Abstract

With Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) technology becoming an integral part of many aspects of daily life, ensuring equitable access for all speakers, regardless of accent, dialect, or linguistic background, is crucial. These systems are heavily relied upon in fields such as healthcare, education, and customer support, where accurate communication is vital. This study investigates the accessibility of widely used ASR systems across a diverse range of accents. Through a detailed evaluation of three prominent open-source ASR models, Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk, using traditional metrics such as Word Error Rate, Character Error Rate, and Keyword Error Rate, this study identifies limitations in current ASR systems and emphasizes the need for more inclusive technology. The analysis was conducted on 3,038 audio recordings from the Speech Accent Archive, encompassing 293 linguistic groups, each reading a standardized passage designed to elicit diverse English phonemes. The number of speakers from each linguistic group varied from one to several hundred. All samples were used for model evaluation only, with no train, validation, or test splits, as the goal was to benchmark existing ASR performance rather than train or fine-tune new models. The findings reveal that while improvements have been made in performance due to multilingual datasets, substantial disparities remain: Whisper large-v3 achieved a mean WER of 9.3%, compared to 26.1% for Wav2Vec2 classic and 32.9% for Vosk en-0.22, representing more than a threefold difference in accuracy across models. Even within the best-performing model, underrepresented linguistic groups such as Sylheti and Haitian Creole showed WER, CER, and KER values 15–20 percentage points higher than well-represented groups like English and French, indicating that substantial gaps remain for marginalized linguistic groups. This research also calls for the development of ASR models built on data from a more diverse range of linguistic backgrounds, as well as architectures designed to better handle phonetic variability.

Keywords: ASR, Accented Language, Speech Recognition, Inclusive Technology

Introduction

Background and Context

In today’s rapidly evolving technological world, automatic speech recognition (ASR) technology has become an integral part of many daily activities, from dictating text messages to serving as a virtual assistant, greatly simplifying many tasks1 . These tools have been revolutionary, allowing individuals to interact with devices and services much faster and more efficiently2. However, as speech-based interfaces and services become more widespread, a critical issue must be addressed: ensuring that ASR systems serve all users equitably3.

A growing body of research has highlighted a significant disparity in ASR systems’ ability to accurately transcribe content from diverse accents, dialects, and linguistic groups. These noted disparities are not simply technical limitations; they reflect deeper issues of bias within training data. Certain linguistic groups, particularly those from marginalized communities, are often underrepresented in the training data for ASR models, leading to a systematic disadvantage4. Prior research underscores this issue, showing that African American Language speakers, for example, experience significantly poorer performance from ASR systems, which can exacerbate existing disparities in areas like healthcare and education5. In healthcare, biased ASRs can misrepresent patient speech in ways that obscure chronic conditions and risk misdiagnosis or incorrect treatment5. In education, ASR errors reinforce stigmas against African American Language, shaping teacher perceptions and contributing to student underachievement and disproportionate placement in special education6.

Research Motivation

While there have been some improvements in inclusivity through training on multilingual data, accessibility gaps persist, highlighting the main problem motivating this work7‘8. Accessibility, in this context, refers to the ability of ASR systems to minimize error rates in Word Error Rate (WER), Character Error Rate (CER), and Keyword Error Rate (KER), ensuring accurate transcription for all speakers, regardless of linguistic backgrounds.

This project explores the following questions: how can the accessibility of existing open-source ASR systems across diverse linguistic backgrounds be effectively measured, and what improvements can be made in the future to enhance inclusivity, particularly for speakers with global majority accents and dialects? Here, ‘Global majority’ refers to languages, dialects, and accents spoken by the majority of the world’s population, often outside of the Western-centric linguistic norms that are prevalent in ASR model development. By comparing the performance of three open-source transcription models on a controlled, accent-diverse dataset using multiple scoring methods, this research assesses the extent of inequality in existing ASR tools and suggests improvements for enhancing accessibility, aiming for better performance across diverse linguistic groups in the future.

Literature Review

Disparities in ASR Performance Across Linguistic Variations

Previous research has found that transcription accuracy can vary significantly depending on the speaker’s linguistic background9. Commercial ASR systems, in particular, including those by Amazon, Apple, Google, IBM, and Microsoft, exhibit a wide disparity in error rates based on race3. Specifically, these systems had a WER of 35% for Black speakers compared to 19% for White speakers, even after controlling for sentence complexity and speaker fluency3. Further research found that while Bing Speech showed no significant variation across gender or race, YouTube’s automatic captioning system demonstrated a significant WER difference across races and dialects9. This difference highlights the potential for ASR systems to reinforce communication barriers for underrepresented and marginalized groups, and the need for ASR systems to be improved to better accommodate diverse linguistic groups.

Existing Metrics for Evaluating ASR Accessibility

Traditional evaluation of ASR systems has relied heavily on WER, which measures the accuracy of word-level transcriptions10. While widely used, WER has notable limitations, particularly for multilingual speech, because it can remain deceptively low even when an ASR system fails to preserve meaning, limiting its effectiveness in real-world applications11‘12.

In response to these shortcomings, researchers have proposed alternative metrics such as character error rate and keyword error rate13. CER, which evaluates transcriptions at the character level, is often less sensitive to structural differences across languages, like a lack of word boundaries, making it more reliable for evaluating multilingual datasets13 KER, meanwhile, rewards the preservation of essential keywords, providing additional sensitivity in low-accuracy scenarios where overall WER may mask transcription failures14.

Taken together, these critiques highlight a broader concern: current evaluation practices remain overly reliant on WER, which is inadequate for measuring content preservation. To address this, recent studies have developed meaning-focused approaches that assess whether ASR systems convey the underlying concepts of speech rather than just word-for-word or character-for-character accuracy15. Early studies have shown that this new approach may be a stronger evaluation metric in certain real-world contexts16.

Multilingual and Cross-Dialectal Approaches to ASR

As the limitations of traditional monolingual models have begun to be identified, the move towards ASR models trained on multilingual text has gained traction17. Recently, researchers trained a model on 51 languages and reduced WER by up to 28.8% for languages with limited data17. This approach holds significant promise for improving ASR performance across a diverse set of languages.

A group of researchers recently developed XLSR, a model that learns from unlabeled speech18. When XLSR was trained further with labeled data, it reduced phoneme errors by 72% on CommonVoice and improved word accuracy by 16% on BABEL19. These findings suggest that designing ASR systems to focus on multiple languages can not only improve overall performance for underrepresented linguistic groups but also help reduce bias stemming from an imbalanced training set. These findings highlight the potential for the usage of multilingual datasets to create equally accessible ASR technology.

Limitations of Current Open-Source ASR Models

Several open-source ASR models have been trained on large datasets, including Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk, but their performance has still been found to be uneven and inconsistent20. Specifically, these models have been shown to excel at recognizing and transcribing speech from standardized accents, such as American English, but struggle with accents and non-native English21. For instance, Whisper, despite being trained on a multilingual dataset, still exhibits high error rates when transcribing speakers from rural or minority communities22. While large-scale, multilingual training data have been shown to improve overall recognition, there is still often a lack of accent variations that are crucial for comprehensive ASR performance23. In addition to accent-related issues, biases in training data remain a significant concern. Many open-source models do not adequately capture the diversity of accents or dialects, leading to persistent gaps in ASR performance for underrepresented linguistic groups24.

Beyond data limitations, current ASR architectures may also contribute to uneven performance for diverse linguistic groups. Many models rely on uniform feature extraction pipelines and shared embeddings, architectural choices that often optimize for generalized speech patterns, thus potentially making it more difficult to capture subtle differences across accents or dialects25‘26‘27. As a result, even when training data includes some accent diversity, it is possible that the models do not fully leverage it, which could contribute to gaps in accuracy for certain speakers.

These potential limitations in both datasets and model architectures can undermine transcription accuracy and impact the trust users have in these systems, particularly among speakers from historically marginalized communities28. For example, failures in ASR technology can result in feelings of self-consciousness and lower self-esteem among affected users, which continues the cycle of bias within datasets and limits the overall inclusivity and accessibility of these technologies28. Additionally, poor ASR performance can manifest in downstream harms, as users of color and non-native English speakers may experience unique challenges29. These harms, including frustrations and misunderstandings, further contribute to users’ negative perceptions of the technology29. This can have a lasting effect on their relationship with voice assistants, reinforcing barriers to equitable service and continuing the cycle of exclusion29.

Methodology

This study employed a systematic approach to evaluate the accessibility of open-source ASR systems across diverse linguistic backgrounds. The methodology focused on assessing the performance of three widely used ASR models: Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk, across a standardized dataset of various accents and dialects. By applying established error metrics (WER, CER, and KER), the accessibility of each model was measured across a wide range of speakers. The goal was to identify patterns of inaccessibility, such as higher error rates for global majority accents and dialects.

Datasets

The data for this study was sourced from the Speech Accent Archive, which is a widely utilized dataset that includes over 3,000 short recordings from speakers representing 293 linguistic groups across more than 100 global regions30. Each speaker reads an identical, carefully designed passage that incorporates almost every phonetic element of the English language. Because all speakers read identical text, ASR errors can be directly compared across linguistic groups.

All 3,038 audio recordings were included in this analysis in order to provide comprehensive coverage of the linguistic diversity represented in the corpus. Speaker representation per linguistic group ranged from one to several hundred, largely reflecting the differing global prevalence of each linguistic group.

The Speech Accent Archive had been employed in similar research in the past to evaluate ASR performance across accents and dialects31. This dataset spans a wide array of accents, dialects, and non-native English speakers. This includes speakers from regions with well-represented accents, such as Standard American English, as well as speakers that are typically less-represented, such as Bambara, Kongo, and Marathi. The inclusion of these diverse groups allows for a more complete understanding of how ASR models handle linguistic variation, particularly for underrepresented linguistic groups.

Dataset Preparation

Before analysis could be completed for each language and model, each audio file was converted into the standardized, 16kHz sampling rate .wav format required by the open-source ASR models evaluated in this study. The usage of a uniform file format ensured compatibility with the models.

In addition to file format standardization, volume levels were normalized across all audio files. This step ensured consistent transcription performance by adjusting all recordings to a similar volume and loudness level. By controlling for volume variation, potential biases that could have arisen from discrepancies in the audio are eliminated, resulting in a fairer evaluation of each ASR model’s accuracy across linguistic groups. An analysis was performed without the audio normalization, revealing very minimal improvements in some cases and slight decreases in others in transcription accuracy across models. This suggests that the models are largely robust to volume variation, and therefore, while normalization helped ensure consistency, it was not a major contributing factor to overall performance.

Finally, data that was not suitable for ASR evaluation, such as recordings from linguistic groups like American Sign Language (ASL), were removed from the dataset. Their exclusion ensures that the analysis focuses only on data appropriate for transcription evaluation.

Data Manipulation and Evaluation

All audio samples were passed through three open-source ASR models on both the smallest and largest versions of the model. For each model and for each version, the generated transcript, or the hypothesis, was stored in a text file and compared to the reference paragraph using the previously discussed WER, CER, and KER metrics.

For implementation, all data processing and analysis were performed in a simple Python environment within Visual Studio. Since larger models, like Whisper large-v3, required more computational resources, they were run on Google Colab and Kaggle, utilizing their free GPU resources.

After collecting the transcriptions, the evaluation scores (WER, CER, KER) were compiled into structured datasets for further analysis. Descriptive statistics, including the mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and interquartile range, were calculated for each metric to summarize performance across linguistic groups.

To assess whether the observed differences between evaluation metrics were statistically significant, a one-way ANOVA test was conducted. This tested the null hypothesis that the mean error scores for WER, CER, and KER were equal. When the ANOVA returned a significant result (p < 0.05), we followed with Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test to identify which specific metrics differed significantly from each other. All statistical testing was conducted using the Python libraries scipy.stats and statsmodels, with a significance level of α = 0.05.

In addition to the statistical testing, visualizations were generated to highlight transcription performance trends. These included graphs showing per-accent accuracy and keyword-level error rates. The graphs were used to identify which accents were most and least accurately transcribed by each model, which linguistic groups were the lowest performing across all metrics, and which words were being mistranscribed at the highest rate. This visual analysis helped to identify patterns of inaccessibility for certain linguistic groups and highlighted accents and dialects that may be underrepresented.

In addition to the main error metrics, this study conducted a detailed phoneme-level and error-type analysis to investigate the sources of transcription errors. For each model, substitution, insertion, and deletion (S/I/D) counts were extracted from the model outputs relative to the reference transcriptions. These counts were then averaged per audio file and across linguistic groups to quantify the distribution of error types. Phoneme-level confusion analysis was performed across linguistic groups by aligning reference and hypothesis transcriptions at the phoneme level, enabling identification of the sounds most frequently misrecognized or substituted.

Computing Environment

All experiments were conducted on macOS 14.7.7 (Build 23H723) with Python 3.8.18. Major libraries included torch 2.2.2, torchaudio 2.2.2, transformers 4.46.3, vosk 0.3.44, openai-whisper (commit c0d2f62), numpy 1.24.4, pandas 2.0.3, matplotlib 3.7.5, scipy 1.10.1, jiwer 4.0.0, and g2p 2.1.0. All three models were run on a GPU (NVIDIA Tesla P100 on Kaggle) when available, otherwise on a CPU. Random seeds were not explicitly set; however, all models were evaluated in eval() mode with torch.no_grad(), ensuring deterministic outputs for a given input audio file, although minor variations may still occur.

Transcription Tools and Model Selection

OpenAI’s Whisper was selected as the first ASR model for this study due to its strong performance in transcribing multilingual inputs32. Whisper is an open-source model trained on a diverse multilingual dataset, making it well-suited for evaluating audio inputs from diverse linguistic backgrounds. Whisper’s ability to discern a wide range of accents and dialects provides a valuable benchmark for understanding how well ASR systems can perform across linguistic variations when trained on multilingual data. Previous studies have shown that Whisper outperforms many other open-source models in multilingual transcription, making it a logical choice for evaluating the accessibility of ASR systems across accents and dialects32.

Wav2Vec2, developed by Meta, is a fairly well-known speech recognition model. It has proven effective in scenarios where labeled data is scarce, and it is competitive across various benchmarks33. Although Wav2Vec2 is not as advanced or widely adopted as Whisper, it is still a strong model for evaluating ASR accessibility, and it served as a valuable comparison for understanding the limitations of models trained on constrained datasets.

Vosk is a lesser-known, yet still effective, ASR system that was selected for this research. Vosk’s lightweight nature made it useful in resource-constrained settings34. While it lacks the large datasets and backing of models like Whisper or Wav2Vec2, Vosk’s ability to perform in diverse conditions made it a valuable tool for evaluating ASR systems.

For each model family, two variants were selected to examine the effect of model size on accuracy: a baseline (smaller) and an advanced (larger) model. Whisper base and Whisper large-v3 were included to measure improvements from scaling model parameters and slight architectural changes, such as increased Mel frequency bins for spectrogram inputs. Wav2Vec2 base and Wav2Vec2 large-960h, as well as Vosk small-en-0.15 and small-en-0.22, were selected similarly. This pairing allowed us to test whether performance improvements could be attributed to model size, while also keeping the experiments practical within available resources. Additional variants (such as Whisper medium or fine-tuned Wav2Vec2 models) were not included due to resource constraints, but they remain a promising direction for future work.

Model Versions and Decoding Settings

The details for each model are summarized in Table 1 below:

| Model Checkpoint | Library / Commit | Checkpoint | Decoding Settings |

| Whisper base | openai-whisper commit c0d2f62 | base | Beam search (beam=5, default), language=en, forced language token=en, default temperature Whisper large-v3 |

| Whisper large-v3 | openai-whisper commit c0d2f62 | large-v3 | Beam search (beam=5, default), language=en, forced language token=en, default temperature Whisper large-v3 |

| Wav2Vec2 base | transformers 4.46.3 | facebook/wav2vec2-b ase-960h | Greedy decoding, language=en, evaluated in eval() mode with torch.no_grad() |

| Wav2Vec2 classic | transformers 4.46.3 | facebook/wav2vec2-l arge-960h | Greedy decoding, language=en, evaluated in eval() mode with torch.no_grad() |

| Vosk small-en-0.15 | vosk 0.3.44 | vosk-model-small-en us-0.15 | Viterbi decoding (default), language=en, word timestamps enabled |

| Vosk small-en-0.22 | vosk 0.3.44 | vosk-model-small-en us-0.22 | Viterbi decoding (default), language=en, word timestamps enabled |

Modeling of Accessibility

In this study, several established metrics, including WER, CER, and KER, were used to evaluate the performance of the ASR models in terms of their accessibility. These metrics were selected because of their widespread use in assessing ASR systems13‘14. Additionally, valuable insight into

ASR performance can be gained via these metrics. By focusing on word, character, and keyword accuracy, these metrics help identify areas where the ASR systems could be improved to better handle accented speech, multilingual inputs, and other challenges inherent in diverse linguistic contexts.

For KER, the keyword set was drawn directly from the standardized passage in the Speech Accent Archive. Selected words and short phrases were chosen to capture a range of phonetic challenges and to emphasize nouns such as names, objects, and places (e.g., Stella, snow peas, train station). Nouns were prioritized because they carry significant semantic weight and mirror real-world contexts where accurate recognition of people, places, and objects is critical. This ensured that the KER evaluation focused on content words that matter most in practical use cases.

In evaluating KER, multiword expressions were treated as single keywords, meaning that the ASR transcription had to capture the entire phrase correctly for it to count as accurate. This was because evaluating these phrases as individual words would allow ASR models to get credit for partially recognizing the spoken phrase, which could misrepresent the system’s true performance. In contrast, WER treats each word in a multiword expression individually by design, and CER treats the passage as a sequence of characters, effectively splitting multiword expressions into the characters that make it up. By pinpointing where errors occur, these metrics guide improvements that can make ASR systems more inclusive. Addressing these issues ensures that speakers from diverse linguistic backgrounds can use ASR systems more effectively.

Results

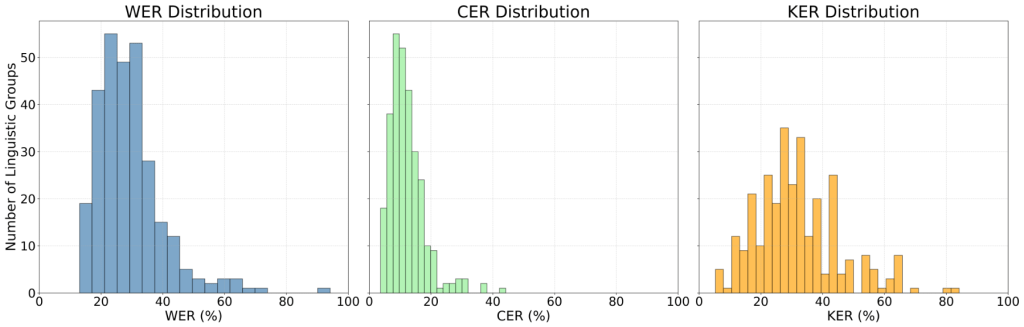

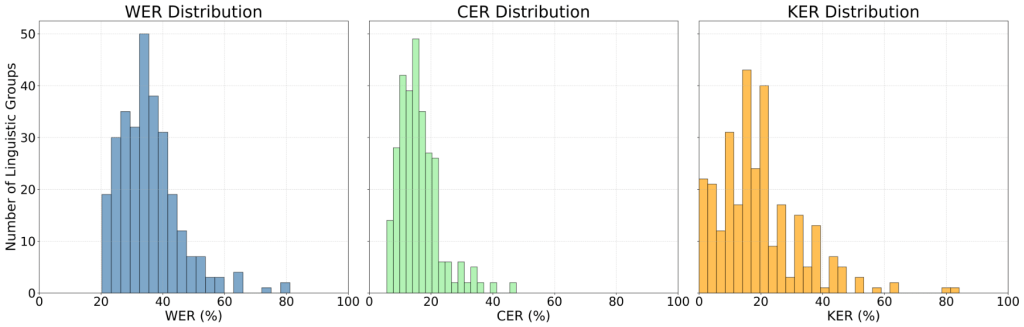

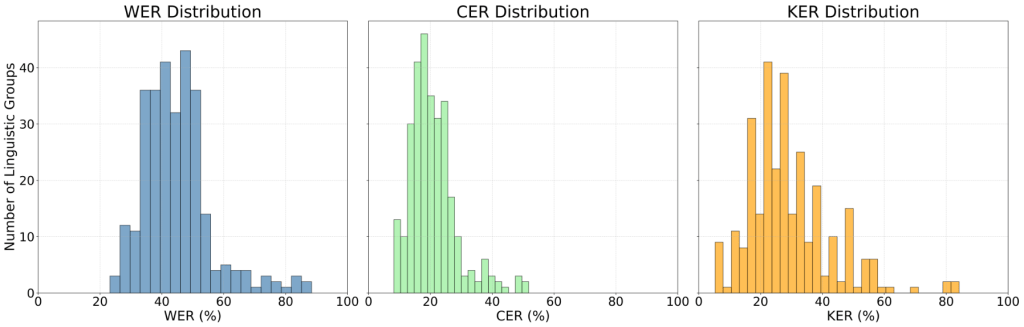

The following analysis presents the results of evaluating the accessibility of Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk on speakers from a wide range of linguistic backgrounds. The statistical measures taken to evaluate the models’ overall accessibility include mean, median, and standard deviation. Additionally, the following figures in this section are bar graphs that visualize model performance either by metric or by linguistic group. In each histogram, the X-axis represents either a specific linguistic group, model/metric, or word, and the Y-axis shows the corresponding error rate (as a percentage). Figures displaying WER, CER, and KER side by side are intended to show how each model performs across these different metrics. Figures showing the lowest-performing linguistic groups highlight which accents or dialects had the highest average error rates across all three metrics. Finally, figures that highlight the most commonly missed keywords provide insight into recurring transcription challenges faced by all three models. These figures do not reflect trends over time, but instead are grouped together for comparison purposes to reveal disparities in ASR accessibility.

Whisper Evaluation

For this research, two versions of OpenAI Whisper were selected: base and large-v3. The base model is typically oriented towards more limited resource environments and prioritizes speed over accuracy, whereas large-v3 offers higher accuracy at the expense of speed. In addition to the increase in model size, Whisper large-v3 incorporates slight architectural refinements that likely contribute to its performance gains. Specifically, it uses 128 Mel frequency bins for spectrogram inputs instead of 80 in the base model35. This adjustment allows the model to capture finer-grained acoustic features, which likely contribute to its improved transcription accuracy.

The performance of the models was measured in terms of WER, CER, and KER. These metrics were selected to assess the accessibility and reliability of OpenAI Whisper when working with a variety of linguistic groups.

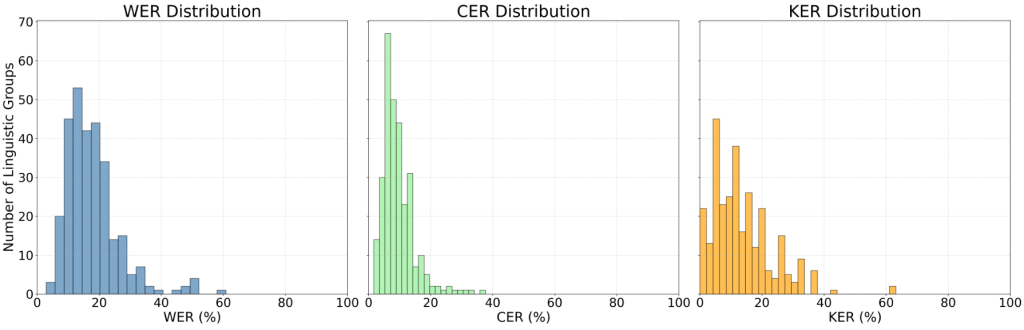

As shown in Figure 1, the large-v3 model greatly outperforms the base model across all three metrics. The graphs of WER, CER, and KER indicate that large-v3 consistently provides lower error rates, particularly in KER, as depicted in Figure 2. The overall results, summarized in Table 1, are discussed in more detail in the sections below.

| Model | Metric | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| base | WER | 15.3% | 13.0% | 10.4% |

| CER | 8.1% | 6.5% | 6.4% | |

| KER | 6.7% | 8.3% | 8.2% | |

| Large-v3 | WER | 9.3% | 7.3% | 9.2% |

| CER | 5.0% | 3.7% | 6.6% | |

| KER | 3.2% | 0.0% | 6.3% |

While Table 2 illustrates model performance across metrics, a more detailed summary of linguistic group level metrics, including worst-case performance, 90th percentile, within-linguistic group variability, and parity gaps, is provided below in Table 3.

| Model | Worst Performance | 90th Percentile | IQR Min | IQR Max | IQR Median | Absolute Parity Gap | Relative Parity Gap |

| base | 48.82% | 23.02% | 0.0% | 28.3% | 1.9% | 47.29% | 31.84% |

| Large-v3 | 41.04% | 11.08% | 0.0% | 41.0% | 0.8% | 40.09% | 42.90% |

For Whisper base, the combined metric (average of WER, CER, and KER) exhibits considerable variation across linguistic groups. The worst-performing linguistic group reached 48.82%, reflecting challenges that may arise from limited audio samples, unique phonetic patterns, or lower audio quality in those recordings. Most linguistic groups performed better, as indicated by the 90th percentile of 23.03%. Within-linguistic group variability (IQR) ranged from 0.0% to 28.3%, with a median of 1.9%, highlighting that while some groups experience highly consistent transcription, others face substantial inconsistency. The absolute parity gap of 47.29% and relative gap of 31.84%) underscore notable disparities between the highest and lowest-performing linguistic groups.

Whisper large-v3 demonstrates clear improvements in both center and spread. The worst-performing group had a combined metric of 41.04%, and the 90th percentile decreased to 11.08%. Within-linguistic group IQR ranged from 0.0% to 41.0%, with a reduced median of 0.8%. Absolute and relative parity gaps also improved to 40.09% and 42.90%, respectively. These results indicate that large-v3 reduces median errors and variability for most groups, though certain underrepresented or phonetically distinct accents continue to challenge the model. The improvements suggest that increasing model capacity enhances ASR accessibility for a wider range of speakers, but disparities remain for some linguistic groups.

WER

The base model showed a mean WER of 15.3% and a median of 13.0%, with considerable variability (standard deviation of 10.41%) across linguistic groups. Some of the highest error rates were associated with linguistic groups having fewer audio samples or unique phonetic structures, suggesting that limited representation may contribute to transcription challenges. In comparison, large-v3 showed a mean WER of 9.3% and a median of 7.3%, representing a significant improvement. Variability remained (standard deviation of 9.2%), but transcription consistency improved for most groups, indicating that more powerful models may be better able to generalize across accents.

CER

At the character level, the base model had a mean CER of 8.1% and a median of 6.5%, reflecting moderate character-level errors. Large-v3 reduced these errors substantially (mean 5.0%, median 3.7%), with lower variability (standard deviation of 6.6%). These improvements indicate that larger models may be better able to capture subword patterns, although groups with underrepresented or phonetically unusual accents still experience higher CER, potentially affecting real-world applications.

KER

The KER results highlight the most pronounced improvement with large-v3. The base model had a mean KER of 6.7% and a median of 8.3%, while large-v3 reduced this to a mean of 3.2% and a median of 0.0%. The large-v3 model demonstrates more accurate transcription of critical keywords, which is especially relevant for real-world ASR applications such as voice commands and accessibility tools. Despite this, certain underrepresented linguistic groups still exhibit high keyword errors.

Linguistic Group Analysis

An analysis of the lowest-performing linguistic groups in terms of average WER, CER, and KER scores was conducted to identify areas where Whisper’s performance could be optimized.

The linguistic groups that performed the lowest on the base model across all metrics included Newari, Sylheti, and Shan, as shown in Figure 3. Their position at the bottom suggests that these groups present particular difficulties for the base model, either due to distinctive linguistic features or limited representation in training data.

For large-v3, the top three lowest performing linguistic groups were Haitian Creole (French), Sylheti, and Quechua, as shown in Figure 4. Sylheti appears among both Whisper models, underscoring its persistent difficulty even for larger, multilingual models. However, Haitian Creole and Quechua are distinct linguistic groups not identified in the lowest-performing linguistic group analysis for the base model, suggesting that scaling the size of a model does not uniformly improve performance, and that transcription challenges may change to another linguistic group.

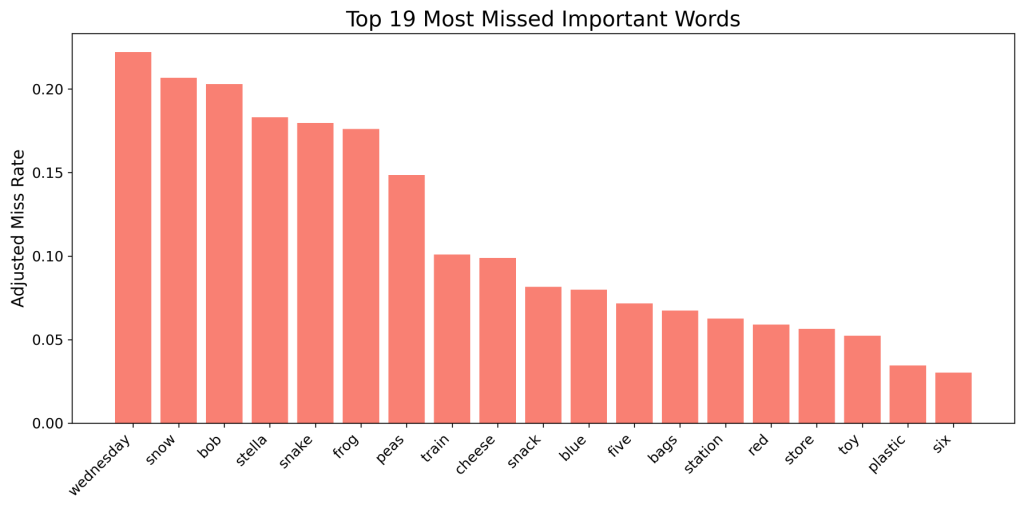

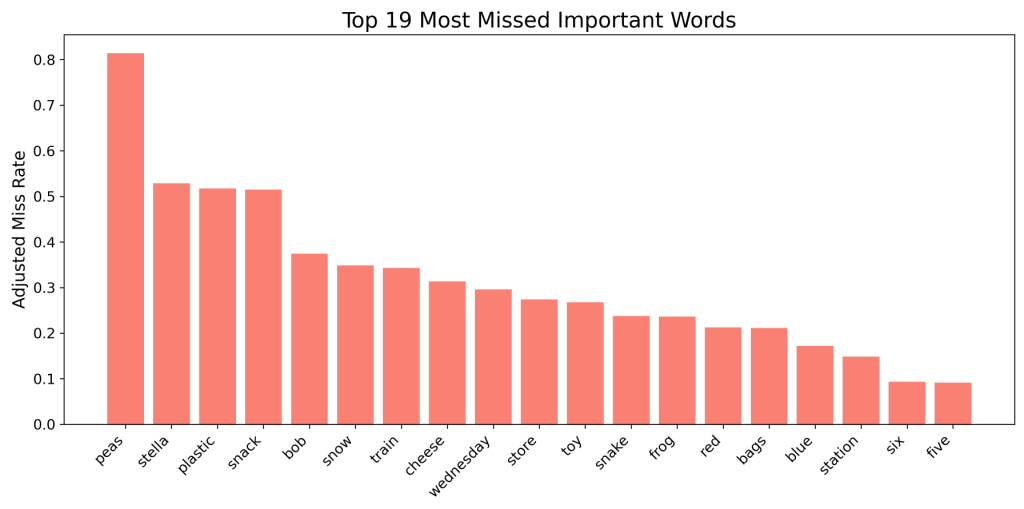

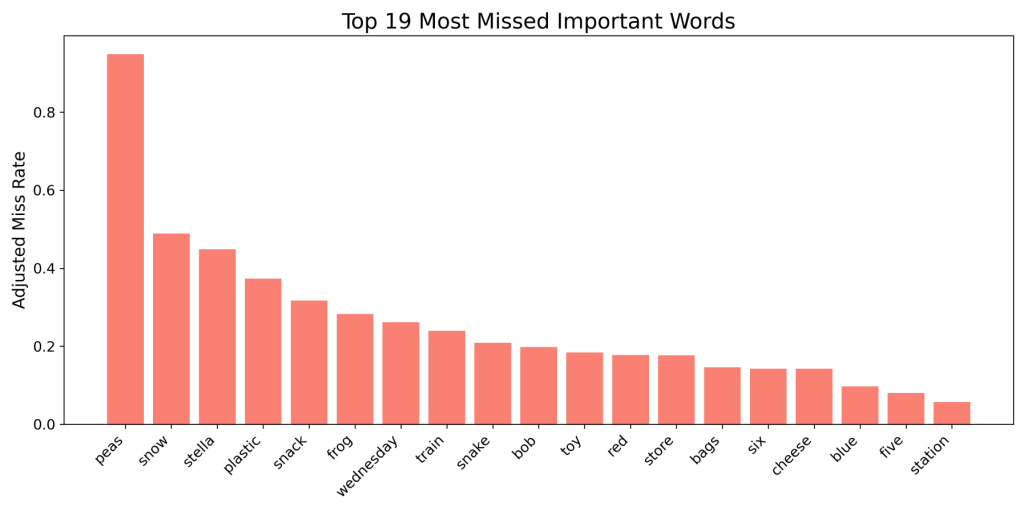

Most Frequently Missed Keywords

While Figures 3 and 4 are useful in highlighting the lowest-performing linguistic groups, additional insight can be gained by examining the specific words that both Whisper models frequently failed to recognize. Figure 5 presents the six most commonly missed keywords for Whisper base, while Figure 6 demonstrates the six most missed keywords for Whisper large-v3.

The comparison between the two models highlights a clear reduction in keyword errors when transitioning from the base model to large-v3. For example, the word “Wednesday” was transcribed incorrectly almost 800 times in Whisper base, whereas in large-v3 it was fewer than 200 times, meaning transcription errors were reduced by nearly a factor of four. This overall trend holds across all keywords, showing that scaling the model improves recognition accuracy. Additionally, although the total number of errors and positions differed between models, both Whisper base and large-v3 ranked the words “Stella” and “snake” within the top five most frequently missed keywords.

Additionally, examining the types of errors for each keyword offers deeper insight into model limitations. For instance, the word “Stella” was often transcribed as “stellar.” The word “snake” was also prone to errors, commonly appearing as “snack.” These examples highlight recurring patterns in misrecognition, emphasizing the challenges models face with accent and dialect variations. Such misinterpretations can have significant real-world consequences if not addressed correctly. For example, if a voice assistant mistakes a person’s name or an important date, it may fail to complete the intended task, undermining both trust and usability in ASR systems.

Wav2Vec2 Evaluation

For comparison, the classic and base Wav2Vec2 models were assessed across WER, CER, and KER metrics. Both models of Wav2Vec2 produced significantly higher WER and KER compared to Whisper large-v3, though they exhibited strong performance for certain linguistic groups. As illustrated in Figures 7 and 8, Wav2Vec2’s error rates are consistently higher than those of Whisper large-v3, but it still achieves relatively lower error rates for certain linguistic groups. These results are presented in Table 2 and are examined in greater detail in the following sections.

| Model | Metric | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| Base | WER | 30.6% | 27.5% | 14.5% |

| CER | 12.4% | 10.2% | 7.7% | |

| KER | 31.5% | 31.6% | 19.9% | |

| Classic | WER | 26.1% | 23.2% | 12.7% |

| CER | 10.6% | 8.8% | 6.8% | |

| KER | 26.2% | 21.1% | 17.0% |

| Model | Worst Performance | 90th Percentile | IQR Min | IQR Max | IQR Median | Absolute Parity Gap | Relative Parity Gap |

| Base | 69.91% | 44.37% | 0.0% | 25.4% | 3.7% | 62.51% | 9.44% |

| Classic | 68.94% | 35.70% | 0.0% | 24.6% | 3.2% | 61.51% | 9.29% |

For Wav2Vec2 Base, transcription performance exhibits substantial variability across linguistic groups. The worst-performing group reached 69.91%, while the 90th percentile was 44.37%, reflecting pronounced disparities in error rates. Within-group variability spans from 0.0% to 25.4% with a median of 3.7%, indicating that some linguistic groups are particularly sensitive to linguistic complexity. The absolute parity gap is 62.51%, and the relative gap is 9.44%, highlighting the considerable differences between the highest- and lowest-performing groups and underscoring potential accessibility concerns for certain accents.

The Classic model of Wav2Vec2 shows incremental improvements over Base. Its worst-performing group decreased slightly to 68.94%, and the 90th percentile dropped to 35.70%. Within-group variability remained similar (median IQR of 3.2%), while absolute and relative parity gaps were marginally lower at 61.51% and 9.29%, respectively. These patterns suggest that while Classic provides modest gains, errors for some groups persist.

WER

For Wav2Vec2 Base, the mean WER across linguistic groups was 30.6%, with a median of 27.5% and substantial variability (standard deviation 14.5%). Some of the highest error rates were observed in groups with fewer audio samples or less commonly represented phonetic patterns, suggesting that limited representation likely contributes to transcription challenges. The Classic model improved overall performance, lowering the mean WER to 26.1% and the median to 23.2%, with reduced variability (SD 12.7%). These improvements indicate that Classic helps increase transcription consistency across accents.

CER

At the character level, Base had a mean CER of 12.4% and a median of 10.2%, with a standard deviation of 7.7%, indicating that character-level errors were widespread across linguistic groups. Classic reduced the mean CER to 10.6% and the median to 8.8%, with lower variability (SD 6.8%). These improvements suggest that the Classic model captures subword patterns more reliably, improving character-level transcription across most accents.

KER

Base showed a mean KER of 31.5% and a median of 31.6%, with substantial variability (SD 19.9%), suggesting that many groups struggled with accurately transcribing critical keywords. Classic improved these metrics, achieving a mean KER of 26.2% and a median of 21.1%, with slightly lower variability (SD 17.0%). This indicates that Classic is better able to recognize and preserve essential content words.

Linguistic Group Analysis

Similar to Whisper, the lowest-performing linguistic groups were identified by averaging WER, CER, and KER.

As shown in Figure 9, the three lowest-performing linguistic groups for Wav2Vec2 base were Bai, Sylheti, and Newari. The fact that both Sylheti and Newari reappear here, as they did in Whisper’s weakest groups, suggests that these groups pose challenges across different ASR models. This consistency indicates that the issue is not model-specific but may reflect gaps in training data or distinctive linguistic features that are systematically difficult for ASR systems to capture.

Figure 10 presents the same analysis for Wav2Vec2 classic, where the lowest-performing groups were Sylheti, Chittagonian, and Newari. Again, Sylheti and Newari stand out as a recurring source of difficulty, and the consistent low-performance across both Wav2Vec2 models highlights persistent errors for linguistic groups with limited digital presence and potential underrepresentation within corpora.

Most Frequently Missed Keywords

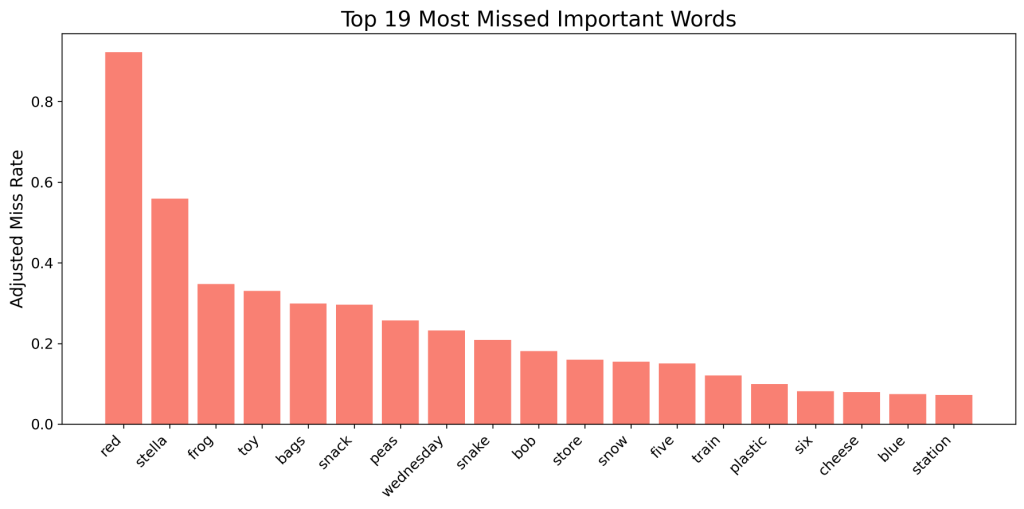

Similar to both Whisper models, Figure 11 presents the six most commonly missed keywords for Wav2Vec2 base, while Figure 12 demonstrates the six most missed keywords for Wav2Vec2 classic.

When comparing the two Wav2Vec2 models, there is a noticeable reduction in keyword errors, though it is less pronounced than the improvements observed with the Whisper models. For instance, the word “Stella” was mistranscribed over 50% of the time in Wav2Vec2 base, but this dropped to just under 45% in Wav2Vec2 classic. Not all words experienced improvement, however. The most frequently missed word in both models, “peas,” appeared incorrectly almost 80% of the time in Wav2Vec2 base, and that actually grew to just under 90% in Wav2Vec2 classic.

While many of the same words (“Stella” and “Snack”) continued to account for many of the errors, Wav2Vec2 also revealed additional challenges that were less prominent in Whisper. Notably, the word “plastic” appeared among the top four missed keywords for certain accents in both Wav2Vec2 models. Error analysis showed that “plastic” was often mistranscribed as nonsense words that sound similar, such as “plestix,” or “plassic.”

Vosk Evaluation

For this research, both the Vosk small-en-0.15 and Vosk en-0.22 models were selected to evaluate overall performance when evaluated using WER, CER, and KER. Vosk is designed to provide a balance between accuracy and efficiency, making it suitable for environments where both speed and performance are crucial.

Figure 13 illustrates that Vosk en-0.22 performs at a similar level to Whisper base on the KER metric, though it lags behind substantially on WER and CER. Figure 10 shows that Vosk small-en-0.15 performed worse across all metrics, but its performance is still relatively close to that of Vosk en-0.22. Additionally, Figures 7, 8, and 13 demonstrate that Vosk en-0.22 performs around the level of both Wav2Vec2 models for WER and CER, but still has a significantly lower KER. Table 3 provides a summary of these findings, which are discussed more thoroughly in the coming sections.

| Model | Metric | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| en-0.22 | WER | 32.9% | 29.0% | 11.7% |

| CER | 14.2% | 11.9% | 8.0% | |

| KER | 9.0% | 8.3% | 10.1% | |

| small-en-0.15 | WER | 41.8% | 39.1% | 13.5% |

| CER | 18.6% | 16.7% | 9.1% | |

| KER | 24.4% | 21.1% | 15.9% |

| Model | Worst Performance | 90th Percentile | IQR Min | IQR Max | IQR Median | Absolute Parity Gap | Relative Parity Gap |

| small-en 0.15 | 73.37% | 43.30% | 0.0% | 37.4% | 4.0% | 60.66% | 5.77% |

| en-0.22 | 70.89% | 34.68% | 0.0% | 34.6% | 2.9% | 62.24% | 8.19% |

For Vosk small-en-0.15, performance across linguistic groups is highly uneven. The worst-performing group reached 73.37%, while the 90th percentile stood at 43.30%, indicating a significant number of high-error linguistic groups. Within-group variability ranged from 0.0% to 37.4%, with a median of 4.0%. The absolute parity gap of 60.66% and relative gap of 5.77% underscore that certain groups are disproportionately affected, reflecting persistent challenges for Vosk in accurate transcription.

The en-0.22 model shows only modest gains, with the worst-performing linguistic group improving slightly to 70.89% and a 90th percentile of 34.68%. Within-linguistic group IQR ranged from 0.0% to 34.6%, with a median of 2.9%, again demonstrating a slight reduction. Absolute and relative parity gaps interestingly increased compared to small-en-0.15, to 62.24% and 8.19%, respectively, demonstrating that improvements for some high-performing groups came at the expense of greater disparity across the board. Overall, en-0.22 reduces high-end errors slightly, but variability within linguistic groups remains similar, and parity gaps actually increased, indicating that certain linguistic groups continue to pose challenges to ASR systems.

WER

For Vosk small-en-0.15, the mean WER was 41.8%, with a median of 39.1% and a relatively high standard deviation of 13.5%, reflecting substantial variability across linguistic groups. The en-0.22 model improved mean WER to 32.9% and median to 29.0%, reducing error rates for some groups, though variability remained (SD 11.7%). Notably, while high-error linguistic groups saw modest gains, certain low-error linguistic groups experienced little improvement, suggesting that model upgrades did not uniformly benefit all groups.

CER

Character-level errors mirror the trends of WER. For Vosk en-0.22, the mean CER was 14.2%, with a median of 11.9%, and a standard deviation of 8.0%, showing moderate error levels. Vosk small-en-0.15 had higher error rates, with a mean CER of 18.6% and a median of 16.7%, indicating worse performance and more variability. Despite this, Vosk en-0.22 still shows reasonable accuracy and a similar variability to Whisper’s base model.

KER

For Vosk en-0.22, the KER had a mean of 9.0%, with a median of 8.3% and a standard deviation of 10.1%. This indicates relatively low KER despite some variability. Vosk small-en-0.15 showed a mean KER of 24.4%, a median of 21.1%, and a higher standard deviation of 15.9%, suggesting higher errors for some linguistic groups. However, Vosk en-0.22 still performed well in accurately transcribing keywords.

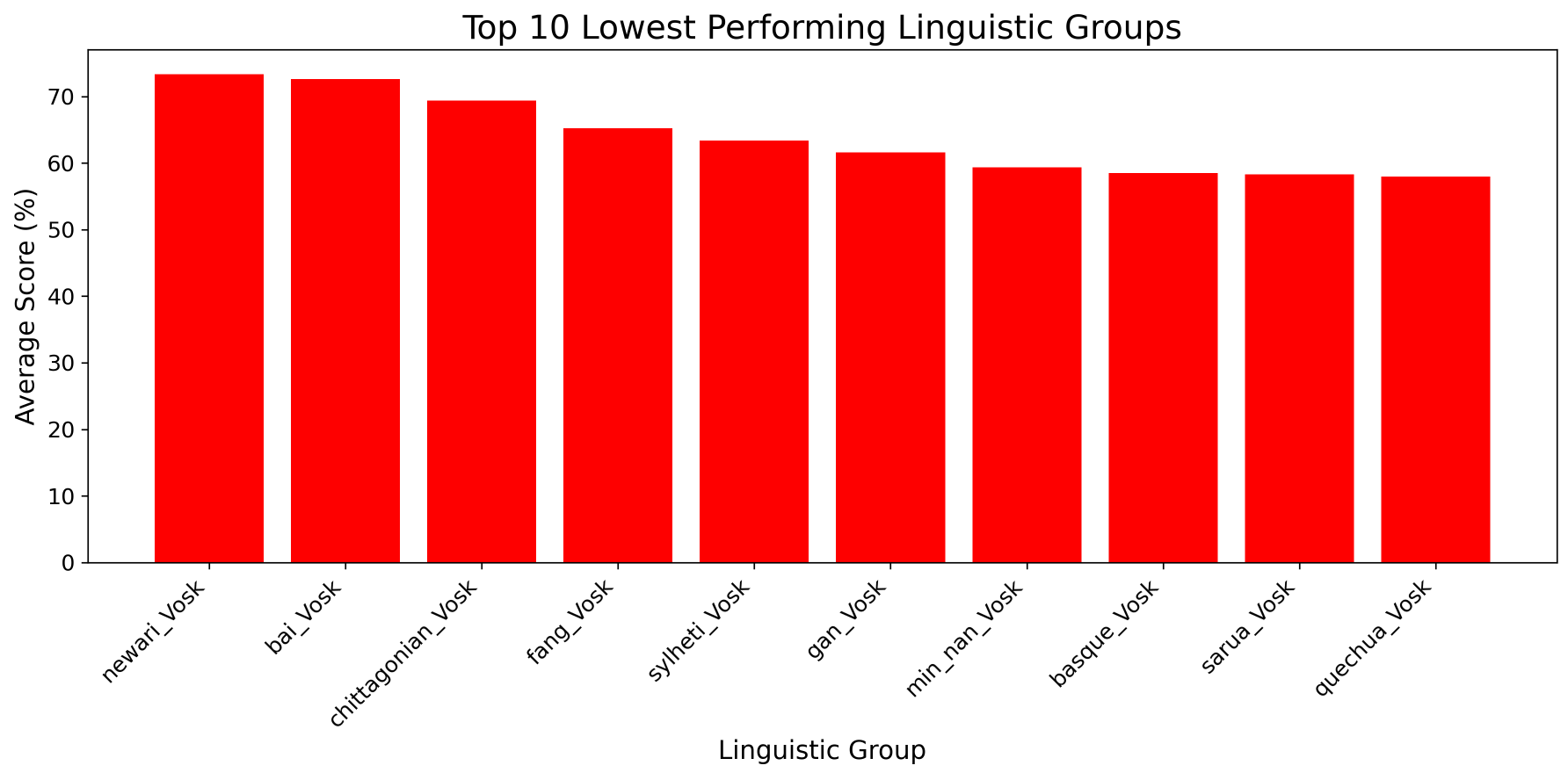

Linguistic Group Analysis

As demonstrated in Figure 15, the lowest-performing linguistic groups for Vosk en-0.22 included Bai, Chittagonian, Newari, and Gan. Among these, Bai and Newari stood out by ranking within the top three lowest-performing groups.

Figure 16 shows a very similar analysis for Vosk small-en-0.15, where the same set of groups (Bai, Chittagonian, Newari, and Gan) were also identified as some of the lowest performers in terms of accessibility. As with the analysis for the prior Vosk model, Bai and Newari appeared within the top three, confirming their consistent vulnerability to transcription errors not only across both Vosk models but across almost all the models tested in this study.

Most Frequently Missed Keywords

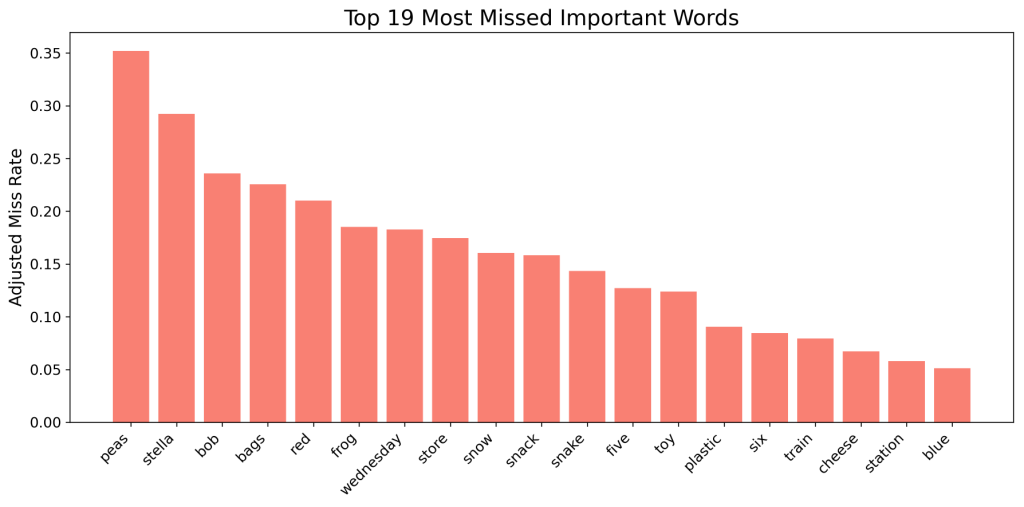

As shown below, Figure 17 presents the six most commonly missed keywords for Vosk small-en-0.15, while Figure 18 contains the six most missed keywords for Vosk en-0.22.

When evaluating Vosk small-en-0.15 and en-0.22, there is nearly a twofold reduction in keyword errors. For example, the word “Stella” was mistranscribed just under 60% of the time in Vosk small-en-0.15, but this dropped dramatically to just over 30% in the larger Vosk en-0.22 model. This represents the most substantial improvement, while the other frequently missed words also saw reductions. For both Vosk models, words such as “red,” “Stella,” and “bags” were the most commonly missed keywords. The word “red” was frequently transcribed as “rate,” while “bags” was often confused with “backs” or “box,” highlighting how short, single-syllable words may be a weakness for ASR systems.

Discussion

Interpretation of Results

The objective of this study was to identify performance disparities across different open-source ASR models, focusing on their ability to accurately transcribe spoken English from diverse linguistic groups, including underrepresented accents and dialects.

Benchmarking ASR Accessibility

In order to contextualize these findings more, it is important to compare the observed error rates against established benchmarks of usability. Prior research has shown that transcripts with a WER of 25% or lower are considered useful and usable for comprehension tasks, whereas transcripts with error rates approaching 45% become unsatisfactory from a user-experience standpoint36. Similarly, published descriptions of CER suggest that values below 5% reflect very strong performance, 5–10% remain acceptable, and error rates above 10% indicate a need for significant correction37. Placing the results within the previous thresholds, both Whisper large-v3’s and base’s mean WER and CER approaches the “excellent” standard and reflects strong performance, although its variability across accents is still an area for concern. By contrast, both Wav2Vec2 and Vosk models, with average WERs above 30% and CERs above 19% fall beyond the boundary where ASR systems are generally regarded as unusable. Unlike WER and CER, KER does not have a widely established usability threshold. However, we can still evaluate its impact by considering the role of keywords in preserving meaning. Because keywords often carry disproportionate weight in comprehension, even small increases in KER can have significant consequences for accessibility. In this study, both the Whisper large-v3 and base models achieved KERs in the low single-digit range, indicating strong preservation of important terms and aligning better with overall accessibility, despite the absence of a widely recognized threshold for interpreting KER. By contrast, both Wav2Vec2 and Vosk models averaged anywhere from 9–26%, suggesting they are more prone to losing intended meaning. These results overall suggest that Whisper demonstrates strong accessibility performance, particularly in preserving both accuracy and critical keywords, though variability still remains a relevant concern. In contrast, both Wav2Vec2 and Vosk perform poorly across all three metrics, indicating that they do not provide reliable accessibility for diverse speakers.

Regional Performance Patterns

Even the strongest tested model, Whisper, still struggled with specific linguistic groups, such as Sylheti and Newari. The presence of multiple South Asia linguistic groups in the low-performing sets suggests a regional performance pattern rather than just outliers. These linguistic groups often are exposed to languages with distinctive phonetic features, which may differ significantly from those typically captured in training data, potentially affecting ASR transcription accuracy38. For instance, English speakers influenced by Hindi speech patterns may produce sounds that do not exist in English, potentially challenging ASR systems trained predominantly on native

English speech38. The consistent difficulties and poor performance of these linguistic groups may suggest a systemic issue in how ASR systems process non-dominant accents. These identified discrepancies are significant because they reveal that even the highest-performing models still face substantial barriers when dealing with global majority accents, raising concerns about the accessibility of ASR systems for a wide range of speakers. The observed differences in model performance across accents reflect varying levels of phonetic generalization. Larger models like Whisper large-v3, with broader multilingual training, performed better overall, while smaller models struggled more consistently with linguistic variation.

Error Type and Phoneme Confusion Analysis

To better understand the underlying causes of the disparities observed in model performance, additional analysis was conducted to examine transcription errors both in terms of phoneme confusions and structural error types (substitutions, insertions, and deletions). This analysis was performed exclusively on Whisper large-v3, as it demonstrated the highest overall accuracy and the most consistent transcriptions across linguistic groups. Limiting the analysis to Whisper ensured that observed error patterns reflected real accent-related pronunciation effects rather than random noise caused by the model itself. Because Wav2Vec2 and Vosk exhibited substantially higher error rates, including them would have confounded the results by potentially introducing random mistakes that were completely unrelated to linguistic variation.

These analyses revealed that substitution errors were by far the most common, averaging 5.61 per audio file, compared to 0.57 insertions and 0.26 deletions. This indicates that most inaccuracies stem from phonetic misrecognition rather than from missing or added tokens, suggesting that the primary challenge for even the best ASR models lies in distinguishing between similar-sounding sounds. Insertions appear particularly elevated in some Creole or mixed-dialect varieties, like Liberian English (5.0 insertions per file) and Haitian Creole French (17.86 insertions per file), suggesting that ASR models occasionally produce extra tokens in these speech varieties, resulting in an increased number of insertion errors. Deletions, while generally low, were somewhat more pronounced in underrepresented languages with few samples, such as Uyghur (0.5 deletions per file, 6 files), Oriya (1.5 deletions per file, 2 files), and Krio (0.33 deletions per file, 1 file), all exceeding the overall average of 0.26 deletions per file. This suggests that limited representation in training data may contribute to deletion errors by ASR models.

Across all linguistic groups, the most frequently confused phonemes were /D/, /G/, and /N/, with recurrent substitutions including /D/↔/N/, /G/↔/B/, and /N/↔/S/. These confusions were consistently observed across multiple linguistic groups, such as Ganda, Indonesian, Swahili, and Estonian. Some phonemes are acoustically similar, like /D/ and /N/, which share similar alveolar articulation, so it is possible that they are more likely to be misrecognized by ASR systems.

Linguistic Patterns in Frequently Missed Keywords

As demonstrated in the results section, the same three words: “Stella,” “snow,” and “Wednesday,” always appeared among the top missed keywords for every ASR model tested. While the frequency and ranking of these errors varied across models, the recurrence of these same four keywords indicates that the issue may not be isolated to training data alone, but could also reflect deeper architectural limitations in how current ASR models process certain phonetic structures.

Each of these words presents similar linguistic challenges that can impact ASR transcription accuracy. For example, “Stella” (/ˈstɛlə/) and “snow” (/snoʊ/) both begin with consonant clusters (/st/ and /sn/), and “Wednesday” (/ˈwɛnzdeɪ/) contains an embedded consonant cluster (/nz/). Consonant clusters, which are groups of two or more consonant sounds that occur together without a vowel in between, have been found to cause mistranscription in accented speech39. Additionally, “Wednesday” has non-transparent orthography, meaning the spelling doesn’t clearly match its pronunciation in a one-to-one manner40. Specifically, the “d” in the middle is written but usually not pronounced, creating a mismatch between how it looks and how it sounds. This discrepancy may lead to speaker mispronunciation, especially among non-native English speakers unfamiliar with its irregular spelling. In these cases, the resulting audio may differ from the expected pronunciation, potentially increasing transcription errors. Therefore, the frequent misrecognition of “Wednesday” may stem not only from model limitations but also from human pronunciation variability due to the word’s non-transparent orthography.

Significance and Implications

The results of this study reveal not only the limitations of current ASR models, but also the potentially systemic nature of accent-based disparities in speech recognition technology. While Whisper performed better than Wav2Vec2 and Vosk across all tested metrics, the ongoing performance disparities with certain global majority linguistic groups like Sylheti, Haitian Creole, and Newari reveal a deeper issue in the design of ASR models. These findings suggest that, despite advancements, existing ASR systems remain inadequate in providing universal accessibility, highlighting the need for further efforts to completely account for linguistic diversity.

One of the critical implications of this study is the understanding that ASR systems must move away from general accuracy and start focusing more on equitable inclusivity. This involves addressing the biases in both the training data and model design, which continue to disadvantage speakers from underrepresented linguistic backgrounds. As shown by the varying performance of Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk, even ASR systems trained on large, multilingual datasets fail to be accessible for many global majority accents. This is particularly concerning as the use of ASR expands across essential sectors, such as customer service, healthcare, and accessibility services. When ASR systems fail to transcribe the speech of speakers from these groups accurately, they

reinforce existing inequalities. As ASR technology continues to evolve, a focus on inclusivity and accessibility can guide future advancements, ensuring that all users have equal access to the benefits of speech technologies, no matter their linguistic background.

Limitations and Future Work

While this study reveals the accessibility of ASR systems across a diverse range of accents, several limitations must be acknowledged. The dataset, while diverse, was constrained by the range of accents and dialects it covered. This dataset may not entirely represent the global linguistic landscape. To address this, future research should aim to utilize a broader dataset that includes a wider variety of accents and dialects to ensure a more comprehensive evaluation. Additionally, the use of a single corpus (the Speech Accent Archive) introduces limitations. Because it relies on a single, controlled passage, it does not contain the variability of spontaneous or conversational speech, which may affect how well these findings generalize to real-world contexts. To address this, future research should aim to incorporate multiple datasets that include both read and natural speech, ensuring a more comprehensive evaluation of ASR performance.

Another limitation lies in the potential for bias within the dataset. Despite efforts to normalize volume levels, there were clear differences in audio quality between groups. Some audio samples may have been recorded in environments with varying microphone quality, background noise, or other inconsistencies. This limitation is particularly relevant in the context of this study, as it may have significantly impacted the accuracy of transcription for some groups. For future work, one way to address this limitation would be to standardize the recording conditions more rigorously, ensuring consistent microphone quality, controlled background noise, and clear speech. Additionally, a similar dataset could be developed for the future, using high-quality, professionally recorded samples to minimize variability across linguistic groups. By creating a more consistent dataset, future studies would be able to more accurately assess the ASR models’ performance and ensure a fairer evaluation of accessibility across all linguistic groups.

Additionally, certain linguistic groups were represented by only a small number of audio samples, which may limit the reliability of conclusions drawn for those groups and make them more sensitive to outliers. Future work could expand on these results by collecting additional recordings for certain underrepresented groups to improve robustness and ensure more reliable evaluation.

Beyond dataset limitations, this evaluation only included three open-source ASR models, and there are numerous other widely utilized systems that may provide different insights. Technology that utilizes ASR as a core component of its functionality, such as Google’s Speech-to-Text, Apple’s Siri, and Amazon’s Alexa, might exhibit different performance patterns across accents and linguistic backgrounds. Future research should expand the scope to include more ASR models, such as these.

Conclusion

This research explored how the accessibility of ASR systems varies across speakers from different linguistic backgrounds, with a focus on identifying potential future improvements. The findings underscore a crucial need to address accessibility gaps in ASR technology, particularly for speakers with diverse accents and dialects. While ASR systems, such as Whisper, Wav2Vec2, and Vosk, have made significant strides, their performance remains inconsistent across various linguistic groups. The findings reveal that, despite improvements in multilingual models, notable disparities persist in transcription accuracy, especially for underrepresented accents. This gap continues to highlight a pressing issue: unequal representation in training data, which continues to disadvantage marginalized communities.

Beyond data imbalance, model architecture itself may also contribute to these disparities, as current systems often fail to accurately transcribe audio across specific linguistic features found in many of these linguistic groups. In particular, certain structures, such as consonant clusters or non-transparent orthography, consistently lead to higher error rates, as demonstrated by frequently mistranscribed words like “Stella,” “Snack,” and “Wednesday.”

The unique contribution of this study lies in its cross-model, multi-metric evaluation combined with keyword-level error analysis, providing a more nuanced view of accessibility than prior work that focused primarily on overall WER. By examining the underlying linguistic structures of commonly missed keywords, this study further advances the field and offers a pathway for more inclusive model development.

Moving forward, improving inclusivity will require training ASR models on more diverse datasets and adjusting architectures to handle varied linguistic features. Although current ASR technologies represent significant progress, ensuring equitable performance across all linguistic groups remains a pressing challenge. As ASR technology becomes increasingly integrated into everyday life, further research is essential to creating more accessible and inclusive solutions.

Appendix

Code – Link to Github Repository

The code used for this research is publicly available in the GitHub Repository below. It includes all relevant code and files necessary to reproduce these results:

References

- Hannun A. (2021). The History of Speech Recognition to the Year 2030. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2108.00084. https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.00084 [↩]

- Ruan, S., Wobbrock, J. O., Liou, K., Ng, A., & Landay, J. (2016). Comparing Speech and Keyboard Text Entry for Short Messages in Two Languages on Touchscreen Phones. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:1608.07323. https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.07323 [↩]

- Koenecke, A., Nam, A., Lake, E., Nudell, J., Quartey, M., Mengesha, Z., Toups, C., Rickford, J. R., Jurafsky, D., & Goel, S. (2020). Racial disparities in automated speech recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7684-7689. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915768117 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Río, M., Miller, C., Profant, J., Drexler-Fox, J., Mcnamara, Q., Bhandari, N., Delworth, N., Pirkin, I., Jetté, M., Chandra, S., Peter, H., & Westerman, R. (2023). Accents in Speech Recognition through the Lens of a World Englishes Evaluation Set. Research in Language. 21. 225-244. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376941218 [↩]

- Martin, J. L., & Wright, K. E. (2023). Bias in automatic speech recognition: The case of African American Language. Applied Linguistics, 44(4), 613–630.https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amac066 [↩] [↩]

- Martin, J. L., & Wright, K. E. (2023). Bias in automatic speech recognition: The case of African American Language. Applied Linguistics, 44(4), 613–630 [↩]

- Tatman, R. (2017). Gender and Dialect Bias in YouTube’s Automatic Captions. Proc. First ACL Workshop on Ethics in Natural Language Processing (pp. 53-59). https://aclanthology.org/W17-1606.pdf [↩]

- Prabhu D., Jyothi P., Ganapathy S., & Unni V. (2023). Accented Speech Recognition With Accent-specific Codebooks. Proc. 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 7175–7188).https://aclanthology.org/2023.emnlp-main.444.pdf [↩]

- Tatman, R., & Kasten, C. (2017). Effects of Talker Dialect, Gender & Race on Accuracy of Bing Speech and YouTube Automatic Captions. Proc. Interspeech 2017 (pp. 934-938). https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2017/tatman17_interspeech.html [↩] [↩]

- Patel, T., Hutiri, W., Ding, A. Y., & Scharenborg, O. (2025). How to Evaluate Automatic Speech Recognition: Comparing Different Performance and Bias Measures. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2507.05885v1. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.05885v1 [↩]

- Patel, T., Hutiri, W., Ding, A. Y., & Scharenborg, O. (2025). How to Evaluate Automatic Speech Recognition: Comparing Different Performance and Bias Measures. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2507.05885v1. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.05885v1 [↩]

- Morris, A. C., Maier, V., & Green, P. (2021). From WER and RIL to MER and WIL: Improved Evaluation Measures for Connected Speech Recognition. Proc. Interspeech 2004. https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2004/morris04_interspeech.html [↩]

- Thennal, D. K., James, J., Gopinath, D. P., & Ashraf, M. K. (2025). Advocating Character Error Rate for Multilingual ASR Evaluation. Proc. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025 (pp. 4926–4935). https://aclanthology.org/2025.findings-naacl.277/ [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Park Y., Patwardhan S., Visweswariah K., & Gates S. (2008). An Empirical Analysis of Word Error Rate and Keyword Error Rate. Proc. Interspeech 2008 (pp. 2070-2073). https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2008/park08b_interspeech.pdf [↩] [↩]

- Kim, S., Arora, A., Le, D., Yeh, C.-F., Fuegen, C., Kalinli, O., & Seltzer, M. L. (2021). Semantic Distance: A New Metric for ASR Performance Analysis Towards Spoken Language Understanding. Proc. Interspeech 2021 (pp. 1977-1981). https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2021-729 [↩]

- Sasindran, Z., Yelchuri, H., & Prabhakar, T. V. (2024). SeMaScore: A new evaluation metric for automatic speech recognition tasks. Proc. Interspeech 2024 (pp. 1-5). https://arxiv.org/html/2401.07506v1 [↩]

- Pratap V., Sriram A., Tomasello P., Hannun A., Liptchinsky A., Synnaeve G., & Collobert R. (2020). Massively Multilingual ASR: 50 Languages, 1 Model, 1 Billion Parameters. arXiv. preprint arXiv:2007.03001. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.03001 [↩] [↩]

- Conneau A., Baevski A., Collobert R., Mohamed A., & Auli M. (2020). Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning for Speech Recognition. arXiv. preprint arXiv:2006.13979. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.13979 [↩]

- Conneau A., Baevski A., Collobert R., Mohamed A., & Auli M. (2020). Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning for Speech Recognition. arXiv. preprint arXiv:2006.13979. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.13979 [↩]

- Prabhu, D., Jyothi, P., Ganapathy, S., & Unni, V. (2023). Accented Speech Recognition with Accent-specific Codebooks. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2310.15970. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.15970 [↩]

- Hinsvark, A., Delworth, N., Del Rio, M., McNamara, Q., Dong, J., Westerman, R., Huang, M., Palakapilly, J., Drexler, J., Pirkin, I., Bhandari, N., & Jette, M. (2021). Accented Speech Recognition: A Survey. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2104.10747. https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.10747 [↩]

- Graham C., & Roll N. (2024). Evaluating OpenAI’s Whisper ASR: Performance analysis across diverse accents and speaker traits. JASA Express Letters. 4(2).

https://pubs.aip.org/asa/jel/article/4/2/025206/3267247/ [↩]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Halpern, B. M., Patel, T., & Scharenborg, O. (2022). Mitigating bias against non-native accents. Proc. Interspeech 2022 (pp. 3168-3172). https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2022/zhang22n_interspeech.pdf [↩]

- Ngueajio, M., & Washington, G. (2022). Hey ASR System! Why Aren’t You More Inclusive?: Automatic Speech Recognition Systems’ Bias and Proposed Bias Mitigation Techniques. A Literature Review. HCI International 2022 – Late Breaking Papers: Interacting with eXtended Reality and Artificial Intelligence (pp. 421-440). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365722662 [↩]

- Okoye, O (2024). Whisper: Functionality and Finetuning. Medium. https://medium.com/@okezieowen/whisper-functionality-and-finetuning-ba7f9444f55a [↩]

- Wang, Y., & Yang, Y. (2025). Normalization through Fine-tuning: Understanding Wav2vec 2.0 Embeddings for Phonetic Analysis. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2503.04814v1. https://arxiv.org/html/2503.04814v1 [↩]

- Emergent Mind. (2025). Whisper Decoder Embeddings. https://www.emergentmind.com/topics/whisper-decoder-embeddings [↩]

- Wenzel K., Devireddy N., Davison C., & Kaufman G. (2023). Can Voice Assistants Be Microaggressors? Cross-Race Psychological Responses to Failures of Automatic Speech Recognition. Proc. 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14). https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3544548.3581357 [↩] [↩]

- Wenzel K., & Kaufman G. (2024). Designing for Harm Reduction: Communication Repair for Multicultural Users’ Voice Interactions. Proc. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-17). https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3613904.3642900 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Weinberger, Steven. (2015). Speech Accent Archive. George Mason University. Retrieved from http://accent.gmu.edu [↩]

- DiChristofano, A., Shuster, H., Chandra, S., & Patwari, N. (2022). Global performance disparities between English-language accents in automatic speech recognition. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.01157 [↩]

- Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Xu, T., Brockman, G., McLeavey, C., & Sutskever, I. (2022). Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2212.04356. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.04356 [↩] [↩]

- Schneider, S., Baevski, A., Collobert, R., & Auli, M. (2019). wav2vec: Unsupervised Pre-training for Speech Recognition. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:1904.05862. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.05862 [↩]

- Oye, E., Daniels, N. (2025). Speech Recognition in Real-Time Applications: Enhancing Accuracy with Vosk and Custom Models. Retrieved from ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391716898 [↩]

- OpenAI. (2025). Whisper large-v3. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/openai/whisper-large-v3 [↩]

- Munteanu, C., Baecker, R., Penn, G., Toms, E., & James, D. (2006). The effect of speech recognition accuracy rates on the usefulness and usability of webcast archives. Proc. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 493–502). https://doi.org/10.1145/1124772.1124848 [↩]

- aiOla. (2025). Character Error Rate (CER). https://aiola.ai/glossary/character-error-rate [↩]

- Patil, V. V., & Rao, P. (2016). Detection of phonemic aspiration for spoken Hindi pronunciation evaluation. Journal of Phonetics, 54, 202–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2015.11.001 [↩] [↩]

- Emara, I. F., & Shaker, N. H. (2024). The impact of non-native English speakers’ phonological and prosodic features on automatic speech recognition accuracy. Speech Communication, 157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2024.103038 [↩]

- Taguchi, C., & Chiang, D. (2024). Language complexity and speech recognition accuracy: Orthographic complexity hurts, phonological complexity doesn’t. arXiv. Preprint arXiv:2406.09202. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.09202 [↩]