrative) – Among the above-described searches, we found randomized trials that tested GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide) or oral semaglutide preparations and major real-world, cost, and policy reports. Duplicates were eliminated, titles and abstracts were filtered out based on relevance to therapeutic efficacy, safety, cost, coverage, or access, and full text was reviewed based on meeting inclusion criteria (adult populations, primary endpoints related to weight change or a clinically relevant metabolic outcome, or robust cost/payer analysis). Information on the best reports was collected and qualitatively synthesized.

Pricing methods

The cost information was obtained from GoodRx retail price lists and Drugs.com9‘10. (last accessed 15 September 2025). The 2025 U.S. dollar list prices are presented in the form of manufacturer list prices. Monthly costs were computed by x12 of the price every year. There was no currency conversions required; conversion of older price data to 2025 values was done using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI-U inflation calculator.

Discussion

Efficacy of GLP-1 agonists in weight loss

Clinical trials evidence

The STEP 1 study involving 1900 adults with obesity or overweight reported that weekly doses of Semaglutide 2.4 mg led to a 14.9% mean weight reduction over 68 weeks11. The SCALE trial found that patients taking liraglutide (3.0 mg daily) experienced an 8% weight reduction, together with measurable improvements in cardiometabolic health markers12. Further STEP trials established the successful weight loss outcomes of semaglutide therapy in diabetic patients who received intensive behavioral modification. Weight regain occurred in STEP 4 after semaglutide therapy ended, thus revealing the necessity for sustained patient treatment. Tirzepatide, administered weekly at 15 mg, demonstrated weight reduction up to 22.5%, which exceeded the effectiveness of all prior available medications according to a recent trial11. Patients receive better clinical outcomes and fewer adverse effects from GLP-1–based therapy treatments when compared to existing medications, including orlistat and phentermine/topiramate. The key trials included the STEP, SCALE and SURMOUNT trials, which were industry-funded, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials having low attrition rates (less than 10 percent), indicating that the risk of selection and performance bias was low. However, trial subjects were given structured lifestyle counseling, which can restrict extrapolation to normal clinical practice. The interpretation of trial results should put into account real-world discontinuation rates and heterogeneity of patient populations.

Competitive effectiveness

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the major randomized trials comparing the efficacy and safety of leading GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual-agonist therapy in weight loss, glycemic control, and safety. The greatest mean weight reductions were observed so far (up to -20.9% in SURMOUNT-1), with tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, being superior to semaglutide (-14.9% in STEP-1) and liraglutide (8% in SCALE). However, semaglutide is the strongest single GLP-1 receptor agonist, and has a broad range of cardiovascular outcome trial evidence. Liraglutide has a lower, yet statistically significant, level of weight loss and an established long-term safety record. Due to the differences in dosing schedules, tolerability, and comorbidity advantages of these agents, clinicians must tailor therapy choices based on patient factors, preferences, and cost/access factors.

| Drug (dose) | Trial (primary ref) | N (randomized) | Mean % change in body weight (treatment vs placebo) (95% CI) | % ≥10% / % ≥15% (treatment) | AE/discontinuation due to AEs (treatment vs placebo) | Funding |

| Semaglutide 2.4 mg wkly | STEP-1 (Wilding et al., 2021)13. | 1,961 | −14.9% (semaglutide) vs −2.4% (placebo); treatment difference −12.4 percentage points (95% CI −13.4 to −11.5; P<0.001). | ≥10%: 66% (approx., treatment) (trial reported distribution). | GI AEs most common (nausea, diarrhea); discontinuation due to AEs: semaglutide 4.5% vs placebo 0.8%. | Industry (Novo Nordisk) |

| Liraglutide 3.0 mg daily | SCALE Obesity & Prediabetes (Pi-Sunyer et al., 2015)14. | 3,731 | Mean weight change ~ −8.4 kg vs −2.8 kg (difference −5.6 kg; 95% CI −6.0 to −5.1; P<0.001). (Reported as kg in primary paper.) | ≥10%: reported in trial tables (see primary paper). | GI AEs most common; serious AEs similar to placebo (6.2% vs 5.0%); discontinuation data in main text. | Industry (Novo Nordisk) |

| Tirzepatide 15 mg wkly | SURMOUNT-1 (Jastreboff et al., NEJM 2022)15. | 2,539 | Mean % change at 72 wk: −20.9% (15 mg) vs −3.1% (placebo); 95% CI for 15 mg −21.8 to −19.9; P<0.001. | ≥20%: 50–57% at higher doses (10–15 mg). | GI events common; discontinuation due to AEs: 4.3% (5 mg), 7.1% (10 mg), 6.2% (15 mg) vs 2.6% placebo. | Industry (Eli Lilly) |

| Dalaglutide 3.0–4.5 mg wkly | AWARD-11 (Frias et al., 2021)16. | (trial population sizes per arm reported in AWARD-11) | Mean weight loss at 36 wk: dose-dependent reductions (e.g., ~−4.7 kg with 4.5 mg in AWARD-11). | Modest vs semaglutide/tirzepatide; secondary endpoint in many trials. | GI AEs typical of class; lower magnitude of weight loss than semaglutide/tirzepatide. |

Several cost-effectiveness studies project semaglutide 2.4 mg cost as producing $140,000-170,000/QALY increase at present list prices, more than conventional U.S. levels. It would need to cut down prices by 30-50% to reach the benchmarks of $100,000/QALY17. However, long-term modeling forecasts offsets of costs in the form of lower cases of diabetes, cardiovascular and obesity-related complications, which may justify inevitable net savings in the event that drug costs drop.

Advances in the incretin-based therapies

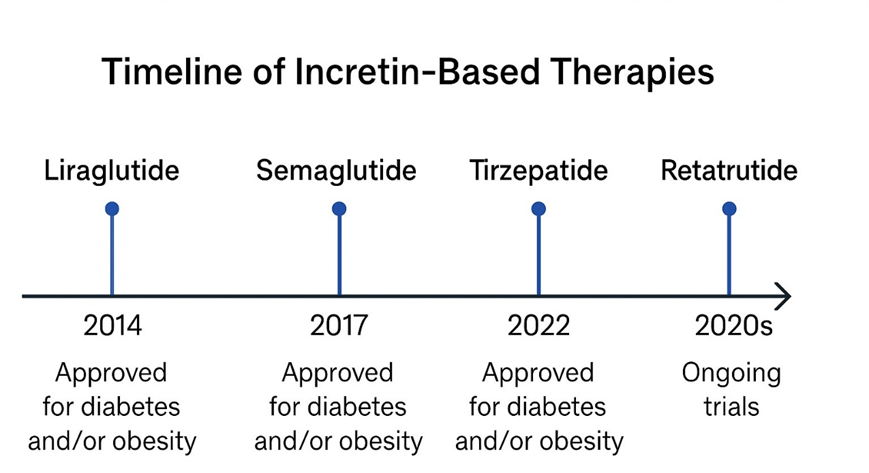

During the previous decade, the enhancement of incretin-based therapy was observed in its effectiveness and clinical use. Early advances in Liraglutide led to more effective drugs such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, the former a dual GLP-1/GIP agonist. Most recently, retatrutid, a triple agonist that works at GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors, is in phase II trials, with an up to 24.2 percent weight loss after 48 weeks. This swift development of the incretin pharmacotherapy is an important innovation cycle in obesity and diabetes treatment18. Figure 2 below depicts the timeline of the development of key GLP-1-based therapeutics with the emphasis on clinical progression of the single and dual/triple receptor agonists.

Real-world effectiveness and adherence

GLP-1 and dual-agonist therapies have been proven to be effective in a randomised trial, but the level of persistence is weaker in observational studies regarding the routine practice. According to recent research, variable persistence is shown: United States electronic health records show that roughly 30-50% of patients using GLP-1s from 6-12 months experience costs related to these medications. The presence of manufacturer savings programs was found to significantly reduce costs for some patients, with many opportunities for cost savings being overlooked by patients and providers19. In the real world, multifactorial discontinuations most commonly include (1) gastrointestinal adverse events during dose escalation (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), all these common and decreasing with age; (2) high out-of-pocket costs and prior-authorization regulations; (3) logistics (scarce supply, injection burdensome to some patients); (4) inadequate longitudinal follow-up and support to prevent weight gain20.

Drug cost and insurance coverage

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs create a financial hurdle that restricts their widespread use, especially when applied to weight management treatments. One of the most significant impediments is affordability: the list price of Wegovy (semaglutide 2.4 mg) in the U.S was almost $1,349 per 28-day supply, which restricts the real-life use of the drug in the uninsured and under-insured population. In 2024, GLP-1 receptor agonists continue as one of the premium long-term pharmacotherapies due to their United States retail prices exceeding $1,000 every month. The effectiveness of these medications remains proven, but insurance providers show reservations when approving their use for patients with obesity rather than type 2 diabetes21. The majority of commercial insurance plans, together with public payers that include Medicaid, enforce rigid reimbursement systems that provide restricted access to medications through diagnosis limitations and prior authorization protocols. Patients bear significant out-of-pocket expenses because of the high medication cost, which prevent them from starting treatment or force them to stop treatment prematurely. The current problem selectively affects people from lower economic groups and those without adequate medical insurance, while reducing both population health advantages and health equity in obesity treatments that use GLP-1 (Table 2).

| Drug (common brand) | Representative list price (28-day pack/month) — USD | Typical reported retail/cash price (range) | Estimated annual list-price cost (USD) | Typical insurer coverage/notes |

| Semaglutide (Wegovy 2.4 mg) | $1,349.02 per 28-day pack (manufacturer list). 21 | Retail cash commonly reported $1,300–2,000/mo; manufacturer patient assistance & savings card programs may reduce out-of-pocket. | ≈ $16,188/year (list price × 12). | Coverage varies; NICE negotiated discounted prices for NHS; US private payers vary, Medicaid coverage state-specific; Medicare Part D historically excluded for obesity indication. |

| Semaglutide (Ozempic for diabetes) | $997.58 / 28-day pack (manufacturer list for diabetic dosing) (representative)22 | Retail cash ~$500–1,300/mo with coupons/discounts. | ≈ $11,970/year (list price × 12). | Typically covered for diabetes indications more often than for obesity. |

| Oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) | $997.58 per 30-tablet supply — list price (manufacturer)23 | Retail/cash variable; manufacturer savings often available for eligible insured patients | ≈ $11,970/year. | Coverage often granted for diabetes indications; off-label use for weight management limited. |

| Tirzepatide (Mounjaro / Zepbound) | Mounjaro list price/pen ≈ $1,023–1,200 per month (reported ranges) | Reported retail ~$1,000/mo (varies by pharmacy and coupons). | ≈ $12,000/year (list price basis). | FDA approved for diabetes (Mounjaro) and for chronic weight management (Zepbound) — coverage for weight indication variable; expected high payer scrutiny due to budget impact24 |

Addressing affordability and expanding access

Policy solutions

The implementation of multiple policies is necessary for improving both the affordability and fair distribution of GLP-1 receptor agonists. The implementation of evidence-based anti-obesity pharmacotherapy coverage by Medicare and Medicaid would significantly enhance equitable access to care for low-income populations. The treatment of obesity as an approachable chronic disease through new legislation will help establish broader reimbursement policies. The market pricing may fall due to patent expiration and the introduction of GLP-1 biosimilars and generic analogues, but regulatory end-of-life issues may slow down this price reduction process23. The NovoCare and similar access programs from the pharmaceutical industries help some patients, but their scope falls short because they fail to assist uninsured or underinsured patients completely. Affordable long-term outcomes for GLP-1 treatments require the formation of extensive public-private alliances, together with government funding and universal price agreement practices similar to those used for essential medicines.

Although the qualities like universal coverage, biosimilar incentives, and affordability standards were quite desirable, they were heavily challenged. The broad coverage mandates including the legislature and the funding of payers’ budgets that can be subject to political opposition. The high cost of biologic production and the regulatory exclusivity delay biosimilar development. The affordability criteria should strike a balance between innovation and cost control; they need to be negotiated among manufacturers, payers, and policymakers. The objective of these is that the success is likely to come in stages, value issue-based remuneration, and global reference pricing models to enhance incremental access.

Ethical and health equity concerns

Limited availability of GLP-1 therapies generates substantial ethical problems, especially when considering systematic health inequalities. Individuals from lower-income backgrounds and minority racial groups, along with rural residents, face numerous health care system hurdles that prevent them from receiving adequate medical services. Socioeconomic factors that affect health, such as food scarcity and restricted healthcare access, and racism as a social structure, together lead these particular groups to become more susceptible to obesity prevalence24. People in these populations face almost complete exclusion from advanced medical treatments because obstacles, including cost and insurance hurdles, prevent their access. Health disparities continue because disease burden exceeds the availability of adequate treatment, leading to the necessity for equity-centered policies that focus on providing treatment access for vulnerable populations.

Global access and disparities

Availability of these treatments across the world is also quite inconsistent, pointing to an imbalance in health policy, the financing system, and the medical community. The majority of the data on the use of GLP-1 is publicly available in high-income nations. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom provided recommendations in March 2023 to use semaglutide (2.4 mg once a week) in adults with a body mass index (BM) of 35 kg/m 2 or more, or BM 30 kg/m 2 or more with comorbidities and enrolled on a specialist Tier 3 weight management program (NICE, 2022)25. Nonetheless, efforts have been sluggish due to a constrained capacity in Tier 3/4 services and delays in integrating GLP-1 therapies into the daily care routine in all NHS Trusts.

In Canada, the use of GLP-1 agonist agents, such as semaglutide and liraglutide, is covered to some extent, although coverage varies by province and insurer. Public drug plans can cover these medications in cases of type 2 diabetes, but when it comes to obesity, coverage is not as uniform and is typically subject to physician rationale and special authorization (CADTH, 2021).

In Australia, semaglutide is on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) at the Australian level as a therapy to treat type 2 diabetes, but not yet a subsidized weight loss drug, constraining its application in obesity therapy. Patients who seek semaglutide as a treatment to reduce weight are to pay the full private cost, which largely impedes the use by the population lacking a private insurance subscription26..

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have even fewer means of access, with GLP-1 drugs unavailable or unaffordable, because of the unavailability of generics, import bans, or failure to make it into the national formulary. The latest figures provided by the World Obesity Federation indicate that the burden of obesity is increasing at the fastest pace in LMICs, and modern pharmacologic therapy is still poorly available27. This treatment gap is an increasing trend and has laid stress on the development of global health initiatives across the world that may lower costs, enhance the supply chain, and make equitable distribution of GLP-1 therapies.

Limitations

The evidence presented in this review is a synthesis of randomized clinical trials and real-world studies, most of which were carried out in high-income countries, so it might not be applicable in low- and middle-income contexts. Most of the landmark trials were industry-sponsored and done in intensive follow-up conditions, and this could overestimate compliance in comparison with the actual practice. There is a relative dearth of long-term safety data longer than three years, especially in non-diabetic groups, and cost estimations are extremely sensitive to assumptions on drug prices, insurance cover, and treatment duration.

Conclusion

The emergence of GLP-1 receptor agonists transformed obesity treatment by providing revolutionary effectiveness at reducing obesity along with improving metabolic control. The clinical benefits of these medications face substantial limitations because of expensive product costs and stringent insurance limitations. The obstacles create multiple problems that restrict individual patient health results as well as generate public health consequences, which worsen existing health inequalities. The complete social advantages of GLP-1–based therapies demand the development of accessible and fair strategies for implementation. Three critical measures for implementing GLP-1-based therapeutic equity include requiring universal coverage, developing incentives for biosimilar advancements, and creating extensive affordability standards. Strategic coordination between healthcare institutions enables optimal utilization of the powerful benefits of GLP-1 agonists in eliminating the worldwide obesity crisis. In addition, clinical success should be translated into the real world only when we continue to invest in healthcare equity, international cooperation, and education. Future stages of GLP-1 incorporation would have to focus on long-term medication compliance, fair access to all groups of people, and a policy on the treatment of obesity as a chronic and recurring condition, and not a lifestyle choice. The utmost potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists in alleviating the global burden of obesity can only be achieved once scientific innovation is combined with social responsibility.

References

- World Health Organization (2024), (available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [↩]

- R. B. Kumar, L. J. Aronne, Pharmacologic Treatment of Obesity. Nih.gov (2024), (available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279038/ [↩]

- Z. Zheng, Y. Zong, Y. Ma, Y. Tian, Y. Pang, C. Zhang, J. Gao, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 9, 1–29 (2024). [↩] [↩]

- T. D. Müller, B. Finan, S. R. Bloom, D. D’Alessio, D. J. Drucker, P. R. Flatt, A. Fritsche, F. Gribble, H. J. Grill, J. F. Habener, J. J. Holst, W. Langhans, J. J. Meier, M. A. Nauck, D. Perez-Tilve, A. Pocai, F. Reimann, D. A. Sandoval, T. W. Schwartz, R. J. Seeley, Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Molecular Metabolism. 30, 72–130 (2019). [↩]

- D. Sharma, S. Verma, S. Vaidya, K. Kalia, V. Tiwari, Recent updates on GLP-1 agonists: Current advancements & challenges. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 108, 952–962 (2018). [↩]

- J. E. Campbell, T. D. Müller, B. Finan, R. D. DiMarchi, M. H. Tschöp, D. A. D’Alessio, GIPR/GLP-1R dual agonist therapies for diabetes and weight loss—chemistry, physiology, and clinical applications. Cell Metabolism. 35, 1519–1529 (2023). [↩]

- X. Zhao, M. Wang, Z. Wen, Z. Lu, L. Cui, C. Fu, H. Xue, Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Beyond Their Pancreatic Effects. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 12 (2021). [↩]

- A. Secher, J. Jelsing, A. F. Baquero, J. Hecksher-Sørensen, M. A. Cowley, L. S. Dalbøge, G. Hansen, K. L. Grove, C. Pyke, K. Raun, L. Schäffer, M. Tang-Christensen, S. Verma, B. M. Witgen, N. Vrang, L. Bjerre Knudsen, The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124, 4473–4488 (2014). [↩]

- https://www.facebook.com/Drugscom, Novo Nordisk Lowers Cost of Ozempic to $499 per Month for Self-Paying Patients MedNews. Drugs.com (2025), (available at https://www.drugs.com/clinical_trials/novo-nordisk-lowers-cost-ozempic-499-per-month-self-paying-patients 22147.html [↩]

- Popular GLP-1 Agonists List, Drug Prices and Medication Information. GoodRx, (available at https://www.goodrx.com/classes/glp-1-agonists). [↩]

- J. P. H. Wilding, R. L. Batterham, S. Calanna, Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 384, 989–1002 (2021). [↩] [↩]

- X. Pi-Sunyer, A. Astrup, K. Fujioka, F. Greenway, A. Halpern, M. Krempf, D. C. W. Lau, C. W. le Roux, R. Violante Ortiz, C. B. Jensen, J. P. H. Wilding, A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. New England Journal of Medicine. 373 11–22 (2015). [↩]

- J. P. H. Wilding, R. L. Batterham, S. Calanna. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine 384, 989–1002 (2021). [↩]

- X. Pi-Sunyer, A. Astrup, K. Fujioka, F. Greenway, A. Halpern, M. Krempf, D. C. W. Lau, C. W. le Roux, R. V. Ortiz, C. B. Jensen, J. P. H. Wilding. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. The New England Journal of Medicine 373, 11–22 (2015). [↩]

- T. A. Wadden, O. A. Walsh, R. I. Berkowitz, A. M. Chao, N. Alamuddin, K. Gruber, S. Leonard, K. Mugler, Z. Bakizada, J. S. Tronieri. Intensive behavioral therapy for obesity combined with liraglutide 3.0 mg: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity 27, 75–86 (2018). [↩]

- J. P. Frias, E. Bonora, L. N. Ruiz, Y. G. Li, Z. Yu, Z. Milicevic, R. Malik, M. A. Bethel, D. A. Cox. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide 3.0 mg and 4.5 mg versus 1.5 mg in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-11). Diabetes Care 44, 1–10 (2021). [↩]

- J. H. Hwang, N. Laiteerapong, E. S. Huang, D. D. Kim, Lifetime Health Effects and Cost-Effectiveness of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide in US Adults. JAMA Health Forum. 6, e245586 (2025). [↩]

- A. M. Chao, J. S. Tronieri, A. Amaro, T. A. Wadden, Clinical Insight on Semaglutide for Chronic Weight Management in Adults: Patient Selection and Special Considerations. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. Volume 16 4449–4461 (2022). [↩]

- R. W. Thomsen, A. Mailhac, J. B. Løhde, A. Pottegård, Real-world evidence on the utilization, clinical and comparative effectiveness, and adverse effects of newer GLP-1RA-based weight-loss therapies. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 27 Suppl 2, 66–88 (2025). [↩]

- J. J. Gorgojo-Martínez, P. Mezquita-Raya, J. Carretero-Gómez, A. Castro, A. Cebrián-Cuenca, A. de Torres-Sánchez, M. D. García-de-Lucas, J. Núñez, J. C. Obaya, M. J. Soler, J. L. Górriz, M. Á. Rubio-Herrera, Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 12, 145 (2023). [↩]

- T. A. Wadden, P. Hollander, S. Klein, K. Niswender, V. Woo, P. M. Hale, L. Aronne, Weight maintenance and additional weight loss with liraglutide after low-calorie-diet-induced weight loss: The SCALE Maintenance randomized study. International Journal of Obesity. 37, 1443–1451 (2013). [↩]

- A. M. Jastreboff, L. J. Aronne, N. N. Ahmad, S. Wharton, L. Connery, B. Alves, A. Kiyosue, S. Zhang, B. Liu, M. C. Bunck, A. Stefanski, Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 387 (2022). [↩]

- S. W. Waldrop, V. R. Johnson, F. C. Stanford, Inequalities in the provision of GLP-1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity. Nature Medicine. 30, 1–4 (2024). [↩]

- T. Karagiannis, E. Bekiari, Apostolos Tsapas, Socioeconomic aspects of incretin-based therapy. Diabetologia (2023), doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-023-05962-z. [↩]

- NICE, NICE | the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE (2022), (available at https://www.nice.org.uk/). [↩]

- NICE, NICE | the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE (2022), (available at https://www.nice.org.uk/). [↩]

- “Obesity: missing the 2025 global targets Trends, Costs and Country Reports” (2020), (available at https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/WOF-Missing-the-2025-Global-Targets-Report-FINAL-WEB.pdf). [↩]