Abstract

Joan of Arc occupies an uneasy place in European cultural memory—tried and executed as a heretic, yet canonized five centuries later. Her image has remained both celebrated and contested. Early portraits from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries are rare and uncertain, reflecting the church’s ambivalence. By the nineteenth century she reemerged with new force: painters such as Ingres, Delaroche, and Bastien-Lepage presented her as a national heroine and virgin warrior, fusing devotion with patriotism. In the twentieth century her likeness spread through new media, serving at once as a suffrage emblem and a tool of wartime propaganda. Contemporary artists, in turn, have revisited her fragmented iconography to express the shifting anxieties of our time. This paper argues that Joan’s significance lies less in a fixed depiction than in the continual reimagining of her image. Her representations oscillate between feminine ideal and martial authority, unity and fracture, belief and doubt. Through an interdisciplinary approach that combines art-historical analysis, cultural historiography, and gender theory, this paper traces her visual afterlives from medieval icons to contemporary art, revealing how her instability, rather than certainty, ensures her endurance.

Keywords: Joan of Arc, art history, religion, gender studies, symbolism, iconography, European painting, nationalism, feminism, visual culture

Introduction

Joan of Arc is a figure that resists containment. Few names in European memory have been pulled in so many directions, asked to stand for such different and even opposing ideas. She was burned as a heretic in 1431 and remembered for centuries as a dangerous visionary, only to be rehabilitated and declared a saint by the Catholic Church in 1920. This dramatic reversal made her a pliable figure for artists seeking to embody ideas of faith, resistance, and gender. Over the span of five centuries, Joan has appeared not only as a holy martyr or a suspected witch, but as a shifting symbol reflecting the ideological preoccupations of each age.

This study approaches these transformations through the lens of cultural memory. Cultural memory refers not simply to recorded history or to what individuals remember, but to the shared ways societies reconstruct and transmit the past through collective symbols and artistic forms. It is less concerned with factual continuity than with the meanings that each generation chooses to renew. Joan of Arc’s image exemplifies this process: rather than preserving her as a historical figure, artists and audiences continually re-create her to express their own faith, doubt, and national or spiritual identity. Images of Joan function as temporal nodes in which different historical moments converge, allowing memory to operate as a recursive, rather than chronological, process.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, images of her were rare. Neither the monarchy nor the church had any reason to honor someone condemned at the stake. When she did appear, it was usually in pamphlets or in texts rather than lasting artworks. Shakespeare and Voltaire chose to depict her as a witch, an image very different from the saint she would later become1‘2. By the nineteenth century, however, her role shifted. When France was searching for symbols of revolution and unity, Joan was reborn as a patriotic heroine. Painters like Hermann Stilke and Dante Gabriel Rossetti presented her as a virgin warrior, guided by divine voices, who could restore both crown and country3‘4. By then she was no longer a suspect heretic but a national saint, her purity and sacrifice pressed into service for a nation that wanted Catholic renewal and secular pride at the same time.

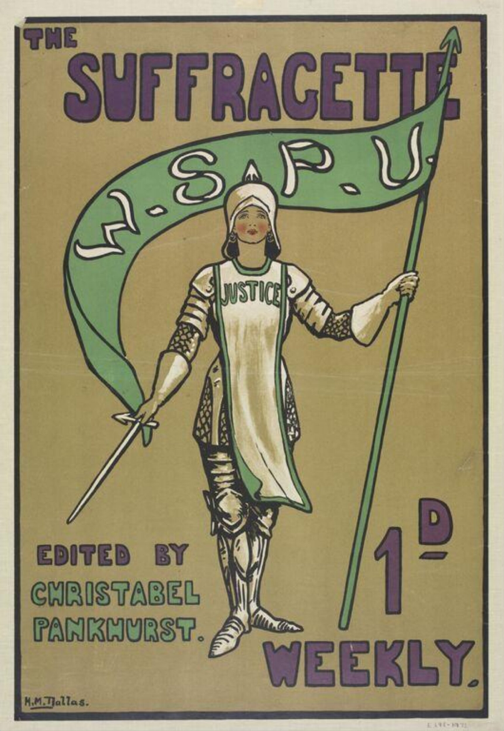

In the early twentieth century, traditional history painting and portraiture lost their central place in European art in the wave of modernism5. Development of photography and mass print technologies, along with rapidly changing thoughts about art amid pouring avant-garde movements, pulled visual culture away from academic figuration and the production of portrait painting in general. At first glance, this might seem to have diminished Joan’s presence in the arts. Yet her symbolic power did not wane; instead of painted canvases, Joan appeared in public demonstrations, political posters, and popular iconography. In fact, her symbolic reach expanded. One telling example is suffragette Elsie Howey’s appearance on 17 April 1909, riding a white horse dressed as Joan of Arc at the welcome procession for Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s release from Holloway Prison; the image circulated widely and helped translate Joan’s medieval warrior ethos into a living emblem for the suffrage campaign6. Unlike the previous oil paintings, these modern appropriations circulated through reproducible media, absorbing Joan into the collective imagination as a living emblem of social struggle.

Surprisingly, the life of Joan of Arc is unusually well documented7. One of the first major historical work was done by Jules Michelet, whose monumental seventeen-volume History of France (1833–1867) devoted three chapters to Joan, which were later published as a separate book8. His student, Jules Quicherat, edited and published Condemnation and Rehabilitation Trials of Joan of Arc Called the Maiden (1841–1849), compiling the records of her condemnation and retrial. This work is regarded as the first presentation of the “historical Joan” to the public and had a major impact on her subsequent canonization and reassessment8.

Much of the scholarship that followed sought to trace whether the images of Joan reconstructed by artists across disciplines aligned with historical fact. Nora M. Heimann’s Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700–1855): From Satire to Sanctity (2005) is representative of this approach7. Other scholarship, drawing on the lenses of women’s studies and religious studies, has focused on the diabolic imagery projected onto Joan—shaman, mystic, and witch—examining her more deeply within the mystical traditions of the late Middle Ages. A key example is Anne Llewellyn Barstow’s Joan of Arc: Heretic, Mystic, Shaman (1986)9.

Despite Joan’s ongoing cultural prominence, art-historical studies of her image remain limited. Marina Warner’s Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (1981) remains the most comprehensive study of Joan’s visual records, but it tends to focus on sorting through her biographical facts by means of a catalogue of images, the scope of which is largely limited to works before 1900 (M. Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism). Moreover, as Barstow has observed, it predates the advances of contemporary feminist and cultural theory. Since the iconography of Joan has migrated into new media in the twentieth century, namely film, theatre, and popular culture, representations of Joan in literary and cinematic history have continued to attract scholarly attention. However, these studies are often confined to the cinematic genre, leaving a lack of bridges to a more comprehensive discussion of Joan of Arc as an enduring iconography in the field of art.

This paper seeks to fill that gap. Following Warner yet extending into more recent works, it explores how Joan’s image symbolizes tensions between female body and male heroism; between divine inspiration and heretical suspicion; and between unstable identity and the truths manifested through it. In this context, the term “feminine” is treated not as a stable essence but as a constructed ideal that shifts according to historical and ideological needs. The feminine attached to Joan’s image oscillates between purity and power, sanctity and eroticization, reflecting the broader mechanisms through which visual culture defines and confines womanhood. Ambiguity is approached as an analytical operator, an active condition that exposes how historical narratives, artistic forms, and gendered identities intersect and unsettle one another.

Central to these tensions is the question of gender. This study positions it as the structural axis through which Joan’s image has been produced, contested, and reimagined. Feminist readings, including those by scholars such as Karyn Sproles, have shown how representations of visionary women are often disciplined into culturally acceptable forms, and this study builds on that insight. By tracing her transformations from painted icon to suffrage costume, and later to a cultural-historical symbol in museum and gallery settings, this study shows how artists today employ Joan’s image to express the uncertainties of modern life. This examination of Joan’s image provides a lens on the interplay between art and ideology, revealing how societies project their fears and desires onto an enduring female figure. Ultimately, the image itself is understood not merely as a representation of history but as a form of historical and symbolic knowledge, one that participates in producing the realities it appears to depict.

Conceptual Framework

This study is grounded in three interrelated concepts—ambiguity, gender, and cultural memory—which together frame the analysis of Joan of Arc’s image. Ambiguity functions here as an analytical operator rather than a lack of clarity: it exposes how conflicting meanings coexist within representations of Joan, linking visual, historical, and ideological tensions. Gender is treated as a structural principle through which these meanings are organized, highlighting how artistic forms construct and contest notions of femininity, sanctity, and authority. Cultural memory provides the temporal and collective dimension of the study, describing how images reconstitute the past within the present through acts of reinterpretation. Read together, these concepts allow the analysis to move beyond iconographic description toward an examination of how the image of Joan participates in the production of historical and symbolic knowledge.

Methods

This study takes the form of an interdisciplinary review focused on visual art produced from the fifteenth century and onwards. Primary sources include artworks accessed through academic databases, digitized manuscripts, and images provided by museums and other digital archives. For the works’ visual analysis, general knowledge of formal principles of art and design was employed (S. Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing about Art), in addition to online museum catalogue texts and first-hand descriptions provided by the artists. Artworks were selected based on their historical influence and accessibility through credible academic and museum sources. Each work either marked a shift in Joan’s visual interpretation or exemplified a broader ideological transformation within its period. Secondary sources comprise biographies, such as Vita Sackville-West’s Saint Joan of Arc (1936), and other scholarly works that consider Joan of Arc in the modern perspective of sociological and gender studies, such as texts by Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Nora Heimann, Johanna Gauer Edge, and Justyna Sempruch. These provide frameworks for interpreting Joan’s shifting image in relation to gender construction, witchcraft as cultural anxiety, and the politics of representation.

Methodologically, this paper positions itself between a historical study of representations and a discursive analysis of images. It does not aim to construct a chronological history of Joan’s depictions, but to examine how visual forms participate in the ongoing production of meaning within cultural memory. In this sense, the approach is archaeological in spirit, tracing how particular motifs resurface and gain new functions across time.

In terms of artwork samples, it restricts the scope of media to works of art that directly engage the problem of representing Joan of Arc. The analysis considers multiple criteria: compositional strategy, iconographic choices, sociopolitical context, and the critical reception of each work. These dimensions allow the study to trace not only visual change but also shifts in cultural discourse surrounding sanctity, gender, and nationalism. While literary, theatrical, and cinematic portrayals form a significant part of her cultural afterlife, they were set aside in order to concentrate on visual strategies of depiction. Sculptural works as in traditional statue format have also been excluded, because they largely function as commemorative monuments repeating conventional images of the mounted warrior or Catholic saint. Within these parameters, the sample includes works ranging from early manuscript miniatures to nineteenth-century paintings by Ingres, Delaroche, and Bastien-Lepage,and extends to twentieth-century mass imagery such as suffrage banners and wartime propaganda. Contemporary works made in the 2000s, that appropriate Joan are also examined, which in its nature incorporating diverse materials, particularly for how they foreground her multifaceted identities.

Although the artworks are discussed in roughly chronological order, this structure serves an analytical rather than historical purpose. Chronology here operates as a framework to visualize the recurrence and reconfiguration of Joan’s instability across time. While the study draws upon the iconographic method to trace visual motifs across time, it also acknowledges its limitations. Rather than assuming fixed symbolic meanings, the analysis treats iconography as a dynamic process shaped by changing social and ideological contexts.

Thematic Analysis

Contained and Feminized

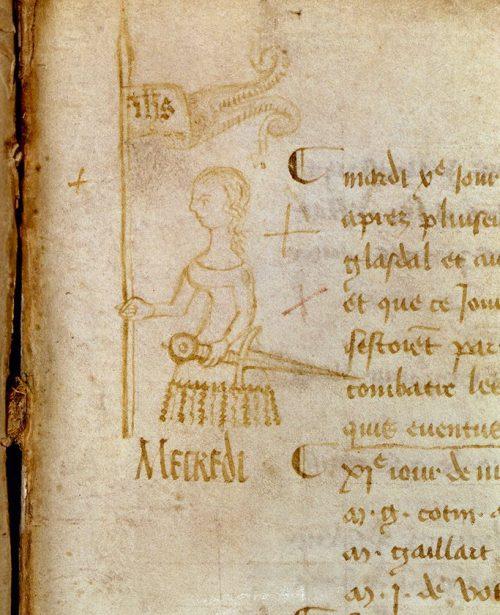

From the outset, Joan’s image was marked by ambivalence than by commemoration. The earliest sketch is a small, schematic drawing, appearing in the margin of a 1429 register by Clément de Fauquembergues, the secretary of the Parlement of Paris, records her victory at Orléans as a hasty notation of an event (Fig 1). Later generations, with no authentic likeness to follow, chose to borrow from existing models of female heroism rather than inventing a realistic portrait based on testimonial facts.

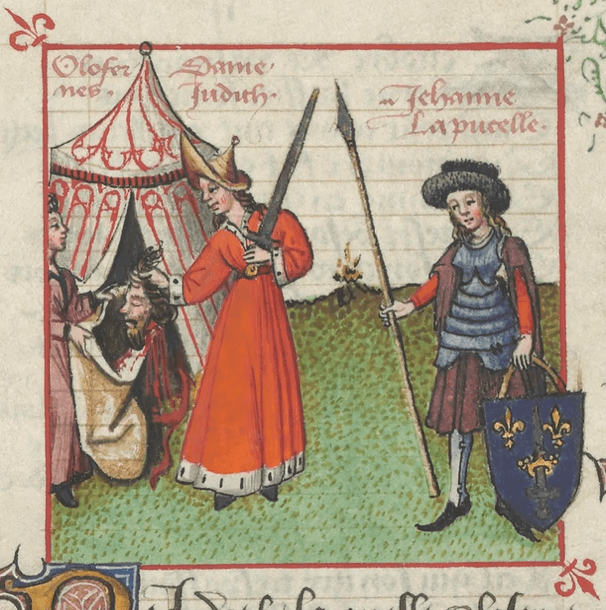

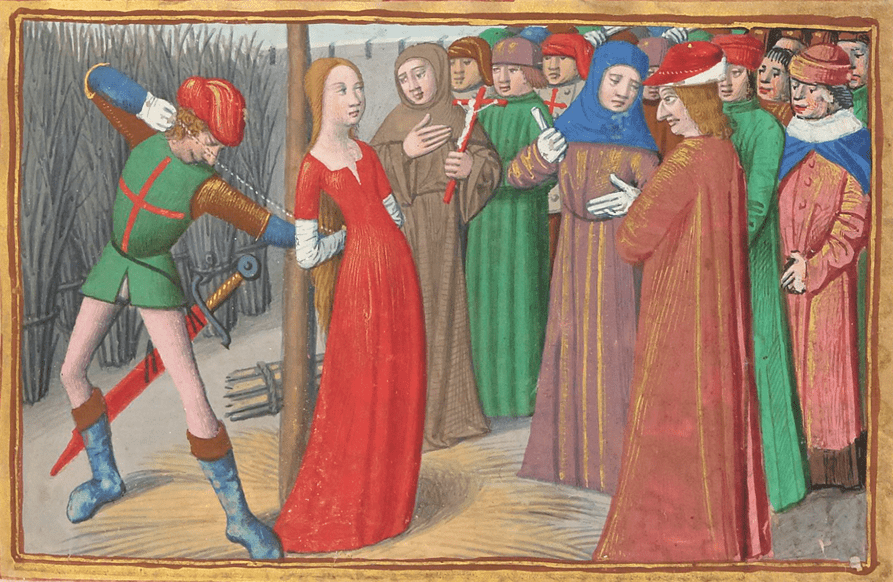

One such model was Judith, the Old Testament widow who seduced and beheaded Holofernes. In Martin le Franc’s Le Champion des Dames (c. 1451), Joan appears beside her, dressed in a long gown (Fig 2). The pairing is telling, because Judith embodied both courage and the dangerous allure of the femme fatale, a woman whose sexuality made her both heroic and suspect. Aligning Joan with her suggests admiration but also an effort to fold an unprecedented maiden-warrior into an already legible archetype. Martial d’Auvergne’s Les Vigiles du Roi Charles VII (1484) continued this strategy, depicting Joan as a pious blonde martyr rather than the armored commander with short black hair as described in contemporary records (Fig 3). As Barstow notes, the persecuted female prophet was a familiar role; it was easier for artists to cast Joan in this lineage than to invent a wholly new iconography13.

As Figure 4 shows, the portrait commissioned in 1576 by the aldermen of Orléans extends this trend of feminization. Joan stands as a graceful young woman in a dark gown, holding a sword upright but stripped of martial presence. Strikingly, this representation disregards the abundant testimony emphasizing her male attire. The overall composition, clothing, and posture closely recall an earlier portrait of Judith from around 1530 (Fig. 5). Again, the historical Joan, condemned as “a disorderly woman dressed as a man,” was visually rewritten as a safe, courtly lady acceptable to patriarchal decorum (V. Sackville-west, Saint Joan Of Arc.)

The Making of a National Icon

From the eighteenth century onward, Joan of Arc increasingly appeared as a national icon, mobilized to inspire loyalty either to monarchy or to nation8. Yet even when pressed into service as a symbol of political unity, her image was consistently tempered by signs of femininity that distanced her from the raw militancy.

The engraved portrait designed by Sergent and printed by Blin in 1787 exemplifies this tendency (Fig 6). Emerging from a royalist tradition of celebrating national heroes, the print transforms Joan into a decorative emblem of dynastic continuity and loyalty to the crown. She wears armor, adorned with ribbons and paired with jewelry at her neck. Her flushed cheeks and smile make the figure appear a courtly heroine than a disruptive mystic or commander17.

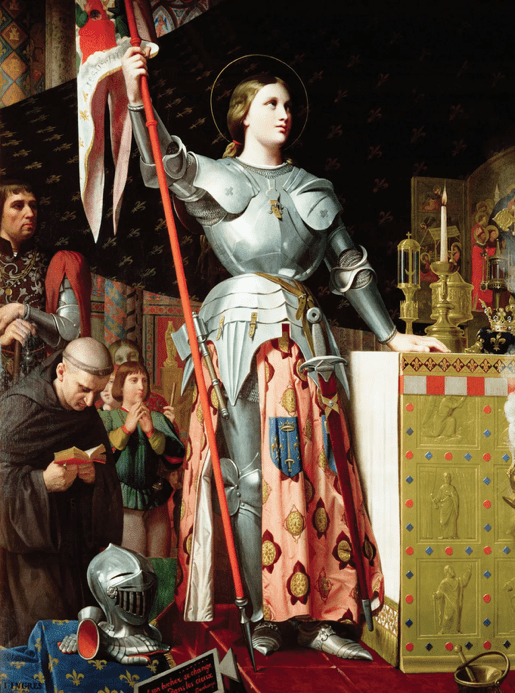

A century later, Ingres’s Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII (1854) reframes her for a post-Revolutionary France seeking moral and spiritual stability (Fig 7). She stands at the altar in a monumental way, in gleaming armor, with her long blond hair and patterned gown that soften the martial setting. The inscription below, “Et son bûcher se change en trône dans les cieux (And her pyre turns into a throne in the heavens)”, elevates her to sanctified martyr. The halo painted behind her head explicitly marks her sanctity. Here, femininity and spirituality work together to reconcile Joan’s military authority with nineteenth-century gender expectations (M. Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism).

Similar strategies were employed in John Everett Millais’s Joan of Arc (1865) (Fig 8). British artists rarely engaged with the image of Joan of Arc; however, Millais’s work, produced in Victorian England, coincided with the revival of history painting in the 1860s and connected Joan to broader European concerns with faith and sacrifice8. The artist presents her kneeling in prayer, grasping a heavy sword. Her armor is fused with a red skirt, fusing martial and feminine symbols. The stark black background directs attention to her face, where pain, doubt, and ecstatic faith intermingle, rendered with markedly feminine features. The emotional emphasis lies in her bodily presence with youthful fragility, qualities that would have resonated with a Victorian audience preoccupied with moral exemplars20.

In these compositions where her armor gleams but her body remains modest and contained, chastity and courage coexist, suggesting that the female body must be purified to become a bearer of divine purpose. This visual rhetoric constructs gender not merely as an attribute but as a regulating system: Joan’s sanctity is legible only when framed through modesty, submission, and control. Such framing reveals how nineteenth-century visual culture disciplined the female visionary into an acceptable moral form while claiming to celebrate her heroism.

Visionary or Witch-like Imagery

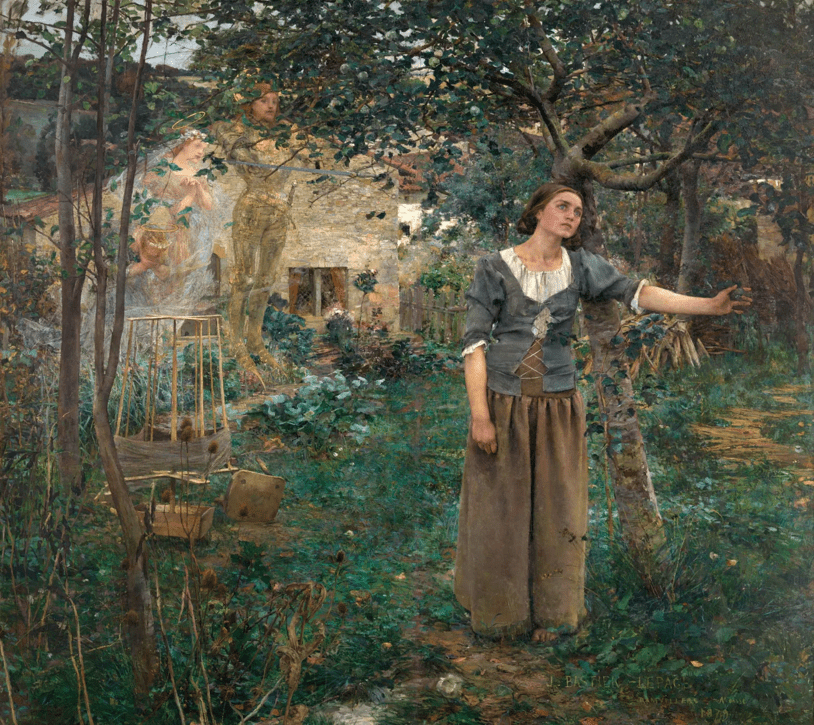

Whereas eighteenth and nineteenth-century nationalist images often feminized Joan by setting a beautiful face within masculine armor, another current showed her as an ordinary girl in women’s dress, marked by the unease of a visionary who claimed divine voices. In Bastien-Lepage’s rendering, Joan appears without armor or weapon, her rumpled gown and luminous skin underscoring a vulnerable femininity (Fig 9). In her plain peasant garb, she stands in the foreground with the spectral figures of the three saints (Saint Michael, Catherine, and Margaret) behind her back; her psychic unrest is communicated with her face, tilted body and distant gaze that seem to foreshadow the ordeals to come. The artist presents her at once rooted in earthly reality and touched by the otherworldly, as if she is not settled in her departure from prescribed gender roles22.

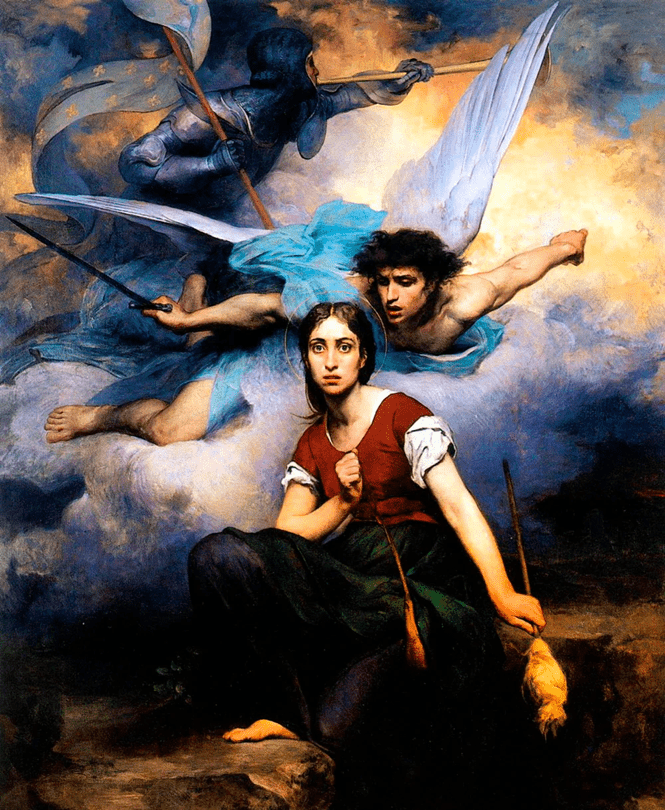

That Joan heard the divine voices of remained a central and contested fact about her life, from her trial through to her death. Other depictions of this decisive calling moment share a crucial feature: unlike Marian scenes of visitation, Joan “hearing voices” is consistently portrayed with an aura of instability. This instability reaches its most charged form in depictions of Joan encountering divine calling, where artistic imagination shades into witch-like imagery. In Eugène Thirion’s 1876 painting, angelic beings surround a transfixed Joan, their fiery presence casting her less as saint than as haunted medium (Fig 10). Gaston Bussière likewise imagines her amid swirling color and vision, her eyes lifted, her body overtaken by forces at once divine and dangerous (Fig 11). Her gestures and expressions of fear in both works suggest that artists have intertwined Joan hearing divine voices with tropes of possession, which blur inspiration with sorcery.

Artistic Appropriation and Symbolic Uses

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Joan’s image no longer functioned primarily as portraiture or historical record. However, she emerged as a cultural emblem, appropriated across artistic and political registers. In this phase, her likeness mattered less than her symbolic resonance, and she became a flexible signifier.

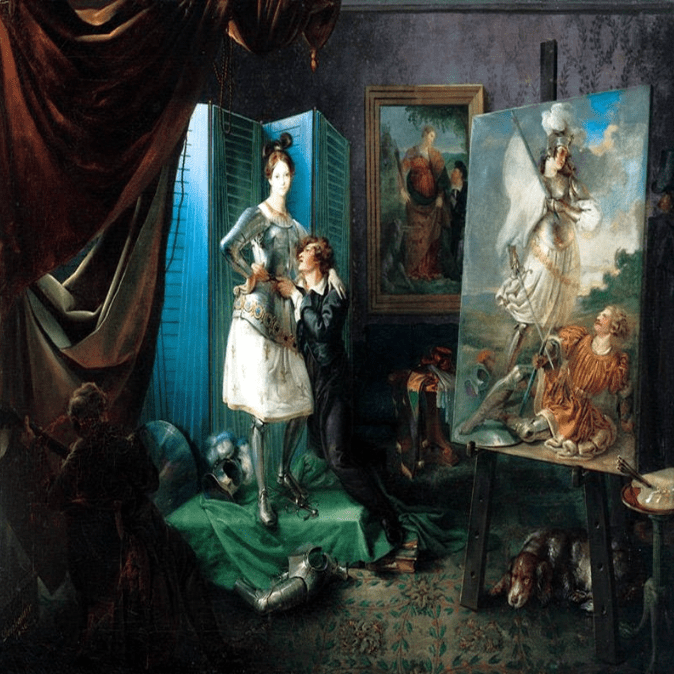

In Paul Delaroche’s Joan Interrogated by the Cardinal of Winchester (1824), Joan sits bound in a dim prison chamber, her youthful face lifted with a mixture of defiance and resignation (Fig 12). Produced within the broader current of French Neoclassicism, the work participates in a larger art-historical trend of reactivating cultural memory, staging Joan as an archetype of national endurance. Its theatrical composition and lighting transform the interrogation into melodrama, casting her both as victim and stoic heroine. Later, Paul Gauguin took her image further from verisimilitude: his Symbolist vision emptied her of concrete likeness, treating her instead as a vessel for mystical color and mood (Fig 13). In Jeanne d’Arc, or Breton Girl Spinning (1889), a traditionally dressed young woman stands against a flattened coastal and pastoral backdrop, her daily act of spinning framed by bold outlines and luminous tones. In a lesser-known work, Danhauser’s The Painter’s Studio, Joan appears as a painting within a painting, functioning less as a medieval heroine than as a cultural-art historical sign (Fig 14). With flag and armor, she fixes a commanding gaze upon a slumped male figure beside her, a pose that deliberately echoes the placement of two other couples in the same room—one in painting, and one in the foreground. In such works, Joan became a cipher through which artists appropriated her image to showcase formal and subjective concerns rather than biographical fidelity.

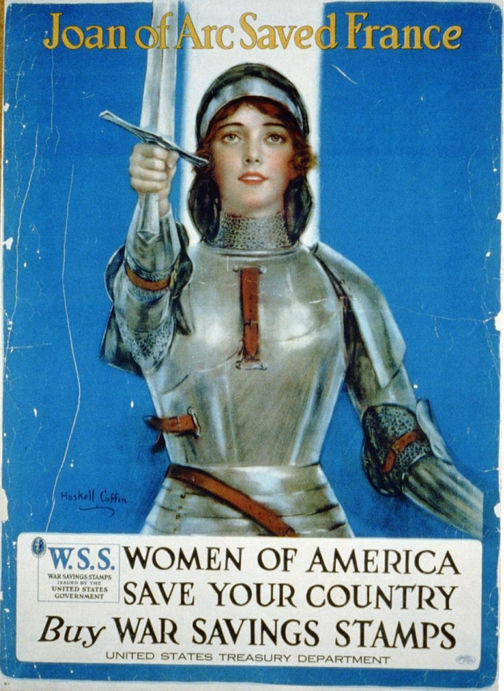

Simultaneously, secular propaganda seized upon Joan for civic ends. In the early twentieth century, suffrage groups paraded Joan as a banner of female courage, while wartime campaigns mobilized her image to embody patriotic duty. A striking example is Hilda Dallas’s Suffragette Weekly cover, which presents a shapely Joan with cinched waist and crimson lips holding high the banner of the Women’s Social and Political Union (Fig 15). Joan appears both as warrior and “New Woman,” embodying feminine beauty, modesty, and self-reliance while symbolizing women’s struggle against patriarchy. Across the Channel, her image proved equally potent for wartime propaganda28. In Britain, Bert Thomas designed a poster urging women to “Save Your Country, Buy War Saving Stamps,” directly echoing Joan’s salvation of France (Fig 16). The slogan soon crossed the Atlantic, where William Haskell Coffin depicted Joan in gleaming armor, haloed in light, brandishing a sword to rally female audiences to the war effort. In these campaigns, Joan functioned less as medieval heroine than as modern civic emblem, her sanctity repurposed into the idiom of suffrage and patriotic mobilization29.

Contemporary Ambiguities

In contemporary art, Joan of Arc reappears as a site of ambiguity itself. Artists started to probe her very instability, using her as a vehicle to test the limits of representation, cultural memory, and identity. What results is not a coherent icon but a series of works that actively stage uncertainty, through diverse media of painting, sculpture, and video.

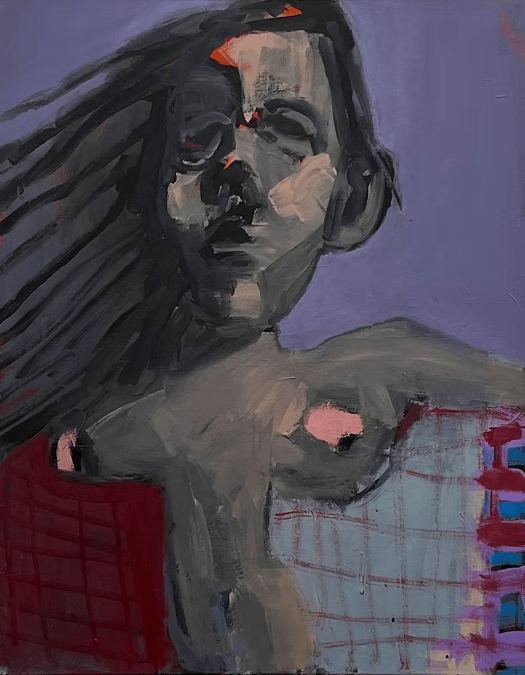

Claudia Meitert’s Joan of Arc pushes the logic of ambiguity into the register of paint itself (Fig 17). Her canvas, gestural and semi-abstract, clearly deals with the Joan icon as its title sets out, yet its image is hardly a realistic representation: a female torso, monumental in scale, rendered in raw strokes of grey, mauve, and crimson. The figure tilts upward against a stark ground with half-formed face features. Neither armor nor halo was used to situate her in history, while Joan emerges as an amalgam of obscurity. The rough brushwork builds an image yet simultaneously disintegrates and erases it. The artist has explained: “I place myself in the long tradition of artists who have portrayed Saint Joan. Girl, warrior, national saint—my work unites all these aspects and bridges the gap between the historical and the role model still valid today33.” In Meitert’s example, Joan’s image has transformed to the image of a psychological intensity, which seems to hold multiple truths together without resolving them.

Whereas Meitert destabilizes Joan through the classic medium of painting, Liane Lang does so through three-dimensional matter. With the aim of exploring “the tension between the narrative and historical dimension of the image and the texture,” the artist prints photographic imagery onto three-dimensional objects. Her work Fragment of Joan of Arc (2019) confronts the viewer with a broken bust: a partial face and hand, scarred and truncated, overlaid with photographic textures (Fig 18). The effect is uncanny, as if a monument had been half-exhumed, half-digitized. The bust recalls the solidity of stone memorials, while the photographic overlay invites the viewer to contemplate on how meaning and memory is constructed—through reproduction. In this unconventional sculpture of Joan, the figure is not presented as a traditional triumphant statue but as an incomplete relic. Fragmentation becomes the image’s subject, reminding the audience that cultural memory preserves a historic figure not in its entirety but in residual traces.

Ana Torfs’s Du mentir-faux (“About Lying Falsehood”) demonstrates how ambiguity can be generated with language and the unspeakable (Fig 19). The work consists of a slide projection of black-and-white portraits of a young woman whose face conveys suffering, interspersed with fragments of text drawn from Joan of Arc’s fifteenth-century inquisition trial. The minimalist setting and repetitive poses frustrate the viewer’s natural impulse to identify with the subject, thus reinforcing the actor’s role presented as a sign rather than as an attempt to animate a historic individual. The title, alluding to the tautological phrasing of medieval texts, underscores this irresolution. It points to the impossibility of recovering historical truth from trial documents and to the broader tension between fiction and reality, testimony and invention36.

Discussion

The analysis of Joan of Arc’s visual afterlives reveals a consistent pattern: that is, her image was rarely rendered as she appeared in life. Instead, it was adapted to familiar visual codes, often by suppressing the qualities that unsettled her contemporaries. The earliest works suggest that her memory could only survive if stripped of its most disruptive features, a pattern that shaped her iconography for centuries.

One of the most fraught issues was Joan’s dress. As Barstow observes, her “gender-blurring” was particularly threatening to ecclesiastical authority, not only because cross-dressing contravened biblical injunctions but because it destabilized the categories by which social order was policed37. To Joan herself it was “a small thing, among the smallest things”,a practical safeguard against assault and a necessity in combat, but to her judges it was a scandal of scripture and nature (V. Sackville-west, Saint Joan Of Arc). As Karyn Z. Sproles has argued, cross-dressing functioned as “an entry into the male world of power,” collapsing the distinction between saintly visionary and political actor38.

Mirroring this ambivalence, works by Sergent, Ingres, and Millais softened martial imagery with ribbons, flowing hair, and devotional postures. Sackville-West described this as a “double image”, where Joan could be imagined as passive saint or heroic captain, but rarely both at once (V. Sackville-west, Saint Joan Of Arc). Such strategies reinscribed her within the codes of beauty and piety, containing the unsettling figure of a woman in command. Even explicitly political imagery, from suffrage campaigns to wartime propaganda, reshaped her through feminized conventions such as slender waists and cosmetic features, ensuring her symbolic utility remained bound to ideals of beauty as much as to strength28.

A second contested site was her visionary experience. Bastien-Lepage, Thirion, and Bussière depicted Joan “hearing voices,” but in ways that shaded into hysteria or possession. The perennial question “Was she insane or inspired?” persisted into the nineteenth century, revealing more about cultural assumptions than about Joan herself38. Feminist theory situates such depictions within the archetype of the witch. As Sempruch notes, “the ‘witch’ as a phallogocentric archetypal construct remains intact across time and geographical space,” a figure constituted as hysterical and disordered yet persistently compelling. Joan’s ecstatic expressions, painted at the threshold of sanctity and sorcery, align with this fantasy of disorder, making her a liminal figure whose inspiration was always in danger of being read as delusion. The witch embodies a “boundless fantasy of gender … a fantasy of un/belonging,” capturing the instability Joan’s visions carried in visual culture38.

The appropriation of Joan’s image by neo-classicist and symbolist artists of the post-war era demonstrates that she had ceased to function as a historical subject to be represented. Instead, through repetition and reuse, she evolved into an entrenched sign within Europe’s cultural memory. Contemporary artists push this further, emphasizing not recovery but the instability and ambiguity of her sign itself. For them, Joan’s image becomes a medium through which to confront the dilemmas of a post–World War II world. Ana Torfs re-stages trial transcripts as a stark theatrical apparatus, reminding viewers that what remains are mediated fragments circling an absent subject35. Claudia Meitert’s abstract rendering of Joan underscores the futility of portraiture, while Liane Lang’s installations deliberately deny wholeness. These works do not attempt to restore a “true” Joan but foreground the impossibility of stabilizing her identity. In doing so, they extend the tradition of appropriating her image, this time with a self-conscious awareness that what is being appropriated is already fractured.

Conclusion

Joan of Arc’s image has moved a long way from a medieval sketch to contemporary installations, and the journey shows that her portrayals were never neutral. Each age imagined her differently: as a royal heroine dressed like a lady of the court, a nationalist virgin-warrior mixing faith and patriotism, a visionary caught between saint and witch, or, in our own time, a broken and ambiguous symbol. Every generation remade her in its own way. Looking at these changes, we can see that Joan does not give us a single, fixed portrait. Instead, she becomes a surface where people place their hopes and fears about gender, faith, and power. Her many faces show how art works through conflicts it cannot fully solve.

In the end, Joan’s lasting presence comes from this very instability. She endures because she remains unsettled, a figure who reflects the contradictions of every time that returns to her story. Joan persists as a generative site through which cultures negotiate truth, identity, and belief. This instability is understood not as a stylistic fluctuation but as a discursive condition: the image performs identity rather than reflecting it, producing meaning through repetition and recontextualization. Her continual transformation also reveals how visual culture disciplines and releases the female body as a site of power. In this sense, Joan’s image operates within a network of situated meanings rather than universal symbols, her figure becomes a process through which cultural systems articulate and contest what the “feminine” can signify. The gendered instability of her image—oscillating between devotion and defiance—thus becomes the very mechanism through which she endures. This reading also illuminates broader dynamics of representation and memory in contemporary European culture, where historical figures are continually reimagined as sites of unresolved tension between reverence and critique. Joan’s endurance therefore reveals less about a single heroine than about the visual culture that keeps returning to her, a culture that negotiates its own past through repetition, transformation, and the persistent ambiguity of its symbols.

References

- W. Shakespeare, King Henry the Sixth. [↩]

- Voltaire, The Maid of Orleans (La Pucelle d’Orléans). [↩]

- H. A. Stilke, The Life of Joan of Arc Triptych, 1843. Prisma Archivo/Alamy. [↩]

- D. G. Rossetti, Joan of Arc, 1882. The Fitzwilliam Museum. [↩]

- H. Gardner, Art Through The Ages. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.279628/page/n733/mode/2up. [↩]

- Y. Seale, How Joan of Arc Inspired Women’s Suffragists, https://publicmedievalist.com/joan-of-arc-inspired-suffragists/ (2020). [↩]

- N. M. Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700-1855): From Satire to Sanctity,

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781351154963/joan-arc-french-art-culture-1700%EF%BF%BD1855-nora-heimann. [↩] [↩] - J. G. Edge, Saint and martyr: Epochal images of Joan of Arc from the July Monarchy to the Third Republic. Caldwell College ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. 16 (2002). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- A. L. Barstow, Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 1, 29-42 (1985). [↩]

- C. Fauquembergue, Joan of Arc in the protocol of the parliament of Paris, 1429. French National Archives Nederlands. https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/cl%C3%A9ment-de-fauquembergue.html?sortBy=relevant. [↩]

- M. Franc, Le champion des dames, 1451. Manuscripts. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525033083/f8.image. [↩]

- M. Auvergne, Les Vigiles de Charles VI, 1484. Manuscripts. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105380390/f117.image. [↩]

- A. L. Barstow, Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 1, 29-42 (1985). [↩]

- Joan of Arc, portrait commissioned by the aldermen of Orléans, 1576. Oil. Musée historique et archéologique de l’Orléanais. Image via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeanne_d%27Arc,_portrait_des_%C3%A9chevins.jpg. [↩]

- L. Cranach, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, ca. 1530. Oil on Wood. Image via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lucas_Cranach_d._%C3%84._-_Judith_Victorious_-_WGA05720.jpg. [↩]

- Sergent, Blin, Portrait de Jeanne d’Arc au XVIIIe siècle, 1787. Papier vélin. Forteresse Royale de Chinon. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/portrait-de-jeanne-d-arc-au-xviiie-si%C3%A8cle-0096-und-0097/FAGv8LS1L5fyDA. [↩]

- Forteresse Royale de Chinon, Joan of Arc political figure, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/joan-of-arc-political-figure-forteresse-royale-de-chinon/lAXhj6HPBhV1Kg?hl=en. [↩]

- J. Ingres, Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII, 1854. Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065747. [↩]

- J. E. Miliais, Joan of Arc, 1865. Oil on canvas. Art Renewal Center. https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/joan-of-arc/john-everett-millais/38653. [↩]

- Sir John Everett Millais, Bart., P.R.A., H.R.I., H.R.C.A. 1829-1896, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2003/important-british-pictures-l03123/lot.25.html. [↩]

- J. Bastien-Lepage, Joan of Arc, 1879. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435621. [↩]

- J. G. Edge, Saint and martyr: Epochal images of Joan of Arc from the July Monarchy to the Third Republic. Caldwell College ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. 16 (2002). [↩]

- E. Thirion, Joan of Arc listening to the voices, 1876. Oil on canvas. Ministère de la Culture. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeanne_d%27_Arc_(Eugene_Thirion).jpg. [↩]

- G. Bussiere, Joan of Arc, 1908. Oil on canvas. Collection of Fred and Sherry Ross. https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/joan-of-arc/gaston-bussiere/3555. [↩]

- P. Delaroche, Joan of Arc Being Interrogated, 1825. Oil on canvas. Wallace Collection. https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=65234&viewType=detailView [↩]

- P. Gaugin, Breton Girl Spinning, 1889. Oil on plaster. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. http://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0513S2006 [↩]

- J. Danhauser, The Painter’s Studio, 1830. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. https://www.mfab.hu/artworks/203/ [↩]

- Billie Anania, The Misgendering of Joan of Arc, https://hyperallergic.com/746319/the-misgendering-of-joan-of-arc/ (2022). [↩] [↩]

- Forteresse Royale de Chinon, Joan of Arc political figure, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/joan-of-arc-political-figure-forteresse-royale-de-chinon/lAXhj6HPBhV1Kg?hl=en [↩]

- W.S.P.U. (Women’s Social and Political Union), (issuer), Dallas, Hilda (artist), The Suffragette 1d Weekly, 1912. Colour lithograph, ink on paper. Summary Catalogue of British Posters to 1988 in the Victoria & Albert Museum in the Department of Design, Prints & Drawing. Emmett Publishing. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O685356/the-suffragette-1d-weekly-dallas-hilda/ [↩]

- W. H. Coffin, Poster for the United States Department reads, 1918. North Carolina Digital Collections. https://hyperallergic.com/746319/the-misgendering-of-joan-of-arc/ [↩]

- C. Meitert, Jeanne (Jeanne d’ Arc), 2024. Studio Claudia Meitert.https://www.studio-claudia-meitert.com [↩]

- Toolip Gallery, Jeanne (Jeanne d’ Arc), https://www.toolipartgallery.com/product-page/jeanne-jeanne-d-arc. [↩]

- L. Lang, Joan in Fragments, 2019. Print on scagliola and panel. Courtesy of the Artist. https://www.jarilagergallery.com/artworks/1040-liane-lang-fragment-of-joan-of-arc-2019-2019/ [↩]

- A. Torfs, Du mentir-faux, 2018. Installation with black and white slide projections, projection socle, +/- 20 minutes, loop, digitally controlled, variable dimensions, text slides available in English or French. © photo: Sonia Magiapane, courtesy Grimm Amsterdam. https://www.anatorfs.com/projects/du-mentir-faux. [↩] [↩]

- Du mentir-faux. 2000, https://www.anatorfs.com/projects/du-mentir-faux. [↩]

- A. L. Barstow, Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 1, 29-42 (1985). [↩]

- J. Sempruch, Fantasies of Gender and the Witch in Feminist Theory and Literature [↩] [↩] [↩]